Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a pruritic or painful dermatologic disease characterized by xerosis and eczema lesions. The symptoms/signs of AD can significantly impact patients' health-related quality of life (HRQoL). This study aimed to qualitatively explore the adult and adolescent experience of AD. A targeted literature review and qualitative concept elicitation interviews with clinicians (n = 5), adult AD patients (n = 28), and adolescent AD patients (n = 20) were conducted to elicit AD signs/symptoms and HRQoL impacts experienced. Verbatim transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis. Twenty-nine symptoms/signs of AD were reported, including pruritus, pain, erythema, and xerosis. Atopic dermatitis symptoms/signs were reported to substantially impact HRQoL. Scratching was reported to influence the experience of symptoms and HRQoL impacts. Four proximal impacts (including discomfort and sleep disturbance) were reported. Ten domains of distal impact were reported, including impacts on psychological and social functioning and activities of daily living. A conceptual model was developed to summarize these findings. This study highlights the range of symptoms and HRQoL impacts experienced by adults and adolescents with AD. To our knowledge, this study was first to explore the lived experience of AD in both adult and adolescent patients, providing valuable insight into the relatively unexplored adolescent experience of AD.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a relapsing, chronic inflammatory dermatological disease that is primarily characterized by itch, pain, and eczematous lesions, including erythema, xerosis, scaling, lichenification, and fissuring.1–3 The most commonly affected areas include the flexural surfaces of the extremities, anterior neck, hands, feet, and around the eyes.4,5 Atopic dermatitis symptoms can significantly impact patients' health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and affect physical, emotional, psychological, and social well-being (including sleep problems, irritability, stress, stigmatization, and social isolation).6–10

There is limited literature documenting the qualitative patient experience of AD, particularly in adolescent populations, and this research sought to explore and document in-depth both the adult and adolescent experience of AD and the associated impact on domains of HRQoL. Findings were used to develop a conceptual model to reflect the patient experience of AD.

METHODS

The following 5 different research activities were performed: a review of the published literature and qualitative interviews with clinical experts, 2 samples of adult AD patients, and 1 sample of adolescent AD patients.

Literature Review

A targeted, structured literature search was conducted in electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO) within the OVID SP platform to identify relevant articles. A search strategy (Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/DER/A23) was developed to capture articles reporting qualitative research focused on the signs (observable findings) and symptoms (subjective perceptions) and impacts of AD. A supplementary search was conducted in Google Scholar to ensure that all key/recently published articles were captured. Findings informed the development of a preliminary conceptual model detailing AD symptoms/signs and HRQoL impacts.

Qualitative Interviews With Clinical Experts

Qualitative, semistructured telephone interviews were conducted with 5 dermatologists specializing in AD from the United States (n = 4) and France (n = 1). Interviews lasted 90 minutes during which the dermatologists summarized the characteristics of adult AD, including key symptoms/signs. Clinical experts also gave their perspective on the impact of AD on adult HRQoL and gave input into a preliminary conceptual model. The conceptual model was updated after clinical expert interviews.

Qualitative Interviews With AD Patients

Three sets of in-depth, semistructured, concept elicitation interviews were conducted to explore AD signs/symptoms and HRQoL impacts in adult and adolescent patients in the United States.11,12 Study 1 included 18 adults (age ≥18), study 2 included 10 adults (aged ≥18 years), and study 3 included 20 adolescents (aged 12–17 years). Semistructured interview guides (Appendix B, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/DER/A24) were developed, which started with broad, open-ended questions designed to encourage patients to spontaneously describe their AD experiences. Concepts of interest were then explored further, through direct questioning. Concepts elicited during interviews were used to update the preliminary conceptual model. All interviews were conducted by trained qualitative interviewers and audio recorded. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before any study-related activities. Ethical approval for all interviews was provided by a central ethics committee (Copernicus IRB and Schulman IRB).

Study 1: Adult Interviews (n = 18)

Telephone interviews (75 minutes) were conducted in 3 rounds (6 participants per round). Patients were recruited via online poll, and eligible patients had a self-reported diagnosis of AD for more than 1 year, AD affecting 15% or more of body surface area (BSA), and 3 or more of the following: itch; rash inside/on the elbow, below the kneecap, on the back, on the knee, or on the face; rash that mostly/completely disappears and then returns; and a diagnosis or family history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, or AD.

Study 2: Supplementary Adult Interviews (n = 10)

Face-to-face interviews were conducted. Patients were referred by practicing clinicians who confirmed AD diagnosis. Eligible patients had to be diagnosed for more than 1 year, have an Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score of 2 or higher, and AD affecting 10% or more BSA. Quotas were used to ensure clinical/demographic diversity.

Study 3: Adolescent Interviews (n = 20)

Face-to-face interviews (30 minutes) were conducted. Patients were referred by practicing clinicians who confirmed AD diagnosis. Eligible patients had to be diagnosed for more than 1 year and have an EASI score of 1.1 or higher and AD affecting 2% or more BSA. Quotas were used to ensure clinical/demographic diversity.

Qualitative Analysis

Interview audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymized. Thematic analysis of transcripts was performed using data analysis software, ATLAS.ti (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany).1 Each transcript was assessed, coded, and analyzed by at least 2 researchers and reviewed by the study lead, to ensure consistency.13

Conceptual saturation was defined as the point at which no new “concept-relevant” information emerged from collection/analysis of further transcripts. Saturation was evaluated by comparing the concepts that emerged from 3 sets of transcripts. Saturation was defined to have been achieved if no new concepts emerged in the third set of interviews.14 An iterative approach was taken to incorporate results from the literature review, interviews with clinical experts, and AD patients into the development of the conceptual model.

RESULTS

Literature Review

The database searches generated a pool of 112 articles. After screening of titles and abstracts, 27 articles were selected for full review (14 quantitative, 10 qualitative, 2 mixed methods, 1 review article). Nineteen signs/symptoms were identified. Pruritus (itch) was most frequently reported (n = 11 articles), followed by painful skin (n = 9). Health-related quality of life impacts were grouped into proximal (a direct result of AD signs/symptoms) and distal (wider impact of AD) impacts. Nine articles described the proximal impact of AD on sleep and bodily/physical discomfort. Distal HRQoL impacts included psychological impacts (n = 22), impact on relationships (n = 18), limitations in daily activity (n = 14), skin-related health perceptions (n = 14), impact on work (n = 14), limitations of social activities (n = 11), and impact on sexual relationships (n = 11). More detailed findings can be found in Appendix C (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/DER/A25).

Patient and Clinical Expert Interviews

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

All clinical experts were well established in the field of dermatology with years of practice ranging from 8 to 52 years.

The adult patient sample (n = 28 patients) included a broad age range (27–75 years old). Approximately two-thirds were female (n = 19, 67.9%). Further demographic/clinical characteristics were collected only for study 2 (n = 10 patients). Of these, 70% were non-Hispanic white, 20% black/African American, and 10% Hispanic/Latino. Body surface area affected by AD ranged from 10% to more than 50%, and EASI ranged from 5.5 (mild) to 23.3 (severe), with a mean of 11.91 (mild, n = 5; moderate, n = 3; severe, n = 2).15 For the adolescent sample (n = 20), 55% were nonwhite, and 60% were female. Body surface area affected ranged from 2% to more than 49%, and EASI varied from 2.4 (mild) to 25.6 (severe), with a mean of 9.5 (mild, n = 4; moderate, n = 9; severe, n = 7). Although the adult sample could have benefited from a more diverse race/ethnicity profile, both samples were deemed to be representative of the wider population.

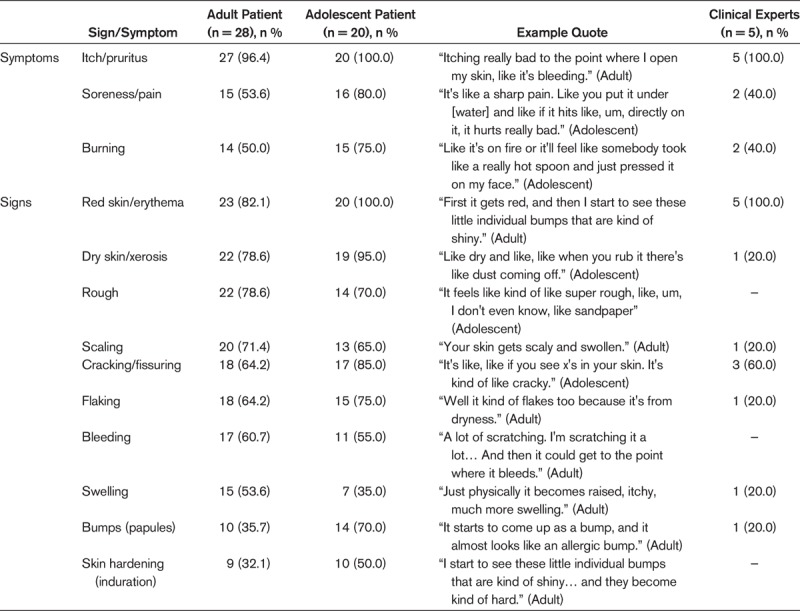

Signs and Symptoms

Twenty-seven signs/symptoms were identified from the interviews with adults, adolescents, and dermatologists; the most frequently reported are summarized in Table 1, and all reported signs/symptoms are presented in Figure 1. Consistent with the literature, itch was the most frequently reported AD sign/symptom, reported spontaneously by most adult (n = 26/27 [96.2%]) and all adolescent (n = 20/20 [100%]) patients. Soreness/pain was the next most frequently reported symptom (n = 15/28 adults [53.6%]; n = 16/20 adolescents [80%]). Redness, dryness, rough skin, and rash were all signs experienced by more than 70% of adult and adolescent patients.

TABLE 1.

Counts of Most Frequently Reported Signs/Symptoms and Example Quotes Elicited by Clinical Experts (n = 5) and Adult (n = 28) and Adolescent (n = 20) Patients With AD Through Qualitative Interviews

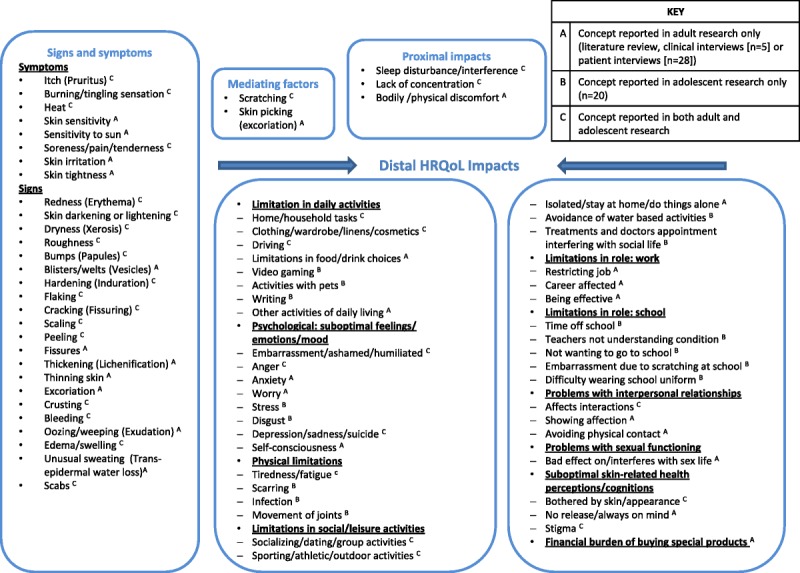

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of adult and adolescent AD.

Cracking, pain, burning, flaking, and bumps on the skin were reported by more than 70% of adolescents, but a smaller proportion of adults. In addition, more adolescents reported to experience skin peeling, scabbing, skin hardening, and hot/warm skin than adult participants. Conversely, scaling was reported by more than 70% of adults, but a smaller proportion of adolescents. Adults reported a number of symptoms that were not reported by any adolescents, namely, skin sensitivity, sensitivity to sun, thickening, tightening, crusting, oozing/weeping, blisters, fissures/lesions, and skin thinning. All but one of these symptoms (skin thinning, which is commonly recognized as an adverse effect of topical steroids) were reported in the literature.

Results from clinical expert interviews confirmed patient findings. Pruritus and erythema were reported by all 5 dermatologists. Patients did, however, report a number of symptoms that were not reported by experts, including roughness, which was reported by more than 70% of the patient sample.

Conceptual saturation of sign/symptom concepts was achieved in adult and adolescent samples, indicating that no further interviews were necessary.

Signs/symptoms reported were generally described to be experienced in “flare-ups” by both patients and dermatologists. The frequency/severity of flare-ups varied between and within patients. Itching was frequently reported to occur together with many other symptoms, particularly redness and dryness. Dryness, flaking, redness, and skin bumps were reported to frequently co-occur. Common triggers/exacerbating factors included the following: scratching, fabrics, topical cosmetics, sweat, water contact, extremes of weather, and stress. The most commonly reported location of signs/symptoms on the body was the flexural regions of the limbs, eyelids, hands, face, and neck.

Impact on Domains of HRQoL

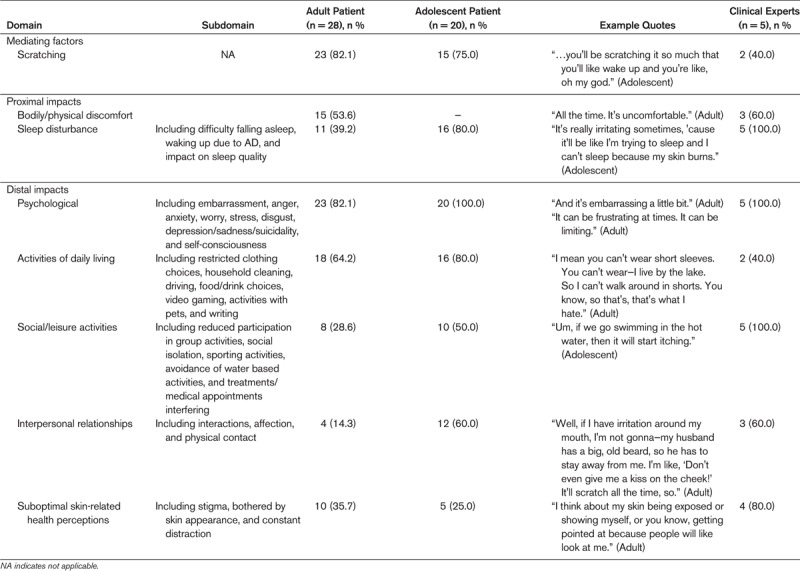

Health-related quality of life concepts reported by patients and clinical experts in the interviews were grouped into proximal and distal HRQoL impacts. The most frequently reported are summarized in Table 2, and all reported impacts are presented in Figure 1.

TABLE 2.

Counts of Most Frequently Reported Impacts on HRQoL and Example Quotes Elicited by Clinical Experts (n = 5) and Adult (n = 28) and Adolescent (n = 20) Patients With AD Through Qualitative Interviews

Mediating Factors and Proximal Impacts. Scratching was reported to be a mediating factor of AD (n = 20/28 adults [71.4%]; n = 15/20 adolescents [75%]), with patients explaining that scratching would moderate the experience of symptoms, such as itch and pain, and the proximal/distal HRQoL impacts experienced as a result of AD. Bodily/physical discomfort was reported only by adults (n = 15/28 [53.6%]), whereas sleep disturbance was the most frequently reported proximal impact for adolescents (n = 16/20 [80%]) but was reported by a smaller proportion of adults (n = 11/28 [39.2%]). However, adults reported to experience tiredness/fatigue more frequently than adolescents (n = 7/28 adults [25%]; n = 4/20 adolescents [20%]). Impact on concentration was reported more commonly in adolescents (n = 7/20 [35%]) than adults (n = 1/28 [3.5%]).

The expert dermatologists highlighted a number of the same proximal impacts and mediating factors as patients, including sleep disturbance (n = 5/5 [100%]), discomfort (n = 3/5 [60%]), and scratching (n = 2/5 [40%]). The clinical experts did not report any impact on concentration or fatigue but did report skin picking as a mediating factor of AD (n = 2/5 [40%]) that was not reported by patients.

Distal Impacts. Adult and adolescent patients reported a range of distal HRQoL impacts associated with AD. Some similarities were demonstrated between adults and adolescents. Psychological impact was most frequently reported for both adults and adolescents (n = 23/28 adults [82.1%]; n = 20/20 adolescents [100%]). Both populations reported experiencing embarrassment about their skin, frustration, and sadness. Adults also reported experiencing anxiety, worry, and self-consciousness about their skin, whereas adolescents reported stress and disgust at their skin. Both populations (n = 10/28 adults [35.7%]; n = 5/20 adolescents [25%]) reported experiencing stigma associated with AD and were bothered by the appearance of their skin.

Both adults and adolescents also reported experiencing limitations in their daily activities because of AD (n = 18/28 adults [64.3%]; n = 16/20 adolescents [80%]). This included impacts on driving due to distraction by symptoms, impacts on household tasks because water/cleaning chemicals exacerbated AD, and impacts on clothing/cosmetic choices. Only adults reported limitations in their food/drink choices, because of perceptions that certain foods (eg, dairy) could exacerbate AD. Adolescents reported limitations playing video games and writing due to AD affecting dexterity and limitations playing with pets due to pet hair/fur exacerbating AD.

Impacts on social activities were frequently reported by adolescents and also reported by adults (n = 8/28 adults [28.5%]; n = 10/20 adolescents [50%]) to include socializing, group activities, dating, and vacations. Sporting activities/swimming were also affected because of water/sweat worsening AD, which was more frequently reported by adolescents. Adults described social isolation, whereas adolescents reported disruption to their social life as a result of frequent treatment application and medical appointments.

Both populations described AD affecting family relationships and friendships with adolescents reporting these concepts more frequently than adults (n = 4/28 adults [14.2%]; n = 12/20 adolescents [60%]). Adults also highlighted impacts on their romantic relationships and sex life including avoidance of showing affection or physical contact.

Adult patients reported impacts of AD on their work (n = 7/28 [25%]), including job restrictions, productivity, and career progression, and on their finances (n = 8/28 [28.6%]), including the costs of treatments and purchasing safe products. Adolescents described the impact of AD on school life (n = 12/20 [60%]), including absence, difficulties wearing school uniform, and not wanting to go to school.

Clinical experts largely confirmed the distal impacts reported by adolescent and adult patients and did not report any additional impacts. In line with patient findings, all 5 clinical experts emphasized the psychological and social impact of AD (n = 5/5 [100%]). Clinical experts did not highlight any financial and physical impacts.

Conceptual saturation analyses were only conducted for HRQoL impacts reported by adults, and saturation was achieved.

CONCEPTUAL MODEL

A conceptual model (Fig. 1) was developed based on findings from the literature review, patient, and clinical expert interviews. The model was designed to be a reflection of the most relevant and important AD signs/symptoms and impacts for patients. A key has been developed that details which concepts were elicited from adult research (literature review and interviews with clinical experts and adult patients) or from adolescent patients.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the patient experience of AD from a number of different perspectives and summarizes these findings in a conceptual model. This was a rigorous, in-depth qualitative study with a relatively large and diverse sample. Although conceptual models detailing pediatric AD and pruritus exist in the published literature, to our knowledge, this study was the first of its kind to explore the lived experience of AD in both adult and adolescent patients.16,17 In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to document the lived experience of AD in adolescents separately from other pediatric populations. Typically, research with adolescents (aged 11–17 years) is combined with that with younger pediatric patients (aged 0–10 years), for whom the HRQoL implications of AD are quite different.18,19 Published research and the findings reported here indicate that the disease experiences of younger and older pediatric populations can differ substantially as a result of hormonal, social, and emotional changes.20 Therefore, this study gives a unique insight into the adolescent experience of AD and provides evidence of concepts that might support meaningful end points in this population.

The qualitative literature review identified a number of symptoms and impacts associated with AD, which were subsequently used to develop a preliminary conceptual model. However, there was limited in-depth, published, qualitative research conducted specifically in adult and adolescent patients with AD, supporting the value of the prospective interviews.

The findings from the qualitative interviews indicate that adult and adolescent AD patients experience a wide range of impactful symptoms/signs, including itch, redness, dryness, roughness, scaling, and pain—consistent with the published qualitative literature.1,7,21–23 Key signs/symptoms reported by patients are also consistent with concepts assessed by the patient-reported outcome measures most commonly used in AD. For example, symptoms of itching, pain, and bleeding and impacts on sleep are included in both the Patient Orientated Eczema Measure and Skindex-29, and impacts on social life, emotional functioning, and daily activities are well documented in both the Skindex-29 and Dermatology Life Quality Index.1,9,24 Signs/symptoms were reported to be experienced in flare-ups, descriptions of which were consistent with the published qualitative literature.7,25 A number of symptoms/signs were reported to co-occur, emphasizing the broad spectrum and heterogeneity of signs/symptoms in AD.

Scratching was reported to be a mediating factor, affecting the experience of symptoms and HRQoL impacts of AD. Proximal impacts of discomfort and sleep disturbance and distal impacts on psychological functioning and activities of daily living were the most frequently reported, consistent with the published literature and conceptual model of pruritus, and are important contributions to the concept of AD.7,17,21–23,25–27 In particular, a number of published articles reference the clothing limitations and difficulties with housework experienced by AD patients, as well as the embarrassment and anger felt by these individuals about the appearance of their skin.22,23,25 This study also provided deeper insight into impacts on domains of HRQoL for both adults and adolescents, with concepts such as limitations in food and drink choice, tiredness/fatigue, difficulties exercising/playing sports, work restrictions, and the financial burden of treatments, emerging here with greater prominence than in the published literature.

A single conceptual model was developed for adolescents and adults because the elicited concepts were relatively consistent between the 2 populations. Observed HRQoL impact differences are unsurprising based on the differences in adult and adolescent lifestyle. Patients reported more symptom descriptors and HRQoL impacts than clinicians, perhaps highlighting issues that clinicians are less aware of. However, differences may reflect the small clinician sample size and those interviews being more focused on signs/symptoms.

Study Limitations

This study had a limited diversity of ethnicities in the adult patient sample, although there was a better range in adolescents. In addition, the patient sample and most clinicians were recruited from the United States; ideally, further research should confirm the cross-cultural relevance of findings. Finally, confounding factors, such as length of time with AD, the relapsing-remitting nature of AD, and the impact of AD treatments were not explored in detail in this study and could have influence on the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from this literature review and in-depth qualitative interviews with clinical experts and adult and adolescent patients supported development of a comprehensive conceptual model documenting the broad range AD signs/symptoms and impacts that are relevant from the patient perspective. The conceptual model can be used to aid understanding of the adult and adolescent patient experience of AD and can be a valuable tool for developing, planning, and evaluating relevant patient-reported outcome measures for clinical trials and practice. This study highlights the range of symptoms and HRQoL impacts experienced by adults and adolescents with AD. To our knowledge, this study was first to explore the lived experience of AD in both adult and adolescent patients, providing valuable insight into the relatively unexplored adolescent experience of AD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The work was sponsored and funded by MedImmune and LEO Pharma A/S. J.P. was an employee of ERT and later IQVIA, a consultancy paid by MedImmune and LEO Pharma A/S to conduct the study. L.G., C.T., and R.A. were employees of Adelphi Values, a consultancy paid by LEO Pharma A/S to conduct the study and develop the article. B.B., L.S.L., N.K., and J.H.-P. are employees of LEO Pharma. J.I.S., J.-F.S., E.S., and W.A. received payment as consultants for engagement in the research as clinical experts.

Institutional review board approval status was reviewed and approved by Schulman IRB (201504819) and Copernicus IRB (ADEI1-17-105 and ADEI1-17-534).

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.dermatitisjournal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients' perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004;140(12):1513–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol 2010;22(2):125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correale CE, Walker C, Murphy L, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 1999;60(4):1191–1198, 1209-1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tollefson MM, Bruckner AL. Atopic dermatitis: skin-directed management. Pediatrics 2014;134(6):e1735–e1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson W, Kapur S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin immunol 2011;7(Suppl 1):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akdis CA, Akdis M, Bieber T, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus Report. Allergy 2006;61(8):969–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amaral CS, March Mde F, Sant'Anna CC. Quality of life in children and teenagers with atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol 2012;87(5):717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buske-Kirschbaum A, Geiben A, Hellhammer D. Psychobiological aspects of atopic dermatitis: an overview. Psychother Psychosom 2001;70(1):6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19(3):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenna SP, Doward LC. Quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;8(3):228–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res 2010;19(8):1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26(5):363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instructions; CIa. Instructions for use. Available at: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/dermatology/quality-of-life/childrens-dermatology-life-quality-index-cdlqi/cdlqi-information-and-instructions/. Accessed January 20, 2018.

- 14.Glaser B, Strauss A. The constant comparative methods of qualitative analysis. In: Glaser BG, Strauss AL, eds. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategries for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2010:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 15.EASI Guidance. How to use EASI. 2014. Available at: http://www.homeforeczema.org/documents/easi-user-guide-dec-2016-v2.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2018.

- 16.Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, et al. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American children and their families. Pediatrics 2004;114(3):607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverberg JI, Kantor RW, Dalal P, et al. A comprehensive conceptual model of the experience of chronic itch in adults. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19(5):759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2016;9:159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campos ALB, Araújo FM, Santos MALD, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on the quality of life of pediatric patients and their guardians [in Portuguese]. Rev Paul Pediatr 2017;35(1):5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbuckle R, Abetz-Webb L. “Not just little adults”: qualitative methods to support the development of pediatric patient-reported outcomes. Patient 2013;6(3):143–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlay AY. Measures of the effect of adult severe atopic eczema on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1996;7(2):149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137(1):26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin 2017;35(3):303–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chren M-M. The Skindex instruments to measure the effects of skin disease on quality of life. Dermatol Clin 2012;30(2):231–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howells LM, Chalmers JR, Cowdell F, et al. ‘When it goes back to my normal I suppose’: a qualitative study using online focus groups to explore perceptions of ‘control’ among people with eczema and parents of children with eczema in the UK. BMJ Open 2017;7(11):e017731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magin P, Heading G, Adams J, et al. Sex and the skin: a qualitative study of patients with acne, psoriasis and atopic eczema. Psychol Health Med 2010;15(4):454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlay AY. Quality of life in atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45(1):S64–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.