SUMMARY

The interaction between tomato and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici has become a model system for the study of the molecular basis of disease resistance and susceptibility. Gene‐for‐gene interactions in this system have provided the basis for the development of tomato cultivars resistant to Fusarium wilt disease. Over the last 6 years, new insights into the molecular basis of these gene‐for‐gene interactions have been obtained. Highlights are the identification of three avirulence genes in F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and the development of a molecular switch model for I‐2, a nucleotide‐binding and leucine‐rich repeat‐type resistance protein which mediates the recognition of the Avr2 protein. We summarize these findings here and present possible scenarios for the ongoing molecular arms race between tomato and F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in both nature and agriculture.

INTRODUCTION

Microbes have been interacting with plants for hundreds of millions of years. Plant–microbe interactions have taken various forms, such as commensalism (microbes living off compounds naturally released by plants), endophytism (microbes living inside plants without affecting the host's fitness), symbiosis (the interacting organisms together are fitter than the separate organisms) and parasitism (reduced fitness of the plant for the benefit of the microbe). In the case of parasitism, the plant and microorganism have competing interests, which leads to an evolutionary ‘arms race’ in which the interaction constantly selects for genetic changes in both pathogen and plant populations. Genetic changes that enhance fitness, e.g. the ability to avoid host detection or regain pathogen recognition ability, will be maintained in the population (Maor & Shirasu, 2005, Stahl & Bishop, 2000).

Over time, these interactions leave ‘footprints’ in the genome in the shape of highly variable coding sequences, reflecting the rapid evolution of genes that encode proteins directly involved in this interaction. Examples of such rapidly evolving genes are those that encode effectors (small secreted proteins) from the pathogen and resistance (R) proteins from the host. R proteins are specialized proteins that mediate the recognition of effectors and induce disease resistance responses (Stukenbrock & McDonald, 2009). To gain a deeper understanding into the long‐term co‐evolution of plants and their microbial pathogens, and the implications for the short‐term evolution in agricultural settings, it is necessary to identify the co‐evolving proteins in each partner. We have been pursuing this for the interaction between tomato and the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum. In this review, we present our current understanding of the molecular components that constitute the interface between these two sparring partners.

RESISTANCE GENES AGAINST FUSARIUM OXYSPORUM F. SP. LYCOPERSICI (FOL) IN TOMATO

In some vegetable crops, monogenic resistance has been found against host‐specific pathogenic forms (‘formae speciales’) of F. oxysporum (Michielse & Rep, 2009). In tomato, R genes against the wilt‐inducing Fol are called I (for immunity) genes. Of these genes, I, I‐2 and I‐3 have been introgressed into commercial cultivars (Huang & Lindhout, 1997). Fol divides into races on the basis of the ability of individual strains to overcome specific I genes. This implies the presence of avirulence genes in the fungus that are recognized by products of the corresponding I genes (Keen, 1990). We have confirmed the existence of these avirulence genes in Fol, and have shown that the breaking of I gene‐mediated resistance is indeed caused by a loss of, or mutations in, these genes (see below).

I gene‐mediated recognition of Fol, a xylem‐colonizing fungus, induces a defence response in xylem contact cells (parenchymal cells adjacent to vessel elements). Instead of a classical hypersensitive response (HR) (i.e. cell death), this response mainly involves callose deposition, the accumulation of phenolics and the formation of tyloses (outgrowths of xylem contact cells) and gels in the infected vessels (Beckman, 2000). Of the I genes in tomato, to date only I‐2 has been cloned (Simons et al., 1998). Promoter–reporter studies have shown that I‐2 is mainly expressed in the vascular tissues of roots, stems and leaves (Mes et al., 2000). Systemic expression of the matching Avr2 protein in tomato plants using a virus‐based expression system has revealed that endogenous I‐2 can be activated in leaves, although leaves are normally not invaded by the fungus in resistant (incompatible) interactions (Houterman et al., 2009). I‐2 encodes a nucleotide‐binding and leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) protein, a class of proteins commonly involved in the recognition of effectors from bacteria, viruses, fungi, oomycetes and even nematodes (van Ooijen et al., 2007). The name NB‐LRR is derived from the conserved central NB site and the adjacent LRRs. Most NB‐LRR proteins carry an N‐terminal domain that folds either as a coiled‐coil (CC) or Toll/interleukin‐1 receptor (TIR) domain (van Ooijen et al., 2007); I‐2 belongs to the CC type.

Mutational analysis of the NB domain of I‐2 has revealed that its activation state is apparently controlled by the nucleotide bound by the NB domain: ADP in the resting state and ATP in the activated state (Tameling et al., 2006). The switch between these two states can be reset by the hydrolysis of bound ATP, as these NB‐LRR proteins exhibit intrinsic ATPase activity (Tameling et al., 2002). Similar mechanisms of nucleotide‐dependent conformational changes to regulate cellular responses have also been proposed for other members of the signal transduction ATPases with numerous domains (STAND) family (Leipe et al., 2004; Takken & Tameling, 2009). In addition to plant NB‐LRR proteins, the STAND family includes the human nucleotide‐binding and oligomerization domain (NOD) and apoptotic protease activating factor‐1 (APAF‐1) proteins, which are involved in innate immunity and apoptosis, respectively.

As host defence initiated by NB‐LRRs often employs the ‘scorched earth’ policy, destroying anything that might be useful to the enemy, the activity of these proteins must be tightly regulated. Studies with the solanaceous NB‐LRR proteins Rx, Mi‐1 and Bs2 have revealed that their activity is probably regulated by intramolecular interactions between the different domains (Leister et al., 2005; Moffett et al., 2002; van Ooijen et al., 2008; Rairdan & Moffett; 2006). In the absence of a pathogen, the LRR binds the NB domain, resulting in auto‐inhibition, which is relieved upon pathogen perception. Pathogen recognition seems to reside mainly in the C‐terminal half of the LRR domain, and translates into a conformational change of the protein, allowing it to bind ATP and subsequently activate defence reactions (Lukasik & Takken, 2009).

How activated NB‐LRR proteins trigger defences is currently unclear. One hypothesis is that, similar to their mammalian counterparts (Danot et al., 2009, Riedl & Salvesen, 2007), they form an activation scaffold for signalling components. However, no obvious signalling partners for plant NB‐LRR proteins have yet been identified, and most interactors identified so far are either (co)chaperones or proteins implicated in pathogen perception (Lukasik & Takken, 2009). An alternative hypothesis is that NB‐LRRs may be involved directly in the transcriptional regulation of defence genes. This scenario would resemble that of the class II transactivator (CIITA), a human STAND protein involved in the activation of the major histocompatibility complex (Chen et al., 2009). Support for a nuclear function is the requirement of at least some plant NB‐LRR proteins to be in the nucleus to allow defence activation (Shen et al., 2007, Tameling & Takken, 2008). The subcellular localization of I‐2 is currently unknown, and its determination is hampered by the lack of sufficiently sensitive antibodies, as well as the inability to create functional tagged versions.

EFFECTORS AND AVIRULENCE GENES OF FOL

During the colonization of xylem vessels of tomato, Fol secretes enzymes as well as small proteins (<25 kDa) whose sequences do not immediately suggest a function (Houterman et al., 2007). The small proteins are putative effector proteins, i.e. proteins that promote host colonization, for instance by the suppression of basal resistance mechanisms (Chisholm et al., 2006; Jones & Dangl, 2006). The repertoire of effector proteins, to a large extent, determines the virulence of a pathogen towards a particular host (Speth et al., 2007).

In Fol, 11 (candidate) effector proteins have been identified thus far, and these are termed ‘Secreted in xylem’ (Six) proteins (Houterman et al., 2007; Lievens et al., 2009; M. Rep, unpublished results). Three of these are targeted by the introgressed I genes of tomato (Table 1): Avr1 (Six4) is recognized by I and the non‐allelic I‐1 gene (Houterman et al., 2008); Avr2 (Six3) is recognized by I‐2 (Houterman et al., 2009); and Avr3 (Six1) is recognized by I‐3 (Rep et al., 2004). At present, Avr2 and Avr3 (Houterman et al., 2009; Rep, 2005), as well as Six6 (M. Rep, unpublished results), are genuine effectors, as they have been found to contribute to the general virulence of Fol (i.e. towards tomato plants without I genes). This is evidenced by reduced virulence of the respective gene knock‐out strains, an effect which is usually more clearly observed upon infection of older plants rather than seedlings.

Table 1.

Resistance (R) genes in tomato and corresponding effectors in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol).

| R gene* | Chromosome† | Introgressed from: | Effector recognized | Alternative name of effector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 11 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | Avr1 | Six4 |

| I‐1 | 7 | Solanum pennellii | Avr1 | Six4 |

| I‐2 | 11 | Solanum pimpinellifolium | Avr2 | Six3 |

| I‐3 | 7 | Solanum pennellii | Avr3 | Six1 |

Additional loci in S. pennellii conferring resistance to Fol have been mapped by Sela‐Buurlage et al. (2001).

Mapping of I genes is summarized in Huang & Lindhout (1997).

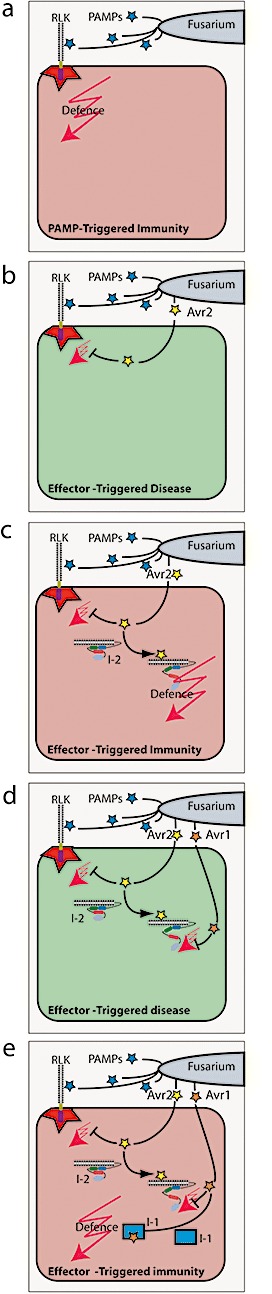

Avr1 is not required for general virulence. Instead, it specifically suppresses the ability of both I‐2 and I‐3 to confer resistance against Fol race 1 strains, despite the secretion of Avr2 and Avr3 by these strains (Houterman et al., 2008). This makes Avr1 the first cloned fungal effector that suppresses R gene‐mediated disease resistance in plants, a phenomenon which may be more widespread (Jones, 1988). Our current working model, detailing the interactions between effectors and I proteins in the tomato–Fol pathosystem, is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Working model depicting the molecular arms race between tomato and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol). (a) Non‐pathogenic F. oxysporum strains trigger the induction of basal defence preventing disease. This pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP)‐triggered immunity (PTI) is probably conferred by receptor‐like kinases (RLKs). (b) Effectors, such as Avr2, suppress the PTI response, allowing pathogenic Fol strains to cause disease. (c) Perception of Avr2 by the nucleotide‐binding and leucine‐rich repeat (NB‐LRR) protein I‐2 triggers a conformational change, allowing it to activate host defence. (d) Avr1‐carrying Fol strains frustrate I‐2‐mediated defence, resulting in disease development. (e) Avr1 is recognized by I or I‐1, resulting in the activation of host defences.

It is currently unclear how Fol effectors are perceived by I proteins. One possibility is the mechanistically simple receptor–ligand model in which the R protein is activated by a direct interaction with the effector (Ellis et al., 2007). In a more complex model, an R protein associates with a host protein whose activity or structure is manipulated by the effector. This modification is perceived by the R protein, which thereby detects the effector indirectly. The host protein involved can either present a genuine virulence target of the effector (the ‘guard’ model) or a target mimic (the ‘decoy’ model) (van der Hoorn & Kamoun, 2008).

For the NB‐LRR protein I‐2, it is unknown which mechanism applies. Avr2 is secreted in the xylem sap by the fungus, but is perceived inside the host cell (Houterman et al., 2009), making an extracellular target that is guarded by I‐2 unlikely. Single amino acid changes in Avr2 (V41 → M, R45 → H or R46 → P) abolish I‐2‐mediated recognition, but do not affect its virulence function (Houterman et al., 2009). This suggests that interaction with the putative virulence target is unaffected by these mutations, ruling out the possibility that I‐2 solely detects changes in a virulence target. This leaves the options open for: (i) a direct interaction, (ii) the decoy model or (iii) recognition of an Avr2–target complex.

Yeast two‐hybrid and pull‐down experiments have so far failed to reveal a direct interaction between Avr2 and I‐2 (F. Takken and M. Rep, unpublished results). To test the alternative options, Avr2 and I‐2 have been used as bait to identify interacting proteins. Until now, these screens have yielded three proteins that interact with the LRR domain of I‐2. All are (co)chaperones: heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) (De la Fuente van Bentem et al., 2005) and Hsp17 (F. Takken, unpublished results). These are probably involved in the folding or stabilization of I‐2 rather than in Avr2 perception. Three other proteins have been identified which, in a yeast two‐hybrid assay, interact with the N‐terminal part of I‐2 (F. Takken, unpublished results). Further investigation of these proteins, together with experiments aimed at the identification of Avr2‐interacting plant proteins, may shed light on the Avr2 recognition mechanism and reveal the virulence target(s) of Avr2.

EVOLUTION OF THE FOL–TOMATO PATHOSYSTEM IN NATURE AND AGRICULTURE

The current gene‐for‐gene interactions between Fol and tomato fit an extended zig–zag model of evolution (Houterman et al., 2009; Jones & Dangl, 2006) (Fig. 1). In short, non‐pathogenic strains of F. oxysporum colonize roots, but are generally restricted to the root surface by the basal defence system of the plant (Fig. 1a). Recognition of these non‐pathogenic strains is probably mediated by extracellular receptor‐like kinases (RLKs) which detect the presence of pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and trigger PAMP‐triggered immunity (Boller & Felix, 2009). Host‐specific virulence evolved in Fol through the acquisition of a combination of effectors, enzymes and, perhaps, secondary metabolites. At least Avr2, Avr3 and Six6 are involved in the promotion of disease development in tomato (‘zig’) (Fig. 1b; for simplicity, only Avr2 is shown). In tomato, I‐2 and I‐3 evolved to recognize virulence factors Avr2 and Avr3, respectively (‘zag’) (Fig. 1c depicts only the I‐2–Avr2 combination). To evade recognition, the fungus employed two escape strategies: (i) Avr2 variants evolved which contain single point mutations; these mutations do not affect virulence but prevent recognition by I‐2; (ii) Avr1 evolved to suppress both I‐2 and I‐3 function via an unknown mechanism (‘zig’) (Fig. 1d). In tomato, I (and, perhaps independently, I‐1) evolved to recognize Avr1, providing protection again (‘zag’) (Fig. 1e).

The scenario described above suggests the co‐evolution of tomato and Fol over millions of years. However, very few sequence polymorphisms have been found in SIX genes from Fol strains isolated from diseased tomato plants worldwide (Table 2 and below). This homogeneity indicates a single, recent origin of the tomato wilt form of F. oxysporum in agricultural settings. This appears to be is in contradiction with the polyphyletic origins of the four clonal lines (vegetative compatibility groups) of forma specialis lycopersici within the F. oxysporum complex, as defined by gene sequences other than those of SIX genes (Cai et al., 2003). This apparent contradiction can now be explained by the observation that the SIX genes lie on a single chromosome that is transferable between clonal lines of F. oxysporum (van der Does et al., 2008) (M. Rep, unpublished results).

Table 2.

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Fol) races and avirulence genotypes.

| Race | Genotype | Resisted by | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AVR1 | AVR2 | AVR3 | I, I‐1 (I‐2 and I‐3 suppressed) |

| 2 | — | AVR2 | AVR3 | I‐2, I‐3 |

| 3 | — | avr2 * | AVR3 | I‐3 |

Point mutation prevents recognition by I‐2, but does not affect virulence function.

The origin of this ‘effector chromosome’ is uncertain. Homologues of some of the SIX genes (SIX6 and SIX7) have also been found in a few other formae speciales (Lievens et al., 2009), and a SIX2 homologue is present in the sister species F. verticillioides (M. Rep, unpublished observations). Whole genome comparisons between F. graminearum, F. verticillioides and Fol, and analysis of gene sequences on the Fol effector chromosome, suggest that this chromosome was not vertically inherited from the last common ancestor of F. verticillioides and F. oxysporum, but has been acquired horizontally (L.‐J. Ma, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA). It may be that this acquisition is old and that the tomato‐specific effector chromosome has evolved in close association with tomato over millions of years. The fully adapted chromosome might then have been recently distributed over the world, together with tomato, which would explain its low sequence variation. The chromosome would then most probably have ‘travelled’ in the most diverse and global clonal line of Fol, VCG0030, occasionally ‘infecting’ another clonal line (VCG0031, VCG0033, VCG0035), which may have been better adapted to local soil, climate or tomato culture conditions (Cai et al., 2003; van der Does et al., 2008).

Only four sequence polymorphisms have been found in the known effector genes of the Fol strains isolated from cultivated tomato plants. The one AVR3 DNA polymorphism found (G490 → A) leads to an amino acid change (E164 → K) which confers a higher virulence to Fol than the E164 variant (Rep et al., 2005), and may have emerged early in VCG0030 through selection for increased virulence towards cultivated tomato (van der Does et al., 2008). The three remaining polymorphisms all reside in AVR2 (G121 → A, G134 → A, G137 → C), each leading to an amino acid change that prevents recognition by I‐2 (as described above). These mutations have probably been selected in tomato fields after deployment of I‐2.

On the basis of the data described above, we have reconstructed the emergence of Fol races in agriculture as follows. The historically ‘oldest’ race 1 contains all three AVR genes (Table 2), and the only sequence variation found in effector genes among current race 1 strains is the polymorphism in AVR3. After introduction of the I gene from Solanum pimpinellifolium in the 1940s (Bohn & Tucker, 1939), strains were retrieved from wilted tomato plants that (we now know) did not have AVR1 (Alexander & Tucker, 1945). The swiftness with which these race 2 strains emerged worldwide in two different clonal lines (VCG0030 and VCG0031) may be a result of either their pre‐existence in areas in which tomato was cultivated, or a high frequency of spontaneous AVR1 loss combined with strong selection. Subsequent introduction, in the 1960s, of the I‐2 gene (also from S. pimpinellifolium) to control race 2 proved to be more stable. The time period of approximately 20 years before the emergence of race 3 in the early 1980s (Volin & Jones, 1982), which we now know is the result of one of three different single point mutations in AVR2 (see above), suggests that mutations in AVR2 were selected after the introduction of I‐2‐containing tomato cultivars. That these mutations were not pre‐existent is supported by their absence in race 1 strains (Houterman et al., 2009).

Finally, I‐3 was introduced from Solanum pennellii in the late 1980s (MacGrath & Maltby, 1989). Its use as a single R gene against Fol is probably not so effective, because race 1 is virulent on such a tomato line through the production of the I‐2/I‐3 suppressor Avr1 (Houterman et al., 2008). Combined use of I and I‐3 should provide relatively durable protection against all races of Fol, with the caveat that single point mutations in AVR3 in a race 3 background may lead to the breaking of I‐3 (i.e. emergence of race 4). Complete loss of AVR3 is no option for Fol as that leads to reduced virulence (Rep et al., 2005).

If Avr1 and Avr3 are recognized indirectly (i.e. according to the guard or decoy model), theoretically, it is less likely that I and I‐3‐mediated resistance can be overcome by mutations in the effectors without a concomitant fitness penalty (van der Hoorn et al., 2002). As the likelihood of such resistance‐breaking mutations in Avr1 or Avr3 affects the durability of I and I‐3‐mediated disease resistance in tomato, it will be important to uncover the mode of recognition of these effectors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research described is an overview of the work performed in the past decade within the plant pathology group at the University of Amsterdam, together with collaborators whose names appear as co‐authors on the papers cited in the literature. This review was developed from a presentation given at the British Society for Plant Pathology's 2009 presidential meeting. We thank Harrold van den Burg, Ben Cornelissen and Lotje van der Does for improving the manuscript through their critical feedback. The work in the Takken/Rep/Cornelissen laboratory was and is supported in part by grants from the Dutch Genomics Initiative (CBSG2012), the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, the EU Framework 6 Programme Bioexploit, Dutch Research Organization STW and the Utopa Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Alexander, L.J. and Tucker, C.M. (1945) Physiological specialization in the tomato wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici . J. Agric. Res. 70, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Beckman, C.H. (2000) Phenolic‐storing cells: keys to programmed cell death and periderm formation in wilt disease resistance and in general defence responses in plants? Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, G.W. and Tucker, C.M. (1939) Immunity to Fusarium wilt of tomato. Science, 89, 603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller, T. and Felix, G. (2009) A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe‐associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern‐recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 379–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G. , Gale, L.R. , Schneider, R.W. , Kistler, H.C. , Davis, R.M. , Elias, K.S. and Miyao, E.M. (2003) Origin of Race 3 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp lycopersici at a single site in California. Phytopathology, 93, 1014–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. , Shaw, M.H. , Kim, Y.G. and Nunez, G. (2009) NOD‐like receptors: role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 4, 365–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, S.T. , Coaker, G. , Day, B. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2006) Host–microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell, 124, 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danot, O. , Marquenet, E. , Vidal‐Ingigliardi, D. and Richet, E. (2009) Wheel of life, wheel of death: a mechanistic insight into signaling by STAND proteins. Structure, 17, 172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente van Bentem, S. , Vossen, J.H. , De Vries, K. , Van Wees, S.C. , Tameling, W.I.L. , Dekker, H. , De Koster, C.G. , Haring, M.A. , Takken, F.L.W. and Cornelissen, B.J.C. (2005) Heat shock protein 90 and its co‐chaperone protein phosphatase 5 interact with distinct regions of the tomato I‐2 disease resistance protein. Plant J. 43, 284–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, J.G. , Dodds, P.N. and Lawrence, G.J. (2007) Flax rust resistance gene specificity is based on direct resistance–avirulence protein interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45, 289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houterman, P.M. , Cornelissen, B.J. and Rep, M. (2008) Suppression of plant resistance gene‐based immunity by a fungal effector. PLoS. Pathog. 4, e1000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houterman, P.M. , Ma, L. , Van Ooijen, G. , De Vroomen, M.J. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. , Takken, F.L.W. and Rep, M. (2009) The effector protein Avr2 of the xylem colonizing fungus Fusarium oxysporum activates the tomato resistance protein I‐2 intracellularly. Plant J. 58, 970–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houterman, P.M. , Speijer, D. , Dekker, H.L. , De Koster, C.G. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. and Rep, M. (2007) The mixed xylem sap proteome of Fusarium oxysporum‐infected tomato plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C. and Lindhout, P. (1997) Screening for resistance in wild Lycopersicon species to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici race 1 and race 2. Euphytica, 93, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.A. (1988) Genetic properties of inhibitor genes in flax rust that alter avirulence to virulence on flax. Phytopathology, 78, 342–344. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen, N.T. (1990) Gene‐for‐gene complementarity in plant–pathogen interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 24, 447–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipe, D.D. , Koonin, E.V. and Aravind, L. (2004) STAND, a class of P‐loop NTPases including animal and plant regulators of programmed cell death: multiple, complex domain architectures, unusual phyletic patterns, and evolution by horizontal gene transfer. J. Mol. Biol. 343, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister, R.T. , Dahlbeck, D. , Day, B. , Li, Y. , Chesnokova, O. and Staskawicz, B.J. (2005) Molecular genetic evidence for the role of SGT1 in the intramolecular complementation of Bs2 protein activity in Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant Cell, 17, 1268–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens, B. , Houterman, P.M. and Rep, M. (2009) Effector gene screening allows unambiguous identification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici races and discrimination from other formae speciales . FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 300, 201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasik, E. and Takken, F.L.W. (2009) STANDing strong, resistance protein instigators of plant defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGrath, D.J. and Maltby, J.E. (1989) Fusarium wilt race 3 resistance in tomato. Acta. Hortic. 247, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Maor, R. and Shirasu, K. (2005) The arms race continues: battle strategies between plants and fungal pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mes, J.J. , Van Doorn, A.A. , Wijbrandi, J. , Simons, G. , Cornelissen, B.J. and Haring, M.A. (2000) Expression of the Fusarium resistance gene I‐2 colocalizes with the site of fungal containment. Plant J. 23, 183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielse, C.B. and Rep, M. (2009) Pathogen profile update: Fusarium oxysporum . Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 311–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, P. , Farnham, G. , Peart, J. and Baulcombe, D.C. (2002) Interaction between domains of a plant NBS‐LRR protein in disease resistance‐related cell death. EMBO J. 21, 4511–4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rairdan, G.J. and Moffett, P. (2006) Distinct domains in the ARC region of the potato resistance protein Rx mediate LRR binding and inhibition of activation. Plant Cell, 18, 2082–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rep, M. (2005) Small proteins of plant‐pathogenic fungi secreted during host colonization. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rep, M. , Meijer, M. , Houterman, P.M. , Van Der Does, H.C. and Cornelissen, B.J.C. (2005) Fusarium oxysporum evades I‐3‐mediated resistance without altering the matching avirulence gene. Mol. Plant–Microbe. Interact. 18, 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rep, M. , Van Der Does, H.C. , Meijer, M. , Van Wijk, R. , Houterman, P.M. , Dekker, H.L. , De Koster, C.G. and Cornelissen, B.J.C. (2004) A small, cysteine‐rich protein secreted by Fusarium oxysporum during colonization of xylem vessels is required for I‐3‐mediated resistance in tomato. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1373–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, S.J. and Salvesen, G.S. (2007) The apoptosome: signalling platform of cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela‐Buurlage, M.B. , Budai‐Hadrian, O. , Pan, Q. , Carmel‐Goren, L. , Vunsch, R. , Zamir, D. and Fluhr, R. (2001) Genome‐wide dissection of Fusarium resistance in tomato reveals multiple complex loci. Mol. Genet. Genomics, 265, 1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q.H. , Saijo, Y. , Mauch, S. , Biskup, C. , Bieri, S. , Keller, B. , Seki, H. , Ulker, B. , Somssich, I.E. and Schulze‐Lefert, P. (2007) Nuclear activity of MLA immune receptors links isolate‐specific and basal disease‐resistance responses. Science, 315, 1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons, G. , Groenendijk, J. , Wijbrandi, J. , Reijans, M. , Groenen, J. , Diergaarde, P. , Van der Lee, T. , Bleeker, M. , Onstenk, J. , De Both, M. , Haring, M. , Mes, J. , Cornelissen, B. , Zabeau, M. and Vos, P. (1998) Dissection of the Fusarium I2 gene cluster in tomato reveals six homologs and one active gene copy. Plant Cell, 10, 1055–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speth, E.B. , Lee, Y.N. and He, S.Y. (2007) Pathogen virulence factors as molecular probes of basic plant cellular functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, E.A. and Bishop, J.G. (2000) Plant–pathogen arms races at the molecular level. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenbrock, E.H. and McDonald, B.A. (2009) Population genetics of fungal and oomycete effectors involved in gene‐for‐gene interactions. Mol. Plant–Microbe. Interact. 22, 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken, F.L.W. and Tameling, W.I.L. (2009) To nibble at plant resistance proteins. Science, 324, 744–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameling, W.I.L. , Elzinga, S.D. , Darmin, P.S. , Vossen, J.H. , Takken, F.L.W. , Haring, M.A. and Cornelissen, B.J.C. (2002) The tomato R gene products I‐2 and Mi‐1 are functional ATP binding proteins with ATPase activity. Plant Cell, 14, 2929–2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tameling, W.I.L. and Takken, F.L.W. (2008) Resistance proteins: scouts of the plant innate immune system. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 121, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Tameling, W.I.L. , Vossen, J.H. , Albrecht, M. , Lengauer, T. , Berden, J.A. , Haring, M.A. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. and Takken, F.L.W. (2006) Mutations in the NB‐ARC domain of I‐2 that impair ATP hydrolysis cause autoactivation. Plant Physiol. 140, 1233–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Does, H.C. , Lievens, B. , Claes, L. , Houterman, P.M. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. and Rep, M. (2008) The presence of a virulence locus discriminates Fusarium oxysporum isolates causing tomato wilt from other isolates. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Hoorn, R.A. , De Wit, P.J.G. and Joosten, M.H.A.J. (2002) Balancing selection favors guarding resistance proteins. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Hoorn, R.A. and Kamoun, S. (2008) From Guard to Decoy: a new model for perception of plant pathogen effectors. Plant Cell, 20, 2009–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen, G. , Mayr, G. , Albrecht, M. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. and Takken, F.L.W. (2008) Transcomplementation, but not physical association of the CC‐NB‐ARC and LRR domains of tomato R protein Mi‐1.2 is altered by mutations in the ARC2 subdomain. Mol. Plant, 1, 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ooijen, G. , Van Den Burg, H.A. , Cornelissen, B.J.C. and Takken, F.L.W. (2007) Structure and function of resistance proteins in solanaceous plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 45, 43–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volin, R.B. and Jones, J.P. (1982) A new race of Fusarium‐wilt of tomato in Florida and sources of resistance. Proc. Fla. State. Hort. Soc. 95, 268–270. [Google Scholar]