Summary

Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), caused by the Ipomoviruses Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) and Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV), is considered to be an imminent threat to food security in tropical Africa. Cassava plants were transgenically modified to generate small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) from truncated full‐length (894‐bp) and N‐terminal (402‐bp) portions of the UCBSV coat protein (ΔCP) sequence. Seven siRNA‐producing lines from each gene construct were tested under confined field trials at Namulonge, Uganda. All nontransgenic control plants (n = 60) developed CBSD symptoms on aerial tissues by 6 months after planting, whereas plants transgenic for the full‐length ΔCP sequence showed a 3‐month delay in disease development, with 98% of clonal replicates within line 718‐001 remaining symptom free over the 11‐month trial. Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) diagnostics indicated the presence of UCBSV within the leaves of 57% of the nontransgenic controls, but in only two of 413 plants tested (0.5%) across the 14 transgenic lines. All transgenic plants showing CBSD were PCR positive for the presence of CBSV, except for line 781‐001, in which 93% of plants were confirmed to be free of both pathogens. At harvest, 90% of storage roots from nontransgenic plants were severely affected by CBSD‐induced necrosis. However, transgenic lines 718‐005 and 718‐001 showed significant suppression of disease, with 95% of roots from the latter line remaining free from necrosis and RT‐PCR negative for the presence of both viral pathogens. Cross‐protection against CBSV by siRNAs generated from the full‐length UCBSV ΔCP confirms a previous report in tobacco. The information presented provides proof of principle for the control of CBSD by RNA interference‐mediated technology, and progress towards the potential control of this damaging disease.

Introduction

Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) is an emerging constraint to the production of the tropical root crop cassava (Manihot esculenta), and is considered to be one of the world's most serious threats to food security (Appel, 2011; Pennisi, 2010). The causal agents of CBSD are the viral pathogens Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) and Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV), both species of the genus Ipomovirus, family Potyviridae (Mbanzibwa et al., 2009; Winter et al., 2010). The disease is transmitted by the whitefly vector Bemisia tabaci (Maruthi et al., 2005; Mware et al., 2009) and can result from single or dual infections by these two positive single‐stranded RNA viruses (Mbanzibwa et al., 2011). Although known to have been present in East Africa since the 1930s (Storey, 1936), CBSD was mostly confined to the coastal regions and around Lake Malawi (Legg et al., 2011) until identification in Uganda in 2004 (Alicai et al., 2007). Since that time, the disease has developed to epidemic proportions, representing a significant constraint to cassava production throughout the region (Campo et al., 2011; Legg et al., 2011), with incidences reported at 93% of farmers’ fields surveyed in western Kenya (Mware et al., 2009). Unlike cassava mosaic disease (CMD), which causes distinct leaf deformation and suppressed root yields, CBSD produces yellow mottling of older leaves, stem lesions and, most importantly, brown, corky, necrotic lesions within the storage roots. The necrosis of storage roots can decrease root weight in the most sensitive cultivars by up to 70% (Hillocks et al., 2001). In addition, necrotic roots are largely inedible and have little or no value at market (Hillocks and Jennings, 2003; Hillocks et al., 2001).

Cassava is central to food and economic security throughout much of East Africa (Fermont et al., 2010; Omamo et al., 2006). The impact of CBSD therefore has important implications for smallholder farmers and rural communities within the region [Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2011; Fermont et al., 2008; United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2010]. There are also concerns that the disease is advancing south and westwards, presenting a threat to the large cassava‐producing countries of Central and West Africa (Abarshi et al., 2010; Ntawuruhunga and Legg, 2007). The development and deployment of CBSD‐resistant germplasm suited to farmers’ needs are therefore essential if the impact of the disease is to be mitigated (Legg et al., 2011).

Recently, we have reported transgenically imparted resistance to CBSD via RNA interference (RNAi) technology in tobacco (Patil et al., 2011) and cassava (Yadav et al., 2011) under controlled growth conditions. In both cases, inverted repeat constructs derived from the coat protein (CP) of UCBSV were integrated into the plant genome and were shown to result in the accumulation of transgenically derived small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) when probed with CP‐specific sequences. Inoculations were performed and resistance was assessed by the development of CBSD leaf symptoms and reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) detection of the viral pathogens. N‐terminal, C‐terminal and delta full‐length (ΔFL) inverted repeat CP sequences were shown to impart 100% resistance to challenge with the homologous virus (UCBSV) in tobacco, with levels of resistance correlated with the strength of the siRNA signal within individual transgenic plant lines (Patil et al., 2011). Graft inoculation with transgenic cassava also confirmed 100% resistance to, and exclusion of, the homologous virus by the transgenic scions (Yadav et al., 2011). Significant cross‐protection was also observed when tobacco plants accumulating high levels of UCBSV ΔFL‐CP‐derived siRNAs were challenged with CBSV (Patil et al., 2011).

In order to assess the efficacy of siRNA‐imparted resistance to CBSD under conditions of naturally vectored disease pressure, a field experiment with transgenic cassava plants was established in a confined enclosure at the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) in Namulonge, Uganda. The data reported here demonstrate that field‐grown cassava plants, transgenic for inverted repeat constructs of the UCBSV ΔCP sequence, are resistant to the homologous virus and, in some cases, capable of resisting CBSD disease development in the presence of whitefly‐transmitted CBSV and UCBSV.

Results

Prior to establishing a confined field trial (CFT) of transgenic cassava plants in November 2010, a survey was completed demonstrating that both UCBSV and CBSV were present at high incidences in the vicinity of the Namulonge research station (Table S1, see Supporting Information). Stem cuttings from plants of cultivar TME204, found to be dually infected with both viruses, were collected and used to establish infector row plants along all borders of each plot within the CFT (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information).

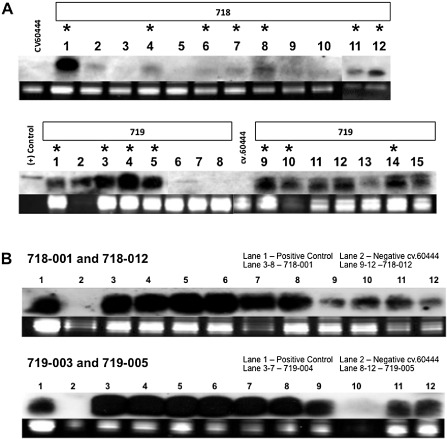

Seven independent lines of cassava cultivar 60444, transgenic for construct pILTAB718, and seven transgenic for construct pILTAB719, were selected for testing under field trial conditions. pILTAB718 carries an 894‐bp inverted repeat construct for the ΔCP of UCBSV and pILTAB719 carries a 402‐bp N‐terminal inverted repeat from the same ΔCP sequence (Patil et al., 2011). The 14 transgenic events were selected from 197 originally produced on the basis of the presence of one or two copies of the T‐DNA (Taylor et al., 2012a), detectable expression of the expected siRNA signal and, in the case of pILTAB718, performance in previously reported glasshouse graft‐inoculation studies (Yadav et al., 2011). All plant lines were shown by RT‐PCR to be free of CBSD and CMD viral pathogens prior to export from St Louis, MO, USA (results not shown). Northern blotting was also performed on these transgenic lines, confirming continued accumulation of siRNAs specific to the transgenically expressed viral sequence (Fig. 1). Sixty plants of each transgenic event, plus nontransgenic control plants of cultivar 60444 and the CBSD‐susceptible landrace Ebwanateraka, were used to establish randomized triplicated plots under CFT conditions at NaCRRI. Details of the field trial design are shown in Fig. S1.

Figure 1.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) accumulation from Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV) coat protein (CP) RNA interference (RNAi) sequences in plants transgenic for the full‐length (FL)‐ΔCP (pILTAB718) or the N‐terminus ΔCP (pILTAB719) by Northern blotting. (A) Screening of transgenic events with a CP‐specific probe for siRNA signals in leaves of in vitro plantlets. Asterisked plants were selected for the field trial in Uganda. (B) Example of siRNA expression from in vitro plants of field candidate transgenic lines prior to export from Donald Danforth Plant Science Center (DDPSC), St Louis, MO, USA to Uganda.

Development of disease symptoms on aerial tissues

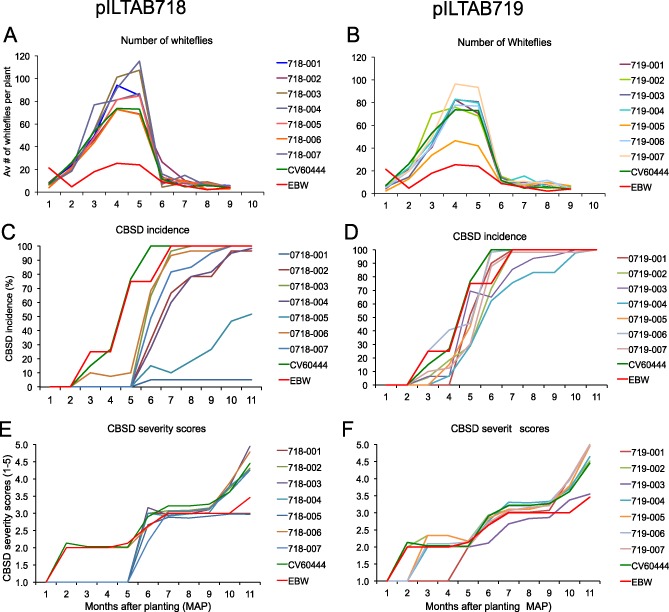

Plants were assessed for the number of whitefly vectors and the development of CBSD and CMD symptoms on a monthly basis for the 11‐month duration of the CFT. Whitefly populations increased on all control plants of cultivar 60444 and transgenic lines of pILTAB718 and pILTAB719 from the time of planting, reaching an average of 75–115 per plant by 5 months after planting (MAP) (Figs 2C, 3A,B). Elevated whitefly populations preceded the onset of CMD and CBSD (Fig. 3, Fig. S3, see Supporting Information). CMD symptom severity remained mild to moderate until 6–7 MAP (Fig. S3), and had little impact on the ability to observe CBSD symptoms on leaves and stems.

Figure 2.

Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptoms and whitefly vectors observed on leaves and stems of plants within the confined field trial. (A) Distinct yellow mottling caused by CBSD on mature leaves. (B) Dark brown coloured necrotic lesions seen on stems of CBSD‐infected plants compared with noninfected material. (C) Significant whitefly populations present on the underside of younger leaves.

Figure 3.

Development of whitefly populations and visually assessed cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptoms on shoots of transgenic and control plants over the 11‐month duration of the confined field trial. (A, B) Average number of whiteflies per plant observed on the undersides of the five uppermost leaves of transgenic pILTAB718 (A) and pILTAB719 (B) plants and nontransgenic control plants. (C, D) CBSD incidence on nontransgenic control 60444 and Ebwanateraka (EBW) cultivars and across 60 clonal replicates of seven independent transgenic lines for the inverted repeat constructs pILTAB718 (FL‐ΔCP) (C) and pILTAB719 (N‐terminal ΔCP) (D). (E, F) Severity of CBSD symptoms scored on a scale of 1–5 over time in nontransgenic control cultivars 60444 and EBW and across seven lines transgenic for the inverted repeat constructs pILTAB718 (FL‐ΔCP) (E) and pILTAB719 (N‐terminal ΔCP) (F). CP, coat protein; FL, full length.

The development of CBSD was observed as distinct yellow‐coloured mottling on mature leaves and as dark lesions on green and semi‐woody portions of the stems (Fig. 2A,B). Symptoms appeared on nontransgenic plants of cultivars 60444 and Ebwanateraka at 2–3 MAP, and attained 100% incidence by 6–7 MAP (Fig. 3C,D). Transgenic plants of pILTAB719 behaved in a similar manner, such that, by 10 MAP, all pILTAB719 transgenic plants showed typical signs of CBSD on leaves and stems (Fig. 3D). In contrast, transgenic lines expressing the FL‐ΔCP inverted repeat construct (pILTAB718) showed a delay in onset of CBSD compared with controls. Plants of lines 718‐002, 718‐003, 718‐004, 718‐006 and 718‐007 remained asymptomatic until 5 MAP, and then started to display CBSD to reach 80%–100% disease incidence by 8 MAP. In lines 718‐001 and 718‐005, symptom development was suppressed for the whole period of the CFT. In line 718‐005, final foliar CBSD incidence was 48.4% (compared with 100% for control), whereas, in transgenic line 718‐001, only one of 60 plants (1.7%) developed visible CBSD symptoms on aerial tissues over the 11‐month field trial (Fig. 3C). When plants were assessed for severity of CBSD symptoms (Fig. 3E,F, Fig. S2, see Supporting Information), those transgenic for pILTAB719 were no different from the controls, reaching an average severity score of 2.50–3.25 by 7 MAP before increasing to a maximum of 4.5–5 by the time of harvest. The severity of CBSD symptoms on diseased plants of transgenic pILTAB718 lines developed in a similar manner, except in events 718‐001 and 718‐005. In the latter, symptom severity did not develop above an average score of 3.0, whereas CBSD symptoms on the single symptomatic plant of line 718‐001 were restricted to stem tissues only, where they reached a maximum severity of 3 by 7 MAP (Fig. 3E).

RT‐PCR for detection of CBSV and UCBSV in plants within the CFT

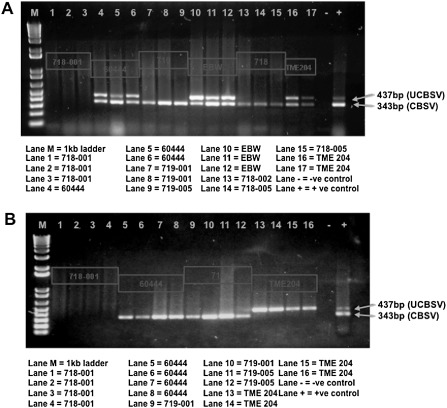

Leaf samples were collected from symptomatic plants at 5.5, 7 and 11 MAP, and diagnostic RT‐PCR was performed to detect the presence of UCBSV and CBSV. The primer set described previously by Mbanzibwa et al. (2011) was employed, allowing simultaneous diagnostic amplification of both virus species (Fig. 4). Data are presented in Table 1A–C, showing the number of plants sampled, occurrence of RT‐PCR‐detectable infections and number of plants found to be carrying single and dual infections with the CBSD causal pathogens. At 5.5 MAP, 248 symptomatic samples were analysed by RT‐PCR, with 232 (93.5%) testing positive for the presence of one or both CBSD viruses. CBSV was found to be present at high frequency throughout the season, with nontransgenic controls showing 91% infection with this virus as early as 5.5 MAP. Levels of UCBSV were somewhat lower, with 23%, 91% and 63% of nontransgenic control plants sampled shown to be infected with this pathogen at 5.5, 7 and 11 MAP, respectively. Within the nontransgenic controls, single infections with UCBSV did not exceed 12%, whereas single infections with CBSV reached 76%. Dual infection rates increased over the duration of the CFT, rising from 15% to 82% and 54% of PCR‐positive plants at 5.5, 7 and 11 MAP, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) diagnostics for simultaneous detection of Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) and Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV). (A) Presence of CBSV and UCBSV in leaf tissues of a subset of field‐grown transgenic and nontransgenic plants 11 months after planting. (B) Presence of CBSV and UCBSV in a subset of storage root tissues harvested from field‐grown transgenic and nontransgenic plants 11 months after planting. EBW, Ebwanateraka.

Table 1.

Incidence and diagnostic detection of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) within a confined field trial of transgenic and nontransgenic cassava lines at Namulonge research station

| Plant line | No. symptomatic plants (total) | No. symptomatic plants analysed by RT‐PCR | No. PCR‐positive samples | Virus species detected (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total UCBSV positiveb | Total CBSV positivec | Single infection UCBSV only | Single infection CBSV only | Dual infection UCBSV + CBSV | ||||

| (A) Incidence and diagnostics for presence of UCBSV and CBSV at 5.5 months after planting | ||||||||

| 60444 | 44 (60) | 37 | 34 | 8 (23.5) | 31 (91.2) | 3 (8.8) | 26 (76.5) | 5 (14.7) |

| EBW | 21 (24) | 45 | 43 | 24 (55.8) | 25 (58.1) | 18 (41.9) | 19 (44.2) | 6 (13.9) |

| 718‐001 | 0 (60) | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 718‐002 | 1 (60) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐003 | 4 (57) | 4 | 4 | 1 (25) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| 718‐004 | 0 (60) | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 718‐005 | 0 (60) | na | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| 718‐006 | 8 (60) | 8 | 6 | 0 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐001 | 31 (58) | 31 | 26 | 0 | 26 (100) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐002 | 16 (52) | 16 | 16 | 0 | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐003 | 23 (49) | 23 | 23 | 0 | 23 (100) | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐004 | 14 (45) | 14 | 13 | 0 | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐005 | 23 (60) | 23 | 22 | 1 | 22 (100) | 0 (0) | 21 (95.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| 719‐006 | 22 (59) | 22 | 22 | 0 | 22 (100) | 0 (0) | 22 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐007 | 21 (59) | 21 | 21 | 0 | 21 (100) | 0 (0) | 21 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 248 | 232 (93.5%) | 21 (9.1) | 198 (85.3) | 13 (5.6) | |||

| (B) Incidence and diagnostics for presence of UCBSV and CBSV at 7 months after planting | ||||||||

| 60444 | 60 (60) | 13 | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 9 (81.8) |

| EBW | 24 (24) | 12 | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (90.9) |

| 718‐001 | 1 (60) | 10a | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐002 | 40 (60) | 11 | 8 | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐003 | 55 (59) | 17 | 11 | 0 (0) | 11(100) | 0 (0) | 11(100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐004 | 35 (60) | 16 | 14 | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐005 | 6 (60) | 12 | 6 | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐006 | 56 (60) | 17 | 16 | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐007 | 46 (57) | 15 | 12 | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐001 | 57 (58) | 13 | 11 | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐002 | 51 (52) | 11 | 11 | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐003 | 42 (49) | 12 | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐004 | 33 (45) | 10 | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐005 | 60 (60) | 10 | 6 | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐006 | 59 (59) | 14 | 11 | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐007 | 58 (59) | 14 | 14 | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 198 | 166 (83.8%) | 2 (1.2) | 145 (87.3) | 19 (11.4) | |||

| (C) Incidence and diagnostics for presence of UCBSV and CBSV at 11 months after planting | ||||||||

| 60444 | 60 (60) | 30 | 26 | 17 (62.9) | 25 (92.6) | 3 (11.5) | 9 (34.6) | 14 (53.8) |

| EBW | 24 (24) | 12 | 5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| 718‐001 | 1 (60) | 30a | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐002 | 58 (60) | 12 | 5 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐003 | 58 (59) | 30 | 23 | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐004 | 59 (60) | 12 | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐005 | 29 (60) | 30 | 13 | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐006 | 60 (60) | 12 | 7 | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 718‐007 | 57 (57) | 12 | 6 | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐001 | 58 (58) | 12 | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐002 | 51 (52) | 12 | 8 | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐003 | 49 (49) | 12 | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐004 | 46 (46) | 12 | 8 | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐005 | 60 (60) | 12 | 8 | 0 (0) | 87 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐006 | 59 (59) | 12 | 8 | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 719‐007 | 58 (59) | 12 | 10 | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 235 | 145 (61.2%) | 3 (2.1) | 126 (86.9) | 16 (11.0) | |||

na, not applicable.

60444, wild‐type plants of cassava cultivar 60444; EBW, wild‐type plants of Ugandan cassava cultivar Ebwanateraka. Plants were planted in a confined field trial as triplicated randomized blocks of 20 plants.

718, plant lines transgenic for the inverted repeat construct pILTAB718 consisting of the delta full length of the UCBSV coat protein (CP); 719, plant lines transgenic for the inverted repeat construct pILTAB719 consisting of the N‐terminus of the UCBSV CP.

Leaf samples were collected from transgenic and control cassava plant lines showing CBSD symptoms and used as a source of RNA for CBSD virus detection; 1 μL of RNA was used in reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reactions (RT‐PCR) with the primer pair CBSVDF2/CBSVDR (Mbanzibwa et al., 2011) which detects and distinguishes between CBSV and UCBSV.

In this case, one symptomatic and nine asymptomatic plants were sampled.

In this case, one symptomatic and 29 asymptomatic plants were sampled.

Total positive samples showing infection with Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV) alone or UCBSV and Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV).

Total positive samples showing infection with UCBSV alone or UCBSV and CBSV.

Important differences were seen for infection rates between the transgenic plants and controls, and between plants transgenic for pILTAB718 and pILTAB719. Nontransgenic control plants of cultivars 60444 and Ebwanateraka were found to be infected with UCBSV at 23% and 42%, respectively, by 5.5 MAP, but only two of the 155 plants tested from transgenic lines pILTAB718 and pILTAB719 carried RT‐PCR‐detectable levels of this virus (Table 1A). Notably, all PCR‐positive pILTAB719 transgenic plants tested at this time were found to be infected with CBSV alone. In contrast, only three samples (all from line 718‐003) were confirmed to be carrying this virus species in plants engineered with the inverted repeat sequence for the FL‐ΔCP of UCBSV. These data correlate with information from the visual assessment of disease symptoms, which indicated that plants transgenic for pILTAB719 were diseased by 5.5 MAP, with the vast majority of pILTAB718 remaining free of CBSD at this time point (Fig. 3).

Frequencies of virus detection by RT‐PCR from leaf samples of symptomatic plants decreased as the age of the plants increased, falling from 93% at 5.5 MAP to 66% at 11 MAP. Nevertheless, across 284 symptomatic leaf samples tested by RT‐PCR at 7 and 11 MAP, no detectable infections with UCBSV were found within transgenic plants, whereas nontransgenic controls were confirmed to be carrying this virus at frequencies of 91% at 7 MAP and 66% by 11 MAP (Table 1C). Conversely, the incidence of CBSV increased in transgenic lines, such that, by the end of the trial, symptomatic plants of controls, pILTAB719 and pILTAB718 were confirmed to be infected with CBSV alone.

Thirty‐one plants (52%) and 59 plants (98%) of transgenic lines 718‐005 and 718‐001, respectively, were observed to remain free of CBSD leaf and stem symptoms for the duration of the CFT. To investigate this further, sampling was performed on a mixture of symptomatic and asymptomatic plants at 7 and 9.5 MAP. At 7 MAP, four of nine asymptomatic 718‐001 plants tested positive for the presence of CBSV, but all were negative for UCBSV (Table 1B). At 9.5 MAP, a more detailed study was performed in which RNA was extracted from leaves of different ages on the same plant and subjected to diagnostic RT‐PCR (Table 2). All three plants of nontransgenic cassava cultivar 60444 were found to carry mixed infections with UCBSV and CBSV in their older leaves (Table 2). As predicted by data from RT‐PCR analysis at 7 MAP (Table 1B), a plant from line 719‐005 was found to be infected with CBSV only, whereas, for plants of transgenic line 718‐001, leaves at all positions were determined to be free of detectable CBSD viruses. The latter included the one plant of this transgenic line that showed visible CBSD‐like symptoms on its stem tissues (Fig. 3). Further analysis was carried out on leaves from 30 plants (one symptomatic and 29 asymptomatic) of 718‐001 at 11 MAP. At this time point, neither CBSV nor UCBSV could be detected in these plants (Table 1C).

Table 2.

Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis for the presence of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) causal viruses in leaves from various positions on transgenic and nontransgenic cassava plants 9.5 months after planting

| Plant line | Plant number | CBSD severity | Leaf position | Virus present determined by RT‐PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60444 | 5 | 3 | 1 | U |

| 9 | U + V | |||

| 15 | U + V | |||

| 27 | U + V | |||

| 60444 | 14 | 3 | 1 | V |

| 8 | U + V | |||

| 15 | U + V | |||

| 23 | U + V | |||

| 60444 | 18 | 3 | 1 | V |

| 8 | V | |||

| 15 | U + V | |||

| 24 | U + V | |||

| 719‐12 | 17 | 3 | 1 | V |

| 8 | V | |||

| 15 | V | |||

| 24 | V | |||

| 718‐005 | 18 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 8 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 23 | – | |||

| 718‐001 | 5 | 3 (stem lesions only) | 1 | – |

| 9 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 24 | – | |||

| 718‐001 | 6 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 8 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 24 | – | |||

| 718‐001 | 11 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 8 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 25 | – | |||

| 718‐001 | 18 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 8 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 23 | – | |||

| 718‐001 | 15 | 1 | 1 | – |

| 9 | – | |||

| 15 | – | |||

| 23 | – |

U, Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus; V, Cassava brown streak virus.

Position of sampled leaf is indicated as that below the first fully expanded leaf (position 1), downwards. CBSD severity was determined as shown in Fig. S2.

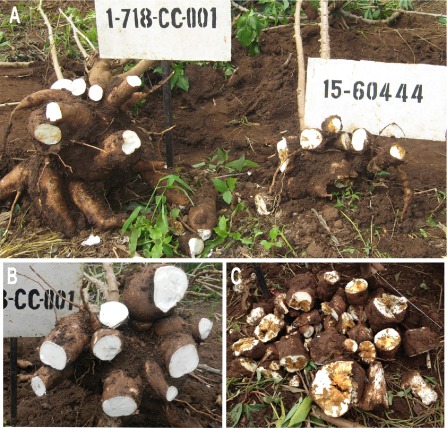

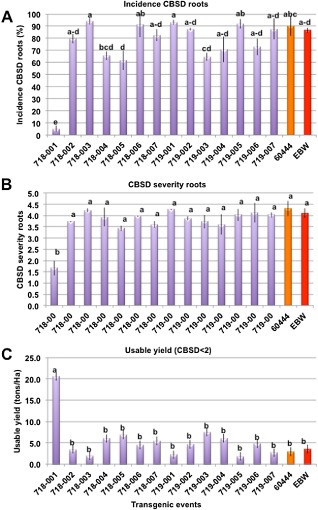

Incidence and severity of CBSD in storage roots and impact on agronomic performance

The field trial was harvested at 11 MAP. Plants were uprooted and storage roots were sliced open to allow visual scoring on a 1–5 scale for the presence and severity of the brown necrotic lesions typical of CBSD in these organs (Fig. S2). Storage roots from 16–18 plants (approximately six per triplicated plot) were assessed in this manner, and data were collected for total root production and aerial biomass. No significant differences were observed for root yields, number of roots or total biomass between 60444 control plants and the transgenic lines (Fig. S4, see Supporting Information).

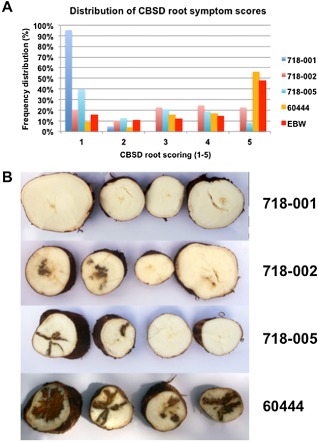

The impact of CBSD on storage root quality was severe. Of the roots harvested from nontransgenic controls of cultivar 60444, 103 of the 115 (90%) showed damage caused by CBSD, and disease symptoms were severe in these roots, with average severity scores of 4.0–4.5 (Figs 5A–C, 6B). The frequency of CBSD root symptoms was not significantly different between controls and transgenic lines of pILTAB719 and pILTAB718, except for plants of 718‐001 and 718‐005. At an average of 63%, line 718‐005 differed significantly from the 60444 control at P > 0.05, whereas transgenic event 718‐001 was significantly different from the controls and all other transgenic lines tested at P > 0.001 (Fig. 6). Importantly, storage roots from the latter event showed signs of brown lesions in only five of the 116 roots (4.4%) assessed, with symptom severity within these seen to be mild, at an average score of 2 (Figs 5A,B, 7).

Figure 5.

Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptoms on storage roots and stems at harvest, 11 months after planting. (A) Uprooted storage roots from a plant of line 718‐001 transgenic for the inverted repeat sequence ΔFL‐CP of Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV) beside a plant of the nontransgenic cultivar 60444. (B) Storage roots collected from plants of transgenic line 718‐001 showing minimal damage caused by CBSD. (C) Storage roots of nontransgenic cultivar 60444 showing severe damage caused by CBSD.

Figure 6.

Incidence and severity of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) on harvested storage roots at 11 months after planting, and its effect on usable yields across transgenic and nontransgenic plants. (A) Incidence of CBSD in storage roots. (B) Average severity of CBSD symptoms in diseased roots. Data are shown as average values from the six innermost plants of each triplicated plot ± the standard error. (C) Yield of usable roots within transgenic and nontransgenic plots. Data are shown as average values from the six innermost plants of triplicated plots ± the standard error. Values assigned different letters are significantly different at P > 0.05 as determined by Duncan's new multiple range test. EBW, Ebwanateraka.

Figure 7.

Cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptom distribution in roots from harvested transgenic and nontransgenic plants. (A) Distribution of CBSD symptom values for storage roots of the three lines transgenic for pILTAB718, control cultivar 60444 and the landrace Ebwanateraka (EBW). (B) Photographs of typical CBSD severity in slices of different roots of the three lines transgenic for pILTAB718 and the control cultivar 60444.

Diagnostic RT‐PCR performed on total RNA isolated from peeled storage roots confirmed the presence of CBSV in secondary xylem tissues from nontransgenic cultivar 60444 and pILTAB719 transgenic lines (Fig. 4B). It is not known why UCBSV was not detected in the storage roots of cultivar 60444, as these plants were diagnosed as infected with both viruses in their leaf tissues (Table 1). Interestingly, roots from four plants of the spreader row cultivar TME204 indicated the presence of UCBSV, but not CBSV, suggesting that the inability to detect UCBSV was not caused by technical failure, but may reflect biological control of virus distribution within the storage roots (Fig. 4B). Studies are ongoing to test this hypothesis. Storage roots harvested from plants of transgenic line 718‐001 were free of detectable levels of CBSV and UCBSV.

The distribution of CBSD scores for storage roots across the transgenic lines and controls at harvest is shown in Fig. 7. If roots scoring 1 (symptom free) and 2 (minimal disease and still usable) are combined, 100% and 50% of harvested roots from lines 718‐001 and 718‐005 were marketable, whereas less than 10% of the controls were fit for consumption (Fig. 7B). When combined with root yields from the CFT, the ‘usable yield’ was calculated, defined as the fresh weight of storage roots with a CBSD symptom score of 2 or less. Using this assessment, the nontransgenic cultivar 60444 yielded only 2.5 t/ha, whereas the two lines of pILTAB719 and four lines transgenic for pILTAB718 achieved usable yields above 5 t/ha, with 718‐001 delivering a usable yield equivalent to approximately 20 t/ha (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

Plants of cassava cultivar 60444 were modified to express inverted repeat constructs of the FL‐ΔCP or N‐terminal ΔCP sequences from UCBSV (Yadav et al., 2011), and were confirmed to accumulate the expected siRNAs. A CFT under high disease pressure was successfully completed to assess both RNAi‐mediated approaches for the control of CBSD under conditions of natural, whitefly‐vectored transmission at NaCRRI, Namulonge, Uganda. Infection of nontransgenic controls reached 100% within 6 MAP; moreover, transgenic plants of pILTAB719, expressing siRNAs from the N‐terminal ΔCP region of UCBSV, developed typical leaf and stem symptoms at a frequency and severity no different from the controls. In contrast, plant lines genetically modified with ΔFL‐CP displayed a 4‐month delay in development of the first CBSD symptoms, with two events, 718‐001 and 718‐005, having 98% and 52% of their clonal replicates, respectively, remaining asymptomatic over the 11‐month duration of the CFT (Fig. 3).

Molecular diagnostic analysis revealed almost complete exclusion of UCBSV in transgenic lines, whether as single infections with this pathogen or as dual infections in combination with CBSV (Table 1). Therefore, both UCBSV‐ΔCP siRNA‐expressing genetic constructs were capable of suppressing the replication of the homologous UCBSV pathogen to below RT‐PCR‐detectable levels. This was evident from RT‐PCR diagnostics of leaves from symptomatic and asymptomatic transgenic plants performed at four time points during the CFT, for which 393 of 395 samples, representing both gene constructs, were negative for the presence of UCBSV (Table 1C). It was apparent, therefore, that CBSD symptoms in transgenic plants were caused by single infections with CBSV, and this was confirmed at the molecular level, with symptomatic plants of pILTAB719 and pILTAB718 found to be infected with this pathogen only (Table 1A–C). In addition, lack of CBSD symptoms on clonal plants of transgenic line 718‐001 was correlated with the absence of UCBSV and CBSV, as determined by RT‐PCR analysis. Apart from four plants showing a positive signal for the presence of CBSV at 7 MAP, no detectable levels of UCBSV or CBSV were seen within its leaf tissues (Tables 1, 2).

The data presented here confirm the information reported previously for RNAi‐mediated resistance against CBSD by the same inverted repeat constructs under controlled growth conditions (Patil et al., 2011; Yadav et al., 2011). In glasshouse graft‐inoculation studies of cassava, all lines transgenic for pILTAB718 proved to be 100% resistant to UCBSV, with plants remaining symptom free and RT‐PCR negative for virus transmission when scions were grafted onto rootstocks infected with the homologous UCBSV species (Yadav et al., 2011). Likewise, tobacco plants genetically modified with constructs pILTAB718 and pILTAB719 (and for an inverted repeat C‐terminal version of ΔCP) provided resistance to challenge with UCBSV, but only events expressing FL‐ΔCP (pILTAB718) provided fully effective cross‐protection against infection with strains of the nonhomologous CBSV pathogen (Patil et al., 2011). Data from the field studies presented here corroborate these results, confirming that, although siRNAs from the N‐terminal CP of UCBSV are sufficient to control this virus species, the FL‐ΔCP sequence is required to generate robust resistance to both CBSD causal viruses.

Based on information from previously published reports describing RNAi‐mediated control of RNA viruses (Collinge et al., 2010; Tennant et al., 2001), inverted repeat constructs derived from the CP sequence of UCBSV were predicted to generate resistance to this virus only. Experimental evidence from the laboratory and the field studies reported here confirms, however, that a significant level of cross‐protection against CBSV is also achieved. Although the CP nucleotide sequences of the two viruses vary by 30.5% (CBSV‐[UG;Nam;04].CP.HM181930; CBSV‐[TZ;Nal].CP.HM346954), siRNAs transgenically produced by the inverted repeat UCBSV FL‐ΔCP appear to be capable of degrading the CBSV CP messenger. This is not the case for those generated by the N‐terminal RNAi construct. It is hypothesized that the siRNA population from the FL‐ΔCP RNAi construct either has special sequence properties that allow at least some of the population to recognize the CBSV CP mRNA, or that this longer fragment is differentially and better processed to siRNAs by plant Dicers. Effective cross‐protection appears to be associated with the quantity of siRNA production. In transgenic tobacco plants, cross‐resistance to CBSV was correlated with plant lines possessing the highest levels of FL‐ΔCP‐derived siRNA accumulation (Patil et al., 2011). It should be noted that line 718‐001, reported here to display greatest protection against both CBSV and UCBSV under field conditions, was seen to have a strong siRNA signal compared with other plant lines transgenic for this RNAi construct (Fig. 1). Further research is ongoing to better understand the mechanisms behind these results.

The suppression of aerial CBSD symptoms and RT‐PCR‐detectable virus in leaf tissues of plant lines 718‐001 and 718‐005 was correlated with reduced disease incidence in storage roots at the time of harvest. This result is critical, as it is damage to the storage roots that affects usable yields for farmers. Nontransgenic control plants carrying leaves infected with CBSV and/or UCBSV (Table 1) had severe damage within 90% of their storage roots (Figs 5 and 6). Tuberous roots from all plants of transgenic line pILTAB719 infected with CBSV were likewise affected. In contrast, of the 116 storage roots harvested from line 718‐001, 111 were seen to be completely free of necrotic damage caused by CBSD, with the remaining five showing only mild symptoms (Fig. 6A). The lack of detectable virus within symptom‐free storage roots of line 718‐001 confirms the data from the leaf tissues (Fig. 4, Table 1) and indicates the efficacy of UCBSV CP‐derived siRNA populations for the suppression of the agronomic impact of CBSD in this transgenic event. As a result, the yield of usable roots, those considered fit for consumption or saleable at market, was estimated to be eight times greater for line 718‐001 than for the nontransgenic controls, and significantly greater than that for other transgenic events that successfully excluded UCBSV but had little or no resistance to CBSV (Fig. 6C).

The lack of viral load in resistant plants of vegetatively propagated crops such as cassava is an essential epidemiological factor in suppressing the subsequent spread and impact of the disease (Yadav et al., 2011); (Gonsalves et al., 2007). It is apparent from the present studies that infection with CBSV alone is capable of causing severe storage root losses, and that both viral pathogens must be controlled to prevent root yield losses to CBSD. Simultaneous suppression of both CBSV and UCBSV to below detectable levels across all transgenic plants of line 718‐001 tested by RT‐PCR is therefore an important outcome of the studies reported here. Stem cuttings from plants of line pILTAB718 have been replanted to assess the impact of the disease on the vigour of the infected cuttings and to examine the continued efficacy of resistance to CBSD across vegetative generations.

The data presented here provide proof of principle for the control of CBSD by RNAi‐mediated technology and the first field‐based evidence for transgenic control of a disease in cassava. Highly effective suppression of UCBSV has been demonstrated, in addition to partial cross‐protection in one transgenic line (718‐005) and significant cross‐protection in a second (718‐001). It is hypothesized, therefore, that the co‐expression of siRNAs from the CP sequences of both UCBSV and CBSV within the same plant holds promise for the integration of robust field resistance to CBSD into farmer‐preferred cassava cultivars. Effective RNAi‐derived protection against RNA viruses has been demonstrated for papaya (Fuchs and Gonsalves, 2007), squash (Tricoll et al., 1995) and plum (Hily et al., 2004), with subsequent delivery of de‐regulated, resistant planting materials to farmers. The Virus Resistant Cassava for Africa (VIRCA) project is exploiting the knowledge gained from the present studies, and from additional ongoing CFTs, to develop CBSD‐resistant cassava for deployment to farmers and breeders in Uganda and Kenya (Taylor et al., 2012b). The results presented indicate that RNAi technology has the potential to be an important component in the multifaceted approaches being brought to mitigate the impact of CBSD on farmer well‐being in East Africa, and could be a potential strategy to combat the effects of its spread to other cassava‐producing regions.

Experimental Procedures

Plant preparation and viral diagnostics at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center (DDPSC)

In vitro plantlets of cassava cultivar 60444, transgenic for pILTAB718 (FL‐ΔCP: 7947–8840 nucleotides) and pILTAB719 (N‐terminal ΔCP: 7947–8348 nucleotides) inverted repeat constructs of the UCBSV CP gene, were generated and analysed as described previously (Taylor et al., 2012a; Yadav et al., 2011). Transgenic and nontransgenic control plantlets were micropropagated at DDPSC onto Murashige and Skoog (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) basal medium supplemented with 20 g/L sucrose (MS2) solidified with 8 g/L Noble agar. Plantlets were confirmed to be free of CMD and CBSD by diagnostic PCR. To test for the presence of CMD, DNA was extracted from in vitro leaves using the DNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, Cat. 69104, Germantown, MD, USA). African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV) was detected using primer pair JSP001 (5'‐ATGTCGAAGCGACCAGGAGAT‐3’) and JSP002 (5'‐TGTTTATTAATTGCCAATACT‐3’), as described by Pita et al. (2001), and East African cassava virus (EACMV) was detected using primers EAB555F (5'‐TACATCGGCCTTTGAGTCGCATGG‐3’) and EAB555R (5'‐CTTATTAACGCCTATATAAACACC‐3’), as reported by Fondong et al. (2000). For the detection of CBSD causal viruses, 3–5 mg of total RNA was extracted from in vitro leaves using a Total RNA MiniKit (IBI Scientific, Peosta, IA, USA), and reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase primed with oligo(dT)20 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). The resulting cDNA was used as template for PCR amplification with the universal UCBSV/CBSV primers 10F (5'‐ATCAGAATAGTGTGACTGCTGG‐3’) and CBSV 11R (5'‐CCACATTATTATCGTCACCAGG‐3’), as described by Monger et al. (2001). The accumulation of transgenically derived siRNAs within in vitro leaf tissue was confirmed in transgenic cassava plant lines by Northern blot analysis, following the procedures described by Yadav et al. (2011).

Apical shoots, 2–3 cm in length, were excised from Petri dish‐cultured plantlets and transferred to 50‐mL sterile polystyrene Falcon tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 15 mL of MS2 medium solidified with 2.2 g/L Gelzan™ (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA). One cutting was placed in each tube and cultured in a growth chamber at 28 °C with a 14 h/10 h photoperiod and 75 μmols/m2/s light. After 24 days, tubes were packaged and dispatched with the appropriate import and phytosanitary documentations via courier to NaCRRI, Namulonge, Uganda.

Hardening and soil establishment within NaCRRI screenhouses

On arrival at NaCRRI, Namulonge, Uganda, tissue culture plantlets were acclimatized in diffuse light under polythene chambers within a biosaftey level II screenhouse at 100% humidity and 24–28 °C. The caps of the 50‐mL tubes were loosened by one‐eighth of a turn each day to allow gaseous equilibration. After 4 days, the plantlets were removed from the tubes and adhering Gelzan™ was dislodged from the roots by careful agitation in warm water. Each plantlet was potted individually into a 10‐cm plastic pot containing Fafard 51 soil‐less compost (Hummert International, Earth City, MO, USA) and the medium was saturated with water. Pots were placed within the polythene chambers and 100% humidity was maintained by flooding the floor with water twice daily. After 3 days, the plantlets were moved to open benches within the same screenhouse and grown at a relative humidity of 50–60% and temperature of 26 ± 2 °C. Plants were watered as needed, and fertilizer was applied as Phyton 27 at 2 mL/L and as 9–45–15 NPK Jack's Professional Water Soluble Peat Lite fertilizer (J.R. Peters Inc., Allentown, PA, USA) at 0.5 g/L twice weekly.

Field planting, plot design, maintenance and harvesting

Plants of cassava cultivar 60444, transgenic for pILTAB718 (seven entries) and pILTAB719 (seven entries), nontransgenic control cultivar 60444 and the Ugandan farmer‐preferred landrace Ebwanateraka were used to establish a field trial under confined regulated conditions at NaCRRI, Namulonge, Uganda. Hardened plants at 8 weeks of age were transferred from the screenhouse to a CFT enclosure approximately 0.5 ha in size (51 m × 95 m). The field was prepared by ploughing twice with tractor‐mounted equipment. Plants were removed from their pots and planted into 20‐cm‐diameter, 15‐cm‐deep holes, filled with water and backfilled with soil to establish a randomized complete block experimental design with three replications. The plot configuration was 20 plants per entry (four rows wide, each with five plants) at a spacing of 1 m × 1 m (10 000 plants/ha) (Fig. S1). Stem cuttings of cassava cultivar TME204, growing in the vicinity of Namulonge research station and showing foliar symptoms of CBSD, were collected, confirmed by RT‐PCR to be infected with both CBSV and UCBSV (Table S1) and planted to form a border around and between each experimental plot (Fig. S1). Plants were watered daily for 1 week after planting and three times per week thereafter. Hand weeding was performed on a fortnightly basis. No agrochemicals or fertilizers were applied to the field.

Data collection during cultivation and at harvest

Plants were visually assessed for CBSD and CMD incidence and severity monthly until harvesting at 11 months of age. CMD symptoms were scored on all plants within the experimental plots according to the 1–5 scale reported previously (Terry, 1975). Symptoms of CBSD were assessed by combining leaf and stem symptoms, as described in Fig. S2, on all plants within the experimental plots. Plants were also assessed for the average number of adult whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci) present on the underside of the uppermost five, fully expanded leaves.

At 11 MAP, the six innermost plants within each plot were harvested by digging with a hoe to dislodge storage roots from the soil. Stem and storage root materials were cut and weighed separately using a 200‐kg scale (Hanson TM, Model no. 21, Chicago, IL, USA). ‘Marketable roots’, defined as those cylindrical or conical–cylindrical storage roots at least 18 cm in length and 4 cm in width, of the kind usually suitable for sale in the marketplace or home consumption, were separated and weighed. Each marketable sized storage root was sliced transversely into five pieces and scored for the presence and severity of CBSD using the 1–5 scale shown in Fig. S2. Each root was assigned the highest CBSD severity score observed within its slices. CBSD incidence was computed by expressing the number of CBSD‐affected roots as a percentage of the total roots per plot. The severity of CBSD per plot was obtained by averaging the individual scores of diseased storage roots (those with scores of 2–5) within the triplicated plots. ‘Usable roots’ were calculated from the total root weight as those with CBSD scores of 2 or less, assessed to be acceptable for sale or household consumption.

Statistical analysis

Field data were analysed using ARM8 (formerly called Agriculture Research Manager software, Gylling Data Management, Inc., Brookings, SD, USA) for analysis of variance (anova), and entry means were separated using Duncan's new multiple range test (P = 0.05).

Sampling and RT‐PCR analysis for the detection of UCBSV and CBSV in field‐grown plants

Unless otherwise stated, the youngest leaf showing CBSD symptoms, or equivalent noninfected tissue, was collected from field‐grown plants using gloved hands, wrapped with aluminium foil and immediately placed in a container with liquid nitrogen. To collect storage root samples, whole roots were sliced transversely into 1–2‐cm‐thick discs at harvest and a representative piece was selected and preserved in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from 0.15–0.20 g of leaf material or storage root parenchyma following the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Lodhi et al., 1994), and cDNA was synthesized using an Invitrogen SuperScript® III First‐Strand RT‐PCR Kit and oligo(dT) primers according to the manufacturer's instructions. Synthesized cDNA was subjected to UCBSV/CBSV detection by RT‐PCR according to Mbanzibwa et al. (2011), using primers CBSVDF2 (5'‐GCTMGAAATGCYGGRTAYACAA‐3’) and CBSVDR (5'‐GGATATGGAGAAAGRKCTCC‐3’) which amplify 437 and 343 nucleotides of the 3'‐terminal sequences of the UCBSV and CBSV genomes, respectively. PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel, fragments were visualized by UV radiation (302 nm) and gel images were recorded using a Nikon Coolpix P90 digital camera (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Layout of confined field trial. (A) Plants at 3 months after planting at the research station at the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI), Namulonge, Uganda, showing the experimental plants surrounded by a single border row of cultivar TME204 (foreground). (B) Schematic representation of field trial plots designed to assess transgenic small interfering RNA (siRNA)‐imparted resistance to cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). Each green square represents one 1‐m2 area containing one experimental plant, to generate 5 × 4 triplicated plots of the same clonal replicate. Each plot was surrounded on all sides by a single row of CBSD‐infected plants of cassava cultivar TME204 (yellow squares), collected locally and established from vegetative stem cuttings. The position of each transgenic and nontransgenic experimental plant line is shown within the plot design.

Fig. S2 Scoring system utilized for the visual assessment of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptoms on cassava plants within the confined field trial. (A) Scoring criteria used for the assessment of leaves and stems. (B) Scoring criteria used for the assessment of storage root tissues. (C) CBSD symptoms and associated severity scores on storage root slices.

Fig. S3 Development of cassava mosaic disease (CMD) on plants within a confined field trial designed to assess transgenic small interfering RNA (siRNA)‐imparted resistance to cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). (A, B) Incidence of CMD symptoms on experimental plants over the 11‐month trial period. (C, D) Severity of CMD symptoms on experimental plant lines as determined using a visual score of 1–5. The transgenic cassava lines for pILTAB718 are shown in (C) and those for pILTAB719 are shown in (D), with the cultivars 60444 and Ebwanateraka (EBW) as nontransgenic controls.

Fig. S4 Harvest data of plants from CBSD CFT at 11 months after planting. Bars show standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences at P > 0.05 as determined by Duncan's new multiple range test.

Table S1 Presence of Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV) and Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) within cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptomatic cassava plants in the near vicinity of Namulonge research station, September 2010. Leaf samples were collected from CBSV symptomatic plants at locations within 1 km of Namulonge research station in September 2010. CBSD leaf symptoms were scored on a scale of 1–5 for increasing severity of yellow mottling. Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) diagnostics were performed as described by Mbanzibwa et al. (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the Monsanto Fund, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) from the American people and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The authors thank Peter Raymond for help with statistical analysis, T. Jones, S. Church, D. Posey, T. Moll, A. Pranjal and H. Wagaba for preparation of plants at Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and H. Apio, J. Akol, M. Atim, P. Abidrabo, A. Abaca, F. Osingada and J. Akono for handling plants and samples in Uganda.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Abarshi, M.M. , Mohammed, I.U. , Wasswa, P. , Hillocks, R.J. , Holt, J. , Legg, J.P. , Seal, S.E. and Maruthi, M.N. (2010) Optimization of diagnostic RT‐PCR protocols and sampling procedures for the reliable and cost‐effective detection of Cassava brown streak virus. J. Virol. Methods, 163, 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicai, T. , Omongo, C.A. , Maruthi, M.N. , Hillocks, R.J. , Baguma, Y. , Kawuki, R. , Bua, A. , Otim‐Nape, G.W. and Colvin, J. (2007) Re‐emergence of cassava brown streak disease in Uganda. Plant Dis. 91, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel, C. (2011) Cassava disease threatens food security in East Africa. 16 November 2011. United Nations Radio. News and Media Available at http://www.unmultimedia.org/radio/english/2011/11/cassava‐disease‐threatens‐food‐security‐in‐east‐africa/ [accessed on May 2012].

- Campo, B.V.H. , Hyman, G. and Bellotti, A. (2011) Threats to cassava production: known and potential geographic distribution of four key biotic constraints. Food Secur. 3, 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Collinge, D.B. , Jorgensen, H.J. , Lund, O.S. and Lyngkjaer, M.F. (2010) Engineering pathogen resistance in crop plants: current trends and future prospects. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 269–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2011) FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at http://faostat.fao.org/site/339/default.aspx. [accessed on May 2012].

- Fermont, A.M. , van Asten, P.J.A. and Giller, K.E. (2008) Increasing land pressure in East Africa: the changing role of cassava and consequences for sustainability of farming systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 128, 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Fermont, A.M. , Babirye, A. , Obiero, H.M. , Abele, S. and Giller, K.E. (2010) False beliefs on the socio‐economic drivers of cassava cropping. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 30, 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Fondong, V.N. , Pita, J.S. , de Rey, M.E., Kochko, A. , Beachy, R.N. and Fauquet, C.M. (2000) Evidence of synergism between African cassava mosaic virus and a new double‐recombinant geminivirus infecting cassava in Cameroon. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, M. and Gonsalves, D. (2007) Safety of virus‐resistant transgenic plants two decades after their introduction: lessons from realistic field risk assessment studies. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves, C. , Lee, D.R. and Gonsalves, D. (2007) The adoption of genetically modified papaya in Hawaii and its implications for developing countries. J. Dev. Stud. 43, 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks, R.J. and Jennings, D.L. (2003) Cassava brown streak disease: a review of present knowledge and research needs. Int. J. Pest Manag. 49, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks, R.J. , Raya, M.D. , Mtunda, K. and Kiozia, H. (2001) Effects of brown streak virus disease on yield and quality of cassava in Tanzania. J. Phytopathol. 149, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Hily, J.M. , Scorza, R. , Malinowski, T. , Zawadzka, B. and Ravelonandro, M. (2004) Stability of gene silencing‐based resistance to Plum pox virus in transgenic plum (Prunus domestica L.) under field conditions. Transgenic Res. 13, 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legg, J.P. , Jeremiah, S.C. , Obiero, H.M. , Maruthi, M.N. , Ndyetabula, I. , Okao‐Okuja, G. , Bouwmeester, H. , Bigirimana, S. , Tata‐Hangy, W. , Gashaka, G. , Mkamilo, G. , Alicai, T. and Lava Kumar, P. (2011) Comparing the regional epidemiology of the cassava mosaic and cassava brown streak virus pandemics in Africa. Virus Res. 159, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, M.A. , Guang‐Ning, Y. , Norman, F.W. and Bruce, I.R. (1994) Simple and efficient method for DNA extraction from grapevine cultivars, Vitis species and Ampelopsis . Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 12, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maruthi, M.N. , Hillocks, R.J. , Mtunda, K. , Raya, M.D. , Muhanna, M. , Kiozia, H. , Rekha, A.R. , Colvin, J. and Thresh, J.M. (2005) Transmission of Cassava brown streak virus by Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius). J. Phytopathol. 153, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Mbanzibwa, D.R. , Tian, Y.P. , Tugume, A.K. , Mukasa, S.B. , Tairo, F. , Kyamanywa, S. , Kullaya, A. and Valkonen, J.P. (2009) Genetically distinct strains of Cassava brown streak virus in the Lake Victoria basin and the Indian Ocean coastal area of East Africa. Arch. Virol. 154, 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbanzibwa, D.R. , Tian, Y.P. , Tugume, A.K. , Mukasa, S.B. , Tairo, F. , Kyamanywa, S. , Kullaya, A. and Valkonen, J.P. (2011) Simultaneous virus‐specific detection of the two cassava brown streak‐associated viruses by RT‐PCR reveals wide distribution in East Africa, mixed infections, and infections in Manihot glaziovii . J. Virol. Methods, 171, 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monger, W.A. , Seal, S. , Isaac, A.M. and Foster, G.D. (2001) Molecular characterization of the Cassava brown streak virus coat protein. Plant Pathol. 50, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mware, B. , Narla, R. , Amata, R. , Olubayo, F. , Songa, J. , Kyamanyua, S. and Ateka, E.M. (2009) Efficiency of cassava brown streak virus transmission by two whitefly species in coastal Kenya. J. Gen. Mol. Virol. 1, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ntawuruhunga, P. and Legg, J.P. (2007) New spread of cassava brown streak virus disease and its implications for the movement of cassava germplasm in the East and Central African region. Available at http://c3project.iita.org/Doc/A25‐CBSDbriefMay6.pdf. [accessed on Mar 2012].

- Omamo, S.W. , Diao, X. , Wood, S. , Chamberlin, J. , You, L. , Benin, S. , Wood‐Sichra, U. and Tatwangire, A. (2006) Strategic priorities for agricultural development in East and Central Africa. Research Report 150. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). [Google Scholar]

- Patil, B.L. , Ogwok, E. , Wagaba, H. , Mohammed, I.U. , Yadav, J.S. , Bagewadi, B. , Taylor, N.J. , Alicai, T. , Kreuze, J.F. , Maruthi, M.N. and Fauquet, C.M. (2011) RNAi mediated resistance to diverse isolates belonging to two virus species involved in Cassava brown streak disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennisi, E. (2010) Armed and dangerous. Science, 327, 804–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pita, J.S. , Fondong, V.N. , Sangare, A. , Otim‐Nape, G.W. , Ogwal, S. and Fauquet, C.M. (2001) Recombination, pseudorecombination and synergism of geminiviruses are determinant keys to the epidemic of severe cassava mosaic disease in Uganda. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 655–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey, H.H. (1936) Virus diseases of East African plants VI. A progress report on studies of the disease of cassava. East Afr. Agric. J. 2, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. , Gaitán‐Solís, E. , Moll, T. , Trauterman, B. , Jones, T. , Pranjal, A. , Trembley, C. , Abernathy, V. , Corbin, D. and Fauquet, C.M. (2012a) A high‐throughput platform for the production and analysis of transgenic cassava (Manihot esculenta) plants. Trop. Plant Biol. 5, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, N. , Halsey, M. , Gaitán‐Solís, E. , Anderson, P. , Gichuki, S. , Miano, D. , Bua, A. , Alicai, T. and Fauquet, C. (2012b) The VIRCA Project: virus resistant cassava for Africa. GM Crops Food. 3, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, P. , Fermin, G. , Fitch, M.M. , Manshardt, R.M. , Slightom, J.L. and Gonsalves, D. (2001) Papaya ringspot virus resistance of transgenic rainbow and sunup is affected by gene dosage, plant development, and coat protein homology. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 107, 645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, E. (1975) Description and evaluation of cassava mosaic disease in Africa In: The International Exchange and Testing of Cassava Germplasm in Africa (Terry E.R. and MacIntyre R., eds), pp. 53–54. Ibadan: International Institute for Tropical Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Tricoll, D.M. , Carney, K.J. , Russell, P.F. , McMaster, J.R. , Groff, D.W. , Hadden, K.C. , Himmel, P.T. , Hubbard, J.P. , Boeshore, M.L. and Quemada, H.D. (1995) Field evaluation of transgenic squash containing single or multiple virus coat protein gene constructs for resistance to cucumber mosaic virus, watermelon mosaic virus 2, and zucchini yellow mosaic virus. Nat. Biotechnol. 13, 1458–1465. [Google Scholar]

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (2010) East Africa regional food security. Update June 2010. Available at. http://www.fews.net/east. FEWSNET. [accessed on Mar 2012].

- Winter, S. , Koerbler, M. , Stein, B. , Pietruszka, A. , Paape, M. and Butgereitt, A. (2010) The analysis of Cassava brown streak viruses reveals the presence of distinct virus species causing cassava brown streak disease in East Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 91, 1365–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, J. , Ogwok, E. , Wagaba, H. , Patil, B. , Bagewadi, B. , Alicai, T. , Gaitan‐ Solis, E. , Taylor, N. and Fauquet, C. (2011) RNAi mediated resistance to Cassava brown streak Uganda virus in transgenic cassava. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Layout of confined field trial. (A) Plants at 3 months after planting at the research station at the National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI), Namulonge, Uganda, showing the experimental plants surrounded by a single border row of cultivar TME204 (foreground). (B) Schematic representation of field trial plots designed to assess transgenic small interfering RNA (siRNA)‐imparted resistance to cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). Each green square represents one 1‐m2 area containing one experimental plant, to generate 5 × 4 triplicated plots of the same clonal replicate. Each plot was surrounded on all sides by a single row of CBSD‐infected plants of cassava cultivar TME204 (yellow squares), collected locally and established from vegetative stem cuttings. The position of each transgenic and nontransgenic experimental plant line is shown within the plot design.

Fig. S2 Scoring system utilized for the visual assessment of cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptoms on cassava plants within the confined field trial. (A) Scoring criteria used for the assessment of leaves and stems. (B) Scoring criteria used for the assessment of storage root tissues. (C) CBSD symptoms and associated severity scores on storage root slices.

Fig. S3 Development of cassava mosaic disease (CMD) on plants within a confined field trial designed to assess transgenic small interfering RNA (siRNA)‐imparted resistance to cassava brown streak disease (CBSD). (A, B) Incidence of CMD symptoms on experimental plants over the 11‐month trial period. (C, D) Severity of CMD symptoms on experimental plant lines as determined using a visual score of 1–5. The transgenic cassava lines for pILTAB718 are shown in (C) and those for pILTAB719 are shown in (D), with the cultivars 60444 and Ebwanateraka (EBW) as nontransgenic controls.

Fig. S4 Harvest data of plants from CBSD CFT at 11 months after planting. Bars show standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences at P > 0.05 as determined by Duncan's new multiple range test.

Table S1 Presence of Ugandan Cassava brown streak virus (UCBSV) and Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) within cassava brown streak disease (CBSD) symptomatic cassava plants in the near vicinity of Namulonge research station, September 2010. Leaf samples were collected from CBSV symptomatic plants at locations within 1 km of Namulonge research station in September 2010. CBSD leaf symptoms were scored on a scale of 1–5 for increasing severity of yellow mottling. Reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) diagnostics were performed as described by Mbanzibwa et al. (2011).