SUMMARY

Tomato production in West Africa has been severely affected by begomovirus diseases, including yellow leaf curl and a severe symptom phenotype, characterized by extremely stunted and distorted growth and small deformed leaves. Here, a novel recombinant begomovirus from Mali, Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV), is described that, alone, causes tomato yellow leaf curl disease or, in combination with a betasatellite, causes the severe symptom phenotype. TYLCMLV is an Old World monopartite begomovirus with a hybrid genome composed of sequences from Tomato yellow leaf curl virus‐Mild (TYLCV‐Mld) and Hollyhock leaf crumple virus (HoLCrV). A TYLCMLV infectious clone induced leaf curl and yellowing in tomato, leaf curl, crumpling and yellowing in Nicotiana benthamiana and common bean, mild symptoms in N. glutinosa, and a symptomless infection in Datura stramonium. In a field‐collected sample from a tomato plant showing the severe symptom phenotype in Mali, TYLCMLV was detected together with a betasatellite, identified as Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB). Tomato plants co‐agroinoculated with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB developed severely stunted and distorted growth and small crumpled leaves. These symptoms were more severe than those induced by TYLCMLV alone, and were similar to the severe symptom phenotype observed in the field in Mali and in other West African countries. TYLCMLV and CLCuGB also induced more severe symptoms than TYLCMLV in the other solanaceous hosts, but not in common bean. The increased symptom severity was associated with hyperplasia of phloem‐associated cells, but relatively little increase in TYLCMLV DNA levels. In surveys of tomato virus diseases in West Africa, TYLCMLV was commonly detected in plants with leaf curl and yellow leaf curl symptoms, whereas CLCuGB was infrequently detected and always in association with the severe symptom phenotype. Together, these results indicate that TYLCMLV causes tomato yellow leaf curl disease throughout West Africa, whereas TYLCMLV and CLCuGB represent a reassortant that causes the severe symptom phenotype in tomato.

INTRODUCTION

Geminiviruses are plant‐infecting viruses characterized by their unique twinned icosahedral virions and circular single‐stranded DNA genomes (Harrison, 1985; Rojas et al., 2005; Seal et al., 2006). These viruses have emerged to become one of the largest and most economically important groups of plant‐infecting viruses (more than 200 recognized species; Fauquet et al., 2008), and geminivirus‐induced diseases are a major threat to worldwide vegetable production, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions of the world (Mansoor et al., 2003b, 2006; Rojas and Gilbertson, 2008; Varma and Malathi, 2003). The family Geminiviridae is divided into four genera based on genome structure, host range and insect vector (Rybicki, 1994; Stanley et al., 2005). The genus Begomovirus, which contains whitefly (Bemisia tabaci Genn.)‐transmitted geminiviruses that infect dicotyledonous plants, is the largest and most diverse genus. The remarkable emergence of begomoviruses can be attributed to the polyphagous nature of the whitefly vector and the capacity of the viruses for genetic variation, recombination and association with other single‐stranded replicons (e.g. satellite DNAs) (Rojas et al., 2005; Seal et al., 2006).

Begomoviruses can be subdivided into New and Old World members. New World members have a bipartite genome composed of two ~2.6‐kb DNA components (designated DNA‐A and DNA‐B), whereas most Old World members have a monopartite genome (~2.8 kb) that has homology with the DNA‐A component of the bipartite members. The DNA‐B component provides the factors required for cell‐to‐cell movement of the bipartite begomoviruses (reviewed in Rojas et al., 2005), whereas many monopartite begomoviruses have acquired a satellite DNA (e.g. the betasatellite), which mediates movement and/or suppresses host defences (Briddon et al., 2001; Briddon and Stanley, 2006; Jose and Usha, 2003; Kon et al., 2006; Mansoor et al., 2006; Saeed et al., 2007; Saunders et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2003).

Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are infected by more bipartite and monopartite begomoviruses (~60 species) than any other crop (Fauquet et al., 2008). This genetic diversity reflects the worldwide cultivation of the New World tomato and the independent (parallel) evolution of new tomato‐infecting begomoviruses in geographically distinct regions. In this case, a local progenitor virus is introduced into tomato, via the feeding of whiteflies, and adapts to this new host via genetic processes, including mutation, reassortment (pseudorecombination) and recombination (Duffy and Holmes, 2008; Rojas et al., 2005; Seal et al., 2006). Eventually, a new tomato‐infecting begomovirus may emerge. In addition, tomato‐infecting begomoviruses have been introduced into new geographical regions through the activities of humans. This is best exemplified by the introduction of the Old World monopartite begomovirus, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV; Navot et al., 1991), into the New World, and the subsequent establishment and spread of the virus throughout the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico and the southeastern and western USA (Brown and Idris, 2006; Polston et al., 1999; Rojas et al., 2007; Salati et al., 2002).

Compared with the high level of genetic diversity among tomato‐infecting begomoviruses, the disease symptoms induced in tomato by these viruses tend to be less diverse, consisting of varying degrees of stunted and distorted growth and leaf curling, crumpling and yellowing. This reflects a common mechanism(s) of pathogenicity, and complicates virus identification. Moreover, because the biological properties of tomato‐infecting begomoviruses can vary, the development of effective management strategies depends on an understanding of the aetiology of these diseases and virus biology. Thus, the first step in this process is the molecular characterization of the virus(es) involved.

Tomato production in West Africa has been negatively impacted by epidemics of viral diseases caused by whitefly‐transmitted begomoviruses (Zhou et al., 2008). The most common symptoms are stunted growth and small upcurled leaves with crumpling and interveinal yellowing. However, other types of symptoms are also present in the field, including a yellow leaf crumple/mottle phenotype and a severe symptom phenotype. In the latter case, infected plants are extremely stunted and distorted with compact, upright growth and small deformed leaves. Begomovirus infection in tomatoes with these symptom phenotypes has been confirmed in samples from seven West African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo) by squash blot (SB) hybridization and SB‐polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses (Zhou et al., 2008; R. L. Gilbertson et al., unpublished data). Recently, two new monopartite begomovirus species, Tomato leaf curl Mali virus (ToLCMLV) and Tomato yellow leaf crumple virus (ToYLCrV), have been shown to cause leaf curl and yellow leaf crumple symptoms, respectively, in tomatoes in Mali and other West African countries (Zhou et al., 2008).

In this article, we describe the characterization of a novel recombinant begomovirus, Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV), which is involved in the tomato begomovirus disease outbreaks in Mali. Using agroinoculation systems, we further establish that TYLCMLV causes two distinct diseases in tomato: yellow leaf curl (TYLCMLV alone) and a severe symptom phenotype (a TYLCMLV/betasatellite reassortant).

RESULTS

Molecular characterization of a novel recombinant begomovirus associated with tomato yellow leaf curl symptoms in Mali

Surveys of tomato production in Mali in 2001 and 2003 revealed begomovirus‐like symptoms, including leaf curl and yellow leaf curl, in commercial tomato plots in Banankoori, and the severe symptom phenotype in experimental plots in Sotuba. SB analysis with a general begomovirus probe confirmed begomovirus infection in representative tomato plants showing these symptoms. Using SB‐PCR and the PAL1v1978/PAV1c715 primer pair, an ~1.5‐kb fragment was amplified from a tomato plant with yellow leaf curl symptoms from Banankoori. Partial nucleotide sequences of the V1 and V2 (capsid protein, CP) open reading frames (ORFs) showed highest identities (93–96%) with those of various TYLCV isolates, whereas partial sequences of the C4 and C1 ORFs were less than 85% identical with those of TYLCV isolates and other begomoviruses (data not shown). These results suggest that this begomovirus has a recombinant genome.

A full‐length begomovirus component was amplified from this sample by PCR with overlapping primers (Patel et al., 1993), and the resulting ~2.8‐kb fragment was cloned to generate pTYML‐1.0. The cloned begomovirus component was composed of 2794 nucleotides (GenBank Accession Number AY502934), and has a genome organization typical of Old World monopartite begomoviruses [i.e. two ORFs on the viral strand corresponding to V1 and V2 (CP), and four ORFs on the complementary strand corresponding to C1 (replication‐associated protein, Rep), C2, C3 and C4]. Efforts to detect a DNA‐B component from this sample by PCR with a degenerate primer pair were unsuccessful (data not shown).

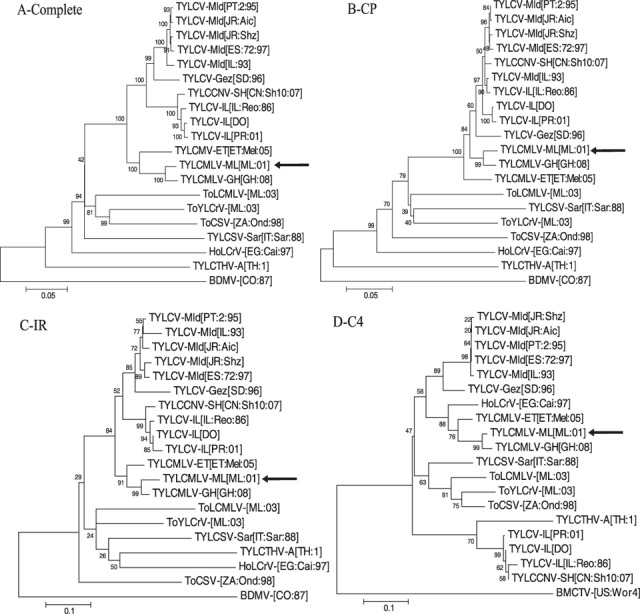

The complete nucleotide sequence of this monopartite begomovirus was ≤ 89% identical to sequences of previously characterized begomoviruses, and thus it was given the provisional name ‘Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus’. The complete TYLCMLV nucleotide sequence was most identical to those of TYLCV‐Mild (TYLCV‐Mld) isolates, whereas results of comparisons performed with individual ORFs revealed the recombinant nature of the genome (Table 1). Nucleotide sequences of the TYLCMLV V1 and V2 (CP) ORFs were 94–97% identical with those of TYLCV isolates, whereas identities for the C2 and C3 ORF sequences were slightly lower (91–92%). In contrast, the TYLCMLV C1 ORF was more divergent, with nucleotide sequence identities of 86–87% with TYLCV‐Mld isolates, 85% with ToYLCrV, 82% with Hollyhock leaf crumple virus‐[Egypt:Cairo:1997] (HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97]) and 81% with isolates of TYLCV‐Israel (TYLCV‐IL). The intergenic region (IR; sequence between the start codons of the C1 and V1 ORFs) and C4 ORF sequences were also divergent, having ≤ 82% and ≤ 85% identities, respectively, with sequences of other begomoviruses (Table 1). The C4 ORF showed the highest nucleotide (85%) and amino acid (68%) sequence identities with that of HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97]. Consistent with the results of the sequence comparisons, phylogenetic analyses performed with the complete, IR, V1 ORF and V2 (CP) ORF nucleotide sequences placed TYLCMLV in a cluster with other TYLCV isolates/species (Fig. 1, and data not shown), whereas the analysis performed with the C4 sequence placed TYLCMLV in a cluster with HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97] (Fig. 1D).

Table 1.

Percentage identities for complete and intergenic region (IR) nucleotide sequences and open reading frame nucleotide and amino acid sequences for Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus‐Mali[Mali:2001] (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]) and selected previously characterized begomoviruses.

| Begomovirus* | Total† | IR‡ | LIR | RIR | V1 | V2 (CP) | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nt | nt | nt | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | |

| TYLCMLV‐GH[GH:08] | 97 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 97 | 97 (97)§ | 97 | 97 (99) | 97 | 96 (98) | 98 | 99 (99) | 99 | 97 (99) | 97 | 95 (96) |

| TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05] | 91 | 86 | 86 | 87 | 96 | 98 (99) | 94 | 96 (99) | 91 | 94 (96) | 93 | 90 (91) | 89 | 84 (90) | 91 | 75 (78) |

| TYLCV‐Mld[PT:2:95] | 89 | 82 | 78 | 87 | 97 | 97 (99) | 95 | 98 (99) | 86 | 89 (94) | 92 | 89 (91) | 91 | 90 (93) | 83 | 63 (68) |

| TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Shz] | 89 | 82 | 79 | 86 | 97 | 97 (99) | 95 | 98 (99) | 86 | 89 (94) | 92 | 88 (90) | 91 | 90 (93) | 82 | 61 (66) |

| TYLCV‐Mld[ES:72:97] | 89 | 81 | 77 | 88 | 96 | 97 (98) | 95 | 98 (98) | 86 | 89 (94) | 91 | 87 (90) | 91 | 89 (93) | 82 | 62 (67) |

| TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Aic] | 89 | 80 | 79 | 82 | 97 | 97 (99) | 95 | 98 (98) | 86 | 89 (94) | 92 | 89 (91) | 92 | 90 (93) | 82 | 62 (67) |

| TYLCV‐Gez[SD:96] | 89 | 74 | 77 | 69 | 96 | 98 (99) | 95 | 97 (98) | 87 | 89 (94) | 92 | 89 (91) | 92 | 89 (92) | 84 | 67 (72) |

| TYLCCNV‐SH[CN:Sh10:07] | 87 | 79 | 72 | 85 | 97 | 98 (99) | 95 | 98 (99) | 81 | 83 (90) | 91 | 89 (90) | 91 | 89 (92) | 73 | 40 (43) |

| TYLCV‐IL[DO] | 87 | 79 | 71 | 88 | 97 | 98 (99) | 95 | 98 (98) | 81 | 83 (90) | 91 | 89 (91) | 91 | 89 (92) | 74 | 41 (44) |

| TYLCV‐IL[PR:01] | 86 | 77 | 70 | 85 | 96 | 97 (97) | 94 | 98 (98) | 81 | 83 (90) | 91 | 88 (90) | 91 | 89 (92) | 74 | 41 (44) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| ToYLCrV‐[ML:03] | 80 | 63 | 78 | 63 | 83 | 89 (93) | 89 | 90 (97) | 85 | 77 (86) | 86 | 79 (84) | 85 | 78 (87) | 69 | 50 (52) |

| TYLCSV‐Sar[IT:Sar:88] | 77 | 61 | 58 | 65 | 83 | 81 (87) | 82 | 90 (96) | 79 | 79 (87) | 79 | 69 (73) | 81 | 69 (81) | 74 | 57 (60) |

| ToLCMLV‐[ML:03] | 77 | 60 | 59 | 61 | 83 | 86 (91) | 82 | 86 (92) | 76 | 77 (86) | 82 | 70 (74) | 81 | 74 (84) | 65 | 43 (48) |

| ToCSV‐[ZA:Ond:98] | 77 | 62 | 66 | 58 | 81 | 84 (92) | 80 | 86 (95) | 78 | 78 (86) | 82 | 73 (79) | 84 | 78 (85) | 67 | 50 (54) |

| HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97] | 77 | 63 | 71 | 53 | 79 | 59 (71) | 69 | 86 (92) | 82 | 86 (95) | 73 | 58 (67) | 77 | 63 (71) | 85 | 68 (70) |

TYLCMLV‐GH[GH:08], TYLCMLV from Ghana; TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05], TYLCMLV from Ethiopia; TYLCV‐Mld[PT:2:95], Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV)‐Mild isolate from Portugal; TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Shz], TYLCV‐Mild isolate from Japan; TYLCV‐Mld[ES:72:97], TYLCV‐Mild isolate from Spain; TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Aic], TYLCV‐Mild isolate from Japan; TYLCV‐Gez[SD:96], TYLCV‐Gezira isolate from Sudan; TYLCCNV‐SH[CN:Sh10:07], Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus isolate from China; TYLCV‐IL[DO], TYLCV‐Israel isolate from the Dominican Republic; TYLCV‐IL[PR:01], TYLCV‐Israel isolate from Puerto Rico; ToYLCrV‐[ML:03], Tomato yellow leaf crumple virus isolate from Mali; TYLCSV‐Sar[IT:Sar:88]Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus isolate from Italy; ToLCMLV‐[ML:03], Tomato leaf curl Mali virus isolate from Mali; ToCSV‐[ZA:Ond:98], Tomato curly stunt virus isolate from South Africa; HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97], Hollyhock leaf crumple virus isolate from Egypt. Virus accession numbers are given in the legend of Fig. 1. Sequences of TYLCMLV isolates are shown above the full line, whereas sequences of TYLCV and TYLCCNV isolates are shown above the broken line.

Total represents comparisons made with complete nucleotide sequences.

IR is the intergenic region between the start codons of the C1 and V1 open reading frames (ORFs); LIR is the left IR, between the C1 start codon and stem loop (nicking site); RIR is the right IR, between the stem loop and start codon of the V1 ORF.

Numbers in parentheses indicate percentage amino acid similarity.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic consensus trees showing the relationship of Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus‐Mali [Mali:2001] (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]) with other begomoviruses based on alignments of: (A) the complete nucleotide sequence; (B) V2 (capsid protein, CP) open reading frame (ORF); (C) the intergenic region (IR; sequence between the start codons of the C1 and V1 ORFs); and (D) the C4 ORF. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with mega version 4.0 using the neighbour‐joining method, as described by Tamura et al. (2007). Branch strengths were evaluated by constructing 1000 trees in bootstrap analysis by step‐wise addition at random. Bootstrap values are shown above or below the horizontal line. Horizontal lines are in proportion to the number of nucleotide differences between branch nodes, whereas vertical lines are arbitrary. The trees were rooted with sequences from the DNA‐A component of Bean dwarf mosaic virus (BDMV‐[CO:87], M88179) or Beet mild curly top virus (BMCTV‐[US:Wor4], AY134867). Viruses, abbreviations and accession numbers are as follows: Tomato yellow leaf curl virus‐Mild (TYLCV‐Mld) isolates from Portugal (TYLCV‐Mld[PT:2:95], AF105975), Japan (TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Aic], AB014347 and TYLCV‐Mld[JR:Shz], AB014346), Spain (TYLCV‐Mld[ES:72:97], AF071228) and Israel (TYLCV‐Mld[IL:93], X76319); Tomato yellow leaf curl virus‐Gezira (TYLCV‐Gez) isolate from Sudan (TYLCV‐Gez[SD:96], AY044138); Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus (TYLCCNV) isolate from China (TYLCCNV‐SH[CH:Sh10:07], EU031444); Tomato yellow leaf curl virus‐Israel (TYLCV‐IL) isolates from Israel (TYLCV‐IL[IL:Reo:86], X15656), the Dominican Republic (TYLCV‐IL[DO], AF024715) and Puerto Rico (TYLCV‐IL[PR:01], AY134494); Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV) isolates from Ethiopia (TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05], DQ358913), Mali (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01], AY502934) and Ghana (TYLCMLV‐GH[GH:08], EU847740); Tomato leaf curl Mali virus isolate from Mali (ToLCMLV‐[ML:03], AY502936); Tomato yellow leaf crumple virus isolate from Mali (ToYLCrV‐[ML:03], AY502935); Tomato curly stunt virus isolate from South Africa (ToCSV‐[ZA:Ond:98], AF261885); Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (TYLCSV) isolate from Italy (TYLCSV‐Sar[IT:Sar:88], X61153); Hollyhock leaf crumple virus (HoLCrV) isolate from Egypt (HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97], AY036009); DNA‐A component of Tomato yellow leaf curl Thailand virus (TYLCTHV‐A[TH:1], X63015).

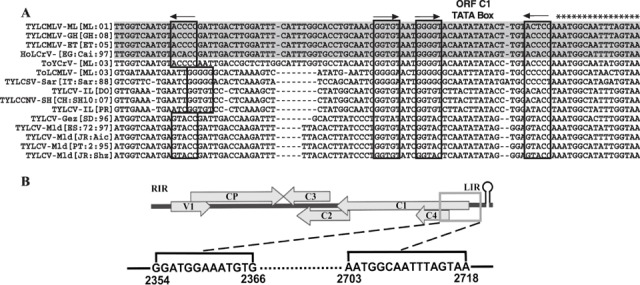

The TYLCMLV IR sequence is 320 nucleotides in length and has the characteristic geminivirus inverted repeat (stem loop) sequence and the invariant nonanucleotide sequence (TAATATT↓AC), with the nicking site for the initiation of viral strand replication (shown by the arrow). Inspection of the left intergenic region (LIR, sequence located between the C1 ATG and nicking site in the stem loop) revealed the C1 ORF TATA box, putative Rep high‐affinity binding sites (GGTGTAATGGGGT, core sequences in italic) and two inverted core repeat sequences flanking the Rep binding sites and TATA box (Fig. 2A). An alignment of partial LIR sequences further revealed that the TYLCMLV iteron elements were identical to those of HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97] and ToYLCrV‐[Mali:2003] (ToYLCrV‐[ML:03]) (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this result, the amino acid sequence of the iteron‐related domain (IRD) in the N‐terminus of the TYLCMLV Rep (MAPPKRFKIN), which is involved in the recognition of the Rep binding sites in the IR (Argüello‐Astorga and Ruiz‐Medrano, 2001), was identical to that of HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97] and ToYLCrV‐[ML:03] (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the recombinant region identified in the genome of Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus‐Mali [Mali:2001] (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]. (A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of part of the TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01] left intergenic region [LIR, between the start codon of the C1 open reading frame (ORF) and the nicking site in the stem loop] with sequences of other begomoviruses (the complete names and accession numbers of these viruses are given in the legend to Fig. 1). Iterative elements are indicated in boxes and their orientation is indicated with arrows. The sequence of the putative recombination junction in the TYLCMLV LIR is indicated with asterisks. Shaded sequences are more than 90% identical. (B) The recombinant region of TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01] is indicated by the box and sequences of putative recombination junctions are shown.

Analysis of the TYLCMLV sequence with the recombination detection program (RDP version 2.0; Martin et al., 2005) confirmed the recombinant nature of the genome, and indicated that the majority of the genome (87%) was derived from a TYLCV‐Mld isolate, with the remainder (13%) coming from a virus most similar to HoLCrV. As shown in Fig. 2B, the identified recombination junctions were nucleotides 2354–2366 (in the 5′ end of the C1/C4 ORF sequence) and 2703–2718 (in the 3′ end of LIR). Thus, the recombinant region in the TYLCMLV genome includes the 5′ portions of the C1 and C4 ORFs, which encode the N‐termini of the Rep and C4 proteins, respectively, and most of LIR, including the Rep high‐affinity binding sites (Fig. 2A and 2B). Consistent with the RDP results, the nucleotide sequences of the recombinant portions of the TYLCMLV C1 and C4 ORFs showed the highest identities, 90% and 93%, respectively, with those of HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97], whereas the sequences of the non‐recombinant portions of these ORFs were most identical with those of TYLCV‐Mld isolates (90% and 86%, respectively). Similarly, the recombinant region of the TYLCMLV LIR was 91% identical with that of HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97], whereas the non‐recombinant region of the IR (from nucleotide 2719 to the start codon of the V1 ORF) was most identical (90%) to sequences of TYLCV‐Mld isolates.

Together, these results indicate that TYLCMLV is a novel recombinant begomovirus, and support the proposed name ‘Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus’. Following the submission of the sequence of TYLCMLV‐Mali [Mali:2001] (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]), sequences of TYLCMLV isolates from Ethiopia, TYLCMLV‐Ethiopia [Ethiopia:Melkassa:2005] (TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05]), and Ghana, TYLCMLV‐Ghana [Ghana:2008] (TYLCMLV‐GH[GH:08]), were deposited in GenBank (Accession Numbers DQ358913 and EU847740, respectively). The complete sequences of TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05] and TYLCMLV‐GH[GH:08] are 91% and 97% identical, respectively, to that of TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]. These three isolates also cluster together in the phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 1), and have identical iteron sequences (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the isolates of TYLCMLV from West Africa (Mali and Ghana) are more closely related to each other than to the isolate from East Africa (Ethiopia), consistent with the geographical separation of these areas (Fig. 1; Table 1). There was also a higher level of sequence divergence between the TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05] IR, C2, C3 and C4 sequences and those of TYLCMV‐ML[ML:01] and TYLCMV‐GH[GH:08] (Table 1), which is suggestive of additional recombination events in the evolution of TYLCMLV‐ET[ET:Mel:05]. Hereafter, unless otherwise noted, TYLCMLV indicates the TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01] isolate.

Development of a TYLCMLV‐specific primer pair

Alignments of the TYLCMLV C1, C4 and IR nucleotide sequences with those of the most closely related begomoviruses, including isolates of HoLCrV, ToLCMLV, ToYLCrV and TYLCV, revealed a number of divergent regions (data not shown). A TYLCMLV‐specific primer was designed on the basis of a divergent region in the C1/C4 ORF (primer 2173v: 5′‐GACTCTAAGAGCTTCCGACT‐3′). When this primer was paired with the conserved CP primer 1000c, which anneals in a conserved region of the CP (Zhou et al., 2008), the expected ~1.6‐kb fragment was PCR amplified from DNA extracts prepared from leaves of TYLCMLV‐infected Nicotiana benthamiana or tomato plants. No fragment was amplified from equivalent extracts prepared from uninfected N. benthamiana and tomato plants, or from plants infected with TYLCV‐IL [Dominican Republic] (TYLCV‐IL[DO]; Salati et al., 2002), ToLCMLV‐[Mali:2003] (ToLCMLV‐[ML:03]) or ToYLCrV‐[ML:03]. The optimized PCR parameters for this TYLCMLV‐specific primer pair are an initial denaturing step at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 56 °C for 2 min and 72 °C for 3 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min.

Molecular characterization of a betasatellite associated with TYLCMLV

In SB‐PCR analyses with primers specific for West African tomato‐infecting begomoviruses, TYLCMLV was detected in a sample from a tomato plant with the severe symptom phenotype, which was collected in Sotuba, Mali in 2003. In a PCR analysis of this sample with the degenerate betasatellite primer pair, the expected ~1.4‐kb DNA fragment was amplified. Taken together with the finding that no betasatellite fragment was amplified from TYLCMLV‐positive tomato samples with yellow leaf curl symptoms, these results indicate that the severe symptom phenotype may be induced by a TYLCMLV/betasatellite complex.

The ~1.4‐kb fragment was cloned, and sequence analysis indicated that it was a betasatellite composed of 1346 nucleotides (Accession Number DQ136001). The TYLCMLV‐associated betasatellite has a typical genome organization, including a single complementary‐sense ORF (βC1), encoding a predicted protein of 13.6 kDa (118 amino acids), an adenine (A)‐rich region (nucleotides 720–881, 59% A residues) and a satellite conserved region (SCR). Within the SCR is the stem loop structure with the conserved begomovirus nonanucleotide sequence in the loop. Putative Rep‐binding motifs were also identified in the SCR [GGTGA (nucleotides 1207–1211), GGTGG (nucleotides 1225–1229) and GGTGT (nucleotides 1260–1264)], and these are similar or identical to those of TYLCMLV (GGTGT/GGGGT).

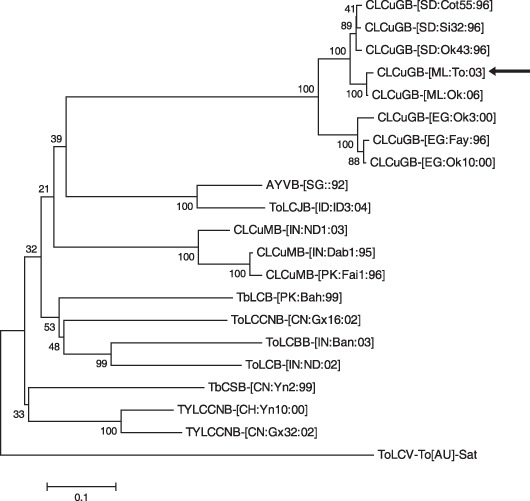

Comparisons performed with the complete nucleotide sequence of this betasatellite revealed identities of 93–99% with isolates of Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB), including 93% with an isolate from okra in Sudan (CLCuGB‐[Sudan:Sida 32:1996]) and 99% with an isolate from okra in Mali (CLCuGB‐[Mali:Okra:2006]). Consistent with this result, a phylogenetic analysis performed with complete betasatellite sequences placed the TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]‐associated betasatellite in a cluster with CLCuGBs from sub‐Saharan Africa (Fig. 3). Thus, this betasatellite is named CLCuGB [Mali:Tomato:2003] (CLCuGB‐[ML:To:03]), and hereafter is referred to as CLCuGB.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic consensus trees showing the relationship of the betasatellite associated with Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus‐Mali [Mali:2001] with other selected betasatellites based on an alignment of the complete nucleotide sequence. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with mega version 4.0 using the neighbour‐joining method, as described by Tamura et al. (2007). Branch strengths were evaluated by constructing 1000 trees in bootstrap analysis by step‐wise addition at random. Bootstrap values are shown above or below the horizontal line. Horizontal lines are in proportion to the number of nucleotide differences between branch nodes, whereas vertical lines are arbitrary. The trees were rooted with the sequence of Tomato leaf curl virus satellite DNA (ToLCV‐To[AU]‐Sat, U74627). Sequences were obtained from GenBank. Satellites, abbreviations and accession numbers are as follows: Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB) isolates from Sudan (CLCuGB‐[SD:Cot55:96], AY077797; CLCuGB‐[SD:Si32:96], AY077798; CLCuGB‐[SD:Ok43:96], AY044141), Mali (CLCuGB‐[ML:To:05], DQ136001; CLCuGB‐[ML:Ok:06], EU024122) and Egypt (CLCuGB‐[EG:Ok3:00], AF397217; CLCuGB‐[EG:Fay:96], AJ316039; CLCuGB‐[EG:Ok10:00], AF397215); Ageratum yellow vein betasatellite (AYVB) isolate from Sudan (AYVB‐[SD::92], AJ252072); Tomato leaf curl Java betasatellite (ToLCJB) isolate from Indonesia (ToLCJB‐[ID:ID3:04], AB162142); Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMB) isolates from India (CLCuMB‐[IN:ND1:03], AY438562; CLCuMB‐[IN:Dab1:95], AJ316037) and Pakistan (CLCuMB‐[PK:Fai1:96], AJ298903); Tobacco leaf curl betasatellite (TbLCB) isolate from Pakistan (TbLCB‐[PK:Bah:99], AJ316034); Tobacco leaf curl China betasatellite (ToLCCNB) isolate from China (ToLCCNB‐[CN:Gx16:02], AJ704610); Tomato leaf curl Bangalore betasatellite (ToLCBB) isolate from India (ToLCBB‐[IN:Ban:03], AY428768); Tomato leaf curl betasatellite (ToLCB) isolate from India (ToLCB‐[IN:ND:02], AJ542490); Tobacco curly shoot betasatellite (TbCSB) isolate from China (TbCSB‐[CN:Yn2:99], AJ421485); and Tomato yellow leaf curl China betasatellite (TYLCCNB) isolates from China (TYLCCNB‐[CH:Yn10:00], AJ421621 and TYLCCNB‐[CN:Gx32:02], AJ704607).

Infectivity of the cloned TYLCMLV and CLCuGB DNA

Newly replicated viral DNA forms were detected in tobacco protoplasts 3 and 5 days post‐electroporation (dpe) with the excised TYLCMLV monomer (pTYML‐1.0, data not shown), whereas no such DNA forms were observed in protoplasts electroporated with plasmid DNA alone. Approximately 18 days post‐bombardment (dpb) with the multimeric TYLCMLV clone (pTYML‐1.8), six of 14 N. benthamiana seedlings developed stunted growth and leaf upcurling, chlorosis and enations (data not shown). The presence of TYLCMLV DNA in these symptomatic plants was confirmed by PCR with the TYLCMLV‐specific primer pair. Thus, the TYLCMLV clone is replication competent and infectious.

When N. benthamiana seedlings were co‐bombarded with pTYML‐1.8 and the multimeric CLCuGB clone (pBML‐1.4), seven of 24 plants developed severely stunted growth and leaf curling, distortion, vein swelling and interveinal yellowing (data not shown). These symptoms were much more severe than those induced by TYLCMLV. In addition, plants infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB developed symptoms 4–6 days earlier than those infected with TYLCMLV alone. PCR analyses of representative symptomatic plants confirmed the presence of TYLCMLV and/or CLCuGB DNA. No symptoms developed in plants bombarded with pBML‐1.4 or gold particles, nor were viral or CLCuGB DNAs detected in these plants. These results indicated that: (i) TYLCMLV can serve as a helper virus for the associated CLCuGB; (ii) CLCuGB decreases the time for TYLCMLV symptoms to develop; and (iii) CLCuGB increases TYLCMLV disease symptom severity in N. benthamiana plants.

Host range assays

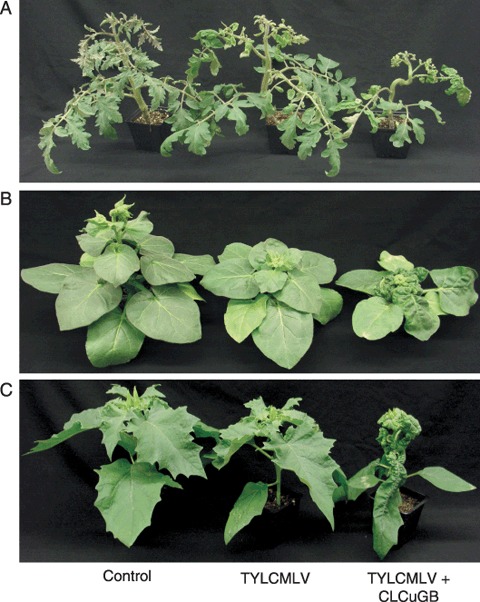

A partial host range of TYLCMLV, with and without CLCuGB, was determined using agroinoculation. Nicotiana benthamiana plants agroinoculated with TYLCMLV developed symptoms indistinguishable from those induced following particle bombardment inoculation. Tomato plants agroinoculated with TYLCMLV developed yellow leaf curl symptoms, including stunted growth and leaf upcurling and interveinal chlorosis (Fig. 4A). Agroinoculated common bean plants also developed stunted growth and leaf curling and yellowing. In N. glutinosa, TYLCMLV induced mild symptoms, including slightly stunted growth and mild leaf crumpling (Fig. 4B), whereas, in Datura stramonium, the virus induced a symptomless infection (Fig. 4C). TYLCMLV did not infect eggplant, pepper or small sugar pumpkin plants (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Disease symptoms induced in tomato (A), Nicotiana glutinosa (B) and Datura stramonium (C) plants agroinoculated with the empty vector (left), Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV) (centre), or TYLCMLV and the Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB) associated with the severe symptom phenotype in tomato (right). Plants were photographed 28 days after inoculation.

Table 2.

Host range and infectivity of Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus‐Mali[Mali:2001] (TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01]) with or without the associated Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB), as determined by agroinoculation.

| Plant/inoculum | –CLCuGB | +CLCuGB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms† | PCR‐V‡ | Symptoms | PCR‐V | PCR‐B§ | |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | 45/45** | 45/45 | 68/68 *** | 68/68 | 68/68 |

| Solanum lycopersicum cv. Glamour | 40/43** | 43/43 | 33/40 *** | 35/40 | 31/40 |

| Nicotiana glutinosa | 15/15* | 15/15 | 8/8 *** | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| Datura stramonium | 0/15 | 15/15 | 15/15 *** | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris cv. Topcrop | 12/17** | 12/17 | 12/22** | 12/22 | 7/22 |

| Capsicum annuum cv. Golden California wonder | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 |

| Cucurbita pepo cv. Small sugar | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 |

| Solanum melongena cv. Black beauty | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 |

Symptom severity is indicated as follows: no asterisk, no symptoms;

*mild symptoms;

**moderate symptoms;

***severe symptoms. Numbers in bold indicate hosts in which symptom severity was increased in the presence of CLCuGB.

PCR‐V, number of plants positive for infection by TYLCMLV‐ML[ML:01] based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses.

PCR‐B, number of plants positive for infection by CLCuGB based on PCR analyses.

When equivalent plants were co‐agroinoculated with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, there was no difference in the host range (i.e. plant species infected) or infectivity (i.e. number of plants infected/total number inoculated) compared with plants agroinoculated with TYLCMLV alone (Table 2). However, the symptoms induced by TYLCMLV and CLCuGB in TYLCMLV‐susceptible solanaceous hosts were substantially more severe than those induced by TYLCMLV alone (Table 2; Fig. 4). Thus, tomato, N. benthamiana, N. glutinosa and D. stramonium plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB developed severely stunted and distorted growth, including varying degrees of stem thickening and distortion, and vein swelling, enations, epinasty and crumpling of leaves. Interestingly, no such increase in symptom severity was observed in common bean plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, although TYLCMLV facilitated the replication and spread of the betasatellite in this host. The presence of TYLCMLV and/or CLCuGB DNA in representative symptomatic plants was confirmed by PCR analyses (Table 2). Plants agroinoculated with CLCuGB alone or an empty vector control did not develop symptoms, nor was viral or satellite DNA detected in these plants.

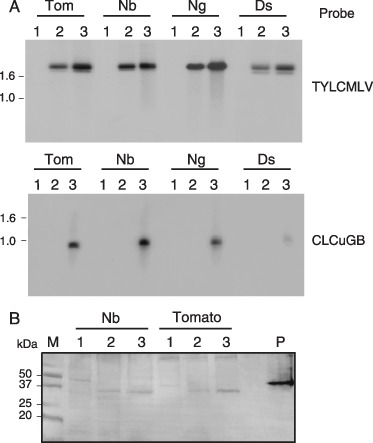

Despite the substantial increase in symptom severity in plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, Southern blot hybridization analyses revealed that viral DNA levels were only slightly elevated in the leaves of these plants, regardless of the severity of the symptoms induced by TYLCMLV alone (Fig. 5A; representative of results obtained in three independent experiments). In tomato and N. benthamiana, hosts in which TYLCMLV induces moderate to severe symptoms, viral DNA levels were increased 1.28 ± 0.22‐ and 1.15 ± 0.06‐fold, respectively, in the presence of CLCuGB. In N. glutinosa and D. stramonium, hosts in which TYLCMLV induces mild or no obvious symptoms, viral DNA levels were increased 1.28 ± 0.19‐ and 1.24 ± 0.01‐fold, respectively. Western blot analyses, performed with a TYLCV CP antiserum, revealed elevated CP levels in leaves of N. benthamiana and tomato plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB compared with those in leaves of plants infected with TYLCMLV alone (Fig. 5B). Thus, in the presence of the betasatellite, there was a relatively modest increase in viral DNA levels, together with an increased level of viral CP.

Figure 5.

Levels of Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV) DNA and capsid protein (CP) detected in tomato (Tom), Nicotiana benthamiana (Nb), N. glutinosa (Ng) and Datura stramonium (Ds) plants agroinoculated with the empty vector control (lane 1), TYLCMLV (lane 2) or TYLCMLV and the Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB, lane 3). (A) Southern blot hybridization analysis of total genomic DNA with a TYLCMLV (top) or CLCuGB (bottom) probe. (B) Western blot analysis of total leaf proteins probed with a Tomato yellow leaf curl virus CP antibody. P, recombinant Escherichia coli‐expressed TYLCV CP used as a positive control (note that the greater molecular mass of this form of the CP is caused by the histidine tag at the N‐terminus).

Tomato plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB show hyperplasia of phloem‐associated cells

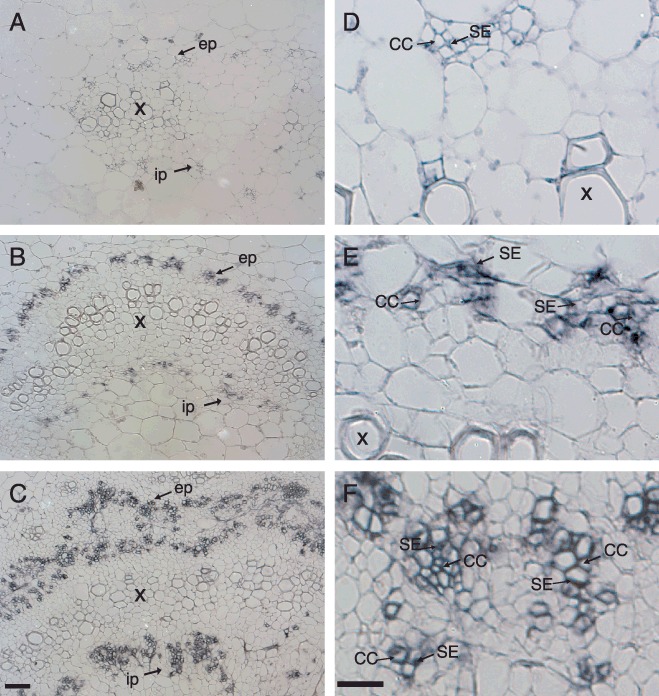

In immunolocalization experiments conducted with TYLCV CP antiserum, no signal was detected over sections prepared from the petioles and leaves of uninfected plants (Fig. 6A,D; data not shown). In equivalent tissues of plants infected with TYLCMLV alone, signal was observed over the internal and external phloem, including sieve elements and companion and phloem parenchyma cells (Fig. 6B,E). Thus, these results indicate that TYLCMLV is phloem‐limited, similar to other monopartite tomato‐infecting begomoviruses, including TYLCV‐IL[DO] (Rojas et al., 2001), Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus‐Spain [Spain:Almeria 2:1992] (Morilla et al., 2006) and Tomato leaf curl virus‐Tomato [Australia] (Rasheed et al., 2006). Moreover, the structure of the vascular tissues in TYLCMLV‐infected plants was not obviously altered in comparison with that in uninfected plants.

Figure 6.

Immunolocalization of Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus (TYLCMLV) in sections of leaf petiole tissues from tomato plants infected with TYLCMLV or co‐infected with TYLCMLV and the Cotton leaf curl Gezira betasatellite (CLCuGB) associated with a severe symptom phenotype in tomato. (A) No signal detected over a leaf petiole section from an uninfected leaf probed with TYLCV capsid protein (CP) antisera. (B) Viral signal (purple colour) detected over the phloem cells of a leaf petiole section from a TYLCMLV‐infected tomato plant. (C) Viral signal detected over phloem cells of a leaf petiole from a tomato plant co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB. Note the extensive proliferation and labelling of the phloem‐associated cells. (D–F) Close‐ups showing vascular bundles from (A–C), respectively. All images were obtained with a phase contrast light microscope at ×200 magnification for (A–C) and ×400 magnification for (D–F). Bar, 100 µm. CC, companion cells; ep, external phloem; ip, internal phloem; SE, sieve elements; X, xylem.

In the tissues of plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, viral signal was also localized over vascular tissues, and what appeared to be phloem‐associated cells. However, the structure and morphology of the phloem in these tissues were dramatically altered. There was a striking proliferation (hyperplasia) of phloem‐associated cells, which resulted in the disorganization of the structure of the phloem (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, although individual vascular bundles in uninfected or TYLCMLV‐infected plants were typically composed of four to six sieve elements and associated phloem parenchyma and companion cells, those in plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB were composed of considerably more cells, which were of an irregular size and distribution. In some cases, the hyperplasia resulted in the initiation of new bundles of phloem cells (Fig. 6C and F), leading to the establishment of a new layer of phloem‐like tissue (Fig. 6C). However, there was no evidence of cell death or necrosis in the hyperplastic phloem. Thus, the development of the severe symptom phenotype in plants co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB was associated with an abnormal proliferation of the phloem.

DISCUSSION

As part of an effort to understand the aetiology of begomovirus diseases of tomato in West Africa, we have identified and characterized a novel recombinant monopartite begomovirus, TYLCMLV, from Mali. Furthermore, we have shown that TYLCMLV induces two distinct diseases in tomato: yellow leaf curl (TYLCMLV alone) and a severe symptom phenotype (a TYLCMLV/CLCuGB reassortant). The finding of a betasatellite associated with the severe symptom phenotype in tomato is consistent with the stunted and distorted growth induced by begomovirus/betasatellite complexes in other hosts (reviewed in Briddon and Stanley, 2006). This is one of the first reports of the involvement of a betasatellite in a begomovirus disease in West Africa, and may indicate a role for these satellites in other begomovirus diseases in this region.

The finding that the majority of the TYLCMLV genome is derived from a TYLCV‐Mld isolate is consistent with: (i) the association of TYLCMLV with tomato yellow leaf curl symptoms in Mali; (ii) the induction of yellow leaf curl symptoms in tomato by the TYLCMLV infectious clone; and (iii) previous reports of TYLCV‐Mld in sub‐Saharan Africa (Fauquet et al., 2005; Idris and Brown, 2005). The relatively high level of sequence divergence of some TYLCV‐Mld sequences in the TYLCMLV genome (e.g. 91–92% identities for the C2 and C3 ORFs) probably reflects a history of geographical isolation and the high rates of mutation reported for TYLCV (Duffy and Holmes, 2008; Ge et al., 2007). The recombinant region of the TYLCMLV genome showed the highest identity (~90%) with HoLCrV‐[EG:Cai:97], indicating a recombination event with a malvaceous begomovirus. The finding that the complete TYLCMLV sequence was ≤ 89% identical with sequences of known begomoviruses placed it at the threshold for describing a new begomovirus species (Fauquet et al., 2008). However, taken together with the novel nature of the recombination event and the biological properties of the virus, our results indicate that TYLCMLV should be classified as a distinct begomovirus species. In a recent analysis of TYLCV diversity and taxonomy, a similar conclusion was reached by Abhary et al. (2007), and TYLCMLV was one of six distinct species in a ‘TYLCV cluster’. Thus, this new species is named ‘Tomato yellow leaf curl Mali virus’.

Recombination plays an important role in the evolution of begomoviruses, and can occur between TYLCV strains or species, or between TYLCV and other species (García‐Andrés et al., 2006; Idris and Brown, 2005; Monci et al., 2002; reviewed in Moriones et al., 2007). Furthermore, various regions of the viral genome can be involved in recombination (Abhary et al., 2007; Lefeuvre et al., 2007). In the case of TYLCMLV, the recombination event occurred between two begomovirus species (TYLCV‐Mld and HoLCrV), and involved the exchange of an ~360‐nucleotide fragment that included the 5′ portions of C1/C4 ORFs and most of LIR (Fig. 2B). This region is commonly exchanged in begomovirus recombination, indicating a selective advantage for such recombinants. This could be a result of the expression of a novel chimeric C4 protein that is more effective in mediating viral movement (Rojas et al., 2001) or suppressing host defences, such as gene silencing (Bisaro, 2006). Indeed, the relative capacity of C4 to suppress silencing varies among begomovirus species (Vanitharani et al., 2005), and thus the acquisition of a strong C4 suppressor could provide a selective advantage. Alternatively, exchange of the 5′ portion of the C1 ORF (encoding the Rep IRD motif) and LIR (including the Rep high‐affinity binding sites) could enhance viral replication, or perhaps even mediate an expansion of the viral host range. Another advantage could be the capacity of the recombinant begomovirus to interact with satellite DNAs, particularly betasatellites. Betasatellites are required for many Old World monopartite begomoviruses to induce characteristic disease symptoms and to attain high viral DNA levels (Briddon et al., 2001; Briddon and Stanley, 2006; Cui et al., 2004; Guo et al., 2008; Ogawa et al., 2008). Thus, the capacity to form a complex with a betasatellite can be crucial for the fitness of monopartite begomoviruses.

The finding that CLCuGB was associated with TYLCMLV in a tomato plant with the severe symptom phenotype suggests that this disease may be caused by a begomovirus/betasatellite complex. Evidence supporting this hypothesis was provided by the findings that TYLCMLV served as a helper virus for CLCuGB, and that CLCuGB substantially increased disease symptom severity in multiple hosts, including tomato. Moreover, the finding that tomatoes co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB developed a severe symptom phenotype, similar to that observed in the field in Mali and other countries in West Africa, established that this striking disease can be caused by a begomovirus/betasatellite complex. These results also demonstrate an interaction between a tomato‐infecting begomovirus and a functional betasatellite in sub‐Saharan Africa, unlike the defective satellites previously associated with Tomato leaf curl Sudan virus‐Gezira [Sudan:Gezira:1996] and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus‐Gezira [Sudan:1996] (Idris and Brown, 2005).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the interaction between TYLCMLV and CLCuGB is different from co‐evolved begomovirus/betasatellite complexes in which the betasatellite increases viral DNA levels and is required for the induction of typical disease symptoms (Briddon and Stanley, 2006). First, CLCuGB was not required for the induction of disease symptoms by TYLCMLV, nor did it substantially increase viral DNA levels. Second, CLCuGBs are typically associated with isolates of Cotton leaf curl Gezira virus (CLCuGV) in malvaceous hosts, such as cotton and okra (Idris and Brown, 2005; Mansoor et al., 2006). Consistent with this association, we have recently established that okra leaf curl disease in Mali is caused by a CLCuGV/CLCuGB complex (Kon et al., 2009). Finally, in surveys of tomato begomoviruses in West Africa, TYLCMLV was detected in tomatoes with leaf curl/yellow leaf curl symptoms from Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Senegal and Togo, whereas CLCuGB was infrequently detected and only in tomatoes with the severe symptom phenotype (data not shown). These results indicate that TYLCMLV causes tomato yellow leaf curl disease throughout West Africa, and that the association with CLCuGB is sporadic and not required for the development of this disease. Thus, the interaction between TYLCMLV and CLCuGB represents a type of reassortant, introduced into tomato by the polyphagous whitefly vector. The viability of this reassortant reflects the promiscuous nature of betasatellites (Alberter et al., 2005; Briddon and Stanley, 2006; Idris and Brown, 2005; Mansoor et al., 2003a, 2006), and may also be facilitated by the recombinant region of the TYLCMLV genome, which was derived from a malvaceous begomovirus. The frequency with which this reassortant occurs in the field will depend on a number of factors, including whitefly population densities and feeding habits, and the proximity of tomato fields and malvaceous crops and weeds. A similar interaction has been described for Tobacco curly shoot virus (TbCSV) and a betasatellite in China. Here, the betasatellite increased symptom severity in a host‐dependent manner, but did not increase viral DNA levels and was found infrequently with TbCSV in field‐collected samples (Li et al., 2005).

The finding that CLCuGB substantially increases TYLCMLV pathogenicity makes this reassortant a potentially more damaging pathogen of tomato than the virus alone. Interestingly, the increased symptom severity mediated by CLCuGB is host specific, occurring in TYLCMLV‐susceptible solanaceous hosts, but not in common bean. This may reflect a host‐specific capacity of the βC1 ORF product, a known betasatellite symptom determinant (Briddon and Stanley, 2006; Qazi et al., 2007), to mediate viral spread (Saeed et al., 2007) or to suppress gene silencing (Cui et al., 2005b; Gopal et al., 2007; Kon et al., 2007; Mansoor et al., 2006; Saeed et al., 2007). Insight into the mechanism by which CLCuGB increases symptom severity was provided by immunocytological analyses. TYLCMLV was phloem limited, similar to other monopartite tomato‐infecting begomoviruses (Morilla et al., 2006; Rasheed et al., 2006; Rojas et al., 2001). Co‐infection with CLCuGB did not release TYLCMLV from phloem limitation, but the distorted growth and vein swelling and enations in tomato leaf and petiole tissues co‐infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB were associated with extensive and abnormal proliferation (hyperplasia) of phloem‐associated cells (Fig. 6C,F). A similar situation has been reported for Beet curly top virus, in which viral C4 stimulates the proliferation of phloem‐associated cells in infected N. benthamiana plants (Latham et al., 1997). In the case of TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, this hyperplasia may be a consequence of βC1‐mediated silencing suppression perturbing small RNAs (e.g. microRNAs) involved in normal plant development (Carrington and Ambros, 2003; Cui et al., 2005a,b; Vaucheret et al., 2004).

The betasatellite‐mediated stimulation of the division of terminally differentiated phloem‐associated cells may generate more cells for viral infection, or mediate viral and betasatellite spread via division of infected cells. This notion was supported by the increased symptom severity and the extensive labelling over hyperplastic phloem tissues by CP antisera. However, the results of Southern blot hybridization analyses revealed that TYLCMLV DNA levels were not substantially increased in leaf tissues from plants showing the severe symptom phenotype. Thus, the apparent increase in virus‐infected cells observed in the hyperplastic phloem tissues may be counterbalanced by the stunted growth and abnormal development of these plants. Alternatively, the enhanced labelling by CP antisera and elevated CP levels in plants infected with TYLCMLV and CLCuGB may reflect a betasatellite‐mediated up‐regulation of CP expression or enhanced CP stability. In the latter case, this may be a result of encapsidation of CLCuGB DNA.

In conclusion, TYLCMLV is a novel recombinant begomovirus that causes two distinct diseases in tomato: yellow leaf curl (TYLCMLV alone) and a severe symptom phenotype (the TYLCMLV/CLCuGB reassortant). The severe symptom phenotype is associated with the betasatellite‐induced proliferation of phloem‐associated cells. Our findings also extend our understanding of the aetiology of tomato begomovirus diseases in West Africa: leaf curl and yellow leaf curl are caused by TYLCMLV or ToLCMLV, yellow leaf crumple is caused by ToYLCrV (Zhou et al., 2008), and the severe symptom phenotype is caused by a begomovirus/betasatellite combination, such as the TYLCMLV/CLCuGB reassortant, or mixed infections of begomoviruses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

PCR amplification and cloning of begomovirus DNA fragments

Tomatoes with virus‐like symptoms were collected from commercial fields or experimental plots in Banankoori and Sotuba, Mali during surveys conducted in June 2001 and January 2003. Leaf discs from these samples were squashed onto Hybond‐N nylon membranes in triplicate, and the membranes were returned to the University of California, Davis, CA, USA. The membranes were either hybridized with a general begomovirus probe or used in SB‐PCR analyses, as described previously (Zhou et al., 2008). DNA extracts were used in PCR with degenerate begomovirus DNA‐A (PAL1v1978 and PAV1c496 or PAV1c715) and DNA‐B (PBL1v2040 and PBV1c970) primers, as described previously (Rojas et al., 1993). PCR‐amplified DNA fragments were cloned with the TA cloning system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and sequenced as described previously (Zhou et al., 2008). An additional primer pair, TYLCV‐M602v (5′‐GTTACTCGTGGTTCCGGTAT‐3′) and TYLCV‐M2000c (5′‐GCCATGGAGACCTGATAGTA‐3′), was designed from the sequence of a cloned PCR‐amplified begomovirus fragment from a leaf sample collected from a tomato plant with yellow leaf curl symptoms in Banankoori, Mali.

Generation of infectious begomovirus clones and assessment of replication competence and infectivity

An overlapping primer pair with XbaI sites (shown in italics), TYLCV‐MXbaF (5′‐CTTCATCTAGATATTCTC‐3′) and TYLCV‐MXbaR (5′‐TATCTAGATGAAGAAAAA‐3′), was designed from the sequence of the begomovirus associated with tomato yellow leaf curl symptoms in Banankoori. This primer pair was used in PCR with proofreading DNA polymerase (PfuTurbo, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) to direct the amplification of a full‐length begomovirus DNA component, which was cloned with the pZero‐Blunt cloning system (Invitrogen). A recombinant plasmid (pTYML‐1.0) having an insert of the expected size (~2.8 kb) was identified and further characterized. A 1.8‐mer of this begomovirus DNA component was generated as described by Paplomatas et al. (1994). Here, pTYML‐1.0 was digested with EcoRV and XbaI to release an ~2.4‐kb fragment (~0.8‐mer), which was cloned into pBluescript II KS+ to generate pTYML‐0.8. The full‐length begomovirus fragment was released from pTYML‐1.0 by digestion with XbaI, and ligated into XbaI‐digested pTYML‐0.8 to generate pTYML‐1.8.

To determine the replication capacity of the cloned viral DNA, the full‐length monomer was released from pTYML‐1.0 by digestion with XbaI, and transfected into N. tabacum cv. Xanthi protoplasts, as described by Hou et al. (1998). Southern blot hybridization analysis with a TYLCMLV probe was used to detect newly replicated viral DNA forms at 0, 3 and 5 dpe. Infectivity was determined by particle bombardment inoculation of N. benthamiana seedlings at the three‐ to five‐leaf stage with pTYML‐1.8 DNA. Inoculated plants were maintained in a growth chamber kept at 28 °C, and visually inspected for disease symptoms. The presence of viral DNA in selected plants was determined by PCR with degenerate DNA‐A primers (PAL1v1978/PAV1c715) or the TYLCMLV‐specific primer pair (see below).

Detection of betasatellite DNA and construction of an infectious clone

Betasatellite DNA was detected by PCR with the primer pair Beta01 and Beta02 (Briddon et al., 2002). The expected 1.4‐kb DNA fragment was detected in a leaf sample from a tomato plant with the severe symptom phenotype collected in Sotuba, Mali. This PCR‐amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the pZero‐Blunt vector (Invitrogen). A recombinant plasmid (pBML‐1.0) having an insert of the expected size (~1.4 kb) was identified and further characterized. To generate a 1.4‐mer of the betasatellite DNA, pBML‐1.0 was digested with PstI and KpnI to release an ~540‐bp fragment (0.4‐mer), which was cloned into pBluescript II KS+ to generate pBML‐0.4. The full‐length betasatellite fragment was released from pBML‐1.0 by digestion with KpnI, and ligated into KpnI‐digested pBML‐0.4 to generate pBML1.4. Infectivity was determined by co‐bombarding N. benthamiana seedlings with pTYML‐1.8 and pBML‐1.4 DNAs. Inoculated plants were maintained in a growth chamber, and visually assessed for disease symptoms. The presence of viral and betasatellite DNA in selected plants was determined by PCR analysis.

DNA sequence and phylogenetic analyses

DNA sequencing was carried out as described previously (Seo et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008). Begomovirus and betasatellite nucleotide sequences were analysed and assembled with Vector NTI software (Version 10; Invitrogen). The blast program (National Center for Biotechnology Information) was used to make comparisons with begomovirus and betasatellite sequences in GenBank. Multiple sequence alignments were generated with the optimal alignment method of Vector NTI software. Complete sequences and those of individual ORFs and the IR were aligned with those of other begomoviruses with clustal W (1.83). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the neighbour‐joining method of mega version 4.0 with 1000 bootstrapped replicates (Tamura et al., 2007).

The RDP version 2.0 program was used to search for recombination events by the detection of potential recombined sequences, the identification of likely parents and the localization of possible recombination break points (Martin et al., 2005). The RDP settings used were as follows: multiple comparison correction off; internal reference selection; highest acceptable probability, 0.0001; window size, 10.

Generation of a virus‐specific primer pair

Divergent regions of the TYLCMLV genome were identified on the basis of sequence comparisons and visual inspection of sequence alignments. A virus‐specific virion‐sense primer was designed from one such region, and paired with a common complementary‐sense primer (1000c), designed from a conserved sequence in the CP gene (Zhou et al., 2008). Gradient PCR analyses were used to optimize the PCR conditions for the TYLCMLV‐specific primer pair.

Development of begomovirus and betasatellite agroinoculation systems

To facilitate cloning of the TYLCMLV 1.8‐mer into the binary vector, a 400‐bp PvuII fragment containing the multiple cloning site (MCS) from pSL1180 (GE Healthcare Bio‐Sciences Corporation, Piscatway, NJ, USA) was cloned into pTYML‐1.8 at a unique HincII site in the MSC of pBluescript II KS+. The resulting recombinant plasmid, pTYML1.8MCS, was linearized with NotI and cloned into the binary vector pART27 (Gleave, 1992) to generate pART27‐TYML1.8. Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain C58) transformants with pART27‐TYML1.8 were identified by PCR analysis. The pBML1.4 plasmid with the betasatellite 1.4‐mer was linearized with NsiI and cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 digested with PstI to generate pCAMBIA1300‐BML1.4. Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain C58) transformants with pCAMBIA1300‐BML1.4 were identified by PCR analysis.

Host range and infectivity assays

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains containing TYLCMLV or CLCuGB DNAs were inoculated individually or together into selected plant species to assess infectivity and host range. Two‐day‐old Agrobacterium cultures, grown in liquid Luria–Bertani (LB) medium amended with spectinomycin (200 µg/mL), were introduced into tomato (S. lycopersicum cv. Glamour), N. benthamiana, N. glutinosa, D. stramonium, common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris cv. Topcrop), eggplant (S. melongena cv. Black beauty), pepper (Capsicum annuum cv. Golden California wonder) and pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo cv. Small sugar) seedlings by needle puncture inoculation (Hou et al., 1998). Inoculated plants were maintained in a growth chamber as described above, and visually assessed for disease symptoms. Selected symptomatic plants and all symptomless plants were tested for begomovirus and betasatellite DNA by PCR analysis.

Immunolocalization

Tissues were collected from plants for immunolocalization at 4 weeks post‐inoculation. Leaf and petiole tissues were collected from one‐half to three‐quarters expanded leaves, and were fixed and dehydrated as described previously (Rojas et al., 2001). Parafilm‐embedded tissues were sectioned and rehydrated prior to incubation with TYLCV CP antisera (Rojas et al., 2001) or preimmune antisera. Detection of CP was carried out on fixed tissues, as described previously (Rojas et al., 2001). Briefly, the CP and preimmune antisera were diluted 1 : 500 and were followed by goat anti‐rabbit antibodies (1 : 2000 dilution) conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (AP). AP activity was visualized with nitroblue tetrazolium and bromo‐chloro‐indolyl phosphate, and imaged by phase contrast light microscopy.

Southern and Western blot analyses

Southern and Western blot analyses were performed with total genomic DNA or total protein extracts, respectively, from equivalent‐aged leaves collected from D. stramonium, N. benthamiana, N. glutinosa and tomato plants infected with TYLCMLV or TYLCMLV and CLCuGB, 2–3 weeks after agroinoculation. Total genomic DNA was extracted from 0.1 g of leaf tissue, and 5 µg of DNA was separated in 1.2% TAE [Tris‐acetate–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)] agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA), as described previously (Hou et al., 1998). Blots were probed with pTYML‐1.8 labelled with α32P‐deoxycytidine triphosphate (α32P‐dCTP) by nick translation, washed and exposed to X‐ray film. Hybridization signals were quantified with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Total proteins were extracted from leaf tissues as described previously (Hou et al., 2000). Fifteen microlitres of total proteins were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulphate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE), and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were probed with TYLCV CP polyclonal antisera diluted 1 : 500 in TBST (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 0.25 m NaCl, 0.5% Tween‐20). The CP (primary) antibody was detected with goat anti‐rabbit antibody conjugate (1 : 2000 dilution), followed by AP colour reaction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Integrated Pest Management Collaborative Research Support Program (IPM CRSP) and Agricultural Biotechnology Support Project (ABSP) II. These projects were made possible by the United States Agency for International Development and the generous support of the American people though USAID Cooperative Agreements No. EPPA‐00‐04‐00016‐00 (IPM‐CPSP) and No. GDG‐0‐00‐02‐00017‐00 (ABSPII). We thank Dr Charles Hagen for assistance in cloning CLCuGB, Ms Nasrin Hakimi for excellent technical assistance and Dr Yanchen Zhou for assistance in designing the TYLCMLV‐specific primer.

REFERENCES

- Abhary, M. , Patil, B. and Fauquet, C. (2007) Molecular biodiversity, taxonomy, and nomenclature of tomato yellow leaf curl‐like viruses In: Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Disease: Management, Molecular Biology, Breeding for Resistance (Czosnek H. ed.), pp. 85–118. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Alberter, B. , Ali Rezaian, M. and Jeske, H. (2005) Replicative intermediates of Tomato leaf curl virus and its satellite DNAs. Virology, 331, 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argüello‐Astorga, G.R. and Ruiz‐Medrano, R. (2001) An iteron‐related domain is associated to Motif 1 in the replication proteins of geminiviruses: identification of potential interacting amino acid‐base pairs by a comparative approach. Arch. Virol. 146, 1465–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisaro, D.M. (2006) Silencing suppression by geminivirus proteins. Virology, 344, 158–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon, R.W. and Stanley, J. (2006) Subviral agents associated with plant single‐stranded DNA viruses. Virology, 344, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon, R.W. , Mansoor, S. , Bedford, I.D. , Pinner, M.S. , Saunders, K. , Stanley, J. , Zafar, Y. , Malik, K.A. and Markham, P.G. (2001) Identification of DNA components required for induction of cotton leaf curl disease. Virology, 285, 234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon, R.W. , Bull, S.E. , Mansoor, S. , Amin, I. and Markham, P.G. (2002) Universal primers for the PCR‐mediated amplification of DNA beta: a molecule associated with some monopartite begomoviruses. Mol. Biotech. 20, 315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.K. and Idris, A.M. (2006) Introduction of the exotic monopartite Tomato yellow leaf curl virus into West Coast Mexico. Plant Dis. 90, 1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, J.C. and Ambros, V. (2003) Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science, 301, 336–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. , Tao, X. , Xie, Y. , Fauquet, C.M. and Zhou, X. (2004) A DNA β associated with Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus is required for symptom induction. J. Virol. 78, 13966–13974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. , Li, G. , Wang, D. , Hu, D. and Zhou, X. (2005a) A begomovirus DNAβ‐encoded protein binds DNA, functions as a suppressor of RNA silencing, and targets the cell nucleus. J. Virol. 79, 10764–10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. , Li, Y. , Hu, D. and Zhou, X. (2005b) Expression of a begomoviral DNAβ gene in transgenic Nicotiana plants induced abnormal cell division. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 6, 83–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, S. and Holmes, E.C. (2008) Phylogenetic evidence for rapid rates of molecular evolution in the single‐stranded DNA begomovirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J. Virol. 82, 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquet, C.M. , Sawyer, S. , Idris, A.M. and Brown, J.K. (2005) Sequence analysis and classification of apparent recombinant begomoviruses infecting tomato in the Nile and Mediterranean Basins. Phytopathology, 95, 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquet, C. , Briddon, R. , Brown, J. , Moriones, E. , Stanley, J. , Zerbini, M. and Zhou, X. (2008) Geminivirus strain demarcation and nomenclature. Arch. Virol. 153, 783–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Andrés, S. , Accotto, G.P. , Navas‐Castillo, J. and Moriones, E. (2006) Founder effect, plant host, and recombination shape the emergent population of begomoviruses that cause the tomato yellow leaf curl disease in the Mediterranean basin. Virology, 359, 302–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge, L. , Zhang, J. , Zhou, X. and Li, H. (2007) Genetic structure and population variability of Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus. J. Virol. 81, 5902–5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleave, A.P. (1992) A versatile binary vector system with a T‐DNA organisational structure conducive to efficient integration of cloned DNA into the plant genome. Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 1203–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal, P. , Pravin Kumar, P. , Sinilal, B. , Jose, J. , Kasin Yadunandam, A. and Usha, R. (2007) Differential roles of C4 and βC1 in mediating suppression of post‐transcriptional gene silencing: evidence for transactivation by the C2 of Bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus, a monopartite begomovirus. Virus Res. 123, 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W. , Jiang, T. , Zhang, X. , Li, G. and Zhou, X. (2008) Molecular variation of satellite DNAβ molecules associated with Malvastrum yellow vein virus and their role in pathogenicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1909–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, B.D. (1985) Advances in geminivirus research. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 23, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.‐M. , Paplomatas, E.J. and Gilbertson, R.L. (1998) Host adaptation and replication properties of two bipartite geminiviruses and their pseudorecombinants. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 11, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.‐M. , Sanders, R. , Ursin, V.M. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2000) Transgenic plants expressing geminivirus movement proteins: abnormal phenotypes and delayed infection by Tomato mottle virus in transgenic tomatoes expressing the Bean dwarf mosaic virus BV1 or BC1 proteins. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 13, 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idris, A.M. and Brown, J.K. (2005) Evidence for interspecific‐recombination for three monopartite begomoviral genomes associated with the tomato leaf curl disease from central Sudan. Arch. Virol. 150, 1003–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose, J. and Usha, R. (2003) Bhendi yellow vein mosaic disease in India is caused by association of a DNA β satellite with a begomovirus. Virology, 305, 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon, T. , Rojas, M.R. , Abdourhamane, I.K. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2009) The roles and interactions of begomoviruses and satellite DNAs associated with okra leaf curl disease in Mali, West Africa. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 1001–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon, T. , Hidayat, S.H. , Hase, S. , Takahashi, H. and Ikegami, M. (2006) The natural occurrence of two distinct begomoviruses associated with DNAβ and a recombinant DNA in a tomato plant from Indonesia. Phytopathology, 96, 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon, T. , Sharma, P. and Ikegami, M. (2007) Suppressor of RNA silencing encoded by the monopartite tomato leaf curl Java begomovirus. Arch. Virol. 152, 1273–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham, J.R. , Saunders, K. , Pinner, M.S. and Stanley, J. (1997) Induction of plant cell division by beet curly top virus gene C4. Plant J. 11, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre, P. , Martin, D.P. , Hoareau, M. , Naze, F. , Delatte, H. , Thierry, M. , Varsani, A. , Becker, N. , Reynaud, B. and Lett, J.M. (2007) Begomovirus ‘melting pot’ in the south‐west Indian Ocean islands: molecular diversity and evolution through recombination. J. Gen. Virol. 88, 3458–3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Xie, Y. and Zhou, X. (2005) Tobacco curly shoot virus DNAβ is not necessary for infection but intensifies symptoms in a host‐dependent manner. Phytopathology, 95, 902–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, S. , Briddon, R.W. , Bull, S.E. , Bedford, I.D. , Bashir, A. , Hussain, M. , Saeed, M. , Zafar, Y. , Malik, K.A. , Fauquet, C. and Markham, P.G. (2003a) Cotton leaf curl disease is associated with multiple monopartite begomoviruses supported by single DNA β. Arch. Virol. 148, 1969–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, S. , Briddon, R.W. , Zafar, Y. and Stanley, J. (2003b) Geminivirus disease complexes: an emerging threat. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, S. , Zafar, Y. and Briddon, R.W. (2006) Geminivirus disease complexes: the threat is spreading. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.P. , Williamson, C. and Posada, D. (2005) RDP2: recombination detection and analysis from sequence alignments. Bioinformatics, 21, 260–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monci, F. , Sánchez‐Campos, S. , Navas‐Castillo, J. and Moriones, E. (2002) A natural recombinant between the geminiviruses Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus exhibits a novel pathogenic phenotype and is becoming prevalent in Spanish populations. Virology, 303, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morilla, G. , Castillo, A.G. , Preiss, W. , Jeske, H. and Bejarano, E.R. (2006) A versatile transreplication‐based system to identify cellular proteins involved in geminivirus replication. J. Virol. 80, 3624–3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriones, E. , Garcia‐Andres, S. and Navas‐Castillo, J. (2007) Recombination in the TYLCV complex: a mechanism to increase genetic diversity. Implications for plant resistance development In: Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Disease: Management, Molecular Biology, Breeding for Resistance (Czosnek H., ed.), pp. 119–138. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Navot, N. , Pichersky, E. , Zeidan, M. , Zamir, D. and Czosnek, H. (1991) Tomato yellow leaf curl virus: A whitefly‐transmitted geminivirus with a single genomic component. Virology, 185, 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, T. , Sharma, P. and Ikegami, M. (2008) The begomoviruses Honeysuckle yellow vein mosaic virus and Tobacco leaf curl Japan virus with DNAβ satellites cause yellow dwarf disease of tomato. Virus Res. 137, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paplomatas, E.J. , Patel, V.P. , Hou, Y.‐M. , Noueiry, A.O. and Gilbertson, R.L. (1994) Molecular characterization of a new sap‐transmissible bipartite genome geminivirus infecting tomatoes in Mexico. Phytopathology, 84, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.P. , Rojas, M.R. , Paplomatas, E.J. and Gilbertson, R.L. (1993) Cloning biologically active geminivirus DNA using PCR and overlapping primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 1325–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polston, J.E. , MacGovern, R.J. and Brown, L.G. (1999) Introduction of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in Florida and implications for the spread of this and other geminiviruses of tomato. Plant Dis. 83, 984–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, J. , Amin, I. , Mansoor, S. , Iqbal, M.J. and Briddon, R.W. (2007) Contribution of the satellite encoded gene βC1 to cotton leaf curl disease symptoms. Virus Res. 128, 135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, M.S. , Selth, L.A. , Koltunow, A.M.G. , Randles, J.W. and Rezaian, M.A. (2006) Single‐stranded DNA of Tomato leaf curl virus accumulates in the cytoplasm of phloem cells. Virology, 348, 120–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.R. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2008) Emerging plant viruses: a diversity of mechanisms and opportunities In: Plant Virus Evolution (Roossink M.J., ed.), pp. 27–51. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.R. , Gilbertson, L.R. , Russell, D.R. and Maxwell, D.P. (1993) Use of degenerate primers in the polymerase chain reaction to detect whitefly‐transmitted geminiviruses. Plant Dis. 77, 340–347. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.R. , Jiang, H. , Salati, R. , Xoconostle‐Cázares, B. , Sudarshana, M.R. , Lucas, W.J. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2001) Functional analysis of proteins involved in movement of the monopartite begomovirus, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus . Virology, 291, 110–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.R. , Hagen, C. , Lucas, W.J. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2005) Exploiting chinks in the plant's armor: evolution and emergence of geminiviruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43, 361–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M.R. , Kon, T. , Natwick, E.T. , Polston, J.E. , Akad, F. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2007) First report of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus associated with tomato yellow leaf curl disease in California, USA. Plant Dis. 91, 1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybicki, E.P. (1994) A phylogenetic and evolutionary justification for three genera of Geminiviridae. Arch. Virol. 139, 49–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M. , Zafar, Y. , Randles, J.W. and Rezaian, M.A. (2007) A monopartite begomovirus‐associated DNA beta satellite substitutes for the DNA B of a bipartite begomovirus to permit systemic infection. J. Gen. Virol. 88, 2881–2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salati, R. , Nahkla, M.K. , Rojas, M.R. , Guzman, P. , Jaquez, J. , Maxwell, D.P. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2002) Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in the Dominican Republic: characterization of an infectious clone, virus monitoring in whiteflies, and identification of reservoir hosts. Phytopathology, 92, 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, K. , Bedford, I.D. , Briddon, R.W. , Markham, P.G. , Wong, S.M. and Stanley, J. (2000) A unique virus complex causes Ageratum yellow vein disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6890–6895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal, S.E. , Jeger, M.J. and Van den Bosch, F. (2006) Begomovirus evolution and disease management. Adv. Virus Res. 67, 297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.‐S. , Rojas, M.R. , Lee, J.‐Y. , Lee, S.‐W. , Jeon, J.‐S. , Ronald, P. , Lucas, W.J. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2006) A viral resistance gene from common bean functions across plant families and is up‐regulated in a non‐virus‐specific manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 11856–11861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J. , Bisaro, D.M. , Briddon, R.W. , Brown, J.K. , Fauquet, C.M. , Harrison, B.D. , Rybicki, E.P. and Stenger, D.C. (2005) Geminiviridae In: Virus Taxonomy. VIIIth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (Fauquet C.M., Mayo M.A., Maniloff J., Desselberger U. and Ball L.A., eds), pp. 301–326. London: Elsevier/Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. , Dudley, J. , Nei, M. and Kumar, S. (2007) mega4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanitharani, R. , Chellappan, P. and Fauquet, C.M. (2005) Geminiviruses and RNA silencing. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma, A. and Malathi, V.G. (2003) Emerging geminivirus problems: a serious threat to crop production. Ann. Appl. Biol. 142, 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Vaucheret, H. , Vazquez, F. , Crete, P. and Bartel, D.P. (2004) The action of ARGONAUTE1 in the miRNA pathway and its regulation by the miRNA pathway are crucial for plant development. Genes Dev. 18, 1187–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. , Xie, Y. , Tao, X. , Zhang, Z. , Li, Z. and Fauquet, C.M. (2003) Characterization of DNA associated with begomoviruses in China and evidence for co‐evolution with their cognate viral DNA‐A. J. Gen. Virol. 84, 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.C. , Noussourou, M. , Kon, T. , Rojas, M. , Jiang, H. , Chen, L.F. , Gamby, K. , Foster, R. and Gilbertson, R.L. (2008). Evidence of local evolution of tomato‐infecting begomovirus species in West Africa: characterization of tomato leaf curl Mali virus and tomato yellow leaf crumple virus from Mali. Arch. Virol. 153, 693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]