SUMMARY

Response regulator (RR) proteins are core elements of the high‐osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway, which plays an important role in the adaptation of fungi to a variety of environmental stresses. In this study, we constructed deletion mutants of two putative RR genes, FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2, which are orthologues of Neurospora crassa RRG‐1 and RRG‐2, respectively. The FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant (ΔFgRrg1‐6) showed increased sensitivity to osmotic stress mediated by NaCl, KCl, sorbitol or glucose, and to metal cations Li+, Ca2+ and Mg2+. The mutant, however, was more resistant than the parent isolate to dicarboximide and phenylpyrrole fungicides. Inoculation tests showed that the mutant exhibited decreased virulence on wheat heads. Quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction assays indicated that the expression of FgOS‐2, the putative downstream gene of FgRRG‐1, was decreased significantly in ΔFgRrg1‐6. All of the defects were restored by genetic complementation of ΔFgRrg1‐6 with the wild‐type FgRRG‐1 gene. Different from the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant, FgRRG‐2 deletion mutants were morphologically indistinguishable from the wild‐type progenitor in virulence and in sensitivity to the dicarboximide fungicide iprodione and osmotic stresses. These results indicate that the RR FgRrg‐1 of F. graminearum is involved in the osmotic stress response, pathogenicity and sensitivity to dicarboximide and phenylpyrrole fungicides and metal cations.

INTRODUCTION

The high‐osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway regulates cellular responses to a variety of environmental stresses in eukaryotes (Stock et al., 2000). To date, the HOG pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been well characterized, and consists of a sensor histidine kinase Sln1, a phosphotransfer (HPT) protein Ypd1, two response regulators (RR) Ssk1 and Skn7, and the downstream mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Hohmann, 2002). Under nonosmotic stress conditions, Sln1 is active and phosphoryl groups are shuttled through Ypd1 to Ssk1, therefore maintaining the RR protein in a phosphorylated state (Posas et al., 1996). Under hyperosmotic stress conditions, Sln1 is inactive and the accumulation of unphosphorylated Ssk1 activates downstream MAPK cascades (Ssk2/Ssk22‐Pbs2‐Hog1) by sequential phosphorylation (Krantz et al., 2006; Posas et al., 1996). Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Ssk1 therefore function as an on/off switch in controlling the activity of downstream MAPK cascades (Horie et al., 2008; Posas and Saito, 1998).

Similar to observations in S. cerevisiae, the HOG pathway plays an important role in the process of osmotic adaptation in many filamentous fungi, including Neurospora crassa, Aspergillus nidulans and Fusarium graminearum (Furukawa et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2007; Ochiai et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2002). In the model filamentous fungus N. crassa, components of the HOG pathway include an osmosensor histidine kinase Os‐1, a histidine phosphotransfer protein Hpt‐1, two RRs Rrg‐1 and Rrg‐2, and downstream MAPK cascades Os‐4, Os‐5 and Os‐2, which are homologous to S. cerevisiae Ssk2/Ssk22, Pbs2 and Hog1, respectively (Banno et al., 2007). In contrast with the unique histidine kinase Sln1 in S. cerevisiae, 11 histidine kinases (including Os‐1) have been identified in N. crassa (Catlett et al., 2003). In addition to the response to osmotic stress, the HOG pathway is involved in regulating fungicide resistance, morphogenesis and virulence in filamentous fungi (Rispail et al., 2009).

Fusarium head blight (FHB), caused primarily by F. graminearum, is a devastating disease of cereal crops worldwide (Starkey et al., 2007). Although yield loss caused by the disease is a major concern, mycotoxins produced in infected grains pose a serious threat to human and animal health. One of the recent concerns is whether F. graminearum can adapt to environmental stresses, particularly fungicide applications, and result in a population shift that may lead to more severe diseases and mycotoxin contamination.

A genome‐wide search for the HOG pathway‐related genes in F. graminearum revealed that the fungus possesses many putative HOG elements, including one osmosensor histidine kinase FgOs‐1 and 15 other histidine kinases, one histidine phosphotransfer protein FgHpt‐1, two RRs FgRrg‐1 and FgRrg‐2, and the downstream MAPK cascades (FgOs‐4, FgOs‐5 and FgOs‐2). To date, however, information on the functions of the HOG pathway in F. graminearum is very limited, and the only study was conducted by Ochiai et al. (2007). They found that null mutation of FgOs‐1, FgOs‐2, FgOs‐4 or FgOs‐5 led to increased resistance to iprodione and fludioxonil. As expected, all mutants exhibited increased sensitivity to osmotic stress. Interestingly, the FgOs‐1 deletion mutant produced a reduced level of aurofusarin, and exhibited no change in its ability to produce trichothecenes. In contrast, all other null mutants of FgOs‐2, FgOs‐4 and FgOs‐5 showed markedly enhanced pigmentation and failed to produce trichothecenes in aerial hyphae.

Several previous reports have described that RR proteins in different filamentous fungi show distinct functions. In Cochliobolus heterostrophus, both RR proteins ChSsk1 and ChSkn7 contribute to osmoadaptation and sensitivity to the phenylpyrrole fungicide fludioxonil (Izumitsu et al., 2007). In Candida lusitaniae, Ssk1 is involved in osmotolerance and pseudohyphal development, whereas Skn7 appears to be crucial for oxidative stress adaptation (Ruprich‐Robert et al., 2008). In N. crassa, the RR proteins perform distinct functions. RRG‐1 controls vegetative cell integrity, hyperosmotic sensitivity, fungicide resistance and protoperithecial development (Jones et al., 2007), whereas RRG‐2 participates only in the oxidative stress response (Banno et al., 2007). In the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae, in addition to adaptation to osmotic stress and fludioxonil fungicide, RR proteins are involved in pathogenicity (Motoyama et al., 2008). To date, the functions of RR proteins in F. graminearum remain unidentified.

The key aim of this study was to characterize the functional role of two RR proteins in F. graminearum. Previous reports and our preliminary in silico analysis led us to hypothesize that the RR proteins of the HOG pathway in F. graminearum are involved in the stress response. We were particularly interested in determining how RR proteins mediate fungicide resistance. Here, we tested this hypothesis by generating null mutants of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2, which encode putative RR proteins, by a gene replacement strategy, and applying a variety of stress factors on the mutants.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2

We searched the F. graminearum genome with amino acid sequences of N. crassa RRs Rrg‐1 and Rrg‐2 (Jones et al., 2007) as queries using blastp, and subsequently identified nucleotide sequences of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2. FgRRG‐1, which is 2497 bp in length, is predicted to have two introns, and encodes a 784‐amino‐acid protein. FgRRG‐2 is 2083 bp in length with six introns, and encodes a 587‐amino‐acid protein. The locations of the introns in the FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 genes were verified by sequencing respective 2355‐bp and 1764‐bp cDNAs. We confirmed that both genes were transcribed in F. graminearum mycelium by reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) (data not shown).

Phylogenetic analysis with a neighbour‐joining method using Mega 4.1 software (Kumar et al., 2008) showed that F. graminearum FgRrg‐1 and FgRrg‐2 were homologous to RR proteins in other fungi (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information). The predicted amino acid sequences of FgRrg‐1 and FgRrg‐2 shared 51% and 47% identity with Rrg‐1 (GenBank accession number NCU01895.4) and Rrg‐2 (NCU02413.4) of N. crassa, respectively. The CDART (conserved domain architecture retrieval tool) program (Geer et al., 2002) predicted a conserved RR receiver domain in both FgRrg‐1 and FgRrg‐2 (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information).

Disruption of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 genes in F. graminearum

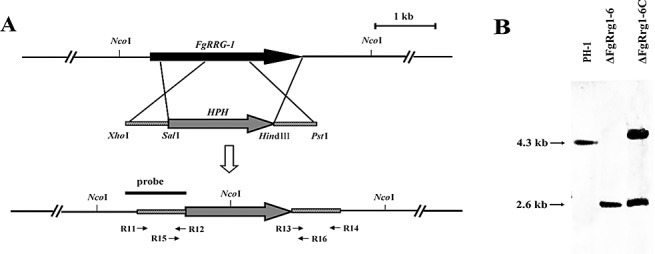

To investigate the function of the two RRs FgRrg‐1 and FgRrg‐2, we generated gene deletion mutants using a homology recombination strategy (Fig. 1A). For FgRRG‐1, eight deletion mutants were identified from 12 hygromycin‐resistant transformants by PCR analysis with the primer pair R15 + R16 (Table 1). The primer pair amplified 1752‐ and 1102‐bp fragments from FgRRG‐1 deletion mutants and the wild‐type progenitor PH‐1, respectively. Both amplicons were detected in ectopic transformants. When probed with a 1008‐bp upstream DNA fragment of FgRRG‐1, the deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 had an anticipated 2.6‐kb band, but lacked a 4.3‐kb band which was present in PH‐1 (Fig. 1B). This Southern hybridization pattern confirmed that the transformant ΔFgRrg1‐6 is a null mutant resulting from a single homologous recombination event at the FgRRG‐1 locus. The complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C harbours a single copy of wild‐type FgRRG‐1 inserted into the genome of the disruption mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the FgRRG‐1 disruption strategy. FgRRG‐1 and the hygromycin resistance cassette (HPH) are denoted by large black and grey arrows, respectively. The annealing sites of primers R11, R12, R13, R14, R15 and R16 are indicated by small black arrows (see Table 1 for the primer sequences). (B) A 1008‐bp upstream fragment of FgRRG‐1 was used as a probe in Southern blot hybridization analysis. Genomic DNA preparations of the wild‐type PH‐1, the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and the complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C were digested with NcoI.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primer code | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)* | Relevant characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Frrg1‐F1 | ATGGAGATGGAGATCGTTCAT | A pair of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for amplification of the full cDNA sequence of the FgRRG‐1 gene |

| 2 | Frrg1‐R1 | TCAGCCAGGCTTGGTCAT | |

| 3 | R11 | ATctcgagTAGTTCTAGCGACCAGCACCA | A pair of PCR primers for amplification of the 661‐bp FgRRG‐1 upstream fragment for construction of the gene deletion vector |

| 4 | R12 | ATgtcgacTATCATATCGCGGACGTCGT | |

| 5 | R13 | ATaagcttGGCTTTCGTTAAGCGCCTTAA | A pair of PCR primers for amplification of the 610‐bp FgRRG‐1 downstream fragment for construction of the gene deletion vector |

| 6 | R14 | ATctgcagTGGTCATGGAAACTCGATTC | |

| 7 | R15 | ACAACCTCCTACATACGCGCC | A pair of PCR primers for identification of FgRRG‐1 deletion mutants |

| 8 | R16 | GGGGAGCTGAATATCCATCAA | |

| 9 | R1‐com‐F | ATggtaccTGGGCGCAAAGTCAGGTT | A pair of PCR primers to amplify the full FgRRG‐1 including 1704‐bp upstream and 472‐bp downstream fragments |

| 10 | R1‐com‐R | ATcccgggTCATGCAGAGATAGCGACCAA | |

| 11 | R1‐probe‐F | ATGGAGATGGAGATCGTTCAT | PCR primers to amplify the 1008‐bp FgRRG‐1 fragment used as the probe for Southern blot analysis |

| 12 | R1‐probe‐R | CGTCGTCAACAAGGTCATCTT | |

| 13 | Frrg2‐F1 | ATGTCTGCCGGAGATGGAA | PCR primers for amplification of full cDNA sequence of the FgRRG‐2 gene |

| 14 | Frrg2‐R1 | CATAGGTACGCTGTCGCTTTT | |

| 15 | R21 | ATctcgagAAAGATGGCGACACCTTTGT | PCR primers to amplify the 644‐bp FgRRG‐2 upstream fragment for construction of the gene deletion vector |

| 16 | R22 | ATgtcgacAATCATCGCTGCCATCTAGAG | |

| 17 | R23 | ATaagcttTAAGCCATTTACCAAGAGCG | PCR primers to amplify the 631‐bp FgRRG‐2 downstream fragment for construction of the deletion vector |

| 18 | R24 | ATggatccTTAAAGGGGTCCGATTCCAA | |

| 19 | R25 | AAACCGTCTCCTTGTTAACGA | PCR primers for identification of FgRRG‐2 deletion transformants |

| 20 | R26 | TGGGAGGGTTCATGTAACCTG | |

| 21 | neo‐F | ATctcgagGGAGGTCAACACATCAATGCT | PCR primers for amplification of neomycin resistance gene |

| 22 | neo‐R | ATggtaccTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAG | |

| 23 | FgOs2‐F | TTGTCAAGTCGCTACCCAAG | PCR primers for amplification of the partial FgOS‐2 gene in quantitative real‐time PCR assays |

| 24 | FgOs2‐R | ATGTATCAACAGGCAGATCGG | |

| 25 | Tri5‐F | TCACCCAGGAAACCCTACACT | PCR primers for amplification of the partial TRI5 gene in quantitative real‐time PCR assays |

| 26 | Tri5‐R | ACGTTTGCCAGTTGTGCAA | |

| 27 | Tri12‐F | TTCCACAGTCATCTTTCCCCA | PCR primers for amplification of the partial TRI12 gene in quantitative real‐time PCR assays |

| 28 | Tri12‐R | TCAAGTACGTCCTTATCCGCT | |

| 29 | actin‐F | ATCCACGTCACCACTTTCAA | PCR primers for amplification of the reference actin gene in quantitative real‐time PCR assays |

| 30 | actin‐R | TGCTTGGAGATCCACATTTG |

The respective restriction enzyme sites included in the primers are listed in lowercase letters in the sequences.

For FgRRG‐2, six deletion mutants were identified from 11 hygromycin‐resistant transformants by PCR analysis (data not shown). Southern analysis of two transformants (ΔFgRrg2‐2 and ΔFgRrg2‐10) further confirmed that FgRRG‐2 was disrupted in these transformants (data not shown).

Morphology of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 deletion mutants

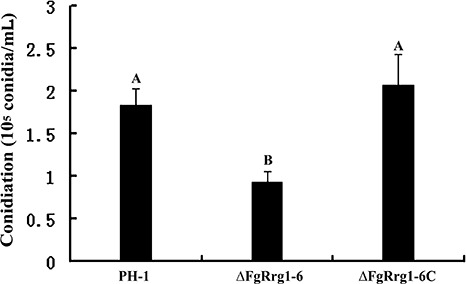

The ΔFgRrg1‐6 strain was not significantly different from the wild‐type progenitor PH‐1 in mycelial growth rate on both potato dextrose agar (PDA) and minimal medium (MM) plates, but showed slightly enhanced pigmentation on PDA (data not shown). The mutant showed a significant decrease in conidiation in mung bean liquid (MBL) medium (Fig. 2), although the conidia of the mutant were morphologically indistinguishable from those of the wild‐type progenitor.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of conidiation in the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C after 4 days of incubation in mung bean liquid medium. Bars with the same letter indicate no significant statistical difference (P < 0.05).

The FgRRG‐2 deletion mutant, ΔFgRrg2‐2, exhibited enhanced pigmentation on PDA. The mutant also showed increased sensitivity to oxidative stress generated by H2O2, but was indistinguishable from PH‐1 with regard to the growth rate under other various stress conditions (Fig. S3, see Supporting Information), sporulation and virulence (data not shown).

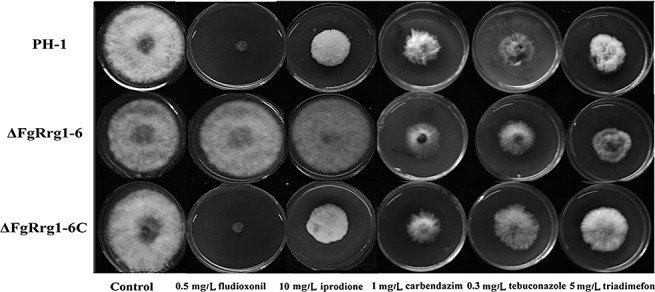

Resistance of the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant to phenylpyrrole and dicarboximide fungicides, and to osmotic and metal cation stresses

As phenylpyrrole and dicarboximide fungicides have been shown to activate the HOG pathway in several fungal pathogens (Kojima et al., 2004), we tested the sensitivity of the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant to the phenylpyrrole fungicide fludioxonil and the dicarboximide fungicide iprodione. As shown in Fig. 3, ΔFgRrg1‐6 was highly resistant to both fungicides and was able to grow very well on PDA amended with 0.5 µg/mL fludioxonil or 10 µg/mL iprodione, whereas the complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C and wild‐type PH‐1 were sensitive to these two fungicides. In addition, we observed that PH‐1 was unable to grow on PDA containing 0.5 µg/mL fludioxonil, but was still able to grow on 10 µg/mL iprodione. This indicates that fludioxonil is more effective than iprodione in suppressing wild‐type F. graminearum. When the fungal strains were tested for their sensitivity to other fungicides, PH‐1, ΔFgRrg1‐6 and ΔFgRrg1‐6C exhibited similar sensitivity to the benzimidazole fungicide carbendazim and the sterol demethylation inhibitors tebuconazole and triadimefon (Fig. 3). The results indicate that ΔFgRrg1‐6 is resistant only to phenylpyrrole and dicarboximide fungicides, but not to other groups of fungicide.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity of the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C to different fungicides. Comparison was made on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates amended with each fungicide at the concentrations indicated in the figure.

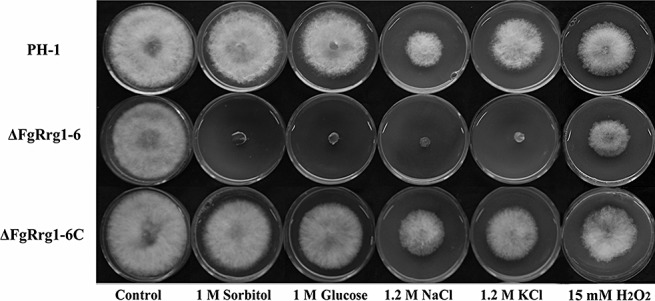

To investigate the role of FgRrg‐1 in osmoadaptation, ΔFgRrg1‐6 and PH‐1 were incubated on PDA amended with 1.2 m NaCl, 1.2 m KCl, 1 m sorbitol or 1 m glucose to generate osmotic stress. As shown in Fig. 4, ΔFgRrg1‐6 was far more sensitive than PH‐1 and ΔFgRrg1‐6C to osmotic stress. Sensitivity to oxidative stress tests showed that, similar to ΔFgRrg2‐2, ΔFgRrg1‐6 exhibited slightly increased sensitivity to oxidative stress generated by 15 mm H2O2 in PDA medium (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity of the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C to osmotic stresses generated by sorbitol, glucose, NaCl and KCl. Comparison was made on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates amended with each osmotic stress agent at the concentration indicated in the figure.

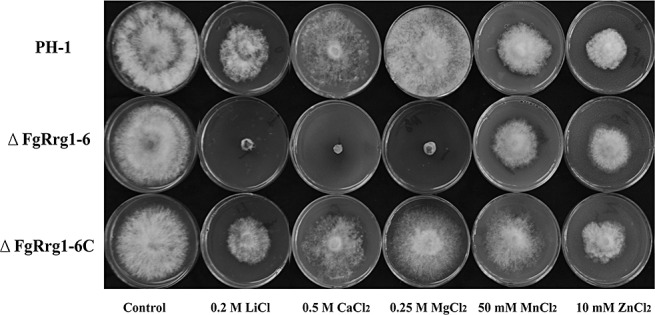

Previous studies have shown that the HOG pathway is involved in the regulation of the sensitivity of the Gram‐negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa to several metal cations, including copper, zinc and cadmium (Caille et al., 2007; Perron et al., 2004), but a similar phenomenon has not been reported in fungi to date. In this study, when we tested the sensitivity of ΔFgRrg1‐6 to metal cations, we were surprised to find that the mutant was much more sensitive than PH‐1 and ΔFgRrg1‐6C to LiCl, CaCl2 and MgCl2, but not to MnCl2 and ZnCl2 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity of the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C to different metal cations. Comparison was made on minimal medium (MM) plates amended with each metal cation at the concentration indicated in the figure.

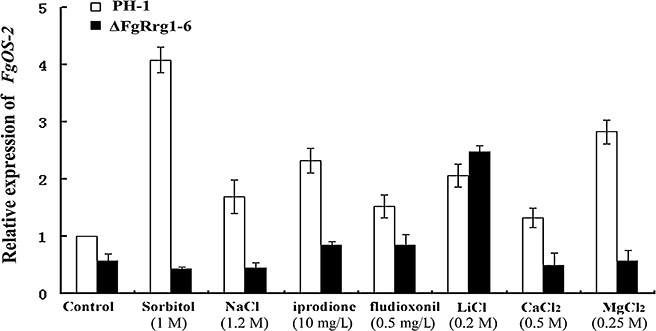

A previous study has shown that the expression of Os‐2, a putative downstream gene of RRG‐1, is up‐regulated by fungicide and osmotic stresses in Botrytis cinerea (Segmüller et al., 2007). Therefore, to verify whether FgRrg‐1 regulates the sensitivity of F. graminearum to osmotic stress and fungicide resistance through an Os‐2 orthologue, we evaluated the expression of FgOS‐2 in ΔFgRrg1‐6 and PH‐1 under various stress conditions. As shown in Fig. 6, in all chemical treatments except 0.2 m LiCl, the expression of FgOS‐2 in PH‐1 was significantly higher than that in ΔFgRrg1‐6, suggesting that FgRrg‐1 plays an important role in the appropriate transcriptional activation of FgOS‐2 in F. graminearum.

Figure 6.

Comparison of FgOS‐2 expression in the wild‐type strain PH‐1 with that in the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 under various stress conditions. The relative expression of FgOS‐2 in PH‐1 or ΔFgRrg1‐6 under fungicide, osmotic or metal cation stress conditions is the relative amount of FgOS‐2 mRNA in PH‐1 without treatment. Bars denote standard errors from three repeated experiments.

Requirement for FgRrg‐1 in full virulence of F. graminearum

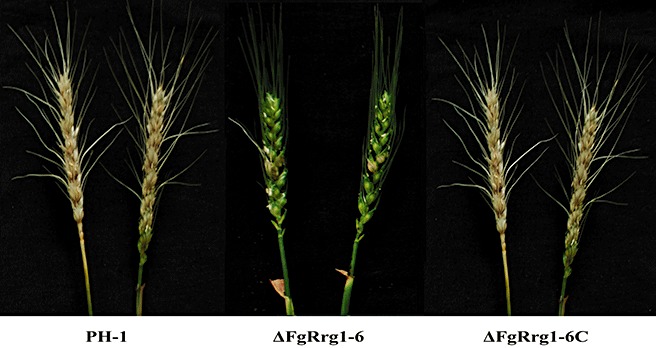

The virulence of ΔFgRrg1‐6 was evaluated by point inoculation of conidial suspension on wheat heads. Twenty days after inoculation with ΔFgRrg1‐6, scab symptoms were observed only in the point‐inoculated spikelets or adjacent one to two spikelets (Fig. 7). Similarly, when point inoculated with mycelia of ΔFgRrg1‐6, scab symptoms were observed in the inoculated or adjacent one to two spikelets (data not shown). Under the same conditions, however, scab symptoms developed in more than 90% of spikelets when wheat heads were point inoculated with the wild‐type PH‐1 or the complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C.

Figure 7.

Virulence of the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C on wheat heads. Wheat heads were point inoculated with a conidial suspension of each strain, and infected wheat heads were examined 20 days after inoculation.

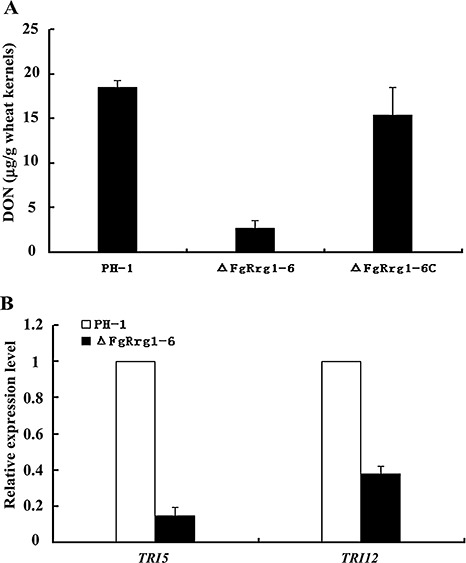

Involvement of FgRrg‐1 in the regulation of deoxynivalenol (DON) biosynthesis and expression of the TRI5 and TRI12 genes

Several studies have shown that DON is an important virulence factor in F. graminearum (Desjardins et al., 1996; Proctor et al., 1995; Seong et al., 2009). Because FgRRG‐1 gene deletion mutants showed reduced virulence, we compared the amount of DON produced by PH‐1 and ΔFgRrg1‐6. As shown in Fig. 8A, the amount of DON produced by ΔFgRrg1‐6 was about six‐ to seven‐fold less than that of the wild‐type progenitor or the complemented strain.

Figure 8.

Deoxynivalenol (DON) production and expression of TRI5 and TRI12. (A) Amount of DON per gram of wheat kernels (µg/g) infected with the wild‐type strain PH‐1, FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 and complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C. (B) Expression levels of TRI5 and TRI12 were measured by quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The relative expression of TRI5 and TRI12 in ΔFgRrg1‐6 is the relative amount of TRI5 and TRI12 mRNA in PH‐1, respectively. Bars denote standard errors from three repeated experiments.

To further confirm the finding that FgRrg‐1 affects DON biosynthesis, we assayed the expression of the trichodiene synthase gene TRI5 by quantitative real‐time PCR. RNA samples were isolated from mycelia grown in GYEP medium (5% glucose, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.1% peptone) for 2 days. The expression level of TRI5 in the mutant ΔFgRrg1‐6 decreased by approximately seven‐fold in comparison with that of PH‐1 or ΔFgRrg1‐6C (Fig. 8B). Similar to TRI5, in ΔFgRrg1‐6, the expression of TRI12, which encodes a trichothecene efflux pump, was significantly lower than that in PH‐1 (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

The ability of fungi to adapt to stress is pivotal to their survival in the environment, and this adaptation ability is one of the key factors leading to population shifts or mutations that can give rise to more aggressive crop pathogens in an agricultural setting. The aim of our investigation was to functionally characterize the role of F. graminearum RR proteins in the stress response and pathogenicity. In this study, we learned that FgRRG‐1 deletion mutants share many phenotypes with FgOS mutants (Ochiai et al., 2007). For example, both FgRRG‐1 and FgOS deletion mutants showed increased sensitivity to osmotic stress generated by NaCl, KCl and sorbitol. FgRRG‐1 mutants were highly resistant to phenylpyrrole and dicarboximide fungicides, a characteristic also associated with FgOS mutants. Our results, combined with a previous report by Ochiai et al. (2007), suggest that the HOG pathway plays an essential role in osmoadaptation in F. graminearum.

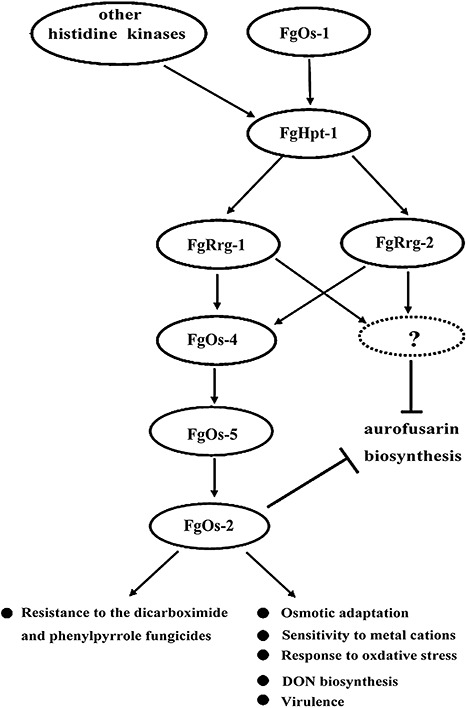

Many fungi have more than one RR protein in the HOG pathway. In N. crassa, Rrg‐1 controls hyperosmotic sensitivity and fungicide resistance (Jones et al., 2007). Unlike Rrg‐1, Rrg‐2 is not involved in osmotic stress and fungicide resistance, but participates in the oxidative stress response (Banno et al., 2007). Similar to RR proteins in N. crassa, Candida lusitaniae Ssk1 is involved in osmotolerance and pseudohyphal development, whereas Skn7 serves a crucial role in oxidative stress adaptation (Ruprich‐Robert et al., 2008). A different scenario can be found in M. oryzae, where there are three RR proteins (MoSsk1, MoSkn7 and MoRim15), but none of the three RR gene disruption mutants exhibit increased sensitivity to oxidative stresses (Motoyama et al., 2008). Our study showed that both FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 F. graminearum mutants are more sensitive to oxidative stresses. A previous study showed that FgOS‐4, FgOS‐5 and FgOS‐2 mutants, but not the FgOS‐1 mutant, exhibited increased sensitivity to H2O2 and tert‐butylhydroperoxide (Ochiai et al., 2007). These results suggest that other histidine kinases, not FgOs‐1, may mediate the oxidative response via downstream RR proteins and MAPKs in F. graminearum (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Proposed functions of the high‐osmolarity glycerol (HOG) pathway in Fusarium graminearum. FgRrg‐2 is only involved in adaptation to oxidative stress, whereas FgRrg‐1 regulates the sensitivity of F. graminearum to fungicide, metal cation, oxidative and osmotic stresses. FgRrg‐1 is also associated with the regulation of deoxynivalenol (DON) production and virulence in F. graminearum. In addition, the HOG pathway may influence aurofusarin production via unidentified inputs.

FgRRG‐1 mutants were more sensitive to LiCl, MgCl2 and CaCl2. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an RR protein being involved in the mediation of sensitivity to metal cations in a filamentous fungus. In P. aeruginosa, the expression of czcR (encoding an RR protein) and czcS sensor (encoding a sensor kinase) was strongly enhanced by zinc treatment, leading to the transcriptional activation of czcCBA, an RND‐type efflux pump for metal cations (Caille et al., 2007; Hassan et al., 1999). In S. cerevisiae, tolerance to high salt is strongly related to the activity of an Na+‐ATPase, Ena1, which pumps out toxic sodium and lithium cations from cells (Garciadeblas et al., 1993; Haro et al., 1991). Under osmotic stress, activated Hog1 prevents the binding of the transcriptional inhibitor Sko1 to the cyclic AMP response element present in the ENA1 promoter, which results in enhanced expression of the ENA1 gene (Proft et al., 2001). Currently, we know little about the relationships between osmotic stress and metal tolerance in F. graminearum, and whether the HOG pathway is associated with this mechanism. Further investigation is needed to determine how the HOG pathway components regulate F. graminearum adaptation to metal cations.

In this study, we found that FgRRG‐1 deletion mutants exhibited reduced virulence on wheat heads. In addition, we found that the FgOS‐2 mutant was compromised in its ability to infect wheat heads (J. Jiang and Z. Ma, unpublished data). These results indicate that the HOG pathway is involved in the pathogenicity of F. graminearum. Similar to F. graminearum, Mycosphaerella graminicola HOG1 (homologous of FgOS‐2) deletion mutants failed to infect wheat leaves (Mehrabi et al., 2006). However, in contrast, HOG1 deletion mutants of the rice pathogens Magnaporthe grisea and Bipolaris oryzae were fully pathogenic (Dixon et al., 1999; Moriwaki et al., 2006), which suggests that the role of the HOG pathway in regulating the virulence of phytopathogenic fungi varies significantly.

DON is an end product of the trichothecene biosynthetic pathway in F. graminearum, and the toxin has been identified as an important virulence factor (Desjardins et al., 1996; Proctor et al., 1995; Seong et al., 2009). When the role of DON in pathogenesis was further investigated, Bai et al. (2002) found that DON production played a significant role in the spread of FHB within a spike, but was not necessary for initial infection by the fungus. In this study, we found that ΔFgRrg1‐6 produced a significantly reduced level of DON. This result is consistent with the observation that ΔFgRrg1‐6 causes scab symptoms only in inoculated or nearby spikelets. In addition, the decrease in DON production in FgRRG‐1 mutants further supports the previous finding that the HOG pathway is involved in the regulation of trichothecene production in F. graminearum (Ochiai et al., 2007).

Accumulating data have shown that the HOG pathway plays an important role in virulence, sexual and asexual development, and adaptation to various environmental stresses, which prompted our further investigation of the HOG pathway in F. graminearum. Comparative analyses have shown that F. graminearum shares many conserved components of the HOG pathway (Fig. 9). As the functional role of the HOG pathway varies significantly among different fungal species, it will be necessary to perform further molecular characterization of other components of the pathway, including FgHpt‐1 and other histidine kinases, in F. graminearum. Detailed information on the HOG pathway in pathogenic fungi will be helpful in developing new antifungal compounds targeting this pathway, as it is absent in mammalian cells (Catlett et al., 2003).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and culture conditions

Fusarium graminearum wild‐type strain PH‐1 and the transformants generated in this study were grown on PDA (200 g potato, 20 g dextrose, 20 g agar and 1 L water) or MM (10 mm K2HPO4, 10 mm KH2PO4, 4 mm (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgSO4, 0.45 mm CaCl2, 9 µm FeSO4, 10 mm glucose and 1 L water, pH 6.9) for mycelial growth tests, and in MBL (40 g mung beans boiled in 1 L water for 20 min and filtered through cheesecloth) medium (Bai and Shaner, 1996) for sporulation analysis.

Sequence analysis of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 genes

FgRrg‐1 (F. graminearum genome accession number FGSG_08948.3) and FgRrg‐2 (FGSG_06359.3) were originally identified through homology searches of the F. graminearum genome sequence (available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/fusarium_group/MultiHome.html) using the blastp algorithm with the RRs RRG‐1 and RRG‐2 from N. crassa (Jones et al., 2007) as queries. To verify the existence and size of the introns in FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2, RNA was extracted from mycelia of the wild‐type PH‐1 using TaKaRa RNAiso Reagent (TaKaRa Biotech. Co., Dalian, China) and employed for RT with a RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas Life Sciences, Burlington, ON, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RT‐PCR of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2 cDNAs was performed using the primer pairs Frrg1‐F1 + Frrg1‐R1 and Frrg2‐F1 + Frrg2‐R1 (Table 1), respectively. PCR amplifications were performed using the following parameters: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 40 s, annealing at 53 °C for 40 s, extension at 72 °C for 2 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The resulting PCR products were purified, cloned and sequenced.

Construction of replacement vectors for deletion of FgRRG‐1 and FgRRG‐2

The FgRRG‐1 gene disruption vector pCA‐FgRrg1‐Del was constructed by inserting two flanking sequences of the FgRRG‐1 gene into two sides of the hph (hygromycin resistance) gene in the pBS‐HPH1 vector (Liu et al., 2007). The upstream flanking sequence fragment of FgRRG‐1 was amplified from PH‐1 genomic DNA using the primers R11 + R12 (Table 1). The 661‐bp fragment was inserted into the XhoI–SalI site of the pBS‐HPH1 vector to generate a plasmid pBS‐FgRrg1‐up. Subsequently, a 610‐bp downstream flanking sequence fragment of FgRRG‐1 was amplified from PH‐1 genomic DNA using the primers R13 + R14 (Table 1) and was inserted into the HindIII–PstI site of the pBS‐FgRrg1‐up vector to generate a plasmid pBS‐FgRrg1‐UD. Finally, the 2775‐bp fragment containing the FgRrg1‐upstream‐hph‐FgRrg1‐downstream cassette (Fig. 1A) was obtained by digestion of plasmid pBS‐FgRrg1‐UD with XhoI and PstI, and ligated into the XhoI–PstI site in pCAMBIA 1300 (CAMBIA, Canberra, Australia). The resulting FgRRG‐1 deletion vector pCA‐FgRrg1‐Del was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 by electroporation. Using the same strategy, a pCA‐FgRrg2‐Del vector was constructed for disruption of the FgRRG‐2 gene.

Transformation of F. graminearum

Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated fungal transformation was performed as described previously (Mullins et al., 2001). Briefly, A. tumefaciens strain C58C1, containing an appropriate binary vector, was grown at 28 °C for 2 days in MM supplemented with kanamycin (100 µg/mL). Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.15 in induction medium (IM) containing 200 µm acetosyringone (AS). The cells were grown for an additional 6 h before mixing with an equal volume of a fresh F. graminearum conidial suspension (1 × 106 conidia/mL). A 200‐µL sample of the mixture was sprayed onto a nylon membrane (3 × 3 cm2) (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA) and plated on IM amended with 200 µm AS. After incubation at 20 °C for 2 days in the dark, the membrane was cut into small pieces (3 × 0.1 cm2) and transferred upside down on PDA plates supplemented with hygromycin B (100 µg/mL), as a selection agent for transformants, and cefotaxime (200 µm), to kill the A. tumefaciens cells. After 5–7 days, hygromycin‐resistant colonies appeared, and individual transformants were transferred onto fresh PDA plates amended with hygromycin B at 100 µg/mL. For conidiation, 10 mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) of each transformant, taken from the periphery of a 3‐day‐old colony, were inoculated into a 50‐mL flask containing 10 mL of MBL medium. The flasks were incubated at 25 °C for 4 days in a shaker (180 rpm). To create monoconidial transformants, a single germinated conidium from each transformant was transferred with a sterile needle to PDA containing hygromycin B (100 µg/mL) in a small Petri dish (60 × 15 mm2) for use in subsequent experiments.

Complementation of the FgRRG‐1 gene deletion mutant

The FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant (ΔFgRrg1‐6) was complemented with the full‐length FgRRG‐1 gene to confirm that the phenotype changes in the FgRRG‐1 deletion mutant were a result of disruption of the gene. The FgRRG‐1 complement plasmid pCA‐FgRrg1‐C was constructed using the backbone of pCAMBIA1300. First, a XhoI–KpnI neo cassette containing a trpC promoter was amplified from plasmid pBS‐RP‐Red‐A8‐NEO (Dong et al., 2009) with primers neo‐F + neo‐R (Table 1), and cloned into the XhoI–KpnI site of pCAMBIA1300 to create plasmid pCA‐neo. Then, a full‐length FgRRG‐1 gene including a 1704‐bp promoter region and a 472‐bp terminator region was amplified from genomic DNA of wild‐type PH‐1 using the primers R1‐com‐F + R1‐com‐R (Table 1), and subsequently cloned into the KpnI and SmaI sites of pCA‐neo to generate the complement plasmid pCA‐FgRrg1‐C. Before plasmid pCA‐FgRrg1‐C was transformed into A. tumefaciens strain C58C1, FgRRG‐1 in this plasmid was sequenced to ensure flawlessness of the sequence. Transformation of ΔFgRrg1‐6 with the full‐length FgRRG‐1 gene was conducted as described above, except that neomycin was used as a selection agent.

Mycelial growth and conidiation assays

Growth tests under different conditions were performed on PDA or MM plates supplemented with the following products: d‐sorbitol (Shangon Co., Shanghai, China), glucose, NaCl, KCl, LiCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, ZnCl2, H2O2, iprodione (96.5% a.i., Heyi Agricultural Chemical Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China), fludioxonil, carbendazim, triadimefon and tebuconazole, at the concentrations indicated in the figures. The fungicides were kindly provided by the Institute of Zhejiang Chemical Industry or the Institute for the Control of Agrochemicals, Ministry of Agriculture (ICAMA), Beijing, China. Each plate was inoculated with a 5‐mm mycelial plug taken from the edge of a 3‐day‐old colony. Plates were incubated at 25 °C for 3 days in the dark, and then the colony diameter in each plate was measured and the original mycelial plug diameter (5 mm) was subtracted from each measurement. The percentage of mycelial radial growth inhibition (RGI) was calculated using the formula RGI =[(C−N)/(C− 5)]× 100, where C is the colony diameter of the control and N is the colony diameter of the treatment. Each experiment was repeated three times.

For conidiation assays, 10 mycelial plugs (5 mm in diameter) of each strain, taken from the periphery of a 3‐day‐old colony, were inoculated in a 50‐mL flask containing 10 mL of MBL medium. The flasks were incubated at 25 °C for 4 days in a shaker (180 rpm). For each strain, the number of conidia in the broth was determined using a haemocytometer. The experiment was repeated three times.

Determination of FgOS‐2 expression

To extract total RNA, mycelia of PH‐1 and ΔFgRrg1‐6 were inoculated into potato dextrose broth and cultured for 2 days at 25 °C in the dark. Before mycelia were harvested for RNA extraction, the culture was treated for 3 h with iprodione, fludioxonil, LiCl, CaCl2, MgCl2, NaCl or sorbitol at the concentrations indicated in Fig. 5. Total RNA was extracted from mycelia of each sample using the TaKaRa RNAiso Reagent, and 10 µg of each RNA sample was used for RT with a RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit employing the oligo(dT)18 primer. Expression of FgOS‐2 was determined by quantitative real‐time PCR with the primer pair FgOs2‐F + FgOs2‐R. RT‐PCR amplifications were performed in a DNA Engine Opticons 4 System (MJ Research, Massachusetts, USA) using SYBR Green I fluorescent dye detection. Amplifications were conducted in a 20‐µL volume containing 10 µL of iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), 1 µL of RT product and 0.5 µL of each primer (Table 1). There were two replicates for each sample. The quantitative real‐time PCR amplifications were performed with the following parameters: an initial preheat at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 20 s and 75 °C for 3 s in order to quantify the fluorescence at a temperature above the denaturation of primer dimers. Once the amplifications were completed, melting curves were obtained to identify the PCR products. For each sample, PCR amplifications with the primer pair actin‐F + actin‐R (Table 1) for the quantification of expression of the actin gene were performed as a reference. The experiment was repeated three times. The expression of FgOS‐2 in the parent isolate and ΔFgRrg1‐6 under fungicide, osmotic and cation stress conditions, relative to that in the parent isolate PH‐1 without treatment, was calculated using the 2−ΔΔ Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Pathogenicity assays on flowering wheat heads

After incubation in MBL medium for 4 days, conidia of each strain were collected by filtration through three layers of gauze and subsequently resuspended in sterile distilled water to a concentration of 1 × 105 conidia/mL. A 10‐µL aliquot of conidial suspension was injected into a floret in the central section spikelet of single flowering wheat heads of susceptible cultivar Zimai12. There were 10 replicates for each strain. After inoculation, the plants were kept at 22 ± 2 °C and 100% humidity for 2 days, and then maintained in a glasshouse. Twenty days after inoculation, the infected spikelets in each inoculated wheat head were recorded. The experiment was repeated four times. Using a similar method, mycelia of each strain were also used for inoculation tests.

Analysis of DON production and expression level of TRI5 and TRI12

A 30‐g aliquot of healthy wheat kernels was sterilized and inoculated with 1 mL of spore suspension (106 spores/mL) of the wild‐type strain PH‐1, the complemented strain ΔFgRrg1‐6C or ΔFgRrg1‐6. After incubation at 25 °C for 20 days, DON was extracted using a previously described protocol (Mirocha et al., 1998). The extracts were purified with PuriToxSR DON column TC‐T200 (Trilogy Analytical Laboratory, Missouri, USA), and the amount of DON in each sample was determined using a Waters 1525 (Massachusetts, USA) high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. The experiment was repeated three times, and data were analysed using analysis of variance (SAS version 8.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

To determine the expression levels of TIR5 and TRI12, mycelia of the parental strain PH‐1 and ΔFgRrg1‐6 were inoculated into GYEP medium (5% glucose, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.1% peptone) and cultured for 2 days at 25 °C in the dark. Total RNA was extracted from the mycelia of each sample using TaKaRa RNAiso Reagent, and 10 µg of each RNA sample was used for RT with a RevertAid H Minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit employing the oligo(dT)18 primer. The expression of TRI5 and TRI12 was determined using a quantitative real‐time PCR method as described above. The experiment was repeated three times.

Standard molecular methods

Fungal genomic DNA was isolated as described by McDonald and Martinez (1990). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a Plasmid Miniprep Purification Kit (BioDev Co., Beijing, China). Southern analysis of FgRRG‐1 in F. graminearum was performed using the 1008‐bp FgRRG‐1 upstream fragment as a probe, which was amplified by the primer pair R1‐probe‐F + R1‐probe‐R (Table 1). The probe was labelled with digoxigenin (DIG) using a High Prime DNA Labelling and Detection Starter Kit II according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). DNA extracted from F. graminearum was digested with NcoI and used for Southern hybridization analysis.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequences of the putative response regulators from Aspergillus nidulans (A. nid SskA and A. nid SrrA), Fusarium graminearum (F. gra Rrg1 and F. gra Rrg2), Neurospora crassa (N. cra Rrg1 and N. cra Rrg2) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cer Ssk1 and S. cer Skn7). The tree shown was obtained by a neighbour‐joining method using Mega 4.1 software.

Fig. S2 Alignments of (A) Rrg‐1 and (B) Rrg‐2 from F. graminearum (F. gra) with the related response regulators from other fungi, including Aspergillus nidulans (A. nid), Neurospora crassa (N. cra) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cer). Boxshade program was used to highlight identical (black shading) or similar (grey shading) amino acids. The receiver domain is underlined.

Fig. S3 Sensitivity of the wild‐type strain PH‐1 and FgRRG‐2 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg2‐2 to different stresses. Comparison was made on PDA or MM plates amended with each compound at the concentration described in the figure.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a fund from the Modern Agro‐Industry Technology Research System, the Special Program for Agricultural Research (nyhyzx07‐048) and the National Science Foundation (30971933).

REFERENCES

- Bai, G.H. and Shaner, G. (1996) Variation in Fusarium graminearum and cultivar resistance to wheat scab. Plant Dis. 80, 975–979. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, G.H. , Desjardins, A.E. and Plattner, R.D. (2002) Deoxynivalenol nonproducing Fusarium graminearum causes initial infection, but does not cause disease spread in wheat spikes. Mycopathologia, 153, 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banno, S. , Noguchi, R. , Yamashita, K. , Fukumori, F. , Kimura, M. , Yamaguchi, I. and Fujimura, M. (2007) Roles of putative His‐to‐Asp signaling modules HPT‐1 and RRG‐2, on viability and sensitivity to osmotic and oxidative stresses in Neurospora crassa . Curr. Genet. 51, 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille, O. , Rossier, C. and Perron, K. (2007) A copper‐activated two‐component system interacts with zinc and imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Bacteriol. 13, 4561–4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlett, N.L. , Yoder, O.C. and Turgeon, B.G. (2003) Whole‐genome analysis of two component signal transduction genes in fungal pathogens. Eukaryot. Cell, 6, 1151–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, A.E. , Proctor, R.H. , Bai, G. , McCormick, S.P. , Shaner, G. , Buechley, G. and Hohn, T.M. (1996) Reduced virulence of trichothecene‐nonproducing mutants of Gebberella zeae in wheat field tests. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 9, 775–781. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, K.P. , Xu, J.R. , Smirnoff, N. and Talbot, N.J. (1999) Independent signaling pathways regulate cellular turgor during hyperosmotic stress and appressorium‐mediated plant infection by Magnaporthe grisea . Plant Cell, 11, 2045–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B. , Liu, X.H. , Lu, J.P. , Zhang, F.S. , Gao, H.M. , Wang, H.K. and Lin, F.C. (2009) MgAtg9 trafficking in Magnaporthe oryzae . Autophagy, 5, 946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, K. , Hoshi, Y. , Maeda, T. , Nakajima, T. and Abe, K. (2005) Aspergillus nidulans HOG pathway is activated only by two‐component signaling pathway in response to osmotic stress. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1246–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garciadeblas, B. , Rubio, F. , Quintero, F.J. , Banuelos, M.A. , Haro, R. and Rodriguez‐Navarro, A. (1993) Differential expression of two genes encoding isoforms of the ATPase involved in sodium efflux in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol. Gen. Genet. 236, 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geer, L.Y. , Domrachev, M. , Lipman, D.J. and Bryant, S.H. (2002) CDART: protein homology by domain architecture. Genome Res. 12, 1619–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro, R. , Garciadeblas, B. and Rodriguez‐Navarro, A. (1991) A novel P‐type ATPase from yeast involved in sodium transport. FEBS Lett. 291, 189–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.T. , Van der Lelie, D. , Springael, D. , Romling, U. , Ahmed, N. and Mergeay, M. (1999) Identification of a gene cluster, czr, involved in cadmium and zinc resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Gene, 238, 417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann, S. (2002) Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 300–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie, T. , Tatebayashi, K. , Yamada, R. and Saito, H. (2008) Phosphorylated Ssk1 prevents unphosphorylated Ssk1 from activating the Ssk2 MAP kinase kinase kinase in the yeast HOG osmoregulatory pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 5172–5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumitsu, K. , Yoshimi, A. and Tanaka, C. (2007) Two‐component response regulators Ssk1p and Skn7p additively regulate high‐osmolarity adaptation and fungicide sensitivity in Cochliobolus heterostrophus . Eukaryot. Cell, 6, 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.A. , Greer‐Phillips, S.E. and Borkovich, K.A. (2007) The response regulator RRG‐1 functions upstream of a mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway impacting asexual development, female fertility, osmotic stress, and fungicide resistance in Neurospora crassa . Mol. Biol. Cell, 18, 2123–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, K. , Takano, Y. , Yoshimi, A. , Tanaka, C. , Kikuchi, T. and Okuno, T. (2004) Fungicide activity through activation of a fungal signaling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1785–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz, M. , Becit, E. and Hohmann, S. (2006) Comparative analysis of HOG pathway proteins to generate hypotheses for functional analysis. Curr. Genet. 49, 152–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. , Nei, M. , Dudley, J. and Tamura, K. (2008) MEGA: a biologist‐centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 9, 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.H. , Lu, J.P. , Zhang, L. , Dong, B. , Min, H. and Lin, F.C. (2007) Involvement of a Magnaporthe grisea serine/threonine kinase gene, MgATG1, in appressorium turgor and pathogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell, 6, 977–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J. and Schmittgen, T.D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real‐time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCt method. Methods, 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B.A. and Martinez, J.P. (1990) Restriction fragment length polymorphisms in Septoria tritici occur at high frequency. Curr. Genet. 17, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, R. , Zwiers, L.H. , de Waard, M.A. and Kema, G.H.J. (2006) MgHog1 regulates dimorphism and pathogenicity in the fungal wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1262–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirocha, C.J. , Kolaczkowski, E. , Xie, W.P. , Yu, H. and Jelen, H. (1998) Analysis of deoxynivalenol and its derivatives (batch and single kernel) using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki, A. , Kubo, E. , Arase, S. and Kihara, J. (2006) Disruption of SRM1, a mitogen‐activated protein kinase gene, affects sensitivity to osmotic and ultraviolet stressors in the phytopathogenic fungus Bipolaris oryzae . FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 257, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama, T. , Ochiai, N. , Morita, M. , Iida, Y. , Usami, R. and Kudo, T. (2008) Involvement of putative response regulator genes of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae in osmotic stress response, fungicide action, and pathogenicity. Curr. Genet. 54, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, E.D. , Chen, X. , Romaine, P. , Raina, R. , Geiser, D.M. and Kang, S. (2001) Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of Fusarium oxysporum: an efficient tool for insertional mutagenesis and gene transfer. Phytopathology, 91, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, N. , Tokai, T. , Nishiuchi, T. , Takahashi‐Ando, N. , Fujimura, M. and Kimura, M. (2007) Involvement of the osmosensor histidine kinase and osmotic stress‐activated protein kinases in the regulation of secondary metabolism in Fusarium graminearum . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron, K. , Caille, O. , Rossier, C. , Van Delden, C. , Dumas, J. and Köhler, T. (2004) CzcR‐CzcS, a two‐component system involved in heavy metal and carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8761–8768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas, F. and Saito, H. (1998) Activation of the yeast SSK2 MAP kinase kinase kinase by the SSK1 two‐component response regulator. EMBO J. 17, 1385–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posas, F. , Wurgler‐Murphy, S.M. , Maeda, T. , Witten, E.A. , Thai, T.C. and Saito, H. (1996) Yeast HOG1 MAP kinase cascade is regulated by a multistep phosphorelay mechanism in the SLN1‐YPD1‐SSK1 ‘two‐component’ osmosensor. Cell, 86, 865–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, R.H. , Hohn, T.M. and McCormick, S.P. (1995) Reduced virulence of Geibberella zeae caused by disruption of a trichothecene toxin biosynthesis gene. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 8, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft, M. , Pascual‐Ahuir, A. , de Nadal, E. , Arino, J. , Serrano, R. and Posas, F. (2001) Regulation of the Sko1 transcriptional repressor by the Hog1 MAP kinase in response to osmotic stress. EMBO J. 20, 1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispail, N. , Soanes, D.M. , Ant, C. , Czajkowski, R. , Grünler, A. , Huguet, R. , Perez‐Nadales, E. , Poli, A. , Sartorel, E. , Valiante, V. , Yang, M. , Beffa, R. , Brakhage, A.A. , Gow, N.A.R. , Kahmann, R. , Lebrun, M. , Lenasi, H. , Perez‐Martin, J. , Talbot, N. , Wendland, J. and Pietro, A. (2009) Comparative genomics of MAP kinase and calcium–calcineurin signaling components in plant and human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46, 287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruprich‐Robert, G. , Chapeland‐Leclerc, F. , Boisnard, S. , Florent, M. , Bories, G. and Papon, N. (2008) Contributions of the response regulators Ssk1p and Skn7p in the pseudohyphal development, stress adaptation, and drug sensitivity of the opportunistic yeast Candida lusitaniae . Eukaryot. Cell, 7, 1071–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segmüller, N. , Ellendorf, U. , Tudzynski, B. and Tudzynski, P. (2007) BcSAK1, a stress‐activated mitogen‐activated protein kinase, is involved in vegetative differentiation and pathogenicity in Botrytis cinerea . Eukaryot. Cell, 6, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong, K.Y. , Pasquali, M. , Zhou, X.Y. , Song, J. , Hilburn, K. , McCormick, S. , Dong, Y. , Xu, J.R. and Kistler, H.C. (2009) Global gene regulation by Fusarium transcription factors Tri6 and Tri10 reveals adaptations for toxin biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 354–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, D.E. , Ward, T.J. , Aoki, T. , Gale, L.R. , Kistler, H.C. , Geiser, D.M. , Suga, H. , Tóth, B. , Varga, J. and O'Donnel, K. (2007) Global molecular surveillance reveals novel Fusarium head blight species and trichothecene toxin diversity. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 1191–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock, A.M. , Robinson, V.L. and Goudreau, P.N. (2000) Two component signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 183–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Lamm, R. , Pillonel, C. , Lam, S. and Xu, J.R. (2002) Osmoregulation and fungicide resistance: the Neurospora crassa os‐2 gene encodes a HOG1 mitogen‐activated protein kinase homologue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 532–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequences of the putative response regulators from Aspergillus nidulans (A. nid SskA and A. nid SrrA), Fusarium graminearum (F. gra Rrg1 and F. gra Rrg2), Neurospora crassa (N. cra Rrg1 and N. cra Rrg2) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cer Ssk1 and S. cer Skn7). The tree shown was obtained by a neighbour‐joining method using Mega 4.1 software.

Fig. S2 Alignments of (A) Rrg‐1 and (B) Rrg‐2 from F. graminearum (F. gra) with the related response regulators from other fungi, including Aspergillus nidulans (A. nid), Neurospora crassa (N. cra) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cer). Boxshade program was used to highlight identical (black shading) or similar (grey shading) amino acids. The receiver domain is underlined.

Fig. S3 Sensitivity of the wild‐type strain PH‐1 and FgRRG‐2 deletion mutant ΔFgRrg2‐2 to different stresses. Comparison was made on PDA or MM plates amended with each compound at the concentration described in the figure.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Supporting info item