Summary

Plant infection by a virus is a complex process influenced by virus‐encoded factors and host components which support replication and movement. Critical factors for a successful tobamovirus infection are the viral movement protein (MP) and the host pectin methylesterase (PME), an important plant counterpart that cooperates with MP to sustain viral spread. The activity of PME is modulated by endogenous protein inhibitors (pectin methylesterase inhibitors, PMEIs). PMEIs are targeted to the extracellular matrix and typically inhibit plant PMEs by forming a specific and stable stoichiometric 1:1 complex. PMEIs counteract the action of plant PMEs and therefore may affect plant susceptibility to virus. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed genes encoding two well‐characterized PMEIs in tobacco and Arabidopsis plants. Here, we report that, in tobacco plants constitutively expressing a PMEI from Actinidia chinensis (AcPMEI), systemic movement of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is limited and viral symptoms are reduced. A delayed movement of Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV) and a reduced susceptibility to the virus were also observed in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing AtPMEI‐2. Our results provide evidence that PMEIs are able to limit tobamovirus movement and to reduce plant susceptibility to the virus.

Introduction

Viruses, as obligate parasites, have acquired the ability to utilize host factors to accumulate and diffuse in plants. The initial entry of viruses into the plant tissue occurs through mechanically damaged walls of leaf hairs and epidermal cells, as well as wounds made by insects, mites or nematodes. Thereafter, viruses accumulate and spread into the host epidermis and mesophyll cells through plasmodesmata (PD), and move systemically through the vascular system to reach noninoculated distal tissues where they continue cell‐to‐cell spread. Both cell‐to‐cell and systemic movement are processes that require interaction between viral and host components (Niehl and Heinlein, 2011). To favour infection, plant viruses induce extensive host cell remodelling, such as the modification of PD structure (Laliberté et al., 2013). For example, they have the capability to transiently increase the size exclusion limit (SEL) of PDs using virus‐encoded movement proteins (MPs), which allows viral passage into adjacent cells (Carrington et al., 1996; Ghoshroy et al., 1997; Lazarowitz and Beachy, 1999). MPs can also form ribonucleoprotein complexes with the viral genome to allow the intracellular and intercellular transport of the virus through PDs (Kehr and Buhtz, 2008; Schoelz et al., 2011).

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), the most important member of tobamovirus, causes serious losses in the yield and quality of several economically important crops, including tobacco and tomato (Scholthof et al., 2011). Multiple interactions of TMV with host components contribute to the viral infection cycle (Liu and Nelson, 2013; Pallas and Garcia, 2011). TMV replication is believed to occur mainly in an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐associated virus replication complex containing the replication proteins, MP, vRNA and host proteins. The intra‐ and intercellular transport of TMV requires a 30‐kDa MP (MPTMV), which has been shown to perform multiple functions and interacts with a variety of host proteins to promote virus movement (Liu and Nelson, 2013; Niehl and Heinlein, 2011; Pallas and Garcia, 2011). The interactions of MPTMV with cortical ER, microfilaments and microtubules assist the subcellular distribution of TMV (Liu and Nelson, 2013). Interactions of MPTMV with the plasma membrane calreticulin (Chen et al., 2005), the cytoplasmic ankirin repeat‐containing protein ANK (Ueki et al., 2010), the microtubule‐associated protein MPB2C (Kragler et al., 2003) and the end‐binding protein 1 EB1A (Brandner et al., 2008) facilitate the cell‐to‐cell movement of TMV. Furthermore, binding of MPTMV with PD‐associated casein kinase1 (PAPK) is known to phosphorylate MP, thereby modulating its movement activity (Lee et al., 2005), and the interaction of MPTMV with F‐actin has been shown to disrupt actin polymerization, possibly required to increase SEL of PD (Su et al., 2010). It has been reported recently that MPTVCV, the MP encoded by Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV), in addition to the host ER membranes and PDs, is associated with F‐actin‐containing nuclear filaments and chromosomes into the nucleus, indicating novel host interactions affecting tobamovirus movement and infection (Levy et al., 2013). Moreover, the interaction of MPTMV with cell wall‐associated pectin methylesterase (PME) has been found to be involved in the local and systemic movement of TMV (Chen and Citovsky, 2003; Chen et al., 2000; Dorokhov et al., 1999). A PME isoform from Nicotiana tabacum leaves (NtPME; EMBL accession AJ249786) has been found to interact with MPTMV and is necessary for TMV cell‐to‐cell movement (Chen et al., 2000; Dorokhov et al., 1999). Tobacco plants, in which the expression of a phloem‐specific PME isoform was reduced by antisense suppression, was shown to exhibit slower TMV systemic movement and reduced viral outcome from the vascular system (Chen and Citovsky, 2003). Tomato PMEU1 (Gaffe et al., 1997) and citrus PME3 (Nairn et al., 1998) also interact in vitro with MPs of TMV, TVCV and Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV), a virus belonging to the genus caulimovirus (Chen et al., 2000). Recently, the interaction between the MP of the furovirus Chinese wheat mosaic virus (CWMV) and PME from Nicotiana benthamiana has been reported to occur in the cell walls of epidermal cells (Andika et al., 2013). Overall, this evidence suggests that viruses of different genera could share mechanisms of local and systemic translocation mediated by the interaction of MP with plant PMEs, and that PME is a host factor affecting the development of symptoms and susceptibility.

PMEs are a large class of cell wall‐remodelling enzymes, some of which are ubiquitously expressed during the entire plant life cycle, whereas others are induced during growth and on pathogen infection (Lionetti et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2009). PMEs catalyse the demethylation of pectin and release negatively charged carboxyl groups and methanol (Mohnen, 2008) which accumulate in the intercellular spaces and mainly diffuse out of the leaves after stomatal opening (Fall and Benson, 1996; Huve et al., 2007). The activity of PME is modulated by endogenous protein inhibitors (pectin methylesterase inhibitors, PMEIs), which have been identified in many plant species (An et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2010; Raiola et al., 2004; Reca et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2010). PMEIs are targeted to the extracellular matrix and typically inhibit plant PMEs by forming a specific and stable stoichiometric 1:1 complex (Di Matteo et al., 2005). PMEIs counteract the action of plant PMEs and therefore may affect plant susceptibility towards viruses. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed genes encoding two well‐characterized PMEIs in tobacco and Arabidopsis plants. As functional PMEIs have not yet been identified in tobacco, we constitutively expressed a PMEI from Actinidia chinensis (AcPMEI) in N. tabacum. We report that the ectopic expression of AcPMEI delays the spread of TMV in tobacco, and that the overexpression of AtPMEI‐2 reduces the susceptibility of Arabidopsis to TVCV.

Results

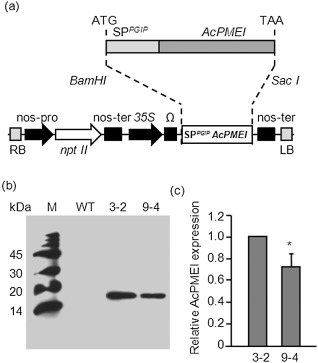

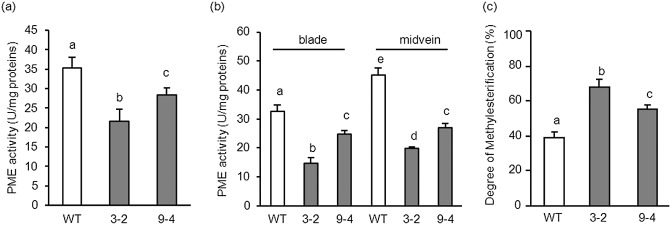

Expression of AcPMEI in tobacco inhibits PME activity and increases cell wall methylesterification

To determine whether PMEI, by interacting with plant PMEs, interferes with MP‐dependent cell‐to‐cell movement and viral systemic diffusion, we generated tobacco plants constitutively expressing the inhibitor. As functional PMEIs have not yet been identified in tobacco, the best characterized PMEIs from Arabidopsis (Hothorn et al., 2004; Raiola et al., 2004) and kiwi (AcPMEI) (Di Matteo et al., 2005) were tested against PME activity from tobacco leaves (Table 1). As a result of its greater inhibitory activity against tobacco PMEs, AcPMEI from kiwi was chosen and constitutively expressed in tobacco by Agrobacterium‐mediated leaf disc transformation. The sequence encoding the N‐terminal signal peptide of the polygalacturonase‐inhibiting protein (PGIP) from Phaseolus vulgaris was included upstream of the coding sequence of AcPMEI (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information) to target the inhibitor into the apoplast (Desiderio et al., 1997). The chimeric gene was placed under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter for constitutive expression, with the Ω leader as translation enhancer (Fig. 1a). After selection with kanamycin, 15 independent transformants exhibiting AcPMEI transcripts were obtained. The level of expression of AcPMEI in transformed lines was determined by immunoblot analysis using polyclonal antibodies generated against purified AcPMEI. The AcPMEI lines 3 and 9, both exhibiting a 3:1 Mendelian segregation ratio for the transgene, were isolated. The AcPMEI 3‐2 and 9‐4 lines homozygous for the transgene were selected for subsequent analysis. Line 3‐2 showed a 30% higher level of the inhibitor than line 9‐4 (Fig. 1b,c). AcPMEI appeared as a single band with an apparent molecular mass of 16.5 kDa (Fig. 1b), consistent with the predicted molecular mass and the absence of glycosylation sites (Di Matteo et al., 2005). When compared with wild‐type (WT) plants, PME activity was reduced by 40% in leaves of line 3‐2 and by 20% in leaves of line 9‐4 (Fig. 2a). Consistently, PME activity in the midveins and leaf blade, i.e. the tissues in which viral movement mainly occurs, was reduced by 55% and 30% in lines 3‐2 and 9‐4, respectively, indicating the ability of AcPMEI to affect tissue‐specific PME isoforms (Fig. 2b). As a consequence, the degree of methylesterification of the cell wall was increased by 70% and 45% in lines 3‐2 and 9‐4, respectively, with respect to the WT (Fig. 2c). No differences in morphology and growth were observed between transformed plants and untransformed controls.

Table 1.

Pectin methylesterase inhibitor (PMEI) activity against total PMEs from different plant leaves

| AcPMEI | AtPMEI‐1 | AtPMEI‐2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | 5 | 20 | 10 |

| Arabidopsis | 70 | 50 | 10 |

Data represent the quantity in nanograms of inhibitor required to reduce by 50% the halo of 1 cm produced by PME from crude leaf extracts.

Figure 1.

SPPGIP‐AcPMEI gene construct and expression of Actinidia chinensis pectin methylesterase inhibitor (AcPMEI) in transgenic tobacco lines. (a) Schematic diagram of AcPMEI with the secretory signal peptide of bean polygalacturonase inhibitor protein 1 (SPPGIP) and schematic representation of the expression construct, pBI121Ω‐SPPGIP‐AcPMEI, used for plant transformation. Expression of SPPGIP‐AcPMEI was driven by the Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35S), the Ω leader translation enhancer and the nopaline synthase (nos) terminator. (b) Representative Western blot analysis performed using polyclonal antibodies generated against purified AcPMEI; M, molecular weight marker; WT, wild‐type. (c) Level of AcPMEI expression in transgenic lines determined by Western blot analysis using ImageJ software. The fold change was relative to line 3‐2. Bars represent the average ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates significant difference according to Student's t‐test (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Pectin methylesterase (PME) activity and cell wall methylesterification in leaves of wild‐type (WT) and transformed tobacco plants. PME activity in leaves (a) and in leaf blade and midvein (b) of WT and transformed plants. (c) Degree of cell wall methylesterification in leaves of WT and transformed plants. Data represent average ± standard deviation (n = 6). The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. The different letters indicate datasets significantly different according to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

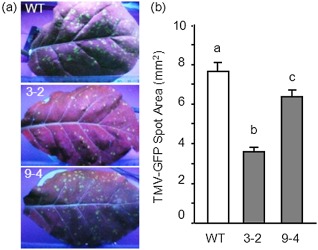

Expression of AcPMEI limits cell‐to‐cell and systemic movement of TMV in tobacco

Leaves of transformed plants were inoculated with TMV‐green fluorescent protein (TMV‐GFP) and the cell‐to‐cell translocation in leaf blades was quantified by examining the size of the bright GFP foci visible under UV light (Niehl and Heinlein, 2011). Local spread of fluorescence was reduced significantly in transgenic lines when compared with the WT. Lines 3‐2 and 9‐4 exhibited a significant reduction in the area of bright spots of about 60% and 18%, respectively (Fig. 3). Bright spots were absent in mock‐inoculated leaves of both WT and transgenic plants. The systemic spread was analysed by the appearance of visible disease symptoms and by the immunodetection of TMV‐coat protein (TMV‐CP) in leaves at different days post‐infection (dpi) using anti‐TMV‐CP antibodies (Chen and Citovsky, 2003; Ghoshroy et al., 1997). At 8 dpi, although WT plants developed typical TMV symptoms, no symptoms appeared in line 3‐2 transformed plants (Fig. 4a). The mosaic was visible in line 3‐2 with a delay of 2 days. Notably, TMV‐CP accumulation in WT leaves was detected at 6 dpi, whereas a significant delay of 2 days, as well as a reduction in viral protein, was observed in line 3‐2, and a delay of 1 day was observed in line 9‐4 (Fig. 4b,c).

Figure 3.

Accumulation of Tobacco mosaic virus‐green fluorescent protein (TMV‐GFP) in leaves of wild‐type (WT) and transformed plants. (a) GFP fluorescence of infection foci in inoculated TMV‐GFP tobacco leaves at 9 days post‐inoculation (dpi). Inoculated leaves were photographed under illumination by ultraviolet light. (b) The average area of TMV‐GFP infection foci ± standard error at 9 dpi. At least 100 spots from 10 leaves were measured in each of three independent experiments. The different letters indicate datasets significantly different according to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Delayed systemic movement of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and symptoms in wild‐type (WT) and transgenic tobacco plants. (a) TMV symptoms in systemic leaves of WT and Actinidia chinensis pectin methylesterase inhibitor (AcPMEI)‐transformed plants (line 3‐2) at 8 days post‐inoculation (dpi). (b) Representative Western blot analysis indicating TMV‐CP accumulation in the upper systemic leaves of infected WT and transformed lines at the indicated days post‐inoculation. (c) Coat protein (CP) accumulation expressed as a percentage of the maximal amount of CP measured in WT plants. Data represent average ± standard error (n = 3); the experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

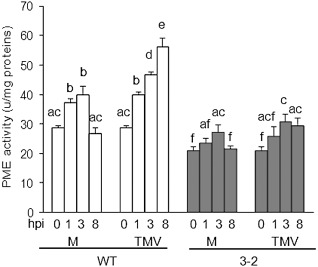

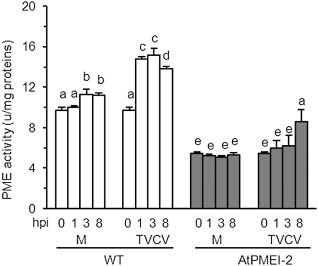

To determine whether TMV alters PMEs in tobacco, the activity of the enzyme was monitored in uninfected WT and AcPMEI plants, and in plants inoculated with the virus. PME activity in both WT and transgenic plants was induced by rubbing (mock) and by TMV infection (Fig. 5). In WT leaves, PME activity was induced early by rubbing and declined to basal levels at 8 h post‐treatment. On TMV infection, the induction was markedly higher. The level of PME activity in transgenic plants was lower than in WT plants and, notably, a significantly lower level of PME activity was induced by TMV infection (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Pectin methylesterase (PME) activity in wild‐type (WT) and transgenic tobacco plants at early stages of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) infection. The PME activity was quantified at the indicated hours post‐inoculation (hpi); M, mock‐inoculated plants; TMV, virus‐inoculated plants. Data represent average ± standard deviation (n = 6). The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. The different letters indicate datasets significantly different according to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

Overexpression of AtPMEI‐2 reduces susceptibility of Arabidopsis to TVCV

The analysis was extended to the TVCV–Arabidopsis pathosystem. As a result of the lack of evidence for binding between MP from TVCV and PMEs from Arabidopsis thaliana, we verified, by affinity chromatography, whether the viral MP interacts with the enzyme. For this purpose, a recombinant histidine‐tagged TVCV‐MP (MPHis) was expressed in Escherichia coli. Purification of MPHis gave a prevalent band with an apparent molecular mass of about 35 kDa which was detected by sodium dodecylsulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 6a,b). Other bands with a lower molecular mass were detected and represented truncated forms of the protein, probably as a result of the presence in the coding sequence of several arginine codons (AGG and/or AGA), rarely used in E. coli, and known to have a negative effect on the bacterial protein translation process (Brill et al., 2000; Rosenberg et al., 1993). Purified MPHis was immobilized on a Sepharose matrix and tested for binding to PMEs from Arabidopsis leaves. Intercellular washing fluids (IWFs) were loaded onto the MP‐Sepharose column and, following an extensive wash, the bound proteins were eluted at a high ionic strength. PME activity was recovered in the eluted fractions, indicating the ability of the MP of TVCV to bind PMEs from Arabidopsis (Fig. 6c). No PME activity was detected in fractions going through a blank Sepharose column prepared as control (Fig. 6d).

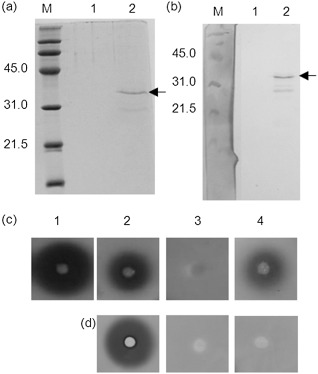

Figure 6.

Detection of recombinant Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV)‐MPHis after nickel affinity column chromatography by sodium dodecylsulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) (a) and Western blot analysis (b). M, molecular weight marker; lane 1, proteins from Escherichia coli M15 (negative control); lane 2, proteins from E. coli M15 transformed with TVCV‐MPHis. Arrows indicate the purified movement protein (MP). Pectin methylesterase (PME) activity in fractions eluted from affinity chromatography on a Sepharose column conjugated with TVCV‐MPHis (c) and from a blank Sepharose column (d): 1, intercellular washing fluids; 2, flow‐through; 3, washing; 4, proteins eluted from the columns.

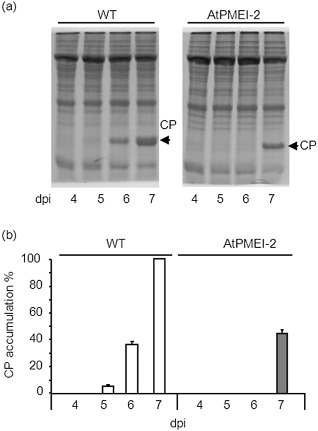

The systemic infection of TVCV was analysed in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing AtPMEI‐2 (Lionetti et al., 2007; Raiola et al., 2004), and was monitored by quantifying the accumulation of TVCV‐CP within uninoculated rosette leaves. As specific anti‐TVCV antibody is not commercially available, the accumulation of TVCV‐CP was quantified by SDS‐PAGE (Lartey et al., 1997). TVCV‐CP was detected as a band of 18 kDa at 5 dpi, whereas a smaller amount was found in transgenic leaves, with a significant delay at 7 dpi (Fig. 7a,b). PME activity was induced significantly in WT leaves by rubbing and, on TVCV treatment, the induction was markedly higher. In plants overexpressing AtPMEI‐2, the level of PME activity was lower than in WT plants, and a significantly lower activity was induced on viral infection (Fig. 8). At the early stages of infection, AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2, the best characterized Arabidopsis inhibitors (Hothorn et al., 2004; Lionetti et al., 2007; Raiola et al., 2004), were not detected by immunoblot analysis in TVCV‐treated WT leaves (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information).

Figure 7.

Systemic accumulation of Turnip vein clearing virus‐coat protein (TVCV‐CP) in rosette leaves of wild‐type (WT) and pectin methylesterase inhibitor‐overexpressing Arabidopsis (AtPMEI‐2) plants. (a) Representative sodium dodecylsulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) indicating TVCV‐CP accumulation (arrow) in systemic leaves of infected WT and AtPMEI‐2 plants at the indicated days post‐inoculation. (b) CP accumulation is expressed as a percentage of the maximal amount of CP measured in WT plants. Data represent average ± standard error (n = 3). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Figure 8.

Pectin methylesterase (PME) activity in wild‐type (WT) and transgenic Arabidopsis plants at early stages of Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV) infection. PME activity was quantified at the indicated hours post‐inoculation (hpi); M, mock‐inoculated plants; TVCV, virus‐inoculated plants. Data represent the average ± standard deviation (n = 6). The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. The different letters indicate datasets significantly different according to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The ability of a virus to move within a plant is a prerequisite for a successful infection. The interaction of MP with host PMEs is required for cell‐to‐cell movement and for the systemic spread of TMV (Burch‐Smith and Zambryski, 2012; Chen and Citovsky, 2003; Chen et al., 2000; Dorokhov et al., 1999; Pallas and Garcia, 2011). The suppression of PME isoforms involved in virus infection represents a possible strategy to counteract viral diseases. We generated tobacco plants constitutively expressing a PMEI from kiwi (AcPMEI) which efficiently interacts and strongly inhibits PMEs from several plant species (Di Matteo et al., 2005; Jolie et al., 2010; Volpi et al., 2011). The expression of AcPMEI in tobacco caused a significant reduction of PME activity in both vascular and nonvascular tissues, and an increase in cell wall methylesterification, indicating an efficient interaction of the inhibitor with PME in both tissues. As a consequence, the local and systemic translocation of TMV in transgenic tobacco plants was reduced significantly. We extended our study to A. thaliana. As TMV poorly infects Arabidopsis, we used TVCV, the tobamovirus of choice, for studies in this model plant. We showed that MPTVCV binds in vitro PMEs from Arabidopsis, and the overexpression of AtPMEI‐2 in Arabidopsis reduces the plant susceptibility to TVCV systemic movement and infection. Overall, our results show that PMEIs act on different tobamovirus–host interactions.

The importance of PME in plant susceptibility to virus is also highlighted by its induction kinetics during viral infection. Analysis of Arabidopsis gene expression on infection with Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV), Cabbage leaf curl virus (CaLCuV) and Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) showed a number of PME isoforms up‐regulated by the infection (Ascencio‐Ibanez et al., 2008; Marathe et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2007). A PME isoform (NbPME; accession AAO85706) is up‐regulated in N. benthamiana plants after TMV infection (Dorokhov et al., 2012). We found here that PME activity is induced at the early stages of infection in tobacco and Arabidopsis leaves inoculated with TMV and TVCV, respectively. The induction of PMEs probably increases the possibility of the host enzyme to cooperate with viral MPs to enlarge the PD pore and facilitate virus spread. PMEIs in both tobacco and Arabidopsis transgenic plants not only affect the existing PMEs, but also inhibit the induction of PME activities by the virus and further prevent the pathogen from exploiting a host susceptibility factor required for infection. PME activity locally modulates the degree of methylesterification known to affect cell wall mechanical properties (Mohnen, 2008; Willats et al., 2006). As PD channels are embedded in specialized cell wall regions containing cellulose, callose and nonesterified pectin (Dahiya and Brewin, 2000; Roy et al., 1997; Sutherland et al., 1999; Zavaliev et al., 2013), their gating capacity during virus infection may be affected by changes in the cell wall structure and properties modulated by PME action. The co‐localization of TMV MPs with PME in the cell wall that embeds PDs in tobacco leaves (Andika et al., 2013) suggests that PME influences the cell wall mechanical properties at the level of PDs to favour viral diffusion. Our results, demonstrating that the overexpression of PMEI increases the cell wall methylesterification of leaves and limits the viral diffusion in leaf tissues, are also consistent with this hypothesis. However, it cannot be excluded that, during viral infection, the overexpression of PMEI reduces the PME‐dependent release of methanol, which has been proposed to enlarge PDs and to facilitate viral spread (Dorokhov et al., 2012). Recently, methanol has been shown to induce the expression of a putative PMEI in N. benthamiana (Dorokhov et al., 2012). Our results indicate that AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2 expression is not induced by TVCV treatment. However, it is possible that the induction of specific PMEI isoforms is a natural response exploited by the host to restrict PME‐mediated viral infection. Consistent with this hypothesis, a high level of PMEI gene expression has been shown to be induced in potato at the early stage of infection with Potato virus Y (Kogovsek et al., 2010).

This work provides the first evidence that the overexpression in planta of biochemically characterized PMEIs limits the movement of TMV in tobacco and also delays the systemic spread of TVCV in Arabidopsis. The approach applied may possibly be extended to other important crop species. The action of PMEIs in limiting viral spread suggests that this class of inhibitor may also be utilized in breeding programmes of plant varieties less susceptible to tobamoviruses.

Experimental Procedures

Plant transformation, selection and growth

The DNA sequence containing the coding region of the AcPMEI gene (Di Matteo et al., 2005; Volpi et al., 2011), fused to the signal peptide of the bean polygalacturonase‐inhibiting protein 1 (Pvpgip1) for apoplastic targeting (Desiderio et al., 1997; Volpi et al., 2011) (Fig. S1), was inserted into the BamHI and SacI site of the pBI121(Ω) vector under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter and translation enhancer Ω leader (Hansen et al., 1994) (Fig. 1a). The pBI121Ω‐SPPGIP AcPMEI was mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 by electroporation. Leaf explants from tobacco (N. tabacum, cv SR1) were transformed, and kanamycin‐resistant plants were regenerated (Horsch et al., 1985). Primary transformants were allowed to self‐fertilize, and T0 seeds were collected and germinated on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with 300 μg/mL kanamycin. Selected seedlings were transferred into soil. T1 and T2 progeny were subjected to the same selection, and lines showing resistance to kanamycin were selected for subsequent analysis.

Reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) analysis was performed as described previously (Raiola et al., 2011) using the following oligonucleotide primers: AcPMEI Fw, 5′‐GGATCTTAAGGGTCTTGGTCA‐3′; AcPMEI Rv, 5′‐CACCATCAAAAGCAGCAGAA‐3′. The homologue of ubiquitin 5 (UBQ5; At3g62250) was amplified using the following primers: UBQ5 Fw, 5′‐GTTAAGCTCGCTGTTCTTCAGT‐3′; UBQ5 Rv, 5′‐TCAAGCTTCAACTCCTTCTTTC‐3′. Tobacco plants were grown in soil in an insect‐free controlled environment growth chamber maintained at 24 °C and 70% relative humidity, with a 16‐h/8‐h day/night cycle and a photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) leve1 of 230 μmol/m2/s. Arabidopsis plants were grown in a growth chamber maintained at 22 °C and 70% relative humidity, with a 12‐h/12‐h day/night cycle and a PAR level of 100 μmol/m2/s.

Total protein extraction and PMEI expression analysis

Total protein extracts were obtained by homogenizing leaves of adult tobacco plants in the presence of 1 m NaCl, 20 mm sodium acetate, 0.02% sodium azide, protease inhibitor 1:100, pH 5.5 (2 mL of extraction buffer per gram of tissue). The homogenate was shaken for 1.5 h at 4 °C, centrifuged at 15 000 g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentration was determined using Bradford reagent and bovine serum albumin as standard (Bradford, 1976). SDS‐PAGE was performed by loading 5 μg of protein extract for tobacco and 10 μg for Arabidopsis tissues into the gel. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously using polyclonal rabbit‐specific antibodies raised against recombinant AcPMEI, AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2, produced by Primm Biotech (Milan, Italy), and purified to homogeneity (Di Matteo et al., 2005).

Determination of PME activity and degree of methylesterification of the cell wall

PME activity in leaves of WT and AcPMEI plants was quantified by the alcohol oxidase/acetyl acetone procedure (Klavons and Bennett, 1986). Four micrograms of total proteins extracted from leaf tissues in 50 μL of protein extraction buffer were incubated with 50 μL of 0.05% apple pectin (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; cat. no 76282; 70%–75% esterification) in 0.1 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.5. The reaction was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min and blocked by boiling at 100 °C for 10 min. The solution was incubated in a 96‐microwell plate and, after the addition of 50 μL of alcohol oxidase (0.03 units in 0.1 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.5; Sigma), the samples were incubated at room temperature for 15 min on a shaker. Thereafter, 100 μL of a mixture containing 0.02 m 2,4‐pentanedione in 2 m ammonium acetate and 0.05 m acetic acid was added. After 10 min of incubation at 68 °C, samples were cooled on ice and the absorbance was measured at 412 nm in a microplate reader (Cary 50 MPR microplate reader, Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The methanol content was estimated as the amount of formaldehyde produced from methanol by alcohol oxidase, by comparison with a methanol standard calibration curve. AcPMEI [accession number P83326, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database], AtPMEI1 (accession number NP‐188348) and AtPMEI2 (accession number NP‐188348), expressed in Picha pastoris and purified as described previously (Di Matteo et al., 2005; Raiola et al., 2004), were used. The efficiency of PMEI inhibition and PME activity in Table 1 and Fig. 8 were quantified by the radial gel diffusion assay, as described previously (Lionetti et al., 2007). A commercial orange peel PME (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used to calculate the units of PME activity. The isolation of alcohol‐insoluble solids (AIS) and the analysis of uronic acid content and degree of methylesterification were performed as described previously (Lionetti et al., 2007, 2010).

Expression and purification of recombinant TVCV‐MP

TVCV‐MP was expressed as a histidine‐tagged protein using the expression vector pQE30 (The QIAexpressionist™, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The coding sequence of TVCV‐MP was amplified from pTVCV50 plasmid (containing the full‐length TVCV cDNA; (Lartey et al., 1995) with pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using the following primer pairs: 5′‐ATGCGGATCCATGTCGATAGTCTCGTACGA‐3′ and 5′‐ATGCGGTACCTTAAGCATTGGTATGGGCTC‐3′. PCR was performed in 50 μL of total reaction volume with 10 ng of plasmid pTVCV50 as follows: one cycle at 94 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 58 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final step at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplification product was isolated and cloned between the BamHI and KpnI sites (in italic in the above primer sequences) into the N‐terminal six‐histidine tag expression vector pQE30 (Qiagen). The resulting pQE30 construct (henceforth called TVCV‐MPHis‐pQE30), containing the full‐length MP gene, was used to transform the E. coli strain M15[pREP4] (Qiagen). Ni‐NTA agarose resin (His‐Select® HF Nickel Affinity Gel; Sigma) was used for purification of MPHis, and the released proteins were analysed by SDS‐PAGE and Western blot analysis. The amino acid sequence of the recombinant protein was confirmed by LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometry. After staining, the protein band was excised from the gel, reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin according to Hellman et al. (1995). Tryptic peptides were analysed by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) (LC‐ESI‐quadrupole iontrap MS 1100 Series; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) using a Zorbax SB‐C18 column (0.5 × 150 mm; particle size 5 μm), as described previously (Lionetti et al., 2007).

Isolation of PME activity by TVCV‐MP affinity chromatography

IWFs were collected from Arabidopsis rosetta leaves, as described by Lionetti et al. (2007). TVCV‐MPHis (1 mg) was covalently linked to 1 mL CNBr‐activated Sepharose (CNBr‐Sepharose® 4B, Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The column was washed with equilibration buffer (EB) containing 25 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 50 mm LiCl. IWFs (6 mL) were dialysed in EB, loaded onto the affinity MPHis‐Sepharose column and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The proteins that were not bound to the column (i.e. flow through, FT) were collected. The column was washed with 10 volumes of EB and the retained proteins were eluted with 25 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1 mm EDTA and 1 m LiCl, as described previously (Dorokhov et al., 1999). A blank Sepharose column was also prepared as a control.

Tobamovirus infection of tobacco and Arabidopsis plants

TVCV (strain PV‐0361) (DSMZ GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) and TMV (strain U1) were propagated in Arabidopsis and tobacco plants, respectively, and purified as described by Gooding and Hebert (1967) and Lartey et al. (1993). Fully expanded basal rosette (source) leaves of Arabidopsis plants at the eight‐leaf stage (three leaves for each plant) were rub inoculated with 5 μL of TVCV suspension (20 μg/mL in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and Celite at 4 mg/mL). At the indicated days post‐inoculation, two uninoculated rosette leaves (just above those inoculated) were harvested from infected plants (Lartey et al., 1997). Leaf tissue was extracted and analysed for the presence of CP by SDS‐PAGE and colloidal Coomassie Blue G staining (Sigma), as described by Lartey et al. (1997).

TMV was mechanically inoculated onto one mature lower (source) leaf located at the same basal internode of each 7‐week‐old plant by rubbing 20 μl of TMV suspension (5 μg/mL) containing 4 mg/mL carborundum as an abrasive on each leaf. At the indicated days post‐inoculation, the fourth uninoculated upper leaf, usually located three to four leaves from the top of the plant, was harvested. Systemic viral infection was monitored using the CP assay, as described by Chen and Citovsky (2003). Tissue samples were collected, extracted and analysed for the presence of CP by SDS‐PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed using anti‐TMV‐CP antibodies (1:200) (LOEWE Biochemica, Sauerlach, Germany) and alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated goat anti‐rabbit IgG as secondary antibody (1:2500) (Sigma), followed by immunodetection using 5‐bromo‐4‐chloroindol‐3‐yl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) substrate, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The amounts of CP were quantified by ImageJ software (W. S. Rasband, ImageJ; US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). To analyse AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2 expression in Arabidopsis WT plants during TVCV treatment, SDS‐PAGE was performed as described by Laemmli (1970); for each sample, 10 μg of total proteins isolated from Arabidopsis leaves were loaded onto the gel. Immunoblot blot analysis was performed, as described previously (Lionetti et al., 2007), using polyclonal antibodies generated against purified recombinant AtPMEI‐1 or AtPMEI‐2 (Raiola et al., 2004).

Detection of fluorescence in tobacco leaves inoculated with TMV expressing GFP

RNA transcripts were synthesized from TMV vector expressing GFP (Toth et al., 2002), linearized with KpnI and transcribed in vitro in the presence of cap analogue (m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G) (Promega) using RiboMAX™ Large‐Scale RNA Production Systems (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transcripts were used to rub inoculate tobacco leaves with a solution containing 50 mm of KH2PO4, pH 7.5, and 0.04% macaloid, using Celite as abrasive, and the TMV‐GFP suspension was extracted from tobacco leaves expressing GFP. Fully expanded tobacco leaves were rub inoculated with a suspension of TMV‐GFP. Inoculated leaves were photographed with a digital camera under UV illumination at 9 dpi, and the area of TMV‐GFP foci was measured by ImageJ software (W. S. Rasband, ImageJ; US National Institutes of Health).

Supporting information

Fig. S1 DNA sequence containing the coding region of the SPPGIP‐AcPMEI gene used for plant transformation. The sequence of the signal peptide of PGIP is highlighted in bold.

Fig. S2 Accumulation of AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2 in Arabidopsis wild‐type (WT) plants after Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV) treatment. Representative Western blot analysis performed at the indicated hours post‐inoculation (hpi) of TVCV on WT leaves using polyclonal antibodies generated against purified AtPMEI‐1 (a) or AtPMEI‐2 (b). C1 and C2, crude extracts from AtPMEI‐1‐ and AtPMEI‐2‐overexpressing plants, respectively, were used as control; molecular mass of protein markers is indicated on the left (top panel). Comassie staining of total proteins isolated from WT leaves after sodium dodecylsulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) is shown as a loading control (bottom panel).

Acknowledgements

TMV‐GFP construct was kindly provided by Professor Christophe Lacomme, Scottish Crop Research Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee, UK. pTVCV50 plasmid was kindly provided by Professor Ulrich Melcher, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA. This research was supported by the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant, 233083), the Institute Pasteur‐Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti and the Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca (PRIN 2010‐11 2010T7247Z).

References

- An, S.H. , Sohn, K.H. , Choi, H.W. , Hwang, I.S. , Lee, S.C. and Hwang, B.K. (2008) Pepper pectin methylesterase inhibitor protein CaPMEI1 is required for antifungal activity, basal disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance. Planta, 228, 61–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andika, I.B. , Zheng, S.L. , Tan, Z.L. , Sun, L.Y. , Kondo, H. , Zhou, X.P. and Chen, J.P. (2013) Endoplasmic reticulum export and vesicle formation of the movement protein of Chinese wheat mosaic virus are regulated by two transmembrane domains and depend on the secretory pathway. Virology, 435, 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascencio‐Ibanez, J.T. , Sozzani, R. , Lee, T.J. , Chu, T.M. , Wolfinger, R.D. , Cella, R. and Hanley‐Bowdoin, L. (2008) Global analysis of Arabidopsis gene expression uncovers a complex array of changes impacting pathogen response and cell cycle during geminivirus infection. Plant Physiol. 148, 436–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandner, K. , Sambade, A. , Boutant, E. , Didier, P. , Mely, Y. , Ritzenthaler, C. and Heinlein, M. (2008) Tobacco mosaic virus movement protein interacts with green fluorescent protein‐tagged microtubule end‐binding protein 1. Plant Physiol. 147, 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill, L.M. , Nunn, R.S. , Kahn, T.W. , Yeager, M. and Beachy, R.N. (2000) Recombinant tobacco mosaic virus movement protein is an RNA‐binding, alpha‐helical membrane protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7112–7117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch‐Smith, T.M. and Zambryski, P.C. (2012) Plasmodesmata paradigm shift: regulation from without versus within. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 239–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, J.C. , Kasschau, K.D. , Mahajan, S.K. and Schaad, M.C. (1996) Cell‐to‐cell and long‐distance transport of viruses in plants. Plant Cell, 8, 1669–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.‐H. and Citovsky, V. (2003) Systemic movement of a tobamovirus requires host cell pectin methylesterase. Plant J. 35, 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.H. , Sheng, J. , Hind, G. , Handa, A.K. and Citovsky, V. (2000) Interaction between the tobacco mosaic virus movement protein and host cell pectin methylesterases is required for viral cell‐to‐cell movement. EMBO J. 19, 913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.H. , Tian, G.W. , Gafni, Y. and Citovsky, V. (2005) Effects of calreticulin on viral cell‐to‐cell movement. Plant Physiol. 138, 1866–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, P. and Brewin, N.J. (2000) Immunogold localization of callose and other cell wall components in pea nodule transfer cells. Protoplasma, 214, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Desiderio, A. , Aracri, B. , Leckie, F. , Mattei, B. , Salvi, G. , Tigelaar, H. , Van Roekel, J.S. , Baulcombe, D.C. , Melchers, L.S. , De Lorenzo, G. and Cervone, F. (1997) Polygalacturonase‐inhibiting proteins (PGIPs) with different specificities are expressed in Phaseolus vulgaris . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 10, 852–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo, A. , Giovane, A. , Raiola, A. , Camardella, L. , Bonivento, D. , De Lorenzo, G. , Cervone, F. , Bellincampi, D. and Tsernoglou, D. (2005) Structural basis for the interaction between pectin methylesterase and a specific inhibitor protein. Plant Cell, 17, 849–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorokhov, Y.L. , Makinen, K. , Frolova, O.Y. , Merits, A. , Saarinen, J. , Kalkkinen, N. , Atabekov, J.G. and Saarma, M. (1999) A novel function for a ubiquitous plant enzyme pectin methylesterase: the host‐cell receptor for the tobacco mosaic virus movement protein. FEBS Lett. 461, 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorokhov, Y.L. , Komarova, T.V. , Petrunia, I.V. , Frolova, O.Y. , Pozdyshev, D.V. and Gleba, Y.Y. (2012) Airborne signals from a wounded leaf facilitate viral spreading and induce antibacterial resistance in neighboring plants. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall, R. and Benson, A.A. (1996) Leaf methanol—the simplest natural product from plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1, 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffe, J. , Tiznado, M.E. and Handa, A.K. (1997) Characterization and functional expression of a ubiquitously expressed tomato pectin methylesterase. Plant Physiol. 114, 1547–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshroy, S. , Lartey, R. , Sheng, J.S. and Citovsky, V. (1997) Transport of proteins and nucleic acids through plasmodesmata. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 25–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding, G.V., Jr and Hebert, T.T. (1967) A simple technique for purification of tobacco mosaic virus in large quantities. Phytopathology, 57, 1285–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, G. , Das, A. and Chilton, M.‐D. (1994) Constitutive expression of the virulence genes improves the efficiency of plant transformation by Agrobacterium . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 7603–7607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, U. , Wernstedt, C. , Gonez, J. and Heldin, C.H. (1995) Improvement of an ‘In‐Gel’ digestion procedure for the micropreparation of internal protein fragments for amino acid sequencing. Anal. Biochem. 224, 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M.J. , Kim, D.J. , Lee, T.G. , Jeon, W.B. and Seo, Y.W. (2010) Functional characterization of pectin methylesterase inhibitor (PMEI) in wheat. Genes Genet. Syst. 85, 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch, R.B. , Fry, J.E. , Hoffmann, N.L. , Eichholtz, D. , Rogers, S.G. and Fraley, R.T. (1985) A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science, 227, 1229–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, M. , Wolf, S. , Aloy, P. , Greiner, S. and Scheffzek, K. (2004) Structural insights into the target specificity of plant invertase and pectin methylesterase inhibitory proteins. Plant Cell, 16, 3437–3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huve, K. , Christ, M.M. , Kleist, E. , Uerlings, R. , Niinemets, U. , Walter, A. and Wildt, J. (2007) Simultaneous growth and emission measurements demonstrate an interactive control of methanol release by leaf expansion and stomata. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolie, R.P. , Duvetter, T. , Van Loey, A.M. and Hendrickx, M.E. (2010) Pectin methylesterase and its proteinaceous inhibitor: a review. Carbohydr. Res. 345, 2583–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr, J. and Buhtz, A. (2008) Long distance transport and movement of RNA through the phloem. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klavons, J.A. and Bennett, R.D. (1986) Determination of methanol using alcohol oxidase and its application to methyl ester content of pectins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 34, 597–599. [Google Scholar]

- Kogovsek, P. , Pompe‐Novak, M. , Baebler, S. , Rotter, A. , Gow, L. , Gruden, K. , Foster, G.D. , Boonham, N. and Ravnikar, M. (2010) Aggressive and mild Potato virus Y isolates trigger different specific responses in susceptible potato plants. Plant Pathol. 59, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Kragler, F. , Curin, M. , Trutnyeva, K. , Gansch, A. and Waigmann, E. (2003) MPB2C, a microtubule‐associated plant protein binds to and interferes with cell‐to‐cell transport of tobacco mosaic virus movement protein. Plant Physiol. 132, 1870–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté, J.‐F. , Moffett, P. , Sanfacon, H. , Wang, A. , Nelson, R.S. and Schoelz, J.E. (2013) e‐Book on plant virus infection—a cell biology perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartey, R. , Ghoshroy, S. , Ho, J. and Citovsky, V. (1997) Movement and subcellular localization of a tobamovirus in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 12, 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartey, R.T. , Hartson, S.D. , Pennington, R.E. , Sherwood, J.L. and Melcher, U. (1993) Occurrence of a vein‐clearing tobamovirus in turnip. Plant Dis. 77, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lartey, R.T. , Voss, T.C. and Melcher, U. (1995) Completion of a cDNA sequence from a tobamovirus pathogenic to crucifers. Gene, 166, 331–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowitz, S.G. and Beachy, R.N. (1999) Viral movement proteins as probes for intracellular and intercellular trafficking in plants. Plant Cell, 11, 535–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y. , Taoka, K. , Yoo, B.C. , Ben Nissan, G. , Kim, D.J. and Lucas, W.J. (2005) Plasmodesmal‐associated protein kinase in tobacco and Arabidopsis recognizes a subset of non‐cell‐autonomous proteins. Plant Cell, 17, 2817–2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. , Zheng, J.Y. and Lazarowitz, S.G. (2013) The tobamovirus turnip vein clearing virus 30‐kilodalton movement protein localizes to novel nuclear filaments to enhance virus infection. J. Virol. 87, 6428–6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti, V. , Raiola, A. , Camardella, L. , Giovane, A. , Obel, N. , Pauly, M. , Favaron, F. , Cervone, F. and Bellincampi, D. (2007) Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea . Plant Physiol. 143, 1871–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti, V. , Francocci, F. , Ferrari, S. , Volpi, C. , Bellincampi, D. , Galletti, R. , D'Ovidio, R. , De Lorenzo, G. and Cervone, F. (2010) Engineering the cell wall by reducing de‐methyl‐esterified homogalacturonan improves saccharification of plant tissues for bioconversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 616–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionetti, V. , Cervone, F. and Bellincampi, D. (2012) Methyl esterification of pectin plays a role during plant–pathogen interactions and affects plant resistance to diseases. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 1623–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. and Nelson, R.S. (2013) The cell biology of Tobacco mosaic virus replication and movement. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe, R. , Guan, Z. , Anandalakshmi, R. , Zhao, H.Y. and Dinesh‐Kumar, S.P. (2004) Study of Arabidopsis thaliana resistome in response to cucumber mosaic virus infection using whole genome microarray. Plant Mol. Biol. 55, 501–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen, D. (2008) Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairn, C.J. , Lewandowski, D.J. and Burns, J.K. (1998) Genetics and expression of two pectinesterase genes in Valencia orange. Physiol. Plant. 102, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Niehl, A. and Heinlein, M. (2011) Cellular pathways for viral transport through plasmodesmata. Protoplasma, 248, 75–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas, V. and Garcia, J.A. (2011) How do plant viruses induce disease? Interactions and interference with host components. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 2691–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiola, A. , Camardella, L. , Giovane, A. , Mattei, B. , De Lorenzo, G. , Cervone, F. and Bellincampi, D. (2004) Two Arabidopsis thaliana genes encode functional pectin methylesterase inhibitors. FEBS Lett. 557, 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiola, A. , Lionetti, V. , Elmaghraby, I. , Immerzeel, P. , Mellerowicz, E.J. , Salvi, G. , Cervone, F. and Bellincampi, D. (2011) Pectin methylesterase is induced in Arabidopsis upon infection and is necessary for a successful colonization by necrotrophic pathogens. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 24, 432–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reca, I.B. , Lionetti, V. , Camardella, L. , D'Avino, R. , Giardina, T. , Cervone, F. and Bellincampi, D. (2012) A functional pectin methylesterase inhibitor protein (SolyPMEI) is expressed during tomato fruit ripening and interacts with PME‐1. Plant Mol. Biol. 79, 429–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, A.H. , Goldman, E. , Dunn, J.J. , Studier, F.W. and Zubay, G. (1993) Effects of consecutive agg codons on translation in Escherichia‐coli, demonstrated with a versatile codon test system. J. Bacteriol. 175, 716–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. , Watada, A.E. and Wergin, W.P. (1997) Characterization of the cell wall microdomain surrounding plasmodesmata in apple fruit. Plant Physiol. 114, 539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoelz, J.E. , Harries, P.A. and Nelson, R.S. (2011) Intracellular transport of plant viruses: finding the door out of the cell. Mol. Plant, 4, 813–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholthof, K.B.G. , Adkins, S. , Czosnek, H. , Palukaitis, P. , Jacquot, E. , Hohn, T. , Hohn, B. , Saunders, K. , Candresse, T. , Ahlquist, P. , Hemenway, C. and Foster, G.D. (2011) Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 938–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, S.Z. , Liu, Z.H. , Chen, C. , Zhang, Y. , Wang, X. , Zhu, L. , Miao, L. , Wang, X.C. and Yuan, M. (2010) Cucumber mosaic virus movement protein severs actin filaments to increase the plasmodesmal size exclusion limit in tobacco. Plant Cell, 22, 1373–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, P. , Hallett, L. , Redgwell, R. , Benhamou, N. and MacRae, E. (1999) Localization of cell wall polysaccharides during kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) ripening. Int. J. Plant Sci. 160, 1099–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth, R.L. , Pogue, G.P. and Chapman, S. (2002) Improvement of the movement and host range properties of a plant virus vector through DNA shuffling. Plant J. 30, 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki, S. , Spektor, R. , Natale, D.M. and Citovsky, V. (2010) ANK, a host cytoplasmic receptor for the tobacco mosaic virus cell‐to‐cell movement protein, facilitates intercellular transport through plasmodesmata. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpi, C. , Janni, M. , Lionetti, V. , Bellincampi, D. , Favaron, F. and D'Ovidio, R. (2011) The ectopic expression of a pectin methyl esterase inhibitor increases pectin methyl esterification and limits fungal diseases in wheat. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 24, 1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willats, W.G.T. , Knox, P. and Mikkelsen, J.D. (2006) Pectin: new insights into an old polymer are starting to gel. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 17, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S. , Mouille, G. and Pelloux, J. (2009) Homogalacturonan methyl‐esterification and plant development. Mol. Plant 2, 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.L. , Guo, R. , Jie, F. , Nettleton, D. , Peng, J.Q. , Carr, T. , Yeakley, J.M. , Fan, J.B. and Whitham, S.A. (2007) Spatial analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana gene expression in response to Turnip mosaic virus infection. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 20, 358–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaliev, R. , Levy, A. , Gera, A. and Epel, B.L. (2013) Subcellular dynamics and role of Arabidopsis β‐1,3‐glucanases in cell‐to‐cell movement of tobamoviruses. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 26, 1016–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.Y. , Feng, J. , Wu, J. and Wang, X.W. (2010) BoPMEI1, a pollen‐specific pectin methylesterase inhibitor, has an essential role in pollen tube growth. Planta, 231, 1323–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 DNA sequence containing the coding region of the SPPGIP‐AcPMEI gene used for plant transformation. The sequence of the signal peptide of PGIP is highlighted in bold.

Fig. S2 Accumulation of AtPMEI‐1 and AtPMEI‐2 in Arabidopsis wild‐type (WT) plants after Turnip vein clearing virus (TVCV) treatment. Representative Western blot analysis performed at the indicated hours post‐inoculation (hpi) of TVCV on WT leaves using polyclonal antibodies generated against purified AtPMEI‐1 (a) or AtPMEI‐2 (b). C1 and C2, crude extracts from AtPMEI‐1‐ and AtPMEI‐2‐overexpressing plants, respectively, were used as control; molecular mass of protein markers is indicated on the left (top panel). Comassie staining of total proteins isolated from WT leaves after sodium dodecylsulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) is shown as a loading control (bottom panel).