Abstract

Orbital fractures with orbital wall defects are common facial fractures encountered by oral–maxillofacial surgeons, because of the exposed position and thin bony walls of the midface. The primary goal of surgery is to restore the pre-injury anatomy and volume of hard tissue, and to free incarcerated or prolapsed orbital tissue from the fracture by bridging the bony defects with reconstructive implant material and restoring the maxillofacial–orbital skeleton. Numerous studies have reported orbital fracture repair with a wide variety of implant materials that offer various advantages and disadvantages. The ideal orbital implant material will allow conformation to individual patients’ anatomical characteristics, remain stable over time, and are radiopaque, especially for the reconstruction of relatively large and/or complex bony walls. Based on these requirements, novel uncalcined and unsintered hydroxyapatite (u-HA) particles and poly-L-lactide (PLLA; u-HA/PLLA) composite sheets could be used as innovative, bioactive, and osteoconductive/bioresorbable implant materials for orbital reconstruction. In addition, intraoperative navigation is a powerful tool. Navigation- and computer-assisted surgeries have improved execution and predictability, allowing for greater precision, accuracy, and minimal invasiveness during orbital trauma reconstructive surgery of relatively complex and large orbital wall defects with ophthalmological malfunctions and deformities. This review presents an overview of navigation-assisted orbital trauma reconstruction using a bioactive, osteoconductive/bioresorbable u-HA/PLLA system.

Keywords: Orbital trauma, Orbital reconstruction, Navigation, u-HA/PLLA

Introduction

The facial orbit is often affected by traumatic injuries, and orbital fractures are common in oral–maxillofacial surgery. Orbital fractures with orbital defects are common because of the exposed position and thin bony walls of the midfacial area. Approximately 30–40% of orbital fractures occur in combination with other midfacial fractures, including zygomatic complex fractures, Le Fort II and III fractures, nasoorbital–ethmoid fractures, and frontal bone/orbital roof fractures, although they may occur alone [1, 2]. More than half of medial inferior orbital wall fractures occur just medial to the junction between the infraorbital groove and inferior orbital fissure [1]. Complications of post-traumatic orbital deformities when the primary reconstruction is inaccurate include diplopia, enophthalmos, restricted eyeball mobility, disturbed sensory innervation, reduced globe motility, and altered visual acuity associated with increased or distorted orbital volume [2].

The goal of reconstruction is reduction in the enlarged bony orbit and reconfiguration of the orbital morphology [1–3]. Precise reconstruction of the orbit is the primary step in restoring normal function and esthetic appearance. However, reconstruction outcomes are unpredictable because of the difficulty of reconstructing the complex orbital contour. Anatomical orbital landmarks function as important guides during surgery and may be helpful for orbit reconstruction. However, it can be difficult to locate the posterior ledge, which is the most important dorsal anatomical landmark and provides support for reconstruction material [1, 3]. Despite advances in diagnostic and surgical procedures, treatment of these fractures remains challenging for maxillofacial surgeons because of limited vision in the working space for minimal surgical approaches; difficulty in manipulating prolapsed orbital soft tissues; and difficulty in reconstructing the three-dimensional (3D) orbital architecture, especially of the posterior medial bony orbit [1–4].

Intraoperative navigation is used to address these challenges and has recently been used more commonly in orbital reconstruction to verify that the reconstruction was performed successfully. Navigation-assisted orbital reconstruction was first introduced by Gellrich et al. [5]; several reports have subsequently modified and refined these computer-aided techniques using new technologies [1, 5–8]. In recent years, many studies have supported the feasibility of this technique. Preliminary outcome data have supported the potential of this technique for restoring orbital volume. Using this approach, the position of the tip of the navigation pointer is visualized in real time and can be used to assess the position of the implant in the orbit. This information is presented to the surgeon in multiplanar views corresponding to the current position of the navigation pointer; the contour of the restored orbit is evaluated. This allows the surgeon to quickly alter views if the pointer is moved over the contour of the orbital implant. However, this may limit accurate assessment of the implant position in three dimensions since the implant position must be deduced from the contour feedback in the multiplanar view.

Intraoperative computer-assisted planning is considered an effective technique for re-establishing orbital symmetry [8–10]. Moreover, computer-assisted navigation has recently evolved to improve precision and simplify the surgical procedure by minimizing surgical invasiveness. The development of intraoperative navigation surgery has improved execution and predictability, allowing for greater precision during maxillofacial surgery [8–10].

For orbital reconstruction implants, many materials including autologous grafts and synthetic materials have been used for reconstruction [11]. The ideal implant material must meet a variety of requirements, such as being biocompatible, non-carcinogenic, non-allergenic, radiopaque, and sufficiently strong to support the orbital contents. Alloplastic materials should be cost-effective and amenable to sterilization. Resorbable implants should completely resorb without forming harmful degradation products. The implant should be available in large quantities, and cutting, adjusting, and fixing it to the orbital wall(s) should not be complicated. To achieve long-term reliable results with large orbital wall fractures and greater dislocation of bony fragments, materials with better mechanical properties are required. Ideal implants would provide good structural support and be biocompatible, easily positioned, and readily available [11].

Currently available materials do not meet these criteria fully; thus, there is no general guideline as to which of these materials should be used for orbital reconstruction. Although autografts have been traditionally considered the “gold standard,” they give rise to various problems and difficulties, including limited availability, the need for extra surgery, and a higher risk of donor site morbidity [11]. Patient-specific implants based on titanium or ceramic to restore the orbital anatomy are becoming increasingly popular [7, 8, 10, 11]. Although initial studies are promising, data on long-term results are lacking. There are several disadvantages, such as the time-consuming fabrication (at least a few days) and the high cost. Since it is a foreign body, there is a risk of infection, even years after insertion, as observed in patient-specific titanium cranioplasties. For secondary trauma, there may be a higher risk of injury due to the rigid foreign body.

Recently, the resorbable plate system has proved to be an effective material [12]. Bioresorbable osteosynthesis technology is constantly evolving to enhance bioresorbability and bioactive osteoconductivity, with new compositions of materials being used to improve the in situ behavior [12]. In particular, SuperFIXSORB-MX® (Japanese trade name; known as OSTEOTRANS-MX elsewhere; TEIJIN Medical Technologies Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan), which is a composite of fine unsintered hydroxyapatite (u-HA) particles and carbonated ions combined with poly-L-lactide (PLLA; u-HA/PLLA), is a promising bioactive, osteoconductive, and completely resorbable osteosynthetic bone fixation and maxillofacial reconstructive material that has recently drawn attention for its long-term clinical stability in maxillofacial skeletal fixation and reconstruction [12–14]. The groundbreaking osteoconductive and bioactive properties of these composites allow them to fuse directly with bone. Thus, u-HA/PLLA composites are of interest as an ideal candidate material for orbital wall reconstruction because of their advantageous physical properties, high levels of customizability and control, and ability to support the orbital content [1, 10, 12]. This innovative, bioactive, osteoconductive/bioresorbable sheet was first introduced for orbital reconstruction by Landes et al. [15].

This short review presents an overview of navigation-assisted orbital trauma reconstruction using a bioactive, osteoconductive/bioresorbable u-HA/PLLA sheet system.

Intraoperative Navigation

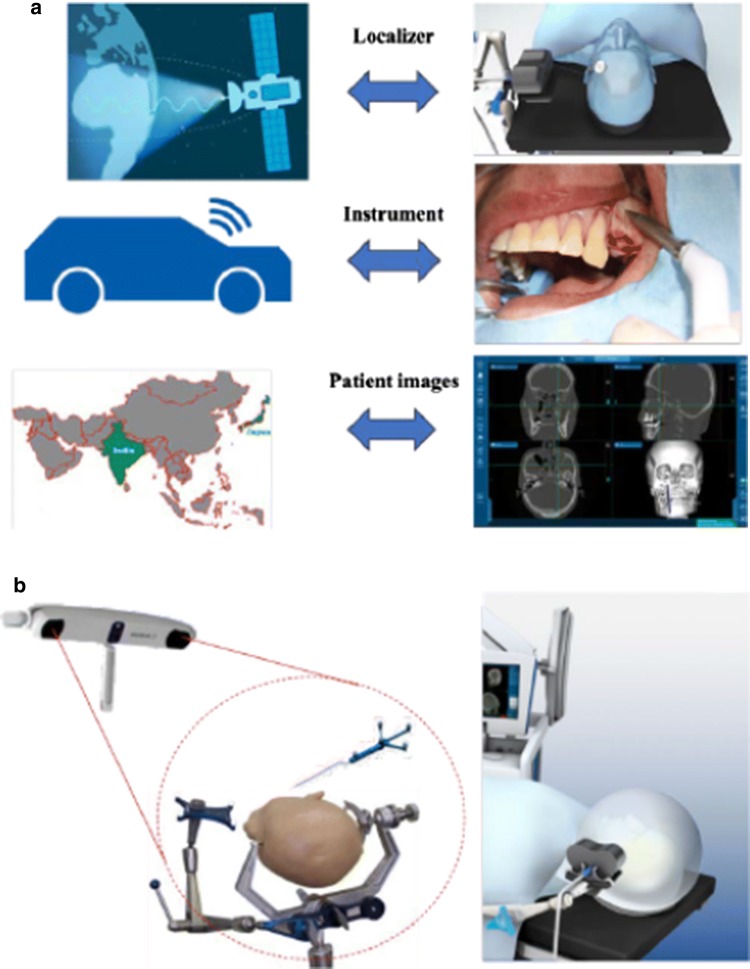

“Intraoperative navigation-assisted surgery” can be interpreted in various ways. Navigation-assisted surgery is most usefully defined by the questions: “Where is our anatomical target?,” “How do we reach our target safely?,” and “Where are we anatomically?” Apart from these important orientation questions, navigation-assisted surgery is used as an “information center” to provide surgeons with the correct information at the right time [7, 10]. Surgical navigation systems are generally similar to a Global Positioning System (GPS), as used commonly in automobiles, and is composed of three primary components: a localizer, which is analogous to a satellite in space; an instrument or surgical probe, which represents the track waves emitted by the GPS unit in the vehicle; and a CT scan data set, which is analogous to a road map. Surgical navigation systems were initially developed for neurosurgery and are now commonly used in various craniomaxillofacial surgery because of their reliability and high accuracy, which could be suitably applicable for complex orbital trauma reconstruction [7, 10] (Fig. 1a). There are two main types of navigation system currently available, optical and electromagnetic, both of which perform the same functions (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Components of an intraoperative surgical navigation system. Navigation system is comparable to a Global Positioning System (GPS) commonly used in automobiles and is composed of three primary components. b Two main types of navigation system currently available: optical (left) and electromagnetic (right)

u-HA/PLLA Bioactive, Osteoconductive Bioresorbable Material

Recently, hydroxyapatite has been incorporated into “the first-generation” bioresorbable osteosynthetic material poly-L-lactide (PLLA) because of the known osteoconductive capacity of hydroxyapatite (Fig. 2a) [12]. SuperFIXORB-MX® (known as OSTEOTRANS-MX® outside of Japan; TEIJIN Medical Technologies Co., Ltd) plates are made of a composite material consisting of fine particles of u-HA and carbonate ions combined with PLLA. Forged composites of u-HA/PLLA were processed by machining or milling treatments into various mini-screws and mini-plates containing 30% and 40%, respectively, weight fractions of u-HA particles (raw hydroxyapatite; no calcined or sintered material) in composites (hereinafter referred to as u-HA 30% mini-screws and tack and u-HA 40% mini-plate) as “the third-generation” bioresorbable material [12]. Copolymers of PGA, PLLA, and PDLA are classified as “the second generation” and are much more rapidly bioresorbable osteosynthetic materials compared to pure PGA and PLLA [12].

Fig. 2.

a Maxillofacial osteosynthesis systems using third-generation bioactive/bioresorbable materials, the SuperFIXORB-MX® (OSTEOTRANS-MX®) system; TEIJIN Medical Technologies Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan. b The currently available two main types of intraoperative navigation systems for our routine complex orbital trauma reconstructive surgery: optical surgical navigation system (left:; Brainlab, Feldkirchen, Germany) and electromagnetic surgical navigation systems (right: the StealthStation, Medtronic, Inc., Louisville, Colorado, USA)

These devices maintain a bending strength equal to human cortical bone for 25 weeks in vivo. Once it has been implanted, PLLA is hydrolyzed by body fluids and undergo biodegradation. The molecular weight of PLLA decreases, and the u-HA fraction increases, for about 2 years. The PLLA matrix is completely absent from the composites after more than 4 years, and the majority of u-HA particles are replaced with bone after 5.5 years. Regarding bioresorbability, reinforced fabricated PLLA is hydrophobic and degrades slowly; a thin PLLA film provides an interface with invading water molecules, allowing homogeneous hydrolysis and steady degradation of the PLLA matrix in u-HA/PLLA composite materials [12]. The resulting release of small amounts of PLLA debris has not been shown to result in adverse tissue responses in experimental or clinical studies [12–19]. Thus, u-HA/PLLA prevents foreign body reactions because of its moderate and stable hydrolysis. The sheet/panel and screw/tack fixation system has shown stable degradation without foreign body reactions, in both in vivo and clinical studies [1, 10, 12]. However, as complete resorption occurs over 4 years or more, its gradual progress must be followed regularly by CT during bone healing. CT radiography can confirm reconstruction at the site of bone healing; the reconstructed sheet and screws can be observed because u-HA particles render them radiopaque, which represents another advantage of this type of material [12]. CT radiography showed spanning of the fracture site by the reconstructed sheet at various stages of healing, indicative of bone regeneration by this osteoconductive bioactive material, as reported previously [10, 12].

Furthermore, the u-HA/PLLA composite material shows higher mechanical strength, including bending strength, bending modulus, shear strength, and impact strength compared to PLLA devices. u-HA/PLLA plates can bond directly to bone with osteoconductivity [12, 16]. Several recent clinical reports have explored the bioactive, osteoconductive, direct bone healing effects of this plate system using scanning capacitance microscopy analysis on an incompletely exposed plate after removal [12, 16]. Deposits of bone-like tissue were evident on the bone-contacting surface of the removed plate. This shows that the plates directly bonded to bone and support the osteoconductivity of the u-HA/PLLA plate system [18, 19]. Early osteoconductive bioactivity is advantageous for early functional improvement after maxillofacial fractures surgery. Due to its bioactive, osteoconductive, and biodegradable properties, this u-HA/PLLA composite material has clinical advantages and may prove an ideal next-generation osteosynthetic or implant material.

Thus, u-HA/PLLA composites are of interest as suitable candidate materials for orbital wall reconstruction because of their advantageous physical properties, high levels of customizability and control, and sufficient stability to support the orbital contents [12]. Thus, this sheet was anatomically bent based on computer-assisted 3D morphological customization preoperatively, to conform to the natural bony contours of the orbit such as reproducing the upward posteromedial slope of the floor and the anterior-to-posterior S-shaped curvature [10, 12].

u-HA/PLLA Implant Application for Orbital Trauma Reconstruction

Many implant materials have been used for orbital reconstruction, including autologous tissues such as bone or cartilage as well as synthetic materials [11]. The success of orbital reconstruction depends on several factors, such as the surgical technique and the general medical condition of the patient, in addition to the properties, design, and biocompatibility of the reconstruction material [11]. A perfect biomaterial would be chemically inert, bio-friendly, and non-allergenic. In addition, it should be cost-effective, readily available, sterilizable, and easy to handle, and should also be stable and retain its shape once manipulated. Preferably, it should be radiopaque to allow radiographic evaluation without producing artifacts that may mask important features on subsequent radiologic examination. Briefly, in defining the ideal characteristics of an orbital reconstructive implant material, many surgeons prefer materials that allow conformation to individual patients’ anatomical characteristics, remain stable over time, and are radiopaque [11].

In this regard, u-HA/PLLA composites are one of the most promising implant materials for orbital reconstruction, as they fulfill these clinical requirements [12]. These materials are particularly suitable for application as an internal reconstructive bone fixation device in the anatomically complex maxillofacial skeletal region not only because of their mechanical properties (such as their thinness and their mechanical and bending strength, which approaches that of maxillofacial cortical bone) but also because of their osteoconductivity and bioresorbability [18, 20–22]. Together, these characteristics make u-HA/PLLA composites highly advantageous for bone healing and allow easy shaping and adjustment to 3D morphology. Using appropriate surgical techniques, we believe that these composites may be superior to conventional metal materials, such as titanium mesh or sheet plates, as well as other commercially available bioresorbable materials, such as PLLA and PLLA/PGA sheets, panels, or mesh for surgical reconstruction of midfacial fractures with large orbital wall defects.

Landes et al. [15] first reported the successful application of u-HA/PLLA orbital mesh with screw fixation for two cases of orbital floor reconstruction in a 5-year prospective long-term follow-up clinical study of a midfacial fracture treatment using u-HA/PLLA systems, although Hayashi et al. [23] had already reported the suitability of u-HA/PLLA composite as an osteosynthetic device for 17 midfacial fracture operative treatments (but had not applied this to orbital wall reconstruction); Landes et al. [15] explored the intraoperative handling of these implants, and successful fracture stabilization and reossification with a low incidence of mild foreign body reactions were reported in all patients, including orbital floor reconstruction, with a focus on the feasible osteoconductive properties of the composite material, similar to other HA-based bone replacement materials that slowly transform to bone.

Park et al. [24] evaluated the usefulness of u-HA/PLLA implants for the repair of pure medial orbital wall fractures of medial wall defects in 10 cases with expected future enophthalmos, defects greater than 2.5 cm2, extraocular movement impairment, and/or diplopia. The clinical results were satisfactory, although the report did not mention whether the implant material was mesh or sheet, and none of the patients experienced complications related to surgery, such as infection or enophthalmos, throughout the follow-up period [24]. They concluded that u-HA/PLLA implants are safe and reliable for reconstruction of the medial wall of the orbit, in terms of rigidity, immobility, radiopacity, and cost-effectiveness [24]. However, they also described difficulty with manipulation and molding, which is inconvenient for reconstruction of a complex 3D defect; possible migration was also mentioned in their report.

In 2016 [1], we supported the feasibility of u-HA/PLLA sheets in nine patients with moderate-/medium-complexity to large/high-complexity orbital wall defects associated with severe midfacial trauma in most cases, and of orbital floor and combined orbital floor plus medial orbital wall reconstruction under navigation assistance. An intraoperative optical navigation system (Brainlab, Feldkirchen, Germany) based on preoperative computed tomography (CT) data was first combined to determine the extent of orbital wall defects and confirm three-dimensionally accurate placement of the u-HA/PLLA sheet implant for reconstruction (Fig. 2b) [1, 10, 25, 26]. Furthermore, the u-HA/PLLA sheet was stabilized with tack(s) with a backstitch shape, where the application of u-HA/PLLA sheets with the tack fixation technique reduced the risk of sheet migration in the orbit and provided excellent stability for orbital wall reconstruction at fragile and anatomically complicated periorbital maxillofacial bony regions, without the risk of unexpected orbital wall breakage, which would exacerbate the orbital wall defect and cause screw loosening [1, 10]. Although the mean follow-up period was 8.9 months, we observed satisfactory ophthalmologic functional results with no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Furthermore, we reported the advantages of u-HA/PLLA sheets with tack fixation under intraoperative navigation assistance during computer-assisted surgery (CAS) for relatively large complex orbital floor and medial defect complex reconstruction, in five cases using a single-folded u-HA/PLLA sheet (Fig. 3) [10]. The u-HA/PLLA sheet was preoperatively fabricated, shaped, and prepared using a computer-assisted 3D morphological customization technique, mirroring the preoperative 3D model image of the u-HA/PLLA sheet [10]. Computer-assisted, single-folded u-HA/PLLA sheets fabricated using a tack fixation technique provide satisfactory ophthalmologic functional results for large and complex combined orbital floor and medial wall fracture reconstruction, with no intraoperative or postoperative complications [10].

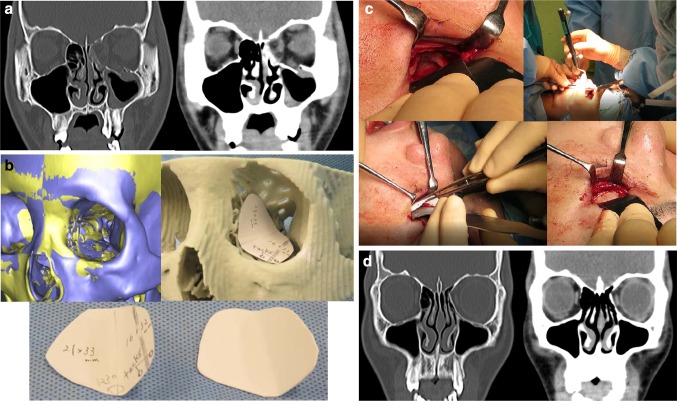

Fig. 3.

A 17-year-old male patient with left maxilla and nasoorbital–ethmoid fracture with a large combined orbital floor and medial walls defect fracture of type IV defect [10]. a Preoperative CT scans. b The original preoperative 3D-model image was evaluated overlapping the mirrored 3D-model image for 3D morphological individual customization of u-HA/PLLA sheets using the stereolithographic model and testing paper. c An intraoperative photograph showing the single-folded u-HA/PLLA sheet reconstruction with tack fixation under surgical navigation assistance. d 12 months postoperative CT scans

Recently, the feasibility of navigation-assisted isolated medial orbital wall fracture reconstruction using u-HA/PLLA sheets, fabricated by tack fixation, for isolated medial wall fracture reconstruction has been explored [27]. In 2018, the largest clinical study on this topic, by Kohyama et al. [28], showed both the immediate- and long-term results of u-HA/PLLA composite sheets for orbital wall fracture reconstruction in 115 patients, although they did not apply intraoperative navigation- or a computer-assisted approach. In this research, in 70 eligible cases, the u-HA/PLLA mesh or sheet showed excellent safety and effectiveness in the reconstruction of orbital wall fractures. Of the 70 patients, 10 had postoperative diplopia and 2 had enophthalmos; these conditions were presumably caused by the extent and severity of the fracture [28]. Satisfactory reduction in the entire orbital wall was demonstrated without pathological changes and with no significant differences in mean bony orbital volume of the affected side between immediately after surgery and at the latest follow-up [28].

u-HA/PLLA has a similar cost performance compared to other common commercially available orbital biomaterial implants and is superior to the costly patient-specific titanium orbital reconstruction plate systems [12, 24, 27, 28].

Feasibility of Computer-Assisted Intraoperative Navigation Orbital Trauma Reconstruction Using u-HA/PLLA Bioactive Osteoconductive Bioresorbable Material

Computer-assisted surgery can improve outcomes in complicated maxillofacial trauma surgeries, especially orbital trauma reconstruction [5–10, 25]. The use of 3D CT imaging reconstruction and virtual planning provides accurate and individualized assessments for the restoration of orbital walls, orbital volume, and orbital fractures with bony defects, as reported previously. Proper implant sizing and shaping is critical to the success of this technique [25]. Given the relatively large surface area of the implant, the rigidity of the material, and the proximity of the implant to vital orbital structures such as the optic nerve, small deviations in contour and shape can result in significant complications [25]. The first step in CAS for orbital reconstruction is segmenting the orbital walls and orbital volume. Using a mirroring technique, the unaffected side can be emulated on the deformed side to achieve symmetry, creating a template for an ideal orbit. Using this technique, preoperative preparation can easily be performed, resulting in accurate orbital reconstruction. Computer-assisted pre-surgical planning includes preoperative surgical simulation with 3D images or models. Preoperative virtual planning, as part of CAS, is considered a valuable addition for pre-traumatic orbital anatomical reconstruction [25]. The outcome of the surgical correction depends on the shape and position of the orbital implants. One advantage of a preformed implant is that a stereolithographic (STL) software file of the implant can be used preoperatively to identify the optimal fit and position in a digital environment [25]. Therefore, we recommend the use of computer-assisted 3D morphological customization, even for single-folded u-HA/PLLA composite sheets, as well as preoperative CT scan measurements, to determine the appropriate dimensions of the implant (Fig. 4) [25]. Additionally, 3D intraoperative positioning of the implant on stable ledges of bone is critical, as no implant, no matter how well designed or shaped, will function properly if not placed in an anatomically correct position.

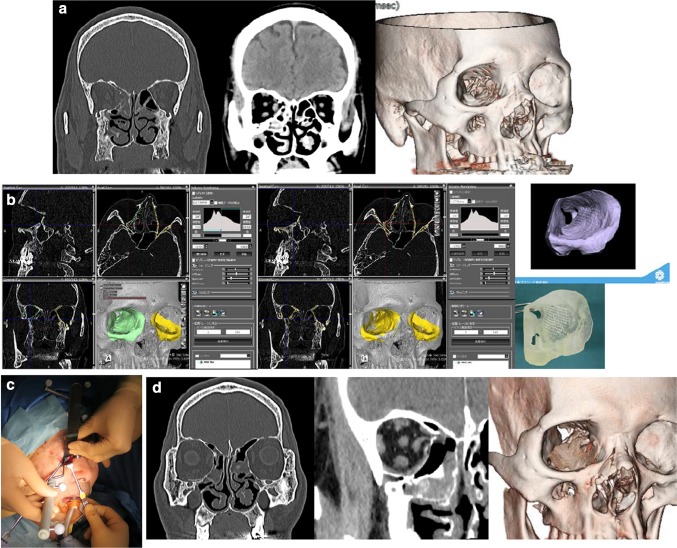

Fig. 4.

A 68-year-old male patient with right maxilla and nasoorbital–ethmoid fracture with a large combined orbital floor and medial walls defect fracture of type IV defect. a Preoperative CT scans. b The original preoperative CT images were evaluated overlapping the mirrored CT images from the uninjured side for up-to-date 3D morphological precise individual customization of u-HA/PLLA sheets using the actual orbital simulation stereolithographic model (Yasojima Proceed Co., Ltd, Osaka, Japan). c An intraoperative photograph showing the u-HA/PLLA sheet reconstruction with tack fixation under surgical navigation assistance. d Postoperative CT scans

The limited working space for minimal surgical approaches hinders the view of the orbital defect and complicates the verification of implant position during surgery, which may result in suboptimal placement of the implant and unsatisfactory outcomes such as enophthalmos and/or diplopia [5–8, 27]. Recently, preoperative computer-assisted planning with virtual implant placement has been combined with intraoperative navigation to reconstruct the bony orbit more accurately and thus optimize treatment outcomes. Intraoperative navigation assists the surgeon in achieving optimal reconstruction. Preoperative surgical simulations with 3D images have been used to determine the appropriate position and size of orbital reconstruction implants. A system for navigation was developed to further “diagnosis–surgical planning–surgery,” allowing the surgeon to visualize the actual position of surgical instruments in real time on the monitor displaying the CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 3D data of the patient [25]. Navigation systems involve imaging the surgical field to reveal structures that are normally visible only intraoperatively, and permit navigation in areas of anatomical sensitivity. These systems have recently evolved, improving precision and simplifying the surgical procedure by minimizing intraoperative invasiveness. The development of navigation-assisted surgery has improved execution and predictability, allowing for greater precision during orbital trauma reconstructive surgery [25, 29, 30].

The feasibility of computer- and navigation-assisted orbital trauma reconstruction using u-HA/PLLA is supported by previous clinical studies, including our studies, although the only comparative clinical study available at this time is our retrospective clinical study (Sukegawa et al.) [31], which investigated the feasibility and precision of relatively large orbital trauma reconstruction employing the u-HA/PLLA mesh plate system, with and without intraoperative computer-assisted navigation, using an electromagnetic navigation system (Medtronic StealthStation S7 workstation using Synergy Fusion Cranial 2.2.6 software; Medtronic, Louisville, CO, USA). Although the number of patients recruited to the study was small, it examined their postoperative healing status, including visual acuity, diplopia, and enophthalmos, and compared the overall volume of the orbit, measured in cubic millimeters, to reconstructed and uninjured orbits with and without intraoperative computer-assisted navigation [31]. We showed a significant difference in the accuracy of the mean reconstructed orbital volume with versus without intraoperative computer-assisted navigation guidance. No patient complained of visual problems, no further treatment was required postoperatively, and all the preoperative diplopia symptoms improved postoperatively. In addition, no patient complained of problems with activities of daily living, excluding one patient in the group without navigation who experienced slight but persistent supraversion diplopia. Therefore, complex orbital trauma reconstruction using optimal bioactive/resorbable u-HA/PLLA material with computer-assisted navigation guidance is an accurate and reliable method for complex orbital trauma repair [31].

Future Perspectives and Conclusions

The major drawback of the u-HA/PLLA system is common to all other commercially available biomaterials, namely the difficulty of manipulation and bending, which impedes the generation of complex 3D shapes with curves that conform to the anatomical shape of orbital wall(s) [12, 32]. However, the u-HA/PLLA sheet, panel, or mesh can be warmed and molded through several cycles during each operation, a process that is much more efficient and precise when used in conjunction with computer-assisted preoperative preparation.

Patient-specific titanium mesh orbital wall reconstruction is the most commonly used implant material for complicated orbital reconstructions, with feasibility supported by clinical reports [7–9, 11, 29, 30]; however, as next-generation biomaterials for orbital trauma reconstruction, u-HA/PLLA composites may become more common as patient-specific, anatomically modified bioactive orbital implants with the application of current CAS techniques based on computer-aided design/manufacturing, along with computer simulation data [32]. These methods are very useful for precise, individualized orbital reconstruction, since 3D model creation and plate production for fabricating implant materials are expensive and time-consuming, making them unsuitable for emergency surgery [15, 25, 29, 30].

The advantage of using CAS and the surgical navigation system is the ability to check implant fit both preoperatively and intraoperatively in an accurate digital environment. This digital planning is not material-specific; the only prerequisites are that the material is sufficiently rigid and the digitally formed shape accords with the actual shape of the implant, even after manipulation. Furthermore, intraoperative navigation allows for accurate plate formation during emergency surgery. Furthermore, it is possible to evaluate the status of whole orbital wall reconstruction and implant/plate positioning several times during the procedure. Although conventional orbital reconstruction can ensure that no clinical functional disorder occurs, more accurate orbital reconstruction is possible using intraoperative navigation. Thus, we support the use of an intraoperative navigation system for relatively complex and large orbital trauma reconstruction [31]. In addition, some recent studies have shown a significant difference in the accuracy of orbital reconstruction surgery [29, 30]. Therefore, application of this system for minimally invasive orbital trauma reconstruction surgery allows the procedure to be performed rapidly, safely, and precisely, and increases confidence in the orbital reconstruction. In the future, CAS is expected to further reduce operation risks and time, thus considerably decreasing patient distress. A navigation system would be effective and feasible for use with orbital reconstruction.

We expect further developments to yield simpler and smaller tools, which will allow for direct tracking of the midface and orbits via a sensor frame and fiducial markers [25]. In addition, it is difficult to renew intraoperative images, but recent technological advances allow for intraoperative CT image editing via hybrid operating rooms equipped with C-arm or helical CT systems. Moreover, CT images for navigation during surgery for complex maxillofacial fractures have made it possible to conduct intraoperative evaluations after movement of orbital bone segments [25]. Hence, navigation surgery will likely become more common with the continued use of this technology.

In conclusion, reconstruction of relatively large and/or complex orbital traumas can be achieved using an optimal bioactive, osteoconductive, bioresorbable, and biocompatible u-HA/PLLA material with intraoperative navigation. Although this orbital reconstruction method is accurate, precise, and reliable, further long-term observational studies are required. In addition, randomized controlled trials should be performed to compare computer-assisted intraoperative navigation orbital reconstruction using u-HA/PLLA versus conventional methods.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the colleagues in the Department of Ophthalmology and the Department of Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Shimane University Hospital, for their clinical examination, evaluation, collaborative treatment, and follow-up.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Takahiro Kanno, Phone: 81 853 20 2301, FAX: 81 853 20 2299, Email: tkanno@med.shimane-u.ac.jp.

Shintaro Sukegawa, Phone: 81 87 811 3333, Email: gouwan19@gmail.com.

Masaaki Karino, Phone: 81 853 20 2301, FAX: 81 853 20 2299, Email: karino71@med.shimane-u.ac.jp.

Yoshihiko Furuki, Phone: 81 87 811 3333, Email: furukiy@ma.pikara.ne.jp.

References

- 1.Kanno T, Tatsumi H, Karino M, Yoshino A, Koike T, Ide T, Sekine J. Applicability of an unsintered hydroxyapatite particles/poly-L-lactide composite sheet with tack fixation for orbital fracture reconstruction. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2016;25:329–334. doi: 10.2485/jhtb.25.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubois L, Steenen SA, Gooris PJ, Mourits MP, Becking AG. Controversies in orbital reconstruction–I. Defect-driven orbital reconstruction: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dubois L, Steenen SA, Gooris PJ, Mourits MP, Becking AG. Controversies in orbital reconstruction–II. Timing of post-traumatic orbital reconstruction: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Shibata A, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Sakaida K, Furuki Y. Treatment of orbital fractures with orbital-wall defects using anatomically preformed orbital wall reconstruction plate system. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2017;26:231–236. doi: 10.2485/jhtb.26.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gellrich NC, Schramm A, Hammer B, Rojas S, Cufi D, Lagrèze W, Schmelzeisen R. Computer-assisted secondary reconstruction of unilateral posttraumatic orbital deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1417–1429. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000029807.35391.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zizelmann C, Gellrich NC, Metzger MC, Schoen R, Schmelzeisen R, Schramm A. Computer-assisted reconstruction of orbital floor based on cone beam tomography. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:79–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rana M, Chui CH, Wagner M, Zimmerer R, Rana M, Gellrich NC. Increasing the accuracy of orbital reconstruction with selective laser-melted patient-specific implants combined with intraoperative navigation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:1113–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerer RM, Ellis E, 3rd, Aniceto GS, Schramm A, Wagner ME, Grant MP, Cornelius CP, Strong EB, Rana M, Chye LT, Calle AR, Wilde F, Perez D, Tavassol F, Bittermann G, Mahoney NR, Alamillos MR, Bašić J, Dittmann J, Rasse M, Gellrich NC. A prospective multicenter study to compare the precision of posttraumatic internal orbital reconstruction with standard preformed and individualized orbital implants. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44:1485–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen J, Schreurs R, Dubois L, Maal TJJ, Gooris PJJ, Becking AG. The advantages of advanced computer-assisted diagnostics and three-dimensional preoperative planning on implant position in orbital reconstruction. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:715–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanno T, Karino M, Yoshino A, Koike T, Ide T, Tatsumi H, Tsunematsu K, Yoshimatsu H, Sekine J. Feasibility of single folded unsintered hydroxyapatite particles/poly-L-lactide composite sheet in combined orbital floor and medial wall fracture reconstruction. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2017;26:237–244. doi: 10.2485/jhtb.26.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubois L, Steenen SA, Gooris PJ, Bos RR, Becking AG. Controversies in orbital reconstruction-III. Biomaterials for orbital reconstruction: a review with clinical recommendations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanno T, Sukegawa S, Furuki Y, Nariai Y, Sekine J. Overview of innovative advances in bioresorbable plate systems for oral and maxillofacial surgery. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shikinami Y, Hata K, Okuno M. Ultra-high-strength resorbable implants made from bioactive ceramic particles/polylactide composites. Bioceramics. 1996;996:391–394. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shikinami Y, Matsusue Y, Nakamura T. The complete process of bioresorption and bone replacement using devices made of forged composites of raw hydroxyapatite particles/poly-L-lactide (F-u-HA/PLLA) Biomaterials. 2005;26:5542–5551. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landes C, Ballon A, Ghanaati S, Tran A, Sader R. Treatment of malar and midfacial fractures with osteoconductive forged unsintered hydroxyapatite and poly-L-lactide composite internal fixation devices. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1328–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Katase N, Shibata A, Takahashi Y, Furuki Y. Clinical evaluation of an unsintered hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide osteoconductive composite device for the internal fixation of maxillofacial fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27:1391–1397. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Kawai H, Shibata A, Takahashi Y, Nagatsuka H, Furuki Y. Long-term bioresorption of bone fixation devices made from composites of unsintered hydroxyapatite particles and poly-l-lactide. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2015;24:219–224. doi: 10.2485/jhtb.24.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y, Kanno T, Tatsumi H, Miyamoto K, Sha J, Hideshima K, Matsuzaki Y. Feasibility of a three-dimensional porous uncalcined and unsintered hydroxyapatite/poly-D/L-lactide composite for the regenerative biomaterial in maxillofacial surgery. Materials (Basel) 2018;11:2047. doi: 10.3390/ma11102047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukegawa S, Kawai H, Nakano K, Kanno T, Takabatake K, Nagatsuka H, Furuki Y. Feasible advantage of bioactive/bioresorbable devices made of forged composites of hydroxyapatite particles and poly-L-lactide in alveolar bone augmentation: a preliminary study. Int J Med Sci. 2019;16:311–317. doi: 10.7150/ijms.27986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Shibata A, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Sakaida K, Furuki Use of the bioactive resorbable plate system for zygoma and zygomatic arch replacement and fixation in modified Crockett’s method for maxillectomy: a technical note. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:47–50. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Manabe Y, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Masui M, Furuki Y. Biomechanical loading evaluation of unsintered hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide plate system in bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy. Materials. 2017;10:764. doi: 10.3390/ma10070764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landes CA, Ballon A, Tran A, Ghanaati S, Sader R. Segmental stability in orthognathic surgery: hydroxyapatite/poly-L-lactide osteoconductive composite versus titanium miniplate osteosyntheses. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:930–942. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi M, Muramatsu H, Sato M, Tomizuka Y, Inoue M, Yoshimoto S. Surgical treatment of facial fracture by using unsintered hydroxyapatite particles/poly l-lactide composite device (OSTEOTRANS MX(®)): a clinical study on 17 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:783–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park H, Kim HS, Lee BI. Medial wall orbital reconstruction using unsintered hydroxyapatite particles/poly L-lactide composite implants. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2015;16:125–130. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2015.16.3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Furuki Y. Application of computer-assisted navigation systems in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Koyama Y, Shibata A, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Sakaida K, Tanaka S, Furuki Y. Intraoperative navigation-assisted surgical orbital floor reconstruction in orbital fracture treatment: a case report. Shimane J Med Sci. 2017;33:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong QN, Karino M, Koike T, Ide T, Okuma S, Kaneko I, Osako R, Kanno T. Navigation-assisted isolated medial orbital wall fracture reconstruction using an U-HA/PLLA sheet via a transcaruncular approach. J Invest Surg. 2019;15:1–9. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2018.1546353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohyama K, Morishima Y, Arisawa K, Arisawa Y, Kato H. Immediate and long-term results of unsintered hydroxyapatite and poly L-lactide composite sheets for orbital wall fracture reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71:1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevans SE, Moe KS. Advances in the reconstruction of orbital fractures. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:513–535. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grob SR, Yoon MK. Innovations in orbital surgical navigation, orbital implants, and orbital surgical training. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2017;57:105–115. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Koyama Y, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Masui M, Tanaka S, Furuki Y. Precision of post-traumatic orbital reconstruction using unsintered hydroxyapatite particles/poly-L-lactide composite bioactive/resorbable mesh plate with and without navigation: a retrospective study. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2017;26:274–280. doi: 10.2485/jhtb.26.274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doll C, Thieme N, Schönmuth S, Voss JO, Nahles S, Beck-Broichsitter B, Heiland M, Raguse JD. Enhanced radiographic visualization of resorbable foils for orbital floor reconstruction: a proof of principle. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]