SUMMARY

Rice blast, caused by the fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae, is the most devastating disease of rice and severely affects crop stability and sustainability worldwide. This disease has advanced to become one of the premier model fungal pathosystems for host—pathogen interactions because of the depth of comprehensive studies in both species using modern genetic, genomic, proteomic and bioinformatic approaches. Many fungal genes involved in pathogenicity and rice genes involved in effector recognition and defence responses have been identified over the past decade. Specifically, the cloning of a total of nine avirulence (Avr) genes in M. oryzae, 13 rice resistance (R) genes and two rice blast quantitative trait loci (QTLs) has provided new insights into the molecular basis of fungal and plant interactions. In this article, we consider the new findings on the structure and function of the recently cloned R and Avr genes, and provide perspectives for future research directions towards a better understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the rice–M. oryzae interaction.

INTRODUCTION

Rice is one of the most important food crops, feeding more than 50% of the world's population. Grain yield has been doubled since the 1960s with the help of the widespread cultivation of semi‐dwarf and hybrid rice cultivars. However, a production bottleneck has developed as a result of a combination of factors, including limited germplasm, and biotic and abiotic stresses, with yield losses caused by disease averaging upwards of 30% (Skamnioti and Gurr, 2009). Of particular importance, rice blast has re‐emerged as a major factor influencing stable rice production and food security in many rice‐growing countries in Asia and Africa. For example, in an average year, 50% of rice yield is lost in eastern Indian upland regions alone (Khush and Jena, 2009; Variar, 2007). Increases in temperature and average rainfall in this region have only exasperated the disease, as has been witnessed by increases in disease incidence and epidemics over the past few years, a situation that is only anticipated to worsen as global warming continues. In China, a large increase in the planted acreage of super‐hybrid rice has prompted a corresponding increase in blast, presumably as a result of the relatively narrow genetic base of hybrid rice and the increased use of nitrogen fertilizer. About 20% of the hybrid rice fields in China were reported to have severe seedling and neck blast in 2006 in a report from the Ministry of Agriculture of China (http://www.agri.gov.cn/xxgktjxx/). In South‐East Asia, there has been an increased severity of blast in Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines. This suggests that an erosion of resistance caused by pathogen evolution or a relaxing of screening efforts in breeding programmes, or both, are the main reasons for the loss of rice blast resistance. Blast is a growing concern in Africa because of the rapid increase in rice cultivation acreage and intensity to meet an annual 6% increase in consumption. Currently, blast occurs in the major rice production areas in eastern Africa, including Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel strategies to breed new rice cultivars that confer high and stable resistance to this important rice disease in order to ensure food security in these developing countries.

DISTRIBUTION OF BLAST RESISTANCE (R) GENES AND QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCI (QTLS) IN THE RICE GENOME

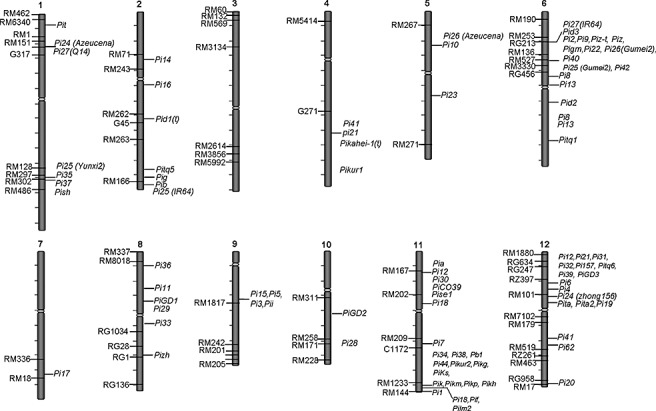

The use of host resistance has been proven to be the most effective and economical method to control rice blast. Rice blast resistance is generally classified into two main types: complete (true) resistance and partial resistance (field resistance) (Ezuka, 1972; Parlevliet, 1979). Complete resistance is race‐specific and controlled by a single dominant or recessive R gene that can be recognized by a cognate avirulence (Avr) gene in the pathogen (Skamnioti and Gurr, 2009). By contrast, partial resistance is non‐race‐specific and controlled by QTLs. It is not yet known whether there is a cognate Avr gene in the pathogen for a QTL in the host. To date, over 70 R genes have been identified, distributed among all chromosomes, except chromosome 3 (Yang et al., 2009; Fig. 1). Interestingly, many R genes are clustered, especially on chromosomes 6, 11 and 12. Although many blast QTLs have been roughly mapped, the genomic positions of only nine QTLs have been defined by molecular markers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the identified rice blast complete resistance genes and quantitative trait loci (QTLs). The main data were collected from the China Rice Data Centre (http://www.ricedata.cn/) and the paper by Yang et al. (2009). The mapped resistance genes and QTLs are located on the right side of the chromosomes. DNA markers are located on the left side of the chromosomes. Detailed information on the cloned genes is listed in Table 1.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF R GENES

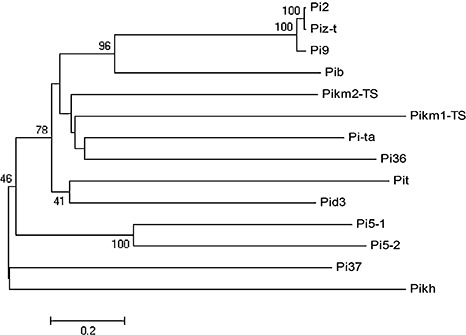

Thirteen complete R genes have been cloned in the last decade, as summarized in Table 1. Interestingly, except for Pi‐d2, all R genes encode nucleotide‐binding site and leucine‐rich repeat (NBS‐LRR)‐encoding proteins, one of the largest families of plant R genes (Liu et al., 2007a). The phylogenetic relationship of the 12 cloned NBS‐LRR R proteins was analysed (Fig. 2). As expected, Pi2, Pi9 and Piz‐t are clustered into the same clade. However, the allelic genes Pikm and Pikh, at the bottom of chromosome 11, are located in different clades relatively far apart. Two unique features can be observed in these R genes compared with those in other plant species. First, the Pi2/9 locus contains a complex cluster of NBS‐LRR genes with different specificities. The three cloned R genes, i.e. Pi9, Pi2 and Piz‐t, are all located in a 100‐kb region on chromosome 6, although Pi9 originates from the wild species O. minuta and the other two are from local cultivars. There are only eight amino acid differences between Pi2 and Piz‐t (Zhou et al., 2006). Additional R genes have also been mapped in the region, i.e. Pi40(t), Pigm, Pi26 and Piz. Pi40(t) was introgressed from wild species O. australiensis, with the other three identified from local cultivars (Deng et al., 2009; Jeung et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2005). Interestingly, all confer broad‐spectrum resistance to different sets of blast strains collected from different countries. The large number of closely related NBS‐LRR genes clustered in the region may contribute to the generation of new R alleles through recombination and uneven crossing over. It is expected that more R specificities will be identified at the locus from different local cultivars or wild rice accessions. The second unique feature is that two NBS‐LRR genes are required for Pikm‐ and Pi5‐mediated resistance (Ashikawa et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009). Two candidate NBS‐LRR genes (Pikm1‐TS and Pikm2‐TS) were identified at the Pikm locus. Complementary tests showed that transgenic plants carrying either of the NBS‐LRR genes did not confer Pikm resistance specificity. Pikm resistance was complemented only when the two candidate genes were present in the same plants, suggesting that Pikm‐mediated resistance is controlled by two adjacent NBS‐LRR genes. A similar case was also found at the Pi5 locus (Lee et al., 2009). Transformation experiments have shown that both NBS‐LRR genes, Pi5‐1 and Pi5‐2, are required for Pi5‐mediated resistance. Similarly, a new study has shown that, in Arabidopsis, both adjacent NBS‐LRR genes, RRS1 and RPS4, are required for resistance to R. solanacearum and P. syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 expressing avrRps4 (Narusaka et al., 2009). Understanding how these two R proteins work together, and which one interacts with the cognate Avr protein, will certainly provide new insights into the molecular basis of this type of R‐gene‐mediated resistance.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the cloned blast resistance genes and quantitative trait loci (QTLs) in rice.

| R gene | Encoding protein | Cognate Avr gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pib | NBS‐LRR | NA | Wang et al., 1999 |

| Pita | NBS‐LRR | Yes | Bryan et al., 2000 |

| Pi9 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Qu et al., 2006 |

| Pi2 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Zhou et al., 2006 |

| Piz‐t | NBS‐LRR | Yes | Zhou et al., 2006 |

| Pi‐d2 | Receptor kinase | NA | Chen et al., 2006 |

| Pi36 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Liu et al., 2007b |

| Pi37 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Lin et al., 2007 |

| Pikm | NBS‐LRR | Yes | Ashikawa et al., 2008 |

| Pit | NBS‐LRR | NA | Hayashi and Yoshida, 2009 |

| Pi5 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Lee et al., 2009 |

| Pid3 | NBS‐LRR | NA | Shang et al., 2009 |

| Pikh | NBS‐LRR | NA | Rai et al., 2009 |

| p21 * | Proline‐containing protein | NA | Fukuoka et al., 2009 |

| Pb1 * | NBS‐LRR | NA | Hayashi et al., 2009 |

Cloned blast resistance QTLs.

NA, not available; NBS‐LRR, nucleotide‐binding site and leucine‐rich repeat.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of the cloned rice nucleotide‐binding site and leucine‐rich repeat resistance (NBS‐LRR R) proteins conferring resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae. Protein sequences were collected from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and used for alignment with ClustalW 2.0 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). The neighbour‐joining tree was constructed by the program mega 4.0 with the bootstrap test (bootstrap replications, 1000; random seeds, 24 054), and a bootstrap value of less than 40% for each branch was set as a cut‐off.

It is noteworthy that Pi‐d2 is the only non‐NBS‐LRR‐encoding R gene in rice cloned to date. The dominant R gene was identified in the Chinese rice variety Digu, which confers resistance to all 156 blast isolates collected from China and Japan, and has been widely used in breeding programmes in China as a blast‐resistant donor (Chen et al., 2006). Pi‐d2 encodes a receptor‐like kinase protein with a predicted extracellular domain of a bulb‐type, mannose‐specific binding lectin (B‐lectin) and an intracellular serine–threonine kinase domain. Pi‐d2 is a plasma membrane‐localized protein. The lectin domains in Pi‐d2 contain predicted hydrophobic regions that form a structural pocket predicted for ligand binding. These results suggest that Pi‐d2 may detect its cognate Avr protein via a direct mechanism. Isolation of the Avr gene of the Pi‐d2 gene in M. oryzae in the future will shed light onto the Pi‐d2‐mediated broad‐spectrum resistance to rice blast.

CLONING AND CHARACTERIZATION OF BLAST QTLS

Because partial resistant cultivars confer moderate and non‐race‐specific resistance to rice blast, their resistance is generally more durable and broad spectrum in natural conditions (Skamnioti and Gurr, 2009). For example, a local moderate‐resistant cultivar called Acuce in Yunnan Province, China, has been cultivated for over 100 years and is still being grown by farmers in blast conducive regions (Y. Zhu, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China). Therefore, the identification and cloning of resistance QTLs will provide new strategies to effectively control rice blast. The first set of blast QTLs was identified in the durably resistant upland cultivar Moroberekan using the interval mapping method (Wang et al., 1994). Nine major QTLs have been defined with molecular markers, i.e. Pb1 (Fujii et al., 2000), pi21 (Fukuoka and Okuno, 2001; Fukuoka et al., 2007), Pi34 (Zenbayashi et al., 2002; Zenbayashi‐Sawata et al., 2007), Pif (Monosi et al., 2004), Pikur1 and Pikur2 (Monosi et al., 2004), Pi‐se1 (Wisser et al., 2005), Pi35 (Nguyen et al., 2006) and Pikahei‐1(t) (Miyamoto et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2008) (Fig. 1). Fukuoka and Okuno (2001) identified the recessive partial (non‐race‐specific) resistance gene pi21 located on chromosome 4 from an upland cultivar Owarihatamochi. Recently, this group reported the first cloned partial R gene or QTL (2007, 2009). Pi21 encodes a proline‐rich protein that includes a putative heavy metal‐binding domain and putative protein–protein interaction motifs. Interestingly, wild‐type Pi21 appears to slow plant defence responses, and resistant pi21‐containing plants carrying a deletion in its proline‐rich motif inhibit this slowing. Another major QTL, Pb1, has been cloned recently from an indica rice cultivar Mudan that has been cultivated for over 20 years (Fujii et al., 2000; Hayashi et al., 2009). It confers more effective resistance at adult stages, especially for panicle blast. The Pb1 gene also encodes a coiled‐coil NBS‐LRR protein. It will be interesting to determine whether these QTLs can be recognized by a single or multiple Avr gene, and what the mechanisms are for the activation of defence pathways following blast infection.

IDENTIFICATION OF GENES DOWNSTREAM OF R GENES

The identification of genes downstream of R genes is essential for the dissection of the resistance pathway. This has been a challenging task because of the lack of suitable protein–protein interaction assay methods for NSB‐LRR R proteins and gene function redundancy and lethality when mutagenesis is used. Using Pi‐ta as the bait in yeast two‐hybrid (Y2H) screens, an Avr–Pi‐ta interacting protein, named AVI3, was identified from a blast‐infected cDNA library of the Pi‐ta‐carrying cultivar Kay (Y. Jia, USDA‐ARS, Stuttgart, AR, USA). This gene encodes a putative transcription factor and is induced by a fungal elicitor in rice suspension cells. The role of AVI3 in Pi‐ta‐mediated signal pathways is being investigated. Using a mutagenesis approach, a Pi‐ta‐expressing susceptible mutant was identified, named Ptr(t), that is more probably specific to Pi‐ta‐mediated signal recognition because it is not required for other R genes (Jia and Martin, 2008). Genetic analysis has indicated that Ptr(t) segregates as a single dominant nuclear gene and is linked with Pi‐ta. Genetic analysis has shown that the Pi‐ta and Ptr(t) genes are located within a nine‐megabase region. The cloning of Ptr(t) will be a significant advancement in the understanding of Pi‐ta‐mediated signal recognition and transduction.

CLONING OF Avr GENES

Pathogen effectors have been defined recently as all pathogen proteins and small molecules that alter host cell structure and function (Hogenhout et al., 2009; de Wit and Stergiopoulos, 2009). Avr proteins are a special class of effectors that are recognized by corresponding R proteins, which lead to direct or indirect activation of host defence responses against pathogen invasion. During recent years, significant progress has been obtained in the identification of Avr effectors of the blast fungus, which has provided great insight into the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of fungal pathogenesis, and has also shed light onto the mechanisms of co‐evolution between fungal effectors and host R proteins.

Among more than 40 identified M. oryzae Avr genes (Ma et al., 2006), nine Avr genes have been cloned and characterized (Table 2). PWL1 and PWL2 were the first two cloned, which confer avirulence of the Eleusine and Oryza isolates, respectively, towards weeping lovegrass, Eragrostis curvula (Kang et al., 1995; Sweigard et al., 1995). Orbach et al. (2000) cloned the second rice blast Avr gene AvrPi‐ta, which encodes a putative 223 amino acids containing secreted protein with a conserved metalloprotease domain. Recently, using a map‐based cloning strategy, Li et al. (2009) successfully cloned the AvrPiz‐t gene, which encodes a putative secreted protein without any homologues in M. oryzae or other sequenced fungi. A recent whole‐genome sequencing study by Yoshida et al. (2009) showed that M. oryzae isolate Ina168 contains an extra 1.68 Mb of DNA sequence that is absent from the sequenced strain 70‐15. Most interestingly, a total of 318 candidate effector genes are predicted in this extra DNA. Sequence comparative and association genetic analysis identified three novel Avr genes, i.e. AvrPia, AvrPii and AvrPik/km/kp. All three were confirmed to be secreted proteins with a predicted signal peptide at their N‐terminals. AvrPia and AvrPik/km/kp encode 85 amino acids and 113 amino acids with unknown functions, respectively. Another group also cloned AvrPia via a map‐based cloning strategy from a gain of virulent mutant Ina168m95‐1, which is virulent to rice cultivar Aichi‐asahi harbouring the R gene Pia (Miki et al., 2009). AvrPii is a 70‐amino‐acid peptide with a predicted motif‐1 ([LI]xAR[SE][DSE]) containing a conserved LxAR motif, which also appears in AvrPiz‐t, and motif‐2 ([RK]CxxCxxxxxxxxxxxxH), which is a zinc finger‐like motif involved in protein–protein interaction. Interestingly, the predicted LxAR motif containing proteins represents a new large family of effectors in the rice blast genome (Yoshida et al., 2009, B. Zhou, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China). Further elucidation of the function of this group of effectors will provide new information on how M. oryzae effectors are translocated to rice cells.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the cloned avirulence (Avr) effector genes from Magnaporthe oryzae.

| Avr gene | Encoding protein | Cognate R gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWL1 | Glycine‐rich, hydrophilic protein, secreted protein | NA | Kang et al., 1995; Sweigard et al., 1995 |

| PWL2 | Glycine‐rich, hydrophilic protein, secreted protein | NA | Kang et al., 1995; Sweigard et al., 1995 |

| AvrPi‐ta | Secreted protein | Pi‐ta | Orbach et al., 2000 |

| Avr1‐CO39 | Secreted protein | Pi‐CO39 | Leong, 2008 |

| ACE1 | Polyketide synthase /peptide synthetase | Pi33 | Böhnert et al., 2004 |

| AvrPiz‐t | Secreted protein | Piz‐t | Li et al., 2009 |

| AvrPia | Secreted protein | Pia | Miki et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 2009 |

| AvrPii | Secreted protein | Pii | Yoshida et al., 2009 |

| AvrPik/km/kp | Secreted protein | Pik/km/kp | Yoshida et al., 2009 |

NA, not available.

Using a map‐based cloning approach, Avr1‐CO39 was delimited to a 1.05‐kb region with several potential open reading frames (ORFs) (Farman and Leong, 1998; Farman et al., 2002). Recently, this group reported that the 1.05‐kb region contains eight predicted ORFs and that Orf3 should be the functional Avr1CO39 gene, which encodes 89 amino acids with a predicted signal sequence. They also found that Avr1CO39 is transcribed only in plant cells, and that fusion with green fluorescent protein (GFP) shows reduced presence in resistance plant lines as a result of the activation of defence responses (Leong, 2008).

ACE1 is a unique Avr gene because it encodes a hybrid polyketide synthase/nonribosomal peptide synthetase (PKS‐NRPS) (Böhnert et al., 2004). The enzyme is probably involved in the biosynthesis of a polyketide (Collemare et al., 2008). ACE1 biosynthetic activity is required for its avirulence; however, the avirulence signal recognized by the cognate R gene Pi33 in rice cultivars is not the ACE1 protein, but the secondary metabolite synthesized by ACE1 (Böhnert et al., 2004). Interestingly, ACE1 is appressorium‐specific and is expressed in mature appressoria differentiated on plant leaves or artificial cellophane membranes during the penetration process (Fudal et al., 2007). These results suggest that ACE1 is connected to the onset of appressorium‐mediated penetration, but does not enter directly into rice cells to trigger defence responses.

POPULATION DIVERSITY AND GENETIC INSTABILITY OF Avr GENES IN THE FIELD

A highly diverse genetic structure is a main character of the blast populations worldwide, and can be largely attributed to genetic instability and the loss of avirulence to R genes (Skamnioti and Gurr, 2009; Tharreau et al., 2009). The frequent generation of new virulent races or pathotypes leads to the short life of many newly released cultivars. Recent studies on the variations of Avr genes have provided new insight into the mechanism of blast genetic variations and instability. Multiple genetic mutation events, including deletion (Orbach et al., 2000), point mutations (Orbach et al., 2000) and transposon insertion (Kang et al., 2001), have been found to be the main driving force to the creation of new virulent races that break major R genes. For example, Orbach et al. (2000) found that a fragment deletion from intron 3 to exon 4 in the mutant strain CP983, several nonsense mutations (e.g. TGG1487TAG in the mutant strain CP918, TTA1736TGA in the mutant strain CP1615) and a missense mutation (e.g. GAA1718GGA in the mutant strain CP1635) led to a gain of virulence of the AvrPi‐ta gene. In addition, transposon insertion usually leads to a gain of virulence for Avr genes through a change in gene expression level or pattern. Fudal et al. (2005) found that an insertion of a 1.9‐kb MINE retrotransposon in the last ACE1 exon led to a loss of ACE1 avirulence and activated its virulence in the virulent isolate 2/0/3. Similar events were also found in AvrPi‐ta (Zhou et al., 2007) and AvrPiz‐t (Li et al., 2009). Close monitoring of the profiles of known Avr genes in the field will provide a reliable reference for the deployment of R genes in rice production.

INNATE IMMUNITY AND R GENE SIGNALLING

Plant‐pathogenic bacteria and fungi suppress plant innate immunity and promote pathogenesis by injecting effector proteins into plant cells (Hogenhout et al., 2009). These effectors can be generally divided into two main groups. One group, pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), is recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) predominantly localized in the extracellular matrix. This recognition was previously known as basal defence, but is now referred to as PAMP‐triggered immunity (PTI) (Block et al., 2008; Jones and Dangl, 2006). The second group contains avirulence proteins that interact directly or indirectly with the cognate R proteins in the host. This recognition is associated with the well‐known gene‐for‐gene hypothesis, and is now called effector‐triggered immunity (ETI). Recent findings have shown that plants can rapidly develop effective ETI to inhibit pathogen growth when PTI is overcome by newly evolved pathogen effectors (Xiang et al., 2008). At present, PTI‐mediated defence has been well investigated in plant–bacteria pathosystems (Nicaise et al., 2009), but not in plant fungal diseases. Recently, the bacterial flagellin factor flg22 has been found to induce the rice immune response, which was perceived by rice PRR OsFLS2, the rice orthologue of AtFLS2 (Takai et al., 2008; Takakura et al., 2008). This result suggests that rice may have a similar PTI‐mediated defence system, but how effective the system is to the defence of rice pathogens remains unknown.

In the model plant Arabidopsis, SGT1 and RAR1 have been shown to play a role in the ETI‐mediated defence signalling pathway (Azevedo et al., 2002). In rice, orthologues OsRAR1 and OsSGT1 associate with the rice small GTPase protein OsRac1 and are involved in resistance to bacterial blight and blast (Kawasaki et al., 1999; Ono et al., 2001; Suharsono et al., 2002; Thao et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2007). Recently, the NBS‐LRR R protein Pit has been found to interact directly with OsRac1, which leads to the activation of the ETI‐mediated immune response (Kawano et al., 2009). These results demonstrate that rice has a similar SGT1/RAR1‐mediated signalling pathway to Arabidopsis, and the PTI and ETI defence pathways may be interconnected through membrane‐associated proteins such as OsRac1.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Rice continues to be the nutritional, financial and social lifeline for the majority of humanity, with its consumption growing dramatically in many parts of the world, including sub‐Saharan Africa. Although intensive breeding and refined cultural practices have improved the rice yield considerably in the last several decades, many constraints will continue to limit sustainable rice production in most rice‐growing regions. Among them, rice blast disease is considered to be the largest threat for stable rice production. As a result of the high level of pathogen instability in the field, breeders have battled rice blast by introducing new resistance genes into elite cultivars, but continue to be frustrated by the short life of newly released cultivars. Therefore, a deep and thorough understanding of how R and Avr proteins interact in the initial recognition process, the function of Avr effectors and their target host proteins in disease development, the exact structure of the pathogen population in the field and a clear genetic background of each rice cultivar is pivotal for the development of effective control methods for this important disease. Although impressive progress has been made in the above areas in recent years, many unanswered questions and challenges (listed below) lie ahead for the rice blast community.

-

•

How do R proteins interact with their cognate Avr proteins? Although a direct interaction between AvrPi‐ta and Pi‐ta was revealed by far‐western analysis several years ago (Jia et al., 2000), no new evidence has been provided to demonstrate the direct interaction of the two proteins in vivo. Using Piz‐t or AvrPiz‐t as bait in both Y2H and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analyses, no direct interaction between these two proteins was detected in our laboratory. Therefore, the determination of the interaction model for all nine cloned Avr and R gene pairs is a daunting task (Table 2), and new techniques should be applied to investigate the relationship between Avr and R proteins. Cloning of Pikm (Ashikawa et al., 2008) and Pi5 (Lee et al., 2009) is exciting, but also raises a few critical questions as follows: Why are two highly homologous NBS‐LRR proteins required for Pikm‐ and Pi5‐mediated resistance? Are both proteins involved in the interaction with the cognate Avr protein? Is it possible that one of the R proteins functions as a ‘decoy’ in the newly proposed Decoy model (Van der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2008)?

-

•

What are the downstream genes of R genes? Apart from the results obtained for the Pi‐ta gene, no progress has been made in the identification of the genes required for other R‐gene‐mediated resistance. We used both Y2H and mutagenesis to identify downstream genes for the Pi9‐, Pi2‐ and Piz‐t‐mediated pathways, but failed. New proteomic approaches, such as affinity binding, can be applied to pull down interacting proteins, as described by Nakashima et al. (2008)

-

•

What is the translocation mechanism of the blast Avr effectors? The identification of the LxAR motif in both AvrPiz‐t and AvrPii has provided clues on the possible translocation mechanism in M. oryzae (Li et al., 2009; Yoshida et al., 2009). To determine whether it has a similar function to the RXLR motif in the Avr proteins of Phytophthora species requires more experiments (Kamoun, 2006).

-

•

What are the targets of Avr proteins in rice cells and their functions in the host response to pathogen infection? AVI3 is the only rice protein that interacts with AvrPi‐ta. Its function in Pi‐ta‐mediated resistance is unknown. Using AvrPiz‐t as the bait in Y2H screens, we identified eight interacting proteins from a rice cDNA library. Interestingly, four are involved in the ubiquitination pathway, suggesting a possible role of the ubiquitination‐mediated pathway in the plant and fungal interaction (Birch et al., 2009).

-

•

How to predict the durability of R genes based on pathogen population? The breeding of new cultivars for a specific environment is a time‐consuming and expensive process. The rapid breakdown of disease resistance of newly released cultivars has prompted breeders to seek ways in which to keep R genes effective for the long term. As more and more Avr and R gene pairs are cloned, it is possible to monitor the frequency of most Avr genes present in a field population and use the information to strategically deploy R genes in a specific environment. Large‐scale and controlled field experiments are needed to test the feasibility of this approach.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their critical comments on this paper, and funding support from the 973 Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (#30828022, #30871335) and the NSF‐Plant Genome Research Program (#0605017).

REFERENCES

- Ashikawa, I. , Hayashi, N. , Yamane, H. , Kanamori, H. , Wu, J. , Matsumoto, T. , Ono, K. and Yano, M. (2008) Two adjacent nucleotide‐binding site–leucine‐rich repeat class genes are required to confer Pikm‐specific rice blast resistance. Genetics, 180, 2267–2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, C. , Sadanandom, A. , Kitagawa, K. , Freialdenhoven, A. , Shirasu, K. and Schulze‐Lefert, P. (2002) The RAR1 interactor SGT1, an essential component of R gene‐triggered disease resistance. Science, 295, 2073–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch, P.R.J. , Armstrong, M. , Bos, J. , Boevink, P. , Gilroy, E.M. , Taylor, R.M. , Wawra, S. , Pritchard, L. , Conti, L. , Ewan, R. , Whisson, S.C. , Van West, P. , Sadanandom, A. and Kamoun, S. (2009) Towards understanding the virulence functions of RXLR effectors of the oomycete plant pathogen Phytophthora infestans . J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block, A. , Li, G. , Fu, Z.Q. and Alfano, J.R. (2008) Phytopathogen type III effector weaponry and their plant targets. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhnert, H.U. , Fudal, I. , Dioh, W. , Tharreau, D. , Nottéghem, J.L. and Lebrun, M.‐H. (2004) A putative polyketide synthase/peptide synthetase from Magnaporthe grisea signals pathogen attack to resistant rice. Plant Cell, 16, 2499–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, G.T. , Wu, K. , Farrall, L. , Jia, Y. , Hershey, H.P. , McAdams, S.A. , Faulk, K.N. , Donaldson, G.K. , Tarchini, R. and Valent, B. (2000) A single amino acid difference distinguishes resistant and susceptible alleles of the rice blast resistance gene Pi‐ta . Plant Cell, 12, 2033–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Shang, J. , Chen, D. , Lei, C. , Zou, Y. , Zhai, W. , Liu, G. , Xu, J. , Ling, Z. , Cao, G. , Ma, B. , Wang, Y. , Zhao, X. , Li, S. and Zhu, L. (2006) A B‐lectin receptor kinase gene conferring rice blast resistance. Plant J. 46, 794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collemare, J. , Pianfetti, M. , Houlle, A.‐E. , Morin, D. , Camborde, L. , Gagey, M.‐J. , Barbisan, C. , Fudal, I. , Lebrun, M.‐H. and Böhnert, H.U. (2008) Magnaporthe grisea avirulence gene ACE1 belongs to an infection‐specific gene cluster involved in secondary metabolism. New Phytol. 179, 196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y. , Zhu, X. , Xu, J. , Chen, H. and He, Z. (2009) Map‐based cloning and breeding application of a broad‐spectrum resistance gene Pigm to rice blast In: Advances in Genetics, Genomics and Control of Rice Blast Disease (Wang G.L. and Valent B., eds), pp. 161–171. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ezuka, A. (1972) Field resistance of rice varieties to rice blast disease. Rev. Plant Prot. Res. 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Farman, M.L. and Leong, S.A. (1998) Chromosome walking to the AVR1‐CO39 avirulence gene of Magnaporthe grisea: discrepancy between the physical and genetic maps. Genetics, 150, 1049–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farman, M.L. , Eto, Y. , Nakao, T. , Tosa, Y. , Nakayashiki, H. , Mayama, S. and Leong, S.A. (2002) Analysis of the structure of the AVR1‐CO39 avirulence locus in virulent rice‐infecting isolates of Magnaporthe grisea . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 15, 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudal, I. , Böhnert, H.U. , Tharreaub, D. and Lebrun, M.‐H. (2005) Transposition of MINE, a composite retrotransposon, in the avirulence gene ACE1 of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Fungal. Genet. Biol. 42, 761–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudal, I. , Collemare, J. , Böhnert, H.U. , Melayah, D. and Lebrun, M.‐H. (2007) Expression of Magnaporthe grisea avirulence gene ACE1 is connected to the initiation of appressorium mediated penetration. Eukaryot. Cell, 6, 546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, K. , Hayano‐Saito, Y. , Saito, K. , Sugiura, N. , Hayashi, N. , Tsuji, T. , Izawa, T. and Iwasaki, M. (2000) Identification of a RFLP marker tightly linked to the panicle blast resistance gene Pb1, in rice. Breed Sci. 50, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka, S. and Okuno, K. (2001) QTL analysis and mapping of pi21, a recessive gene for field resistance to rice blast in Japanese upland rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka, S. , Saka, N. , Koga, H. , Shimizu, T. , Ebana, K. , Takahasi, A. , Hirochika, H. , Yano, M. and Okuno, K. (2007) Molecular cloning and gene pyramiding of QTLs controlling field resistance to blast in rice. The 4th International Rice Blast Conference, 9–14 October 2007, Changsha, Hunan, China. Abstract 32 (Wang G.L., ed), p. 21.Changsha, Hunan, China:Hunan Agricultural University. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka, S. , Saka, N. , Koga, H. , Ono, K. , Shimizu, T. , Ebana, K. , Hayashi, N. , Takahashi, A. , Hirochika, H. , Okuno, K. and Yano, M. (2009) Loss of function of a proline‐containing protein confers durable disease resistance in rice. Science, 325, 998–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K. and Yoshida, H. (2009) Refunctionalization of the ancient rice blast disease resistance gene Pit by the recruitment of a retrotransposon as a promoter. Plant J. 57, 413–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, N. , Inou, H. , Kato, T. , Hayano‐Saito, Y. , Shirota, M. , Funao, T. , Shimizu, T. and Takatsuji, H. (2009) Cloning of Pb1, the durable panicle blast resistance of rice. Abstract of the XIV Congress on Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions, 19–23 July 2003, Quebec Canada. International Society of Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, Quebec, Canada.

- Hogenhout, S.A. , Van der Hoorn, R.A.L. , Terauchi, R. and Kamoun, S. (2009) Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant‐associated organisms. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeung, J.U. , Kim, B.R. , Cho, Y.C. , Han, S.S. , Moon, H.P. , Lee, Y.T. and Jena, K.K. (2007) A novel gene, Pi40(t), linked to the DNA markers derived from NBS‐LRR motifs confers broad spectrum of blast resistance in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 115, 1163–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. , McAdams, S.A. , Bryan, G.T. , Hershey, H.P. and Valent, B. (2000) Direct interaction of resistance gene and avirulence gene products confers rice blast resistance. EMBO J. 19, 4004–4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. and Martin, R. (2008) Identification of a new locus, Ptr(t), required for rice blast resistance gene Pi‐ta‐mediated resistance. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 21, 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.D.G. and Dangl, J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature, 444, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun, S. (2006) A catalogue of the effector secretome of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 41–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S. , Sweigard, J.A. and Valent, B. (1995) The PWL host specificity gene family in the blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 8, 939–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S. , Lebrun, M.H. , Farrall, L. and Valent, B. (2001) Gain of virulence caused by insertion of a Pot3 transposon in a Magnaporthe grisea avirulence gene. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, Y. , Akamatsu, A. , Hayashi, K. , Housen, Y. , Loh, P.C. , Nakashima, A. , Takahashi, H. , Yoshida, H. , Kawasaki, T. and Shimamoto, K. (2009) The activation of OsRac1 by R protein plays a critical role in innate immune responses in rice. Abstract of the XIV Congress on Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions, 19–23 July 2003, Quebec Canada. International Society of Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, Quebec, Canada.

- Kawasaki, T. , Henmi, K. , Ono, E. , Hatakeyama, S. , Iwano, M. , Satoh, H. and Shimamoto, K. (1999) The small GTP‐binding protein rac is a regulator of cell death in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 10922–10926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush, G.S. and Jena, K.K. (2009) Current status and future prospects for research on blast resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) In: Advances in Genetics, Genomics and Control of Rice Blast Disease (Wang G.L. and Valent B., eds), pp. 1–10. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. , Song, M. , Seo, Y. , Kim, H. , Ko, S. , Cao, P. , Suh, J. , Yi, G. , Roh, J. , Lee, S. , An, G. , Hahn, T. , Wang, G. , Ronald, P. and Jeon, J. (2009) Rice Pi5‐mediated resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae requires the presence of two coiled‐coil–nucleotide‐binding–leucine‐rich repeat genes. Genetics, 181, 1627–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong, S.A. (2008) The ins and outs of host recognition of Magnaporthe oryzae In: Genomics of Disease (Gustafson J.P., Taylor J. and Stacey G., eds), pp. 199–216. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. , Wang, B. , Wu, J. , Lu, G. , Hu, Y. , Zhang, X. , Zhang, Z. , Zhao, Q. , Feng, Q. , Zhang, H. , Wang, Z. , Wang, G. , Han, B. , Wang, Z. and Zhou, B. (2009) The Magnaporthe oryzae avirulence gene AvrPiz‐t encodes a predicted secreted protein that triggers the immunity in rice mediated by the blast resistance gene Piz‐t . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 22, 411–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F. , Chen, S. , Que, Z. , Wang, L. , Liu, X. and Pan, Q. (2007) The blast resistance gene Pi37 encodes a nucleotide binding site–leucine‐rich repeat protein and is a member of a resistance gene cluster on rice chromosome 1. Genetics, 177, 1871–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Liu, X. , Dai, L. and Wang, G.L. (2007a) Recent progress in elucidating the structure, function and evolution of disease resistance genes in plants. J. Genet. Genomics, 34, 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Lin, F. , Wang, L. and Pan, Q. (2007b) The in silico map‐based cloning of Pi36, a rice coiled‐coil–nucleotide‐binding site–leucine‐rich repeat gene that confers race‐specific resistance to the blast fungus. Genetics, 176, 2541–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.H. , Wang, L. , Feng, S.J. , Lin, F. , Xiao, Y. and Pan, Q.H. (2006) Identification and fine mapping of AvrPi15, a novel avirulence gene of Magnaporthe grisea . Theor. Appl. Genet. 113, 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki, S. , Matsui, K. , Kito, H. , Otsuka, K. , Ashizawa, T. , Yasuda, N. , Fukiya, S. , Sato, J. , Hirayae, K. , Fujita, Y. , Nakajima, T. , Tomita, F. and Sone, T. (2009) Molecular cloning and characterization of the AVR‐Pia locus from a Japanese field isolate of Magnaporthe oryzae . Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, M. , Yano, M. and Hirasawa, H. (2001) Mapping of quantitative trait loci conferring blast weld resistance in the Japanese upland rice variety Kahei. Breed Sci. 51, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Monosi, B. , Wisser, R.J. , Pennill, L. and Hulbert, S.H. (2004) Full‐genome analysis of resistance gene homologues in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 1434–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, A. , Chen, L. , Thao, N.P. , Fujiwara, M. , Wong, H.L. , Kuwano, M. , Umemura, K. , Shirasu, K. , Kawasaki, T. and Shimamoto, K. (2008) RACK1 functions in rice innate immunity by interacting with the Rac1 immune complex. Plant Cell, 20, 2265–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narusaka, M. , Shirasu, K. , Noutoshi, Y. , Kubo, Y. , Shiraishi, T. , Iwabuchi, M. and Narusaka, Y. (2009) RRS1 and RPS4 provide a dual Resistance‐gene system against fungal and bacterial pathogens. Plant J. 60, 218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. , Koizumi, S. , La, T.N. , Zenbayashi, K.S. , Ashizawa, T. , Yasuda, N. , Imazaki, I. and Miyasaka, A. (2006) Pi35(t), a new gene conferring partial resistance to leaf blast in the rice cultivar Hokkai 188. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113, 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicaise, V. , Roux, M. and Zipfel, C. (2009) Recent advances in PAMP‐triggered immunity against bacteria: pattern recognition receptors watch over and raise the alarm. Plant Physiol. 150, 1638–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono, E. , Wong, H.L. , Kawasaki, T. , Hasegawa, M. and Kodamo, K. (2001) Essential role of the small GTPase Rac in disease resistance of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 759–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbach, M.J. , Farrall, L. , Sweigard, J.A. , Chumley, F.G. and Valent, B. (2000) A telomeric avirulence gene determines efficacy for the rice blast resistance gene Pi‐ta . Plant Cell, 12, 2019–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlevliet, J.E. (1979) Components of resistance that reduce the rate of epidemic development. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 17, 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S. , Liu, G. , Zhou, B. , Bellizz, I.M. , Zeng, L. , Dai, L. , Han, B. and Wang, G.L. (2006) The broad‐spectrum blast resistance gene Pi9 encodes a nucleotide‐binding site–leucine‐rich repeat protein and is a member of a multigene family in rice. Genetics, 172, 1901–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A.K. , Kumar, S. , Gautam, N. , Gupta, S.K. , Chand, D. , Singh, N.K. and Sharma, T.R. (2009) Cloned rice blast resistance gene Pi‐kh confers broad spectrum resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae . Abstract of the XIV Congress on Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions, 19–23 July 2003, Quebec Canada. International Society of Molecular Plant‐Microbe Interactions, Quebec, Canada.

- Shang, J. , Tao, Y. , Chen, X. , Zou, Y. , Lei, C. , Wang, J. , Li, X. , Zhao, X. , Zhang, M. , Lu, Z. , Xu, J. , Cheng, Z. , Wan, J. and Zhu, L. (2009) Identification of a new rice blast resistance gene, Pid3, by genome‐wide comparison of paired NBS‐LRR genes and their pseudogene alleles between the two sequenced rice genomes. Genetics, 182, 1303–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skamnioti, P. and Gurr, S.J. (2009) Against the grain: safeguarding rice from rice blast disease. Trends Biotechnol. 27, 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suharsono, U. , Fujisawa, Y. , Kawasaki, T. , Iwasaki, Y. , Satoh, H. and Shimamoto, K. (2002) The heterotrimeric G protein alpha subunit acts upstream of the small GTPase Rac in disease resistance of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 13307–13312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweigard, J.A. , Carroll, A.M. , Kang, S. , Farrall, L. , Chumley, F.G. and Valent, B. (1995) Identification, cloning and characterization of Pwl2, a gene for host species‐specificity in the rice blast fungus. Plant Cell, 7, 1221–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai, R. , Isogai, A. , Takayama, S. and Che, F.S. (2008) Analysis of flagellin perception mediated by flg22 receptor OsFLS2 in rice. Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 21, 1635–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura, Y. , Che, F. , Ishida, Y. , TsuTsumi, F. , Kurotani, K.‐I. , Usami, S. , Isogai, A. and Imaseki, H. (2008) Expression of a bacterial flagellin gene triggers plant immune responses and confers disease resistance in transgenic rice plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 525–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thao, N.P. , Chen, L. , Nakashima, A. , Hara, S. , Umemura, K. , Takahashi, A. , Shirasu, K. , Kawasaki, T. and Shimamoto, K. (2007) RAR1 and HSP90 form a complex with Rac/Rop GTPase and function in innate‐immune responses in rice. Plant Cell, 19, 4035–4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharreau, D. , Fudal, I. , Andriantsimialona, D. , Santoso, Utami D. , Fournier, E. , Lebrun, M.‐H. and Nott’eghem, J.‐L. (2009) World population structure and migration of the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae In: Advances in Genetics, Genomics and Control of Rice Blast Disease (Wang G.L. and Valent B., eds), pp. 209–215. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hoorn, R.A.L. and Kamoun, S. (2008) From guard to decoy: a new model for perception of plant pathogen effectors. Plant Cell, 20, 2009–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Variar, M. (2007) Pathogenic variation in Magnaporthe grisea and breeding for blast resistance in India In: Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences Working Report No. 53 (Fukuta Y., Vera Cruz C.M. and Kobayashi N., eds), pp. 87–95. Tsukuba: Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.L. , Mackill, D.J. , Bonman, J.M. , McCoch, S.R. , Champoux, M.C. and Nelson, R.J. (1994) RFLP mapping of genes conferring complete and partial resistance to blast in a durably resistant rice cultivar. Genetics, 136, 1421–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Yano, M. , Yamanouchi, U. , Iwamoto, M. , Monna, L. , Hayasaka, H. , Katayose, Y. and Sasaki, T. (1999) The Pib gene for rice blast resistance belongs to the nucleotide binding and leucine‐rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Plant J. 19, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisser, R.J. , Sun, Q. , Hulbert, S.H. , Kresovich, S. and Nelson, R.J. (2005) Identification and characterization of regions of the rice genome associated with broad‐spectrum, quantitative disease resistance. Genetics, 169, 2277–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, P.J. and Stergiopoulos, I. (2009) Fungal effector proteins. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 233–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.L. , Pinontoan, R. , Hayashi, K. , Tabata, R. , Yaeno, T. , Hasegawa, K. , Kojima, C. , Yoshioka, H. , Iba, K. , Kawasaki, T. and Shimamotoa, K. (2007) Regulation of rice NADPH oxidase by binding of Rac GTPase to its N‐terminal extension. Plant Cell, 19, 4022–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.L. , Fan, Y.Y. , Li, D.B. , Zheng, K.L. , Leung, H. and Zhuang, J.Y. (2005) Genetic control of rice blast resistance in the durably resistant cultivar Gumei 2 against multiple isolates. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111, 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, T. , Zong, N. , Zou, Y. , Wu, Y. , Zhang, J. , Xing, W. , Li, Y. , Tang, X. , Zhu, L. , Chai, J. and Zhou, J.M. (2008) Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto blocks innate immunity by targeting receptor kinases. Curr. Biol. 18, 74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X. , Chen, H. , Fujimura, T. and Kawasaki, S. (2008) Fine mapping of a strong QTL of Weld resistance against rice blast, Pikahei‐1(t), from upland rice Kahei, utilizing a novel resistance evaluation system in the greenhouse. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117, 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.Z. , Lin, F. , Fegn, S.J. , Wang, L. and Pan, Q.H. (2009) Recent progress on molecular mapping and cloning of blast resistance genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Sci. Agric. Sin. 42, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K. , Saitoh, H. , Fujisawa, S. , Kanzaki, H. , Matsumura, H. , Yoshida, K. , Tosa, Y. , Chuma, I. , Takano, Y. , Win, J. , Kamoun, S. and Terauchia, R. (2009) Association genetics reveals three novel avirulence genes from the rice blast fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae . Plant Cell, 21, 1573–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenbayashi, K. , Ashizawa, T. , Tani, T. and Koizumi, S. (2002) Mapping of the QTL (quantitative trait locus) conferring partial resistance to leaf blast in rice cultivar Chubu 32. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104, 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenbayashi‐Sawata, K. , Fukuoka, S. , Katagiri, S. , Fujisawa, M. , Matsumoto, T. , Ashizawa, T. and Koizumi, S. (2007) Genetic and physical mapping of the partial resistance gene, Pi34, to blast in rice. Phytopathology, 97, 598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B. , Qu, S. , Liu, G. , Dolan, M. , Sakai, H. , Lu, G. , Bellizzi, M. and Wang, G.L. (2006) The eight amino‐acid differences within three leucine‐rich repeats between Pi2 and Piz‐t resistance proteins determine the resistance specificity to Magnaporthe grisea . Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 19, 1216–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, E. , Jia, Y. , Singh, P. , Correll, J.C. and Lee, F.N. (2007) Instability of the Magnaporthe oryzae avirulence gene AVR‐Pita alters virulence. Fungal. Genet. Biol. 44, 1024–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]