Abstract

Neuroinflammation contributes to hypoxic-ischemic (HI) brain injury. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins (IAIPs) have important immunomodulatory properties. Human (h) plasma-derived IAIPs reduce brain injury and improve neurobehavioral outcomes after HI. However, the effects of hIAIPs on neuroinflammatory biomarkers after HI have not been examined. We determined whether hIAIPs attenuated HI-related neuroinflammation. Postnatal day-7 rats exposed to sham-placebo, or right carotid ligation and 8% oxygen for 90 minutes with placebo, and hIAIP treatment were studied. hIAIPs (30 mg/kg) or PL was injected intraperitoneally immediately, 24, and 48 hours after HI. Rat complete blood counts and sex were determined. Brain tissue and peripheral blood were prepared for analysis 72 hours after HI. The effects of hIAIPs on HI-induced neuroinflammation were quantified by image analysis of positively stained astrocytic (glial fibrillary acid protein [GFAP]), microglial (ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule-1 [Iba-1]), neutrophilic (myeloperoxidase [MPO]), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9), and MMP9-MPO cellular markers in brain regions. hIAIPs reduced quantities of cortical GFAP, hippocampal Iba-1-positive microglia, corpus callosum MPO, and cortical MMP9-MPO cells and the percent of neutrophils in peripheral blood after HI in male, but not female rats. hIAIPs modulate neuroinflammatory biomarkers in the neonatal brain after HI and may exhibit sex-related differential effects.

Keywords: Astrogliosis, Hypoxic ischemia, Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins, Matrix metalloproteinase-9, Microglia, Neuroprotection, Neutrophils

INTRODUCTION

Hypoxic-ischemic (HI) brain injury results from a reduced blood flow and oxygen supply to the brain (1). HI can predispose neonates to neurodevelopmental disabilities including epilepsy, cerebral palsy, death, and long-term intellectual deficits (1–3). Therapeutic hypothermia is the only strategy approved to treat hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in full-term infants. However, this treatment is only partially protective, has a narrow therapeutic window after birth, and cannot be used to treat infants born before 36 weeks of gestation (4–6). Therefore, the development of adjunctive and alternative therapeutic agents to treat infants with neonatal HI is essential.

Neuroinflammation is a major contributor to the evolution of HI brain injury in the fetus and neonate (7–9). Neuroinflammatory responses to HI include release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and cytotoxic factors by glial and systemic immune cells, which can exacerbate neuronal injury (10–12).

Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins (IAIPs) are a family of plasma-associated serine protease inhibitors found in the systemic circulation with immunomodulatory anti-inflammatory properties (13). IAIPs in plasma are comprised of Inter-alpha inhibitor consisting of 2 heavy chains and 1 light chain, and pre-alpha inhibitor, consisting of 1 heavy chain and 1 light chain (13). The light chain, bikunin, contains 2 Kunitz-type inhibitor domains. The heavy chains synergize with the activity of the light chain to stabilize and construct extracellular matrix tissue (14–16). Previous work has suggested that IAIPs exert important systemic anti-inflammatory properties (17) because they inhibit protease activity and systemic complement activation, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations and, improve survival (17–19).

Studies have demonstrated that bikunin, also known as urinary trypsin inhibitor or ulinastatin, has important neuroprotective properties after exposure to ischemia-reperfusion in adult rodents (20–22). Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that treatment with the complete plasma derived IAIPs is neuroprotective, decreases neuronal cellular death, improves neurobehavioral outcomes, reduces auditory processing deficits, improves working and reference memory, and promotes hippocampal neuroplasticity in male rats after exposure to neonatal HI (23–26). In addition, previous work suggests that the bikunin-related neuroprotective effects are mediated by anti-inflammatory effects after ischemic reperfusion-related brain injury and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in adult rodents (27–29).

Three of the major contributors to neuroinflammatory injury include reactive gliosis, microglia activation within the brain parenchyma, and infiltration of systemic circulating leukocytes into brain tissue (30–35). Evidence likewise suggests that systemic components of the innate immune system such as granulocytes could also influence outcomes of ischemia-related brain injury (36).

Astrocytes and microglia participate in processes associated with neuroinflammation including migration, proliferation, and release of factors such as cytokines and proteases that facilitate repair and replace injured tissue (37–39). Astrocyte activation is a hallmark of HI-related brain pathology (39, 40), and microglia are similarly activated after acute injury, release reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines, and are implicated in neuronal injury (41–43).

Infiltration of circulating polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells into the brain parenchyma contributes to injury after HI and stroke (33, 35, 36, 44). Neutrophils may injure the cerebrovasculature by releasing factors such as matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) (45, 46). Circulating leukocytes including neutrophils and lymphocytes likely influence neurological outcomes after neonatal HI (36, 47–50). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of information regarding the roles of these cells in brain injury in neonates.

The neuroprotective effects of IAIPs in neonatal rats after HI (23–26) could be mediated in part by immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory effects similar to those reported for bikunin in adult rodents (27–29). Therefore, it is likely that the intact plasma-derived IAIPs could similarly inhibit key cellular inflammatory regulators after HI in neonates.

Given the considerations summarized above, the objective of the current study was to determine the effects of the human plasma-derived IAIPs (hIAIPs) on biomarkers of neuroinflammation in the neonatal brain after exposure to HI. Therefore, changes in microglia, astrocyte, polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells, and MMP9 expression in the brain parenchyma and systemic complete blood counts (CBCs) were examined in neonatal rats with and without exposure to hIAIPs. Moreover, changes were examined in male and female neonatal rats because of the known sex-related differences in neurobiological and behavioral outcomes after HI (51–53).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and after approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island.

Animal Preparation, Surgical, and Experimental Procedures

Pregnant Wistar dams were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) on embryonic day 15 or 16. The pregnant dams were housed in a temperature controlled 12-hour light/dark cycled facility with continuous access to food and water at the Animal Care Facility at Brown University. The date upon which the pups delivered was designated as postnatal day 0 (P0). The Rice-Vannucci method was used to induce HI in the neonatal rats (54). At P7, the rat pups were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 experimental groups: Nonischemic sham-control (Sham-PL); right common carotid artery ligation and hypoxia-exposed (8% oxygen for 90 minutes) with placebo injections (HI-PL); or right common carotid artery ligation and hypoxia-exposed with IAIP treatment (HI-IAIP). The sex and weight of each subject were recorded.

Surgery was performed after anesthetic induction with 4% isoflurane in 96% oxygen and maintained with 1%–2% isoflurane in 98%–99% oxygen using a Vapomatic Anesthetic Vaporizer (Bickford Anesthesia Equipment, New York, NY). Each pup was placed in a supine position on a heated surgical platform to maintain body temperature at 36°C during surgery. A 1–2-mm incision was made right of the midline above the suprasternal notch. The right common carotid artery was double ligated with 5-0 silk sutures in the HI-PL and HI-IAIP groups. The incision was closed and disinfected with betadine and 70% ethanol. The animals were marked with ink tail injections for identification (Neo-9, Animal Identification & Marking Systems, Inc., Hornell, NY) and then returned to their dams for 1.5–3 hours. The pups were then placed in a temperature controlled hypoxic chamber (Biospherix, Parish, NY) where they were exposed to 8% oxygen for 90 minutes. The rectal temperature of a sentinel rat pup was monitored every 10 minutes and maintained at 36°C throughout the hypoxic exposure. The Sham-PL animals were placed in a separate chamber in room air and exposed to the same surgical procedure except that the right carotid artery was not ligated. The HI-IAIP group received 3 intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of 30 mg/kg of hIAIPs (ProThera Biologics, Inc., Providence, RI) immediately, 24 and 48 hours after completion of the exposure to hypoxia. The pups in the Sham-PL and HI-PL groups were given 3 i.p. injections of equivalent volumes of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) over the same time intervals. The neonatal rats were monitored and weighed before each injection.

The production and purification of IAIPs consisted of extraction of IAIPs from human plasma, purification with monolithic anion-exchange chromatography (CIMmultus, BIA Separation, Villach, Austria), and concentration with a tangential flow filtration system (Labscale; Millipore, Danvers, MA) as previously described (19, 25, 55, 56). We also conducted purity analysis with SDS-PAGE, Western immunoblot, competitive IAIP ELISA and a standard in vitro trypsin inhibition assay. We assessed the biological activity by quantifying IAIP inhibition of hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate trypsin and monitored the decrease in the rate of change in absorbance/minute at a 410-nm wavelength (13).

Seventy-two hours after HI, 90 mg/kg of ketamine and 4 mg/kg xylazine were i.p. injected in order to anesthetize the rat pups. Adequate anesthesia was assessed by a lack of withdrawal to a foot pinch, then 250–300 µl of trunk blood was collected to measure the CBCs, placed in ice, and shipped to Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The brain was then perfused with PBS via a cardiac puncture in preparation for the immunohistochemical analyses. Thereafter, the brain was carefully removed from the skull, weighed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours and stored in 30% sucrose in phosphate buffer (0.1 M) at 4°C. Paraffin embedded brain tissue was sectioned in slices of 10 μm thickness. Coronal brain sections containing the dorsal hippocampus (bregma –3.12 ± 0.6 mm) were used to standardize the sections for immunohistochemical analyses (57).

Immunohistochemical Staining and Quantification

Slides were deparaffinized and hydrated in several changes of xylene and graded ethanol and rinsed in distilled water prior to antigen retrieval. Antigen retrieval was performed with a sodium citrate buffer solution (10 mM, pH 6.0) at 120°C in an autoclave for 10 minutes or 15 minutes in a microwave-heated pressure cooker. The slides were then blocked with either a prepared blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin, 5% normal goat serum, TBST with 0.3 M glycine) or Superblock T20, TBS blocking buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Two hundred to 300 µl of primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer was placed on each slide and incubated at 4°C on a shaker overnight. The following primary antibodies were used to identify the individual cell types: Primary mouse anti-Iba1 (1:200, Dako, Carpentaria, CA) was used to detect microglia, rabbit antimyeloperoxidase ([MPO], 1:200, Dako) to detect MPO-positive cells, which were also costained for MMP9-positive cells with mouse antiMMP9 (1:250, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) with rabbit antiGFAP (1:1500, Dako) to detect astrocytes. The secondary antibodies included Alexa Fluor 555 labeled antimouse IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and/or Alexa Fluor 488 labeled antirabbit IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen) were then applied and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. The slides were dried and mounted with 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole ([DAPI], Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) for nuclear staining. Stained slides were protected from UV exposure and stored at 4°C until analysis.

The stained slides were visualized with a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 imaging system microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Jena, Germany). Microglia, MPO-positive cell, and MMP9-positive cell quantification was performed on the Stereo Investigator 10.0 fractionator probe software (Fractionator probe, Stereo Investigator, MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT) according to previously described methods (25). The automated stage fractionator probe paired with the Stereo Investigator was stepped through the counting frames to quantify positive cells in the entire hemisphere (total hemisphere) and cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and corpus callosum ipsilateral to HI. Image analysis for the GFAP slides was performed with ImageJ2 (58). Images for GFAP analysis, which were obtained from randomly sampled locations within each target brain area, were used for subsequent analysis. Positive GFAP staining was defined through intensity thresholding and results were expressed as a ratio of positively stained GFAP area to total area within each image. The average percent of the area in pixels (gray scale) in each image was calculated for all sampled images in a given brain region. The quantity of microglia and MPO-positive cells were determined as the number of positively stained cells divided by the area in mm2 of the specific brain region analyzed for each slide. MPO positively stained cells were considered as indicators of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells because we did not distinguish between these specific cell types with specific antibodies (44).

The Iba-1-positive microglial cells were also qualitatively characterized morphologically to evaluate the microglial cellular morphology without knowledge of the study groups. Microglia were characterized as exhibiting either an amoeboid morphology containing a large soma with little to no visible rami or processes extending from the soma, or as possessing a ramified morphology containing a relatively smaller soma and numerous rami or processes extending from the soma as previously reported (59–62). All immunohistochemical quantification was performed on coded slides without knowledge of the study group designation.

Complete Blood Counts

CBC analyses were determined on 250–300 µl of blood containing ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid ([EDTA], BD Microtainer Tube with K2EDTA Additive) and sent on ice to Charles River Laboratories Clinical Pathology Services (Shrewsbury, MA). The CBC samples were analyzed within 24 hours of arrival on an Advia 120 Hematology Analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). White blood cells, red blood cells, platelets, hemoglobin and hematocrit were quantified. The pathologists at Charles River reviewed the rat blood smears to verify the counts of the individual cell types. The CBC analyses were also performed without knowledge of the experimental groups at the Charles River Laboratory.

Statistical Analyses

All results are expressed as mean ± SEM and a significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. StatSoft STATISTICA 10 was used for the analysis of the microglial, neutrophil and MMP9 quantification, JMP Pro 13 was used for astrocyte analysis, and SigmaPlot was used for analysis of CBC results. Animal grouping was revealed after completion of all quantification. The Wilks-Shapiro test was used to determine whether the data exhibited a normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance was used for normally distributed samples and the Kruskal-Wallis test for nonnormally distributed samples. Post hoc analyses were completed with either Fisher-LSD or Dunn post hoc tests for normal and nonnormal distributed data, respectively, to determine specific differences between groups.

RESULTS

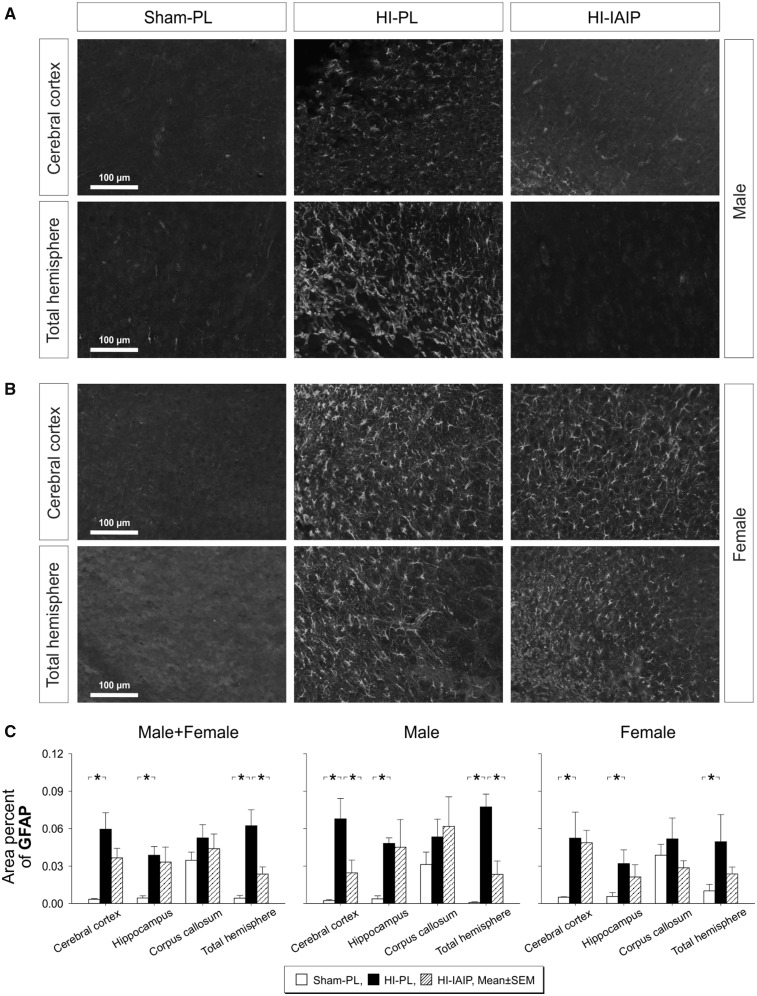

Exogenous IAIP Administration Reduces the Amount of Immunohistochemically Stained Astrocytic Area in the Ipsilateral HI Cerebral Cortex and Total Hemisphere

The immunohistochemical images (Fig. 1A, B) represent randomly selected areas of the total hemisphere and cerebral cortex that had been designated for quantification. Immunohistochemical staining of GFAP (gray scale, white stained areas) appeared more extensive in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere of the HI-PL compared with the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males (Fig. 1A, white areas). Numerous astrocytes were observed with elongated processes and relatively large somas in the HI-PL compared with similar images in the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP groups (63). GFAP staining in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere appeared more extensive in the HI-PL and HI-IAIP compared with the Sham-PL females (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Astrocyte GFAP expression in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups after treatment with IAIPs or placebo. Representative immunohistochemical images (8-bit grayscale) of GFAP-stained cells (white) in the cerebral cortex and a random section of the overall hemispheres ipsilateral to HI of Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP (A) male and (B) female rats. Scale bar: 100 µm. (C) Area percent GFAP plotted on the Y-axis for the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and total hemisphere on the X-axis in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel male and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 7, female: n = 5; HI = PL: male: n = 6, female: n = 7; HI-IAIP: male: n = 7, female: n = 7. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

The percent of the GFAP-stained area quantified by intensity thresholding and expressed as the ratio of the GFAP-stained area to the total area was higher (Fig. 1B, Male + Female, p < 0.05) in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere ipsilateral to the HI injury in the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males plus females. Moreover, the percent of the GFAP-stained area was lower (Fig. 1C, Male + Female, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral total hemisphere of the HI-IAIP than of the HI-PL males plus females. However, differences were not observed in the percent of GFAP-stained area in the corpus callosum (Fig. 1C, Male + Female, p > 0.05) among the groups. The percent of the GFAP-stained area was greater (Fig. 1C, Male, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males. Moreover, the percent of the GFAP-stained area was lower (Fig. 1C, Male, p < 0.05) in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere of the HI-IAIP than in the HI-PL males. The percent of GFAP-stained area was also higher (Fig. 1C, Female, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than Sham-PL females. However, significant differences were not observed (Fig. 1C, Female, p > 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum or total hemisphere between the HI-PL and HI-IAIP females. Examination of the contralateral nonischemic hypoxic cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere did not identify differences (p > 0.05) in the quantity of astrogliosis in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, or HI-IAIP males plus females. Therefore, exogenous IAIP administration appears to attenuate increases in the percent of GFAP-stained area in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere ipsilateral to HI primarily in male neonatal rats after HI.

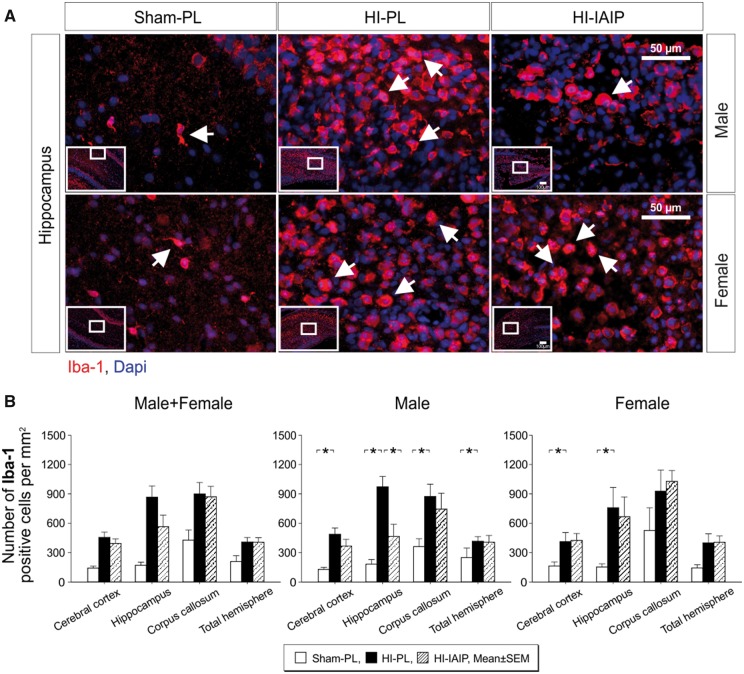

Exogenous IAIPs Administration Reduces the Number of Microglia in the Ipsilateral HI Hippocampus

Figure 2A contains representative images of the hippocampus ipsilateral to the HI brain injury of Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males (top panel) and females (bottom panel). Microglia were stained for Iba-1 (Fig. 2A, red fluorescence) and cellular nuclei counterstained with the blue fluorescent DAPI. The white arrows in Figure 2A designate Iba-1-positively stained cells, and the insets on each image identify the area of the hippocampus from which the image was obtained. The microglial density in the hippocampus appeared higher in specific hippocampal regions including in the CA-1 region and areas adjacent to the corpus callosum (data not shown). The microglial density appeared greater in the hippocampus of the HI-PL than of the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males and in the hippocampus of the HI-PL and HI-IAIP than Sham-PL females. The effect of HI-related injury to the hippocampus did not appear uniform because the microglial density was not necessarily consistent among the different hippocampal regions within each animal with some hippocampal areas remaining largely unaffected (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Quantity of microglia in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups after treatment with IAIPs or placebo (PL). (A) Representative immunohistochemical images of Iba-1-stained cells (red) in the hippocampi of Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP male and female rats. DAPI (blue) is a counterstain. The white arrows indicate Iba-1-positive microglial cells. Scale bar: 50 µm. (B) The number of Iba-1-positive cells divided by the area of the brain region (mm2) plotted on the Y-axis for the cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and overall total hemisphere on X-axis in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel male and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 11, female: n = 7; HI = PL: male: n = 12, female: n = 8; HI-IAIP: male: n = 10, female: n = 9. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Significant differences were not identified (Fig. 2B, Male + Female, p > 0.05) in the number of Iba-1-positive cells per mm2 in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, or total hemisphere between the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females. However, the number of positive Iba-1 cells was higher (Male, p < 0.01) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere of the HI-PL compared with the Sham-PL males, and lower (Fig. 2B, Male, p < 0.05) in the hippocampus of the HI-IAIP than the HI-PL males. The number of positive Iba-1 cells was also higher (Fig. 1B, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex and hippocampus of HI-PL than the Sham-PL females, but did not differ (Fig. 1B, Female, p > 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum or total hemisphere between the HI-PL and HI-IAIP females. Analysis of the contralateral nonischemic hypoxic cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere did not identify differences (p > 0.05) in the number of Iba-1-positive cells in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, or HI-IAIP males plus females. Therefore, systemic administration of IAIPs after HI appears to reduce the quantity of microglia in the hippocampus of male, but not female neonatal rats.

Examination of the microglia in the HI-PL and HI-IAIP groups (Fig. 2A) suggested that they exhibited amoeboid morphology with a large rounded soma without extended rami or processes. The “deramified” amoeboid morphology is characteristic of upregulated microglia (34, 60, 64). Table 1 summarizes the Iba-1 amoeboid-positive microglia as a ratio to the total number of Iba-1-positive microglia in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females, males, and females. The ratio of Iba-1 amoeboid-positive microglia to the total number of Iba-1-positive microglia was higher (Male + Female, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males plus females. However, differences were not observed (Male + Female, p > 0.05) in the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, hippocampus or total hemisphere between HI-IAIP and HI-PL males plus females. The Iba-1 amoeboid-positive microglia as a ratio to total number of Iba-1 microglia was also higher (Male, p < 0.01) in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males. In addition, the proportion of the amoeboid-positive Iba-1 microglia was significantly lower (Male, p < 0.05) in the cerebral cortex of the HI-IAIP than HI-PL males. The proportion of the amoeboid Iba-1 microglia was higher (Females, p < 0.05) in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than the Sham-PL females. However, differences were not observed in the proportion of amoeboid Iba-1 microglia in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus or total hemisphere between the HI-IAIP and HI-PL females.

TABLE 1.

Iba1 Amoeboid-Positive Microglia as a Ratio to the Total Number of Iba1-Positive Microglia in the Ipsilateral Cerebral Cortex, Hippocampus and Total Hemisphere of the Males + Females, Males, and Females by Study Group

| Sham-PL | HI-PL | HI-IAIP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male + female | |||

| Cerebral cortex | 0.62 ± 0.07 | 0.91 ± 0.11** | 0.85 ± 0.13 |

| Hippocampus | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.84 ± 0.23** | 0.82 ± 0.17 |

| Total hemisphere | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.14* | 0.84 ± 0.12 |

| Male | |||

| Cerebral cortex | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.02** | 0.83 ± 0.05# |

| Hippocampus | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.03** | 0.85 ± 0.05 |

| Total hemisphere | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.02** | 0.85 ± 0.05 |

| Female | |||

| Cerebral cortex | 0.47 ± 0.13 | 0.85 ± 0.05* | 0.87 ± 0.03 |

| Hippocampus | 0.61 ± 0.12 | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 0.79 ± 0.06 |

| Total hemisphere | 0.36 ± 0.13 | 0.79 ± 0.07* | 0.83 ± 0.02 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

*p < 0.05 or **p < 0.01 compared with Sham group; #p < 0.05 compared with HI-PL.

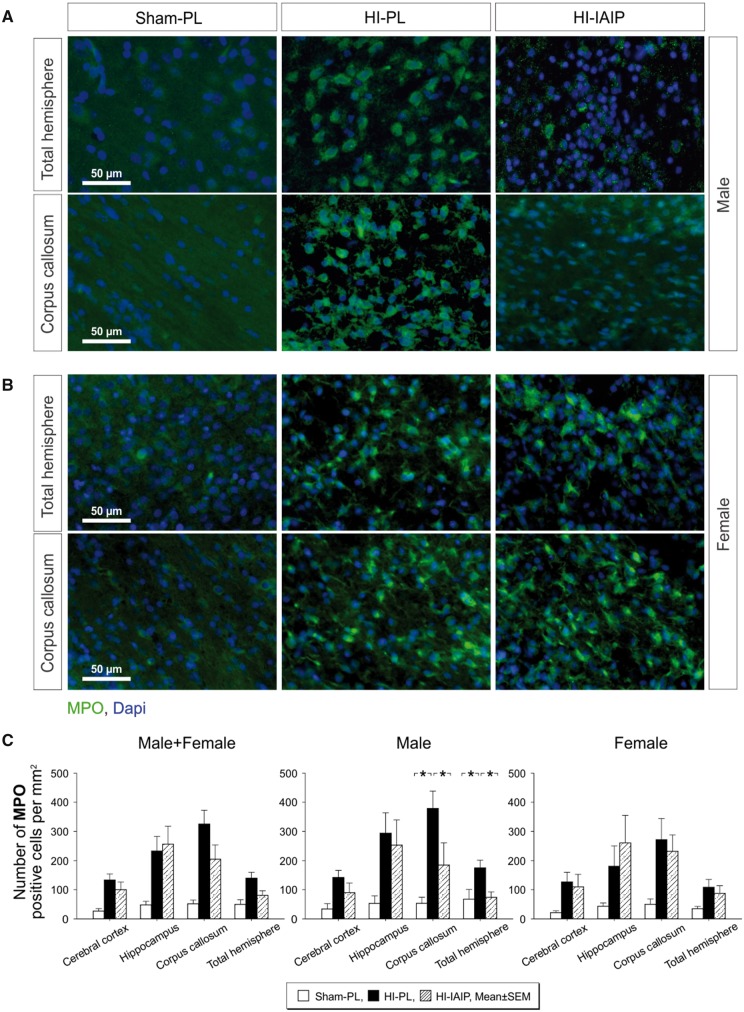

Exogenous IAIPs Attenuate the Quantity of Positively Stained MPO Cells in the Ipsilateral HI Total Hemisphere and Corpus Callosum of Male Neonatal Rats

Figure 3A and B contains representative immunohistochemical images of MPO (green fluorescence) positively stained cells along with the blue fluorescent DAPI profiles to identify the nuclei of cells in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males (Fig. 3A) and females (Fig. 3B). The MPO-positive green fluorescent profiles appeared more abundant in the ipsilateral HI total hemisphere and corpus callosum in the HI-PL than in the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males. The MPO-positive green fluorescent profiles appeared more abundant in the ipsilateral HI total hemisphere and corpus callosum in the HI-PL and HI-IAIP than in the Sham-PL females. Although MPO-positive cells have been traditionally considered polymorphonuclear leukocytes, recent work suggests the MPO can also stain other cell types including monocytes and macrophages (44). We did not identify these specific cell types and, hence, refer to positively stained MPO cells in the brain regions.

FIGURE 3.

Quantity of MPO-positive cells in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups after treatment with IAIPs or placebo. (A) Representative immunohistochemical images of MPO-stained cells (green) in a section of the total hemisphere and corpus callosum of Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP male (A) and female (B) rats. DAPI (blue) is a counterstain. Scale bar: 50 µm. (C) The number of MPO-positive cells divided by the area of the brain quantified (mm2) plotted on the Y-axis for the cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and total hemisphere on the X-axis in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel males and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 5, female: n = 6; HI = PL: male: n = 9, female: n = 8; HI-IAIP: male: n = 9, female: n = 8. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

Significant differences were not identified (Fig. 3C, Male + Female, p > 0.05) in a ratio of the number of infiltrating MPO positively stained cells to the area of the brain region (mm2) in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, or total hemisphere between the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females. However, the number of infiltrating MPO-positive cells was higher (Fig. 3C, Male, p < 0.05) in the ipsilateral HI corpus callosum and total hemisphere of the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males, and lower (Fig. 3C, Male, p < 0.05) in the HI-IAIP than in the HI-PL males. Significant differences were not identified (Fig. 3C, Female, p > 0.05) in the number of infiltrating MPO-positive cells per mm2 in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, or total hemisphere between the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP females. Examination of the contralateral nonischemic hypoxic cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere did not identify differences (p > 0.05) in the number of MPO-positive cells in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, or HI-IAIP males plus females. Consequently, IAIPs appear to reduce the number of MPO-positive infiltrating cells in the corpus callosum and total hemisphere ipsilateral to HI in the male neonatal rats.

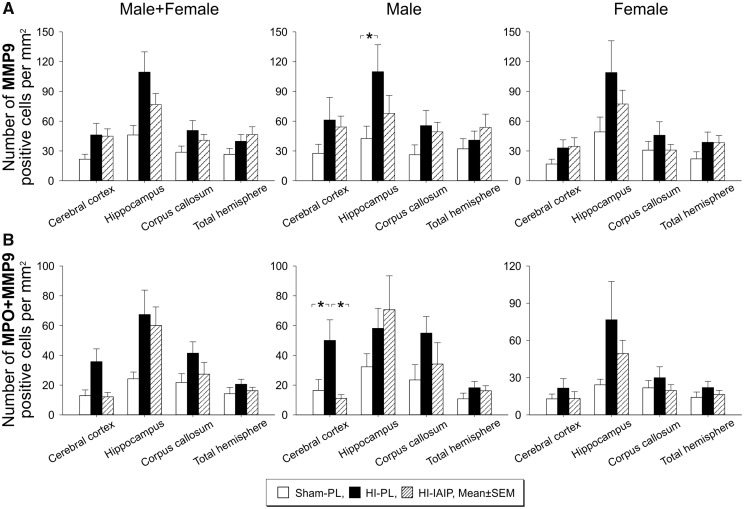

IAIPs Reduce MMP9 Positively Stained Cells in the Ipsilateral HI Cerebral Cortex of Male Neonatal Rats

Significant differences were not identified (Fig. 4A, p > 0.05) in the number of MMP9-positive cells divided by the area (mm2) in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, or total hemisphere between the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females or females. However, the number of MMP9-positive cells per mm2 was significantly higher in the ipsilateral HI hippocampus in the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males (Images not shown, p < 0.05). Analysis of the contralateral nonischemic hypoxic cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere did not identify differences (p > 0.05) in the quantity of MMP9-positive cells per area in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, or HI-IAIP males plus females, males or females.

FIGURE 4.

Quantity of MMP9-positive cells and MMP9-positive MPO cells in Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups after treatment with IAIPs or placebo. (A) The number of MMP9-positive cells divided by the area of the brain region quantified (mm2) plotted on the Y-axis for the cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and total hemisphere on the X-axis for Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP animals. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel males and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 5, female: n = 6; HI = PL: male: n = 9, female: n = 8; HI-IAIP: male: n = 9, female: n = 8. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05. (B) The number of positive cells for MPO+ + MMP9+ staining divided by the area of the brain region quantified (mm2) plotted on the Y-axis for the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum and total hemisphere on the X-axis for the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel males and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 5, female: n = 6; HI = PL: male: n = 9, female: n = 8; HI-IAIP: male: n = 9, female: n = 8. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

We double-stained brain sections for MPO (green fluorescence, images not shown) and MMP9 with antiMMP9 (red fluorescence, images not shown), and costained cellular nuclei with the DAPI blue fluorescent stain. MPO-positive cells that were also positive for MMP9 (MPO+ + MMP9+) were quantified as MPO+ + MMP9+ cells divided by the area (mm2) in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and total hemisphere of the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females, males, and females. Significant differences were not identified (Fig. 4B, Male + Female, Female, p > 0.05) in MPO+ + MMP9+ cells divided by the area (mm2) in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, or total hemisphere between the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females or females. However, the number of MPO+ + MMP9+ positive cells per mm2 was significantly higher in the ipsilateral HI cerebral cortex of the HI-PL than in the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males (Fig 4B, Male, p < 0.05). Analysis of the contralateral nonischemic corpus callosum showed that the average number of MPO+ + MMP9+ cells per area was greater (p < 0.05) in the corpus callosum of the Hypoxic-PL than Sham-PL males plus females. However, differences in the number of MPO+ + MMP9+ cells in the cortex, hippocampus, or total contralateral hemisphere were not observed among the study groups (p < 0.05). Therefore, IAIP treatment after HI appears to be associated with reductions in MMP9 expressing MPO positively stained cells in the cerebral cortex of male neonatal rats, but not females.

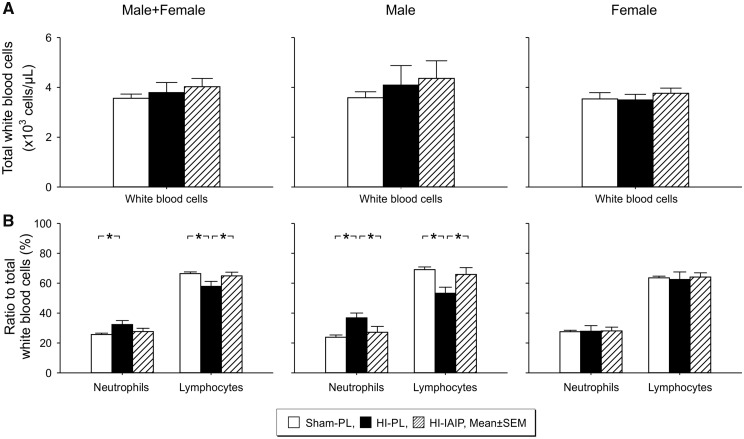

IAIPs Alter the Proportion of Circulating Systemic Neutrophils and Lymphocytes in Neonatal Rats After Exposure to HI

There were no differences (Fig. 5A, p > 0.05) in the total number of white blood cell counts in the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP males plus females, males or females. However, percent of polymorphonuclear neutrophils as a ratio to the total number of white blood cell counts was higher (Fig. 5B, Male + Female, p < 0.05) in the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males plus females. In addition, lymphocytes as a ratio to the white blood counts were lower (Fig. 5A, p < 0.05) in the HI-PL than the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males plus females. The percent of neutrophils was higher and of lymphocytes lower as a ratio to white blood cell counts (Male, p < 0.05) in the HI-PL compared with the Sham-PL and HI-IAIP males. The percent of neutrophils and lymphocytes as a ratio to the total number of white blood cells did not differ (Female, p > 0.05) among the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP females. The hemoglobin and hematocrit values were higher (Table 2, p < 0.05) in the HI-PL than the Sham-PL males. There were no differences in the red blood cell number or platelet counts among the study groups of males or females.

FIGURE 5.

(A) The total number of white blood cells (×103 cells/µL) of the males plus females, males and females for the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups after treatment with IAIPs or placebo. (B) The percent of neutrophils and lymphocytes as ratios to the total number of leukocytes plotted on the Y-axis for the neutrophils and lymphocytes on the X-axis for the Sham-PL, HI-PL, and HI-IAIP groups. The left-hand panel represents the male plus female, middle panel males, and right-hand panel female neonatal rats. Sham-PL: male: n = 11, female: n = 10; HI = PL: male: n = 8, female: n = 8; HI-IAIP: male: n = 8, female: n = 10. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Complete Blood Count Values in the Male and Female Neonatal Rats by Study Group

| Sham-PL | HI-PL | HI-IAIP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||

| Red blood cells × 106 (number/µl) | 3.57 ± 0.06 | 3.76 ± 0.09 | 3.70 ± 0.07 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.20 ± 0.09 | 9.88 ± 0.19** | 9.94 ± 0.22 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 32.1 ± 0.40 | 33.8 ± 0.75* | 33.8 ± 0.57 |

| Platelets × 103 (number/µl) | 592.8 ± 100.2 | 606.9 ± 158.9 | 730.6 ± 101.6 |

| Females | |||

| Red blood cells × 106 (number/µl) | 3.69 ± 0.05 | 3.70 ± 0.12 | 3.66 ± 0.09 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.66 ± 0.14 | 10.0 ± 0.24 | 9.75 ± 0.23 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.1 ± 0.59 | 34.37 ± 0.74 | 34.2 ± 0.74 |

| Platelets × 103 (number/µl) | 656.0 ± 78.0 | 838.0 ± 62.1 | 636.8 ± 89.5 |

Values are mean ± SEM.

*p < 0.05 or ** p < 0.01 compared with Sham group.

DISCUSSION

The overall objective of the current study was to determine whether IAIPs modulate neuroinflammatory biomarkers after HI in neonatal rats. IAIPs attenuate the activity of destructive serine proteases and pro-inflammatory cytokines, increase anti-inflammatory cytokine concentrations, reduce complement activation, and increase survival in systemic inflammatory conditions in neonates and adults (17, 65–67). Consequently, IAIPs potentially serve an essential role as systemic immunomodulatory proteins in many inflammatory disorders (19). Nevertheless, their capacity to modulate neuroinflammation is not well understood. Several recent reports have suggested that the light chain bikunin may exert essential anti-inflammatory effects in the brain (27, 29, 68). However, bikunin has a very short half-life (3–15 minutes) because of its renal clearance (69) when compared with the blood-derived complexes of IAIPs, which have a 6–12 hour half-life in rats (70). The main findings of the current study are that the systemic administration of IAIPs modulates neuroinflammation in neonatal rats after HI in part by attenuating the HI-related upregulation of astrocytes, microglia, infiltrating MPO positively stained cells, and MMP9-positive MPO cells in some select brain regions. Moreover, the neuroimmunomodulatory effects were preferentially observed in the male neonatal rats. In addition, the IAIP-immunomodulatory effects on systemic circulating white cells also differed by sex.

We recently reported that systemic administration of IAIPs has remarkable neuroprotective effects in both male and female neonatal rats (26). They also attenuate neuronal cell death, ameliorate HI related brain weight loss, reduce infarct volumes, improve neuronal plasticity, diminish complex auditory processing abnormalities and improve behavioral outcomes in male neonatal rats after HI brain injury (23–25). Inflammation is an important factor contributing to the evolution of brain injury after neonatal HI (7, 12, 71). Consistent with previous reports (7, 12, 71), we have identified increases in inflammatory cellular markers after exposure of neonatal rats to HI and detected significant reductions in the expression of these biomarkers after treatment with IAIPs in select brain regions of male neonatal rats.

Reactive gliosis is an important component of the neuroinflammatory response to HI injury (31, 32, 37, 39). Astrocytes can disturb the microcellular environment and promote neuronal and glial cell death, inflammation, and glial scar formation that could impair recovery after an ischemic insult (31, 37, 72, 73). Consistent with these findings, we detected astrocytic upregulation in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere (Fig. 1) and have previously reported significant neuronal cell death after HI in neonatal rats (25). Moreover, systemic administration of IAIPs attenuated the immunohistochemically detected increases in GFAP expression in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere of male neonatal rats ipsilateral to the HI injury, which is consistent with a reduction in astrogliosis (Fig. 1C). These findings are important because they suggest that IAIPs could modulate the injury associated with increases in astrocyte expression, which could in turn contribute to the IAIP-related reductions in infarct volumes, neuronal cell death and improved behavioral outcomes after HI that we reported (23–26).

Reactive microgliosis is another important form of neuroinflammation that can predispose to neuronal cell death and exacerbate neuroinflammatory injury after HI (12, 32, 34, 40, 41, 74). Microglia can proliferate, migrate into areas of damage, and become activated in response to HI brain injury (34, 40, 41, 74). Similar to these reports, we observed increases in the number of Iba-1-positive microglia in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, corpus callosum, and total hemisphere of male, and in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of the female neonatal rats after exposure to HI insults (Fig. 2B). Moreover, systemic treatment with exogenous IAIPs after HI appeared to attenuate the microglial response in the hippocampus of the male neonatal rats. These findings suggest that IAIPs have the ability to downregulate these inflammatory biomarkers after HI. The hippocampus is critical for spatial learning and memory. Therefore, reductions in hippocampal microglia numbers in the IAIP-treated male rats after HI could partly account for the beneficial effects of IAIPs on hippocampal neuronal plasticity and the improved outcomes in spatial reference learning, working memory and reference memory (23–25).

The microglia also exhibited differences in the relative proportion possessing an amoeboid morphology (Table 1). Amoeboid microglia represent activated microglia that can release pro-inflammatory cytokines, promote neuronal degeneration, and predispose to scar formation (40, 59). We observed an increase in the proportion of amoeboid microglia in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and total hemisphere of the total group of males plus females and in the males, and in the cerebral cortex and total hemisphere of the females after exposure to HI. However, the amoeboid activated phenotype was only attenuated by IAIP treatment in the cerebral cortex of the males. Therefore, IAIPs potentially reduce the proportion of the amoeboid microglial phenotype, thereby contributing to the neuroprotective effects of IAIPs in the male neonatal rats (23–25). Although the role of microglia in HI-related brain injury remains controversial (34, 41), it appears that treatment with IAIPs after HI modifies the quantity and, potentially, the microglial morphology in the cerebral cortex of male neonatal rats after HI.

There is a plethora of information suggesting that peripheral polymorphonuclear neutrophils are activated, provide an early robust sterile inflammatory response, and can be recruited to enter the brain within hours to days of ischemic brain injury (36). Neutrophils are relatively large leukocytes that normally are not able to enter the brain parenchyma because they cannot cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). However, HI injury-mediated neuroinflammation results in BBB and systemic immune changes that increase the permeability of the BBB to infiltrating neutrophils (75). In this regard, we also detected increases in the number of MPO-positive cells within the corpus callosum and the total hemisphere of the male neonatal rats 72 hours after exposure to HI (Fig. 3). These findings are noteworthy because controversy exists regarding the ability of neonates to mount a sufficient immune response to HI to allow neutrophilic infiltration into the brain (76). Nonetheless, several studies have detected neutrophils in the brain parenchyma of neonatal and fetal subjects after HI-related brain injury (33, 48, 75). Moreover, similar to the findings with the other neuroinflammatory biomarkers, systemic treatment with IAIPs was associated with reductions in the numbers of MPO-positive cells in the corpus callosum and the total hemisphere of the male neonatal rats. The observation that IAIPs reduce MPO-positive cellular infiltration is an important finding because these inflammatory cells accentuate neuronal cell death after HI (75). Furthermore, depletion of neutrophils before HI reduces parenchymal neutrophilic infiltration and is neuroprotective, suggesting that some of the neuroprotective effects of IAIPs could also be related to decreased infiltration of MPO-positive cells into the brain (75). Although the mechanism(s) by which IAIPs reduce infiltration of MPO cells into the brain cannot be determined by our studies, there are several possible explanations for these findings. The first possibility is that treatment with IAIPs reduces the systemic inflammatory response by affecting the number or activation state of the systemic neutrophil population. In this regard, we have recently shown that IAIPs render neutrophils quiescent, facilitate their passage through the microvasculature, decrease endothelial vascular adhesion and reduce the production of reactive oxygen species (77). The second possibility is that IAIPs could have beneficial effects on the BBB after HI, which in turn could restrict the number of MPO-positive cells that enter the brain parenchyma. Although the mechanism(s) by which IAIPs reduce the quantity of MPO-positive cells in the brain remain to be determined, reductions in the number of MPO-positive cells could also contribute to the neuroprotective effects of IAIPs in the neonatal brain after HI (23–26).

MPO-positive neutrophils can colocalize with MMP9 because neutrophils express and release MMP9 after ischemia (45, 78). MMP9 is a pro-inflammatory factor that is known to increase neuronal cell death and lead to impaired outcomes after HI (75). In conjunction with these findings, we identified increases in MPO+ neutrophils that colocalized with MMP9 in the cerebral cortex of the male neonatal rats after HI. Similar to the other neuroinflammatory biomarkers in the brain, treatment with IAIPs reduced the number of MPO+ + MMP9+ cells in the cerebral cortex after HI (Fig. 4B), suggesting that some of the neuroprotection afforded by IAIPs could be, at least in part, related to the regulation of MPO-positive cells along with a decrease in their release of the pro-inflammatory factor MMP9.

As summarized above, IAIPs have important systemic immunomodulatory effects (17, 19, 67, 77). Therefore, we also examined the effects of IAIPs on changes in peripheral white blood cells after HI. Although exposure to HI and treatment with IAIPs did not affect the total white blood counts in the neonatal rats, it was associated with a significant increase in the percent of neutrophils and a decrease in the percent of lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of the neonatal male rats (Fig. 5). Treatment with IAIPs reversed these peripheral blood changes after HI. Similar changes were not observed in the female neonatal rats after HI. Therefore, changes in the systemic leukocyte profile along with the known effects of IAIPs on neutrophils in vitro (77) could also contribute to the diminished amounts of MPO cells in the brain parenchyma after IAIP treatment of neonatal male rats exposed to HI. Although we do not know the significance of the reductions in the percent of circulating lymphocytes after HI, the effects of neutrophils and lymphocytes may counterbalance each other in adult ischemic stroke and neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy with relative increases in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios predicting more compromised outcomes (48, 49, 79). We have shown that systemic treatment with IAIPs affects the peripheral leukocyte response to HI by decreasing the relative proportion of neutrophils and increasing the proportion of lymphocytes. Consequently, the changes in peripheral leukocytes are in the direction that is consistent with improved neurological outcomes (48, 49, 79), providing additional support for the concept that peripheral leukocyte changes represent a component of the mechanisms underlying IAIP-mediated neuroprotection.

The beneficial effects of IAIPs were only observed in the male neonatal rats after exposure to HI. Although we cannot discern the reason for beneficial effects of IAIPs in male and not female neonatal rats, sex-related differences in the effect of HI in neonatal rats have been extensively reported with females generally exhibiting more favorable outcomes (53, 80, 81). Therefore, we speculate that we may need to alter our HI protocol in order to detect the effects of IAIPs on biomarkers of neuroinflammation in the females because females tend to have reduced injury and better functional outcomes compared with male counterparts after HI (51–53, 80). Nonetheless, the reason that treatment with IAIPs reduced biomarkers of neuroinflammation in the males and not the female neonatal rats after HI remains to be determined.

There are several potential limitations to our study and opportunities for future study. The results of our study were based upon a randomly selected brain section for the immunohistochemical analyses. Hence, examination of the inflammatory responses in other brain sections that include areas such as the striatum, basal ganglia and cerebellum would be of interest. In addition, we primarily used immunohistochemical methods to characterize the neuroinflammatory responses of the biomarkers in the brain. Other methodologies such as characterizing functional glial immune cell responses would be important to examine specific molecular response(s) to IAIPs. However, this approach would most likely require in vitro studies, which is beyond the scope of the current in vivo studies. The analyses in the current study were performed after 3 doses of 30 mg/kg IAIP. Higher doses or a larger number of doses of IAIPs potentially could have had greater effects on the neuroinflammatory responses in the brain. Even though we found that IAIPs exert important beneficial effects on neuroinflammatory biomarkers after HI in male neonatal rats and have previously shown that IAIPs have important neuroprotective effects (23–25), the precise mechanism(s) by which IAIPs protect the brain remains to be determined. IAIPs are relatively large molecules that most likely do not readily cross the neonatal BBB under normal circumstances (82). However, it remains possible that, after exposure to HI, IAIPs could potentially cross the BBB to enter the brain parenchyma (83). Therefore, it would be important in future studies to examine the permeability/transport of IAIPs across the BBB after exposure to HI in neonatal rats. Alternatively, the neuroprotection afforded by IAIPs could be based upon beneficial effects on systemic factors.

We conclude that treatment with IAIPs attenuated cortical GFAP expression, microglial proliferation, and MPO and MMP9 positive MPO cell infiltration in select brain regions ipsilateral to HI in male, but not female neonatal rats. IAIPs modulate neuroinflammatory biomarkers in the neonatal brain after exposure to HI and may exhibit sex-related differential effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Sunil Shaw, PhD (COBRE Research Core, Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island) and Virginia Hovanesian, BSc (Core Research Laboratories, Rhode Island Hospital) who provided expert assistance with image acquisition and analyses.

This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: 1R01-HD-057100, 1R21NS095130, 1R21NS096525 and R44 NS084575-02, 1P20GM121298, and P30GM114750.

Y.-P.L. is employed by ProThera Biologics, Inc., and has financial interest in the company. All other authors have no duality or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fatemi A, Wilson MA, Johnston MV.. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in the term infant. Clin Perinatol 2009;36:835–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adhikari S, Rao KS.. Neurodevelopmental outcome of term infants with perinatal asphyxia with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy stage II. Brain Dev 2017;39:107–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chalak LF, Rollins N, Morriss MC, et al. Perinatal acidosis and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in preterm infants of 33 to 35 weeks gestation. J Pediatr 2012;160:388–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jacobs SE, Morley CJ, Inder TE, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for term and near-term newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rumajogee P, Bregman T, Miller SP, et al. Rodent hypoxia-ischemia models for cerebral palsy research: A systematic review. Front Neurol 2016;7:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Klahr AC, Nadeau CA, Colbourne F.. Temperature control in rodent neuroprotection studies: Methods and challenges. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag 2017;7:42–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1985–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen X, Zhang J, Kim B, et al. High-mobility group box-1 translocation and release after hypoxic ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Exp Neurol 2019;311:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang J, Klufas D, Manalo K, et al. HMGB1 translocation after ischemia in the ovine fetal brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016;75:527–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gopagondanahalli KR, Li J, Fahey MC, et al. Preterm hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Front Pediatr 2016;4:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thornton C, Leaw B, Mallard C, et al. Cell death in the developing brain after hypoxia-ischemia. Front Cell Neurosci 2017;11:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li B, Concepcion K, Meng X, et al. Brain-immune interactions in perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Prog Neurobiol 2017;159:50–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim YP, Josic D, Callanan H, et al. Affinity purification and enzymatic cleavage of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins using antibody and elastase immobilized on CIM monolithic disks. J Chromatogr A 2005;1065:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Potempa J, Kwon K, Chawla R, et al. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor. Inhibition spectrum of native and derived forms. J Biol Chem 1989;264:15109–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu L, Zhuo L, Watanabe H, et al. Equivalent involvement of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain isoforms in forming covalent complexes with hyaluronan. Connect Tissue Res 2008;49:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhuo L, Kimata K.. Structure and function of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chains. Connect Tissue Res 2008;49:311–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh K, Zhang LX, Bendelja K, et al. Inter-alpha inhibitor protein administration improves survival from neonatal sepsis in mice. Pediatr Res 2010;68:242–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chaaban H, Shin M, Sirya E, et al. Inter-alpha inhibitor protein level in neonates predicts necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 2010;157:757–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lim YP. ProThera Biologics, Inc.: A novel immunomodulator and biomarker for life-threatening diseases. R I Med J (2013) 2013;96:16–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen HM, Huang HS, Ruan L, et al. Ulinastatin attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Int J Clin Exp Med 2014;7:1483–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li XF, Zhang XJ, Zhang C, et al. Ulinastatin protects brain against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting MMP-9 and alleviating loss of ZO-1 and occludin proteins in mice. Exp Neurol 2018;302:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu M, Shen J, Zou F, et al. Effect of ulinastatin on the permeability of the blood-brain barrier on rats with global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury as assessed by MRI. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;85:412–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Threlkeld SW, Lim YP, La Rue M, et al. Immuno-modulator inter-alpha inhibitor proteins ameliorate complex auditory processing deficits in rats with neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 2017;64:173–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gaudet CM, Lim Y-P, Stonestreet BS, et al. Effects of age, experience and inter-alpha inhibitor proteins on working memory and neuronal plasticity after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Behav Brain Res 2016;302:88–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Threlkeld SW, Gaudet CM, La Rue ME, et al. Effects of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins on neonatal brain injury: Age, task and treatment dependent neurobehavioral outcomes. Exp Neurol 2014;261:424–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X, Nakada S, Donahue JE, et al. Neuroprotective effects of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Exp Neurol 2019;317:244–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feng M, Shu Y, Yang Y, et al. Ulinastatin attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by enhancing anti-inflammatory responses. Neurochem Int 2014;64:64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang XM, Hu JH, Wang LL, et al. Effects of ulinastatin on global ischemia via brain pro-inflammation signal. Transl Neurosci 2016;7:158–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li X, Su L, Zhang X, et al. Ulinastatin downregulates TLR4 and NF-kB expression and protects mouse brains against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neurol Res 2017;39:367–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burda JE, Sofroniew MV.. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 2014;81:229–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang L, Wu Z-B, Zhuge Q, et al. Glial scar formation occurs in the human brain after ischemic stroke. Int J Med Sci 2014;11:344–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li T, Zhang S.. Microgliosis in the injured brain. Neuroscientist 2016;22:165–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jellema RK, Lima Passos V, Zwanenburg A, et al. Cerebral inflammation and mobilization of the peripheral immune system following global hypoxia-ischemia in preterm sheep. J Neuroinflammation 2013;10:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baburamani AA, Supramaniam VG, Hagberg H, et al. Microglia toxicity in preterm brain injury. Reprod Toxicol 2014;48:106–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perez-de-Puig I, Miró-Mur F, Ferrer-Ferrer M, et al. Neutrophil recruitment to the brain in mouse and human ischemic stroke. Acta Neuropathol 2015;129:239–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aronowski J, Roy-O'Reilly MA.. Neutrophils, the felons of the brain. Stroke 2019;50:e42–e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Becerra-Calixto A, Cardona-Gomez GP.. The role of astrocytes in neuroprotection after brain stroke: Potential in cell therapy. Front Mol Neurosci 2017;10:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cho SR, Suh H, Yu JH, et al. Astroglial activation by an enriched environment after transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells enhances angiogenesis after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu Z, Chopp M.. Astrocytes, therapeutic targets for neuroprotection and neurorestoration in ischemic stroke. Prog Neurobiol 2016;144:103–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017;541:481–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brown GC, Vilalta A.. How microglia kill neurons. Brain Res 2015;1628:288–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tang Y, Le W.. Differential roles of M1 and M2 microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol 2016;53:1181–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ju F, Ran Y, Zhu L, et al. Increased BBB permeability enhances activation of microglia and exacerbates loss of dendritic spines after transient global cerebral ischemia. Front Cell Neurosci 2018;12:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weston RM, Jones NM, Jarrott B, et al. Inflammatory cell infiltration after endothelin-1-induced cerebral ischemia: Histochemical and myeloperoxidase correlation with temporal changes in brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:100–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, et al. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type IV collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke 2008;39:1121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, et al. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;289:H558–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morkos AA, Hopper AO, Deming DD, et al. Elevated total peripheral leukocyte count may identify risk for neurological disability in asphyxiated term neonates. J Perinatol 2007;27:365–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Povroznik JM, Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Nanavati T, et al. Absolute lymphocyte and neutrophil counts in neonatal ischemic brain injury. SAGE Open Med 2018;6:2050312117752613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goyal N, Tsivgoulis G, Chang JJ, et al. Admission neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker of outcomes in large vessel occlusion strokes. Stroke 2018;49:1985–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tokgoz S, Kayrak M, Akpinar Z, et al. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:1169–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Charriaut-Marlangue C, Besson V, Baud O.. Sexually dimorphic outcomes after neonatal stroke and hypoxic-ischemia. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Demarest TG, Waite EL, Kristian T, et al. Sex-dependent mitophagy and neuronal death following rat neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neuroscience 2016;335:103–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hill CA, Fitch RH.. Sex differences in mechanisms and outcome of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in rodent models: Implications for sex-specific neuroprotection in clinical neonatal practice. Neurol Res Int 2012;2012:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rice JE, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB.. The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the rat. Ann Neurol 1981;9:131–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Spasova MS, Sadowska GB, Threlkeld SW, et al. Ontogeny of inter-alpha inhibitor proteins in ovine brain and somatic tissues. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2014;239:724–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Opal SM, Lim YP, Cristofaro P, et al. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins: A novel therapeutic strategy for experimental anthrax infection. Shock 2011;35:42–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Paxinos G, Watson C.. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: Compact. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rueden CT, Schindelin J, Hiner MC, et al. ImageJ2: ImageJ for the next generation of scientific image data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017;18:529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Morrison HW, Filosa JA.. A quantitative spatiotemporal analysis of microglia morphology during ischemic stroke and reperfusion. J Neuroinflammation 2013;10:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Torres-Platas SG, Comeau S, Rachalski A, et al. Morphometric characterization of microglial phenotypes in human cerebral cortex. J Neuroinflammation 2014;11:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kaur C, Rathnasamy G, Ling EA.. Biology of microglia in the developing brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017;76:736–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Parakalan R, Jiang B, Nimmi B, et al. Transcriptome analysis of amoeboid and ramified microglia isolated from the corpus callosum of rat brain. BMC Neurosci 2012;13:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu S, Zhu S, Zou Y, et al. Knockdown of IL-1beta improves hypoxia-ischemia brain associated with IL-6 up-regulation in cell and animal models. Mol Neurobiol 2015;51:743–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ransohoff RM. A polarizing question: Do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat Neurosci 2016;19:987–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang S, Lim YP, Zhou M, et al. Administration of human inter-alpha-inhibitors maintains hemodynamic stability and improves survival during sepsis. Crit Care Med 2002;30:617–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Garantziotis S, Hollingsworth JW, Ghanayem RB, et al. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor attenuates complement activation and complement-induced lung injury. J Immunol 2007;179:4187–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chaaban H, Keshari RS, Silasi-Mansat R, et al. Inter-alpha inhibitor protein and its associated glycosaminoglycans protect against histone-induced injury. Blood 2015;125:2286–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jiang W, Yu X, Sun T, et al. ADJunctive Ulinastatin in Sepsis Treatment in China (ADJUST study): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018;19:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sjoberg EM, Blom A, Larsson BS, et al. Plasma clearance of rat bikunin: Evidence for receptor-mediated uptake. Biochem J 1995;308:881–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu R, Cui X, Lim YP, et al. Delayed administration of human inter-alpha inhibitor proteins reduces mortality in sepsis. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1747–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McAdams RM, Juul SE.. The role of cytokines and inflammatory cells in perinatal brain injury. Neurol Res Int 2012;2012:561494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Badaut J, Verbavatz J-M, Freund-Mercier M-J, et al. Presence of aquaporin-4 and muscarinic receptors in astrocytes and ependymal cells in rat brain: A clue to a common function? Neurosci Lett 2000;292:75–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Huang HZ, Wen XH, Liu H.. Sex differences in brain MRI abnormalities and neurodevelopmental outcomes in a rat model of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Int J Neurosci 2016;126:647–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chen Z, Trapp BD.. Microglia and neuroprotection. J Neurochem 2016;136:10–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ziemka-Nalecz M, Jaworska J, Zalewska T.. Insights into the neuroinflammatory responses after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017;76:644–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu F, McCullough LD.. Inflammatory responses in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013;34:1121–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Htwe SS, Wake H, Liu K, et al. Inter-alpha inhibitor proteins maintain neutrophils in a resting state by regulating shape and reducing ROS production. Blood Adv 2018;2:1923–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Castellanos M, Sobrino T, Millán M, et al. Serum cellular fibronectin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 as screening biomarkers for the prediction of parenchymal hematoma after thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke: A multicenter confirmatory study. Stroke 2007;38:1855–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Urra X, Cervera A, Villamor N, et al. Harms and benefits of lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with acute stroke. Neuroscience 2009;158:1174–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hill CA, Threlkeld SW, Fitch RH.. Reprint of “Early testosterone modulated sex differences in behavioral outcome following neonatal hypoxia ischemia in rats.” Int J Dev Neurosci 2011;29:621–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Smith AL, Alexander M, Rosenkrantz TS, et al. Sex differences in behavioral outcome following neonatal hypoxia ischemia: Insights from a clinical meta-analysis and a rodent model of induced hypoxic ischemic brain injury. Exp Neurol 2014;254:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Stonestreet BS, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, et al. Ontogeny of blood-brain barrier function in ovine fetuses, lambs, and adults. Am J Physiol 1996;271:R1594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ek CJ, D'Angelo B, Baburamani AA, et al. Brain barrier properties and cerebral blood flow in neonatal mice exposed to cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015;35:818–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]