Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative process characterized by the accumulation of extracellular deposits of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ), which induces neuronal death. Monomeric Aβ is not toxic but tends to aggregate into β-sheets that are neurotoxic. Therefore to prevent or delay AD onset and progression one of the main therapeutic approaches would be to impair Aβ assembly into oligomers and fibrils and to promote disaggregation of the preformed aggregate. Albumin is the most abundant protein in the cerebrospinal fluid and it was reported to bind Aβ impeding its aggregation. In a previous work we identified a 35-residue sequence of clusterin, a well-known protein that binds Aβ, that is highly similar to the C-terminus (CTerm) of albumin. In this work, the docking experiments show that the average binding free energy of the CTerm-Aβ1–42 simulations was significantly lower than that of the clusterin-Aβ1–42 binding, highlighting the possibility that the CTerm retains albumin's binding properties. To validate this observation, we performed in vitro structural analysis of soluble and aggregated 1 μM Aβ1–42 incubated with 5 μM CTerm, equimolar to the albumin concentration in the CSF. Reversed-phase chromatography and electron microscopy analysis demonstrated a reduction of Aβ1–42 aggregates when the CTerm was present. Furthermore, we treated a human neuroblastoma cell line with soluble and aggregated Aβ1–42 incubated with CTerm obtaining a significant protection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. These in silico and in vitro data suggest that the albumin CTerm is able to impair Aβ aggregation and to promote disassemble of Aβ aggregates protecting neurons.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Amyloid, Albumin, β-Sheet, Docking

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; APP, amyloid precursor protein; Aß, Amyloid-ß peptide; CD, Circular dichroism; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CTerm, albumin C-terminus; fAβ1–42, HiLyte Fluor488 labelled human Aβ1–42; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; LC-MS, Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PDB, Protein Data Bank; PPI, protein-protein interactions; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; UV, ultraviolet

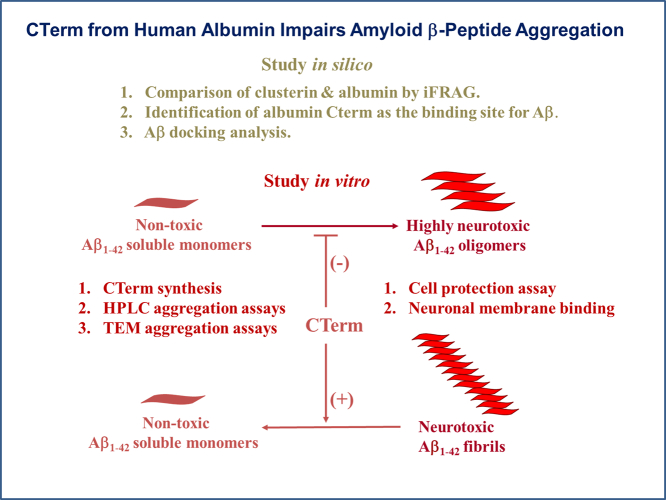

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Albumin binds amyloid with higher affinity than clusterin.

-

•

The albumin C-terminus retains the amyloid binding ability of the whole albumin.

-

•

The albumin C-terminus impairs amyloid assembly.

-

•

The albumin C-terminus favors the disassemble of amyloid aggregates.

-

•

The albumin C-terminus protects neurons against aggregated amyloid.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) histopathological hallmarks are the extracellular aggregation of amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) in the brain, and the intraneuronal aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein [1,2]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis proposes that Aβ aggregation into oligomers and fibrils induces synaptotoxicity and ultimately neuronal death [[3], [4], [5]].

The Aβ is a ~4 kDa peptide released from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) [6] by the sequential action of the enzymes β- and γ-secretases [7,8]. Aβ is produced thoughout the life of an individual, being physiologically degraded in the brain by different enzymes or cleared through the blood brain barrier into the blood [9]. During aging there is an increase in Aβ production and an impairment of Aβ clearance from brain to blood [10], favoring its aggregation into β-sheets. Then, Aβ forms oligomers known to be highly neurotoxic [3,4], and they progress into forming amyloid fibrils that are packed into senile plaques.

At present, AD prevalence is increasing as the world population ages [11] and has become a major health and social problem expected to reach pandemic status by 2050 [12]. Unfortunately, despite the current knowledge on APP processing, there are no treatments that effectively prevent AD development or its progression. On the other hand, the use of antibodies against Aβ to disassemble cerebral Aβ aggregates [[13], [14], [15]] has not yielded positive results in clinical trials.

Interestingly, clusterin (also termed apolipoprotein J) and albumin are cerebral proteins that have been reported to bind Aβ under physiological conditions [[16], [17], [18]]. In fact, clusterin impairs Aβ aggregation in the brain [16] and some clusterin polymorphisms are major risk factors for late onset AD [19]. Albumin has also been demonstrated to inhibit Aβ aggregation [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. These findings make the study of clusterin and albumin of high relevance to understand AD etiology and to elucidate mechanisms of neuroprotection in AD.

Albumin is the most abundant protein in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) produced mostly by ultrafiltrate of plasma proteins [24] and minimally by the microglia [25]. It is a single peptide chain of 585 amino acids with a secondary structure containing 67% α-helix, 23% extended chain and 10% β-sheet [[26], [27], [28]]. Albumin is a flexible molecule, with the ability to change its structure depending on environmental conditions such as temperature, pH or ionic strength [29,30]. It can bind a plethora of different molecules [[30], [31], [32], [33]], and it can even act as a free radical scavenger [34]. More specifically, albumin can bind Aβ [20,35,36] and is responsible for 95% of its transport in the blood [18,37,38], thereby regulating the amount of circulating Aβ.

Previously, we used the Protein-Protein Interface Prediction Server (iFRAG) to predict the interaction for short protein fragments and found that clusterin shares a common sequence with the C-terminus domain of human albumin (CTerm; Fig. S1) [39]. Here, we address the effect of its CTerm in Aβ aggregation using in silico and in vitro techniques.

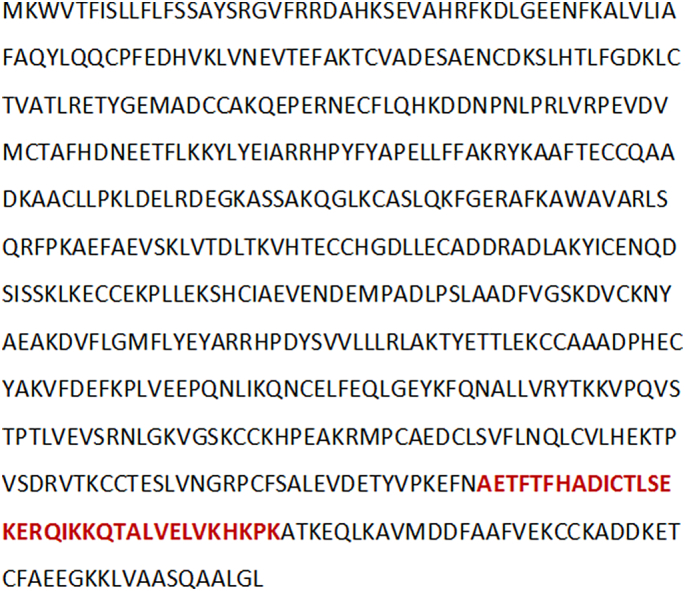

Fig. S1.

Sequence of human albumin. The sequence of the CTerm peptide is labelled in red.

Computational methods to predict and evaluate protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represent a feasible alternative to experimental approaches. Although docking experiments are currently used to predict the conformation of PPIs [40], it has been shown that the distribution of scores of different docking populations could be used to discern between interacting and non-interacting protein pairs. This is valid even when the native conformation cannot be identified among the poses [41] and the population of docking poses can be used to predict the binding energy if the structure of the complex is unknown [42]. In this work, we used similar principles to assess the binding potential of clusterin, albumin and the CTerm to the alpha and beta conformations of the Aβ1–42 peptide. We focused our efforts on elucidating the physiological relevance of the CTerm and its interaction with Aβ1–42 peptide by in vitro experiments using different techniques and cell cultures.

2. Methodology

2.1. Modeling of the Clusterin Peptide

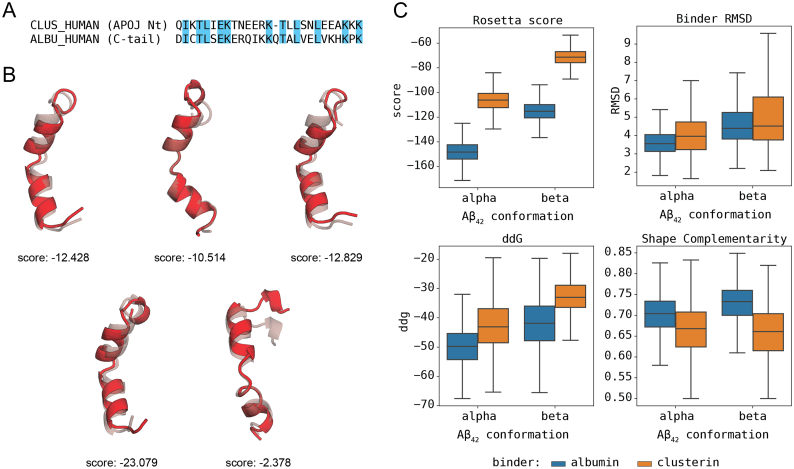

We found the four homologous sequences between clusterin and albumin in a previous work through sequence alignments [39]. Due to the lack of available structures for clusterin or the peptide region of interest, 5 decoys of the most promising peptide according to iFrag [39] were built with MODELLER [[43], [44], [45]] following the alignment shown in Fig. 1A. The five decoys were minimized and scored with Rosetta [46] and the best-scored decoy was selected as the structural representative of the clusterin-peptide (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

In silico modeling of clusterin and docking comparison with the CTerm. A) Guiding alignment for the modeling of the clusterin peptide. Common amino acids are labelled in blue. B) Structures of the 5 clusterin decoys with the initial models (transparent) and the minimized structure (red). Rosetta scores for the minimized structure are shown under each structure. C) Comparison of scores between the docking population of clusterin (or albumin) and the Aβ1–42 peptide (in α or β conformation). Using a total of 8000 decoys on each docking population, the scores of albumin peptides systematically outperforms those of clusterin when binding the same target, with a statistical significance of p < .001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Aβ1–42 -Docking Analyses

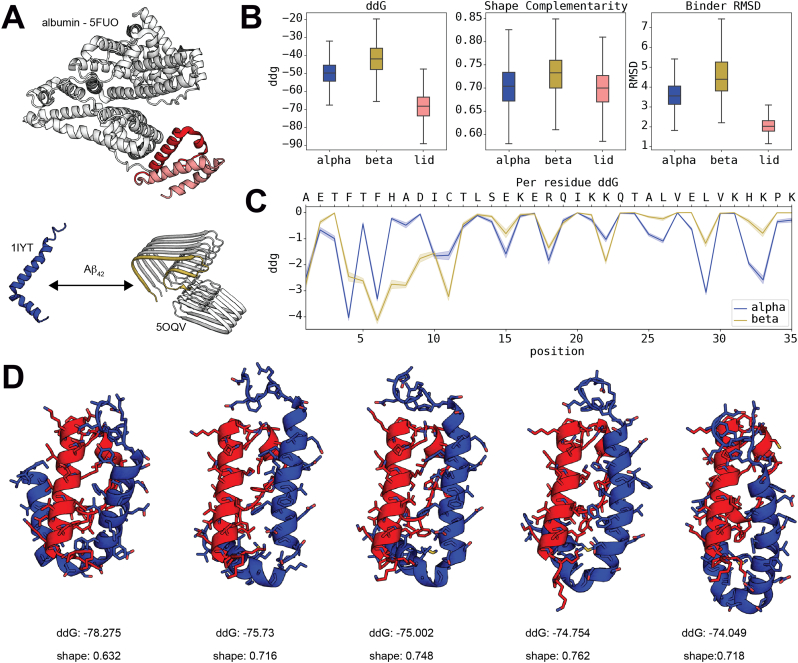

With the exception of the clusterin-peptide model, structures for all the different elements required for the docking analyse were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [47]. The clusterin-peptide and the CTerm structure (crystal structure PDB ID: 5FUO [48], residues 504-538) were docked with two different target binders: (1) the Aβ1–42 α conformation (nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) ensemble PDB ID: 1IYT [49]), (2) the Aβ1–42 β conformation (cryo-EM structure PDB ID: 5OQV [50]). Additionally, CTerm was also docked to the most terminal region of albumin (PDB ID: 5FUO, residues 539-582). to which is normally bound (CTerm-lid). This region of the wild-type albumin hides the putative recognition site between CTerm and Aβ1–42 (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Structural in silico analysis of Aβ1–42 interaction with the CTerm. A) Structure of human albumin. The sequence of the CTerm is labelled in red. The continuing structural segment (CTerm-lid) is shown in pink (top). The α and β configurations of Aβ1–42 are shown at the bottom. B) Scores distribution of the docking analysis of CTerm against α-Aβ1–42, β-Aβ1–42, and CTerm-lid. C) Individual contribution of the residues of the CTerm to the binding according to the top 200 decoys (2.5% of the total). D) Representation of the first five top-scored decoys of the docking between the amyloid peptide (blue) and the CTerm (red). ddG score and shape complementarity are provided under each structure. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

From the only two available NMR structures in the PDB [47] presenting the full 42 residues of the Aβ1–42 peptide, we selected 1IYT over 1Z0Q [doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.200500223] (see alignment of resolved residue densities for all Aβ1–42 peptides in the PDB at https://github.com/structuralbioinformatics/amyloid/blob/master/albumina/source/alpha_amyloids/alignment.highlight.aln) for two main reasons. On the one hand, most of the standard PDB metric qualities (namely clashscore, Ramachandran outliers and sidechain outliers) are far better in 1IYT than in 1Z0Q. On the other hand, 1Z0Q is described as an intermediate state between the α and β conformations of Aβ1–42 while 1IYT aims to represent the stable alpha state of the peptide.

For each pair, a total of 8000 decoys were generated with Rosetta's docking protocol [51] and optimized with Rosetta's FastRelax [52]. Decoys were analyzed in terms of their ddG, shape complementarity and structural variation of the target binder.

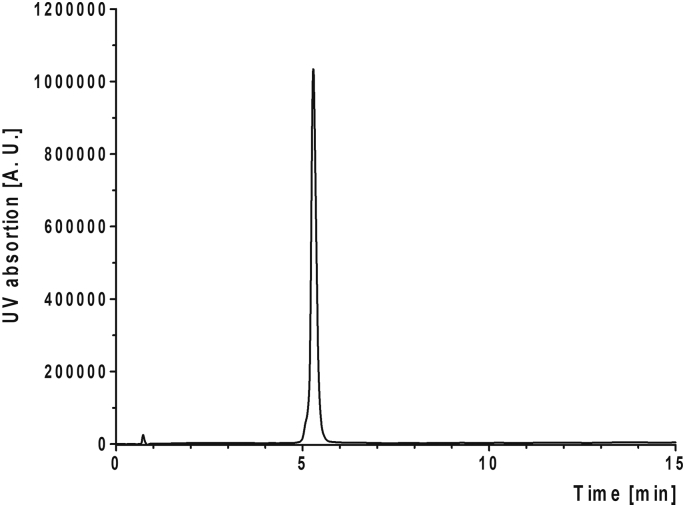

2.3. CTerm Synthesis

The CTerm peptide, AETFTFHADICTLSEKERQIKKQTALVELVKHKPK-amide, containing the hydrophobic domains reported to be Aβ binding sites by García et al. [39] was produced in C-terminal carboxamide form by Fmoc solid phase synthesis in a peptide synthesizer Prelude (Gyros Protein Technologies). It was purified to near homogeneity (97%) by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.4. CTerm Analysis

Analytical reversed-phase HPLC was performed on C18 columns (4.6 × 50 mm, 3 μm; Phenomenex) in a liquid chomatrograph (LC-2010A; Shimadzu). Solvent A was 0.045% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in H2O; solvent B was 0.036% TFA in acetonitrile. Elution was carried out with linear 15–50% gradients of solvent B into A over 15 min at 1 mL/min flow rate, with UV detection at 220 nm. LC-mass spectrometry (MS) was performed in a LC-MS 2010EV instrument (Shimadzu) fitted with an XBridge column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3.5 μm; Waters), eluted with a 15–50% linear gradient of B into A (A = 0.1% formic acid in H2O; B = 0.08% formic acid in acetonitrile) over 15 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, with UV detection at 220 nm.

2.5. CTerm Purification

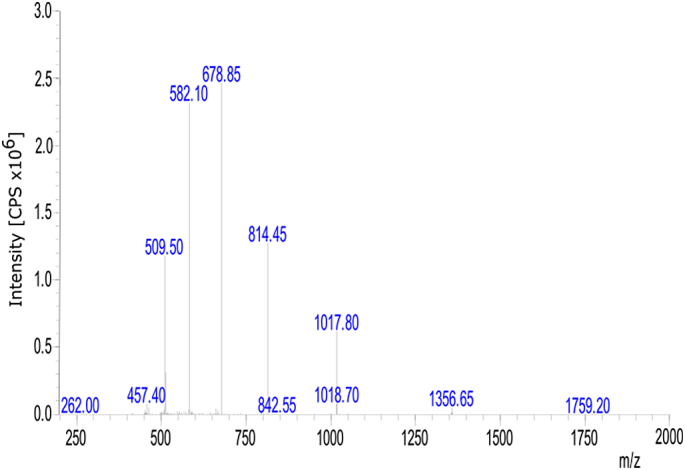

Preparative HPLC runs were performed on a Luna C18 column (21.2 mm × 250 mm, 10 μm; Phenomenex), using linear 15–50% gradients of solvent B (0.1% in acetonitrile) into A (0.1% TFA in H2O), as required, with a flow rate of 25 mL/min. Fractions of high (>95%) HPLC homogeneity were further characterized by electrospray mass spectrometry using a XBridge column C18 (Waters) and a gradient at 1 mL/min of A (0.1% formic acid in H2O) into B (0.08% formic acid in CH3CN). Detection was performed at 220 nm. Fractions of adequate homogeneity and with the expected mass (4067.77 Da) were combined, lyophilized, and used in subsequent experiments. See Fig. S2, Fig. S3 and Table S1 for additional details.

Fig. S2.

Chromatograph of CTerm by analytical HPLC. Chromatographic analysis was carried out at 220 nm for 15 min.

Fig. S3.

Characterization of CTerm by mass spectrometry. It was carried out with a LC-MS 2010EV (Shimadzu). CPS are counts per second.

2.6. Circular Dichroism (CD)

CTerm was dissolved in 5 mM NaOH at a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL. The peptide was further dissolved to yield a 50 mM concentration in 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 in the presence or absence of 20 mM SDS. The CD was performed as follows. The spectral region was recorded from 190 to 250 nm, with a 0.5 nm step resolution, on a Jasco J-715 CD spectropolarimeter (Jasco Inc.) using a quartz cell of 1.0 mm optical path length at room temperature. The scanning speed was 100 nm/min with 2 s time response, and the spectra were collected and averaged over 10 scans. Secondary structure estimation derived from CD data was assessed using K2D3 [53].

2.7. Amyloid Preparation

Lyophilized Aβ1–42 (Anaspec) was solubilized as previously described [54]. Briefly, 1 mg Aβ was dissolved in 250 μL of MilliQ water and pH was adjusted to ≥10.5 using 1 M NaOH solution to avoid the isoelectric point of Aβ disassembling and aggregates that may be present. Peptides were diluted in 250 μL of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Furthermore, the solutions were sonicated for 1 min in a bath-type sonicator (Bioruptor, Diagenode). The preparations were immediately used for aggregation or stored in 25 μL aliquots at −20 °C until used.

2.8. Reversed-Phase Chromatography Analysis of CTerm Effect on Aβ Aggregation

Soluble and pre-aggregated (24 h at 37 °C) 1 μM Aβ1–42 was dissolved in Ham's F12 medium and incubated in the presence/absence of 5 μM CTerm at 37 °C during 24 h for assembly and disassemble assays. Samples were quenched in 2% trifluoroacetic acid and injected in a Waters 2690 HPLC coupled to a UV detector set to 214 nm. A linear gradient of 25%–45% of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile was applied for 90 min into a 250 × 4.6 mm (5 μm) C4 column at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min.

2.9. Reversed-Phase Chromatography Analysis of Control Peptide Effect on Aβ Aggregation

Random peptides with the same size that CTerm were synthetized: peptides X, Y and Z. Soluble and pre-aggregated (24 h at 37 °C) 1 μM Aβ1–42 was dissolved in Ham's F12 medium and incubated in the presence/absence of 5 μM peptides at 37 °C during 24 h for assembly and disassemble assays. Analytical reversed-phase HPLC was performed on C18 columns (4.6 × 50 mm, 3 μm, Phenomenex) in a model LC-2010A system (Shimadzu). Solvent A was 0.045% TFA in H2O; solvent B was 0.036% TFA in acetonitrile. Elution was carried out with linear 5–95% gradients of solvent B into A over 15 min at 1 mL/min flow rate, with UV detection at 220 nm.

2.10. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Soluble and pre-aggregated (24 h at 37 °C) 1 μM Aβ1–42 was dissolved in Ham's F12 medium and incubated in the presence/absence of 5 μM CTerm at 37 °C during 24 h for assembly and disassemble assays. Samples of aggregated peptides obtained as described above were placed onto carbon-coated 200 mesh copper grids and incubated for 5 min. The grids were washed with distilled water and negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 2 min. Micrographs were obtained in a JEM-1010 (JEOL) transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV accelerating voltage and equipped with an Orius CCD camera.

2.11. Cell Viability Assay by MTT Reduction

A human neuroblastoma cell line (SH-SY5Y cells) was seeded in poly-l-lysine coated 96-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells/well. Soluble and pre-aggregated (24 h at 37 °C) 1 μM Aβ1–42 was dissolved in Ham's F12 medium and incubated in the presence/absence of 5 μM CTerm at 37 °C during 24 h for assembly and disassemble assays. After they were ready the samples were added. Cells were treated with the different samples during 24 h at 37 °C. Cell viability was tested by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction. 10% v/v of MTT stock solution (5 mg/mL) was added. After 2 h the media was replaced with 100 μL of dimethylsulfoxide. MTT absorbance was determined in an Infinite 200 multiplate reader at A540 nm and corrected by A650 nm. Data are shown compared to untreated controls (100%).

2.12. Aβ1–42 Binding to Neuronal Processes

Primary cultures were carried out as previously reported [4]. The procedure was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institut Municipal d'Investigacions Mèdiques-Universitat Pompeu Fabra (EC-IMIM-UPF). Cortical neurons were isolated from 18-day-old OF1 mouse embryos. The brain was removed and the cortex aseptically dissected on ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose and trypsinized for 17 min at 37 °C. In order to eliminate rests of the trypsinization medium and to disaggregate the cells, the cell solution was washed thrice in Hanks' balanced salt solution+glucose and mechanically dissociated. Then, cells were seeded on poly-d-lysine coated coverslips in 24 well-plates with DMEM medium plus 10% horse serum at 105 cells/well. Once neurons were attached to the polylysinated wells (2 h), the seeding medium was removed and Neurobasal medium was added containing 2% B27 supplement, 1% GlutaMAX and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. On day 3 of in vitro culture, cells were treated with 2 μM 1-β-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine for 24 h to eliminate glia. Primary cortical neurons were used at day 10 [15]. Cells were treated for 10 min at room temperature in mild agitation with 10 μM HiLyte Fluor488 labelled human Aβ1–42 (fAβ1–42) preformed in the presence/absence of 20 μM CTerm. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) cells were incubated on ice with 75 μg/mL red concanavaline in neurobasal medium for 20 min. Then cells were washed again in cold PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS before mounting. Images were obtained in a SP5 Leica confocal microscope using 40× objective. Image fluorescence analysis was performed using Image J software.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of the values from the number of experiments as indicated in the corresponding figures. Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni multiple comparisons test were used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Albumin Binds Aß With Higher Affinity Than Clusterin

Clusterin is known to bind and to inhibit Aβ aggregation [16], in fact some polymorphisms that cause the dysfunction of this protein are a major risk factor for late onset AD [19]. We used Aβ1–42 in in silico and in vitro experiments because it is the most aggregation-prone species of Aβ peptide and, therefore the most neurotoxic in humans [55]. The comparison of the binding affinities of the clusterin peptides and the CTerm to both the alpha and beta conformations of the Aβ1–42 (Fig. 1C) shows that the four combinations have relatively acceptable ΔG values. Still, albumin's CTerm peptide systematically obtained significantly better scores (p < .001) for the global distribution of all poses. This observation suggests that the CTerm peptide can bind to the Aβ1–42 peptide with an affinity equal or possibly higher than clusterin.

3.2. In silico Analysis of Aβ1–42-CTerm Interaction

A peptide region of human albumin that had been previously identified with iFRAG [39], was predicted to bind to Aβ1–42. The iFRAG method predicts putative fragments that participate in the interface of an interaction through the search for similar sequences of known interactions. We run iFRAG with the albumin and clusterin sequences interacting with the sequence of the Aβ1–42 peptide. We obtained several fragments of clusterin and human albumin that would putatively interact with Aβ1–42. We selected the high score fragments from iFRAG and aligned the sequences with CLUSTAL [56]. The alignment showed 40% similarity and >25% identity, which increased to >70% on a short stretch of 7 amino-acids [39]. The analysis showed that both proteins share a common sequence located at the albumin's CTerm [39]. The CTerm domain has 35 amino acids (AETFTFHADICTLSEKERQIKKQTALVELVKHKPK) and shows high sequence similarity to clusterin (QNAVNGVKQIKTLIEKTNEERKTLLSNLEEAKKKK) [39].

Here, the binding affinity of the CTerm peptide was computationally evaluated against its regular partner (CTerm-lid) and Aβ1–42 in its α and β conformations (Fig. 2A). The score distributions obtained from the generated decoys (Fig. 2B) suggest a slightly higher affinity for the α conformation of Aβ1–42 than for the β, albeit far from the affinity to its normal molecular partner. Interestingly, the CTerm peptide seems to trigger strong conformational changes when binding to the Aβ1–42 peptide. While binding to the peptide in the α conformation translates into changes between the relative position of the two α-helices, binding to the peptide in the β conformation seems to result in a break of the β configuration that might affect the pairing with other Aβ1–42 peptides. The evaluation of the individual contribution of each residue of the CTerm peptide to the binding with Aβ1–42 (Fig. 2C) shows the involvement of residues located throughout the entire peptide, suggesting the need for the full peptide for the recognition of its binding partners. When we analyzed the top 5 best scored decoys (Fig. 2D), we observed a very similar binding configuration. These configurations compete directly with the natural helix-loop-helix segment (CTerm-lid) to which the CTerm binds. All the data concerning the docking analysis can be found at https://github.com/structuralbioinformatics/amyloid/tree/master/albumina. A video showing the docking of the CTerm with Aβ1–42 is available at https://github.com/structuralbioinformatics/amyloid/raw/master/albumina/images/albumina_top5_overlap.mp4.

To further confirm the different behaviour of the α and β conformations, we docked CTerm and clusterin to the described α-β transition state structure (PDB ID: 1Z0Q) and compare it with the results obtained for the α (PDB ID: 1IYT) and the β (PDB ID: 5OQV) conformation (Fig. S4). This comparison also allows to compensate for the difference in crystallization solvents used between 1IYT and 1Z0Q. As expected from its described condition as transition state, 1Z0Q mostly behaves as an intermediate between the two conformations, the only exception being the RosettaScore evaluation. This fact is not that surprising considering that some of the same metrics that define entry quality in the PDB do affect the scoring provide by Rosetta. The differences in ddG between the binding to albumin or clusterin in 1Z0Q are lower than those we obtained for 1IYT or the β conformation. However, it is still within the range to support that albumin can bind to the Aβ peptide with at least the same or better affinity than clusterin.

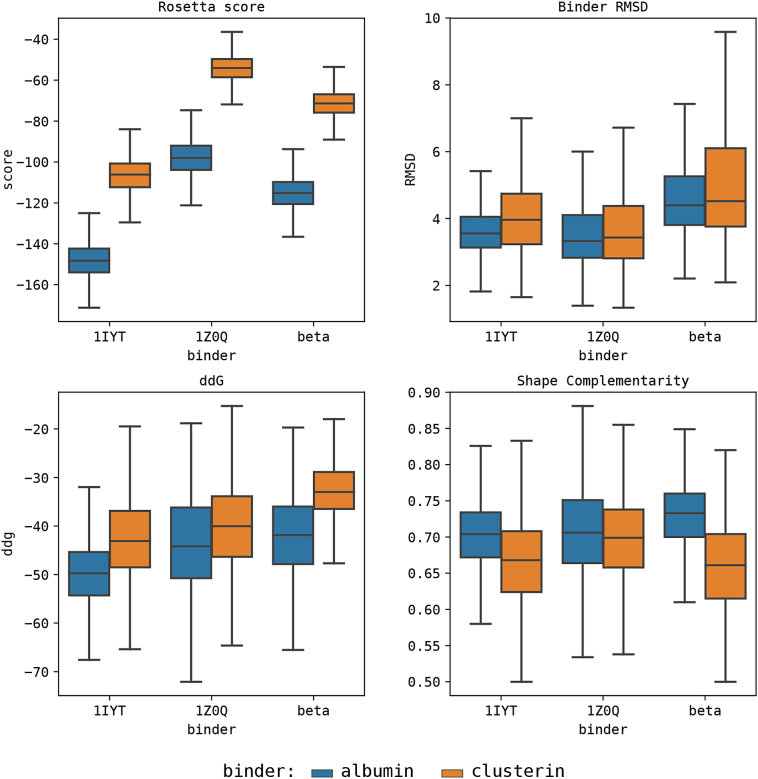

Fig. S4.

Scores distribution of the docking analysis of albumin CTerm and clusterin against α-Aβ1–42 (1IYT), α-β transition Aβ1–42 (1Z0Q) and β-Aβ1–42 (beta). Results show that the transition state (1Z0Q) behaves as an intermediate state between the α and β conformations, especially when evaluating the ddG behavior against the different binding targets. 1Z0Q presents a global stability score (Rosetta score) higher than the other conformations. This is coherent with the quality measure for the structure as provided by the Protein Data Bank. When comparing the behavior of 1Z0Q against the binding targets, no significant differences can be seen in terms of binding. This suggests that this particular conformation bins with a similar affinity to both targets.

3.3. In vitro Analysis of Aβ1–42-CTerm Interaction

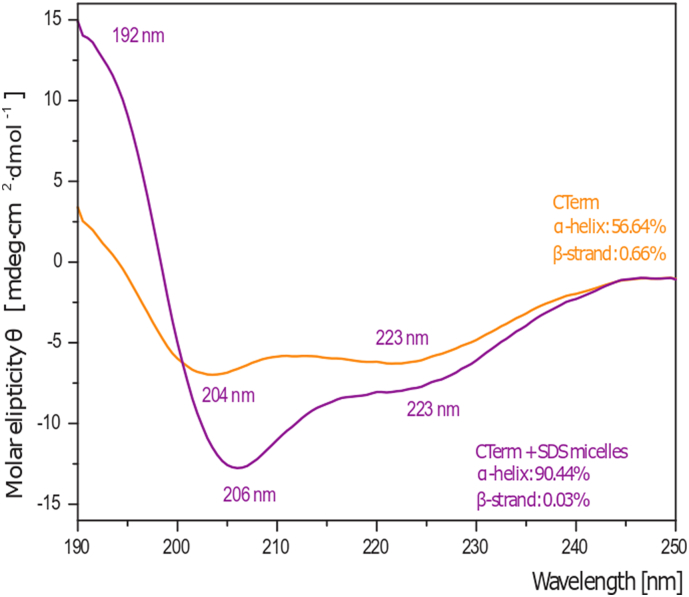

We synthesized the CTerm as explained in the Methodology Section. The CD mean residue molar ellipticity of the CTerm is shown in Fig. S5. In solution, the peptide shows α-helical distinct features (minima at 204 and 223 nm), with α-helix secondary structure content of 56%. SDS micelles (20 mM detergent) used as helical inducer, increases the propensity of the CTerm secondary structure to 90%, with minima at 206 and 223 nm and a maximum at 192 nm.

Fig. S5.

CD spectra of 50 μM CTerm in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2 in the absence (orange) of presence (violet) of 20 mM SDS. α-helix characteristic maxima and minima wavelengths are indicated.

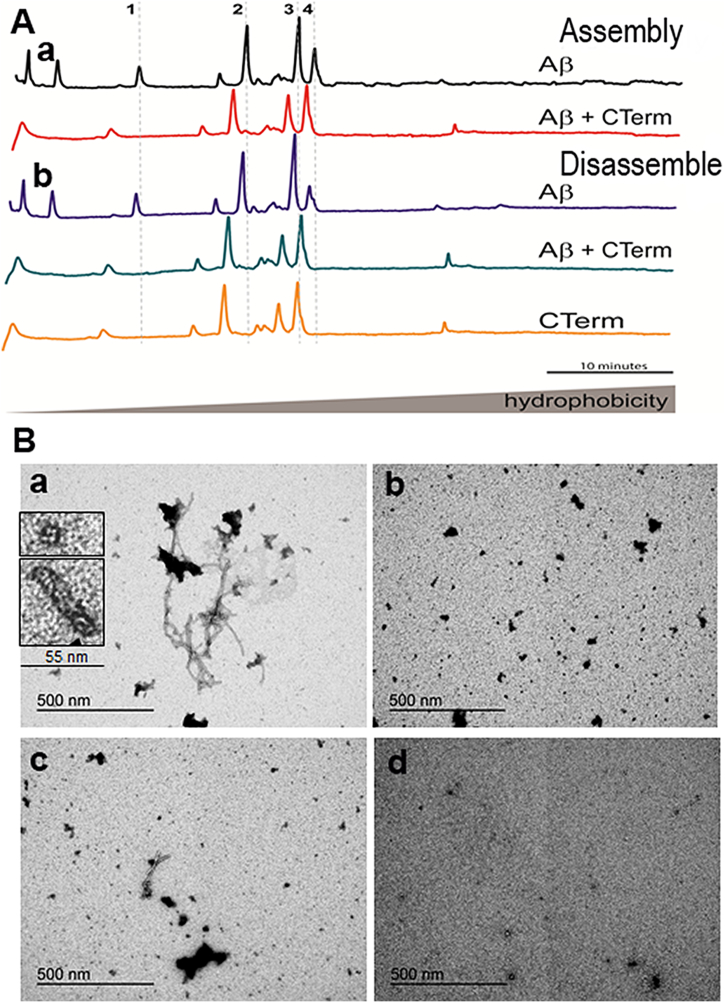

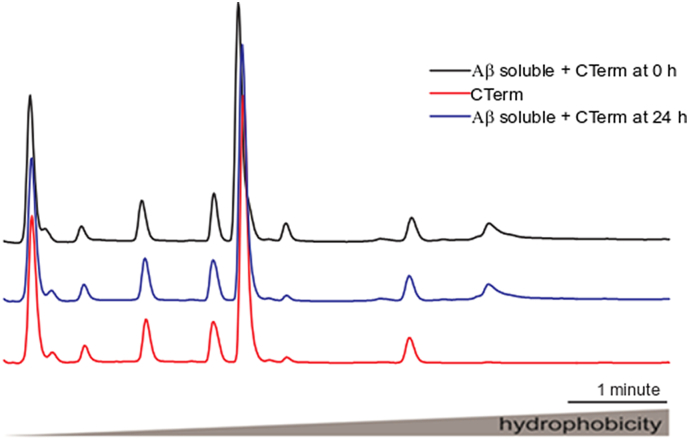

Next, we showed the anti-aggregant properties of the CTerm on Aβ1–42. CTerm was used at 5 μM, which is the physiological concentration found in human CSF. The hydrophobicity analysis of the species present in several mixtures by reversed-phase chromatography (Fig. 3A) reveals several species. At early elution times (left of the chromatograph), the specific peaks due to the presence of Aβ1–42 oligomers are absent when the CTerm is present. In addition, we observed that the CTerm shifts the elution profile to the left, towards more hydrophilic species in the presence of Aβ1–42 oligomers when compared with the elution profile of Aβ1–42 alone (Fig. 3A,a). This behavior indicates that the CTerm prevents the assembly of oligomeric species. Moreover, the CTerm was also able to disassemble preformed Aβ1–42 aggregates of high (fibrils) and low (oligomers) molecular weights (Fig. 3A,b).

Fig. 3.

Effect of the CTerm on Aβ1–42 assembly and disassemble in vitro. Soluble or aggregated 1 μM Aβ1–42 and 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm were incubated for 24 h to allow soluble Aβ assembly or fibrillar Aβ disassemble. A) Fractions eluted by reverse-phase chromatography. In the central part of the graph are the peaks of the high molecular weight fibrils and on the left the peaks that correspond to low molecular weight oligomers. Representative peaks in terms of hydrophobicity: 1, peak corresponding to Aβ1–42 oligomers; 2, 3, and 4, peaks that shift their hydrophobicity in the presence/absence of Aβ1−42 fibrils. A,a) Aggregation assay performed with soluble Aβ1–42. A,b) Disassemble assay performed with aggregated Aβ1–42. Data are from a representative experiment. B) TEM images of aggregation assays. B,a) 1 μM Aβ1–42 aggregated for 24 h. Insets correspond to oligomers and protofibrils. B,b) 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm aggregated for 24 h. B,c) Aggregated 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm incubated for 24 h. B,d) CTerm alone incubated for 24 h. Representative images are shown.

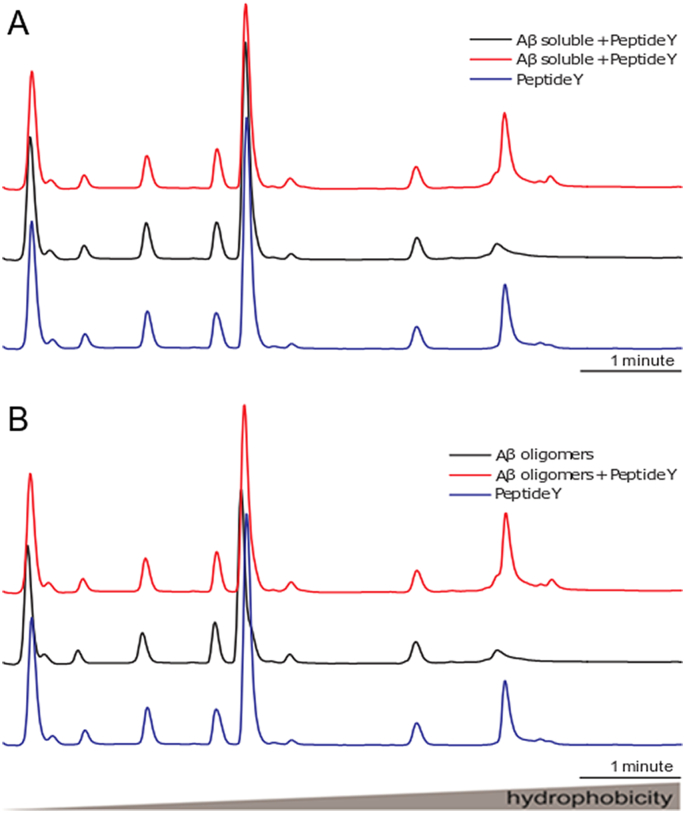

Three peptides of the same size as the CTerm (termed X, Y, Z) were randomly generated to use as controls. We found that the three peptides favour Aβ aggregation and stabilize the pre-existing oligomers and fibrils. The results obtained with Peptide Y, as a representative experiment, are shown in Fig. S6. This pattern of interaction between Aβ and different peptides is expected since it has been reported that the binding of Aβ to proteins can act as seeds for amyloid aggregation and stabilization of fibrils [[57], [58], [59], [60]].

Fig. S6.

The effects of CTerm on Aβ1–42 assembly and disassemble in vitro. Soluble or aggregated 1 μM Aβ1–42 and 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM Peptide Y were incubated for 24 h to allow soluble Aβ assembly or fibrillar Aβ disassemble. Fractions were eluted by reversed-phase chromatography. In the central part of the graph are the peaks of the high molecular weight fibrils, and on the left the peaks of the low molecular weight oligomers.

Furthermore, the anti-aggregant properties of the CTerm were studied by TEM (Fig. 3B). When Aβ1–42 was incubated alone for 24 h, we observed the presence of the typical amyloid unbranched fibrils (Fig. 3B,a), oligomers and protofibrils (inset in Fig. 3B,a). Upon co-incubation of Aβ1–42 with the CTerm, amorphous aggregates were the only structures present (Fig. 3B,b). To study the disassemble ability of the CTerm, when Aβ1–42 was prepared as in Fig. 3B, and was incubated for 24 h with the CTerm, small fibrils and amorphous aggregates were observed (Fig. 3B,c). The interference of CTerm in the analysis was discarded because no aggregates were observed when the CTerm was incubated alone (Fig. 3B,d). These results are in agreement with those obtained in the experiment presented in Fig. 3A and Fig. S7.

Fig. S7.

The in vitro effects of CTerm on Aβ1–42 assembly at times 0 and 24 h. Soluble or aggregated 1 μM Aβ1–42 and 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm were incubated for 0 and 24 h to allow soluble Aβ assembly. Fractions were eluted by reversed-phase chromatography. The peaks corresponding to the high molecular weight fibrils are located in the central part of the graph. The peaks corresponding to the low molecular weight oligomers are located on the left.

3.4. CTerm Protects Neurons against Amyloid Neurotoxicity

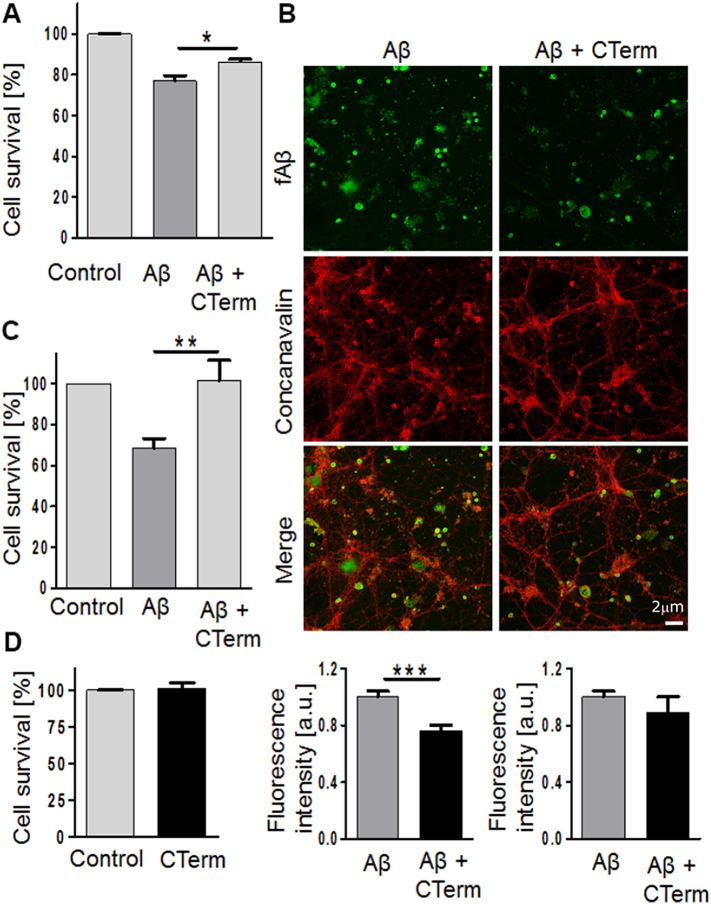

We also studied the effect of the CTerm on Aβ-induced neurotoxicity on a human neuroblastoma cell line. These studies have been performed with soluble Aβ1–42 incubated in the presence/absence of the CTerm for 24 h in vitro. Later, the oligomers were added to cells for 24 h (Fig. 4A). A significant protection was observed when Aβ1–42 aggregates were preformed in the presence of the CTerm (p < .05). Since Aβ aggregates, particularly oligomers, bind to the neuronal membrane impairing its normal function, we studied the binding of Aβ1–42 aggregates formed in the absence/presence of the CTerm to primary cultures of cortical neurons. We used these cell cultures to study the binding of the Aβ1–42 aggregates to the surface of neurites mirroring what happens in vivo. Experiments were run with concanavalin A, a membrane marker, and a fluorescent fAβ1–42 peptide to study their colocalization (Fig. 4B). Cortical neurons treated with fAβ1–42 aggregates (at 10 μM to allow its visualization) showed higher binding to the membrane throughout the neurite network than oligomers formed in the presence of the CTerm. Fluorescence was quantified and the aggregates of fAβ1–42 formed in the presence of the CTerm showed a 25% reduction in binding to neuronal membranes (p < .001; Fig. 4B) while the staining for concanavalin was not modified.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the CTerm on Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in vitro. A) Human neuroblastoma cells were treated with 1 μM Aβ1–42 or 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm, which were previously incubated for 24 h to allow the assembly of Aβ. Cell viability was assayed by MTT reduction after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments performed by duplicate. * p < .05 and ** p < .01. B) Mouse cortical neurons were incubated with aggregated 10 μM fAβ1–42 and 10 μM fAβ1–42 + 20 μM CTerm for 10 min. Binding of Aβ aggregates to the membrane was evaluated by colocalization with membrane markers (concanavalin A staining). Representative images of fAβ1–42 (green) and concanavalin A (red). The quantification analysis of fluorescence intensity of fAβ1–42 was normalized by concanavalin A (bottom, left). Concanavalin A fluorescence was also independently analyzed (bottom, right). Data are the mean ± SEM of 8 replicates. *** p < .001. C) Human neuroblastoma cells were treated with 1 μM Aβ1–42 and 1 μM Aβ1–42 + 5 μM CTerm, aggregates that were previously incubated for 24 h to allow Aβ disassemble by the CTerm. Cell viability was assayed by MTT reduction after 24 h. Data are the mean ± SEM from 8 independent experiments performed by duplicate. * p < .05 and ** p < .01. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Finally, we prepared Aβ1–42 aggregates for 24 h in vitro. Then, they were incubated with the CTerm in vitro for 24 h in order to disassemble the oligomers. Later, human neuroblastoma cells were challenged with these samples for 24 h (Fig. 4C). Aβ1–42 aggregate-induced neurotoxicity was significantly impaired when the Aβ1–42 aggregates were pre-incubated with the CTerm (p < .01; Fig. 4C). The CTerm alone had no effect on cell viability (Fig. 4D).

4. Discussion

In order to elucidate the albumin domain where the anti aggregant Aβ property is located, we determined the regions of human albumin that could interact with Aβ using the iFRAG procedure [39]. In our previous work we had compared the sequence of clusterin, a well-known Aβ binding protein [16] whose polymorphisms are risk factors for late onset AD [19] with that of albumin. We found that the albumin CTerm has >40% similarity (70% identity on a short 7-residue stretch) with clusterin, and therefore we focused our study on the properties of this fragment. In the present work we show in silico evidence that the CTerm peptide produces conformational changes on Aβ1–42 upon binding. This interaction might impair Aβ1–42 conformation into β sheets preventing oligomer and fibril formation. These predictions were confirmed in vitro by reversed-phase chromatography and electron microscopy. Moreover, the in silico results that suggest a change of the β-sheet Aβ1–42 structure fit with the ability of the CTerm to induce disassemble of aggregated Aβ1–42, data that we obtained by reverse phase chromatography and electron microscopy.

As expected, the CTerm at physiological CSF concentration was able to protect neurons against Aβ1–42 neurotoxicity. These results are in agreement with our findings of decreased binding of Aβ aggregates to neuronal membranes when the CTerm is co-incubated with Aβ. Since AD is proposed to begin with the insidious interference of Aβ oligomers on synaptic activity [3,4], we consider that this significant reduction in neurotoxicity and binding of Aβ aggregates to neuronal membranes is reinforcing the protective role of albumin CTerm in AD.

The experimental results in this work highlight the ability of the program iFrag to predict new binding sites for medical relevant targets, for example providing the new binder CTerm for Aβ peptides. Despite previously described interactions between albumin and Aβ peptides, CTerm is a non-exposed region of the albumin and, as such, this site had been dismissed on the prediction of the interaction by other programs. This work confirms that iFrag had successfully identified a fully new binder for Aβ peptides capable of avoiding its aggregation.

Finally, the interest in clusterin and proteins that share common sequences and Aβ binding properties is based on the effect of subtle changes in their sequence, as it has been reported for clusterin [19], or their concentrations, as it has been reported for albumin [61], which along the life of an individual can produce a lack of protection yielding to AD onset after 65 years old.

5. Conclusions

We propose that the CTerm is a key region of albumin that participates in the inhibition of Aβ assembly also favour disassemble of already aggregated Aβ, due to its specific Aβ binding capacity. These findings could set the basis for the design of inhibitory peptides as therapeutic tools for the treatment of AD.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Peak table from CTerm HPLC analysis

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jordi Pujols Pujol for his skillful technical assistance with the RP-HPLC experiments. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Business through grant Plan Estatal SAF2017-83372-R & SAF2014-52228-R (FEDER funds/UE) to FJM and RV; BIO2017-85329-R to BO; AGL2014-52395-C2 and AGL2017- 84097-C2-2-R to D.A.; MDM-2014-0370 through the “María de Maeztu” Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D to “Departament de Ciències Experimentals i de la Salut”; the Chilean Government through Fondecyt 11611065 and AFB170005 to AA, and REDES 180084 to AA and FJM; ISGlobal and IBEC are members of the CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Declaration of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Pol Picón-Pagès, Email: pol.picon_pages@outlook.es.

Jaume Bonet, Email: jaume.bonet@gmail.com.

Javier García-García, Email: javigx2@gmail.com.

Joan Garcia-Buendia, Email: joan.garcia04@estudiant.upf.edu.

Daniela Gutierrez, Email: dngutierrez@uc.cl.

Javier Valle, Email: javier.valle@upf.edu.

Carmen E.S. Gómez-Casuso, Email: csgomezcasuso@gmail.com.

Valeriya Sidelkivska, Email: valeriesidelkivska@gmail.com.

Alejandra Alvarez, Email: aalvarez@bio.puc.cl.

Alex Perálvarez-Marín, Email: Alex.Peralvarez@uab.cat.

Albert Suades, Email: albert.suades@dbb.su.se.

Xavier Fernàndez-Busquets, Email: xfernandez_busquets@ub.edu.

David Andreu, Email: david.andreu@upf.edu.

Rubén Vicente, Email: ruben.vicente@upf.edu.

Baldomero Oliva, Email: baldo.oliva@upf.edu.

Francisco J. Muñoz, Email: paco.munoz@upf.edu.

References

- 1.Masters C.L., Simms G., Weinman N.A., Multhaup G., McDonald B.L., Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flament S., Delacourte A., Mann D.M. Phosphorylation of Tau proteins: a major event during the process of neurofibrillary degeneration. A comparative study between Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome. Brain Res. 1990;516:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90891-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klyubin I., Betts V., Welzel A.T., Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Wallin A. Amyloid protein dimer-containing human CSF disrupts synaptic plasticity: prevention by systemic passive immunization. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4231–4237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5161-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guivernau B., Bonet J., Valls-Comamala V., Bosch-Morató M., Godoy J.A., Inestrosa N.C. Amyloid-β peptide nitrotyrosination stabilizes oligomers and enhances NMDAR-mediated toxicity. J Neurosci. 2016;36:11693–11703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1081-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy J., Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toro D., Coma M., Uribesalgo I., Guix F., Munoz F. The amyloid β-protein precursor and Alzheimers disease. Therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Chem Nerv Syst Agents. 2005;5:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Strooper B., Saftig P., Craessaerts K., Vanderstichele H., Guhde G., Annaert W. Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1998;391:387–390. doi: 10.1038/34910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vassar R., Bennett B.D., Babu-Khan S., Kahn S., Mendiaz E.A., Denis P. Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science. 1999;286:735–741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu Z., Strickland D.K., Hyman B.T., Rebeck G.W. α2-macroglobulin enhances the clearance of endogenous soluble β-amyloid peptide via low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein in cortical neuron. J Neurochem. 2002;73:1393–1398. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deane R., Wu Z., Zlokovic B.V. RAGE (Yin) versus LRP (Yang) balance regulates Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide clearance through transport across the blood-brain barrier. Stroke. 2004;35:2628–2631. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143452.85382.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince M., Bryce R., Albanese E., Wimo A., Ribeiro W., Ferri C.P. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtzman D.M., Morris J.C., Goate A.M. Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:77sr1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon B., Koppel R., Hanan E., Katzav T. Monoclonal antibodies inhibit in vitro fibrillar aggregation of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:452–455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanoiu A., Pariente J., Booth K., Lobello K., Luscan G., Hua L. Long-term safety and tolerability of bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease in two phase 3 extension studies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8 doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valls-Comamala V., Guivernau B., Bonet J., Puig M., Perálvarez-Marín A., Palomer E. The antigen-binding fragment of human gamma immunoglobulin prevents amyloid β-peptide folding into β-sheet to form oligomers. Oncotarget. 2017 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsubara E., Soto C., Governale S., Frangione B., Ghiso J. Apolipoprotein J and Alzheimer's amyloid beta solubility. Biochem J. 1996:671–679. doi: 10.1042/bj3160671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohrmann B., Tjernberg L., Kuner P., Poli S., Levet-Trafit B., Näslund J. Endogenous proteins controlling amyloid beta-peptide polymerization. Possible implications for beta-amyloid formation in the central nervous system and in peripheral tissues. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15990–15995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.15990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biere A.L., Ostaszewski B., Stimson E.R., Hyman B.T., Maggio J.E., Selkoe D.J. Amyloid beta-peptide is transported on lipoproteins and albumin in human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32916–32922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duguid J.R., Bohmont C.W., Liu N.G., Tourtellotte W.W. Changes in brain gene expression shared by scrapie and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos-Fernández E., Tajes M., Palomer E., Ill-Raga G., Bosch-Morató M., Guivernau B. Posttranslational nitro-glycative modifications of albumin in Alzheimer's disease: implications in cytotoxicity and amyloid-β peptide aggregation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:643–657. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milojevic J., Melacini G. Stoichiometry and affinity of the human serum albumin-Alzheimer's Aβ peptide interactions. Biophys J. 2011;100:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milojevic J., Esposito V., Das R., Melacini G. Understanding the molecular basis for the inhibition of the Alzheimer's Abeta-peptide oligomerization by human serum albumin using saturation transfer difference and off-resonance relaxation NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4282–4290. doi: 10.1021/ja067367+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Algamal M., Ahmed R., Jafari N., Ahsan B., Ortega J., Melacini G. Atomic-resolution map of the interactions between an amyloid inhibitor protein and amyloid β (Aβ) peptides in the monomer and protofibril states. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:17158–17168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.792853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christenson R.H., Behlmer P., Howard J.F., Winfield J.B., Silverman L.M. Interpretation of cerebrospinal fluid protein assays in various neurologic diseases. Clin Chem. 1983;29:1028–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn S.-M., Byun K., Cho K., Kim J.Y., Yoo J.S., Kim D. Human microglial cells synthesize albumin in brain. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He X.M., Carter D.C. Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature. 1992;358:209–215. doi: 10.1038/358209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugio S., Kashima A., Mochizuki S., Noda M., Kobayashi K. Crystal structure of human serum albumin at 2.5 a resolution. Protein Eng. 1999;12:439–446. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.6.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter D.C., Ho J.X. Structure of serum albumin. Adv Protein Chem. 1994;45:153–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kragh-Hansen U. Structure and ligand binding properties of human serum albumin. Dan Med Bull. 1990;37:57–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghuman J., Zunszain P.A., Petitpas I., Bhattacharya A.A., Otagiri M., Curry S. Structural basis of the drug-binding specificity of human serum albumin. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fanali G., Di Masi A., Trezza V., Marino M., Fasano M., Ascenzi P. Human serum albumin: from bench to bedside. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:209–290. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simard J.R., Zunszain P.A., Ha C.-E., Yang J.S., Bhagavan N.V., Petitpas I. Locating high-affinity fatty acid-binding sites on albumin by x-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17958–17963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506440102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitlam J.B., Crooks M.J., Brown K.F., Veng Pedrrsen P. Binding of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents to proteins—I. Ibuprofen-serum albumin interaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:675–678. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bar-Or D., Rael L.T., Lau E.P., Rao N.K.R., Thomas G.W., Winkler J.V. An analog of the human albumin N-terminus (Asp-Ala-His-Lys) prevents formation of copper-induced reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:856–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanyon H.F., Viles J.H. Human serum albumin can regulate amyloid-peptide fiber growth in the brain interstitium: implications for Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28163–28168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.360800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Algamal M., Milojevic J., Jafari N., Zhang W., Melacini G. Mapping the interactions between the Alzheimer's Aβ-peptide and human serum albumin beyond domain resolution. Biophys J. 2013;105:1700–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo Y.-M., Emmerling M.R., Lampert H.C., Hempelman S.R., Kokjohn T.A., Woods A.S. High levels of circulating Aβ42 are sequestered by plasma proteins in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:787–791. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuo Y.-M., Kokjohn T.A., Kalback W., Luehrs D., Galasko D.R., Chevallier N. Amyloid-β peptides interact with plasma proteins and erythrocytes: implications for their quantitation in plasma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:750–756. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Garcia J., Valls-Comamala V., Guney E., Andreu D., Muñoz F.J., Fernandez-Fuentes N. iFrag: a protein–protein interface prediction server based on sequence fragments. J Mol Biol. 2017;429:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janin J., Bahadur R.P., Chakrabarti P. Protein–protein interaction and quaternary structure. Q Rev Biophys. 2008;41:133–180. doi: 10.1017/S0033583508004708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wass M.N., Fuentes G., Pons C., Pazos F., Valencia A. Towards the prediction of protein interaction partners using physical docking. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:469. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marín-López M.A., Planas-Iglesias J., Aguirre-Plans J., Bonet J., Garcia-Garcia J., Fernandez-Fuentes N. On the mechanisms of protein interactions: predicting their affinity from unbound tertiary structures. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:592–598. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Šali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martí-Renom M.A., Stuart A.C., Fiser A., Sánchez R., Melo F., Šali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M.A., Madhusudhan M.S., Eramian D., Shen M. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2007;50:2.9.1–2.9.31. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0209s50. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alford R.F., Leaver-Fay A., Jeliazkov J.R., O'Meara M.J., DiMaio F.P., Park H. The Rosetta all-atom energy function for macromolecular modeling and design. J Chem Theory Comput. 2017;13:3031–3048. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman H.M., Kleywegt G.J., Nakamura H., Markley J.L. The protein data Bank archive as an open data resource. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2014;28:1009–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10822-014-9770-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams R., Griffin L., Compson J.E., Jairaj M., Baker T., Ceska T. Extending the half-life of a fab fragment through generation of a humanized anti-human serum albumin Fv domain: an investigation into the correlation between affinity and serum half-life. MAbs. 2016;8:1336–1346. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1185581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crescenzi O., Tomaselli S., Guerrini R., Salvadori S., D'Ursi A.M., Temussi P.A. Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide (1-42) in an apolar microenvironment. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5642–5648. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gremer L., Schölzel D., Schenk C., Reinartz E., Labahn J., Ravelli R.B.G. Fibril structure of amyloid-β(1–42) by cryo–electron microscopy. Science. 2017;358:116–119. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2825. (80- ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kilambi K.P., Reddy K., Gray J.J. Protein-protein docking with dynamic residue protonation states. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nivón L.G., Moretti R., Baker D. A pareto-optimal refinement method for protein design scaffolds. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louis-Jeune C., Andrade-Navarro M.A., Perez-Iratxeta C. Prediction of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism using theoretically derived spectra. Proteins. 2012;80:374–381. doi: 10.1002/prot.23188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bitan G., Teplow D.B. Preparation of aggregate-free, low molecular weight amyloid-beta for assembly and toxicity assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;299:3–9. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-874-9:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang Y.-J., Chen Y.-R. The coexistence of an equal amount of Alzheimer's amyloid-β 40 and 42 forms structurally stable and toxic oligomers through a distinct pathway. FEBS J. 2014;281:2674–2687. doi: 10.1111/febs.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sievers F., Higgins D.G. Clustal omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1079:105–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muñoz F.J., Inestrosa N.C. Neurotoxicity of acetylcholinesterase amyloid beta-peptide aggregates is dependent on the type of Abeta peptide and the AChE concentration present in the complexes. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:205–209. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castillo G.M., Lukito W., Wight T.N., Snow A.D. The sulfate moieties of glycosaminoglycans are critical for the enhancement of beta-amyloid protein fibril formation. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1681–1687. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motamedi-Shad N., Monsellier E., Chiti F. Amyloid formation by the model protein muscle acylphosphatase is accelerated by heparin and heparan sulphate through a scaffolding-based mechanism. J Biochem. 2009;146:805–814. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shin T.M., Isas J.M., Hsieh C.-L., Kayed R., Glabe C.G., Langen R. Formation of soluble amyloid oligomers and amyloid fibrils by the multifunctional protein vitronectin. Mol Neurodegener. 2008;3(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Llewellyn D.J., Langa K.M., Friedland R.P., Lang I.A. Serum albumin concentration and cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:91–96. doi: 10.2174/156720510790274392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Peak table from CTerm HPLC analysis