Abstract

Three novel derivatives of (E)-N′-nitrobenzylidene-benzenesulfonohydrazide (NBBSH) were synthesized by a condensation method from nitrobenzaldehyde and benzenesulfonylhydrazine reactants in low to moderate yields, which crystallized in methanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, and ethanol. NBBSH derivatives were totally characterized using various spectroscopic techniques, such as Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H NMR), and carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectroscopy. The molecular structure of the NBBSH derivates was confirmed by the single crystal X-ray diffraction method and used for potential detection of a selective heavy metal ion, mercury (Hg2+), by a reliable I–V method. A thin coating of NBBSH derivatives was deposited on a glassy carbon electrode (surface area = 0.0316 cm2) with a binder (nafion) coating to modify a sensitive and selective Hg2+ sensor with a short response time in phosphate buffer. The modified cationic sensor exhibited enhanced chemical performances, such as higher sensitivity, linear dynamic range, limit of detection (LOD), reproducibility, and long-term stability toward Hg2+. The calibration curve was found to be linear over a wide range of Hg2+ concentrations (100.0 pM–100.0 mM). The sensitivity and LOD were considered to be ∼949.0 pA μM–1cm–2 and 10.0 ± 1.0 pM (S/N = 3), respectively. The sensor was applied to the selective measurement of Hg2+ in spiked water samples to give acceptable and satisfactory results.

Introduction

Various organic compounds consist of electron-donating functional groups via interaction of various metal constituents and have a large number of potential applications in catalysis, biological, environmental, organometallic, and medicinal fields.1−4 Sulfonamides are acknowledged as sulfa drugs, which are used as antibiotics in bacterial-type infections in animals including humans. Sulfa drugs are also used in the treatment of bacillary dysentery, conjunctivitis, eye and gut infections, malaria, meningitis, and urinary tract infections.5 Using the single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) method, supramolecular chemistry of metal complexes of the hydrazone structure has already been explained. Tridentate ligands were synthesized and reported with a hydrazone backbone to co-ordinate with copper and iron as heavy metal ions.6 Mercury is one of the most dangerous heavy metals, which is discharged from anthropogenic sources, such as coal-fired power plants, chloralkali industry, manufacturing of electrical apparatuses (tube lights and compact fluorescent lamps), medical incinerators, municipal solid waste combustors, and solid waste incineration plants. The presence of mercury damages the environment, ecosystem, and human health (pulmonary diseases, encephalopathy, and glomerular nephritis).7−9 Mercury occurs naturally in trace amounts in natural gas and mines as elemental mercury (Hg0), inorganic mercury (Hg–I), organic mercury (Hg–O), and organic forms (Me–Hg), which are more toxic than the inorganic ones (HgCl2).10,11The key routes for human exposure to mercury contamination are consumption of fish, fish products, drinking water (as Hg2+), inhalation of mercury vapor (Hg0), marine mammals (as CH3Hg+), pharmaceutical products (vaccines and cleaning solution for contact lens as CH3CH2Hg+), and usage of personal care products.12 The bioavailability, metabolism, and toxicity of mercury are directly contingent on its chemical forms and their functional groups. Alkyl mercury has been considered more poisonous than inorganic mercury due to its bioaccumulation, chemical stability, hypertoxicity to human health, long-term migration, and biomagnifications in food stuff sequences.13,14 So, sensitive and selective determination of mercury in practical environmental real samples (RS) is a huge concern at this point of time. In the last 2 decades, several approaches were already introduced for the determination of aqueous Hg2+, such as colorimetric methods, electrochemical sensors, gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), ion chromatography (IC), LC, optical fibers and optical test strips, polymers, localized surface plasmon resonance, cold vapor atomic absorption spectrometry, cold vapor fluorescence spectrometry, and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) method.15−18

Sensors based on alkyloxymercuration, DNA, oligonucleotides, proteins, and small organic molecules were developed by various analytical methods for the detection of heavy toxic metal ions. Nowadays, advanced versions of established techniques, such as capillary electrophoresis, fluorimetry, GC, LC, MS, and spectrophotometry, are generally used for the detection and quantification of toxic pollutants. But these methods have serious limitations, as they are expensive, unstable, time-consuming, and nonreproducible, and they require preconcentration steps, which increase the risk of other hazardous by-products and result in sample loss. Therefore, it is essential to develop an easy, sensitive, and dependable sensor for the detection of poisonous heavy metal ions for environmental safety, quality control of food, protection of the ecosystem, and protection of human health.19,20 Electrochemical sensors of toxic compounds represent a significant approach that can be used to accompany previously accessible procedures owing to combined features, such as easy instrumentation, cost-effectiveness, high selectivity, high sensitivity, and better efficiency.21,22 In this research approach, a simple heavy metal ionic sensor was developed using NBBSH modified with a binder coating on a flat glassy carbon electrode (GCE). This is the first report on sensitive and selective determination of toxic and carcinogenic Hg2+ ions using 3-NBBSH via a dependable I–V performance with a small response time (r.t.).

Results and Discussion

Spectroscopic Analysis of NBBSH Molecules

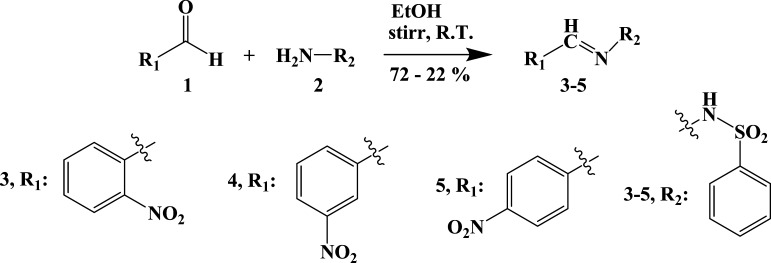

The compounds (3–5) were synthesized via a simple condensation method with the procured reactants, such as 2-nitrobenzaldehyde, 3-nitrobenzaldehyde, and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (1) and benzenesulfonylhydrazine (2) (Scheme 1).23 The synthesized compounds (3–5) were characterized using different spectroscopic instruments. The structures were established by SCXRD studies. Detailed spectroscopic analyses of the synthesized molecules (3–5) are discussed in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S9).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of NBBSH Molecules by a Condensation Method.

Crystallographic Characterization of NBBSH Molecules

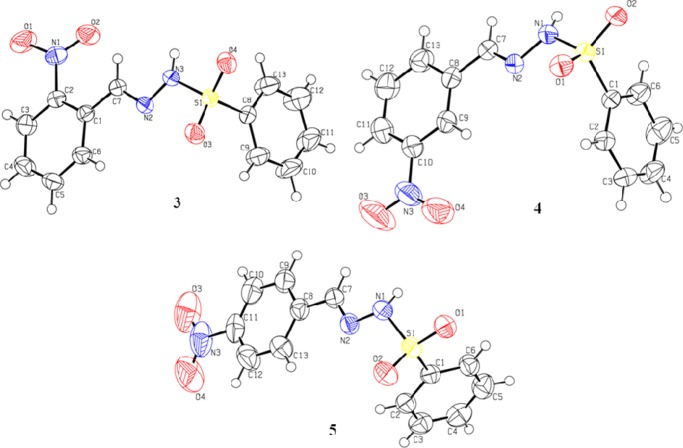

To know the three-dimensional behavior of the synthesized molecules (3–5), they are crystallized and diffracted using a single-crystal diffractometer. The unit cell is monoclinic with P21/n, P21/n, and P21/c space groups for 3–5, respectively (Table 1). The geometry around the S atoms in molecules 3–524−27 is very close to that of other related molecules already reported with <O1/S1/O2 = 120.37(9), 119.33(9), and 119.83(9)°. The dihedral angle between the two aromatic rings (C1–C6) and (C8–C13) are 83.22(7), 88.91(8), and 84.92(7)°, respectively in compounds 3–5. The nitro groups N1/O1/O2 and N3/O3/O4 are twisted at dihedral angles of 24.35(3), 8.12(2), and 6.98(5)° with respect to the aromatic rings (C1–C6 and C8–C13). The planes formed by the sulfonyl groups S1/O3/O4 and S1/O1/O2 are twisted at dihedral angles of 57.07(1), 84.65(1), and 48.51(2)° to the plane formed by the attached aromatic ring (C8–C13 and C1–C6) in molecules 3–5, respectively (Figure 1 and Tables S1–S4).

Table 1. Crystal Data and Structure Information of NBBSH Molecules.

| NBBSH

molecules |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| parameters | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| identification code | 15087 | 16018 | 16023 |

| CCDC no. | 1444297 | 1511320 | 1511321 |

| empirical formula | C13H11N3O4S | C13H11N3O4S | C13H11N3O4S |

| formula weight | 305.31 | 305.31 | 305.31 |

| temperature (K) | 293 (2) | 296.15 | 296.15 |

| crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| space group | P21/n | P21/n | P21/c |

| a (Å) | 5.5720 (3) | 12.3648 (9) | 12.0425 (7) |

| b (Å) | 23.2361 (9) | 7.6789 (5) | 7.0717 (4) |

| c (Å) | 10.6070 (4) | 15.6631 (12) | 16.8985 (10) |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 98.807 (4) | 110.751 (9) | 104.348 (6) |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| volume (Å3) | 1357.11 (10) | 1390.71 (19) | 1394.20 (14) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ρcalc (mg/mm3) | 1.494 | 1.458 | 1.455 |

| m (mm–1) | 0.259 | 0.252 | 0.252 |

| F(000) | 632.0 | 632.0 | 632.0 |

| crystal size (mm3) | 0.49 × 0.24 × 0.07 | 0.330 × 0.220 × 0.150 | 0.470 × 0.340 × 0.270 |

| 2Θ range for data collection | Mo Kα (λ = 0.7107) | 5.99–58.646° | 6.276–59.082° |

| index ranges | 6.54–58.604 | –16 ≤ h ≤ 10, –10 ≤ k ≤ 10, –20 ≤ l ≤ 21 | –15 ≤ h ≤ 16, –9 ≤ k ≤ 6, –21 ≤ l ≤ 15 |

| reflections collected | –5 ≤ h ≤ 7, –29 ≤ k ≤ 31, –13 ≤ l ≤ 14 | 6841 | 7411 |

| independent reflections | 6309 | 3302 [Rint = 0.0224] | 3339 [Rint = 0.0238] |

| data/restraints/parameters | 3211 [Rint = 0.0217, Rsigma = 0.0389] | 3302/0/194 | 3339/0/194 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 | 3211/0/193 | 1.057 | 1.042 |

| final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ(I)] | 1.024 | R1 = 0.0469, wR2 = 0.1108 | R1 = 0.0454, wR2 = 0.0979 |

| final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0441, wR2 = 0.0973 | R1 = 0.0628, wR2 = 0.1227 | R1 = 0.0735, wR2 = 0.1138 |

| largest diff. peak/hole (e Å–3) | R1 = 0.0665, wR2 = 0.1106 | 0.25/–0.34 | 0.25/–0.35 |

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of NBBSH molecules.

In compound 3, both of the planes are almost perpendicular to each other. The intermolecular interaction between the molecules through the classical and nonclassical hydrogen bonding is explained in Figure 2. A classical N–H···O linkage connects the molecules to form dimers R22(16), and these dimers are further connected to form another 18-membered ring motif R22(18). Both linkages are formed with infinite chains along the c axes, which are connected through C–H···O weak hydrogen bonding and generate a two-dimensional network along the bc plane. The compounds are further stabilized by the intermolecular classical and nonclassical hydrogen bonding interactions. N–H···O and C–H···N interactions with the symmetry code 3/2 – x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 – z connect the molecules to form nine-membered ring motifs R22(9)28 and form a polymeric infinite long chain along the b axes in molecule 4. The sulfonamide group is involved in very strong hydrogen bonding through N–H of hydrazone and O of the sulfonyl group with the symmetry code −x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 – z. Another nonclassical hydrogen bonding of C–H···O along with the N–H···O interaction produces 12-membered ring motifs R33(12), as presented in compound 5 (Table 2). Bond angle information is provided for 2-NBBSH (3), 3-NBBSH (4), and 4-NBBSH (5) in Tables S2 and S4.

Figure 2.

Unit cell diagram of NBBSH derivatives (focused on inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions).

Table 2. Hydrogen Bonds of NBBSH Compounds.

| compounds | D | H | A | d(D–H) (Å) | d(H–A) (Å) | d(D–A) (Å) | D–H–A (deg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | C7 | H7 | O2 | 0.93 | 2.23 | 2.770 (2) | 116.4 |

| C13 | H13 | O11 | 0.93 | 2.65 | 3.569 (3) | 170.1 | |

| N3 | H1 | O21 | 0.83 (2) | 2.24 (2) | 3.065 (2) | 172 (2) | |

| 1–x, −y, 1 – z | |||||||

| 4 | C6 | H6 | N11 | 0.93 | 2.58 | 3.424 (3) | 150.7 |

| N1 | H1N | O11 | 0.82 (3) | 2.10 (3) | 2.920 (2) | 173 (2) | |

| 13/2 – x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 – z | |||||||

| 5 | N1 | H1N | O11 | 0.83 (2) | 2.15 (2) | 2.973 (2) | 171 (2) |

| C9 | H9 | O22 | 0.93 | 2.45 | 3.296 (3) | 151.9 | |

| C7 | H7 | O22 | 0.93 | 2.58 | 3.379 (3) | 144.5 | |

| 1–x, 1/2 + y, 3/2 – z; 2+x, 1 + y, +z | |||||||

Application

Detection of Hg2+ by (E)-N′-(3-Nitrobenzylidene)-Benzenesulfonohydrazide (3-NBBSH)

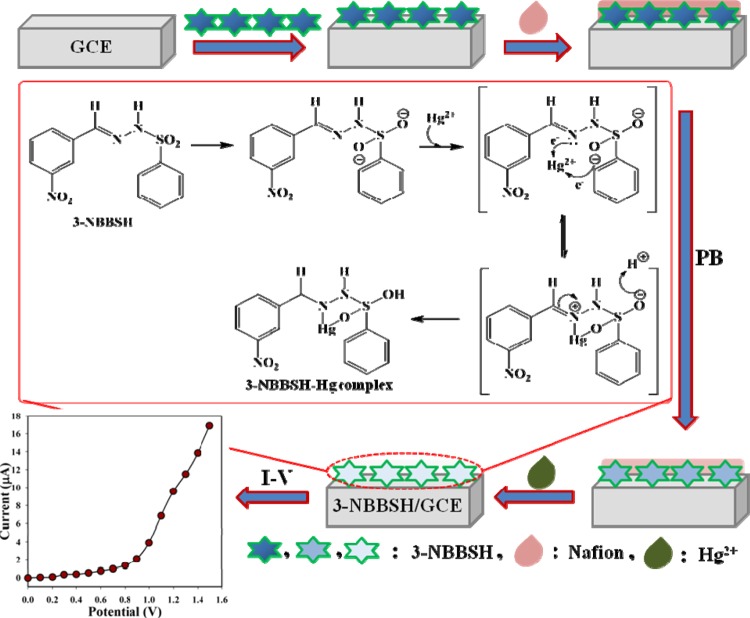

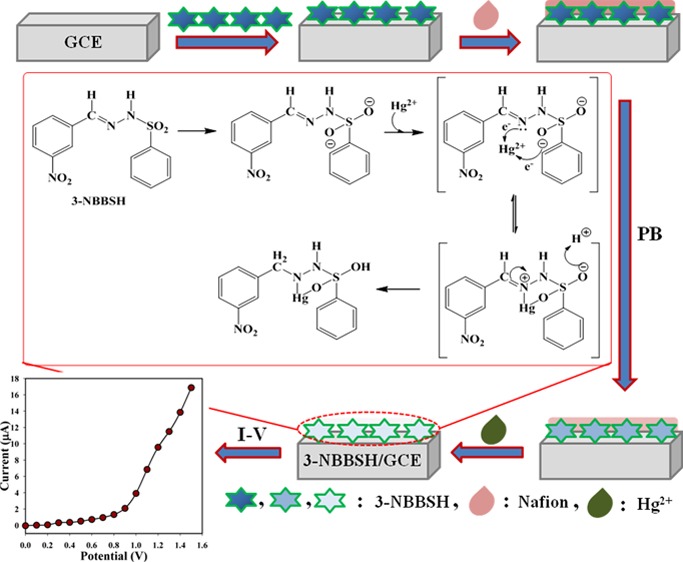

Development of the fabricated electrode with organic compounds is the preliminary stage of utilization as a metal ionic sensor under room conditions. The considerable use of NBBSH assembled as a heavy metal ionic sensor onto the GCE was evaluated for the recognition and measurement of target mercury ion, Hg2+ in the PB phase. The NBBSH/GCE sensor has various advantages such as it is chemically inert, easy to fabricate, nontoxic, and stable in air. On the basis of the I–V principle, the current responses of 3-NBBSH/GCE are considerably altered during the adsorption of Hg2+ onto sensor surfaces by electrochemical reduction. The overall process of electrode fabrication, possible means of Hg2+ reduction, and consequential I–V responses are explained and presented in a schematic diagram, Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Schematic Representation of Sensor Fabrication and Detection Mechanism of Hg2+ Ion with a 3-NBBSH/GCE Sensor.

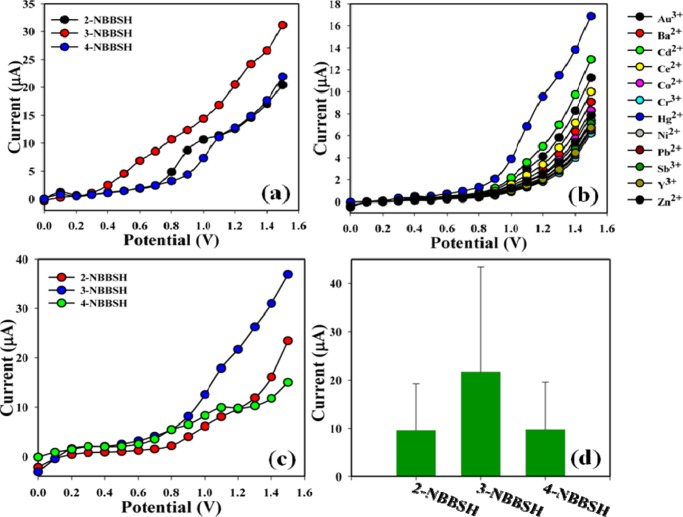

The prospective application of NBBSH assembled onto GCE as Hg2+ cationic sensor was studied and investigated for measuring and detecting the target heavy metal ion in a buffer system. NBBSH assembled onto an electrode can be used as a metal ion sensor for the detection of selective heavy metallic target cations that are hazardous, unfriendly, and carcinogenic in biological and environmental systems. First, the derivatives of NBBSH were optimized in the PB system (pH = 7.0) under room conditions. Among all derivatives, 3-NBBSH exhibits the highest I–V response compared with others (Figure 3a). Metal ions such as Au3+, Ba2+, Cd2+, Ce2+, Co2+, Cr3+, Hg2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Sb3+, Y3+, and Zn2+ were used (100.0 nM; 25 μL) to find the maximum current responses toward the 3-NBBSH-fabricated electrode. After the experiment, it was clearly observed that the sensor was more selective toward Hg2+ compared with other metallic ions (Figure 3b). The outstanding selectivity is ascribed to functional groups that exhibit strong and constant interaction with Hg2+, consequently resulting in an increased current response in the electrochemical approach. The selectivity was assessed with different derivatives of the NBBSH compound (analyte concentration used was 1.0 nM). Among them, 3-NBBSH is found to have the highest I–V response toward Hg2+ (Figure 3c); selectivity optimization is presented using a bar diagram at +1.2 V (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

(a) I–V responses of various compounds (2-NBBSH, 3-NBBSH, and 4-NBBSH) coated on a GCE (at pH = 7.0); (b) selectivity study at 100.0 nM in the presence of various cations including mercury; (c) control experiment with various synthesized compounds under identical conditions, [analyte concentration = 100.0 nM, pH = 7.0, amount: 25.0 μL, surface area of GCE = 0.0316 cm2, method: I–V, delay time = 1.0 s]; and (d) bar diagram presentation of selectivity optimization at +1.2 V.

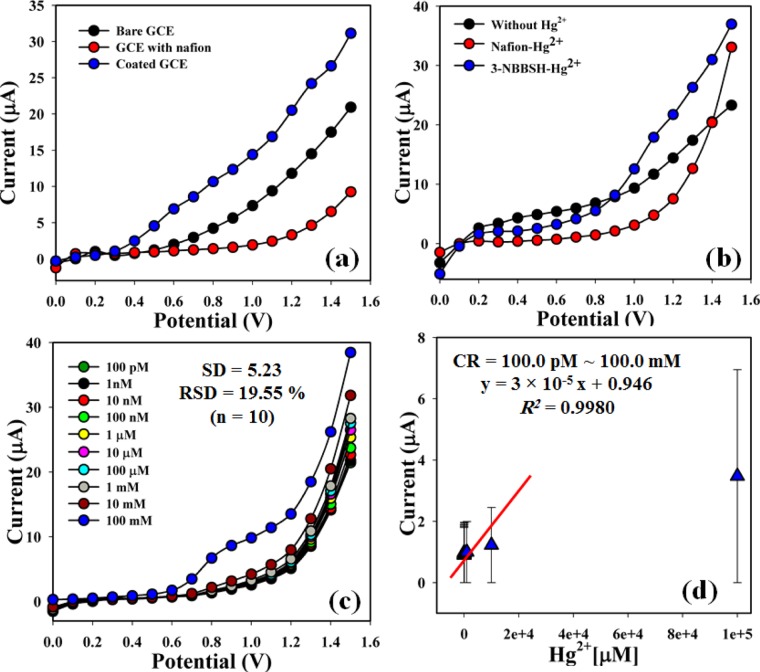

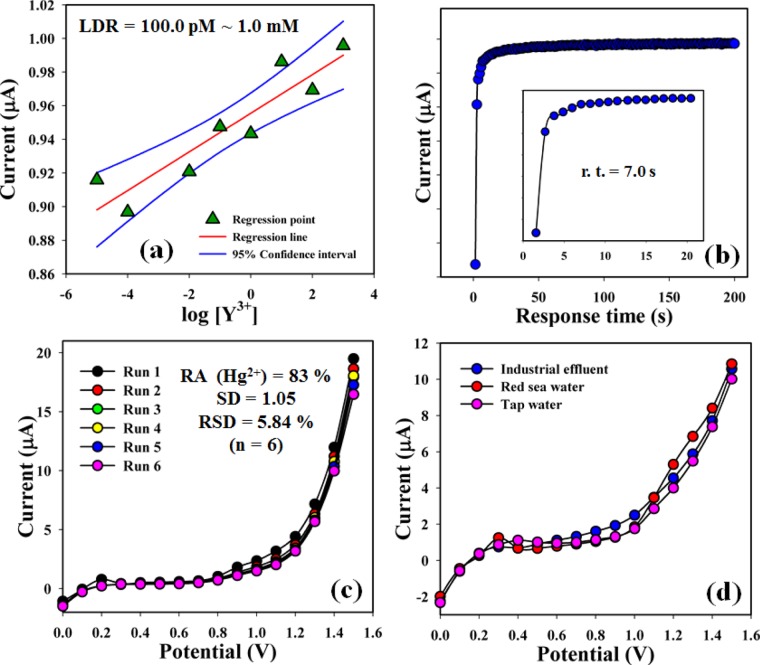

The current signals of the bare GCE, nafion-coated GCE, and 3-NBBSH-coated GCE were investigated, and the results are presented in Figure 4a. The differences in the current responses among the bare, nafion-coated and 3-NBBSH-coated GCEs are investigated. The current signal is increased in the case of the coated electrode compared to that of the bare GCE and nafion-coated GCE. The current signals without Hg2+ (black-dotted), and of nafion-Hg2+ (red-dotted) and 3-NBBSH-Hg2+ (blue dotted) were also studied at 1.0 nM concentration and are presented in Figure 4b. An increase in current response was observed for the modified 3-NBBSH electrode with Hg2+ compared with that of other derivatives, due to the large surface area with better coverage in absorption and adsorption ability onto the 3-NBBSH surfaces toward the target metal ion, Hg2+. The nafion coating slightly blocks the surface of the GCE electrode. Therefore, current is slightly decreased with nafion binders in the presence of the analyte. But in the case of fabricated 3-NBBSH, the current is significantly increased due to the Hg2+ interaction with the functional groups of the compound. I–V responses of Hg2+ at different concentrations to the 3-NBBSH-modified electrode were examined with the indication of changes in current for the fabricated electrode as a function of Hg2+ concentration under room conditions. It is reported that the current responses increase gradually from lower to higher concentration of the target selective metal ion, Hg2+ [SD = 5.23, RSD = 19.55%, and n = 10 (Figure 4c)]. A large range of Hg2+ concentrations was employed from a lower to a higher potential (0.0 ∼ +1.5 V) to find the possible analytical detection limit. The linear calibration curve at +0.7 V was plotted in the Hg2+ concentration range of 100.0 pM ∼ 100.0 mM. The regression coefficient (R2 = 0.9980), sensitivity (949.0 pA μM–1 cm–2), and the limit of detection (LOD) (10.0 ± 1.0 pM) at S/N ∼3 were calculated from the calibration curve (Figure 4d). The linear dynamic range (LDR) (100.0 pM ∼ 1.0 mM) of the fabricated electrode was also calculated from the practical concentration deviation diagram (Figure 5a). The r.t. of Hg2+ toward the electrode was measured at 100.0 nM and was found to be 7.0 s (Figure 5b).

Figure 4.

I–V responses. (a) Bare GCE, nafion-coated GCE, and 3-NBBSH-coated nafion/GCE, (b) absence and presence of Hg2+ with different electrode modifications of synthesized compounds, (c) concentration variation, and (d) calibration curve at +0.7 V (range of target Hg2+ concentration = 100.0 pM ∼ 100.0 mM; pH = 7.0; potential range = 0.0 ∼ 1.5 V; technique: I–V).

Figure 5.

(a) Plot of LDR, (b) plot of r.t. of mercury cations at 100.0 nM (inset: expansion of 0–20 s), (c) repeatability study at 100.0 nM of Hg2+ [RA calculated at the calibration potential, +0.7 V], and (d) real-sample analysis (industrial effluent, red sea water, and tap water).

The sensing performance of the 3-NBBSH-coated electrode was examined up to 2 weeks for the study of the reproducibility as well as storage stability. For sensor repeatability, it was measured by a series of six successive readings in a similar concentration of Hg2+ (100.0 nM), which exhibited an excellent reproducible response with the 3-NBBSH electrode in identical systems (SD = 1.05, RSD = 5.84%, and n = 6). It was found that the I–V responses were not comprehensively changed after washing the fabricated 3-NBBSH electrode (Figure 5c) with buffer in each experiment. The sensitivity remained approximately the same as the original one, up to 2 weeks, and subsequently, the responses of the modified electrode decreased slowly. The responses of the 3-NBBSH sensor were considered with respect to storage time for the purpose of long-term storage stability. The storage ability of the 3-NBBSH electrode sensor was examined at the calibration potential (+0.7 V) under standard conditions. The repeatability (RA) toward Hg2+ was also found to be 83% of the preliminary response for several days (Figure 5c and Table S5). It was evidently reported that the fabricated sensor may be used without any significant loss of sensitivity up to a few weeks.

The analytical performances, for example, the sensitivity and LOD, of the fabricated 3-NBBSH/GCE are attributed to the outstanding absorption and adsorption aptitude, including elevated catalytic activity or interaction with functional groups and superior biocompatibility of 3-NBBSH. The expected sensitivity of the modified 3-NBBSH/GCE sensor is relatively higher and the LOD is comparatively lower with respect to earlier reported heavy metal ionic sensors based on different modified electrodes.29−35The 3-NBBSH/binder/GCE has provided a significantly favorable nanoenvironment for Hg2+ recognition with excellent sensitivity. The higher sensitivity of the NBBSH/GCE is provided by the higher electron communication and good interaction features with functional groups, which significantly increase the electron transfer between the active functional sites of 3-NBBSH and nafion/GCE. The NBBSH/GCE scheme is established as an easy and dependable method for the detection of poisonous heavy metal ions by the I–V method. A comparison of Hg2+ detection using different modified electrodes7,36−44 is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Determination of Hg2+ Using Different Modified Electrodesa.

| electrodes | methods | medium (M) | sensitivity | LOD (μg/L) | LDR (μg/L) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au–SPCE | SWASV | HCl (0.025) | 1.02 ± 0.07 | 1–100 | (7) | |

| Au–SPCE | SWASV | HCL (0.05) | 0.5 | 5–30 | (36) | |

| Au–SPCE | SWASV | HCl (0.05) | 1.1 ng/mL | 0.2–0.8 | (37) | |

| Au-ink-SPCE | SWASV | HCl (0.1) | 0.9 | 1–1000 | (38) | |

| SbF-CPE | SWASV | HCl (1) | 1.3 ppb | 10–100 | (39) | |

| AuF-CPE | SWASV | HNO3/KCl (0.05/0.02) | 50 ng/L | 0.2–50 | (40) | |

| Unmod-SPCE | DPASV | NaCl (0.1) | 2 ppm | 5–100 | (41) | |

| Chitosan-SPCE | DPASV | HCl/KCl (0.1) | 60 ng/L | 10–200 | (42) | |

| PAm-blue SPCE | DPASV | HCl (0.5) | 54.27 ± 3.28 | 54 | (43) | |

| Au(I)-AT-NTs/GCE | SWASV | HNO3 (0.1) | 0.5 nM | (44) | ||

| 3-NBBSH/GCE | I–V | PB (0.1) | 949.0 pA μM–1 cm–2 | 10.0 ± 1.0 pM | 100.0 pM ∼ 1.0 mM | this work |

SPCE, screen printed carbon electrode; SWASV, square-wave anodic stripping voltametry; SbF-CPE, antimony-coated carbon paste electrode; AuF-CPE, carbon paste electrode plated with a gold film; and DPASV, differential pulse anodic stripping voltametry.

Analysis of RS

RS, such as industrial effluent, red sea water, and tap water, were examined to validate the cationic sensors using the 3-NBBSH/GCE by the I–V system. A typical addition technique was used to determine the unknown concentration of Hg2+ in real environmental samples. A fixed amount (∼25.0 μL) of each original sample was analyzed in PB (10.0 mL, 100.0 mM) using the fabricated 3-NBBSH/GCE under room conditions. The results were found for the determination of Hg2+ in industrial effluent, red sea water, and tap water, which actually confirmed that the proposed I–V procedure is acceptable, dependable, and appropriate for analyzing RS (Figure 5d and Table 4).

Table 4. Real-Sample Analysis with the 3-NBBSH/GCE for Hg2+ Detectiona.

| measured

current (μA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS | R1 | R2 | R3 | average | measured conc. (μM) | SD (n = 3) |

| industrial effluent | 1.73 | 1.16 | 1.07 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 0.36 |

| red sea water | 1.11 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.19 |

| tap water | 1.26 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.23 |

R, reading; SD, standard deviation.

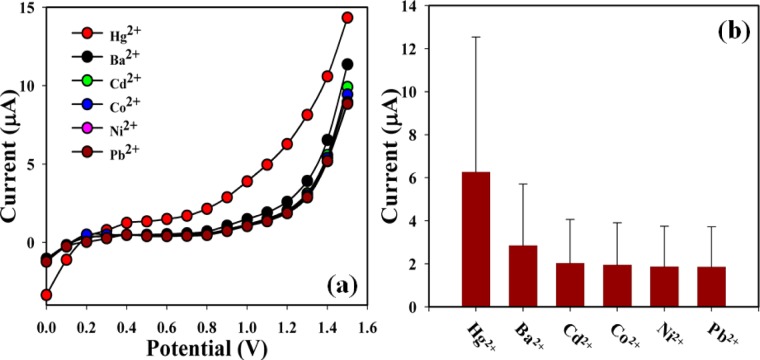

Interference Effect

Investigation of the interference effect is one of the significant approaches in analytical science, due to the ability to differentiate the interfering effects of different heavy toxic metal ions having similar cationic nature. Ba2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Pb2+ are generally used as interfering cations in an electrochemical Hg2+ sensor.44,45I–V responses on the 3-NBBSH/GCE toward the addition of Hg2+ and interfering heavy metal ions, for example, Ba2+, Cd2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Pb2+ (100.0 μM, and 25.0 μL) in PB (pH = 7.0) were examined. The effects of interfering cations on Hg2+ were studied at the calibrated potential (+0.7 V) and compared with the effect of Hg2+ (Figure 6 and Table 5). From the interference study, it is found that the 3-NBBSH/GCE does not exhibit any significant current response toward the other interfering heavy metal ions. Hence, the fabricated sensor is suitable for the detection of Hg2+ with excellent sensitivity. The interaction effect in the presence of Hg2+ with 3-NBBSH was also studied by ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), and the results are presented in the Supporting Information section (Figures S10 and S11). In the presence of Hg2+, λmax is shifted toward the higher wavelength due to the interaction of Hg2+ with the functional groups existing in the synthesized 3-NBBSH. The prepared 3-NBBSH sample was studied after digesting with standard chemicals [HNO3 (4.0 mL) + HCl (4.0 mL) + HClO4 (1.0 mL)] for the detection of Hg2+ by the ICP-OES conventional method and reasonable results were obtained (SD = 0.38, RSD = 0.57%, n = 3, and R2 = 0.9986), which are presented in the ESM section (Figure S11 and Table S6).

Figure 6.

Interference effect of other metal ions toward the proposed Hg2+ ionic sensor. (a) Comparative study in the presence of interfering cationic metal ions, (b) Bar-diagram presentation at +1.2 V with error limit [PB, pH = 7.0; amount: 25.0 μL; method: I–V; delay time = 1.0 s, and potential range: 0.0 ∼ +1.5 V].

Table 5. Interference Effect of Various Metal Ions with the 3-NBBSH/Nafion/GCEa.

| observed current (μA) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metal ions | R1 | R2 | R3 | average | interference effect (%) | SD (n = 3) | RSD (%) (n = 3) |

| Hg2+ | 1.85 | 0.96 | 2.27 | 1.69 | 100 | 0.67 | 39.50 |

| Ba2+ | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 34 | 0.06 | 11.15 |

| Cd2+ | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 28 | 0.02 | 4.17 |

| Co2+ | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 27 | 0.02 | 4.44 |

| Ni2+ | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 25 | 0.02 | 3.61 |

| Pb2+ | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 24 | 0.02 | 4.22 |

Interference effect of Hg2+ is considered to be 100%; R, reading; SD, standard deviation; and RSD, relative standard deviation.

Conclusions

Different derivatives of NBBSH compounds were synthesized, characterized, and applied to identify toxic heavy metallic ions using the I–V method. Methodical performances of the Hg2+ sensor using the NBBSH/GCE were evaluated by a reliable I–V technique with analytical parameters of LOD, sensitivity with short r.t., and reproducible aptitude. This approach has demonstrated higher selectivity and rapid detection of Hg2+ ion using the 3-NBBSH/nafion/GCE probe. Practically, a similar conception may be applied for the development of various heavy toxic metallic cationic sensors for monitoring other carcinogenic and hazardous cations in practical environmental monitoring. This new sensor can be introduced as an innovative system for the development of efficient cationic sensors for monitoring toxic metal ions in biological, environmental, and health care fields.

Experimental Section

Material and Methods

Chemicals of analytical grade, such as 2-nitrobenzaldehyde, 3-nitrobenzaldehyde, 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, benzenesulfonylhydrazine, AuCl3, Ba(NO3)2, CdSO4, Ce(NO3)2, Co(NO3)2, Cr(NO3)3, HgCl2, NiCl2, Pb(NO3)2, SbCl3, Y(NO3)3, ZnSO4, EtOH, MeOH, NaH2PO4, Na2HPO4, and nafion (5% ethanolic solution), were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich company and were used as received. A mother solution of heavy metal ion, Hg2+ (100.0 mM), was prepared from HgCl2. A Stuart scientific SMP3 (version 5.0) melting point apparatus (Bibby Scientific Limited, Staffordshire, U.K.) was used to record the melting point, and the reported melting point uncorrected. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on an AVANCE-III instrument (400 and 850 MHz, Bruker, Fallanden, Switzerland) at 300 K, and chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) with reference to the signal of residual solvent. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded neat on a Thermo scientific NICOLET iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Madison, WI). UV–vis study was carried out using an Evolution 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific). The I–V method was conducted to detect the heavy metal ion, Hg2+, at a selected point using the fabricated 3-NBBSH/GCE on a Keithley electrometer (6517A). Caution! Mercury is toxic. Only a small amount of this material can be used for the preparation of the required solution with care.

Synthesis of NBBSH Derivatives

(E)-N′-(2-Nitrobenzylidene)-benzenesulfonohydrazide (2-NBBSH, 3)

A mixture of 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (510.0 mg, 3.38 mmol, 1.26 equiv) and benzenesulfonylhydrazine (450.0 mg, 2.63 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in EtOH (10.0 mL) was stirred at room temperature (R.T.) for 3 h. It was filtered, and the obtained precipitate was washed with cold EtOH. The resultant product was crystallized from methanol to give the title compound 3 as a whitish crystal (325.0 mg, 72%). EF = C13H11N3O4S, MW = 305.51, EA = C: 51.14, H: 3.63, N: 13.76, O: 20.96, S: 10.50, mp = 161.7–167.6 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 12.01 (s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.03 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.95–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.82 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.71–762 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 147.81, 142.64, 138.85, 133.75, 133.24, 130.74, 129.36, 127.90, 127.87, 127.08, 125.44, 124.63, and 124.26. FTIR (neat) vmax: 3200, 1555, 1537, 1389, 1197, 1100, 945, 805, 800, 776, 738, 703, 600 cm–1. UV–vis spectroscopy: λmax = 272.0 nm.

3-NBBSH, 4

A combination of 3-nitrobenzaldehyde (504.7 mg, 3.32 mmol, 1.14 equiv) and benzenesulfonylhydrazine (502.7 mg, 2.92 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in EtOH (25 mL) was stirred at R.T. for 2 h. It was filtered, and the resultant white precipitate was washed with cold EtOH. The obtained product was crystallized from methanol and then re-crystallized from acetone and EtOAc (50:50) to give the title molecule 4 as a light yellow crystal (400.0 mg, 45%). EF = C13H11N3O4S, MW = 305.31, EA = C: 51.14, H: 3.63, N: 13.76, O: 20.96, S: 10.50, mp = 195.5–197.7 °C. 1H NMR (850 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 8.36–8.33 (m, 1H), 8.21 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (dt, J = 10.6, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (214 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 148.26, 144.98, 138.95, 135.49, 133.40, 132.81, 130.60, 129.51, 127.25, 124.52, and 121.17. FTIR (neat) vmax: 3155, 2890, 1530, 1480, 1325, 1185, 1065, 965, 905, 807, 770, 695, 590. UV–vis spectroscopy: λmax = 275.2 nm.

(E)-N′-(4-Nitrobenzylidene)-benzenesulfonohydrazide (4-NBBSH, 5)

A mixture of 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (505.0 mg, 3.32 mmol, 1.13 equiv) and benzenesulfonylhydrazine (506.0 mg, 2.94 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in EtOH (20 mL) was stirred at R.T. for 6 h, filtered, and the solution was kept in open air to evaporate the solvent. The resultant product was crystallized from EtOH to give the title compound 5 as a yellow crystal (225.0 mg, 22%). EF = C13H11N3O4S, MW = 305.31, EA = C: 51.14, H: 3.63, N: 13.76, O: 20.96, S: 10.50, mp = 177.5–182.9 °C. 1H NMR (850 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 8.25–8.22 (m, 2H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (214 MHz, DMSO-d6, δ): 148.01, 144.76, 139.85, 138.89, 133.45, 133.44, 129.53, 127.85, 127.26, and 124.18. FTIR (neat) vmax: 3195, 2897, 1600, 1520, 1480, 1365, 1198, 1079, 915, 845, 730, 698, 595. UV–vis spectroscopy: λmax = 314.8 nm.

Crystallography Study of NBBSH Derivatives

The three new sulfonohydrazides (3–5) were synthesized and crystallized from MeOH, acetone and EtOAc (50:50), and EtOH, respectively, at room temperature by a slow evaporation technique. Very beautiful, grainlike crystals were obtained in vials. The samples were screened under a microscope for selecting good crystals to mount on the instrument for data collection. The assembly used to mount samples consists of a glass fiber inserted into wax fixed onto a hollow copper tube supported by a magnetic base. Particular samples were glued over a glass needle and were mounted on an Agilent super nova (dual source) technologies diffractometer, equipped with microfocus Cu/Mo Kα radiation for data collection. The data collection was accomplished using the CrysAlisPro software at 296 K under Cu Kα radiation.46 The structures were determined and refined by full-matrix least-squares methods on F2 using the SHELXL-97 method with in-built WinGX. Nonhydrogen atoms were also refined anisotropically by full-matrix least-squares methods.47Figures 3–5 were generated through PLATON and ORTEP with in-built WinGX.48−50 All Caromatic–H hydrogen atoms were positioned geometrically and treated as riding atoms with C–H = 0.93 Å and Uiso (H) = 1.2 Ueq (O), and 1.2 Ueq (C). The N–H hydrogen atoms were located through a Fourier map and refined with N–H = 0.81(7), 0.82(3), and 0.83(2) Å, respectively, in molecules 3–5. Uiso (H) was set to 1.2 Ueq for N atoms in all molecules. The crystal data were deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, and the following deposition numbers have been assigned: 1444297, 1511320, and 1511321, which are known as the CCDC number, for molecules 3–5, respectively. Crystal data can be received free of charge on application to CCDC 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21 EZ, U.K. (Fax: (+44) 1223 336-033; e-mail: data_request@ccdc.cam. ac.uk).

Fabrication of GCE with NBBSH Compounds

NaH2PO4 (200.0 mM, 39.0 mL), Na2HPO4 (200.0 mM, 61.0 mL), and distilled water (100.0 mL) were used for the preparation of phosphate buffer, PB (200.0 mL, 100.0 mM, pH = 7.0). EtOH was used to disperse the NBBSH molecules onto a watch glass to make a slurry. The slurry of the dispersed compound was then deposited on the surface of the GCE and kept in air (2 h) for drying. After that, nafion (10.0 μL of 5% ethanolic solution was dropped onto the dried layer of GCE) was added with the deposited electrode and kept again in open air (1 h) for complete drying to form a uniform film. The fabricated GCE and a platinum (Pt) wire were used as the working and counter electrodes, respectively, to investigate the I–V signals (Scheme 2).

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Center of Excellence for Advanced Materials Research (CEAMR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. CEAMR-SG-3-438.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00359.

Spectroscopic analysis of the synthesized NBBSH molecules (Figures S1–S3); 3-NBBSH, 4 (Figures S4–S6); 4-NBBSH, 5 (Figures S7–S9); bond lengths of 2-NBBSH (3) (Table S1); bond angles of 2-NBBSH (3) (Table S2); bond lengths of 3-NBBSH and 4-NBBSH (Table S3); bond angles of 3-NBBSH and 4-NBBSH (Table S4); repeatability study of the 3-NBBSH-modified sensor toward Hg2+ (Table S5); detection of Hg2+ by UV–vis spectroscopy (Figure S10); detection of Hg2+ by ICP-OES (Figure S11); ICP-OES study with a 3-NBBSH-Hg2+ sample (Table S6) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Mosa A. I.; Emara A. A.; Yousef J. M.; Saddiq A. A. Novel transition metal complexes of 4-hydroxy-coumarin-3-thiocarbohydrazone: Pharmacodynamic of Co(III) on rats and antimicrobial activity. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2011, 81, 35–43. 10.1016/j.saa.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzumi S. New development of photoinduced electron-transfer catalytic system. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 981–991. 10.1351/pac200779060981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. B.; Wang Z.; Xing H.; Xiang Y.; Lu Y. Catalytic and molecular beacons for amplified detection of metal ions and organic molecules with high sensitivity. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 5005–5011. 10.1021/ac1009047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roztocki K.; Matoga D.; Szklarzewicz J. Copper (II) complexes with acetone picolinoyl hydrazones: Crystallographic insight into metalloligand formation. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2015, 57, 22–25. 10.1016/j.inoche.2015.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique M.; Saeed A. B.; Ahmed S.; Dogar N. A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of hydrazide based Sulphonamides. J. Sci. Innovat. Res. 2013, 2, 627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M. N.; Rahman M. M.; Asiri A. M.; Sobahi T. R.; Yu S. H. Development of Hg2+ sensor based on N′-[1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene] benzenesulphonohydrazide (PEBSH) fabricated silver electrode for environmental remediation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 81275–81281. 10.1039/C5RA09399F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somé I. T.; Sakira A. K.; Mertens D.; Ronkart S. N.; Kauffmann J.-M. Determination of groundwater mercury (II) content using a disposable gold modified screen printed carbon electrode. Talanta 2016, 152, 335–340. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C.; Duan Y.; Wu C.-Y.; Zhou Q.; She M.; Yao T.; Zhang J. Mercury removal and synergistic capture of SO2/NO by ammonium halides modified risk husk char. Fuel 2016, 172, 160–169. 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.12.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna M. V. B.; Chandrasekaran K.; Karunasagar D. A simple and rapid microwave-assisted extraction method using polypropylene tubes for the determination of total mercury in environmental samples by flow injection chemical vapor generation inductively couples plasma mass spectrometry (FI-CVG-ICP-MS). Anal. Methods 2012, 4, 1401–1409. 10.1039/c2ay25084e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafawi A.; Ebdon L.; Foulkes M.; Stockwell P.; Corns W. Determination of total mercury in hydrocarbons and natural gas condensate by atomic fluorescence spectrometry. Analyst 1999, 124, 185–189. 10.1039/a809679a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrogues J. L.; Torres D. P.; Souza V. C. O.; Batista B. L.; Souza S. S.; Curtius A. J.; Barbosa F. Jr. Determination of total and inorganic mercury in whole blood by cold vapor inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (CV ICP-MS) with alkaline sample preparation. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2009, 24, 1414–1420. 10.1039/b910144f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman G. M. M.; Fahrenholz T.; Kingston H. M. S. Application of speciated isotope dilution mass spectrometry to evaluate methods for effectiveness, recoveries, and quantification of mercury species transformations in human hair. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2009, 24, 83–92. 10.1039/B805249B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; Peng M.; Zheng C.; Xu K.; Hou X. Application of flow injection-green chemical vapor generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry to ultrasensitive mercury speciation analysis of water and biological samples. Microchem. J. 2016, 127, 62–67. 10.1016/j.microc.2016.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Duan Y.; Zhou Q.; Zhu C.; She M.; Ding W. Adsorptive removal of gas-phase mercury by oxygen non-thermal plasma modified activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 294, 281–289. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj D. R.; Prasanth S.; Vineeshkumar T. V.; Sudarsanakumar C. Surface Plasmon Resonance based fiber optic sensor for mercury detection using gold nanoparticles PVA hybrid. Opt. Commun. 2016, 367, 102–107. 10.1016/j.optcom.2016.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meelapsom R.; Jarujamrus P.; Amatatongchai M.; Chairam S.; Kulsing C.; Shen W. Chromatic analysis by monitoring unmodified silver nanoparticles reduction on double layer microfluidic paper-based analytical devices for selective and sensitive determination of mercury (II). Talanta 2016, 155, 193–201. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. J.; Do H. Determination of inorganic and total mercury in marine biological samples by cold vapor generation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry after tetramethylammonium hydroxide digestion. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2008, 23, 997–1002. 10.1039/b805307n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.-H.; Yin Y.-G.; He B.; Shi J.-B.; Liu J.-F.; Jiang G.-B. L-cysteine-induced degradation of organic mercury as a novel interface in the HPLC-CV-AFS hyphenated system for speciation of mercury. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2010, 25, 810–814. 10.1039/b924291k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oriero D. A.; Gyan I. O.; Bolshaw B. W.; Cheng I. F.; Aston D. E. Electrospun biocatalutic hybrid silica-PVA-tyrosinase fiber mats for electrochemical detection of phenols. Microchem. J. 2015, 118, 166–175. 10.1016/j.microc.2014.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arecchi A.; Scampicchio M.; Drusch S.; Mannino S. Nanofibrous membrane based tyrosinases-biosensor for the detection of phenolic compounds. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 659, 133–136. 10.1016/j.aca.2009.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel D. W.; LeBlanc G.; Meschievitz M. E.; Cliffel D. E. Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 685–707. 10.1021/ac202878q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen N. J.; Halsall H. B.; Heineman W. R. Electrochemical biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1747–1763. 10.1039/b714449k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusnita J.; Ali H. M.; Puvaneswary S.; Robinson W. T.; Ng S. W. N′-(2-Hydroxy-5-nitobenzylidene)-benzenesulphonohydrazide. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2008, 64, o1583. 10.1107/S1600536808022691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M. N.; Sahin O.; Zia-ur-Rehman M.; Khan I. U.; Asiri A. M.; Rafique H. M. 4-Hydroxy-2h-1,2-Benzothiazine-3-Carbohydrazide 1,1-Dioxide-Oxalohydrazide (1:1): X-Ray Structure And DFT Calculations. J. Struct. Chem. 2013, 54, 437–442. 10.1134/S0022476613020224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M. N.; Sahin O.; Zia-ur-Rehman M.; Shafiq M.; Khan I. U.; Asiri A. M.; Khan S. B.; Alamry K. A. Crystallographic Studies of Dehydration Phenomenon In Methyl 3-Hydroxy-2-Methyl-1,1,4-Trioxo-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-1λ6-Benzo[E][1,2]Thiazine-3-carboxylate. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2013, 43, 671–676. 10.1007/s10870-013-0471-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M. N.; Mahmood T.; Khan A. F.; Zia-Ur-Rehman M.; Asiri A. M.; Khan I. U.; Un-Nisa R.; Ayub K.; Mukhtar A.; Saeed M. T. Synthesis, crystal structure and spectroscopic properties of 1, 2-Benzothiazine derivatives: An experimental and DFT study. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2015, 34, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq M.; Khan I. U.; Zia-Ur-Rehman M.; Asghar M. N.; Asiri A. M.; Arshad M. N. Synthesis and Antioxidant Activity of a New Series of 2,1-Benzothiazine 2,2-Dioxide Hydrazine Derivatives. Asian J. Chem. 2012, 24, 4799–4803. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J.; Davis R. E.; Shimoni L.; Chang N.-L. Hydrogen-bond pattern functionality and graph sets. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. 10.1002/anie.199515551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A.; Asiri A. M.; Khan A. A. P.; Rub M. A.; Azum N.; Rahman M. M.; Khan S. B.; Alamry K. A.; Ghani S. A. Sol-gel synthesis and characterization of conducting polythiophene/tin phosphate nano tetrapod composite cation-exchanger and its application as Hg(II) selective membrane electrode. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2013, 65, 160–169. 10.1007/s10971-012-2920-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen D.; Deng L.; Guo S.; Dong S. Self-powered sensor for trace Hg2+ detection. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 3968–3972. 10.1021/ac2001884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad M. N.; Tahir S. A.; Rahman M. M.; Asiri A. M.; Marwany H. M.; Awual M. R. Fabrication of cadmium ionic sensor based on (E)-4-Methyl-N′-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)benzenesulphonohydrazide (MPEBSH) by electrochemical approach. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 827, 49–55. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2016.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.; Thundat T. G.; Brown G. M.; Ji H. F. Detection of Hg2+ using microcantilever sensors. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 3611–3615. 10.1021/ac0255781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. A. P.; Khan A.; Rahman M. M.; Asiri A. M.; Oves M. Lead sensors development and antimicrobial activities based on graphene oxide/carbon nanotube/poly(O-toluidine) nanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 198–205. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Huang W.; Lin Z.; Duan C.; He C.; Wu S.; Wang D. Highly sensitive multiresponsive chemosensor for selective detection of Hg2+ in natural water and different monitoring environments. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 7190–7201. 10.1021/ic8004344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awual M. R.; Hasan M. M.; Eldesoky G. E.; Khaleque M. A.; Rahman M. M.; Naushad M. Facile mercury detection and removal from aqueous media involving ligand impregnated conjugate nanomaterials. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 290, 243–251. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Tian B. Screen-printed electrodes for stripping measurements of trace mercury. Anal. Chim. Acta 1993, 274, 1–6. 10.1016/0003-2670(93)80599-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnalte E.; Sanchez C. M.; Gill E. P. Determination of mercury in ambient water samples by anodic stripping voltametry on screen-printed gold electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 689, 60–64. 10.1016/j.aca.2011.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meucci V.; Laschi S.; Minunni M.; Pretti C.; Intorre L.; Soldani G.; Mascini M. An optimized digestion method coupled to electrochemical sensor for the determination of Cd, Cu, Pb and Hg in fish by square wave anodic stripping voltametry. Talanta 2009, 77, 1143–1148. 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi A. M.; Vytras K. Stripping voltametric determination of mercury (II) at antimony-coated carbon paste electrode. Talanta 2011, 85, 2700–2702. 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svancara I.; Matousek M.; Sikora E.; Schachl K.; Kalcher K.; Vytras K. Carbon paste electrodes plated with a gold film for the voltametric determination of mercury (II). Electroanalysis 1997, 9, 827–833. 10.1002/elan.1140091105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christidis K.; Robertson P.; Gow K.; Pollard P. On site monitoring and cartographical mapping of heavy metals. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 489–499. 10.1080/10739140600805916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled E.; Hassan H. N. A.; Habib I. H. I.; Metelka R. Chitosan modified screen printed carbon electrode for sensitive analysis of heavy metals. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2010, 5, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Somerset V.; Leaner J.; Mason R.; Iwuoha E.; Morrin A. Detremination of inorganic mercury using a polyaniline and polyaniline-methylene blue coated screen printed carbon electrode. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2010, 90, 671–685. 10.1080/03067310902962536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W.; Zhang H.; He S.; Tang D.; Fang S.; Huang Y.; Du C.; Zhang Y.; Zhang W. A novel electrochemical sensor based on nafion-stabilized Au(I)-alkanethiolate nanotubes modified glassy csrbon electrode for the detection of Hg2+. Anal. Methods 2014, 6, 4988–4990. 10.1039/c4ay00640b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Ma C.; He L.; Zhu S.; Hao X.; Xie W.; Zhang W.; Zhang Y. Ultrafast synthesis of Au(I)-dodecanthiolate nanotubes for advanced Hg2+ sensor electrodes. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 601–905. 10.1186/1556-276X-9-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CrysAlisPRO, revision 5.2; Agilent Technologies: Yarnton, England, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek A. L.PLATON, a Multipurpose Crystallographic Tool; Utrecht University: Utrecht, 2005.

- Farrugia L. J. WinGX suite for small-molecule single-crystal crystallography. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 837–838. 10.1107/S0021889899006020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia L. J. WinGX and ORTEP for windows: an update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.