Abstract

Effective and facile electrochemical oxidation of chemical fuels is pivotal for fuel cell applications. Herein, we report the electrocatalytic oxidation of hydrazine on a citrate-capped Au-TiO2-modified glassy carbon electrode, which follows two different oxidation paths. These two pathways of hydrazine oxidation are ascribed to occur on Au and the activated TiO2 surface of the Au-TiO2 hybrid electrocatalyst. This activation was achieved through molecular capping of the Au-TiO2 surface by citrate, which leads to favorable hydrazine oxidation with a lower Tafel slope compared to that of the clean surface of the respective materials, that is, Au and TiO2.

Introduction

Fuel cells, electrochemical energy conversion devices, play a vital role in overcoming the global energy crisis. Among the different types of fuel cells, direct electrochemical oxidation fuel cells (DEOFCs) render choices to employ various chemical fuels and usually demonstrate high efficiencies.1−3 The performance of DEOFCs depends significantly on the anode catalyst used for the oxidation of the chemical fuels. Therefore, design and synthesis of an effective and efficient anode catalyst are crucial to the performance of DEOFCs. Noble metals and their alloys are extensively used as catalysts in DEOFCs.4,5 However, the cost-ineffectiveness of noble metals is one of the main concerns that limits their use as catalysts in DEOFCs for practical applications. Thus, recent focus has been centered on designing the non-noble-metal catalysts, including transition metal oxides. To achieve a high performance or energy-efficient DEOFC, focus must be laid on the following major aspects:6,7 first, design of a smart and tailored catalyst with a low oxidation overpotential4,8 and, second, the nature of the fuels, the electrolyte, and the pH.9 An ideal fuel should have a wide availability, low cost, and low thermodynamic oxidation potential with a favorable reaction mechanism and produce eco-friendly byproducts upon oxidation.8 There are several reports on water electrolysis (water as fuel),10 direct methanol/ethanol oxidation,11,12 and hydrazine oxidation.13,14 The use of water as a fuel (water electrolysis) is attractive; however, water electrolysis suffers from complex kinetics of water oxidation at the anode surface, which controls the overall reaction. Therefore, researchers have also paid attention toward direct electrochemical oxidation of alcohols (methanol/ethanol).15 However, electro-oxidation of alcohols produces carbonaceous species, which poison the catalyst, leading to increased overpotentials.16 On the other hand, hydrazine is an attractive fuel, with several merits, as follows: (i) direct hydrazine fuel cell (DHFCs) generate environment-friendly products, such as N2 and H2O, which are neither greenhouse gases nor have toxicity, (ii) they exhibit a theoretical electromotive force of 1.56 V, which is higher than that of other liquid or H2–air fuel cells, and (iii) they produce high energies and power densities compared with hydrogen fuel cells.2,17 However, hydrazine is reported to be toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic.18−20 Its flashpoint and other risk factors can be avoided if suitable conditions are perceived.21 For example, anhydrous hydrazine has a lower flashpoint, which can be nullified upon diluting in aqueous solution. A <29% hydrazine aqueous solution does not show any flashpoint. Similarly, thermal ignition and other toxicities can be handled with suitable precautions. To overcome the aforementioned limitations associated with alcohol fuel cells, it is desirable to explore and design new hybrid catalysts with higher catalytic activities and reliabilities and utilize a fuel that does not produce harmful byproducts.

Despite the toxicity issue, hydrazine is still considered as an attractive liquid fuel for the aforementioned reasons. In DHFCs, the anode catalyst plays a crucial role in reducing the overpotential and increasing the oxidation current density and thereby in increasing the overall efficiency. Primarily, Pt- and Pd-based materials and their alloys have been used as anode catalysts in DHFCs.22−24 To reduce the use of these expensive noble metals, studies have been performed on making alloys or composites with non-noble metals,25 carbon-based materials,24,26 polymers,27,28 and oxides.29,30 Furthermore, non-noble metals and their alloys and complexes have been studied for hydrazine oxidation.17,31−33 However, there are only a few studies in which oxides have been used as the support material for the metal catalyst for electro-oxidation of hydrazine.23,34 The use of oxides as a support for the metal catalyst not only reduces the use of metals but also increases the electroactive surface area. The main challenges for DHFCs are to develop efficient electrocatalysts with a low hydrazine oxidation potential and high current density. Surface functionalization of nanomaterials is considered as an effective way to increase the electrocatalytic properties.35−38 In particular, upon suitable functionalization, Au nanoparticles (NPs) show improved CO2 and O2 reduction activities.37,38 On the other hand, TiO2 is known to be a stable oxide primarily studied in solar water splitting and photocatalysis, and its application in fuel cells has not been studied in depth. In the present work, TiO2 is used as a support material to a Au electrocatalyst for hydrazine oxidation and citrate is taken as a model molecule to functionalize the Au and TiO2 surfaces to improve the electrocatalytic activities. This is due to the fact that hydrazine is basic in nature and therefore citrate capping of the catalyst surface is expected to increase the active sites for hydrazine electro-oxidation through known acid–base adduct formation.

Results and Discussion

Surface Morphology of Au-TiO2 Nanocrystals (NCs)

Figure 1a shows a representative field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) image of Au-TiO2 NCs. The FESEM image shows gray particles assigned to TiO2 NCs with a size in the range of 70–100 nm across the diagonal, and finer bright Au NPs were found to be deposited at the edges of the TiO2 NCs. The size of the TiO2 NCs and Au NPs was further measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 1b shows a representative TEM image of hybrid Au-TiO2 NCs. The TiO2 NCs are found to be primarily cuboid with three different exposed facets, as discussed in detail earlier.39 Briefly, along [001], the top and bottom facets of the cuboids are {001}, the sides are {100}/{010}, and the eight top and bottom edges are {101} exposed facets. The size of the Au NPs varies in the range of 10–30 nm. TEM analysis also clearly reveals that the Au NPs were primarily deposited at the edges of the cuboid TiO2 NCs upon ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation. The UV light irradiation induced creation of electron and hole pairs in the faceted TiO2 NCs. The photoexcited electrons prefer to accumulate in excess on the {101} facets of cuboid TiO2 NCs due to their reductive nature.39−41 These photoelectrons on the {101} facets facilitate reduction of noble metal ions and their nucleation as metal NPs on the same crystal facets.42 The notion of charge carrier separation is therefore utilized here to deposit the Au NPs onto the reductive {101} facets of TiO2 NCs by UV light irradiation.41 However, fewer Au NPs were found to accumulate on the surface (not at edges) of distorted and spherical TiO2 NCs. The citrate capped on the TiO2 surfaces can also induce some of the Au NPs to be deposited/stabilized on its surface.

Figure 1.

(a) FESEM image of Au-TiO2 NCs. (b) The TEM image of Au-TiO2 NCs reveals selective photodeposition of Au NPs at the edges of the TiO2 NCs.

Surface Composition of Au-TiO2 NCs

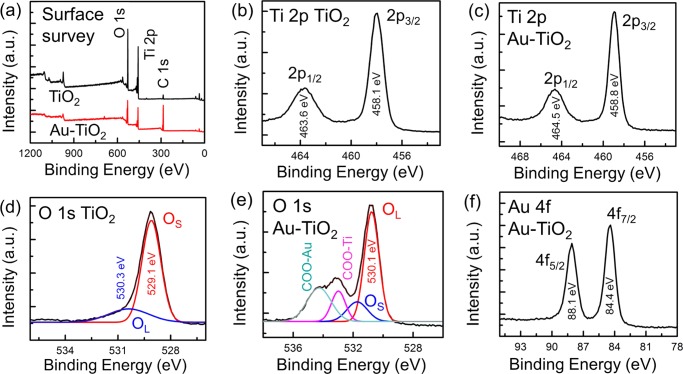

The surface composition of the Au-TiO2 NCs was analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The photoelectron peaks were calibrated with respect to the C 1s binding energy (BE) at 284.5 eV. Figure 2a shows the surface survey XPS spectra of bare cuboid TiO2 NCs and Au-TiO2 NCs. The survey spectra reveal a much stronger C 1s feature for Au-TiO2 NCs than that for bare TiO2 NCs, indicating citrate capping on the former. The features at lower binding energies (20–65 eV) in both the samples (not marked in Figure 2a) are assigned to O 2s, Ti 3p, and Ti 3s (Figure S1, Supporting Information (SI)). Figure 2b,c displays the Ti 2p region spectra of TiO2 NCs and Au-TiO2 NCs, respectively. The two major photoelectron peaks of bare TiO2 NCs at BEs of 458.1 and 463.6 eV correspond to Ti(IV) 2p3/2 and 2p1/2, respectively. The Ti 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 peaks are found to be shifted to 458.8 and 464.5 eV, respectively, for the citrate-capped Au-TiO2. The shift in BEs can be attributed to the change in the surface chemistry of TiO2 in the hybrid Au-TiO2 nanomaterial due to citrate capping. In addition, the deposition of Au NPs onto TiO2, as revealed by the FESEM and TEM analyses, could further facilitate such a shift in the BE. This is because of the fact that the EF of Au is known to be lower (−5.5 eV) than that of TiO2 (−4.4 eV).43−45 Therefore, electrons drift from TiO2 to Au in the case of Au-TiO2. This makes TiO2 slightly positively charged and thus Ti 2p peaks at higher BE values for the Au-TiO2 NCs. A marked shift in the BE is also observed for the O 1s of Au-TiO2 NCs as compared to that of bare TiO2 NCs, as shown in Figure 2d,e. The O 1s feature of bare TiO2 NCs (Figure 2d) can be deconvoluted into two peaks, a strong peak at 529.1 eV and a weak peak at 530.3 eV, which are due to the lattice oxygen (OL) and surface-adsorbed oxygenated species (OS), such as —OH and H2O, respectively. These two O 1s peaks are found to be shifted to 530.1 eV for OL and 531.7 eV for OS in the case of Au-TiO2 NCs (Figure 2e). In addition to the OS and OL peaks, the Au-TiO2 NCs exhibit two additional O 1s peaks centered at 532.9 and 534.3 eV, assigned to the surface-adsorbed citrate on the TiO2 surface and Au, respectively, as displayed in Figure 2e. These two peaks at 532.9 and 534.3 eV correspond to the Ti—OOC— (TiO2-citrate) and Au—OOC— (Au-citrate) bonding, respectively. It is expected that the metallic Au NPs were capped with more number of citrate groups than that on the TiO2 surface in the hybrid Au-TiO2 nanomaterial, which is in accord with the O 1s XPS intensity of the carboxylate group (Figure 2e). The photoelectron peaks of Au, that is, Au 4f7/2 and 4f5/2, were found to be located at 84.4 and 88.1 eV, respectively, indicating the metallic state of Au NPs in the hybrid Au-TiO2 sample.46,47

Figure 2.

(a) XPS surface survey of TiO2 NCs and Au-TiO2 NCs. (b) Ti 2p and (d) O 1s XPS region spectra of TiO2 NCs. (c) Ti 2p, (e) O 1s, and (f) Au 4f region XPS spectra of Au-TiO2 NCs.

Electrochemical Hydrazine Oxidation

The electrochemical behavior of hybrid Au-TiO2 NC catalysts was studied using a Bipotentiostat with a three-electrode system in a 0.1 M KOH solution for hydrazine oxidation. Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) were recorded by varying the molar concentration of hydrazine in the range of 0–3 mM in 0.1 M KOH, as shown in Figure 3a. To study concentration-dependent hydrazine oxidation, hydrazine was added gradually to the reaction mixture, stirred for 3 min, and then allowed to settle for another 5 min prior to each CV measurement. Figure 3a displays two anodic peaks in the potential range of −0.4 to +0.6 V versus those for a saturated calomel electrode (SCE), suggesting a two-step hydrazine oxidation process, unlike the single oxidation peak observed with a Au catalyst.29 The current densities of these two anodic peaks, denoted as Ipa 1 and Ipa 2, were found to increase with an increase in the hydrazine concentration. The onset potentials of Ipa 1 and Ipa 2 were observed at −0.35 and +0.2 V versus those of the SCE, respectively. The difference between the onset potential values of these two peaks was found to be quite large (0.55 V), indicating a two-step oxidation. In addition, Ipa 1 is sharper and increases significantly compared to the increase in Ipa 2, suggesting facile and favorable oxidation kinetics involved at Ipa 1 compared to that at Ipa 2. Without hydrazine, no peak (Ipa 1) was observed at ∼−0.2 V (vs that for the SCE). On the other hand, a minor peak (Ipa 2) at ∼+0.35 V versus that for the SCE can be attributed to the oxidation of the citrate capped on Au-TiO2. The CV plots also reveal a cathodic oxidation peak (Ipc 1) at +0.17 V versus that for the SCE, which is assumed to be due to the oxidation of the adsorbed species onto the catalyst surface that is formed during the anodic scan at Ipa 2 (discussed later). A lower onset potential for hydrazine electro-oxidation determines the utility of the electrocatalyst in practical applications. A detailed comparison of the hydrazine oxidation onset potential and peak potential of Ipa 1 to those of different metal and metal-modified catalysts is shown in Table 1. To understand the scan-rate dependence of different oxidation peaks over the hybrid Au-TiO2 nanomaterial, the scan rate was varied, keeping the hydrazine concentration and other experimental conditions fixed. Figure 3b displays the scan-rate dependence CVs for hydrazine oxidation (1 mM) in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte over Au-TiO2. The peak currents (Ipa 1 and Ipa 2) were found to vary linearly with the square root of the scan rate (Figure S2), suggesting a diffusion-controlled process.

Figure 3.

(a) CVs of Au-TiO2 NC catalysts obtained by varying the hydrazine concentration in the range of 0–3 mM at 50 mV/s. (b) CVs in a 1 mM hydrazine solution at different scan rates (ν = 10–200 mV/s). Ipa 1 is found to shift toward a higher overpotential region for hydrazine oxidation with an increase in concentration as well as with an increase in the scan rate, whereas the peak position of Ipa 2 is found to be independent of the hydrazine concentration and scan rate. All CVs were taken in a 0.1 M KOH solution with a given hydrazine concentration.

Table 1. Comparison of Ipa 1 to that from Recent Reports on Electrochemical Hydrazine Oxidation at Different Metal Catalyst Surfaces.

| catalyst | electrolyte | onset potential | peak potential | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd-rGO | 0.1 M PBS (pH 7) | –0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl | 0 V vs Ag/AgCl | (48) |

| Ni NPs | 0.1 M NaOH | 0 V vs RHE | 0.25 V vs RHE | (49) |

| Au-ZnO | 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) | –0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl | 0 V vs Ag/AgCl | (50) |

| Au NPs | 0.2 M PBS (pH 7) | –0.1 V vs Ag/AgCl | 0 V vs Ag/AgCl | (51) |

| Cu-rGO | 0.1 M KOH | 0 V vs SCE | 0.35 V vs SCE | (52) |

| Pd/MWCNT | buffer (pH 7.0) | –0.4 V vs SCE | –0.2 V vs SCE | (53) |

| Au-TiO2 | 0.1 M KOH | –0.35 V vs SCE | –0.17 V vs SCE | this work |

To understand the two-step hydrazine oxidation and to ensure the role of Au-TiO2 NCs, hydrazine (2 mM) oxidation was performed with bare TiO2 NCs and bare Au NPs, that is, without citrate capping (Figure S3). The absence of any oxidation/reduction peaks in the CV of the bare TiO2 NCs suggests that they have no role in hydrazine oxidation (Figure S3a). On the other hand, the CV of the Au NPs exhibits two anodic peaks at ∼−0.4 (Ipa 1) and +0.3 V (Ipa 2) versus those for the SCE. The peak potential of Ipa 1 shifts toward a more negative value, that is, −0.4 V, for the bare Au NPs as compared to −0.17 V versus that for the SCE for citrate-capped Au-TiO2 NCs (Figure 3a). The higher overpotential of Ipa 1 for Au-TiO2 is due to its lower conductivity than that of bare Au NPs. The Ipa 2 of bare Au NPs is due to the oxidation of Au(0) to Au(III), which gets reduced to Au(0) in the cathodic scan (Figure S3b).54 It is interesting to note that the Au NPs deposited on TiO2 did not show surface oxidation, that is, Au(0) to Au(III) in the potential range of −0.4 to 0.6 V versus that for the SCE. In contrast, despite the low overpotential for hydrazine oxidation, bare Au showed surface oxidation. XPS analysis revealed that citrate is bonded to both the Au and TiO2 surfaces in the hybrid Au-TiO2 nanomaterial. This citrate capping is attributed to the two-step hydrazine oxidation on hybrid Au-TiO2. To further ascertain the role of citrate capping, hydrazine electro-oxidation was carried out with citrate-capped TiO2 NCs (Figure S4) and citrate-capped Au NPs (Figure S5) separately under similar conditions. It was found that citrate-capped TiO2 shows negligible hydrazine oxidation, that is, Ipa 1 (in the range of −0.2 to 0 V vs that for the SCE). On the other hand, oxidation peaks (Ipa 2 and Ipc 1) in both the anodic and cathodic scans were observed in the range of +0.2 to +0.5 V versus those for the SCE (Figure S4) with citrate-capped TiO2 NCs. It is to be noted that there was no peak in this range for the bare TiO2 NCs (Figure S3a). This confirms the role of citrate capping on the Au-TiO2 NCs for Ipa 2 and Ipc 1 (Figure 3). The hydrazine attached to the citrate molecules is suggested to be oxidized at a positive potential of +0.35 V versus that of the SCE leaving aside carbonaceous impurities, which are oxidized during the cathodic scan, such as that observed during alcohol oxidation.16 On the other hand, citrate-capped Au NPs showed hydrazine oxidation at a higher overpotential of −0.24 V versus that of the SCE (Figure S5) compared to that of bare Au NPs at −0.4 V versus that of the SCE (Figure S3b).

The electro-oxidation mechanism on the citrate-capped Au-TiO2 NCs can thus be described as follows. The basic —NH2 moiety of hydrazine could easily attach to one of the free carboxylate groups of citrate capped either on the Au NP or TiO2 NC surface of the hybrid Au-TiO2, forming an acid–base adduct. This acid–base adduct formation leads to a superior hydrazine oxidation behavior of the citrate-capped Au-TiO2. The first anodic oxidation at a low overpotential (−0.35 V vs that of the SCE), that is, Ipa 1, is proposed to occur with the hydrazine molecule bonded to the citrate capped on the Au surface. Similarly, Ipa 2 is due to hydrazine oxidation through adduct formation with the free carboxylate group of citrate bonded to the TiO2 surface of Au-TiO2. A schematic diagram of these two different hydrazine oxidation pathways over Au-TiO2 is shown in Figure 4. At −0.35 V versus that of the SCE, the oxidation of hydrazine occurs on the Au surface, whereas at +0.2 V, hydrazine oxidation takes place on the TiO2 surface of the hybrid Au-TiO2 system. Therefore, the two different hydrazine oxidation peaks basically originate through adduct formation, with the free carboxylate group of citrate capped on the Au-TiO2 catalyst surface. The difference in the oxidation potentials is due to the difference in the support materials, that is, Au and TiO2 of Au-TiO2, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the two-step electrochemical hydrazine oxidation over citrate-capped Au-TiO2. Citrate is bonded with both the Au and TiO2 surfaces of Au-TiO2, as revealed by XPS analysis. Path I shows the oxidation of hydrazine at an onset potential of −0.35 V vs that of the SCE, which forms an adduct with the free carboxylate group of citrate bonded with the Au surface of Au-TiO2. Similarly, path II shows the oxidation of hydrazine with an onset potential +0.2 V vs that of the SCE, which forms an adduct with the free carboxylate group of citrate bonded with the TiO2 surface of Au-TiO2.

Furthermore, we compared the mass activity and corresponding Tafel slope of bare Au NPs and citrate-capped Au-TiO2, as shown in Figure 5. The peak current, Ipa 1, is estimated to be 1.45 times higher for Au-TiO2 than that for the bare Au NPs, as shown in Figure 5a. The higher peak current density, Ipa 1, of Au-TiO2 NCs is believed to be due to the facile interaction of the hydrazine molecule with the carboxylate group of citrate bonded with the Au NPs of Au-TiO2. This suggests minimization of the use of Au by formation of a suitable composite/hybrid for electrochemical hydrazine oxidation. Figure 5b displays the corresponding Tafel slopes of the different hydrazine oxidation peaks. Ipa 1 exhibits a smaller Tafel slope value (38 mV/dec) on Au-TiO2 NCs, suggesting enhanced hydrazine oxidation kinetics than that on bare Au NP surfaces (Tafel slope 126 mV/dec). However, Ipa 2 shows quite a high value of the Tafel slope (408 mV/dec), which is due to the semiconducting nature of TiO2; therefore, charge transportation is poor from the citrate-bonded hydrazine molecules through the TiO2 surface.

Figure 5.

(a) Mass activity of Au NPs and Au-TiO2 NCs in 3 mM hydrazine in a 0.1 M KOH solution at 50 mV/s. (b) Corresponding Tafel slopes of the Au NPs, and Ipa 1 and Ipa 2 of Au-TiO2, respectively. Ipa 1 exhibits quite a low Tafel slope for hydrazine oxidation, indicating favorable oxidation kinetics.

Conclusions

Au NPs are majorly deposited on the {101} reductive facets of TiO2 NCs through a simple UV light-assisted photoreduction of gold chloroauric acid. The surface of the Au-TiO2 NCs is found to be capped with citrate molecules, as confirmed from the XPS analysis. This citrate capping of Au-TiO2 played a key role in the facile and enhanced hydrazine electro-oxidation by formation of an acid–base adduct, that is, —NH2 (basic moiety, nucleophile) of hydrazine and the —COO– (acidic, electrophile) group of citrate. Therefore, such an acid–base adduct formation facilitates hydrazine oxidation. Citrate-capped Au NPs of Au-TiO2 show a smaller Tafel slope of 38 mV/dec that that of bare Au NPs (126 mV/dec), suggesting superior electrocatalytic activity of the former. In addition, citrate-capped TiO2 contributes toward hydrazine oxidation, with a Tafel slope of 408 mV/dec. The present study on the in situ functionalization of Au-TiO2 with citrate is demonstrated as a key idea, which could be broadened through molecular modification of nanomaterials to enhance their performance in the field of catalysis, sensing, and drug delivery.

Experimental Section

Chemicals

Titanium tetraisopropoxide (TTIP) [99.999%], tetrabutyl ammonium hydroxide (TBAH) [(C4H9)4NOH in 0.1 M aqueous], diethanolamine (DEA), tris-sodium citrate (Na3C6H5O7), isopropanol (C3H7OH), and hydrazine (N2H4) were purchased from Merck, India. Gold chloroauric acid (H2AuCl6·6H2O) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Synthesis

The faceted cuboid TiO2 NCs were synthesized as reported elsewhere.39 Briefly, 1.0 mL (3 mmol) of TTIP was added to 40 mL of TBAH and DEA at ∼5 °C. The resulting solution was hydrothermally treated at 225 °C for 48 h. The powder precipitate product was cuboid TiO2 NCs. The Au NPs were then deposited onto the bare TiO2 NC surface by UV light-assisted reduction of gold chloroauric acid. In a typical synthesis of hybrid Au-TiO2, 20 mg of the cuboid TiO2 NCs was dispersed in 50 mL of distilled water and irradiated under UV light for 3 h. Then, 10 mg of tris-sodium citrate was added to the reaction mixture, followed by the addition of gold chloroauric acid (15 mol %) in isopropanol. After the addition of gold chloroauric acid, the white solution slowly turned into deep violet, indicating nucleation of the Au NPs. The reaction mixture was further irradiated under UV for 30 min. The resultant red solution was then centrifuged to collect the solid product. The change in color toward red indicates an increase in the size of the Au NPs and/or aggregation. The solid product was washed several times with water and ethanol and finally dried at 60 °C.

Characterization

The surface morphology and microstructure of the products were examined using a Carl Zeiss SUPRA FESEM and TECNAI G2 (FEI) TEM operated at 200 kV. XPS was carried out on a PHI 5000 VersaProbe II Scanning XPS Microprobe with a monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV).

Electrochemical Hydrazine Oxidation

Electrochemical hydrazine oxidation was carried out using a CHI 760D Bipotentiostat (CH Instruments, Inc.) in a three-electrode system in 0.1 M KOH with an electrocatalyst-coated glassy carbon electrode (GCE), Pt wire, and SCE as the working, counter, and reference electrodes, respectively. The catalyst slurry was prepared by adding 5 mg of Au-TiO2 NCs or Au NPs in 5 mL of Millipore water and then sonicating for 30 min. A 2% polytetrafluoroethylene solution (10 μL) was added to the above slurry and sonicated for another 10 min. Then, 20 μL of the slurry was coated onto the GCE by drop casting and dried overnight under vacuum. The dried catalyst-modified GCE was tested for hydrazine oxidation in freshly prepared 0.1 M KOH with different concentrations of hydrazine. Prior to each sample loading, the GCE was cleaned by sonicating in water and 0.1 M H2SO4 and 0.1 M KOH solutions successively, followed by electrochemical cleaning through CV in a potential window of −1.0 to +1.0 V in 0.1 M H2SO4.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research [grant no. 01(2724)/13/EMR-II], New Delhi, India.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.6b00566.

XPS of TiO2 and citrate-capped Au-TiO2; CVs of bare and citrate-capped TiO2 and Au NPs for hydrazine electro-oxidation (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ Photocatalysis International Research Center, Research Institute for Science & Technology, Tokyo University of Science, 2641 Yamazaki, Noda, Chiba 278-8510, Japan (N.R.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rees N. V.; Compton R. G. Carbon-free Energy: A Review of Ammonia- and Hydrazine-based Electrochemical Fuel Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1255–1260. 10.1039/c0ee00809e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serov A.; Kwak C. Direct Hydrazine Fuel Cells: A Review. Appl. Catal., B 2010, 98, 1–9. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini C.; Shen P. K. Palladium-Based Electrocatalysts for Alcohol Oxidation in Half Cells and in Direct Alcohol Fuel Cells. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 4183–4206. 10.1021/cr9000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Wu H.; Zhai Y.; Xu X.; Jin Y. Synthesis of Monodisperse Plasmonic Au Core–Pt Shell Concave Nanocubes with Superior Catalytic and Electrocatalytic Activity. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2045–2051. 10.1021/cs400223g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suntivich J.; Xu Z.; Carlton E. C.; Kim J.; Han H.; Lee S. W.; Bonnet N.; Marzari N.; Allard L. F.; Gasteiger H. A.; Hamad-Schifferli K.; Shao-Horn Y. Surface Composition Tuning of Au—Pt Bimetallic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Carbon Monoxide and Methanol Electro-oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7985–7991. 10.1021/ja402072r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-Y. Water Management in Micro Direct Methanol Fuel Cells: Using Integrated Passive Micromixer. Open Fuel Cells J. 2011, 4, 1–6. 10.2174/1875932701104010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao S.-C.; Tang X.; Hsieh C.-C.; Alyousef Y.; Vladimer M.; Fedder G. K.; Amon C. H. Micro-electro-mechanical Systems (MEMS)-based Micro-scale Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Development. Energy 2006, 31, 636–649. 10.1016/j.energy.2005.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filanovsky B.; Granot E.; Presmanb I.; Kuras I.; Patolsky F. Long-term Room-Temperature Hydrazine/air Fuel Cells based on Low-cost Nanotextured Cu—Ni Catalysts. J. Power Sources 2014, 246, 423–429. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.07.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Jiang X.; Guo F.; Shi N.; Yin J.; Wang G.; Cao D. Carbon Fiber Cloth Supported Micro- and Nano-structured Co as the Electrode for Hydrazine Oxidation in Alkaline Media. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 94, 214–218. 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadakia K.; Datta M. K.; Velikokhatnyi O. I.; Jampani P.; Park S. K.; Chung S. J.; Kumta P. N. High Performance Fluorine Doped (Sn,Ru)O2 Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electro-catalysts for Proton Exchange Membrane Based Water Electrolysis. J. Power Sources 2014, 245, 362–370. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.06.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Yang S.; Vajtai R.; Wang X.; Ajayan P. M. Pt-Decorated 3D Architectures Built from Graphene and Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets as Efficient Methanol Oxidation Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 5160–5165. 10.1002/adma.201401877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y.; Bian T.; Choi S.; Jiang Y.; Jin C.; Fu M.; Zhang H.; Yang D. Kinetically Controlled Synthesis of Pt—Cu Alloy Concave Nanocubes with High Index Facets for Methanol Electro-oxidation. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 560–562. 10.1039/C3CC48061E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Lu D.; Chen Y.; Tang Y.; Lu T. Facile synthesis of Pd—Co—P ternary Alloy Network Nanostructures and their Enhanced Electrocatalytic Activity towards Hydrazine Oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 1252–1256. 10.1039/C3TA13784H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Zhang H.; Tangb Y.; Luo S. Controllable Growth of Graphene/Cu Composite and its Nanoarchitecture-dependent Electrocatalytic Activity to Hydrazine Oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 4580–4587. 10.1039/c3ta14137c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Liu Y.; Gao Q.; Ruan W.; Lin X.; Li X. Rational Construction of Strongly Coupled Metal–Metal Oxide–Graphene Nanostructure with Excellent Electrocatalytic Activity and Durability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10258–10264. 10.1021/am5016606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Dong S.; Wang E. Three-Dimensional Pt-on-Pd Bimetallic Nanodendrites Supported on Graphene Nanosheet: Facile Synthesis and Used as an Advanced Nanoelectrocatalyst for Methanol Oxidation. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 547–555. 10.1021/nn9014483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria-Chinchilla J.; Asazawa K.; Sakamoto T.; Yamada K.; Tanaka H.; Strasser P. Noble Metal-Free Hydrazine Fuel Cell Catalysts: EPOC Effect in Competing Chemical and Electrochemical Reaction Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5425–5431. 10.1021/ja111160r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrod S.; Bollard M. E.; Nicholls A. W.; Connor S. C.; Connelly J.; Nichol-son J. K.; Holmes E. Integrated Metabonomic Analysis of the Multiorgan Effects of Hydrazine Toxicity in the Rat. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 115–122. 10.1021/tx0498915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelnick S. D.; Mattie D. R.; Stepaniak P. C. Occupational Exposure to Hydrazines: Treatment of Acute Central Nervous System Toxicity. Aviat., Space Environ. Med. 2003, 74, 1285–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poso A.; von Wright A.; Gynther J. An Empirical and Theoretical Study on Mechanisms of Mutagenic Activity of Hydrazine Compounds. Mutat. Res. 1995, 332, 63–71. 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeier J. K.; Kjell D. P. Hydrazine and Aqueous Hydrazine Solutions: Evaluating Safety in Chemical Processes. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 1580–1590. 10.1021/op400120g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosca V.; Koper M. T. M. Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Hydrazine on Platinum Electrodes in Alkaline Solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 5199–5205. 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.02.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B.; He B.-L.; Huang J.; Gao G.-Y.; Yang Z.; Li H.-L. High Dispersion and Electrocatalytic Activity of Pd/Titanium Dioxide Nanotubes Catalysts for Hydrazine Oxidation. J. Power Sources 2008, 175, 266–271. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.08.090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Zhu M.; Zheng M.; Tang Y.; Chen Y.; Lu T. Electrocatalytic Oxidation and Detection of Hydrazine at Carbon Nanotube-supported Palladium Nanoparticles in Strong Acidic Solution Conditions. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 4930–4936. 10.1016/j.electacta.2011.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L. Q.; Li Z. P.; Qin H. Y.; Zhu J. K.; Liu B. H. Hydrazine Electrooxidation on a Composite Catalyst Consisting of Nickel and Palladium. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 956–961. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.08.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q.; Liu Y.; Wang Z.; Wei W.; Li B.; Zou J.; Yang N. Graphene Nanoplatelets Supported Metal Nanoparticles for Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydrazine. Electrochem. Commun. 2013, 29, 29–32. 10.1016/j.elecom.2013.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.; Yang J.; Liu J.; Huang Y.; Xiao J.; Zhang X. Properties of Pd Nanoparticles-Embedded Polyaniline Multilayer Film and its Electrocatalytic Activity for Hydrazine Oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 90, 382–392. 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.11.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koçak S.; Aslişen B. Hydrazine Oxidation at Gold Nanoparticles and Poly(bromocresolpurple) Carbon Nanotube Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Sens. Actuators, B 2014, 196, 610–618. 10.1016/j.snb.2014.02.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jena B. K.; Raj C. R. Ultrasensitive Nanostructured Platform for the Electrochemical Sensing of Hydrazine. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 6228–6232. 10.1021/jp0700837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Q.; Niu F.; Yu W. Pd-modified TiO2 Electrode for Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydrazine, Formaldehyde and Glucose. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 3155–3161. 10.1016/j.tsf.2010.12.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asazawa K.; Yamada K.; Tanaka H.; Taniguchi M.; Oguro K. Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydrazine and its Derivatives on the Surface of Metal Electrodes in Alkaline Media. J. Power Sources 2009, 191, 362–365. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benvidi A.; Kakoolaki P.; Zare H. R.; Vafazadeh R. Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Hydrazine at a Co(II) Complex Multi-wall Carbon Nanotube Modified Carbon Paste Electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 2045–2050. 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.11.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canales C.; Gidi L.; Arce R.; Ramırez G. Hydrazine Electrooxidation Mediated by Transition Metal Octaethylporphyrin-modified Electrodes. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 2806–2813. 10.1039/C5NJ03084F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim-Nezhad G.; Jafarloo R.; Dorraji P. S. Copper (Hydr)oxide Modified Copper Electrode for Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Hydrazine in Alkaline Media. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 5721–5726. 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Su X.; Tian X.; Huang Z.; Song W.; Zhao J. Preparation and Electrocatalytic Performance of Functionalized Copper-Based Nanoparticles Supported on the Gold Surface. Electroanalysis 2006, 18, 2055–2060. 10.1002/elan.200603598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P.; Song Y.; Chen L.; Chen S. Electrocatalytic Activity of Alkyne-functionalized AgAu Alloy Nanoparticles for Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Media. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 9627–9636. 10.1039/C5NR01376C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.; Kim D.; Hong D.; Yu Y.; Xu J.; Lin S.; Wen X.; Nichols E. M.; Jeong K.; Reimer J. A.; Yang P.; Chang C. J. A Molecular Surface Functionalization Approach to Tuning Nanoparticle Electrocatalysts for Carbon Dioxide Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8120–8125. 10.1021/jacs.6b02878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkhalaf F.; Schiffrin D. J. Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction on Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles Incorporated in a Hydrophobic Environment. Langmuir 2010, 26, 14995–15001. 10.1021/la1021565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N.; Sohn Y.; Pradhan D. Synergy of Low-Energy {101} and High-Energy {001} TiO2 Crystal Facets for Enhanced Photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2532–2540. 10.1021/nn305877v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachikawa T.; Yamashita S.; Majima T. Evidence for Crystal-Face-Dependent TiO2 Photocatalysis from Single Molecule Imaging and Kinetic Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7197–7204. 10.1021/ja201415j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman R.; Tirosh S.; Barad H.-N.; Zaban A. Direct Imaging of the Recombination/Reduction Sites in Porous TiO2 Electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2822–2828. 10.1021/jz401549e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N.; Leung K. T.; Pradhan D. Nitrogen Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide Based Pt-TiO2 Nanocomposites for Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 19117–19125. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V.; Wolf E. E.; Kamat P. V. Catalysis with TiO2/Gold Nanocomposites. Effect of Metal Particle Size on the Fermi Level Equilibration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4943–4950. 10.1021/ja0315199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob M.; Levanon H.; Kamat P. V. Charge Distribution between UV Irradiated TiO2 and Gold Nanoparticles: Determination of Shift in the Fermi Level. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 353–358. 10.1021/nl0340071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. R.; Hervier A.; Seo H.; Kennedy G.; Komvopoulos K.; Somorjai G. A. Highly n-Type Titanium Oxide as an Electronically Active Support for Platinum in the Catalytic Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 16006–16011. 10.1021/jp203151y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.; Tatsuma T. Mechanisms and Applications of Plasmon-Induced Charge Separation at TiO2 Films Loaded with Gold Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7632–7637. 10.1021/ja042192u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn Y.; Pradhan D.; Radi A.; Leung K. T. Interfacial electronic structure of gold nanoparticles on Si(100): Alloying versus quantum size effects. Langmuir 2009, 25, 9557–9563. 10.1021/la900828v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakthinathan S.; Kubendhiran S.; Chen S.-M.; Sireesha P.; Karuppiah C.; Su C. Functionalization of Reduced Graphene Oxide with β-cyclodextrin Modified Palladium Nanoparticles for the Detection of Hydrazine in Environmental Water Samples. Electroanalysis 2017, 29, 587. 10.1002/elan.201600339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon T.-Y.; Watanabe M.; Miyatake K. Carbon Segregation-Induced Highly Metallic Ni Nanoparticles for Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Hydrazine in Alkaline Media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 18445–18449. 10.1021/am5058635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar A.; Rahman M. M.; Kim S. H.; Hahn Y.-B. Zinc Oxide Nanonail Based Chemical Sensor for Hydrazine Detection. Chem. Commun. 2008, 2, 166–168. 10.1039/B711215G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar P.; John S. A. Synergistic Effect of Gold Nanoparticles and Amine Functionalized Cobalt Porphyrin on Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydrazine. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 3473–3479. 10.1039/C4NJ00017J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Wang Y.; Xiao F.; Ching C. B.; Duan H. Growth of Copper Nanocubes on Graphene Paper as Free-Standing Electrodes for Direct Hydrazine Fuel Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 7719–7725. 10.1021/jp3021276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud F.; Gross A. J.; Junior D. F.; Holzinger M.; Maduro de Campos C. E.; Acuna J. J. S.; Domingos J. B.; Cosniera S. Hydrazine Electrooxidation with PdNPs and Its Application for a Hybrid Self-Powered Sensor and N2H4 Decontamination. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, H3052–H3057. 10.1149/2.0071703jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Zang L.; Zhao J.; Wang C. Green Synthesis of Shape-defined Anatase TiO2 NCs Wholly Exposed with {001} and {100} Facets. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11736–11738. 10.1039/c2cc36005e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.