SUMMARY

One reason for the success of Pseudomonas syringae as a model pathogen has been the availability of three complete genome sequences since 2005. Now, at the beginning of 2011, more than 25 strains of P. syringae have been sequenced and many more will soon be released. To date, published analyses of P. syringae have been largely descriptive, focusing on catalogues of genetic differences among strains and between species. Numerous powerful statistical tools are now available that have yet to be applied to P. syringae genomic data for robust and quantitative reconstruction of evolutionary events. The aim of this review is to provide a snapshot of the current status of P. syringae genome sequence data resources, including very recent and unpublished studies, and thereby demonstrate the richness of resources available for this species. Furthermore, certain specific opportunities and challenges in making the best use of these data resources are highlighted.

INTRODUCTION—PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE

Pseudomonas syringae is a Gram‐negative bacterial pathogen that causes leaf spot, stem canker and other symptoms on a wide range of uncultivated plants and important crops, including bean, tobacco and tomato. However, P. syringae is most notable as arguably the most well‐studied species of plant‐pathogenic bacterium. Equally, it is an excellent tool for the dissection of the multiple layers of immunity in the plant host (Gimenez‐Ibanez and Rathjen, 2010).

The species P. syringae is subdivided into about 50 pathogen varieties (‘pathovars’), each defined primarily by its host range (Dye et al., 1980; reviewed by Hirano and Upper, 2000). The types of disease symptoms that develop depend on the combination of bacterial strain and the host species or cultivar. Prominent among the bacterial host range determinants is the type III secretion system (T3SS) and its substrates, the T3SS effector proteins. These are pivotal in the pathogen's avoidance and suppression of host defences (Cunnac et al., 2009; Lindeberg et al., 2006; Mansfield, 2009).

One reason for the success of P. syringae as a model pathogen has been the availability of a complete genome sequence for one strain since 2003 and two further genome strains since 2005. Now, at the beginning of 2011, more than 25 strains of P. syringae have been sequenced, at least to draft quality, and many more will be released into the public domain this year (O'Brien et al., 2011). This offers unprecedented opportunities to study the mechanisms and evolution of pathogenicity in this species. Indeed, comparative analysis of these genome sequences has already yielded exciting insights into the evolution of T3SS and its associated complement of effectors, other virulence factors and adaptations to colonizing woody hosts (reviewed in O'Brien et al., 2011). However, we have so far barely scratched the surface; there remain enormous opportunities and challenges to fully exploit even the existing data. To date, published analyses of P. syringae have been largely descriptive, focusing on catalogues of genetic differences among strains and between species. Numerous powerful statistical tools are now available that have yet to be applied to P. syringae genomic data for robust and quantitative reconstruction of evolutionary events. Equally important is that all the currently published studies are based on analyses of single P. syringae isolates. Going forward, it is essential to consider genetic variation within populations. Furthermore, by combining genomic data with phenotypic and precise geographical and temporal metadata, there are huge opportunities in the field of phylogeography for this species.

The aim of this review is to provide a snapshot of the current status of P. syringae genome sequence data resources, including very recent and unpublished studies, and thereby demonstrate the richness of resources available for this species. Furthermore, certain specific opportunities and challenges in making the best use of these data resources are highlighted.

THE VALUE OF THE COMPLETE GENOME SEQUENCE

Complete genome sequences represent an invaluable resource for the study of bacterial pathogens. They provide documentation, albeit incomplete, of the organism's evolutionary history (reviewed in Boussau and Daubin, 2010; Falush, 2009; Raskin et al., 2006; Rocha, 2008). Bacterial genomes are the product of two main evolutionary drivers: recombination and accumulation of point mutations. Point mutations, i.e. single‐nucleotide polymorphisms, and short insertions and deletions, are inherited vertically and may be adaptive, deleterious or neutral with respect to fitness. Recombination with foreign DNA is the basis for horizontal genetic transfer, which is the bacterial equivalent of sexual reproduction, but recombination can also occur within a single genome leading to intragenome rearrangements and deletions. The relative contributions of recombination and point mutation vary enormously among different bacterial lineages. Consequently, a bacterial genome comprises both a core component, which is inherited largely clonally, and an ‘accessory’ or ‘dispensable’ component, which is largely shaped by recombination with individuals of the same or other bacterial species (Medini et al., 2005).

The sequencing of complete genomes may also reveal cryptic genetic variations that are hidden in apparently monomorphic populations in which multilocus sequence typing is uninformative (Holt et al., 2008). Genetic variants discovered from genome sequencing can then be exploited as discriminatory markers for diagnostics, epidemiology and phylogenetic studies (reviewed in Baker et al., 2010). Genomes may also encode multiple interesting and important products, such as T3SS virulence factors, that are obscured by functional redundancy. Furthermore, some organisms (e.g. fastidious xylem‐limited plant pathogens) are not amenable to traditional genetic methods, and therefore genome sequencing provides a pragmatic solution to obtain an overall picture of their biology or, at least, to generate testable hypotheses (reviewed in Van Sluys et al., 2002).

PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE ENTERS THE GENOMICS AGE

The sequence of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato (Pto) DC3000 (Buell et al., 2003) revealed numerous new potential virulence factors, as well as unexpectedly large repertoires of transporters for sugars and other nutrients (Buell et al., 2003). However, the real power of genomics comes from the comparative approach (Lindeberg et al., 2008). Complete genome sequences have become available for two further strains of P. syringae, representing pathovars syringae (Psy) and phaseolicola (Pph) (Feil et al., 2005; Joardar et al., 2005). All three sequenced strains are physiologically very similar and are readily distinguishable only by their interactions with plants. The core set of genomic components conserved in all three genomes is probably responsible for the species‐wide traits; genomic regions that vary between different pathovars presumably contribute to the observed phenotypic differences, such as mode of dispersal, host specificity and propensity for epiphytic survival. Comparisons of these three genome sequences (Buell et al., 2003; Feil et al., 2005; Joardar et al., 2005; Lindeberg et al., 2008; Sarris et al., 2010) revealed pathovar‐specific genes encoding secretion systems, secreted effectors, the biosynthesis of phytotoxins, amino acid degradation and ice nucleation. Differences in the repertoire of signal transduction systems (Lavín et al., 2007) suggest that not only the parts list, but also the ‘wiring diagram’ of the cells, varies between the pathovars. This highlights the importance of studying not just the genome, but also the dynamics of the transcriptome (Filiatrault et al., 2010).

The three strains for which finished genome sequences are available (Pto DC3000, Psy B728a and Pph 1448A) are phylogenetically distant from each other, representing clades 1, 2 and 3, respectively (see positions of filled arrows in Fig. 1). Comparisons among these three genomes revealed that 35% or more of their genomes are composed of accessory components that are not conserved over all three strains. Notwithstanding their enormous contribution to progress towards an understanding of the biology of P. syringae, comparisons between the genome sequences of these three strains tell us little about the microevolutionary processes within each of these three clades, nor within clades 4 and 5. Many questions remain unanswered. To what extent have recombination and clonal evolution shaped the genomes of individual strains and pathovars within the major clades? To what extent are host‐specific pathovars sexually isolated from each other? How much genetic variation is there within a pathovar, within a single multilocus sequence type? Have all pathovars and lineages undergone similar evolutionary processes or are they on completely separate evolutionary trajectories? As a consequence of recent improvements in DNA sequencing technology, the resolution of such questions is becoming tractable. For many human‐pathogenic bacteria, similar questions are being tackled through sequencing and statistical analysis of large numbers of isolates of a single species. For example, Croucher et al. (2011) recently sequenced 240 isolates of a single strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. This enabled a comprehensive survey of how recombination, point mutation and other genetic processes have contributed to its diversification and adaptation to antibiotic use over recent decades. It will not be long before phytopathogen genomics catches up and P. syringae appears to be leading the way.

Figure 1.

Major clades within the species Pseudomonas syringae revealed by multilocus sequence analysis. The neighbour‐joining tree is based on concatenated sequences of seven genes: acn, cts, gapA, gyrB, pfk, pgi, rpoD. Sequence data were extracted from the genome sequences listed in Table 1 and from Sarkar and Guttman (2004). The tree was generated using Quicktree (Howe et al., 2002) and ATV (Zmasek and Eddy, 2001). Filled arrows indicate strains from which complete finished genome sequences are available. Open arrows indicate strains for which draft‐quality genome‐wide sequence data are available.

SEQUENCING P. SYRINGAE GENOMES: THE NEXT GENERATION

Until around the year 2006, the ability to determine an organism's complete genome sequence was largely the preserve of specialized centres, such as the Joint Genome Institute (JGI) and The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR), who sequenced Pto DC3000, Psy B728a and Pph 1448A. The availability of a new generation of technologies has placed genome sequencing within the reach of small research institutes and university departments. As a result, rather than being a distinct scientific discipline, genomics is increasingly becoming a routine tool used in individual laboratories to address specific scientific questions. Genome‐wide sequence data are now publicly available for at least 26 strains of P. syringae (Table 1). In fact, a couple of strains have been sequenced independently by different research groups.

Table 1.

Currently available full genome sequence datasets for Pseudomonas syringae.

| Pathovar and strain | GenBank accession | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pv. aceris M302273PT | AEAO00000000 | * |

| pv. actinidiae M302091 | AEAL00000000 | * |

| pv. aesculi 0893_23**** | AEAD00000000 | * |

| pv. aesculi 2250 | ACXT00000000 | Green et al. (2010) |

| pv. aesculi NCPPB 3681**** | ACXS00000000 | Green et al. (2010) |

| pv. aptata DSM 50252 | AEAN00000000 | * |

| pv. glycinea race 4 | ADWY00000000 | * |

| pv. glycinea race 4 | AEGH00000000 | Qi et al. (2011) |

| pv. glycinea B076 | AEGG00000000 | Qi et al. (2011) |

| pv. japonica M301072PT | AEAH00000000 | * |

| pv. lachrymans M301315 | AEAF00000000 | * |

| pv. lachrymans M302278PT | AEAM00000000 | * |

| pv. maculicola ES4326 | AEAK00000000 | * |

| pv. mori 301020 | AEAG00000000 | * |

| pv. morsprunorum M302280PT | AEAE00000000 | * |

| pv. oryzae 1_6 | ABZR00000000 | Reinhardt |

| pv. phaseolicola 1448A | CP000058 | Joardar et al. (2005) |

| pv. pisi 1704B | AEAI00000000 | * |

| pv. savastanoi NCPPB 3335 | ADMI00000000 | Rodríguez‐Palenzuela et al. (2010) |

| pv. syringae 642 | ADGB00000000 | Clarke et al. (2010) |

| pv. syringae B728a | CP000075 | Feil et al. (2005) |

| pv. syringae FF5 | ACXZ00000000 | ** |

| pv. tabaci ATCC 11528 | ACHU00000000 | Studholme et al. (2009) |

| pv. tomato DC3000 | AE016853 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| pv. tomato K40 | ADFY00000000 | *** |

| pv. tomato Max13 | ADFZ00000000 | *** |

| pv. tomato NCPPB 1108 | ADGA00000000 | *** |

| pv. tomato T1 | ABSM01000115 | Almeida et al. (2009) |

D.A. Baltrus (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA), M.T. Nishimura, A. Romanchuk, J.H. Chang, K. Cherkis, C.D. Jones & J.L. Dangl, unpublished data.

K.H. Sohn, J.D.G. Jones & D.J. Studholme, unpublished data.

B.A. Vinatzer (Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA), S. Yan & J. Lewis, unpublished data.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi strains NCPPB3681 and 0893_23 are both derived from the pathotype strain isolated by Durgapal (1971).

The first team to apply these second‐generation sequencing methods to a plant pathogen was based at the University of North Carolina (Reinhardt et al., 2009). They used a combination of Roche's 454 GS20 and Illumina's Solexa technologies to generate a draft‐quality genome sequence for P. syringae pathovar oryzae (Por) strain I‐6, isolated in Hokkaido, Japan, and causing halo blight on rice. This strain is the sole representative of clade 4 for which genome‐wide sequence data are available. The Por I‐6 genome assembly is not closed into a single chromosome sequence; the strain I‐6 assembly instead consists of 130 supercontig scaffolds. Nevertheless, the assembly is sufficiently contiguous to be useful and will probably provide clues and generate hypotheses about the evolution and mechanisms of pathogenesis on a monocotyledonous host. However, no report has yet been published describing the biological insights from this genome sequence.

THE EXPANDED PAN‐GENOME OF P. SYRINGAE CLADE 3

Clade 3 is the phylogenetic group for which the most extensive genome sequence data are currently available; these data have revealed a substantial number of novel genes within the clade's pan‐genome, including many with possible functional significance for interactions with plants or other eukaryotes.

After establishing the feasibility and validity of this approach using the previously sequenced Psy strain B728a (Farrer et al., 2009), we generated a draft genome sequence for P. syringae pathovar tabaci (Pta) strain 11528 (Studholme et al., 2009) based solely on Illumina's Solexa platform. The motivation for sequencing this strain was that it naturally infects wild tobacco, Nicotiana benthamiana. The N. benthamiana–Pta pathosystem has some advantages over Arabidopsis thaliana–Pto as a model system, N. benthamiana having conveniently large leaves and being amenable to virus‐induced gene silencing.

The unfinished draft‐quality genome assembly of Pta 11528 proved to be useful, providing an inventory of virulence factors, including genes encoding effectors delivered by the T3SS. It revealed a previously unknown T3SS effector distantly related to AvrPto1, and numerous strain‐specific genomic regions, including an island sharing extensive similarity to the 106‐kb mobile genomic island previously described in Pph 1302A (Pitman et al., 2005). However, many genes were interrupted by gaps or ambiguities in the draft assembly. We have subsequently generated genome‐wide sequence data using the 454 GS‐FLX platform for Pta 11528 and are using this to refine the Illumina‐based assembly (D.J. Studholme, D. Heavens, H. Chapman & J. Rathjen, unpublished data). As well as providing a high‐quality genome sequence for this important model pathogen, this will reveal specific strengths and weaknesses of the two sequencing platforms with respect to P. syringae genomes.

Genome‐wide sequencing has revealed extensive differences between Pta 11528 and Pph 1448A, the most closely related of the previously sequenced strains. Approximately 88% of the Pta 11528 genome is clearly homologous with that of Pph 1448A. Over this conserved core, the nucleotide sequences of Pta 11528 and Pph 1448A share 98.3% identity. However, the remaining 12% of the Pta genome and 13% of the Pph 1448A genome share no detectable similarity at the nucleotide sequence level. This variable accessory compartment of the clade 3 genomes includes many genes implicated in virulence and/or epiphytic fitness, including several encoding T3SS effectors, enzymes, chemotaxis proteins and type IV pili. A full list of more than 300 predicted genes uniquely found in Pta 11528 is provided in the supplementary information in Studholme et al. (2009).

In addition to Pta 11528, another Pta strain, 6605, is commonly used in the laboratory, especially for studies on the glycosylation of the P. syringae flagellum (Taguchi et al., 2006). We have recently generated a draft genome sequence for strain 6605 (D.J. Studholme, D. Heavens, H. Chapman & J. Rathjen, unpublished data). The relationship between these two Pta strains is unclear. Multilocus sequence analysis, based on seven housekeeping genes, suggested that Pta 11528 is quite divergent from Pta 6605, implying that the tabaci pathovar does not comprise a monophyletic clade (see Fig. 1). Paradoxically, over their core genomes, the two Pta strains are nearly identical (99.3%), suggesting a very close relationship; to put this into perspective, the relationship between Pta 11528 and Pta 6605 is presumably much closer than that between Pta 11528 and Pph 1448A, whose core genomes share only 98.3% identity. The explanation for this incongruence is a recent recombination event in the Pta 11528 lineage involving the gyrase B (gyrB) gene. In support of this hypothesis, the other six housekeeping gene sequences consistently indicate a close relationship between Pta and P. syringae pv. lachrymans M3013151; however, gyrB from Pta 11528 more closely resembles that of P. savastanoi pv. savastanoi NCPPB 3335.

This horizontal acquisition of gyrB by the Pta 11528 lineage from another clade 3 strain teaches an important lesson. Despite being the most widely used intraspecific phylogenetic marker, gyrB is not necessarily a reliable phylogenetic indicator for the core genome. This point was further underscored by Sarkar and Guttman (2004), who found evidence of recombination in the gyrB gene between members of clades 2a and 3. Clearly, it is unsafe to infer an organism's evolutionary history from a single locus, or even just a few loci. The availability of the entire core genome sequence provides a much more robust basis for such inference.

Our results indicate that the two sequenced Pta strains comprise a monophyletic clade. Consistent with their close phylogenetic affinity, Pta strains 11528 and 6605 share the same repertoire of genes encoding T3SS effectors and, in most cases, their sequences are identical across the two strains. Exceptions include hopAE1 and hopV1, which contain several single‐nucleotide polymorphisms. We have not yet analysed these single‐nucleotide polymorphism frequencies against probabilistic models to determine whether they are best explained by recombination or the accumulation of point mutations. In addition, it is not yet clear whether these variations have adaptive significance. However, the availability of two Pta genome sequences offers the opportunity to examine intrapathovar variation and has practical utility for those working with these strains in the laboratory.

Despite the close phylogenetic affinity of the Pta strains, complete genome sequencing revealed some cryptic variation that would otherwise have been invisible. About 8% of their genomes showed no detectable nucleotide sequence similarity between strains 6605 and 11528. Most of the strain‐specific genomic regions in either genome contained genes showing closest sequence similarity to phage and were enriched in genes of unknown function. This suggests that phage activity accounts for much of the variation in the accessory genome within Pta.

Our knowledge of the pan‐genome of clade 3 increased further with the sequencing of four isolates of P. syringae pv. aesculi (Pae). Furthermore, this study was the first to compare multiple genome sequences from within a single pathovar (Green et al., 2010). The type strain of this pathovar was isolated in India in 1969 (Durgapal, 1971), where it causes a mild leaf‐spot disease on the Indian chestnut tree (Aesculus indica). Recently, Pae was identified (Schmidt et al., 2008) as the causal agent of an emerging epidemic of bleeding canker on horse chestnut (A. hippocastanum). Despite dramatic differences in disease symptoms, European isolates are indistinguishable from the Indian type strain on the basis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)‐amplified gyrB sequences (Green et al., 2009), suggesting a monomorphic clonal population. Genome‐wide sequencing of the Indian type strain and three isolates from the UK revealed that the UK isolates were indeed monomorphic. However, it also revealed significant genetic divergence between the UK and Indian strains. The core conserved component accounts for 95% of the length of each Pae genome and displays more than 99.9% sequence identity across Indian and UK isolates. The variable compartments of the Pae genomes occupy the remaining 5% and here there is no detectable nucleotide sequence similarity between UK and Indian isolates. Within this variable compartment are numerous genes with the potential to interact with the host. For example, the UK isolates of Pae appear to have lost two type VI secretion systems that are conserved in the Indian isolate and all other sequenced strains from clade 3. In addition, in contrast with the Indian type strain, the UK isolates lack several T3SS‐associated genes (hrpW, hopAA1, hopF3, schF, avrPtoI) and a gene cluster predicted to encode an antimicrobial microcin. The adaptive significance of these differences has yet to be tested. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that at least some contribute to the dramatic phenotypic differences with which they correlate; in other words, whole‐genome sequencing has rapidly provided hypotheses about the genetic basis for the emergence of a new and exceptionally aggressive pathogen. Of course, these hypotheses need to be tested experimentally.

The complete genome sequence was also published recently for P. savastanoi pv. savastanoi (Psv) NCPPB 3335 (Rodríguez‐Palenzuela et al., 2010), a pathogen of olive trees that is closely related to Pph and Pta and a little more distantly related to Pae (Fig. 1). This offers the opportunity to identify genes involved in the colonization of woody parts of the host. Intriguingly, both Pae and Psv share in common a cluster of genes that is predicted to encode components of pathways for catabolism of phenolic compounds. These may equip Pae and Psv with the ability to break down lignin, either as a source of nutrition or perhaps as a mechanism for invading woody tissues.

CLADE 1: PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF THE MONOMORPHIC PATHOGEN P. SYRINGAE PV. TOMATO (PTO)

The first strain of P. syringae to be fully sequenced was Pto DC3000 (Buell et al., 2003), which causes bacterial speck on tomato and belongs to clade 1 (Fig. 1). This strain is actually rather atypical of members of pathovar tomato. For example, unlike other Pto strains, it can cause disease on A. thaliana. Almeida et al. (2009) generated a draft‐quality genome sequence for Pto strain T1, representative of a group of closely related Pto strains that do not cause disease on A. thaliana. Despite their close phylogenetic relationship and common ability to colonize and cause disease on tomato, DC3000 and T1 complete genome sequencing revealed substantial hidden variation in their repertoires of T3SS effectors (Almeida et al., 2009). The T1‐like strains are genetically highly monomorphic and only by genome‐wide sequencing could variations between individual strains be revealed. At the Eighth International Conference on Pseudomonas syringae Pathovars and Related Pathogens, B. Vinatzer announced three more draft genome sequences for T1‐like strains (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Vinatzer and colleagues exploited single‐nucleotide polymorphisms identified in these genome sequences as discriminatory markers to determine the genotypes of about 100 Pto isolates collected over several decades and several continents. Their genome‐enabled phylogeographical analysis revealed specific shifts in frequencies of genotypes, perhaps even complete replacements, and demonstrated frequent transmission of populations between different continents. These insights based on neutral phylogeny are impressive enough, but the study also revealed some genetic variants among the supposedly monomorphic population that may be of adaptive significance; the most spectacular example is a variant in the flagellin gene that apparently became fixed in populations during recent decades. This variant falls outside the previously characterized Flg22 region of the flagellin protein (Meindl et al., 2000). One interpretation of the evolutionary success of this variant is that it falls within a hitherto unknown pathogen‐associated molecular pattern (PAMP) and circumvents the tomato plant's PAMP‐triggered immunity.

CLADE 2: P. SYRINGAE PV. SYRINGAE (PSY)

Most strains of P. syringae classified as belonging to pathovar syringae fall into clades 2a, 2b and 2c (Fig. 1). They have been isolated from many different plant species and tend to be very successful epiphytes that can build up to large population sizes on the host without causing apparent disease (Hirano and Upper, 2000). In fact, isolates belonging to clade 2c are not known to cause disease at all (Mohr et al., 2008). A molecular basis for this observation was offered by the genome sequencing of strain Psy 642. This representative of clade 2c lacks the canonical Hrp T3SS and instead harbours an unusual T3SS rather distantly related to those found in plant‐pathogenic P. syringae and P. viridiflava strains (Clarke et al., 2010).

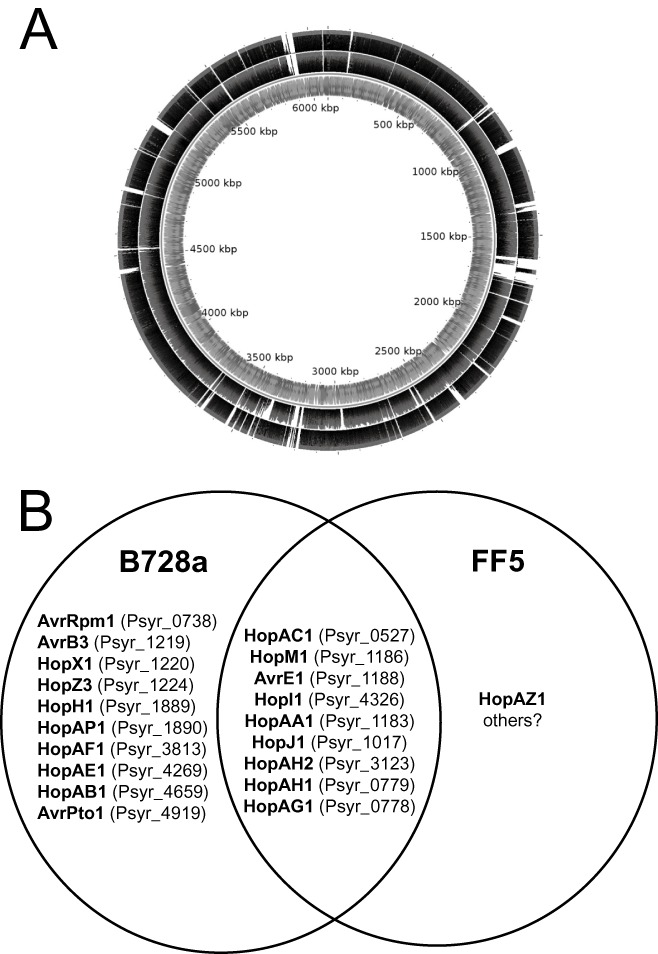

A finished complete genome sequence is available for Psy B728a (Feil et al., 2005). This strain, also within clade 2b, causes brown spot on bean and was isolated around 1987 in Wisconsin, USA. The ability to cause disease on bean has presumably evolved more than once in P. syringae; for example, strains of pathovar phaseolicola also infect bean, but belong to clade 3. We recently used the in‐house Illumina GA2 sequencer at The Sainsbury Laboratory to generate genome‐wide data for another member of clade 2b, Psy strain FF5. This strain was originally isolated by Sundin and Bender (1993) in Oklahoma, USA, where it was causing a stem tip dieback disease on ornamental pear (Pyrus calleryana). Comparison between the two clade 2b strains revealed substantial genetic differences, indicating extensive recombination since their divergence from each other. Figure 2A indicates that some regions of the B728a genome are absent from strain FF5, but conserved in strain 642; others are absent from 642, but conserved in FF5, and some are absent from both FF5 and 642. By also including pathogenic FF5 in the comparison, we can refine our list of candidate genetic variations underlying the lack of pathogenicity in strain 642.

Figure 2.

Comparison of genomes of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae (Psy) strains belonging to clades 2b and 2c. (A) Differential conservation of B728a sequences in Psy B728a and Psy 642. Illumina sequence reads are aligned against the previously published circular genome sequence of Psy B728a. The outer track comprises sequence reads from the Psy 642 genome, and the middle track comprises sequence reads from Psy FF5. The thickness of the black shading indicates the depth of aligned reads. The alignment was generated using BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) and displayed using CGview (Stothard and Wishart, 2005). (B) Venn diagram showing the conservation of genes encoding candidate type III secretion system (T3SS) substrates between Psy B728a and Psy FF5.

About 83% of the B728a genome is conserved in FF5 (Fig. 2A) and the two genomes share 95.3% nucleotide sequence identity over this conserved core of the genome. The two strains differ considerably with respect to their repertoires of T3SS effectors (Fig. 2B). It appears that either FF5 encodes significantly fewer effectors than B728a or, more likely, it encodes numerous hitherto unknown effectors and offers an exciting opportunity for prospecting for novelty.

HERE COMES THE FLOOD

At the Eighth International Conference on Pseudomonas syringae and Related Pathogens, D. Baltrus announced new draft genome sequences for 12 strains (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). I am aware of about 20 more unpublished P. syringae genome sequences that will become available within the next year. With the ever falling costs of high‐throughput sequencing, it seems inevitable that we will soon have hundreds or even thousands of genome sequences available.

All of the major P. syringae clades are now represented by at least one genome sequence, with the exception of 2a. This clade contains closely related strains isolated from a diverse range of host plants, including brown rice, Japanese apricot, tomato and citrus. It is not clear whether these strains are adapted to these different hosts or whether this clade comprises generalists that can colonize a broad range of plants. In either case, comparisons of genome sequences within this group might yield enlightening insights into host specificity.

The availability of multiple closely related genome sequences offers unprecedented opportunities to study the mechanics of evolution in P. syringae. As well as qualitative descriptions of the loss and gain of genes and point mutations, we need to construct quantitative models and assess these against the empirical data. For example, powerful methods are available for the discovery of signatures of natural selection (Nielsen, 2005) and for recombination. These methods have not yet been widely applied to P. syringae genomes. However, our preliminary analyses reveal that the genes displaying the strongest hallmarks of positive selection in the divergence between the Psy B728a and Psy FF5 lineages include those encoding a LuxR‐like response regulator (Psyr_3299), a glycine cleavage system protein H (Psyr_0247), an N‐acetyltransferase (Psyr_4220), a biotin carrier protein subunit (Psyr_4400), a nuclease (Psyr_0400), a NUDIX hydrolase (Psyr_0683), an aldose I‐epimerase (Psyr_0896), TonB (Psyr_0306), uroporphyrinogen‐III synthase (Psyr_0061) and a transcriptional regulator (Psyr_3051). If these genes really have been subject to strong positive selection since the divergence of strains FF5 and B728a, this implies that they had some functional significance in the adaptation to their distinct niches.

It is probably now already feasible to quantify the contributions of various evolutionary processes (positive selection, neutral drift, recombination, mutation, etc.) to the evolution of several lineages within P. syringae. It may even be possible to estimate the degree of genetic flux between different populations (e.g. distinct pathovars). However, for a complete understanding, we need many more complete genome sequences at a range of different phylogenetic resolutions.

The dimension that is most lacking in current datasets is population dynamics. Most strains of P. syringae are represented by no more than a single genome sequence. However, P. syringae genomes are highly dynamic; horizontal transfer of genomic islands can even be observed in real time (Lovell et al., 2009). We should expect significant genetic heterogeneity, and a single genome cannot represent an entire population. The problem is exacerbated by what Rocha (2008) called the ‘perspective bias’, that is the over‐representation of recent horizontal acquisitions and mildly deleterious mutations that have not yet been eliminated. To make robust inferences about adaptation, we need sufficiently large sample sizes to adequately sample the extent of variation within a given population. The optimal sample size will depend on the complexity of the population in question. We might predict that, in the context of an evolutionary arms race between host and pathogen, genes encoding virulence factors or pathogenicity determinants will be transiently present or may be under frequency‐dependent selection. Again, only by extensive intrapopulation sampling can we hope to fully understand these processes. As sequencing becomes ever more routine, it will soon be possible to exhaustively track genome evolution in real time.

In conclusion, this is an exciting time for the study of phytopathogenic bacteria, and P. syringae in particular. We will soon be awash with genomic data. I hope that these sequence data will be accompanied by detailed positional, temporal data that will allow us to construct and test detailed models of evolution, phylogeography and epidemiology. The challenges will then be to prioritize the scientific questions and to adapt existing computational methods to efficiently and robustly overcome the scale and quality limitations of these high‐throughput datasets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article is based on a presentation that I delivered at the Eighth International Conference on Pseudomonas syringae Pathovars and Related Pathogens held at Oxford University in September 2010. My attendance at this event was funded in part by The Society for General Microbiology. I am grateful to the organizers for their invitation to speak. Illumina sequencing of the FF5 and ATCC11528 genomes was funded by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation. 454 Sequencing of the 6605 and 11528 genomes was performed by and funded by The Genome Analysis Centre (TGAC), Norwich, UK. I am grateful to George Sundin for information about the isolation of strain FF5 and to all of the authors of unpublished work that is cited here. Work in my laboratory is currently funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK and by the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO), Uganda.

REFERENCES

- Almeida, N.F. , Yan, S. , Lindeberg, M. , Studholme, D.J. , Schneider, D.J. , Condon, B. , Liu, H. , Viana, C.J. , Warren, A. , Evans, C. , Kemen, E. , Maclean, D. , Angot, A. , Martin, G.B. , Jones, J.D. , Collmer, A. , Setubal, J.C. and Vinatzer, B.A. (2009) A draft genome sequence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato T1 reveals a type III effector repertoire significantly divergent from that of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. , Hanage, W.P. and Holt, K.E. (2010) Navigating the future of bacterial molecular epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 640–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussau, B. and Daubin, V. (2010) Genomes as documents of evolutionary history. Trends. Ecol. Evol. 25, 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell, C.R. , Joardar, V. , Lindeberg, M. , Selengut, J. , Paulsen, I.T. , Gwinn, M.L. , Dodson, R.J. , Deboy, R.T. , Durkin, A.S. , Kolonay, J.F. , Madupu, R. , Daugherty, S. , Brinkac, L. , Beanan, M.J. , Haft, D.H. , Nelson, W.C. , Davidsen, T. , Zafar, N. , Zhou, L. , Liu, J. , Yuan, Q. , Khouri, H. , Fedorova, N. , Tran, B. , Russell, D. , Berry, K. , Utterback, T. , Van Aken, S.E. , Feldblyum, T.V. , D'Ascenzo, M. , Deng, W.L. , Ramos, A.R. , Alfano, J.R. , Cartinhour, S. , Chatterjee, A.K. , Delaney, T.P. , Lazarowitz, S.G. , Martin, G.B. , Schneider, D.J. , Tang, X. , Bender, C.L. , White, O. , Fraser, C.M. and Collmer, A. (2003) The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 10 181–10 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C.R. , Cai, R. , Studholme, D.J. , Guttman, D.S. and Vinatzer, B.A. (2010) Pseudomonas syringae strains naturally lacking the classical P. syringae hrp/hrc locus are common leaf colonizers equipped with an atypical type III secretion system. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 23, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, N.J. , Harris, S.R. , Fraser, C. , Quail, M.A. , Burton, J. , van der Linden, M. , McGee, L. , von Gottberg, A. , Song, J.H. , Ko, K.S. , Pichon, B. , Baker, S. , Parry, C.M. , Lambertsen, L.M. , Shahinas, D. , Pillai, D.R. , Mitchell, T.J. , Dougan, G. , Tomasz, A. , Klugman, K.P. , Parkhill, J. , Hanage, W.P. and Bentley, S.D. (2011) Rapid pneumococcal evolution in response to clinical interventions. Science, 331, 430–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnac, S. , Lindeberg, M. and Collmer, A. (2009) Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system effectors: repertoires in search of functions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgapal, J.C. (1971) A preliminary note on some bacterial diseases of temperate plants in India. Indian Phytopathol. 24, 392–395. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, D.W. , Bradbury, J.F. , Goto, M. , Hayward, A.C. , Lelliott, R.A. and Schroth, M.N. (1980) International standards for naming pathovars of phytopathogenic bacteria and a list of pathovar names and pathotype strains. Rev. Plant Pathol. 59, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Falush, D. (2009) Toward the use of genomics to study microevolutionary change in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer, R.A. , Kemen, E. , Jones, J.D.G. and Studholme, D.J. (2009) De novo assembly of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a genome using Illumina/Solexa short sequence reads. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 291, 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil, H. , Feil, W.S. , Chain, P. , Larimer, F. , DiBartolo, G. , Copeland, A. , Lykidis, A. , Trong, S. , Nolan, M. , Goltsman, E. , Thiel, J. , Malfatti, S. , Loper, J.E. , Lapidus, A. , Detter, J.C. , Land, M. , Richardson, P.M. , Kyrpides, N.C. , Ivanova, N. and Lindow, S. (2005) Comparison of the complete genome sequences of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a and pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 11 064–11 069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiatrault, M.J. , Stodghill, P.V. , Bronstein, P.A. , Moll, S. , Lindeberg, M. , Grills, G. , Schweitzer, P. , Wang, W. , Schroth, G.P. , Luo, S. , Khrebtukova, I. , Yang, Y. , Thannhauser, T. , Butcher, B.G. , Cartinhour, S. and Schneider, D. (2010) Transcriptome analysis of Pseudomonas syringae identifies new genes, noncoding RNAs, and antisense activity. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2359–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez‐Ibanez, S. and Rathjen, J.P. (2010) The case for the defense: plants versus Pseudomonas syringae . Microbes Infect. 12, 428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. , Laue, B. , Fossdal, C.G. , A'Hara, S.W. and Cottrell, J.E. (2009) Infection of horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) by Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi and its detection by quantitative real‐time PCR. Plant Pathol, 58, 731–744. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S. , Studholme, D.J. , Laue, B.E. , Dorati, F. , Lovell, H. , Arnold, D. , Cottrell, J.E. , Bridgett, S. , Blaxter, M. , Huitema, E. , Thwaites, R. , Sharp, P.M. , Jackson, R.W. and Kamoun, S. (2010) Comparative genome analysis provides insights into the evolution and adaptation of Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi on Aesculus hippocastanum . PLoS ONE, 5, e10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, S.S. and Upper, C.D. (2000) Bacteria in the leaf ecosystem with emphasis on Pseudomonas syringae—a pathogen, ice nucleus, and epiphyte. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 624–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, K.E. , Parkhill, J. , Mazzoni, C.J. , Roumagnac, P. , Weill, F.X. , Goodhead, I. , Rance, R. , Baker, S. , Maskell, D.J. , Wain, J. , Dolecek, C. , Achtman, M. and Dougan, G. (2008) High‐throughput sequencing provides insights into genome variation and evolution in Salmonella typhi . Nat. Genet. 40, 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe, K. , Bateman, A. and Durbin, R. (2002) QuickTree: building huge neighbour‐joining trees of protein sequences. Bioinformatics, 18, 1546–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joardar, V. , Lindeberg, M. , Jackson, R.W. , Selengut, J. , Dodson, R. , Brinkac, L.M. , Daugherty, S.C. , Deboy, R. , Durkin, A.S. , Giglio, M.G. , Madupu, R. , Nelson, W.C. , Rosovitz, M.J. , Sullivan, S. , Crabtree, J. , Creasy, T. , Davidsen, T. , Haft, D.H. , Zafar, N. , Zhou, L. , Halpin, R. , Holley, T. , Khouri, H. , Feldblyum, T. , White, O. , Fraser, C.M. , Chatterjee, A.K. , Cartinhour, S. , Schneider, D.J. , Mansfield, J. , Collmer, A. and Buell, C. (2005) Whole‐genome sequence analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A reveals divergence among pathovars in genes involved in virulence and transposition. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6488–6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavín, J.L. , Kiil, K. , Resano, O. , Ussery, D.W. and Oguiza, J.A. (2007) Comparative genomic analysis of two‐component regulatory proteins in Pseudomonas syringae . BMC Genomics, 8, 397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. and Durbin, R. (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics, 25, 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeberg, M. , Cartinhour, S. , Myers, C.R. , Schechter, L.M. , Schneider, D.J. and Collmer, A. (2006) Closing the circle on the discovery of genes encoding Hrp regulon members and type III secretion system effectors in the genomes of three model Pseudomonas syringae strains. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeberg, M. , Myers, C.R. , Collmer, A. and Schneider, D.J. (2008) Roadmap to new virulence determinants in Pseudomonas syringae: insights from comparative genomics and genome organization. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 21, 685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, H.C. , Mansfield, J.W. , Godfrey, S.A. , Jackson, R.W. , Hancock, J.T. and Arnold, D.L. (2009) Bacterial evolution by genomic island transfer occurs via DNA transformation in planta. Curr. Biol. 19, 1586–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, J.W. (2009) From bacterial avirulence genes to effector functions via the hrp delivery system: an overview of 25 years of progress in our understanding of plant innate immunity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 721–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medini, D. , Donati, C. , Tettelin, H. , Masignani, V. and Rappuoli, R. (2005) The microbial pan‐genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl, T. , Boller, T. and Felix, G. (2000) The bacterial elicitor flagellin activates its receptor in tomato cells according to the address‐message concept. Plant Cell, 12, 1783–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, T.J. , Liu, H. , Yan, S. , Morris, C.E. , Castillo, J.A. , Jelenska, J. and Vinatzer, B.A. (2008) Naturally occurring nonpathogenic isolates of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae lack a type III secretion system and effector gene orthologues. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2858–2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R. (2005) Molecular signatures of natural selection. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, H.E. , Desveaux, D. and Guttman, D.S. (2011) Next‐generation genomics of Pseudomonas syringae . Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, A.R. , Jackson, R.W. , Mansfield, J.W. , Kaitell, V. , Thwaites, R. and Arnold, D.L. (2005) Exposure to host resistance mechanisms drives evolution of bacterial virulence in plants. Curr. Biol. 15, 2230–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M. , Wang, D. , Bradley, C.A. and Zhao, Y. (2011) Genome sequence analyses of Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. glycinea and subtractive hybridization‐based comparative genomics with nine pseudomonads. PLoS ONE, 6, e16451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, D.M. , Seshadri, R. , Pukatzki, S.U. and Mekalanos, J.J. (2006) Bacterial genomics and pathogen evolution. Cell, 124, 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, J.A. , Baltrus, D.A. , Nishimura, M.T. , Jeck, W.R. , Jones, C.D. and Dangl, J.L. (2009) De novo assembly using low‐coverage short read sequence data from the rice pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. oryzae . Genome Res. 19, 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, E.P. (2008) Evolutionary patterns in prokaryotic genomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez‐Palenzuela, P. , Matas, I.M. , Murillo, J. , López‐Solanilla, E. , Bardaji, L. , Pérez‐Martínez, I. , Rodríguez‐Moskera, M.E. , Penyalver, R. , López, M.M. , Quesada, J.M. , Biehl, B.S. , Perna, N.T. , Glasner, J.D. , Cabot, E.L. , Neeno‐Eckwall, E. and Ramos, C. (2010) Annotation and overview of the Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi NCPPB 3335 draft genome reveals the virulence gene complement of a tumour‐inducing pathogen of woody hosts. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1604–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.F. and Guttman, D.S. (2004) Evolution of the core genome of Pseudomonas syringae, a highly clonal, endemic plant pathogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1999–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, P.F. , Skandalis, N. , Kokkinidis, M. and Panopoulos, N.J. (2010) In silico analysis reveals multiple putative type VI secretion systems and effector proteins in Pseudomonas syringae pathovars. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, O. , Dujesiefken, D. , Stobbe, H. , Moreth, U. and Kehr, R. (2008) Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi associated with horse chestnut bleeding canker in Germany. Forest Pathol. 38, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Stothard, P. and Wishart, D.S. (2005) Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics, 21, 537–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studholme, D.J. , Ibanez, S.G. , MacLean, D. , Dangl, J.L. , Chang, J.H. and Rathjen, J.P. (2009) A draft genome sequence and functional screen reveals the repertoire of type III secreted proteins of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tabaci 11528. BMC Genomics, 10, 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin, G.W. and Bender, C.L. (1993) Ecological and genetic analysis of copper and streptomycin resistance in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 1018–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, F. , Takeuchi, K. , Katoh, E. , Murata, K. , Suzuki, T. , Marutani, M. , Kawasaki, T. , Eguchi, M. , Katoh, S. , Kaku, H. , Yasuda, C. , Inagaki, Y. , Toyoda, K. , Shiraishi, T. and Ichinose, Y. (2006) Identification of glycosylation genes and glycosylated amino acids of flagellin in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci . Cell. Microbiol. 8, 923–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sluys, M.A. , Monteiro‐Vitorello, C.B. , Camargo, L.E. , Menck, C.F. , Da Silva, A.C. , Ferro, J.A. , Oliveira, M.C. , Setubal, J.C. , Kitajima, J.P. and Simpson, A.J. (2002) Comparative, genomic analysis of plant‐associated bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 169–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmasek, C.M. and Eddy, S.R. (2001) A simple algorithm to infer gene duplication and speciation events on a gene tree. Bioinformatics, 17, 821–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]