Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Elevated frontal and striatal reactivity to drug cues is a transdiagnostic hallmark of substance use disorders. The goal of these experiments was to determine if it is possible to decrease frontal and striatal reactivity to drug cues in both cocaine users and heavy alcohol users through continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) to the left ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC).

METHODS:

Two single-blinded, within-subject, active sham–controlled experiments were performed wherein neural reactivity to drug/alcohol cues versus neutral cues was evaluated immediately before and after receiving real or sham cTBS (110% resting motor threshold, 3600 pulses, Fp1 location; N= 49: 25 cocaine users [experiment 1], 24 alcohol users [experiment 2]; 196 total functional magnetic resonance imaging scans). Generalized psychophysiological interaction and three-way repeated-measures analysis of variance were used to evaluate cTBS-induced changes in drug cue-associated functional connectivity between the left VMPFC and eight regions of interest: ventral striatum, left and right caudate, left and right putamen, left and right insula, and anterior cingulate cortex.

RESULTS:

In both experiments, there was a significant interaction between treatment (real/sham) and time (pre/post). In both experiments, cue-related functional connectivity was significantly attenuated following real cTBS versus sham cTBS. There was no significant interaction with region of interest for either experiment.

CONCLUSIONS:

This is the first sham-controlled investigation to demonstrate, in two populations, that VMPFC cTBS can attenuate neural reactivity to drug and alcohol cues in frontostriatal circuits. These results provide an empirical foundation for future clinical trials that may evaluate the efficacy, durability, and clinical implications of VMPFC cTBS to treat addictions.

Keywords: Addiction, Alcohol, Cocaine, Functional connectivity, Neuromodulation, Substance use disorders

Elevated neural reactivity to drug cues is a common feature of substance use disorders (SUDs) and has been evaluated as a potential biomarker for predicting relapse to drug use (1). Across multiple drug-using populations, cue exposure leads to elevated activity in frontostriatal and frontolimbic neural circuits involved in reward processing and salience. These regions include the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), ventral and dorsal striatum, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and anterior insula. This has been demonstrated in cocaine users (2), alcohol users (3), nicotine users (4), marijuana users (5), and opioid users (6).

One promising new area of research in addiction treatment development has been transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Food and Drug Administration–approved as a treatment for depression, TMS is a noninvasive brain stimulation technique that takes advantage of the ability of electromagnetic induction to induce neural activity in the cortex and, by extension, in subcortical regions through monosynaptic afferent projections. Repetitive TMS (rTMS) produces frequency-dependent changes in neural activity, with high-frequency stimulation typically inducing long-term potentiation of cortical excitability and low-frequency stimulation inducing long-term depression of cortical excitability (7). Theta burst stimulation (TBS), a patterned form of rTMS, is based on a rhythmic bursting pattern; it has been used to induce plasticity in preclinical preparations (8,9) and can selectively increase or decrease cortical excitability in a neural circuit–specific manner in humans (10,11).

Prior studies from our lab have shown that single pulses of TMS to the left frontal pole induce a significant change in brain activity (as measured by the blood oxygen level–dependent signal) in the VMPFC and the striatum. This has been demonstrated through the use of interleaved TMS and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in healthy (12), cocaine-dependent (13,14), and alcohol-dependent (13) individuals. Furthermore, when continuous TBS (cTBS), an inhibitory form of rTMS, is applied to the VMPFC in cocaine users (13,15), there is a selective attenuation of TMS-evoked activity in the VMPFC, striatum, ACC, and insula. This paradigm was also associated with a reduction in cocaine craving (15). When VMPFC cTBS is applied to alcohol users, there is also a significant attenuation of neural activity in these regions, suggesting that cTBS has transdiagnostic effects on frontostriatolimbic circuitry.

While VMPFC cTBS appears to attenuate TMS-evoked activity in craving-related circuitry, it is not yet clear, however, if these effects generalize to behaviorally relevant engagement of this circuit, such as during drug/alcohol cue exposure. The goal of the present study was to determine if cTBS to the VMPFC could reduce the brain response to drug cues (experiment 1) and alcohol cues (experiment 2). Additionally, by uniting these datasets, we sought to test the hypothesis that cTBS would have similar (transdiagnostic) attenuating effects on cue reactivity in these groups.

To achieve these goals, we performed two single-blinded, active sham–controlled brain imaging and TMS experiments wherein fMRI scans were acquired immediately before and after a session of real or sham VMPFC cTBS in a cohort of individuals with cocaine use disorder (experiment 1) and alcohol use disorder (experiment 2), respectively. While 600 pulses of cTBS was the original dose observed to produce long-term depression–like effects in the primary motor cortex (8,9), for this study, 3600 pulses was chosen as our cTBS dose given that the Food and Drug Administration–approved protocol for depression treatment involves 3000 pulses/session at 10 Hz (16), and recent studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that 3600 pulses to the left VMPFC can decrease VMPFC connectivity to the ventral striatum, caudate, putamen, and orbitofrontal cortex in cocaine users (15) and alcohol users (13). All individuals received real and sham VMPFC cTBS (across two different sessions, 3600 pulses of cTBS per session; four fMRI scans per individual; 49 participants total; 196 fMRI scans total). We hypothesized that VMPFC cTBS would attenuate drug/alcohol cue–related functional connectivity (FC) within frontostriatal circuitry (VMPFC-ventral striatum, caudate, putamen), as well as nodes of the salience network (i.e., ACC, anterior insula) typically engaged by drug cues.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Experiment 1 (Cocaine Users) and Experiment 2 (Heavy Alcohol Users)

Participants.

Non–treatment-seeking cocaine-dependent individuals (n = 25) and alcohol-dependent individuals (n = 24) were recruited from the Charleston, South Carolina, metropolitan area to participate in one of two single-blinded, active sham–controlled crossover studies. These studies were independent but were run in parallel by the same study coordinator using the same TMS equipment and facilities. Following informed consent procedures approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board, participants completed screening assessments related to MRI and TMS protocol safety, mental status, and drug use to determine study eligibility (see Supplemental Methods for detailed inclusion/exclusion information).

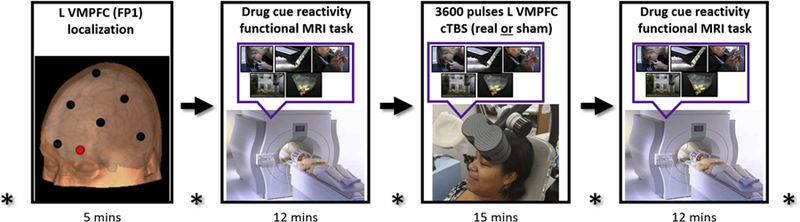

Eligible participants completed two MRI/rTMS visits (each ~1 hour). Before each study session, a multipanel urine drug screen (QuikVue 6-panel urine drug screen; Quidel, San Diego, CA) was given. Participants were told ahead of time that if they had positive urine drug screen for (meth) amphetamine, opiates, marijuana, or benzodiazepines they would not be eligible to participate on that day and that they would have one opportunity to reschedule. In this study, none of the participants had to reschedule for a positive urine drug screen. All participants received both real and sham VMPFC cTBS (one type per session) and were counterbalanced for the order in which they received stimulation (Fp1 landmark based on the International 10–20 system; 110% resting motor threshold [rMT]; six sessions of cTBS for each visit; 3600 pulses total, with a 60-second break after the first 1800 pulses). Visit 2 occurred between 7 and 14 days after visit 1. fMRI drug/alcohol cue reactivity task data were collected immediately before and after cTBS stimulation (Figure 1), with the fMRI scan initiated within 20 minutes of receiving real or sham cTBS and completed no later than 40 minutes after cTBS to maximize presumed effects of cTBS on cortical activity (8). Self-reported cocaine or alcohol craving (respectively) was assessed at five time points: upon visit initiation, before the baseline fMRI scan, before the cTBS session, immediately after cTBS, and after the second fMRI scan.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation visit. All participants received both real and sham ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) (one type per MRI/repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation visit) and were counter-balanced for the order in which they received stimulation (Fp1 landmark based on the International 10–20 system; 110% resting motor threshold; six sessions of cTBS for each visit; 3600 pulses total, with 60-second break after first 1800 pulses). The drug cue reactivity functional MRI task was administered before and after VMPFC cTBS to evaluate cTBS effects on drug-related neural reactivity (functional connectivity) in non–treatment-seeking cocaine users and heavy alcohol users. Self-reported craving was reported at five time points (asterisk) throughout the study visit. L, left.

Procedures: Clinical Assessments.

Self-report assessments included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (17), Timeline Followback [for cocaine, alcohol, marijuana, and nicotine (18)], Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (19), Fagerström Smoking Inventory (20), Beck Depression Inventory-II (21), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (22). Timeline Followback was used to evaluate past week’s substance use at all study visits. As typically done in cue-induced craving studies, study personnel ensured that craving levels were at or below baseline before participants were dismissed from each visit.

Procedures: Drug/Alcohol Cue Reactivity fMRI Task.

The drug/alcohol cue reactivity task that has been used by our group in the past (23,24) was administered in the MRI scanner as a block design using E-Prime 2 software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Sharpsburg, PA). The total task time was 12 minutes and consisted of six 120-second epochs. Each epoch included alternating 24-second blocks of four task conditions: drug, neutral, blur, and rest. Respectively, these task conditions included images of cocaine- or alcohol-related stimuli customized for each group (e.g., crack pipe for cocaine users, liquor bottles for alcohol users), neutral stimuli (e.g., glass of water, cooking utensils, people eating dinner), blurred stimuli acting as visual controls by matching substance images in color and hue, and a fixation cross for alert rest periods. During each task block, five images were presented (4.8 seconds).

Procedures: Neuroimaging Acquisition.

Participants were scanned using a Siemens 3.0T TIM Trio (Siemens Corp., Erlangen, Germany) MRI scanner with a 32-channel head coil. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired using a magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo sequence (repetition time/echo time = 1900 ms/2.34 ms; field of view = 220 mm; matrix = 256 × 256 voxels; 192 slices; slice thickness = 1.0 mm with no gap; final resolution = 1-mm3 voxels). Functional images were acquired with a multislice gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (repetition time/echo time = 2200 ms/35 ms; field of view = 192 mm; matrix = 64 × 64 voxels; 36 slices; slice thickness = 3 mm with no gap; final resolution = 3 mm3 voxels). Each functional run consisted of 328 time points.

Procedures: cTBS Protocol—Real and Sham cTBS.

Coil position was determined using standardized coordinates from the International 10–20 system (with Fp1 corresponding to the left VMPFC stimulation target). The location and orientation of each participant’s coil placement was indicated on a nylon cap that participants wore throughout visit 1 and both MRI/rTMS sessions. Participants’ rMT was identified via the standardized Parametric Estimation by Sequential Testing procedure (25). The cTBS was administered with a figure-of-eight Cool-B65 A/P coil (MagVenture, Farum, Denmark). Participants received two 2-minute trains of cTBS over Fp1 (one train = 120 seconds; three pulse bursts at 5 Hz; 15 pulses/s; 1800 pulses/train; 60-second intertrain interval; 110% rMT) (see Supplemental Methods for details of rigorous active sham). To enhance tolerability, stimulation intensity was gradually escalated in 5% increments (from 80% to 110% rMT) over the first 30 seconds of each train.

Procedures: Cue Recollection During cTBS Administration.

Before cTBS administration, participants were asked to recall the last time they used cocaine or alcohol (respectively) and, using a series of standardized questions from traditional Narrative Exposure Therapy practice (26), they were asked to describe the place they were using, a visual description of the scene, and a description of the sensory properties of the drug including taste, smell, and sensation. During cTBS administration, the participants were primed every 20 seconds to “Think about that scene you described wherein you were last using cocaine/alcohol” (paraphrased so as to be tailored to the participant’s description).

Data Analysis

Self-reported Craving.

Self-reported craving scores were entered into a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (treatment type [real/sham] × time [pre/post]) and subsequent t tests to determine the effect of treatment on changes in craving.

Neuroimaging Preprocessing.

MRI data were preprocessed using standard protocols via SPM12 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, United Kingdom) implemented in MATLAB 7.14 (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) (see Supplemental Methods for preprocessing details). Data analyses were conducted on a total of 49 participants (30 men; mean age = 34 ± 11 years; age range = 21–54 years) (see Table 1 for detailed demographics).

Table 1.

Descriptive Demographic, Clinical, and Drug Use Statistics

| Total Sample (N = 49) | Cocaine Users (n = 25) | Alcohol Users (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Sex | 30 M, 19 F | 13 M, 12 F | 17 M, 7 F |

| Age, years | 34.3 ± 10.6 | 41.6 ± 9.0 | 26.8 ± 5.6 |

| Ethnicity | 29 AA, 20 C | 22 AA, 3 C | 17 C, 7 AA |

| Education, years | 13.5 ± 2.3 | 12.2 ± 1.8 | 14.9 ± 2.0 |

| Substance Use | |||

| Age of first use, years | 19.7 ± 5.8 | 22.6 ± 6.8 | 16.7 ± 1.9 |

| Total duration of use, years | 14.6 ± 9.0 | 19.0 ± 9.8 | 10.0 ± 5.1 |

| Days used in last 30 days | 15.3 ± 7.6 | 12.6 ± 7.5 | 18.2 ± 6.5 |

| Time since last use (at visit), days | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 2.6 |

| Alcohol use severity (AUDIT) | 11.9 ± 5.6 | 9.2 ± 5.3 | 14.2 ± 4.8 |

| Other Substance Use | |||

| Nicotine smoker | 27 (55) | 21 (84) | 6 (25) |

| Nicotine severity (Fagerström) | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 0.4 ± 0.8 |

| MJ smoker | 34 (69) | 18 (72) | 16 (67) |

| Days used MJ in last 30 days | 2.0 ± 6.6 | 6 ± 10.1 | 0.4 ± 0.5 |

| Mental Status | |||

| Depressive symptoms (BDI) | 6.8 ± 8.3 | 10.2 ± 9.7 | 3.3 ± 4.3 |

| State anxiety (STAI-S) | 33.0 ± 12.9 | 36.0 ± 13.3 | 29.9 ± 11.6 |

| Trait anxiety (STAI-T) | 35.5 ± 12.5 | 39.8 ± 12.5 | 31.2 ± 10.9 |

| Treatment-Related Measures | |||

| Scalp-to-cortex distance, mma | 16.9 ± 3.5 | 17.4 ± 3.7 | 16.4 ± 3.2 |

| TMS threshold, %b | 53.3 ± 8.7 | 56.5 ± 9.1 | 49.9 ± 6.7 |

Values represent mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

AA, African American; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; C, Caucasian; F, female; M, male; MJ, marijuana; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

For ventromedial prefrontal cortex coil placement at International 10–20 system Fp1.

Absolute continuous theta burst stimulation dose, percent machine output.

Generalized Psychophysiological Interaction.

Generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) was used to investigate task-modulated patterns of FC between the VMPFC and eight regions of interest (ROIs) during the drug/alcohol cue reactivity task. gPPI was conducted as described by McLaren et al. (27) (see Supplemental Methods for gPPI analysis details). We computed drug/alcohol cue minus neutral cue “contrast betas” indicating the relative FC during drug versus neutral conditions. Four contrast betas were computed: prereal cTBS, postreal cTBS, presham, and postsham. We aimed to show that FC between the VMPFC and several striatal and salience regions would decrease during drug/alcohol cue versus neutral cue exposure following real but not sham VMPFC cTBS. To do this, we conducted a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA involving treatment type (real vs. sham), time (pre vs. post), and ROI as independent variables and drug/alcohol versus neutral contrast betas as the dependent variable. Subsequent t tests were then used to determine the effect of treatment on changes in drug/alcohol cue–evoked FC across regions.

The focus on FC analysis in the present study, rather than traditional general linear model analysis, was due to the nature of TMS effects on the brain. To influence subcortical brain regions (such as the striatum), we applied TMS to cortical targets (such as the VMPFC) and took advantage of the monosynaptic functional connections between cortical and subcortical regions. As such, we felt that measuring the efficacy of the cTBS-induced changes in frontostriatolimbic circuits should be conducted at the level of these functional connections.

Relationship Between Clinical/Demographic Variables and FC Changes.

To determine whether clinical and demographic variables influenced or predicted cTBS treatment outcomes, hierarchical multiple linear regressions were conducted with clinical and demographic variables of interest as the predictors and covariate predictors and changes in VMPFC FC after real versus sham cTBS as the outcome variable.

Scalp-to-Cortex Distance Measurement.

Given that the effects of TMS on cortical depolarization are proportional to the distance between the skull and cortex (28,29), we calculated the distance from the scalp to cortex on the transverse plane of magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo images for each participant using BrainRuler software, a dedicated tool for scalp-to-cortex distance measurements (30). The average distance from participant-specific placement of Fp1 to the cortex was 17.4 ± 3.7 mm for cocaine users and 16.4 ± 3.2 mm for alcohol users. These distances were incorporated into the analyses as covariates.

RESULTS

Experiment 1 Results (Cocaine Users)

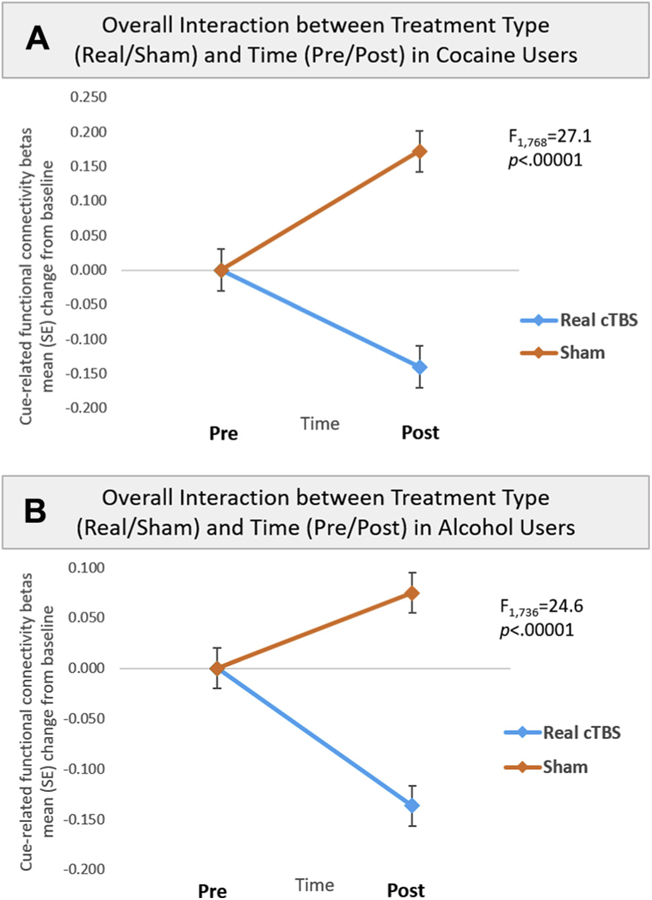

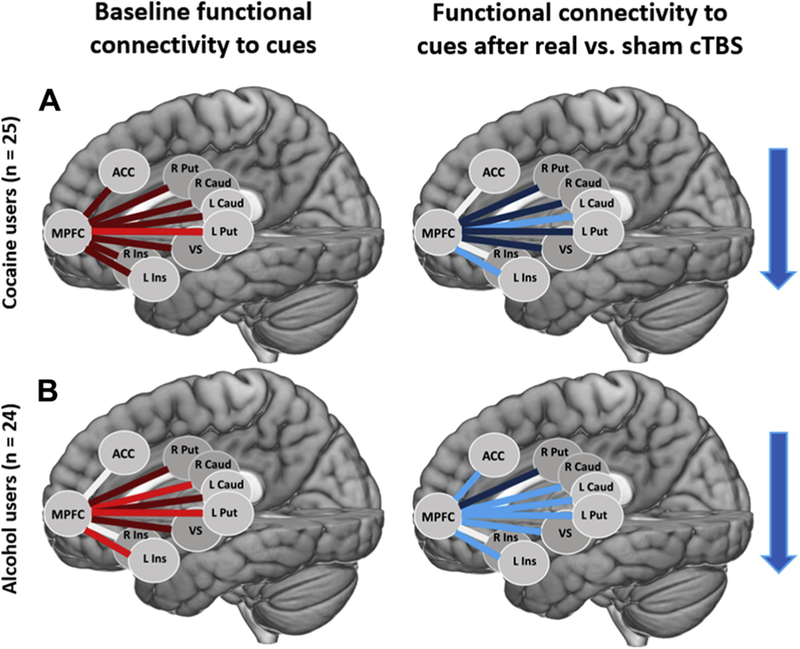

A three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × ROI) revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,768 = 27.1, p < .00001). There was neither a main effect nor an interaction with ROI, indicating a general effect of treatment × time across all ROIs (Figure 2A). A post hoc t test of the interaction revealed that FC for drug versus neutral cues was significantly attenuated following real versus sham cTBS (t24 = −5.25, p < .00001). This significant difference was driven by significant attenuations following real cTBS (t24 = −4.74, p <.00001) as well as significant increases following sham cTBS (t24 = 3.37, p < .001). Although there was no significant effect of ROI, the largest attenuating effects were between the VMPFC and left caudate (effect size: Cohen’s d = −0.50) and left insula (d = −0.70). There were also smaller decreases between the VMPFC and right caudate (d = −0.35), left putamen (d = −0.48), right putamen (d = −0.37), ACC (d = −0.23), and ventral striatum (d = −0.46) (Figure 3A; see Supplemental Figure S1 for interaction plots). In accordance with the generally accepted system for interpreting effect sizes (31), small effect sizes were classified as those with Cohen’s d ≥ 0.20, moderate effect sizes with Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50, and large effect sizes with Cohen’s d ≥ 0.80.

Figure 2.

Significant interaction between treatment type and time. All participants were exposed to a standardized drug cue paradigm customized to their primary drug of abuse (cocaine, alcohol). (A) In experiment 1, cocaine-dependent individuals performed a drug cue reactivity task immediately before and after six sessions (3600 pulses) of real or sham continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) directed at the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (see Methods and Materials). All participants received both real and sham cTBS. (A) For cocaine users, a three-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × region of interest [ROI]) revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,768 = 27.1, p < .00001), but no main effect or interaction with ROI, indicating a general effect of treatment × time across all frontostriatal and frontolimbic ROIs. A post hoc t test of the interaction revealed that functional connectivity (FC) for drug vs. neutral cues was significantly attenuated following real vs. sham cTBS (t24 = −5.25, p < .00001). This significant difference was driven by significant attenuations following real cTBS (t24 = −4.74, p < .00001), as well as significant increases following sham cTBS (t24 = 3.37, p < .001). Panel (A) illustrates FC change from baseline for real (−0.14; blue line) vs. sham (0.17; orange line) cTBS for the frontostriatolimbic circuit. (B) For alcohol users, a three-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × ROI) also revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,736 = 24.6, p < .00001), but no main effect or interaction with ROI, indicating a general effect of treatment × time across all ROIs. A post hoc t test of the interaction revealed that FC for alcohol vs. neutral cues was significantly attenuated following real vs. sham cTBS (t23 = −5.91, false discovery rate p < .00001). This significant difference was driven by significant attenuaions following real cTBS (t23 = −4.70, false discovery rate p < .00001), as well as significant increases following sham cTBS (t23 = 2.81, false discovery rate p < .01). Panel (B) illustrates FC change from baseline for real (−0.14; blue line) vs. sham (0.08; orange line) cTBS for the frontostriatolimbic circuit.

Figure 3.

Drug class–specific treatment-related changes in cue-evoked functional connectivity. (A) At baseline there was greater functional connectivity to drug vs. neutral cues between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and multiple regions. The largest effect size was between the MPFC and left putamen (L Put) (d = 0.55) (left image; bright red lines). There were also smaller effect sizes between the MPFC and left caudate (L Caud) (d = 0.37), right caudate (R Caud) (d = 0.26), right putamen (R Put) (d = 0.30), left insula (L Ins) (d = 0.42), right insula (R Ins) (d = 0.25), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (d = 0.21), and ventral striatum (VS) (d = 0.33) (left image; dark red lines). Following real vs. sham continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS), there was a decrease in functional connectivity to drug vs. neutral cues between the MPFC and several regions. The largest decreases were between the MPFC and left caudate (d = −0.50) and left insula (d = −0.70) (right image; bright blue lines). There were also smaller decreases between the MPFC and right caudate (d = −0.35), left putamen (d = −0.48), right putamen (d = −0.37), ACC (d = −0.23), and VS (d = −0.46) (right image; dark blue lines). (B) In experiment 2, the procedures were replicated in a cohort of alcohol-dependent individuals. At baseline, there was greater functional connectivity to alcohol vs. neutral cues between the MPFC and multiple regions. The largest effect sizes were between the MPFC and right caudate (d = 0.51), left putamen (d = 0.50), and left insula (d = 0.62) (left image; bright red lines). There were also smaller effect sizes between the MPFC and left caudate (d = 0.47), right putamen (d = 0.28), and VS (d = 0.35) (left image; dark red lines). Following real vs. sham cTBS, there was a decrease in functional connectivity to alcohol vs. neutral cues between the MPFC and several regions. The largest decreases were between the MPFC and left caudate (d = −0.50), right caudate (d = −0.60), left putamen (d = −0.65), left insula (d = −0.51), ACC (d = −0.51), and VS (d = −0.54) (right image; bright blue lines). There was also a smaller effect size between the MPFC and right putamen (d = −0.29) (right image; dark blue line). Blue arrows convey overall direction of change in functional connectivity following real vs. sham cTBS.

At baseline, cocaine users showed significantly elevated FC for drug versus neutral cues across all striatal and salience connections with VMPFC (t199 = 4.25, p < .0001, d = 0.30). Although individual connections were not statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparisons, the effect size of elevated baseline FC was largest between the VMPFC and left putamen (d = 0.55). There were also smaller effect sizes between the VMPFC and left caudate (d = 0.37), right caudate (d = 0.26), right putamen (d = 0.30), left insula (d = 0.42), right insula (d = 0.25), ACC (d = 0.21), and ventral striatum (d = 0.33) (Figure 3A).

Changes in cue-evoked FC for real versus sham cTBS was related to several clinical and demographic variables. Change in cue-evoked FC was related to years of cocaine use (for VMPFC-left caudate [r = .63, p < .001]), baseline craving score (for VMPFC-left putamen [r = .58, p < .01]), and trait anxiety score (for VMPFC-left insula [r = .65, p < .001], while controlling for age and scalp-to-cortex distance) (Supplemental Figure S2).

A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (pre/post) on self-reported cocaine craving (F1,96 = 5.65, p = .02), but a nonsignificant effect of treatment or treatment × time (both p ≥ .05). Post hoc paired t tests revealed that self-reported cocaine craving was significantly lower than baseline following real cTBS (t24 = −3.18, p = .004), but not following sham (t24 = −2.07, p ≥ .05). Changes in craving did not correspond to changes in FC.

Experiment 2 Results (Heavy Alcohol Users)

As in experiment 1, a three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × ROI) revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,736 = 24.6, p < .00001), but no effect or interaction with ROI. This indicates a general effect of treatment × time across all ROIs (Figure 2B). A post hoc t test of the interaction revealed that FC for alcohol versus neutral cues was significantly attenuated following real versus sham cTBS (t23 = −5.91, false discovery rate [FDR] p < .00001). This significant difference was driven by significant attenuations following real cTBS (t23 = −4.70, FDR p < .00001), as well as significant increases following sham cTBS (t23 = 2.81, FDR p < .01). Although there was no significant main effect or interaction with ROI, the largest decreases in alcohol cue-evoked FC following real versus sham cTBS were between VMPFC and left caudate (d = −0.50), right caudate (d = −0.60), left putamen (d = −0.65), left insula (d = −0.51), ACC (d = −0.51), and ventral striatum (d = −0.54). There was also a smaller decrease between the VMPFC and right putamen (d = −0.29) (Figure 3B; see Supplemental Figure S3 for interaction plots).

At baseline, alcohol users showed significantly elevated FC for alcohol versus neutral cues across striatal and salience connections with VMPFC (t192 = 5.38, p < .00001, d = 0.39). Baseline functional connections that were significantly elevated for alcohol versus neutral cues included the VMPFC to right caudate (t23 = 2.51, FDR p ≤ .05), left putamen (t23 = 2.43, FDR p ≤ .05), and left insula (t23 = 3.04, FDR p ≤ .05). Effect sizes of elevated baseline FC were largest between the VMPFC and right caudate (d = 0.51), left putamen (d = 0.50), and left insula (d = 0.62), and smaller between the VMPFC and left caudate (d = 0.47), right putamen (d = 0.28), and ventral striatum (d = 0.35) (Figure 3B).

Change in cue-evoked FC for real versus sham cTBS was significantly related to cTBS dose (for VMPFC-left caudate [r = .59, p < .01], VMPFC-right caudate [r = .64, p < .001], and VMPFC-left putamen [r = .48, p < .05], while controlling for age and scalp-to-cortex distance) and scalp-to-cortex distance (for VMPFC-ACC [r = .52, p < .01], while controlling for age) (Supplemental Figure S4).

A two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main or interaction effects of time (pre/post) or treatment (real/sham) on self-reported alcohol craving (all p ≥ .05). Changes in craving did not correspond to changes in FC.

Integration of Data From Experiments 1 and 2

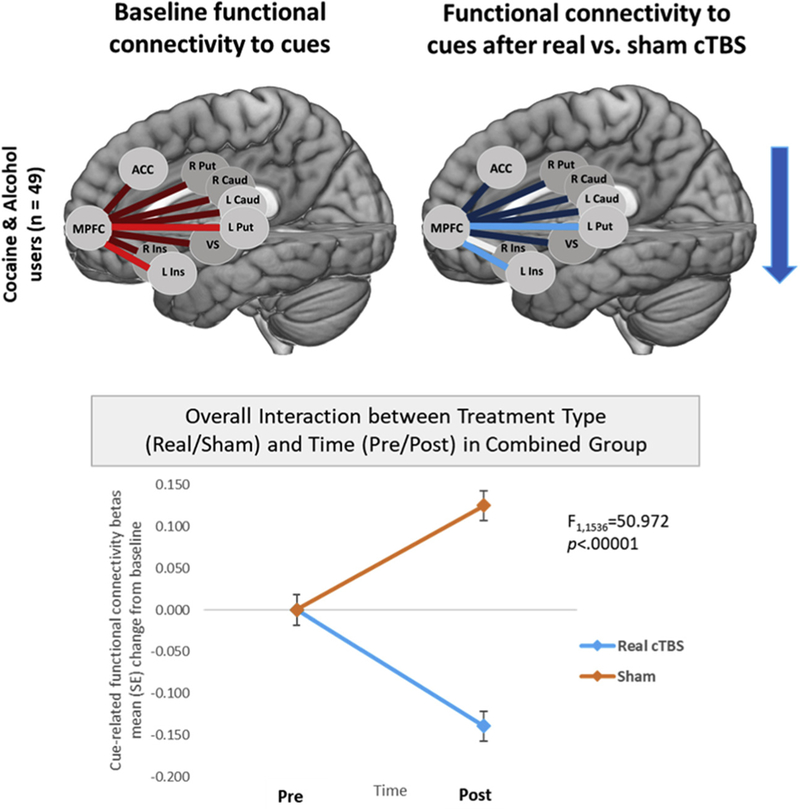

When assessing cocaine and heavy alcohol users together (N = 49), baseline FC for drug versus neutral cues was significantly elevated across all striatal and salience connections with the VMPFC (t391 = 6.59, p < .00001, d = 0.33). Specifically, there was significantly elevated FC between the VMPFC and left caudate, right caudate, left putamen, right putamen, left insula, and ventral striatum (all FDR-corrected p ≤ .05; effect sizes: d = 0.42, 0.37, 0.53, 0.30, 0.53, 0.21, and 0.31, respectively) (Figure 4). A three-way repeated-measures ANOVA (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × ROI) revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,1536 = 50.8, p < .00001), but no main effect or interaction with ROI, indicating a general effect of treatment × time across all ROIs (Figure 4). A post hoc t test of the interaction revealed that FC for drug versus neutral cues was significantly attenuated following real versus sham cTBS (t391 = −7.47, FDR p < .00001). This significant difference was driven by significant attenuations following real cTBS (t391 = −6.67, FDR p < .00001), as well as significant increases following sham cTBS (t391 = 4.26, FDR p < .0001). Although there was no significant main effect or interaction with ROI, effect sizes of the attenuations in alcohol cue–evoked FC following real versus sham cTBS were largest between the VMPFC and left putamen (d = −0.52) and left insula (d = −0.60), and smaller between the VMPFC and left caudate (d = −0.48), right caudate (d = −0.42), right putamen (d = −0.32), ACC (d = −0.30), and ventral striatum (d = −0.42) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Treatment-related changes in cue-evoked functional connectivity for cocaine and alcohol users combined. At baseline for the group, drug cue vs. neutral cue exposure led to elevated functional connectivity between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and several striatal and salience brain regions. The largest effect sizes were between the MPFC and left putamen (L Put) (d = 0.53) and left insula (L Ins) (d = 0.53) (top right image; bright blue lines). There were also smaller effect sizes between the MPFC and left caudate (L caud) (d = 0.42), right caudate (R Caud) (d = 0.37), right putamen (R Put) (d = 0.30), right insula (R Ins) (d = 0.21), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (d = 0.20), and ventral striatum (VS) (d = 0.31) (top right image; dark blue lines). Three-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (treatment [real/sham] × time [pre/post] × region of interest [ROI]) revealed a significant interaction between treatment and time (F1,1536 = 50.8, p < .00001), but no main effect or interaction with ROI, indicating a general effect of treatment × time across all ROIs (bottom image). Although there was no significant main effect or interaction with ROI, effect sizes of the attenuations in drug cue–evoked functional connectivity following real vs. sham continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) were largest between the MPFC and left putamen (d = −0.52) and left insula (d = −0.60) (top left image; bright red lines), and smaller between the MPFC and left caudate (d = 20.48), right caudate (d = −0.42), right putamen (d = −0.32), ACC (d = −0.30), and VS (d = −0.42) (top left image; dark red lines). The blue arrow conveys overall direction of change in functional connectivity following real vs. sham cTBS.

For the group, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (pre/post) on self-reported cocaine craving (F1,184 = 6.56, p = .01), but a nonsignificant effect of treatment or treatment × time (both p ≥ .05). Post hoc paired t tests revealed that self-reported craving was significantly lower than baseline following real cTBS (t48 = −3.32, p = .002), and also following sham cTBS (t46 = −2.97, p = .005). Thus, changes in craving after real cTBS did not significantly differ from sham (t46 = −0.29, p ≥ .05). Furthermore, changes in craving did not correspond to changes in FC.

DISCUSSION

In the last 20 years, both basic and clinical research has demonstrated that frontostriatal circuitry is critical to drug-taking behaviors. With advances in human brain stimulation research, for the first time it is now possible to determine if stimulation of these circuits can change drug cue reactivity. In this paper, we describe two experiments in humans suggesting that noninvasive modulation of the VMPFC can dampen drug cue reactivity in multiple classes of substance-dependent individuals. The data from experiments 1 and 2 demonstrate that a single session of 3600 pulses of cTBS has significant effects on drug cue reactivity in both cocaine users and heavy alcohol users. Additionally, the attenuating effects are greatest in cocaine users with shorter substance use histories and lower levels of craving. Together, these results represent the first set of empirical data demonstrating that it is possible to attenuate drug cue–related neural reactivity through noninvasive attenuation of the VMPFC. Although the effects of a single session of cTBS are likely temporary, these results provide initial proof-of-principle data regarding treatment target engagement. They serve as a foundation for future clinical trials that may evaluate the efficacy, durability, and clinical implications of VMPFC cTBS in cocaine-dependent and alcohol-dependent individuals.

Importance of the Brain as a Biomarker in SUD Treatment Research

The present study is the first to demonstrate that noninvasive brain stimulation can alter drug/alcohol cue–related neural reactivity in humans. Although previous rTMS treatment studies have demonstrated that rTMS to the dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) (32), and the VMPFC (15) can reduce subjective craving, the neural reactivity to drug cues may provide an even more robust and objective marker of relapse risk (33,34). This cue reactivity is of particular importance in the development of treatment for addiction because it has been shown to predict relapse in cocaine (23), alcohol (34–36), nicotine (37,38), and opioid (6) users. These studies have demonstrated that cue-related reactivity in frontostriatolimbic circuitry is a transdiagnostic endophenotype of relapse vulnerability. Hence, neurobiological treatment approaches targeting the neural circuitry related to cue reactivity, such as cTBS to the VMPFC, may provide a direct influence on subsequent cue-induced craving and relapse. Furthermore, neural biomarkers serve as objective and quantifiable measures for evaluating changes associated with treatment beyond what can be gathered from self-report or behavior alone (33,39). In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that is possible to decrease frontostriatolimbic receptivity to drug cues. Further research is necessary to determine if multiple sessions of this intervention will produce a sustainable decrease in cue reactivity and craving and lower relapse risk.

Drug Cue Exposure During cTBS Delivery: Priming the Circuit for Plasticity

Owing to the involvement of frontostriatolimbic regions in processing natural rewards, such as food, sex, and social interaction, it is important to consider the context in which brain stimulation treatment is used to alter this circuit. To target drug/alcohol cue reactivity, we employed a drug cue induction paradigm during TMS sessions as part of the treatment. This enabled us to “mobilize” or prime the circuit before modulation. The use of cues to amplify the neural response to TMS was first demonstrated by Dinur-Klein et al. (40). In their large, parametric study, they demonstrated that rTMS delivered in the presence of a smoking cue produced significantly larger reductions in cigarette use and craving than rTMS delivered without a cue prime. Although the mechanisms through which this priming-associated plasticity occurs are not fully understood, preclinical and clinical research supports the notion that changes in excitability induced by brain stimulation are state dependent, or depend on the history of activation (7). For instance, Muellbacher et al. (41) found that inhibitory rTMS applied directly after motor learning inhibited the expression and maintenance of long-term potentiation in the primary motor cortex. In contrast, a study by Rioult-Pedotti et al. (42) found that inhibitory rTMS given before motor learning produced facilitation in the primary motor cortex. These and other studies suggest that there is an interaction between the neural state and stimulation protocol that is of crucial importance to determining the magnitude and direction of the aftereffects (7). Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the optimal contextual parameters needed to gain specificity of TMS treatment outcomes in addiction.

Importance of VMPFC as a Translationally Relevant Treatment Target

Another important contribution of the present study is that it is the first to investigate the VMPFC as a TMS treatment target for addiction. Most prior studies have focused on stimulating the DLPFC, a hub of the cognitive control circuit that is also dysfunctional in substance-dependent individuals (43). These studies have revealed reductions in craving through either enhancement of the left DLPFC (32,44) or inhibition of the right DLPFC (45,46). However, it is not clear that the DLPFC is the only target for TMS treatment development in addiction. In fact, the VMPFC may provide a more direct target, given its functional and structural connectivity with striatal and limbic regions and known involvement in drug cue reactivity.

Preclinical research provides ample evidence for targeting ventral frontostriatal circuitry as a way to modulate drug self-administration. It is possible to increase or decrease cocaine (47), methamphetamine (48), and heroin (49) seeking in rats through stimulation or inhibition of the infralimbic cortex, a cortical region in the VMPFC. Additionally, it is possible to increase or decrease cocaine self-administration via stimulation or inhibition of the nucleus accumbens, a brain region in the ventral striatum that facilitates reinforced behavior and reward saliency. This has been achieved through optogenetics (50–52) and designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (53,54). These promising preclinical data on ventral frontostriatal stimulation highlight the translational relevance of the VMPFC as a TMS treatment target for addiction.

Differences Across Drug Classes

While these data from two independent experiments point to a common mechanism of response to VMPFC cTBS, we also find that there are differences in predictors of treatment response across the drug classes. While exploratory and in need of replication, we show that in cocaine users TMS treatment response in frontostriatolimbic circuitry is positively related to years of cocaine use, baseline craving, and trait anxiety. In other words, individuals with shorter-term cocaine dependence, lower baseline subjective craving, and lower trait anxiety experience more of a treatment-related attenuation in cue-evoked FC. Therefore, it is possible that individuals with mild-to-moderate clinical symptoms may respond best to the TMS treatment. For alcohol users, TMS treatment response is related to absolute cTBS dose, a measure of the extent of stimulation reaching cortical tissue. Also, while speculative, this could suggest that physical measures relevant to treatment efficacy are greater indicators of treatment response in alcohol users.

Future Directions and Limitations

Despite the strong evidence these data provide in support of being able to temporarily modulate VMPFC with cTBS in patients with substance abuse, these results do not provide direct evidence of clinical effects. Specifically, these experiments were designed to gather data on the basic proof of principle that cTBS to the VMPFC could induce specific decreases in drug/alcohol cue reactivity when rigorously compared with a sham condition in a single-blinded manner. While several clinical parameters were associated with greater efficacy on FC, we did not observe an effect of cTBS on drug/alcohol-induced craving. While craving is endorsed as a key feature of SUDs (as noted by its inclusion in the DSM-5), in human behavioral experiments it is an outcome measure that is often highly variable (55–58) and as such does not in itself indicate lack of potential clinical utility. Given this, the data relevant to a larger clinical trial (including the durability of clinical effects, if they exist) is still unknown. For these same reasons, it is not yet clear if cTBS-related changes in drug/alcohol cue reactivity correspond to real-world changes in drug/alcohol intake. Although there are some studies in nicotine (40,59) and cocaine (60) users that have shown changes in use patterns following excitatory DLPFC TMS, a considerable amount of work needs to be done in this area. For instance, although the duration of neural effects of 3600 pulses of cTBS has not yet been assessed in an imaging study, Chistyakov et al. (61) found that in medication-stabilized depressed patients, 10 sessions of 3600 pulses cTBS to the right DLPFC resulted in a significantly greater reduction of Hamilton depression scores as compared with sham cTBS. Therefore, 3600 pulses of cTBS likely produces long-term depression–like effects on neural circuitry, and the corresponding behavioral effects of cTBS last beyond the time of stimulation. To further address these unknowns, our group is presently conducting the first double-blind, active sham–controlled clinical trial of TMS in treatment-engaged cocaine users, which involves cTBS to the VMPFC over the course of 10 days. Neuroimaging data are collected to evaluate changes in neural circuitry over time, while outcome measures such as urine drug screens are used to evaluate the clinical efficacy on relapse. The present paper provides the initial proof-of-principle data that our current and future clinical trials will use as an empirical foundation.

The lack of effects on subjective ratings of drug/alcohol craving in this study is not altogether unexpected given the resistance of some complex human behaviors to change. All of the studies leading to Food and Drug Administration approval of TMS for treatment-resistant depression involved several weeks of treatment across multiple sessions, with effects on depression emerging only after several sessions [for reviews, see (62,63)]. Studies showing TMS effects on craving in SUDs have also involved multiple treatment sessions (32,40,46,59). This suggests that the effects of TMS on complex behaviors such as craving are likely cumulative. Therefore, while we do not show changes in craving after a single session, it is possible that after a multisession VMPFC cTBS intervention the effects on self-reported craving may emerge—a possibility that will be addressed by our lab’s ongoing multisession clinical trial in cocaine users. Furthermore, there is some criticism of self-report measures, namely of craving, as being less reliable outcome measures when used on their own because they rely on the individual’s definition of cravings/urges as a construct, as well as individuals’ ability to accurately and truthfully verbally convey their internal states (55–58). Instead, biomarkers serve as objective and quantifiable measures of use or relapse risk. As such, in addition to self-report outcome measures, studies should aim to incorporate objective markers that are sensitive to change, such as urine drug screens, as we are now doing in our ongoing clinical trial.

Another limitation of the present study is that despite the diverse samples recruited, exclusion criteria regarding comorbid DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders and other substance dependence limited the ability of our samples to fully portray the incidence of comorbid disorders in typical substance-dependent individuals, namely cocaine users who tend to also drink heavily (64), smoke cigarettes at higher rates (65), and be depressed (66). However, the consistency of our findings between the substance-using groups increases our confidence that the neural response to VMPFC cTBS translates beyond the characteristics of any single drug use class and will generalize to larger populations of drug users.

In this study, we provide the first clear demonstration of the transdiagnostic efficacy of VMPFC TMS to modulate both frontostriatal and salience network circuitry often associated with drug/alcohol craving and relapse. We thus corroborate prior evidence from our lab indicating the VMPFC as a viable TMS (cTBS) treatment target. These findings facilitate the next critical steps in developing inhibitory VMPFC TMS as an innovative, noninvasive neurobiologically targeted intervention in SUDs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. R01DA036617 (to CAH), R21DA041610 (to CAH), P50DA015369 (principal investigator, Peter T. Kalivas), P50AA010761 (principal investigator, Howard Becker), T32DA007288 (LTD; principal investigator, Jakie McGinty), and K05AA017435 (to RFA); and South Carolina Translational Research Institute Grant Nos. UL1TR000062 (principal investigator, Kathleen T. Brady) and R25DA033680 (principal investigator, Antonietta Lavin).

CAH was responsible for the concept and design of the overall research study. OJM and WHD were responsible for study administration and data collection. LTD preprocessed magnetic resonance imaging data. TEK-R designed and executed data analyses, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript. CAH, RFA, and MSG provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for publication.

We thank James Purl and Jayce Doose for assistance in magnetic resonance imaging scanner operation, and Alison Line and Millie Griffith for their assistance with data entry.

ClinicalTrials.gov: The Effects of Theta Burst Stimulation on the Brain Response to Drug and Alcohol Cues (addictionTBS); https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02939352; NCT02939352.

Footnotes

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.03.016.

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sinha R (2011): New findings on biological factors predicting addiction relapse vulnerability. Curr Psychiatry Rep 13:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilts CD, Schweitzer JB, Quinn CK, Gross RE, Faber TL, Muhammad F, et al. (2001): Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schacht JP, Anton RF, Myrick H (2013): Functional neuroimaging studies of alcohol cue reactivity: A quantitative meta-analysis and systematic review. Addict Biol 18:121–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelmann JM, Versace F, Robinson JD, Minnix JA, Lam CY, Cui Y, et al. (2012): Neural substrates of smoking cue reactivity: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neuroimage 60:252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filbey FM, Claus E, Audette AR, Niculescu M, Banich MT, Tanabe J, et al. (2008): Exposure to the taste of alcohol elicits activation of the mesocorticolimbic neurocircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:1391–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q, Li W, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Zhu J, et al. (2015): Predicting subsequent relapse by drug-related cue-induced brain activation in heroin addiction: An event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Addict Biol 20:968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoogendam JM, Ramakers GM, Di Lazzaro V (2010): Physiology of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human brain. Brain Stimul 3:95–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC (2005): Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang YZ, Sommer M, Thickbroom G, Hamada M, Pascual-Leone A, Paulus W, et al. (2009): Consensus: New methodologies for brain stimulation. Brain Stimul 2:2–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunlop K, Hanlon CA, Downar J (2017): Noninvasive brain stimulation treatments for addiction and major depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1394:31–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanlon CA, Canterberry M, Taylor JJ, DeVries W, Li X, Brown TR, George MS (2013): Probing the frontostriatal loops involved in executive and limbic processing via interleaved TMS and functional MRI at two prefrontal locations: A pilot study. PLoS One 8:e67917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanlon CA, Beveridge TJ, Porrino LJ (2013): Recovering from cocaine: Insights from clinical and preclinical investigations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:2037–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanlon CA, Dowdle LT, Correia B, Mithoefer O, Kearney-Ramos T, Lench D, et al. (2017): Left frontal pole theta burst stimulation decreases orbitofrontal and insula activity in cocaine users and alcohol users. Drug Alcohol Depend 178:310–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanlon CA, Dowdle LT, Moss H, Canterberry M, George MS (2016): Mobilization of Medial and lateral frontal-striatal circuits in cocaine users and controls: An interleaved TMS/BOLD functional connectivity study. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:3032–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanlon CA, Dowdle LT, Austelle CW, DeVries W, Mithoefer O, Badran BW, George MS (2015): What goes up, can come down: Novel brain stimulation paradigms may attenuate craving and craving-related neural circuitry in substance dependent individuals. Brain Res 1628:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. (2007): Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 62:1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.First MB, Spritzer RL, Gibbon M (2001): Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis 1 Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobell L, Sobell M (1996): Timeline Follow Back Manual Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babor T, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro M, Maristela G (1992): The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Healthcare WHO Publication No. 92.4. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO (1991): The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A Revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 86:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G (1996): Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory–II San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983): Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prisciandaro JJ, McRae-Clark AL, Myrick H, Henderson S, Brady KT (2014): Brain activation to cocaine cues and motivation/treatment status. Addict Biol 19:240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schacht JP, Anton RF, Randall PK, Li X, Henderson S, Myrick H (2011): Stability of fMRI striatal response to alcohol cues: A hierarchical linear modeling approach. Neuroimage 56:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borckardt JJ, Nahas Z, Koola J, George MS (2006): Estimating resting motor thresholds in transcranial magnetic stimulation research and practice: A computer simulation evaluation of best methods. J ECT 22:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robjant K, Fazel M (2010): The emerging evidence for Narrative Exposure Therapy: A review. Clin Psychol Rev 30:1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Johnson SC (2012): A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): A comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage 61:1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozel FA, Nahas Z, deBrux C, Molloy M, Lorberbaum JP, Bohning D, et al. (2000): How coil-cortex distance relates to age, motor threshold, and antidepressant response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 12:376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokes MG, Barker AT, Dervinis M, Verbruggen F, Maizey L, Adams RC, Chambers CD (2013): Biophysical determinants of transcranial magnetic stimulation: Effects of excitability and depth of targeted area. J Neurophysiol 109:437–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Summers PM, Hanlon CA (2017): BrainRuler-A free, open-access tool for calculating scalp to cortex distance. Brain Stimul 10:1009–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J (1988): Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences New York: Routledge Academic. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Politi E, Fauci E, Santoro A, Smeraldi E (2008): Daily sessions of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the left prefrontal cortex gradually reduce cocaine craving. Am J Addict 17:345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtney KE, Schacht JP, Hutchison K, Roche DJ, Ray LA (2016): Neural substrates of cue reactivity: association with treatment outcomes and relapse. Addict Biol 21:3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schacht JP, Randall PK, Latham PK, Voronin KE, Book SW, Myrick H, Anton RF (2017): Predictors of naltrexone response in a randomized trial: Reward-related brain activation, OPRM1 genotype, and smoking status. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grüsser SM, Wrase J, Klein S, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Ruf M, et al. (2004): Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 175:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinz A, Beck A, Grüsser SM, Grace AA, Wrase J (2009): Identifying the neural circuitry of alcohol craving and relapse vulnerability. Addict Biol 14:108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janes AC, Pizzagalli DA, Richardt S, de Fredrick, Chuzi S, Pachas G, et al. (2010): Brain reactivity to smoking cues prior to smoking cessation predicts ability to maintain tobacco abstinence. Biol Psychiatry 67:722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Versace F, Engelmann JM, Robinson JD, Jackson EF, Green CE, Lam CY, et al. (2014): Prequit fMRI responses to pleasant cues and cigarette-related cues predict smoking cessation outcome. Nicotine Tob Res 16:697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menossi HS, Goudriaan AE, de Azevedo-Marques Périco C, Nicastri S, de Andrade AG, d’Elia G, et al. (2013): Neural bases of pharmacological treatment of nicotine dependence - insights from functional brain imaging: A systematic review. CNS Drugs 27:921–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinur-Klein L, Dannon P, Hadar A, Rosenberg O, Roth Y, Kotler M, Zangen A (2014): Smoking cessation induced by deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal and insular cortices: A prospective, randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 76:742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muellbacher W, Ziemann U, Boroojerdi B, Cohen L, Hallett M (2001): Role of the human motor cortex in rapid motor learning. Exp Brain Res 136:431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rioult-Pedotti MS, Friedman D, Donoghue JP (2000): Learning-induced LTP in neocortex. Science 290:533–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorelick DA, Zangen A, George MS (2014): Transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of substance addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1327:79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Hartwell KJ, Owens M, Lematty T, Borckardt JJ, Hanlon CA, et al. (2013): Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces nicotine cue craving. Biol Psychiatry 73:714–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camprodon JA, Martínez-Raga J, Alonso-Alonso M, Shih MC, Pascual-Leone A (2007): One session of high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the right prefrontal cortex transiently reduces cocaine craving. Drug Alcohol Depend 86:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mishra BR, Nizamie SH, Das B, Praharaj SK (2010): Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in alcohol dependence: A sham-controlled study. Addiction 105:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW (2008): Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci 28:6046–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha A, Kalivas PW (2010): Role of the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens in reinstating methamphetamine seeking. Eur J Neurosci 31:903–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FRM, Cifani C, Koya E, Hope BT, Shaham Y (2011): Ventral medial prefrontal cortex neuronal ensembles mediate context-induced relapse to heroin. Nat Neurosci 14:420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao ZF, Burdakov D, Sarnyai Z (2011): Optogenetics: Potentials for addiction research. Addict Biol 16:519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen BT, Yau HJ, Hatch C, Kusumoto-Yoshida I, Cho SL, Hopf FW, Bonci A (2013): Rescuing cocaine-induced prefrontal cortex hypoactivity prevents compulsive cocaine seeking. Nature 496:359–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stefanik MT, Moussawi K, Kupchik YM, Smith KC, Miller RL, Huff ML, et al. (2013): Optogenetic inhibition of cocaine seeking in rats. Addict Biol 18:50–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bass CE, Grinevich VP, Kulikova AD, Bonin KD, Budygin EA (2013): Terminal effects of optogenetic stimulation on dopamine dynamics in rat striatum. J Neurosci Methods 214:149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cassataro D, Bergfedlt D, Malekian C, Van Snellenberg JX, Thanos PK, Fishell G, Sjulson L (2014): Reverse pharmacogenetic modulation of the nucleus accumbens reduces ethanol consumption in a limited access paradigm. Neuropsychopharmacology 39:283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG (2000): The measurement of drug craving. Addiction 95(suppl 2):S189–S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwarz N (1999): Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. Am Psychologist 54:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drummond DC, Litten RZ, Lowman C, Hunt WA (2000): Craving research: Future directions. Addiction 95(suppl 2):S247–S255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perkins KA (2009): Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence? Addiction 104:1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amiaz R, Levy D, Vainiger D, Grunhaus L, Zangen A (2009): Repeated high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces cigarette craving and consumption. Addiction 104:653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terraneo A, Leggio L, Saladini M, Ermani M, Bonci A, Gallimberti L (2016): Transcranial magnetic stimulation of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces cocaine use: A pilot study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chistyakov AV, Kreinin B, Marmor S, Kaplan B, Khatib A, Darawsheh N, et al. (2015): Preliminary assessment of the therapeutic efficacy of continuous theta-burst magnetic stimulation (cTBS) in major depression: A double-blind sham-controlled study. J Affect Disord 170:225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berlim MT, van den Eynde F, Tovar-Perdomo S, Daskalakis ZJ (2014): Response, remission and drop-out rates following high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treating major depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled trials. Psychol Med 44:225–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaynes BN, Lloyd SW, Lux L, Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Brode S, Jonas DE, et al. (2014): Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 75:477–489, quiz 489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Bryant KJ (1993): Alcoholism in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers: clinical and prognostic significance. J Stud Alcohol 54:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR, Bickel WK (1993): Nicotine and caffeine use in cocaine-dependent individuals. J Subst Abuse 5:117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rounsaville BJ (2004): Treatment of cocaine dependence and depression. Biol Psychiatry 56:803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.