Abstract

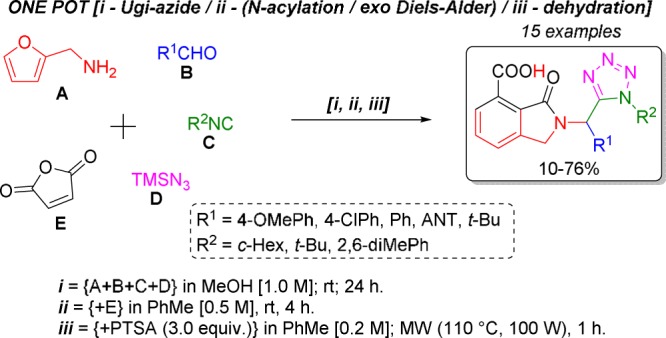

A series of fifteen 2-tetrazolylmethyl-isoindolin-1-one linked-type bis-heterocycles were synthesized in 10–76% yields under mild conditions via a one-pot Ugi-azide/(N-acylation/exo-Diels–Alder)/dehydration process from furan-2-ylmethanamine, aldehydes, isocyanides, azidotrimethylsilane, and maleic anhydride. Density functional theory calculations were performed using the polarizable continuum model (toluene)-M06-2X-D3/6-311+G(d)//M06-2X-D3/6-31G(d) level of theory to obtain the full energy profile when investigating over eight possible pathways. An anthracene-containing analogue displayed a distribution of its highest occupied molecular orbital–lowest unoccupied molecular orbital throughout both cyclic moieties.

Introduction

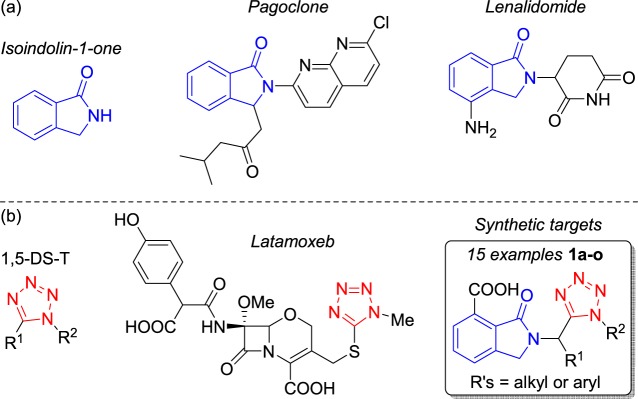

Isoindolin-1-one (oxoisoindoline) is the core of various natural and synthetic drugs,1 for example, pagoclone (antianxiolytic)2 and lenalidomide (anticancer)3 (Figure 1a). Additionally, 1,5-disubstituted tetrazoles (1,5-DS-T) are bioisosteres of the cis-amide bond of peptides,4,5 which are present in various drugs,6 such as latamoxeb (antibiotic)7 (Figure 1b). Moreover, 1,5-DS-T’s have been used as MOF precursors, ligands, and chelating agents.8

Figure 1.

Isoinsolin-1-one- and 1,5-DS-T-containing bioactive products.

There are reports describing the multistep synthesis of isoindolin-1-ones, in which the key process was a cyclization to construct their five-membered rings.9−12 Moreover, there is a multistep method for the synthesis of various (±)-nuevamine-like alkaloids, in which the benzene ring of isoindolin-1-one was synthesized via intermolecular Diels–Alder (DA) cycloaddition using maleic anhydride as a dienophile.13 On the other hand, multicomponent reaction (MCR)-based methodologies for the synthesis of a series of isoindolin-1-ones have been reported.14−16 In addition, there are four reports describing the synthesis of isoindolin-1-ones via one-pot (MCR/intramolecular DA cycloaddition) processes.17−20 However, in all of these reports, the substituents (decoration) of isoindolin-1-ones are structurally simple (alkyl or aryl groups). Besides, there are only two reported methods describing MCR one-pot synthesis of isoindolin-1-ones N-bound (not N-linked) with other heterocyclic systems.21,22

1,5-DS-T’s are synthesized via click reactions using organic azides and nitriles as starting reagents.23 Besides, the Ugi-azide reaction is the current strategy to synthesize 1,5-DS-T’s with a structural variety of substituents,24 for example, alkyl, aryl, benzyl, allyl, and propargyl, and has been less explored with heterocycles in a fused, linked, merged, or bound manner.25 There are only two reported methods describing MCR one-pot synthesis of bis-heterocycles containing a 1,5-DS-T core C-linked with other heterocycles.26,27 In this context, we have recently reported MCR one-pot methods for the synthesis of a series of novel 1,5-DT’s linked with a variety of heterocyclic moieties.28−31

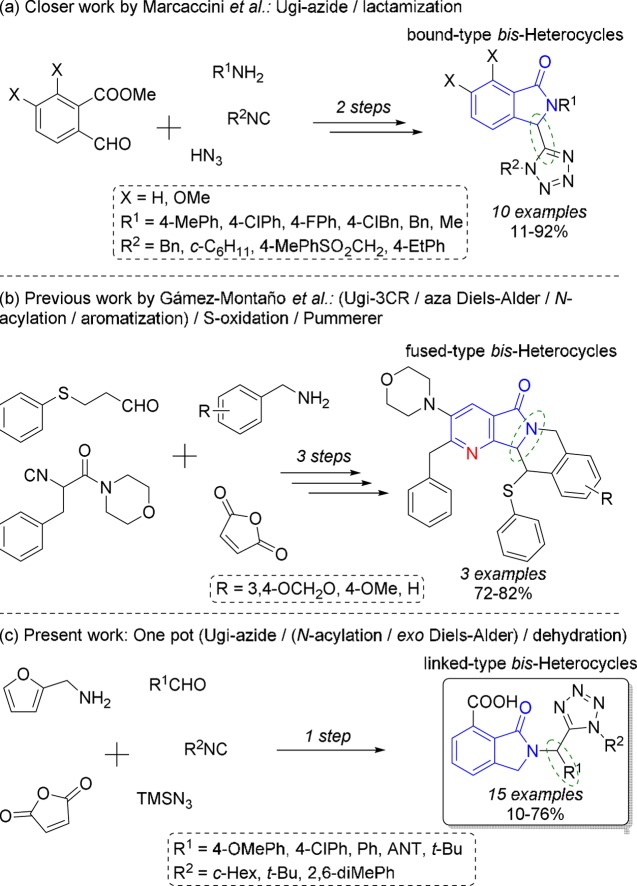

There are no reports describing the synthesis of unsymmetrical bis-heterocycles containing an isoindolin-1-one core N-linked with 1,5-DS-T’s using MCR one-pot methodologies or multistep methods. However, Marcaccini reported the synthesis of bis-heterocycles having an isoindolin-1-one core bound with 1,5-DS-T’s, but at the C-3 position, using a two-step Ugi-azide/lactamization process (Scheme 1a).32 Besides, we reported the synthesis of fused-type bis-heterocycles tetrahydroisoquinolin-pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-ones (aza-analogues of isoindolin-1-ones) by a three-step (Ugi-3CR/aza DA/N-acylation/aromatization)/S-oxidation/Pummerer process (Scheme 1b).33 Thus, we now describe, for the first time, MCR one-pot synthesis of 2-tetrazolylmethyl-isoindolin-1-ones N-linked with a 1,5-DS-T moiety (Scheme 1c), as well as density functional theory (DFT)-based computational calculations to propose the most plausible reaction mechanism. As will be discussed, we synthesized novel bis-heterocycles using a new combination of known reactions, that is, the Ugi-azide reaction,34 DA cycloaddition (from furan derivatives),35 and aromatization (from oxa-bridged intermediates).36−39 It is noteworthy that Ivar Ugi, Emmanuel Gras, and Jieping Zhu are the pioneers behind these processes, respectively.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Strategies.

Results and Discussion

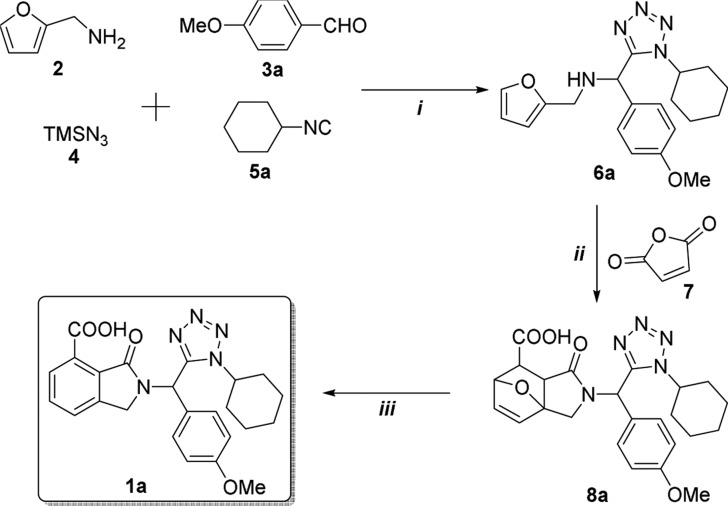

2-((1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic acid (1a) was selected as a model for screening reaction conditions (Table 1). Thus, equimolar amounts of furan-2-ylmethanamine (2), p-anisaldehyde (3a), azidotrimethylsilane (4), and cyclohexyl isocyanide (5a) were combined sequentially under the Ugi-azide standard conditions (MeOH [1.0 M], room temperature (rt)) as the starting point. Ugi-azide product 6a was synthesized in 99% yield after 24 h (entry 1, Table 1). Then, to avoid the use of a solvent because the majority of the reagents are liquids, the reaction was performed under neat conditions. The yield decreased dramatically to 22% after 24 h (entry 2, Table 1). To reduce the reaction time, two further experiments were conducted at 65 °C under conventional or microwave (MW) heating conditions, but the yields obtained were 84% (1 h) and 88% (0.2 h), respectively (entries 3 and 4, Table 1). Finally, an experiment was performed using ultrasound (US) irradiation (sonication), providing a yield of 90% after 2 h (entry 5, Table 1). Then, we performed an intermolecular DA cycloaddition at rt using equimolar amounts of the Ugi-azide product, 6a, and maleic anhydride (7) in anhydrous PhMe as a solvent. Compound 8a was synthesized first in 60% yield after 4 h (entry 6, Table 1). A further experiment was performed increasing the amount of 7 to 1.5 equiv, producing 87% yield after 4 h (entry 7, Table 1). Two further experiments were performed at 110 °C under conventional or MW heating conditions,40 but the yields obtained decreased to 68% (1 h) and 65% (0.2 h), respectively (entries 8 and 9, Table 1). A final experiment was performed using US, producing a yield of 72% in 1 h (entry 10, Table 1). To aromatize the six-membered ring, compound 8a was heated in acidic media.41 Thus, an aqueous solution of compound 8a in H3PO4 [85%] was refluxed, but the bis-heterocycle, 1a, could not been synthesized (entry 11, Table 1). In fact, decomposition was observed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Then, the aromatization process was performed at 110 °C using PhMe as a solvent and 1.0 equiv of p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA), producing a yield of 18% after 12 h (entry 12, Table 1). Four additional experiments were conducted using MW as a heat source by varying the amount of PTSA. The yields were 25% (1.0 equiv 7), 50% (2.0 equiv 7), 76% (3.0 equiv 7), and 72% (4.0 equiv 7; entries 13–16, Table 1). A further experiment was performed using US, but the yield decreased to 62% (entry 17, Table 1). Thus, entries 1, 7, and 15 of Table 1 show the optimal conditions for the three processes. At this point, we hypothesized that product 1a could be synthesized coupling the three processes in a one-pot manner. Thus, 1a was synthesized in 53% overall yield after 29 h (entry 18, Table 1). A further experiment was conducted using US at 60 °C in a one-pot manner. However, the last step (8a → 1a) did not proceed. As seen, US works well stepwise but not in the one-pot process.

Table 1. Screening Conditions.

| entry | conditions | T (°C) | t (h) | yieldc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | ||||

| 1 | MeOH [1.0 M] | rt | 24 | 6a (99)d |

| 2 | neat | rt | 24 | 6a (22) |

| 3 | MeOH [1.0 M] | 65 | 1 | 6a (84) |

| 4 | MeOH [1.0 M] | 65a | 0.2 | 6a (88) |

| 5 | MeOH [1.0 M] | rtb | 2 | 6a (90) |

| ii | ||||

| 6 | PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.0 equiv 7 | rt | 4 | 8a (60) |

| 7 | PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.5 equiv 7 | rt | 4 | 8a (87)d |

| 8 | PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.5 equiv 7 | 110 | 1 | 8a (68) |

| 9 | PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.5 equiv 7 | 110a | 0.2 | 8a (65) |

| 10 | PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.5 equiv 7 | rtb | 1 | 8a (72) |

| iii | ||||

| 11 | H3PO4 (85%) | 110 | 2 | 1a (0) |

| 12 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 1.0 equiv PTSA | 110 | 12 | 1a (18) |

| 13 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 1.0 equiv PTSA | 110a | 1 | 1a (25) |

| 14 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 2.0 equiv PTSA | 110a | 1 | 1a (50) |

| 15 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 3.0 equiv PTSA | 110a | 1 | 1a (76)d |

| 16 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 4.0 equiv PTSA | 110a | 1 | 1a (72) |

| 17 | PhMe [0.2 M] + 3.0 equiv PTSA | 60b | 2 | 1a (62) |

| 18 | i, MeOH [1.0 M]; ii, PhMe [0.5 M] + 1.5 equiv 7; iii, PhMe [0.2 M] + 3.0 equiv PTSA | i, rt; ii, rt; iii, 110a | 29 | 1a (53)e |

MW (100 W).

US (42 kHz).

Determined after purification.

Optimal conditions.

One-pot process.

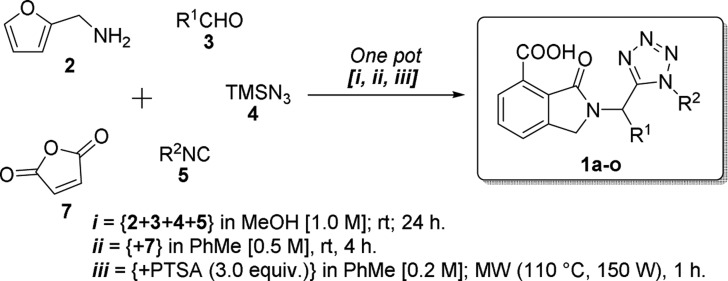

Using optimal conditions, we synthesized the series of novel unsymmetrical bis-heterocycles, 1a–o, in a one-pot manner using a combinatorial synthesis approach (Table 2). The scope of the substrate was evaluated using aldehydes and isocyanides of aliphatic and aromatic nature. The highest yield was observed for compound 1m (76%), which contains 4-methoxyphenyl and cyclohexyl as substituents at R1 and R2 positions, respectively. Adequate crystals for X-ray analysis of compound 1m (CCDC: 1503770) were obtained. Besides, the lowest yield was observed for the compound 1f (12%), which contains 4-chlorophenyl and 2,6-dimethylphenyl as substituents at R1 and R2 positions, respectively. In fact, 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide derivatives were synthesized in lower yields (12–30%) with respect to alkyl isocyanide derivatives (32–76%). This behavior can be attributed to the low nucleophilicity of aryl isocyanides with respect to that of their alkyl-containing analogues. Thus, modest-to-good overall yields were found (12–76%).

Table 2. Substrate Scope.

| compound | R1 | R2 | yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 4-OMePh | c-Hex | 53 |

| 1b | 4-OMePh | t-Bu | 73 |

| 1c | 4-OMePh | 2,6-diMePh | 17 |

| 1d | 4-ClPh | c-Hex | 27 |

| 1e | 4-ClPh | t-Bu | 41 |

| 1f | 4-ClPh | 2,6-diMePh | 12 |

| 1g | Ph | c-Hex | 60 |

| 1h | Ph | t-Bu | 46 |

| 1i | Ph | 2,6-diMePh | 30 |

| 1j | ANT | c-Hex | 70 |

| 1k | ANT | t-Bu | 41 |

| 1l | ANT | 2,6-diMePh | 22 |

| 1m | t-Bu | c-Hex | 76 |

| 1n | t-Bu | t-Bu | 32 |

| 1o | t-Bu | 2,6-diMePh | 21 |

Calculated after purification.

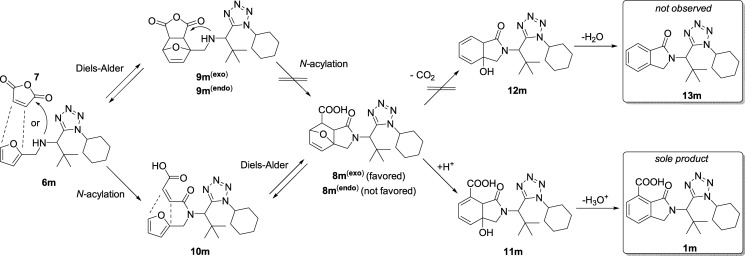

With regard to the reaction mechanisms, the mechanism for the Ugi-azide reaction has been documented.42 However, there are no mechanistic studies to understand the reaction between furan-2-ylmethanamines and maleic anhydride to construct the isoindolin-1-one core because, as can be envisaged, there are eight possible reaction pathways. Ugi-azide products 6 react with maleic anhydride (7) via either an N-acylation step to give intermediates 10 or a DA reaction that leads to the formation of cycloadducts 9 (endo or exo). These latter intermediates may undergo an N-acylation to produce compounds 8. However, as will be discussed, this pathway is not kinetically favored. Later, intermediates 10 can undergo a DA reaction to form cycloadducts 8 (endo or exo). Then, compounds 8 can follow two reaction pathways. The first one involves a decarboxylation process to get intermediates 12 and further dehydration giving bis-heterocycles 13. However, all of the attempts toward their synthesis were unsuccessful. On the other hand, compounds 8 can be protonated by PTSA to give intermediates 11, which then undergo a dehydration process leading to formation of carboxylic acid-containing products 1 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Reaction Mechanism.

In this context, DFT calculations were performed using the robust PCM (toluene)-M06-2X-D3/6-311+G(d)//M06-2X-D3/6-31G(d) level of theory to get all of the energy profiles (see the Supporting Information for computational details, Cartesian coordinates, energy profiles, and peripheral discussion). Thus, we decided to start the study taking product 1m as a model because its X-ray data were available to construct a structure similar to its minimal-energy conformation. Then, from our theoretical calculations, we found that the Ugi-azide reaction is followed by an N-acylation/exo-DA/dehydration process (pathway: 6m + 7 → 10m → 8m(exo) → 11m → 1m) (Scheme 2).

We have recently reported the reaction mechanism to construct a pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-one core (present in a variety of (±)-nuevamine, (±)-lennoxamine, and magallanesine-like aza-analogues) from 5-aminooxazoles and maleic anhydride, finding that these reactions occur in an opposite direction (cycloaddition before N-acylation).43 This is because pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-ones are aza-analogues of the isoindolin-1-ones and the nitrogen of their pyridine ring plays a major role in deprotonation of the carboxylic acid moiety and hence decarboxylation of the aromatic system. Our findings can also explain the results published by Trivedi and Salunkhe a few years ago.44 Various isoindolin-1-ones (advanced intermediates of the (±)-lennoxamine alkaloid) retaining the carboxylic acid moiety were synthesized.

It is noteworthy that our process does not obey Alder’s rule because intermediate 8m(endo) has an energy that is 9.6 kcal/mol higher than that of 8m(exo), which can be attributed to steric strain.

Finally, it is important to mention that our interest behind the synthesis of anthracene-containing products 1j–l lies in their potential applications in optics.45,46 As a matter of fact, the application of various anthracene-containing bis-heterocycles for bioimaging has been reported.47 Thus, computational calculations were performed by means of time-dependent (TD)-DFT using the tHCTHhyb/6-311g(d) level of theory for exploring the theoretical–photophysical properties of product 1j. Interestingly, we found an energy gap of 3.07 eV and two absorption bands at 449 and 403 nm. However, we noticed that the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of 1j is fully distributed on its anthracene system, whereas the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is located mostly on the isoindolin-1-one system, in contrast to other experimentally obtained products, probably due to an effective π–π* electron transfer throughout the bis-heterocyclic system (see the Supporting Information for further details). This latter behavior suggests that product 1j may show luminescent properties. In the same context, it may find application in optics and electronics.

In conclusion, the sustainable methodology described herein is the first MCR one-pot synthesis of bis-heterocycles containing isoindolin-1-one and 1,5-DS-T moieties in a linked manner. Both rings of isoindolin-1-one core and even the tetrazole ring were constructed in one experimental procedure, whereas other methods reported involve a cyclization step toward only one ring at a time, γ-lactam or 1,5-DS-T. Therefore, considering the molecular complexity of products 1a–o and the numbers of bonds (9) and rings (3) formed in one experimental procedure, and that only two molecules of water were formed as byproducts, the overall yields obtained were reasonably good. This work is a contribution to the synthesis of linked-type unsymmetrical bis-heterocycles using Ugi-azide one-pot processes. DFT-based computational calculations gave us enough elements to propose the most plausible reaction mechanism among eight possible ones, which involves an Ugi-azide/(N-acylation/exo-DA)/dehydration sequence as the most thermodynamic and kinetically favored pathway. An anthracene-containing analogue displayed a very interesting distribution of HOMO–LUMO frontier orbitals throughout both of its cyclic moieties, which probably can be attributed to effective electron transfer.

Experimental Section

General Information

1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired on a 500 MHz spectrometer. The solvent for the NMR samples was CDCl3. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (δ/ppm). The internal reference for the NMR spectra is tetramethylsilane at 0.00 ppm. Coupling constants are reported in hertz (J/Hz). Multiplicities of the signals are reported using standard abbreviations: singlet (s), doublet (d), triplet (t), quartet (q), and multiplet (m). IR spectra were recorded by the attenuated total reflection (ATR) method, using neat compounds. The wavelengths are reported in reciprocal centimeters (νmax/cm–1). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) spectra were acquired via electrospray ionization ESI (+) and recorded via the time-of-flight (TOF) method. Reactions at reflux were performed in round-bottomed flasks, using a recirculation system mounted on a sand bath, with an electronic temperature control. MW-assisted reactions were performed in sealed vials in a closed-vessel mode, using a monomodal MW reactor without a pressure sensor. US-irradiated reactions were performed in sealed vials placed in a water bath of a sonicator cleaner working at frequencies of 42 kHz ± 6%. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC, and the spots were visualized under UV light (254 or 365 nm). Flash column chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh) and mixtures in different proportions of hexanes, with ethyl acetate as mobile phase. Melting points were determined on a Fisher–Johns apparatus and were uncorrected. The purity degree was documented qualitatively for each product, with copies of all 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Commercially available reagents were used without further purification. The solvents were distilled and dried according to standard procedures.

Procedure to Synthesize Product 6a

In a round-bottomed flask (10 mL) containing a solution of furan-2-ylmethanamine (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in anhydrous MeOH [1.0 M] under a nitrogen atmosphere were added sequentially the corresponding aldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), isocyanide (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), and azidotrimethylsilane (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The flask was closed, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h at rt. Then, the solvent was removed until dryness and the crude was purified by silica-gel column chromatography using a mixture of hexane with AcOEt (7/3; v/v) to afford the Ugi-azide product, 6a.

Procedure to Synthesize the Product 8a

In a round-bottomed flask (10 mL) containing a solution of compound 6a (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in anhydrous PhMe [0.5 M] under a nitrogen atmosphere was added maleic anhydride (1.5 equiv). The flask was closed and the reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h at rt. Then, the solvent was removed until dryness and the crude was purified by silica-gel column chromatography using a mixture of hexanes with ethyl acetate (7/3; v/v) to afford the oxa-bridged compound, 8a.

Procedure to Synthesize the Product 1a

In a vial (10 mL) containing a solution of compound 8a (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in anhydrous PhMe [0.2 M] under nitrogen atmosphere was added PTSA (3.0 equiv) at rt. The vial was closed, and the reaction mixture was MW-heated at 110 °C (100 W) for 1 h, and the solvent was removed until dryness. Then, the crude product was purified by silica-gel column chromatography using a mixture of hexanes with ethyl acetate (7/3, v/v) to afford the final bis-heterocyclic product, 1a.

One-Pot Synthesis of Products 1a–o

In a vial (10 mL) containing a solution of furan-2-ylmethanamine (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in anhydrous MeOH [1.0 M] under a nitrogen atmosphere were added sequentially the corresponding aldehyde (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), isocyanide (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv), and azidotrimethylsilane (0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The vial was closed, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h at rt. Then, the solvent was removed until dryness and the crude was dissolved in anhydrous PhMe [0.5 M]. Following this, maleic anhydride (1.5 equiv) was added. The vial was closed, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h at rt. Then, anhydrous PhMe was added to dilute the reaction mixture to 0.2 M with respect to the starting aldehyde. Later, PTSA (3.0 equiv) was added. The vial was closed, and the new reaction mixture was MW-heated at 110 °C (100 W) for 1 h. Then, the solvent was removed until dryness. The crude product was purified by silica-gel column chromatography using a mixture of hexanes with ethyl acetate (7/3; v/v) to afford the 2-tetrazolylmethyl-isoindolin-1-ones, 1a–o.

1-(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-N-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)methanamine (6a)

Pale yellow solid (181.7 mg, 99%); mp = 91–93 °C; Rf = 0.54 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.33–6.31 (m, 1H), 6.18–6.17 (m, 1H), 5.18 (s, 1H), 4.29–4.22 (m, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.76 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (s, 1H), 1.89–1.66 (m, 6H), 1.53–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.31–1.18 (m, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.7, 154.6, 152.6, 142.1, 129.7, 128.7, 114.3, 110.2, 107.8, 57.9, 55.3 (2), 43.5, 32.5, 25.2, 24.7; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 3322 (N–H); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H26N5O2, 368.2081; found, 368.2077.

2-((1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-1-oxo-1,2,3,6,7,7a-hexahydro-3a,6-epoxyisoindole-7-carboxylic Acid (8a)

Pale yellow solid (202.3 mg, 87%); mp = 202–204 °C; Rf = 0.32 (AcOEt); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.08 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (s, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.55–6.54 (m, 1H), 6.44–6.43 (m, 1H), 5.18 (s, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (s, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.59 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.10 (m, 1H), 1.95–1.88 (m, 3H), 1.82–1.79 (m, 1H), 1.69–1.64 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.36 (m, 1H), 1.28–1.23 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 173.9, 172.2, 160.2, 152.6, 136.7, 135.5, 129.8, 124.6, 114.7, 88.8, 82.0, 58.3, 55.3, 51.6, 48.8, 46.4, 45.6, 33.0, 32.4, 25.1 (2), 24.7; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2934 (O–H), 1720 (O–C=O), 1653 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H28N5O5, 466.2084; found, 466.2080.

2-((1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1a)

White solid (169.9 mg, 76% stepwise from 8a) (118.5 mg, 53% via one pot); mp = 126–128 °C; Rf = 0.30 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.41 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.76–7.72 (m, 1H), 7.69–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.35 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 4.27–4.19 (m, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 2.22–2.13 (m, 1H), 1.02–1.82 (m, 4H), 1.77–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.59 (m, 1H), 1.51–1.42 (m, 1H), 1.35–1.18 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.8, 165.3, 160.8, 151.9, 143.0, 133.7, 133.1, 130.0, 129.4, 128.4, 127.3, 124.6, 115.1, 58.8, 55.5, 49.5, 49.0, 32.9, 32.5, 25.2, 25.1, 24.7; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2937 (O–H), 1718 (O–C=O), 1602 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H26N5O4, 448.1979; found, 448.2000.

2-((1-(tert-Butyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1b)

Pale yellow solid (153.7 mg 73%); mp = 118–120 °C; Rf = 0.36 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.73–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.64–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.20 (s, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 5.10 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 1.76 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.6, 165.2, 163.1, 160.1, 142.7, 133.6, 132.6, 129.9, 129.7, 129.0, 127.4, 127.0, 114.6, 64.6, 55.4, 51.5, 48.7, 29.4; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2993 (O–H), 1711 (O–C=O), 1607 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C22H24N5O4, 422.1822; found, 422.1845.

2-((1-(2,6-Dimethylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1c)

Pale yellow solid (39.9 mg, 17%); mp = 263–265 °C; Rf = 0.39 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 15.29 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 1H), 7.70–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.43–7.39 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.09–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 5.51 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 2.09 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.6, 165.0, 160.7, 154.3, 142.9, 136.3, 136.2, 133.7, 133.0, 131.5, 130.8, 130.4, 129.6, 129.3, 128.8, 128.3, 127.2, 124.0, 114.9, 55.4, 49.4, 49.1, 17.2, 16.8; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2927 (O–H), 1720 (O–C=O), 1608 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C26H24N5O4, 470.1822; found, 470.1842.

2-((4-Chlorophenyl)(1-cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1d)

Pale yellow solid (60.9 mg, 27%); mp = 204–206 °C; Rf = 0.32 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.32 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.70–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 5.23 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 4.27–4.20 (m, 2H), 2.22–2.16 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.06 (m, 1H), 1.98–1.84 (m, 3H), 1.82–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.64–1.57 (m, 1H), 1.46–1.36 (m, 1H), 1.30–1.12 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.0, 164.9, 151.3, 142.9, 136.3, 133.8, 133.3, 131.3, 130.0 (2), 128.0, 127.4, 58.9, 49.0, 48.8, 33.1, 33.0, 32.7, 25.1, 24.8, 24.7; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2935 (O–H), 1718 (O–C=O), 1615 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H23ClN5O3, 452.1483; found, 452.1485.

2-((1-(tert-Butyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1e)

Pale yellow solid (87.1 mg, 41%); mp = 123–125 °C; Rf = 0.45 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.42 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 5.09 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 1.77 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.8, 165.1, 162.5, 142.6, 135.2, 133.8, 133.7, 132.9, 129.9, 129.6, 129.5, 128.6, 127.1, 64.8, 51.3, 48.7, 29.4; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2987 (O–H), 1720 (O–C=O), 1608 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H21ClN5O3, 426.1327; found, 426.1328.

2-((4-Chlorophenyl)(1-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1f)

White solid (28.4 mg, 12%); mp = 257–259 °C; Rf = 0.36 (hexanes–EtOAc = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.37 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.72–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.64–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.31–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 5.44 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 1.99 (s, 3H), 1.33 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.8, 164.8, 153.7, 142.7, 136.4, 136.2, 135.9, 133.9, 133.3, 131.7, 130.7, 130.6, 130.3, 129.9, 129.6, 129.4, 128.9, 127.9, 127.3, 49.0, 48.9, 17.3, 17.0; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2926 (O–H), 1719 (O–C=O), 1613 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C25H21ClN5O3, 474.1327; found, 474.1334.

2-((1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1g)

Pale yellow solid (125.1 mg, 60%); mp = 129–130 °C; Rf = 0.45 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.42 (s, 1H), 7.77–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.52–7.43 (m, 3H), 7.39–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 5.37 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 1H), 4.27–4.17 (m, 1H), 2.24–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.06–1.90 (m, 3H), 1.87–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.70 (m, 1H), 1.64–1.58 (m, 1H), 1.53–1.40 (m, 1H), 1.35–1.17 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.0, 165.2, 151.7, 143.0, 133.7, 133.2, 132.8, 130.1, 129.8, 129.4, 129.2, 128.6, 128.2, 127.4, 126.5, 58.8, 50.0, 49.0, 33.0, 32.5, 25.2, 25.1, 24.7; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2935 (O–H), 1725 (O–C=O), 1610 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H24N5O3, 418.1873; found, 418.1879.

2-((1-(tert-Butyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1h)

White solid (89.9 mg, 46%); mp = 169–171 °C; Rf = 0.42 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.41 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.74–7.69 (m, 1H), 7.66–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.72–7.38 (m, 3H), 7.36–7.32 (m, 2H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 5.13 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (d, J = 18.1 Hz, 1H), 1.77 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.8, 165.2, 162.9, 142.7, 135.3, 133.6, 132.7, 129.6, 129.2, 129.1, 128.8, 128.5, 127.1, 64.7, 52.0, 48.8, 29.4; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2933 (O–H), 1704 (O–C=O), 1590 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H22N5O3, 392.1717; found, 392.1732.

2-((1-(2,6-Dimethylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)(phenyl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1i)

Pale yellow solid (65.9 mg, 30%); mp = 257–259 °C; Rf = 0.36 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.36 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.71–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.63–7.59 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.28 (m, 5H), 7.23–7.20 (m, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 5.47 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (d, J = 17.8 Hz, 1H), 2.02 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.7, 164.9, 154.1, 142.9, 136.2, 136.1, 133.8, 133.1, 132.1, 131.5, 130.7, 130.1, 129.6 (2), 129.3, 129.0, 128.8, 128.2, 127.2, 50.0, 49.1, 17.3, 16.8; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2914 (O–H), 1703 (O–C=O), 1589 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C25H22N5O3, 440.1717; found, 440.1723.

2-(Anthracen-9-yl(1-cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1j)

Pale yellow solid (180.9 mg, 70%); mp = 119–121 °C; Rf = 0.30 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.67 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 8.42 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.16 (s, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.52 (m, 4H), 5.62 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 4.53–7.45 (m, 1H), 4.25 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.04–2.96 (m, 1H), 2.28–2.22 (m, 2H), 1.97–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.73 (m, 1H), 1.52–1.18 (m, 3H), 0.94–0.83 (m, 1H), 0.71–0.61 (m, 1H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.0, 165.3, 154.4, 143.1, 133.8, 133.1, 132.0, 131.4, 131.0, 130.1, 129.6, 128.9, 128.1, 127.2, 125.7, 122.3, 122.1, 59.1, 59.0, 50.3, 47.0, 33.1, 32.8, 29.7, 24.8 (2); FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2930 (O–H), 1713 (O–C=O), 1614 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C31H28N5O3, 518.2186; found, 518.2217.

2-(Anthracen-9-yl(1-(tert-butyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1k)

White yellow solid (100.7 mg, 41%); mp = 120–121 °C; Rf = 0.41 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.17 (bs, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H) 7.71–7.77 (m, 1H), 7.61–7.52 (m, 6H), 5.62 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 1.23 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.0, 165.3, 154.4, 143.1, 133.8, 133.1, 132.0, 131.4, 131.0, 130.1, 129.6, 128.9, 128.1, 127.2, 125.7, 122.3, 122.1, 59.0, 50.3, 47.0, 33.1 ppm; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2924 (O–H), 1711 (O–C=O, N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C29H26N5O3, 492.2030; found, 492.2005.

2-(Anthracen-9-yl(1-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)methyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1l)

Pale yellow solid (59.3 mg, 22%); mp = 191–193 °C; Rf = 0.35 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.44 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 8.04–7.80 (m, 3H), 7.67–7.62 (m, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.32 (m, 3H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 6.72–6.66 (m, 1H), 6.41–6.29 (m, 1H), 6.14 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 5.67 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 1H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 0.38 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.4, 164.2, 156.2, 142.1, 134.7, 133.6, 132.8, 132.1, 130.5, 130.1, 129.5, 129.2, 128.5, 127.8, 127.0, 126.9, 126.1, 124.3, 120.9, 50.0, 45.8, 16.3, 14.5; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2922 (O–H), 1711 (O–C=O), 1610 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C33H26N5O3, 540.2030; found, 540.2052.

2-(1-(1-Cyclohexyl-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1m)

Yellow crystals (150.9 mg, 76%); mp = 213–215 °C; Rf = 0.48 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.43 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.80–7.75 (m, 1H), 7.74–7.71 (m, 1H), 5.77 (s, 1H), 5.00 (q, J = 18.4 Hz, 2H), 4.50–4.53 (m, 1H), 2.24–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.09–1.99 (m, 2H), 1.93–1.75 (m, 3H), 1.58–1.44 (m, 2H), 1.38–1.28 (m, 2H), 1.23 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 171.3, 165.0, 150.5, 143.0, 134.0, 133.4, 129.7, 127.7, 128.3, 58.7, 53.5, 50.6, 37.0, 34.2, 32.9, 27.8, 25.5, 25.3, 24.9; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2932 (O–H), 1717 (O–C=O), 1610 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H28N5O3, 398.2186; found, 398.2199.

2-(1-(1-(tert-Butyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1n)

White solid (59.4 mg, 32%); mp = 173–175 °C; Rf = 0.52 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.40 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.77–7.70 (m, 2H), 5.91 (s, 1H), 5.13 (d, J = 18.4 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 18.4 Hz, 1H), 1.76 (s, 9H), 1.14 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.8, 165.3, 162.3, 142.7, 133.5, 132.6, 129.6, 128.5, 126.8, 64.3, 57.1, 51.1, 36.5, 29.3, 27.6; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2962 (O–H), 1715 (O–C=O), 1601 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C19H26N5O3, 372.2030; found, 372.2034.

2-(1-(1-(2,6-Dimethylphenyl)-1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-2,2-dimethylpropyl)-3-oxoisoindoline-4-carboxylic Acid (1o)

Yellow solid (44.0 mg, 21%); mp = 228–230 °C; Rf = 0.33 (hexanes–AcOEt = 3/2; v/v); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.45 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.82–7.76 (m, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.42 (m, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (s, 1H), 5.05 (d, J = 18.6 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (d, J = 18.6 Hz, 1H), 2.07 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.4, 164.8, 152.7, 142.2, 135.5, 135.2, 134.0, 133.3, 131.6, 130.7, 129.6, 129.5, 129.1, 127.5, 127.0, 53.7, 50.5, 37.7, 27.7, 17.8, 16.4; FT-IR (ATR) νmax (cm–1): 2926 (O–H), 1715 (O–C=O), 1624 (N–C=O); HRMS (ESI-TOF) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H26N5O3, 420.2030; found, 420.2031.

Acknowledgments

R.G.-M. is grateful for financial support from the CIO-UG (009/2015), DAIP (859/2016), and CONACYT (CB-2011-166747-Q) projects. A.I.-J (ID: I00247) thanks UG for his temporary position. A.R.-G. (554166/290817) and A.E.C.-J. (708711/585585) acknowledge CONACYT-México for their scholarships. J.O.C.J.-H. kindly acknowledges the National Laboratory for supercomputing resources (UG-UAA-CONACYT: 123732).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00281.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Speck K.; Magauer T. The chemistry of isoindole natural products. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2048–2078. 10.3762/bjoc.9.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caveney A. F.; Giordani B.; Haig G. M. Preliminary effects of pagoclone, a partial GABAA agonist, on neuropsychological performance. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2008, 4, 277–282. 10.2147/NDT.S2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List A.; Kurtin S.; Roe D. J.; Buresh A.; Mahadevan D.; Fuchs D.; Rimsza R.; Heaton R.; Knight R.; Zeldis J. B. Efficacy of Lenalidomide in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 549–557. 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabrocki J.; Smith G. D.; Dunbar J. B. Jr.; Iijima H.; Marshall G. R. Conformational mimicry. 1. 1, 5-Disubstituted tetrazole ring as a surrogate for the cis amide bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 5875–5880. 10.1021/ja00225a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rentería-Gómez A.; Islas-Jácome A.; Díaz-Cervantes E.; Villaseñor-Granados T.; Robles J.; Gámez-Montaño R. Synthesis of azepino[4,5-b]indol-4-ones via MCR/free radical cyclization and in vitro–in silico studies as 5-Ht6R ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2333–2338. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myznikov L. V.; Hrabalek A.; Koldobskii G. I. Drugs in the tetrazole series. (Review). Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2007, 43, 1–9. 10.1007/s10593-007-0001-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovskii V. A.; Trifonov R. E.; Popova E. A. Medicinal chemistry of tetrazoles. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2012, 61, 768–780. 10.1007/s11172-012-0108-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aromí G.; Barrios L. A.; Roubeau O.; Gámez P. Triazoles and tetrazoles: Prime ligands to generate remarkable coordination materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 485–546. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couty S.; Liégault B.; Meyer C.; Cossy J. Heck-Suzuki-Miyaura Domino Reactions Involving Ynamides. An Efficient Access to 3-(Arylmethylene)isoindolinonas. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2511–2514. 10.1021/ol049302m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Valdez G.; Olguín-Uribe S.; Millan-Ortíz A.; Gámez-Montaño R.; Miranda L. D. Convenient access to isoindolinones via carbamoyl radical cyclization. Synthesis of cichorine and 4-hydroxyisoindolin-1-one natural products. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 2693–2701. 10.1016/j.tet.2011.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C.; Falck J. R. Rhodium catalyzed synthesis of isoindolinones via CeH activation of N-benzoylsulfonamides. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 9192–9199. 10.1016/j.tet.2012.08.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronzi C.; Collarile S.; Croce G.; Filosa R.; De Caprariis P.; Peduto A.; Palombi L.; Intintoli V.; Di Mola A.; Massa A. Synthesis and Reactivity of the 3-Substituted Isoindolinone Framework to Assemble Highly Functionalized Related Structures. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 5357–5365. 10.1002/ejoc.201200678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zubkov F. I.; Airiyan I. K.; Ershova J. D.; Galeev T. R.; Zaytsev V. P.; Nikitina E. V.; Varlamov A. V. Aromatization of IMDAF adducts in aqueous alkaline media. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 4103–4109. 10.1039/c2ra20295f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-González M. A.; Zamudio-Medina A.; Ordoñez M. Practical and high stereoselective synthesis of 3-(arylmethylene)isoindolin-1-ones from 2-formylbenzoic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5756–5758. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.08.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Jin L.; Zhu Y.; Cao X.; Zheng L.; Mo W. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Cyclization of 2-Iodobenzamides: An Efficient Synthesis of 3-Acyl Isoindolin-1-ones and 3-Hydroxy-3-acylisoindolin-1-ones. Synlett 2013, 24, 1856–1860. 10.1055/s-0033-1339449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso R.; Ziccarelli I.; Armentano D.; Marino N.; Giofrè S.; Gabriele B. Divergent Palladium Iodide Catalyzed Multicomponent Carbonylative Approaches to Functionalized Isoindolinone and Isobenzofuranimine Derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 3506–3518. 10.1021/jo500281h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa M.; Ikoma M.; Sasaki M. Parallel synthesis of tandem Ugi/Diels–Alder reaction products on a soluble polymer support directed toward split-pool realization of a small molecule library. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 415–418. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.11.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa M.; Ikoma M.; Sasaki M. Simultaneous accumulation of both skeletal and appendage-based diversities on tandem Ugi/Diels–Alder products. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 5863–5866. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.06.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medimagh R.; Marque S.; Prim D.; Marrot J.; Chatt S. Concise Synthesis of Tricyclic Isoindolinones via One-Pot Cascade Multicomponent Sequences. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1817–1820. 10.1021/ol9003965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Xu J. One-Pot Facile Synthesis of Substituted Isoindolinones via an Ugi Four-Component Condensation/Diels-Alder Cycloaddition/Deselenization-Aromatization Sequence. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8859–8861. 10.1021/jo901628a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sashidhara K. V.; Singh L. R.; Palnati G. R.; Avula S. R.; Kant R. A Catalyst-Free One-Pot Protocol for the Construction of Substituted Isoindolinones under Sustainable Conditions. Synlett 2016, 27, 2384–2390. 10.1055/s-0035-1562614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C.; Takamatsu K.; Hirano K.; Miura M. Copper-Catalyzed Intramolecular Benzylic C–H Amination for the Synthesis of Isoindolinones. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7675–7684. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvary A.; Maleki A. A review of syntheses of 1,5-disubstituted tetrazole derivatives. Mol. Diversity 2015, 19, 189–212. 10.1007/s11030-014-9553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleki A.; Sarvary A. Synthesis of tetrazoles via isocyanide-based Reactions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 60938–60955. 10.1039/C5RA11531K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soural M.; Bouillon I.; Krchnák V. Combinatorial Libraries of Bis-heterocyclic Compounds with Skeletal Diversity. J. Comb. Chem. 2008, 10, 923–933. 10.1021/cc8001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandi M.; Rahimi S.; Zarezadeh N. Synthesis of Novel Tetrazole Containing Quinoline and 2,3,4,9-Tetrahydro-1H-β-Carboline Derivatives. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2015, 52, 2546. 10.1002/jhet.2546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S.; Agarwal P.; Srivastava K.; RajaKumar S.; Puri S. K.; Verma P.; Saxena J. K.; Sharma A.; Lal J.; Chauhan P. M. S. Synthesis and bioevaluation of novel 4-aminoquinoline-tetrazole derivatives as potent antimalarial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 66, 69–81. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo-Cruz R. E.; Rentería-Gómez A.; Islas-Jácome A.; Cortes-García C. J.; Díaz-Cervantes E.; Robles J.; Gámez-Montaño R. Synthesis of 3-tetrazolylmethyl-azepino[4,5-b]indol-4-ones in two reaction steps: (Ugi-azide/N-acylation/ SN2)/free radical cyclization and docking studies to a 5-Ht6 model. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 6470–6476. 10.1039/c3ob41349g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Galindo L. E.; Islas-Jácome A.; Alvarez-Rodríguez N. V.; El Kaim L.; Gámez-Montaño R. Synthesis of 2-Tetrazolylmethyl-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1H-β-carbolines by a One-Pot Ugi-Azide/Pictet–Spengler Process. Synthesis 2014, 46, 49–56. 10.1002/chin.201425145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cano P. A.; Islas-Jácome A.; González-Marrero J.; Yépez-Mulia L.; Calzada F.; Gámez-Montaño R. Synthesis of 3-tetrazolylmethyl-4H-chromen-4-ones via Ugi-azide and biological evaluation against Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia and Trichomonas vaginalis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 1370–1376. 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unnamatla M. V. B.; Islas-Jácome A.; Quezada-Soto A.; Ramírez-López S. C.; Flores-Álamo M.; Gámez-Montaño R. Multicomponent One-Pot Synthesis of 3-Tetrazolyl and 3-Imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin Tetrazolo[1,5-a]quinolines. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 10576–10583. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos C.; Marcaccini S.; Menchi G.; Pepino R.; Torroba T. Studies on isocyanides: synthesis of tetrazolyl-isoindolinones via tandem Ugi four-component condensation/intramolecular amidation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 149–152. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.10.154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islas-Jácome A.; González-Zamora E.; Gámez-Montaño R. A short microwave-assisted synthesis of tetrahydroisoquinolin-pyrrolopyridinones by a triple process: Ugi-3CR – aza Diels–Alder/S-oxidation/Pummerer. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 5245–5248. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.07.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugi I. From Isocyanides via Four-Component Condensations to Antibiotic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1982, 21, 810–819. 10.1002/anie.198208101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caillot G.; Hegde S.; Gras E. A mild entry to isoindolinones from furfural as renewable resource. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 1195–1200. 10.1039/c3nj41050a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Janvier P.; Zhao G.; Bienaymé H.; Zhu J. A Novel Multicomponent Synthesis of Polysubstituted 5-Aminooxazole and Its New Scaffold-Generating Reaction to Pyrrollo[3,4-b]pyridine. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 877–880. 10.1021/ol007055q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Montaño R.; González-Zamora E.; Potier P.; Zhu J. Multicomponent domino process to oxa-bridged polyheterocycles and pyrrolopyridines, structural diversity derived from work-up procedure. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 6351–6358. 10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00634-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier P.; Sun X.; Bienaymé H.; Zhu J. Ammonium Chloride-Promoted Four-Component Synthesis of Pyrrolo[3,4-b]pyridine-5-one. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 2560–2567. 10.1021/ja017563a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayol A.; González-Zamora E.; Bois-Choussy M.; Zhu J. Lithium Bromide-Promoted Three-Component Synthesis of Oxa-Bridged Tetracyclic Tetrahydroisoquinolines. Heterocycles 2007, 73, 729–742. 10.3987/COM-07-S(U)54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islas-Jácome A.; Cárdenas-Galindo L. E.; Jerezano A. V.; Tamariz J.; González-Zamora E.; Gámez-Montaño R. Synthesis of Nuevamine Aza-Analogues by a Sequence: I-MCR–Aza-Diels–Alder–Pictet–Spengler. Synlett 2012, 23, 2951–2956. 10.1055/s-0032-1317622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier P.; Bienaymé H.; Zhu J. A five-Components Synthesis of Hexasubstituted Benzene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4291–4294. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas-Galindo L. E.; Islas-Jácome A.; Cortes-García C. J.; El Kaim L.; Gámez-Montaño R. Efficient Synthesis of 1,5-disubstituted-1H-tetrazoles by an Ugi-azide Process. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2013, 57, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Islas-Jácome A.; Rentería-Gómez A.; Rentería-Gómez M. A.; González-Zamora E.; Jiménez-Halla J. O. C.; Gámez-Montaño R. Selective reaction route in the construction of the pyrrolo[3,4-b] pyridin-5-one core from a variety of 5-aminooxazoles and maleic anhydride. A DFT study. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3496–3500. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.06.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarang P. S.; Yadav A. A.; Patil P. S.; Krishna U. M.; Trivedi G. K.; Salunkhe M. M. Synthesis of Advanced Intermediates of Lennoxamine Analogues. Synthesis 2007, 7, 1091–1095. 10.1055/s-2007-965950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P.; Razi S. S.; Ali R.; Gupta R. C.; Yadav S. S.; Narayan G.; Misra A. Selective Naked-Eye Detection of Hg2+ through an Efficient Turn-On Photoinduced Electron Transfer Fluorescent Probe and Its Real Applications. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 8693–8699. 10.1021/ac501780z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis L. D.; Raines R. T. Bright Ideas for Chemical Biology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 142–155. 10.1021/cb700248m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.; Dodani S. C.; Chang C. J. Reaction-based small-molecule fluorescent probes for chemoselective bioimaging. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 973–984. 10.1038/nchem.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.