Abstract

Lichen planus (LP) is an idiopathic, cell-mediated immune disorder, accompanied by itching. Spontaneous remission occurs. Topical and systemic therapies are utilised. Four cases of generalized LP with and without mucosal involvement treated homeopathically are presented. Case 1: A 48-year-old female presented with a 7-month history of generalized itchy rash, which had been diagnosed as LP, treated unsuccessfully with topical steroids and removal of dental fillings. Examination revealed violaceous papules on upper and lower limbs, oral mucosal lesions and an irregular, erythematous, blanching, macular rash on the chest. She received homeopathic Ignatia amara at medication dilution factor (MK) potency, weekly dose and went into remission at 3 months. Patient remains in remission. Case 2: A 65-year-old female presented with a 27-year history of generalized, LP, which had been unresponsive to topical steroids. Examination showed generalized, violaceous papules, with no mucosal involvement. She received homeopathic Aurum metallicum, MK potency, weekly, and went into remission. She relapsed at 8 months after onset of therapy, following a very stressful incident, but gained remission again with Aurum metallicum after 1 month of therapy. She remains in remission. Case 3: A 38-year-old male presented with a 21-year history of generalized LP. Medical history was significant for hepatitis B and asthma. Topical steroid therapy was only partially successful. Examination revealed generalized, violaceous papules, with oral and genital involvement. He received homeopathic Lycopodium at MK potency, weekly, and remitted by 2 months. He remains in remission. Case 4: A 41-year-old male presented with a 12-year history of generalized hypertrophic LP, which had responded partially to topical steroids and ultraviolet A therapy. Medical history was significant for reduced sense of smell. Examination revealed generalized, violaceous, hypertrophic papules and nodules. He received homeopathic Carcinosinum at MK potency and remitted at 6-months. In its long-standing, generalized form, with mucosal involvement, LP may respond to individualized homeopathy. More research may clarify homeopathy's place in LP therapy.

Keywords: mucosal lichen planus, generalized lichen planus, complementary and alternative medicine, homeopathic medicine, homeopathy

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is an idiopathic, cell-mediated immune disorder, accompanied by itching, mucosal lesions and characteristic skin lesions in most cases. The clinical manifestations of LP have been described as the ‘6 Ps’ of LP, namely: Pruritic, purple, polygonal, planar, papules and plaques, encompassing the main manifestations of this disorder (1). Different subtypes of LP are more prevalent in certain populations and sub groups, for example, actinic, hypertrophic, pigmentosus and childhood variants are more common in African American and darker-skinned populations. Of note, childhood LP has a greater male prevalence, which is unusual for an autoimmune disorder (1).

There is a potential for the development of malignancy in association with mucosal lesions. Spontaneous remission occurs. Topical and systemic therapies are utilized including potent topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA), narrow band UVB, oral corticosteroids and acitretin (2).

Since these therapies are not without complications and may be ineffective in some cases, other treatment modalities with potential are welcome. Complementary and alternative or integrative therapies have been tried as a therapeutic possibility and as a way of avoiding the side effects of conventional therapies. A study of Ayurvedic medicine, combining herbs and diet for LP therapy, reported 100% remission rates, although residual post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and dryness were seen (3).

Homeopathy is a therapeutic system developed by the German physician, Samuel Hahnemann. It is based on the utilization of infinitesimal concentrations (extremely high dilutions) of substances to treat diseases and thus, is free of the side effects associated with conventional therapy. Its exact mechanism of action remains to be elucidated, but homeopathy enjoys increasing popularity with growth rates of 25% per year in India (4) and in the US, homeopathy was one of the most commonly used forms of CAM, used by 2.1% of the population (5).

Four cases of recalcitrant, generalized LP with and without mucosal involvement treated homeopathically are presented.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Cabinet Medical Individual (Bucharest, Romania), and a written informed consent was provided by all the patients included in this study.

Case studies

Case 1

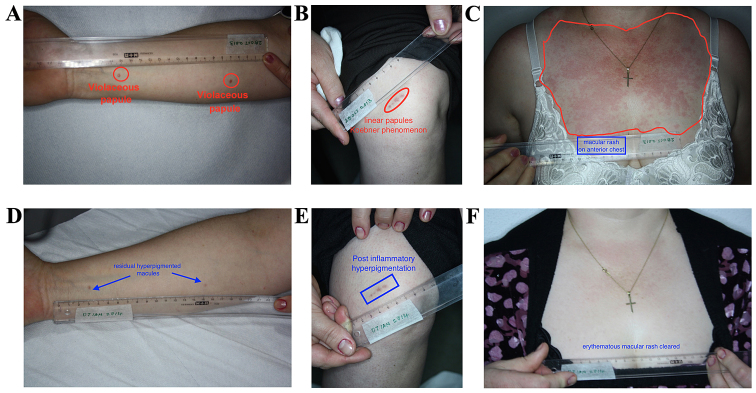

A 48-year-old female presented with a 7-month history of generalized LP. Topical corticosteroid treatment and removal of dental fillings did not ameliorate the condition. Examination revealed violaceous papules on upper and lower limbs, oral mucosal lesions and an irregular, erythematous, blanching, macular rash on the chest. She received the homeopathic medicine Ignatia amara at MK potency, weekly dosage and went into remission at 3 months. The patient relapsed (after presentation of the abstract of this work), following work-related stress and dental work, at 2.5 years after the last visit. She presented with only oral lesions, which responded to Ignatia amara MK (Fig. 1A-F).

Figure 1.

(A) Violaceas papules on right forearm. (B) Linear distribution of violaceous papules of left knee in Koebner phenomenon. (C) Erythematous, irregularly-defined macules on chest. (D) Remission with lesions cleared from forearm. (E) Residual hyperpigmentation of remitted lichen planus. (F) Remission of erythematous macules on chest.

Case 2

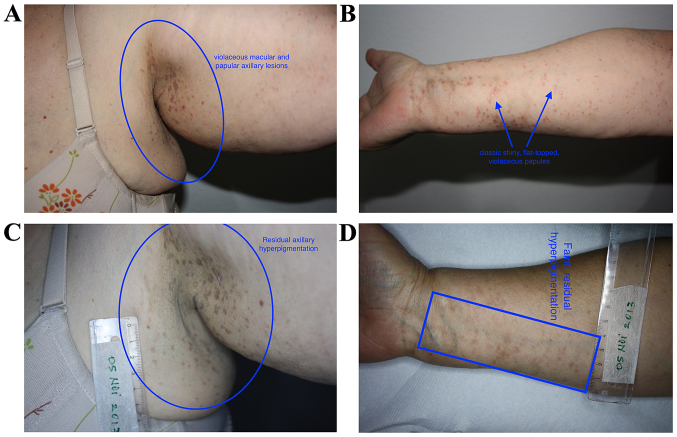

A 65-year-old female presented with a 27-year history of generalized, LP, which was unresponsive to topical steroids. Examination showed generalized, violaceous papules, with no mucosal involvement. She received homeopathic Aurum metallicum, MK potency, weekly dosage, and went into remission. She relapsed at 8 months after onset of therapy, following a stressful incident, but remitted again with repetition of Aurum metallicum after 1 month of therapy. She remained in remission for 3 years until the death of her mother, which triggered a relapse for which she received Aurum metallicum again. This helped put her into remission once more (Fig. 2A-D).

Figure 2.

(A) Multiple, violaceous papules on left axilla. (B) Multiple shiny, flat-topped, violaceous papules on left forearm. (C) Healed lesions with hyperpigmented macules in left axilla. (D) Healed lesions with hyperpigmented macules on left forearm.

Case 3

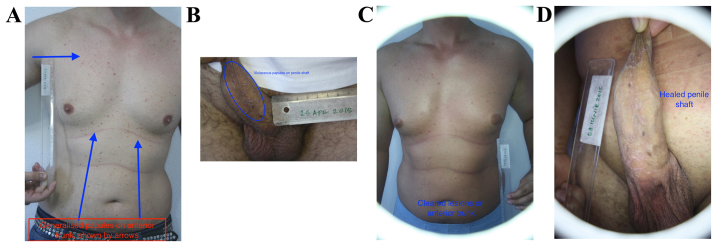

A 38-year-old male presented with a 21-year history of generalized LP. Medical history was significant for hepatitis B and asthma. Topical clobetasol had been tried with only limited success. Examination revealed generalized, violaceous papules, with oral and genital involvement. He received homeopathic Lycopodium clavatum at MK potency, weekly dosage, and remitted by 2 months. He remains in remission (Fig. 3A-D).

Figure 3.

(A) Multiple, violaceous papules on anterior trunk. (B) Coalescent, violaceous papules on penile shaft. (C) Cleared lesions on the anterior trunk. (D) Healed penile lesions with residual scarring.

Case 4

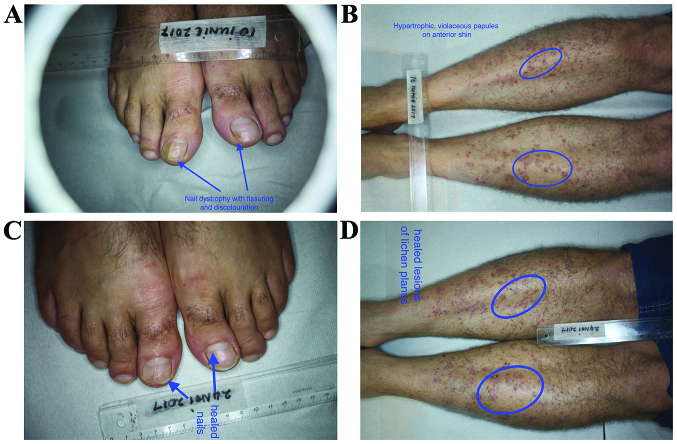

A 41-year-old male presented with a 12-year history of itchy rash, which had responded partially to topical steroids and UVA therapy. Medical history was significant for reduced sense of smell. Examination revealed generalized, violaceous, hypertrophic papules, with dystrophic nails. He also had palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis. No mucosal lesions were observed. He received homeopathic Carcinosinum at MK potency and remitted at 6 months, with improved sense of smell (Fig. 4A-D).

Figure 4.

(A) Lichen planus nail dystrophy with discoloration and fissuring of toenails (midline ridge not part of lichen planus pathology). (B) Multiple, hypertrophic, violaceous papules on shins. (C) Remission of nail lesions (residual fissuring at tip of nail due to rate of nail growth in ridged area). (D) Residual lesions of healed lichen planus with some scarring.

Discussion

LP is an idiopathic, autoimmune disorder primarily involving the cell-mediated immune system. It constituted 0.38 and 5% of dermatology patients (6,7) in India and Nigeria respectively, as well as 32–38/100,000 patients (8) in a UK review of GP practices.

Differential diagnosis of LP includes prurigo, eczema, psoriasis, drug eruption, oral leukoplakia, candida infection, Queyrat erythroplasia and genital lichen sclerosus (2,9,10). Distinguishing these conditions from LP is essential, as some of these conditions are not as benign as LP itself (11). In spite of this, the diagnosis of LP is often straightforward as the violaceous lesions of LP tend to be characteristic and histopathology is reserved for difficult cases (9–11).

Histopathology of LP is characteristic, comprising a hyperkeratotic epidermis with irregular acanthosis and focal thickening of the granular layer. Colloid or civatte bodies, which are degenerative keratinocytes can be found in the lower epidermis. Other colloid bodies comprising IgM (occasionally IgG and IgA) with complement can also be seen. There are fibrin and fibrinogen deposits in the basement membrane zone. A band-like lymphocytic infiltrate (mostly helper T cells), Langhans cells and histiocytes can be seen.

Newer techniques, such as confocal microscopy, which is useful in other papulosquamous disorders, may also be of value in diagnosing LP (12).

Therapy of LP is aimed at controlling and suppressing the disorder, as curative treatment is not documented in the literature. This includes topical and oral steroids, topical and oral calcineurin inhibitors, PUVA, metronidazole, itraconazole, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone and thalidomide (2,13). These options are fraught with side effects, some of which are potentially severe (13).

Complementary therapies have been tried for LP, including traditional Chinese medicine and herbs, such as Aloe vera (14). Some small studies have shown Aloe vera to be more effective than triamcinolide for oral LP (14).

Homeopathy is a complementary and alternative therapeutic method begun by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. It utilizes infinitesimal quantities of medication to treat disease, thus, side effects such as allergies or potential teratogenicity are obviated.

A randomized controlled trial using the homeopathic medicine Ignatia amara, which is obtained by making a very high dilution of the plant, was carried out. The study group had 30 patients, with histopathologically confirmed erosive and/or atrophic LP. The follow-up period was 4 months. The patients were randomized to either placebo or Ignatia 30c. Mean lesion size and pain scores were significantly in favour of homeopathic treatment (15).

Homeopathic therapies are individualized, as homeopaths believe that personal traits produce individualized predispositions to disease. As a result, a homeopathic consultation is often like a psychological consultation, with the aim being to ascertain personality traits in the patient that can be matched by the profile of the homeopathic medicine. It is this match, rather than the physical pathology the patient presents with, that determines what homeopathic medicine may be used in each case. The homeopathic medicines used in these cases were of vegetable origin (Lycopodium and Ignatia), chemical origin (Aurum metallicum) and human origin (Carcinosinum). The posology is determined by the intensity of the manifestation of the disease and whether it is acute or chronic.

Psychosomatic dermatology supports this mode of thinking and these psychosomatic skin disorders have been classified in such a way as to ease discomfort of dermatologists, via increased knowledge (16). This mode of thinking appears to mirror and support the theory of locus minoris resistentiae that has been posited in order to explain the occurrence of cutaneous disorders in various locations (17,18). Some of these disease locations have included unilateral occurrence of rosacea, nasal spinulosis, pityriasis folliculorum, unilateral blepharitis and endosymbiont proliferation (19–25). Various side effects such as skin atrophy, telangiectasia, acne, pustules, scaling, contact allergy, weight gain, sleep disturbances and localized proliferation of endosymbionts have been reported with conventional medications such as corticosteroids (26–33), but not with homeopathic therapies. Concerns regarding these side effects, including the carcinogenic potential of drugs used also for their anti-inflammatory properties have been raised and alternatives suggested (34–37).

Of note, nanomedicine has been associated with the mode of action of homeopathy and recent research suggests that homeopathic medicines may work by inducing the production of nanomolecules, which may then influence physiopathologic processes in the human body (38–40).

Although this case series is small (n=4), these cases were generalized, recalcitrant cases of LP, often with mucosal involvement. Dermatologists are aware that these are characteristically difficult to treat in daily clinical, dermatological practice. Thus, therapies that could potentially place the patient in remission would always be welcome. Homeopathy has been found to be useful in lichen striatus, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, acne, dermatitis herpetiformis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, amongst others (41–47). It is also a very cheap form of treatment, that is well tolerated by all categories of patients and can be used in pregnancy, for which there are many potential applications (48,49). Complementary and alternative medical therapies, including plant extracts have been used for the treatment of various diseases since ancient times, even during periods of economic downturn and their characteristics have been analysed in detail (50–60). Informed consent obliges us to fully disclose all positive and potential adverse effects of the therapies we propose to our patients. This ethical approach means that patients sometimes refuse to take the treatments offered to them for fear of adverse reactions as well as in resistance to the use of animals in biomedical research (61–63). This may cause them to turn to other therapeutic systems for help, even without consulting their primary physician thus, in order to properly educate our patients and bridge this gap, research into the usefulness of complementary therapies has been recommended (64,65).

Our results suggest that recalcitrant, long-standing, generalized LP, with mucosal involvement may respond to individualized homeopathy. Randomised controlled trials also support the potential role of homeopathy in the therapy of LP (11). Larger studies are needed to confirm these assertions and these may finally clarify homeopathy's place in LP therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

LCN examined the test subjects and evaluated the in vivo effects. MM performed the acquisition analysis and interpretation of the data. ALT contributed to the writing of the manuscript, as well as all revisions for intellectual content and scientific quality. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, as well as revising it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Cabinet Medical Individual (Bucharest, Romania), and a written informed consent was provided by all the patients included in this study.

Patient consent for publication

A written informed consent for the publication of the images was provided by all the participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis, and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:742826. doi: 10.1155/2014/742826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usatine RP, Tinitigan M. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narahari SR, Prasanna KS, Sushma KV. Evidence-based integrative dermatology. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:127–131. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.108046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad R. Homoeopathy booming in India. Lancet. 2007;370:1679–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dossett ML, Davis RB, Kaptchuk TJ, Yeh GY. Homeopathy use by US adults: Results of a National Survey. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:743–745. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alabi GO, Akinsanya JB. Lichen planus in tropical Africa. Trop Geogr Med. 1981;33:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharya M, Kaur I, Kumar B. Lichen planus: A clinical and epidemiological study. J Dermatol. 2000;27:576–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2000.tb02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pannell RS, Fleming DM, Cross KW. The incidence of molluscum contagiosum, scabies and lichen planus. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:985–991. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805004425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brănișteanu DE, Pintilie A, Dimitriu A, Cerbu A, Ciobanu D, Oanţă A, Tatu AL. Clinical, laboratory and therapeutic profile of lichen planus. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2017;121:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brănişteanu DE, Pintilie A, Andreş LE, Dimitriu A, Oanţă A, Stoleriu G, Brănişteanu DC. Ethiopatogenic hypotheses in lichen planus. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2016;120:760–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brănişteanu DE, Brănişteanu DC, Stoleriu G, Ferariu D, Voicu CM, Stoica LE, Căruntu C, Boda D, Filip-Ciubotaru FM, Dimitriu A, et al. Histopathological and clinical traps in lichen sclerosus: A case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57(Suppl):817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batani A, Brănișteanu DE, Ilie MA, Boda D, Ianosi S, Ianosi G, Caruntu C. Assessment of dermal papillary and microvascular parameters in psoriasis vulgaris using in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:1241–1246. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, Schneider SW. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: A step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981–991. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy RL, Reddy RS, Ramesh T, Singh TR, Swapna LA, Laxmi NV. Randomized trial of aloe vera gel vs triamcinolone acetonide ointment in the treatment of oral lichen planus. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:793–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousavi F, Sherafati S, Mojaver YN. Ignatia in the treatment of oral lichen planus. Homeopathy. 2009;98:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nwabudike LC. Knowledge removes discomfort. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:738–739. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Happle R, Kluger N. Answer to Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC: Koebner's sheep in Wolf's clothing - does the isotopic response exist as a distinct phenomenon? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e336–337. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nwabudike LC, Tatu AL, Gambichler T, et al. Altered epigenetic pathways and cell cycle dysregulation in healthy appearing skin of patients with koebnerized squamous cell carcinomas following skin surgery. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e3–e4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tatu AL, Ionescu MA, Cristea VC. Demodex folliculorum associated Bacillus pumilus in lesional areas in rosacea. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:610–611. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_921_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatu AL, Clatici VG, Nwabudike LC. Rosacea-like demodicosis (but not primary demodicosis) and papulopustular rosacea may be two phenotypes of the same disease - a microbioma, therapeutic and diagnostic tools perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e46–e47. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatu AL. Nasal Spinulosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:339. doi: 10.1177/1203475417694861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatu AL, Cristea VC. Pityriasis folliculorum of the back thoracic area: Pityrosporum, keratin plugs, or demodex involved? J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:441. doi: 10.1177/1203475417711114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tatu AL, Cristea VC. Unilateral blepharitis with fine follicular scaling. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:442. doi: 10.1177/1203475417711124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC, Kubiak K., et al. Endosymbiosis and its significance in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e346–e347. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatu AL, Clatici V, Cristea V. Isolation of Bacillus simplex strain from Demodex folliculorum and observations about Demodicosis spinulosa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:818–820. doi: 10.1111/ced.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatu AL. Topical steroid induced facial rosaceiform dermatitis. Acta Endocrinol (Buch) 2016;12:232–233. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2016.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatu AL, Clătici VG. Some correlations between the clinical and dermoscopic features of steroid induced facial dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(Suppl):AB91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tatu AL, Ionescu MA, Clatici VG, Cristea VC. Bacillus cereus strain isolated from Demodex folliculorum in patients with topical steroid-induced rosaceiform facial dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:676–678. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatu AL, Ionescu MA, Nwabudike LC. Contact allergy to topical mometasone furoate confirmed by rechallenge and patch test. Am J Ther. 2018;25:e497–e498. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. Eforie; Romania: 2017. The treatment options of male genital Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: Treatments of genital Lichen sclerosus. In: Proceedings of the 14th National Congress of Urogynecology and the National Conference of the Romanian Association for the Study of Pain; pp. 262–264. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. Male genital lichen sclerosus - a permanent therapeutic challenge. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(Suppl 1):AB185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. Bullous reactions associated with COX-2 inhibitors. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e477–e480. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gheorghe I, Tatu AL, Lupu I, Thamer O, Cotar AI, Pircalabioru GG, Popa M, Cristea VC, Lazar V, Chifiriuc MC. Molecular characterization of virulence and resistance features in Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains isolated from cutaneous lesions in patients with drug adverse reactions. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2017;22:12321–12327. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. Metoprolol-associated onset of psoriatic arthropathy. Am J Ther. 2017;24:e370–e371. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nwabudike LC, Tatu AL. Response to - chronic exposure to tetracyclines and subsequent diagnosis for non-melanoma skin cancer in a large Mid-Western US population. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e159. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatu AL, Ciobotaru OR, Miulescu M, Buzia OD, Elisei AM, Mardare N, Diaconu C, Robu S, Nwabudike LC. Hydrochlorothiazide: Chemical structure, therapeutic, phototoxic and carcinogenetic effects in dermatology. Revista de Chimie. 2018;69:2110–2114. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nwabudike LC, Elisei AM, Buzia OD, Miulescu M, Tatu AL. Statins. A review on structural perspectives, adverse reactions and relations with non-melanoma skin cancer. Revista de Chimie. 2018;69:2557–2562. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montagnier L, Aïssa J, Ferris S, Montagnier JL, Lavallée C. Electromagnetic signals are produced by aqueous nanostructures derived from bacterial DNA sequences. Interdiscip Sci. 2009;1:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s12539-009-0036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ion R, Boda D. Porphyrin-based supramolecular nanotubes generated by aggregation processes. Revista de Chimie. 2008;59:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chikramane PS, Suresh AK, Bellare JR, Kane SG. Extreme homeopathic dilutions retain starting materials: A nanoparticulate perspective. Homeopathy. 2010;99:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.homp.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Signore RJ. Treatment of lichen striatus with homeopathic calcium carbonate. J Amer Ost College of Derm. 2011;21:43. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nwabudike LC. Palmar and plantar psoriasis and homeopathy Case reports. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:66–69. doi: 10.7241/ourd.20171.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witt CM, Lüdtke R, Willich SN. Homeopathic treatment of patients with psoriasis - a prospective observational study with 2 years follow-up. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:538–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nwabudike LC. Atopic dermatitis and homeopathy. Our Dermatol Online. 2012;3:217–220. doi: 10.7241/ourd.20123.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nwabudike LC. Case reports of acne and homeopathy. Complement Med Res. 2018;25:52–55. doi: 10.1159/000486309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nwabudike LC. Homeopathy in the treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis - a case presentation. Homeopathic Links. 2015;28:44–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nwabudike LC. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Mycosis fungoides) treated by homeopathy: A 3-case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:AB92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tatu AL. The skin and nevi pigmentation during pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(Suppl 1):AB 148. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatu AL. Melasma and pregnancy. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;53(Suppl 2):37. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatu AL. Dermoscopic structural changes of nevi during pregnancy related to location. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(Suppl 1):AB75. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tatu AL. Skin tags and pregnancy. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51(Suppl 1):A48–A50. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buzia OD, Fasie V, Mardare N, Diaconu C, Gurau G, Tatu AL. Formulation, preparation, physico-chimical analysis, microbiological peculiarities and therapeutic challenges of extractive solution of Kombucha. Revista de Chimie. 2018;69:720–724. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zălaru C, Crişan C, Călinescu I, Moldovan Z, Ţârcomnicu I, Litescu S, Tatia R, Moldovan L, Boda D, Iovu M. Polyphenols in Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt. fruits and the plant extracts antioxidant capacity evaluation. Open Chem. 2014;12:858–867. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mihăilă B, Dinică RM, Tatu AL, Buzia OD. New insights in vitiligo treatments using bioactive compounds from Piper nigrum. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:1241–1246. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buzia OD, Mardare N, Florea A, Diaconu C, Dinica RM, Tatu AL. Formulation and preparation of pharmaceuticals with anti-rheumatic effect using the active principles of capsicum annuum and piper nigrum. Revista de Chimie. 2018;69:2854–2857. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tatu AL, Ionescu MA. Multiple autoimmune syndrome type III - thyroiditis, vitiligo and alopecia areata. Acta Endocrinol (Buch) 2017;13:124–125. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2017.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nwabudike LC, Tatu AL. Magistral prescription with silver nitrate and Peru balsam in difficult to heal diabetic foot ulcers. Am J Ther. 2018;25:e679–e680. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ionescu C, Țârcomnicu I, Ionescu MA, Nicolescu TO, Boda D, Nicolescu F. Identification and characterization of the methanolic extract of hellebrigenin 3-acetate from helleborirhizomes. Mass spectrometry. Revista de Chimie. 2014;1:972–975. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boda D, Ion R-M. Synthesis, spectral and photodynamic properties of lithium phthalocyanine. Revista de Chimie. 2014;65:1271–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raţiu MP, Purcărea I, Popa F, Purcărea VL, Purcărea TV, Lupuleasa D, Boda D. Escaping the economic turn down through performing employees, creative leaders and growth driver capabilities in the Romanian pharmaceutical industry. Farmacia. 2011;59:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robu S, Chesaru BI, Diaconu C, Dumitriu BO, Tutunaru D, Stanescu U, Lisa EL. Lavandulahybrida: Microscopic characterization and the evaluation of the essential oil. Farmacia. 2016;64:914–917. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rogozea LM, Diaconescu DE, Dinu EA, Badea O, Popa D, Andreescu O, Leaşu FG. Bioethical dilemmas in using animal in medical research. Challenges and opportunities. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:1227–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Purcaru D, Preda A, Popa D, Moga MA, Rogozea L. Informed consent: How much awareness is there? PLoS One. 2014;9:e110139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jou J, Johnson PJ. Nondisclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to primary care physicians: Findings from the 2012 national health interview survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:545–546. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nwabudike LC. Pustular eruption (iododerma?) in a patient with cancer treated with complementary and alternative medicine. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:495–496. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.