SUMMARY

Triggering of defences by microbes has mainly been investigated using single elicitors or microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), but MAMPs are released in planta as complex mixtures together with endogenous oligogalacturonan (OGA) elicitor. We investigated the early responses in Arabidopsis of calcium influx and oxidative burst induced by non‐saturating concentrations of bacterial MAMPs, used singly and in combination: flagellin peptide (flg22), elongation factor peptide (elf18), peptidoglycan (PGN) and component muropeptides, lipo‐oligosaccharide (LOS) and core oligosaccharides. This revealed that some MAMPs have additive (e.g. flg22 with elf18) and even synergistic (flg22 and LOS) effects, whereas others mutually interfere (flg22 with OGA). OGA suppression of flg22‐induced defences was not a result of the interference with the binding of flg22 to its receptor flagellin‐sensitive 2 (FLS2). MAMPs induce different calcium influx signatures, but these are concentration dependent and unlikely to explain the differential induction of defence genes [pathogenesis‐related gene 1 (PR1), plant defensin gene 1.2 (PDF1.2) and phenylalanine ammonia lyase gene 1 (PAL1)] by flg22, elf18 and OGA. The peptide MAMPs are potent elicitors at subnanomolar levels, whereas PGN and LOS at high concentrations induce low and late host responses. This difference might be a result of the restricted access by plant cell walls of MAMPs to their putative cellular receptors. flg22 is restricted by ionic effects, yet rapidly permeates a cell wall matrix, whereas LOS, which forms supramolecular aggregates, is severely constrained, presumably by molecular sieving. Thus, MAMPs can interact with each other, whether directly or indirectly, and with the host wall matrix. These phenomena, which have not been considered in detail previously, are likely to influence the speed, magnitude, versatility and composition of plant defences.

INTRODUCTION

Innate immunity is the first line of defence against invading pathogenic microorganisms in vertebrates, invertebrates and plants. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize and trigger defences in response to conserved structures called microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) (Abramovitch et al., 2006; Aslam et al., 2008; He et al., 2007; Kunze et al., 2004). MAMPs are mainly surface‐associated molecules that mostly cannot be readily altered and are typical of classes of microorganisms. Bacterial pathogens betray their presence when invading hosts by releasing various MAMPs, including the following: flagellin (flg), the main peptide component of the motility organ [a constituent peptide flg22 is used here and is recognized through the receptor flagellin‐sensitive 2 (FLS2)] (Gomez‐Gomez and Boller 2000); elongation factor Tu (EF‐Tu), which is essential for protein translation and is the most abundant bacterial protein [the peptide elf18 is used here and is recognized through the receptor EFR] (Zipfel et al., 2006); and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a glycolipid component of Gram‐negative outer membranes [here we use a lipo‐oligosaccharide (LOS) and component core oligosaccharides from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris] (Erbs and Newman, 2009; Silipo et al., 2005). Recently, we have shown that peptidoglycan (PGN), an essential component of the cell envelope, and, especially, muropeptides released from PGN by lysozyme are also perceived by plants (Erbs et al., 2008) [here we use native PGN from X. campestris pv. campestris and a mixture of peptides from PGN enzymatic hydrolysis]. Receptors have not been identified for PGN or LPS.

MAMPs are shed (e.g. LPS), turned over (PGN) (Park, 1995) or degraded by host enzymes (PGN; fungal glucan and chitin) (Brunner et al., 1998; Dow et al., 2009; Erbs et al., 2008). Although EF‐Tu functions in protein translation, it has been found in the secretomes of several plant pathogens and can aggregate and form on the cell surface and contribute to attachment (Kunze et al., 2004; Zipfel et al., 2006). In addition, plant defence components can cause leakage from invading bacterial cells.

Pathogen challenge can also release, through microbial or host pectic enzymes, a host‐derived elicitor from the pectic matrix of the cell wall in the form of oligogalacturonan (OGA) (Denoux et al., 2008; Navazio et al., 2002) [here we use an enzymatic digest comprising oligomers of degree of polymerization (DP) 6–20].

A typical array of early defence responses induced by MAMPs includes Ca2+ and H+ influx and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide and ethylene. Later, cell walls are reinforced and antimicrobial compounds are synthesized. Much of this follows the activation of calcium‐dependent protein kinases and mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, leading to transcriptional changes of many defence‐related genes (de Torres et al., 2003; He et al., 2007; Zipfel et al., 2006).

It is now appreciated that bacterial pathogens possess an array of Type III secreted protein effectors which suppress MAMP‐induced innate immunity. Some effectors, such as AvrPto from Pseudomonas syringae, counter multiple defences triggered by multiple MAMPs. Effectors target defence components, such as receptor kinases, signalling pathways, programmed cell death, ubiquitination, vesicle trafficking and cell wall reinforcement (He et al, 2007; Jones and Dangl, 2006, Shan et al., 2008, Xiang et al., 2008). Plants have evolved to recognize these effectors, directly or indirectly, via the products of resistance genes. The resulting typical phenotype is the hypersensitive response (HR) (Abramovitch et al., 2006; Jones and Dangl, 2006).

Recently, we have shown that bacterial pathogens also suppress defences through the production of high‐molecular‐weight (0.5–2 MDa) extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs) (Aslam et al., 2008). These have long been linked with pathogenicity or full virulence of the majority of diverse bacterial pathogens, but have mainly been ascribed protective functions (for example, Kemp et al., 2004). However, these polyanionic EPSs, which are produced in large amounts in the apoplast, suppress the perception of MAMPs in Arabidopsis and Phaseolus vulgaris by their ability to chelate calcium ions from the apoplastic pool (Aslam et al., 2008). Calcium influx from apoplast to symplast is a prerequisite for myriad defence responses (Lecourieux et al., 2006), and therefore defences are prevented or reduced if the cation is depleted (Aslam et al., 2008).

As part of a study on the suppression of MAMP‐ and bacterial‐induced Ca2+ signalling by EPSs, we considered that MAMPs, rather than being released singly in planta, are likely to be presented as a cocktail, and could interact, directly or indirectly, in defence elicitation. It is evident from the discovery of EF‐Tu through the defence‐eliciting activities of various bacteria known to lack flagellin (Kunze et al., 2004) and from the enhanced susceptibility of efr mutants to Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Zipfel et al., 2006) that plants recognize multiple MAMPs. In addition, flagellin‐impaired mutants (fliC) of P. syringae and Escherichia coli induced a similar transcriptional response to that by wild‐type cells (Thilmony et al., 2006). Guard cells recognize multiple MAMPs, as revealed by the induction of the closure of stomata in fls2 Arabidopsis epidermis by LPS but not flg22 (Melotto et al., 2006).

We also observed that diverse MAMPs display different calcium signatures. Calcium signatures (duration, amplitude and pattern of induced intracellular calcium levels) have been linked to various plant responses (Knight et al. 1996; Lecourieux et al., 2006).

It is also evident that some MAMPs are far less effective (in terms of minimum concentration required or host response time) than others at inducing defences. In part, this indicates a size effect, because the small peptides flg22 and elf18 are far more potent than macro‐ or supramolecular PGN and LOS. It is tenable that the movement of MAMPs to their plasma membrane or cytosolic receptors in plant cells is impaired by the host cell wall matrix, which can influence molecular passage in two ways. Plant cell walls function as a molecular sieve as well as possessing an overall negative charge (Cooper, 1983; Tepfer and Taylor, 1981). Thus, MAMP size and charge are likely to affect mobility during bacterial–host exchange.

In this study, we selected low, non‐saturating concentrations of MAMPs to examine their ability, singly and in combination, to trigger calcium influx and, in some cases, the production of ROS in Arabidopsis. We compared the induction by these MAMPs of several early and late defence‐related genes representing different signalling pathways, in the event that different MAMPs may trigger different defence networks and these differences may relate to MAMP calcium signatures. We compared movement through a plant cell wall column of two MAMPs with contrasting eliciting activities and sizes. This revealed that the quantitative and, to a lesser extent, qualitative elicitation of defences by MAMPs are partly dictated by exposure to MAMP combinations, to individual MAMPs (possibly relating to their induced calcium influx signatures) and to MAMP interactions with the host cell wall matrix.

RESULTS

MAMP combinations reveal additivity, synergy and interference

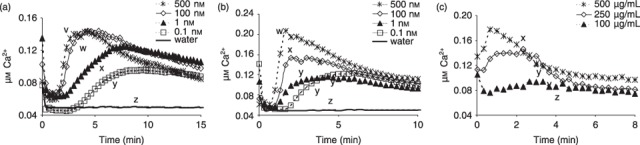

In order to test possible additivity, synergy or interference between MAMPs, we first needed to establish the lowest effective concentrations that would induce significant and repeatable host responses. This would avoid one MAMP saturating the influence of another. The lowest effective concentrations for causing significant calcium influx in Arabidopsis plants expressing aequorin were as follows: flg22, 0.1 nm; elf18, 0.1 nm; LOS, 50 µg/mL; core oligosaccharides (from LOS), 5 µg/mL; OGA, 50 µg/mL. PGN and muropeptides are used later, but not shown here, as they are unusual in being virtually ineffective at inducing calcium influx, yet are capable of eliciting other defence responses (see Erbs et al., 2008). The effects of the concentration of three MAMPs on calcium influx are shown in Fig. 1. For example, with decreasing elf18 concentration, the profile for the induction of intracellular calcium flattens and peak elicitation is delayed, e.g. from 3 min at 500 nm to 8–12 min at 0.1 nm (Fig. 1A). Similar trends with decreasing concentration were found with flg22 and OGA (Fig. 1B,C). The concentrations eventually chosen that gave reproducible host responses are shown in 2, 3. Higher levels were needed for ROS induction than for calcium influx, and, in one case, increased concentrations were also used to investigate possible interactions between MAMPs.

Figure 1.

Effect of concentrations of three microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) on the induction of calcium ion influx in Arabidopsis leaves. (A) Elongation factor peptide elf18. (B) Flagellin peptide flg22. (C) Oligogalacturonan (OGA). All showed similar trends of slower and lower induction of calcium influx with decreasing concentrations. All data are means of at least three replicates. Significant differences (different letters) between treatments were detected by the Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test.

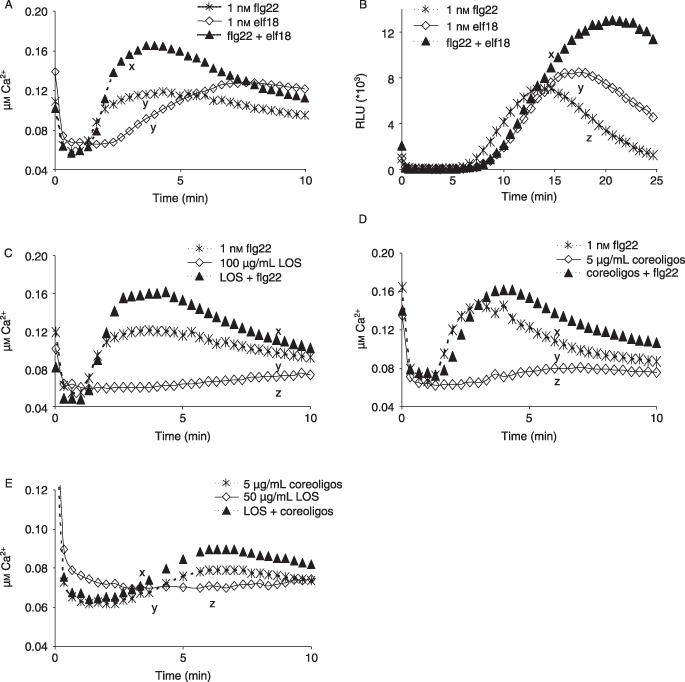

Figure 2.

Microbe‐associated molecular pattern (MAMP) combinations show additive effects in the induction of calcium ion influx or reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in Arabidopsis leaves. (A) Flagellin peptide flg22 and elongation factor peptide elf18 in combination enhance induced calcium influx. (B) flg22 and elf18 in combination enhance the generation of ROS as peroxide (RLU, relative light units). (C) flg22 and lipo‐oligosaccharide (LOS) in combination result in higher calcium influx. (D) flg22 and core oligosaccharides in combination induce a higher calcium influx than individual MAMPs. (E) LOS and core oligosaccharides show additive effects in calcium influx induction. All data are means of at least three replicates. Significant differences (different letters) between treatments were detected by Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test.

Figure 3.

Microbe‐associated molecular pattern (MAMP) combinations show interference in the induction of calcium influx or reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in Arabidopsis. (A) Flagellin peptide flg22 and peptidoglycan (PGN) in combination reduce the calcium influx triggered by flg22. (B) flg22 and hydrolysed PGN in combination reduce flg22‐induced calcium influx. (C) Oligogalacturonan (OGA) and flg22 in combination reduce flg22‐induced calcium influx. (D) OGA and flg22 in combination reduce the flg22‐induced oxidative burst (RLU, relative light units). Note that, in this example, interference occurred between MAMPs, even when both were used at higher concentrations than in other experiments. (E) OGA and elongation factor peptide elf18 in combination reduce the calcium influx induced by elf18. (F) In bak1– plants, the flg22‐induced oxidative burst is reduced by OGA. Note that the level of peroxide generated in response to flg22 is markedly lower than in the Arabidopsis Col‐0 plants shown in (D). All data are means of at least three replicates. Significant differences (different letters) between treatments were detected by Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test.

Calcium influx always preceded ROS formation, as found by others (Garcia‐Brugger et al., 2006; Navazio et al., 2002).

MAMPs were tested alone and in combination to determine the induction of calcium influx or oxidative burst as early defence‐associated responses in Arabidopsis Col‐0 leaves.

There was a significant enhancement of MAMP‐induced calcium ion influx when the following MAMPs were combined, compared with the effect of the individual MAMPs: flg22 + elf18 (Fig. 2A), flg22 + LOS (Fig. 2C), flg22 + core oligosaccharides (Fig. 2D) and LOS + core oligosaccharides (Fig. 2E). These increases were additive, except for flg22 and LOS, where there appears to be synergy. ROS induction confirmed the additive effects shown between flg22 and elf18 (Fig. 2B).

In contrast, some MAMPs showed mutual interference, revealed as reduced calcium influx when Arabidopsis was challenged with two MAMPs concurrently: flg22 + PGN (Fig. 3A), flg22 + PGN muropeptides (Fig. 3B), flg22 + OGA (Fig. 3C) and elf18 + OGA (Fig. 3E). Measurement of induced ROS, assayed as peroxide, confirmed the interference between flg22 and OGA, when the typically high response to flg22 alone was reduced by more than 90% (Fig. 3D).

In addition, we tested the possible interaction between flg22 and OGA on bak1– plants, in view of the flg22‐induced association between FLS2 and the receptor‐like kinase (RLK) BAK1, and the reduced defence induction by flg22 in spite of its normal binding to bak1– plants (Chinchilla et al., 2007). In concordance with previous findings, flg22 induced much lower, but still significant, generation of ROS in bak1– plants compared with that in Col‐0 plants, but again this was markedly suppressed by OGA (Fig. 3F).

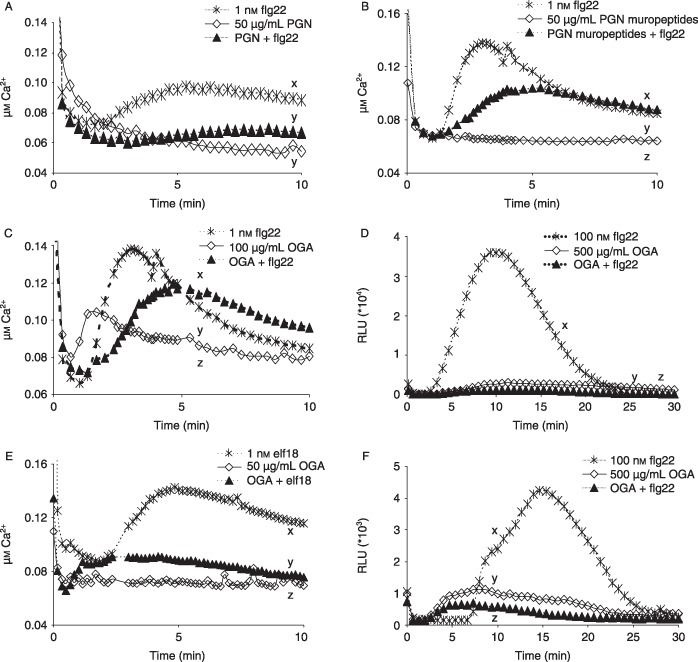

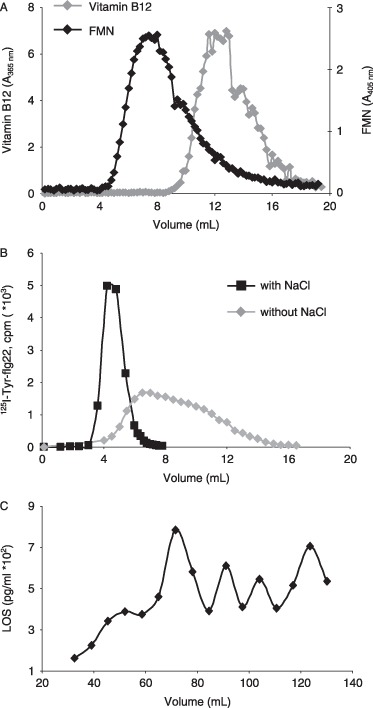

Significantly, OGA did not prevent binding of 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 to its specific receptor FLS2 on Arabidopsis cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Oligogalacturonan (OGA) does not reduce flagellin peptide flg22 binding to Arabidopsis cells. (A) Pretreatment of Arabidopsis cells for 30 min with 50 µg/mL OGA, followed by exposure to 0.4 nm 125I‐Tyr‐flg22. (B) Exposure of cells to a mixture of 0.4 nm 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 and 0.5, 1, 2.5 and 5 mg/mL OGA. There were no significant differences with OGA concentration, and therefore only 500 µg/mL OGA is shown here. Arabidopsis cells were incubated with 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 either alone (total binding; grey columns) or with an excess of 10 µm unlabelled flg22 (non‐specific binding; open columns). To determine specific binding, non‐specific binding is subtracted from total binding (mean of three replicates ± standard deviation).

The interference between flg and OGA in terms of calcium influx and flg22 binding in Col‐0 plants and cells, respectively, was similar when MAMPs were added concurrently or pre‐incubated for 30 min or 1 h (data not shown for leaves; for cells, see Fig. 4).

MAMPs elicit different calcium signatures and can induce the expression of different defence‐related genes

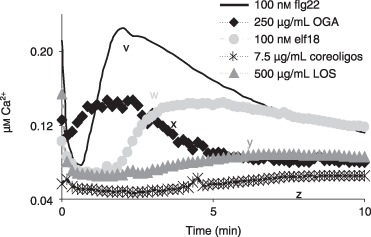

A comparison of calcium influx patterns revealed relatively characteristic calcium signatures for each MAMP (Fig. 5). For example, flg22 induced a rapid (c. 2 min) response, usually with two or three minor, decreasing peaks, whereas elf18 was less defined and broader. The OGA signature was rapid, but irregular, perhaps reflecting the probable range of molecular sizes present (Hahn et al., 1992). To support this possibility, size homogeneous fractions of OGA showed a regular pattern (Navazio et al., 2002). It should be noted, however, that the calcium signature can alter markedly with the concentration used to challenge plants, as shown for elf18 (Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Calcium signatures: patterns of cytoplasmic calcium ion influx induced in Arabidopsis by five bacterial microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). These concentrations were chosen to give maximum or near‐maximum responses and to reveal the most characteristic signatures. (See Fig. 1, which shows the influence of concentration on elf18, flg22 and OGA signatures.) All data are means of at least three replicates. Significant differences (different letters) between treatments were detected by Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test. flg22, flagellin peptide; elf18, elongation factor peptide; LOS, lipo‐oligosaccharide; OGA, oligogalacturonan.

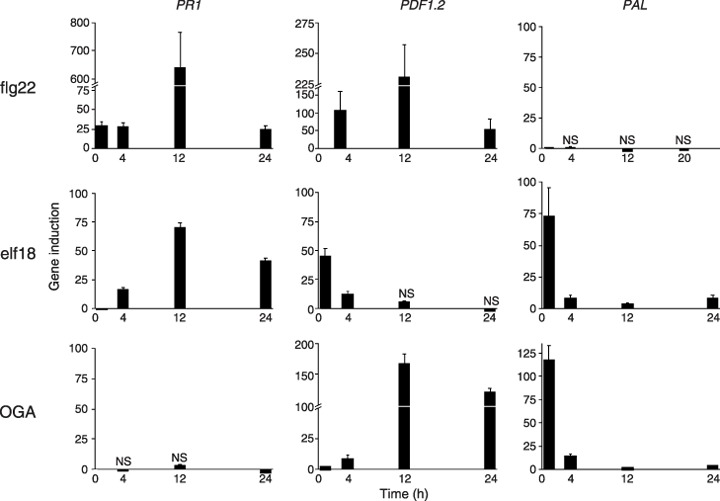

It remained possible that the calcium signature might determine which defence pathway was activated. Three MAMPs were used to challenge Arabidopsis leaves and, of the five defence‐related genes investigated (see Aslam et al., 2008), three showed differential induction. Thus, flg22 triggered the induction of defence‐related genes pathogenesis‐related gene 1 (PR1) and plant defensin gene 1.2 (PDF1.2), but did not induce phenylalanine ammonia lyase gene 1 (PAL1), whereas OGA caused the up‐regulation of PDF1.2 and PAL1, and elf18 induced all three genes (Fig. 6). When they were triggered, all genes were highly up‐regulated (≥ 50‐fold gene induction); PR1 and PDF1.2 showed maximal expression at 12 h, and PAL1 was rapidly triggered by 2 h with a marked decline by 4 h.

Figure 6.

Expression of three defence‐related genes in Arabidopsis leaves challenged by three bacterial microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), obtained by real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). Data are the mean of two replicates ± standard deviation. Data significant at P < 0.001 unless marked as NS (not significant). Three independent biological repetitions of each experiment were performed with similar results. The data shown from one experiment are therefore representative. elf18, elongation factor peptide; flg22, flagellin peptide; OGA, oligogalacturonan; PAL1, phenylalanine ammonia lyase gene 1; PDF1.2, plant defensin gene 1.2; PR1, pathogenesis‐related gene 1.

Host cell wall matrix may restrict MAMPs by size and charge effects

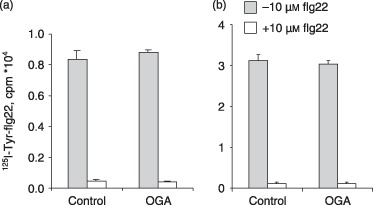

The efficacy of MAMPs as elicitors of defences may be determined in part by their mobility, which in turn could be size and charge dependent. A column with extracted plant cell walls (ex. Lycopersicon esculentum) as the matrix was prepared according to Tepfer and Taylor (1981). This matrix showed the properties of a sizing column, using the markers vitamin B12 (molecular weight, 1350 Da) and flavin mononucleotide (FMN) (molecular weight, 514 Da), although the resolving power of this matrix is not high, as found by Tepfer and Taylor (1981) (Fig. 7A). flg22 (2229 Da) was compared with LOS (3099 Da, but aggregates form). This analysis required the availability of radiolabelled flagellin 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 and a highly sensitive assay [Limulus Amoebocyte Chromogenic Endpoint (LAL) assay] for LOS. Other MAMPs, including intact flagellin and EF‐Tu, could not be tested because of a lack of sufficient pure product, the unavailability of facile assays or interference with assays from the column matrix, which released cell wall components such as uronides.

Figure 7.

Influence of a plant cell wall matrix on the movement of two bacterial microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). (A) A cell wall (ex. Lycopersicon esculentum) column (0.5 × 15 cm) shows molecular sieving properties using two size markers (FMN, flavin mononucleotide). Markers and MAMPs were eluted with 10 mm phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing 3 mm sodium azide. (B) Elution of flagellin peptide flg22 (125I‐Tyr‐ flg22) through the cell wall column in the presence and absence of 0.5 m NaCl. Radiolabelled flg22 was determined by γ‐counting. (C) Elution of lipo‐oligosaccharide (LOS) through the cell wall column. LOS was assayed by Limulus Amoebocyte Chromogenic Endpoint (LAL) assay.

125I‐Tyr‐flg22 passed rapidly through as a well‐defined peak (eluted within 6 mL) in the presence of 0.5 m NaCl (added to remove cell wall ion‐exchange properties). However, the peptide was significantly hindered in the absence of NaCl, as revealed by a slower, broader elution pattern until c. 16 mL. This effect shows that the charged cell wall restricts the passage of this MAMP (Fig. 7B). In contrast, LOS passed slowly through the cell wall matrix and showed a repeating pattern suggestive of molecular size groups. Elution was still detected after 140 mL, when only a very small proportion of the original applied amount was found (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

The minimum concentrations of MAMPs required to elicit host responses reported here are in broad agreement with previous work on flg22 (Felix et al., 1999), elf18 (Kunze et al., 2004; Zipfel et al., 2006), LPS (Dow et al., 2009) and OGA (Navazio et al., 2002). Different values often reflect which early response is examined, such as alkalinization, calcium influx and ROS generation, as well as the host material used, which may be cells (Erbs et al., 2008; Felix et al., 1999), immersed seedlings (Denoux et al., 2008) and infiltrated leaves (Aslam et al., 2008), and may be from different species. For example, with Arabidopsis cells, flg22 and elf18 are active at 30 pm to cause a pH increase (Felix et al., 1999; Zipfel et al., 2006), but, in leaves, 10 nm flg and elf18 are required to induce ROS (Felix et al., 1999; Kunze et al., 2004). Usually, as found in this study, it has been reported that higher levels of MAMPs are required to induce ROS than calcium influx and alkalinization (for example, Navazio et al. 2002).

MAMP concentrations released in the apoplast are unknown and their detection is technically challenging. What may be critical, however, is not only that the magnitude of expression of individual defence‐related genes is dose dependent, but whether there is an activation threshold determined by MAMPs reaching the sites of elicitor perception (Denoux et al., 2008). Also critical is the possible effect on the host of simultaneous exposure to multiple MAMPs.

Bacterial elicitors are likely to be released as a complex mixture at any one time, but there is little direct evidence for the presence of any one MAMP during the infection of plants. LPS has been detected in human serum (Hellman et al., 2000; Post et al., 2005), and PGN is released during infection by Helicobacter pylori and Bordetella pertussis (Cloud‐Hansen et al., 2006). In plants, evidence is indirect, with MAMP receptor mutants revealing that MAMPs are being perceived from invading bacterial pathogens. Thus, fls2 Arabidopsis mutants lacking the functional flg22 receptor are more susceptible to spray inoculation with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Zipfel et al., 2004). In addition, efr‐1 plants are more susceptible to Agrobacterium tumefaciens (shown by the enhanced number of transformation events), revealing that EF‐Tu is detected (Zipfel et al., 2006). The presence of FLS2 contributes to the basal defence of Arabidopsis accessions, because virulence enhancement by P. syringae pv. phaseolicola AvrPtoB is reduced in accessions containing the flagellin receptor (de Torres et al., 2006). In addition, in the non‐host interaction between Arabidopsis and P. syringae pv. tabaci, a mutant lacking flagellin did not induce the NHO1 gene required for resistance to multiple strains of non‐host P. syringae, but multiplied more than the wild‐type and caused disease symptoms (Li et al., 2005). Other evidence concerns silencing of NbFls2 (the equivalent flg22 receptor gene in Nicotiana benthamiana), which results in increased growth of compatible, non‐host and non‐pathogenic strains of P. syringae (Hann and Rathjen, 2007). In addition, basal defences expressed as cell wall modifications to a non‐pathogenic hrcC mutant of X. campestris pv. vesicatoria were attributed to LPS, which, when purified, reproduced the ultrastructural wall changes observed in response to bacterial cells (Keshavarzi et al., 2004). Transcriptional profiling with hrp– mutants of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 lacking a functional type III system showed that host transcriptional reprogramming in the first few hours results from MAMPs, rather than from type III effectors (de Torres et al., 2003).

In view of the likely simultaneous release of several MAMPs, we investigated possible interactions between them; there have been few attempts to do this (Zipfel et al., 2006). Additivity was evident for flg22 with elf18, flg22 with core oligosaccharides, and LOS with core oligosaccharides. flg22 and LOS appear to show a synergistic effect, as the host response strongly exceeds the sum of the individual responses. Zipfel et al. (2006) described additive effects between 0.03 nm flg22 and elf18 for a pH increase of Arabidopsis cells, but no enhancement in tissues for the induction of MAPK or resistance to P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 when MAMPs were used at saturating levels of 100 nm. They suggested that the non‐additive effect for MAPKs indicates that signalling by these two MAMPs appears to converge upstream of these kinases. Our strategy of choosing the lowest MAMP concentrations to give reproducible host tissue responses (calcium influx and/or oxidative burst) has shown that there can be interplay between diverse MAMPs.

On the basis of current knowledge, the interpretation of additive or synergistic effects must remain speculative. One possibility is the general induction of genes for specific receptors by MAMPs. To support this hypothesis, the flg22 receptor FLS2 is one of more than 100 rapidly induced RLK genes produced by both flg22 and elf18; furthermore, treatment with flg22 and elf18 results in increased specific binding sites for both MAMPs within 1–2 h (Zipfel et al., 2006). However, the kinetics do not explain the almost immediate synergistic effect required to influence calcium influx and oxidative burst, as observed in this study. Nevertheless, the increase in binding sites found by Zipfel et al. (2006) was about two‐ to threefold, which is within the range of the additive effects found here. Presumably, these MAMPs do not cross‐react because receptors for EF‐Tu and flagellin function independently, as shown by the specific responses of non‐members of Brassicaceae to flg22, but not to elf18, and an Arabidopsis mutant with a mutation in FLS2, which still responded normally to EF‐Tu (Kunze et al., 2004). In addition, both the components of LOS, i.e. lipid A and core oligosaccharides, show eliciting activity, but induce defence‐related transcription in two distinct phases (Silipo et al., 2005). This fact and their very different compositions suggest that host responses occur via distinct host receptors. It is noteworthy, therefore, that, even when used at high concentrations, the defence‐inducing abilities of the LOS components were found here to be additive.

Whatever the underlying mechanism(s), additive effects caused by multiple MAMPs could signal a more drastic host response in the face of a major pathogen challenge, rather than the mere activation of basal defences. In addition, the recognition of multiple MAMPs should ensure pathogen detection. Some pathogens seem to have evolved forms of MAMPs much less active in elicitation, such as flagellins from A. tumefaciens and Sinorhizobium meliloti (Felix et al., 1999) and from X. campestris pv. campestris (Sun et al., 2006), PGN from A. tumefaciens (Erbs et al., 2008) and EF‐Tu from P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Kunze et al., 2004).

Conversely, interference occurred between flg22 and PGN, flg22 and PGN muropeptides and, especially, flg22 and OGA. Likewise, elf18 and OGA showed mutual interference. Mutual interference could conceivably result from competition for binding sites. However, we have no knowledge of the nature of PRRs in plants for LOS or PGN and their component MAMPs, or for OGA, but these are likely to be dissimilar in view of the contrasting compositions of these three MAMPs. This idea is supported by the failure of OGA to prevent flg22 binding to its FLS2 receptor on Arabidopsis cells.

OGA also suppressed flg22 induction of ROS in bak1– mutant plants. BAK1 is a promiscuous leucine‐rich repeat (LRR)‐RLK involved in brassinosteroid signalling, and forms a complex with FLS2 in vivo (Heese et al., 2007). This mutation does not alter flg22 binding, but reduces early and late flagellin‐triggered responses, and also early EF‐Tu‐triggered responses (Chinchilla et al., 2007). We have confirmed here the reduced induction of ROS by flg22 (and by elf18, data not shown) in bak1– plants compared with that in Col‐0 plants. Thus, the suppressive effect of OGA is not exerted at the level of BAK1. Possible chemical interactions between flg22 and OGA are currently under investigation. However, another possibility concerns interference through calcium binding by OGA, in the light of the suppression of defence signalling following the chelation of apoplastic calcium, as described by Aslam et al. (2008). This hypothesis may be negated, however, by the findings of Cabrera et al. (2008), who showed that the elicitor active form of OGA may be the calcium cross‐linked egg‐box conformation.

The calcium ion is recognized as a second messenger in numerous plant signalling pathways, and influx from the apoplast to the cytosol (where levels are c. 104‐fold less), where it is decoded by various calcium sensor proteins, is a prerequisite for most defence responses (Aslam et al., 2008; Lecourieux et al., 2006). Animal and plant cells show spatial and temporal changes to cytoplasmic calcium levels, and different stimuli can be associated with particular calcium signatures, which may contribute to the specificity of the outcome. The patterns may comprise single transients, oscillations and repeat spikes with different lag times, amplitude and frequency. Most MAMPs (but not all; see Erbs et al., 2008; Garcia‐Brugger et al., 2006) result in calcium influx and can show characteristic signatures. Some are detailed by Lecourieux et al. (2002, 2006). Here, we show patterns of calcium influx with five diverse MAMPs comprising peptides, glycopeptides, lipo‐oligosaccharides and oligosaccharides, and attempt to link these with the induction of different defence genes. Only Lecourieux et al. (2002) compared calcium signatures of diverse elicitors, and the major MAMPs known from bacteria have not been compared together in one system previously.

An alternative view on calcium signalling comes from Scrase‐Field and Knight (2003). They propose that with one or few exceptions, such as guard cell behaviour, calcium simply acts as a switch to activate calcium‐sensitive signal transduction components. Indeed, any signal specificity might be questioned when, as shown here, the calcium signatures of these bacterial MAMPs are relatively similar. More importantly, the signatures change markedly with MAMP concentration. Thus, the lag period, amplitude and duration all alter substantially as the concentrations of elf18, flg22 and OGA are decreased from 1 µm to 0.1 nm.

However, the three MAMPs flg22, elf18 and OGA induced three defence‐related genes differently. Thus OGA induced PAL and PDF1.2, but not PR1, flg22 failed to induce PAL, and elf18 resulted in the up‐regulation of all three. Various transcriptional profiling studies, including full genome studies in Arabidopsis with flg22, elf18 and OGA, fungal MAMPs and responses to hrp– mutants of P. syringae, have shown considerable overlap in responses to different elicitors (Moscatiello et al., 2006; Ramonell et al., 2002; Thilmony et al., 2006; Truman et al., 2006; Zipfel et al., 2004, 2006). This overlap suggests that all elicit a conserved basal response resulting from the convergence of a limited number of signalling pathways (Jones and Dangl, 2006).

Nevertheless, in agreement with Denoux et al. (2008), in this study, we found that flg22, but not OGA, induced a recognized salicylic acid pathway marker, PR1, and with similar kinetics. They found highly correlated early responses (in particular, those associated with jasmonic acid) with the two MAMPs, but differences in the late responses. Even at very high doses (1250 µg/mL), they found that OGA did not induce such a comprehensive response as that given by flg22, and the kinetics of induction differed. That OGA clearly differs in the induction of defence genes may reflect the fact that it is of endogenous origin and designed to stimulate different responses to those triggered by microbial elicitors.

PAL1 induction by elf18, but not by flg22, appears to be one exception to the results of Zipfel et al. (2004), which revealed that the two MAMPs induced near‐identical sets of genes, in spite of their distinct receptors. PAL1 was, however, induced by flg22 according to Denoux et al. (2008). This might be explained by the influence on host responses of the very different systems used. We infiltrated leaves from short‐day plants with MAMPs, whereas Denoux et al. (2008) used 10‐day‐old seedlings exposed to a 16‐h photoperiod and immersed in liquid growth medium. Another notable disparity was the absence of PDF1.2, which did not increase by 3 h in immersed seedlings, but underwent substantial up‐regulation in our work. Notably, early genes were commented on by Denoux et al. (2008) as often functionally enriched for the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds, and we found that PAL kinetics resembled a transient, early gene.

In summary, it appears that different MAMPs, alone and in combination, will contribute to the magnitude and composition of plant defences, presumably responding when particular thresholds are achieved and influencing the expression of different defence networks.

Plant cell wall permeability is determined by the existence within the matrix and between microfibrils of pores or capillaries, and can restrict the ability of elicitors and other molecules to effect cell responses. Carpita et al. (1979) suggested that only small molecules could penetrate walls of living cells, equivalent to dextrans (6500 Da) and proteins (17 000 Da). However, Tepfer and Taylor (1981), employing the same approach as used in the current study, showed that much larger proteins (40 000–60 000 Da) can penetrate the wall space. This result was in the presence of 0.5 m NaCl to neutralize ion‐exchange interactions.

MAMPs are chemically diverse, as described earlier, and therefore each needs to be considered case‐by‐case in terms of size, charge and other physicochemical properties, such as solubility and aggregation. Clearly, flg22 was far more mobile in the wall matrix than LOS, which aggregates and is of limited solubility. However, the flagellin peptide was restricted by charge rather than size, as evident from greater mobility in the absence of 0.5 m NaCl. Nevertheless, in planta, flg22 is still very rapidly perceived, as shown by the induction of the early indicators of defence, such as Ca2+ influx, oxidative burst (min) and early genes (Aslam et al., 2008; Denoux et al., 2008; Zipfel et al., 2004). It should be noted that native flagellin, such as from P. syringae pv. tabaci, is c. 33 kDa, but, as with the flg22 domain, it elicits plant cells within a few minutes and at subnanomolar levels (Felix et al., 1999), and so evidently is not significantly constrained by the plant wall matrix.

LPS (and LOS) are amphiphilic molecules, and therefore tend to form three‐dimensional aggregates (some of which can be termed micelles), dependent on their hydrophobicity. Above a critical aggregate concentration, there is an equilibrium between free monomers and aggregates (Gutsman et al., 2007). Presumably, the repeating pattern evident during elution through the cell wall sizing column reveals a range of aggregate sizes. Theoretically, these would provide a relatively slow and long‐term defence elicitation compared with the small, fast‐acting flagellin and EF‐Tu peptides. The gradual and late pattern of calcium influx induced by LOS (2, 5) would fit this theory. A similar long‐duration calcium signal was found by Meyer et al. (2001) with X. campestris pv. campestris LPS in tobacco cells.

Animal cells are considerably more sensitive (pg/mL to ng/mL range) to LPS and PGN compared with plant cells (µg/mL range), although plant cells can show exquisite sensitivity to certain peptide and oligosaccharide MAMPs (Dow et al., 2009; Ramonell et al., 2002). It is likely that the plant cell wall barrier largely explains this difference to macromolecular MAMPs, limiting access to receptors. LPS, in particular, is released in vitro constitutively by Gram‐negative bacteria as a supramolecular form, visible as outer membrane blebs and detected as such in infected human plasma (Post et al., 2005) and ultrastructurally from X. axonopodis pv. manihotis in planta (Boher et al., 1997). These blebs can activate human monocytes and endothelial cells (Post et al., 2005), but, prima facie, are unlikely to be effective in this form in plants. Nevertheless, pure LPS from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria applied to pepper leaves appeared as an aggregate, yet triggered very localized host wall modifications (phenolic and callose deposition) (Keshavarzi et al., 2004); moreover, there are reports of LPS, when used at high concentrations, showing MAMP activity (Dow et al., 2009; Erbs and Newman, 2009). Possibly, LPS monomers are present in sufficient amounts to penetrate the wall to reach their putative receptor(s). Nevertheless, labelling of Xanthomonas LPS indicates that it is held up within the cell wall. Gross et al. (2005) described clusters of fluorescein‐tagged pure X. campestris pv. campestris LPS within cell walls, which were eventually taken up by cells after 2 h, and Boher et al. (1997) showed that gold–antibody‐tagged LPS accumulated within the cell wall of cassava infected by X. axonopodis pv. manihotis.

Clearly, we have much to learn about the form, amount and timing of bacterial MAMPs released at the pathogen–plant interface. It is clear, however, that some MAMPs can interact with each other, whether directly or indirectly, and with the host cell wall matrix.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant growth

Arabidopsis plants [accession Columbia (Col‐0) and bak1– mutants] were grown with supplementary lighting at 22 °C with an 8‐h photoperiod of 140 µE/m2/s.

MAMPs

flg22, 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 (supplied by T. Boller, Basel, Switzerland), EF‐Tu (elf18), PGN and derived peptides from X. campestris pv. campestris 8004 were obtained as described previously (Aslam et al., 2008; Erbs et al., 2008). LOS and core oligosaccharides from X. campestris pv. campestris are described by Silipo et al. (2005). OGAs (DP = 6–20) were prepared by a modified method from Hahn et al. (1992). Briefly, 2 g of polygalacturonic acid (sodium salt, Sigma P‐1879; Sigma‐Aldrich, Dorset, UK) in 1 L of 20 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 5) containing 2 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) was digested with 6 µL of pectinase (P‐4716, Sigma) for 6 h at 25 °C. Digestion was terminated by heating at 80 °C for 40 min. The resulting OGAs (DP = 6–20) were fractionated by low‐resolution ion‐exchange chromatography, and then desalted by dialysis using a 1000‐Da cut‐off dialysis membrane.

Calcium influx

Arabidopsis thaliana (Colombia, Col‐0), with Agrobacterium‐mediated expression of CaMV35S:apo‐aequorin (Knight et al., 1996), was used for the measurement of intracellular calcium, as described by Aslam et al. (2008). Leaf discs (5 mm in diameter) were floated in the dark at 25 °C for 4 h or overnight on 2.5 µm coelenterazine (Lux Biotechnology, Edinburgh, UK) to reconstitute aequorin. Two leaf discs were transferred to a cuvette containing 190 µL of water and normalized for 10–15 min; 10 µL of elicitors or water (control) was added and the luminescence was measured immediately with a single‐tube luminometer (Sirius, Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany). Luminescence counts were recorded every second, but for clarity are displayed graphically per 5, 10 or 20 s. At the end of each experiment, the remaining aequorin was discharged by the addition of 200 µL of 2 m CaCl2 in 60% ethanol. To test the effect of synergy and interference of MAMPs, elicitors were mixed just before exposure to the discs.

Oxidative burst

The effect of MAMPs on the production of ROS, measured as peroxide, was performed as described by Aslam et al. (2008). Leaf discs (7 mm in diameter) were normalized by floating overnight on water at 25 °C. Two leaf discs were transferred to a cuvette containing 180 µL of water and normalized for 10–15 min; 1 µL of 20 mm luminol, 1 µL of 10 mg/mL peroxidase (8.5 units, ex. horseradish, Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) and 20 µL of elicitors or water (control) were added. Luminescence was measured immediately with a single‐tube luminometer (Sirius, Berthold Detection Systems). Luminescence counts were recorded every second, but for clarity are displayed graphically per 5 s. To test the effect of synergy and interference of MAMPs, elicitors were mixed just before exposure to the discs. However, in one case, they were premixed for different durations, as stated in the text.

Analysis of defence gene induction by real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR)

MAMPs were dissolved in water at the required concentrations and infiltrated, using a syringe without a needle, into 6‐week‐old leaves of A. thaliana (Col‐0). A further set of leaves was infiltrated with water. The plants were placed in a growth cabinet at 25 °C with 8 h of light. The leaves were harvested 2, (3 or 4), 12 and 24 h after infiltration. The changes in gene expression were followed using quantitative, real‐time RT‐PCR analysis, as described previously (Aslam et al., 2008; Erbs et al., 2008).

Primer pairs for defence genes were as follows: PR1: PR1‐F, 5′‐GTGGGTTAGCGAGAAGGCTA‐3′; PR1‐R, 5′‐ACTTTGGCACATCCGAGTCT‐3′; PDF1.2: PDF1.2‐F, 5′‐TCACCCTTATCTTCGCTGCT‐3′; PDF1.2‐R, 5′‐ACTTGGCTTCTCGCACAACT‐3′; PAL1: PAL1‐F, 5′‐TTCAAGGGAGCTGAGATTGC‐3′; PAL1‐R, 5′‐GCTCTGCTGATTGAACATGG‐3′.

The 18SrRNA gene was used as reference gene; the primers for this gene are: 18SrRNA‐F, CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA; 18SrRNA‐R, GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT (Erbs et al., 2008).

flg22 binding with FLS2 receptor

Binding of 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 to its FLS2 receptor on Arabidopsis suspension‐cultured cells (Landsberg erecta Ler‐0) was performed as described by Aslam et al. (2008). To investigate possible interference by OGA, cells were either incubated with OGA added together with 125I‐Tyr‐flg22, or were first exposed to OGA before incubation with the flagellin peptide, as described in Fig. 4.

Diffusion of MAMPS through plant cell walls

Preparation of plant cell walls

Petioles and young succulent stems were harvested from tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum Mill cv. Craigella GCR26 (7 weeks old). Plants were grown under glasshouse conditions with supplementary lighting (16‐h photoperiod) in Levington's medium compost. The plant material was ground to a fine powder in the presence of liquid nitrogen. The cell walls were then extracted by a method adapted from Cooper et al. (1981) for extraction of hydrated walls with ionically bound proteins. After homogenization of plant material with 2 vol. of 0.05 m phosphate buffer (pH 6), aliquots of the resulting slurry were sonicated on ice 50–60 times (90% amplitude, 29 pulses during a 44‐s period using a thick probe) to remove cytoplasm from the cell wall and to aid comminution to small fragments. The slurry was then washed with excess 0.05 m phosphate buffer (pH 6) and filtered through Miracloth (pore size, 22–25 µm, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA); excess buffer was manually wrung from the cell wall extract.

Preparation of a cell wall column

A glass column (interior diameter, 5 mm × 15 cm; total volume, 11.78 mL) was packed with the slurry of cell wall material, as described by Tepfer and Taylor (1981), and then equilibrated with 10 mm phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing 3 mm sodium azide. Fifty microlitre samples of 20 mg/mL protein markers or MAMPs (1 mg) were loaded onto the column and eluted with 10 mm phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing 3 mm sodium azide. 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 was eluted similarly, but with and without 0.5 m NaCl. Two‐drop (200 µL) fractions were collected, but this was increased to five‐drop fractions for LOS, which was run without NaCl. Collected fractions of markers were diluted with an appropriate volume of water to measure the elution of FMN at A 450 and vitamin B12 at A 365.

MAMP detection

flg22 was detected as 125I‐Tyr‐flg22 by γ‐counting. LOS was detected by LAL assay, which measures endotoxin (LPS) at 1–1000 pg/mL (HyCult Biotechnology b.v., Canton, MA, USA), performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All work surfaces and containers were cleaned with E‐Toxa‐Clean (Sigma), and fractions were diluted with pyrogen‐free water (Baxter, Newbury, Berks, UK).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data, including analysis of variance (anova) and comparison of means by the Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference test, was performed using JMP software, version 7 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All data for real‐time RT‐PCR were significant after normalization to 18SrRNA in controls at P < 0.001, unless indicated as not significant (NS) (Aslam et al., 2008). Analyses were performed using the relative expression software tool (REST©), as described previously (Pfaffl et al., 2002).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge funding from The Leverhulme Trust to R.M.C and funding to M.‐A.N. from The Danish Council for Technology and Innovation. We thank Marc Knight (University of Durham, UK) for early inputs into calcium signalling.

REFERENCES

- Abramovitch, R.B. , Anderson, J.C. and Martin, G.M. (2006). Bacterial elicitation and evasion of plant innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, S.N. , Newman, M.‐A. , Erbs, G. , Morrissey, K.L. , Chinchilla, D. , Boller, T. , Tandrup Jensen, T. , De Castro, C. , Ierano, T. , Molinaro, A. , Jackson, R.W. , Knight, M.C. and Cooper, R.M. (2008) Bacterial polysaccharides suppress induced innate immunity by calcium chelation. Curr. Biol. 18, 1078–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boher, B. , Nicole, M. , Potin, M. and Geiger, J.P. (1997) Extracellular polysaccharides from Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. manihotis interact with cassava cell walls during pathogenesis. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 10, 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, F. , Stintzi, A. , Fritig, B. and Legrand, M. (1998) Substrate specificities of tobacco chitinases. Plant J. 14, 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, J.C. , Boland, A. , Messiaen, J. , Cambier, P. and Van Cutsem, P. (2008) Egg box conformation of oligogalacturonides: the time‐dependent stabilization of the elicitor‐active conformation increases its biological activity. Glycobiology, 18, 473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita, N.C. , Sabularse, D. , Montezinos, D. and Delmer, D.P. (1979) Determination of the pore size of cell walls of living plant cells. Science, 205, 1144–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla, D. , Zipfel, C. , Robatzek, S. , Kemmerling, B. , Nürnberger, T.N. , Jones, J.D.G. , Felix, G. and Boller, T. (2007) A flagellin‐induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature, 448, 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud‐Hansen, K.A. , Brook Petersen, S. , Stabb, E.V. , Goldman, W.E. , McFall‐Ngai, M.J. and Handelsman, J. (2006) Breaching the great wall: peptidoglycan and microbial interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.M. (1983) The mechanisms and significance of enzymic degradation of host cell walls In: Biochemical Plant Pathology (Callow J.A., ed.), pp. 101–137. Chichester, New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.M. , Wardman, P.A. and Skelton, J.E.M. (1981) The influence of cell walls from host and non‐host plants on the production and activity of polygalacturonide‐degrading enzymes from fungal pathogens. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 18, 239–255. [Google Scholar]

- De Torres, M. , Sanchez, P. , Fernandez‐Delmond, I. and Grant, M. (2003) Expression profiling of the host response to bacterial infection: the transition from basal to induced defence responses in RPM1‐mediated resistance. Plant J. 33, 665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Torres, M. , Mansfield, J.W. , Grabov, N. , Brown, I.R. , Ammouneh, H. , Tsiamis, G. , Forsyth, A. , Robatzek, S. , Grant, M. and Boch, J. (2006) Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPtoB suppresses basal defence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 47, 368–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoux, C. , Galletti, R. , Mammarella, N. , Gopalan, S. , Werck, D. , De Lorenzo, G. , Ferrari, S. , Ausubel, F.M. and Dewdney, J. (2008) Activation of defense response pathways by OGs and Flg22 elicitors in Arabidopsis seedlings. Mol. Plant, 1, 423–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow, M. , Molinaro, A. , Cooper, R.M. and Newman, M.A. (2008) Microbial glycosylated components in plant disease In: Microbial Glycobiology: Structures, Relevance and Application (Moran A., Brennan P., Holst O. and Von Itszstein M., eds). San Diego, CA, USA: Elsevier, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Erbs, G. and Newman, M.‐A. (2009) MAMPs/PAMPs—elicitors of innate immunity In: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria: Genomics and Molecular Biology (Jackson R.W., ed.), pp. 227–240. Norwich, UK: Caister Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erbs, G. , Silipo, A. , Aslam, S. , De Castro, C. , Liparoti, V. , Flagiello, A. , Pucci, P. , Lanzetta, R. , Parrilli, M. , Molinaro, A. , Newman, M.‐A. and Cooper, R.M. (2008) Peptidoglycan and muropeptides from pathogens Agrobacterium and Xanthomonas elicit plant innate immunity: structure and activity. Chem. Biol. 15, 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix, G. , Duran, J.D. , Volko, S. and Boller, T. (1999) Plants have a sensitive perception system for the most conserved domain of bacterial flagellin. Plant J. 18, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Brugger, A. , Lamotte, O. , Vandelle, E. , Bourgue, S. , Lecourieux, D. , Poinssot, B. , Wendehenne, D. and Pugin. A. (2006) Early signalling events induced by elicitors of plant defences. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 711–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez‐Gomez, L. and Boller, T. (2000) FLS2: an LRR receptor‐like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis . Mol. Cell. 5, 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, A. , Kapp, D. , Nielsen, T. and Niehaus, K. (2005) Endocytosis of Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris lipopolysaccharides in non‐host plant cells of Nicotiana tabacum . New Phytol. 165, 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutsman, T. , Schromm, A.B. and Brandenburg, K. (2007) The physiochemistry of endotoxins in relation to bioactivity. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M.G. , Darvill, A. , Albersheim, P. , Bergmann, C. , Cheong, J.‐J. , Koller, A. and Lo, V.‐M. (1992) Preparation and characterization of oligosaccharide elicitors of phytoalexin accumulation In: Molecular Plant Pathology: A Practical Approach, Vol. II (Gurr S.J., McPherson M.J. and Bowles D.J., eds), pp. 135–136. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, D.R. and Rathjen, J.P. (2007) Early events in the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae on Nicotiana benthamiana . Plant J. 49, 607–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, P. , Shan, L. and Sheen, J. (2007) Elicitation and suppression of microbe‐associated molecular pattern‐triggered immunity in plant–microbe interactions. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1385–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese, A. , Hann, D.R. , Giminez‐Ibanez, S. , Jones, A.M.E. , He, K. , Li, J. , Schroeder, J.I. , Peck, S.C. , Rathjen, J.P. (2007). The receptor‐like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 12 217–12 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman, J. , Loiselle, P.M. , Tehan, M.M. , Allaire, J.E. , Boyle, L.A. , Kurnick, J.T. , Andrews, D.M. , Sik Kim, K. and Warren, H.S. (2000) Outer membrane protein A, peptidoglycan‐associated lipoprotein, and murein liporotein are released by Escherichia coli bacteria into serum. Infect. Immun. 68, 2566–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, B.P. , Horne, J. , Bryant, A. and Cooper, R.M. (2004) Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. manihotis gumD gene is essential for EPS production and pathogenicity and enhances epiphytic survival on cassava (Manihot esculenta ). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 64, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzi, M. , Soylu, S. , Brown, I. , Bonas, U. , Nicole, M. , Rossiter, J. and Mansfield, J. (2004) Basal defences induced in pepper by lipopolysaccharides are suppressed by Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 17, 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, H. , Trewavas, A.J. and Knight, M.R. (1996) Cold calcium signaling in Arabidopsis involves two cellular pools and a change in calcium signature after acclimation. Plant Cell, 8, 489–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, G. , Zipfel, C. , Robatzek, S. , Niehaus, K. , Boller, T. and Felix, G. (2004) The N terminus of bacterial elongation factor Tu elicits innate immunity in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell, 16, 3496–3507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecourieux, D. , Mazars, C. , Pauly, N. , Ranjeva, R. and Pugin, A. (2002) Analysis and effect of cytosolic free calcium increases in response to elicitors in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia cells. Plant Cell, 14, 2627–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecourieux, D. , Raneva, R. and Pugin, A. (2006) Calcium in plant defence‐signalling pathways. New Phytol. 171, 249–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Lin, H. , Zhang, W. , Zou, Y. , Zhang, J. , Tang, X. and Zhou, J. (2005) Flagellin induces innate immunity in nonhost interactions that is suppressed by Pseudomonas syringae effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 12 990–12 995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotto, M. , Underwood, W. , Koczan, J. , Momura, K. and He, S.Y. (2006). Plant stomata function in innate immunity against bacterial invasion. Cell, 126, 969–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A. , Pühler, A. and Niehaus, K. (2001) The lipopolysaccharides of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris induce an oxidative burst in cell cultures of Nicotiana tabacum . Planta, 213, 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscatiello, R. , Mariani, P. , Sanders, D. and Maathuis, F.J.M. (2006) Transcriptional analysis of calcium‐dependent and calcium‐independent signalling pathways induced by oligogalacturonides. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2847–2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navazio, L. , Moscatiello, R. , Bellincampi, D. , Baldan, B. , Meggio, F. , Brini, M. , Bowler, C. and Mariani, P. (2002) The role of calcium in oligogalacturonide‐activated signalling in soybean cells. Planta, 215, 596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.T. (1995) Why does Escherichia coli recycle its cell wall peptides? Mol. Microbiol. 17, 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl, M.W. , Horgan, G.W. and Dempfle, L. (2002) Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group‐wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real‐time PCR. Nucleic Acids. Res. 30, e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post, D. , Zhang, D.‐S. , Eastvold, J.S. , Teghanemt, A. , Gibson, B.W. and Weiss, J.P. (2005) Biochemical and functional characterization of membrane blebs purified from Neisseria meningitides serogroup B. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38 383–38 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonell, K.M. , Zhang, B. , Ewing, R.M. , Chen, Y. , Xu, D. , Stacey, G. and Somerville, S. (2002) Microarray analysis of chitin elicitation in Arabidopsis thaliana . Mol. Plant Pathol. 3, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrase‐Field, S.A.M.G. and Knight, M. (2003) Calcium: just a chemical switch? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L. , He, P. , Li, J. , Heese, A. , Peck, S.C. , Nürnberger, T. , Martin, G. and Sheen, J. (2008) Bacterial effectors target the common signalling partner BAK1 to disrupt multiple MAMP receptor‐signalling complexes and impede plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe, 4, 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silipo, A. , Molinaro, A. , Sturiale, L. , Dow, J.M. , Erbs, G. , Lanzetta, R. , Newman, M.A. , and Parrilli, M. (2005) The elicitation of plant innate immunity by lipooligosaccharide of Xanthomonas campestris . J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33 660–33 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. , Dunning, F.M. , Pfund, C. , Weingarten, R. , Bent, A.F. (2006). Within‐species flagellin polymorphism in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris and its impact on elicitation of Arabidopsis FLAGELLIN‐SENSING2‐dependent defenses. Plant Cell, 18, 764–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepfer, M. and Taylor, I.E.P. (1981) The permeability of plant cell walls as measured by gel filtration chromatography. Science, 213, 761–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilmony, T. , Underwood, W. and He, S.Y. (2006) Genome wide transcriptional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana interaction with the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and the human pathogen Escherichia coli O157:H7. Plant J. 46, 34–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman, W. , De Zabala, M.T. and Grant, M. (2006) Type III effectors orchestrate a complex interplay between transcriptional networks to modify basal defence responses during pathogenesis and resistance. Plant J. 46, 14–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, T. , Zong, N. , Zou, Y. , Wu, Y. , Zhang, J. , Xing, W. , Li, Y. , Tang, X. , Zhu, L. , Chai, J. , Zhou, J.‐M. (2008) Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto blocks innate immunity by targeting receptor kinases. Curr. Biol. 18, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, C. , Robatzel, S. , Navarro, L. , Oakley, E.J. , Jones, J.D. , Felix, G. and Boller, T. (2004) Bacterial disease resistance in Arabidopsis through flagellin perception. Nature, 428, 764–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel, C. , Kunze, G. , Chinchilla, D. , Caniard, A. , Jones, J.D.G. , Boller, T. and Felix, G. (2006) Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF‐Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation. Cell, 125, 749–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]