Abstract

Introduction

Treatment for TMJ Ankylosis aims at restoring joint function, improving the patient’s aesthetic appearance and quality of life and preventing re-ankylosis. Mouth opening is achieved by gap arthroplasty with various options of interpositional materials. Ramus–condyle unit (RCU) reconstruction maintains the height of the ramus and prevents secondary occlusal problems. Advancement genioplasty corrects chin deformities as well as increases the posterior airway space (N-PAS) by the forward pull exerted on geniohyoid and genioglossus.

Materials and Methods

This prospective single-centre study on 43 joints in 25 adult patients with TMJ Ankylosis aimed at providing a single-staged management plan of ankylosis release, RCU reconstruction and extended advancement centering genioplasty. Interpositional arthroplasty was done using temporalis myofascial flap, abdominal dermis fat or buccal fat pad. RCU reconstruction was done either by vertical ramus osteotomy or L osteotomy.

Observations and Results

Follow-up ranged from 12 to 20 months (mean 14.4). Average mouth opening at maximum follow-up was 34.36 mm with re-ankylosis in no case. Cephalometric parameters showed increase in point P to Pog, decrease in N perpendicular to Pog, angle N–A–Pog, Cg-ANS to Cg-Menton, neck–chin angle and labiomental angle. N-PAS increased, and average 50% improvement in AHI was seen in all patients with OSA. Most common complications involved transient paraesthesia of temporal and zygomatic branches of facial nerve.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the above study, we propose treatment guidelines for treatment of TMJ ankylosis in adult patients with AHI < 20.

Keywords: TMJ Ankylosis, Genioplasty, RCU reconstruction, OSA

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis is characterized by formation of an osseous, fibrous or fibro-osseous mass fused to the base of the skull with ensuing loss of function of the jaw joint [1].

Facial asymmetry is the classical feature in unilateral cases. The chin deviates towards the affected side, with reduction in vertical height of the ramus as well as the formation of a prominent antegonial notch [2]. Bird face deformity is a characteristic feature of bilateral TMJ ankylosis. The oropharyngeal airway is narrowed secondary to shortening of the mandibular rami and narrowing of the space between the mandibular angles, with a resultant mechanical obstruction during respiration, that can lead to the obstructive sleep apnoea and hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) [3].

Treatment of TMJ ankylosis aims at restoring joint function, improving the patient’s aesthetic appearance and quality of life and preventing re-ankylosis [4, 5].

Mouth opening is achieved by gap arthroplasty with various options of interpositional materials. Ramus–condyle unit reconstruction with hard tissue interpositions maintains the height of the ramus and prevents secondary occlusal problems. Advancement genioplasty corrects chin deformities as well as increases the posterior airway space by the forward pull exerted on geniohyoid and genioglossus [6].

Although some surgeons recommend a staged approach for the treatment of patients with TMJ ankylosis and related secondary deformities, others prefer to release the ankylosis and correct the deformities simultaneously [4, 7, 8]. Looking at the issues affecting a patient with TMJ ankylosis, this prospective single-centre study aimed at providing a single-staged management plan for such patients by way of ankylosis release, RCU reconstruction and extended advancement centering genioplasty.

Materials and Methods

The study sample consisted of 43 joints in 25 patients with TMJ ankylosis attending the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Government Dental College and Hospital, Ahmedabad. It included adult patients with TMJ ankylosis and facial asymmetry, with the absence or presence of mild to borderline moderate obstructive sleep apnoea, AHI < 20. Amongst these, 13 patients were female and 12 were male, of age group ranging from 15 to 46 years with 18 bilateral and 7 unilateral ankylosis.

Facial CT scan/CBCT was done to evaluate the ankylotic mass and to measure distance of lingula from posterior and inferior border for osteotomies for RCU reconstruction. Posteroanterior and lateral cephalograms were done to evaluate the required genioplasty and assessment of posterior pharyngeal airway space. Polysomnography was done for Apnoeic–Hypoapnoeic Index.

Awake fibreoptic intubation was regarded as the safest approach for administering anaesthesia here. Tracheostomy was done in cases where it was not possible.

For ankylosis release, pre-auricular incision with a temporal extension was used. After exposing the ankylotic mass, the lower cut was made just below the sigmoid notch from anterior to posterior border of ramus. The upper cut was made at the level of the lower border of the zygomatic arch such that a 1.5 cm gap was created between the cuts.

The elongated coronoid process of the affected side was removed. If intra-operative mouth opening still remained less than 35 mm, contralateral coronoidectomy was performed.

Temporalis myofascial flap, buccal fat pad or abdominal dermis fat graft was randomly used as interpositional material.

For genioplasty, a vestibular incision was placed and extended osteotomy carried out up to below the first molars. Advancement and translational movements of the osteotomized segment were performed as per cephalometric readings. In cases where further augmentation was required, interposition or onlay grafting of autogenous bone was done (derived from ankylotic mass or coronoid process).

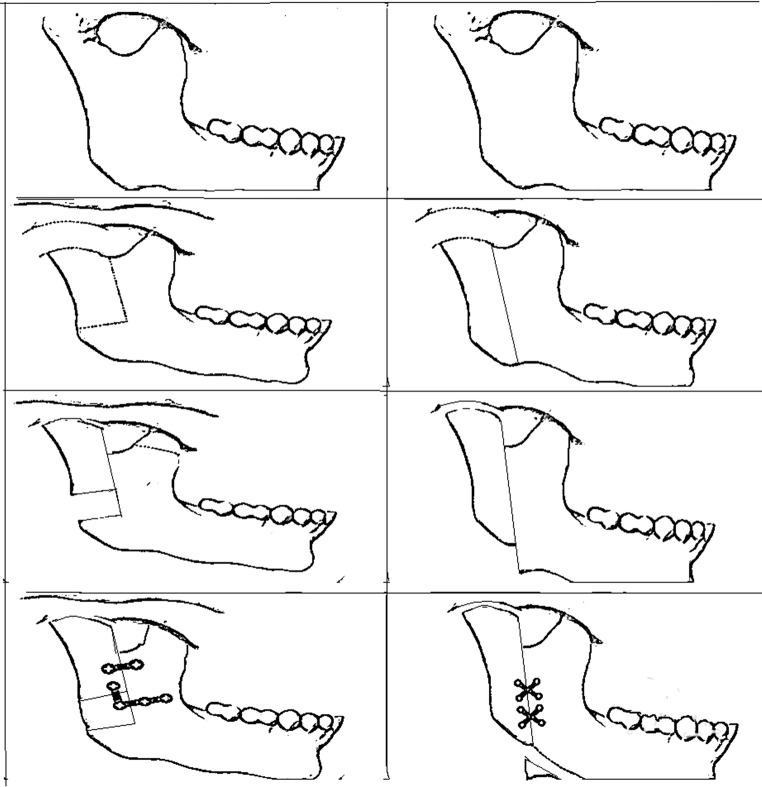

All 43 joints were rehabilitated by RCU reconstruction by either vertical or L-shaped ramus osteotomy [9]. A vertical osteotomy cut was performed on the proximal posterior border of the mandibular ramus 8–10 mm anterior to the posterior border, until 1.0 cm above the angle of the mandible. Then a horizontal osteotomy cut was performed to the posterior border (Fig. 1). This L-shaped segment was pushed up to form the neocondyle. The ipsilateral autogenous coronoid process was reshaped and implanted in the gap between the sliding segment and the angle of the mandible.

Fig. 1.

Clinical pictures: preoperative (above); post operative (below)

In vertical ramus osteotomy, the only difference was that the vertical cut extended all the way down to the inferior border of the mandible and the ramal stump was pushed upwards and plated. Sharp edges at the lower border were smoothened to achieve a flowing margin (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Intra operative pictures: gap arthroplasty (above left), genioplasty (above right), posterior border ramus osteotomy (below)

Results and Observations

Twenty-two out of 25 patients in our study had history of trauma followed by subsequent reduction in mouth opening. Three patients had infection in the vicinity of the ear.

Eighteen patients underwent fibreoptic intubation, and tracheostomy was performed in seven cases.

Follow-up ranged from 12 months to 20 months with mean follow-up period of 14.4 months.

At the time of follow-up, the clinical parameters checked are shown in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1.

Clinical evaluation parameters

| Sr. no. | Age/sex | Mouth opening (mm) | Type of interpositional material used | Prominent antegonial notch | Lower osteotomy cut to highest point of neocondyle (Height of new RCU in mm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-op | Intra-op | Imm Post-op | M/O at maximum follow-up(mm) | Maximum follow-up(months) | Buccal fat pad | Temporalis myofascial flap | Dermal fat | VRO (+) | LRO (-) | Immediate post-op | At maximum follow-up | ||

| 1 | 22/F | 2 | 38 | 31 | 35 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 2 | 18/M | 0 | 35 | 27 | 32 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.6 | 8.4 | |||

| 3 | 23/F | 12 | 37 | 28 | 33 | 17 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 4 | 25/M | 0 | 36 | 26 | 34 | 17 | √ | √ | 8.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 5 | 38/F | 7 | 34 | 29 | 35 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.3 | 8.1 | |||

| 6 | 16/F | 4 | 40 | 32 | 32 | 16 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 7 | 18/M | 3 | 39 | 30 | 36 | 17 | √ | √ | 8.3 | 8 | |||

| 8 | 18/M | 0 | 35 | 27 | 37 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 9 | 46/F | 8 | 36 | 30 | 39 | 17 | √ | √ | 8.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 10 | 15/F | 0 | 37 | 26 | 33 | 16 | √ | √ | 8.6 | 8.2 | |||

| 11 | 16/F | 2 | 39 | 31 | 32 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 12 | 17/M | 0 | 35 | 27 | 32 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.3 | 8 | |||

| 13 | 16/F | 12 | 32 | 28 | 36 | 18 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 14 | 18/M | 0 | 34 | 26 | 35 | 16 | √ | √ | 8.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 15 | 16/F | 7 | 35 | 29 | 37 | 16 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 16 | 24/M | 4 | 40 | 32 | 39 | 16 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 17 | 16/F | 3 | 39 | 30 | 34 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

| 18 | 15/F | 0 | 38 | 27 | 29 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 19 | 23/F | 8 | 41 | 30 | 34 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.2 | |||

| 20 | 14/M | 0 | 31 | 26 | 32 | 20 | √ | √ | 8.3 | 8 | |||

| 21 | 18/M | 2 | 38 | 31 | 34 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.5 | 8.1 | |||

| 22 | 17/F | 0 | 33 | 27 | 33 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.5 | 8.2 | |||

| 23 | 20/M | 12 | 39 | 28 | 36 | 18 | √ | √ | 8.3 | 8 | |||

| 24 | 21/M | 0 | 34 | 26 | 31 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.2 | 8 | |||

| 25 | 23/M | 7 | 38 | 29 | 39 | 12 | √ | √ | 8.4 | 8.1 | |||

Table 2.

Cephalometric evaluation parameters

| Sr. no. | Correction of facial asymmetry | Obstructive sleep apnoea | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N perpendicular to Pog | P–Pog(mm) | Angle between N–A–Pog (°) | Cg-ANS-Me (mm) | Neck–chin angle | Labiomental angle | AHI | PhwN–STBn (mm) | |||||||||||

| Pre-op P1 | Post-op P2 | P2–P1 | Pre-op T1 | Post-op T2 | T2–T1 | Pre-op | F/Up Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | Pre-op | Post-op | |

| 1 | − 24 | − 19 | 5 | 10 | 17 | 7 | 17 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 140 | 130 | 150 | 132 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| 2 | − 28 | − 23 | 5 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 160 | 115 | 156 | 138 | 16 | 5.1 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | − 20 | − 14 | 6 | 9 | 17 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 152 | 120 | 168 | 128 | 3.7 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| 4 | − 27 | − 11 | 16 | 10 | 18 | 8 | 16 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 154 | 112 | 170 | 134 | 15 | 7 | 4 | 7 |

| 5 | − 14 | − 8 | 6 | 9 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 142 | 130 | 171 | 136 | 9.7 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| 6 | − 16 | − 9 | 7 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 144 | 114 | 166 | 132 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| 7 | − 17 | − 12 | 5 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 150 | 120 | 176 | 130 | 19 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| 8 | − 24 | − 17 | 7 | 9 | 17 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 142 | 110 | 168 | 134 | 16.4 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| 9 | − 19 | − 11 | 8 | 10 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 142 | 112 | 162 | 132 | 11 | 3.4 | 6 | 8 |

| 10 | − 23 | − 17 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 13 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 138 | 120 | 167 | 129 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| 11 | − 24 | − 19 | 5 | 11 | 19 | 8 | 17 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 160 | 110 | 170 | 133 | 4.5 | 1.4 | 3 | 6 |

| 12 | − 27 | − 23 | 4 | 10 | 16 | 6 | 27 | 18 | 9 | 2 | 142 | 120 | 171 | 128 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| 13 | − 21 | − 14 | 7 | 9 | 17 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 154 | 130 | 166 | 129 | 15.5 | 5.4 | 3 | 6 |

| 14 | − 26 | − 11 | 15 | 10 | 18 | 8 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 156 | 124 | 176 | 134 | 3 | 2.8 | 4 | 7 |

| 15 | − 25 | − 19 | 6 | 11 | 19 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 148 | 122 | 168 | 136 | 5 | 3.1 | 5 | 8 |

| 16 | − 28 | − 23 | 5 | 13 | 21 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 152 | 116 | 162 | 127 | 12 | 3.4 | 4 | 8 |

| 17 | − 22 | − 14 | 8 | 10 | 17 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 146 | 110 | 167 | 132 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 5 | 7 |

| 18 | − 26 | − 11 | 15 | 11 | 18 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 160 | 114 | 170 | 134 | 13.4 | 2 | 6 | 9 |

| 19 | − 15 | − 8 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 158 | 112 | 166 | 130 | 15.3 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 20 | − 17 | − 9 | 8 | 9 | 18 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 147 | 124 | 176 | 132 | 6.8 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 21 | − 16 | − 12 | 4 | 8 | 17 | 9 | 17 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 148 | 114 | 168 | 132 | 8.7 | 4 | 6 | 9 |

| 22 | − 23 | − 17 | 6 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 27 | 18 | 8 | 0 | 156 | 110 | 162 | 126 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 8 |

| 23 | − 18 | − 11 | 7 | 11 | 17 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 143 | 120 | 168 | 129 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| 24 | − 23 | − 17 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 156 | 124 | 162 | 130 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 4 | 8 |

| 25 | − 18 | − 13 | 5 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 146 | 112 | 167 | 132 | 14 | 1.8 | 5 | 9 |

An average mouth opening at maximum follow-up was 34.36 mm, an increase of 30.64 mm from the pre-operative mean mouth opening of 3.72 mm. Re-ankylosis was observed in no case.

Interpositional soft tissue used was temporalis myofascial flap in 20 joints, abdominal dermis fat in 13 and buccal fat pad in 10 joints.

Cephalometrically speaking, average increase in N perpendicular to Pog was 7.16 mm, average increase in point P to Pog was 7.84 mm, angle N–A–Pog (angle of convexity) decreased from average of 14.76° to 7.9°, Cg-ANS to Cg-Menton, signifying the average deviation of chin of 8.16 mm was reduced to 1.32 mm, average decrease in neck–chin angle and labiomental angle achieved was 31.6° and 35.4°, respectively, and in posterior airway space (N-PAS), average increase from 4.44 to 7.36 mm was achieved.

Six had borderline moderate, 12 had mild, and 7 had no pre-operative obstructive sleep apnoea. Average 50% improvement in AHI was seen in all 18 patients who had OSA.

Vertical ramus osteotomy was done in 18 joints which had a prominent antegonial notch. The other 25 joints were rehabilitated by L osteotomy. Height of the newly reconstructed RCU was measured from lower osteotomy cut to highest point of neocondyle. It was an average of 8.4 mm in immediate post-op OPGs and at maximum follow-up was 8.1 mm—an insignificant amount of resorption.

Most common complications involved transient paraesthesia of temporal in 18 and zygomatic branches of facial nerve in 4 cases. All patients underwent facial nerve mapping, and all branches were found to be intact. All cases of paresis resolved within 3–6 months.

Wound dehiscence was observed in one case in the region of genioplasty and another in the pre-auricular incision, which were re-sutured. Excessive intra-operative bleeding occurred in three cases, and other complications such as haematoma, infection, implant failure, avascular necrosis, implant failure or damage to roots of teeth were not observed.

Discussion

TMJ ankylosis occurs primarily in the first and second decades of life (35–92%). In the present study, patients ranged between the age group of 15–46 years.

Thirteen out of 25 patients were female, with trauma being the most common etiologicl factor. This female predilection is in congruence with the observation made by Vinay Kumar et al. [8, 11]. One can infer herein the still inferior status of the girl child in Indian society—injury to ‘her' is not taken as seriously as to ‘him'.

In this study, pre-operative maximal mouth opening (MMO) ranged from 0 to 8 mm (mean 3.7 mm) and at the 12th month post-op showed a range of 31–39 mm (mean 35.5 mm), respectively, which is slightly greater than the results of Liu et al. [9] (34 mm).

The average MMO at maximum follow-up in the cases where we used dermal fat graft interposition was 34.25 mm, temporalis muscle and fascia flap interposition was 33.37 mm, and buccal fat pad interposition was 35.57 mm, which was comparable to the values of Dimitroulis [10]—35.7 mm, Su-Gwan [11]—36.1 mm and Singh [12]—35.1 mm, respectively.

Temporalis myofascial flap as interpositional material requires a longer incision and can cause temporal hollowing and nerve injury. Abdominal dermis fat harvesting is easy, but leaves a scar in the periumbilical region. Buccal fat pad has abundant blood supply from the maxillary artery and the superficial and deep temporal artery. It causes no additional incision, no hollowing and no facial paresis.

Thus, although the difference in mouth opening between these three is not significant during this limited follow-up period, we may hypothesize that the resorption of buccal fat pad is probably less than dermal free fat, hence would last longer and lead to greater increase in mouth opening up to a longer period of time, apart from its obvious advantage of having no additional scar.

Performing genioplasty prior to ankylosis release gives a stable mandibular base in the form of ankylosis and hence relative ease of osteotomy. Although 8–10 mm forward and translational movements can be considered as the limit of genioplasty in these bone deficient ankylosis cases, corrections beyond that also may be achieved using onlay autogenous/alloplastic bone grafts.

Hinds and Kent favour dissection and protection of the mental nerve during osteotomy [13]. Skeletonization of the mental nerve was done in all our cases.

Mani et al. [14] opted to intentionally transect the nerve whenever necessary followed by re-anastomosis before wound closure. Although we did not intentionally transect the mental nerve in any case, we would like to mention one case in which mental nerve was accidentally transected during retraction but was sutured back in mental foramen. The patient had return of neurosensory function within 6 months.

The most serious and life-threatening complication of genioplasty would be a haematoma dissecting into the floor of the mouth with resulting tongue elevation and airway obstruction. None of the patients in our study demonstrated this. This is best managed through prevention with judicious haemostasis of both the soft tissue and bone [12]. Another method is placement of a drain, making its way out extraorally. After the first two cases wherein we had minimal opening up of intraoral sutures, due to collection we started placing drains routinely in all our patients and did not have the same problem thereafter.

Suturing was done only in one layer with deep, thick bites. Suturing in two layers after advancement genioplasty leads to an unsightly, accentuated labiomental fold.

Kirkpatrick and Woods [15] showed a mean horizontal relapse of 8% after mandibular advancement using rigid fixation. No major relapse was observed in this study in cases where osteotomized segment was stabilized with plates and screws (average 0.3 mm). However, two cases where trans-osseous wiring was used revealed a minimal relapse of 1.8 and 2.0 mm, respectively.

The AHI reduced from pre-op average of 10.64 to 4.6, as in accordance with the study by Santos et al. [6], which showed AHI reduction from 12.4 to 4.4, in 10 cases of osseous genioplasty which decreased or eliminated the severity of OSA by increasing PAS.

Posterior airway space (N-PAS) showed an increase from 4.44 to 7.36 mm, a total average increase of 2.92 mm, with an advancement genioplasty of 7.28 mm. This was similar to average increase of 2.9 mm, with an advancement genioplasty of 9 mm done by Santos et al. [6].

The outcomes of vertical sliding of the posterior part of the mandibular ramus for reconstruction of the mandible condyle are promising (Fig. 3). In contrast to free grafts, the use of the posterior border of the mandible as a pedicled graft (on medial pterygoid) avoids complications associated with the donor site and prevents bone resorption, causing lesser decrease in height of the mandible ramus and mouth-opening deviation [16]. In the limited follow-up that this study has evaluated, there has been no re-ankylosis.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram; L shaped osteotomy (left), vertical ramus osteotomy (right)

Out of 43 joints, the newly reconstructed RCU was measured from lower osteotomy cut to the highest point of the neocondyle and resulted in minimal resorption. This is comparable with the results of the study by Liu et al. [9]. RCU reconstruction creates a stop in the region of gap arthroplasty and prevents ramal shortening and hence posterior gagging and anterior open bite in bilateral cases and ipsilateral deviation in unilateral cases. Therefore, deviation and open bite occurred in only 2 out of 43 joints. This was managed by application of elastics during night for 1 week followed by guiding elastics for 2 weeks. No permanent occlusal disturbance was noted.

Our study involved simultaneous Genioplasty and RCU reconstruction with ankylosis release. It offers the advantage of a single-stage surgery. Disadvantages of other single-stage procedures are as follows:

- In case bimaxillary orthognathic surgery is done along with ankylosis release:

- Long hours under general anaesthesia, which is physically and financially very taxing on the already undernourished and underweight patients.

- Possible requirement of extremely accurate splints prepared by latest 3D printing technology.

- If surgeries for skeletal deformities are performed before TMJ becomes stable, treatment outcomes in terms of occlusion may be unsatisfactory.

- In case distraction is done along with ankylosis release,

- Patient must have sufficient overjet, which may not be possible if patients are not willing for prolonged pre and post-surgical orthodontics.

- Mouth-opening exercises may cause a pseudo-joint [20] at the distraction site, ultimately compromising the surgical outcome.

Two-stage surgeries have the obvious disadvantage of two procedures. Also, post-release distraction osteogenesis/orthognathic surgeries in adults can have occlusal complications unless the patient is willing for long and expensive pre- and post-surgical orthodontics. Most of our patients came from extremely far off places and belonged to the lower socio-economic strata and could not keep coming back for protracted, expensive orthodontics. Many were not even willing to undergo more than one surgery. Hence, this is a good option of giving them as much result as possible in just one surgery.

With this strategy, in a single surgery, the following objectives were achieved:

Improvement of quality of life of the patient, restoration of function, i.e. mouth opening, and correction of facial asymmetry to a significant extent—all in a single stage.

Reduction/elimination of the episodes of nocturnal desaturation and hence reduction in OSA.

Prevention of ramal shortening and occlusal discrepancies by reconstructing the RCU.

Relative ease of subsequent intubation if needed due to the fact that posterior pharyngeal airway space had been increased by the genioplasty.

No compromise in any further osteotomies, if so required and desired by the patient.

This study excludes patients with AHI > 20. OSA has for long been ignored as an extremely important decision-making factor in the treatment of TMJ ankylosis. This study recognizes its unmistakable role and advocates pre release distraction for all patients AHI > 20. A landmark article by Andrade et al. [21] strongly suggests the same.

Conclusion

This single-stage surgery for TMJ ankylosis release with gap arthroplasty, RCU reconstruction and simultaneous correction of facial asymmetry by genioplasty can be considered as a promising treatment modality for this distressing condition in adults.

Based on the findings of the above study, we propose the following guidelines for treatment of TMJ ankylosis in adult patients with AHI < 20:

Release of the ankylotic mass performing a 1.5 cm gap arthroplasty and removal of ipsilateral coronoid process and use of buccal fat pad as interpositional material.

RCU reconstruction with vertical ramus osteotomy in the cases with prominent antegonial notch and L osteotomy in the others.

Genioplasty with or without interpositional and onlay bone grafts.

References

- 1.Chidzonga MM. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Review of thirty-two cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37(2):123–126. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1997.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Sheikh MM, Medra AM, Warda MH. Bird face deformity secondary to bilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24:96–103. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(96)80020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandell DL, Yellon RF, Bradley JP, et al. Mandibular distraction for micrognathia and severe upper airway obstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):344–348. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elgazzar RF, Abdelhady AI, Saad KA, Elshaal MA, Hussain MM, Abdelal SE, Sadakah AA. Treatment modalities of TMJ ankylosis: experience in Delta Nile. Egypt Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(4):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaban LB, Bouchard C, Troulis MJ. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(9):1966–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos JF, Jr, Abrahão M, Gregório LC, Zonato AI, Gumieiro HE. Genioplasty for genioglossus muscle advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome and mandibular retrognathia. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73(4):480–486. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30099-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunaseelan R, Anantanarayanan P, Veerabahu M, et al. Simultaneous genial distraction and interposition arthroplasty for management of sleep apnoea associated with temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36(9):845–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon TG, Park HS, Kim JB, et al. Staged surgical treatment for temporomandibular joint ankylosis: intraoral distraction after temporalis muscle flap reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(11):1680–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Zhu SS, Wang T, Luo E, Xiao L, Hu J. Staged treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with micrognathia using mandibular osteodistraction and advancement genioplasty. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(12):2884–2892. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitroulis G. A critical review of interpositional grafts following temporomandibular joint discectomy with an overview of the dermis fat graft. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(6):561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su GK. Treatment of TMJ Ankylosis with temporalis muscle and fascia flap. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(3):189–193. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh V, et al. Buccal fat pad as an interpositional graft in TMJ ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2530–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinds EC, Kent JN. Genioplasty: the versatility of horizontal osteotomy. J Oral Surg. 1969;27:690–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mani V, et al. Extended lateral sliding genioplasty for correction of facial asymmetry. Asian J oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;16(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/S0915-6992(04)80014-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirkpatrick TB, Woods MG. Skeletal stability following mandibular advancement and rigid fixation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:572–576. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loftus MJ, et al. Osteochondroma of the mandibular condyles. Report of three cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:221. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elgazzar RF, Abdelhady AI, Sadakah KAA. Treatment modalities of TMJ ankylosis: Experience in delta Nile Egypt. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gundlach KK. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010;38:122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maki MH, Al-Assaf DA. Surgical management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:1583. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31818ac12c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu S, Li J, Luo E, Feng G, Ma Y, Hu J. Two-stage treatment protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with secondary deformities in adults: our institution’s experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:e565. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrade N, et al. New protocol to prevent TMJ reankylosis and potentially life threatening complications in triad patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:1495–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]