Abstract

The influence of dose rate on radiation cataractogenesis has yet to be extensively studied. One recent epidemiological investigation suggested that protracted radiation exposure increases radiation-induced cataract risk: cumulative doses of radiation mostly <100 mGy received by US radiologic technologists over 5 years were associated with an increased excess hazard ratio for cataract development. However, there are few mechanistic studies to support and explain such observations. Low-dose radiation-induced DNA damage in the epithelial cells of the eye lens (LECs) has been proposed as a possible contributor to cataract formation and thus visual impairment. Here, 53BP1 foci was used as a marker of DNA damage. Unexpectedly, the number of 53BP1 foci that persisted in the mouse lens samples after γ-radiation exposure increased with decreasing dose-rate at 4 and 24 h. The C57BL/6 mice were exposed to 0.5, 1 and 2 Gy ƴ-radiation at 0.063 and 0.3 Gy/min and also 0.5 Gy at 0.014 Gy/min. This contrasts the data we obtained for peripheral blood lymphocytes collected from the same animal groups, which showed the expected reduction of residual 53BP1 foci with reducing dose-rate. These findings highlight the likely importance of dose-rate in low-dose cataract formation and, furthermore, represent the first evidence that LECs process radiation damage differently to blood lymphocytes.

Subject terms: Mechanisms of disease, Animal disease models, Occupational health

Introduction

Since the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) recommended a reduction in the eye lens occupational dose limit for ionising radiation (IR) exposure in 20121 there has been a need for reliable mechanistic evidence to underpin the recommendations and subsequent changes in the IAEA and EU Basic Safety Standards which recently came into force2. Epidemiological studies supported the implementation of reduced dose limits1,3,4, however, the biological response of the lens and the mechanism(s) leading to IR-induced cataract remain unclear5,6. Historically, the focus of IR-induced cataract research has been on the effect of dose and threshold, to help decide whether cataract induction is most appropriately considered to be stochastic or deterministic (a ‘tissue effect’) in nature6,7. The effects of chronic, fractionated or protracted exposures remain unclear8, but recognition that the eye lens may be more radiosensitive than previously thought suggests there could be tissue-specific effects worthy of consideration, particularly in the contexts of medical and occupational exposures3.

Historically, dose rate has been considered in only a very few studies looking at cataract risk in IR exposed populations. A very recently published epidemiological study, by Little et al.9, has suggested an excess hazard ratio of 0.69 (0.27–1.16) per Gy of IR to the formation of cataract in radiologic technologists following cumulative occupational exposures to low doses (mostly < 100 mGy) accumulated over an average 5-year lagged eye lens absorbed dose9 (using self-reported cataract history as an endpoint). This excess hazard ratio was significantly different from the lowest dose exposure cases (<10 mGy cumulative exposure) used as a control group. Similar excess relative risk of 0.91 (0.67–1.20) has also been demonstrated to increase linearly during protracted exposures to ≥ 250 mGy from an analysis of the Mayak worker cohort10,11. Excess hazard ratios are difficult to compare between epidemiological studies due to a variety of factors including varying models and parameters. Nevertheless the authors found that the observed risks were statistically similar to those reported on the Japanese atomic bomb survivor cohort after reanalysis that estimated a lower excess hazard ratio of 0.32 (0.17–0.52) was reported12. However, the Little et al.9 study invovled a relatively large cohort of over 12,000 cases, alongside well characterised dosimetry – a key consideration for effective IR epidemiology5,13. Whilst there is little biological evidence for a dose-rate influence in the lens to date, it has been suggested as potentially having a large impact, particularly when doses are fractionated14. Thelatest epidemiological finding9 supports this suggestion, although the ICRP do not draw conclusions regarding the effect of dose-rate on the lens due to a current lack of sufficient evidence1,15.

The mechanism(s) of IR-induced cataract are still largely unknown, however, several possible mechanisms have been identified suggesting that a combination of processes likely play contributory roles5. The mouse is a highly appropriate in-vivo tool for such investigations on the eye lens for both early, short term biological effects16–18, as well as longer term studies of cataract formation18–23. LECs are organised as a single cell monolayer covering the anterior surface of the lens, where they are critical to lens function24. The epithelium can be spatially defined into two distinct regions, the central and peripheral regions; the latter consists of cells with a proliferative ability but not necessarily actively cycling25,26. The role of DNA damage and its potential impact on cataractogenesis in the lens is documented16–18,22,27,28. Notable examples include; cataractous lenses showing a high frequency of single strand breaks28, base and nucleotide excision repair genes having a suggested role in cataractogenesis29 and mutated Xpd/Ercc2 genes (involved in DNA repair) result in sensitivity to IR18. Lens epithelial cells appear to employ both non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination to repair DNA damage, observed in the dose responses of both 53BP1 and Rad51 for both pathways respectively17. Haploinsufficiency for Atm and also Rad9 have been demonstrated to increase the radiosensitivity of the lens22,30.

IR-induced DNA double strand break (DSB) formation and repair can be quantified using a number of protein biomarkers, most commonly ƴ-H2AX, Rad51 or 53BP131–33. IR-induced DNA damage assessed by ƴ H2AX and 53BP1 foci quantification in LECs of exposed lenses demonstrated a clear response at a range of doses16,17.

The dose rate at which IR is delivered is influential in the repair of DSBs. Low-LET IR is generally considered to be less effective when administered over a longer period, as opposed to an acute delivery, i.e. within minutes34. For decades it has been well understood that, certainly for low LET x- and ƴ-IR, a lowering of dose rate and extension of exposure time reduces the biological effect of a given dose particularly in cellular experiments35, and decreasing dose rate generally correlates to a decrease in the number of detectable un-repaired DSBs post-exposure36. Low dose rate is typically defined as being 5 mGy/hr or lower37. Results from studies using ƴ-H2AX demonstrate lower frequencies of residual DSB induced with lower dose rates in lymphocytes38,39. The study of Turner et al.38 compared two dose rates (1.03 Gy/min and 0.31 mGy/min), of x-irradiation and subsequent ƴ-H2AX foci yields in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of C57BL/6 mice. At 24 h post irradiation, the acute dose rate produced a significantly higher frequency of unrepaired damage in the lymphocytes from mice exposed to 1.1 and 2.2 Gy.

In this study, we explore the effect of varying dose-rates on residual 53BP1 foci in the lens of the eye following in-vivo exposure of female C57BL/6 mice. This strain is a reproducible mammalian model for investigating DNA damage and repair in the lens epithelium16. Adult mice 10 weeks of age were exposed27 and the effect of varying dose rates in LECs was measured using 53BP1 as a marker for IR-induced DNA DSB and repair. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were also collected from the same mice and analysed in parallel with the same marker to determine the comparative lens sensitivity to DNA damage resulting from three dose rates of IR exposure.

Methods

A total of 78 female C57BL/6 (C57BL/6JOla/Hsd, Envigo RMS (UK) Ltd., Blackthorn, Bicester, Oxfordshire OX25 1TP) mice (142 lenses – 2 lenses omitted) were whole body exposed to IR at 10 weeks of age. Mice were exposed in groups of four for each dose, time and dose rate data point. Four mice (8 lenses) were used for each dose, time and dose-rate, with two mice for each point as controls (4 lenses), as per power calculations and previous observations on the reproducibility of this strain of mice16. Control mice were sham exposed, being transported to the exposure facility alongside the complimenting exposed mice. Six lenses were of insufficient quality to be analysed effectively. An additional 3 mice (6 lenses) were used for the 0.014 Gy/min exposures at 0.5 Gy. All procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 via approved project licencing granted by the UK Home Office, with additional approval from the local Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB) at Public Health England.

The exposures took place at the Medical Research Council Co-60 gamma irradiation facility (Harwell Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK)40, with a horizontal geometry. Doses of 0.5, 1 and 2 Gy were delivered at dose rates of 0.3, 0.063 and 0.014 Gy/min (Table 1). The irradiation system is calibrated and traceable to national standards. All doses were delivered to within 5% accuracy. Irradiations took place at room temperature, with whole body in-vivo exposure. A combination of 1, 2 or 4 cobalt-60 sources were used to achieve dose rates of 0.014, 0.063 and 0.3 Gy/min respectively.

Table 1.

Table of exposure time for each scenario, matched to the date of exposure and source decay factor for that given time.

| Dose (Gy) | 300 mGy/min | 63 mGy/min | 14 mGy/min |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1.5 min | 7.1 min | 39 min |

| 1.0 | 3.1 min | 14.4 min | N/A |

| 2.0 | 6.3 min | 29.2 min | N/A |

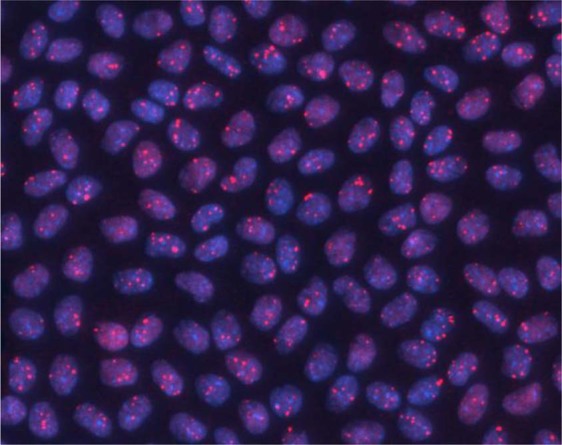

Mice were sacrificed at 4 and 24 h post-exposure (from start of irradiation) and eyes fixed in formaldehyde. The techniques and methodologies for LEC preparation, isolation and immunofluorescence employed during this study have been described previously16 and were used in the current study, unless stated otherwise. Lens epithelia were isolated and immunofluorescence stained (Fig. 1) as described for 53BP116. A minimum of 200 and 350 cells were scored for the central and peripheral regions, respectively per data point. From these initial data, power and sample size testing was carried out, based on a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8 to ensure foci were scored in a large enough number of cells for comparative statistics to be applied16.

Figure 1.

53BP1 foci in the nuclei of LEC located in the central region of the monolayer following 2 Gy irradiation (0.063 Gy/min) fixed and stained 4 h post-exposure.

In addition to the lens epithelium, peripheral blood lymphocytes were also analysed from the same animals. Upon sacrifice, peripheral whole blood was extracted by cardiac puncture. This blood was placed on ice briefly to halt repair. The protocol used for lymphocyte extraction, fixation and immunofluorescent staining followed is described in previous publications32,41. Histopaque-1083 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was used to isolate murine lymphocytes. A minimum of 200 nuclei were analysed for each of the peripheral lymphocyte samples using manual scoring.

Statistical analysis was performed using Minitab 17. General Linear Model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to all data including dose, dose rate, epithelial region and time post exposure as factors. For the lens epithelial cell data, second and third order interactions for the variables dose, dose rate and time were explored to explain a relatively large lack of fit evident without this interaction. For dose and dose rate, plus the second order interaction between dose and time and the third order interaction between dose, dose rate and time, Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparison between the different levels of these factors was then applied.

Results

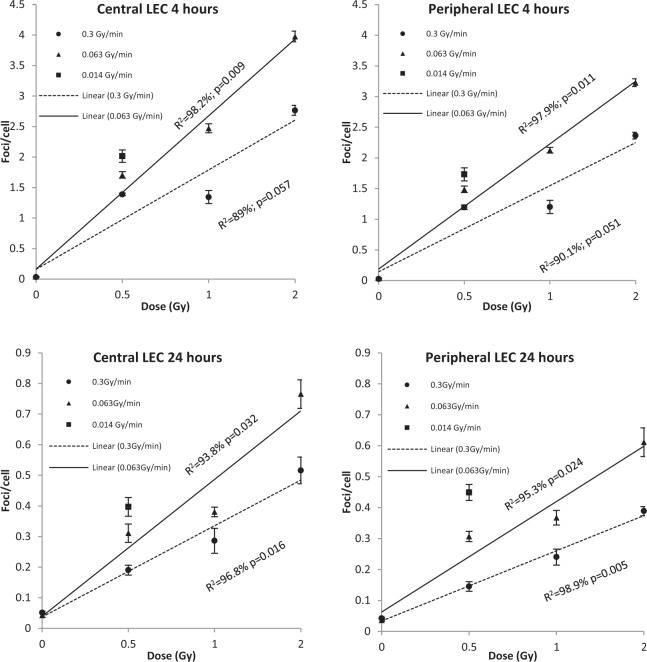

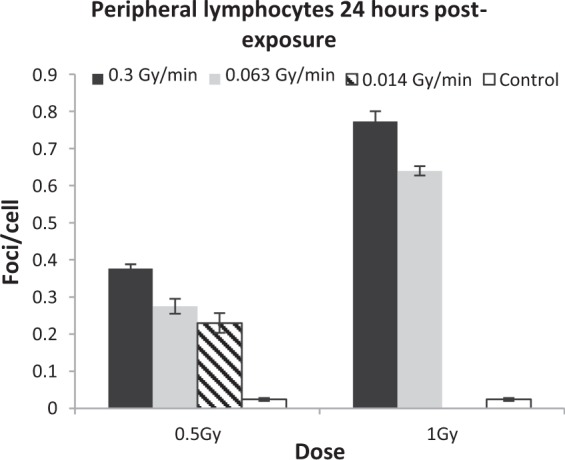

No significant effect of time, region, dose or dose rate in the sham-exposed control mice was observed. Analysis of the peripheral blood lymphocyte samples was performed firstly to compare with LECs, but secondly to confirm the dose rate effects seen in previous mouse studies38. Residual 53BP1 foci were scored at 24 h post-exposure for both 0.5 and 1 Gy doses at both 0.3 and 0.063 Gy/min dose rates and plotted with standard error (SE) bars (Fig. 2). All post-irradiation samples had more foci than unirradiated controls (p ≤ 0.001). At 0.5 Gy, the higher dose rate shows 0.376 (±0.011) mean foci/cell compared to 0.275 (±0.020) from the lower dose rate. At 1 Gy, the higher dose rate shows 0.773 (±0.027) foci/cell compared to 0.64 (±0.012) seen for the lower dose rate. Figure 2 demonstrates an even lower frequency of mean foci/cell (0.23 ± 0.026) at 0.5 Gy, delivered at 0.014 Gy/min, compared to both the 0.3 and 0.063 Gy/min dose rate exposures for 0.5 Gy. ANOVA reveals a significant influence of both dose and dose rate (p ≤ 0.001) on 53BP1 foci in lymphocytes.53BP1 foci were evaluated in the LECs of the central and peripheral regions, as in previous studies16,17. Mean foci frequencies were analysed at 4 and 24 h following exposure to doses of 0.5, 1 and 2 Gy irradiation at 0.3 and 0.063 Gy/min Co-60 ƴ-IR (Fig. 3). A reduction of mean foci/cell frequencies is seen at all doses between 4 to 24 h suggesting effective repair of DSBs. Doses delivered at 0.3 Gy/min yield fewer detectable foci than at 0.063 Gy/min in LECs. As mentioned, we included a lower dose rate of 0.014 Gy/min but were limited to only one dose, 0.5 Gy, due to mouse exposure time constraints. Figure 3 compares all three dose rates (0.014, 0.063 and 0.3 Gy/min) delivering a dose of 0.5 Gy in-vivo. The further reduction of dose rate (0.014 Gy/min) further increases detectable mean foci/cell frequencies in both regions at both 4 and 24 h post-exposure.

Figure 2.

Mean 53BP1 foci/cell (including stand error bars) 24 h post-exposure to IR delivered with three different dose rates, measured in peripheral blood lymphocytes from in-vivo irradiated female C57BL/6 mice. As discussed in the main text, 0.014 Gy/min data is presented for 0.5 Gy only.

Figure 3.

Mean 53BP1 foci/cell within central and peripheral region LEC (LEC) both 4 and 24 h post-irradiation to 0.5, 1 and 2 Gy (plus control) Co-60 ƴ-radiation at 0.3, 0.063 and 0.014 (0.5 Gy dose only as discussed) Gy/min dose rates. Note mean foci/cell axis is to a different scale at 24 h post-exposure compared to 4 h for ease of reading.

For statistical analysis, a variety of General Linear ANOVA Models were applied and finally a non-hierarchical model with a third order interaction for the variables dose, dose rate and time was used as this gave the best fit overall. Dose, dose rate and time were all found to significantly affect residual foci/cell yields (p ≤ 0.001), and the interaction between dose, dose rate and time was also significant (p < 0.001), indicating that DNA damage results must be considered in the context of dose, dose-rate and time post-exposure. Only the region of the epithelium ie peripheral versus central was not significant (p = 0.079), although significantly different residual foci yields were observed between regions previously at lower total doses and for X-ray rather than γ-ray exposures16. Tukey’s test then revealed that all doses were significantly different from each other, apart from 0.5 and 1 Gy (p = 0.339). For all doses, the intermediate dose rate of 0.063 Gy/min shows a significantly higher frequency of mean foci/cell compared to the higher dose rate of 0.3 Gy/min (p = 0.001) and at 0.5 Gy the residual foci yields at the lower dose rate of 0.014 Gy/min was significantly different from those at 0.3 Gy/min (p = 0.014). There was no significant difference between the two lower dose rates (p = 0.696) at 0.5 Gy 24 h after exposure.

Discussion

The observed inverse dose-rate effect in LEC is evident in both 4 and 24-hour post-exposure data. The limited biological evidence of an inverse dose rate effect in the lens has recently been summarised by Hamada et al.14, suggesting there might be a dose-rate effect at low-LET exposures. Moreover this inverse dose-rate effect would only observed with high-LET neutron radiation42. It should also be noted that standard errors associated with mean foci/cell are small, a previously observed characteristic of both the radiosensitive Balb/c and the less sensitive C57BL/6 strains16. Further, post hoc testing demonstrates a clear trend of higher foci numbers with higher doses, shorter times and, to some extent, lower dose rates. Dose rate reduction, and increased duration of exposure generally reduce the biological effects of ionising radiation35 as observed in the lymphocytes of both this study and in Turner et al.38, where less DNA damage foci were detected.

The somewhat unexpected finding of this study may be explained when considering the interaction effects. This additional feature of the observed data is the significant interaction effect, i.e., the statistically significant interaction between time (post-exposure), dose and dose-rate, as well as between dose and time, both with p-values of < 0.001. Such an interaction is not something commonly considered during such analyses, but the results here are clear. This analysis was justified due to the large error observed within the sum of squares from ANOVA testing, when the interaction effect was not included. Dose, dose rate and time are biologically known to have interactions and indeed it appears from out data that 53BP1 foci frequencies are influenced by all three.

The dose rates used in this study are not low in comparison to the generally accepted definition of <5 mGy/h43, below which single track events will predominate. The choice of dose rates in this study was driven chiefly by the availability of suitable exposure facilities and the dose and dose rate ranges within which the source could be reliably calibrated. However, the data presented here support the hypothesis8,9 that there is a dose rate effect in the lens and not in the lymphocytes. Reducing dose rate from 0.3 to 0.063 Gy/min was found to significantly increase the number of detectable residual DSBs within LEC DNA, which raises the question of the effects of protracted low dose-rate exposures on the lens. More investigations are required to establish the influence of both IR dose-rate and also energy on the DNA damage response of LECs.

Whilst this study considers one response to IR exposure, i.e. DNA damage assessed by 53BP1 foci, recent findings suggest it has a role in IR-induced cataractogenesis16–18. Based on the dose responses seen for both Rad51 and 53BP1 foci in a previous study, both homologous recombination and non-homologous end joining repair mechanisms, respectively, appear to be active in LECs17. it has been suggested that a combination of IR-induced effects is responsible for cataract induction5,44 and our data support this view. Un-repaired DNA damage in LEC could lead to altered cell proliferation17, which could in turn have a detrimental effect on cell differentiation. Our data also suggest that gamma-ray IR induced damage may accumulate as evidenced by the persistence of foci 24 h after exposure across the lens epithelium (Fig. 3). The presence of progenitor cells in the lens epithelium45–47 would potentially pose a particularly sensitive target for IR-induced DNA damage. Another possible mechanistic explanation for the results of this study could relate to the roles of lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) and eyes absent (EYA) proteins. LEDGF is expressed in greater concentration across the central region of the lens epithelium48, where it has been shown to protect the cells against oxidative damage49 and DNA damage induced via peroxide and UVB50,51. The expression of LEDGF is lost towards the equator of the lens, where the peripheral region LECs are located48 resulting in slower repair. This is important to our study as LEDGF has DNA binding properties52 and is involved in the DNA DSB repair response pathway following γ-radiation exposure53. Recent proteomic and RNA sequencing data have revealed, higher levels of DNA repair proteins 53BP1, MRE11 and Rad50 in the murine lens epithelium compared to fibre cells54, but the fact that the peripheral epithelium is more sensitive to IR17 suggests that LEDGF might play a key role in this differential sensitivity between the central and peripheral regions of LECs. EYA, a phosphatase required along with Pax6 and Six3 transcription factors that are essential for eye development55, is also needed for DNA repair as it dephosphorylates H2AX56. Both LEDGF49,57 and EYA58 are also required for LEC differentiation into LFCs. Our data indicate that DNA repair is dependent upon dose and dose rate. We interpret this to indicate that peripheral LEC are balancing the processes of differentiation and DNA DSB repair. At the low dose rates, the 53BP1 foci persist whilst differentiation proceeds, but at higher dose rates, DNA repair is favoured over differentiation. The decreased expression of LEDGF in the peripheral region LEC could help explain the slower repair of DNA damage seen in our study at the lower dose rate (Fig. 3). The 53BP1 foci indicates that DNA repair is progressing, as we also observe a decrease in foci/cell with time for both peripheral and central regions of the lens epithelium.

Inverse dose-rate effects generally occur in instances whereby a continuous low dose rate exposure to IR allows cells to cycle, then hitting a G2-phase block, resulting in cell death35. However, cell death does occur in LECs but this is very low, and there are no reported instances of increased LEC death post-IR exposure5. Lifetime loss of LEC via cell death in humans over many decades may have some effect on LEC differentiation and lens transparency59. One proposed mechanism of the inverse dose-rate effect is a failure of LECs to arrest damaged cells and halt their progression into G2 cell cycle phase. This would make the periphery a particular target of the inverse dose-rate effect14 as it is here that proliferating cells are concentrated60. A consequence of delaying DSB repair is that secondary effects accrue and affect lens cell differentiation itself6,14. This is broadly summarised in the ‘cataractogenic load’ concept, where genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors are recognised as con-inducers of age-related cataract44. IR-induced damage therefore compounds the lens aging process by further increasing this ‘load’ to accelerate aging and the appearance of age-related cataract. Our report here of an inverse dose rate effect fuels further debate on IR effects upon the lens and strengthens arguments for regular monitoring in occupational contexts3,61,62.

Conclusion

This study represents the first in-vivo experimental investigation of dose-rate effects in the epithelial cells of the mouse eye lens and presents the first evidence to suggest that LEC and lymphocytes respond differently to dose-rate variation in terms of DNA damage repair. Levels of residual DNA damage foci observed in LECs increase with reduced dose-rate unlike in peripheral lymphocytes from the same animals. This supports the hypothesis that the lens has an unusual DNA damage response to IR compared to other tissues. Our data indicate an inverse dose rate effect in the LEC for residual 53BP1 foci as a marker for DSBs, and it is hypothesised that this residual damage contributes to cataractogenesis. This study evidences the importance of determining the cell-specific effects of low dose and low dose-rate IR exposures on DNA repair in target tissues and show that the response can be cell and tissue specific due to for instance, competing processes such as cell proliferation and differentiation in a dose-rate dependant manner as observed in cell-based studies63–65.

Ethical approval and informed consent

All experimental protocols were approved by the UK Home Office and approved under project licencing, as well as local Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body. Methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guideline and regulations stated above.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the LDLensRad consortium (https://www.researchgate.net/project/LDLensRad-the-European-CONCERT-project-starting-in-2017-Towards-a-full-mechanistic-understanding-of-low-dose-radiation-induced-cataracts). We would also like to thank Mark Hill and James Thompson from the Oxford Institute for Radiation Oncology and Bob Sokolowski of MRC Harwell for support with the irradiation facility. We also thank Simon Bouffler of Public Health England for continued support and guidance with this study. LDLensRad has received funding from the Euratom research and training programme 2014-2018 in the framework of hte CONCERT [grant agreement No. 662287]. This publication reflects the author’s view. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the authors. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contrains.

Author Contributions

S.B., R.Q., and E.A. designed and conceived the original idea. S.B. wrote the manuscript with support from R.M., J.M., R.Q. and E.A. The experiments and analysis were performed by S.B., R.M. and J.M.

Data Availability

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Stephen G. R. Barnard, Email: Stephen.barnard@phe.gov.uk

Roy Quinlan, Email: r.a.quinlan@durham.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Stewart FA, et al. ICRP publication 118: ICRP statement on tissue reactions and early and late effects of radiation in normal tissues and organs–threshold doses for tissue reactions in a radiation protection context. Ann ICRP. 2012;41:1–322. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouffler SD, et al. The lens of the eye: exposures in the UK medical sector and mechanistic studies of radiation effects. Ann ICRP. 2015;44:84–90. doi: 10.1177/0146645314560693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard SG, Ainsbury EA, Quinlan RA, Bouffler SD. Radiation protection of the eye lens in medical workers-basis and impact of the ICRP recommendations. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20151034. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20151034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauer Lawrence T., Ainsbury Elizabeth A., Dynlacht Joseph, Hoel David, Klein Barbara E. K., Mayer Donald, Prescott Christina R., Thornton Raymond H., Vano Eliseo, Woloschak Gayle E., Flannery Cynthia M., Goldstein Lee E., Hamada Nobuyuki, Tran Phung K., Grissom Michael P., Blakely Eleanor A. Guidance on radiation dose limits for the lens of the eye: overview of the recommendations in NCRP Commentary No. 26. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2017;93(10):1015–1023. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2017.1304669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ainsbury EA, et al. Ionizing radiation induced cataracts: Recent biological and mechanistic developments and perspectives for future research. Mutat Res. 2016;770:238–261. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamada N, et al. Emerging issues in radiogenic cataracts and cardiovascular disease. J Radiat Res. 2014;55:831–846. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rru036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer GP, et al. Occupational exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation and cataract development: a systematic literature review and perspectives on future studies. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52:303–319. doi: 10.1007/s00411-013-0477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamada N. Ionizing radiation sensitivity of the ocular lens and its dose rate dependence. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017;93:1024–1034. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2016.1266407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little MP, et al. Occupational radiation exposure and risk of cataract incidence in a cohort of US radiologic technologists. European journal of epidemiology. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azizova TV, Bragin EV, Hamada N, Bannikova MV. Risk of Cataract Incidence in a Cohort of Mayak PA Workers following Chronic Occupational Radiation Exposure. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizova TV, Hamada N, Grigoryeva ES, Bragin EV. Risk of various types of cataracts in a cohort of Mayak workers following chronic occupational exposure to ionizing radiation. European journal of epidemiology. 2018;33:1193–1204. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neriishi K, et al. Radiation dose and cataract surgery incidence in atomic bomb survivors, 1986-2005. Radiology. 2012;265:167–174. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainsbury EA, et al. Radiation cataractogenesis: a review of recent studies. Radiat Res. 2009;172:1–9. doi: 10.1667/rr1688.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamada, N. Ionizing radiation sensitivity of the ocular lens and its dose rate dependence. Int J Radiat Biol, 1–11, 10.1080/09553002.2016.1266407 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hamada N. Ionizing radiation response of primary normal human lens epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnard, S. G. R. et al. Dotting the eyes: mouse strain dependency of the lens epithelium to low dose radiation-induced DNA damage. Int J Radiat Biol, 1–9, 10.1080/09553002.2018.1532609 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Markiewicz E, et al. Nonlinear ionizing radiation-induced changes in eye lens cell proliferation, cyclin D1 expression and lens shape. Open biology. 2015;5:150011. doi: 10.1098/rsob.150011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunze S, et al. New mutation in the mouse Xpd/Ercc2 gene leads to recessive cataracts. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalke C, et al. Lifetime study in mice after acute low-dose ionizing radiation: a multifactorial study with special focus on cataract risk. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2018;57:99–113. doi: 10.1007/s00411-017-0728-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakthavachalu B, et al. Dense cataract and microphthalmia (dcm) in BALB/c mice is caused by mutations in the GJA8 locus. Journal of genetics. 2010;89:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s12041-010-0054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Stefano I, et al. The Patched 1 tumor-suppressor gene protects the mouse lens from spontaneous and radiation-induced cataract. The American journal of pathology. 2015;185:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleiman NJ, et al. Mrad9 and atm haploinsufficiency enhance spontaneous and X-ray-induced cataractogenesis in mice. Radiat Res. 2007;168:567–573. doi: 10.1667/rr1122.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohale K, Ingle A, Kelkar A, Parab P. Dense cataract and microphthalmia–new spontaneous mutation in BALB/c mice. Comparative medicine. 2004;54:275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wormstone IM, Wride MA. The ocular lens: a classic model for development, physiology and disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:1190–1192. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tholozan FM, Quinlan RA. Lens cells: more than meets the eye. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1754–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Treton JA, Courtois Y. Evolution of the distribution, proliferation and ultraviolet repair capacity of rat lens epithelial cells as a function of maturation and aging. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 1981;15:251–267. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(81)90134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannik K, et al. Are mouse lens epithelial cells more sensitive to gamma-irradiation than lymphocytes? Radiat Environ Biophys. 2013;52:279–286. doi: 10.1007/s00411-012-0451-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleiman NJ, Spector A. DNA single strand breaks in human lens epithelial cells from patients with cataract. Current eye research. 1993;12:423–431. doi: 10.3109/02713689309024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimichi Y, Hamada N. Ionizing irradiation not only inactivates clonogenic potential in primary normal human diploid lens epithelial cells but also stimulates cell proliferation in a subset of this population. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Worgul BV, Smilenov L, Brenner DJ, Vazquez M, Hall EJ. Mice heterozygous for the ATM gene are more sensitive to both X-ray and heavy ion exposure than are wildtypes. Advances in space research: the official journal of the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) 2005;35:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chua ML, Rothkamm K. Biomarkers of radiation exposure: can they predict normal tissue radiosensitivity? Clinical oncology (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)) 2013;25:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horn S, Barnard S, Brady D, Prise KM, Rothkamm K. Combined analysis of gamma-H2AX/53BP1 foci and caspase activation in lymphocyte subsets detects recent and more remote radiation exposures. Radiat Res. 2013;180:603–609. doi: 10.1667/rr13342.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothkamm K, et al. DNA damage foci: Meaning and significance. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2015;56:491–504. doi: 10.1002/em.21944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall EJ, Brenner DJ. The dose-rate effect revisited: radiobiological considerations of importance in radiotherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1991;21:1403–1414. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90314-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall, E. J. Radiobiology for the radiologist. (Hagerstown, Md.: Medical Dept., Harper & Row, [1973] ©1973, 1973).

- 36.Ruiz de Almodovar JM, et al. Dose-rate effect for DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation in human tumor cells. Radiat Res. 1994;138:S93–96. doi: 10.2307/3578771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ICRP. ICRP Publication 103. Annals of the ICRP37 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Turner HC, et al. Effect of dose rate on residual gamma-H2AX levels and frequency of micronuclei in X-irradiated mouse lymphocytes. Radiat Res. 2015;183:315–324. doi: 10.1667/rr13860.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato TA, Nagasawa H, Weil MM, Little JB, Bedford JS. Levels of gamma-H2AX Foci after low-dose-rate irradiation reveal a DNA DSB rejoining defect in cells from human ATM heterozygotes in two at families and in another apparently normal individual. Radiat Res. 2006;166:443–453. doi: 10.1667/rr3604.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ainsbury E, et al. Integration of new biological and physical retrospective dosimetry methods into EU emergency response plans - joint RENEB and EURADOS inter-laboratory comparisons. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017;93:99–109. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2016.1206233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horn S, Barnard S, Rothkamm K. Gamma-H2AX-based dose estimation for whole and partial body radiation exposure. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worgul BV, Brenner DJ, Medvedovsky C, Merriam GR, Jr., Huang Y. Accelerated heavy particles and the lens. VII: The cataractogenic potential of 450 MeV/amu iron ions. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1993;34:184–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ICRP. Early and Late Effects of Radiation in Normal Tissues and Organs – Threshold Doses for Tissue Reactions in a Radiation Protection Context. Annals of the ICRP Publication 103 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Uwineza A, Nobuyuki AAK, Hamada MJ, Quinlan RA. Cataractogenic load – a concept to study the contribution of ionizing radiation to accelerated aging in the eye lens. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2019;779:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin H, et al. Lens regeneration using endogenous stem cells with gain of visual function. Nature. 2016;531:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature17181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oka M, et al. Characterization and localization of side population cells in the lens. Molecular vision. 2010;16:945–953. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou M, Leiberman J, Xu J, Lavker RM. A hierarchy of proliferative cells exists in mouse lens epithelium: implications for lens maintenance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2997–3003. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kubo E, et al. Cellular distribution of lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) in the rat eye: loss of LEDGF from nuclei of differentiating cells. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2003;119:289–299. doi: 10.1007/s00418-003-0518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh DP, Ohguro N, Chylack LT, Jr., Shinohara T. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased resistance to thermal and oxidative stresses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1444–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsui H, Lin LR, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Reddy VN. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor: increased survival and decreased DNA breakage of human RPE cells induced by oxidative stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2935–2941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fatma N, Singh DP, Shinohara T, Chylack LT., Jr. Transcriptional regulation of the antioxidant protein 2 gene, a thiol-specific antioxidant, by lens epithelium-derived growth factor to protect cells from oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48899–48907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh DP, et al. DNA binding domains and nuclear localization signal of LEDGF: contribution of two helix-turn-helix (HTH)-like domains and a stretch of 58 amino acids of the N-terminal to the trans-activation potential of LEDGF. Journal of molecular biology. 2006;355:379–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li L, Wang Y. Cross-talk between the H3K36me3 and H4K16ac histone epigenetic marks in DNA double-strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:11951–11959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.788224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao Y, et al. Proteome-transcriptome analysis and proteome remodeling in mouse lens epithelium and fibers. Exp Eye Res. 2019;179:32–46. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Purcell P, Oliver G, Mardon G, Donner AL, Maas RL. Pax6-dependence of Six3, Eya1 and Dach1 expression during lens and nasal placode induction. Gene expression patterns: GEP. 2005;6:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishnan N, et al. Dephosphorylation of the C-terminal tyrosyl residue of the DNA damage-related histone H2A.X is mediated by the protein phosphatase eyes absent. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16066–16070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900032200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El Ashkar S, et al. LEDGF/p75 is dispensable for hematopoiesis but essential for MLL-rearranged leukemogenesis. Blood. 2018;131:95–107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-786962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu PX, Woo I, Her H, Beier DR, Maas RL. Mouse Eya homologues of the Drosophila eyes absent gene require Pax6 for expression in lens and nasal placode. Development (Cambridge, England) 1997;124:219–231. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Charakidas A, et al. Lens epithelial apoptosis and cell proliferation in human age-related cortical cataract. European journal of ophthalmology. 2005;15:213–220. doi: 10.1177/112067210501500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu JJ, et al. A dimensionless ordered pull-through model of the mammalian lens epithelium evidences scaling across species and explains the age-dependent changes in cell density in the human lens. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 2015;12:20150391. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouffler S, Ainsbury E, Gilvin P, Harrison J. Radiation-induced cataract: the Health Protection Agency’s response to the ICRP statement on tissue reactions and recommendation on the dose limit for the eye lens. Journal of Radiological Protection. 2012;32:479–488. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/32/4/479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ainsbury EA, et al. Public Health England survey of eye lens doses in the UK medical sector. Journal of Radiological Protection. 2014;34:15–29. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/34/1/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Truong K, et al. The effect of well-characterized, very low-dose x-ray radiation on fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rothkamm K, Lobrich M. Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low x-ray doses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5057–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830918100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anglada T, et al. Delayed gammaH2AX foci disappearance in mammary epithelial cells from aged women reveals an age-associated DNA repair defect. Aging. 2019;11:1510–1523. doi: 10.18632/aging.101849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.