Abstract

Purpose: Amblyopia and strabismus affect 2%–5% of the population and cause a broad range of visual deficits. The response to treatment is generally assessed using visual acuity, which is an insensitive measure of visual function and may, therefore, underestimate binocular vision gains in these patients. On the other hand, the contrast sensitivity function (CSF) generally takes longer to assess than visual acuity, but it is better correlated with improvement in a range of visual tasks and, notably, with improvements in binocular vision. The present study aims to assess monocular and binocular CSFs in amblyopia and strabismus patients.

Methods: Both monocular CSFs and the binocular CSF were assessed for subjects with amblyopia (n = 11), strabismus without amblyopia (n = 20), and normally sighted controls (n = 24) using a tablet-based implementation of the quick CSF, which can assess a full CSF in <3 min. Binocular summation was evaluated against a baseline model of simple probability summation.

Results: The CSF of amblyopic eyes was impaired at mid-to-high spatial frequencies compared to fellow eyes, strabismic eyes without amblyopia, and control eyes. Binocular contrast summation exceeded probability summation in controls, but not in subjects with amblyopia (with or without strabismus) or strabismus without amblyopia who were able to fuse at the test distance. Binocular summation was less than probability summation in strabismic subjects who were unable to fuse.

Conclusions: We conclude that monocular and binocular contrast sensitivity deficits define important characteristics of amblyopia and strabismus that are not captured by visual acuity alone and can be measured efficiently using the quick CSF.

Keywords: amblyopia and strabismus, contrast sensitivity function (CSF), quick CSF, visual acuity, binocular summation

Introduction

Amblyopia and strabismus are the most common developmental disorders of binocular vision, with an estimated prevalence of around 2%–5% (Graham, 1974; Ross et al., 1977; Friedmann et al., 1980; Cohen, 1981; Simpson et al., 1984; Stayte et al., 1990; Thompson et al., 1991; Satterfield et al., 1993; Kvarnström et al., 2001; Jakobsson et al., 2002; Barry and König, 2003; Robaei et al., 2005). Amblyopia affects the spatial vision of one or both eyes in the absence of an obvious organic cause and is associated with a history of abnormal visual experience during development (The Lasker/IRRF Initiative for Innovation in Vision Science, 2018). Strabismus impairs the ability to align the eyes so that targets are imaged on the fovea of the fixing eye and on parafoveal retina in the strabismic eye. The magnitude of strabismus may vary with viewing distance, such that some people with strabismus are able to fuse at some viewing distances (Hatt et al., 2008), and the strabismic deviation may be constant or intermittent (for review, see Helveston, 2010). Strabismus is associated with social difficulties (Satterfield et al., 1993; Olitsky et al., 1999; Jackson et al., 2006), a reduced quality of life (Tandon et al., 2014), elevated risk of sustaining musculoskeletal injury, fracture, or fall (Pineles et al., 2015b), and a negative impact on employment opportunities (Goff et al., 2006; Mojon-Azzi and Mojon, 2007).

Strabismus is a common cause of amblyopia (Woodruff et al., 1994b; Simons, 2005), although amblyopia can also be caused by other developmental disorders such as anisometropia or visual deprivation (Helveston, 2010). Amblyopia is associated with deficits in spatial vision (Robaei et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2017) including reduced visual acuity (Kirschen and Flom, 1978; Levi and Klein, 1982, 1985; Kelly and Buckingham, 1998), contrast sensitivity loss (Hess and Howell, 1977; Levi and Harwerth, 1978; Bradley and Freeman, 1981; Kiorpes et al., 1999; McKee et al., 2003), spatial distortion (Pugh, 1958; Hess et al., 1978; Fronius and Sireteanu, 1989; Hess, 2001), abnormal contour integration (Hess et al., 1997; Hess and Demanins, 1998), and binocular acuity summation (Sireteanu, 1982; Chang et al., 2017) deficits.

The current standard treatment for amblyopia is to provide a period of refractive correction (Cotter et al., 2012), then to use occlusion (eye patching) or penalization (blurring eye drops) therapies that temporarily impair vision in the fellow eye and force the use of the amblyopic eye (for review, see Clarke, 2010). Strabismus may be treated surgically (Mets et al., 2004), with prism correction (Gunton and Brown, 2012), or with vision therapy (Scheiman et al., 2011; for review, see Rutstein et al., 2012). However, these treatments for amblyopia (Woodruff et al., 1994a; Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, 2003; Fresina and Campos, 2014) and strabismus (Fresina and Campos, 2014) rarely restore normal binocular vision. Consequently, after treatment, many patients experience persistent interocular suppression (Holopigian et al., 1988; Hess, 1991; Harrad, 1996; Kwon et al., 2015) or deficits in stereoacuity (Stewart et al., 2013; Levi et al., 2015) and binocular acuity summation (Blake and Fox, 1973; Chang et al., 2017).

Visual acuity is the main clinical measure for functional outcomes. However, many studies have shown that contrast sensitivity remains impaired in the affected eye even after normal acuity has been achieved by amblyopia treatment (Regan et al., 1977; Sjöstrand, 1981; Rogers et al., 1987; Cascairo et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2007). In many cases, visual acuity deficits may be more evident with low- than high-contrast visual acuity tests (Pineles et al., 2013, 2014b, 2015a). Furthermore, the contrast sensitivity loss in amblyopia is spatial-frequency dependent, a property that cannot be assessed by high- or low-contrast visual acuity alone. In several studies the amblyopic eye showed reduced contrast sensitivity that mostly occurred at mid-high spatial frequencies, while deficits at low spatial frequencies were less common (Hess and Howell, 1977; Levi and Harwerth, 1977; Rentschler et al., 1980; Sjöstrand, 1981; Howell et al., 1983), suggesting a significant need for assessing spatial-frequency dependent deficits in characterizing amblyopic vision.

Although the contrast sensitivity function (CSF) of the fellow fixing eye remains normal or near normal in amblyopia (Cascairo et al., 1997), binocular summation is greatly compromised or absent in amblyopia (Levi et al., 1980; Sireteanu et al., 1981; Pardhan and Whitaker, 2000; Hess et al., 2014) unless the sensitivity deficit of the amblyopic eye is compensated (Pardhan and Gilchrist, 1992; Baker and Meese, 2007; Baker et al., 2007a). In principle, the binocular summation deficit could arise from impaired mechanisms of binocular interaction that are not spatially-selective (Huang et al., 2011). Alternatively, it may depend on structural correlations, which may show spatial frequency selective effects of inter-ocular refractive differences, as in anisometropia, Holopigian et al. (1986) or misaligned binocular receptive fields, as in strabismus (Thorn and Boynton, 1974). In subjects with intermittent strabismus, binocular summation may, therefore, depend on whether fusion is possible at the testing distance. These spatial-frequency dependent features of contrast sensitivity deficits make the CSF a good candidate for evaluating monocular and binocular vision in strabismus and amblyopia.

While the need for effective assessment of contrast deficits in the patient population has been recognized (Owsley and Sloane, 1987; Sebag et al., 2016) its clinical assessment has been frustrated due to the long testing times of psychophysical assessments (Mansouri et al., 2008). To examine the role of amblyopia and strabismus in binocular contrast summation, we therefore measured the full monocular and binocular CSFs with the quick CSF method (Lesmes et al., 2010; Dorr et al., 2013) in amblyopes, subjects with strabismus but not amblyopia (who were either able or not to fuse at near test distances), and normally-sighted controls.

Methods

Participants

The study design included three groups: patients with: (1) strabismic, anisometropic, or mixed amblyopia (AMB); (2) strabismus without amblyopia (SWA); and (3) normally sighted individuals (NSC). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were:

Clinical amblyopia is often defined as at least 0.2 logMAR interocular difference in acuity with best correction. Here, we adopted the clinical definition of amblyopia for our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Strabismic amblyopia was defined as a ≥0.2 logMAR interocular difference in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Strabismus was defined as angular deviation between eyes of 5–50 prism diopters at either near or far viewing distances. Anisometropic amblyopia was defined as a 2-line or greater interocular difference (≥0.2 logMAR) in BCVA with tropia ≤4 prism diopters.

Strabismus without amblyopia was defined as ≤0.2 logMAR difference between the monocular BCVAs. Strabismus was defined as above. Intermittent strabismus with near fusion was defined as ≤4 prism diopters at 40 cm test distance.

Normal vision was defined as BCVA ≤0.0 logMAR or uncorrected VA ≤0.2 logMAR for both eyes without any latent or manifest ocular deviation other than phorias within normal limits.

Subjects with any known cognitive or neurological impairments were excluded.

Informed consent was obtained from subjects or (in addition to subjects’ assent) from the parents or legal guardian of subjects aged <18 years, in accordance with procedures approved by the IRB of Boston Children’s Hospital and complying with the Declaration of Helsinki. Enrolled patients underwent complete clinical examination, including best corrected visual acuity (ETDRS charts, letter-by-letter scoring was used), cycloplegic refractive error, stereopsis (Titmus Fly SO-001), ocular motility, binocular fusion (a Worth 4 dot test) and cover test at near and distance fixation. The angle of any heterotropia or heterophoria was measured by prism-and-cover test at near and distance fixation. We only report the measurements made at near fixation, which is relevant to the 60 cm viewing distance of CSF assessment. Minimum participant age was 5 years and all participants were able to perform letter acuity assessment. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. All subjects were tested with best-corrected vision in the CSF test; as can be seen in Table 1, there was some overlap of visual acuities between the groups (i.e., one out of 11 amblyopic eyes had better acuity than three normal eyes but with interocular difference ≥0.2 logMAR). For consistency across groups, hereafter we term the amblyopic eye and fellow eye as the non-dominant eye (NDE) and dominant eye (DE), respectively. The DE was determined by the results from clinical binocular function or acuity test (for AMB and SWA subjects) or finger pointing task (for NSC).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Amblyopia | Strabismus | Normal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 11) | (N = 20) | (N = 24) | |||

| Age (years) | mean (±SD) | 15.9 (±16.2) | 19.9 (±20.4) | 18.7 (±10.8) | |

| min:median:max | 6:9:50 | 5:9.5:68 | 5:17:43 | ||

| Gender | ratio (female:male) | 5:6 | 13:7 | 11:13 | |

| Visual Acuity (logMAR) | mean (±SD) | non-dominant eye | 0.55 (±0.35) | 0.09 (±0.11) | 0.01 (±0.08) |

| dominant eye | 0.02 (±0.09) | 0.05 (±0.09) | −0.04 (±0.08) | ||

| min:median: max | non-dominant eye | 0.14:0.48:1.30 | −0.08:0.12:0.30 | −0.12:0:0.18 | |

| dominant eye | −0.12:0:0.18 | −0.10:0.02:0.20 | −0.22/−0.02/0.10 | ||

| Angular Deviation (prism diopter) | mean (±SD) | 10.2 (±14.8) | 17.3 (±14.0) | Neither manifest | |

| nor latent | |||||

| deviation | |||||

| min:median:max | 0:4:45 | 4:10:50 | |||

| Ability to fuse | N = 5 | N = 7 | N = 24 | ||

| Strabismus type (intermittent) | NA | esotropia 7 (0) | NA | ||

| exotropia 6 (4) | |||||

| esophoria 4 (2) | |||||

| exophoria 3 (0) |

Procedure

Spatial CSFs were assessed with the quick CSF method (Lesmes et al., 2010) and a 10-AFC letter recognition task (Hou et al., 2015) implemented on a tablet computer (Dorr et al., 2013). The quick CSF method is a Bayesian adaptive procedure that takes advantage of prior knowledge about the general shape of the CSF and searches the 2D stimulus space (contrast and spatial frequency) to find stimuli for future trials that maximize information about the subject’s individual CSF.

The CSF maps a spatial frequency f to a sensitivity S by a truncated log-parabola S(f, θ) that is based on a log-parabola S0(f,θ). The parameter vector Θ has four dimensions: (i) peak gain, γmax; (ii) peak spatial frequency, fmax; (iii) bandwidth, β; and (iv) low-frequency truncation level, δ.

The quick CSF also provides two important scalar features: (i) a summary statistic, the area under the log CSF (AULCSF; Applegate et al., 1998) (ii) and the high spatial-frequency cut-off (CSF Acuity). Test letters were band-pass filtered Sloan letters with peak frequency of 0.64–41 cycles per degree (cpd) at the viewing distance of 60 cm. Each of 25 trials began with a 500 ms white bounding box cueing the size and location of the upcoming stimulus. Then, the target letter was presented for 2 s followed by a response interval. The experimenter entered the subject’s response using a keyboard, which initiated a subsequent trial. No feedback was provided.

In random order, the CSF was measured binocularly and monocularly with each eye while the non-tested eye was occluded with an eye patch.

Data Analysis

During data recording, the quick CSF was initialized with a uniform prior. After data collection, all data sets were rescored with a more informative population prior (Dorr et al., 2017). As a summary statistic of binocular summation, we calculated the ratio of contrast sensitivity of the binocular to that of the dominant eye (AULCSFBinocular/AULCSFDE). For a finer-level analysis, we used the probability summation model, which is the simplest and most commonly used account in vision and hearing science (Dubois et al., 2013), as a theoretical yardstick. First, observers’ thresholds for the NDE, DE, and binocular viewing conditions were each converted into the probability of detecting a target signal given the assumed psychometric function (Pelli, 1987; Klein, 2001; Dubois et al., 2013; Equation 1). This function P(c, τ) describes the probability of a correct response as a function of signal contrast c and threshold contrast τ:

| (1) |

where γ is guessing rate (= 0.1 for this 10-AFC paradigm), λ is the lapse rate, β is the slope of P (here, β = 0.25), and Φ is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution. This conversion was made as a function of spatial frequency and the final probability for each viewing condition (non-dominant eye PNDE, dominant eye PDE, and binocular viewing PBinocular) was the mean probability across spatial frequencies. Next, we computed the expected probability summation derived from the probabilistic summation of monocular signals from the non-dominant and dominant eyes as shown in Equation 2.

| (2) |

where P is the probability of detecting a target signal (corrected for the guessing rate of 10% by subtracting 0.1 from each term on the right-hand side and dividing by 0.9; for the left-hand side, this correction was inverted). We then compared this expected probability summation value PExpected Binocular to the probability of binocular viewing condition PBinocular.

The posterior of the quick CSF provides a probability distribution over possible CSFs and their agreement with the data. We used the width of the credible interval, which encompasses 68.3% of the data, as a proxy to test-retest variability (Hou et al., 2016).

For statistical tests, we used a significance level of 0.05. Because a p-value tells us only how probable the observed outcome would be under the null hypothesis, but nothing about the relative probabilities for the null and H1, we also report the false positive risk (FPR) for an assumed uniform prior (Colquhoun, 2014). For example, consider the comparison of summary statistic AULCSF between non-dominant eyes of the AMB subgroup (observed distribution of mean = 0.99, SD = 0.467) and NSC eyes (mean = 1.65, SD = 0.147). We then sampled 100,000 population samples (n = 11, the number of amblyopes) from normal distributions DAMB and DNSC with these parameters, and calculated how often the originally observed p-value of approximately 0.0009 would occur when comparing the observed distribution of NSC eyes against data under the null hypothesis (MNSC = 3 times; note that this is different from the p-value *100,000 = ~90 simulations where the effect size was at least as big as the originally observed effect) or a hypothesized true effect (MAMB = ~1,000). The ratio MNSC/(MNSC+MAMB), which is influenced by statistical power of the experiment and the observed effect size and p-value, then gives us the FPR that we would see if the observed outcome was due to the null hypothesis being true; here, FPR = 0.003.

Results

Data are publicly available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/3XWZUN.

Method Validation

The mean time to complete each quick CSF test was 170 (± 34) s, see Supplementary Figure S1. There was no effect of age on the reliability of quick CSF measurements, see Supplementary Figure S2.

Monocular Contrast Sensitivity Deficit in Amblyopia

We first analyzed the four parameter values of the quick CSF and its two summary estimates, AULCSF and CSF Acuity for the three groups.

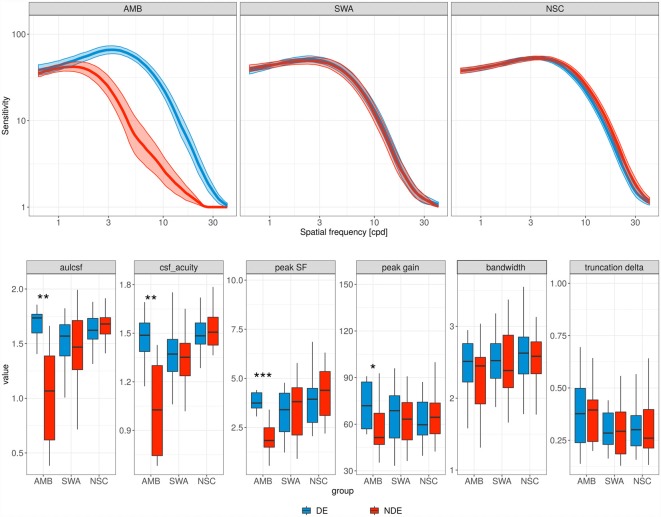

The contrast sensitivity deficits of AMB patients can be seen in Figure 1, which shows average CSFs over the different groups, as well as boxplots of the CSF parameter distributions: the CSF for the non-dominant eye (red curve) is diagonally shifted downward and to the left of the dominant eye (blue curve).

Figure 1.

Contrast sensitivity functions (CSFs). Top row, each panel contains the mean CSF of the non-dominant eye (red curve) and the dominant eye (blue curve) for the different subject groups. AMB, amblyopia; SWA, strabismus without amblyopia; NSC, normally sighted controls. Shaded areas represent ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). Bottom row, parameter distributions of the observed CSFs. Boxplot midlines indicate median values; “*”, “**,” and “***” denote statistical significance (two-sided Wilcoxon test) at the alpha level of 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively.

More specifically, the AMB group showed a significant reduction in peak SF (from 3.89 to 1.94 cyc/deg; p = 0.001, Wilcoxon test; FPR = 0.002) and peak gain (from 1.89 to 1.77 log10 sensitivity; p = 0.032; FPR = 0.146) for the non-dominant eye. However, no significant difference was observed in bandwidth and in low SF truncation (p = 0.32 and p = 0.64, respectively), and SWA and NSC did not show a significant difference between the two eyes for any of the parameters.

The changes in peak SF and peak gain for the AMB group resulted in a pronounced AULCSF deficit in the non-dominant (but not dominant) eye relative to the NSC group (mean 1.68 and 0.99 vs. 1.65 log10 units; p = 0.608 and p ≪ 0.001 (FPR = 0.003), respectively; two-sided t-test). AULCSF and CSF Acuity were also significantly lower in the non-dominant relative to the dominant eye (p < 0.01; FPR = 0.011 and 0.032, respectively) of AMB.

Binocular Contrast Summation

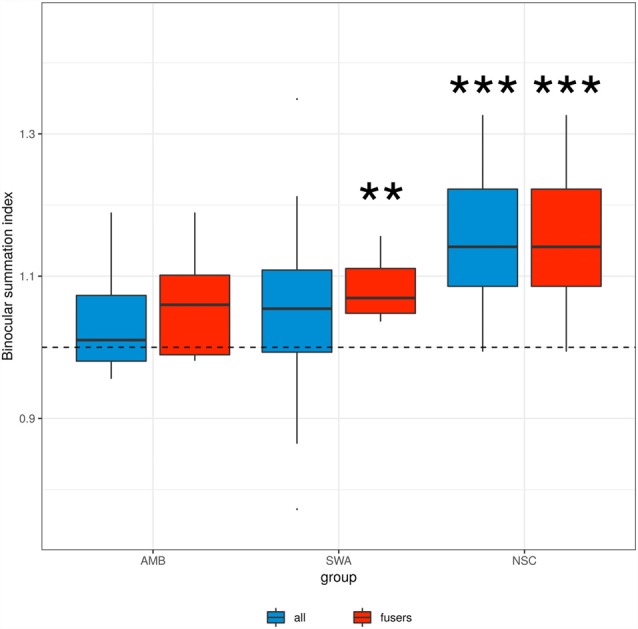

Figure 2 shows binocular summation index distributions. While NSC subjects show evidence of binocular contrast summation (p ≪ 0.001, t-test; FPR ≪ 0.001), there was no such evidence for AMB (p = 0.14) or SWA (p = 0.09), when all subjects were included in the analysis (blue boxes).

Figure 2.

Binocular summation index. Binocular summation was evaluated as the ratio of contrast sensitivity of binocular vision to that of the dominant eye (AULCSF Binocular/AULCSFDE). Blue boxes indicate the data from all subjects in each group, red boxes indicate the data from the subset of amblyopic and strabismic subjects who are able to fuse at the testing distance. “**” and “***” denote statistical significance (two-sided t-test) at the alpha level of 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. SWA subjects who were able to fuse and NSC subjects showed an index significantly greater than 1, i.e., binocular summation.

In principle, a lack of binocular summation may be due to disparate retinal correspondence that resulted from ocular misalignment of the strabismic vision rather than an absence of neural summation (Thorn and Boynton, 1974). Thus, we looked at those patients who were able to fuse their eyes at the testing distance. As shown by the red boxes in Figure 2, there remained a lack of binocular contrast summation for this AMB subgroup (p = 0.17). The summation index was significantly greater than 1 in SWA subjects who were able to fuse (p < 0.003, t-test; FPR = 0.013). These results suggest that in strabismus, the lack of binocular summation is a direct consequence of ocular misalignment, whereas in amblyopia there is an additional fundamental developmental deficit in binocular vision.

Understanding the Mechanism of Binocular Combination

It has been shown that the degree of binocular summation is greatly diminished with increasing interocular sensitivity difference (Marmor and Gawande, 1988; Pardhan and Gilchrist, 1990; Cagenello et al., 1993; Pardhan, 1993; Pineles et al., 2011) and depends on spatial frequency (Pardhan, 1996). We, therefore, compared the level of binocular contrast summation observed with the prediction of a probability summation model for independent sensory inputs.

We converted contrast sensitivity for the binocular condition of each observer to contrast detection threshold (probability correct 0.53) at 1,000 spatial frequencies (0.64~41 cpd). Based on (Equation 1), we computed the probability of a correct response at that contrast in the monocular conditions. These probabilities were averaged across spatial frequencies. Lastly, we computed the expected binocular detection probability based on the probability summation of the monocular detection probabilities (Equation 2).

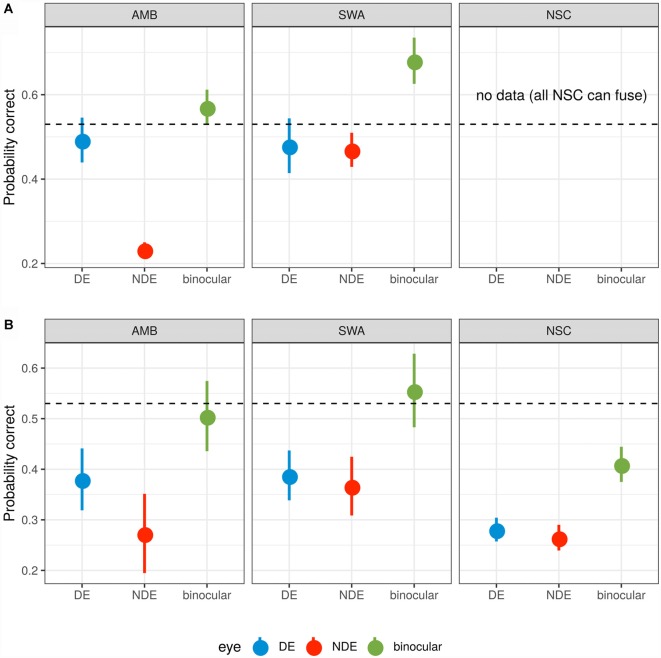

Data points in Figure 3 show the probability of target detection in each viewing condition. Dotted lines indicate the observed binocular target detection probability (0.53). As expected, AMB exhibited considerable difference in target detection probability between both eyes (p < 0.01, Wilcoxon test; FPR = 0.079) while SWA and control groups did not show any significant differences between the two eyes (all p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Probability summation. (A) Subjects who were unable to fuse the two monocular images. (B) Subjects who were able to fuse. The dotted line indicates 53% threshold for binocular target identification. For the average contrast needed to reach this binocular threshold, monocular detection probabilities are shown for the non-dominant (red) and the dominant (blue) eye. Based on probabilistic summation of each eye’s target detection probability, the expected probability for the binocular condition is shown in green. A value below the dotted line indicates that actual binocular summation exceeds probabilistic summation. A value above the dotted line indicates that the monocular images inhibit one another so that performance is worse than expected from target detection by independent monocular mechanisms. Error bars represent ±1 SEM.

For AMB subjects (with and without the ability to fuse the monocular images) and those SWA subjects that were able to fuse (Figure 3 top left and bottom row, left and center), the observed binocular contrast summation did not differ from that predicted from simple probability summation (all p > 0.05, t-test). Binocular summation of NSC subjects, however, was significantly greater than predicted from the probability summation (p < 0.008; FPR = 0.020). For the subset of SWA subjects who were unable to fuse (Figure 3A center), this pattern reversed and binocular summation was significantly impaired relative to probability summation (p < 0.02; FPR = 0.088).

Relationship Between Visual Acuity and CSF Parameters

There were significant correlations between logMAR acuity and quick CSF measures both for the non-dominant eye and for interocular differences with r2 values between 0.54 and 0.65 (all p ≪ 0.001). Variability of logMAR acuity can be well-accounted for by log CSF Acuity (r2 = 0.64). Slightly less accountability (r2 = 0.55) was observed in the regression of logMAR acuity on AULCSF (see Supplementary Figure S3).

Discussion and Conclusion

Amblyopia is associated with anomalies in contrast sensitivity (Howell et al., 1983; McKee et al., 2003). Consistent with earlier findings, the present study demonstrates that individuals with amblyopia show a significant loss of contrast sensitivity in the non-dominant eye while the CSF of the dominant eye appears to be normal. By examining the CSF parameters, we show that the overall reduction in the CSF of the amblyopic eye was largely explained by significantly reduced peak spatial frequency and gain in the non-dominant eye. Because bandwidths stayed the same, sensitivity was lost particularly at high spatial frequencies. When we examined the monocular CSFs of SWA patients, we found no such differences in their monocular CSFs.

We also measured the deficits in binocular contrast sensitivity in AMB and SWA subjects. The superiority of binocular over monocular viewing is well documented in normal vision (Campbell and Green, 1965; Blake and Fox, 1973; Thorn and Boynton, 1974; Legge, 1984a). Binocular summation is often quantified as the ratio of binocular sensitivity to monocular sensitivity. While log probability summation for two equally detectable signals is approximately a factor of 1.2 (Tyler and Chen, 2000), many studies have shown that binocular contrast sensitivity is approximately 40% greater than monocular sensitivity (Legge, 1984b; Anderson and Movshon, 1989; Tyler and Chen, 2000; Meese et al., 2006; Baker et al., 2007b). Our NSC results are in good agreement with these estimates of binocular summation. Because this binocular performance enhancement exceeds the expected improvement from probability summation alone, it has been believed that this enhancement likely reflects neural summation (Campbell and Green, 1965; Blake and Fox, 1973; Bacon, 1976; Legge, 1984b; Anderson and Movshon, 1989).

Binocular contrast summation diminishes as interocular sensitivity difference increases (Marmor and Gawande, 1988; Pardhan and Gilchrist, 1992; Jiménez et al., 2004; Pineles et al., 2013, 2015a). Thus, without compensating for the difference in sensitivity between the two eyes, binocular contrast summation in amblyopia is either absent or greatly compromised (Levi et al., 1979, 1980; Pardhan and Gilchrist, 1992; Baker and Meese, 2007). Consistent with previous findings for binocular acuity summation (Jiménez et al., 2004), our results confirmed the lack of binocular contrast summation (Lema and Blake, 1977; Levi et al., 1980; Sireteanu et al., 1981; Hess et al., 2014) in AMB subjects. We further show that binocular contrast summation is impaired in those SWA subjects who were unable to fuse at near distances; SWA subjects who were able to fuse, on the other hand, did exhibit significant binocular summation. These findings are in good agreement with studies showing that binocular acuity summation is greater in subjects with greater control over intermittent exotropia (Yulek et al., 2017) and that strabismus surgery to align the eyes can lead to improvements in binocular vision (Pineles et al., 2015a; Kattan et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2017).

We also used the monocular and binocular psychometric functions to estimate probability summation. The results confirmed the analyses of dominant eye and binocular AULCSF; the binocular contrast sensitivity of AMB or SWA subjects who were able to fuse was consistent with simple probability summation between independent detectors. This indicates an impairment of binocular contrast vision. Moreover, for SWA subjects who were unable to fuse at near distances, binocular contrast sensitivity was worse than expected from probability summation, suggesting an inhibitory process that impairs the combination of monocular sensitivity. These results are in good agreement with previous studies showing inhibition of binocular acuity summation in strabismic observers (Pineles et al., 2013, 2014a).

The use of the probability summation model allowed us to evaluate mechanisms of binocular interactions based on monocular and binocular CSFs when the two eyes have drastically different sensitivities. The method can be extended directly to many other visual conditions, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma, and cataract. It can also be extended to other measures of visual function, such as monocular and binocular visual acuity, and monocular and binocular perimetry.

In conclusion, our results suggest that monocular and binocular contrast sensitivity deficits define important characteristics of amblyopia and strabismus that are not captured by visual acuity alone. Furthermore, our results identify a key role of fusion in binocular summation. Finally, measurement of both the monocular and binocular CSFs was possible rapidly and reliably even in young children, which may allow clinicians to more accurately assess individual patients’ functional contrast sensitivity and acuity outcomes and prognosis.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with procedures approved by the IRB of Boston Children’s Hospital with written informed consent from all subjects or (in addition to subjects’ assent) from the parents or legal guardian of subjects aged <18 years. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the IRB of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Author Contributions

MYK, MK, KC, DH, Z-LL, and PB contributed to the conception and design of the study. AM collected the data and organized the database. MD, MYK, and LL analyzed the data. MD and PB wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

MD, LL, Z-LL, and PB have intellectual property in quick CSF assessment and equity in Adaptive Sensory Technology (AST), a company that aims to commercialize the quick CSF; LL also holds employment at AST. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 EY021553 and by the Elite Network Bavaria, funded by the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) in the framework of the Open Access Publishing Program.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00234/full#supplementary-material

References

- Anderson P. A., Movshon J. A. (1989). Binocular combination of contrast signals. Vision Res. 29, 1115–1132. 10.1016/0042-6989(89)90060-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate R. A., Howland H. C., Sharp R. P., Cottingham A. J., Yee R. W. (1998). Corneal aberrations and visual performance after radial keratotomy. J. Refract. Surg. 14, 397–407. 10.3928/1081-597x-19980701-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon J. H. (1976). The interaction of dichoptically presented spatial gratings. Vision Res. 16, 337–344. 10.1016/0042-6989(76)90193-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. H., Meese T. S. (2007). Binocular contrast interactions: dichoptic masking is not a single process. Vision Res. 47, 3096–3107. 10.1016/j.visres.2007.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. H., Meese T. S., Mansouri B., Hess R. F. (2007a). Binocular summation of contrast remains intact in strabismic amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 5332–5338. 10.1167/iovs.07-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. H., Meese T. S., Summers R. J. (2007b). Psychophysical evidence for two routes to suppression before binocular summation of signals in human vision. Neuroscience 146, 435–448. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry J.-C., König H.-H. (2003). Test characteristics of orthoptic screening examination in 3 year old kindergarten children. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 87, 909–916. 10.1136/bjo.87.7.909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R., Fox R. (1973). The psychophysical inquiry into binocular summation. Percept. Psychophys. 14, 161–185. 10.3758/bf03198631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley A., Freeman R. D. (1981). Contrast sensitivity in anisometropic amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 21, 467–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagenello R., Arditi A., Halpern D. L. (1993). Binocular enhancement of visual acuity. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 10, 1841–1848. 10.1364/josaa.10.001841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell F. W., Green D. G. (1965). Monocular versus binocular visual acuity. Nature 208, 191–192. 10.1038/208191a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascairo M. A., Mazow M. L., Holladay J. T., Prager T. (1997). Contrast visual acuity in treated amblyopia. Binocul. Vis. Strabismus Q. 12, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. Y., Demer J. L., Isenberg S. J., Velez F. G., Pineles S. L. (2017). Decreased binocular summation in strabismic amblyopes and effect of strabismus surgery. Strabismus 25, 73–80. 10.1080/09273972.2017.1318153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M. P. (2010). Review of amblyopia treatment: are we overtreating children with amblyopia? Br. Ir. Orthopt. J. 7, 3–7. 10.22599/bioj.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1981). Screening results on the ocular status of 651 prekindergarteners. Am. J. Optom. Physiol. Opt. 58, 648–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. (2014). An investigation of the false discovery rate and the misinterpretation of p-values. R. Soc. Open Sci. 1:140216. 10.1098/rsos.140216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter S. A., Foster N. C., Holmes J. M., Melia B. M., Wallace D. K., Repka M. X., et al. (2012). Optical treatment of strabismic and combined strabismic-anisometropic amblyopia. Ophthalmology 119, 150–158. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr M., Lesmes L. A., Elze T., Wang H., Lu Z.-L., Bex P. J. (2017). Evaluation of the precision of contrast sensitivity function assessment on a tablet device. Sci. Rep. 7:46706. 10.1038/srep46706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr M., Lesmes L. A., Lu Z.-L., Bex P. J. (2013). Rapid and reliable assessment of the contrast sensitivity function on an iPad. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 7266–7273. 10.1167/iovs.13-11743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M., Poeppel D., Pelli D. G. (2013). Seeing and hearing a word: combining eye and ear is more efficient than combining the parts of a word. PLoS One 8:e64803. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresina M., Campos E. C. (2014). A 1-year review of amblyopia and strabismus research. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 3, 379–387. 10.1097/APO.0000000000000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann L., Biedner B., David R., Sachs U. (1980). Screening for refractive errors, strabismus and other ocular anomalies from ages 6 months to 3 years. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 17, 315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fronius M., Sireteanu R. (1989). Monocular geometry is selectively distorted in the central visual field of strabismic amblyopes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 30, 2034–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff M. J., Suhr A. W., Ward J. A., Croley J. K., O’Hara M. A. (2006). Effect of adult strabismus on ratings of official U.S. Army photographs. J. AAPOS 10, 400–403. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham P. A. (1974). Epidemiology of strabismus. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 58, 224–231. 10.1136/bjo.58.3.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunton K. B., Brown A. (2012). Prism use in adult diplopia. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 23, 400–404. 10.1097/icu.0b013e3283567276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrad R. (1996). Psychophysics of suppression. Eye 10, 270–273. 10.1038/eye.1996.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatt S. R., Mohney B. G., Leske D. A., Holmes J. M. (2008). Variability of control in intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology 115, 371.e2–376.e2. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helveston E. M. (2010). Understanding, detecting and managing strabismus. Community Eye Health 23, 12–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F. (1991). The site and nature of suppression in squint amblyopia. Vision Res. 31, 111–117. 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90078-j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F. (2001). Amblyopia: site unseen. Clin. Exp. Optom. 84, 321–336. 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2001.tb06604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F., Campbell F. W., Greenhalgh T. (1978). On the nature of the neural abnormality in human amblyopia; neural aberrations and neural sensitivity loss. Pflugers Arch. 377, 201–207. 10.1007/bf00584273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F., Demanins R. (1998). Contour integration in anisometropic amblyopia. Vision Res. 38, 889–894. 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00233-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F., Howell E. R. (1977). The threshold contrast sensitivity function in strabismic amblyopia: evidence for a two type classification. Vision Res. 17, 1049–1055. 10.1016/0042-6989(77)90009-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F., McIlhagga W., Field D. J. (1997). Contour integration in strabismic amblyopia: the sufficiency of an explanation based on positional uncertainty. Vision Res. 37, 3145–3161. 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess R. F., Thompson B., Baker D. H. (2014). Binocular vision in amblyopia: structure, suppression and plasticity. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 34, 146–162. 10.1111/opo.12123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopigian K., Blake R., Greenwald M. J. (1986). Selective losses in binocular vision in anisometropic amblyopes. Vision Res. 26, 621–630. 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopigian K., Blake R., Greenwald M. J. (1988). Clinical suppression and amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 29, 444–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou F., Lesmes L., Bex P., Dorr M., Lu Z.-L. (2015). Using 10AFC to further improve the efficiency of the quick CSF method. J. Vis. 15:2. 10.1167/15.9.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou F., Lesmes L. A., Kim W., Gu H., Pitt M. A., Myung J. I., et al. (2016). Evaluating the performance of the quick CSF method in detecting contrast sensitivity function changes. J. Vis. 16:18. 10.1167/16.6.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell E. R., Mitchell D. E., Keith C. G. (1983). Contrast thresholds for sine gratings of children with amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 24, 782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Tao L., Zhou Y., Lu Z.-L. (2007). Treated amblyopes remain deficient in spatial vision: a contrast sensitivity and external noise study. Vision Res. 47, 22–34. 10.1016/j.visres.2006.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-B., Zhou J., Lu Z.-L., Zhou Y. (2011). Deficient binocular combination reveals mechanisms of anisometropic amblyopia: signal attenuation and interocular inhibition. J. Vis. 11:4. 10.1167/11.6.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S., Harrad R. A., Morris M., Rumsey N. (2006). The psychosocial benefits of corrective surgery for adults with strabismus. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90, 883–888. 10.1136/bjo.2005.089516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson P., Kvarnström G., Abrahamsson M., Bjernbrink-Hörnblad E., Sunnqvist B. (2002). The frequency of amblyopia among visually impaired persons. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 80, 44–46. 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. R., Ponce A., Anera R. G. (2004). Induced aniseikonia diminishes binocular contrast sensitivity and binocular summation. Optom. Vis. Sci. 81, 559–562. 10.1097/00006324-200407000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattan J. M., Velez F. G., Demer J. L., Pineles S. L. (2016). Relationship between binocular summation and stereoacuity after strabismus surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 165, 29–32. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. L., Buckingham T. J. (1998). Movement hyperacuity in childhood amblyopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 82, 991–995. 10.1136/bjo.82.9.991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiorpes L., Tang C., Movshon J. A. (1999). Factors limiting contrast sensitivity in experimentally amblyopic macaque monkeys. Vision Res. 39, 4152–4160. 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00130-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschen D. G., Flom M. C. (1978). Visual acuity at different retinal loci of eccentrically fixating functional amblyopes. Am. J. Optom. Physiol. Opt. 55, 144–150. 10.1097/00006324-197803000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S. A. (2001). Measuring, estimating, and understanding the psychometric function: a commentary. Percept. Psychophys. 63, 1421–1455. 10.3758/bf03194552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvarnström G., Jakobsson P., Lennerstrand G. (2001). Visual screening of Swedish children: an ophthalmological evaluation. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 79, 240–244. 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2001.790306.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M., Wiecek E., Dakin S. C., Bex P. J. (2015). Spatial-frequency dependent binocular imbalance in amblyopia. Sci. Rep. 5:17181. 10.1038/srep17181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. E. (1984a). Binocular contrast summation—I. Detection and discrimination. Vision Res. 24, 373–383. 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. E. (1984b). Binocular contrast summation—II. Quadratic summation. Vision Res. 24, 385–394. 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90064-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lema S. A., Blake R. (1977). Binocular summation in normal and stereoblind humans. Vision Res. 17, 691–695. 10.1016/s0042-6989(77)80004-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesmes L. A., Lu Z. L., Baek J., Albright T. D. (2010). Bayesian adaptive estimation of the contrast sensitivity function: the quick CSF method. J. Vis. 10, 1–21. 10.1167/10.3.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Harwerth R. S. (1977). Spatio-temporal interactions in anisometropic and strabismic amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 16, 90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Harwerth R. S. (1978). Contrast evoked potentials in strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 17, 571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Harwerth R. S., Manny R. E. (1979). Suprathreshold spatial frequency detection and binocular interaction in strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 18, 714–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Harwerth R. S., Smith E. L. (1980). Binocular interactions in normal and anomalous binocular vision. Doc. Ophthalmol. 49, 303–324. 10.1007/bf01886623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Klein S. (1982). Differences in vernier discrimination for grating between strabismic and anisometropic amblyopes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 23, 398–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Klein S. A. (1985). Vernier acuity, crowding and amblyopia. Vision Res. 25, 979–991. 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90208-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi D. M., Knill D. C., Bavelier D. (2015). Stereopsis and amblyopia: a mini-review. Vision Res. 114, 17–30. 10.1016/j.visres.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri B., Thompson B., Hess R. F. (2008). Measurement of suprathreshold binocular interactions in amblyopia. Vision Res. 48, 2775–2784. 10.1016/j.visres.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmor M. F., Gawande A. (1988). Effect of visual blur on contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmology 95, 139–143. 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33218-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. P., Levi D. M., Movshon J. A. (2003). The pattern of visual deficits in amblyopia. J. Vis. 3:5. 10.1167/3.5.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meese T. S., Georgeson M. A., Baker D. H. (2006). Binocular contrast vision at and above threshold. J. Vis. 6, 1224–1243. 10.1167/6.11.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mets M. B., Beauchamp C., Haldi B. A. (2004). Binocularity following surgical correction of strabismus in adults. J. AAPOS 8, 435–438. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojon-Azzi S. M., Mojon D. S. (2007). Opinion of headhunters about the ability of strabismic subjects to obtain employment. Ophthalmologica 221, 430–433. 10.1159/000107506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olitsky S. E., Sudesh S., Graziano A., Hamblen J., Brooks S. E., Shaha S. H. (1999). The negative psychosocial impact of strabismus in adults. J. AAPOS 3, 209–211. 10.1016/s1091-8531(99)70004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C., Sloane M. E. (1987). Contrast sensitivity, acuity, and the perception of “real-world” targets. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 71, 791–796. 10.1136/bjo.71.10.791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardhan S. (1993). Binocular performance in patients with unilateral cataract using the Regan test: binocular summation and inhibition with low-contrast charts. Eye 7, 59–62. 10.1038/eye.1993.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardhan S. (1996). A comparison of binocular summation in young and older patients. Curr. Eye Res. 15, 315–319. 10.3109/02713689609007626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardhan S., Gilchrist J. (1990). The effect of monocular defocus on binocular contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 10, 33–36. 10.1016/0275-5408(90)90127-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardhan S., Gilchrist J. (1992). Binocular contrast summation and inhibition in amblyopia. Doc. Ophthalmol. 82, 239–248. 10.1007/bf00160771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardhan S., Whitaker A. (2000). Binocular summation in the fovea and peripheral field of anisometropic amblyopes. Curr. Eye Res. 20, 35–44. 10.1076/0271-3683(200001)20:1;1-h;ft035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group . (2003). A comparison of atropine and patching treatments for moderate amblyopia by patient age, cause of amblyopia, depth of amblyopia, and other factors. Ophthalmology 110, 1632–1637; discussion 1637–1638. 10.1016/s0161-6420(03)00500-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli D. G. (1987). On the relation between summation and facilitation. Vision Res. 27, 119–123. 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90148-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Birch E. E., Talman L. S., Sackel D. J., Frohman E. M., Calabresi P. A., et al. (2011). One eye or two: a comparison of binocular and monocular low-contrast acuity testing in multiple sclerosis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 152, 133–140. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Demer J. L., Isenberg S. J., Birch E. E., Velez F. G. (2015a). Improvement in binocular summation after strabismus surgery. JAMA Ophthalmol. 133, 326–332. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Repka M. X., Yu F., Lum F., Coleman A. L. (2015b). Risk of musculoskeletal injuries, fractures, and falls in medicare beneficiaries with disorders of binocular vision. JAMA Ophthalmol. 133, 60–65. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Lee P. J., Velez F., Demer J. (2014a). Effects of visual noise on binocular summation in patients with strabismus without amblyopia. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 51, 100–104. 10.3928/01913913-20140205-02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Velez F. G., Yu F., Demer J. L., Birch E. (2014b). Normative reference ranges for binocular summation as a function of age for low contrast letter charts. Strabismus 22, 167–175. 10.3109/09273972.2014.962751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles S. L., Velez F. G., Isenberg S. J., Fenoglio Z., Birch E., Nusinowitz S., et al. (2013). Functional burden of strabismus: decreased binocular summation and binocular inhibition. JAMA Ophthalmol. 131, 1413–1419. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh M. (1958). Visual distortion in amblyopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 42, 449–460. 10.1136/bjo.42.8.449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan D., Silver R., Murray T. J. (1977). Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in multiple sclerosis—hidden visual loss: an auxiliary diagnostic test. Brain 100, 563–579. 10.1093/brain/100.3.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentschler I., Hilz R., Brettel H. (1980). Spatial tuning properties in human amblyopia cannot explain the loss of optotype acuity. Behav. Brain Res. 1, 433–443. 10.1016/s0166-4328(80)80077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robaei D., Rose K., Ojaimi E., Kifley A., Huynh S., Mitchell P. (2005). Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population-based sample of 6-year-old australian children. Ophthalmology 112, 1275–1282. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers G. L., Bremer D. L., Leguire L. E. (1987). The contrast sensitivity function and childhood amblyopia: reply. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 104, 672–673. 10.1016/0002-9394(87)90194-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross E., Murray A. L., Stead S. (1977). Prevalence of ambylopia in grade 1 schoolchildren in Saskatoon. Can. J. Public Health 68, 491–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein R. P., Cogen M. S., Cotter S. A., Daum K. M., Mozlin R. L., Ryan J. M. (2012). “Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline Care of the Patient with Strabismus: Esotropia and Exotropia,” in Reference Guide for Clinicians, ed. Rutstein R. P. (St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; ), 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield D., Keltner J. L., Morrison T. L. (1993). Psychosocial aspects of strabismus study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 111:1100. 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080096024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiman M., Gwiazda J., Li T. (2011). Non-surgical interventions for convergence insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3:CD006768. 10.1002/14651858.cd006768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebag J., Sadun A. A., Pierce E. A. (2016). Paradigm shifts in ophthalmic diagnostics. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 114:WP1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K. (2005). Amblyopia characterization, treatment, and prophylaxis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 50, 123–166. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A., Kirkland C., Silva P. A. (1984). Vision and eye problems in seven year olds: a report from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit. N. Z. Med. J. 97, 445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireteanu R. (1982). Binocular vision in strabismic humans with alternating fixation. Vision Res. 22, 889–896. 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90025-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireteanu R., Fronius M., Singer W. (1981). Binocular interaction in the peripheral visual field of humans with strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia. Vision Res. 21, 1065–1074. 10.1016/0042-6989(81)90011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstrand J. (1981). Contrast sensitivity in children with strabismic and anisometropic amblyopia. A study of the effect of treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 59, 25–34. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1981.tb06706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stayte M., Johnson A., Wortham C. (1990). Ocular and visual defects in a geographically defined population of 2-year-old children. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 74, 465–468. 10.1136/bjo.74.8.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. E., Wallace M. P., Stephens D. A., Fielder A. R., Moseley M. J., MOTAS Cooperative . (2013). The effect of amblyopia treatment on stereoacuity. J. AAPOS 17, 166–173. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon A. K., Velez F. G., Isenberg S. J., Demer J. L., Pineles S. L. (2014). Binocular inhibition in strabismic patients is associated with diminished quality of life. J. AAPOS 18, 423–426. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lasker/IRRF Initiative for Innovation in Vision Science (2018). Amblyopia: challenges and opportunities. Vis. Neurosci. 35:E009 10.1017/s0952523817000384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. R., Woodruff G., Hiscox F. A., Strong N., Minshull C. (1991). The incidence and prevalence of amblyopia detected in childhood. Public Health 105, 455–462. 10.1016/s0033-3506(05)80616-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn F., Boynton R. M. (1974). Human binocular summation at absolute threshold. Vision Res. 14, 445–458. 10.1016/0042-6989(74)90033-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler C. W., Chen C. C. (2000). Signal detection theory in the 2AFC paradigm: attention, channel uncertainty and probability summation. Vision Res. 40, 3121–3144. 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00157-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff G., Hiscox F., Thompson J. R., Smith L. K. (1994a). Factors affecting the outcome of children treated for amblyopia. Eye 8, 627–631. 10.1038/eye.1994.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff G., Hiscox F., Thompson J. R., Smith L. K. (1994b). The presentation of children with amblyopia. Eye 8, 623–626. 10.1038/eye.1994.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yulek F., Velez F. G., Isenberg S. J., Demer J. L., Pineles S. L. (2017). Binocular summation and control of intermittent exotropia. Strabismus 25, 81–86. 10.1080/09273972.2017.1318929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Jia W.-L., Chen G., Luo Y., Lin B., He Q., et al. (2017). A complete investigation of monocular and binocular functions in clinically treated amblyopia. Sci. Rep. 7:10682. 10.1038/s41598-017-11124-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.