Abstract

Uncertainty about how our choices will affect others infuses social life. Past research suggests uncertainty has a negative effect on prosocial behavior1–12 by enabling people to adopt self-serving narratives about their actions1,13. We show that uncertainty does not always promote selfishness. We introduce a distinction between two types of uncertainty that have opposite effects on prosocial behavior. Previous work focused on outcome uncertainty: uncertainty about whether or not a decision will lead to a particular outcome. But as soon as people’s decisions might have negative consequences for others, there is also impact uncertainty: uncertainty about how badly others’ well-being will be impacted by the negative outcome. Consistent with past research1–12, we found decreased prosocial behavior under outcome uncertainty. In contrast, prosocial behavior was increased under impact uncertainty in incentivized economic decisions and hypothetical decisions about infectious disease threats. Perceptions of social norms paralleled the behavioral effects. The effect of impact uncertainty on prosocial behavior did not depend on the individuation of others or the mere mention of harm, and was stronger when impact uncertainty was made more salient. Our findings offer insights into communicating uncertainty, especially in contexts where prosocial behavior is paramount, such as responding to infectious disease threats.

Keywords: uncertainty, prosocial behavior, social preferences, altruism, decision making, health care decisions

We constantly face decisions that might have consequences for others, and when our decisions do affect others we can never be certain about how they will react14–16. For instance, when there is uncertainty about whether a self-serving action will lead to a potentially negative outcome for others1 – even when there is just a small chance that it will4 – people are much more likely to act selfish than when uncertainty is absent. Similarly, if people are uncertain about whether their behavior will deplete a common resource, they are more likely to overharvest10,11. Such decreases in prosociality might occur because uncertainty enables people to adopt self-serving narratives that allow them to behave selfishly while maintaining a positive self-image17,18. Consistent with this idea, when decision outcomes are uncertain people optimistically underestimate the chance that self-serving behavior will cause negative outcomes for others, making self-serving behavior appear more appropriate to oneself1,13, 19,20. Perceptions of social norms – shared beliefs about what people should do in a given situation – mirror these results: self-interested behavior when outcomes are uncertain not only appears appropriate to oneself, but also to others21.

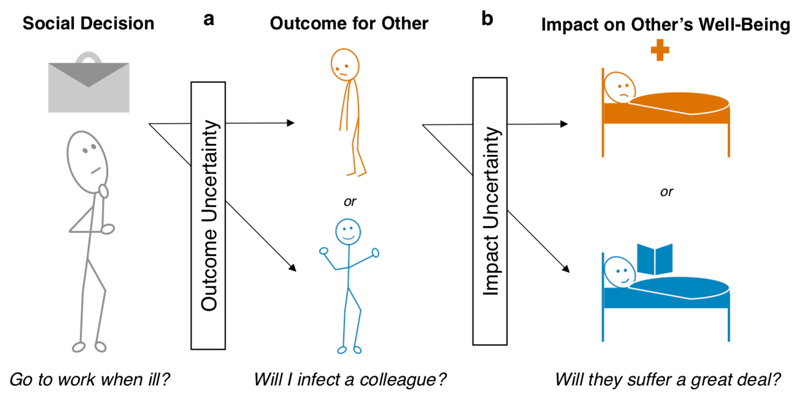

We propose that past research on uncertainty and prosocial behavior has overlooked the possibility that there are different types of uncertainty that may have distinct effects on prosocial behavior. Previous work has focused on what we will call outcome uncertainty: “the psychological state in which a decision maker lacks knowledge about what outcome will follow from what choice”22. In the context of social decision-making, most past studies have induced uncertainty about whether or not a decision will lead to a negative outcome for others (Fig. 1a). A person might lack knowledge about whether or not, for instance, she will infect another co-worker if she goes to work while sick with the flu, or if a donation will actually reach the people in need. But outcome uncertainty is only one type of uncertainty present in social interactions. As soon as people’s decisions might have consequences for others, they may also lack knowledge about how others’ well-being will be impacted by the outcomes of those decisions (Fig. 1b). For example, a person might lack knowledge about how badly the flu will impact a co-worker’s well-being, or how much a donation will actually improve the welfare of another person. This type of uncertainty, which we will call impact uncertainty, is uncertainty related to how much the well-being of others will be affected by a particular outcome.

Figure 1.

A decision might cause a potentially negative outcome for another person, and the negative outcome may have a negligible or large impact on their well-being. (a) Outcome uncertainty is uncertainty about whether or not a decision will cause a negative outcome for another person. In the depicted example, the decision to go to work when feeling ill might or might not lead to infecting a colleague. (b) Impact uncertainty is uncertainty about how badly the other person’s well-being will be impacted by the negative outcome. In the depicted example, infecting a colleague with a disease might cause them a great deal of suffering, or the infection might have only a mild effect.

Outcome and impact uncertainty may arise in relation to the same event (e.g., infecting another person with the flu), but they correspond to different aspects of this event. Outcome uncertainty occurs when a decision-maker lacks knowledge about whether an event (e.g., infecting another person) will occur following a particular choice (e.g. going to work while sick), and as such bears on the decision-maker’s causal responsibility for the outcome. In contrast, impact uncertainty occurs when a decision-maker lacks knowledge about how an event (e.g., infecting another person) will impact the well-being of another person (e.g., how badly they will suffer from the infection), and thus relates to the welfare of another person. These two dimensions may respectively contribute to assessments of responsibility and harm magnitude, which independently influence moral judgments24. We note that the conceptual distinction between “outcomes” and “impact” does not correspond with constructs in standard decision theory23; while outcome uncertainty indexes uncertainty about states of the world, impact uncertainty indexes uncertainty about subjective utilities over those states. To support our proposition that outcome and impact uncertainty relate to different assessments that might arise in relation to the same event, we demonstrated that laypeople can reliably distinguish between them in real-world scenarios (see Supplementary Methods).

In contrast to outcome uncertainty, little is known about how impact uncertainty affects social behavior. This is surprising because impact uncertainty is omnipresent in social interactions: people often lack knowledge about how badly others will be impacted by the outcomes of their decisions, in large part because other people’s subjective experiences are often inaccessible14,15.

Previous research has investigated how people predict the preferences of others, such as preferences about birthday presents25, possessions26, financial or romantic advice27– 31, and forgiveness32. This work demonstrates that people often struggle to accurately predict the impact of outcomes on others, even for very close others on important matters such as end of life care for a terminally ill spouse33. Moreover, people are at least partially aware of the lack of insight they have into how others will be impacted by an outcome, with the resulting uncertainty inducing stress and anxiety while making decisions for others, and thereafter doubt and guilt over the decisions made34,35. However, it remains unclear how the experience of impact uncertainty affects prosocial behavior.

If impact uncertainty activates self-serving narratives in a similar way to outcome uncertainty, then people may similarly exploit impact uncertainty to justify self-serving behavior. For example, when deciding whether to share money with a stranger whose income level is unknown, people might optimistically assume the stranger is rich and thus would benefit little from generosity, creating a self-serving justification for being stingy. However, a recent study suggests that impact uncertainty may increase rather than decrease prosociality, perhaps by activating a different set of narratives around protecting others’ welfare36. Participants in this study chose between different amounts of money in exchange for different numbers of electric shocks delivered to either themselves or an anonymous other person. Strikingly, most people were more averse to harming others than themselves. There was no outcome uncertainty in this experiment, but many participants explained their behavior by appealing to impact uncertainty (e.g., “I knew what I could handle but I was less sure about the other person and didn’t want to be cruel”), and behavioral indices of uncertainty predicted prosocial behavior36. This suggests impact uncertainty may induce precautionary social preferences, where people prefer to avoid the worst-case scenario.

Thus, impact uncertainty might activate different narratives than outcome uncertainty, and consequently have different effects on prosocial behavior. While outcome uncertainty introduces optimistic and self-serving narratives that mitigate personal responsibility, impact uncertainty may lead people to think more about protecting the welfare of potentially vulnerable others, and thereby increase prosocial behavior. To test these hypotheses, we independently manipulated impact uncertainty and outcome uncertainty within modified Dictator Games (Studies 1-3) and infectious disease scenarios (Study 6). In order to test if it is indeed impact uncertainty that drives the observed effects, we examined if simply mentioning the negative impact (Study 4), or any type of uncertainty about the other person (Study 5) produce similar results. Finally, we tested if people are reluctant to contemplate the harm they might cause to others (Study 7) and if this reluctance can be overcome by making impact uncertainty salient.

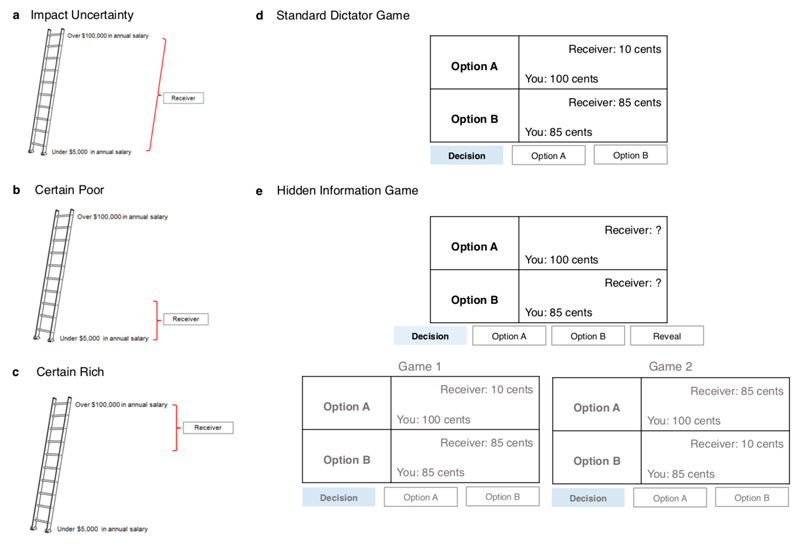

To manipulate impact uncertainty, we varied the information participants received about the people potentially affected by their decisions. Specifically, in the studies that involved Dictator Games, we varied the information participants received about the income level of the Receiver they were paired with (Fig. 2a-c). All participants in the experimental conditions learned that some of the Receivers are “near the bottom of the income scale” and “are very dependent on the money they earn to help supplement their income to pay for food and shelter” while others are “at the top of the income scale” and would use the money “to earn a bit of extra spending money, e.g., to use for entertainment.” In the impact uncertainty condition, participants were then told “The Receiver might rank near the top of the income scale, or they might rank near the bottom, or somewhere in the middle.”

Figure 2.

Depiction of uncertainty manipulations across experimental conditions. (a) Participants in the impact uncertainty condition learned that with equal chances, the Receiver could be either poor, rich, or somewhere in between. (b) Participants in the certain-poor condition learned that the Receiver was poor. (c) Participants in the certain-rich condition learned that the Receiver was rich. d) Participants in the outcome certainty condition played a standard binary Dictator Game e) Participants in the outcome uncertainty condition played a Hidden Information Game. A virtual coin flip decided on whether Game 1 or Game 2 would be played. In Game 1, Option A would result in 10 cents for the Receiver, but in Game 2 in 85 cents. In Game 1, Option B would results in 85 cents for the Receiver, but in Game 2 in 10 cents for the Receiver. Participants had the chance to reveal which game was played before making the decision.

Our main goal was to test if people exploit impact uncertainty just like outcome uncertainty and use it to license selfishness, or if instead impact uncertainty promotes prosocial behavior. We included two different conditions in our experiments to test these competing hypotheses, a certain-rich and a certain-poor condition. In the certain-rich condition, we told participants that “The Receiver ranks near the top of the income scale.” If participants exploit impact uncertainty to justify self-serving behavior and optimistically assume their Receiver is rich, prosocial behavior in the impact uncertainty condition should match prosocial behavior in the certain-rich condition. In the certain-poor condition, we told participants that “The Receiver ranks near the bottom of the income scale”. If participants adopt precautionary preferences under impact uncertainty – as we suggest – then behavior in the impact uncertainty condition should match behavior in the certain-poor condition.

We also included a control condition in which participants did not receive any information about income in general or their Receiver’s income in particular. This control condition mirrors how previous research has implemented Dictator Games37 allowing us to examine if the introduction of impact uncertainty increases or decreases prosocial decision-making in comparison to the standard used in decades of research. Furthermore, in everyday life, impact uncertainty is most often implicitly present but not explicitly mentioned, similar to our control condition. Hence, this control condition allows us also to observe if impact uncertainty increases prosociality compared to the conditions encountered in everyday life.

To manipulate outcome uncertainty in the Dictator Games, we replicated the methods of a previous study investigating how outcome uncertainty affects prosocial behavior1. Participants played either a standard binary Dictator Game (Fig. 2d), where a self-serving choice led deterministically to a worse outcome for the Receiver (no outcome uncertainty), or a Hidden Information Game, where a self-serving choice led probabilistically to a worse outcome for the Receiver (outcome uncertainty; Fig. 2e) but participants had the chance to reveal the outcome of the self-serving option beforehand at no cost.

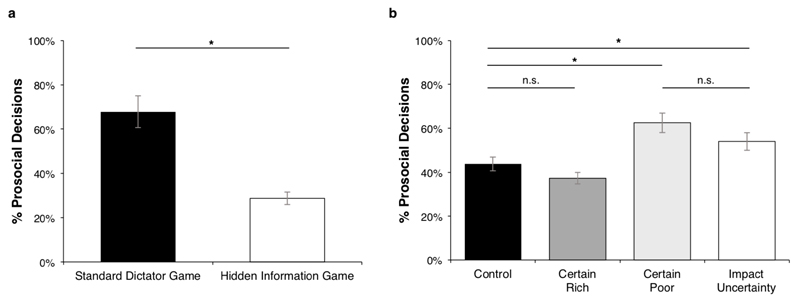

We used generalized linear models to test the main effects of outcome uncertainty, impact uncertainty, and their interaction on prosocial decisions. Thereafter, we tested the simple effects of outcome uncertainty and impact uncertainty with chi-square tests in order to determine how the conditions affected the distribution of prosocial behaviors in our samples. The model predicted decision type (self-serving or prosocial) with separate regressors for outcome uncertainty (type of Dictator Game: standard, hidden information), impact uncertainty (Receiver information: uncertain, certain-poor, certain-rich, control), and the interaction between outcome and impact uncertainty. As the dependent variable in the Standard Dictator Game, we coded whether participants chose the prosocial option (Figure 2d, Option B). In the Hidden Dictator Game, we coded whether participants chose the reveal option and subsequently took the prosocial option (Fig. 2e Game 1, Option B, and Fig. 2e, Game 2, Option A). We found main effects of outcome uncertainty (χ2(1, N = 832) = 117.84, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.81) and impact uncertainty (χ2(3, N = 832) = 29.33, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.38), but no interaction (χ2(3, N = 832) = 2.99, p = .39). Consistent with previous research1–3, 5,6,38, outcome uncertainty reduced prosocial behavior (Fig. 3a). All of our observed effects remained significant when controlling for participants’ income level (see Supplementary Notes).

Figure 3.

a) Percentage of prosocial decisions for the Standard Dictator Game and the Hidden Information Game in Study 1 (N = 833). b) Percentage of prosocial decisions for the four Receiver information conditions: control condition, certain-rich, certain-poor, and impact uncertainty condition in Study 1 (N = 833). Error bars represent standard errors. *p < 0.01, n.s. = not significant.

We next examined the effect of impact uncertainty on prosocial behavior. First, we confirmed that participants were sensitive to the income level of Receivers by comparing the proportion of prosocial choices when the Receiver had a low income (certain-poor condition) versus high income (certain-rich condition). Indeed, participants in the certain-rich condition were less prosocial than those in the certain-poor condition (χ2(3, N = 417) = 26.43, p < .001). To investigate whether this difference was driven by increased generosity toward low-income Receivers or by decreased generosity toward high-income Receivers, we compared each of these conditions with the control condition where participants received no information about the income level of the Receivers. As found in previous work39–41, participants in the certain-poor condition were significantly more prosocial than those in the control condition (χ2(1, N = 418) = 14.67, p = .001, Cramer's V = .19). Meanwhile, participants in the certain-rich condition were not significantly less prosocial than those in the control condition, (χ2(1, N = 419) = 1.81, p = .18, Cramer's V = .06). This suggests the difference in prosociality between the certain-rich and certain-poor conditions was driven by increased generosity towards low-income Receivers.

To test our main prediction that impact uncertainty increases prosocial behavior, we compared the uncertainty condition with each of the other three conditions. Participants were significantly more prosocial in the uncertainty condition relative to the certain-rich condition (χ2(1, N = 416) = 14.64, p = .001, Cramer's V = .19). These results speak against a self-serving exploitation of impact uncertainty, which would predict that participants assume the Receiver in the uncertain condition is rich and thus behave similarly in the uncertain and certain-rich conditions. In contrast, the proportion of prosocial choices in the uncertain condition was not significantly different from that in the certain-poor condition (χ2(1, N = 415) = 1.80, p = .18, Cramer's V = .06). These results suggest that participants in the uncertainty condition erred on the side of caution rather than exploiting uncertainty about the impact on the Receiver for their own benefit. Finally, participants in the uncertainty condition were significantly more prosocial than in the control condition (χ2 (1, N = 417) = 6.23, p = .01, Cramer's V = .12), suggesting that explicitly mentioning impact uncertainty increases its effect on prosocial behavior.

One potential alternative explanation for our findings is that participants believed that the average MTurk participant was low-income. If so, it would be sensible to assume in the uncertainty condition that the Receiver is likely to be low-income, and behave accordingly. We ruled out this explanation in two ways. First, we repeated our analysis of impact uncertainty controlling for participants’ beliefs about the average income level of Receivers. The effects of impact uncertainty on prosocial behavior remained significant when controlling for these beliefs, and participants’ beliefs about the average income level of Receivers did not interact with any of our observed effects (see Supplementary Notes). Second, we conducted a new experiment in which we explicitly controlled participants’ beliefs about the income level of the Receiver (Study 2). In this study, participants in the impact uncertainty condition were instructed: “We pre-selected three Receivers: a high-income Receiver, a low-income Receiver, and a middle-income Receiver. You will be paired with ONE of these Receivers at random.” Using this belief manipulation, we fully replicated the effects of both outcome and impact uncertainty in Study 2 (see Supplementary Notes).

In a third study, we showed that the opposing effects of outcome and impact uncertainty on prosocial behavior are paralleled at the level of beliefs about social norms, measured via an incentivized coordination game (see Supplementary Notes). Since general beliefs about social norms are independent from specific beliefs about a particular social interaction (including beliefs about the income of the Receiver), the fact that participants believe that others think selfish behavior is wrong when facing impact uncertainty, but acceptable when facing outcome uncertainty, lends further support to our claim that impact and outcome uncertainty activate distinct narratives about the appropriateness of self-serving behavior.

One might wonder, however, if impact uncertainty is indeed necessary to increase prosocial behavior, or if simply mentioning relative income or the worst possible case is sufficient to produce similar results. In Study 4, we tested if just mentioning the possibility of the Receiver being poor, rather than introducing uncertainty about it, is sufficient to increase prosocial behavior. In this study the control condition explicitly mentioned that online participants come from all walks of life, some “are poor (meaning their income is below the poverty threshold) and are very dependent on the money they earn on Prolific to help supplement their income to pay for food and shelter”. We induced impact uncertainty by informing participants that the Receiver might be either poor or rich with a probability of 50% each (Supplementary Methods for details). Again, we found that participants in the impact uncertainty condition behaved more prosocially than participants in the control condition, (χ2 (1, N = 401) = 5.72, p = .018, Cramer's V = .12), and just as prosocially as participants in the certain-poor condition, (χ2(1, N = 400) = 0.035, p = .852, Cramer's V = .009), suggesting that it is indeed uncertainty about the impact of one’s decision that drives the increase in prosocial behavior.

Study 4 also investigated the question of what level of impact uncertainty may be necessary to enhance prosocial behavior. In the studies reported so far, participants either faced moderate (33% chance of Receiver being poor), or relatively high (50% chance of Receiver being poor) levels of impact uncertainty. In both cases, participants acted more prosocially relative to the control condition. In Study 4 we included a low impact uncertainty condition, in which participants learned that their Receiver might be poor with 10% chance, or rich with a 90% chance. The low impact uncertainty condition was not significantly different from the control condition, p = .284, leaving open the question of the lowest possible threshold required to elicit impact uncertainty’s effect on prosocial behavior.

Study 4 also included measures of cognitive and affective empathy (QCAE)42 and wise reasoning43 to investigate whether impact uncertainty’s prosocial effect depends on individual differences. While we found significant main effects of cognitive and affective empathy, as well as wise reasoning, on prosocial behavior, the conditional effect of impact uncertainty remained significant when we controlled for these individual differences. However, exploratory analyses suggested that the effects of impact uncertainty on prosocial behavior may be partially mediated by cognitive empathy (see Supplementary Methods for details and further exploratory analyses).

We next turned to a potential alternative explanation for our findings: one might argue that it is not necessarily uncertainty about the impact of the outcomes on another person that drives the increase in prosociality, but rather that uncertainty about any individuating aspect of the Receiver might be sufficient. Indeed, previous work has shown that individuation of others increases prosocial behavior towards them44–46. Thus, reading that the Receiver “might be rich, poor, or something in between” in our instructions may have induced participants to think about the Receiver as an individual, resulting in increased prosocial behavior under impact uncertainty. If this was the case, then we should observe increased prosociality under uncertainty even when the dimension participants are uncertain about is irrelevant to the potential harm caused by the outcomes. For instance, it might be sufficient to induce uncertainty about whether or not the Receiver is extroverted or introverted.

To test this alternative hypothesis, we provided participants with different information about the Receiver’s extroversion (Study 5). Participants randomly assigned to the uncertain condition read that the Receiver “could be extroverted, introverted, or somewhere in between”. In the certain-extrovert and certain-introvert conditions, participants read that the Receiver is extroverted or introverted respectively, while participants in the control condition did not receive any additional information about the Receiver. We did not find a significant difference in prosocial decisions across conditions (χ 2(3, N = 862) = .94, p = .82). Thus, participants made as many prosocial choices under impact uncertainty (73%) as they did when being certain about the Receiver’s intro-/extroversion (both conditions 72%), or when they did not learn any information about the Receiver at all (69%). Taken together, our results show that the increase in prosocial behavior in our experiments was due to uncertainty about the negative impact of one’s actions on others as opposed to simply mentioning negative impact (Study 4) or inducing any kind of uncertainty about the other person (Study 5).

Next, we examined if the effects of impact uncertainty are restricted to economic decisions by testing if we can replicate the results using hypothetical medical decisions concerning the threat of infectious disease. We chose infectious disease since fighting the threat of them depends on behaviors with social consequences (e.g., vaccinations, hygiene, or isolation). In Study 6, participants were asked to imagine the following scenario: “Eight days after you arrived back from a lovely Safari trip to Tanzania, Africa, you feel unwell: feverish and dizzy. You go to the doctor and learn that you have the African Flu. The doctor warns you that African Flu is contagious: people you come into contact with may get infected. [The following sentence differed across condition, see below and Supplementary Methods]. However, you still feel able to work and you really want to go to the office for finishing a project that is important for your career.” (Supplementary Methods for complete instructions). Participants were then asked to indicate how likely they were to stay home (prosocial intention).

We manipulated impact uncertainty by varying the information participants received about the vulnerability of people they might infect at work. Participants in the impact uncertainty condition read that if they would go to work, there was a chance they would infect a young co-worker, for whom the African Flu would be unproblematic, but also a chance they would infect an old co-worker, for whom the African Flu would be dangerous. This impact uncertainty condition was compared to a worst-case condition, in which participants learned that if they would go to work they would infect an old co-worker, and to a control condition in which they did not receive additional information about the vulnerability of their co-workers. We found that participants in the impact uncertainty and the worst-case condition were significantly more likely to stay home compared with participants in the control condition (U = 60.75, p = .004, η2 = .075; U = 90.653, p < .001, η2 = .075). Again, we found no difference in prosocial intention under impact uncertainty compared to the worst-case condition (p = .343); under impact uncertainty people formed similar intentions to protect others as when the worst case was certain.

Our findings suggest that under impact uncertainty, people consider the potential harmful impact of their actions on others, leading them to err on the side of caution. Yet, people are often reluctant to consider how others could be harmed by their decisions43. It may be that the effects of impact uncertainty rely on overcoming a reluctance to consider harming others, and are only induced if the possibility of others’ suffering is made salient to a degree at which people can no longer neglect this possibility when forming a decision. We tested this in a final study, by manipulating the salience of the uncertainty information. We manipulated salience by repeating information, which is one of the most effective ways to increase the salience of information47 and the likelihood that people attend to this information48,49.

We included three conditions where the income of the Receiver was uncertain, a fact that was made salient to different degrees. In the control condition, participants did not receive any information about the Receiver’s income. In the low salience condition, participants were told that “MTurkers come from all walks of life”, additionally mentioning that some “are very dependent on the money they earn on MTurk to help supplement their income” while others “use MTurk as a way to earn a bit of extra spending money”. Then, we told them that “We pre-selected three Receivers: a high-income Receiver, a low-income Receiver, and a middle-income Receiver. You will be paired with ONE of these Receivers at random.” In the high salience condition – which matched our previous impact uncertainty manipulations – participants received the same information, but we additionally highlighted impact uncertainty by telling participants “The Receiver might rank near the top of the income scale, or they might rank near the bottom, or somewhere in the middle.” We found a significant difference in the proportion of prosocial decisions across conditions (χ 2(2, N = 468) = 6.02, p = .049, Cramer’s V = .11). Paired comparisons showed that participants in the high salience condition were more prosocial than participants in the low salience condition (χ 2(1, N = 314) = 5.15, p = .023, Cramer’s V = .13) and the control condition (χ 2(1, N = 311) = 4.39, p = .036, Cramer’s V = .12), which did not differ from one another (p = .86).

To summarize, we show that uncertainty does not always decrease prosocial behavior; instead, the type of uncertainty matters. Replicating previous findings1–3 ,6,13, 38,50, we found that outcome uncertainty – uncertainty about the outcomes of decisions – made people behave more selfishly. However, impact uncertainty about how an outcome will impact another person’s well-being increased prosocial behavior, in economic and health domains. Examining closer the effect of impact uncertainty on prosociality, we show that for the increase in prosociality to occur, simply mentioning negative outcomes or inducing uncertainty about aspects of the other person unrelated to the negative outcome is not sufficient to increase prosociality. Rather, it seems that uncertainty relating to the impact of negative outcomes on others is needed to increase prosociality in our studies. Finally, we show that impact uncertainty is only effective when it is salient, thereby potentially overcoming people’s reluctance to contemplating the harm they might cause.

Recent theoretical work highlights the power of stories (or narratives) people tell themselves (and others) to justify self-serving behavior17. Applied to our findings and supported by Study 3, this framework suggests that outcome uncertainty activates self-focused narratives that enable people to tell themselves that it is very unlikely that a negative outcome for the other person will occur, allowing them to reap the benefits of self-interested actions without feeling selfish17. Such self-focused narratives decrease prosociality by downplaying the potential social costs of self-interested actions. In contrast, our findings suggest that impact uncertainty activates other-focused narratives that include potential social costs, leading participants to adopt behaviors that preserve others’ welfare. Notably, such other-focused narratives might also cater for self-image concerns (e.g., “only a horrible person would risk infecting a vulnerable other”). Future work, perhaps combining qualitative with quantitative methods, might more directly investigate the content of the narratives motivating people’s social behavior and use these insights to explain how uncertainty encourages (or discourages) prosocial behavior.

Another important avenue for future research is to examine how other situational features factor into impact uncertainty’s effect on prosociality. We find, for instance, that effect sizes for high and moderate levels of impact uncertainty (50% and 33% chance of negative impact) are similar, whereas the effect size for low impact uncertainty (10% chance of negative impact) is substantially lower. Based on this observation, we tentatively propose that representations of the expected harmfulness of one’s decision’s impact on others could be described as a convex function that is increasingly steep under impact uncertainty: above a certain level, impact uncertainty uniformly affects prosocial behavior such that people choose whatever option minimizes harm to others. One might speculate that this threshold level depends on further features of the situation. For example, people might be more prone to minimize harm and act prosocially if the harm is physical versus non-physical. People might be willing to maximize their personal outcomes under a 1% chance that another person receives 75 cents less, but people might not be willing to maximize their personal outcomes if there is a 1% chance that they could endanger a pregnant women and the unborn child with an infectious disease.

Our findings highlight the potential for using impact uncertainty to nudge people towards prosociality. For instance, we found that participants facing impact uncertainty reported they would be more willing to adopt behavior that would help containing the threat of infectious disease, highlighting the relevance of our findings for addressing global threats. While the communication of such global threats often emphasizes outcome uncertainty (e.g., “What Are the Chances of a Devastating Pandemic Occurring in the Next 50 Years?”51), impact uncertainty is rarely communicated. Our work suggests, however, that when communicating uncertainty, policy makers, public health officials, and others should consider which type of uncertainty they intend to communicate. Since outcome uncertainty biases people towards self-interested behavior, highlighting impact uncertainty instead may lead to more prosocial decision-making.

Methods

All studies were approved by the University of Oxford’s Central University Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: MSD-IDREC-C1-2014-005) and participants in each study gave their informed consent beforehand.

Study 1

Participants

We determined sample size using G-Power 3.152 (See SI methods). A total of 833 participants were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT or MTurk). AMT provides reliable participants who are ethnically and socioeconomically more diverse than university-recruited participants53,54. We paid participants in line with US minimum wage.

Procedure

Participants were instructed that their decision determined the exact monetary amount themselves and a Receiver would obtain. The experiment did not involve deception as a corresponding number of Receivers was randomly recruited from unrelated studies on MTurk and paid according to participants’ choices. We manipulated outcome and impact uncertainty as between-subject factors with two and for levels respectively.

To manipulate outcome uncertainty, each participant was randomly assigned to one of two conditions - Standard Dictator Game (outcome certainty) or Hidden Information Game (outcome uncertainty, see Fig.2, d & e). The standard Dictator Game (Fig.2, d) mirrored the baseline game in Dana and colleagues1. Here, participants were presented with two options, A and B. Option A – the self-serving option – meant that the Decider would receive 100 cents, and the Receiver would get 10 cents. Option B – the prosocial option – meant that the Decider would get 85 cents and the Receiver would get 85 cents. The Hidden Information Game was adapted form the uncertainty treatment in Dana and colleagues1. Participants first saw a game table that only specified the outcomes for the Decider (i.e., themselves), but not for the Receiver. If choosing Option A, participants would get 100 cents, if choosing Option B, participants would get 85 cents. The Receiver’s outcome would depend on a virtual coin-flip, determining whether Game 1 or Game 2 would be played. In Game 1, Option A would result in 10 cents for the Receiver, but in Game 2 in 85 cents. In Game 1, Option B would results in 85 cents for the Receiver, but in Game 2 in 10 cents for the Receiver. Participants learned that they could reveal which Game was played before making their decision at no cost. Hence, participants could choose Option A (the self-serving option), Option B, or reveal which game was being played before making their decision. If participants chose to reveal the game, they saw which game was played, and were then prompted to choose between Option A and B.

To manipulate impact uncertainty, each participant except those in the control condition read the following description of the Receivers: “MTurkers come from all walks of life, with different educational backgrounds and income levels. Some MTurkers, for instance, rank near the bottom of the income scale, and are very dependent on the money they earn on MTurk to help supplement their income to pay for food and shelter. Others rank in the middle-to-high end of the income scale, and use MTurk as a way to earn a bit of extra spending money, e.g. to use for entertainment.” Participants then were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: impact uncertainty, certain-poor, certain-rich, and control condition. Participants in the impact uncertainty condition read that “The Receiver might rank near the top of the income scale, or they might rank near the bottom, or somewhere in the middle.” Participants in the certain-poor condition read that: “The Receiver ranks near the bottom of the income scale.” Participants in the certain-rich condition learned that: “The Receiver ranks near the top of the income scale.” Participants in the control condition did not receive any information about the Receiver.

Study 2

Participants

A total of 1,320 participants were recruited via Prolific, a crowdsourcing platform to recruit participants online (prolific.ac) similar to AMT. Sample size was determined using effect size estimates from Study 1 and aimed at replicating findings with a power of .80.

Procedure

The procedure was the same as in Study 1, but we manipulated impact uncertainty differently in order to control for participants’ beliefs about Receivers’ income. This time, participants in the uncertain condition read: “We pre-selected three Receivers: a high-income Receiver, a low-income Receiver, and a middle-income Receiver. You will be paired with ONE of these Receivers at random. Thus, the Receiver you are paired with might rank near the top of the income scale, or they might rank near the bottom, or somewhere in the middle.”

Study 3

Participants

A total of 742 participants were recruited via AMT.

Procedure

To examine perceived social norms about the options presented in Studies 1-2, we used a mixed design with impact uncertainty as within-subjects factor (certain poor, certain rich, impact uncertainty) and outcome uncertainty (standard Dictator Game, Hidden Information Game) as between-subjects factor. All participants played an incentivized coordination game21. In this game, they were presented with the same instructions that participants saw in Studies 1-2, but instead of deciding themselves between Options A and B, they were asked to indicate how “socially appropriate” or “socially inappropriate” each of these options were (for details see SI methods).

Study 4

Participants

A total of 807 participants were recruited via Prolific.

Procedure

We used a between-subjects design with an independent variable of four levels, high impact uncertainty, low impact uncertainty, certain poor, and control. The procedure was the same as in Study 1 with the Standard Dictator Game, but this time all participants – including those in the control condition – read the following general information about Receivers: “Prolific Workers come from all walks of life, with different educational backgrounds and income levels. Some Prolific Workers, for instance, are poor (meaning their income is below the poverty threshold) and are very dependent on the money they earn on Prolific to help supplement their income to pay for food and shelter. Other Prolific Workers have a high income, and use Prolific as a way to earn a bit of extra spending money, e.g. to use for entertainment”. Deciders in the high impact uncertainty condition were then told that there was a 50% chance that their Receiver was poor, and a 50% chance that they were rich. In Studies 1-3, we had told Deciders that their Receiver may be poor, or rich, or somewhere with a 33% probability each. We now used only the two extremes (i.e., poor and rich) with a 50% split, because it is not intuitive what the norm for behavior towards a middle-income Receiver should be and in fact this aspect is not relevant to our research question. Participants in the low impact uncertainty condition were told that there was a 10% chance their Receiver was poor and a 90% chance their Receiver was rich. The certain poor condition was the same as in Study 1. After participants made their decision in the Dictator Game, they answered questions about their demographics and completed individual differences measures. These included a measure of cognitive and affective empathy with well-established psychometric properties, QCAE42 and a measure of wise reasoning43.

Study 5

Participants

A total of 862 participants were recruited via AMT.

Procedure

In a between-subjects design, participants learned that we pre-selected three types of Receivers – an extroverted Receiver, an introverted Receiver, and a Receiver who ranks in the middle – and that they would be randomly paired with one of them. Mirroring the impact uncertainty manipulation used in Studies 1-2, participants in the certain-extrovert condition learned that the Receiver was extroverted, participants in the certain-introvert condition learned that the Receiver was introverted, and participants in the control condition did not receive any information about the Receiver. Thereafter, all participants played the Standard Dictator Game (Figure 2d).

Study 6

Participants

A total of 903 participants was recruited via AMT.

Procedure

We used a 3 (uncertainty: impact uncertainty vs worst-case certainty vs control) by 2 (possibility: implicit vs explicit) between-subjects design to replicate our previous finding’s robustness using a scenario-based paradigm and to investigate whether impact uncertainty shifts people’s representation of possible outcomes for others towards the worst-case possibility. Manipulations for the uncertainty conditions were based on a fictive scenario set in the context of infectious disease. The implicit versus explicit possibility manipulation was based on a paradigm introduced recently55 (see SI notes). The introductory text for the infectious disease scenario was the same across all conditions and read “Eight days after you arrived back from a lovely Safari trip to Tanzania, Africa, you feel unwell: feverish and dizzy. You go to the doctor and learn that you have the African Flu. The doctor warns you that African Flu is contagious: people you come into contact with may get infected [This middle part differed across conditions, see below]. However, you still feel able to work and you really want to go to the office for finishing a project that is important for your career”. The scenario middle-part differed across uncertainty conditions: in the impact uncertainty condition, participants learned there “is a chance that you would infect co-workers who are healthy people for whom the African Flu is unproblematic (e.g., a young person) so that they would only barely suffer. But there is also a chance that you would infect co-workers who are vulnerable people (e.g., an old person) for whom the African Flu is very dangerous so that they would suffer severely”. In the worst-case certainty condition, participants learned that most co-workers were vulnerable and hence that if they would go to work, they were most likely to infect a vulnerable person. Participants in the control condition did not receive any information related to the vulnerability of their co-workers. Participants then made two possibility judgments (possibility that co-workers are vulnerable; possibility to infect co-workers) presented in random order either under time pressure (implicit condition), or without time limit (explicit condition; see SI methods for exemplary instructions). Following their possibility judgment, participants proceeded to indicate whether they would go to work in the scenario they had read, or not, on a 7-point Likert scale from “definitely not” to “definitely”.

Study 7

Participants

A total of 468 participants were recruited via Prolific.

Procedure

We used a between-subjects design. In the low salience condition, participants read that we had pre-selected one high income, one middle income, and one low income Receiver, and that they would be randomly paired with one of these three Receivers. In the high salience condition, participants were additionally told: “The Receiver might rank near the top of the income scale, or they might rank near the bottom, or somewhere in the middle.” In the control condition, participants did not receive any information about the Receiver’s income before making their decisions. Thereafter, all participants played the Standard Dictator Game (Figure 2d).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund award (204826/Z/16/Z) and the Oxford Martin School (Oxford Martin Programme on Collective Responsibility for Infectious Disease). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Daniel Batson, and members of the Crockett and MAD labs for helpful feedback.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A.K and M.J.C. developed the research concept. A.K., M.J.C., and A.-M.N. designed the studies. Testing and data collection were performed by A.K and A.-M.N. A.K. performed the data analysis and interpretation in collaboration with A.-M.N. and M.J.C. A.K, A.-M.N. and M.J.C. drafted the manuscript and all other authors provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Financial and non-financial competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Dana J, Weber RA, Kuang JX. Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ Theory. 2007;33:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exley CL. Excusing Selfishness in Charitable Giving: The Role of Risk. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson T, Capra CM. Exploiting moral wiggle room: Illusory preference for fairness? A comment. Judgm Decis Mak. 2009;4:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamman JR, Loewenstein G. Weber RA Self-interest through delegation: An additional rationale for the principal-agent relationship. Am Econ Rev. 2010:1826–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brock JM, Lange A, Ozbay EY. Dictating the Risk: Experimental Evidence on Giving in Risky Environments. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103:415–437. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feiler L. Testing models of information avoidance with binary choice dictator games. J Econ Psychol. 2014;45:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Güth W, Levati MV, Ploner M. On the Social Dimension of Time and Risk Preferences: An Experimental Study. Econ Inq. 2008;46:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan G, González LG, Güth W, Levati MV. Attitudes toward private and collective risk in individual and strategic choice situations. J Econ Behav Organ. 2008;67:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreoni J, Bernheim BD. Social Image and the 50–50 Norm: A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Audience Effects. Econometrica. 2009;77:1607–1636. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budescu DV, Rapoport A, Suleiman R. Resource dilemmas with environmental uncertainty and asymmetric players. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1990;20:475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafsson M, Biel A, Gärling T. Overharvesting of resources of unknown size. Acta Psychol (Amst.) 1999;103:47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Kwaadsteniet EW, van Dijk E, Wit A, De Cremer D, de Rooij M. Justifying Decisions in Social Dilemmas: Justification Pressures and Tacit Coordination Under Environmental Uncertainty. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:1648–1660. doi: 10.1177/0146167207307490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shalvi S, Gino F, Barkan R, Ayal S. Self-Serving Justifications Doing Wrong and Feeling Moral. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2015;24:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagel T. What Is It Like to Be a Bat? Philos Rev. 1974;83:435–450. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harsanyi JC. Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. J Polit Econ. 1955;63:309–321. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond PJ. Interpersonal comparisons of utility: Why and how they are and should be made. Interpers Comp Well-Being. 1991:200–254. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falk A, Tirole J. Narratives, imperatives and moral reasoning. mimeo Toulouse School of Economics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D. The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance. J Mark Res. 2008;45:633–644. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haisley EC, Weber RA. Self-serving interpretations of ambiguity in other-regarding behavior. Games Econ Behav. 2010;68:614–625. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dijk E, Wit A, Wilke H, Budescu DV. What we know (and do not know) about the effects of uncertainty on behavior in social dilemmas. Contemp Psychol Res Soc Dilemmas. 2004:315–331. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krupka EL, Weber RA. Identifying social norms using coordination games: Why does dictator game sharing vary? J Eur Econ Assoc. 2013;11:495–524. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platt ML, Huettel SA. Risky business: the neuroeconomics of decision making under uncertainty. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:398. doi: 10.1038/nn2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage LJ. The foundations of statistics. Dover Publications; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckholtz JW, et al. From blame to punishment: disrupting prefrontal cortex activity reveals norm enforcement mechanisms. Neuron. 2015;87:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis HL, Hoch SJ, Ragsdale EKE. An Anchoring and Adjustment Model of Spousal Predictions. J Consum Res. 1986;13:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenstein MJ, Xu X. My Mug Is Valuable, But My Partner’s Is Even More So: Economic Decisions for Close Others. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2015;37:174–187. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsee CK, Weber EU. A fundamental prediction error: Self–others discrepancies in risk preference. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1997;126:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziegler FV, Tunney RJ. Who’s been framed? Framing effects are reduced in financial gambles made for others. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:9. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson O, Holm HJ, Tyran J-R, Wengström E. Risking other people’s money: Experimental evidence on bonus schemes, competition, and altruism. 2013 IFN Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beisswanger AH, Stone ER, Hupp JM, Allgaier L. Risk taking in relationships: Differences in deciding for oneself versus for a friend. Basic Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;25:121–135. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Sarr B, Fagerlin A, Ubel PA. A matter of perspective: choosing for others differs from choosing for yourself in making treatment decisions. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:618–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green JD, Burnette JL, Davis JL. Third-party forgiveness: (not) forgiving your close other’s betrayer. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008;34:407–418. doi: 10.1177/0146167207311534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:493–497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly B, Rid A, Wendler D. Systematic review: Individuals’ goals for surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:884–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, White DB. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2281–2286. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182533317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crockett MJ, Kurth-Nelson Z, Siegel JZ, Dayan P, Dolan RJ. Harm to others outweighs harm to self in moral decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:17320–17325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408988111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engel C. Dictator games: a meta study. Exp Econ. 2011;14:583–610. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartling B, Fischbacher U. Shifting the Blame: On Delegation and Responsibility. Rev Econ Stud. 2011 doi: 10.1093/restud/rdr023. rdr023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguiar F, Brañas-Garza P, Miller LM. Moral distance in dictator games. Judgm Decis Mak. 2008;3:344. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brañas-Garza P. Poverty in dictator games: Awakening solidarity. J Econ Behav Organ. 2006;60:306–320. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fong C, Oberholzer-Gee F. Truth in giving: Experimental evidence on the welfare effects of informed giving to the poor. J Public Econ. 2011;95:436–444. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reniers RLEP, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane NM, Völlm BA. The QCAE: a Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. J Pers Assess. 2011;93:84–95. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.528484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossmann I, Brienza JP, Bobocel DR. Wise deliberation sustains cooperation. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1 s41562-017-0061-017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kogut T, Ritov I. The“ Identified Victim” Effect: An Identified Group, or Just a Single Individual? J Behav Decis Mak. 2005;18:157. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Small DA, Loewenstein G. Helping a Victim or Helping the Victim: Altruism and Identifiability. J Risk Uncertain. 2003;26:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Small DA, Loewenstein G, Slovic P. Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought on donations to identifiable and statistical victims. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2007;102:143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ecker UKH, Hogan JL, Lewandowsky S. Reminders and Repetition of Misinformation: Helping or Hindering Its Retraction? J Appl Res Mem Cogn. 2017;6:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putnam AL, Wahlheim CN, Jacoby LL. Memory for flip-flopping: detection and recollection of political contradictions. Mem Cognit. 2014;42:1198–1210. doi: 10.3758/s13421-014-0419-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stadtler M, Scharrer L, Brummernhenrich B, Bromme R. Dealing With Uncertainty: Readers’ Memory for and Use of Conflicting Information From Science Texts as Function of Presentation Format and Source Expertise. Cogn Instr. 2013;31:130–150. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brock JM, Lange A, Ozbay EY. Dictating the Risk: Experimental Evidence on Giving in Risky Environments. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103:415–437. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quora. What Are the Chances of a Devastating Pandemic Occurring in the Next 50 Years? Huffington Post. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paolacci G, Chandler J, Ipeirotis PG. Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgm Decis Mak. 2010;5:411–419. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips J, Cushman F. Morality constrains the default representation of what is possible. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:4649–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619717114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.