Abstract

Background:

Benzodiazepine misuse is a growing public health problem, with increases in benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths and emergency room visits in recent years. However, relatively little attention has been paid to this emergent problem. We systematically reviewed epidemiological studies on benzodiazepine misuse to identify key findings, limitations, and future directions for research.

Methods:

PubMed and PsychINFO databases were searched through February 2019 for peer-reviewed publications on benzodiazepine misuse (e.g., use without a prescription; at a higher frequency or dose than prescribed). Eligibility criteria included human studies that focused on the prevalence, trends, correlates, motives, patterns, sources, and consequences of benzodiazepine misuse.

Results:

The search identified 1,970 publications, and 351 articles were eligible for data extraction and inclusion. In 2017, benzodiazepines and other tranquilizers were the third most commonly used illicit or prescription drug in the U.S. (approximately 2.2% of the population). Worldwide rates of misuse appear to be similar to those reported in the U.S. Factors associated with misuse include other substance use, receipt of a benzodiazepine prescription, and psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Benzodiazepine misuse encompasses heterogeneous presentations of motives, patterns, and sources. Moreover, misuse is associated with myriad poor outcomes, including mortality, HIV/HCV risk behaviors, poor self-reported quality of life, criminality, and continued substance use during treatment.

Conclusions:

Benzodiazepine misuse is a worldwide public health concern that is associated with a number of concerning consequences. Findings from the present review have implications for identifying subgroups who could benefit from prevention and treatment efforts, critical points for intervention, and treatment targets.

Keywords: Benzodiazepines, Sedatives, Tranquilizers, Prescription Drug Misuse, Nonmedical Prescription Drug Use

1. Introduction

Benzodiazepines are a class of prescription medication that bind to the GABAA receptor, resulting in anxiolytic (anti-anxiety), hypnotic (sleep-inducing), anticonvulsant, and muscle-relaxing effects (see Table 1 for a list of commonly prescribed benzodiazepines). They are among the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medications (Moore and Mattison, 2017), with more than 1 in 20 people in the U.S. filling a prescription each year (Bachhuber et al., 2016). They are also the third most commonly misused illicit or prescription substance among adults and adolescents in the U.S. (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality [CBHSQ], 2018b; Johnston et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Common Types of Benzodiazepines

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Onset of Effect | Dose Equivalents (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| alprazolam | Xanax | fast/intermediate | 0.5 |

| chlordiazepoxide | Librium | intermediate | 25 |

| clonazepam | Klonopin | intermediate | 0.5 |

| clorazepate | Tranxene | intermediate | 15 |

| diazepam | Valium | fast | 10 |

| estazolam | ProSom | slow | 2 |

| flunitrazepam | Rohypnol | fast | 1 |

| flurazepam | Dalmane | fast | 20 |

| lorazepam | Ativan | fast | 1 |

| midazolam | Versed | fast | 15 (IV) |

| oxazepam | Serax | slow | 20 |

| quazepam | Doral | slow | 20 |

| temazepam | Restoril | intermediate | 20 |

| triazolam | Halcion | fast | 0.5 |

Note: Dose equivalents are estimates. Onset definitions: slow = 15–30 minutes, intermediate = 30–60 minutes, slow = 60–120 minutes. Sources: (Ashton, 2005; Bisaga and Mariani, 2015)

Several trends indicate a growing public health problem related to benzodiazepines. Most notably, benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths increased by more than 400% from 1996–2013 (Bachhuber et al., 2016) and emergency department visits for benzodiazepines increased by more than 300% from 2004 to 2011 (Jones and McAninch, 2015). These increases have occurred concurrently with rising rates of benzodiazepine prescribing. The number of benzodiazepine prescriptions not only increased 67% from the mid-1990s to 2013, but the quantity (i.e., dose equivalents) increased more than 3-fold over this time period (Bachhuber et al., 2016). The proportion of people with an opioid analgesic prescription who were also prescribed a benzodiazepine increased 41% from 2002 to 2014 (Hwang et al., 2016), despite evidence that concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions increase risk of overdose (Sun et al., 2017). Indeed, the use and misuse of benzodiazepines has contributed substantially to the current opioid overdose epidemic, with benzodiazepines involved in nearly 30% of opioid overdose deaths in 2015 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018). New concerns continue to emerge, such as the increasing availability of highly lethal benzodiazepines on the illicit market (e.g., illicitly produced pills that combine benzodiazepines with fentanyl and potent “designer” benzodiazepines) (Hoiseth et al., 2016; Huppertz et al., 2018).

Despite the worsening public health indicators associated with benzodiazepine use, this issue remains overlooked by policymakers and the scientific community (Lembke et al., 2018). This may be partly attributable to the low perceived risk associated with benzodiazepines (Assanangkornchai et al., 2010; Quintero, 2012). In the U.S., benzodiazepines are classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance, which indicates relatively low risk for misuse, consistent with its regulation in most Western countries, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Although benzodiazepines were initially believed to have minimal risk for misuse, evidence indicates that benzodiazepines have misuse potential, particularly in certain vulnerable subgroups, such as people with a history of substance use disorders (SUDs) (Griffiths and Weerts, 1997; Licata and Rowlett, 2008).

A better understanding of benzodiazepine misuse is needed to inform research on its prevention and treatment, and to mitigate the growing harms of this problem. The aim of this manuscript is to: (1) provide a comprehensive review and synthesis of the literature on the epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse, and (2) to identify key next steps in the study of benzodiazepine misuse.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Scope of the Review

We searched the PubMed and PsycINFO databases through February 2019 to identify peer-reviewed publications on the epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse. Peer-reviewed publications were included if they examined issues relevant to the epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse, including: Prevalence, trends, correlates, sources, patterns, motives, and consequences. International research was included in the present review; however, prevalence estimates primarily reflect data collected in the U.S. due to the limited availability of epidemiological data outside of the U.S. Accordingly, recent government publications using data from population-based surveys (e.g., National Survey on Drug Use and Health [NSDUH], Monitoring the Future [MTF]) and treatment settings (e.g., Treatment Episode Data Set [TEDS]) in the U.S. were included in the present review.

All methods were carried out in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2015). See Supplementary Materials for additional details on methods, including search terms, inclusion criteria, and data extraction methods.

2.2. Definitions

The field has not reached a consensus about how to define the problematic use of prescription medications (e.g., use without a prescription, use in ways other than prescribed, use to get high, etc.), or the appropriate term to characterize problematic prescription medication use (e.g., nonmedical prescription drug use, prescription drug misuse, prescription drug abuse). In this review, we use the term misuse to broadly encompass any use of a prescription medication without a prescription, at a higher frequency or dose than prescribed, or for the feelings of the drug rather than its medical indication. The terms sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic abuse, dependence, or use disorder (referred to as SHA abuse, dependence, or use disorder throughout the manuscript) refer to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD; World Health Organization, 1992) diagnoses.

Many studies reviewed utilize surveys combining benzodiazepines with other sedatives, tranquilizers, anxiolytics, and hypnotics. See Table 2 for characteristics of U.S. general population surveys included in the present review, including specific medications included in broader prescription drug categories, such as sedatives and tranquilizers. We will use the terms sedatives and tranquilizers when reporting prevalence data extracted from these general population surveys. Elsewhere, to balance accuracy with ease of interpretation, we use the term “benzodiazepines” to refer both to studies of benzodiazepines exclusively and in combination with other sedatives/tranquilizers.

Table 2.

Characteristics of U.S. Nationally-Representative Surveys Utilized in the Present Review

| Survey | Years Administe red |

Overview of Sample | Definition of Misuse/Nonmedi cal Use | Tranquili zers Specified |

Sedatives Specified |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitori ng the Future (MTF) | 12th graders: 1975- present (annually) 8th & 10th graders: 1991- present (annually) |

|

“Use on your own—that is, without a doctor telling you to take them.” | Librium, Valium, Xanax |

Prior to 2004 (barbiturat es): barbiturates, downs/dow ners, goofballs, yellows, reds, blues, rainbows 2004 to present (sedatives/ barbiturate s): barbiturates, downs/dow ners, phenobarbit al, Ambien, Lunesta, Sonata, Tuinal, Nembutal, Seconal |

|

| National Comorbi dity Survey (NCS) |

Baseline interview: 1990–1992 |

|

“Use on your own; that is, either: One, without a doctor’s prescription, or Two, in greater amounts than prescribed, or Three, more often than prescribed, or Four, for any reasons other than a doctor said you should take them--such as for kicks, to get high, to feel good, or curiosity about the pill’s effect.” | Librium, Valium, Ativan, Meproba mate, “Nerve Pills” |

Barbiturates , Sleeping Pills, Seconal, “Downers” | |

| National Epidemi ologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditio ns (NESA RC) |

Wave 1: 2000–2001 Wave 2 (follow-up survey of Wave 1 respondent s): 20042005 |

|

“Use without a doctor’s prescription; in greater amounts, more often, or longer than prescribed; or for a reason other than a doctor said you should use them.” | Librium, Muscle relaxants, Valium, Xanax |

Barbiturates , Chloral Hydrate, Quaaludes, Seconal, Sleeping pills |

|

| National Epidemi ologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditio ns-III (NESA RC-III) |

2012–2013 |

|

“Use without a doctor’s prescription; in greater amounts, more often, or longer than prescribed; or for a reason other than a doctor said you should use them.” |

NESARC-III assessed sedatives and tranquilizers in combination: Alprazolam, Alurate, Amobarbital, Amytal, Aprobarbital, Aqualude, Atarax, Ativan, Barbital, Barbiturates, Benzodiazepines, Bromides, Butalbital, Butisol, Buticaps (Butisol Caps), Carbrital, Carbromal, Carisoprodol, Centrax, Chloral Hydrate, Chlordiazepoxide, Chlordiaz/clid, Chlordiazep, Cibas, Clonazepam, Clorazepate, Dalmane, Deprol, Desbutal, Diazepam, Dilantin, Doriden, Durrax, Equanil, Eskabarb, Estazolam, Ethchlorvynol, Flurazepam, Glutethimide, Halcion, Hydroxyzine, Lenetran, Libritabs, Librium, Lorazepam, Ludes, Luminal, Mebaral, Melzone, Meprobamate, Meprospan, Methaqualone, Methyprylon, Miltown, Mysoline, Nembutal, Nitrazepam, Noctec, Noludar, Octinox, Oxazepam, Paraldehyde, Parest, Paxipam, Pentobarbital, Pentothal, Phenergan, Phenobarbital, Placidyl, Prazepam, Primidone, Promethazine, Quaalude, Restoril, Secobarbital, Seconal, Seldane, Serax, SK- Lygen, Soma, Sopor, Taractan, Temazepam, Transpoise, Tranxene, Trepidome, Triazolam, Tuinal, Valium, Valmid, Vanadom, Veronal, Vistaril, Xanax |

||

| National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDU H) |

1971- present (annually) |

|

Prior to 2015: “Your use of a drug if the drug was not prescribed for you, or if you took the drug only for the experience or feeling it caused.” 2015-present: “Use in any way not directed by a doctor, including use without a prescription of one’s own; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than told to take a drug; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor.” |

Alprazola m, Ativan, Buspirone, Clonazepa m, Cyclobenz aprine (also known as Flexeril), Diazepam, Hydroxyzi ne, Klonopin, Lorazepa m, Meprobam ate, Soma, Valium, Xanax |

Ambien, Butisol, Zolpidem, Flurazepa m (also known as Dalmane), Halcion, Lunesta or eszopiclon e, Phenobarbi tal, Restoril, Sonata or zaleplon, Seconal, Temazepa m, Triazolam |

|

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

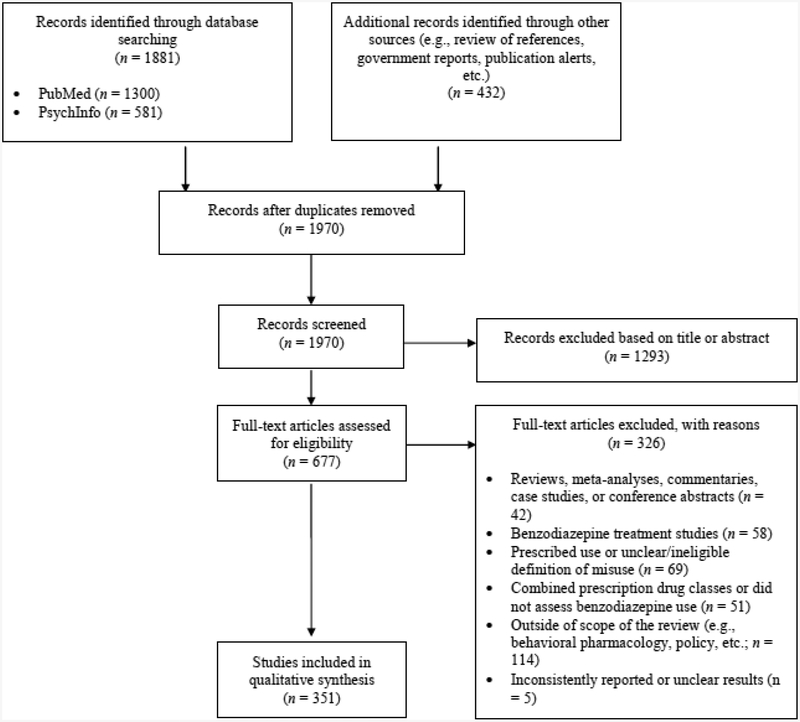

Results of the search are presented in Figure 1. Our search strategy yielded 1,970 unique records, of which 351 were included in the present review. Of the 677 full-text manuscripts that were assessed for eligibility, 326 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion include the following: topic outside of the scope of the review (n=114); focus on use as prescribed or unclear/ineligible definition of misuse (n=69); treatment outcome study (n=58); combined prescription drug classes or did not assess benzodiazepine misuse (n=51); review, meta-analysis, commentary, case study, or conference abstract (n=42); and inconsistently reported or unclear results (n=5). Of the studies included in the present review, 14 were published prior to 1990 (the oldest study being published in 1975), 57 were published between 1990–1999, 95 were published between 2000–2009, and 185 were published between 2010–2018. Data from 179 studies were collected in the U.S., 77 from Western Europe, 35 from Australia, 23 from Canada, 17 from East Asia, 9 from Israel, 6 from other regions (e.g., Brazil, India, Nepal, and Poland), and 5 studies did not specify location.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of records identified, screened, and included.

Note: Records could be excluded for multiple reasons.

3.2. Prevalence and Trends

3.2.1. U.S. Statistics.

Data from the 2017 NSDUH indicate that approximately 6 million U.S. citizens ages 12 and older (approximately 2.2% of the population) misused tranquilizers in the previous year, making tranquilizers the third most commonly misused illicit substance following marijuana (15%) and prescription opioids (4.1%). Prevalence rates for past-year tranquilizer misuse were nearly identical to those reported for cocaine use. Additionally, approximately 1.4 million people (0.5%) misused sedatives in the previous year.

Although tranquilizers are among the most commonly misused drug types, tranquilizer use disorder was only the fifth most common illicit drug use disorder. An estimated 739,000 people met criteria for a tranquilizer use disorder (0.3% of U.S. population). Notably, this estimate is slightly higher than the estimate for heroin use disorder. Approximately 198,000 individuals met criteria for a sedative use disorder (0.1%), making sedative use disorder the second least common SUD (the least common being inhalant use disorder). This discrepancy between a relatively high prevalence of misuse but low prevalence of use disorders is consistent with an analysis of National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) data indicating that few individuals with sedative/tranquilizer misuse meet criteria for a sedative/tranquilizer use disorder at a 3-year follow-up, with most discontinuing misuse over that time (Boyd et al., 2018). Among individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), conditional dependence, or the percentage of people with misuse who meet criteria for dependence, for benzodiazepines is lower than for other substances (Wu et al., 2012).

Despite increases in benzodiazepine prescribing over the past decade (Bachhuber et al., 2016), prevalence estimates for sedative/tranquilizer misuse and use disorder have remained relatively stable among both adolescents and adults in the U.S. (CBHSQ, 2015a, 2018b; Johnston et al., 2018; Palamar et al., 2019), including among those with opioid misuse (Boggis et al., 2019) (see Supplementary Materials for data on trends prior to the previous decade). Yet, overdose deaths and emergency room visits involving benzodiazepines have increased (Cai et al., 2010; Day, 2013; Jones and McAninch, 2015). SUD treatment admissions for benzodiazepines as a primary substance more than doubled from 2005 to 2011, but have decreased somewhat through 2015 (8,163 in 2004, 18,855 in 2011, 14,000 in 2015; CBHSQ, 2017). This pattern may reflect increasing polysubstance use, with benzodiazepines being combined with other substances. Indeed, 82.1% of all SUD treatment admissions related to benzodiazepines are for benzodiazepines as a secondary substance of use (CBHSQ, 2011), and treatment admissions involving both benzodiazepines and opioid analgesics increased 570% from 2000 to 2010 (CBHSQ, 2012).

3.2.2. International Statistics.

As previously noted, limited population-based data on the prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse is available for countries outside of the U.S. Available data from countries outside of the U.S. suggest that rates of misuse are similar to those reported in the U.S. For example, a 2008–2009 general population survey of over 20,000 individuals ages 15 to 64 in Sweden found that 2.2% of participants misused benzodiazepines and other sedatives in the previous year (Abrahamsson and Hakansson, 2015). The same rate of current benzodiazepine misuse was found in a 2008–2009 household survey of 2,280 individuals ages 15 and older residing in the Ubon Ratchathani Province region of Thailand (Puangkot et al., 2010). Yet, a nationwide survey of 26,633 general population respondents across Thailand (ages 12–65) found a slightly lower prevalence of misuse, with approximately 1% reporting the misuse of anxiolytic and hypnotics in the previous year (Assanangkornchai et al., 2010). Similar rates of past-year misuse (approximately 1–2%) have been reported in general population samples in Brazil (Galduróz et al., 2005) and Australia (Hall et al., 1999). Although few studies outside of the U.S. have examined trends in misuse, a nationwide study of 179,114 school-age respondents (14 to 18 years old) in Spain found that the prevalence of tranquilizer, sedative, and sleeping pill misuse increased from 2.4% in 2004 to 3.0% in 2014 (Carrasco-Garrido et al., 2018).

Worldwide rates of SHA use disorder are also similar to those reported in the U.S. In the same study referenced above conducted in the Ubon Ratchathani Province region of Thailand, 0.6% of respondents met criteria for DSM-IV benzodiazepine abuse and 0.2% of respondents met criteria for dependence (Puangkot et al., 2010). An older survey of 10,641 adult respondents in Australia conducted in 1997 found that 0.4% of respondents met criteria for benzodiazepine and other sedative dependence (Hall et al., 1999). Although international rates of benzodiazepine misuse and SHA use disorder are similar to those reported in U.S. general population surveys, there is significant variability in methods across these surveys (e.g., definitions of misuse, categorization of prescription drug classes). Consistent definitions of benzodiazepine misuse are needed to determine cross-national differences in the prevalence of misuse, as well as the impact of benzodiazepine availability and regulations on misuse.

3.3. Correlates and Risk Factors for Benzodiazepine Misuse

An overview of findings on sociodemographic correlates of benzodiazepine misuse is presented in Table 3. The findings on substance use and psychiatric correlates of benzodiazepine misuse presented below have been replicated in numerous samples; details and further citations in support of these findings are included in Supplementary Materials.

Table 3.

Findings on Sociodemographic Correlates of Benzodiazepine Misuse

| Population | Finding | References |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. | Younger age (e.g., < 25) was associated with benzodiazepine misuse | (Arterberry et al., 2016; Blanco et al., 2018; Fenton et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2018; Goodwin and Hasin, 2002; Huang et al., 2006; Maust et al., 2018; McCabe et al., 2006a) |

| General population samples outside of the U.S. | Older age was associated with benzodiazepine misuse | (Assanangkornchai et al., 2010; Schneider et al., 2015) |

| Adolescents/young adults in the U.S. | ||

| No association between age and benzodiazepine misuse | (Boyd et al., 2015) | |

| Adults with opioid misuse/SUDs/injection drug use | ||

| No association between age and benzodiazepine misuse | (Apantaku-Olajide et al., 2012; Bleich et al., 1999; Bleich et al., 2002; de Wet et al., 2004; Dobbin et al., 2003; Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2010; Lavie et al., 2009; Malcolm et al., 1993; McHugh et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2017; Moses et al., 2018; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013; Stein et al., 2017b) | |

| Gender | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. | ||

| No association between gender and benzodiazepine misuse | (Blanco et al., 2013; Ford et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2006) | |

| General population samples outside of the U.S. | ||

| No association between gender and benzodiazepine misuse | (Hall et al., 1999) | |

| Adolescents/young adults in the U.S. | ||

| No association between gender and benzodiazepine misuse | (Boyd et al., 2015; Boyd et al., 2006; Ford, 2008b, 2009; McCabe et al., 2007a; McCabe et al., 2017a; Pickover et al., 2016; Shadick et al., 2016) | |

| Adolescents/young adults outside of the U.S. | Women were at greater risk of benzodiazepine misuse | (Carrasco-Garrido et al., 2018; Currie and Wild, 2012; Kokkevi et al., 2008) |

| Adults with opioid misuse/SUDs/injection drug use | ||

| No association between gender and benzodiazepine misuse | (Bawor et al., 2015; Bleich et al., 1999; Boggis et al., in press; Darke et al., 1994a; Davies et al., 1996; Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2010; Ghitza et al., 2008; Hearon et al., 2011; Ickowicz et al., 2015; McHugh et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2017; Moitra et al., 2013; Mulvaney et al., 1999; Ng et al., 2007; Peles and Adelson, 2006; Peles et al., 2009; Perera et al., 1987; Schiff et al., 2007; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013; Shand et al., 2011) | |

| Race/Ethnicity1 | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. | ||

| No association between race/ethnicity and benzodiazepine misuse | (Maust et al., 2018) | |

| Adolescents/young adults in the U.S. | ||

| “Other” racial/ethnic identity was associated with benzodiazepine misuse, as compared to Black and Hispanic identities | (McCabe et al., 2017b) | |

| Adolescents/young adults outside of the U.S. | Aboriginal racial/ethnic identity was associated with benzodiazepine misuse, as compared to non-Aboriginal identities | (Currie and Wild, 2012) |

| Adults with opioid misuse/SUDs/injection drug use | ||

| No association between race/ethnicity and benzodiazepine misuse | (Bleich et al., 2002; Ickowicz et al., 2015; Moitra et al., 2013) | |

| Other subgroups (e.g., men who have sex with men, adults with HIV, adults in the club drug scene) | ||

| No association between race/ethnicity and benzodiazepine misuse | (Kelly et al., 2015a) | |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. | Sexual minority groups were more likely to misuse benzodiazepines, as compared to those with heterosexual identities | (Cochran et al., 2004) |

| Adolescents/young adults in the U.S. | Sexual minority groups were more likely to misuse benzodiazepines, as compared to those with heterosexual identities | (Dagirmanjian et al., 2017; McCabe, 2005; Shadick et al., 2016) |

| Adolescents/young adults outside of the U.S. | Sexual minority groups were more likely to misuse benzodiazepines, as compared to those with heterosexual identities | (Li et al., 2018) |

| Other subgroups (e.g., men who have sex with men, adults in the club drug scene) | ||

| Gay sexual identity was associated with lower risk of benzodiazepine misuse, as compared to hetero- or bi-sexual identities | (Kecojevic et al., 2015c) | |

| Other Sociodemographic Factors | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. (adults and young adults/adolescents) | Lower levels of education, lower income, unemployment, and being unmarried were associated with benzodiazepine misuse | (Arterberry et al., 2016; Becker et al., 2007; Blanco et al., 2018; Goodwin and Hasin, 2002; Huang et al., 2006; McCabe et al., 2018; Schepis et al., 2018a) |

| Adults with opioid misuse/SUDs/injection drug use | ||

| No association between homelessness, marital status, employment status, level of education, income, and benzodiazepine misuse | (Bouvier et al., 2018; Brands et al., 2008; Fry and Bruno, 2002; Ghitza et al., 2008; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017; McHugh et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2017; Rooney et al., 1999; Williams et al., 1996) | |

Note: References included in the table do not represent an exhaustive list of studies examining sociodemographic correlates of benzodiazepine misuse. Instead, this table provides an overview of the main findings.

The vast majority of studies examining racial/ethnic identity as a correlate of benzodiazepine misuse have been conducted in the U.S., and therefore racial/ethnic minority status refers to U.S. demographics.

3.3.1. Age.

Benzodiazepine misuse is most common in young adults. According to data from the 2015–2016 NSDUH, the highest past-year rates of combined sedative/tranquilizer misuse were observed among 18 to 25-year-olds (5.8%), followed by 26 to 34-year-olds (4%) (Schepis et al., 2018b). In the U.S., the typical age of onset of benzodiazepine misuse is during early adulthood (i.e., 18–25 years) (Boyd et al., 2018; McCabe et al., 2007b), and the average age of onset for SHA use disorder is the early-to-late 20s (Conrod et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2006). In this section, we provide a brief overview of benzodiazepine misuse across the developmental spectrum.

Estimates of benzodiazepine misuse are highly variable between general population samples in the U.S. and student-based samples, making it difficult to ascertain the impact of benzodiazepine misuse in this age group. According to 2016 NSDUH data, <2% of adolescents ages 12 to 17 reported past-year combined sedative/tranquilizer misuse and 2.3% reported lifetime misuse (Schepis et al., 2018b). However, estimates from the MTF survey are more than twice as high, and indicate that more than 5.5% of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders reported lifetime tranquilizer misuse in 2017 (Johnston et al., 2018). These prevalence rates are comparable to those reported among a sample of approximately 85,000 secondary school students in European countries (Kokkevi et al., 2008). Similarly, in a national sample of 10,904 college students in the U.S., 7.8% reported lifetime benzodiazepine misuse, 4.5% reported past-year misuse, and 1.6% reported past-month misuse (McCabe, 2005).

High rates of benzodiazepine misuse among adolescents and young adults are particularly concerning given that younger age of benzodiazepine misuse onset is associated with greater risk for and more rapid development of SHA disorder (Chen et al., 2009; McCabe et al., 2007b). The transition to college may be a particularly risky time; a study of college sophomores found a 102.9% increase in the prevalence of misuse from pre-college – one of the greatest rates of increase among all substances during this time period (Arria et al., 2008).

Little is known about benzodiazepine misuse in older adults, despite high rates of prescribing in this group (Maust et al., 2018; Schepis et al., 2018b). Rates of tranquilizer and sedative misuse are lower in adults over the age of 50, as compared to younger age groups (Maust et al., 2018; Schepis et al., 2018b), and are lower than rates of prescription opioid misuse in this age group (Blazer and Wu, 2009). Yet, the prevalence of lifetime and past-year tranquilizer misuse increased among this age group from 2002–2003 to 2012–2013 (from 4.5% to 6.6% and 0.6% and 0.9%, respectively; Schepis and McCabe, 2016). In addition, the proportion of individuals with past-year tranquilizer misuse who are over the age of 50 doubled from 2005–2006 to 2013–2014 (from 7.9% to 16.5%; Palamar et al., 2019). Benzodiazepine misuse and dependence appears to be more common among older adults with a prescription or who are treated in psychiatric settings (Landreat et al., 2010; Voyer et al., 2009; Yen et al., 2015).

3.3.2. Gender.

In 2017, women and men over the age of 12 in the U.S. reported similar rates of tranquilizer misuse (2.1% vs. 2.3%, respectively) (CBHSQ, 2018b). Indeed, studies among adults and adolescents in the U.S. have not demonstrated consistent gender differences in the prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse (Table 3). In contrast, research in countries outside of the U.S. has generally demonstrated a greater likelihood of benzodiazepine misuse and SHA use disorder amongst female adolescents and adults (Table 3).

Analyses of gender differences in benzodiazepine prevalence from the same datasets (e.g., NSDUH) have, at times, yielded different results, suggesting that gender differences are likely modest and may be impacted substantially by factors such as sample size, covariates, and methodological variations across studies. For example, several studies controlling for history of a benzodiazepine prescription have identified higher misuse rates (Fenton et al., 2010; Maust et al., 2018) and higher likelihood of developing a use disorder among men (Lev-Ran et al., 2013). This is consistent with data from approximate 85,000 high school students across Europe, in which gender moderated the association between having a prescription and misuse, such that exposure via prescription increased the likelihood of misuse more in boys than girls (Kokkevi et al., 2008). Furthermore, a recent analysis of NSDUH data found that males between the ages of 18–49 had lower odds of benzodiazepine misuse than females, whereas there was no association between gender and benzodiazepine misuse at younger (12–17 years) and older age ranges (50 years and older) (Schepis et al., 2018b). These findings illustrate that gender differences in misuse might vary according to prescription status and age. Nevertheless, the comparable prevalence between men and women in the U.S. and higher rates of misuse among women outside of the U.S. is in contrast to many other substances (e.g., heroin, marijuana), for which prevalence is generally higher in men (CBHSQ, 2018b).

3.3.3. Race/Ethnicity.

Nearly all studies examining the associations between race/ethnicity and benzodiazepine misuse indicate that misuse is more common among people who identify their race/ethnicity as Non-Hispanic White (Table 3). Nonetheless, in the 2017 NSDUH, rates of misuse for those with multiple racial/ethnic identities were nearly identical to those reported by Non-Hispanic Whites for both tranquilizers and sedatives (2.6% and 0.5%, respectively, for those with multiple racial/ethnic identities vs. 2.6% and 0.6% for Non-Hispanic Whites) (CBHSQ, 2018b). Furthermore, the proportion of individuals with past-year tranquilizer misuse who reported a racial/ethnic minority identity increased from 2005–2006 to 2013–2014 (Palamar et al., 2019).

Many studies on this topic combine heterogeneous racial/ethnic minority groups (e.g., Non-Hispanic Asian, Native American, multiple racial ethnic identities) into one “other” racial/ethnic category, which is a significant limitation of this literature. In addition, few studies control for access to benzodiazepines via legitimate prescription, despite findings that people identifying as Non-Hispanic White are more likely to be prescribed benzodiazepines (Cook et al., 2018; Olfson et al., 2015). In one U.S. general population study of individuals who had ever received an anxiety medication prescription, odds of lifetime benzodiazepine misuse were higher for Non-Hispanic White adults, as compared to Black adults (Fenton et al., 2010). Looking at this question in a different way, a recent general population study comparing people who reported only using benzodiazepine as prescribed to people who reported misuse did not find an effect of racial/ethnic identity (Maust et al., 2018).

3.3.4. Other Sociodemographic Correlates.

Large-scale studies across several subgroups indicate that sexual minority groups are more likely to misuse benzodiazepines (Table 3). However, this has not been replicated in some smaller studies among specific populations (e.g., young adults using club drugs). Studies examining other sociodemographic correlates of benzodiazepine misuse (e.g., employment status, housing status, etc.) are less consistent and appear to diverge between general population studies and samples of people with SUDs (Table 3). In population-based studies, lower levels of education, lower income, unemployment, and being unmarried are generally associated with benzodiazepine misuse. Yet, findings in samples of people with SUDs are equivocal.

3.3.5. Substance Use.

People with SUDs, particularly OUD, have much higher rates of benzodiazepine misuse than the general population. Analyses of 2008–2014 NSDUH data found that adults with OUD had a rate of combined sedative/tranquilizer misuse that was approximately 20 times greater than the U.S. general population, with 43% reporting past-year sedative/tranquilizer misuse (Votaw et al., 2019). Benzodiazepine misuse is often even more prevalent among people in treatment for OUD; past-month estimates range from 7–73%, with a majority (67%) of studies reviewed reporting rates greater than 40% (Apantaku-Olajide et al., 2012; Bleich et al., 2002; Darke et al., 1993, 1994b; Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2010; Franklyn et al., 2017; Gelkopf et al., 1999; Ghitza et al., 2008; Gilchrist et al., 2006; Lavie et al., 2009; McHugh et al., 2017; Metzger et al., 1991; Millson et al., 2006; Moitra et al., 2013; Naji et al., 2016; Peles et al., 2009, 2010; Stein et al., 2017b; Stein et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2010).

The prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse has been understudied among individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD), despite evidence that alcohol use and AUD increase risk of benzodiazepine misuse (Becker et al., 2007; Goodwin and Hasin, 2002; Huang et al., 2006; McCabe et al., 2006a), and that alcohol contributes to benzodiazepine-related overdoses (Jones et al., 2014). An analysis of 2008–2014 NSDUH data found that approximately 7.6% of those with AUD, including those with DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence, reported past-year sedative/tranquilizer misuse, a rate 3–4 times greater than among the U.S. general population (Votaw et al., 2019). Rates of misuse might be higher among those with greater AUD severity, as evidenced by an analysis of NSDUH data wherein approximately 12% of those with DSM-IV alcohol dependence reported past-year sedative/tranquilizer misuse (Hedden et al., 2010). Indeed, studies of people with AUD in treatment demonstrate even higher rates, with estimates of recent benzodiazepine misuse (self-reported past-month use or urine drug screen results) ranging from 19–40% (McHugh et al., 2018; Morel et al., 2016; Ogborne and Kapur, 1987; Ross, 1993).

Benzodiazepine misuse is also common (i.e., >50% over study periods ranging from the past month to participants’ lifetimes) among those with illicit drug use (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines) and/or prescription drug misuse (Darke et al., 1994a; Havens et al., 2010; Kecojevic et al., 2015c; Kelly and Parsons, 2007; Kurtz et al., 2011; Lankenau et al., 2007; Lankenau et al., 2012b; Roy et al., 2018) and those in SUD treatment settings (Beary et al., 1987; Murphy et al., 2014; Pattanayak et al., 2010; Wolf et al., 1989). This is consistent with data that other substance use is consistently associated with benzodiazepine misuse in numerous populations, and that benzodiazepine misuse is associated with greater substance use severity cross-sectionally and prospectively (see Supplementary Materials). In fact, benzodiazepine misuse increases with the overall level of polysubstance use (McHugh et al., 2018; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013; Votaw et al., 2019). Benzodiazepine misuse is strongly associated with risk for other prescription drug misuse and use disorders, particularly prescription opioid misuse and OUD (Blanco et al., 2018; Boggis et al., 2019; Han et al., 2017; Han et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2006; Jones and McCance-Katz, 2019; Jones, 2017; Maust et al., 2018). This co-occurrence is so common that a factor analysis indicated that prescription drug use disorders reflect a single latent factor (Blanco et al., 2013).

3.3.6. Psychiatric Comorbidity and Affective Vulnerabilities.

Greater psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric disorders, particularly anxiety and mood disorders, are associated with both benzodiazepine misuse and SHA use disorder in large epidemiological studies among adults (Abrahamsson and Hakansson, 2015; Goodwin and Hasin, 2002; Huang et al., 2006; Martins and Gorelick, 2011; Rigg and Ford, 2014) and adolescents (Boyd et al., 2015; Schepis and Krishnan-Sarin, 2008; Zullig and Divin, 2012). This finding has been replicated across heterogeneous populations (see Supplementary Materials). The few studies that have examined personality disorders have also demonstrated a strong association with benzodiazepine misuse (see Supplementary Materials)9.

There are few longitudinal studies addressing this topic; thus, causality and temporality remain largely unknown. In a study across the two waves of the NESARC, lifetime history of benzodiazepine misuse was associated with risk for onset of psychiatric disorders three years later (Schepis and Hakes, 2011), with evidence that higher frequency of misuse was associated with increased risk of incident mood or anxiety disorders (Schepis and Hakes, 2013). Earlier age of onset of major depressive disorder has been associated with higher likelihood of a SHA use disorder (Schepis and McCabe, 2012).

Although not consistently studied, several studies examining gender as a moderator of the association between symptoms of anxiety and/or depression and benzodiazepine misuse have found a stronger association among women than men (Hearon et al., 2011; McHugh et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2017; Zullig and Divin, 2012). Analysis of a large general population sample in the U.S. found that the association between anxiety disorders and SHA use disorder was stronger among women relative to men; however, the association between panic disorder without agoraphobia and sedative dependence was higher among men (Conway et al., 2006). Findings that gender moderates the association between psychiatric disorders/vulnerabilities and benzodiazepine misuse are consistent with data suggesting that women are more likely than men to misuse benzodiazepines to cope with negative affect (Boyd et al., 2015; Kokkevi et al., 2008; McCabe et al., 2009; McCabe and Cranford, 2012; McLarnon et al., 2014; Terry-McElrath et al., 2009).

3.3.7. Receipt of a Benzodiazepine Prescription.

One of the most consistent correlates of benzodiazepine misuse is the receipt of a benzodiazepine prescription. Population-based data in the U.S. indicate that those with any prescription anxiety medication have 1.9 times greater odds of past-year benzodiazepine misuse and 2.6 times greater odds of SHA use disorder (Fenton et al., 2010), a finding that has been replicated in numerous populations (see Supplementary Materials)). There is some evidence that people diagnosed with a condition for which benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed (e.g., anxiety, insomnia) are more sensitive to the reinforcing effects of benzodiazepines (Helmus et al., 2005). Nonetheless, previous studies indicate that benzodiazepine prescriptions are independently associated with greater odds of misuse, even after controlling for psychiatric disorders and anxiety/depression symptoms (Boyd et al., 2015; Fenton et al., 2010). Earlier age of prescription initiation (Austic et al., 2015; McLarnon et al., 2011), longer duration of prescription use (Boyd et al., 2015), and greater frequency of prescription use (McCabe et al., 2011a) are associated with greater odds of benzodiazepine misuse.

Misuse of one’s own prescription might occur without knowledge that such behavior comprises misuse, as evidenced by findings that using a greater dose than prescribed for therapeutic purposes is the most common form of misuse (as opposed to taking a greater dose to get high or to modify other drug effects) among those with benzodiazepine prescriptions (Ladewig and Grossenbacher, 1988; McCabe et al., 2011a; McLarnon et al., 2011). There are also studies suggesting that some individuals, particularly those with illicit drug use, intentionally seek out benzodiazepine prescriptions for the purpose of misusing (Ibanez et al., 2013; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017; Ross et al., 1996).

3.4. The How and Why of Benzodiazepine Misuse: Sources, Patterns, and Motives

Many findings reported below have been replicated in numerous populations; further support for these findings is included in Supplementary Materials).

3.4.1. Sources.

Benzodiazepines that are misused are obtained from a variety of sources, such as diversion from friends and family members with a prescription, prescriptions from a doctor (or multiple doctors), and purchase through an illicit source (CBHSQ, 2018b). Receiving diverted medications from friends and family members is the most common source of benzodiazepines (CBHSQ, 2018b; Inciardi et al., 2010; McCabe and Boyd, 2005; McCabe and West, 2014); 64.4% of NSDUH respondents with past-year tranquilizer misuse most recently received tranquilizers from friends or family members. Over 80% of these participants reported that their friend or family member had obtained the medication via a prescription from a doctor (CBHSQ, 2018b). Although limited, data indicate that over 20% of adolescents and adults with a benzodiazepine prescription have diverted their medications (Boyd et al., 2007; McCabe et al., 2011b; McLarnon et al., 2011).

Misuse of one’s own benzodiazepine prescription is common across heterogenous populations, including both substance-using and general population samples of adults and adolescents (see Supplementary Materials). Notably, individuals misusing their own prescription are more likely to report frequent misuse and greater benzodiazepine use severity, as compared to those who receive benzodiazepines from friends or family (Ford and Lacerenza, 2011; McCabe et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2016). Adults with more severe substance use presentations also commonly report obtaining benzodiazepines from illicit sources, such as drug dealers (Ruben and Morrison, 1992; Stein et al., 2016), multiple doctors (Allgulander et al., 1984; Ruben and Morrison, 1992), and a combination of illicit and licit sources (Liebrenz et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2013; Ross et al., 1996; Ruben and Morrison, 1992). A recent analysis of young adult NSDUH respondents found that obtaining benzodiazepines from multiple sources is associated with greater risk of SUDs (McCabe et al., 2018).

3.4.2. Benzodiazepine Formulations.

Certain benzodiazepine formulations are more commonly misused than others, and availability (vis-à-vis prescribing rates) robustly affects the misuse of different benzodiazepine products. Among the U.S. general population, 73% of those with past-year benzodiazepine misuse reported misuse of alprazolam products (Hughes et al., 2016), a finding that has been replicated in numerous subgroups in the U.S. (see Supplementary Materials)12. This is consistent with data indicating that alprazolam is the most commonly prescribed benzodiazepine in the U.S. (Lindsley, 2012). In the reviewed studies, participants also reported misusing clonazepam, diazepam, and lorazepam (also among the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medications in the U.S.; Moore and Mattison, 2017). Commonly misused benzodiazepine products appear to vary internationally, likely reflecting variability in prescribing rates for certain benzodiazepines. For example, misuse of oxazepam (Fleischhacker et al., 1986; Frauger et al., 2011; Kan et al., 2001; Morel et al., 2016) and lormetazepam (Lugoboni et al., 2014; Quaglio et al., 2012) has been reported in European samples, but is not common in U.S.-based samples.

Although prevalence estimates for misuse of specific benzodiazepine formulations appear to coincide with prescribing rates, certain benzodiazepines are more preferred than others, potentially reflecting higher abuse liability. In several substance-using samples, participants reported preferring diazepam and flunitrazepam (as indicated by ratings of drug liking, high, and preferred drug), as compared to other benzodiazepine products (Barnas et al., 1992; Iguchi et al., 1993; Malcolm et al., 1993; Stitzer et al., 1981). However, these studies were published over two decades ago, and therefore preference might—at least in part—reflect availability during this period. Route of administration might also determine one’s preference, given that temazepam (particularly the gel-filled capsule formulation) and flunitrazepam appear to be the most commonly injected benzodiazepines (Forsyth et al., 1993; Fountain et al., 1999; Fry and Miller, 2001; Fry et al., 2007; Fry and Bruno, 2002; Lavelle et al., 1991; Oyefeso et al., 1996; Strang et al., 1994; Sunjic and Howard, 1996; Williams et al., 1996). Recent studies from East Asia also report midazolam injection (Hayashi et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2010; Ti et al., 2014; Van Griensven et al., 2005).

3.4.3. Frequency of Misuse.

For NSDUH respondents who misused tranquilizers in the past month, the average frequency of misuse was 5 days, with over 50% of respondents reporting 1–2 days of misuse (CBHSQ, 2018b). However, the frequency of benzodiazepine misuse varies widely with study sample and time frame assessed. Most college students with past-year benzodiazepine misuse report misuse on fewer than five occasions in the previous year (Messina et al., 2016; Pickover et al., 2016). Among those with OUD and/or injection drug use who misused benzodiazepines in the previous month, 27–60% report daily benzodiazepine misuse (Darke et al., 1993; Fatseas et al., 2009; Gilchrist et al., 2006), with misuse occurring on an average of 13 days (Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2016).

3.4.4. Route of Administration.

Oral route of administration, or swallowing a pill, is by far the most common route of administration (Brandt et al., 2014a; McLarnon et al., 2014; Pauly et al., 2012). Intranasal benzodiazepine misuse is the second most common route of administration, with approximately 10% of college students (Brandt et al., 2014a) and 45% of young adults with recent prescription drug misuse (Lankenau et al., 2012a) reporting lifetime intranasal use. Smoking and injecting benzodiazepines are both relatively uncommon and have primarily been documented in samples with SUDs or severe patterns of substance use (e.g., injection heroin use). Even in these populations, the prevalence of smoking benzodiazepines is low (i.e., 3–7%) (Lankenau et al., 2012a; Navaratnam and Foong, 1990; Vogel et al., 2013).

The prevalence of benzodiazepine injection varies widely, from <2–37% over periods ranging from past-month to past-year (Bennett and Higgins, 1999; Darke et al., 2002; Darke et al., 1995; Davies et al., 1996; Dobbin et al., 2003; Fry and Bruno, 2002; Gelkopf et al., 1999; Horyniak et al., 2012; Ickowicz et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2013; Nielsen et al., 2007; Van Griensven et al., 2005). The studies in which injection use is common (>20%) have typically included samples of injection opioid users (Ross and Darke, 2000) or have specifically recruited benzodiazepine injectors (Strang et al., 1994) or injection drug users (Hayashi et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2010; Smyth et al., 2001) (see Supplementary Materials for additional information on benzodiazepine injection in these populations). Benzodiazepine injection is associated with greater substance use severity (Hayashi et al., 2013; Kerr et al., 2010; Smyth et al., 2001; Van Griensven et al., 2005), accidental overdose (Bennett and Higgins, 1999; Darke et al., 2002), scarring/bruising/abscesses around injection sites (Breen et al., 2004; Darke et al., 2002; Hayashi et al., 2013), vascular disease (Hayashi et al., 2013), and increased risk of infectious disease (Zhang et al., 2015).

3.4.5. Co-Ingestion.

Benzodiazepines are often co-ingested, or used simultaneously, with other substances in a range of heterogenous samples (see Supplementary Materials)13. Qualitative and descriptive results indicate that coingesting benzodiazepines with alcohol increases the intoxicating effects of both substances (Calhoun et al., 1996; Dåderman and Lidberg, 1999; Perera et al., 1987). Mixing benzodiazepines with opioids (Dwyer, 2008; Gelkopf et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2013; Lankenau et al., 2012a; Navaratnam and Foong, 1990; Ng et al., 2007; Ross et al., 1996; Ruben and Morrison, 1992; Vogel et al., 2013) and opioid agonist medication (i.e., methadone, buprenorphine) (Gelkopf et al., 1999; Nielsen et al., 2007; Stitzer et al., 1981; Vogel et al., 2013) to enhance the effects of opioids (Dwyer, 2008; Hayashi et al., 2013; Lankenau et al., 2007; Lankenau et al., 2012b; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017; Motta-Ochoa et al., 2017; Navaratnam and Foong, 1990; Ng et al., 2007; Ruben and Morrison, 1992) is widespread among those with opioid use and/or injection drug use. Interestingly, one study among individuals in OUD treatment found that nearly 90% of participants who mixed benzodiazepines with other drugs did so to “improve emotional states” (Gelkopf et al., 1999).

Beyond increasing the effects of opioids and alcohol, benzodiazepines are combined with stimulants (e.g., amphetamines, cocaine) and ecstasy to “come down from” or decrease the effects of these substances (e.g., anxiety, irritation, insomnia) (Calhoun et al., 1996; Fountain et al., 1999; Gelkopf et al., 1999; Kelly et al., 2015b; Lankenau et al., 2012a; Motta-Ochoa et al., 2017; Rigg and Ibanez, 2010). Benzodiazepines are also commonly co-ingested with marijuana (Brandt et al., 2014a; Calhoun et al., 1996; McLarnon et al., 2011; Schepis et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2013), sometimes by smoking both substances (Calhoun et al., 1996; Kelly et al., 2015b; Lankenau et al., 2007), but little is known about motives for this combination. The widespread use of benzodiazepines is particularly concerning given that co-ingesting benzodiazepines with other substances, particularly opioids and alcohol, is associated with increased risk of overdose (Jones et al., 2012).

3.4.6. Motives.

Common motives for benzodiazepine misuse and correlates of motives are reviewed below. It is important to note that currently available quantitative measures of motives for benzodiazepine misuse focus on a limited range of motives and the factor structure for these measures is unclear (Messina et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2013). Nonetheless, several qualitative studies provide a broader picture of the motives for benzodiazepine misuse.

Much like other prescription drugs (e.g., opioids, stimulants) (McHugh et al., 2015), benzodiazepines are most commonly misused for reasons aligned with the drug’s indication (e.g., sleep, anxiety). Over 75% of NSDUH respondents with past-year tranquilizer misuse reported that they misused prescription tranquilizers to help with conditions for which benzodiazepines are indicated, such as sleep, tension, or emotions (CBHSQ, 2018b). The finding that self-treatment or coping motives are the most common reasons for benzodiazepine misuse has been replicated across heterogenous samples (see Supplementary Materials). However, benzodiazepines are also misused out of curiosity (Chen et al., 2011; Kapil et al., 2014; Kokkevi et al., 2008; Liebrenz et al., 2015) and for recreational motives, such as to get high (Boyd et al., 2006; Brandt et al., 2014b; Calhoun et al., 1996; Johnston and O’Malley, 1986; Kecojevic et al., 2015a; Kelly et al., 2015b; McCabe et al., 2009; McLarnon et al., 2014; Nattala et al., 2011; Nattala et al., 2012; Quintero et al., 2006; Rigg and Ibanez, 2010; Silva et al., 2013a; Terry-McElrath et al., 2009) and to modify the effects of other substances (Section 3.4.5.). Notably, those who report recreational motives also display more problematic use, such as combining benzodiazepines with other substances, reporting greater substance use severity, taking higher doses, taking benzodiazepines by non-oral routes of administration, and illicitly purchasing benzodiazepines (Fatseas et al., 2009; McCabe et al., 2009; McCabe and Cranford, 2012; McLarnon et al., 2014; Schepis et al., 2016; Stein et al., 2016).

Many individuals with benzodiazepine misuse report multiple motives for misuse (McCabe et al., 2009). Misusing benzodiazepines for multiple reasons is particularly common among those with opioid use and/or injection drug use (Fatseas et al., 2009; Vogel et al., 2013), which is consistent with findings that reporting multiple motives is associated with greater substance use severity (e.g., greater benzodiazepine use frequency [McCabe et al., 2009; Nattala et al., 2011]; co-ingesting benzodiazepines and alcohol [Nattala et al., 2012]). Among those with opioid use and/or injection drug use, benzodiazepines are commonly misused to enhance the effects of opioids or opioid agonist medications (see Section 3.4.5.). Studies in these populations have also found that benzodiazepines are misused to decrease opioid withdrawal symptoms (Gelkopf et al., 1999; Hayashi et al., 2013; Lankenau et al., 2007; Lankenau et al., 2012b; Motta-Ochoa et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2013; Perera et al., 1987; Ross et al., 1996; Ruben and Morrison, 1992; Stein et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2013) and to substitute for opioids, either as a strategy to help decrease opioid use (Lankenau et al., 2012b; Mateu-Gelabert et al., 2017; Perera et al., 1987) or during times of decreased opioid availability (Fry et al., 2007; Lankenau et al., 2012b; Ruben and Morrison, 1992).

3.5. Functional Consequences Associated with Benzodiazepine Misuse.

A number of studies have examined the association between benzodiazepine misuse and an array of clinical and functional consequences (e.g., suicide, physical health, etc.). In many of these studies, it is difficult to ascertain whether the association is attributable to a benzodiazepine-specific effect or more generally to a worse substance use profile (e.g., more polysubstance use). Consistent with this weakness, several findings have not been consistently replicated, likely due to significant variability in methods across studies. Throughout this section, we provide potential explanations for the association between benzodiazepine misuse and functional consequences. Yet, results should be interpreted with caution. An overview of findings on consequences associated with benzodiazepine misuse is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Findings on Functional Consequences Associated with Benzodiazepine Misuse

| Population | Finding | References |

|---|---|---|

| Overdose | ||

| Individuals with opioid use, prescription drug misuse, or injection drug use | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with overdose in unadjusted but not adjusted analyses | (Calvo et al., 2017; Jenkins et al., 2011; Mcgregor et al., 1998; Ochoa et al., 2005) | |

| Suicidal Behaviors | ||

| Individuals with opioid use, prescription drug misuse, or injection drug use | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was not associated with suicidal ideation or attempt, or associations were only significant in unadjusted but not adjusted analyses | (Backmund et al., 2011; Maloney et al., 2009; Wines et al., 2004) | |

| Individuals with alcohol dependence | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with suicidal ideation or attempt | (Preuss et al., 2003) |

| General population samples in the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with suicidal ideation or attempt | (Blanco et al., 2018; Borges et al., 2000; Schepis et al., 2019; Schepis et al., 2018b) |

| Adolescent samples outside of the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with suicidal ideation or attempt | (Guo et al., 2016; Juan et al., 2015; Kokkevi et al., 2012) |

| Infectious Disease and Associated Behaviors | ||

| Individuals with opioid use, prescription drug misuse, or injection drug use | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was not associated with HCV infection or sexual risk behaviors | (Havens et al., 2013; Kecojevic et al., 2015b) | |

| College students in the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with regretted sexual experiences and sexual victimization | (Parks et al., 2017; Young et al., 2011) |

| Criminality | ||

| Individuals with opioid use, prescription drug misuse, or injection drug use | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was not associated with criminality | (Darke et al., 2002; Hall et al., 1993) | |

| Adolescents in the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with criminal involvement | (Ford, 2008a) |

| Treatment Outcomes (Substance Use) | ||

| Individuals receiving SUD treatment (most commonly for OUD) | ||

| No association between baseline benzodiazepine misuse and substance use during and after treatment | (Darke et al., 2010; Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2010) | |

| Treatment Outcomes (Retention) | ||

| Individuals receiving SUD treatment (most commonly for OUD) | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was not associated with treatment retention | (Davstad et al., 2007; Kellogg et al., 2006; Proctor et al., 2015; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013; Specka et al., 2011) | |

| Quality of Life and Physical Health | ||

| General population samples in the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with poorer self-reported physical health and disability | (Ford et al., 2018; Schepis et al., 2018b) |

| General population samples outside of the U.S. | Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with poorer self-reported quality of life | (Abrahamsson et al., 2015) |

| Individuals with opioid use, illicit/prescription drug misuse, or injection drug use | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with greater sleep dysfunction | (Blanco et al., 2013; Manconi et al., 2017; Mazza et al., 2014; Peles et al., 2009) | |

| Other subgroups (e.g., healthcare workers, adolescents in the emergency department) | ||

| Benzodiazepine misuse was associated with more emergency department visits | (Whiteside et al., 2013) | |

3.5.1. Overdose.

Benzodiazepines increase the risk of heart rate and respiratory depression when co-ingested with opioids and/or alcohol, increasing the risk for overdose (Jones et al., 2012). In three prospective studies of individuals with SUDs (primarily OUD) and/or injection drug use, benzodiazepine misuse was associated with greater odds of mortality (Pavarin, 2015), particularly related to overdose deaths (Gossop et al., 2002; Riley et al., 2016). Likewise, benzodiazepine misuse and dependence have been associated with non-fatal overdose in retrospective studies (Table 4). Benzodiazepines are also involved in methadoneand buprenorphine-related (both prescribed and non-prescribed) overdoses (Lee et al., 2014; Nielsen et al., 2007), which is particularly concerning given the association between receiving a greater methadone dose and benzodiazepine misuse (Bleich et al., 1999; Bleich et al., 2002; Darke et al., 1993; Rooney et al., 1999; Swensen et al., 1993). Notably, samples of people with OUD vary in their awareness of the heightened risk for overdose when opioids and benzodiazepines are combined (Motta-Ochoa et al., 2017; Neira-Leon et al., 2006; Rowe et al., 2016; Stein et al., 2017b; Strang et al., 1999).

3.5.2. Suicidal Behaviors.

Benzodiazepine misuse is also associated with suicidal ideation and attempt in numerous populations (Table 4). Notably, a recent analysis of older adult NSDUH respondents found that misuse of benzodiazepines was associated with suicidal ideation, whereas use as prescribed was not, after adjusting for mental health variables (Schepis et al., 2019). To our knowledge, only one longitudinal study has attempted to explain mechanisms underlying the association between benzodiazepine misuse and suicidal behaviors. This study found that depressive symptoms partially mediated associations between benzodiazepine misuse and suicidal ideation and attempt (Guo et al., 2016), whereas others have identified an association between benzodiazepine misuse and suicidal behaviors after controlling for psychiatric symptoms or disorders (Artenie et al., 2015a; Artenie et al., 2015b; Borges et al., 2000; Juan et al., 2015).

Another potential explanation is that benzodiazepines are used as a means to attempt suicide by intentional overdose, a method that is common among those with SUDs (Darke and Ross, 2001; Neale, 2000). Furthermore, two recent analyses of NSDUH data found that those with concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid misuse had a higher rate of suicidal ideation, as compared to those with benzodiazepine or opioid misuse alone (Schepis et al., 2019; Schepis et al., 2018b). These findings underscore the need to further understand the relationship between benzodiazepine misuse, polysubstance use, and suicidal behaviors.

3.5.3. Infectious Disease and Associated Behaviors.

The association between benzodiazepine misuse and overall mortality among those with opioid use and/or injection drug use might also be explained, in part, by higher rates of HIV and HCV infection in this population (Table 4). These findings are consistent with evidence that benzodiazepine misuse is associated with HIV/HCV risk-taking behaviors, such as injection drug use, unsafe injection practices (e.g., sharing needles, not cleaning needles, etc.), and risky sexual behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, multiple partners, prostitution) (Table 4). It is possible that the disinhibiting effects of benzodiazepines might increase the likelihood of risky behaviors. In studies of individuals with cocaine and/or opioid use, participants reported engaging in risky sexual behaviors during benzodiazepine intoxication (Johnson et al., 2013), and that benzodiazepines “slowed their thinking” and made them “not too conscious about risk” (Motta-Ochoa et al., 2017). Elevated rates of benzodiazepine prescriptions among those with HIV/HCV (Wixson and Brouwer, 2014) might also increase risk of misuse in this population through increased availability and exposure.

3.5.4. Criminality.

Benzodiazepine misuse has been retrospectively associated with criminal involvement among those with opioid use and/or injection drug use, as well as in a population-based study of adolescents in the U.S. (Table 4). Participants in several qualitative studies have reported intentionally misusing benzodiazepines prior to criminal behavior to become disinhibited or to gain the “confidence” to commit a crime (Calhoun et al., 1996; Dåderman and Lidberg, 1999; Forsyth et al., 2011; Fountain et al., 1999; Payne and Gaffney, 2012; Ruben and Morrison, 1992). In particular, criminal involvement has been reported by those misusing flunitrazepam—a particularly potent benzodiazepine—which might be due to subjective effects that include “loss of control,” feelings of violence, and blackouts (Barnas et al., 1992; Calhoun et al., 1996; Dåderman and Lidberg, 1999). Qualitative findings also suggest that drinking alcohol in combination with benzodiazepines increases disinhibiting and violence-producing effects of these substances (Dåderman and Lidberg, 1999; Forsyth et al., 2011). However, these studies have recruited small samples from specific high-risk subgroups (e.g., male juvenile offenders reporting flunitrazepam misuse). Thus, the prevalence of benzodiazepine misuse to facilitate criminal behavior in the broader population remains unclear.

3.5.5. Treatment Outcomes.

The studies that have examined the impact of benzodiazepine misuse on SUD treatment outcomes (i.e., treatment retention, opioid relapse) have yielded different results depending on the time frame assessed. Specifically, ongoing benzodiazepine misuse during treatment is associated with substance use during and after treatment, whereas baseline benzodiazepine misuse has not consistently predicted substance use treatment outcomes (Table 4).

Studies examining the impact of benzodiazepine misuse on treatment retention have also yielded mixed results, regardless of time frame (Table 4). Nevertheless, previous studies indicate that benzodiazepine dependence is associated with more severe opioid withdrawal symptoms (de Wet et al., 2004) and poorer sleep during OUD treatment (Peles et al., 2009), which might influence reinitiation or continued opioid use. This association may also be dependent on broader substance use patterns. In two previous studies, benzodiazepine misuse in combination with stimulant misuse was associated with poor treatment outcomes (e.g., methadone non-adherence, early dropout), but benzodiazepine misuse alone was not (DeMaria et al., 2000; Raffa et al., 2007). These findings underscore the need to consider overall polysubstance use in future studies determining the impact of benzodiazepine misuse on treatment outcomes.

3.5.6. Quality of Life and Physical Health.

Benzodiazepine misuse and dependence have been associated with poorer self-reported quality of life, greater pain severity, sleep dysfunction, and repeated emergency department visits in a range of populations (Table 4). Yet, these associations have not been consistently studied and, to our knowledge, no longitudinal studies have attempted to test the directions of and mechanisms underlying these associations. In addition, few studies examining these associations have controlled for receipt of a benzodiazepine prescription, despite findings from two recent analyses of NSDUH data that poorer self-reported general health was associated with lower odds of misuse, as compared to use as prescribed (Blanco et al., 2018; Maust et al., 2018).

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings and Implications

The aim of this comprehensive review was to characterize the current state of the science on the epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse. Below, we summarize several key findings.

People with SUDs in the U.S. have rates of benzodiazepine misuse 3.5 to 24 times higher than the general population (Votaw et al., 2019), and the misuse of other substances is the most consistent and robust correlate of benzodiazepine misuse. In fact, it is unclear how frequently benzodiazepine misuse occurs in isolation, rather than as part of a pattern of polysubstance use. Answering this question will help identify factors influencing the development of benzodiazepine misuse and populations who might benefit from interventions to reduce benzodiazepine misuse. Based on the present review, it is likely that the misuse of benzodiazepines for multiple reasons partially explains the high prevalence of misuse among those with SUDs. Future studies evaluating motives for benzodiazepine misuse among other vulnerable populations, including those with psychiatric disorders and benzodiazepine prescriptions, are needed to understand the relationship between motives and benzodiazepine misuse incidence and severity.

People with psychiatric symptoms and disorders also appear to be more vulnerable to benzodiazepine misuse. This is consistent with findings that regulating negative affective and somatic states is the most common motive for benzodiazepine misuse. Yet, it is unclear if psychiatric distress is an antecedent or consequence of benzodiazepine misuse (or both), and findings from the reviewed studies provide partial support for both explanations. It is likely that greater psychiatric distress motivates misuse to relieve symptoms, and symptoms of psychiatric distress are also a consequence of acute or protracted benzodiazepine withdrawal. The association between psychiatric distress and benzodiazepine misuse underscores the importance of first considering non-benzodiazepine treatments (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, antidepressants) for psychiatric symptoms among those who are most likely to misuse benzodiazepines. Women are more likely to report misusing benzodiazepines to cope with negative affect, and associations between psychiatric distress and benzodiazepine misuse appear to be stronger in women than in men. Accordingly, women might particularly benefit from efforts to reduce benzodiazepine misuse and related harms that target negative affect.

Unsurprisingly, exposure to a benzodiazepine prescription is associated with likelihood of misuse. This link between a prescription and misuse may reflect greater access/exposure to benzodiazepines, greater abuse liability among those for whom these medications are likely to be prescribed, or purposeful seeking of prescriptions with the intention of misuse; likely all of these factors contribute to this association. This highlights the need to carefully assess for misuse risk when prescribing benzodiazepines. There are currently no validated screening measures for likelihood of benzodiazepine misuse; however, results from this review suggest that factors such as history of substance use disorders and greater psychiatric severity are markers of concern. It is important to note that benzodiazepine diversion was common among people with a benzodiazepine prescription. Safe medication storage and disposal education should also be standard practice for those prescribing benzodiazepines to help mitigate diversion and accidental exposure.

Benzodiazepine misuse encompasses heterogeneous presentations of motives, patterns, and sources. Most of the participants in the reviewed studies received benzodiazepines from a friend/family member with a prescription and misused benzodiazepines infrequently and for the purposes aligned with their indication (e.g., anxiety, insomnia). Yet, high-risk profiles were also documented, and included: frequent misuse, co-ingestion with other substances, obtaining from illicit sources, non-oral routes of administration, multiple motives for use, and significant health and functional consequences. High-risk profiles were mostly observed among those with SUDs, but not all individuals with SUDs exhibited these risky patterns, with many misusing benzodiazepines infrequently and for the purpose of coping, rather than to feel high.

Benzodiazepine misuse is associated with a range of consequences, including overdose, suicidal and risk-taking behaviors, infectious disease, criminality, poor SUD treatment outcomes, and low quality of life. Overall, little is known about mechanisms underlying these associations. Overdoses related to benzodiazepines are more likely during co-ingestion with opioids and/or alcohol, a common pattern of benzodiazepine misuse. Improving education about the increased risk of overdose when benzodiazepines are combined with opioids and/or alcohol is important in the context of continued increases in drug overdoses in the U.S. Benzodiazepine injection has also been associated with a number of these consequences, including overdose, infectious disease, and physical health issues. Benzodiazepine misuse and greater substance use severity (particularly polysubstance use) are consistently associated; substance use severity might be an overlooked factor confounding the association between benzodiazepine misuse and poor outcomes.

4.2. Limitations of the Current Literature

Although our review identified a large number of studies on the epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse (N=351), this literature has a number of limitations and gaps that present important areas of future study.

Inconsistency in the definition of misuse is perhaps the biggest limitation in the extant literature (Table 2). In the reviewed studies, the term misuse (also referred to as nonmedical use, abuse, recreational use, etc.) was used broadly and inconsistently, resulting in highly heterogeneous groups and hampering the ability to compare studies. Inconsistencies among studies in the use of terminology (e.g., misuse, nonmedical use, abuse) might also explain different findings on prevalence estimates, patterns of prescription drug misuse, and factors associated with prescription drug misuse. For example, the NSDUH survey modified its definition in 2015; the original definition (non-prescribed use or use that occurred only for the feelings/experiences the prescription drugs caused) was expanded to include use in any way a doctor did not direct, such as using without a prescription or in greater amounts/more often/longer than prescribed. Following the implementation of this expanded definition, the percentage of people reporting their own prescription as their most recent source of tranquilizers increased from 14.1% to 21.8% (CBHSQ, 2015a, 2016). Such findings underscore the importance of carefully defining misuse.

Two papers published a decade ago highlight the challenges in defining prescription drug misuse (Barrett et al., 2008; Boyd and McCabe, 2008). Yet, based on the present review, few steps have since been taken to improve upon the classification of benzodiazepine misuse. Several changes to current research practices may help to improve this ongoing issue. Most importantly, definitions should clearly convey what behaviors constitute misuse and clearly distinguish among these behaviors, including medication overuse (e.g., using one’s legitimate prescription at greater doses or more often than prescribed), nonmedical use (e.g., without one’s own prescription or a prescription obtained for a reason other than its intended indication), and other illicit use (e.g., buying or trading for medication on the streets). Future studies separating these different forms of misuse are also needed to determine their relative clinical significance. In addition, studies enrolling individuals with SUDs should not rely exclusively on benzodiazepine-positive urine drug screens (e.g., in studies examining medical records), given high rates of benzodiazepine prescriptions among those with SUDs (Abrahamsson et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2017a; Tjagvad et al., 2016). Urine-confirmed self-report and assessment for current prescriptions is needed in these populations.

A related limitation of the literature includes inconsistent definitions of prescription drug classes (Table 2). Surveys evaluating benzodiazepine misuse commonly combined benzodiazepines with other sedatives and tranquilizers (e.g., muscle relaxants, barbiturates, z-drugs) or included benzodiazepine products in separate categories (e.g., sedatives, tranquilizers, sleeping medications, anxiolytic medications). This presents a significant barrier to identifying trends that may be informative for public health interventions, such as educating prescribers on potential risks associated with benzodiazepine prescribing. This is a common challenge for population-based surveys, which aim to evaluate a wide range of substances while minimizing participant burden. However, the increasing public health burden of benzodiazepines highlights the necessity of specifically evaluating benzodiazepine products.

Finally, our understanding of benzodiazepine misuse is limited by the reliance on samples of people with opioid use and/or injection drug use or general population samples. This both introduces potential confounds (e.g., limits the ability to isolate the impact of benzodiazepine misuse relative to a broader pattern of polydrug use) and may leave vulnerable populations understudied. Most notably, little is known about the co-use of alcohol and benzodiazepines, despite elevated rates of benzodiazepine misuse among those with problematic drinking and increased risk of overdose when alcohol and benzodiazepines are combined. Future research is needed to identify individuals who are most vulnerable to alcohol and benzodiazepine co-use and motives for this combination. Other notable populations in need of additional research include those with psychiatric disorders and individuals with benzodiazepine prescriptions.

4.3. Future Research Directions

Little is known about benzodiazepine misuse trajectories over time. Longitudinal studies should examine risks for the development of misuse, factors influencing the transition from prescribed use to misuse and from oral routes of administration to non-oral routes of administration (including injection use), and factors influencing the escalation to SHA use disorder. In addition, longitudinal studies will help to determine the temporal associations between benzodiazepine misuse and potential consequences (e.g., suicidality, poor physical health). Such studies would inform the development of screening tools to identify people at the highest risk for benzodiazepine misuse and the identification of factors that may be important targets for the prevention and treatment of benzodiazepine misuse.

There is also a dearth of research on the prevention and treatment of benzodiazepine misuse and use disorder. Most treatment studies have focused on benzodiazepine tapers in people with long-term benzodiazepine prescriptions for anxiety or insomnia, and do not specifically focus on misuse (Morin et al., 2004; Otto et al., 2010). The development of effective interventions to mitigate benzodiazepine misuse is particularly important to reduce overdose risk. Of note, adding cognitive-behavioral therapy (particularly, interoceptive exposure-based treatment) to a slow benzodiazepine taper enhances success among people seeking to discontinue benzodiazepine prescriptions (Otto et al., 2010; Otto et al., 1993). Accordingly, such approaches may also have promise for the treatment of benzodiazepine misuse, particularly given the strong link between anxiety and benzodiazepine misuse (McHugh et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2017).

4.4. Limitations of the Present Review