Abstract

Background

Elucidating networks underlying conscious perception is important to understanding the mechanisms of anesthesia and consciousness. Prior studies have observed changes associated with loss of consciousness primarily using resting paradigms. We focused on the effects of sedation on specific cognitive systems using task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging. We hypothesized deepening sedation would degrade semantic more than perceptual discrimination.

Methods

Discrimination of pure tones and familiar names were studied in 13 volunteers during wakefulness and propofol sedation targeted to light and deep sedation. Contrasts highlighted specific cognitive systems: auditory/motor (tones vs. fixation), phonology (unfamiliar names vs. tones), and semantics (familiar vs. unfamiliar names), and were performed across sedation conditions, followed by region of interest analysis on representative regions.

Results

During light sedation, the spatial extent of auditory/motor activation was similar, becoming restricted to the superior temporal gyrus during deep sedation. Region of interest analysis revealed significant activation in the superior temporal gyrus during light (t(17) = 9.71, p < 0.001) and deep sedation (t(19) = 3.73, p = 0.001). Spatial extent of the phonologic contrast decreased progressively with sedation, with significant activation in the inferior frontal gyrus maintained during light sedation (t(35) = 5.17, p < 0.001), which didn’t meet criteria for significance in deep sedation (t(38) = 2.57, p = 0.014). The semantic contrast showed a similar pattern, with activation in the angular gyrus during light sedation (t(16) = 4.76, p = 0.002), which disappeared in deep sedation (t(18) = 0.35, p = 0.731).

Conclusions

Results illustrate broad impairment in cognitive cortex during sedation, with activation in primary sensory cortex beyond loss of consciousness. These results agree with clinical experience: a dose-dependent reduction of higher cognitive functions during light sedation, despite partial preservation of sensory processes through deep sedation.

Although we are skillful at inducing unconsciousness, we still lack clear understanding of the underlying neurophysiology1. Historically, general mechanisms of loss of consciousness have been elusive because anesthetic agents have diverse, non-overlapping cellular actions2. Developing these theories has been further complicated by the fact that consciousness is a subjective experience, and does not always correlate with loss of responsiveness (the common experimental end-point)3. Early work has emphasized thalamic control4–6, however, subsequent studies suggested that thalamic effects aren’t causal7,8 and are likely a secondary response to widespread cortical suppression9,10. Additionally, although ketamine can induce loss of consciousness, it paradoxically increases thalamic metabolism11. Phenomena like shifting alpha rhythms12 and phase-coupling13 are promising as correlates of loss of consciousness, although these effects have only been demonstrated with GABA-ergic anesthetics and aren’t present using ketamine2, implying that they cannot be generalized to a unified mechanism of consciousness.

A promising correlate of loss of consciousness that is consistent across all known anesthetic agents14,15, sleep16, and coma17 is the disruption of anterior-posterior connectivity from the frontal lobe to the temporal and parietal lobes18. In this model, posterior cortices communicate directly with sensory cortex, whereas anterior frontal regions communicate with sensory cortex indirectly, by communication with posterior regions. The interaction between these regions forms the integrated conscious percept. During anesthesia, top-down activity from frontal regions is reduced in animal and human studies16,19, although local sensory cortex function appears to be preserved18,20. This suggests that a key correlate of loss of consciousness may be disruption of communication to frontal circuits, leading to a loss of information integration across the brain1,18. According to this model, loss of consciousness should occur at a time when higher cortical function is suppressed and sensory cortical function is preserved.

Our goal was to expand previous studies to show progressive changes of cognitive and sensory systems during sedation, using a task-based paradigm. Most prior studies have used resting state paradigms9, with a few notable exceptions21,22. This paradigm has many advantages, particularly when participants are unable to participate in a task. However, it cannot specifically associate particular cognitive processes with particular brain regions. In contrast, task-dependent functional imaging can reveal specific associations of different levels of cognitive processing23. Previous studies using a task-based paradigm have found widespread reductions in activity around loss of consciousness, with persistent activity in the thalamus and primary sensory cortices21,22. We designed the current study using task contrasts chosen to highlight a hierarchy of cognitive systems: basic sensory, phonologic, and semantic processing. We assessed these cognitive systems across different depths of sedation. Specifically, we hypothesized that in light sedation, processing of simple sensory stimuli would be relatively preserved, but more complex semantic and phonological processing would be degraded. At a deeper level of sedation, around the threshold of loss of consciousness, we hypothesized that global communication in the brain would be reduced, leading to reduced activity within cognitive systems, with preservation of activity in sensory cortices.

Materials and Methods

Participants

All participants were right-handed, fluent English speakers and had no significant neurological, cardiovascular, or pulmonary conditions. Participants were specifically excluded for any concern of sleep apnea on history. Of the 16 participants initially enrolled, 1 was excluded prior to scanning because of dental braces, 1 because of initially undisclosed methadone use, and 1 because of reported “throat tightness” at onset of the propofol infusion. Initial sample size was chosen based on previous experience with this task in our lab. The final sample included 13 participants (6 men) with an average age of 28 (range 20 to 37). During the deep sedation segment (detailed below), 2 participants were excluded because of transient apnea events. No significant cardiovascular or respiratory events occurred in any participants. All research was performed under the supervision of the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. No data presented here were previously published.

Tasks

During scanning, participants performed two alternating tasks: Names and Tones. Individual trials were presented in a fast event-related design (with a 3–6 second variable inter-stimulus interval), to allow for deconvolution of mixed trials. To avoid excessive switching, tasks were clustered together in groups of 7 regularly alternating blocks per run. Each block contained 10 foils and 5 targets, presented in a pseudo-randomized order (randomized with the above ISI restrictions). Participants responded on each trial with their right hand using one of two buttons on a magnetic resonance imaging compatible keypad, corresponding to a target or foil stimulus. A visual fixation stimulus was provided throughout, which participants were instructed to fixate.

Stimuli for the Names task consisted of spoken recordings of personally familiar (targets) and unfamiliar proper names (foils). Lists of unfamiliar names were created using automated scripts that pulled complete lists of names from online phonebook listings of the metropolitan area, and randomly sampled complete names from them. Lists of familiar names were collected from each participant several days before scanning, and a subset were recorded using the same voice and recording conditions as the unfamiliar names. Name stimuli were chosen because discriminating familiar from unfamiliar names requires a variety of cognitive processes, including perceptual analysis of the phonemes (consonants and vowels), holding the phonological form briefly in working memory, and retrieving knowledge associated with the name. Familiar names are those for which retrieval of associated semantic and autobiographical knowledge is successful24.

Stimuli for the Tones task consisted of multiple sets of 3–7 pure tones in succession (150ms in duration, separated by 250ms of silence). Each tone was created using one of two frequencies, either high (750 Hz) or low (500 Hz). Targets were defined as a set of tones containing exactly two high tones. Foils were all other combinations of high and low stimuli. Stimulus sets were created with all possible combinations of high and low stimuli, and targets and foils were sampled from these sets.

Sedation protocol

Participants were instructed to fast for 8 hours prior to the study. Participants were placed in the magnetic resonance imaging scanner with compatible pulse oximeter, capnographer, ECG, and blood pressure cuff. Supplemental O2 was delivered throughout by nasal cannula. IV catheters were placed in each antecubital vein for propofol infusion and blood sampling. An attending anesthesiologist was present at all times during sedation.

Participants were scanned in 3 steady-state blocks: prior to receiving propofol (Pre), at a light, responsive level (Low-Propofol) and deep, unresponsive level of sedation (High-Propofol). Each sedation block included two 7.5-minute functional magnetic resonance imaging runs, separated by 1 minute. Each block was initiated by sedating participants using a targeted infusion with predicted venous plasma concentrations of 1 and 2 mcg/ml (respectively) using the STANPUMP program25. Sedation level was then tested clinically using the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation scale prior to beginning each functional magnetic resonance imaging run, and dosing adjustments were made when appropriate. Light sedation was targeted to an Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation score of 3–4 (lethargic to light sleep), while deep sedation was targeted to a score of 1–2 (asleep, arousable with mild stimulation). Based on the clinical decisions of the supervising anesthesiologist, deep sedation was not able to be achieved in all participants (see Figure 1) To verify serum propofol level, venous blood samples were drawn from the non-infusion IV at the beginning of each sedation block, immediately prior to starting the functional magnetic resonance imaging run. Propofol concentration analysis was performed by NMS Labs (Willow Grove, PA) using gas chromatography. Specimens were treated with 70% perchloric acid to disrupt propofol protein binding, and then extracted with isopropyl ether. Quantification was accomplished by capillary gas chromatography using flame ionization detection.

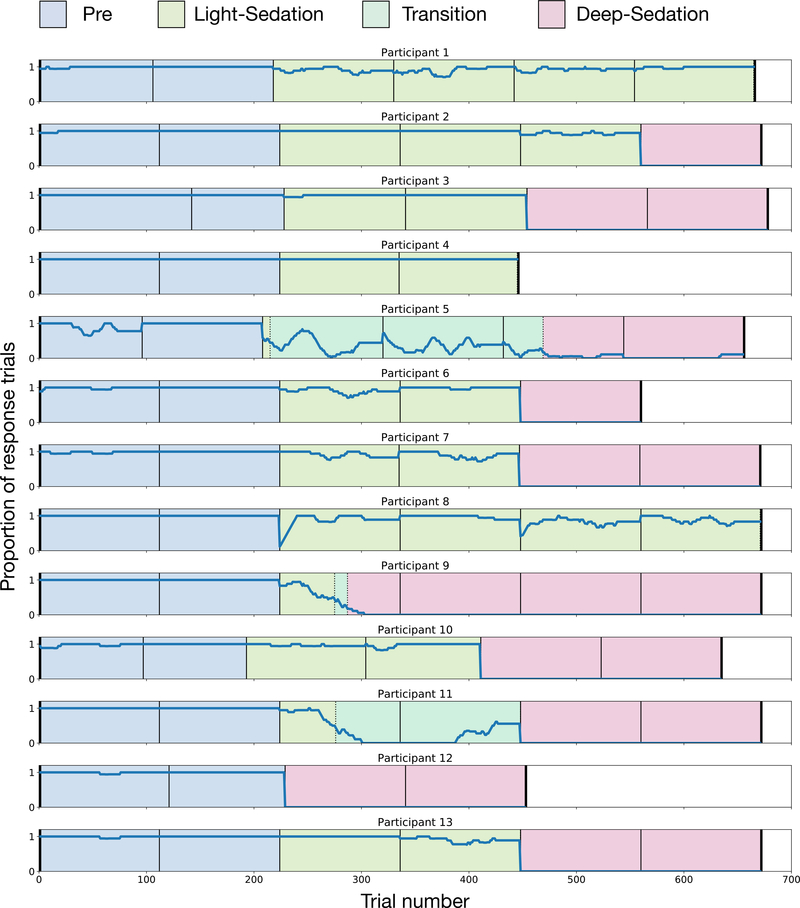

Figure 1.

Moving window (20 trials) of proportion of responses in each participant, along with sedation classifications assigned to the data. Black lines denote functional magnetic resonance imaging run breaks. Blue shading = Pre; green shading = Light-Sedation; teal shading = transitional (not analyzed); red shading = Deep-Sedation.

In order to increase the homogeneity of our sedation conditions, we further classified the data based on task responses into three sedation conditions: Pre, Light-Sedation, and Deep-Sedation. All trials prior to initiating propofol sedation were analyzed in the Pre condition. During the sedation blocks, to quantify responsiveness to external stimuli, we calculated the proportion of responses in a moving window of 20 trials. In the initial time period, while participants were responding to most trials, data were classified as Light-Sedation. To avoid the confound of mixing response and no-responses trials (which could lead to reduced activation simply because of averaging) only response trials were analyzed in this condition. When the moving average response rate (regardless of accuracy) dropped below 50% for 10 trials, the data were classified as in a transitional state. During this time the participants alternated between awake and unconscious states. Because these data were sparse and not stable, it was excluded from analysis. After participants’ response rate dropped below 20% for 10 trials, they were classified as Deep-Sedation. Again, to avoid averaging heterogenous trials together, only non-responses were analyzed in the Deep-Sedation condition. Data were classified on a single-trial level, resulting in blocks of time that could include partial functional magnetic resonance imaging runs (e.g., if a participant stopped responding in the middle of the run). The response rates and classifications of each individual participant is shown in Figure 1.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging scanning and processing

Scans were performed on a 3 tesla General Electric Excite 750 scanner with a 32-channel head coil. High-resolution anatomical images were acquired using a Spoiled Gradient Recalled Acquisition in Steady State sequence. Functional images were obtained using an echo planar imaging sequence with repetition time of 2 seconds, echo time of 25 milliseconds, and 3.5 millimeter isotropic voxels using 41 axial slices.

Imaging data were processed using the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages software suite26. Echo planar images were slice time-corrected and rigid body-aligned, and time points with excessive motion were censored. A 2 millimeter Gaussian kernel spatial smoothing was applied to the raw data, and parameter estimation was performed using a deconvolution procedure. The deconvolution model was created using a gamma variate convolved with the stimulus time series in a fast event-related manner.

Statistical analyses

The deconvolution model in each subject consisted of the gamma variate convolved time series of each stimulus, for each sedation condition. Additionally, a 10th order Legendre polynomial to account for low-frequency signal changes and motion parameters derived from the rigid body alignment were included as covariates. Trials that were not analyzed (i.e., no-response trials during Light-Sedation or response trials during Deep-Sedation) were also coded as a separate covariate of non-interest. Data points were excluded from analysis using the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages tool 3dToutcount if more than 5% of voxels within the brain volume were classified as outliers (defined as having an α<0.001 based on fitting a Gaussian distribution to the data).

To illustrate effects associated with processing at three distinct cognitive levels, the following hierarchical a priori task contrasts were designed. To identify basic auditory and motor response processing in the absence of deep semantic processing, all tone trials were compared to the inter-stimulus baseline (AudMotor contrast). Unfamiliar names were then contrasted with the tone stimuli (Phonologic contrast) to identify the additional processing necessary for perceiving speech stimuli with minimal semantic content. Finally, familiar names were contrasted with unfamiliar names (Semantic contrast) to specifically isolate processing of semantic knowledge. Each of these contrasts were performed on data from the three sedation conditions. Task contrast maps were calculated for each sedation condition by performing voxel-wise t-tests using the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages program 3dttest++ on the corresponding stimulus coefficients for each of the pre-planned task contrasts.

These task contrast maps were directly tested in a voxel-wise 2-way fixed-effects repeated measures ANOVA of the difference in contrast coefficients, with sedation level and task contrast as factors, using the R statistical package27. The effect of interest was the interaction between sedation level and task contrast, which reveals regions where the effect of sedation was different across the task contrasts. These interaction effects were then further clarified using the average activity in significant clusters located within regions of interest, chosen a priori to be representative of the auditory, phonologic, and semantic systems. Activity in each of these three regions was contrasted using post-hoc t-tests, which included testing both names and tones in each sedation condition to baseline (18 tests total), along with the specific Phonologic (names vs. tones) and Semantic (familiar vs. unfamiliar names) in each sedation condition (an additional 6 test). This resulted in 24 post-hoc comparisons. Effects were considered significant with a two-tailed p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected to p < 0.002. Because data points were assigned to sedation conditions based on the previously described behavioral criteria, the number of data points per condition was not equal.

All functional maps were thresholded at an individual voxel p < 0.005, two-tailed, with a minimum cluster size of 463 cubic millimeters (all displayed figures are thresholded using this level). This threshold was derived from Monte Carlo simulations using the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages program 3dClustSim with a mixed model (Gaussian plus monoexponential) spatial autocorrelation function derived from the measured smoothness of residual datasets. This model has recently been improved in response to criticism of previous functional magnetic resonance imaging clustering models28,29. All behavioral data were analyzed using the R statistical package27.

Results

Behavioral results

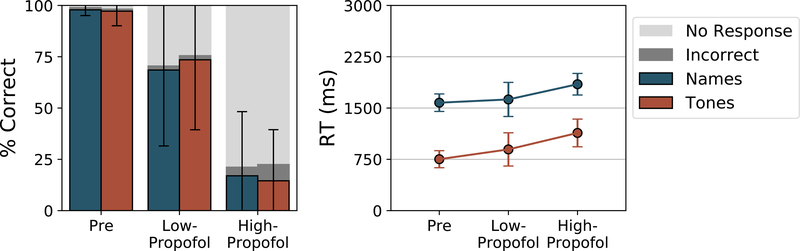

Shown in Figure 2 are the accuracy (bars) and reaction times (lines) of responses in each of the functional magnetic resonance imaging blocks. Missed responses were excluded from reaction time calculation. Before sedation, accuracy on both tasks was nearly perfect (names 97.8%; tones 97.2%) with an average reaction time of 1578 milliseconds and 752 milliseconds for the names and tones respectively. During the Low- and High-Propofol blocks, accuracy progressively declined (F(2,68) = 63.17, p < 0.001) and reaction time lengthened (F(2,52) = 4.61, p = 0.014). As seen when comparing the “Incorrect” (dark gray) and “No response” (light gray) bars, the majority of this performance drop was due to failing to respond rather than incorrect responses, as during the High-Propofol block, most participants were almost completely unresponsive to the task.

Figure 2.

Accuracy and reaction time to the perceptual and semantic tasks across levels of sedation. Accuracy decreased (due to increasing missed responses) while reaction times increased under deep levels of sedation.

Measured serum propofol concentrations and Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation scores prior to each scanning run are shown in Table 1. Relative to the serum concentration goals, the measured serum propofol concentrations were significantly lower in the Low-Propofol (t(10) = 12.99, p<0.001) and High-Propofol (t(8) = 4.11, p<0.005) blocks. In contrast, the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation clinical sedation assessment scores were in line with our targets (as expected, since sedation was titrated to the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation targets).

Table 1.

Measured serum propofol levels and OAA/S scores prior to each scanning block.

| Low-Prop | High-Prop | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Propofol | Goal | 1.00 | 2.00 |

| Measured | 0.53 ± 0.12 * | 1.52 ± 0.35 * | |

| OAA/S | Goal | 3 – 4 | 1 – 2 |

| Measured | 4 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

“±” denotes standard deviation

denotes p<0.01 on one-sample t-test comparing measured to goal levels.

Basic perceptual task contrast

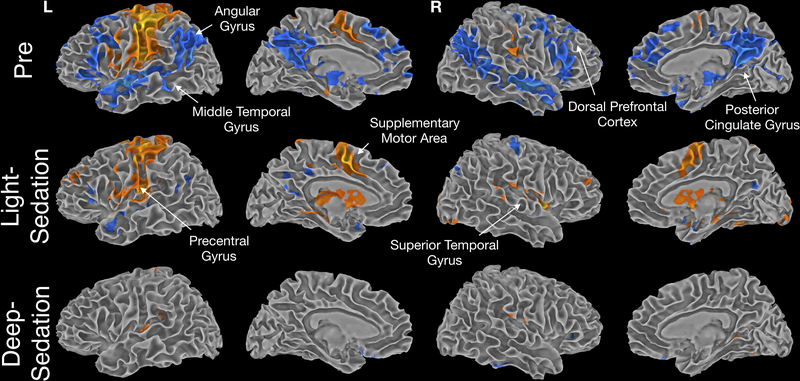

To illustrate progressive changes of the cognitive and perceptual systems, each of the previously specified task contrasts was performed in each sedation condition. Shown in Figure 3 is the AudMotor contrast of Tones versus baseline across the different sedation conditions. Before sedation, activation was observed during the Tones task in primary and secondary auditory and motor cortices, and somatosensory cortex. Motor and somatosensory activation was strongly left-lateralized, consistent with performance of the task response with the right hand. Increased activation during the fixation periods between trials (blue color) was observed in a widespread network linked with semantic and “default mode” processing 30, including the angular gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, medial and dorsal prefrontal cortex, and posterior cingulate gyrus. This pattern of activation has been observed previously using this task, and is hypothesized to reflect non-task related mental processing (“task-unrelated thoughts”, “mind wandering”) during short pauses in the task31,32.

Figure 3.

Contrast of activation to tones vs. baseline across levels of sedation. Activation to tones primarily (in orange) was centered around motor and sensory systems. Activation during baseline (in blue) highlights semantic processing in between task events.

During the Light-Sedation condition, regions where activation increased during fixation (hypothesized to be associated with off-task processing) were markedly attenuated, whereas activity in auditory, motor, and somatosensory cortices exhibited a similar spatial extent. The marked decrease in inter-stimulus activation suggests that the off-task processes underlying this activation are highly sensitive to disruption by sedation.

In the Deep-Sedation condition, when participants were not responsive to external stimuli, motor activation disappeared, along with activation in temporal lobe auditory association areas. Notably, even under deep sedation the tone stimuli continued to evoke activation in primary auditory cortex, in the superior temporal gyrus.

Hierarchical task contrasts

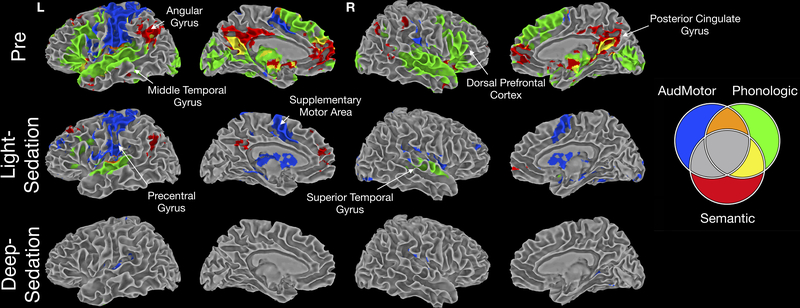

Figure 4 illustrates a composite of the three hierarchical contrasts. AudMotor, shown in blue (the positive component of Figure 3), highlights lower-level auditory and sensorimotor processing. The Phonologic contrast in green highlights additional regions involved in processing unfamiliar names, including large regions of the superior temporal and inferior frontal lobes. A small area of overlap of these processes (highlighted in orange) can be seen in the superior temporal gyrus, consistent with previous findings that speech sounds activate the superior temporal gyrus more than tones33. The Semantic contrast (highlighted in red) shows the additional processing for familiar names, with areas in yellow showing the overlap between the Semantic and Phonologic contrasts. It is also interesting to note that the de-activations seen in the AudMotor contrast follow a similar pattern to the phonologic and semantic contrasts, supporting their role in off-task processing, as we have previously demonstrated31.

Figure 4.

Combination of the three task contrasts, designated by color, to illustrate relative overlap. Blue: AudMotor, green: Phoneme, red: Semantic; orange: AudMotor+ Phoneme, yellow: Phoneme+ Semantic.

In the Light-Sedation condition, almost all semantic activity disappeared, except for small foci in the left angular and bilateral posterior cingulate gyri. Most of the Phonologic contrast differences also disappeared in regions related to higher-order language processing, with activation maintained mainly in secondary auditory cortex and a small region of left posterior inferior frontal cortex. In contrast, as described above, the extent of activation for the AudMotor contrast was not substantially affected. In the Deep-Sedation condition, all activity in the Phonologic and Semantic contrasts was completely abolished. As shown in Figure 3, activity in the primary auditory and inferior parietal cortex was maintained in the AudMotor contrast.

Voxel-wise comparison of sedation conditions

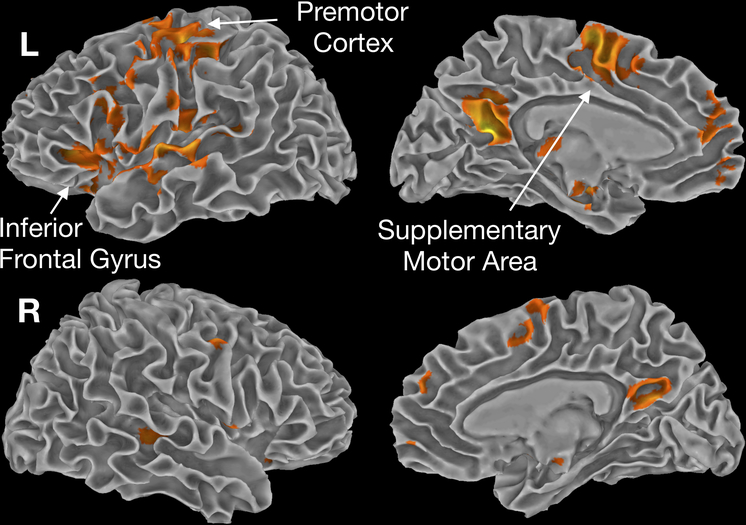

The differences in these task contrasts across sedation levels was then tested using a 2-way ANOVA. The main effect of sedation condition is shown in Figure 5, illustrating regions where activity was reduced in all task contrasts across sedations conditions. Most the clusters shown here, including within the inferior frontal gyrus, temporal lobe, and posterior cingulate gyri, are driven by the interaction effects described in the next section. In contrast, clusters within the premotor area and supplementary motor area exhibited a global reduction across tasks with sedation, being abolished in the Deep-Sedation condition. This was expected, as behavioral responses were also lost in this condition.

Figure 5.

Main effect of sedation level across all task contrasts. Regions in the motor (supplementary motor area, premotor cortex), auditory and phonological (superior temporal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus), and semantic (posterior cingulate, precuneus), all showed consistent reduction in activation across all task contrasts with increasing sedation.

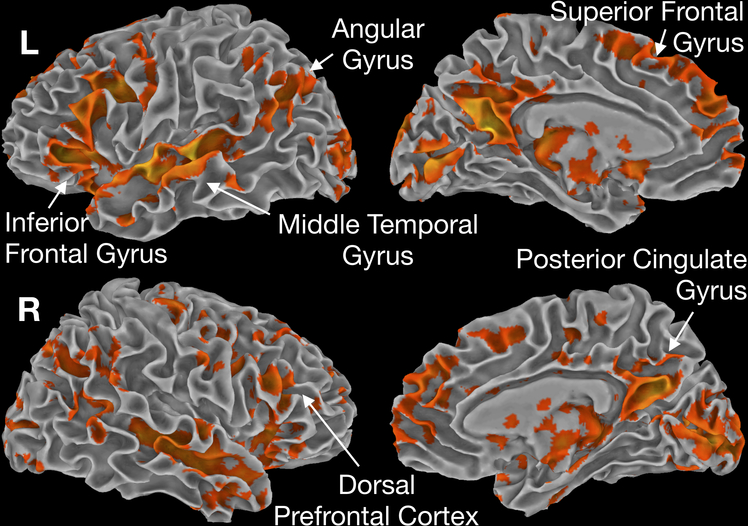

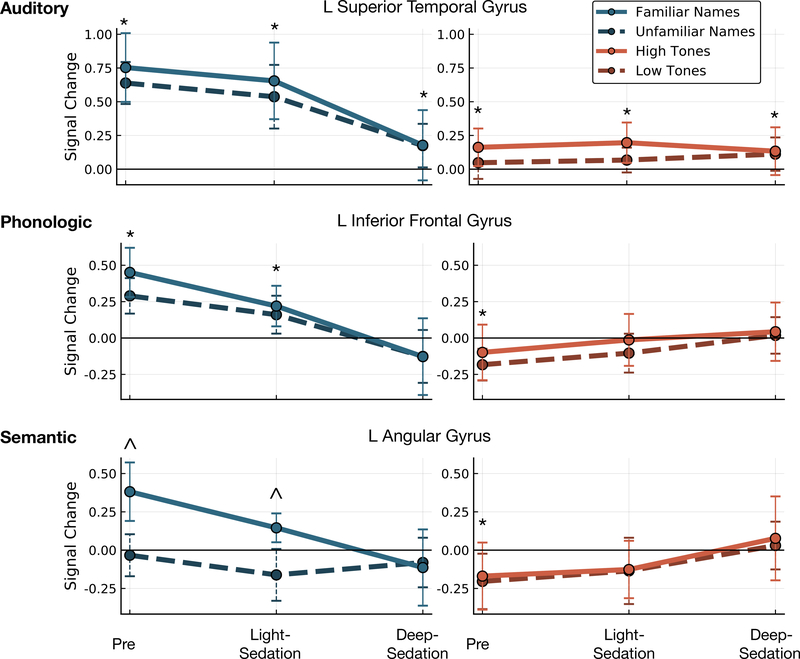

Regions with significant interactions across sedation by task contrast are shown in Figure 6. To further elucidate these effects, the average activity within significant clusters in a priori chosen regions, representative of the three task contrasts, is shown in Figure 7. Activation within the primary auditory cortex was significantly greater for Names versus Tones in the Pre condition (t(50) = 11.75, p < 0.001). In the Light-Sedation condition this effect remained significant (t(35) = 6.90, p < 0.001) disappearing in Deep-Sedation (t(38) = 0.93, p = 0.360). Although (as demonstrated above in Figure 3) significant activation significantly greater than fixation was still seen in both Tones stimuli during the Deep-Sedation condition (t(19) = 3.676, p = 0.002).

Figure 6.

Interaction effect of task contrast by sedation level. Sedation had different effects on task contrasts in most of the regions studied (detailed in the region of interest analysis in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Average activity within regions of interest derived from the voxel-wise interaction of task contrast by sedation level. Activity in auditory cortex diminished with sedation, but remained active under deep sedation. Phonologic and semantic effects were reduced in light sedation, and were not detected in deep sedation. Regions with activity significantly different than zero (p<0.002) are denoted with ‘*’; regions with significant differences between foil and target stimuli (p<0.002) are denoted with ‘^’. Error bars denote standard error of the mean.

Phonological regions, including the inferior frontal gyrus and posterior portions of the superior and middle temporal gyrus, displayed a similar pattern of activation across sedation. Consistent with their posited role in phonology, significant activation was seen for Names over Tones in the Pre condition (t(50) = 11.36, p < 0.001) and during Light-Sedation (t(35) = 5.17, p < 0.001), with no difference observed in Deep-Sedation (t(38)=2.57, p = 0.014). As stated above, prior to sedation negative activation was observed in these regions during the Tones task (t(25) = 4.54, p < 0.001). This difference disappeared in the Light-Sedation (t(35) = 1.67, p = 0.113) and Deep-Sedation (t(18) = 0.84, p = 0.412) conditions.

In semantic regions, including the angular gyrus and posterior cingulate, a significant increase in activation was seen during the Pre condition for familiar versus non-familiar names (t(24) = 6.36, p < 0.001), which persisted during Light-Sedation (t(16) = 4.76, p = 0.002), and disappeared in Deep-Sedation (t(18) = 0.35, p = 0.731). As seen in phonologic regions, negative off-task activation was present in the Pre condition for tones (t(25) = 4.82, p < 0.001), which disappeared in the Light-Sedation (t(18) = 2.89, p = 0.010), and Deep-Sedation (t(38) = 1.10, p = 0.287) conditions.

Discussion

In this paper we examined in detail the progressive disruption of function across multiple processing domains during increasing depths of sedation. As predicted, activation in higher cognitive areas (semantic and phonological processing) is mostly abolished under deep sedation, whereas activation related to lower sensory processing continues. This is consistent with previous studies that suggest initial bottom-up processing is maintained under anesthetic conditions, while top-down processing is disrupted18,20,34,35. This was further demonstrated by Massimini16 using transcranial magnetic stimulation pulses during awake and anesthetized states. In the awake state, electroencephalography recorded activity after a transcranial magnetic stimulation pulse showed a sequence of multiple potentials from different cortical sources. Under deep anesthesia, although later downstream effects were not observed, the initial potential deflection coming from the primary sensory cortex was preserved.

Under light sedation, semantic and phonological processes were both partially suppressed, with a large reduction in activation extent, although activity attributable to semantic processing was still detectable in the region of interest analysis. In primary auditory cortex, the extent of activation was similar in light sedation, although the magnitude of activation was decreased. Consistent with our predictions, significant activity in primary perceptual cortex continued even under deep sedation conditions. Although we commonly observe that complex behavioral task performance is impaired during sedation, these data illustrate that in light sedation conditions some activity attributable to semantic processing remains. These behavioral effects may be due to disruption of long-range connectivity to these higher cortices (as mentioned above), or due to a degradation in the information and processing fidelity within these regions.

Consistent with many previous observations31,32, our non-semantic tones task elicited “deactivations” in many regions, attributed to the subtraction of positive activations occurring during the short rest periods, associated with off-task processing when cognitive loads are low. Interestingly, in the light sedation condition, most of this activation was suppressed. The high sensitivity of this internal “mind wandering” activity to light sedation is consistent with evidence that it is a complex brain function dependent on a distributed network of high-level “hubs”30,36. According to one broadly accepted view, the main purpose of this brain activity is to support planning during intervals when there are no external stimuli that demand attention31,36,37. We speculate that the global dysfunction incurred by sedation leads to suspension of these non-essential planning processes, and prioritization of cognitive resources (attention, effort, working memory, etc.) to external task demands.

The general effects demonstrated here are also in line with the common clinical experience with patients during sedation. Gross observation reveals that light sedation is characterized by degradation of performance in higher cognitive functions, including the early loss of some episodic memory encoding. The loss of signal propagation under sedation observed here may underlie this state, in which patients are able to process simple stimuli, but integrative functions and complex knowledge retrieval are degraded. As anesthesia is deepened, patients reach a level where all complex processing is abolished, and only stereotypical responses to stimuli are observed.

Although our data suggest that some brain regions (e.g., primary auditory cortex) are active at loss of consciousness and reactive to external stimuli, it is important to recognize some caveats before applying this concept to clinical contexts. Although the auditory cortex was active even after loss of consciousness, this does not imply that during standard clinical procedures patients can “hear” their surroundings (i.e., have conscious auditory perception after loss of responsiveness). As the objective measurement of consciousness used here is responsiveness, we cannot speak to whether conscious perception occurred independent of responsiveness. The reduction in phonological and semantic processing does suggest that minimal complex processing occurred during deep sedation. Also, the level of sedation used was titrated specifically to loss of consciousness. Using a standard general anesthetic, with surgical levels of sedation, the cortex is likely substantially more depressed38, with expected further depression of both task reactivity and functional connectivity.

In summary, propofol sedation impaired cognitive task performance together with a decrease in fronto-temporal-parietal functional activation involved in phonologic perception and semantic retrieval, while auditory-motor cortex activation to simple tone stimuli was more resistant to sedation. Lighter levels of sedation caused disruption of processing on multiple levels, although differential activity was observed even in higher cognitive regions. These results suggest that the performance of phonologic-semantic cognitive tasks is linked to the intact functioning of higher-order association regions, which are diminished during sedation. They agree with clinical experience in patients, implying the dose-dependent loss of higher cognitive functions despite partial preservation of low-level sensory analysis.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings presented here. As shown by the behavioral data, clinical responses to similar doses of propofol were more variable than expected. Although we attempted to standardize this using behavioral measurements, some variability likely remains. Similarly, although we targeted periods of steady-state propofol, the sedation level may have changed slowly during functional magnetic resonance imaging scans, contributing to additional variability. In addition, although we have demonstrated effects correlated with sedation, we cannot specifically attribute changes in brain activity to direct effects of propofol. Alternatively, sedation may disrupt task performance on a lower level, with the effects seen in higher cortices only subsequent indirect effects.

Future studies may be able to further detail the dynamics of cognitive function through sedation using more complex natural or multisensory stimuli or comparing the effect of pharmacologically diverse anesthetic agents. Observing brain activity at multiple levels of light sedation may also assist in separating effects of sedation on different cognitive systems.

Acknowledgments:

The STANPUMP program used for our propofol infusion is freely available from the OpenTCI initiative at http://opentci.org/code/stanpump.

Funding Statement: Research reported in this publication was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01 GM103894 and T32 GM89586.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial: Not applicable

Prior Presentations: Partial results presented at ASA Conference, San Diego, Oct 25, 2015

Summary Statement: Not applicable

References

- 1.Mashour GA: Top-down mechanisms of anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Front Syst Neurosci 2014; 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blain-Moraes S, Lee U, Ku S, Noh G, Mashour GA: Electroencephalographic effects of ketamine on power, cross-frequency coupling, and connectivity in the alpha bandwidth. Front Syst Neurosci 2014; 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders RD, Tononi G, Laureys S, Sleigh JW: Unresponsiveness ≠ unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:946–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White NS, Alkire MT: Impaired thalamocortical connectivity in humans during general-anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. NeuroImage 2003; 19:402–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkire MT, Haier RJ, Fallon JH: Toward a unified theory of narcosis: brain imaging evidence for a thalamocortical switch as the neurophysiologic basis of anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Conscious Cogn 2000; 9:370–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiset P, Paus T, Daloze T, Plourde G, Meuret P, Bonhomme V, Hajj-Ali N, Backman SB, Evans AC: Brain mechanisms of propofol-induced loss of consciousness in humans: a positron emission tomographic study. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 1999; 19:5506–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raz A, Grady SM, Krause BM, Uhlrich DJ, Manning KA, Banks MI: Preferential effect of isoflurane on top-down vs. bottom-up pathways in sensory cortex. Front Syst Neurosci 2014; 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velly LJ, Rey MF, Bruder NJ, Gouvitsos FA, Witjas T, Regis JM, Peragut JC, Gouin FM: Differential Dynamic of Action on Cortical and Subcortical Structures of Anesthetic Agents during Induction of Anesthesia. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 2007; 107:202–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song X, Yu B: Anesthetic effects of propofol in the healthy human brain: functional imaging evidence. J Anesth 2015; 29:279–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veselis RA, Reinsel RA, Feshchenko VA, Dnistrian AM: A neuroanatomical construct for the amnesic effects of propofol. Anesthesiology 2002; 97:329–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Långsjö JW, Maksimow A, Salmi E, Kaisti K, Aalto S, Oikonen V, Hinkka S, Aantaa R, Sipilä H, Viljanen T, Parkkola R, Scheinin H: S-ketamine anesthesia increases cerebral blood flow in excess of the metabolic needs in humans. Anesthesiology 2005; 103:258–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feshchenko VA, Veselis RA, Reinsel RA: Propofol-Induced Alpha Rhythm. Neuropsychobiology 2004; 50:257–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukamel EA, Pirondini E, Babadi B, Wong KFK, Pierce ET, Harrell PG, Walsh JL, Salazar-Gomez AF, Cash SS, Eskandar EN, Weiner VS, Brown EN, Purdon PL: A Transition in Brain State during Propofol-Induced Unconsciousness. J Neurosci 2014; 34:839–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudetz AG, Mashour GA: Disconnecting Consciousness: Is There a Common Anesthetic End Point? Anesth Analg 2016; 123:1228–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee U, Ku S, Noh G, Baek S, Choi B, Mashour GA: Disruption of Frontal–Parietal Communication by Ketamine, Propofol, and Sevoflurane. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 2013; 118:1264–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massimini M, Ferrarelli F, Huber R, Esser SK, Singh H, Tononi G: Breakdown of Cortical Effective Connectivity During Sleep. Science 2005; 309:2228–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boly M, Garrido MI, Gosseries O, Bruno M-A, Boveroux P, Schnakers C, Massimini M, Litvak V, Laureys S, Friston K: Preserved Feedforward But Impaired Top-Down Processes in the Vegetative State. Science 2011; 332:858–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan D, Ilg R, Riedl V, Schorer A, Grimberg S, Neufang S, Omerovic A, Berger S, Untergehrer G, Preibisch C, Schulz E, Schuster T, Schröter M, Spoormaker V, Zimmer C, Hemmer B, Wohlschläger A, Kochs EF, Schneider G: Simultaneous electroencephalographic and functional magnetic resonance imaging indicate impaired cortical top-down processing in association with anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2013; 119:1031–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imas OA, Ropella KM, Ward BD, Wood JD, Hudetz AG: Volatile anesthetics disrupt frontal-posterior recurrent information transfer at gamma frequencies in rat. Neurosci Lett 2005; 387:145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veselis RA, Feshchenko VA, Reinsel RA, Beattie B, Akhurst TJ: Propofol and thiopental do not interfere with regional cerebral blood flow response at sedative concentrations. Anesthesiology 2005; 102:26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mhuircheartaigh RN, Warnaby C, Rogers R, Jbabdi S, Tracey I: Slow-Wave Activity Saturation and Thalamocortical Isolation During Propofol Anesthesia in Humans. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5:208ra148–208ra148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warnaby CE, Seretny M, Ní Mhuircheartaigh R, Rogers R, Jbabdi S, Sleigh J, Tracey I: Anesthesia-induced Suppression of Human Dorsal Anterior Insula Responsivity at Loss of Volitional Behavioral Response. Anesthesiology 2016; 124:766–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, Davis MH, Laureys S, Pickard JD: Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. Science 2006; 313:1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugiura M, Sassa Y, Watanabe J, Akitsuki Y, Maeda Y, Matsue Y, Fukuda H, Kawashima R: Cortical mechanisms of person representation: recognition of famous and personally familiar names. NeuroImage 2006; 31:853–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shafer A, Doze VA, Shafer SL, White PF: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of propofol infusions during general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1988; 69:348–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox RW: AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res Int J 1996; 29:162–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018. at <https://www.R-project.org/> [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox RW, Reynolds RC, Taylor PA: AFNI and Clustering: False Positive Rates Redux. bioRxiv 2016:065862 doi: 10.1101/065862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H: Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016; 113:7900–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binder JR, Desai RH, Graves WW, Conant LL: Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex N Y N 1991 2009; 19:2767–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Rao SM, Cox RW: Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state. A functional MRI study. J Cogn Neurosci 1999; 11:80–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKiernan KA, D’Angelo BR, Kaufman JN, Binder JR: Interrupting the “stream of consciousness”: An fMRI investigation. NeuroImage 2006; 29:1185–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Springer JA, Kaufman JN, Possing ET: Human temporal lobe activation by speech and nonspeech sounds. Cereb Cortex N Y N 1991 2000; 10:512–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boveroux P, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Bruno M-A, Noirhomme Q, Lauwick S, Luxen A, Degueldre C, Plenevaux A, Schnakers C, Phillips C, Brichant J-F, Bonhomme V, Maquet P, Greicius MD, Laureys S, Boly M: Breakdown of within- and between-network resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging connectivity during propofol-induced loss of consciousness. Anesthesiology 2010; 113:1038–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu X, Lauer KK, Ward BD, Rao SM, Li S-J, Hudetz AG: Propofol disrupts functional interactions between sensory and high-order processing of auditory verbal memory. Hum Brain Mapp 2012; 33:2487–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews-Hanna JR: The Brain’s Default Network and Its Adaptive Role in Internal Mentation. The Neuroscientist 2012; 18:251–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL: Episodic simulation of future events: concepts, data, and applications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1124:39–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palanca BJA, Avidan MS, Mashour GA: Human neural correlates of sevoflurane-induced unconsciousness. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119:573–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]