Abstract

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) below 10 nm in size can undergo renal clearance, which could facilitate their clinical translation. However, due to non-linear, direct relationship between their absorption and size, use of such “ultra-small” AuNPs as contrast agents for photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is challenging. This problem is complicated by the tendency of absorption for ultra-small AuNPs to be below the NIR range, which is optimal for in vivo imaging. Herein, we present 5-nm molecularly activated plasmonic nanosensors (MAPS) that produce a strong photoacoustic signal in labeled cancer cells in the NIR, demonstrating the feasibility of sensitive PAI with ultra-small AuNPs.

1. Introduction

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are widely used as molecularly targeted contrast agents for photoacoustic imaging (PAI) because of their high absorption cross-sections [1–7]. For example, an absorption cross-section of 40nm spherical AuNPs is up to 5 orders of magnitude higher than the cross-section of commonly used absorbing organic dyes, such as rhodamine-6G or indocyanine green [8]. Therefore, labeling a molecular target with a single such nanoparticle would be theoretically equivalent to labeling it with thousands of organic dye molecules. Molecularly specific labeling of a single target with thousands of organic chromophores is challenging. However, recent studies have reported development of organic dyes and dye aggregates encapsulated either in micelles or liposomes that can facilitate delivery of a large quantity of chromophores for biomolecular labeling [9–12]; this is a very promising direction in molecular PAI that is still in early stages of development.

A number of studies in the literature report molecularly specific PAI using AuNPs with a core diameters greater than 20 nm [13–17], which is well above the renal clearance threshold of 5 - 10 nm [18–21]. Retention of non-biodegradable AuNPs can result in side effects such as chronic inflammation and associated complications [22,23]. The lack of efficient body clearance of AuNPs has been a long-standing problem in clinical translation of many promising technologies that are based on in vivo administration of gold nanomaterials [24–27]. Note that AuNPs for in vivo applications consist of a non-biodegradable gold core and an organic coating that can eventually degrade in the body. During in vivo administration, the overall hydrodynamic diameter of AuNPs could be larger than the renal clearance threshold, preventing fast renal clearance. As the organic coating degrades, the AuNPs with small core sizes could undergo accelerated excretion from the body. However, the excretion process is still very poorly understood and requires significant further investigation.

Development of ultra-small, targeted AuNPs with core diameters below 10 nm can address the body-clearance problem. In addition to overcoming body clearance concerns, the use of ultra-small particles can also greatly improve organ biodistribution and depth of tissue penetration. For example, when particle size increased from 15 nm to 150 nm, a higher level of accumulation in the liver and spleen was observed [28,29] due to an associated higher propensity of interactions of bigger nanoparticles with the reticuloendothelial system. Furthermore, intravenously administered AuNPs with core sizes ~15 nm [30] or 30nm micelles [31] were found significantly further away from blood vessels in tumors compared to AuNPs of 60-100 nm or 100nm micelles, respectively. In addition, a highly uniform tissue distribution was reported for intravenously administered sub-10nm HER2-targeted silica nanoparticles in a murine breast cancer model [20]. It is noteworthy that ultra-small nanoparticles are comparable in size to some biomolecules, such as albumins (~5 nm) and antibodies (~15 nm), and therefore could exhibit similar pharmacokinetics given a properly controlled surface coating. A key challenge in the development of ultra-small AuNPs for PAI, however, is the nonlinear dependence of their absorption cross-section on their core size. For example, the absorption cross-section of spherical AuNPs with sizes below 80 nm is proportional to the 3rd power of their diameter [32–34]. Furthermore, the need for a high absorption in the NIR region for in vivo applications makes development of ultra-small nanoparticles for PAI even more challenging as NIR-absorbing AuNPs tend to be larger than 20 nm in at least one dimension [2].

Previously, we demonstrated that controlled formation of biodegradable gold nanoparticle assemblies from 5nm primary gold particles can result in a strong NIR absorbance [35] and a high photoacoustic (PA) signal [36]. We also showed that receptor-mediated uptake of EGFR-targeted spherical 40nm AuNPs by cancer cells results in a strong absorption of the nanoparticles in the NIR region [37]. We further demonstrated that this increase is associated with formation of closely spaced nanoparticle assemblies in cellular endosomal compartments [38]. Because the NIR absorbance was closely associated with molecularly specific uptake by EGFR-expressing cancer cells, we referred to these EGFR-targeted 40nm AuNPs as “molecularly activated plasmonic nanosensors” (MAPS) [13]. We used 40nm MAPS to enable highly sensitive and specific detection of tumor micrometastasis as small as 50 µm in lymph nodes of a murine model of head and neck cancer by spectroscopic PAI [13]. Taken together, these previous studies show that: (1) closely spaced assemblies of ultra-small 5nm AuNPs can produce a strong PA signal in the NIR region, and (2) EGFR-targeted spherical nanoparticles form closely spaced assemblies inside cancer cells that enable highly sensitive and molecularly specific PAI. Based on these data, we hypothesized that 5nm AuNPs could be used for development of molecular-activated plasmonic nanosensors (i.e., 5nm MAPS) for molecularly specific PAI, similar to what we achieved with 40nm MAPS. To test this hypothesis, we first synthesized and characterized 5nm MAPS. We then validated their labelling and PA-signal-generation abilities with optical and PA imaging of EGFR+ cancer cells. Finally, we carried out a direct comparison between 5nm and 40nm MAPS in their ability to generate a strong PA signal from labeled cancer cells.

2. Methods

2.1 Synthesis of gold nanoparticle antibody conjugates

Citrate-coated spherical 5 and 40 nm AuNPs were received from NanoHybrids (Austin, TX) as a gift. Monoclonal anti-EGFR clone 29.1 (Sigma, E2760) and monoclonal anti-rabbit clone RG-16 (Sigma, I0138) were used as targeting and non-targeting antibodies, respectively. Antibody conjugation was carried out following the protocol described in [39]. Briefly, antibody solutions received from the manufacturer were filtered through a 100 kDa MWCO centrifuge filter (EMD Millipore) to remove ascites fluid and preservatives. The purified antibodies were collected from the filter using 100mM sodium phosphate buffer with pH 7.5. Then, 100 µL of 100mM sodium periodate (Sigma) was added to 1 mL of 1 mg/mL antibody solution to form aldehyde groups on the antibody’s carbohydrate moiety through mild oxidation. The solution was incubated in the dark on a shaker at 350 rpm at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. The reaction was quenched by the addition of a 50-fold volume of PBS. The antibody solution was washed by centrifugation through a 10kDa MWCO centrifuge filter (EMD Millipore) for 20 mins at 3,100 g at 4 °C, and the antibodies were labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) fluorophores (A20173, Invitrogen) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, 100 µL of fluorescently labeled antibodies at 1 mg/mL in PBS buffer were mixed with 4 µL of 23.25mM (~150-fold molar excess) heterofunctional hydrazide-PEG-dithiol linker (dithiolalkanearomatic-PEG6-NHNH2, SPT-0014B, SensoPath Technologies), and the mixture was incubated in the dark for 1 hr at RT on a shaker at 350 rpm. Unreacted linker molecules were removed by a 10kDa MWCO centrifuge filter at 3,100 g for 20 min at 4°C, and the linker-antibody conjugates were reconstituted at 100 µg/mL in PBS.

Antibody-linker solution at 100 µg/mL in PBS was added to 5nm and 40nm AuNPs, both at optical density (OD) = 1, to achieve final antibody concentrations of 47 and 9.1 µg/mL, respectively, corresponding to 5- and 680-fold molar excesses of antibodies, respectively. The suspensions were incubated in the dark for 1 hr at RT on a shaker at 350 rpm. Then, 5 kDa mPEG-SH (MPEG-SH-5000, Laysan Bio) at 0.05 mg/mL in PBS was added to the suspensions of 5nm and 40nm nanoparticles to achieve final concentrations of 3.8 and 4.2 µg/mL, respectively, followed by an additional 30min incubation at RT on a shaker at 350 rpm. Then, antibody-conjugated 5nm AuNPs were spun down at 100,000 g for 1 hr at 4 °C. Forty nanometer AuNPs were centrifuged in the presence of 2% w/v PEG copolymer (Polyethyleneglycol Bisphenol A Epichlorohydrin Copolymer, P2263, Sigma) at 3,100 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The final antibody conjugated nanoparticles were resuspended in PBS and stored at 4 °C for future experiment. UV-vis spectrophotometry (Synergy HT, BioTek Instruments), DLS (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern) and z-potential analysis (Delsa™Nano C, Beckman Coulter) were used to characterize spectral properties, size, and surface charge of the nanoparticles, respectively.

For transmittance electron microscopy (TEM), samples were placed on 100-mesh, carbon-coated, formvar-coated copper grids treated with poly-l-lysine for approximately 1 hour. Samples were then negatively stained with Millipore-filtered aqueous 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min. Stain was blotted dry from the grids with filter paper, and samples were allowed to dry. Samples were then examined in a JEM 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, USA, Inc., Peabody, MA) at an accelerating voltage of 80 Kv. Digital images were obtained using the AMT Imaging System (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp., Danvers, MA). Size distribution of nanoparticles in TEM images was carried out using IMARIS software (Bitplane).

2.2 Characterization of antibody binding to 5nm gold nanoparticles

Antibodies pre-labeled with AF647 were used to quantify antibody binding based on the dye’s prominent absorbance peak at 650 nm. The number of bound antibodies was determined by measuring the difference in the 650nm absorbance between the antibody solution at the concentration used in the conjugation reaction and the supernatant, which was obtained after centrifuging antibody-conjugated 5nm AuNPs at the completion of the antibody conjugation. Then, a linear calibration curve correlating 650nm absorbance with antibody concentration was used to determine the total amount of antibodies conjugated to the nanoparticles. Finally, the number of antibodies per nanoparticle was calculated by dividing the number of antibodies by the number of 5nm AuNPs, with the latter being estimated from its optical density (OD).

Fluorescence quenching was used to measure the dissociation constant (Kd) between 5nm AuNPs and fluorescently labeled antibodies. Serial 2-fold dilutions of citrate-coated 5nm AuNPs with concentrations ranging from 105 nM to 1.6 pM in deionized water (18 MΩ) were mixed at a 1:1 v/v ratio with a 5nM solution of AF647-labeled antibodies conjugated with hydrazide-PEG-dithiol linker. Each reaction mixture was allowed to interact for 20 min at RT, and fluorescence of the AF647 dye was measured as a function of nanoparticle concentration using a Monolith NT.115 (NanoTemper Technologies); this system requires a very small sample volume (~20 µL), which greatly minimizes the amount of reagent needed for the titration curve. Using the Hill equation, the resulting data were fitted with the Monolith NT.115’s analysis software to yield a Kd. One microliter of dithiothreitol (DTT) at 1 mM in PBS was added to the 100 µL of 100 µg/mL antibody solution before mixing with AuNPs to confirm that the observed fluorescence quenching was due to thiol-mediated antibody binding to the nanoparticles.

2.3 Dark-field and fluorescence imaging of labeled cells

EGFR-positive A431 cells (human epidermoid carcinoma) and EGFR-negative MDA-MB-435 cells (human melanoma) were cultured in HyClone DMEM/High glucose (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies) in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were seeded in a Lab-Tek II Chambered Coverglass System (Nalge Nunc International) at 10,000 cells/well and incubated overnight. Then, 5nm or 40nm MAPS were added to the cells at a final concentration of 2.36 µg/mL and incubated at 37 °C. After incubation for various time periods ranging from 1 to 24 hours, the cells were washed with warm PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ to remove free nanoparticles. To quantify changes in scattering of gold nanoparticles in dark-field images, cell outlines were determined using ImageJ and signal intensities of R, G and B channels were obtained from the cell regions. A background signal was acquired outside the cells and was subtracted from the cellular signal. Then, the scattering changes associated with plasmon resonance coupling between AuNPs were quantified as a relative increase in the intensity of the red channel [38] by applying the following formula:

where R and B are scattering intensities of the red and blue channels of the color camera, respectively. Fluorescence imaging was used to characterize molecular specificity of the antibody-targeted nanoparticles. Dark-field images were acquired using a Leica DM 6000 upright microscope with a 20X 0.5 NA objective, a SPOT Pursuit XS mosaic color CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments), and a 100W halogen lamp. Fluorescence images were obtained using a CY5 filter cube with 620/60 nm excitation and 700/75 nm emission filters and a 660nm dichromatic mirror. Three independent 453 µm x 341 µm fields of view were analyzed for each sample. All optical imaging data are presented as means and standard deviations of (R/B – 1) values or fluorescence intensities from all analyzed cells for each sample.

2.4 Tissue-mimicking phantom preparation and PAI setup

Photoacoustic imaging of cells was carried out in tissue-mimicking phantoms [40] that each consisted of a gelatin background with 36 gelatin/cell inclusions. Using a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning) mold that was fabricated using a 3D-printed template, phantom backgrounds were cast to have 36 hemispherical 57µL injection wells. The phantom background was comprised of a mixture of 8% w/v gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% v/v propanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% v/v glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich); this mixture was prepared at 45°C and cooled at 4°C before removing from the PDMS mold. Gelatin/cell suspensions were then aliquoted to phantom wells in triplicate followed by deposition of a top (~3mm thick) gelatin layer. In a typical experiment, one million cells were labeled with antibody-conjugated AuNPs at ~65 µg Au for time periods ranging from 1 to 24 hours. After washing of unbound particles, the cell pellet was reconstituted in PBS and counted. For each sample, ~90 µL of a cell suspension in PBS at a desired concentration was mixed with 16% w/v gelatin in a 1:1 v/v ratio at 40°C. A Vevo 2100 LAZR (FUJIFILM VisualSonics) high-frequency ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging system equipped with a liner array transducer (LZ250; 20-MHz center frequency) was used for PAI. Volumetric (0.47mm step size) B-mode ultrasound and spectroscopic PA images were acquired at 680, 730, 740, 810, 830, and 870 nm wavelengths. For PAI analysis, each well volume, which included adjacent imaging slices, was first segmented based on its B-mode ultrasound contrast. The average PA intensity within this volume was then calculated for each sample. All reported PA intensity statistics were based on three independent but matched samples. Note that in each figure optical and PA images are displayed with the same respective dynamic range.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Characterization of 5nm gold nanoparticle antibody conjugates (5nm MAPS)

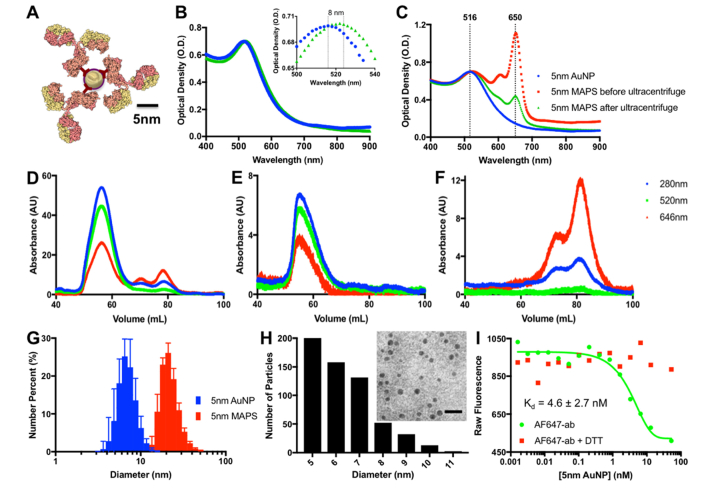

Monoclonal anti-EGFR antibodies were conjugated with 5nm AuNPs through the glycosylated Fc portion [39] using hydrazide-PEG-dithiol linkers (Fig. 1(A)). This approach allows the antigen-binding Fab moiety to be available for interactions with an antigen. Antibodies were pre-labeled with AF647 dye to allow fluorescence imaging of the conjugates and to characterize the conjugation reaction. Attachment of antibodies led to a slight red-shift in the absorbance peak of 5nm AuNPs from 516 to 524 nm (Fig. 1(B)). Further, a prominent 650nm absorbance peak associated with the AF647 dye on the conjugated antibodies was clearly seen after removal of free, unreacted antibodies (Fig. 1(C)). Using this absorbance peak, it was determined that an average of 2.7 antibodies were conjugated to each nanoparticle (see Methods for details).

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic of 5nm MAPS. (B) Absorbance spectra of 5nm AuNPs (blue), and 5nm MAPS (green); the insert shows the spectral shift of ~8 nm that is associated with antibody binding. (C) Absorbance spectra of 5nm AuNPs (blue) and 5nm MAPS conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647-labeled antibodies before (red) and after (green) ultracentrifugation. Chromatograms of 5nm MAPS before (D) and after (E) purification by ultracentrifugation and of anti-EGFR antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (F); note the absence of peaks that are associated with free antibodies in the washed nanoparticle sample (E). (G) DLS number size distribution of initial 5nm AuNP prior to functionalization and 5 nm MAPS (n = 3). (H) TEM image (inset, scale bar = 20nm) and TEM-derived size distribution of 5nm MAPS. Note that a negative 1% uranyl acetate stain was used in an attempt to visualize coating of nanoparticles. However, the contrast was not sufficient to resolve the coating, most likely due to penetration of the stain inside the coating layer. (I) Binding curves of fluorescently labeled anti-EGFR antibodies to 5nm AuNPs in the absence (green) and presence (red) of DTT.

Size-exclusion chromatography of antibody-conjugated 5nm AuNPs before and after removal of unreacted antibodies by ultracentrifugation confirmed successful washing (Fig. 1 (D-F)). DLS measurements of the citrate-stabilized 5nm AuNPs prior to functionalization and 5nm AuNPs conjugated with antibodies and mPEG molecules, referred to as “5nm MAPS,” show sizes of 7 ± 2 nm and 22 ± 6 nm, respectively (Fig. 1(G)). TEM images of 5nm MAPS reveal particles with predominantly 5 nm core size and with no sign of particle aggregation (Fig. 1(H)). Zeta potential measurements of 5nm MAPS revealed a negative 47.10 ± 0.99 mV surface charge, indicating a significant amount of residual citrate anions on the gold surface.

We noticed a partial quenching of fluorescence upon binding of antibodies labeled with AF647 dyes to the gold nanoparticles that is most likely associated with a non-radiative energy transfer to the metal surface [41,42]. We used this effect to quantify the dissociation constant of antibody binding to the nanoparticles (Fig. 1(H)). To this end, changes in intensity of fluorescence were recorded as a function of concentration of 5nm AuNPs added to a solution of fluorescently labeled anti-EGFR antibodies at a fixed concentration. These measurements resulted in a classical sigmoidal binding curve that was used to determine a Kd of 4.6 ± 2.7 nM for antibody-nanoparticle interactions. To confirm that antibody binding to AuNPs was responsible for the fluorescence quenching, DTT was added to the antibody solution before nanoparticle titration. DTT is known to effectively disturb binding of any thiolated molecules to a gold surface [43,44]. Fluorescence quenching was not observed in the presence of DTT, indicating that the observed binding curve is associated with antibody attachment to AuNPs. Previous studies reported a Kd ranging from 10 to 1,000 nM for interactions between 5nm AuNPs and various blood proteins [45]; these studies were focused on non-specific interactions that were not mediated by any conjugation chemistry. The significantly lower dissociation constant in our study indicates a stronger antibody binding through a thiolated linker [46].

3.2 Specificity of 5nm MAPS

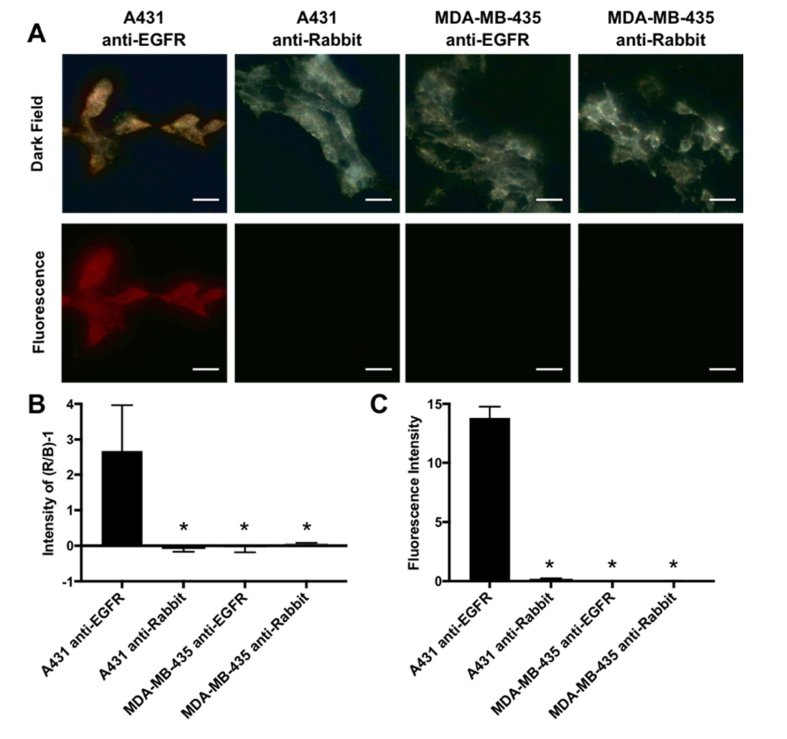

Molecular specificity of 5nm MAPS was assessed in EGFR-overexpressing A431 skin cancer cell line and EGFR-negative MDA-MB-435 melanoma cells. Both cells were labeled with either 5 nm MAPS or control 5 nm AuNPs conjugated with non-specific RG16 antibodies (RG16-AuNPs); the latter is an IgG1 monoclonal anti-rabbit antibody developed in mouse and, therefore, does not have any cross-reactivity with human or mouse antigens. Both antibodies were pre-labeled with AF647 dyes to enable fluorescence imaging. Cells were imaged using dark-field and fluorescence microscopies to concurrently detect the plasmon resonance scattering of AuNPs and the fluorescence signal from the antibodies (Fig. 2). The plasmon resonance scattering increased over time reaching its saturation after approximately 16 hours of incubation with 5 nm MAPS (Fig. 3(A) and (B)). Previously, we showed that this increase is associated with intracellular uptake and accumulation of nanoparticles in endosomal compartments that results in a progressive red shift in plasmon resonance scattering over time [38]. To quantify cell labeling with 5 nm MAPS in dark-field cell images, we used relative changes in intensity of red and blue channels of a RGB color camera by applying the following metric: [(R/B)-1], where R and B are integrated intensities of the red and the blue channels, respectively (Fig. 2(B)). Both the dark-field and the fluorescence cell images showed a strong signal after labeling of EGFR+ A431 cells with 5 nm MAPS whereas only background signal was detected in all controls including EGFR- MDA-MB-435 cells incubated with 5 nm MAPS and EGFR+ A431 cells labelled with AuNPs conjugated with RG16 antibodies (Fig. 2). The experiments were run in a triplicate, with all data sets showing a high specificity in labeling with 5 nm MAPS.

Fig. 2.

(A) Representative dark-field and fluorescence images of EGFR-positive A431 cells and EGFR-negative MDA-MB-435 cells labeled with 5nm AuNPs conjugated with either EGFR-targeting or nonspecific RG16 (anti-Rabbit) antibodies after 24 hrs incubation. (B) Relative changes in the intensity of the red (R) and blue (B) channels in dark-field images expressed as (R/B – 1). (C) Intensity of the fluorescence signal for different samples. *Denotes values that are statistically significant as compared to A431 cells labeled with EGFR-targeted 5nm AuNPs, a.k.a. 5nm MAPS (p< 0.05). Scale bar = 40 µm.

Fig. 3.

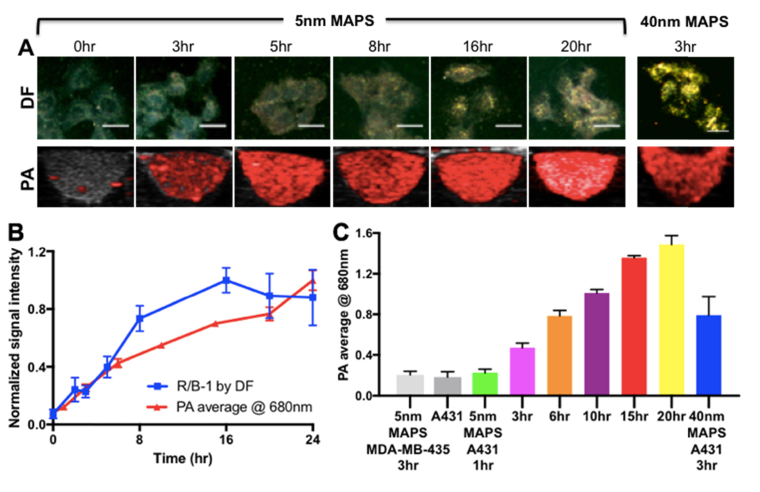

(A) Dark-field (DF) and PA images of EGFR + A431cells labeled with 5nm MAPS over various time periods. Forty nanometer EGFR-targeted AuNPs (40 nm MAPS) were used for comparison. The same dose of AuNPs (~65 µg per one million cells) was used in all experiments. All Scale bars = 40 µm. (B) Time dependence of the relative intensity of the red (R) channel in the DF images and of PA signal intensity at 680 nm from EGFR + A431 cells labeled with 5nm MAPS; the curves are normalized to 1 at their respective maximum values. (C) PA signal intensity at 680 nm of A431 cells labeled with 5nm MAPS over various time periods in comparison with the cells alone, 5nm MAPS alone and A431 cells labeled with 40nm MAPS.

3.3 Time dependence of photoacoustic imaging (PAI) with 5 nm MAPS

The PA signal of EGFR+ A431 cells was measured as a function of labeling time with 5 nm MAPS (Fig. 3). Note that RG16-AuNPs were not included in these studies because there was no detectable cell uptake of these control nanoparticles (Fig. 2). PAI of labeled cells was compared to dark-field microscopy, which is sensitive to spacing between AuNPs due to the effect of plasmon resonance coupling, as discussed above [38,47]. Note that 5nm AuNPs have a very low scattering cross-section and are indiscernible in the presence of a cellular scattering background (see earlier time points in Fig. 3(A)). PA signal gradually increased over time and showed a good correlation with changes in scattering of AuNPs (Fig. 3(B)). This close correlation suggests that clustering of AuNPs inside labeled cancer cells is responsible for the observed PA signal in the NIR spectral region. Indeed, no PA signal in the NIR range was observed from isolated 5nm AuNPs (Fig. 4(A)).

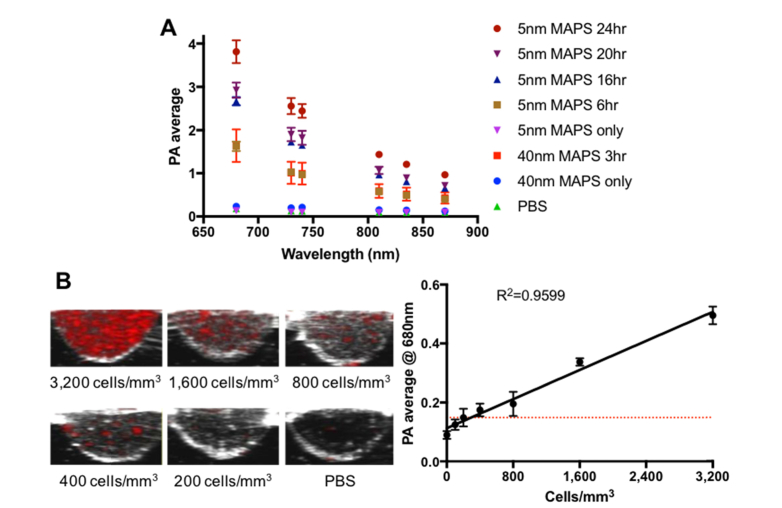

Fig. 4.

(A) PA spectra of A431 cells labeled with either 5nm or 40nm MAPS over different time periods in comparison with the nanoparticles alone. The spectra were acquired from triplicate wells per sample (n = 3). For each well, PA signal was calculated as the average value from 5 different cross-sectional images at 680, 730, 740, 810, 830, and 870 nm. (B) Representative cross-sectional images of A431 cells labeled with 5nm MAPS for 10 hours at different concentrations. A linear regression fit of PA signal intensity as a function of a number of labeled A431 cells shows a detection limit of ~200 cells/mm3, corresponding to ~11,400 cells inside a single 57µL well.

Comparison with 40nm EGFR-targeted AuNPs (i.e., “40nm MAPS”) showed the same PA signal for cells labeled with either 5nm or 40nm MAPS after 6 or 3 hours of incubation, respectively, when using the same concentration of gold by mass (Fig. 3(A),(C)). Interestingly, despite having the same PA signal, cells labeled with 40nm MAPS exhibited significantly stronger scattering as compared to those labeled with 5nm MAPS (Fig. 3(A)). This discrepancy can be explained by relationship between AuNP scattering or absorption cross-section and particle size. As size increases, the relative contributions of scattering and absorption scales as σsca/σabs≈d3 for sizes below ~80 nm diameter, where σsca, σabs and d are scattering and absorption cross-sections and nanoparticle diameter, respectively [8,34,48]. Thus, 5nm MAPS can be assumed to be purely absorbing particles, while 40nm MAPS have an appreciable scattering cross-section. Note that scattering cross-section increases as particles form closely spaced assemblies or aggregates [47].

3.4 Spectroscopic PAI sensitivity

Spectroscopic PAI of A431 cells labeled with 5nm MAPS was carried out in the NIR region (i.e., 680-870 nm) as a function of labeling time (Fig. 4(A)). PA intensity gradually decreased at longer excitation wavelengths and increased with labeling time. Interestingly, PA spectra of A431 cells incubated with 5nm MAPS for 6 hours are indistinguishable from the cells labeled with 40nm MAPS for 3 hours, indicating similar absorption properties for 5nm and 40nm AuNPs inside the cells. PA signal was not observed from either isolated 5nm or 40nm AuNPs as they individually do not present with significant absorbance in the NIR spectral range.

Sensitivity of PAI in detection of cancer cells was determined using a serial dilution of A431 cells pre-labeled with 5nm MAPS for 10 hrs (Fig. 4(B)). As expected, PA intensity exhibited a linear dependence on cell concentration. A linear regression fit was used to determine a minimum detectable cell concentration of approximately 200 cells/mm3, which corresponds to the total of ~11,400 cells inside a single 57 µL well. This value is similar to our previously reported detection limit, ~310 cells/mm3, for A431 cells labeled with EGFR-targeted 50nm spherical AuNPs [49]. Other groups have reported similar-order detection limits. For example, approximately 90,000 mesenchymal stem cells pre-labeled with 80nm silica-coated gold nanorods were detected in a muscle of a living mouse [50]. In another study, PAI was used to detect ~2000 human cardiomyocytes labeled with nanoparticles containing NIR-absorbing semiconducting polymers in a living mouse heart [51].

Serial dilution phantoms are very useful in the initial evaluation of targeted PAI contrast agents and as a point of reference in the comparison of different agents. However, it is important to note that they do not resemble tissue in vivo, where labeling of a densely packed cellular focus could produce a strong localized PA signal. Indeed, other recent studies that we have performed using PAI with 40nm MAPS show detection of metastatic foci (~50 µm) that contain significantly less than 100 cells [13]. This in vivo detection limit is considerably better than the detection limit previously demonstrated in phantoms for the same ~40nm particles [49]. Thus, using 5nm MAPS for in vivo PAI shows promise in providing even better sensitivity than their 40nm counterparts due to their potential to greatly improve delivery and tissue penetration, which has been previously reported for ultra-small nanoparticles [20,30,31].

4. Conclusion

We demonstrate the feasibility of using antibody-targeted 5nm AuNPs (i.e., “5nm MAPS”) as molecularly specific contrast agents for PAI. Similar PA signal intensity was observed for cells labeled at the same dose with either 5-nm MAPS or 40-nm MAPS, with the latter being included for comparison because of their high sensitivity in detection of cancer micrometastases in vivo [13]. However, twice longer incubation time was required for the 5nm MAPS. Interestingly, the ~2-fold increase in the incubation time was sufficient to overcome an ~500-fold difference in absorption cross-sections between the two nanoparticles. This result indicates greatly improved interaction kinetics between 5nm MAPS and live cells as compared to 40nm MAPS. This improvement might be even more prominent in in vivo conditions where smaller nanoparticles were shown to provide better tissue biodistribution, e.g. extravascular tissue penetration that is associated with improved diffusion [52–54]. Therefore, ultra-small gold nanoparticles can provide a viable option for sensitive in vivo PAI of cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ian S. Kinstlinger and Dr. Jordan Miller for assistance with design and printing of the phantom mold and CCSG grant NIH (P30CA016672) and High Resolution Electron Microscopy Facility for the use of transmission electron microscopy.

Funding

NIH (R01EB008101); CPRIT (RP170314).

Disclosures

K.V. Sokolov has ownership interest in Nanohybrids, LLC. Other authors have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

References

- 1.Li W., Chen X., “Gold nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging,” Nanomedicine (Lond.) 10(2), 299–320 (2015). 10.2217/nnm.14.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber J., Beard P. C., Bohndiek S. E., “Contrast agents for molecular photoacoustic imaging,” Nat. Methods 13(8), 639–650 (2016). 10.1038/nmeth.3929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Q., Zhu R., Song J., Yang H., Chen X., “Photoacoustic Imaging: Contrast Agents and Their Biomedical Applications,” Adv. Mater. 31(6), e1805875 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheinfeld A., Eldridge W. J., Wax A., “Quantitative phase imaging with molecular sensitivity using photoacoustic microscopy with a miniature ring transducer,” J. Biomed. Opt. 20(8), 086002 (2015). 10.1117/1.JBO.20.8.086002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X., Stein E. W., Ashkenazi S., Wang L. V., “Nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging,” Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 1(4), 360–368 (2009). 10.1002/wnan.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrmohammadi M., Yoon S. J., Yeager D., Emelianov S. Y., “Photoacoustic Imaging for Cancer Detection and Staging,” Curr. Mol. Imaging 2(1), 89–105 (2013). 10.2174/2211555211302010010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayer C. L., Chen Y. S., Kim S., Mallidi S., Sokolov K., Emelianov S., “Multiplex photoacoustic molecular imaging using targeted silica-coated gold nanorods,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(7), 1828–1835 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.001828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain P. K., Lee K. S., El-Sayed I. H., El-Sayed M. A., “Calculated absorption and scattering properties of gold nanoparticles of different size, shape, and composition: applications in biological imaging and biomedicine,” J. Phys. Chem. B 110(14), 7238–7248 (2006). 10.1021/jp057170o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu R., Tang J., Xu Y., Zhou Y., Dai Z., “Nano-sized Indocyanine Green J-aggregate as a One-component Theranostic Agent,” Nanotheranostics 1(4), 430–439 (2017). 10.7150/ntno.19935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon H. K., Ray A., Lee Y. E., Kim G., Wang X., Kopelman R., “Polymer-Protein Hydrogel Nanomatrix for Stabilization of Indocyanine Green towards Targeted Fluorescence and Photoacoustic Bio-imaging,” J. Mater. Chem. B Mater. Biol. Med. 1(41), 5611 (2013). 10.1039/c3tb21060j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Jeon M., Rich L. J., Hong H., Geng J., Zhang Y., Shi S., Barnhart T. E., Alexandridis P., Huizinga J. D., Seshadri M., Cai W., Kim C., Lovell J. F., “Non-invasive multimodal functional imaging of the intestine with frozen micellar naphthalocyanines,” Nat. Nanotechnol. 9(8), 631–638 (2014). 10.1038/nnano.2014.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmatys K. M., Chen J., Charron D. M., MacLaughlin C. M., Zheng G., “Multipronged Biomimetic Approach To Create Optically Tunable Nanoparticles,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57(27), 8125–8129 (2018). 10.1002/anie.201803535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luke G. P., Myers J. N., Emelianov S. Y., Sokolov K. V., “Sentinel lymph node biopsy revisited: ultrasound-guided photoacoustic detection of micrometastases using molecularly targeted plasmonic nanosensors,” Cancer Res. 74(19), 5397–5408 (2014). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao J. C. C., Pan F., Li C., Zhang C., Tian F., Liang S., de la Fuente J. M., Cui D., “Gold nanoprisms as a hybrid in vivo cancer theranostic platform for in situ photoacoustic imaging, angiography, and localized hyperthermia,” Nano Res. 9(4), 1043–1056 (2016). 10.1007/s12274-016-0996-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y., Liu W., Tian Y., Yang Z., Wang X., Zhang Y., Tang Y., Zhao S., Wang C., Liu Y., Sun J., Teng Z., Wang S., Lu G., “Anti-EGFR Peptide-Conjugated Triangular Gold Nanoplates for Computed Tomography/Photoacoustic Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(20), 16992–17003 (2018). 10.1021/acsami.7b19013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li P. C., Wang C. R., Shieh D. B., Wei C. W., Liao C. K., Poe C., Jhan S., Ding A. A., Wu Y. N., “In vivo photoacoustic molecular imaging with simultaneous multiple selective targeting using antibody-conjugated gold nanorods,” Opt. Express 16(23), 18605–18615 (2008). 10.1364/OE.16.018605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim C., Cho E. C., Chen J., Song K. H., Au L., Favazza C., Zhang Q., Cobley C. M., Gao F., Xia Y., Wang L. V., “In vivo molecular photoacoustic tomography of melanomas targeted by bioconjugated gold nanocages,” ACS Nano 4(8), 4559–4564 (2010). 10.1021/nn100736c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi H. S., Liu W., Misra P., Tanaka E., Zimmer J. P., Itty Ipe B., Bawendi M. G., Frangioni J. V., “Renal clearance of quantum dots,” Nat. Biotechnol. 25(10), 1165–1170 (2007). 10.1038/nbt1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu M., Xu J., Zheng J., “Renal Clearable Luminescent Gold Nanoparticles: From the Bench to the Clinic,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 58(13), 4112–4128 (2019). 10.1002/anie.201807847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen F., Ma K., Madajewski B., Zhuang L., Zhang L., Rickert K., Marelli M., Yoo B., Turker M. Z., Overholtzer M., Quinn T. P., Gonen M., Zanzonico P., Tuesca A., Bowen M. A., Norton L., Subramony J. A., Wiesner U., Bradbury M. S., “Ultrasmall targeted nanoparticles with engineered antibody fragments for imaging detection of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer,” Nat. Commun. 9(1), 4141 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-06271-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bujie Du M. Y., Zheng J., “Transport and interactions of nanoparticles in the kidneys,” Nat. Rev. Mater. 3(10), 358–374 (2018). 10.1038/s41578-018-0038-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafson H. H., Holt-Casper D., Grainger D. W., Ghandehari H., “Nanoparticle Uptake: The Phagocyte Problem,” Nano Today 10(4), 487–510 (2015). 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buzea C., Pacheco I. I., Robbie K., “Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity,” Biointerphases 2(4), MR17–MR71 (2007). 10.1116/1.2815690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourquin J., Milosevic A., Hauser D., Lehner R., Blank F., Petri-Fink A., Rothen-Rutishauser B., “Biodistribution, Clearance, and Long-Term Fate of Clinically Relevant Nanomaterials,” Adv. Mater. 30(19), e1704307 (2018). 10.1002/adma.201704307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X., Yang M., Pang B., Vara M., Xia Y., “Gold Nanomaterials at Work in Biomedicine,” Chem. Rev. 115(19), 10410–10488 (2015). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sztandera K., Gorzkiewicz M., Klajnert-Maculewicz B., “Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment,” Mol. Pharm. 16, 1–23 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuemann J., Berbeco R., Chithrani D. B., Cho S. H., Kumar R., McMahon S. J., Sridhar S., Krishnan S., “Roadmap to Clinical Use of Gold Nanoparticles for Radiation Sensitization,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 94(1), 189–205 (2016). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanco E., Shen H., Ferrari M., “Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery,” Nat. Biotechnol. 33(9), 941–951 (2015). 10.1038/nbt.3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsoi K. M., MacParland S. A., Ma X. Z., Spetzler V. N., Echeverri J., Ouyang B., Fadel S. M., Sykes E. A., Goldaracena N., Kaths J. M., Conneely J. B., Alman B. A., Selzner M., Ostrowski M. A., Adeyi O. A., Zilman A., McGilvray I. D., Chan W. C., “Mechanism of hard-nanomaterial clearance by the liver,” Nat. Mater. 15(11), 1212–1221 (2016). 10.1038/nmat4718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sykes E. A., Chen J., Zheng G., Chan W. C., “Investigating the impact of nanoparticle size on active and passive tumor targeting efficiency,” ACS Nano 8(6), 5696–5706 (2014). 10.1021/nn500299p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J., Mao W., Lock L. L., Tang J., Sui M., Sun W., Cui H., Xu D., Shen Y., “The Role of Micelle Size in Tumor Accumulation, Penetration, and Treatment,” ACS Nano 9(7), 7195–7206 (2015). 10.1021/acsnano.5b02017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath H., “Gustav Mie and the scattering and absorption of light by particles: Historic developments and basics,” J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 110(11), 787–799 (2009). 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.02.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arbouet A., Christofilos D., Del Fatti N., Vallée F., Huntzinger J. R., Arnaud L., Billaud P., Broyer M., “Direct measurement of the single-metal-cluster optical absorption,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 93(12), 127401 (2004). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.127401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tcherniak A., Ha J. W., Dominguez-Medina S., Slaughter L. S., Link S., “Probing a Century Old Prediction One Plasmonic Particle at a Time,” Nano Lett. 10(4), 1398–1404 (2010). 10.1021/nl100199h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tam J. M., Tam J. O., Murthy A., Ingram D. R., Ma L. L., Travis K., Johnston K. P., Sokolov K. V., “Controlled assembly of biodegradable plasmonic nanoclusters for near-infrared imaging and therapeutic applications,” ACS Nano 4(4), 2178–2184 (2010). 10.1021/nn9015746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon S. J., Mallidi S., Tam J. M., Tam J. O., Murthy A., Johnston K. P., Sokolov K. V., Emelianov S. Y., “Utility of biodegradable plasmonic nanoclusters in photoacoustic imaging,” Opt. Lett. 35(22), 3751–3753 (2010). 10.1364/OL.35.003751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallidi S., Larson T., Aaron J., Sokolov K., Emelianov S., “Molecular specific optoacoustic imaging with plasmonic nanoparticles,” Opt. Express 15(11), 6583–6588 (2007). 10.1364/OE.15.006583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aaron J., Travis K., Harrison N., Sokolov K., “Dynamic imaging of molecular assemblies in live cells based on nanoparticle plasmon resonance coupling,” Nano Lett. 9(10), 3612–3618 (2009). 10.1021/nl9018275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S., Aaron J., Sokolov K., “Directional conjugation of antibodies to nanoparticles for synthesis of multiplexed optical contrast agents with both delivery and targeting moieties,” Nat. Protoc. 3(2), 314–320 (2008). 10.1038/nprot.2008.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook J. R., Bouchard R. R., Emelianov S. Y., “Tissue-mimicking phantoms for photoacoustic and ultrasonic imaging,” Biomed. Opt. Express 2(11), 3193–3206 (2011). 10.1364/BOE.2.003193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swierczewska M., Lee S., Chen X., “The design and application of fluorophore-gold nanoparticle activatable probes,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13(21), 9929–9941 (2011). 10.1039/c0cp02967j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sokolov K., Chumanov G., Cotton T. M., “Enhancement of molecular fluorescence near the surface of colloidal metal films,” Anal. Chem. 70(18), 3898–3905 (1998). 10.1021/ac9712310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bisker G., Minai L., Yelin D., “Controlled Fabrication of Gold Nanoparticle and Fluorescent Protein Conjugates,” Plasmonics 7(4), 609–617 (2012). 10.1007/s11468-012-9349-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma J., Chhabra R., Yan H., Liu Y., “A facile in situ generation of dithiocarbamate ligands for stable gold nanoparticle-oligonucleotide conjugates,” Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 0(18), 2140–2142 (2008). 10.1039/b800109j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lacerda S. H., Park J. J., Meuse C., Pristinski D., Becker M. L., Karim A., Douglas J. F., “Interaction of gold nanoparticles with common human blood proteins,” ACS Nano 4(1), 365–379 (2010). 10.1021/nn9011187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ansar S. M., Haputhanthri R., Edmonds B., Liu D., Yu L., Sygula A., Zhang D., “Determination of the Binding Affinity, Packing, and Conformation of Thiolate and Thione Ligands on Gold Nanoparticles,” J. Phys. Chem. C 115(3), 653–660 (2011). 10.1021/jp110240y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aaron J., Nitin N., Travis K., Kumar S., Collier T., Park S. Y., José-Yacamán M., Coghlan L., Follen M., Richards-Kortum R., Sokolov K., “Plasmon resonance coupling of metal nanoparticles for molecular imaging of carcinogenesis in vivo,” J. Biomed. Opt. 12(3), 034007 (2007). 10.1117/1.2737351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uwe Kreibig M. V., Optical Properties of Metal Clusters (Springer, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mallidi S., Larson T., Tam J., Joshi P. P., Karpiouk A., Sokolov K., Emelianov S., “Multiwavelength photoacoustic imaging and plasmon resonance coupling of gold nanoparticles for selective detection of cancer,” Nano Lett. 9(8), 2825–2831 (2009). 10.1021/nl802929u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jokerst J. V., Thangaraj M., Kempen P. J., Sinclair R., Gambhir S. S., “Photoacoustic imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in living mice via silica-coated gold nanorods,” ACS Nano 6(7), 5920–5930 (2012). 10.1021/nn302042y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin X., Chen H., Yang H., Wu H., Zhao X., Wang H., Chour T., Neofytou E., Ding D., Daldrup-Link H., Heilshorn S. C., Li K., Wu J. C., “Photoacoustic Imaging of Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes in Living Hearts with Ultrasensitive Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles,” Adv. Funct. Mater. 28(1), 1704939 (2018). 10.1002/adfm.201704939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrault S. D., Walkey C., Jennings T., Fischer H. C., Chan W. C., “Mediating tumor targeting efficiency of nanoparticles through design,” Nano Lett. 9(5), 1909–1915 (2009). 10.1021/nl900031y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang K., Ma H., Liu J., Huo S., Kumar A., Wei T., Zhang X., Jin S., Gan Y., Wang P. C., He S., Zhang X., Liang X. J., “Size-dependent localization and penetration of ultrasmall gold nanoparticles in cancer cells, multicellular spheroids, and tumors in vivo,” ACS Nano 6(5), 4483–4493 (2012). 10.1021/nn301282m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Popović Z., Liu W., Chauhan V. P., Lee J., Wong C., Greytak A. B., Insin N., Nocera D. G., Fukumura D., Jain R. K., Bawendi M. G., “A nanoparticle size series for in vivo fluorescence imaging,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49(46), 8649–8652 (2010). 10.1002/anie.201003142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]