Abstract

Background

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE) is characterized by recurrent swelling in subcutaneous or submucosal tissues. Symptoms often begin by age 5–11 years and worsen during puberty, but attacks can occur at any age and recur throughout life. Disease course in elderly patients is rarely reported.

Methods

The Icatibant Outcome Survey (IOS) is an observational study evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of icatibant. We conducted descriptive analyses in younger (age < 65 years) versus elderly patients (age ≥ 65 years). Here, we report patient characteristics and safety-related findings.

Results

As of February 2018, 872 patients with C1-INH-HAE type I/II were enrolled, of whom 100 (11.5%) were ≥ 65 years old. Significant differences between elderly versus younger patients, respectively, were noted for median age at symptom onset (17.0 vs 12.0 years), age at diagnosis (41.0 vs 19.4 years), and delay between symptom onset and diagnosis (23.9 vs 4.8 years) (P ≤ 0.0001 for all). Median age at diagnosis was significantly higher in elderly patients regardless of family history (P < 0.0001). Throughout the study, icatibant was used to treat 6798 attacks in 574 patients, with 63 elderly patients reporting 715 (10.5%) of the icatibant-treated attacks. No serious adverse events (SAEs) in elderly patients were judged to be possibly related to icatibant, whereas two younger patients reported three possibly related SAEs. Excluding off-label use and pregnancy (evaluated for regulatory purposes), the percentage of patients with at least one possibly/probably related AE was similar for elderly (2.0%) versus younger patients (2.7%). No deaths linked to icatibant treatment were identified. All related events in elderly patients were attributed to general disorders/administration site conditions, whereas related events in younger patients occurred across various system organ class designations.

Conclusions

Elderly patients with C1-INH-HAE were significantly older at diagnosis and had greater delay in diagnosis than younger patients. Elderly patients contributed to approximately 10% of the icatibant-treated attacks. Our analysis found similar AE rates (overall and possibly/probably related) in icatibant-treated elderly versus younger patients, despite the fact that elderly patients had significantly more comorbidities and were receiving a greater number of concomitant medications. Our analysis did not identify any new or unexpected safety concerns.

Keywords: Hereditary angioedema, Icatibant Outcome Survey, Safety, Elderly

Background

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE) is a rare, chronic disease caused by SERPING1 gene mutations [1]. Clinical manifestations include recurrent, unpredictable episodes of bradykinin-mediated swelling in subcutaneous or submucosal tissues that are associated with a heavy burden of illness [2, 3]. Attacks can range from mild to severe and debilitating [4], negatively affecting patients’ ability to attend school, be productive at work, or participate in daily social activities [5].

Onset of symptoms typically begins within the first two decades of life (often by age 10–11 years), with intensity of attacks worsening during puberty [6]. However, C1-INH-HAE attacks may occur at any age and recur throughout a patient’s lifetime [7, 8]. As such, treatment of acute attacks is a lifelong necessity and can pose unique challenges for elderly patients. Presence of age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes, coupled with the high likelihood of comorbid conditions for which multiple medications are required, underscores the importance of monitoring the safe use of medication in this population [9]. To date, publications focused on managing C1-INH-HAE attacks in elderly patients are scarce. One observational registry study of 27 patients receiving an intravenously administered, plasma-derived C1-INH concentrate for the management of acute attacks demonstrated safe use in patients aged ≥ 65 years [10].

Icatibant, a subcutaneously administered antagonist of the bradykinin B2 receptor, has demonstrated efficacy and safety for the treatment of acute attacks in adults with HAE type I/II in three Phase 3 randomized, double-blind studies [11, 12]. However, mean patient age was < 65 years in all three trials [11, 12]. Although systemic exposure of icatibant has been shown to be increased in elderly patients, no effects on safety have been identified in this population [13].

The Icatibant Outcome Survey (IOS) is an ongoing international, prospective, observational drug registry study (NCT01034969) designed to monitor real-world safety and effectiveness of icatibant. Patients who are currently receiving, or are candidates for, treatment with icatibant are eligible to participate. Here, we compare patient characteristics and safety-related findings in elderly versus younger patients with C1-INH-HAE type I/II enrolled in the IOS.

Methods

Study design

Data for this analysis were collected from July 2009 through February 28, 2018, across 59 sites in 13 countries. The IOS study is conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Approvals were received from local ethics committees and/or health authorities, and patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Study design is presented in detail elsewhere [14]. Briefly, patient data were recorded via electronic forms by physicians at baseline and during follow-up visits (occurring approximately every 6 months), including frequency and severity of icatibant-treated attacks since the previous visit, safety/tolerability issues with icatibant treatment, presence of comorbid conditions and use of concomitant medications.

Adverse event-related outcome measures

Adverse events (AEs) were assessed by frequency of occurrence, relationship to icatibant (possibly/probably/not related), and seriousness and severity (mild/moderate/severe). AEs classified as “possibly related to treatment” were those that occurred within a reasonable time sequence following administration of icatibant and are biologically plausible. Alternatively, the AE could be explained by concurrent disease or other drugs/chemicals. AEs classified as “probably related to treatment” were those that occurred within a reasonable time sequence following administration of icatibant, are biologically plausible, and are unlikely to occur as a result of concurrent disease or other drugs/chemicals.

AEs were categorized in accordance with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class and preferred term, and analyzed by the proportions of occurrence (percentage of patients reporting an event). For reporting seriousness/relationship of AEs to icatibant, each patient was counted only once, and only the highest seriousness/relationship category was reported for that patient.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted in younger patients (defined as ages < 65 years) versus elderly patients (≥ 65 years). Age at the time of data extract was used to define the age subgroups. For patients who discontinued early or died, age at discontinuation or death was used. Differences between age groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test for baseline characteristics; the Fisher test for possibly/probably related AEs and individual comparisons of mild, moderate, and severe AEs; and the Chi square test for individual comparisons of serious and non-serious AEs. Due to the observational nature of the registry, all analyses were considered exploratory; P-values were interpreted descriptively.

Results

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

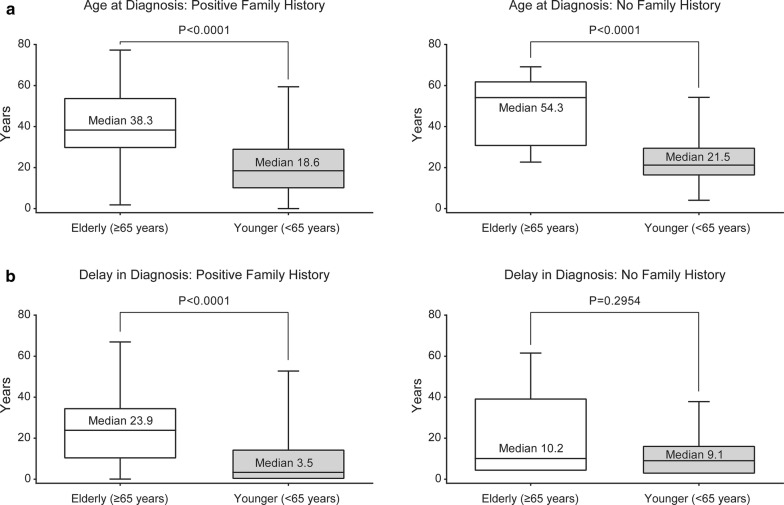

As of February 28, 2018, 872 patients with C1-INH-HAE type I/II were enrolled in the IOS (Table 1). Significant differences between elderly versus younger patients, respectively, were noted for age at symptom onset (median 17.0 vs 12.0 years, P = 0.0001), age at diagnosis (median 41.0 vs 19.4 years, P < 0.0001), and delay between symptom onset and diagnosis (median 23.9 vs 4.8 years, P < 0.0001 [Table 1]). When evaluated in relation to family history, median age at diagnosis was significantly higher in elderly than in younger patients, regardless of presence or absence of a family history (P < 0.0001, Fig. 1a). Whereas delay in diagnosis was significantly higher in elderly versus younger patients with a family history (23.9 vs 3.5 years, respectively, P < 0.0001); the difference between age groups was not significant in the absence of a family history (10.2 vs 9.1 years, P = 0.2954; Fig. 1b).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | Overall | P-value (elderly vs younger) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 100 (11.5) | 772 (88.5) | 872 (100) | |

| Type I | 89 (89.0) | 717 (92.9) | 806 (92.4) | |

| Type II | 11 (11.0) | 55 (7.1) | 66 (7.6) | 0.1680 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 51 (51.0) | 471 (61.0) | 522 (59.9) | 0.0547 |

| Age at enrollment (years) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 67.9 (63.8, 70.9) | 36.8 (27.0, 47.3) | 39.5 (27.9, 51.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Age at symptom onset (years) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 17.0 (7.0, 25.0) | 12.0 (5.0, 18.0) | 12.0 (5.0, 19.0) | 0.0001 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 41.0 (30.8, 59.0) | 19.4 (11.4, 30.2) | 21.1 (13.1, 33.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Delay in diagnosis, (years) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 23.9 (5.9, 37.2) | 4.8 (0.21, 15.7) | 6.1 (0.3, 17.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Family history of C1-INH-HAE, n, % | ||||

| Yes | 71 (71.0) | 565 (73.2) | 636 (72.9) | |

| No | 11 (11.0) | 100 (13.0) | 111 (12.7) | |

| Unknown | 7 (7.0) | 50 (6.5) | 57 (6.5) | |

| Missing | 11 (11.0) | 57 (7.4) | 68 (7.8) | 0.6051 |

| Attack severity, n (%) | ||||

| Number of attacksa | 581 | 5378 | 5959 | |

| Very mild | 11 (1.9) | 18 (0.3) | 29 (0.5) | |

| Mild | 51 (8.8) | 546 (10.2) | 597 (10.0) | |

| Moderate | 227 (39.1) | 2202 (40.9) | 2429 (40.8) | |

| Severe | 219 (37.7) | 1941 (36.1) | 2160 (36.2) | |

| Very severe | 73 (12.6) | 671 (12.5) | 744 (12.5) | |

| Very mild, mild, moderate vs severe/very severe | 0.4393 | |||

| Attack location, n (%) | ||||

| Number of attacksa | 726 | 6016 | 6742 | |

| Skin | 323 (44.5) | 2702 (44.9) | 3025 (44.9) | 0.958 |

| Abdomen | 369 (50.8) | 3510 (58.3) | 3879 (57.5) | 0.438 |

| Larynx | 38 (5.2) | 293 (4.9) | 331 (4.9) | |

| Other | 70 (9.6) | 216 (3.6) | 286 (4.2) | |

| Use of long-term prophylaxis, n (%) | 2 (3.2) | 8 (2.0) | – | 0.6329 |

| Number of cardiovascular medications, per patient | ||||

| Number of patients | 49 | 66 | 115 | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 0.0019 |

C1-INH-HAE hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency, Q quartile

aAttacks with severity/location data included; attacks with “missing” or “unknown” severity/location excluded

Fig. 1.

a Age at diagnosis in elderly and younger patients, with and without a family history and b delay in diagnosis in elderly and younger patients, with and without a family historya. The horizontal line inside each box indicates the median, the lower and upper borders of each box indicate the first and third quartiles, and the lowest and highest horizontal lines outside the box indicate the minimum and maximum value. aA total of 113 patients with a family history had a negative delay in diagnosis (wherein diagnosis occurred before onset of symptoms, based on confirmatory laboratory testing); younger, n = 108; elderly, n = 5. Likewise, a total of five patients with no family history had a negative delay in diagnosis, all in the younger group

Of attacks with available severity data, there was no difference between groups (P = 0.4393) when comparing very mild/mild/moderate attacks versus severe/very severe attacks (Table 1). Attacks at a single site versus multiple sites comprised the majority of attacks in both the elderly and younger groups (elderly, 653/726 attacks [89.9%]; younger, 5339/6016 attacks [88.7%]) and there was no significant difference in attack location (Table 1).

Comorbid conditions and their treatment

Elderly patients were significantly more likely than younger patients to have multiple comorbidities, both at baseline (IOS entry; 52.0% vs 11.1%, P < 0.0001) and during the follow-up period (26.0% vs 11.5%, P = 0.0002). For example, elderly patients were significantly more likely to have hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, bleeding disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, diabetes, pulmonary disease, or renal-urogenital disorders at baseline, and hypertension, bleeding disorders, diabetes, and hepatic disorders during the follow-up period (Tables 2, 3). Similarly, elderly patients received a greater number of concomitant medications for cardiovascular/cerebrovascular conditions, both at baseline (median 2.0 vs 1.0 medications per patient, P = 0.0019; Table 1) and during the follow-up period (median 2.0 vs 1.0 medications per patient, P = 0.1238).

Table 2.

Select comorbid conditions at baseline and follow-up

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | Baseline | Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | P | Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | P | |

| Bleeding | 4 (4.0) | 5 (0.6) | 0.0130 | 4 (4.0) | 5 (0.6) | 0.0130 |

| Cardiovascular/cerebrovascular | 50 (50) | 69 (8.9) | < 0.0001 | 26 (26.0) | 49 (6.3) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 11 (11.0) | 17 (2.2) | 0.0001 | 6 (6.0) | 8 (1.0) | 0.0027 |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (11.0) | 19 (2.5) | 0.0002 | 7 (7.0) | 24 (3.1) | 0.0757 |

| Hepatic | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1147 | 2 (2.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0362 |

| Immunological | 2 (2.0) | 25 (3.2) | 0.7592 | 2 (2.0) | 36 (4.7) | 0.3008 |

| Infections | 1 (1.0) | 8 (1.0) | 1.0000 | 4 (4.0) | 25 (3.2) | 0.5650 |

| Neoplasia | 3 (3.0) | 6 (0.08) | 0.0735 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 1.0000 |

| Neurological | 1 (1.0) | 9 (1.2) | 1.0000 | 3 (3.0) | 9 (1.2) | 0.1498 |

| Osteoarticular | 1 (1.0) | 7 (0.9) | 1.0000 | 2 (2.0) | 17 (2.2) | 1.0000 |

| Psychiatric | 7 (7.0) | 23 (3.0) | 0.0706 | 6 (6.0) | 25 (3.2) | 0.1549 |

| Pulmonary | 7 (7.0) | 11 (1.4) | 0.0023 | 2 (2.0) | 10 (1.3) | 0.6380 |

| Renal/urogenital | 4 (4.0) | 5 (0.6) | 0.0130 | 3 (3.0) | 6 (0.8) | 0.0735 |

Table 3.

Cardiovascular comorbidities at baseline and follow-up

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | Baseline | Follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | P | Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | P | |

| Hypertension | 48 (51.6) | 64 (9.0) | < 0.0001 | 13 (18.1) | 27 (5.3) | 0.0004 |

| Angina | 2 (2.2) | 4 (0.6) | 0.1435 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1.0000 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5 (5.4) | 5 (0.7) | 0.0028 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 1.0000 |

| Heart failure | 2 (2.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0363 | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1248 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 6 (6.5) | 5 (0.7) | 0.0006 | 1 (1.4) | 3 (0.6) | 0.4147 |

AEs related to icatibant treatment

During the time covered by this analysis, icatibant was used to treat 6798 attacks in 574 patients, with 715 icatibant-treated attacks reported by 63 (63.0%) elderly patients. Elderly and younger patients were similarly likely to have at least one treated attack (63.0% vs 66.2%, P = 0.527).

A similar percentage of elderly and younger patients experienced at least one AE possibly or probably related to icatibant (2.0% vs 2.7%; Table 4). No serious AEs (SAEs) occurring in elderly patients were judged to be possibly related to icatibant, whereas two younger patients reported three possibly related SAEs; one patient reporting gastritis (n = 1) and reflux esophagitis (n = 1), the other patient reporting angioedema crisis (n = 1).

Table 4.

Overall summary of AEs

| Elderly (≥ 65 years) | Younger (< 65 years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 100) | Events | Patients (n = 772) | Events | |

| Total AEs, n (%) | 28 (28.0) | 86 (100.0) | 164 (21.2) | 374 (100.0) |

| Occurrence of ≥ 1 icatibant-related AE, n (%) | 2 (2.0) | 19 (22.1) | 21 (2.7) | 68 (18.2) |

| AEs by relationship to icatibant use, n (%) | ||||

| Not recorded | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.4) | 28 (7.5) |

| Not related | 26 (26.0) | 67 (77.9) | 132 (17.1) | 278 (74.3) |

| Possibly related | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) | 34 (9.1) |

| Probably related | 2 (2.0) | 19 (22.1) | 16 (2.1) | 34 (9.1) |

| Icatibant-related AEs by seriousness, n (%) | ||||

| Serious | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (4.4) |

| Not serious | 2 (2.0) | 19 (100.0) | 19 (2.5) | 65 (95.6) |

AE adverse event

The occurrence of mild and moderate AEs was similar between elderly and younger patients (P = 0.2170 and P = 0.2666, respectively). During the study, there were no deaths linked to treatment with icatibant.

A total of eight younger patients experiencing AEs had an older family member with C1-INH-HAE, however only two of these younger patients had an older family member (their father) who also experienced AEs. No patterns were found in the type of AEs experienced by related patients.

Icatibant-related AEs by system organ class

Excluding off-label use and pregnancy-related AEs (evaluated for regulatory purposes), all related events in elderly patients were attributed to general disorders/administration site conditions, whereas treatment-related events in younger patients occurred across various system organ classes, including general disorders/administration site conditions, vascular disorders, skin/subcutaneous tissue disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, nervous system disorders, and others (Table 5).

Table 5.

AEs possibly/probably related to icatibant, by system organ class and preferred terma

| Patients | Elderly (≥ 65 years) (n = 100) | Younger (< 65 years) (n = 772) | Overall (n = 872) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE n (%) | 2 (2.0) | 21 (2.7) | 23 (2.6) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2 (2.0) | 15 (1.9) | 17 (1.9) |

| Injection site erythema | 1 (1.0) | 9 (1.2) | 10 (1.1) |

| Pain | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) |

| Application site erythema | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Application site pain | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Infusion site pain | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) |

| Drug ineffective | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Infusion site erythema | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Injection site pain | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Injection site hemorrhage | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Localized edema | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Edema | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Therapeutic product ineffective | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Infusion site urticaria | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Administration site reaction | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Asthenia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Vascular disorders | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) |

| Hyperemia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Hot flush | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) |

| Skin reaction | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Angioedema | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) |

| Nausea | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Reflux esophagitis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Hiatus hernia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Gastritis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Post-herpetic neuralgia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Investigations | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Blood pressure decreased | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Infections and infestations | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Herpes zoster | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Depression | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

aExcludes AEs related to off-label use and pregnancy; AE adverse event

Discussion and conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis that compares patient characteristics and safety and tolerability of icatibant in elderly versus younger patients with C1-INH-HAE. Findings from our analysis revealed a significantly older age at diagnosis in elderly versus younger patients with C1-INH-HAE, regardless of family history. Interestingly, delay in diagnosis was significantly longer in elderly versus younger patients in the presence of a positive family history, whereas the delay was similar for both age groups in the absence of a family history. This may have occurred due to the substantially larger number of younger patients with a positive family history (prompting earlier diagnosis), as well as better diagnostic work-up in families in current clinical practice. The delay in elderly patients with a family history may also be caused by the fact that their relatives from previous generations may have given up seeking medical advice for their condition and were living with symptoms, having lacked a formal diagnosis or effective C1-INH-HAE treatments in their own youth.

Our analysis did not reveal any new or unexpected safety concerns. Despite the fact that elderly patients had significantly more comorbidities and were receiving a greater number of concomitant medications, the occurrence of icatibant-related AEs was similar in the treated elderly versus younger population, with no significant differences noted between groups with regard to seriousness or severity of AEs. These findings correlate with those previously reported in an observational drug registry study by Bygum et al., who found no unexpected safety concerns in older versus younger patients treated with an intravenously administered, plasma-derived C1-INH in a real-world setting [10]. Additionally, no trends were noted with regard to the type of AEs experienced by younger patients who were related to an older patient enrolled in the IOS.

Our study had several limitations, including an uncontrolled clinical environment inherent in an observational study design; description of AEs relied heavily on patient recall. Additionally, substantially fewer elderly than younger patients were enrolled.

Despite the limitations, our real-world analysis provides valuable insight with regard to clinical characteristics of elderly patients with C1-INH-HAE and the safety of treating acute attacks with icatibant in this patient population.

Acknowledgements

Under the direction of the authors, Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD, CMPP, and David Lickorish, PhD, CMPP, of Excel Medical Affairs, provided writing assistance for this publication. Editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, copyediting, and fact-checking also was provided by Excel Medical Affairs. Funding for writing and editorial assistance was provided by Shire Human Genetic Therapies, a Takeda company, Lexington, MA, USA.

IOS investigators

Austria: W. Aberer; Brazil: A.S. Grumach; Czech Republic: R. Hakl, Denmark: A. Bygum; France: C. Blanchard Delaunay, I. Boccon-Gibod, L. Bouillet, B. Coppere, A. Du Thanh, C. Dzviga, O. Fain, B. Goichot, A. Gompel, S. Guez, P.Y. Jeandel, G. Kanny, D. Launay, H. Maillard, L. Martin, A. Masseau, Y. Ollivier, A. Sobel; Germany: E. Aygören-Pürsün, M. Baş, M. Bauer, K. Bork, J. Greve, M. Magerl, I. Martinez-Saguer, M. Maurer, U. Strassen; Greece: E. Papadopoulou-Alataki, F. Psarros; Israel: Y. Graif, S. Kivity, A. Reshef, E. Toubi; Italy: F. Arcoleo, M. Bova, M. Cicardi, P. Manconi, G. Marone, V. Montinaro, M. Triggiani, A. Zanichelli; Spain: M.L. Baeza, T. Caballero, R. Cabañas, M. Guilarte, D. Hernandez, C. Hernando de Larramendi, R. Lleonart, T. Lobera, L. Marqués, B. Saenz de San Pedro; Sweden: J. Björkander; United Kingdom: C. Bethune, T. Garcez, H.J. Longhurst.

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- C1-INH-HAE

hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency

- IOS

Icatibant Outcome Survey

- SAE

serious adverse event

Authors’ contributions

AB, TC, HJL, LB, WA, AZ, and MM contributed to study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and critical content revisions; IA contributed to study conception and design, analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and critical content revisions; JB contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and critical content revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Although employees of the sponsor were involved in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation, and fact-checking of information, the content of this manuscript, the interpretation of the data, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication in Clinical and Translational Allergy was made by the authors independently.

Funding

IOS is funded and supported by Shire International GmbH, a Takeda company, Zug, Switzerland.

Availability of data and materials

Shire provides access to the de-identified individual participant data (IPD) for eligible studies to aid qualified researchers in addressing legitimate scientific objectives. These IPDs will be provided following approval of a data sharing request, and under the terms of a data sharing agreement.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IOS is conducted in multiple sites across 13 countries in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All sites obtained approval from local ethics committees and/or health authorities (where applicable), and all patients provided written informed consent before the initiation of data collection. Consent from parents or a legal representative was obtained for patients who were younger than 18 years of age at the time of enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AB has received research grant support and/or speaker/consulting fees from CSL Behring and Shire*, and participated in a clinical trial for BioCryst and Jerini AG. She is an advisor for the HAE Scandinavian Patient Organization. TC has received speaker fees from CSL Behring, Novartis, and Shire,* consulting fees from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Novartis, and Shire,* funding for travel/meeting attendance from CSL Behring, Novartis, and Shire,* and has participated in clinical trials/registries for BioCryst, CSL Behring, Novartis, Pharming, and Shire.* She is a researcher from the IdiPAZ program for promoting research activities. ASG has been a speaker/consultant for BioCryst, CSL Behring, and Shire.* HJL has received research grant support and/or speaker/consulting fees from Adverum, BioCryst, CSL Behring, Shire,* and Sobi. LB has received honoraria from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Novartis, Pharming, and Shire* and her institute has received research funding from CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche, and Shire.* WA has acted as a medical advisor and speaker for BioCryst, CSL Behring, Pharming, and Shire* and has received funding to attend conferences/educational events, and donations to his departmental fund from and participated in clinical trials for Shire.* AZ has received speaker fees from CSL Behring, Shire,* and Sobi; consulting fees from CSL Behring and Shire* and has acted on the medical/advisory boards for CSL Behring and Shire.* JB and IA are full-time employees of Shire,* Zug, Switzerland. MM has received research grant support and/or speaker/consulting fees from BioCryst, CSL Behring, and Shire*.

*A Takeda company.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anette Bygum, Phone: 6541 1803, Email: Anette.Bygum@rsyd.dk.

Teresa Caballero, Email: mteresa.caballero@idipaz.es.

Anete S. Grumach, Email: asgrumach@gmail.com

Hilary J. Longhurst, Email: hlonghurst@doctors.org.uk

Laurence Bouillet, Email: LBouillet@chu-grenoble.fr.

Werner Aberer, Email: werner.aberer@medunigraz.at.

Andrea Zanichelli, Email: andrea.zanichelli@unimi.it.

Jaco Botha, Email: jaco.botha@shire.com.

Irmgard Andresen, Email: iandresen@shire.com.

Marcus Maurer, Email: Marcus.Maurer@charite.de.

for the IOS Study Group:

W. Aberer, A. S. Grumach, R. Hakl, A. Bygum, C. Blanchard Delaunay, I. Boccon-Gibod, L. Bouillet, B. Coppere, A. Du Thanh, C. Dzviga, O. Fain, B. Goichot, A. Gompel, S. Guez, P. Y. Jeandel, G. Kanny, D. Launay, H. Maillard, L. Martin, A. Masseau, Y. Ollivier, A. Sobel, E. Aygören-Pürsün, M. Baş, M. Bauer, K. Bork, J. Greve, M. Magerl, I. Martinez-Saguer, M. Maurer, U. Strassen, E. Papadopoulou-Alataki, F. Psarros, Y. Graif, S. Kivity, A. Reshef, E. Toubi, F. Arcoleo, M. Bova, M. Cicardi, P. Manconi, G. Marone, V. Montinaro, M. Triggiani, A. Zanichelli, M. L. Baeza, T. Caballero, R. Cabañas, M. Guilarte, D. Hernandez, C. Hernando de Larramendi, R. Lleonart, T. Lobera, L. Marqués, B. Saenz de San Pedro, J. Björkander, C. Bethune, T. Garcez, and H. J. Longhurst

References

- 1.Buyantseva LV, Sardana N, Craig TJ. Update on treatment of hereditary angioedema. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2012;30(2):89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longhurst H, Bygum A. The humanistic, societal, and pharmaco-economic burden of angioedema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(2):230–239. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston DT. Diagnosis and management of hereditary angioedema. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghazi A, Grant JA. Hereditary angioedema: epidemiology, management, and role of icatibant. Biologics. 2013;7:103–113. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S27566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerji A. The burden of illness in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(5):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen SC, Davis DK, Castaldo AJ, Zuraw BL. Pediatric hereditary angioedema: onset, diagnostic delay, and disease severity. Clin Pediatr. 2016;55(10):935–942. doi: 10.1177/0009922815616886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis-Lorton M. An update on the diagnosis and management of hereditary angioedema with abnormal C1 inhibitor. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(2):151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119(3):267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinks TH, Egberts TC, de Lange TM, de Koning FH. Pharmacist-based medication review reduces potential drug-related problems in the elderly: the SMOG controlled trial. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(2):123–133. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200926020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bygum A, Martinez-Saguer I, Bas M, Rosch J, Edelman J, Rojavin M, Williams-Herman D. Use of a C1 inhibitor concentrate in adults ≥ 65 years of age with hereditary angioedema: findings from the international Berinert® (C1-INH) Registry. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(11):819–827. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0403-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, Malbrán A, Rosenkranz B, Riedl M, Bork K, Lumry W, Aberer W, Bier H, et al. Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):532–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumry WR, Li HH, Levy RJ, Potter PC, Farkas H, Moldovan D, Riedl M, Li H, Craig T, Bloom BJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant for the treatment of acute attacks of hereditary angioedema: the FAST-3 trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;107(6):529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firazyr [prescribing information]. Lexington, MA; Shire; 2011.

- 14.Maurer M, Aberer W, Bouillet L, Caballero T, Fabien V, Kanny G, Kaplan A, Longhurst H, Zanichelli A. Hereditary angioedema attacks resolve faster and are shorter after early icatibant treatment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e53773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Shire provides access to the de-identified individual participant data (IPD) for eligible studies to aid qualified researchers in addressing legitimate scientific objectives. These IPDs will be provided following approval of a data sharing request, and under the terms of a data sharing agreement.