Abstract

Purpose:

To obtain rural breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of the quality and usability of CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis, a web-based, psychoeducational, distress self-management program; and explore the feasibility of gathering survivors’ perceptions about CaringGuidance™ using online focus groups (OFG)s.

Participants and Setting:

23 survivors of early-stage breast cancer, mean 2.5 years post- diagnosis, living in rural Nebraska.

Methodological Approach:

Participants reviewed the CaringGuidance™ program independently over 12 days (mean) before their designated OFG. Extent of participants’ pre-OFG review of CaringGuidance™ was verified electronically. Four synchronous, moderated OFGs were conducted including 5 to 7 women per group. Demographic and OFG participation data were used to assess feasibility. Transcripts of OFGs were analyzed using directed content analysis.

Findings:

All enrolled women participated in their designated OFG. In assessing program quality, participants reflected on their past and present self and future women, within the context of their rural identity. Five themes of CaringGuidance™’s quality and usability were identified. Recommendations were used to modify CaringGuidance™ prior to pilot efficacy trial.

Implications for Nursing:

Findings contribute to nurses’ knowledge and guide assessment and intervention pertaining to psychosocial needs of rural women with breast cancer, OFGs, and qualities rural women seek in web-based psychological interventions.

Keywords: Rural, breast cancer, Internet, focus group, distress, self-management

Lack of accessible patient-centered care for underserved populations (Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2013), and limited management of cancer-related distress (Pirl et al., 2014) represent national crises in oncology (IOM, 2008). Cancer-related distress is biopsychosocial and spiritual, ranging from mild depressive-symptoms to major psychiatric illness (National Cancer Institute, 2015). Thirty percent (Zabora, Brintzenhofeszoc, Curbow, Hooker, & Piantadosi, 2001) to 60% (Acquati & Kayser, 2017) of women with breast cancer experience significant cancer-related distress. Specifically, depressive-symptoms and anxiety have been found to be as prevalent as 47% and 67%, respectively, among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer (Linden,Vodermaier, MacKenzie & Greig, 2012). Depressive-symptoms may persist for 5 or more years (Maass, Roorda, Berendesn, Verhaak, & deBock, 2015), while adjustment disorder (Hack & Degner, 2004), post-traumatic stress (Elklit & Blum, 2011), and PTSD-symptoms (Kornblith et al., 2003) have been identified from two to 20 years post-diagnosis.

Quality of life, adherence to cancer treatment, and resource availability are adversely affected when mental health is overlooked (Holland et al., 2010). Early assessment and management of mental health is recommended to improved outcomes (Anderson et al., 2010; Kanani, Davies, Hanchett, & Jack, 2016), however few people with cancer receive this care (Holland & Alici, 2010).

For rural cancer survivors, resource scarcity is compounded by distance traveled to care, and stigma associated with cancer and mental health, resulting in greater distress and poorer mental health compared to non-rural survivors (Weaver, Geiger, Lu, & Case, 2013). Rural women with breast cancer who travel long distances for care experience greater depressive-symptoms than those with shorter commutes (Schlegel, Manning, Molix, Talley, & Bettencourt, 2012). Rural women are further challenged by a lack of support and stigma (Bettencourt, Schlegel, Talley, & Molix, 2007) that challenge their ability to prevent cancer-related distress and its deleterious outcomes.

Equity in access to psychosocial care for rural breast cancer survivors has received little attention (Bettencourt, Talley, Molix, Schlegel & Westgate, 2008). Web-based psychosocial interventions have been recommended for rural women with breast cancer (Bettencourt, Schlegel, Talley, & Molix, 2007) as these are private, accessible, and eliminate need to travel to receive care. As of mid-2017, nearly 86% of rural Americans had at least one available broadband network and only 2.5% had no access when satellite and mobile capabilities are taken into account (Brogan, 2017). Studies of web-based support interventions for women with breast cancer have been promising (Stanton, Thompson, Crespi, Link, & Waisman, 2013), but may be limited by high drop-out (Carpenter, Stoner, Schmitz, McGregor, & Doorenbos, 2014), and have not been specific to rural women. To combat drop-out and more substantially regulate intervention dose, researchers of web-based mental health interventions emphasize that programs be tailored to the needs and acceptable to prospective users to achieve engagement and retention (Ploeg et al., 2017).

CaringGuidance™ Program

CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis is a psychoeducational, web-based, distress self-management program, based on theories of stress/coping (Folkman & Greer, 2000), coping behavior (Roth & Cohen,1986), and cognitive processing and adjustment to illness (Creamer, Burgess, & Pattison, 1992; Lepore, 2001; Lepore & Helgeson,1998; Redd et al., 2001), set in a framework derived from the PI’s grounded theory of Acclimating to Breast Cancer (Lally, 2010; Lally, Hydeman, Schwert, Henderson & Edge, 2012). CaringGuidance™ was designed and tested in an iterative process by a team of psychologists, oncology nurses, breast cancer survivors and other health professionals to create an evidence-based, patient-centered, easy-to-use, distress self-management program (Lally, McNees, & Meneses, 2015).

CaringGuidance™ (https://my.caringguidance.org) contains six modules (22 subtopics) of supportive psycho-oncology based education/cognitive and behavioral techniques (Table 1) directed toward the initial months after diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer. Program-users learn coping strategies through content that aims to challenges their thinking, offer alternative perspectives and reinforce realistic expectations. To the best of our knowledge, it is one of the first web-based psychoeducational programs for women to be studied in the U.S. that is specifically focused on early post-diagnosis coping; when distress and depressive-symptoms are particularly amenable to intervention (Stagl et al., 2015).

Table 1.

CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis Program Content

| Learning Modulesa | Supportive Psycho-oncology Techniques Used |

|---|---|

| Are My Reactions Normal? |

|

| What Does this Diagnosis Mean? | |

| Who Am I Now? | |

| What are Strategies to Care for Myself? | |

| Moving Forward | |

| For Family & Friends | |

| Resources – glossary, links to resources, video library, mindfulness meditation, etc. | |

| Discussion Board |

Developed by Lally, RM. Copyright © 2016 The Research Foundation of The State University of New York – Licensed for research purposes to the University of Nebraska

Modules contain audio introduction by psychologist, 27 cognitive/behavioral/emotional exercises, 128 videos (plus 11 full interviews) of survivor and survivor families (African American and Caucasian survivors ages 30–70 with Stage 0 – III breast cancer), plus written text.

Evidence supports early intervention with psychoeducation (Brandao, Schulz, & Matos, 2017), use of cognitive-behavioral techniques for prevention (Pitceathly et al., 2009) and management of cancer-related distress (Moorey & Greer, 2012), and doing so in “low-intensity” (i.e. web-based, etc.) formats for mild to moderate psychological maladjustment (Christensen, 2010). Whereas the initial study of CaringGuidance™ demonstrated promising psychosocial outcomes (Lally, et al., 2016), participants were primarily urban and thus results may not be generalizable to rural women, thereby leading to the current study.

Conceptual Framework

Outcomes of online interventions such as CaringGuidance™ are predicated on user engagement (O’Connor et al., 2016), and persistence (Donkin & Glozier, 2012) supported by compatibility between users’ needs, content (Owen, Bantum, Gorlick, & Stanton, 2015), and ability to identify with the program (Donkin & Glozier). Therefore, concepts of the Digital Health Engagement Model (DIEGO) (O’Connor et al.) were used to inform the online focus group (OFG) interview guide and data analysis for this study. The DIEGO model posits four processes that individuals undergo while deciding to engage with an electronic health intervention (i.e. making sense, gaining support, registering for, and considering quality) of which this study focused on the concept of quality. The remaining model processes pertain to individuals’ awareness of the intervention and motivation for use (O’Connor et al.). In the current study, women were informed of the intervention and asked to use it at will for a few weeks. Therefore, participation in program review was captured, but motivation was not an outcome examined in this short term, research, program-review context. Rather, quality, which O’Connor’s preliminary model further subdivides into: a) quality of intervention interaction, b) quality of intervention information, and c) usability (O’Connor et al.) was the focus so that input from breast cancer survivors on quality and usability could be used to modify the program for later efficacy and implementation trials. In future trials, concepts such as motivation, will be measured as a function of engagement using appropriate study designs. The DIEGO model’s three quality concepts were operationalized for this study as accessibility, function, aesthetics, and content which study participants were asked to note during their pre-OFG program review and which informed the OFG interview guide (Table 2).

Table 2.

Structured Interview Guide for Synchronous Online Focus Group

| Welcome to the CaringGuidance Focus Group Discussion. Thank you all for agreeing to participate.a |

|---|

| Overview & Ground Rules |

|

| Questions |

|

| Closure: thank you all for participating. Your input will help us make changes to tde CaringGuidance™ program so tdat it will better serve tde needs of rural women. |

Content was prepared in advance and pasted into the Discussion Board. The Moderator typed responses and probing questions as needed during the focus group.

An approximate 10 second pause (as opposed to the typical 5 seconds (Krueger & Casey) was used to wait for additional responses before probing since it was not possible to know when a participant was typing.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to obtain rural breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of the quality and usability of the CaringGuidance™ program. Ultimately, our goal was to use this input to make CaringGuidance™ program modifications to support engagement of newly diagnosed rural women in upcoming clinical efficacy and implementation trials. Secondarily, we sought to explore the feasibility of gathering rural survivors’ perceptions of CaringGuidance™ using OFGs. Aims of the study were: a) to explore survivors’ perceptions of the accessibility, functionality, aesthetics and content of CaringGuidance™ based on their experiential knowledge of being diagnosed with breast cancer in a rural context, and b) to determine the ability to recruit and retain rural breast cancer survivors to independent review of web-based CaringGuidance™ followed by participation in synchronous, OFGs to collect input on the psychological intervention.

Method

Design

This study used a synchronous OFG design. Focus groups (FG) were used because the data of interest were breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of the CaringGuidance™ program based on their experiential knowledge with breast cancer and ruralness. FGs are an appropriate method for gathering perceptions for program design and development (Krueger & Casey, 2009) which was the ultimate goal of this study. The online format was chosen for the convenience of rural participants by eliminating travel as a barrier to participation while sampling women from a wide rural geographic region. An online format was also expected to provide participants with privacy (Fox, 2017) that an in-person FG in their rural community would not permit. Synchronous (real-time) was chosen over asynchronous (non-real time) so that the data would benefit from interactive communication of the participants (Fox).

University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board exemption was granted and materials used for recruitment and study conduct were approved.

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers distributed by three cancer centers throughout Nebraska to rural patients, one month to 10 years past their first diagnosis of Stage 0 to IIIA breast cancer. Although CaringGuidance™ addresses coping in the months following a new diagnosis, this range of survivors (i.e. years since diagnosis, stage) was chosen to gather input from women with diverse perspectives (Patton, 2002) following an opportunity to cognitively/emotionally process and interpret perceptions of the experience. An email address and computer/mobile device with Internet access was required, but iPads with wireless plans were available to loan as needed.

Recruitment flyers were also mailed by the local American Cancer Society (ACS) to breast cancer survivors. Press releases were distributed to rural newspapers. Several radio interviews were given by the PI to enhance recruitment efforts. Advertisements were also placed on a local breast cancer network webpage and a rural county Facebook exchange where residents communicate about goods and services.

Rural was defined as living in a county designated 6 (non-metro –urban population 2,500 to 19,000) to 9 (non-metro-completely rural or less than 2,500 population) by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum Codes or living in a zip code designated as “10” (rural) by the 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes. The two criteria were used to identify women living in completely rural counties, and also include zip codes within non-rural counties that are designated as rural. These criteria are consistent with criteria used in previous studies (e.g. Henry, Schlegel, Talley, Molix, & Bettencourt, 2010).

Procedures

Women emailed or called the research office for screening. Consent forms were emailed and later reviewed by phone with the PI. Enrollment followed participants’ return of an emailed affirmation of consent.

Participants received the CaringGuidance™ URL, and a unique username and password that provided online access to CaringGuidance™ for a minimum 24 hour period prior to their assigned OFG. OFG assignment was based on the order in which participants came into the study unless the date proposed posed a conflict; then the next available focus group was offered. A demographics survey was mailed to and returned by each participant. To support rigor, CaringGuidance™ use by participants during the pre-OFG period was tracked by an electronic data analysis system to verify and describe the extent to which participants reviewed the program.

Participants were instructed to log into CaringGuidance™ as desired during their review period, and take note of the program’s: (a) accessibility (e.g. technical issues, convenience); (b) aesthetics (e.g. visual aspects that were pleasing (or not) and tone of content); (c) functionality (e.g. navigating and functioning of program features); and (d) content (e.g. current relevance and applicability to them and newly diagnosed rural women).

Focus group conduct.

Participants, identified only by username (e.g. FGP01), logged into the CaringGuidance™ discussion board at the time assigned from a location of their choosing. A nurse moderator (doctoral candidate trained by the PI) greeted participants online (Table 2). The PI was available to troubleshoot difficulties, but did not participate in the OFGs so that participants could feel free to voice their opinions openly.

A structured interview guide (Krueger & Casey, 2009) (Table 2) was used to solicit participant input. The moderator cut-and-pasted one question at a time from the guide into the discussion board and waited for participants’ typed responses, responding with, “Thank you #X.” When responses slowed, non-respondents were probed with a statement such as, “Participant 10 would you like to add anything on this topic?” To accommodate anyone who might have a slower Internet connection, or typed slowly, the discussion board was left open until the next morning.

Procedures were modified iteratively as experience with the OFG format was gained. For example, the moderator developed a discussion tracking sheet because participants’ responses during group 1 quickly scrolled off screen during rapid participation, making it difficult to recall who had and had not responded. Use of this form facilitated probing non-responders. Question order was modified in response to a participant’s indication that too much time was used to discuss functionality and accessibility, that were less important to her and others, than program content. In response to participants’ wishes and finding that participants had limited time to express all their perceptions if early questions were too structured, the moderator began group 2 with an open “grand tour” question and followed this with a question pertaining to program content (Table 2).

During group 3, an assistant moderator, at an iPad, was added to respond to participants’ technical issues and participants who strayed off-track in their responses. Finally, it was determined that groups smaller than 7 were more manageable for a single moderator and the protocol was amended to add a fourth group, maintaining group sizes between 5 to 7 participants. Approximately five participants per group and use of a second moderator are consistent with current recommendations for online and conventional focus groups (Fox, 2017).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and feasibility data. Focus group transcripts were analyzed using qualitative directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Directed content analysis is appropriate when there is an existing conceptual framework to extend, such as the DIEGO model (O’Connor et al., 2016) in this study, which then guides the variables of interest and initial coding (Hsieh & Shannon). Analysis was conducted by the PI, an additional nurse scientist (CE) experienced in focus groups and qualitative analysis, and the focus group moderator (SB). SB and CE contributed contextual knowledge of rural women from their life-experience and research. ATLAS.ti 8 was used to organize data.

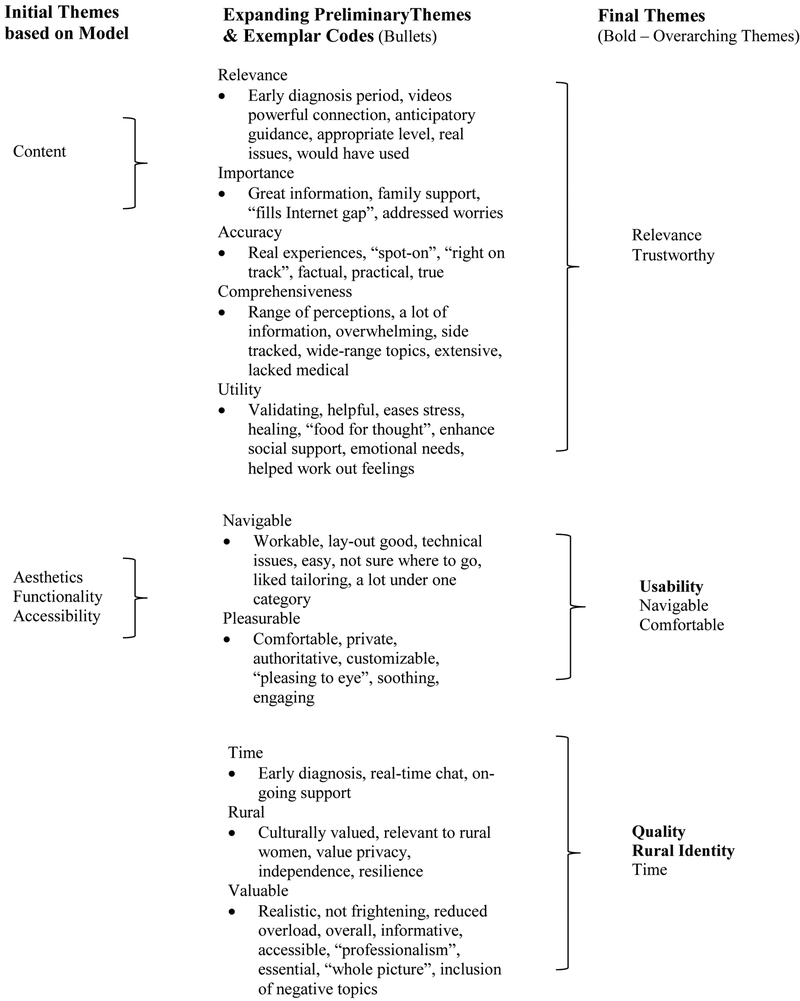

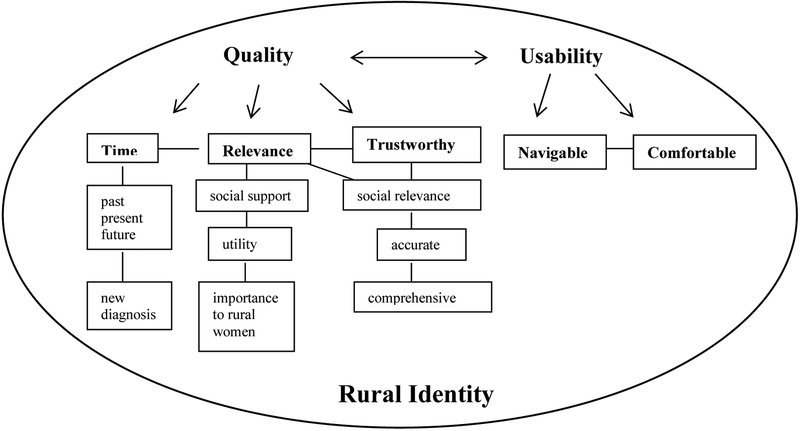

Focus group discussions were downloaded from the discussion board and personal identifiers removed. Analysis began with team members each reading the transcripts thoroughly and independently coding each participants’statements using open, line-by-line coding. Each member initially highlighted passages that addressed the pre-determined concepts (codes) of quality (i.e. accessibility, functionality, aesthetics and content). These concepts proved inadequate to capture all the data and were expanded to additional preliminary themes (Figure 1) through team discussion (Hsieh& Shannon, 2005). Notes in the form of narrative definitions, positive and negative dimensions and summaries of themes were written and discussed. Codes and themes were compared and contrasted as analysis proceeded and preliminary themes were collapsed and refined, resulting in five themes describing the overarching concepts of quality, usability and rural identity (Figure 2). Differences among team members were resolved by returning to the transcripts for clarification and expert input from CE and SB regarding rural cultural. An auditable trail of codes, themes, team discussions and decisions was maintained. After four FG, it was determined that data were redundant and not contributing further to theme development so collection ended.

Figure 1.

Partial Audit Trail for Focus Group Directed Content Analysis

Figure 2.

Themes and Supporting Concepts from Rural Survivors’ Focus Group Review of Web-based, Distress Self-Management Psychoeducation Program: CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Throughout analysis, notes were maintained of participants’ recommended changes to CaringGuidance™ in keeping with the goal to modify the program to meet the needs of rural women with breast cancer. Changes made were shared in writing with each participant, and comments were invited.

Results

Feasibility of Recruitment, Retention and OFGs

Over three months in 2017, thirty-eight women were screened and 23 enrolled and completed OFG participation. Twenty women were recruited through information received from the rural cancer centers where they had or were receiving care and 14 of these women enrolled. Flyers mailed by the ACS recruited eight and six of these women enrolled. Advertisement in newsletters resulted in four women recruited and two enrolled, while other recruitment was primarily word of mouth resulting in one additional enrollment.

Twelve geographically distant rural Nebraska counties were represented by participants ranging in age from 37 – 79 years (Table 3). The most common reason for ineligibility was non-rural residency (n= 10). Five women declined participation prior to consent due to date conflicts (n=2), family emergency (n=1), illness (n=1), and an inoperable computer without time to ship a study loaner iPad prior to the scheduled group (n=1). Once consented, all women enrolled, reviewed the program (Table 4), attended and participated in the focus group to which they were assigned (100% retention) and received $20 (n= 3 declined honorarium).

Table 3.

Participant Demographics

| N = 23 | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ||

| Age (years) | 58.91 (11.57) | |

| 37 – 46 | 4 | |

| 47 – 56 | 4 | |

| 57 – 66 | 8 | |

| 67 – 76 | 6 | |

| 77 – 79 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity or race | ||

| Caucasian | 22 | |

| Mixed race | 1 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 20 | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 3 | |

| Education (highest level) | ||

| High school | 1 | |

| Some college | 8 | |

| Technical/trade school | 4 | |

| College graduate | 10 | |

| Occupation | ||

| Retired* | 7 | |

| Administrative office/manager/administrator | 8 | |

| RN/pharmacy /surgery technician | 5 | |

| Education | 3 | |

| Other (sales, homemaker, laborer) (each ≤ 2 /occupation – concealed for anonymity) | 5 | |

| Rural residency (years)a | 39.5 (20.9) | |

| 5 – 14 | 3 | |

| 15 – 25 | 4 | |

| 26 or more | 15 | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 2.5 (1.4) | |

| Less than 1 year | 2 | |

| 1 – 3 | 13 | |

| 3 – 6 | 8 | |

| Breast cancer stage | ||

| 0 | 2 | |

| I | 8 | |

| II | 12 | |

| IIIA | 1 |

Five participants indicated they were retired but also listed an occupation so the n exceeds 23.

Table 4.

Participant Computer/Internet Experience & Use of CaringGuidance™

| N = 23 | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Typical daily Internet use (hours)a | 2.39 (2.13) | |

| 1 – 1.5 | 9 | |

| 2 – 2.5 | 9 | |

| 3 or more | 4 | |

| Home computer shared withb | ||

| Spouse/partner | 10 | |

| Children | 4 | |

| Have a mobile device | ||

| Yes | 20 | |

| No | 3 | |

| Primary Internet connection for study participationc | ||

| High speed broadband (DSL) | 8 | |

| Wireless | 11 | |

| Satellite | 2 | |

| Multiple connections | 2 | |

| I don’t know | 1 | |

| Pre-Focus Group Time Logged into CaringGuidance™ per participantd | 5.4 – 293.7 minutes [range] | 124.75 minutes[mean] |

| Time Logged on CaringGuidance Total and by Focus Groupe | 2869.2 minutes | |

| Group 1 (n = 7) | 455.8 minutes over mean of 8 days | 65.11minutes |

| Group 2 (n = 5) | 683.3 minutes over mean of 14 days | 136.66 minutes |

| Group 3 (n = 6) | 824.4 minutes over mean of 14 days | 137.40 minutes |

| Group 4 (n = 5) | 905.6 minutes over mean of 15 days | 181.12 minutes |

| CaringGuidance™ Content Viewed | ||

| Learning modules (viewed by n = 23) [all modules sections viewed] |

346 views (range 1 –22/participant) | |

| Exercises (viewed by n = 22) [all Exercises accessed, each Exercise accessed by a single participant 1 – 12 times] |

346 views (range 0 – 75/participant) | |

| Survivor videos (viewed by n = 18) [69 of 139 video clips viewed] |

198 views (0 – 47/participant) |

one participant did not report

participants could indicate sharing computer with both spouse/partner and children

participants reported rapid program response times and minimal dropped connections with connection methods

technical issues reported during the program review period: logging-in (n = 1), and typing in text boxes (n= 1) resolved with minimal guidance from the PI over the phone

participant use resulted in 1,451 CaringGuidance™ total page views

Participants had online access to CaringGuidance™ on average 12 days (ranged 1 – 27 days; mean 8 – 15 days per group) before their focus group. All participants reported having computer and Internet access at home as well as the majority had a mobile device (Table 4).

All participants viewed the learning modules, 22 participants reviewed exercises, and 18 reviewed survivor videos within the CaringGuidance™ program. Table 4 describes participant activity during pre-OFG review of CaringGuidance™.

The evening of each OFG, participants logged onto the CaringGuidance™ discussion board within 3 to 7 minutes of the start time and remained online for the full one-hour session. No responses were received during the extended period that participants had access to the discussion board after their group ended (100% retention and participation).

Focus Group Themes

While evaluating CaringGuidance™, participants reflected upon their diagnosis and unmet cognitive and emotional needs within the context of their past and present rural environment. Focusing on their own continued need to connect with other breast cancer survivors, they progressed to thinking broadly toward the needs of all rural women and hoped to benefit future newly diagnosed women with access to CaringGuidance™. Participants in all groups focused on the value that CaringGuidance™ might have had to them when diagnosed, and its value for women in the future, supporting the concepts of Quality and Usability within the DIEGO model (O’Connor et al., 2016), framed within the context of their Rural Identity (Figure 2).

Quality.

Survivors evaluated and characterized the program’s quality with respect to time expenditure, relevance to them and newly diagnosed rural women, and CaringGuidance™’s trustworthiness. Evaluation of quality was imbedded within the survivors’ rural cultural perspective.

Time.

Quality was measured by whether CaringGuidance™ was perceived as worth participants’ time and whether its contents were appropriate for the “right time” in women’s cancer experience. Reflecting back on their diagnoses, this period was remembered as stressful and overwhelming. One woman said, “When I was first diagnosed, I’m not sure anything would have helped.” However, another woman explained that at diagnosis, she was “bombarded with books and videos” and thus, sees CaringGuidance™ as “a great one stop shop” that may reduce feeling overwhelmed. Agreement came from other women who said, “I wish I would have had something like this when I was first diagnosed…I can see this tool being useful in answering questions that have not come to mind when first diagnosed.” As survivors, they recognized that the program’s journaling areas may serve as an archive for newly diagnosed women to “read three years later.”

A desire for CaringGuidance™ to fit their current needs as survivors was also expressed. Lack of information for longer-term survivors was the principal disappointment expressed about the program. Looking forward however, these women highly endorsed use of CaringGuidance™ in clinical practice as “an essential tool,” enabling newly diagnosed rural women to have access to this information.

Relevance.

The participants also measured quality by the relevance of the program’s content to themselves as women who are part of rural communities. They described themselves, and rural women overall, as “stoic”, “rugged” and “independent. One woman added, “we (I) forget that we can’t do it all”. Although these women may have given the appearance of needing little support when diagnosed, they expressed that this was not true. Rather, online delivery of CaringGuidance™ was embraced as having the potential to fill rural women’s need for social support; offering support without barriers of cancer-stigma, lack of privacy, and geographic isolation that make meeting other survivors and obtaining support difficult. “A place [program] like this would have been an oasis,” stated one woman as she discussed the importance of CaringGuidance™ to filling support needs. Another woman added, “I really liked there were different ages of women”, in the program’s survivor videos, and another added, “I loved the fact that some of the women [in videos] had the same cancer I did.” Thus, CaringGuidance™ “provided a connection” which allowed social comparisons to be made and for receipt of validation of thoughts and emotions that these women described as lacking because, “women in rural areas don’t have the camaraderie that women in urban areas do.”

Quality was also judged according to the importance and utility of the information contained within CaringGuidance™ as it related to women in rural communities. CaringGuidance™ was described as beneficial in providing “food for thought” regarding coping with cancer and the program’s journaling exercises were praised for providing the feeling of, “doing something for myself” and “promoted processing” of the diagnosis that rural women may not give themselves time or permission to do. Furthermore, these women recognized that CaringGuidance™ refuted rural independence and stoicism, teaching and reinforcing that it was “alright to cry and be angry”, “allowing people to help is good”, and that “interaction with other people is beneficial.”

Finally, these women recognized that CaringGuidance™ held relevance for families that also contributed to its quality. Said one women, “this might have helped me handle things a little differently with my family if I’d had access to this program when I was first diagnosed.”

Trustworthy.

CaringGuidance™’s perceived social relevance to participants’ contributed to their trust in the program. The program provided extra reassurance and a feeling “that I wasn’t different.” That feeling of “belonging” came in part from the fact that participants’ reported no content that made them uncomfortable or that was impractical given their norms and social context. Trust was also garnered through the comprehensive, accurate content and “professionalism” of CaringGuidance™. Participants noted that the content “deals with the whole picture”, and “a wide variety of thoughts and feelings” which was “spot-on to working through and thinking about the emotions and worries I felt when first diagnosed.” A participant stated that she appreciated that, “the negative ways of dealing with cancer were in it [program].” The participants trusted the advice of the survivors in the programs’ videos, “who had already been where you are now” and shared, “what worked for them, what didn’t work for them…the advice was good.” As the participants reflected on their past, they looked forward at newly diagnosed women and endorsed CaringGuidance™ as “a great tool…because what we need is true information so that we can focus on surviving and I believe that this program would be that tool.”

Usability.

Initial hesitancy to log-on to the program was due to an expectation that engaging in CaringGuidance™ would be time-consuming. They found that this concern was unfounded. Participants overall shared the opinion that, “it just took a moment to log-in and navigation was speedy!” In fact, after their initial exposure to the program, participants expressed regret that they had not started using the program earlier in the review period to have more time with the content. Lacking a chance to “see it all” participants in every group requested to retain their access to the program after their focus group.

Navigable

Participants described CaringGuidance™ as “easy to navigate.” Video and text content were “easy to find,” while moving throughout the program and “finding my way around” was met with ease. The structure of CaringGuidance™ was described as “well thought-out” with the only drawback being that some women felt “overwhelmed at first” and “could not choose” among the “interesting topics,”, becoming “sidetracked” when clicking links that took them to additional content. A participant expressing these concerns, however, said, “I did eventually get the hang of it…” In contrast, most women expressed satisfaction with the ability to move at-will between program modules and noted navigational features they appreciated, including the ability to save and return to journaling exercises, the tailoring feature to assist in finding relevant content, and the program’s tracking and display of participants’ user history to aid in returning to previously accessed modules.

Comfortable.

Despite voicing concern that newly diagnosed women may be overwhelmed by the volume of program content, these participants believed that future women will find CaringGuidance™ a place of comfort. Several exclaimed, “I like that the color scheme was NOT pink!” while others agreed that the “woods background is peaceful and calming.” Others appreciated that CaringGuidance™ was “not cluttered or busy” and that the “type in exercises is really big, WOW, I like that!” Comfort was also derived from the program’s writing-style, described as, “user-friendly and felt very personal”, “the site didn’t tell me how I should be feeling,” “it reaffirmed that most women survive”, and “it [program] was not as scary as randomly searching the Internet.” Finally, survivors expected CaringGuidance™ to bring comfort to rural women in particular through the privacy of its online format. As one woman explained, “[Rural] support groups have no anonymity and the town gossip is sitting across from you. So…the stories of the survivors [videos] would have been beneficial to me.”

Recommended program modifications

No program deletions were recommended by participants. Recommended additions to CaringGuidance™ were in categories of treatment, rural issues, survivorship, diet, and using CaringGuidance™ and resulted in modifications to content and content links (Table 5).

Table 5.

Rural Survivors’ Recommendations for Content Additions

| Theme | Recommendation Additions | CaringGuidance™ Modules or Parts Modified |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment |

|

“Questions & Misconceptions”

|

| Diet |

|

“Moving Forward”

|

| Rural issues |

|

“Is a Support Group Right for Me?”

|

| Survivorship |

|

“Frequently Asked Questions”

|

| CaringGuidance™ |

|

“Frequently Asked Questions”

|

Discussion

This study identified that it is feasible to recruit and retain rural breast cancer survivors of various ages, diagnoses, and time since diagnosis in OFG and testing of a web-based psychoeducational self-management program. These findings contribute to the limited evidence on factors potentially associated with engagement in web-based interventions among people with cancer (Owen et al., 2015), and is the first report on factors that may enhance future engagement of rural breast cancer survivors in CaringGuidance™. Knowing that rural women are able and willing to participate in OFGs and use web-based interventions is important to overcoming negative assumptions about rural Internet use and provides opportunities for further development of easily-accessible and relevant distress self-management for women to reduce current rural mental health disparities.

These breast cancer survivors predominantly endorsed CaringGuidance™ as a quality program; describing it as trustworthy and relevant to the psychosocial needs of newly diagnosed women, easy to navigate, and with a comfortable feel. These findings contribute to understanding what rural women look for in an online psychoeducational intervention and likewise, bode well for engaging future rural women in CaringGuidance™. These findings also contribute to existing knowledge on web-based health interventions by corroborating earlier work on the importance of fit (Owens et al., 2015) and extending concepts proposed by the DIEGO model (O’Connor et al., 2016) with those relevant to rural cancer survivors, including: a) a good use of time; b) aesthetically and perceptively comfortable to view; and c) rural identity, which provided a lens through which rural women evaluate program quality.

Trust is also a key ingredient to retaining rural breast cancer survivors in psychoeducational interventions (Meneses et al., 2013). Thus, it was not surprising that the rural survivors in this current study judged CaringGuidance™ by the level of trust they perceived in the program. Trust was determined by the perception that CaringGuidance™ provided accurate information, as well as on the emotional and social connection the women felt with the survivors in the program’s videos. This sense of “fit” and social connection between an online program and cancer survivors, especially those constrained by their social environment, is essential for early online cancer distress intervention engagement (Owen et al., 2015).

Most of the women in this study enjoyed the ability to navigate CaringGuidance™ as it suited them. Consistent with this finding are those of Donkin and Glozier (2012) in which the ability of users to navigate to program areas that meet their needs, at their own pace, was shown to facilitate users’ persistence in psychological interventions and increase feelings of benefit from the program. Although users’ engagement in online interventions decreases over time (Owen et al., 2015), knowing that rural breast cancer survivors, for the most part, favored a flexible program format, which is shown in other research to support persistent use, is an important contribution to future development of online interventions for rural women.

Finally, several limitations must be noted. First, while OFGs offer participants convenience and privacy, such groups are limited by the inability to observe body language, appreciate voice inflection, and interact aside from their typed words. Participants may have felt constrained by typing their thoughts; however this was not expressed by the participants. Constraints are an inherent problem with FG, however, in that participants reluctant to speak during in-person FG, for whatever reason, may be less represented in the data. Lastly, this study focused on rural Nebraskan women who were mostly educated, employed, Caucasian volunteers who had computers, mobile phones and Internet experience, and thus, the findings are limited by lack of diversity and may not be applicable to all women in other rural regions of the country.

Implications for Nursing

The study’s findings contribute to nurses’ knowledge regarding needs of rural women with breast cancer, rural breast cancer survivors’ participation in OFGs, and qualities sought by rural women in web-based psychological self-management interventions. The results demonstrate that gaps in support and available psychosocial care for rural women diagnosed with breast cancer persist since earlier published work (e.g. Bettencourt, Schlegel, Talley, & Molix, 2007) and thus a need exists for oncology nursing interventions and research in this area. Oncology nursing researchers should continue to extend models of digital health engagement with data from cancer survivors from diverse backgrounds and with varying diagnoses and Internet experience.

Nurses clinical application of the knowledge gained through this study’s OFGs include assessment of newly diagnosed rural women’s support networks, attitudes and beliefs about seeking and accepting support, and available local support services in their communities, as well as their trust and comfort accessing these. Nurses should validation rural women’s psychosocial needs given their admitted propensity toward reluctance to show need for or seek support. Explore alternatives for meeting psychosocial needs with rural women who lack access or fear stigma associated seeking local psychosocial support.

Oncology nurses may also take from these findings that rural women newly diagnosed with breast cancer will likely endorse web-based, psychoeducational interventions that are private, trustworthy, easily navigable, relevant to their rural social environment, and do not require large amounts of time. Thus, nurses should assist women in finding quality, evidence-based resources on the web that fit their needs as more are implemented into practice over the coming years. Likewise, health care providers should keep the qualities of web-based interventions endorsed by rural breast cancer survivors in mind and consider the transferability of the current findings when developing or recommending interventions to individuals who share contextual similarities with these women, for example caregivers experiencing distress (e.g. Ploeg et al., 2017).

Finally, nurses should not assume that rural women lack Internet access, and thus will not use web-based interventions, or participate in OFG. This study showed that a convenience sample of breast cancer survivors of all ages accessed the Internet daily at home and also possessed mobile devices. These women also volunteered and readily participated in OFGs overall with little difficulty after independently navigating and reviewing all aspects of the CaringGuidance™ web-based program. Thus, web-based alternatives to face-to-face psychosocial interventions (e.g. Carpenter et al., 2014) are feasible for rural women who should be given opportunities to receive care, participate in research and lend experiential knowledge to interventions through electronic means.

Conclusion

Synchronous OFGs were feasible to conduct among rural Nebraskan breast cancer survivors. CaringGuidance™ content, with minimal additions, was endorsed by rural survivors as a quality self-management tool for distress among newly diagnosed rural women. Survivors’ input resulted in modifications to CaringGuidance™ leading up to a randomized pilot study among newly diagnosed rural women. Finally, identification of program qualities desired by rural survivors, that are also likely to support program engagement among newly diagnosed women, will guide future implementation of CaringGuidance™ in clinical practice.

Knowledge Translation.

It is feasible to conduct synchronous online focus groups for rural breast cancer survivors of all ages due to growing availability of Internet access and women’s demonstrated acceptance of this format in this study.

Rural women with breast cancer require psychosocial care that is convenient, given their distant location, and private to reduce concerns with cancer and mental health related stigma.

The quality and usability of CaringGuidance™ was endorsed by rural survivors thus supporting the likelihood of future user engagement and potential translation of this web-based psychoeducational intervention to clinical practice.

Acknowledgement:

This study was funded by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research Health Disparities Grant. CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Drs. Eisenhauer, and Kupzyk, and Ms. Buckland declare that they have no financial conflict of interest. Dr. Lally also has no financial conflict of interest, however, was funded by a grant from the American Cancer Society MRSG 11–101-01-CPPB and the Community Foundation of Greater Buffalo to develop the intervention CaringGuidance™ After Breast Cancer Diagnosis, which is the subject of this work.

Footnotes

Informed consent was obtained from each study participant according to IRB approved consent process.

Contributor Information

Robin M. Lally, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Nursing, Omaha Division, Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center.

Christine Eisenhauer, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Nursing, Northern Division.

Sydney Buckland, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Nursing, Omaha Division.

Kevin Kupzyk, University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Nursing, Omaha Division.

References

- Acquati C & Kayser K (2017). Predictors of psychological distress among cancer patients receiving care at a safety-net institution: the role of younger age and psychosocial problems. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 2305–2312. Doi 10.1007/s00520-017-3641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen BL, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, Mundy BL, Yang HC, & Carson WE (2010). Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clinical Cancer Research, 16(12), 3270–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, & Molix LA (2007). The breast cancer experience of rural women: A literature review. Psycho-Oncology 16 (10), 875–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Talley AE, Molix L, Schlegel R, & Westgate SJ (2008). Rural and urban breast cancer patients: health locus of control and psychological adjustment. Psycho-Oncology, 17 (9), 932–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao T, Schulz MS, & Matos PM (2017). Psychological adjustment after breast cancer: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psycho-Oncology, 26 (7), 917 – 925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan P (2017). U.S. broadband availability mid-2016. (Research Brief August 25, 2017). USTelecom: The Broadband Association; Retrieved from USTelecom website: https://www.ustelecom.org/sites/default/files/US%20Broadband%20Availability%20Mid-2016%20formatted.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Stoner SA, Schmitz K, McGregor BA, & Doorenbos AZ (2014). An online stress management workbook for breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 458 – 468; doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9481-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H (2010). Increasing access and effectiveness of using the internet to deliver low intensity CBT In Bennett-Levy J, Richards DA, Farrand P, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Kavanagh DJ, Klein B, Lau MA, Proudfoot J, Ritterband L, White J, & Williams C (Eds.). Oxford Guide to Low Intensity CBT Interventions (pp.53 – 67). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Burgess P, & Pattison P (1992). Reaction to trauma: A cognitive processing model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(3): 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donkin L, & Glozier N (2012). Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: A qualitative study of treatment completers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elklit A & Blum A (2011). Psychological adjustment one year after the diagnosis of breast cancer: A prototype study of delayed post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of clinical Psychology, 50,350–363. Doi: 10.1348/014466510X527676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Greer S (2000). Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: When theory, research and practice inform each other. Psycho-Oncology 9(1): 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox F (2017). Meeting in virtual spaces: Conducting online focus groups In Braun V, Clarke V, & Gray D (Eds.), Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques (pp. 275–299). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hack TF, & Degner LF (2004). Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psycho-Oncology, 13, 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry EA, Schlegel RJ, Talley, Amelia E, Molix LA, & Bettencourt BA (2010). The feasibility and effectiveness of expressive writing for rural and urban breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37(6), 749 – 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, & Alici Y (2010). Management of distress in cancer patients. The Journal of Supportive Oncology, 8, 4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Anderson B, Breitbart WS, Compas B, Dudley MM, Flesihman S, Fulcher CD, Greenberg DB, Greiner CB, Handzo GF, Hoofring L, Jacobsen PB, Knight SJ, Learson K, Levy MH, Loscalzo MJ, Manne S, McAllister-Black R, Riba MB, Roper K, Valentine AD, Wagner LI, Zevon MA (2010). Distress management. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 8(4), 448–474–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. DOI: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2013). Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2008). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanani R, Davies EA, Hanchett N, & Jack RH (2016). The association of mood disorders with breast cancer survival: an investigation of linked cancer registration and hospital admission data for South East England, Psycho-Oncology, 25, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, Weiss RB, Zhang C, Zuckerman EL, Rosenberg S, Mertz M, Payne D, Jane Massie M, Holland JF, Wingate P, Norton L, & Holland JC (2003). Long-term adjustment of survivors of early-stage breast carcinoma, 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer, 98, 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruege RA & Casey MA (Eds.). (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lally (2010). Acclimating to breast cancer: A process of maintaining self-integrity in the pretreatment period. Cancer Nursing, 33(4), 268–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally RM, Bellavia G, Wu B, Gallo S, Zhao J, Erwin DO, & Meneses K (2016, March). CaringGuidance™ Internet Intervention Reduces Distress after Breast Cancer Diagnosis Poster presented at annual meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Lally RM, Hydeman JA, Schwert K, Henderson H, & Edge SB (2012). Exploring the first days of adjustment to cancer: A modification of acclimating to breast cancer theory. Cancer Nursing, 35 (1), 3 – 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally RM, McNees P, & Meneses K (2015). Application of a novel transdisciplinary communication technique to develop an internet-based psychoeducational program. Applied Nursing Research E7 – 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ (2001). A social-cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer In Baum A& Andersen BL(Eds.) Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001: 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS (1998). Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and mental health after prostate cancer. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 17(1): 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, & Greig D (2012). Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141, 343–351. Doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass SWMC, Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Verhaak PFM, & deBock GH (2015). The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: A systematic review. Maturitas, 82, 100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses KM, Benz RL, Hassey LA, Yang ZQ, & McNees MP (2013). Strategies to retain rural breast cancer survivors in longitudinal research. Applied Nursing Research, 26, 257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorey S & Greer S (Eds.). (2012). Oxford Guide to CBT for People with Cancer (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2015, February 19). Adjustment to cancer: anxiety and distress-for health professional (PDQ®). Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/anxiety-distress-pdq [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor S, Hanlon P, O’Donnell, Garcia S, Glanville J, & Mair FS (2016). Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16 (1), 120 Doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0359-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JE, Bantum EO, Gorlick A, & Stanton A (2015). Engagement with a social networking intervention for cancer-related distress. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49,154–164. Doi 10.1007/s12160-014-9643-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Designing qualitative studies In Patton MQ (Ed.) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (5th ed.) (pp. 209 – 257). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pirl WF, Fann JR, Greer JA, Braun I, Deshields T, Fulcher C, Harvey E, Holland J, Kennedy V, Lazenby M, Wagner L, Underhill M, Walker DK, Zabora J, Zebrack B, & Bardwell WA (2014). Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers. Cancer, 120 (19), 2946–2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitceathly C, Maguire P, Fletcher I, Parle M, Tomenson B, & Creed F (2009). Can a brief psychological intervention prevent anxiety or depressive disorders in cancer patients? A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Oncology, 20, 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, Valaitis R, McAiney C, Duggleby W, Bartholomew A, & Sherifali (2017). Web-based interventions to improve mental health, general caregiving outcomes, and general health for informal caregivers of adults with chronic conditions living in the community: rapid evidence review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(7), e263. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redd WH, DuHamel KN, Johnson Vickberg SM, Ostroff JL, Smith MY, Jacobsen PB & Manne SL (2001) Long-term adjustment in cancer survivors: Integration of classical-conditioning and cognitive-processing models In Baum A & Andersen BL (Eds.) Psychosocial Interventions for Cancer. (pp. 77–97). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, & Cohen LJ (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41(7), 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel RJ, Manning MA, Molix LA, Talley AE, & Bettencourt BA (2012). Predictors of depressive symptoms among breast cancer patients during the first year post diagnosis. Psychology and Health, 27 (30), 277 – 293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagl JM, Bouchard LC, Lechner SC, Blomberg BB, Gudenkauf LM, Jutagir DR, Gluck S, Derhagopian RP, Carver CS, & Antoni MH (2015b). Long-term psychological benefits of cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer, 121 (11), 1873–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Thompson EH, Crespi CM, Link JS, & Waisman JR (2013). Project connect online: randomized trial of an internet-based program to chronicle the cancer experience and facilitate communication. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(27), 3411 – 3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services. (2010). Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes. Retrieved from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/documentation/

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services. (2013). Rural-Urban Continuum Codes https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/

- Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, & Case LD (2013). Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer 119(5), 1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, & Piantadosi S (2001). The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology, 10, 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]