Abstract

While numerous studies show a persistent inverse association between religion variables and adolescents’ sexual behaviors, the nature of this relationship is not well understood. Specifically, many previous studies presuppose that the associations between adolescent religiosity and sexual behaviors are linear. However, a number of studies have also identified important nonlinearities of religious influence during adolescence, with highly religious individuals being distinct from their peers. Incorporating this knowledge into a theoretically-motivated modeling approach, this article provides a comparative analysis of functional forms describing the relationships between religiosity and adolescent sexual behaviors. Using data from two waves of the National Study of Youth and Religion, a linear functional form is compared with nonlinear alternatives that link multiple religion measures to outcomes of sexual activity. Results show that the majority of these relationships are best defined by nonlinear functional forms, suggesting that the influence of religiosity increases as individuals become more religious.

Keywords: religion, youth, adolescence, sexual behaviors, functional form

Introduction

Numerous studies have shown religious beliefs and involvement to play a major role in influencing adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviors. For example, religious youth are more likely to believe that sex should be reserved for marriage, to become sexually active at later ages, to pledge abstinence until marriage, and to have fewer sexual partners (for reviews, see Burdette, Hill, and Myers 2015; Regnerus 2007; Rostosky et al. 2004).

Despite these generally consistent findings, most past studies have modeled these relationships in ways that presuppose a linear relationship between religiosity and sex-related dependent variables (Cochran et al. 2004); that is, increases in religiosity are expected to correspond to monotonic decreases in sexual activities, regardless of how religious one is. There are theoretical reasons to believe and empirical data to suggest, however, that these relationships may actually be non-linear in functional form. Specifically, the inverse relationships between religion and sex in the aggregate may be predominately driven by a highly religious subset of individuals with especially distinctive behavior compared to their peers.

A theory-driven analysis of functional forms is needed to discern whether this is the case for the well-documented relationships between religiosity and sexual behaviors during adolescence. Specifically, this research is guided by the following questions: (1) What are the optimal forms of the relationships between religion variables and sexual behaviors during adolescence? (2) Do the optimal forms of these relationships differ by religion variable? (3) How, if at all, do the statistical and substantive interpretations of these relationships change when accounting for different functional forms?

While analyses of functional form are important for both sound empirical analyses and for theory building (e.g., Montez, Hummer, and Hayward 2012), these kinds of analyses have received relatively little attention within the sociology of religion literature, with the exception of religious affiliation differences (Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991). Accordingly, this study will not only add empirical nuance to our understanding of the well-documented relationships between religion and sex, but will also lay the groundwork to theorize why, or why not, linear and non-linear influences of religiosity appear where they do.

Theory and Background

Religious beliefs and behaviors are fairly normative during adolescence, as adolescents in the U.S. tend to have high levels of belief in God, religious affiliation, service attendance, and private religious practices (Pearce and Denton 2011; Smith and Denton 2005). Transitioning to sexual intercourse is also fairly normative during adolescence, as the estimated percentage of males and females who have had sexual intercourse increases from 16 to 75 percent and 11 to 75 percent, respectively, between the ages of 15 and 20 (Abma and Martinez 2017). Interestingly, only about a third of the adolescents between ages 15 and 19 who have not yet had sex cite religious or moral reasons for abstaining (Abma and Martinez 2017). In other words, despite the fact that the majority of U.S. teens are at least somewhat religious, the majority of them transition to sexual intercourse during adolescence, and the majority of those who do not transition do not cite religious reasons for their abstinence.

Given the well-documented negative relationships between religiosity and sexual behaviors during this time period, these findings appear somewhat paradoxical. However, they may actually be produced by two separate trends: minimal or modest influences of religion for most youth, and disproportionately large influences of religion for a small group of highly religious others. When modeled together, this latter group may be driving the relationships between religion and sex in the aggregate.

Theoretical Explanations for Nonlinearities of Religious Influence

There is great heterogeneity in the ways that religion manifests itself in individuals’ lives, if it does at all, including unorthodox ways (Ammerman 2013; Chaves 2010; Edgell 2012; McGuire 2008). Accordingly, Chaves (2010) challenges all researchers of religion to be wary of what he calls “the congruence fallacy,” which is the often-erroneous assumption that religious individuals have tightly knit and integrated belief systems, act congruently with those belief systems, and can readily apply their beliefs across contexts. Extending this idea to the relationships between religion and sex during adolescence, just because teens are religious in some way does not necessarily mean that religion will influence their sexual decisions.

To begin at the most basic level, if religion is to influence an adolescent’s sexual behavior (in a prohibitory way, consistent with past findings), it seems that, at a minimum, the adolescent would have to know what his or her religion says about sex and would have to think that those teachings should apply to him or her. Yet, adolescents tend to be both inarticulate and orthodox when it comes to their religious beliefs. Smith and Denton (2005, 134) note, “Most religious teenagers either do not really comprehend what their own religious traditions say they are supposed to believe, or they do understand it and simply do not care to believe it.” Indeed, adolescents often have little knowledge of what their religion teaches about sex, and even if they do know, they sometimes dismiss these teachings as irrelevant to their lives (Regnerus 2007).

Further, religious people do not always see their religious beliefs be in conflict with premarital sex. Regnerus (2007, 200) terms this “irrelevant religion,” illustrated succinctly by a quote from a 15-year-old Mainline Protestant who regularly attends church yet is sexually active: “I just, I don’t think you should have to wait ‘til you’re married [to have sex].” In a study of the hookup scene in college, Bogle (2008) also notes that neither religious affiliation nor religious beliefs among her interviewees make much of a difference regarding participation in the hookup culture. A practicing Catholic who participates in hookup culture and is sexually active with her boyfriend exemplifies this when she says, “I’m religious, but I still engage in premarital sex. But I don’t think that’s wrong necessarily” (Bogle 2008, 160).

Whether or not this is a theologically sound position for a given religion is irrelevant for the argument at this point. If religion and sex are not perceived to be in conflict, they become what Festinger (1957) calls irrelevant cognitive elements, with the implication of this being that cognitive dissonance should not result from their combination. This is an important point because cognitive dissonance is often a proposed mechanism that drives the negative relationships between religiosity and adolescents’ sexual behaviors (Regnerus 2007; Smith and Snell 2009; Uecker, Regnerus, and Vaaler 2007), under the assumption that individuals are motivated to reconcile inconsistencies between their beliefs and behaviors. If there is no inconsistency, there is no need for reconciliation.

Given the increase in favorable attitudes toward premarital sex over time (Twenge, Sherman, and Wells 2015) and the increasing prevalence of it (Wu, Martin, and England 2017), the assumption that religiosity and premarital sex are, in practice, at odds seems to be increasingly tenuous. Again, this is considering that, despite the macro-level attitudinal changes toward premarital sex, most adolescents and young adults are still religiously affiliated and exhibit a wide range of religious behaviors (Pearce and Denton 2011; Smith and Denton 2005; Smith and Snell 2009). It seems more plausible that a secularization of consciousness (Berger 1967) or a decline of religious authority (Chaves 1994) may have taken place in realm of sexual ethics, attenuating the extent to which sexual choices are imbued with religious meanings. If this has indeed occurred, religion should not generally be expected to make much of a difference in many adolescents’ sexual decisions, even if they are somewhat religious.

Yet there are still those youth who do consciously seek to avoid sexual behaviors for religious reasons and are motivated by a salient religious identity. It makes sense that religion would generally influence these people. Even for these youth, though, their other identities may occasionally call for incompatible behavior with their religious ones (Stryker 1968), but it would be expected that the more salient their religious identity, the more likely it is to guide behavior relative to other identities (Stryker 1968; Wimberley 1989).

Of course, adolescents’ decisions about sex are not formed in a vacuum, but are shaped by social context (Longest and Uecker 2018). Much work has been done to show that parental religiosity (Manlove et al. 2006; Thornton and Camburn 1987), religiosity of peer groups (Adamczyk 2009; Adamczyk and Felson 2006), and religious communities (Cochran et al. 2004; Longest and Uecker 2018) all influence one’s sexual attitudes and behaviors. These contextual factors often provide plausibility structures (Berger 1967; Regnerus 2007) within which youth may be embedded and may also serve as normative reference groups (Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991).

Importantly, the norms and guidance that youth receive regarding sex vary by these group memberships (Burdette, Hill, and Myers 2015; Regnerus 2007). For example, evangelical Protestant subculture is known for having especially proscriptive attitudes toward premarital sexual activity, and there are a large number of books, materials, and resources specifically geared toward encouraging sexual abstinence before (heterosexual) marriage (Burke and Hudec 2015; Gardner 2011; Irby 2013). Many youth and young adults from conservative traditions also participate in gender-specific small groups in order to share their struggles, encourage one another, and serve as accountability partners for temptations and violations of sexual prohibitions (Diefendorf 2015; Irby 2014a). The discourses within these groups signal that marriage is the critical threshold for which sexual intercourse becomes acceptable, and they also reinforce traditional gender norms regarding sexual interest, responsibility, and commitment to heterosexuality (Diefendorf 2015).

Because of this institutionalized support, oversight, and monitoring, youth from conservative religious traditions tend to have less favorable views toward premarital sexual activity (Bock, Beeghley, and Mixon 1983; Irby 2014a; Regnerus 2007). The evidence for whether or not their behaviors are different is mixed, however (Regnerus 2007; Rostosky et al. 2004); for example, many young evangelical Christians reflectively note that there is often a discrepancy between their ideal relationship behaviors (e.g., chastity) and those that play out in practice (Irby 2014a). The links between religion and sex are also not as clear for black Protestant teens, who tend to be more religious than average but not necessarily less sexually active (Burdette, Hill, and Myers 2015; Regnerus 2007).

While group memberships clearly matter, albeit not always consistently, the arguments presented previously suggest that being high in religiosity, irrespective of religious group differences, may actually be the most influential factor driving the relationships between religion and premarital sex during adolescence. For example, for those youth who are somewhat religious but not motivated to stay abstinent for religious reasons, contextual level protective factors may serve as indirect influences on their behavior, insofar as they determine unstructured free time, provide group norms, and restrict access to potential sexual partners. Importantly, though, even in the absence of these indirect and supportive influences, youth with high religious salience may still be expected to avoid sexual behaviors because their religious salience is driving their behavior and not external rewards or costs (Wimberley 1989). Thus, high religiosity may be influential on sexual behaviors despite and across contextual level factors, whereas contextual level factors would not be expected to make a consistent difference on sexual behaviors when religiosity is absent or non-salient.

In sum, the theoretical arguments presented thus far support the idea that religious influence, for a variety of potential reasons, may not operate monotonically across adolescents on outcomes of sexual behavior. Yet, the consistent thread through these arguments is that the most religious youth are disproportionately likely to benefit from them – through religious knowledge, internalization and application of religious teachings about sex, drives for internal consistency, salient religious identities relative to other identities, and scaffolding available through social context. Not all of these can be tied to conservative religious affiliations, but they do seem likely to follow closely from high religiosity. Thus, high religiosity may provide multi-layered influences that go beyond the normative levels of religious belief and behavior among teens, which we know also must coexist to a large extent with transitions to sexual activity.

The available empirical evidence suggests that this may in fact be the case. Across a range of outcomes, data sets, and methodological techniques, Smith and Faris (2002), Smith and Denton (2005), Pearce and Denton (2011), Wallace and Forman (1998), Regnerus and Elder (2003), Regnerus (2007), and Pedersen (2014) all provide examples of the most religious adolescents being distinct from their peers, even those with moderate amounts of religiosity. This is noted by Smith and Denton (2005), who state, “Mere sporadic investments and involvements by teens in religion usually prove indistinguishable in outcomes from those of teens who are completely disengaged from religion…A modest amount of religion, in other words, does not appear to make a consistent difference in the lives of U.S. teenagers” (2005, 232–33).

While functional form tests of these relationships have been done with respect to religious groups, motivated in part to overcome presumptions of linear influence in much of the literature (Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991), there have not been analogous studies done which focus on the optimal functional form of individual religion variables, which may also be nonlinear. Given the grounding for such nonlinearities theoretically, and the evidence of nonlinearities in the literature, such a contribution would be useful.

Conceptualizing the Optimal Form of Religious Influence

In light of the preceding arguments, functional forms of the relationship between religion and sex during adolescence should be tested that allow highly religious individuals to be distinct from their peers. This can be accomplished in at least four ways: 1) allowing for a unique effect of religiosity at any level of religiosity, 2) allowing for an additive effect of high religiosity, 3) allowing for both an additive and multiplicative effect of high religiosity, and 4) allowing for a gradually increasing effect of religiosity. All of these alternatives will be tested here and compared to a linear form of religiosity. The second and third of these four approaches require a demarcation of “high religiosity” for model estimation, which will be discussed in the next section. The equations for these models are shown in Table 1 and then explained below, following closely the precedent set by Montez et al. (2012) in their analysis of functional forms.

Table 1.

Predetermined Functional Forms of the Relationship between a Religion Variable and an Outcome using Binary Logistic Regression

| Model 1. | Continuous |

| log[p/(1-p)] = α + β0Z + β1(religion) | |

| Model 2. | Step change with zero slopes |

| log[p/(1-p)] = α + β0Z + β1(religioncat1) + β2(religioncat2) … βk(religioncatk) | |

| Model 3. | Step change with a constant slope |

| log[p/(1-p)] = α + β0Z + β1(religion) + β2(high religion) | |

| Model 4. | Step change with a varying slope |

| log[p/(1-p)] = α + β0Z + β1(religion) + β2(high religion) + β3(religion*high religion) | |

| Model 5. | Quadratic change |

| log[p/(1-p)] = α + β0Z + β1(religion) + β2(religion2) |

Notes. Logistic regression is used for these examples because it is used for two of the three dependent variables (intimate touching and sexual intercourse). Negative binomial regression is used for number of sexual partners. Z represents a vector of control variables. See text for a full description of these models.

Model 1: Continuous model.

For this model, religion variables are specified as continuous (e.g., coded with values such as 0–5) and entered into each model as a single term without alterations. It is assumed that the influence of religiosity is the same for every increase in religiosity, regardless of where that change occurs on the religiosity continuum.

Model 2: Step change with zero slopes.

The second model allows for each unique value of a religion variable to have its own association with the dependent variable. In other words, every change in religiosity is allowed to be unique, including those for the highest values, because no predetermined shape is imposed on the data. This is accomplished by entering each religion variable into the models as a series of dummy variables, one for each level of the variable, which are then compared to the omitted referent category.

Model 3: Step change with constant slope.

The third model is specified such that there is a step-change for highly religious individuals compared to their counterparts. The influence of additional religiosity is the same for both groups (i.e., the slope is the same), but there in an additive effect of high religiosity (an intercept shift). This is captured analytically by adding a dummy variable to the model for high values of religiosity.

Model 4: Step change with varying slope.

The fourth approach builds on the third and can be described as a step change with a varying slope. The step change from the previous model remains the same: highly religious individuals receive an additive effect of religiosity for being highly religious. However, in this model, the influence of religiosity beyond the first value of high religiosity now has its own slope. This is accomplished analytically by adding an interaction term between the continuous variable for religiosity and the dummy variable for high religiosity.

Model 5: Quadratic change.

The fifth and final model is one that models quadratic change. This is accomplished analytically by adding a squared term for each religion variable to the continuous term. This squared term allows for increasing or decreasing marginal effects; that is, the effect of each religion variable is allowed to increase or decrease at higher values of that variable, forming a full or partial curve from a parabola (Wooldridge 2009).

Data and Methods

Data from the first two waves of the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR) are used for analyses. The NSYR is a nationally representative telephone survey of 3,290 English and Spanish-speaking youth and their parents conducted between 2003 (Wave 1) and 2015 (Wave 4). Also included in the NSYR is an oversample of 80 Jewish households, which are not nationally representative, and which bring the total sample to 3,370 respondents. Respondents were initially contacted using a random-digit-dial (RDD) method representative of all household telephones in the United States. Eligible households contained at least one teenager between the ages of 13–17 living in the household for at least six months of the year. Of the 3,370 original respondents, 2,604 completed Wave 2, for a retention rate of 78.6 percent. Additional information about the NYSR, including its design and collection, can be found at youthandreligion.edu and from National Study of Youth and Religion (2008).

For this study, data from Waves 1 and 2 are used for analyses. After excluding the non-representative Jewish oversample, individuals who recanted having had sex by Wave 1 in their Wave 2 survey, individuals who reported fewer sex partners at Wave 2 than at Wave 1, and those missing on any of the variables of interest, the analytic sample for Wave 1 comes to 3,128 individuals. This is about 95 percent of the original sample, excluding the Jewish oversample. For the analysis of change in sexual behaviors between Waves 1 and 2, the sample is further limited. From the 2,347 respondents in Wave 2, ever-married individuals are removed and so are those whose change in age between waves is other than two or three years. This latter restriction removes one percent of the eligible sample but also allows for comparisons between those with similar developmental changes. It also keeps similar the time between recall of sexual behaviors and sexual partners. Thus, the analytic sample for transitions by Wave 2 is 2,289 (about 98 percent of the Wave 1 sample not lost to attrition between waves). However, two of the three dependent variables at Wave 2 are transitions from Wave 1, and only those individuals able to transition can be included in those analyses. This bring the sample to 1,565 individuals able to transition to intimate touching between waves and 1,904 individuals able to transition to sexual intercourse. All 2,289 individuals from Wave 2 are included for the change in sexual partners.

Dependent Variables

Measures of sexual behaviors.

For robustness against idiosyncrasies in the functional form of any particular sexual behavior, three different outcomes are used here: engagement in intimate touching, engagement in sexual intercourse, and number of sexual partners. It should be noted here that these measures do not distinguish between opposite-sex and same-sex behaviors, and that there is no measure of sexual orientation on the NSYR. These limitations are revisited in the discussion section.

The first measure is a dichotomous variable that follows responses to the question: “Have you ever willingly touched another person’s private areas or willingly been touched by another person in your private areas under your clothes, or not (0-No, 1-Yes)?” Another dichotomous measure indicates whether respondents have ever had sexual intercourse, obtained from the question, “Have you ever had sexual intercourse, or not (0-No, 1-Yes)?” Lastly, the number of respondents’ sexual partners is measured by the question, “With how many different people have you ever had sexual intercourse (0–100)?” This variable is censored at “10 or more.”

Independent Variables

Five focal religion variables will be used, including four fairly standard individual measures of religiosity (see The Association for Religion Data Archive’s (2018) “Measurement Wizard” for examples) – religious service attendance, importance of religious faith, prayer frequency, and closeness to God. The fifth variable is a summative index that combines these other four, mirroring many other scales of religiosity that have been developed for analyses (Hill and Pargament 2017; The Association of Religion Data Archives 2018). While the NSYR contains additional religion variables that could be used either individually or as part of an index, many of them are either not available in other large data sets, have dissimilar scales, or lack enough response options (e.g., dichotomous indictors) to allow for the internal variation that is of particular interest here. Thus, for practicality, parsimony, and reproducibility, these analyses are limited to four measures and the index created by them.

Religious service attendance ranges from 0 to 6 and follows responses to the question, “About how often do you usually attend religious services (never, a few times a year, many times a year, once a month, two to three times a month, once a week, or more than once a week)?” The importance of religious faith ranges from 0 to 4 and follows responses to the question, “How important or unimportant is religious faith in shaping how you live your daily life (not important at all, not very important, somewhat important, very important, or extremely important)?” Prayer frequency ranges from 0 to 6 and follows responses to the question, “How often, if ever, do you pray by yourself alone (never, less than once a month, one to two times a month, once a week, a few times a week, once a day, or many times a day)?” Closeness to God ranges from 0 to 5 and follows responses to the question, “How distant or close do you feel to God most of the time (extremely distant, very distant, somewhat distant, somewhat close, very close, or extremely close)?” Respondents who report that they do not believe in God are coded as the lowest value (0), which is feeling “extremely distant” from God. These four variables are also used to create a summative index of religiosity that ranges from 0 to 21 (α = .763).

High religiosity.

A dummy variable for each of the five religion variables indicates those with “high” scores (0-No, 1-Yes). For the religiosity index (0–21), the cut-off is informed by the empirical studies cited earlier which have shown nonlinearities of religious influence at or beyond the highest 35 percent of values. This corresponds to values from 15 to 21 on the index, which includes about 37 and 38 percent of respondents for Wave 1 and Wave 2, respectively. Alternative cut-points for this index, with minimum values needed for “high” changed to 14 and 16 (varying the “high” sample between 29 and 46 percent), have been tested but do not change the substantive results. For the four individual religion variables, the top two values are considered “high.” This allows for variation within the high group, which is necessary for the step change - varying slope functional form. High values correspond to weekly or more service attendance (values of 5 or 6), very or extremely important religious faith (3 or 4), daily or more prayer (5 or 6), and feeling very or extremely close to God (4 or 5). This demarcation assigns between 37 and 41 percent of respondents to “high” values, except for the importance of religious faith, for which 51 percent of respondents have “high” values. An interaction term is also created between each of the five measures of religiosity and its “high” dummy.

Control Variables

For every combination of models between the religion variables and outcomes of sexual activity, two sets of control variables are used. First, for what will be termed the base models, only age (in years) is used as a control variable. Excluding age could introduce significant confounding between religiosity and sexual behaviors, given that religiosity tends to decrease throughout adolescence (Pearce and Denton 2011; Smith and Snell 2009) and that the onset to sexual behaviors is highly dependent on, and linearly related to, age (Abma and Martinez 2017). With only this one control, these models best approximate the gross functional form of the relationships between religiosity and sexual behaviors, net of the time individuals spend “at risk” of engaging in sexual behaviors, and irrespective of any mediating pathways.

Second, since the relationships between religion and sex are known to vary by other factors, I also estimate controlled models to adjust for potential confounders and mediating pathways. Specifically, these models control for respondents’ gender, race, religious tradition, region, youth group participation, family structure, parental religious tradition, and parental attitudes toward sex before marriage. These variables were chosen because of both their theoretical relevance, as discussed in the previous sections, and because they may explain non-linearities in the preferred functional forms from the base models. For example, if the most religious youth tend to be driving the inverse relationships between religion and sex in the aggregate, then controlling for characteristics that may explain both high religiosity and less sexual activity should mitigate any model preferences for non-linear functional forms. Supplemental analyses (not shown) also controlled for household income and highest parental education, but these inclusions did not change the substantive results. In the interest of parsimony, these two variables were not included in the final controlled models just described.

Analytic Strategy

A combination of binary logistic regression and negative binomial regression will be used for analyses. The former is used for the dichotomous outcomes, intimate touching and having had sex, and controls for age, while the latter is used for the count outcome, number of sexual partners, and treats age as the exposure variable. The negative binomial regression model is preferred to the Poisson regression model in these analyses due to significant evidence of overdispersion in the data (Long 1997). All final models are unweighted, though weight association tests were conducted (Bollen et al. 2016; DuMouchel and Duncan 1983) and did not show that the focal religion variables required weights. Therefore, the unweighted estimators were chosen due to their greater efficiency (Bollen et al. 2016).

The analysis begins with the cross-sectional data from Wave 1. For each independent and dependent variable combination, the five models from Table 1 are estimated, and all models control for age alone (the base models). In Model 1, each religion variable is used solely as a continuous variable. In Model 2, each religion variable is entered as a series of dummy variables, one for each unique value of the variable (minus the omitted category). In Model 3, each continuous religion variable is entered along with its dummy variable for “high” values. In Model 4, the interaction term is added between the linear variable and the dummy variable. Finally, Model 5 contains the continuous version of each religion variable along with a squared version of it. These exact models are then re-estimated using the full set of control variables (the controlled models). If non-linear functional forms in the base models can be explained away by the controls added here, we would expect to see these controlled models show a stronger preference for continuous functional forms.

Because any nonlinearities resulting from the Wave 1 analysis may reflect selection processes that occurred prior to Wave 1, an analysis of change between Wave 1 and Wave 2 is also conducted. For this analysis, all religion indicators at Wave 1 are used to predict transitions to intimate touching, transitions to sexual intercourse, and changes in number of sexual partners between waves. The sequence of Models 1 through 5 is the same as the first part of the analysis, for both the base and controlled models. The only difference is that age at Wave 1 is replaced by two variables, age at Wave 2 and the change in age between waves, with the latter functioning as the exposure variable when predicting changes in sexual partners.

To compare models to one another, three different information criteria are used: Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (ABIC). They all follow the form of Expression 1:

| (1): |

where l is the log-likelihood of the model and Anp is the penalty term for model complexity (Dziak et al. 2012). An varies by criterion and is either a constant or function of the sample size, while p is the number of parameters in the model. Each of the three criteria use a different value of An, prioritizing sensitivity and specificity differently (Dziak et al. 2012). For example, in these analyses, the AIC has the smallest penalty term of the three, making it the most sensitive and most likely to overfit the models. The BIC has the largest penalty term, making it the most specific and most likely to underfit the models. The ABIC has a penalty term value between the two. For thoroughness and robustness to the strengths and weaknesses of any individual criterion, I use all three to inform the choice of the preferred model.

In order to choose the preferred model for each combination of independent and dependent variables, the models are first ranked one (best) through five (worst) for each criterion, with lower values indicating a better fit (Dziak et al. 2012; Long 1997). I then calculate an average criterion ranking for each combination by averaging the ranks of the AIC, ABIC, and BIC, with the lowest value indicating the preferred model. Thus, the best possible average is one, indicating that a particular model is preferred for each criterion; conversely, the worst possible average is 5, indicating that a particular model is the least preferred for each criterion. In the case of ties for the lowest value, model preference is given to model with the lowest BIC ranking, since that criterion has the heaviest penalty of the three for model complexity (Dziak et al. 2012). This is done for both the base and controlled models.

For the final part of the analysis, I use the continuous models and preferred models from the Wave 1 analysis to produce predicted probabilities of intimate touching by each religion variable. All predicted values hold age constant at 15 and are produced from the base models. These predicted values are then graphed to illustrate differences between functional forms.

Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. As shown in the table, religion is clearly present in the lives of these adolescents. The average score for the religiosity index is 12.05 out of 21. The mean values for the other religion variables correspond to religious service attendance of just over once a month, a “somewhat” to “very” important religious faith, prayer frequency of about once per week, and feeling “somewhat” close to God. Individuals present for the Wave 2 analysis have similar values on the religion variables at Wave 1 compared to the larger sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of All Variables

| Wave 1 (N=3,128) | Wave 2 (N=2,289)2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Range | Mean or % | SD | Range | Mean or % | SD |

| Religion Variables | ||||||

| Religiosity index1 | 0–21 | 12.05 | 5.22 | 0–21 | 12.17 | 5.26 |

| Religious attendance1 | 0–6 | 3.16 | 2.19 | 0–6 | 3.24 | 2.18 |

| Importance of faith1 | 0–4 | 2.46 | 1.12 | 0–4 | 2.47 | 1.13 |

| Frequency of prayer1 | 0–6 | 3.37 | 2.00 | 0–6 | 3.38 | 1.98 |

| Closeness to God1 | 0–5 | 3.06 | 1.27 | 0–5 | 3.08 | 1.26 |

| Sexual Behavior Outcomes | ||||||

| Has had intimate touching | 0–1 | 34% | - | - | - | - |

| Transition to intimate touching | - | - | - | 0–1 | 57% | - |

| Has had sexual intercourse | 0–1 | 21% | - | - | - | - |

| Transition to sexual intercourse | - | - | - | 0–1 | 43% | - |

| Number of sexual partners | 0–10 | .56 | 1.56 | - | - | - |

| Change in number of sexual partners | - | - | - | 0–10 | 1.60 | 2.55 |

| Individual Controls | ||||||

| Age (years) | 13–17 | 15.01 | 1.40 | 16–20 | 17.65 | 1.34 |

| Change in age between waves | - | - | - | 2–3 | 2.71 | .45 |

| Gender (female)1 | 0–1 | 50% | - | 0–1 | 51% | - |

| Race1 | ||||||

| White | 0–1 | 66% | - | 0–1 | 71% | - |

| Black | 0–1 | 17% | - | 0–1 | 15% | - |

| Hispanic | 0–1 | 12% | - | 0–1 | 9% | - |

| Other | 0–1 | 5% | - | 0–1 | 5% | - |

| Religious tradition1 | ||||||

| Conservative Protestant | 0–1 | 32% | - | 0–1 | 33% | - |

| Mainline Protestant | 0–1 | 11% | - | 0–1 | 12% | - |

| Black Protestant | 0–1 | 12% | - | 0–1 | 11% | - |

| Catholic | 0–1 | 25% | - | 0–1 | 24% | - |

| Other | 0–1 | 8% | - | 0–1 | 9% | - |

| Unaffiliated | 0–1 | 12% | - | 0–1 | 11% | - |

| Lives in the south1 | 0–1 | 42% | - | 0–1 | 41% | - |

| Youth group participation1 | 0–1 | 38% | - | 0–1 | 40% | - |

| Parental and Family Controls | ||||||

| Parental religious tradition1 | ||||||

| Conservative Protestant | 0–1 | 32% | - | 0–1 | 33% | - |

| Mainline Protestant | 0–1 | 15% | - | 0–1 | 16% | - |

| Black Protestant | 0–1 | 14% | - | 0–1 | 12% | - |

| Catholic | 0–1 | 25% | - | 0–1 | 24% | - |

| Other | 0–1 | 9% | - | 0–1 | 9% | - |

| Unaffiliated | 0–1 | 6% | - | 0–1 | 6% | - |

| Parental support of abstinence1 | 0–1 | 61% | - | 0–1 | 61% | - |

| Married biological parents1 | 0–1 | 54% | - | 0–1 | 59% | - |

Source: National Study of Youth and Religion, Waves 1–2.

From Wave 1.

The sample size is smaller for the transition to intimate touching (N = 1,565) and the transition to sexual intercourse (N = 1,904), since only those who had not engaged those behaviors by Wave 1 were eligible to transition to them. The full sample (N = 2,289) is used for changes in sexual partners, since everyone was able to experience a change, even if they did not.

Approximately 34 percent of respondents have engaged in intimate touching by Wave 1, about 21 percent of them have had sexual intercourse, and the mean number of sexual partners is .56. Of those who had not yet engaged in intimate touching or sexual intercourse by Wave 1, 57 percent and 43 percent transition to those behaviors by Wave 2, respectively. The mean change in the number of sexual partners between waves is 1.60. The mean age at Wave 1 is 15.01 and the mean age at Wave 2 is 17.65.

Table 3 presents the summary results from the Wave 1 analysis. In order to summarize information most efficiently, only the average model ranks are shown, and gray shading is used to highlight the preferred models. The full models and criterion rankings that are not shown due to space limitations are available from the author upon request.

Table 3.

Summary of Model Preferences for Sexual Behaviors at Wave 11

| Touching Ever | Sex Ever | Sex Partners | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Variables | Base | Controlled | Base | Controlled | Base | Controlled |

| 1) Religious Index | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 2) Service Attendance | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 3.3 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 4.3 | 4.3 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 3) Importance of Faith | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 3.3 |

| 4) Prayer Frequency | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.3 |

| 5) Closeness to God | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.0 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

N = 3,128 for all outcomes.

Notes. Table cells contain the average rank of model preferences for the AIC, ABIC, and BIC, which are individually ranked 1 (best) through 5 (worst) for each combination of independent and dependent variable (not shown). Cells with gray shading indicate the preferred models, or the models with the lowest average rank across criterion. In the case of ties, preference is given to the model with the lowest BIC ranking. The base models contain only age as a control variable or exposure variable, while the controlled models contain a host of other variables. See text for a full description of these models.

For the religious index, the preferred functional form for predictions across the three dependent variables, according to the average model rank, is the quadratic change form. This is case for both intimate touching and sexual partners, regardless of whether it is the base model or the fully controlled model. For having had sex, the preferred functional form is quadradic change for the base model, but this preference switches to the step change - varying slope form for the fully controlled model. Notably, the continuous functional form is not preferred at all.

Religious service attendance and the importance of religious faith have similar patterns to each other, so they will be considered together here. For both of them, when predicting intimate touching, the quadratic change functional form is best. This is the case for the both the base and controlled models. For predicting sexual intercourse and the number of sexual partners, the preferred functional forms for both of these variables becomes the continuous model. This does not vary between the base and controlled models. Interestingly, for six of the eight occasions here in which the continuous model is preferred, there was a tie between two functional forms, and the continuous form was selected by the lowest BIC rank. This is notable because there are very close (non-linear) second choices for these combinations.

The last two religion variables in the table, prayer frequency and closeness to God, also have similar results to each other and will be discussed jointly. For both of them, when predicting intimate touching and sexual intercourse, the step change - varying slope functional form is preferred. This is the same for all models, base and controlled. For sexual partners, the continuous functional form is best for prayer frequency, in both the base and fully controlled models. For closeness to God, the step change - varying slope functional form is best for the base models, but the addition of controls in the controlled models switches this preference to the continuous functional form.

In sum, across all model combinations, three different functional forms are preferred: continuous, step change - varying slope, and quadratic change. Individually, they are all preferred about equally as often, or about one third of the time. Stated differently, the continuous functional forms only fit the models best about one third of the time, with nonlinear forms that allow the slope of religiosity to change at higher values preferred about two thirds of the time.

Because these results are cross-sectional, they are limited in their ability to account for selection processes that happened prior to the survey that could also be driving functional form preferences. To help overcome this shortcoming, the next part of the analysis uses religion variables at Wave 1 to predict transitions to intimate touching, transitions to sexual intercourse, and changes in the number of sexual partners by Wave 2. These results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Model Preferences for Sexual Transitions between Waves 1 and 21

| Transition to Touching | Transition to Sex | Change in Sex Partners | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Variables | Base | Controlled | Base | Controlled | Base | Controlled |

| 1) Religious Index | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.7 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| 2) Service Attendance | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 4.7 | 4.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.3 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 2.7 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 3) Importance of Faith | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.0 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 3.0 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 4) Prayer Frequency | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| 5) Closeness to God | ||||||

| M1. Continuous | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| M2. Step Change, Zero Slopes | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| M3. Step Change, Constant Slope | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| M4. Step Change, Varying Slope | 1.7 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| M5. Quadratic Change | 2.0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

N = 1,565 for transition to touching, 1,904 for transition to sex, and 2,289 for change in sex partners.

Notes. Table cells contain the average rank of model preferences for the AIC, ABIC, and BIC, which are individually ranked 1 (best) through 5 (worst) for each combination of independent and dependent variable (not shown). Cells with gray shading indicate the preferred models, or the models with the lowest average rank across criterion. In the case of ties, preference is given to the model with the lowest BIC ranking. The base models contain only age and change in age between waves as control variables or exposure variables, while the controlled models contain a host of other variables. See text for a full description of these models.

Overall, the results from Table 4 are fairly similar to those of Table 3. The religious index, which almost always performed best in the quadric change form at Wave 1, exhibits the same preference. For each dependent variable, in both base and controlled models, the quadratic change form performs best. Religious service attendance, on the other hand, has slightly different preferences compared to Wave 1. The preference for the transition to sexual touching is the same: quadratic change. For the transition to sex and changes in sexual partners between waves, however, the preferred form alternates between the step change - varying slope form and the quadratic change form. This is a departure from Wave 1, when the continuous models performed best for these two outcomes. Recall, however, that all four of those preferences were ties decided by lowest BIC rank, indicating that an alternative form was about equally as preferred.

The importance of religious faith does not exhibit a clear pattern of functional form preferences in these models. When predicting intimate touching, the preferred form is the step change - constant slope form for the base models and continuous form for the controlled models. This is the only time across all analyses that the step change - constant slope form is preferred for any model. Again, though the continuous form is preferred with the controlled models, it results from a tie decided by lowest BIC rank. The preferred form when predicting transitions to sexual intercourse is the quadratic change form, but the preferred form for predicting sexual partners is the continuous form. Overall, the preferred forms for this particular variable appear inconsistent.

The preferred forms for prayer frequency and closeness to God are the same, so they will be considered together. With only one exception, across base and controlled models for the three dependent variables, the preferred form is the step change - varying slope form. The one exception is for the controlled models for intimate touching, for which the quadratic change models are preferred. These are slight differences from the Wave 1 analysis, with the most notable difference being the shift from continuous form preferences for sexual partners to the step change - varying slope preferences.

In sum, the results from Table 4 are similar to the results of Table 3, but with some important differences. Four different functional forms are preferred, though one of them (the step change - constant slope) is only preferred once. The continuous forms are only preferred three times across all combinations, and all of these are for the importance of religious faith. The remaining functional form preferences are about equally divided between the step change - varying slope form and the quadratic change form.

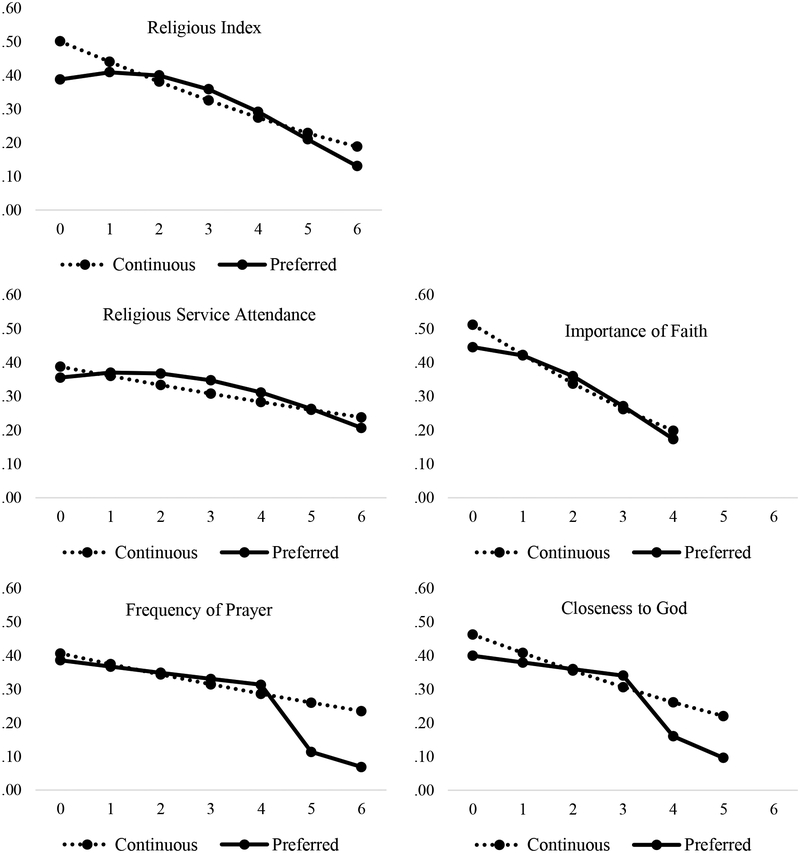

To illustrate how these model preferences may affect prediction, and to help visualize the distinctions between functional forms, Figure 1 is presented below. This figure presents predicted probabilities of intimate touching at Wave 1 for both the continuous and preferred functional forms of all five religion variables. I use estimates from the base models (the left-most column of Table 3) to create these probabilities with age equal to 15 (the mean). Note that a graphic like this could be created for the other two outcomes, as well, with or without control variables, but the same general concepts would be illustrated.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities of Intimate Touching for 15-year-olds by Religion Variables in Continuous and Preferred Functional Forms

Notes. The religious index ranges from 0–21 but has been rescaled to 0–6 for the figure. The other religion variables are kept in their original metrics; see the text for more information.

Beginning at the top left of the figure, we can observe the relationship between the religious index and the predicted probability of intimate touching. (The religious index has been rescaled for the figure.) When modeled continuously, there is a clear negative relationship between these two variables; as religiosity increases, the probability of engaging in intimate touching decreases. This decrease is monotonic, or about the same for every increase in religiosity. When this relationship is modeled using the preferred quadratic change form, however, which allows for increasing effects of religiosity, the story is slightly different. Increases in religiosity, at lower levels of religiosity, do not correspond to decreases in the probability of intimate touching. Rather, the graph is fairly flat for about the bottom third to bottom half of values. After this point, however, increases in religiosity are associated with increasingly lower probabilities of intimate touching.

The graphs for religious service attendance and the importance of faith illustrate the same concept. For each of these, like the religious index, the preferred functional form is quadratic change. Estimates from the continuous functional forms produce linear and negative associations between each of these variables and the probabilities of intimate touching. For the preferred forms, though, the negative slope is flatter at the lower values of each variable (more so for religious attendance) and then steepens as values increase.

Lastly, the bottom two graphs depict the associations to intimate touching for both prayer frequency and closeness to God. For these variables, the preferred functional forms are the step change - varying slope forms. For frequency of prayer, the continuous form and the preferred form produce similar estimates up until values of five (corresponding to praying about once per day). At this point, there is a “step change,” which allows for an additive effect of high values, and this explains the sudden drop in probabilities. The slope also becomes steeper after this point than it was across lower values (“varying slope”). The graph for closeness to God is very similar and can be interpreted in the same way.

In review, the results presented in this section support the earlier contention that the relationships between religiosity and sexual behaviors would be nonlinear in functional form, with the effects of religiosity increasing as religiosity increases. Even the BIC, which has the largest penalty term for model complexity of the criterion used here, only preferred the continuous forms on 34 out of 60 possibilities (not shown), with 12 of those coming from just the importance of religious faith. While the full models with coefficients have not been shown due to space limitations, the nonlinearity in all of these cases suggests that the relationships grow stronger as religiosity increases. Figure 1 depicts how these models deviate, particularly at high values of religiosity, from continuous modeling approaches.

Discussion

The functional forms of religious influence have heretofore been given little attention (Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991). As a result, religion variables have predominately been conceptualized and used as continuous measures in previous research. The primary argument of this paper is that such an approach could be masking non-uniformities of religious influence, particularly for the relationships between religion and sex during adolescence. Specifically, the most religious adolescents may be distinct enough from their peers to warrant special analytical attention. To test this idea here, five religion variables have been used to predict three different outcomes of sexual behaviors with five different functional forms.

Corresponding to the first research aim, the primary contribution from these analyses is the finding that continuous measures of religiosity rarely provide the optimal functional form for outcomes regarding sexual behavior. Instead, nonlinear forms are preferred the majority of time, but specifically the nonlinear forms that model either a step change with a varying slope or quadratic change. These nonlinear forms allow the influence of religiosity to increase as individuals become more religious and received substantial support. These findings hold for both the base models, which only control for age, and for the fully controlled models, which control for a host of other factors, including religious affiliation.

The preferred models did vary by religious indicator, however, which was another contribution motivated by the second research aim. For the religiosity index, the optimal functional form was generally the quadratic change model. The optimal forms for service attendance and important of faith were less clear, varying between continuous, step change - varying slope, and quadratic change preferences, depending on the outcome. Finally, both prayer frequency and closeness to God were best modeled by the step change - varying slope approach.

Finally, to address the third research aim, these analyses show that accounting for nonlinear functional forms often changes the interpretation of religious influence. For example, instead of assuming a monotonic change in an outcome as religiosity increases, as with the continuous forms, the step change - varying slope models allow for both an additive and multiplicative effect of high religiosity. In these analyses, this was illustrated by lower odds of intimate touching and sexual intercourse, and lower expected counts of sexual partners, at both the first value of high religiosity and as the values of religiosity increased beyond that point. The quadratic change models allow for a gradual increase in the effect of religiosity as religiosity increases. In these analyses, this was illustrated by increasingly lower odds of intimate touching and sexual intercourse, and increasingly lower expected counts of sexual partners, as values of religiosity increased. For both of these cases, the statistical association and interpretation is not constrained to be the same for those low and high in religiosity, which improved most models.

Despite the general preference for nonlinear forms, the differences among functional form preferences by religious indicator warrant potential explanations here. Methodologically, the scales of the four religion variables (excluding the index) are similar but not exactly the same, and this could cause functional form differences. Additionally, the top two values were considered “high” for each of these variables in order to allow for variation (i.e., a slope) between them. For all but the importance of religious faith, the top two values contained between 37 and 41 percent of respondents. For the importance of religious faith, just over 50 percent of respondents had “high” values. Accordingly, this variable may have lacked general variation and may have too loosely defined the “high” group to discern a strong distinction between those respondents and others. Theoretically, each variable may be measuring something unique, and thus functional form differences may reflect actual differences in mechanisms. For example, Pearce, Hayward, and Pearlman (2017) argue that religious service attendance, importance of faith, and prayer frequency all correspond to different dimensions of religiosity – external practice, religious salience, and personal practice, respectively. These underlying latent variables may also be driving functional form differences.

Perhaps the most important issue that remains to be addressed is that of why religiosity seems to be disproportionately influential for the most religious adolescents compared to others. To begin, part of the explanation may simply be demographic. Many adolescents will essentially select into religion due to intergenerational transmission of religiosity from their parents (Bengtson, Putney, and Harris 2013; Smith and Denton 2005), and many of these adolescents will also select out of religion during late adolescence or young adulthood (Pearce and Denton 2011; Smith and Snell 2009; Uecker, Regnerus, and Vaaler 2007). Thus, some religious youth who selected into religion early in life may engage in sexual behaviors before selecting out of religion, weakening the relationship between religion and sex for those with lower levels of religiosity. Additionally, attitudes and trends toward premarital sex and delayed marriage (Ruggles 2015; Wu, Martin, and England 2017; Twenge, Sherman, and Wells 2015) may have made it both non-normative and unreasonable for young people to wait until their mid-to-late 20s to have sex for the first time. If only the most devoutly religious individuals remain committed to this “ideal,” that could explain the nonlinear relationships found here.

Other explanations can be derived from the theoretical arguments outlined earlier, particularly for the step change - varying slope and quadratic change models, since these two forms were preferred for all but one nonlinear preference. In the former, the influence of religiosity was allowed to shift upon reaching “high” values, with a new slope beyond that point; in the latter, the influence of religiosity was allowed to increase as religiosity increased.

Support for the step change - varying slope form is in line with the earlier theorizing about embeddedness within religious plausibility structures (Berger 1967; Regnerus 2007) and reference groups (Bock, Beeghley, and Mixon 1983; Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991) that could disproportionally benefit youth who are highly religious. In other words, the unique effect of “high” religiosity could signal entry into a religious network or reference group, upon which religion becomes more salient and additional increases in religiosity are associated with higher costs and rewards of norm adherence (Wimberley 1989). Youth who are nominally religious may thus miss out on many of the influences corresponding to regular participation in a religious community, including reference groups that communicate cautionary or avoidant messages about sexual activity (Bock, Beeghley, and Mixon 1983; Cochran et al. 2004; Cochran and Beeghley 1991), similar-aged peer groups that focus on maintaining sexual purity in the face of temptations (Diefendorf 2015; Irby 2013, 2014a), and parental or adult figures that provide moral expectations, supervision, network closure, and can also schedule de-sexualized activities (Regnerus 2007; Smith 2003a, 2003c, 2003b). As argued earlier, this is not necessarily a function of conservative affiliation alone, though, since highly religious adolescents may still be driven to avoid sexual behaviors by their religious salience, even in the face of incurring costs or forgoing rewards from their social context or other group memberships.

Support for the quadratic change models, which indicate an increasingly large and inhibitory influence of religiosity on sexual behaviors (generally after a moderate amount of religiosity is obtained), perhaps aligns best with the individual-level arguments posited earlier. Avoiding sexual behaviors for religious reasons seems to require both familiarity with religious teachings about sex and a prominent religious identity that motivates a drive for cognitive consistency and the avoidance of dissonance. Given that religious knowledge is generally low during adolescence (Smith and Denton 2005), that dissonance does not result from irrelevant cognitions (Festinger 1957), and that explicitly religious motivations for abstinence are also rare (Abma and Martinez 2017; Regnerus 2007), it seems plausible that a religious identity is not atop of most adolescents’ salience hierarchies nor should be expected to motivate sexual behaviors (Stryker 1968; Wimberley 1989). Thus, it may take at least a moderate amount of religiosity before adolescents learn their religious teachings, internalize moral directives (Smith 2003b), strive for internal consistency, and apply their beliefs across contexts involving sexual decisions.

Limitations and Conclusions

Despite the contributions of this study to understanding the relationships between religion and sex during adolescence, there are several limitations worth noting. First, the mechanisms driving these functional form differences remain unclear. Even after controlling for a large number of factors, the best functional forms were those that allowed the most religious youth to be distinct from their peers on the outcomes examined here. However, these analyses do not exhaust the analytical possibilities that may be driving these preferences, so exploring this further will be an important next step for future researchers. Second, these analyses contain relatively few respondents from religious traditions other than Christianity. Accordingly, these findings should not be assumed to hold for adherents of minority religions in the United States, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, or Islam, who may practice their faiths in different ways and may inhabit religious contexts with different norms regarding sexual activity. Third, this study only uses one data set, making it possible that the nonlinear functional forms supported here could be an artifact of a particular sample of adolescents. Ideally, these nonlinear relationships will later be validated across different samples.

Finally, this study only focuses on paired sexual activity and does not incorporate measures of sexual orientation. The choice to focus on three paired sexual behaviors was primarily due to theoretical scope and space limitations, though religiosity during adolescence has also been shown to influence, and be influenced by, private sexual behaviors like pornography use (Perry and Hayward 2017; Rasmussen and Bierman 2016). Private and solitary sexual activity may exhibit different preferences for functional forms, since it is generally more accessible than paired sexual activity and does not require the same boundary negotiation process that takes place between two partners. Ideally, these analyses would also incorporate sexual orientation and same-sex behaviors into the design, but the NSYR does not have available measures for these. Data from the National Survey of Family Growth show that between three and seven percent of adolescents identify as either homosexual or bisexual, and four to eleven percent report having had same-sex relations (Regnerus 2007). Given the relative lack of research on how religion operates in the sexual lives of LGBT youth (Burdette, Hill, and Myers 2015) and the potential discrimination or stigmatization of these identities from religious organizations (Burdette, Hill, and Myers 2015; Irby 2014b), such inclusions would make these analyses stronger.

In conclusion, this study finds evidence for nonlinearities in the functional form of the relationships between religiosity and sexual behaviors during adolescence. Specifically, highly religious adolescents appear to be distinctively influenced by religion compared to their less religious peers. While this is an important step forward in understanding a well-documented relationship, it also has implications for the sociology of religion more generally. For example, future researchers may benefit from analyzing functional forms of the relationships between religiosity and outcomes not considered here (e.g., marriage, health, criminal behavior). While continuous measures of religiosity are parsimonious and surely acceptable across a range of relationships, it is good practice to test for alternatives, because failure to correctly specify the functional forms of relationships between explanatory variables and outcomes may lead to biased estimators (Wooldridge 2009). There are numerous ways to test for such alternatives (Sauerbrei, Royston, and Binder 2007; Wooldridge 2009), but such explorations should be theoretically informed. The preferred functional forms from this paper may be a good place to start, but the possibilities are myriad. Continuing these investigations has the potential to expand our theoretical and empirical understanding of how religion most impacts individuals today.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to thank Roger Finke for his guidance and encouragement at the early stages of this paper. The author would also like to thank Lisa Pearce, S. Philip Morgan, Michael Shanahan, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions throughout the development of this paper. This research received support from the Population Research Training grant (T32 HD007168) and the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2C HD050924) awarded to the Carolina Population Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The National Study of Youth and Religion, http://youthandreligion.nd.edu/, whose data were used by permission here, was generously funded by Lilly Endowment Inc., under the direction of Christian Smith, of the Department of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame and Lisa Pearce, of the Department of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- Abma Joyce C., and Martinez Gladys M.. 2017. “Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use Among Teenagers in the United States, 2011–2015” 104 National Health Statistics Reports. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk Amy. 2009. “Socialization and Selection in the Link between Friends’ Religiosity and the Transition to Sexual Intercourse.” Sociology of Religion 70 (1): 5–27. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srp010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk Amy, and Felson Jacob. 2006. “Friends’ Religiosity and First Sex.” Social Science Research 35 (4): 924–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman Nancy T. 2013. Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes: Finding Religion in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson Vern L., Putney Norella M., and Harris Susan C.. 2013. Families and Faith: How Religion Is Passed Down across Generations. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Peter L. 1967. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Bock E. Wilbur, Leonard Beeghley, and Mixon Anthony J.. 1983. “Religion, Socioeconomic Status, and Sexual Morality: An Application of Reference Group Theory.” The Sociological Quarterly 24 (4): 545–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle Kathleen A. 2008. Hooking Up: Sex, Dating, and Relationships on Campus. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen Kenneth A., Biemer Paul P., Karr Alan F., Tueller Stephen, and Berzofsky Marcus E.. 2016. “Are Survey Weights Needed? A Review of Diagnostic Tests in Regression Analysis.” Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 3 (1): 375–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-statistics-011516-012958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette Amy M., Hill Terrence D., and Myers Kyl. 2015. “Understanding Religious Variations in Sexuality and Sexual Health” In Handbook of the Sociology of Sexualities, edited by DeLamater John and Plante Rebecca F., 349–70. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17341-2_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke Kelsy, and Hudec Amy M.. 2015. “Sexual Encounters and Manhood Acts: Evangelicals, Latter-Day Saints, and Religious Masculinities.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 54 (2): 330–44. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves Mark. 1994. “Secularization as Declining Religious Authority.” Social Forces 72 (3): 749–74. doi: 10.2307/2579779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves Mark. 2010. “Rain Dances in the Dry Season: Overcoming the Religious Congruence Fallacy.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49 (1): 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01489.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran John K., and Beeghley Leonard. 1991. “The Influence of Religion on Attitudes toward Nonmarital Sexuality: A Preliminary Assessment of Reference Group Theory.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30 (1): 45–62. doi: 10.2307/1387148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran John K., Chamlin Mitchell B., Beeghley Leonard, and Fenwick Melissa. 2004. “Religion, Religiosity, and Nonmarital Sexual Conduct: An Application of Reference Group Theory.” Sociological Inquiry 74 (1): 70–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2004.00081.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorf Sarah. 2015. “After the Wedding Night: Sexual Abstinence and Masculinities over the Life Course.” Gender & Society 29 (5): 647–69. doi: 10.1177/0891243215591597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuMouchel William H., and Duncan Greg J.. 1983. “Using Sample Survey Weights in Multiple Regression Analyses of Stratified Samples.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 78 (383): 535–43. doi: 10.2307/2288115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dziak John J., Coffman Donna L., Lanza Stephanie T., and Li Runze. 2012. “Sensitivity and Specificity of Information Criteria” 12–119. Technical Report Series. State College, PA: The Pennsylvania State University; https://methodology.psu.edu/media/techreports/12-119.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell Penny. 2012. “A Cultural Sociology of Religion: New Directions.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 247–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner Christine J. 2011. Making Chastity Sexy: The Rhetoric of Evangelical Abstinence Campaigns. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Peter C., and Pargament Kenneth I.. 2017. “Measurement Tools and Issues in the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality” In Faithful Measures: New Methods in the Measurement of Religion, edited by Finke Roger and Bader Christopher D., 48–77. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irby Courtney A. 2013. “‘We Didn’t Call It Dating’: The Disrupted Landscape of Relationship Advice for Evangelical Protestant Youth.” Critical Research on Religion 1 (2): 177–94. doi: 10.1177/2050303213490041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irby Courtney A. 2014a. “Dating in Light of Christ: Young Evangelicals Negotiating Gender in the Context of Religious and Secular American Culture.” Sociology of Religion 75 (2): 260–83. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srt062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irby Courtney A. 2014b. “Moving Beyond Agency: A Review of Gender and Intimate Relationships in Conservative Religions.” Sociology Compass 8 (11): 1269–80. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. Scott. 1997. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Vol. 7 10 vols. Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Longest Kyle C., and Uecker Jeremy E.. 2018. “Moral Communities and Sex: The Religious Influence on Young Adult Sexual Behavior and Regret.” Sociological Perspectives 61 (3): 361–82. doi: 10.1177/0731121417730015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove Jennifer S., Elizabeth Terry-Humen Erum N. Ikramullah, and Moore Kristin A.. 2006. “The Role of Parent Religiosity in Teens’ Transitions to Sex and Contraception.” Journal of Adolescent Health 39 (4): 578–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montez Jennifer K., Hummer Robert A., and Hayward Mark D.. 2012. “Educational Attainment and Adult Mortality in the United States: A Systematic Analysis of Functional Form.” Demography 49 (1): 315–36. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Study of Youth and Religion. 2008. “Methodological Design and Procedures for the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR) Longitudinal Telephone Survey (Waves 1, 2, & 3).” Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame; http://youthandreligion.nd.edu/assets/102496/master_just_methods_11_12_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce Lisa D., and Denton Melinda L.. 2011. A Faith of Their Own: Stability and Change in the Religiosity of America’s Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce Lisa D., Hayward George M., and Pearlman Jessica A.. 2017. “Measuring Five Dimensions of Religiosity Across Adolescence.” Review of Religious Research 59 (3): 367–93. doi: 10.1007/s13644-017-0291-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen Willy. 2014. “Forbidden Fruit? A Longitudinal Study of Christianity, Sex, and Marriage.” The Journal of Sex Research 51 (5): 542–50. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.753983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry Samuel L., and Hayward George M.. 2017. “Seeing Is (Not) Believing: How Viewing Pornography Shapes the Religious Lives of Young Americans.” Social Forces 95 (4): 1757–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen Kyler, and Bierman Alex. 2016. “How Does Religious Attendance Shape Trajectories of Pornography Use Across Adolescence?” Journal of Adolescence 49: 191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus Mark D. 2007. Forbidden Fruit: Sex and Religion in the Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus Mark D., and Elder Glen H.. 2003. “Religion and Vulnerability among Low-Risk Adolescents.” Social Science Research 32 (4): 633–58. doi: 10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00027-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky Sharon S., Wilcox Brian L., Wright Margaret L., and Randall Brandy A.. 2004. “The Impact of Religiosity on Adolescent Sexual Behavior: A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Adolescent Research 19 (6): 677–97. doi: 10.1177/0743558403260019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles Steven. 2015. “Patriarchy, Power, and Pay: The Transformation of American Families, 1800–2015.” Demography 52 (6): 1797–1823. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0440-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbrei Willi, Royston Patrick, and Binder Harald. 2007. “Selection of Important Variables and Determination of Functional Form for Continuous Predictors in Multivariable Model Building.” Statistics in Medicine 26 (30): 5512–28. doi: 10.1002/sim.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. 2003a. “Religious Participation and Network Closure among American Adolescents.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42 (2): 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. 2003b. “Theorizing Religious Effects among American Adolescents.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42 (1): 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Christian. 2003c. “Religious Participation and Parental Moral Expectations and Supervision of American Youth.” Review of Religious Research 44 (4): 414–24. doi: 10.2307/3512218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]