Summary

The interaction between pathogenic microbes and their hosts is determined by survival strategies on both sides. As a result of its redox properties, iron is vital for the growth and proliferation of nearly all organisms, including pathogenic bacteria. In bacteria–vertebrate interactions, competition for this essential metal is critical for the outcome of the infection. The role of iron in the virulence of plant pathogenic bacteria has only been explored in a few pathosystems in the past. However, in the last 5 years, intensive research has provided new insights into the mechanisms of iron homeostasis in phytopathogenic bacteria that are involved in virulence. This review, which includes important plant pathosystems, discusses the recent advances in the understanding of iron transport and homeostasis during plant pathogenesis. By summarizing the recent progress, we wish to provide an updated view clarifying the various roles played by this metal in the virulence of bacterial phytopathogens as a nutritional and regulatory element. The complex intertwining of iron metabolism and oxidative stress during infection is emphasized.

Introduction

For the vast majority of microorganisms and multicellular organisms, the transition metal iron is an essential element. Iron is involved in major metabolic processes, such as DNA synthesis, nitrogen fixation, energy‐yielding electron transfer reactions of respiration and a number of other key enzymatic reactions. The catalytic functions of this metal are related to its electronic structure, making it capable of reversible changes in oxidation state over a wide range of redox potentials. Although iron is the fourth most abundant element in the Earth's crust, its availability under aerobic conditions is limited because the oxidized form, Fe(iii), is poorly soluble at neutral pH. Thus, organisms within the same niche must compete for iron and it holds a peculiar position at the microbial pathogen–mammalian interface. To meet the iron needs necessary for their physiology and growth, microorganisms have evolved various active uptake mechanisms (Krewulak and Vogel, 2008; Sutak et al., 2008). In response to infection, mammals actively limit iron availability by sequestering it intracellularly and by chelating extracellular iron with the glycoproteins, transferrin and lactoferrin. This struggle for iron perceived by both ‘partners’ has long been described and is well established in vertebrate infections. This metal plays an important role in microbial virulence and innate immunity (for reviews, see Nairz et al., 2010; Ong et al., 2006).

Although less well documented, the role of iron in microbial pathogenesis to plants is now becoming the topic of thorough investigations. The importance of siderophores (iron carriers) in diseases caused by the enterobacterial species Dickeya dadantii (formerly Erwinia chrysanthemi) and Erwinia amylovora has been demonstrated (Expert, 1999). During the past 13 years, a wealth of information on how iron is assimilated, distributed and stored within the plant has been published, enlarging our vision on the possible physiological changes that may arise during pathological situations. With increasing knowledge of bacterial genomes, the question of iron availability and toxicity for plant bacterial pathogens has received greater attention. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the role of iron in bacterial plant infection, stressing the importance of this metal in pathogen nutrition, and as a regulatory signal in pathogenicity and a player in oxidative stress.

Iron Acquisition and Bacterial Phytopathogenicity

Plants acquire iron from the environment by the roots using mechanisms based on reduction or chelation (Jeong and Guerinot, 2009). Iron is then mobilized from the root tissues in xylem vessels by citrate, which is involved in the long‐distance transport from roots to shoots. Another molecule participating in the distribution of iron throughout the plant is the amino acid nicotianamine, which is able to chelate iron and other metals (Curie et al., 2009). Iron storage occurs at the subcellular level in chloroplasts in which the photosynthetic process takes place (Briat et al., 2010). Plastids contain ferritin, an important iron reservoir protein (Nouet et al., 2011). Vacuoles are another crucial compartment for iron storage and sequestration in plant cells. The status of iron in plant extracellular spaces is not well characterized. Thus, the availability of iron in the plant host tissues may be quite low.

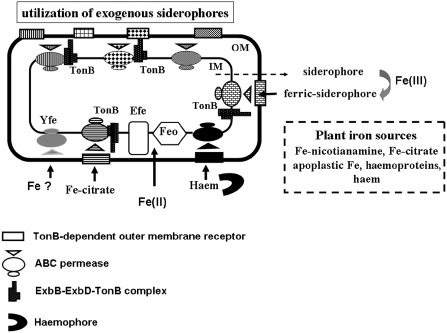

Among the diverse iron transport systems developed by bacteria, the production of siderophores that can scavenge this metal from the environment is widespread. Siderophores are low‐molecular‐weight molecules with various chemical structures that chelate ferric iron with high affinity (logarithm of dissociation constants ranging from −16 to −32). Once loaded with iron, siderophores are specifically transported through the bacterial envelope via specific protein transporters (Miethke and Marahiel, 2007) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the various iron uptake systems in phytopathogenic Gram‐negative bacteria. Bacterial cells can synthesize and excrete siderophores that form a siderophore–ferric complex with Fe(iii), designated as ‘ferric‐siderophore’. A ferric‐siderophore is specifically recognized by an outer membrane TonB‐dependent transporter (rectangles), which is a gated‐channel energized by the cytoplasmic membrane‐generated proton motive force transduced by the TonB protein and its auxiliary proteins ExbB and ExbD. Transport of a ferric‐siderophore across the inner membrane involves a less specific ABC permease (triangle and circles). Ferric complexes of citrate or of exogenous siderophores, i.e. produced by other microbes, are imported in a similar way. Haem can be transported in two ways: either directly or bound to a secreted haemophore protein which delivers it to the cytoplasm via specific TonB‐dependent transporters and specific ABC permeases. Ferrous iron can be transported through the FeoAB and/or EfeUOB systems. FeoB, the main component of the Feo system, is an integral membrane protein with an N‐terminal domain having guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activity essential for the transport function. The function of the FeoA peptide is unknown. EfeU is a potential integral inner protein acting as a permease for ferrous or ferric forms of iron. The functions of EfeO and EfeB proteins are unknown. The Yfe ABC permease can import an uncharacterized form of iron. The nature of the Fe‐nicotianamine uptake system is unknown. The diversity of these iron acquisition systems allows bacteria to obtain this metal from the plant iron sources. IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane.

The first model illustrating the importance of siderophore‐mediated iron acquisition in bacterial plant disease came from the seminal work by Expert and Toussaint (1985) on the species Dickeya dadantii 3937. Dickeya dadantii is a soft‐rotting enterobacterium that attacks a wide range of plant species, including many vegetables and ornamentals of economic importance (Czajkowski et al., 2011). These bacteria are found in soil and on plant surfaces, where they may enter via wound sites or through natural openings. During infection, D. dadantii first colonizes the intercellular space (apoplast), where it can remain latent until conditions become favourable for the development of the disease. Soft rot, the visible symptom, is mainly caused by the degradation of pectin present in the plant cell wall by pectinases secreted by bacterial cells. Under iron deficiency, the strain 3937 of D. dadantii releases two siderophores: the hydroxycarboxylate achromobactin, which is produced when iron becomes limiting (Münzinger et al., 2000), and the catecholate chrysobactin (Persmark et al., 1989), which prevails under severe iron deficiency. The production of chrysobactin and achromobactin is required for the systemic progression of maceration symptoms on the hosts: mutants defective in chrysobactin‐ or achromobactin‐mediated iron transport produce symptoms that remain localized to the inoculated leaf, indicating that these siderophores are required for the bacteria to spread throughout the plant (Dellagi et al., 2005; Enard et al., 1988; Franza et al., 2005). Furthermore, Neema et al. (1993) have shown that the production of chrysobactin enables bacterial cells to compete with plant cells for iron, preventing sequestration of this metal by the plant ferritins. Thus, this production of siderophores by D. dadantii is an efficient mechanism to acquire iron from the host and to promote infection.

The second example illustrating the role of iron assimilation in plant infection was found in fire blight, a disease of members of the Maloideae caused by Erwinia amylovora. This nonpectinolytic species uses a mechanism based on the delivery by the type III secretion system (T3SS) of specific proteins encoded by the hrp‐dsp gene cluster to invade its plant hosts. In iron‐limited environments, E. amylovora produces trihydroxamate siderophores belonging to the desferrioxamine (DFO) family. The major product of DFO biosynthesis is DFO‐E, although minor amounts of other DFOs (D2, X1–7 and G1) are also produced (Feistner et al., 1993; Kachadourian et al., 1996). Unlike mutants lacking a functional T3SS, mutants affected in DFO‐mediated iron transport still cause fire blight (Dellagi et al., 1998). The lack of DFO‐dependent iron uptake has no effect on pathogenicity when tested on apple seedling wounded leaves. However, when inoculated by spotting on apple blossom flowers, the mutants are less able to colonize floral tissues and to cause necrosis, indicating that the production of DFO is critical at the onset of infection. Annotation of the genome of E. amylovora 1430, which has been sequenced recently, shows that there is limited genetic information for iron uptake in this strain (Smits and Duffy, 2011). The absence of a complete Fec system, initially discovered in Escherichia coli and involved in the uptake of the Fe(iii)‐dicitrate complex, is particularly relevant. Thus, the DFO iron transport system of E. amylovora 1430 plays a major role in iron scavenging in planta.

Additional evidence for the role of a siderophore as an intrinsic virulence factor of a phytopathogenic bacterium came from the work performed by Taguchi et al. (2010) on Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci 6605. This Gram‐negative bacterium causes wildfire disease on host tobacco plants. Among the different pathogenicity factors of this species, Taguchi et al. (2010) demonstrated that synthesis of the siderophore pyoverdine from P. syringae pv. tabaci 6605 is indispensable for full virulence in host tobacco infection. Under low‐iron conditions, the fluorescent Pseudomonas group produces the yellow–green siderophore pyoverdine. The pyoverdine biosynthesis‐defective ΔpvdJ and ΔpvdL mutants of P. syringae pv. tabaci were less virulent than the wild‐type strain when tested by the spray inoculation method on the host plant. There was a 10% decrease in the population of both mutants on host tobacco leaves in comparison with that of the wild‐type strain. These data differ from those obtained with pyoverdine biosynthetic mutants of other P. syringae pathovars. Indeed, no change in the virulence phenotype was observed for the pyoverdine mutant of strain DC3000 on tomato and for the P. syringae pv. syringae B301D pyoverdine mutant on sweet cherry fruit (Cody and Gross, 1987; Jones and Wildermuth, 2011). This differential effect of pyoverdine on virulence may be explained by the fact that these P. syringae pathovars possess other iron transport routes mediated by siderophores unrelated to pyoverdine which can have a compensatory effect. Interestingly, the genomes of most of the P. syringae pathovars contain the fecA gene and the fecBCDE operon, which encode the TonB‐dependent receptor and the ABC permease‐mediating uptake of the Fe(iii)‐dicitrate complex (Fig. 1). Jones and Wildermuth (2011) demonstrated that P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 can use ferric citrate as an iron source in planta. These authors also showed that this pathovar can import iron‐nicotianamine with high affinity. In addition, most P. syringae pathovars possess the efeUOB operon involved in ferrous iron acquisition (Cao et al., 2007; Grosse et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). Thus, the different strains of P. syringae display a great capacity to capture iron from the tissues of the plant host and, depending on the pathovar, the implication of a given system in planta may vary.

Soluble ferrous iron, which may be available in some anaerobic–microaerophilic environments in the host, is also a potential iron source for bacteria that use the FeoAB pathway. FeoB, the main component of this system, is an integral membrane protein, the N‐terminal domain of which contains a G‐protein region having guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) activity (Marlovits et al., 2002) (Fig. 1). Although the function of FeoB has not been elucidated completely, it is assumed that this protein is an inner membrane Fe(ii) permease that requires the FeoA‐dependent hydrolysis of guanosine triphosphate (GTP) (Cartron et al., 2006). The FeoAB system is present in many bacteria and has been reported to play a significant role in infectious diseases caused by Streptococcus suis, Campylobacter jejuni and Legionella pneumophila (Aranda et al., 2009; Naikare et al., 2006; Robey and Cianciotto, 2002). A similar result was found by Pandey and Sonti (2010) in the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. This species causes bacterial blight on rice by colonizing the xylem vessels of rice leaves (Nino‐Liu et al., 2006). Analysis of the genome from this X. oryzae pathovar revealed two main loci encoding functions involved in iron acquisition: an xss gene cluster involved in the biosynthesis, export and utilization of an uncharacterized α‐hydroxycarboxylate‐type siderophore and a feoABC operon. Mutations in the xssA, xssB and xssE genes caused siderophore deficiency and growth restriction under iron‐limiting conditions, but the corresponding mutants were as virulent as the wild‐type strain when inoculated on rice leaves. However, a feoB mutant caused significantly reduced lesions on leaves compared with those produced by the wild‐type strain. By using transcriptional uidA fusions, the authors also showed that the feoB gene of X. oryzae pv. oryzae was expressed during in planta growth, whereas the xssE siderophore biosynthetic gene fusion was not. Sources of ferrous iron in planta have not been defined, but Yokosho et al. (2009) showed that the ferrous form of iron predominates in the rice xylem sap, whereas Fe(iii) is mainly present as ferric citrate. Genome analysis revealed that this pathovar does not possess a Fec system enabling it to assimilate ferric citrate, thus making relevant the importance of the Feo transport system for successful colonization of rice xylem vessels by X. oryzae pv. oryzae.

Interestingly, our group also demonstrated that the D. dadantii FeoAB system can be functional during plant infection. In a D. dadantii feoB‐negative mutant, it was shown that, in an achromobactin‐ and chrysobactin‐negative background, the feoB mutation conferred a threefold reduction in iron uptake under reducing conditions relative to the FeoB‐positive strain. The pathogenicity of an feoB mutant relative to the wild‐type strain on Arabidopsis thaliana plants was not affected. However, in a siderophore‐negative background, the feoB mutation resulted in a reduced number of systemic infections, which were twofold lower than with the siderophore nonproducer and five times lower than with the wild‐type strain (Franza and Expert, 2010). Okinaka et al. (2002) showed that the D. dadantii feoB gene was up‐regulated during the infection of African violets. Homologues of the E. coli feoB gene are present in several plant pathogenic genera (Table 1), indicating that these bacteria have the capacity to assimilate ferrous iron to cope with the various environmental conditions encountered during their pathogenic life cycle.

Table 1.

Siderophore‐independent iron acquisition systems in some phytopathogenic bacteria

| Feo system |

| Dickeya dadantii 3937; D. chrysanthemi 1591; D. zeae 586; D. paradisiaca 703 |

| Ralstonia solanacearum GMI 1000; R. solanacearum CFBP2957 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris B100; X. oryzae pv. oryzae; X. oryzae pv. oryzicola |

| Xylella fastidiosa |

| EfeUOB system |

| Dickeya dadantii 3937; D. chrysanthemi 1591; D. zeae 586; D. paradisiaca 703 |

| Erwinia amylovora 1430 |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000; P. syringae pv. syringae B728a; P. syringae pv. tabaci ATCC 11528, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola |

| FecABCDE system |

| Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI 1043; P. brasiliensis 1692; P. carotovorum PC1 |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a; P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000; P. syringae pv. tabaci ATCC 11528; P. syringae pv. phaseolicola |

| Haemophore system |

| Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI 1043; P. brasiliensis 1692; P. carotovorum PC1 and WPP14; P. wasabiae WPP163 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 |

| Hmu system |

| Dickeya dadantii 3937; D. chrysanthemi 1591; D. paradisiaca 703 |

| Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI 1043; P. carotovorum PC1 and WPP14; P. brasiliensis 1692; P. wasabiae WPP163 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 |

| Yfe system |

| Dickeya dadantii 3937, D. chrysanthemi 1591; |

| Pectobacterium atrosepticum SCRI 1043; P. carotovorum PC1 and WPP14; P. brasiliensis 1692; P. wasabiae WPP163 |

| Erwinia amylovora 1430 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 |

Iron as a Regulatory Signal in Pathogenicity

During infection, one of the most important strategies of vertebrate host defence is the withholding of iron from invading microbes. This host inducible response leads to a decrease in iron availability for the pathogens. A low level of this metal is a regulatory signal that can control the expression of several major virulence factors from pathogens that are not related to iron metabolism (Nairz et al., 2010; Weinberg, 2009).

Iron transport requires energy and is tightly regulated in bacteria: high‐affinity iron acquisition system expression is inversely correlated with iron concentration. In many Gram‐negative bacteria, genes involved in iron transport, metabolism and homeostasis are regulated by the ferric uptake regulator protein Fur (Lee and Helmann, 2007). Fur is a homodimer composed of 17‐kDa subunits that acts as a repressor of transcription using ferrous ions as co‐repressor. In the presence of Fe(ii), Fur binds to a conserved DNA sequence, the Fur box, shown to be present in the promoter region of a large number of iron‐regulated genes (Escolar et al., 1999). Thus, when iron levels exceed those needed for cellular functions, Fur represses further uptake and thereby helps prevent iron overload and toxicity. In several pathogenic bacteria, Fur is also involved in the control of virulence factors unrelated to iron transport. In Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Fur is required for virulence by indirect activation of the regulator HilA which positively controls the SPI‐1 pathogenicity island 1 (Troxell et al., 2011). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the alternative sigma factor PvdS, which positively controls the production of virulence factors (e.g. exotoxin A, pyoverdine and the PrpL extracellular protease), is regulated by Fur (Visca et al., 2002).

The Fur paradigm also occurs in D. dadantii 3937, where this metalloregulator negatively controls iron transport genes and the genes encoding the PelD and PelE pectate lyase enzymes, which are responsible for the degradation of plant cell wall pectin (Franza et al., 1999). This regulation implies two distinct mechanisms. DNaseI footprinting experiments demonstrated that the Fur binding site covers the −35 and −10 promoter elements of the ferric chrysobactin receptor encoding gene fct, suggesting a direct competition between the RNA polymerase and Fur. However, for the pelD and pelE gene promoters, the sequence protected by Fur is located upstream from the −35 promoter element and includes part of the binding site of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP), required for the activation of pel gene transcription. In this case, Fur would act as an anti‐activator of transcription by blocking the action of CRP (Franza et al., 2002). Furthermore, in conditions of pectinolysis, when the genes coding for pectin‐degrading enzymes are turned on, the achromobactin and chrysobactin iron transport systems are constitutively expressed. Thus, the two pathogenicity determinants, iron acquisition and the production of pectinases, are regulated in a coordinated manner, and this metabolic coupling can confer an important advantage to D. dadantii cells during pathogenesis. When inoculated on African violets, the fur mutant displayed an altered virulence in comparison with that of the wild‐type strain. This reduced pathogenicity of the fur mutant on its host was explained by its altered growth capacity in planta. Indeed, 3 days after inoculation, the population of the fur mutant showed a 10‐fold decrease in leaves, whereas there was a 10‐fold increase in the population of the wild‐type strain (Franza et al., 1999).

Later, the role of the Fur protein was investigated in the species X. oryzae pv. oryzae (Subramoni and Sonti, 2005). These authors showed that siderophores were produced in a constitutive manner in an X. oryzae fur mutant. The fur mutant displayed an increased sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and streptonigrin, a compound generating oxygen radicals. When inoculated on rice leaves, the X. oryzae fur mutant caused lesions with a reduced size in comparison with those of the wild‐type strain. Indeed, this mutant exhibited a reduced growth capacity in planta. Interestingly, exogenous supplementation with ascorbic acid, an antioxidant compound, rescued the growth deficiency of the fur mutant in rice leaves (Subramoni and Sonti, 2005). Therefore, the authors concluded that the reduced virulence of the X. oryzae pv. oryzae fur mutant may be a result of an impaired ability to cope with the oxidative stress conditions that are encountered during infection. These findings were recently extended to Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, the causal agent of black rot of crucifers. The fur mutant of X. campestris pv. campestris showed the constitutive production of siderophores and reduced resistance to oxidative stress (Jittawuttipoka et al., 2010). Pathogenicity tests on Chinese cabbage leaves revealed that the fur mutant was unable to produce the wild‐type lesion level.

This major role of Fur was also reported by the work of Cha et al. (2008) performed on the species P. syringae pv. tabaci 11528, which causes wild‐fire disease in tobacco plants. The growth capacity and virulence of the P. syringae pv. tabaci 11528 fur mutant were attenuated on tobacco leaves. The fur mutant also exhibited a decrease in swarming motility, as well as in the synthesis of tabtoxin and N‐acylhomoserine lactones. Thus, in this species, Fur acts as a global regulator controlling the expression of several pathogenicity factors. This important coordinating and regulatory function was found to occur in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, in which a large Fur regulon was identified (Butcher et al., 2011). In this pathovar, Fur also controls the gene pvdS encoding the extracytoplasmic sigma factor PvdS. Swingle et al. (2008) demonstrated that this alternative sigma factor activates the expression of several genes, including those involved in the synthesis and transport of the pyoverdine siderophore. Unfortunately, Butcher and collaborators did not construct a fur null mutant.

The physiological function of the Fur regulator was also studied in the Alphaproteobacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4. Kitphati et al. (2007) demonstrated that, in this strain, the Fur repressor plays an important role in manganese homeostasis and resistance to H2O2. The virulence assays also showed that the fur mutant has a reduced ability to cause tumours on tobacco leaf pieces compared with the wild‐type strain NTL4. However, the Fur protein was not found to be the dominant regulator of iron transport and siderophore synthesis in A. tumefaciens NTL4 (Kitphati et al., 2007). Indeed, in some branches of the Alphaproteobacteria, the regulation of iron‐responsive genes is quite complex and involves several regulators: Fur functions predominantly to regulate the cellular response to manganese levels, whereas the RirA (rhizobial iron regulator) protein carries out typical Fur functions in the regulation of iron‐responsive genes for the maintenance of iron homeostasis (Johnston et al., 2007). The RirA protein belongs to the Rrf2 family of transcriptional regulators. RirA is an Fe–S protein that acts as a repressor of many iron‐responsive genes under iron‐replete conditions. The A. tumefaciens RirA regulatory network was examined by Ngok‐Ngam et al. (2009). These authors found that this regulator is a repressor of genes involved in iron uptake, and that the corresponding rirA mutant exhibited increased sensitivity to H2O2 and to the superoxide anion in comparison with the wild‐type strain. On tobacco leaves, the rirA mutant caused tumours that were fewer and smaller than those formed by the wild‐type strain. Furthermore, in this mutant, a reduction in the induction of the virB and virE genes involved in tumorigenesis was observed, indicating that this regulator is required for full expression of virulence genes (Ngok‐Ngam et al., 2009). Thus, in A. tumefaciens, the control of iron homeostasis by RirA is essential for virulence and stress survival. This finding is interesting because Hibbing and Fuqua (2011) showed that there is a second iron‐responsive regulator, called Irr, in A. tumefaciens. Irr represents a distinct branch of the Fur family of transcriptional regulators that was first discovered in the soybean‐nodulating organism Bradyrhizobium japonicum as a regulator of haem biosynthesis (O'Brian and Fabiano, 2010). In A. tumefaciens, Irr and RirA function in concert to balance iron homeostasis via the control of iron uptake and utilization (Hibbing and Fuqua, 2011). However, the role of Irr in the oxidative stress response and in virulence was not examined in this study.

Effects of Iron Status on the Oxidative Burst

During the infectious process, phytopathogenic bacteria encounter an oxidative environment: reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated by host plants as a defence mechanism against microbial invasion. This plant defence response consists of the production of superoxide, H2O2 and nitric oxide, which function either directly in the establishment of defence mechanisms or indirectly via synergistic interactions with other signalling molecules, such as salicylic acid (reviewed in Bolwell and Daudi, 2009). Under these conditions, a tight control of the iron concentration is essential for the invading bacteria, because an excess of this metal can exacerbate the oxidative stress through the Fenton reaction, which generates the highly toxic and reactive hydroxyl radical OH● (Luo et al., 1994).

Siderophores can interfere with this reaction by sequestering Fe(iii), and thus influencing the Fe(iii)/Fe(ii) ratio. The role of siderophores in the oxidative burst was illustrated by the work of Dellagi et al. (1998) on E. amylovora. Mutants altered in the biosynthesis of the siderophore DFO were less able than the wild‐type strain to colonize floral tissues and to initiate necrosis on apple flowers. Furthermore, the ability of DFO biosynthetic mutants to induce electrolyte leakage from host plant cells was severely reduced in comparison with the wild‐type strain. This defect was rescued by the addition of exogenous DFO. As DFO alone does not induce electrolyte leakage, it was proposed that this compound, by inhibiting the generation of toxic radicals via Fenton‐type redox chemistry, protects the bacterial cells against the toxic effects of ROS produced at the onset of infection. Indeed, the survival of cells of E. amylovora treated with 1 mm of H2O2 was strongly enhanced by the addition of DFO B (Dellagi et al., 1998).

In D. dadantii, several studies have demonstrated the importance of the perfect control of iron homeostasis, implying a connection between iron metabolism and tolerance to oxidative stress. For example, a fur mutant, which accumulates this metal intracellularly, is more sensitive than the wild‐type strain to H2O2 and to compounds generating superoxide anion, NO and hydroxyl radical OH●. Indeed, in Luria–Bertani medium, in the presence of 0.5 mm H2O2, 6 μm paraquat or 70 μm spermine NONOate, the growth capacity of the fur mutant was decreased by 40% in comparison with that of the wild‐type strain (T. Franza, unpublished data). When treated with 4 μm of streptonigrin, D. dadantii fur bacterial cells lysed (T. Franza, unpublished data). These results indicate that, in the fur mutant, there is an increase in reactive iron, exacerbating the oxidative stress. The connection between iron metabolism and tolerance to oxidative conditions was emphasized by the discovery that the Suf (mobilization of sulphur) machinery, encoded by the sufABCDSE operon, participates in the formation of Fe–S clusters under iron starvation and oxidative conditions, and is necessary for full virulence (Nachin et al., 2001). Indeed, under oxidative stress conditions, Fe–S clusters can be damaged, thus leading to an increase in the reactive iron pool. Furthermore, during infection, a safe and accurate control of the bacterial intracellular iron storage and utilization is performed by the iron storage proteins ferritin and bacterioferritin, FtnA and Bfr, respectively (Boughammoura et al., 2008). These proteins belong to the maxiferritin family and are composed of 24 identical subunits, making a spherical protein shell surrounding a central cavity able to hold up to 2000–3000 ferric iron atoms. Owing to their ferroxidase activity, ferritins oxidize excess ferrous ions and store the ferric form in a nonreactive bioavailable mineral core (for a review, see Le Brun et al., 2010). The D. dadantii FtnA ferritin is involved in resistance to redox stress conditions and in the long‐term storage of iron that can be used later during conditions of iron starvation. The Bfr bacterioferritin participates in the optimized intracellular distribution and utilization of iron that can be beneficial to D. dadantii cells for growth in fluctuating environments (Expert et al., 2008). Pathogenicity tests have shown that FtnA and Bfr contribute differentially to the virulence of D. dadantii depending on the host: both the ftnA and bfr mutants are less aggressive on chicory leaves, whereas only the ftnA mutant displays a reduced virulence on African violets. Zhao et al. (2005) found that the E. amylovora gene encoding the ferritin Ftn is induced during infection in pear tissue. However, the importance of the maxiferritin proteins in the survival and pathogenesis of other phytopathogenic bacteria remains to be evaluated, because these proteins have been found to play such roles in species infecting mammalian hosts.

The ferritin family also includes the Dps proteins, which are also called miniferritin because they comprise just 12 subunits that form a smaller molecule. Historically, Dps proteins (DNA‐binding proteins from starved cells) were found to protect DNA from oxidative damage by interacting with DNA without apparent sequence specificity. However, Dps proteins possess a ferritin‐like function that endows them with iron and H2O2 detoxification properties mediated by their ferroxidase centre (for a review, see Chiancone and Ceci, 2010). Dps proteins can also help to overcome environmentally challenging conditions, including starvation, pH shock, osmotic and thermal stress. Experiments analysing the intracellular iron distribution in D. dadantii demonstrated that the Dps protein and the Bfr bacterioferritin participate in iron utilization and distribution (Expert et al., 2008). Recently, the physiological function of the D. dadantii Dps protein was investigated further. A Dps‐deficient mutant grew like the wild‐type strain under iron starvation and showed no decreased iron content. However, the dps mutant displayed an increased sensitivity to H2O2 in comparison with the wild‐type strain during the stationary growth phase. This mutant was not more susceptible to compounds generating superoxide, OH● and NO than the wild‐type strain. Unlike the bfr and ftnA mutants, the dps mutant was not affected in its pathogenicity on host plants (Boughammoura et al., 2012). Thus, the D. dadantii Dps miniferritin plays a minor role in iron homeostasis, but is important in conferring tolerance to H2O2 and for survival of cells that enter the stationary phase of growth.

These findings are different from those obtained with the soil‐borne plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum UW551 belonging to the group R3bv2 (race 3, biovar 2). This strain causes brown rot of potato and bacterial wilt of tomato in tropical highlands and some temperate zones (van Elsas et al., 2000). An in vivo expression technology (IVET)‐like screen identified several genes from R. solanacearum up‐regulated by tomato root exudates (Colburn‐Clifford et al., 2010). This screen identified a gene that encodes a Dps protein. The R. solanacearum dps mutant displayed a lower tolerance to H2O2. Interestingly, the dps mutant caused slightly delayed bacterial wilt disease in tomato after a naturalistic soil soak inoculation. However, this mutant showed a more pronounced reduction in virulence when bacteria were inoculated directly through cut petioles, suggesting that Dps helps R. solanacearum to adapt to stressful conditions inside the plant. Furthermore, it was found that a functional dps gene may also contribute to tomato root adherence. This work indicates that R. solanacearum must overcome an oxidative stress during the bacterial wilt disease cycle and that Dps is involved in this stress survival and contributes to host plant colonization. This example illustrates the implication of Dps in pathogenicity, and it remains to be determined whether it occurs in other phytopathogenic bacteria, as is the case in mammalian pathosystems.

Final Remarks

This review presents a summary of our current knowledge of the role of iron in pathogenic bacterium–plant interactions. A more precise picture is now emerging on this topic, but crucial questions remain to be investigated.

An important obstacle in the comprehension of iron competition between bacteria and plants is the lack of information on the siderophores produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Indeed, very few siderophores of plant pathogenic species have been chemically and structurally characterized (Table 2). Depending on their iron‐chelating functional groups, siderophore molecules possess different affinity for Fe(iii) and exhibit different chelating capacity and stability under pH variations. These parameters must be evaluated in order to determine the functional role played by a given siderophore during the infectious cycle (i.e. growth and survival of microbes in the soil and in the plant host tissues). Genome sequence analysis revealed that several phytopathogenic bacteria encode more than one siderophore iron uptake system that can be distinct in very close strains or pathovars. An illustration of this complexity is given by the strain EC16 of D. dadantii which produces dichrysobactin and linear/cyclic trichrysobactin in addition to the monomeric siderophore chrysobactin (Sandy and Butler, 2011). The synthesis of different siderophores may help bacteria to cope with the fluctuations of iron availability encountered within plant tissues. Indeed, different siderophore‐dependent iron transport routes can be differentially expressed and play distinct roles according to environmental conditions or pathological situations. These aspects are important to consider in order to characterize their respective potential roles in pathogenicity.

Table 2.

Siderophores produced by phytopathogenic bacteria with their role in virulence

| Species/strain | Typical disease | Characterized siderophore(s) | Role in pathogenicity (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae strain B301D | Fruit necrotic spots | Pyoverdine | Not required for cherry fruit disease (Cody and Gross, 1987) |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 | Bacterial speck of tomato | Yersiniabactin, pyoverdine | Not required for tomato and Arabidopsis diseases (Jones et al., 2007; Jones and Wildermuth, 2011) |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci strain 6605 | Wildfire disease on host tobacco plants | Pyoverdine | Necessary for tobacco leaf infection (Taguchi et al., 2010) |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola strain 1448a | Bean halo blight | Pyoverdine, achromobactin | Not required for bean pod infection (Owen and Ackerley, 2011) |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain B6 | Crown gall tumours on dicot plants | Agrobactin | Not required for carrot or sunflower disease (Leong and Neilands, 1981) |

| Ralstonia solanacearum strain AW1 | Bacterial wilt on many plants | Staphyloferrin B | Not required for tomato plant infection (Bhatt and Denny, 2004) |

| Dickeya dadantii strain 3937 (Erwinia chrysanthemi) | Soft rot on many plants | Chysobactin; achromobactin | Required for virulence on host plants (Enard et al., 1988; Franza et al., 2005; Neema et al., 1993) |

| Erwinia carotovora strain W3C105 | Potato stem rot | Chrysobactin; aerobactin | No role in aerial stem rot (Ishimaru and Loper, 1992) |

| Erwinia amylovora strain 1430 | Fire blight on Pomoideae | Desferrioxamines | Required for virulence on apple flowers (Dellagi et al., 1998) |

Other functions involved in iron acquisition can also be important for virulence, as is the case with the Feo system from X. oryzae pv. oryzae. Ferrous iron can thus be a source available in planta for invading bacteria. Interestingly, a Feo transport machinery is present in R. solanacearum, Xylella fastidiosa and in several Xanthomonas and Dickeya species (Table 1). Furthermore, several plant pathogenic bacterial species (Table 1) possess an EfeUOB system, which is known to transport ferrous iron in E. coli (Cao et al., 2007; Grosse et al., 2006) (Fig. 1). Thus, it seems that most plant pathogenic bacteria have the ability to assimilate ferrous iron: it remains to be assessed whether this capacity could confer a growth advantage on these bacteria at some stage of the disease process. The utilization of haem and/or the ferric complexes of citrate and nicotianamine as iron sources in planta must also be considered to establish the role of iron capture in phytopathogenicity (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Indeed, bacteria from the genera Dickeya, Pectobacterium and Agrobacterium possess the Hmu system which transports haem. This system comprises a TonB‐dependent outer membrane receptor HmuR, which takes up free or haemoprotein‐bound haem from the medium, and a periplasmic binding protein‐dependent ABC permease (HmuT, U and V) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the induction of D. dadantii hmu genes was observed in planta during infection by Okinaka et al. (2002) and Yang et al. (2004). Some of these species also have an additional haem import route (Table 1 and Fig. 1). This is based on the extracellular production of proteins, called haemophores, which, because of their high affinity for haem, can extract this compound from various haemoproteins and convey it to specific TonB‐dependent outer membrane receptors that internalize only haem (Cescau et al., 2007). Citrate‐mediated ferric iron acquisition seems to be restricted to the genera Pectobacterium and Pseudomonas (Table 1). Other iron assimilation tools, such as the Yfe ABC permease system, which transports iron and manganese in Yersinia pestis, could also be implicated: the YfeABCD permease is indeed present in the genera Dickeya and Pectobacterium, as well as in E. amylovora and A. tumefaciens (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The finding by Okinaka et al. (2002,2004) and Yang et al. (2004) that the D. dadantii yfeA gene is up‐regulated during the infection of African violets and of spinach leaves may be relevant, as this permease machinery is known to play a role in the virulence of enterobacteria, such as Yersinia pestis and Photorhabdus luminescens. Depending on the inoculation methods and the nature of the infected plant tissues, multiple and distinct iron acquisition pathways can be used by invading bacterial cells.

In conclusion, there are now several lines of evidence that phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi can use siderophores and other iron uptake systems to multiply in the host and to promote infection (Eichhorn et al., 2006; Hof et al., 2007; Oide et al., 2006). These findings indicate that a competition for iron between the host and the microorganism can take place (Dellagi et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2007). Indeed, during infection by D. dadantii, A. thaliana plants develop an iron‐withholding response that changes iron distribution and trafficking (Segond et al., 2009). This is caused by the D. dadantii siderophores which can interfere with plant defence responses and exacerbate iron mobilization from the roots (Dellagi et al., 2009). These findings are in agreement with the fact that the plant iron status can also influence the development of the disease. In A. thaliana, iron deficiency affects plant defence responses and confers resistance to D. dadantii and to the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea (Kieu et al., 2012). These recent advances highlight the critical role of iron in plant host–parasite relationships. The knowledge of the mechanisms involved in the exchange and withholding of iron during plant–microbe interaction is necessary to develop integrative strategies for the control of plant diseases, such as microbial antagonism based on competition for iron. This aspect of microbial–plant pathogenesis could also be considered by researchers engineering iron‐biofortified plants in order to increase the dietary intake of this metal.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editors for considering our review. Thanks are due to the reviewers for their insightful comments which improved the quality of the manuscript. We would like to thank our numerous past and present colleagues from France, Europe, USA and Japan for their many stimulating and fruitful discussions which made this ‘research adventure’ possible and exciting. We apologize to all colleagues whose studies could not be referred to owing to space constraints. Research in our laboratory was supported by grants from the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) and the Université Pierre et Marie Curie (UPMC). DE is a researcher from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).

References

- Aranda, J. , Cortés, P. , Garrido, M.E. , Fittipaldi, N. , Llagostera, M. , Gottschalk, M. and Barbé, J. (2009) Contribution of the FeoB transporter to Streptococcus suis virulence. Int. Microbiol. 12, 137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, G. and Denny, T.P. (2004) Ralstonia solanacearum iron scavenging by the siderophore staphyloferrin B is controlled by PhcA, the global virulence regulator. J. Bacteriol. 186, 7896–7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell, G.P. and Daudi, A. (2009) Reactive oxygen species in plant pathogen interactions In: Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling, Signaling and Communication in Plants (del Rio L.A. and Puppo A., eds), pp. 113–133. Berlin: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Boughammoura, A. , Matzanke, B.F. , Böttger, L. , Reverchon, S. , Lesuisse, E. , Expert, D. and Franza, T. (2008) Differential role of ferritins in iron metabolism and virulence of the plant pathogenic bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1518–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughammoura, A. , Expert, D. and Franza, T. (2012) Role of the Dickeya dadantii Dps protein. Biometals, 25, 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briat, J.F. , Duc, C. , Ravet, K. and Gaymard, F. (2010) Ferritins and iron storage in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1800, 806–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, B.G. , Bronstein, P.A. , Myers, C.R. , Stodghill, P.V. , Bolton, J.J. , Markel, E.J. , Filiatrault, M.J. , Swingle, B. , Gaballa, A. , Helmann, J.D. , Schneider, D.J. and Cartinhour, S.W. (2011) Characterization of the Fur regulon in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4598–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J. , Woodhall, M.R. , Alvarez, J. , Cartron, M.L. and Andrews, S.C. (2007) EfeUOB (YcdNOB) is a tripartite, acid‐induced and CpxAR‐regulated, low‐pH Fe2+ transporter that is cryptic in Escherichia coli K‐12 but functional in E. coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 857–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartron, M.L. , Maddocks, S. , Gillingham, P. , Craven, C.J. and Andrews, S.C. (2006) Feo transport of ferrous iron into bacteria. Biometals, 19, 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cescau, S. , Cwerman, H. , Létoffé, S. , Delepelaire, P. , Wandersman, C. and Biville, F. (2007) Heme acquisition by hemophores. Biometals, 20, 603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.Y. , Lee, J.S. , Oh, J.I. , Choi, J.W. and Baik, H.S. (2008) Functional analysis of the role of Fur in the virulence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci 11528: fur controls expression of genes involved in quorum‐sensing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366, 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiancone, E. and Ceci, P. (2010) The multifaceted capacity of Dps proteins to combat bacterial stress conditions: detoxification of iron and hydrogen peroxide and DNA binding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1800, 798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody, Y.S. and Gross, D.C. (1987) Outer membrane protein mediating iron uptake via pyoverdinpss, the fluorescent siderophore produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae . J. Bacteriol. 169, 2207–2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn‐Clifford, J.M. , Scherf, J.M. and Allen, C. (2010) Ralstonia solanacearum Dps contributes to oxidative stress tolerance and to colonization of and virulence on tomato plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 7392–7399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie, C. , Cassin, G. , Couch, D. , Divol, F. , Higuchi, K. , Le Jean, M. , Misson, J. , Schikora, A. , Czernic, P. and Mari, S. (2009) Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1‐like transporters. Ann. Bot. 103, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski, R. , van Pérombelon, M.C.M., van der Veen, J.A. and Wolf, J.M. (2011) Control of blackleg and tuber soft rot of potato caused by Pectobacterium and Dickeya species: a review. Plant. Pathol. 60, 999–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Dellagi, A. , Brisset, M.N. , Paulin, J.P. and Expert, D. (1998) Dual role of desferrioxamine in Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 11, 734–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellagi, A. , Rigault, M. , Segond, D. , Roux, C. , Kraepiel, Y. , Cellier, F. , Briat, J.F. , Gaymard, F. and Expert, D. (2005) Siderophore‐mediated upregulation of Arabidopsis ferritin expression in response to Erwinia chrysanthemi infection. Plant J. 43, 262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellagi, A. , Segond, D. , Rigault, M. , Fagard, M. , Simon, C. , Saindrenan, P. and Expert, D. (2009) Microbial siderophores exert a subtle role in Arabidopsis during infection by manipulating the immune response and the iron status. Plant Physiol. 150, 1687–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, H. , Lessing, F. , Winterberg, B. , Schirawski, J. , Kämper, J. , Müller, P. and Kahmann, R. (2006) A ferroxidation/permeation iron uptake system is required for virulence in Ustilago maydis . Plant Cell, 18, 3332–3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Elsas, J.D. , van Kastelein, P., van der Bekkum, P., de Wolf, J.M., van Vries, P.M. and Overbeek, L.S. (2000) Survival of Ralstonia solanacearum biovar 2, the causative agent of potato brown rot, in field and microcosm soils in temperate climates. Phytopathology, 90, 1358–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enard, C. , Diolez, A. and Expert, D. (1988) Systemic virulence of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 requires a functional iron assimilation system. J. Bacteriol. 170, 2419–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escolar, L. , de Perez‐Martin, J. and Lorenzo, V. (1999) Opening the iron box: transcriptional metalloregulation by the Fur protein. J. Bacteriol. 181, 6223–6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert, D. (1999) Withholding and exchanging iron: interactions between Erwinia ssp. and their plant hosts. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37, 307–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert, D. and Toussaint, A. (1985) Bacteriocin‐resistant mutants of Erwinia chrysanthemi: possible involvement of iron acquisition in phytopathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 163, 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expert, D. , Boughammoura, A. and Franza, T. (2008) Siderophore controlled iron assimilation in the enterobacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi: evidence for the involvement of bacterioferritin and the Suf iron–sulfur cluster assembly machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 36 564–36 572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feistner, G.J. , Stahl, D.C. and Gabrik, A.H. (1993) Proferrioxamine siderophores of Erwinia amylovora. A capillary liquid chromatographic/electrospray tandem mass spectrometry study. Org. Mass. Spectrom. 2, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Franza, T. and Expert, D. (2010) Iron uptake in soft rot Erwinia In: Iron Uptake and Homeostasis in Microorganisms (Cornelis P. and Andrews S.C., eds), pp. 101–115. Wymondham, Norfolk: Caister Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franza, T. , Sauvage, C. and Expert, D. (1999) Iron regulation and pathogenicity in Erwinia chrysanthemi strain 3937: role of the Fur repressor protein. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 12, 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franza, T. , Michaud‐Soret, I. , Piquerel, P. and Expert, D. (2002) Coupling of iron assimilation and pectinolysis in Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 15, 1181–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franza, T. , Mahe, B. and Expert, D. (2005) Erwinia chrysanthemi requires a second iron transport route dependent on the siderophore achromobactin for extracellular growth and plant infection. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, C. , Scherer, J. , Koch, D. , Otto, M. , Taudte, N. and Grass, G. (2006) A new ferrous iron‐uptake transporter, EfeU (YcdN), from Escherichia coli . Mol. Microbiol. 62, 120–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing, M.E. and Fuqua, C. (2011) Antiparallel and interlinked control of cellular iron levels by the Irr and RirA regulators of Agrobacterium tumefaciens . J. Bacteriol. 193, 3461–3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof, C. , Eisfeld, K. , Welzel, K. , Antelo, L. , Foster, A.J. and Anke, H. (2007) Ferricrocin synthesis in Magnaporthe grisea and its role in pathogenicity in rice. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, C.A. and Loper, J.E. (1992) High‐affinity iron uptake systems present in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora include the hydroxamate siderophore aerobactin. J. Bacteriol. 174, 2993–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. and Guerinot, M.L. (2009) Homing in on iron homeostasis in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jittawuttipoka, T. , Sallabhan, R. , Vattanaviboon, P. , Fuangthong, M. and Mongkolsuk, S. (2010) Mutations of ferric uptake regulator (fur) impair iron homeostasis, growth, oxidative stress survival, and virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris . Arch. Microbiol. 192, 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, A.W. , Todd, J.D. , Curson, A.R. , Lei, S. , Nikolaidou‐Katsaridou, N. , Gelfand, M.S. and Rodionov, D.A. (2007) Living without Fur: the subtlety and complexity of iron‐responsive gene regulation in the symbiotic bacterium Rhizobium and other alpha‐proteobacteria. Biometals, 20, 501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.M. and Wildermuth, M.C. (2011) The phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 has three high‐affinity iron‐scavenging systems functional under iron limitation conditions but dispensable for pathogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2767–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.M. , Lindow, S.E. and Wildermuth, M.C. (2007) Salicylic acid, yersiniabactin, and pyoverdin production by the model phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000: synthesis, regulation, and impact on tomato and Arabidopsis host plants. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6773–6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachadourian, R. , Dellagi, A. , Laurent, J. , Bricard, L. , Kunesch, G. and Expert, D. (1996) Desferrioxamine‐dependent iron transport in Erwinia amylovora CFBP 1430: cloning of the gene encoding the ferrioxamine receptor FoxR. Biometals, 9, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieu, N.P. , Aznar, A. , Segond, D. , Rigault, M. , Simond‐Côte, E. , Kunz, C. , Soulie, M.C. , Expert, D. and Dellagi, A. (2012) Iron deficiency affects plant defence responses and confers resistance to Dickeya dadantii and Botrytis cinerea . Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitphati, W. , Ngok‐Ngam, P. , Suwanmaneerat, S. , Sukchawalit, R. and Mongkolsuk, S. (2007) Agrobacterium tumefaciens fur has important physiological roles in iron and manganese homeostasis, the oxidative stress response, and full virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4760–4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak, K.D. and Vogel, H.J. (2008) Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1778, 1781–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Brun, N.E. , Crow, A. , Murphy, M.E. , Mauk, A.G. and Moore, G.R. (2010) Iron core mineralisation in prokaryotic ferritins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1800, 732–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W. and Helmann, J.D. (2007) Functional specialization within the Fur family of metalloregulators. Biometals, 20, 485–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong, S.A. and Neilands, J.B. (1981) Relationship of siderophore‐mediated iron assimilation to virulence in crown gall disease. J. Bacteriol. 147, 482–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G. , Greenshields, D.L. , Sammynaiken, R. , Hirji, R.N. , Selvaraj, G. and Wei, Y. (2007) Targeted alterations in iron homeostasis underlie plant defense responses. J. Cell Sci. 120, 596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. , Han, Z. , Chin, S.M. and Linn, S. (1994) Three chemically distinct types of oxidants formed by iron‐mediated Fenton reactions in the presence of DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12 438–12 442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlovits, T.C. , Haase, W. , Herrmann, C. , Aller, S.G. and Unger, V.M. (2002) The membrane protein FeoB contains an intramolecular G protein essential for Fe(II) uptake in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 16 243–16 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke, M. and Marahiel, M.A. (2007) Siderophore‐based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 413–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzinger, M. , Budzikiewicz, H. , Expert, D. , Enard, C. and Meyer, J.M. (2000) Achromobactin, a new citrate siderophore of Erwinia chrysanthemi . Z. Naturforsch. (C), 55, 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachin, L. , El Hassouni, M. , Loiseau, L. , Expert, D. and Barras, F. (2001) SoxR‐dependent response to oxidative stress and virulence of Erwinia chrysanthemi: the key role of SufC, an orphan ABC ATPase. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 960–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naikare, H. , Palyada, K. , Panciera, R. , Marlow, D. and Stintzi, A. (2006) Major role for FeoB in Campylobacter jejuni ferrous iron acquisition, gut colonization, and intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 74, 5433–5444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz, M. , Schroll, A. , Sonnweber, T. and Weiss, G. (2010) The struggle for iron—a metal at the host–pathogen interface. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 1691–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neema, C. , Laulhère, J.P. and Expert, D. (1993) Iron deficiency induced by chrysobactin in Saintpaulia ionantha leaves inoculated with Erwinia chrysanthemi . Plant Physiol. 102, 967–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngok‐Ngam, P. , Ruangkiattikul, N. , Mahavihakanont, A. , Virgem, S.S. , Sukchawalit, R. and Mongkolsuk, S. (2009) Roles of Agrobacterium tumefaciens RirA in iron regulation, oxidative stress response, and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2083–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nino‐Liu, D.O. , Ronald, P.C. and Bogdanove, A.J. (2006) Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars: model pathogens of a model crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7, 303–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouet, C. , Motte, P. and Hanikenne, M. (2011) Chloroplastic and mitochondrial metal homeostasis. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brian, M.R. and Fabiano, E. (2010) Mechanisms and regulation of iron homeostasis in the Rhizobia In: Iron Uptake and Homeostasis in Microorganisms (Cornelis P. and Andrews S.C., eds), pp. 37–63. Wymondham, Norfolk: Caister Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oide, S. , Moeder, W. , Krasnoff, S. , Gibson, D. , Haas, H. , Yoshioka, K. and Turgeon, B.G. (2006) NPS6, encoding a nonribosomal peptide synthetase involved in siderophore‐mediated iron metabolism, is a conserved virulence determinant of plant pathogenic ascomycetes. Plant Cell, 8, 2836–2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okinaka, Y. , Yang, C.H. , Perna, N.T. and Keen, N.T. (2002) Microarray profiling of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 genes that are regulated during plant infection. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 15, 619–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong, S.T. , Ho, J.Z. , Ho, B. and Ding, J.L. (2006) Iron‐withholding strategy in innate immunity. Immunobiology, 211, 295–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, J.G. and Ackerley, D.F. (2011) Characterization of pyoverdine and achromobactin in Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448a. BMC Microbiol. 11, 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A. and Sonti, R.V. (2010) Role of the FeoB protein and siderophore in promoting virulence of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae on rice. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3187–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persmark, M. , Expert, D. and Neilands, J.B. (1989) Isolation, characterization and synthesis of chrysobactin, a compound with a siderophore activity from Erwinia chrysanthemi . J. Biol. Chem. 264, 3187–3193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey, M. and Cianciotto, N.P. (2002) Legionella pneumophila FeoAB promotes ferrous iron uptake and intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 70, 5659–5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandy, M. and Butler, A. (2011) Chrysobactin siderophores produced by Dickeya chrysanthemi EC16. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 1207–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segond, D. , Dellagi, A. , Lanquar, V. , Rigault, M. , Patrit, O. , Thomine, S. and Expert, D. (2009) NRAMP genes function in Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Erwinia chrysanthemi infection. Plant J. 58, 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits, T.H. and Duffy, B. (2011) Genomics of iron acquisition in the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora: insights in the biosynthetic pathway of the siderophore desferrioxamine E. Arch. Microbiol. 193, 693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramoni, S. and Sonti, R.V. (2005) Growth deficiency of a Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae fur mutant in rice leaves is rescued by ascorbic acid supplementation. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 18, 644–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutak, R. , Lesuisse, E. , Tachezy, J. and Richardson, D.R. (2008) Crusade for iron: iron uptake in unicellular eukaryotes and its significance for virulence. Trends Microbiol. 16, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingle, B. , Thete, D. , Moll, M. , Myers, C.R. , Schneider, D.J. and Cartinhour, S. (2008) Characterization of the PvdS‐regulated promoter motif in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 reveals regulon members and insights regarding PvdS function in other pseudomonads. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 871–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, F. , Suzuki, T. , Inagaki, Y. , Toyoda, K. , Shiraishi, T. and Ichinose, Y. (2010) The siderophore pyoverdine of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci 6605 is an intrinsic virulence factor in host tobacco infection. J. Bacteriol. 192, 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxell, B. , Sikes, M.L. , Fink, R.C. , Vazquez‐Torres, A. , Jones‐Carson, J. and Hassan, H.M. (2011) Fur negatively regulates hns and is required for the expression of HilA and virulence in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 193, 497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visca, P. , Leoni, L. , Wilson, M.J. and Lamont, I.L. (2002) Iron transport and regulation, cell signalling and genomics: lessons from Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas . Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1177–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, E.D. (2009) Iron availability and infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1790, 600–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. , Perna, N.T. , Cooksey, D.A. , Okinaka, Y. , Lindow, S.E. , Ibekwe, A.M. , Keen, N.T. and Yang, C.H. (2004) Genome‐wide identification of plant upregulated genes of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937 using a GFP‐based IVET leaf array. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 17, 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosho, K. , Yamaji, N. , Ueno, D. , Mitani, N. and Ma, J.F. (2009) OsFRDL1 is a citrate transporter required for efficient translocation of iron in rice. Plant Physiol. 149, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. , Blumer, S.E. and Sundin, G.W. (2005) Identification of Erwinia amylovora genes induced during infection of immature pear tissue. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8088–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]