Abstract

Purpose:

It is unknown whether receipt of evidence-based alcohol-related care varies by rurality among people living with HIV (PLWH) with unhealthy alcohol use—a population for whom such care is particularly important.

Methods:

All positive screens for unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥ 5) among PLWH were identified using Veterans Health Administration electronic health record data (10/1/09–5/30/13). Three domains of alcohol-related care were assessed: brief intervention (BI) within 14 days, and specialty addictions treatment or alcohol use disorder (AUD) medications (filled prescription for naltrexone, disulfiram, acamprosate, or topiramate) within 1 year of positive screen. Adjusted Poisson models and recycled predictions were used to estimate predicted prevalence of outcomes across rurality (urban, large rural, small rural), clustered on facility. Secondary analyses assessed outcomes in the subsample with documented AUD.

Findings:

4,581 positive screens representing 3,458 PLWH (3,112 urban, 130 large rural, and 216 small rural) were included; 49.1% had diagnosed AUD. PLWH in large rural areas had highest receipt of BI [Urban: 56.6%, 95% Confidence Interval (55.0–58.2); Large Rural: 66.0% (58.6–73.5); Small Rural: 60.7% (54.6–67.0)]. PLWH in urban areas had highest receipt of specialty addictions treatment [Urban: 28.2% (26.7–29.8); Large Rural: 19.7% (13.1–26.2); Small Rural: 19.6% (14.1–25.0)]. There was no difference in receipt of AUD medications, although overall receipt was low (between 3–4%). Results were similar in the subsample with AUD.

Conclusion:

Among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use, those in rural areas may be vulnerable to under-receipt of specialty addictions treatment. Targeted interventions may help ensure PLWH receive recommended care regardless of rurality.

Keywords: rural, urban, HIV, alcohol-related care, veterans

INTRODUCTION

Among people living with HIV (PLWH), unhealthy alcohol use is associated with poor HIV-related outcomes, including increased risk of HIV transmission, delayed entry to treatment, non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy, greater disease severity, and mortality.1–3 There are several evidence-based clinical practices recommended for patients with unhealthy alcohol use: brief interventions (clinician advice to reduce or abstain from alcohol use) are recommended for all primary care patients who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use,4–6 while specialty addictions treatment7,8 and alcohol use disorder (AUD) medications9 are additionally recommended for those with AUD.

Among patients with unhealthy alcohol use, PLWH are less likely to receive alcohol-related care10–12 than patients without HIV.10,12 Among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use, receipt of alcohol-related care may be even less likely among certain vulnerable subpopulations of PLWH, such as those living in more rural areas. Previous studies show that, among those reporting any alcohol use in the general population, those living in rural areas may experience increased and unique barriers to alcohol-related care.13–15 Although rural areas are heterogeneous in population density, size, and geographic barriers to care, PLWH who live in rural areas often have delayed or decreased access to other needed healthcare relative to those living in urban areas,16 and specifically among PLWH, delayed access to HIV testing and treatment.17,18 However, no studies have described differences in receipt of alcohol-related care based on place of residence among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use—a population for whom alcohol-related care may be particularly important.19

In the national Veterans Health Administration (VA)—the largest integrated healthcare system in the U.S.— delivery of both alcohol screening (to identify patients with unhealthy alcohol use) and brief intervention (for those screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use) are incentivized by national performance measures.4,20,21 The vast majority of VA outpatients are annually screened for unhealthy alcohol use with the 3-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C),21 including patients with HIV.22 And, though not incentivized by performance measures, specialty addictions treatment and AUD medications are recommended in VA’s clinical guideline for treatment of substance use disorders and routinely monitored as part of quality improvement.23 The VA is also the largest provider of HIV care in the U.S. Therefore, national VA data provide a unique opportunity to describe differences in receipt of alcohol-related care based on place of residence among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use. The aim of the present study was to describe receipt of three elements of evidence-based alcohol-related care across rural status among PLWH who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use at the VA over a 5 year period. We hypothesized that PLWH living in more rural areas would be less likely to receive alcohol-related care than those living in more urban areas.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Sample.

This study reflects a secondary analysis of data collected for a larger study that assessed differences in receipt and effectiveness of alcohol-related care across HIV status in the VA.12,24 For the larger study, data were extracted for all VA patients with an outpatient appointment and documentation of 1 or more positive screens for unhealthy alcohol use between October 1, 2009 and May 30, 2013 from the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructures (VINCI) Corporate Data Warehouse, which contains clinical, enrollment, financial, administrative, pharmacy, and utilization data from the VA electronic health record (EHR). For the present study, patients also had to have: 1) a documented diagnosis for HIV/AIDS in the 2 years prior to positive alcohol screening, and 2) a documented residential zip code that corresponded to a Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) code.25 Positive alcohol screens were defined as a score of 5 or more on the AUDIT-C questionnaire, in order to be consistent with the denominator specification for VA’s performance measure for brief intervention.21,23 Though AUDIT-C scores of 3 or more for women and 4 or more for men optimize both sensitivity and specificity for assessing unhealthy alcohol use in validation studies,20,26–28 the VA’s performance measure requires provision of brief intervention among only patients with scores of 5 or more to increase specificity and thus reduce clinical burden associated with false positive results.29 HIV status was based on International Classification of Disease Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, consistent with prior HIV research in the VA.30 All positive AUDIT-C screens were followed for 1 year (up to May 30, 2014) to assess outcomes. This study was approved by the VA Puget Sound Institutional Review Board.

Rurality measure:

Rurality was measured by applying RUCA codes, developed by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy to assess commuting times and proximity to urban areas,25 to patients’ home zip codes. Patient zip code was assessed on the closest available date to the AUDIT-C screening within 1 year prior to each positive AUDIT-C. RUCA codes were based on the 2010 decennial census and 2006–2010 American Community Survey to categorize patients into 3 groups: 1) urban, 2) large rural, and small/isolated rural (including small town/remote categories), as recommended by the Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (WWAMI) Region Rural Health Research Center.31 RUCA codes were collapsed into 3 categories from 33 unique codes to increase interpretability of results and collapse groups with small sample sizes.

Receipt of alcohol-related care:

Three measures reflecting elements of evidence-based care for unhealthy alcohol use were used. Receipt of brief intervention (BI) was measured based on EHR documentation of advice to reduce or abstain from drinking within 14 days of a positive AUDIT-C screen.21 This measure is derived from data generated when care is documented using electronic clinical decision support, which is commonly used in VA to prompt and document care incentivized by performance measures.23 This measure has been previously used to measure receipt of BI,6,12,32 is consistent with what is required in VA’s national performance measure for brief intervention,6,21 and corresponds well with patient reported receipt of brief intervention.5,33 Additionally, we measured receipt of specialty addictions treatment and receipt of AUD medications in the year following each positive screen. Receipt of specialty addictions treatment (eg, psychosocial interventions in a specialty care setting) was measured based on outpatient clinic stop codes and inpatient bed section codes for any substance use disorder treatment in a specialty care setting with accompanying AUD diagnosis.12,34,35 Receipt of AUD medications was measured based on a filled prescription for acamprosate, disulfiram, topiramate, or oral or injectable naltrexone, similar to previous studies.12,36 AUD medications can be prescribed across treatment settings and have demonstrated efficacy for decreasing alcohol use by decreasing cravings, relieving withdrawal symptoms, or intensifying adverse acute reactions to alcohol.23 These medications were selected based on having FDA approval for treatment of AUD or strong meta-analytic support for their use in the treatment of AUD, and to be consistent with VA clinical guidelines for substance use disorder treatment at the time of data collection.9,23

Covariates:

Several groups of covariates were measured at the time of the positive AUDIT-C screen. Fiscal year of positive screening was measured based on the date of positive screening (categorized from 10/1 to 9/30 for each year in the study period) to account for time trends in receipt of care during the study period. Age was measured in years, categorized as <50, 50–64, and ≥65. Age categories were selected to reflect the skewed age distribution of patients, because they have been used in other VA studies,37,38 and because they meaningfully capture age differences related to Medicare eligibility. A continuous measure of age was also considered, but goodness of fit testing indicated that a categorical measure improved model fit. Gender was measured as male or female based on EHR documentation. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, or other as recommended by the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB).39 VA eligibility status, or priority status, was determined by a combination of service-connected disability and income, and was measured in categories including full VA coverage, <50% service connected coverage, or non-service connected coverage. This was used as an imperfect proxy for socioeconomic status, similar to previous VA studies of prevalence of alcohol use40 and alcohol-related treatment.34 Marital status was obtained from the EHR and categorized as divorced/separated, never married/single, married, or widowed. Region was measured consistent with Census definitions as West, Midwest, South, and Northeast, derived using zip codes.

Comorbid mental health and substance use diagnoses, along with healthcare utilization, were measured using ICD-9-CM codes documented in the 0–365 days prior to the positive alcohol screen. Documented mental health disorders included depressive disorders, PTSD, anxiety disorders, or serious mental illnesses (bipolar, psychosis, and schizophrenia). Non-alcohol substance use disorders included any stimulant use disorder, opioid use disorder, or other (cannabis, hallucinogen, or sedative) disorder. Tobacco use was measured in two ways: 1) documented tobacco use disorder, or 2) documentation of tobacco screening data indicating current smoker status.41 Severity of unhealthy alcohol use included past year AUD (abuse or dependence) and past year alcohol-specific condition (Alcoholic polyneuropathy, Alcoholic cardiomyopathy, Alcoholic gastritis, Alcoholic fatty liver, Acute alcoholic hepatitis, Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver, and Alcoholic liver damage). Additionally, levels of unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C categories of 5–8 relative to 9–12) were described. Two measures of health services utilization were derived: 1) number of outpatient visits (categorized as 0, 1–4, 5–10, 11–24, or ≥ 25 visits), and 2) number of inpatient days (categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, and ≥4 days), both measured in the 0–365 days prior to the positive alcohol screen. Finally, patient facility was measured based on the facility (and corresponding main medical center) in which AUDIT-C screening was conducted using the VA 3-digit station number.

ANALYSES

Patient-level descriptive analyses based on each patients’ first positive screen for unhealthy alcohol use were conducted to describe and compare population characteristics across rurality using chi-square tests of independence. Only 1 variable (marital status) had missing values (n=38, 1.1% of sample), and a category indicating missingness was created for this variable. Next, using all positive screens as the unit of analysis, Poisson regression models were used to obtain the relative risk of receiving each alcohol-related care outcome for large and small rural relative to urban PLWH. As it was hypothesized that the receipt of care would decrease as rurality increased, ordinal tests were used to test for trends in each outcome across increasing rurality (between urban and large rural, and between large rural and small rural). Recycled predictions (ie, a fitted model in which covariates are fixed for each level of rurality)42 were used to obtain the predicted prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of each alcohol-related care outcome for PLWH living in each rurality designation.43 Average marginal effects were used to compare differences in predicted prevalences between rurality categories when overall significant differences across rurality were identified, to assess the magnitude of differences in care receipt.

Three iteratively adjusted models were run for each outcome to account for potential confounding and to identify possible mechanisms explaining the association between rurality and receipt of care among PLWH: 1) a model adjusted only for fiscal year to account for time trends in receipt of alcohol-related care, 2) a partially adjusted model adjusted for fiscal year, along with age,44 gender,45 race/ethnicity,46,47 VA eligibility status,16 marital status,48 and region,16,47 and 3) a fully adjusted model, adjusted additionally for diagnosed mental health disorders, non-alcohol substance use disorders, tobacco use, severity of unhealthy alcohol use, and health services utilization. All models were clustered on facility to account for correlation within VA facilities, and to account for conservative estimates due to use of a Poisson model with binary data.49 In primary analyses, standard errors were calculated using the delta method. We secondarily calculated standard errors using bootstrapping methods to assess possible bias by small population sizes for some models. Results were unchanged, thus only primary models using the delta method are reported here. Finally, we conducted secondary analyses to evaluate associations between rurality and receipt of specialty addictions treatment and AUD medications among only positive screens that also had an AUD diagnosis documented in the year prior to positive screening, because these interventions are clinically recommended specifically for patients with AUD.23 All analyses were conducted using Stata v14.

RESULTS:

There were 3,459 PLWH who met eligibility criteria, including 3,113 from urban areas, 130 from large rural areas, and 216 from small rural areas. Of these, 49.1% had a documented AUD (n=1,699), including 1,539 from urban areas, 54 from large rural areas, and 106 from small rural areas. When all positive screens in the study period were considered, there were 4,649 positive screens identified, of which 98.5% (n = 4,581) had a documented zip code. Therefore, 4,581 positive screens (among 3,459 PLWH) for unhealthy alcohol use and 2,370 positive screens (among 1,699 PLWH with documented AUD) were included in the primary and secondary analyses, respectively.

Sample characteristics are presented across rurality in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, marital status, and VA eligibility status. However, PLWH living in urban areas appeared to be more likely to be black, compared with those living in small and large rural areas. Conversely, PLWH living in small rural areas appeared to be more likely to be white, compared to those living in large rural and urban areas. Further, PLWH in urban areas appeared to be more likely to live in the Northeast and West than those in large or small rural areas, while PLWH in small rural areas appeared to be more likely than those in other areas to live in the Midwest. PLWH in large rural areas appeared to be more likely than those in small rural or urban areas to live in the South. Most mental health and substance use characteristics did not differ across rurality, although patients from urban areas appeared more likely to have been diagnosed with PTSD, stimulant use, and opioid use disorder while patients in small rural areas had a higher prevalence of tobacco use disorder compared to those in more urban areas. There were no differences across rurality in healthcare utilization among PLWH.

TABLE 1:

Descriptive Characteristics among PLWH with Unhealthy Alcohol Use at time of first AUDIT-C during the study period across Rurality

| Overall | Urban | Large Rural | Small Rural | P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=3459 | (%) | N=3113 | (%) | N=130 | % | N=216 | % | ||||

| Age | <50 | 1173 | (33.9) | 1057 | (34.0) | 38 | (29.2) | 78 | (36.1) | .721 | |

| 50–64 | 2039 | (58.9) | 1836 | (59.0) | 82 | (63.1) | 121 | (56.0) | |||

| 65+ | 247 | (7.1) | 220 | (7.1) | 10 | (7.7) | 17 | (7.9) | |||

| Gender | Male | 3389 | (98.0) | 3052 | (98.1) | 127 | (97.7) | 209 | (96.8) | .404 | |

| Female | 70 | (2.0) | 60 | (1.9) | 3 | (2.3) | 7 | (3.2) | |||

| VA Eligibility Status | Full VA Coverage | 574 | (16.6) | 516 | (16.5) | 20 | (15.4) | 38 | (17.6) | .510 | |

| Service connected <50% | 718 | (20.8) | 645 | (20.7) | 34 | (26.2) | 39 | (18.1) | |||

| Non-service connected | 2167 | (62.7) | 1952 | (62.7) | 76 | (58.5) | 139 | (64.4) | |||

| Marital Status | Divorced/Separated | 1127 | (33.0) | 1009 | (32.8) | 39 | (30.0) | 79 | (36.7) | .317 | |

| Never married/Single | 401 | (11.7) | 352 | (11.4) | 20 | (15.4) | 29 | (13.5) | |||

| Married | 1779 | (51.4) | 1616 | (51.9) | 65 | (50.0) | 98 | (45.4) | |||

| Widowed | 114 | (3.3) | 99 | (3.2) | 6 | (4.6) | 9 | (4.2) | |||

| Missing | 38 | (1.1) | 37 | (1.2) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (.5) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | Black | 1968 | (56.9) | 1814 | (58.3) | 72 | (55.4) | 83 | (38.4) | < .001 | |

| White | 1085 | (31.4) | 925 | (29.7) | 50 | (38.5) | 110 | (50.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 257 | (7.4) | 239 | (7.7) | 5 | (3.8) | 13 | (6.0) | |||

| Other | 148 | (4.3) | 135 | (4.3) | 3 | (2.3) | 10 | (4.6) | |||

| Region | Northeast | 526 | (15.2) | 495 | (15.9) | 11 | (8.5) | 20 | (9.3) | < .001 | |

| Midwest | 470 | (13.6) | 404 | (13.0) | 13 | (10.0) | 53 | (24.5) | |||

| Southeast | 1880 | (54.4) | 1681 | (54.0) | 92 | (70.8) | 108 | (50.0) | |||

| West | 582 | (16.8) | 533 | (17.1) | 14 | (10.8) | 35 | (16.2) | |||

| Fiscal Year of First AUDIT-C screen | 2010 | 1302 | (37.6) | 1162 | (37.3) | 50 | (38.5) | 90 | (41.7) | .195 | |

| 2011 | 961 | (27.8) | 862 | (27.7) | 33 | (25.4) | 66 | (30.6) | |||

| 2012 | 797 | (23.0) | 721 | (23.2) | 29 | (22.3) | 47 | (21.8) | |||

| 2013 | 399 | (11.5) | 368 | (11.8) | 18 | (13.8) | 13 | (6.0) | |||

| Depression | 545 | (15.8) | 498 | (16.0) | 18 | (13.8) | 29 | (13.4) | .501 | ||

| PTSD | 477 | (13.8) | 444 | (14.3) | 11 | (8.5) | 22 | (10.2) | .050 | ||

| Anxiety Disorder | 427 | (12.3) | 373 | (12.0) | 17 | (13.1) | 37 | (17.1) | .079 | ||

| SMI | 522 | (15.1) | 470 | (15.1) | 15 | (11.5) | 37 | (17.1) | .371 | ||

| Stimulant Use Disorder | 978 | (28.3) | 901 | (28.9) | 29 | (22.3) | 48 | (22.2) | .033 | ||

| Opioid Use Disorder | 289 | (8.4) | 277 | (8.9) | 3 | (2.3) | 9 | (4.2) | .002 | ||

| Other Drug Use Disorder | 481 | (13.9) | 442 | (14.2) | 16 | (12.3) | 23 | (10.6) | .305 | ||

| Tobacco Use Disorder | 1353 | (39.1) | 1201 | (38.6) | 48 | (36.9) | 104 | (48.2) | .018 | ||

| Current Tobacco Use | 2165 | (62.6) | 1947 | (62.5) | 82 | (63.1) | 136 | (63.0) | .985 | ||

| AUDIT-C Categories | 5–8 | 3299 | (72.0) | 2950 | (71.9) | 120 | (69.0) | 229 | (74.8) | .363 | |

| 9–12 | 1282 | (28.0) | 1151 | (28.1) | 54 | (31.0) | 77 | (25.2) | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 1699 | (49.1) | 1539 | (49.4) | 54 | (41.5) | 106 | (49.1) | .212 | ||

| Past-year alcohol specific condition | 83 | (2.4) | 77 | (2.5) | 1 | (.8) | 5 | (2.3) | .459 | ||

| Past-year alcohol related condition | 310 | (9.0) | 289 | (9.3) | 9 | (6.9) | 12 | (5.6) | .126 | ||

| Total Outpatient visits in prior year: mean (IQR) | 2.8 (2) | 2.8 (2) | 2.5 (1) | 2.6 (1) | |||||||

| Total Outpatient visits in prior year | 0 | 39 | (1.1) | 34 | (1.1) | 2 | (1.5) | 3 | (1.4) | .073 | |

| 1–4 | 428 | (12.4) | 371 | (11.9) | 21 | (16.2) | 36 | (16.7) | |||

| 5–10 | 847 | (24.5) | 749 | (24.1) | 41 | (31.5) | 57 | (26.4) | |||

| 11–24 | 1101 | (31.8) | 1002 | (32.2) | 32 | (24.6) | 67 | (31.0) | |||

| >=25 | 1044 | (30.2) | 957 | (30.7) | 34 | (26.2) | 53 | (24.5) | |||

| Total Inpatient visits in prior year: mean (IQR) | .4 (0) | 0.4 (0) | 0.3 (0) | 0.0 | (0) | ||||||

| Total inpatient visits in prior year | 0 | 2619 | (75.7) | 2353 | (75.6) | 96 | (73.8) | 170 | (78.7) | .936 | |

| 1 | 492 | (14.2) | 445 | (14.3) | 21 | (16.2) | 26 | (12.0) | |||

| 2–3 | 256 | (7.4) | 233 | (7.5) | 9 | (6.9) | 14 | (6.5) | |||

| >=4 | 92 | (2.7) | 82 | (2.6) | 4 | (3.1) | 6 | (2.8) | |||

Note: VA = Veterans Health Administration, AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, SMI = Serious Mental Illness, IQR = Interquartile range

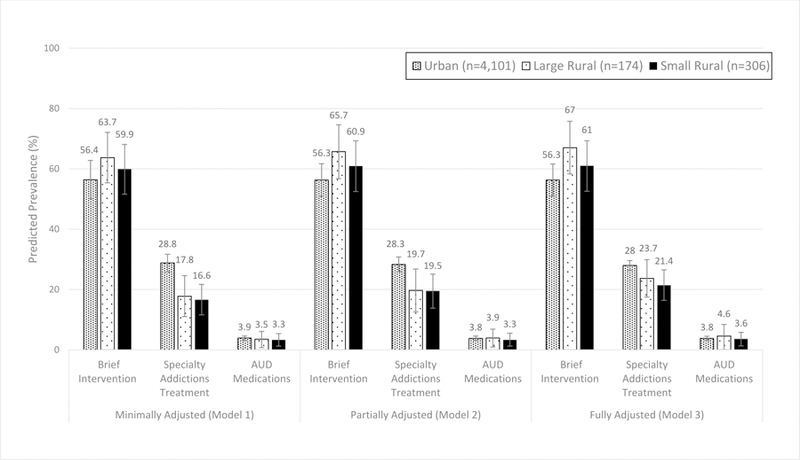

Results of models assessing differences in alcohol-related care across rurality among all positive screens are presented in Table 2 (relative risk) and Figure 1 (predicted prevalence estimates). Though no differences in receipt of brief intervention were observed across rurality in minimally adjusted models, differences were observed in both the partially adjusted model adjusted for demographic characteristics and the fully adjusted model (Table 2). Specifically, in the fully adjusted model, relative to PLWH living in urban areas, PLWH living in large rural areas were more likely receive brief interventions than those in urban areas (test for ordinal trend between PLWH in urban and large rural areas P = .014, and between PLWH in large and small rural areas P = .310). After full adjustment, there was a 10.8 [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.8, 19.7] percentage point difference in predicted prevalence estimates for receipt of brief intervention between PLWH in urban and large rural areas (Figure 1) with 56.3% [95% CI: (50.9, 61.6)] of PLWH living in urban areas, 67.0% (58.3, 75.8) of PLWH living in large rural areas, and 61.0% (52.6, 69.3) of PLWH living in small rural areas having documented brief intervention (P comparing predicted prevalence for PLWH living in urban versus large rural areas = .019).

TABLE 2:

Among VA Patients Living with HIV with Unhealthy Alcohol Use: Relative risk of receiving alcohol related care for those living in urban versus large or small rural areas (N = 4581), overall and among the subsample with documented alcohol use disorder (AUD) (N = 2370)

| Relative Risks (RR) Comparing Receipt of Alcohol-related Care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Rural Relative to Urban | Small Rural Relative to Urban | ||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | ||

|

Among those with Unhealthy Alcohol Use (N = 4581) | |||||

| Receipt of Brief Intervention | Model 1 | 1.13 | (.98, 1.30) | 1.06 | (.92, 1.22) |

| Model 2 | 1.17 | (1.02, 1.34) | 1.08 | (.95, 1.23) | |

| Model 3 (primary) | 1.19 | (1.04, 1.37) | 1.08 | (.95, 1.23) | |

| Receipt of Specialty Addictions Treatment | Model 1 | .62 | (.42, .91) | .58 | (.43, .78) |

| Model 2 | .70 | (.49, 1.00) | .69 | (.52, .92) | |

| Model 3 (primary) | .85 | (.65, 1.10) | .77 | (.61, .97) | |

| Receipt of AUD Medications | Model 1 | .90 | (.41, 1.95) | .85 | (.43, 1.69) |

| Model 2 | 1.01 | (.46, 2.22) | .87 | (.44, 1.74) | |

| Model 3 (primary) | 1.22 | (.54, 2.78) | .94 | (.48, 1.83) | |

|

Among subsample of those with documented AUD (N = 2370) | |||||

| Receipt of Specialty Addictions Treatment | Model 1 | .80 | (.55, 1.14) | .70 | (.55, .89) |

| Model 2 | .82 | (.58, 1.17) | .77 | (.60, .98) | |

| Model 3 (primary) | .94 | (.72, 1.24) | .84 | (.67, 1.05) | |

| Receipt of AUD Medications | Model 1 | 1.09 | (.45, 2.62) | .80 | (.40, 1.58) |

| Model 2 | 1.16 | (.48, 2.82) | .76 | (.38, 1.53) | |

| Model 3 (primary) | 1.24 | (.50, 3.07) | .79 | (.39, 1.58) | |

Model 1: Adjusted for fiscal year

Model 2: Adjusted for fiscal year of AUDIT-C screen, age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, VA eligibility status, and region

Model 3: Adjusted for fiscal year of AUDIT-C screen, age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, VA eligibility status, region, HIV disease severity, depression, other mood disorders, PTSD, anxiety, severe mental illness, stimulant use disorder, opioid use disorder, other drug use disorder, AUDIT-C category, alcohol use disorder, alcohol specific-conditions, healthcare utilization (inpatient and outpatient), and past-year tobacco use or use disorder.

CI = 95% Confidence Interval

RR = Relative Risk (Incidence rate ratio) obtained from Poisson regression model

Relative risk is bolded if P < .05

Figure 1.

Adjusted Predicted Prevalence and 95% Confidence Intervals for Receipt of Brief Intervention, Specialty Addictions Treatment, and Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) Medications among a National Sample of VA Patients Living with HIV with Unhealthy Alcohol Use Living in Urban, Large Rural, and Small Rural Areas (n=4,581)

There were also significant differences in receipt of specialty addictions treatment (Table 2). In all models, relative to urban PLWH, PLWH in small rural areas were less likely to receive specialty addictions treatment. However, there was no evidence of a trend across rurality (test for ordinal trend between urban and large rural areas in fully adjusted model P = .216 and between large and small rural areas P = .548). In the fully adjusted model, the absolute difference between urban and small rural areas was a 6.6 (95% CI: 1.5, 11.6) percentage points (Figure 1) with 28.0% (26.4, 29.6) of PLWH in urban areas, 23.7% (17.5, 29.9) of PLWH in large rural areas, and 21.4% (16.4, 26.5) of PLWH in small rural areas having received specialty addictions treatment (P comparing predicted prevalence for PLWH living in urban versus small rural areas = .011).

No significant differences in receipt of AUD medications among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use were identified in any of the models (Table 2), although overall receipt of AUD medications across all groups was very low (Figure 1). In the fully adjusted model, predicted prevalence of receipt of AUD was 3.8% (95% CI: 3.1, 4.5) for PLWH in urban areas, 4.6% (.8, 8.4) for those in large rural areas, and 3.6% (1.3, 5.8) for PLWH in small rural areas.

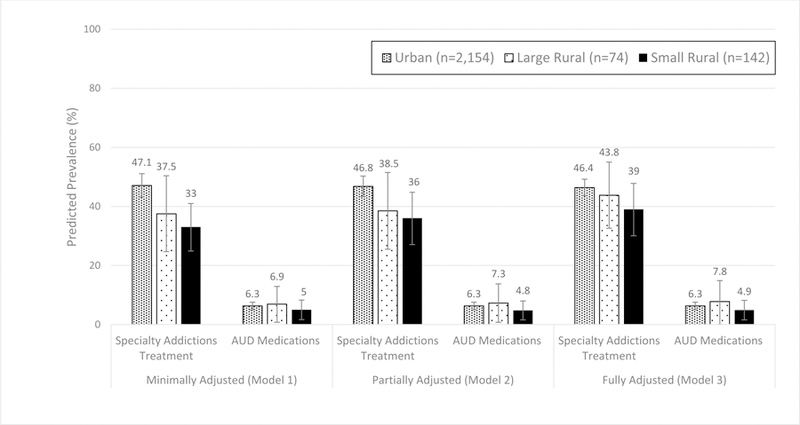

Results of the secondary analyses among those with AUD were generally similar to those among all PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use (Table 2). Those in small rural areas were less likely to receive specialty addictions treatment than those in urban areas in minimally adjusted model and model adjusted for demographics. After full adjustment, differences between PLWH with AUD in urban and small rural areas were attenuated and no longer significant. Additionally, there was no evidence of a trend across rurality in the fully adjusted model (test for ordinal trend between urban and large rural areas P = .670 and between large and small rural areas P = .486). Among the subsample with documented AUD, there was no significant difference in receipt of AUD medications among PLWH with AUD in any model. While rates were slightly higher within the subsample with documented AUD relative to all of those with unhealthy alcohol use, rates remained very low overall (Table 2; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted Predicted Prevalence and 95% Confidence Intervals for Receipt of Brief Intervention, Specialty Addictions Treatment, and Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) Medications among a National Sample of VA Patients Living with HIV with Unhealthy Alcohol Use and Documented AUD Living in Urban, Large Rural, and Small Rural Areas (n=2,370)

DISCUSSION:

In this national sample of PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use receiving care at the VA, we identified differences in receipt of evidence-based alcohol-related care across rural status. Findings suggest that receipt of brief intervention was more common among PLWH living in large rural areas than in urban areas, and highlight that PLWH in more rural areas, and particularly those in small rural areas, were potentially under-served regarding receipt of specialty addictions treatment. Consistent with research in non-HIV specific patient populations,36,50 AUD medications appeared to be substantially under-utilized among all PLWH across rurality. There were no differences in AUD medication use across rural status.

Because VA has a national performance measure for brief intervention,21 we would expect there to be little variation in the prevalence of these services across rurality. However, we found that PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use in large rural areas were more likely than those in urban areas to receive brief interventions. These findings may be reason for concern given that unhealthy alcohol use among PLWH is common51 and most PLWH live in urban areas.52 Thus, the absolute differences in raw number of PLWH may have population-level implications for PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use. It is possible that brief interventions may be more common in large rural areas because there is less access in rural areas to other types of treatment, such as specialty addictions treatment53 and AUD medications, the latter of which has been shown to be under-utilized in rural non-HIV specific clinical populations.50,54 Hence, clinics in rural areas may increase provision of brief interventions because it may be the option perceived to be most available.55,56 Continued work is needed to both ensure equitable receipt of brief interventions among PLWH regardless of area of residence, as well as work to improve the quality of brief intervention delivered in VA.

The present study also found that while under-receipt of brief intervention was more common among PLWH living in urban areas, PLWH living in small rural areas may be particularly vulnerable to under-receipt of specialty addictions treatment. These findings are similar to studies finding decreased access to care for rural patients with mental health disorders.57 Previous studies not specific to PLWH have demonstrated that people living in rural areas may have unique barriers to receipt of alcohol-related care,13 including decreased availability of services, decreased geographic proximity, increased stigma, and lack of access to technologies to support care.14,44,47,58,59 Studies have also demonstrated that patients living in rural areas receive less follow-up care after positive alcohol screening than patients living in urban areas.60 Additionally, a recent qualitative study found that while referral to specialty treatment is part of standard practice for patients with AUD among urban providers at the VA, rural providers viewed resources for AUD treatment to be unavailable and inadequate.56 It may be that PLWH in small rural areas receive less specialty addictions treatment because of these unique barriers to specialty care in rural areas. We note that some patients may have accessed care outside of VA, which would not have been measured in these data. However, this is unlikely to have impacted our results because disparities in rural areas have also been documented outside of the VA, showing lower access to non-VA specialty care.61

In combination with very low rates of AUD medication receipt, findings from this study are concerning regarding access to evidence-based treatment for AUD among the population of PLWH living in more rural areas. While specialty addictions treatment is available in VA, it may be difficult to access care in rural areas,56 and many patients prefer not to engage in specialty care.23,62 However, new technologies (eg, electronic or mobile app-based interventions) have potential to increase access to and utilization of specialty care. Telemedicine and other health system interventions may be important areas of study for increasing access to alcohol-related care among PLWH living in more rural areas. Most evidence-based behavioral treatments (eg, motivational enhancement therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy) can be offered through phone or tele-video conferencing and can provide access to alcohol-related care by removing geographic barriers and reducing the stigma and increasing anonymity of care.63,64

Non-technology based interventions to decrease travel-related barriers may also increase access to specialty addictions treatment and AUD medications. Travel reimbursements have been shown to increase healthcare utilization among patients living in rural areas.65 High adherence rates have also been observed when HIV medications have been mailed directly to patients,66 and a similar model may increase access to AUD medications for PLWH who live in very rural areas and have an alcohol use disorder. Rural VA providers also cite lack of local collaborations as a reason it is difficult to help patients access specialty care.56 Thus, increased partnerships with community-based non-VA care may help address under-receipt of specialty addictions treatment for PLWH living in rural areas. However, again, the availability of non-VA community-based specialty addictions treatment for AUD in rural areas in unclear.61 In addition, AUD medications have been shown to be as effective as specialty addictions treatment when prescribed along with ongoing medical management,67–69 and thus may be a viable option for provision in primary care settings.

However, there are notable barriers to provision of AUD medications to PLWH either in primary care55 or among HIV care providers.10 HIV providers report several barriers to prescribing AUD medications, including insufficient training and perceived lack of research on efficacy of AUD medications.10 Further, while barriers indicate a need for more training about the importance of offering alcohol-related care to PLWH and the efficacy of AUD medications, HIV providers report ambivalence about receiving training in treatment of substance use disorders.70 Primary care providers also report barriers to prescribing AUD medications, including a lack of time for training and a lack of support in managing AUD care.55 There also may be contraindications for use of some AUD medications among HIV patients (such as naltrexone among patients with hepatic problems).23 Thus, while it may be not be appropriate for all HIV patients, and there are substantial provider-level barriers need to be addressed to expand access to AUD medications, increased support for provision of AUD medications and ongoing medical monitoring may be an important mechanism for increasing receipt of evidence-based care among PLWH with AUD living in more rural areas.

There are several limitations to this study. Use of secondary clinical and administrative data may be associated with measurement error. Specifically, identification of eligible patients using clinically documented AUDIT-C screens may have resulted in under-identification of PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use due to methods of screening administration,71–73 social desirability bias, or limited patient recall.6 Measurement of brief interventions using text data generated via use of electronic clinical decision support may be limited for capturing brief intervention receipt,5,72 and data did not enable assessment of the quality of brief intervention delivered.6 However, electronic clinical decision support is commonly used in the VA to prompt and support documentation of care incentive by performance measures. The current measure derived from the electronic health record correlated well with patient report.21,33 Though not related to use of electronic data, our measure of AUD medications may also have been limited. Specifically, we included only FDA-approved medications (acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone) and one medication that had strong meta-analytic support during the study (topiramate).9 However, additional medications are now commonly used off-label to treat alcohol use disorders (eg, Gabapentin). Thus, rates of AUD medication receipt may have been under-estimates. In addition, we relied on VA eligibility to be an imperfect proxy of socioeconomic status. Because socioeconomic status is a known confounder in the association between rurality and both HIV alcohol-related outcomes,74 residual confounding by socioeconomic status, or other unmeasured confounders, may be present. The data were from 2009–2013, which may not reflect the most recent advancements in clinical practices or available services. Finally, results may not be generalizable to non-veterans, veterans not linked with care, veterans living with HIV with unhealthy alcohol use that would have been missed by the cut-point chosen for the study population,20,75 PLWH who receive care from both the VA and non-VA facilities, or all PLWH who are not VA patients.

Despite these limitations, this study has noteworthy strengths. It is the first to evaluate differences in receipt of alcohol-related care across rurality among PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use. Use of a large national sample of PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use builds on previous literature of rural differences in alcohol-related care, which has focused on experiences of PLWH in a specific region or on general outpatients (non-HIV specific).53,58,59,76 Our findings are consistent with other studies showing under-utilization of alcohol-related care among PLWH,10,12,77 and again highlight the need to increase receipt of alcohol-related care for all PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use, due to heightened risk of alcohol-related harms in this population.12,78–80 This study adds to current literature by highlighting that PLWH with unhealthy alcohol use who live in rural areas may be particularly vulnerable to under-receipt of specialty addictions treatment, although those in large rural areas may be more likely to receive brief interventions. Future research is needed to understand the reasons for these differences, whether differences exist among PLWH who use both VA and non-VA healthcare, and to promote solutions that increase receipt of alcohol-related care for all PLWH. Supporting physicians practicing in rural areas in provision of AUD medications, as well as increasing access to the services offered in specialty addictions treatment for interested patients in the most rural areas using innovative methods may be important to increase access to recommended AUD treatment.

Acknowledgements:

Funding Sources: Data for this research was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21AA022866-01). This study was supported in kind by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This study was additionally funded by a 2017 Small Grant from the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington (PI: Kara Bensley), and by a 2017 Pre-doctoral Fellowship from VA Puget Sound Research & Development awarded to Dr. Bensley. Dr. Bensley is also supported by Award Number T32AA007240, Graduate Research Training in Alcohol Problems: Alcohol-related Disparities, from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Dr. Williams is funded through a VA Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award (CDA 12-276).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have all approved the manuscript and declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation and presentation, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Views presented in the manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the University of Washington, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, Roberts MS, et al. Estimating the impact of alcohol consumption on survival for HIV+ individuals. AIDS Care 2007;19(4):459–466. doi: 10.1080/09540120601095734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Res Health J Natl Inst Alcohol Abuse Alcohol 2010;33(3):280–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2010;7(4):226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, et al. Measuring Performance of Brief Alcohol Counseling in Medical Settings: A Review of the Options and Lessons from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System. Subst Abuse 2007;28(4):133–149. doi: 10.1300/J465v28n04_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Shortreed SM, et al. Comparison of provider-documented and patient-reported brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in VA outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;153:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams EC, Rubinsky AD, Chavez LJ, et al. An early evaluation of implementation of brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in the US Veterans Health Administration: Early evaluation of VA’s brief intervention. Addiction 2014;109(9):1472–1481. doi: 10.1111/add.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Estimating the effect of help-seeking on achieving recovery from alcohol dependence. Addiction 2006;101(6):824–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01433.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisner C, Matzger H, Kaskutas LA. How important is treatment? One-year outcomes of treated and untreated alcohol-dependent individuals. Addict Abingdon Engl 2003;98(7):901–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Adults With Alcohol Use Disorders in Outpatient Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311(18):1889. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chander G, Monroe AK, Crane HM, et al. HIV primary care providers—Screening, knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to alcohol interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend January 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, Rabeneck L, Justice AC. How Harmful Is Hazardous Alcohol Use and Abuse in HIV Infection: Do Health Care Providers Know Who Is at Risk?: JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;33(4):521–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams EC, Lapham GT, Shortreed SM, et al. Among patients with unhealthy alcohol use, those with HIV are less likely than those without to receive evidence-based alcohol-related care: A national VA study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;174:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth BM, Kirchner J, Fortney J, Ross R, Rost K. Rural at-risk drinkers: correlates and one-year use of alcoholism treatment services. J Stud Alcohol 2000;61(2):267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortney J, Mukherjee S, Curran G, Fortney S, Han X, Booth BM. Factors associated with perceived stigma for alcohol use and treatment among at-risk drinkers. J Behav Health Serv Res 2004;31(4):418–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young J, Bensley K, Hawkins E, Achtmeyer C, Williams E. Barriers to Provision of Specialty Care for Alcohol Use Disorders: Perceptions and Treatment Practice of Primary Care Providers across Rural and Urban Settings. J Rural Health 2017;In Press.

- 16.Hartley D Rural Health Disparities, Population Health, and Rural Culture. Am J Public Health 2004;94(10):1675–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohl M, Tate J, Duggal M, et al. Rural residence is associated with delayed care entry and increased mortality among veterans with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Med Care 2010;48(12):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef60c2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohl ME, Perencevich E. Frequency of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in urban vs. rural areas of the United States: Results from a nationally-representative sample. BMC Public Health 2011;11(1):681. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelman EJ, Williams EC, Marshall BDL. Addressing unhealthy alcohol use among people living with HIV: recent advances and research directions. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bush K The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(16):1789. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased Documented Brief Alcohol Interventions With a Performance Measure and Electronic Decision Support: Med Care 2012;50(2):179–187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Bobb JF, et al. Changes in alcohol use associated with changes in HIV disease severity over time: A national longitudinal study in the Veterans Aging Cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;189:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.VA/DoD Clinical Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders Washington, D.C.: The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group; 2015. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams EC, Bradley KA. Alcohol-Related Care and Outcomes for Outpatients with HIV in a National VA Cohort Group Health Research Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrill R, Cromartie J, Hart G. METROPOLITAN, URBAN, AND RURAL COMMUTING AREAS: TOWARD A BETTER DEPICTION OF THE UNITED STATES SETTLEMENT SYSTEM. Urban Geogr 1999;20(8):727–748. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.20.8.727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a Brief Screen for Alcohol Misuse in Primary Care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(7):1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(6):781–787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0594-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams EC, Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Chavez LJ, Berger D, Bradley KA. Influence of a targeted performance measure for brief intervention on gender differences in receipt of brief intervention among patients with unhealthy alcohol use in the Veterans Health Administration. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;81:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, et al. Development and Verification of a “Virtual” Cohort Using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care 2006;44(8):S25–S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cromartie J, Hart G. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes Center for Rural Health; http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx#.U20K1F50H0A. Published June 2, 2014. Accessed October 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams EC, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, et al. Variation in Documented Care for Unhealthy Alcohol Consumption Across Race/Ethnicity in the Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2012;36(9):1614–1622. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berger D, Lapham GT, Shortreed SM, et al. Increased Rates of Documented Alcohol Counseling in Primary Care: More Counseling or Just More Documentation? J Gen Intern Med 2018;33(3):268–274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4163-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensley KM, Harris AHS, Gupta S, et al. Racial/ethnic Differences in Initiation of and Engagement with Addictions Treatment among Patients with Alcohol Use Disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. J Subst Abuse Treat August 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris AHS, Reeder RN, Ellerbe L, Bowe T. Are VHA administrative location codes valid indicators of specialty substance use disorder treatment? J Rehabil Res Dev 2010;47(8):699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams EC, Gupta S, Rubinsky AD, et al. Variation in receipt of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorders across racial/ethnic groups: A national study in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. Drug Alcohol Depend July 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bensley KM, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the association between alcohol use and mortality among men living with HIV. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2018;13(1). doi: 10.1186/s13722-017-0103-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matson TE, Mcginnis KA, Rubinsky AD, et al. Gender and alcohol use: influences on HIV care continuum in a national cohort of patients with HIV. AIDS July 2018:1. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Office of Budget and Management. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity Office of Budget and Management; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams EC, Gupta S, Rubinsky AD, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence of Clinically Recognized Alcohol Use Disorders Among Patients from the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016;40(2):359–366. doi: 10.1111/acer.12950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGinnis KA, Brandt CA, Skanderson M, et al. Validating Smoking Data From the Veteran’s Affairs Health Factors Dataset, an Electronic Data Source. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.StataCorp. Stata 13 Base Reference Manual: Margins College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2013. https://www.stata.com/manuals13/rmargins.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams R Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J 2012;12(2):308. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arcury TA, Gesler WM, Preisser JS, Sherman J, Spencer J, Perin J. The Effects of Geography and Spatial Behavior on Health Care Utilization among the Residents of a Rural Region. Health Serv Res 2005;40(1):135–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00346.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willging CE, Salvador M, Kano M. Brief Reports: Unequal Treatment: Mental Health Care for Sexual and Gender Minority Groups in a Rural State. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57(6):867–870. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.6.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slifkin R, Goldsmith L, Ricketts T. Race and Place:Urban-Rural Differences in Health for Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2000;(66). http://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/rural/pubs/finding_brief/fb61.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, Powers JM. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc 2005;21(1):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Fillenbaum G, Horner R. Health services access and use among older adults in North Carolina: urban vs rural residents. Am J Public Health 1995;85(10):1384–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou G A Modified Poisson Regression Approach to Prospective Studies with Binary Data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris AHS, Kivlahan DR, Bowe T, Humphreys KN. Pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 2010;61(4):392–398. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams EC, Joo YS, Lipira L, Glass JE. Psychosocial stressors and alcohol use, severity, and treatment receipt across human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status in a nationally representative sample of US residents. Subst Abuse December 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1268238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. HIV Surveillance in Urban and Nonurban Areas through 2016 Centers for Disease Control; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-urban-nonurban-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pullen E, Oser C. Barriers to Substance Abuse Treatment in Rural and Urban Communities: Counselor Perspectives. Subst Use Misuse 2014;49(7):891–901. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.891615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mark TL, Kassed CA, Vandivort-Warren R, Levit KR, Kranzler HR. Alcohol and opioid dependence medications: Prescription trends, overall and by physician specialty. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;99(1–3):345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of Alcohol Use Disorder Pharmacotherapy in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study in Five VA Clinics. J Gen Intern Med October 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4202-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young JP, Achtmeyer CE, Bensley KM, Hawkins EJ, Williams EC. Differences in Perceptions of and Practices Regarding Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorders Among VA Primary Care Providers in Urban and Rural Clinics: Urban Rural Differences in Treatment of AUD. J Rural Health January 2018. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mott JM, Grubbs KM, Sansgiry S, Fortney JC, Cully JA. Psychotherapy Utilization Among Rural and Urban Veterans From 2007 to 2010: Psychotherapy Use Among Rural Veterans. J Rural Health 2015;31(3):235–243. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Browne T, Priester MA, Clone S, Iachini A, DeHart D, Hock R. Barriers and Facilitators to Substance Use Treatment in the Rural South: A Qualitative Study: Substance Use Treatment Barriers and Facilitators. J Rural Health 2016;32(1):92–101. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fortney J, Booth BM. Access to Substance Abuse Services in Rural Areas. In: Alcoholism Boston, MA: Springer US; 2002:177–197. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-0-306-47193-3_10. Accessed April 17, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan Y-F, Lu S-E, Howe B, Tieben H, Hoeft T, Unützer J. Screening and Follow-Up Monitoring for Substance Use in Primary Care: An Exploration of Rural–Urban Variations. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31(2):215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3488-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohl ME, Carrell M, Thurman A, et al. “Availability of healthcare providers for rural veterans eligible for purchased care under the veterans choice act.” BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1). doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3108-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glass JE, Perron BE, Ilgen MA, Chermack ST, Ratliff S, Zivin K. Prevalence and correlates of specialty substance use disorder treatment for Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System patients with high alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;112(1–2):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baca CT, Alverson DC, Manuel JK, Blackwell GL. Telecounseling in Rural Areas for Alcohol Problems. Alcohol Treat Q 2007;25(4):31–45. doi: 10.1300/J020v25n04_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Staton-Tindall M, Wahler E, Webster JM, Godlaski T, Freeman R, Leukefeld C. Telemedicine-based alcohol services for rural offenders. Psychol Serv 2012;9(3):298–309. doi: 10.1037/a0026772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nelson RE, Hicken B, West A, Rupper R. The Effect of Increased Travel Reimbursement Rates on Health Care Utilization in the VA: Effect of Increased Travel Reimbursement Rates on Health Care Utilization. J Rural Health 2012;28(2):192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gross R, Zhang Y, Grossberg R. Medication refill logistics and refill adherence in HIV. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14(11):789–793. doi: 10.1002/pds.1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spithoff S, Kahan M. Primary care management of alcohol use disorder and at-risk drinking: Part 2: counsel, prescribe, connect. Can Fam Physician 2015;61(6):515–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined Pharmacotherapies and Behavioral Interventions for Alcohol Dependence: The COMBINE Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2006;295(17):2003. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller PM, Book SW, Stewart SH. Medical Treatment of Alcohol Dependence: A Systematic Review. Int J Psychiatry Med 2011;42(3):227–266. doi: 10.2190/PM.42.3.b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montague BT, Kahler CW, Colby SM, et al. Attitudes and Training Needs of New England HIV Care and Addiction Treatment Providers: Opportunities for Better Integration of HIV and Alcohol Treatment Services. Addict Disord Their Treat 2015;14(1):16–28. doi: 10.1097/ADT.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Thomas RM, et al. Factors Underlying Quality Problems with Alcohol Screening Prompted by a Clinical Reminder in Primary Care: A Multi-site Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(8):1125–1132. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(3). doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McGinnis KA, Tate JP, Williams EC, et al. Comparison of AUDIT-C collected via electronic medical record and self-administered research survey in HIV infected and uninfected patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol 2013;68(4):197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two Brief Alcohol-Screening Tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Validation in a Female Veterans Affairs Patient Population. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(7):821. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams EC, McFarland LV, Nelson KM. Alcohol consumption among urban, suburban, and rural Veterans Affairs outpatients. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc 2012;28(2):202–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chokron Garneau H, Venegas A, Rawson R, Ray LA, Glasner S. Barriers to initiation of extended release naltrexone among HIV-infected adults with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat May 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol Use and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection: Current Knowledge, Implications, and Future Directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res September 2016. doi: 10.1111/acer.13204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, et al. Risk of mortality and physiologic injury evident with lower alcohol exposure among HIV infected compared with uninfected men. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;161:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.The Veterans Aging Cohort Study, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, et al. Number of Drinks to ?Feel a Buzz? by HIV Status and Viral Load in Men. AIDS Behav 2016;20(3):504–511. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1053-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]