Abstract

The wavelength-dependent complex linear polarizability of a dye is a crucial input for the modeling of the optical properties of dye-containing systems. We here propose and discuss methods to obtain an accurate polarizability model by combining absorption spectrum measurements, Kramers–Kronig (KK) tranformations, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We focus, in particular, on the real part of the polarizability and its link with static polarizability. In addition, we introduce simple KK-consistent analytic functions based on the theory of critical points as a much more accurate approach to model dye polarizabilities compared with existing models based on Lorentz oscillators. Accurate polarizability models based on critical points and DFT calculations of the static polarizability are derived for five commonly used dyes: Rhodamine 6G, Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Nile Blue A, and Methylene Blue. Finally, we demonstrate explicitly, using examples of Mie Theory calculations of nanoparticle–dye interactions, how an inaccurate polarizability model can result in fundamentally different predictions, further emphasizing the importance of accurate models, such as the one proposed here.

1. Introduction

The optical properties of dye molecules are routinely exploited in a wide variety of contexts including the following: as gain media in dye lasers,1 as fluorescent tags in many biological sensing and imaging techniques,2,3 as reporters in surface-enhanced spectroscopies4,5 or spectroelectrochemistry,6 and as catalysts for photoredox chemistry.7 One of their central characteristics is their absorption spectrum, which can be easily measured by ultraviolet/visible transmission spectroscopy. This spectrum indicates the position of the main electronic resonances of the dye and therefore provides the most important input for theoretical modeling of the optical properties of the dyes in most contexts. Most theoretical models of the optical properties of dye-containing systems, however, require knowledge of the wavelength-dependent complex linear optical polarizability α(λ). For this, one or several Lorentz oscillator profiles with resonances matching the absorption spectrum are often employed. The other parameters (broadening and relative peak intensities) are also sometimes obtained from a fit to the experimental absorption spectrum, which is closely related to the imaginary part of the polarizability. We argue in this work that this common approach presents a number of shortcomings:

the absolute amplitude of the polarizability is rarely rigorously determined;

the entire spectral shape is not well reproduced by a Lorentz model;

the real part of the polarizability is not correctly determined.

The first point will naturally affect any quantitative predictions. Although the other two points may appear less important, we will in fact show that they are critical to the correctness of theoretical predictions. We propose alternative methods to remedy those shortcomings and obtain an accurate polarizability. For convenience, we also propose a class of possible analytical fits suitable for typical dyes and demonstrate their applicability to five commonly used dyes: Rhodamine 6G, Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Nile Blue A, and Methylene Blue. Our arguments are general but will be illustrated on the topical case of dye–nanoparticle hybrid systems.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Determination of an Accurate Dye Polarizability

2.1.1. General Considerations

The complex linear optical polarizability at a given wavelength λ (or frequency ω = 2πc/λ) is a physical quantity relating the optical response of a dye, characterized by an oscillating induced dipole p(t), to an electromagnetic excitation characterized by an electromagnetic field E(t) oscillating at the same frequency. Using complex notations for oscillating quantities, that is, A(t) = Re[A e–iωt] and assuming a linear response, this results in the simple relation: p = α̃E. As this is a microscopic property, E in this expression should be understood as the microscopic electric field, which differs from the macroscopic field when the dye is embedded in a medium like water. The two quantities are simply related using an appropriate local-field correction.4,8,9 Within this definition, α̃ therefore corresponds to the polarizability in vacuum, and the solvent effect is accounted for by the local-field correction (see first term in eq 1 below). We therefore assume that the chemical structure of the dye is unchanged when dissolved in water. In principle, α̃ is a tensor, but in many situations the optical properties are averaged over a large number of dyes with random orientations. In this case (and assuming no optical activity), the results only depend on a scalar effective polarizability defined as α = (1/3)Tr(α̃) = (1/3)(α̃xx + α̃yy + α̃zz), where Tr(·) denotes the trace of the tensor. For simplicity, we will focus primarily on this effective polarizability in this work, but the discussion equally applies to tensorial polarizabilities. For the common case of a dye with a uniaxial response (assumed along the z axis), we, for example, simply have αzz = 3α. In general, α is complex; as for any linear response function, its imaginary part is related to losses, and its real part to dispersion.

2.1.2. Imaginary Part

α(λ) is difficult to fully measure directly for a dye. However, its imaginary part over a finite wavelength range can be obtained from the absorption spectrum or equivalently the absorption cross section σabs(λ). For example, for a dye in a solution of refractive index nM, we have (see Section 4.6.2 in ref (4)).

| 1 |

We note that the first term is related to the local-field correction8,9 and is often incorrectly omitted, leading to errors in the absolute magnitude of α (this term is, for example, of the order 0.63 in water). For dyes in solution, scattering is negligible, and the absorption spectrum can therefore be measured from standard UV/vis (extinction) spectroscopy.

2.1.3. Real part

The real part of the complex polarizability can, in principle, be inferred from the imaginary part through the Kramers–Kronig (KK) relations,10−12 which are a consequence of causality for a linear response function like α.13 Those are typically expressed in terms of frequency rather than wavelength, namely

| 2 |

where  denotes

the Cauchy principal value. To

compute this integral, one, moreover, needs to use the symmetry property13

denotes

the Cauchy principal value. To

compute this integral, one, moreover, needs to use the symmetry property13

| 3 |

This approach can be cumbersome in practice due to the integration and the principal value (an example implementation in Matlab is given as Supporting Information for convenience). Alternatively, the imaginary part can be fitted using an analytic function that is KK consistent by construction. We will come back to this approach in Section 2.2 and focus here on the use of the KK transform to obtain an accurate real part of the polarizability.

It is important to first note that the use of eq 2 requires knowledge of the imaginary part over the entire spectral range where transitions occur, which, for dyes, should include, in particular, all the UV/near-UV transitions. To illustrate this, the absorption spectrum of Rhodamine 6G in water was measured using UV–vis spectroscopy over the range 200–1000 nm. The imaginary part of α is derived using eq 1, see Figure 1a, and assumed to be zero outside that range. The real part is then calculated numerically from the KK integrals (eqs 2 and 3) and shown in Figure 1b. The effect of including UV peaks is also investigated by comparing this to the same calculation but setting the absorbance to zero below 400 nm. The difference between the two, that is, the real part of the polarizability due to UV absorption, is shown in the inset of Figure 1b. As expected, this exhibits strong features in the near-UV region but also a nonzero contribution above 400 nm. If we are only interested in the response in the visible region, then this contribution from the UV peaks is real and approximately constant at αUV = 2.6 × 10–39 S.I. This value is large enough to affect theoretical predictions quantitatively and qualitatively in some cases and must therefore be taken into account.

Figure 1.

(a) Imaginary part of the polarizability of Rhodamine 6G, as obtained using eq 1 from its UV–vis absorption spectrum including the near-UV peaks down to 200 nm (red) or only the peaks above 400 nm (blue). The molecular structure of Rhodamine 6G is also shown as an inset. (b) Real part of the polarizability of Rhodamine 6G calculated from the KK transformation of (a) with (red) or without (blue) the near-UV peaks (<400 nm) included. The difference between the two is shown in the inset and shows the effective contribution to the real polarizability from the UV peaks is approximately constant in the visible part of the spectrum (above ∼450 nm).

2.1.4. Link to Static Polarizability

It is not, however, always practical to measure the absorption spectrum over this wide range, and higher-energy transitions could also exist below 200 nm in some systems. It is therefore desirable to provide an alternative method based on the measurement of the visible spectrum only. Because the UV contribution to α(λ) is approximately constant in the visible range (Figure 1b), we can write the polarizability in the visible range as

| 4 |

where αvis(λ) is the polarizability obtained via KK transform or analytical fits of the visible region only and αconstant is a real constant accounting for the contribution of all the higher-energy transitions. To determine αconstant without measuring the entire spectrum, we propose to use the asymptotic behavior of the polarizability at long wavelength: α(λ → ∞) has a very precise physical meaning as it can be identified with the (real) static electric polarizability of the dye αstatic, that is, the response of the dye to an applied electric field in the DC limit. For example, from the measurement of the full absorption spectrum of Rhodamine 6G in Figure 1, we can deduce by KK integration that αstatic = 6. 1 × 10–39 S.I. This is a lower estimate as it assumes that there is no optical absorption below 200 nm. Conversely, from a knowledge of the static polarizability, we can adjust the constant offset αconstant in eq 4 to ensure that α(λ → ∞) = αstatic. To avoid measuring the full spectrum, one therefore only needs an independent method of determining αstatic.

2.1.5. DFT Estimates of the Static Polarizability

We argue that DFT calculations (as detailed in the Section 4) can achieve this to a sufficient accuracy. From those, the static polarizability tensor in vacuum is calculated and the effective scalar static polarizability derived as α = (1/3)Tr(α̃). For example, for Rhodamine 6G (R6G) we obtain αDFT = 6. 94 × 10–39 S.I., in good agreement with the lowest bound deduced from the full spectrum measurement. Similar conclusions were reached by comparing measurements and DFT calculations of other common dyes as summarized in Table 1. The level of agreement suggests that both approaches provide a reliable estimate of the vacuum static polarizability. This provides strong reassurance of the validity of the real polarizability determined from a full-spectrum measurement of the dye absorption. Moreover, one could also use the DFT prediction for the static polarizability in conjunction with an absorption spectrum measurement in the region of interest only (which should, nevertheless, include all the lower-energy peaks) to determine an accurate polarizability over that region.

Table 1. Vacuum Static Polarizability Estimated using the KK Transformation of the Dye Absorption Spectrum above 200 nm and eq 1 Compared to that Calculated Using Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Five Commonly Used Dyesa.

| dye | total experimental Re{α} (×10–39 S.I.) | UV peaks Re{α} (×10–39 S.I.) | αstatic – DFT (×10–39 S.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodamine 6G | 6.1 | 2.6 | 6.94 |

| Rhodamine 700 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 6.63 |

| Nile Blue | 5.9 | 1.9 | 5.8 |

| Methylene Blue | 5.8 | 1.6 | 5.3 |

| Crystal Violet | 8.3 | 1.9 | 7.45 |

The two values show good agreement across the investigated dyes, indicating that both are reasonable choices for the static polarizability. The contribution of UV peaks (corresponding to the error if the 200–400 nm region is removed from the KK integral) is also explicitly given for reference.

It is worth emphasizing that we here use DFT to compute vacuum static polarizabilities. The solvent effect is taken into account through its local-field correction only (eq 1). One could alternatively directly compute from DFT the polarizability in water using, for example, polarizability continuum models.14,15 Such an approach would potentially account for solvent-induced changes in the chemical structure in addition to local-field effects. However, the level of agreement observed in Table 1 suggests that those effects are secondary to the local-field effects, at least in the cases studied here.

2.2. Analytical Fits of the Dye Polarizability

While the KK method from eq 2 provides a direct relationship between Im(α) and Re(α), it requires numerical integration. The integral contains a pole when ω = ω′ and is evaluated using the Cauchy method by taking the principal value of the integral. The method is therefore not as straightforward as an analytical fit to the experimental data. Moreover, any noise in the experimental data could have a large impact on the KK transformation for frequency values in the vicinity of the pole and may lead to incorrect values for Re[α]. Thus, the alternative of fitting the imaginary part using an analytic function that is KK consistent by construction is appealing. As discussed earlier, the contribution of high-energy transitions may be approximated as an additional constant. Often, a single peak is not enough to accurately describe the dye absorption spectrum and one may then use a sum of peaks

| 5 |

where αj is the contribution from the jth peak in the absorption spectrum.

2.2.1. Lorentz and Voigt models

The simplest and most commonly used KK-consistent function for a resonance peak is the Lorentz oscillator (written here in terms of wavelength rather than frequency)

|

6 |

where αj, λj, and Γj are parameters to be determined, related to the amplitude, resonance wavelength, and broadening, respectively. The imaginary part is then very similar to a Lorentzian. However, although such fits qualitatively describe the location of the dye resonances, they rarely provide an accurate quantitative fit to the absorption spectrum, especially to the low-energy tail of the lower-energy peak. A more accurate fit of the absorption spectrum could be achieved with a Gaussian profile. The simplest KK-consistent model achieving this is a Voigt-type lineshape, which has been used to model the dielectric function of solids16 but only sporadically in the context of dye polarizability.17,18 It represents a collection of Lorentz oscillators whose resonance frequencies are Gaussian distributed. It is therefore KK consistent by construction and its imaginary part is very similar to the Voigt profile, explicitly

|

7 |

The Lorentz model is compared with a more accurate fit based on the Voigt model in Figure 2, where we focus on the main absorption (low energy) peak of Rhodamine 6G at 526 nm. In both cases, αconstant was adjusted to ensure the same static polarizability of α(λ → ∞) = αstatic = 6.94 × 10–39 S.I, and eq 1 is used to link the absorption cross section to the imaginary part of the polarizability. It is obvious that the two fits are significantly different outside the immediate region of the 526 nm peak, with the Lorentzian having a pronounced tail extending too far in the low-energy region, where the optical absorption shows a sharp drop, as expected, for a discrete electron energy transition broadened only by absorption from different thermally excited states. Also, the difference in the value of the real part (Figure 2b) is evident below ∼450 nm, where the two fits lead to differing near-constant values of the real part. The two models, in fact, predict a different sign for the real part of the polarizability in this region. Such a difference can be crucial to obtaining the correct qualitative predictions, as will be shown in Section 2.3. An additional constant could be added to the Lorentz polarizability to make the real parts of both models agree below ∼450 nm, but this conversely leads to a discrepancy at α(λ → ∞), which would be equivalent to arbitrarily changing the static polarizability of the dye. It is therefore clear from Figure 2 that small inaccuracies in the fit of the imaginary part (in particular, the correct lineshape) have large implications on the accuracy of the real part of the polarizability, which has, thus far, been largely overlooked in most models in the literature.

Figure 2.

(a) Fits of the 526 nm peak of the measured absorption cross section of 10 μM Rhodamine 6G in water (pink) using eq 1 and a polarizability model with a single Lorentz oscillator (green) or a single Voigt fit (blue). (b) Corresponding real part of the polarizability functions where the condition α(λ → ∞) = αstatic = 6. 94 × 10–39 S.I. is enforced for both Lorentzian and Voigt fits.

2.2.2. Critical Points Fits

We therefore focus on obtaining accurate KK-consistent fits of the absorption spectrum in the visible. For this, two transitions are needed for Rhodamine 6G, as shown in Figure 3a,b. A double Lorentz fit is inadequate as it tails too far into the low-energy region, as discussed before. The double Voigt fit is significantly better and also predicts the correct real part when compared with that of the direct KK method (Figure 3b). However, it is, like the KK transformation, more computationally challenging because of its integral form (eq 7). It is, thus, desirable to find a simpler, yet accurate, closed-form analytic functional fit.

Figure 3.

(a) Fit of the measured visible Rhodamine 6G absorption cross section (purple) with a polarizability modeled as two Lorentz (green) or two Voigt (blue) oscillators. (b) Corresponding real parts of the polarizability, compared with that obtained from the KK transformation of the experimental data. A constant is added in each case to enforce the condition α(λ → ∞) = αstatic = 6. 94 × 10–39 S.I. (c, d) Same as (a, b) with a double critical point fit (red). The inset in (c) shows the individual contributions of each of the two critical points. The black dotted line in (d) delineates the region for which the fit is better than 10% for both the real and imaginary parts.

To this end, we propose employing a critical point approach. Critical points were originally introduced in the context of semiconductors.19−21 The absorption of semiconductors occurs at the positions of the Van Hove singularities in the joint density of states (jDOS),22 and critical point lineshapes can be used to model the optical properties associated with these poles. They have also, more recently, been used to model the dielectric functions of metals.22,23 We here propose and demonstrate that such functions, which are KK-consistent by construction, can also be used to model the polarizability of dyes. We will use the following functional form23

|

8 |

where Aj, λj, γj, ϕj and μj are parameters. Aj relates to the amplitude, λj to the resonance wavelength, and γj to the broadening. ϕj is a phase factor resulting in an asymmetry of the absorption peak. μj is here not used as a fitting parameter but can be used to describe different classes of fits (in a formal critical point derivation, it would be associated with the order of the pole in the jDOS). We found that values of μj of either 1 or 2 were adequate for most of our fits. It is also worth noting that the first term in the critical point expression will dominate the function as the second (off-resonant) term is negligible in the region where λ ≈ λj. It is, nevertheless, important to include it to achieve KK consistency.

The visible absorption spectrum of Rhodamine 6G was fitted with two critical points, as shown in Figure 3c,d. The resulting fits are comparable in quality to the Voigt fits showing that the proposed model can be used as a simpler yet equally effective alternative to the Voigt function and is a distinct improvement on the commonly used Lorentz oscillator. The usefulness of the critical point fit is further demonstrated by applying it to other common dyes: Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Methylene Blue, and Nile Blue A. The fits and their respective parameters are given in the Supporting Information. In all those cases, only the absorption peaks in the visible region are fitted and the real part is corrected using the static polarizability obtained from DFT, as explained in the previous section.

Due to the stated importance of the UV peaks for the correct determination of the real polarizability, it is important to find the region of validity of this approach by comparing it to that obtained from the KK transform of experimental data, including UV peaks. In the case of Rhodamine, shown in Figure 3c,d, the critical point model has a relative error of less than 10% for both the real and imaginary parts of the polarizability over the entire range above ∼470 nm (note that the regions where the real part crosses zero are excluded from this analysis to avoid the singularity). This reduces to 6% above 475 nm. For accurate predictions below these wavelengths, we recommend adding analytical fits to represent the near-UV transitions or using the explicit KK transform of experimental data containing higher-energy transitions. A similar analysis was carried out for other dyes, as summarized in the Supporting Information.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that the critical point model for dyes, although KK-consistent and accurate, does not necessarily have a direct physical interpretation. As seen in the inset of Figure 3c, the individual critical point contributions, when considered separately, may exhibit negative absorbance in certain regions. This is unphysical and shows that a single critical point with arbitrary parameters cannot, in general, be used to model a single electronic transition. However, the overall fit, through the summation of these contributions, provides an accurate KK-consistent representation of the polarizability. In the interest of simplifying expressions for the polarizability, critical points can therefore be used as a substitute for Voigt fits, especially to accurately fit the low-energy tail of the spectra. With this in mind, we believe that a sum of Lorentz oscillators and critical points should provide a practical and accurate description of the polarizability of most molecular dyes over any region of interest (which may or may not include the UV/near-UV peaks). Several examples are included in the Supporting Information.

2.3. Application to Nanoparticle–Dye Interactions

While our arguments are quite general, we now illustrate them in the topical case of dye–metal nanoparticle hybrids. Indeed, there has been a significant and ongoing effort to understand and exploit the interaction between the surface plasmon resonance of a substrate, such as a metallic nanoparticle, and the optical resonance of molecules adsorbed onto its surface. The coupling between those two resonances leads to a molecule–nanostructure hybrid with distinct modified optical properties.24−27 Depending on the strength of this coupling, this may result in resonance shifts, peak splitting, and the appearance of Fano profiles. Anticrossing of the resonances as a function of coupling strength has been observed in several systems. Gold or silver nanoparticles or nanoshells are typically used as substrates and are coupled to quantum emitters, such as excitons in J-aggregates,25,27−31 quantum dots,32,33 and isolated dye molecules.18,26,34 The novel properties of the resulting hybrid states have been earmarked for advancement in surface-enhanced spectroscopies,4,24,34 molecular sensing,24,34,35 lasing,24,26,34,35 as well as building blocks for quantum information systems.26

In the vast majority of those studies, the optical properties of the dye layer are generally modeled with a single25−27,29,31,32 or double34 Lorentz oscillator, with no considerations made to the shortcomings discussed earlier. In particular, little or no effort is devoted to rigorously match the absolute polarizability amplitude to the measured absorption cross section using eq 1 (which may arbitrarily affect the coupling strength) or to find an accurate αconstant or αstatic. We argue that an accurate model of the polarizability (both imaginary and real parts) is, in fact, crucial to any quantitative predictions and even qualitative interpretations in some cases.

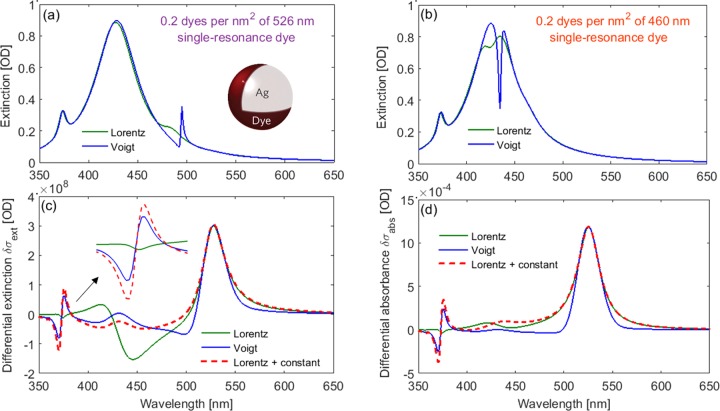

For this, we used Mie theory and the effective shell model18,27,28,31,36−40 to calculate the optical response of silver nanoparticles coated with a thin layer of adsorbed dyes. The effect of the difference in the real part of different functions for the polarizability on plasmon–molecule interactions can be investigated by comparing the predicted absorbance of the dye on the nanoparticle surface. For illustration, the dye was assumed to have a single resonance at 526 nm, as in Figure 2. Representative results of those calculations are summarized in Figure 4. For a surface dye layer with a relatively high concentration of molecules, the absorption signal of the dye is strong enough to be observed in the predicted extinction spectrum of the dye-coated colloid, as shown in Figure 4a, where the differences between the polarizability models are observable. With the Voigt lineshape, we observe an intense, sharp dye resonance peak (akin to those observed in J-aggregates), whereas a much lower broad peak is predicted if the Lorentz model is used. A difference in the dye resonance peak position is predicted by the two models as well as a small difference in the colloid resonance intensity. If we shift the dye resonance to 460 nm to increase coupling, we again observe a large discrepancy between the two models as shown in Figure 4b. If the Voigt model is used, the predicted absorption spectrum shows a dip, that is, a seeming splitting of the colloid resonance, commonly associated with the strong coupling regime, whereas the Lorentz model predicts only minor modifications of the colloid resonance under these conditions. We do not intend to discuss the meaning of those shifts/splittings here but simply to point out the fact that two polarizability models with identical resonances can result in drastically different predictions just because they have slightly different spectral shapes around the resonance. Thus, qualitatively different conclusions may be reached simply by choosing a different model for the polarizability.

Figure 4.

(a) Predicted extinction spectrum of the 60 nm diameter silver nanoparticles coated with a uniform dye layer of 0.2 dye molecules per nm2 (∼1000 dyes per NP) with polarizabilities given by either the same Lorentz (green) or Voigt (blue) models as in Figure 2. Same as (b) with the resonance shifted to 460 nm to increase coupling. (c) Same as (a) for a low-coverage dye layer of 0.01 molecules per nm2 on the colloid surface. The differential extinction spectrum (where the colloid-only spectrum has been subtracted) is shown to highlight the influence of the dye layer. The dashed line shows the result for the Lorentz oscillator where a real constant has been added to make it coincide with the Voigt model in the 450 nm region, as shown as a dashed line in Figure 2b (note that this also changes α(λ → ∞) and could not represent the same physical dye). (d) Same as (c) but showing differential absorption instead of extinction.

Similar observations can be made for low dye concentrations. In this case, the dye/nanoparticle interactions can be revealed by considering the differential extinction (Figure 4c) and differential absorbance (Figure 4d) spectra of the colloid–molecule system, referenced against the colloid-only system.18 The region of the nanoparticle quadrupole peak, around 375 nm, is an excellent example of the importance of the real part, as the peak is sufficiently far away from the dye resonance that the imaginary parts of the two models are equivalent in this region and will therefore not affect the predicted coupling. The feature observed in Figure 4c,d at ∼375 nm is indicative of a wavelength shift of the quadrupole peak. If the Voigt lineshape is used, we observe a redshift, whereas a small blueshift is predicted in the Lorentz case. This remarkable discrepancy can, in fact, be simply explained: It is well documented that plasmon resonances redshift/blueshift for the higher/lower refractive index of the surrounding medium and here the sign of the real part of the dye polarizability governs whether the refractive index of the dye layer is higher (for a positive real part) or lower (negative real part) than that of the surrounding medium, here water. To confirm this interpretation, one can add a constant to the Lorentz polarizability to make the real parts of both models identical in the region of the colloid quadrupole peak (as shown as a dashed line in Figure 2b), and a similar shift is then observed for both models. The addition of this real constant is, however, unphysical, as it also changes the static polarizability of the dye. The fact that the predicted results, even on a qualitative level, can be strikingly different with small differences in either the spectral shape or the static polarizability shows the importance of using a model accurately representing those aspects.

3. Conclusions

The wavelength-dependent complex linear polarizability is, arguably, the most important parameter when modeling the optical properties of dyes interacting in a variety of contexts. While a simple Lorentz oscillator captures mostly the influence of the dye resonance positions, we have highlighted in this work a number of additional aspects playing a critical role under some circumstances, notably, the spectral shape of the absorption peaks around the resonance and the offset in the real part of the polarizability. We have discussed, in detail, the factors affecting the correct determination of those parameters and proposed practical methods for obtaining an accurate dye polarizability. The use of the static polarizability, as calculated from DFT, was, in particular, shown to be an effective way of accounting for high-energy transitions that cannot always be measured. In addition, we have proposed and applied an alternative closed-form analytic model based on critical point analysis for the polarizability of dyes and investigated its applicability and range of validity for five common dyes: Rhodamine 6G, Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Nile Blue A, and Methylene Blue. This model represents a significant improvement over the Lorentz oscillator model, as well as an equally effective substitute for cumbersome methods, such as the numerical integration of the KK transform or the Voigt polarizability model.

The importance of an accurate polarizability model, and, in particular, a correct value of the real part of the polarizability, on theoretical electromagnetic models of dye systems was demonstrated through examples of Mie Theory calculations of nanoparticle–dye interactions. Different polarizability models and different values for the static polarizability can lead to qualitatively and quantitatively different theoretical predictions. We expect that a more careful modeling of the dye polarizability, such as the one proposed here, will be of great benefit to further our understanding of the mechanisms governing dye–nanoparticle interactions.

4. Methods

Rhodamine 6G, Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Nile Blue A, and Methylene Blue were purchased from Sigma Aldrich in powder form and mixed with ultrapure MilliQ water to the desired stock concentration (in the range 10–100 μM). Silver nanoparticles (60 nm diameter, 2 × 1010 particles/mL in citrate) were purchased from Nanocomposix. UV–vis measurements were carried out on an Agilent 8453 Diode Array Single Beam UV–Visible Spectrophotometer. A quartz cuvette was used to obtain spectral information down to ∼200 nm. A single 5 mL cuvette was used for all measurements to avoid any spectral changes due to cuvette variation.

DFT calculations were used to predict the static polarizability of dyes. Specifically, we used the package Gaussian0941 and employed the hybrid functional PBE042−44 with the triple zeta basis set def2tzvp(45,46) to perform molecular geometry optimizations and polarizability calculations.

Theoretical predictions of the optical properties of a dye layer were carried out using an isotropic shell model, as used in many recent studies of molecular plasmonics.18,27,28,31,36−40 This consists of solving the electromagnetic scattering problem for a metallic nanosphere covered by a thin spherical shell with an effective isotropic dielectric function that models the dye response. For simplicity, the local-field correction arising from dye/dye interactions is neglected, as is common practice (although this assumption has recently been questioned18). The local-field correction due to the embedding medium (typically water) with dielectric constant ϵM must, however, be taken into account.8 The effective dielectric function therefore takes the form ϵ(λ) = ϵM + [(ϵM + 2)/3][cD/ϵ0]α(λ), where cD is the number of dye molecules per unit volume.18 Calculations were performed in Matlab with publicly available codes.47 The dielectric function of silver is taken from the analytical fit in ref (4).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthias Lein from Victoria University of Wellington for help with the DFT calculations and their interpretation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00171.

Matlab code for KK transform, fit parameters, and information cards for the polarizability of Rhodamine 6G, Rhodamine 700, Crystal Violet, Nile Blue A, and Methylene Blue (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Shank C. V. Physics of dye lasers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1975, 47, 649–657. 10.1103/RevModPhys.47.649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T.; Tinnefeld P. Photophysics of Fluorescent Probes for Single-Molecule Biophysics and Super-Resolution Imaging. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012, 63, 595–617. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T.; Li N.; Fang X. Single-Molecule Fluorescence Imaging in Living Cells. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2013, 64, 459–480. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru E. C.; Etchegoin P. G.. Principles of Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy and Related Plasmonic Effects; Elsevier, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru E. C.; Etchegoin P. G. Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman spectrosocopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2012, 63, 65–87. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés E.; Etchegoin P. G.; Le Ru E. C.; Fainstein A.; Vela M. E.; Salvarezza R. C. Monitoring the Electrochemistry of Single Molecules by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18034–18037. 10.1021/ja108989b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitre S. P.; McTiernan C. D.; Scaiano J. C. Library of Cationic Organic Dyes for Visible-Light-Driven Photoredox Transformations. ACS Omega 2016, 1, 66–76. 10.1021/acsomega.6b00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo S. R.; Wilson M. K. Infrared intensities in liquid and gas phases. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 2376. 10.1063/1.1741884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt G.; Wagner W. G. On the calculation of absolute Raman scattering cross sections from Raman scattering coefficients. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1966, 19, 407–411. 10.1016/0022-2852(66)90262-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kramers H. A.La diffusion de la lumiere par les atomes. Atti del Congresso Internazionale dei Fisici, 1927.

- Kronig R. d. Algemeene theorie der diëlectrische en magnetische verliezen. Ned. T. Natuurk 1942, 9, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren C. F. What did Kramers and Kronig do and how did they do it?. Eur. J. Phys. 2010, 31, 573. 10.1088/0143-0807/31/3/014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toll J. S. Causality and the dispersion relation: logical foundations. Phys. Rev. 1956, 104, 1760. 10.1103/PhysRev.104.1760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egidi F.; Giovannini T.; Piccardo M.; Bloino J.; Cappelli C.; Barone V. Stereoelectronic Vibrational, and Environmental Contributions to Polarizabilities of Large Molecular Systems: A Feasible Anharmonic Protocol. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2014, 10, 2456–2464. 10.1021/ct500210z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel R.; Bormann D. An infrared dielectric function model for amorphous solids. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 71, 1–6. 10.1063/1.350737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W.; Ambjörnsson T.; Apell S. P.; Chen H.; Wang J. Observing plasmonic-molecular resonance coupling on single gold nanorods. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 77–84. 10.1021/nl902851b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby B. L.; Auguié B.; Meyer M.; Pantoja A. E.; Le Ru E. C. Modified optical absorption of molecules on metallic nanoparticles at sub-monolayer coverage. Nat. Photon. 2016, 10, 40–45. 10.1038/nphoton.2015.205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona M.Solid state physics. Supplement 11, Modulation spectroscopy; Academic Press: New York; London, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Forouhi A. R.; Bloomer I. Optical properties of crystalline semiconductors and dielectrics. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 38, 1865. 10.1103/PhysRevB.38.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. C.; Garland J. W.; Abad H.; Raccah P. M. Modeling the optical dielectric function of semiconductors: extension of the critical-point parabolic-band approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 11749. 10.1103/PhysRevB.45.11749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux D.; Vallières S.; Besner S.; Muñoz P.; Mazur E.; Meunier M. An analytic model for the dielectric function of Au, Ag, and their alloys. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2014, 2, 176–182. 10.1002/adom.201300457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etchegoin P. G.; Le Ru E. C.; Meyer M. An analytic model for the optical properties of gold. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 164705 10.1063/1.2360270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törmä P.; Barnes W. L. Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and emitters: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 013901 10.1088/0034-4885/78/1/013901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLacy B. G.; et al. Coherent Plasmon-Exciton Coupling in Silver Platelet-J-aggregate Nanocomposites. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2588–2593. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikkaraddy R.; de Nijs B.; Benz F.; Barrow S. J.; Scherman O. A.; Rosta E.; Demetriadou A.; Fox P.; Hess O.; Baumberg J. J. Single-molecule strong coupling at room temperature in plasmonic nanocavities. Nature 2016, 535, 127. 10.1038/nature17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fofang N. T.; Park T.-H.; Neumann O.; Mirin N. A.; Nordlander P.; Halas N. J. Plexcitonic Nanoparticles: Plasmon-Exciton Coupling in Nanoshell-J-Aggregate Complexes. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 3481–3487. 10.1021/nl8024278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengin G.; Johansson G.; Johansson P.; Antosiewicz T. J.; Käll M.; Shegai T. Approaching the strong coupling limit in single plasmonic nanorods interacting with J-aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3074 10.1038/srep03074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; et al. Resonance Coupling in Silicon Nanosphere-J-Aggregate Heterostructures. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 6886–6895. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balci S.; Kucukoz B.; Balci O.; Karatay A.; Kocabas C.; Yaglioglu H. G. Tunable Plexcitonic Nanoparticles: A Model System for Studying Plasmon-Exciton Interaction from Weak to Ultrastrong Coupling Regime. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 2010. 10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlather A. E.; Large N.; Urban A. S.; Nordlander P.; Halas N. J. Near-field mediated plexcitonic coupling and giant Rabi splitting in individual metallic dimers. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3281–3286. 10.1021/nl4014887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile M. J.; Barnes W. L.. Hybridized Exciton-Polariton Resonances in Core-Shell Nanoparticles. 2016, arXiv:1609.04932. arXiv.org e-Print archive. https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.04932.

- Wu X.; Gray S. K.; Pelton M. Quantum-dot-induced transparency in a nanoscale plasmonic resonator. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 23633–23645. 10.1364/OE.18.023633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengin G.; Gschneidtner T.; Verre R.; Shao L.; Antosiewicz T. J.; Moth-Poulsen K.; Käll M.; Shegai T. Evaluating Conditions for Strong Coupling between Nanoparticle Plasmons and Organic Dyes Using Scattering and Absorption Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 20588. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b00219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny L.; Van Hulst N. Antennas for light. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 83–90. 10.1038/nphoton.2010.237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola A.; Di Stefano O.; Stassi R.; Saija R.; Savasta S. Ultrastrong coupling of plasmons and excitons in a nanoshell. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11483–11492. 10.1021/nn504652w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antosiewicz T. J.; Apell S. P.; Shegai T. Plasmon-exciton interactions in a core-shell geometry: from enhanced absorption to strong coupling. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 454–463. 10.1021/ph500032d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Shao L.; Woo K. C.; Wang J.; Lin H.-Q. Plasmonic-molecular resonance coupling: plasmonic splitting versus energy transfer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 14088–14095. 10.1021/jp303560s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W.; Ambjörnsson T.; Apell S. P.; Chen H.; Wang J. Observing Plasmonic- Molecular Resonance Coupling on Single Gold Nanorods. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 77–84. 10.1021/nl902851b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G. P.; Wurtz G. A.; Hranisavljevic J. Coherent coupling of molecular excitons to electronic polarizations of noble metal nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 2121–2125. 10.1021/nl0488228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.et al. Gaussian09, revision E.01.; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Perdew J. P.; Burke K.; Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Barone V. Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: The PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6158–6170. 10.1063/1.478522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamo C.; Cossi M.; Scalmani G.; Barone V. Accurate static polarizabilities by density functional theory: assessment of the {PBE0} model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 307, 265–271. 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)00515-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F.; Ahlrichs R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. 10.1039/b515623h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru E.; Etchegoin P.. SERS and Plasmonics Codes (SPlaC). http://www.vuw.ac.nz/raman/book/codes.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.