Abstract

Gastroduodenal disease (GDD) was initially thought to be uncommon in Africa. Amongst others, lack of access to optimal health infrastructure and suspicion of conventional medicine resulted in the reported prevalence of GDD being significantly lower than that in other areas of the world. Following the increasing availability of flexible upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy, it has now become apparent that GDD, especially peptic ulcer disease (PUD), is prevalent across the continent of Africa. Recognised risk factors for gastric cancer (GCA) include Helicobater pylori (H. pylori), diet, Epstein-Barr virus infection and industrial chemical exposure, while those for PUD are H. pylori, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-use, smoking and alcohol consumption. Of these, H. pylori is generally accepted to be causally related to the development of atrophic gastritis (AG), intestinal metaplasia (IM), PUD and distal GCA. Here, we perform a systematic review of the patterns of GDD across Africa obtained with endoscopy, and complement the analysis with new data obtained on pre-malignant gastric his-topathological lesions in Accra, Ghana which was compared with previous data from Maputo, Mozambique. As there is a general lack of structured cohort studies in Africa, we also considered endoscopy-based hospital or tertiary centre studies of symptomatic individuals. In Africa, there is considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence of PUD with no clear geographical patterns. Furthermore, there are differences in PUD within-country despite universally endemic H. pylori infection. PUD is not uncommon in Africa. Most of the African tertiary-centre studies had higher prevalence of PUD when compared with similar studies in western countries. An additional intriguing observation is a recent, ongoing decline in PUD in some African countries where H. pylori infection is still high. One possible reason for the high, sustained prevalence of PUD may be the significant use of NSAIDs in local or over-the-counter preparations. The prevalence of AG and IM, were similar or modestly higher over rates in western countries but lower than those seen in Asia. . In our new data, sampling of 136 patients in Accra detected evidence of pre-malignant lesions (AG and/or IM) in 20 individuals (14.7%). Likewise, the prevalence of pre-malignant lesions, in a sample of 109 patients from Maputo, were 8.3% AG and 8.3% IM. While H. pylori is endemic in Africa, the observed prevalence for GCA is rather low. However, cancer data is drawn from country cancer registries that are not comprehensive due to considerable variation in the availability of efficient local cancer reporting systems, diagnostic health facilities and expertise. Validation of cases and their source as well as specificity of outcome definitions are not explicit in most studies further contributing to uncertainty about the precise incidence rates of GCA on the continent. We conclude that evidence is still lacking to support (or not) the African enigma theory due to inconsistencies in the data that indicate a particularly low incidence of GDD in African countries.

Keywords: Gastroduodenal, Peptic ulcer, Gastric cancer, Africa, Pre-malignant, Atrophy, Intestinal metaplasia, Duodenal ulcer, Gastric ulcer

Core tip: Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is not uncommon in Africa. There is considerable heterogeneity in its prevalence with no clear geographical patterns. There are further differences in PUD within-country despite endemic Helicobater pylori infection. Most African tertiary-centre studies have higher prevalence of PUD when compared with western countries. One possible reason for its sustained prevalence is the significant use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in local preparations. The prevalence of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia were similar or modestly higher over western countries but lower than those seen in Asia. Contrastingly, a comparatively low prevalence for gastric cancer is usually observed in African centres, although these rates might be underestimated.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroduodenal disease (GDD) was initially thought to be uncommon in Africa because of the lack of clinical data and the reported rarity of peptic ulcer surgery[1]. Suspicion of conventional medicine was also considered commonplace in some regions of Africa[2]. For instance, a study on the prevalence of dyspepsia in rural Northeastern Nigeria demonstrated that over 50% of dyspeptic patients sought medical help mainly from traditional healers[2]. These observations and tendancies are thought to have resulted in the reported prevalence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer (GCA) in Africa being significantly lower than that in other areas of the world[3].

The standard of care for diagnosis of PUD is typically through upper gastro-intestinal (GI) endoscopy with biopsy of any mucosal abnormality, including abnormal ulceration or polypoid lesion, a procedure that is also required for histopathological diagnosis of GCA. Imaging with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging and endoscopic ultrasound, where available, are additional procedures to stage cancer for prognostic purposes. In most African countries, patients present at late disease stages because of the lack of universal access to optimal health infrastructure and varying culturally-influenced health seeking behaviour[2,4]. This subsequently leads to a variety of empirical therapies for symptomatic individuals further delaying definitive diagnosis, and thereby contributing to the observed low prevalence of GDD in some areas[1,5]. Following the increasing availability of flexible upper GI endoscopy over recent years, it has now become apparent that GDD is prevalent across the continent of Africa[1,3]. Currently, in Ghana, there are endoscopic services and CT scan facilities in tertiary medical centres but not at most regional or district hospitals. The same situation is observed in Mozambique, where endoscopy services and CT scan is only available in the four central hospitals of the country. Despite some resources, there is still a lot to be done in improving healthcare coverage for many patients with GDD. His-tological data on GCA is scarce in Africa, yet there is significant data being reported on histopathological lesions which are risk factors for development of GCA, such as atrophic gastritis (AG) and intestinal metaplasia (IM)[4].

Recognised risk factors for GCA include Helicobater pylori (H. pylori), diet, lifestyle preferences, Epstein-Barr virus and industrial chemical exposure[6], while those for PUD are H. pylori, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-use, smoking and alcohol consumption[7]. Of these, H. pylori infection is generally accepted to be causally related to the development of AG, IM and gastric and duodenal ulceration as well as distal GCA[8,9]. The majority of patients with duodenal ulcer (DU) are infected with H. pylori. Distal GCA is strongly associated with lifelong H. pylori infection and relative socio-economic deprivation[10]. Proximal GCA has rather been linked to smoking, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, obesity and medium-high socio-economic status[10]. Although infection is universally associated with gastritis, the development into a broad spectrum of clinical and endoscopic outcomes is dependent on a number of factors, including the susceptibility of the host, the virulence of the infecting strain, and environmental co-factors[11]. In Africa the association of H. pylori infection with GDD is rather complex; the infection has a high prevalence across the continent (80%-95%) irrespective of the period of birth[12]. However, there appears to be a low overall incidence of GCA, a situation that is known as the African enigma[10]. There is also a variable distribution of incidence of GDD in Africa which does not necessarily mirror the prevalence of H. pylori. For instance, in Western Africa, the prevalence of DU has been reported to be lower in the northern savannah in comparison with the coastal areas. Both regions have similar prevalence of H. pylori infection[13,14]. In addition, the lack of population-based longitudinal studies also makes it difficult to evaluate the strength of association of GDD with risk factors like H. pylori in Africa.

This review analyses the patterns of incidence of PUD, gastric histopathological lesions and GCA in Africa. We compare patterns of GDD obtained with endoscopy with new data obtained on pre-malignant gastric histopathological lesions in Accra Ghana and Maputo Mozambique; data in Accra, Ghana are newly presented in this review and lend support to the discussion on the concept of the H. pylori African enigma.

SOURCES

We performed a literature review using the online databases PubMed and African Journals online. Articles were considered if they had “gastro-duodenal disease”, “peptic ulcer”, “gastric cancer” and “Africa” or “an African country” as keywords in the search. In relation to the histopathology, another search was made using “pre-malignant lesions”, “gastric atrophy” and “intestinal metaplasia” as keywords. We did not identify purposely structured cohort studies to establish incidence of GDD and therefore studies were eligible for further analysis if they were endoscopy-based hospital or tertiary center studies of symptomatic or dyspeptic individuals referred for evaluation. The references and abstracts were checked to determine if they were eligible and to ensure they were comparable.

METHODS

Symptomatic individuals undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy based on clinical need were consecutively recruited at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, the major tertiary centre in Accra. Patients’ symptoms and endoscopic diagnoses were captured with the study questionnaire after informed consent. The H. pylori status of patients was determined by performing a rapid urease test (i.e., Campylobacter-Like Organism test) on gastric antral biopsy samples. Samples from the antrum, corpus and incisura angularis, as required by the updated Sydney system, were placed in separate specimen containers containing 10% formalin solution at endoscopy. H. pylori was identified by haematoxylin and eosin and warthin-starry staining and histologic gastritis was determined according to the updated Sydney system in the Histopathology Department, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester, United Kingdom. A sample was defined as being positive for H. pylori if a PCR product was obtained for either a housekeeping gene (ureI, yhpC, ppA)[15,16] or glmM[17] as previously described. Molecular studies were performed in the Department of Genetics, University of Leicester, United Kingdom.

PATTERNS OF PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE IN AFRICA

In Africa, there is considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence of DU and gastric ulcer (GU) across the regions of the continent with no clear geographical pattern of PUD incidence (Table 1). Furthermore, there are differences in peptic ulcer incidence within-country despite universally endemic H. pylori infection. In Ghana, Komfo-Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, which serves the central-northern regions, has a lower incidence of PUD in comparison with Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, which serves the Southern regions of Ghana, (Accra: DU 19.6% vs Kumasi: DU 3%)[18]. Two studies in Nigeria had discordant PUD incidence: In Ibadan, Southern Nigeria, DU incidence was 2.3% relative to GU 9.3%, while Northern Nigeria had higher DU incidence 6.8% but lower GU incidence 2.7%[19,20]. On the contrary, two separate tertiary health centres in Kenya, Nakuru and Nairobi, had similar DU incidence but different GU incidence (Nairobi: GU 8.5%, DU 9.8%; Nakuru: GU 1.9% DU 9.5%)[21]. We realize that these differences might be related with study characteristics such as age and gender distribution of the study population; or with intrinsic features related with study design[22]. However, mean age and sex differences were modest and did not reliably predict prevalence of PUD across these studies. For instance, a relatively low mean age was associated with both elevated and decreased PUD prevalence (e.g., compare Accra, Ghana with Nakuru, Kenya, Table 1). Similarly, male populations had both higher and lower prevalence of PUD (e.g. compare Accra, Uganda with Mbarara, Uganda; Table 1). Most of the African tertiary-center studies had higher prevalence of PUD when compared with similar studies in western countries such as the United States[23], Netherlands[24] and Italy[25], but the latter studies had considerably larger sample sizes (Table 1). Additionally, it is also worth noting that hospital-based endoscopic studies with relatively small sample sizes in Africa are more likely to suffer selection bias with more advanced clinical presentations[26]. Nevertheless, in an unselected community study in Lusaka, Zambia[27], PUD was comparable in prevalence to other western countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patterns of incidence of peptic ulcer disease in hospital-based endoscopic studies of dyspeptic patients

| Country | Year(s) of study | Mean age (yr) |

Males |

Females |

n |

Incidence rate (%) |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | DU | GU | Total | ||||

| Ibadan, Nigeria[19] | 2008-2009 | 49.2 ± 13.8 | 39 (45.3) | 47 (54.7) | 86 | 2.3 | 9.3 | 11.6 |

| Northern Nigeria[17] | 2012 | 49.5 ± 15 | 68 (46) | 80 (54) | 148 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 9.5 |

| Mbarara, Uganda[39] | 2014-2015 | 53.5 ± 17.8 | 110 (59.8) | 74 (40.2) | 184 | 3.8 | 7.6 | 11.4 |

| Accra, Ghana[75] | 1995-2002 | 43.7 ± 10.6 | 3777 (54.1) | 3200 (45.9) | 6977 | 19.6 | 5.0 | 24.6 |

| Kumasi, Ghana[18] | 2006-2011 | - | 1337 (43) | 1773 (57) | 3110 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 7.7 |

| Nairobi, Kenya[21] | 2011-2013 | 47.0 | 1368 (43.5) | 1779 (56.5) | 3147 | 9.8 | 8.5 | 18.3 |

| Nakuru, Kenya[21] | 2011-2013 | 42.0 | 1372 (46.7) | 1564 (53.3) | 2936 | 9.5 | 1.9 | 11.4 |

| Kilimanjaro, Tanzania[76] | 2009-2010 | Median: 48.0 | 99 (47.6) | 109 (52.4) | 208 | 18.3 | 5.8 | 24.1 |

| Lusaka, Zambia[27] | 1999-2002 | - | 79 (35.7) | 142 (64.3) | 221 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 3.6 |

| Rotterdam, Netherlands[24] | 1996-2005 | 55.6 ± 17.9 | 9222 (46.1) | 10,784 (53.9) | 20006 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 5.9 |

| Rome, Italy[25] | 2005-2007 | Median: 62.5 | - | - | 11148 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.7 |

| United States[23] | 1996-2005 | - | - | - | 6438 | - | - | 1.5-3.0 |

DU: Duodenal ulcer; GU: Gastric ulcer.

Globally, PUD incidence has decreased over recent decades. This has been demonstrated by several population-based prospective studies in Europe (Netherlands[28], Spain[29], Belgium[30], United Kingdom[31]), North America (United States[32]) and Asia (India[33], Hong Kong[34], Taiwan[35]). Time trend prospective studies are however scarce in Africa. A retrospective descriptive study reported on patients who underwent upper GI endoscopy in the endoscopy unit of Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, between January 2000 and December 2010[36]. Over the study period, 292 patients (15.8%) were diagnosed with DU. The prevalence of DU for 2000-2004 was 22.9% (n = 211 patients) compared with 9.2% (n = 81) for 2005-2010 (P < 0.001)[36]. These prevalence rates were much lower than the 38.7% reported by Ndububa et al[37] for the years 1992-1999 at the same institution. In Uganda, two separate cross-sectional studies also showed reduction in DU prevalence from 18% in 2005[38] to 3.8% in 2014[39].

Overall, the data shows that the incidence of PUD has declined in many countries. Most likely this phenomenon is a result of the decrease in H. pylori infection, particularly in Western populations[40]. However, it is unclear the reasons for the decline in some African countries where H. pylori infection rates are still high. Management of PUD has improved substantially due to implementation of therapies for H. pylori and the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) which are increasingly accessible globally. The continued occurrence of PUD is increasingly due, at least in part, to the widespread use of low-dose aspirin and NSAIDs, especially in Western countries and among older patients[37,40]. A cross-sectional study of 242 dyspeptic patients in Accra, Ghana, evaluated the endoscopic spectrum of disease at a major tertiary centre[3]. A third (32.6%) of the study patients had a history of NSAID-use, especially as ingredients in local over-the-counter medicinal/herbal preparations[3]. In this study in Accra, there was an increased prevalence of DU in H. pylori-infected patients taking NSAIDs[3]. NSAID-use may therefore contribute to the varying PUD prevalence between and within countries in a H. pylori endemic continent such as Africa.

GASTRIC HISTOPATHOLOGY IN DYSPEPTIC PATIENTS

Gastric atrophy is an established risk factor for GCA[41]. Additionally, the risk of GCA increases with a greater extent and higher degree of AG[42]. Further studies suggest that IM is also a risk factor for GCA[43,44]. Pre-malignant lesions, AG and IM, are not uncommon in tertiary center studies of symptomatic patients undergoing endoscopy in Africa. Excluding the 2007 study in Kenya by Kalebi et al[4], which detected an AG rate of 57%, most hospital-based endoscopic studies have shown prevalence rates of AG of 5%-38% and for IM of 4%-32% across populations in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 2). These values were either similar to or had a modestly higher prevalence as compared to rates in western countries (e.g., Sweden, Finland or United States) but lower than those seen in Asia (Korea, China) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospital-based endoscopic studies of pre-malignant lesions

| Country | Study population | n | Gastric atrophy frequency (%) | Intestinal metaplasia frequency (%) |

| Cote d’Ivoire, Attia et al[77], 2001 | Dyspeptic patients | 137 | - | 19 |

| Sudan, El-Mahdi et al[78], 1998 | Dyspeptic H. pylori infected patients | 78 | 37 | 4 |

| Egypt, Abdel-Wahab et al[79], 1996 | DU patients | 43 | - | 26 |

| Gambia, Campbell et al[80], 2001 | Dyspeptic patients | 45 | 10 | 12 |

| Uganda, Wabinga et al[81], 2005 | Dyspeptic patients | 114 | 17 | 7 |

| Kenya, Kalebi et al[82], 2007 | Dyspeptic patients | 71 | 57 | 11 |

| Nigeria, Ndububa et al[83], 2007 | DU and GC patients | 115 | - | 32 GC |

| 16 DU | ||||

| Jos, Nigeria, Tanko et al[52], 2008 | Dyspeptic patients | 100 | 38 | 28 |

| Nigeria, Badmos et al[84], 2009 | Dyspeptic patients | 1047 | 5 | 9 |

| Tunisia, Jmaa et al[85], 2010 | Dyspeptic patients | 352 | 35 | 11 |

| Ilorin, Nigeria, Badmos et al[86], 2010 | Dyspeptic patients | 57 | 32 | 9 |

| Maputo, Mozambique Carrilho et al[46], 2009 | Dyspeptic patients | 109 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| United States, Almouradi et al[87], 2013 | Symptomatic individuals | 437 | - | 15.01 |

| Finland, Eriksson et al[88], 2008 | Symptomatic individuals | 505 | - | 18.8 (antrum) |

| 7.1 (body) | ||||

| Sweden, Borch et al[89], 2000 | Symptomatic individuals | 501 | 9.41 | |

| Korea, Kim et al[90], 2008. | Symptomatic individuals | 713 | 42.7 (antrum) | 42.5 (antrum) |

| 38.1 (body) | 32.7 (body) | |||

| China, Zou et al[91], 2011 | Symptomatic individuals | 1,022 | 63.81 | |

| Japan, Sakitani et al[47], 2011 | Symptomatic individuals | 1395 | - | 17.2 (antrum) |

| 10.8 (body) |

Prevalence of gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia in the antrum and/or body. DU: Duodenal ulcer; GU: Gastric ulcer; H. pylori: Helicobater pylori.

Gastric histopathology in Accra, Ghana and Maputo, Mozambique: A comparative analysis

The updated Sydney system of classification of gastritis emphasizes the importance of combining topographical, morphological and aetiological information into a scheme that helps to generate reproducible and clinically useful information[45]. It includes biopsies at the antrum[2], body[2] and incisura angularis[1]. Two such H. pylori studies in Africa comprehensively evaluated gastric histopathology and its relationship with H. pylori infection and gastric diseases (Table 3). The first was a prospective descriptive study conducted at the Maputo Central Hospital, Mozambique that estimated the prevalence of H. pylori, chronic gastritis and IM in 109 consecutive dyspeptic patients who were eligible for upper GI endoscopy between 2005 and 2006[46]. The second was a new study at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH), Accra, during which clinical and histopathological assessments were performed on 136 dyspeptic patients referred for upper GI endoscopy at the major tertiary centre between 2015 and 2016. The results of this latter study and comparisons with the Mozambique dataset are presented here.

Table 3.

Gastric histopathological lesions at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana and Maputo Central Hospital, Mozambique

| Accra, Ghana | Maputo, Mozambique | |

| Total | 136 | 109 |

| Median age (yr) | 52 | 37 |

| Sex | n (%) | n (%) |

| Female | 61 (44.9) | 74 (67.9) |

| Male | 75 (55.1) | 35 (32.1) |

| H. pylori prevalence: | ||

| Histology | 54.4% | 62.4% |

| H. pylori prevalence: | ||

| PCR | 93.3% | 92.6% |

| Active inflammation | n (%) | n (%) |

| Antrum | 47 (34.6) | 57 (53.8) |

| Incisura | 45 (37.2) | 58 (54.2) |

| Body | 40 (29.9) | 21 (31.3) |

| Chronic inflammation | n (%) | n (%) |

| Antrum | 115 (84.6) | 100 (94.4) |

| Incisura | 97 (80.2) | 99 (92.5) |

| Body | 97 (72.4) | 57 (85.1) |

| Pattern of gastritis | n (%) | n (%) |

| antral-predominant | 51 (37.5) | 54 (49.5) |

| Pangastritis (antrum and body) | 70 (51.5) | 45 (41.3) |

| Gastric atrophy | n (%) | n (%) |

| Antrum | 5 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Incisura | 7 (5.8) | 6 (6.2) |

| Body | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.5) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | n (%) | n (%) |

| Antrum | 10 (7.3) | 4 (3.8) |

| Incisura | 6 (5.0) | 7 (6.5) |

| Body | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pre-malignant lesions | n (%) | n (%) |

| Gastric atrophy and/or intestinal metaplasia | 20 (14.7) | 15 (13.8) |

H. pylori: Helicobater pylori.

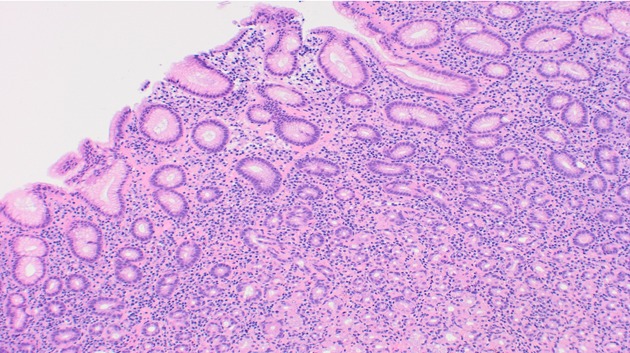

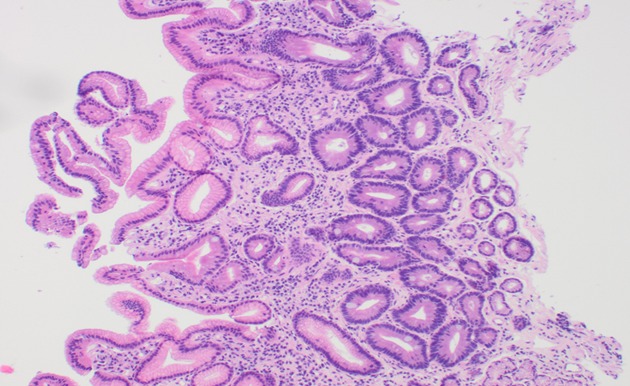

Overall, the commonest histologic diagnosis in both centres was chronic inflammation (i.e., 84.6% in Accra and 90.8% in Mozambique) irrespective of location in the stomach[46]. Chronic infiltrates were detected in more than twice as many patients as opposed to active inflammation with neutrophilic activity, (Figure 1). Of the 136 patients sampled in Accra, 20 (14.7%) had evidence of pre-malignant lesions (atrophy and/or IM). The majority showed mild gastric atrophy 6/9 (66.7%; T1 score) or IM 10/16 (62.5%; M1 score), respectively, (see Table 4 for the overview data and Figure 2 for an exemple of the tissue staining). Likewise, the prevalence of pre-malignant lesions, in a sample of 109 patients from Maputo, were 8.3% AG and 8.3% IM. Most of which were located distally, in the antrum or incisura angularis[46], as seen in KBTH, Accra. A study in Japan evaluated for gastric histopathological differences between antrum and body in 1395 patients, in a country where endoscopy is very accessible to patients due to high incidence of GCA[47]. This study reported the prevalence of IM as 17.2% and 10.8% in antrum and body respectively. IM in this Japanese study was considerably higher than that seen in Accra, Maputo and most African tertiary centre studies (Table 2) where gastric pathology may be rather over-represented. Interestingly, in Finland, an European country with low H. pylori prevalence and GCA incidence, IM in the body, 7.1%, was higher than that seen in Accra and Maputo. Overall, there was a higher prevalence of IM in the gastric body of Japanese samples as compared to the Accra, Maputo and Finland samples. This is important as IM in the gastric body has been identified as an independent risk factor for GCA following multi-variate analysis[47].

Figure 1.

Chronic gastritis affecting the mucosa of the gastric antrum (Haematoxylin and eosin stain; Magnification × 100).

Table 4.

Severity of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana (n = 136), as per updated Sydney system

|

Atrophy (n = 9) |

Metaplasia (n = 16) |

||

| Grade | n (%) | Grade | n (%) |

| T1 | 6 (66.7) | M1 | 10 (62.5) |

| T2 | 2 (22.2) | M2 | 5 (31.3) |

| T3 | 1 (11.1) | M3 | 1 (6.2) |

Figure 2.

Gastric antral mucosa showing atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and mild chronic inflammation (Haematoxylin and eosin stain; Magnification × 100).

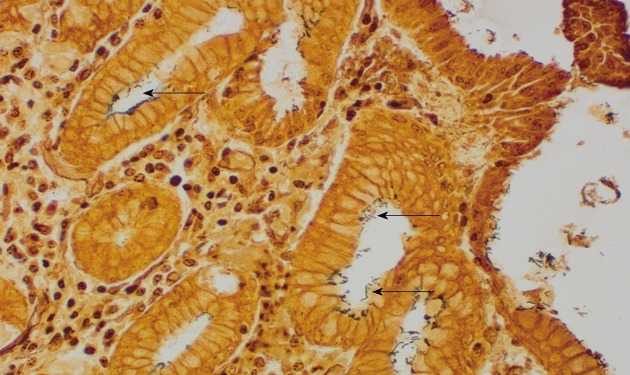

The prevalence of H. pylori in the sampled patients by histopathology in Accra was 54.4% with 74 out of 136 patients infected (see Table 3; and Figure 3 for a representative histopathological sample); whereas 93.3% had molecular evidence of H. pylori by PCR. Comparably, H. pylori was identified in 68 out of 109 cases (62.4%) based on histological assessment but 92.6% when assessed by PCR in the Mozambique study[46]. Furthermore, H. pylori was significantly more frequent when chronic inflammatory infiltrate, neutrophilic activity or degenerative surface epithelial damage were observed, regardless of the anatomic location[46]. It has been shown that H. pylori detection by histopathology may be more difficult in situations where the cellular environment may not be conducive for bacterial growth and/or when the bacterial load is very low. PCR is more sensitive as the grade of atrophy and/or IM progress toward malignancy[48]. Moreover, the accuracy of histopathology identification of H. pylori is affected by PPI and antibiotic use, which were not an exclusion criteria for these studies[49,50].

Figure 3.

Helicobacter pylori infection. The organisms are indicated with arrows (Warthin-Starry stain; Magnification × 400).

In Accra, demographically, patients with either gastric atrophy or IM were comparable but patients with pre-malignant lesions were more likely to be older than 50 years and male. However, no statistically significant differences were observed for the presence of IM and glandular atrophy according to H. pylori colonization in either Ghana or Mozambique[46]. In this histopathology study 3 (2.9%) patients had GCA in Accra with none represented in the Maputo study of 109 individuals. However, a recent study from Mozambique reported a prevalence of 1.5% from Maputo Central Hospital[51]. These low prevalence rates were comparable to similarly designed hospital-based studies in Nigeria (3.0%)[52] and Uganda (3.0%)[53].

Both studies (Accra and Maputo) demonstrated similar topographical distribution of H. pylori gastritis with antral involvement being the most common. In KBTH, Accra, antral gastritis was present in 89% (antral-predominant gastritis 37.5%, pan-gastritis (antrum and body) 51.5%, normal histology 11.0%). Chronic inflammation, lymphoid follicles, and neutrophilic activity were more frequent and of increased severity in the antrum and incisura than in the corpus[46]. There was no demonstrable significant relationship between the pattern of histologic gastritis and clinical gastric-duodenal disease. In general, the topographic distribution of acute H. pylori infection has been associated with specific gastro-duodenal phenotypes[54]. Infection of the antrum stimulates gastrin release which leads to increased acid production from parietal cells, resident mainly in the body[54]. This results in an elevated duodenal acid load, gastric metaplasia and subsequent duodenal ulceration[55]. On the other hand, patients with GU or GCA, have inflammation involving acid-secreting parietal cells of the body evolving with gastric atrophy and hypochlorhydria[56]. Essentially, an increase in acid secretion limits H. pylori gastritis to the antrum, increasing the risk of DU disease while a reduction in acid secretion allows more proximal inflammation and increases the risk of AG, GU, and GCA. Gastritis and atrophy negatively influence acid secretion[57]. Of note, both histopathologic studies demonstrate that antral inflammation was more common than body-gastritis in most infected individuals. As antral inflammation is known to be negatively associated with GCA[58], the high antral inflammation may explain the low prevalence of GCA in these populations.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF GASTRIC CANCER ACROSS SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

GCA remains an important cancer worldwide and was estimated to be responsible for over 1000000 new cases in 2018 and an estimated 783000 deaths, i.e., approximately 1 in every 12 deaths globally[59]. Consequentially it is the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality[59]. Age-standardized incidence rates are significantly elevated in Eastern Asia (45.3 per 100000 persons/year), when compared with rates in Northern America (7.6 per 100000 persons/year) and Northern Europe (9.3 per 100000 persons/year)[59]. These relatively low incidence rates are comparable to those seen across many regions of Africa (Table 5). The cumulative incidence rate up to and including an age of 74 years, expressed as a percentage of cancers of the stomach in sub-Saharan-Africa was 0.46% whereas the comparable worldwide rate was 1.39%[60].

Table 5.

Age-Standardized Incidence rates of gastric cancer in sub-Saharan Africa[60]

| Region | Years of study |

Age-standardized incidence rate (per 100000 person-years) |

Total | ||

| Males | Females | ||||

| Central Africa | |||||

| Congo, Brazzaville | 2009-2013 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 3.5 | |

| East Africa, Mainland | |||||

| Ethiopia, Addis Ababa | 2012-2013 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 5.2 | |

| Kenya, Eldoret | 2008-2011 | 9.8 | 7.9 | 17.7 | |

| Kenya, Nairobi | 2007-2011 | 9.2 | 9.7 | 18.9 | |

| Malawi, Blantyre | 2009-2010 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 7.9 | |

| Mozambique, Beira | 2009-2013 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.2 | |

| Uganda, Kampala | 2008-2012 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 9.7 | |

| Zimbabwe, Bulawayo | 2011-2013 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 10.5 | |

| Zimbabwe, Harare | 2010-2012 | 18.7 | 16.3 | 35.0 | |

| East Africa, Islands | |||||

| France Reunion | 2011 | 16.8 | 6.3 | 23.1 | |

| Mauritius | 2010-2012 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 10.2 | |

| Seychelles | 2009-2012 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 6.9 | |

| Southern Africa | |||||

| Botswana | 2005-2008 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 1.5 | |

| Namibia | 2009 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 7.0 | |

| South Africa, National | 2007 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 5.8 | |

| South Africa, East Cape | 2008-2012 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.2 | |

| Western Africa | |||||

| Benin, Cotonou | 2013-2015 | 11.3 | 2.4 | 13.7 | |

| Cote D’Ivoire, Abidjan | 2012-2013 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 5.6 | |

| The Gambia | 2007-2011 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 3.0 | |

| Guinea, Conakry | 2001-2010 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 7.5 | |

| Mali, Bamako | 2010-2014 | 19.1 | 15.3 | 34.4 | |

| Niger, Niamey | 2006-2009 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.8 | |

| Nigeria, Abuja | 2013 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 6.6 | |

| Nigeria, Calabar | 2009-2013 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.1 | |

| Nigeria, Ibadan | 2006-2009 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 4.1 | |

About 24000 new cases of stomach cancer and 22000 deaths were estimated to have occurred in 2002 in Africa, with three quarters (18000 new cases) occurring in sub-Saharan Africa[60]. The national cancer registries with the highest recorded cumulative incidence rates are Harare (Zimbabwe), Bamako (Mali), Kenya, Réunion (France), Rwanda and Uganda[60] (Table 5).

The significant decline in the incidence of non-cardia GCA in developed countries is an established phenomenon which is associated with improvements in food preservation and a decline in transmission of and infection by H. pylori[61]. On the contrary, no decrease was noted in rates of histologically diagnosed cases in South Africa between 1986 and 1995[60]. There is also no indication that the incidence of stomach cancer is declining in Africa; time trends for the cancer registries in Kampala (Uganda)[62], Harare (Zimbabwe)[63], and Bamako (Mali)[60] indicate little or no change in incidence during the past 20 years[60]. Notwithstanding, similar concerns remain about the data as encountered in the trends of PUD. In addition to late presentation and selection bias, cancer data in Africa is obtained from GLOBOCAN which is subsequently drawn from country cancer registries[4,26]. Such registries are not comprehensive due to considerable variation in the availability of efficient local cancer reporting systems or databases, essential diagnostic health equipment (endoscopy, histopathology, imaging) and expertise[26]. Validation of cases and their source as well as specificity of outcome definitions are not explicit in most studies further contributing to uncertainty about the precise incidence rates of GCA on the continent[4,22].

THE HELICOBACTER PYLORI AFRICAN ENIGMA

Helicobacter pylori infection is endemic in Africa, however GDD prevalence is reportedly low especially for GCA[64]. This phenomenon is referred to as the “African enigma”-a high prevalence of H. pylori with an apparently low incidence of GCA[13]. The concept was challenged based on the potential problems with the data upon which the theory was based. For example, in Africa, we cannot ignore major difficulties in access to healthcare, endoscopy and radiological examinations, all of which are deemed to have reduced the likelihood of a diagnosis of PUD and GCA[1]. On the contrary, patients with other common cancers such as oesophageal and cervical cancer are represented in hospitals in Africa so it remains curious why GCA patients would selectively not seek care[65].

Bacterial virulence has been studied to determine disease specific associations which might explain differences in GDD incidence across populations. Several studies in Africa have demonstrated that most H. pylori infections are of the virulent type as they were predominantly cagA and vacA s1 positive[66-68], therefore factors other than H. pylori virulence are likely of major importance in sub-Saharan Africa.

Environmental factors are essential in modulating H. pylori responses as well. There is a dietary component, with foods high in salt and low fruit intake increasing GCA risk. Both alcohol consumption and active tobacco smoking are also established risk factors[69,70]. Regular consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables seems to delay the onset of AG[71,72]. Further, co-infection of mice with Heligosomoides polygyrus, an extra-cellular mouse parasite, and Helicobacter felis has been shown to alter the immune response with down-regulation of Th1 dependent IgG2a serum antibody response to a greater extent than the Th2 dependent IgG1 antibody response leading to a reduction in H. pylori-induced gastric atrophy[73]. This suggests that other common infections in Africa might, likewise, affect the outcome of H. pylori infection. Differences in GCA rates between African countries and other parts of the world may accordingly be related to differences in intake of particular food, possibly co-existing infections or composition of gut microbiota. As with other infections, the natural history of H. pylori infection is determined by a range of microbe, host and environmental co-factors[74].

CONCLUSION

PUD and pre-malignant lesions are not uncommon in Africa when compared with the West despite contrasting H. pylori prevalence. However, lack of cohort studies drawn from the general population make accurate evaluation of incidence of GDD in Africa elusive. Additionally, the lack of a temporal relationship with incidence of risk factors, such as H. pylori infection, prevents an assessment of the strength of such risks. Tertiary center studies are heterogenous between and within-countries, subject to selection bias and may not be generalizable to the wider population. Therefore, longitudinal studies are required to elucidate how a myriad of environmental factors and gut microbiota (e.g., helminthic infections) act synergistically with host and H. pylori in expression of gastro-duodenal phenotype in African countries. Evidence is still lacking to support (or not) the African enigma theory, due to this theory being based on inconsistent data that indicate a particularly low incidence of GDD in African countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The new work presented here was supported by University of Ghana Research fund URF/5/ILG-003/2011-2012 to Timothy N Archampong and by the Medical Research Council UK with grant MR/M01987X/1 to Sandra Beleza. We are grateful to Dr. Rafiq Okine for his assistance in statistical analysis of the histopathological data.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Ghana

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good):C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: April 30, 2019

Article in press: June 1, 2019

P-Reviewer: Hirata Y, Savopoulos CG S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Timothy N Archampong, Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Ghana, Accra Box 4236, Ghana; Department of Genetics and Genome Biology, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, United Kingdom. tarchampong@ug.edu.gh.

Richard H Asmah, Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, University of Ghana, Accra Box 4236, Ghana.

Cathy J Richards, Department of Histopathology, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester LE1 5WW, United Kingdom.

Vicki J Martin, Department of Histopathology, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester LE1 5WW, United Kingdom.

Christopher D Bayliss, Department of Genetics and Genome Biology, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, United Kingdom.

Edília Botão, Department of Pathology, Maputo Central Hospital, Maputo POBox 1164, Mozambique.

Leonor David, Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty of the University of Porto, Porto 4200-465, Portugal; Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology at the University of Porto (Ipatimup), Porto 4200-465, Portugal; Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde (i3S), University of Porto, Porto 4200-465, Portugal.

Sandra Beleza, Department of Genetics and Genome Biology, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH, United Kingdom.

Carla Carrilho, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo POBox 257, Mozambique; Department of Pathology, Maputo Central Hospital, Maputo POBox 1164, Mozambique.

References

- 1.Agha A, Graham DY. Evidence-based examination of the African enigma in relation to Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:523–529. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holcombe C, Omotara BA, Padonu MK, Bassi AP. The prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in north eastern Nigeria. A random community based survey. Trop Geogr Med. 1991;43:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archampong TN, Asmah RH, Wiredu EK, Gyasi RK, Nkrumah KN. Factors associated with gastro-duodenal disease in patients undergoing upper GI endoscopy at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:611–619. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asombang AW, Kelly P. Gastric cancer in Africa: What do we know about incidence and risk factors? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKENZIE MB. Peptic ulceration in the African of Durban. S Afr Med J. 1957;31:1041–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Stomach Cancer, 2016. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Stomach-Cancer-2016-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenstock S, Jørgensen T, Bonnevie O, Andersen L. Risk factors for peptic ulcer disease: A population based prospective cohort study comprising 2416 Danish adults. Gut. 2003;52:186–193. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park YH, Kim N. Review of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia as a premalignant lesion of gastric cancer. J Cancer Prev. 2015;20:25–40. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2015.20.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: A combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atherton JC. The clinical relevance of strain types of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1997;40:701–703. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pounder RE, Ng D. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in different countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 2:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holcombe C. Helicobacter pylori: The African enigma. Gut. 1992;33:429–431. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tovey FI, Tunstall M. Duodenal ulcer in black populations in Africa south of the Sahara. Gut. 1975;16:564–576. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.7.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achtman M, Azuma T, Berg DE, Ito Y, Morelli G, Pan ZJ, Suerbaum S, Thompson SA, van der Ende A, van Doorn LJ. Recombination and clonal groupings within Helicobacter pylori from different geographical regions. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:459–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu JJ, Perng CL, Shyu RY, Chen CH, Lou Q, Chong SK, Lee CH. Comparison of five PCR methods for detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in gastric tissues. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:772–774. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.772-774.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyedu A, Yorke J. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the patient population of Kumasi, Ghana: Indications and findings. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:327. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.327.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jemilohun AC, Otegbayo JA, Ola SO, Oluwasola OA, Akere A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia in Ibadan. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;6:18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bojuwoye ABO, Ibrahim Olatunde O K, Ogunlaja Ayotunde O BJB. Relationship between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Endoscopic Findings among Patients with Dyspepsia in North Central, Nigeria. Sudan JMS. 2016;11:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makanga W, Nyaoncha A. Upper Gastrointestinal Disease in Nairobi and Nakuru Counties, Kenya; A Two Year Comparative Endoscopy Study. Ann Afric Surg. 2014;11:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin KJ, García Rodríguez LA, Hernández-Díaz S. Systematic review of peptic ulcer disease incidence rates: Do studies without validation provide reliable estimates? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:718–728. doi: 10.1002/pds.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manuel D, Cutler A, Goldstein J, Fennerty MB, Brown K. Decreasing prevalence combined with increasing eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States has not resulted in fewer hospital admissions for peptic ulcer disease-related complications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1423–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groenen MJ, Kuipers EJ, Hansen BE, Ouwendijk RJ. Incidence of duodenal ulcers and gastric ulcers in a Western population: Back to where it started. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:604–608. doi: 10.1155/2009/181059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Zullo A, Di Giulio E, Hassan C, Corleto VD, Lahner E, Annibale B. Low prevalence of idiopathic peptic ulcer disease: An Italian endoscopic survey. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:773–776. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asombang AW, Rahman R, Ibdah JA. Gastric cancer in Africa: Current management and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3875–3879. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernando N, Holton J, Zulu I, Vaira D, Mwaba P, Kelly P. Helicobacter pylori infection in an urban African population. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1323–1327. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1323-1327.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Post PN, Kuipers EJ, Meijer GA. Declining incidence of peptic ulcer but not of its complications: A nation-wide study in The Netherlands. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1587–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez-Aisa MA, Del Pino D, Siles M, Lanas A. Clinical trends in ulcer diagnosis in a population with high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartholomeeusen S, Vandenbroucke J, Truyers C, Buntinx F. Time trends in the incidence of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis between 1994 and 2003. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:497–499. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai S, García Rodríguez LA, Massó-González EL, Hernández-Díaz S. Uncomplicated peptic ulcer in the UK: Trends from 1997 to 2005. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1039–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis JD, Bilker WB, Brensinger C, Farrar JT, Strom BL. Hospitalization and mortality rates from peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding in the 1990s: Relationship to sales of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acid suppression medications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2540–2549. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dutta AK, Chacko A, Balekuduru A, Sahu MK, Gangadharan SK. Time trends in epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease in India over two decades. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2012;31:111–115. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia B, Xia HH, Ma CW, Wong KW, Fung FM, Hui CK, Chan CK, Chan AO, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Wong BC. Trends in the prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori infection in family physician-referred uninvestigated dyspeptic patients in Hong Kong. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu CY, Wu CH, Wu MS, Wang CB, Cheng JS, Kuo KN, Lin JT. A nationwide population-based cohort study shows reduced hospitalization for peptic ulcer disease associated with H pylori eradication and proton pump inhibitor use. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ijarotimi O, Soyoye DO, Adekanle O, Ndububa DA, Umoru BI, Alatise OI. Declining prevalence of duodenal ulcer at endoscopy in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. S Afr Med J. 2017;107:750–753. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i9.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ndububa DA, Agbakwuru AE, Adebayo RA, Olasode BJ, Olaomi OO, Adeosun OA, Arigbabu AO. Upper gastrointestinal findings and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection among Nigerian patients with dyspepsia. West Afr J Med. 2001;20:140–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogwang DM. Dyspepsia: Endoscopy findings in Uganda. Trop Doct. 2003;33:175–177. doi: 10.1177/004947550303300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obayo S, Muzoora C, Ocama P, Cooney MM, Wilson T, Probert CS. Upper gastrointestinal diseases in patients for endoscopy in South-Western Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:959–966. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i3.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung JJ, Kuipers EJ, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the global incidence and prevalence of peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:938–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Correa P. Chronic gastritis: A clinico-pathological classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Vries AC, Kuipers EJ. Epidemiology of premalignant gastric lesions: Implications for the development of screening and surveillance strategies. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 2:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim N, Park RY, Cho SI, Lim SH, Lee KH, Lee W, Kang HM, Lee HS, Jung HC, Song IS. Helicobacter pylori infection and development of gastric cancer in Korea: Long-term follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:448–454. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046eac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrilho C, Modcoicar P, Cunha L, Ismail M, Guisseve A, Lorenzoni C, Fernandes F, Peleteiro B, Almeida R, Figueiredo C, David L, Lunet N. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia in Mozambican dyspeptic patients. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakitani K, Hirata Y, Watabe H, Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Maeda S, Omata M, Koike K. Gastric cancer risk according to the distribution of intestinal metaplasia and neutrophil infiltration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1570–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Martel C, Plummer M, van Doorn LJ, Vivas J, Lopez G, Carillo E, Peraza S, Muñoz N, Franceschi S. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction and histopathology for the detection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric biopsies. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:1992–1996. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JY, Kim N. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori by invasive test: Histology. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:10. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nasser SC, Slim M, Nassif JG, Nasser SM. Influence of proton pump inhibitors on gastritis diagnosis and pathologic gastric changes. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4599–4606. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carrilho C, Fontes F, Tulsidás S, Lorenzoni C, Ferro J, Brandão M, Ferro A, Lunet N. Cancer incidence in Mozambique in 2015-2016: Data from the Maputo Central Hospital Cancer Registry. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018 doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanko MN, Manasseh AN, Echejoh GO, Mandong BM, Malu AO, Okeke EN, Ladep N, Agaba EI. Relation between Helicobacter pylori, inflammatory (neutrophil) activity, chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11:270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newton R, Ziegler JL, Casabonne D, Carpenter L, Gold BD, Owens M, Beral V, Mbidde E, Parkin DM, Wabinga H, Mbulaiteye S, Jaffe H Uganda Kaposi's Sarcoma Study Group. Helicobacter pylori and cancer among adults in Uganda. Infect Agent Cancer. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5191–5204. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shiotani A, Graham DY. Pathogenesis and therapy of gastric and duodenal ulcer disease. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:1447–1466, viii. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Graham DY, Asaka M. Eradication of gastric cancer and more efficient gastric cancer surveillance in Japan: Two peas in a pod. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuipers EJ. Helicobacter pylori and the risk and management of associated diseases: Gastritis, ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11 Suppl 1:71–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.11.s1.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Jemal A, Borok M, Manraj SS, N’da GG, Ogunbiyi JO, Liu B, Bray F. 2018. Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. IARC Scientific Publications; pp. 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howson CP, Hiyama T, Wynder EL. The decline in gastric cancer: Epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev. 1986;8:1–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wabinga HR, Nambooze S, Amulen PM, Okello C, Mbus L, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in Kampala, Uganda 1991-2010. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:432–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chokunonga E, Borok MZ, Chirenje ZM, Nyakabau AM, Parkin DM. Trends in the incidence of cancer in the black population of Harare, Zimbabwe 1991-2010. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:721–729. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sitas F, Isaäcson M. Histologically diagnosed cancer in South Africa, 1987. S Afr Med J. 1992;81:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Segal I, Ally R, Mitchell H. Helicobacter pylori--an African perspective. QJM. 2001;94:561–565. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.10.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Breurec S, Michel R, Seck A, Brisse S, Côme D, Dieye FB, Garin B, Huerre M, Mbengue M, Fall C, Sgouras DN, Thiberge JM, Dia D, Raymond J. Clinical relevance of cagA and vacA gene polymorphisms in Helicobacter pylori isolates from Senegalese patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asrat D, Nilsson I, Mengistu Y, Kassa E, Ashenafi S, Ayenew K, Wadström T, Abu-Al-Soud W. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genotypes in Ethiopian dyspeptic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2682–2684. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2682-2684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mistry R, Berg D, Mukhopayay, Ally R, Segal I. Helicobacter pylori (Hp) virulence factors vacuolating cytotoxin gene (vacA) genotypes and cytotoxin associated gene A (cagA) in adult Sowetans. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:888. [Google Scholar]

- 69.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Personal habits and indoor combustions. Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100:1–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Cancer Research Fund International/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activityand Stomach Cancer 2016. Revised 2018. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Stomach-cancer-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Correa P. Diet modification and gastric cancer prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1992;(12):75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Byers T, Guerrero N. Epidemiologic evidence for vitamin C and vitamin E in cancer prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:1385S–1392S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1385S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fox JG, Beck P, Dangler CA, Whary MT, Wang TC, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat Med. 2000;6:536–542. doi: 10.1038/75015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer: A model. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1983–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aduful H, Naaeder S, Darko R, Baako B, Clegg-Lamptey J, Nkrumah K, Adu-Aryee N, Kyere M. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at the korle bu teaching hospital, Accra, Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:12–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ayana SM, Swai B, Maro VP, Kibiki GS. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic findings and prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among adult patients with dyspepsia in northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2014;16:16–22. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v16i1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Attia KA, N'dri Yoman T, Diomandé MI, Mahassadi A, Sogodogo I, Bathaix YF, Kissi H, Sermé K, Sawadogo A, Kassi LM. [Clinical, endoscopic and histologic aspects of chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis in Côte d'Ivoire: Study of 102 patients] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2001;94:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El-Mahdi AM, Patchett SE, Char S, Domizio P, Fedail SS, Kumar PJ. Does CagA contribute to ulcer pathogenesis in a developing country, such as Sudan? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:313–316. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abdel-Wahab M, Attallah AM, Elshal MF, Eldousoky I, Zalata KR, el-Ghawalby NA, Gad el-Hak N, el-Ebidy G, Ezzat F. Correlation between endoscopy, histopathology, and DNA flow cytometry in patients with gastric dyspepsia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1313–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Campbell DI, Warren BF, Thomas JE, Figura N, Telford JL, Sullivan PB. The African enigma: Low prevalence of gastric atrophy, high prevalence of chronic inflammation in West African adults and children. Helicobacter. 2001;6:263–267. doi: 10.1046/j.1083-4389.2001.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wabinga H. Helicobacter pylori and histopathological changes of gastric mucosa in Uganda population with varying prevalence of stomach cancer. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5:234–237. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2005.5.3.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalebi A, Rana F, Mwanda W, Lule G, Hale M. Histopathological profile of gastritis in adult patients seen at a referral hospital in Kenya. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4117–4121. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ndububa DA, Agbakwuru EA, Olasode BJ, Aladegbaiye AO, Adekanle O, Arigbabu AO. Correlation between endoscopic suspicion of gastric cancer and histology in Nigerian patients with dyspepsia. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Badmos KB, Ojo OS, Olasode OS, Arigbabu AO. Gastroduodenitis and Helicobacter pylori in Nigerians: Histopathological assessment of endoscopic biopsies. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jmaa R, Aissaoui B, Golli L, Jmaa A, Al QJ, Ben SA, Ziadi S, Ajmi S. [The particularity of Helicobacter pylori chronic gastritis in the west center of Tunisia] Tunis Med. 2010;88:147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Badmos KB, Olokoba AB, Ibrahim OO, Abubakar-Akanbi SK. Histomorphology of Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis in Ilorin. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2010;39:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Almouradi T, Hiatt T, Attar B. Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia in an Underserved Population in the USA: Prevalence, Epidemiologic and Clinical Features. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:856256. doi: 10.1155/2013/856256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eriksson NK, Kärkkäinen PA, Färkkilä MA, Arkkila PE. Prevalence and distribution of gastric intestinal metaplasia and its subtypes. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borch K, Jönsson KA, Petersson F, Redéen S, Mårdh S, Franzén LE. Prevalence of gastroduodenitis and Helicobacter pylori infection in a general population sample: Relations to symptomatology and life-style. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1322–1329. doi: 10.1023/a:1005547802121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim HJ, Choi BY, Byun TJ, Eun CS, Song KS, Kim YS, Han DS. [The prevalence of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia according to gender, age and Helicobacter pylori infection in a rural population] J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41:373–379. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2008.41.6.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zou D, He J, Ma X, Liu W, Chen J, Shi X, Ye P, Gong Y, Zhao Y, Wang R, Yan X, Man X, Gao L, Dent J, Sung J, Wernersson B, Johansson S, Li Z. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastritis: The Systematic Investigation of gastrointestinaL diseases in China (SILC) J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:908–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]