Abstract

Research on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) has largely focused on its activation by various environmental toxins. Consequently, only limited inferences have been made regarding its constitutive activity in the absence of an exogenous ligands. Evidence has shown that AhR is constitutively active in advanced prostate cancer cell lines which model castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC cells can thrive in an androgen depleted environment. However, AR signaling still plays a major role. Although several mechanisms have been suggested for the sustained AR signaling, much is still unknown. Recent studies suggest that crosstalk between constitutive AhR and Src kinase may sustained AR signaling in CRPC. AhR forms a protein complex with Src and plays a role in regulating Src activity. Several groups have reported that tyrosine phosphorylation of AR protein by Src leads to AR activation, thereby promoting the development of CRPC. This review evaluates reports that implicate constitutive AhR as a key regulator of AR signaling in CRPC by utilizing Src as a signaling intermediate.

Keywords: Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor, AR, Src Kinase, Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer, Crosstalk, Phosphorylation

Introduction

Most men who die of prostate cancer present with castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC)1. Androgens and androgen receptor (AR) signaling play a predominant role in male sexual development, growth of the prostate gland and progression of prostate cancer to CRPC2. In CRPC, AR signaling has been shown to be sustained by a variety of mechanisms including increased androgen uptake by prostate cancer cells, increased AR expression, AR gene mutation and activation by other transcription factors3–4. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is a transcription factor that has been extensively studied for its role in mediating the toxic effects of a wide range of environmental toxins. However, recent evidence has shown that AhR possess intrinsic functions independent of activation by an exogenous ligand. Constitutively active AhR has been shown to interact with hormone receptors and may play a role in progression of hormone-related cancers. Particularly, constitutively active AhR interacts with AR and act as a functional transcription unit5, a mechanism that may lead to enhanced AR signaling in CRPC.

Constitutive AhR Signaling

Although AhR has been extensively researched for its role as a xenobiotic receptor; RNA interference, overexpression, and inhibition studies suggest a role for AhR in multiple tumor types beyond activation by environmental contaminants6. As an inactive complex, AhR is found in the cytosol where it interacts with tyrosine kinase c-Src as well as two molecules of HSP90, co-chaperone p23 and immunophilin-like AhR interacting protein (AIP/XAP2)7,8. In its active form, AhR disassociates from its chaperone proteins and dimerizes with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT). The heterodimer activates gene expression through interactions with related xenobiotic responsive elements (XREs) located on Ah- responsive gene promoters9. Studies concerned with the intrinsic functions of AhR have found that overexpression of the receptor may promote carcinogenesis in the absence of a exogenous ligand. AhR protein and mRNA expression is associated with phases of rapid proliferation and differentiation in certain tissues. Conversely, AhR-defective cell lines demonstrate a reduced proliferation rate10. Ectopic over expression of AhR in immortalized normal mammary epithelial cells induced a malignant phenotype with increased growth and acquired invasive capabilities11. A separate study using a constitutively active AhR construct lacking a ligand binding domain revealed that AhR acts as a transcriptional coregulator for the unliganded AR. These studies show that the endogenous AR along with the constitutively active AhR were recruited to androgen-responsive elements to initiate signaling in an androgen depleted environment5.

Ligand Activated AhR Signaling

The aryl hydrocarbon locus includes AhR, ARNT, and the AhR repressor (AHRR), which are critical for regulation of AhR signaling9 in both constitutive and ligand activated signaling. AhR ligands such as 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo- p-dioxin (TCDD), components of cigarette smoke such as benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), and a wide range of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) exert their biological influences by binding directly to the AhR. Following ligand activation, AhR’s primary role is identified as the control of xenobiotic metabolism through cytochrome P450s, some of which are transcriptional targets of AhR13. Activation of AhR by PAHs has been reported to antagonize AR signaling. For example, TCDD has been shown to alter sex steroid hormone secretions. TCDD was also shown to block the androgen dependent proliferation of prostate cancer cells14. Simultaneous activation of AhR and AR with TCDD and an androgen derivative, respectively, decreased AR protein levels15. Thus, activation of AhR by a ligand results in decreased protein expression of both AhR and AR. This action may explain the anti- androgenic actions of a number of PAHs, is distinctive from the effects seen with constitutive AhR signaling that accompanies overexpression of the AhR protein and may be the result of enhanced activity of AhR chaperone protein, Src kinase.

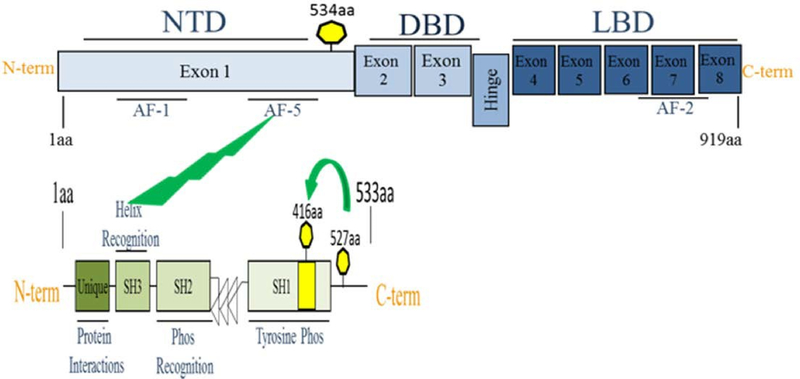

The mammalian AhR protein contains four major structural motifs important in AhR’s interactions with other proteins and transcription factors. The N-terminal basic-helix-loop-helix is the site of DNA binding domain and also participates in dimerization and HSP90 binding. The transactivation domain spans from amino acid 490 to 805 and includes a central glutamine rich region. The two Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domains are named after their homology with the clock protein period (Per), the xenobiotic and oxygen sensing ARNT, and the neuronal cell lineage regulator single-minded (Sim) (Figure 1)16. The PAS domains facilitate interactions with other PAS domain proteins, such as the AhR binding partner, ARNT PAS-A is primarily responsible for protein-protein interaction and PAS-B also encompasses the ligand binding17. cSrc may interact directly with the AhR transactivation and PAS domains7. Western blot and FRET analysis confirm time- dependent phosphorylation of Src following activation of AhR which was blocked in the presence of a specific AhR antagonist18. Furthermore, coimmunopercipitation experiments revealed that AhR regulates Src activity by phosphorylating Src (Tyr 416) and dephosphorylating Src (Tyr527)19.

Figure 1:

The schematic structure of AhR functional domains. The AhR protein contains several domains critical for transcriptional activity. The basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) motif, two Per- Arnt-Sim (PAS) domains (PAS-A and PAS-B) and a glutamine rich transactivation domain (TAD).

Src activity in prostate cancer

The increased expression of Src and other Src family kinases (SFK) in a number of prostate cancer cell lines has suggested a role for Src in prostate cancer initiation and progression20. There are also many reports that SFKs are abnormally activated in prostate cancer cells. SFKs are activated in response to numerous stimuli including neuroendocrine ligands, reactive oxygen species, cytokines and growth factors. These molecules have proven roles in cancer progression, including cell proliferation, adhesion, migration, and invasion21.

Src and AhR coexist in a protein complex that also contains HSP90, AhR-interacting protein, and p23 that aides to maintain an inactive AhR complex8. TCDD activation of AhR results in time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of Src (Tyr416). Reported Src-mediated crosstalk between AhR and EGFR signaling pathways demonstrated an important link between AhR canonical function and TCDD-mediated tumor promotion19,22,23. Through direct physical interaction with AR, Src is able to phosphorylate AR and thereby induce ligand-independent activation of AR, a key mechanisms of CRPC24. Conversely, AR overexpression also plays a role in the oncogenic potential of wild-type Src. This suggests that crosstalk and activation of AR and Src is reciprocal25.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation of AR

AR contains at least sixteen phosphorylated residues. Several of the residues are phosphorylated after treatment of cells with androgen, antiandrogen, or reagents which activate other signaling pathways and alter transcriptional activity, cellular localization, and stability of AR26. As a phosphoprotein, AR has several serine/ threonine and tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated. Most of the phosphorylated residues are located in N-terminal domain that regulates AR cellular localization, stability and its transcriptional activity.

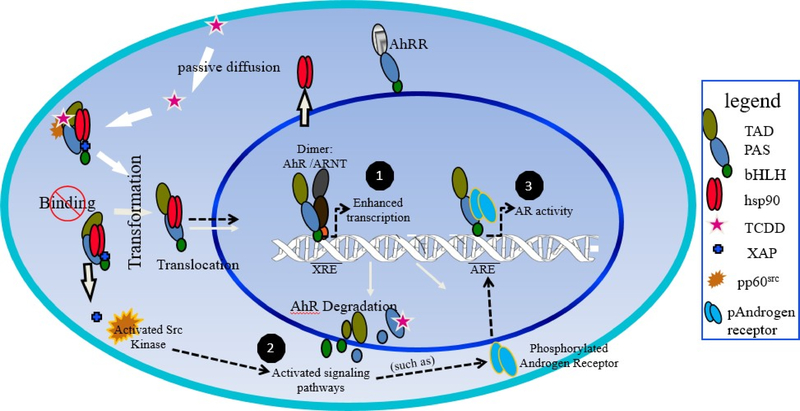

Recently, several groups have reported that tyrosine phosphorylation of AR protein by non- receptor tyrosine kinases Src may have a role in AR activation in the low androgen environment, thereby promoting the development of CRPC. Src-mediated phosphorylation of AR at Y534 resulted in the activation of AR followed by nuclear translocation and DNA binding in the absence of androgens (Figure 2)26–28.

Figure 2:

Schematic structure of Src and AhR interaction and phosphorylation. The AR protein contain an N-terminal domain (NTD); DNA-binding domain (DBD); and ligand-binding domain (LBD). AF-1, AF-5, AF-2 are three known transactivation domains in the AR. The Src molecule AR interacts with the AF-5 domain of AR through the SH3 (helix recognition) domain of cSrc. This interaction occurs following phosphorylation of Tyr416 and dephosphorylating of Tyr527 which is located in a C-terminal regulatory domain.

AR signaling and regulation prostate cancer

AR is a member of the steroid hormone receptor family and shares a similar domain organization with other members of the nuclear receptor (NR) which is primarily responsible for mediating the physiological effects of androgens by binding to AREs29. In the presence of low levels of androgen, AR is normally localized to the cytosol in a complex with molecular chaperones, Hsp40, 70 and 90 in an inactive form. Upon androgen binding, the androgen induces conformational changes in the protein, forms a homodimer, and translocates to the nucleus30. The nuclear translocation results in binding of AR as a transcription factor to ARE’s in the regulatory region of target genes. AR signaling plays a critical role in prostate cancer cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation31.

Several studies based on molecular cloning of AR cDNA, suggest that its transcriptional activity is critical for all stages of prostate cancer development and progression. Several neutral next- generation sequencing platforms have been used to pursue genomic characterization of prostate cancer at various stages. Results have consistently confirmed a critical role for AR activity in prostate cancer progression32.

While AR signaling is known to modulate the expression of genes associated with cell cycle regulation, survival and growth, its specific functions are not fully defined in prostate cancer33. Whole genome sequencing of 11 early onset prostate cancers suggested that androgens, through AR, contribute in shaping somatic alterations34. These results are further supported by studies demonstrating that AR is known to stimulate the expression of TMPRSS2: ERG which is a common gene fusion associated with prostate cancer initiation via androgen-driven overexpression of the gene fusion products35. It is clear that AR signaling plays a critical role in the development and progression of prostate cancer and serves as a central component of progression to CRPC.

Crosstalk between AhR and AR signaling

AhR signaling influences androgen signaling directly at the level of the protein and indirectly through actions on the endocrine system. AhR plays a significant role in sustained AR signaling and growth. However, the mechanism for this role is not clearly understood. One possible mechanism is direct interaction between AhR with AR. AhR has been reported to directly interact with a number of nuclear proteins36–38. Direct heterodimerization of AhR and AR has been shown to occur in cells and may partially explain the crosstalk between the two receptors5. Additionally, interaction can happen via coactivators. AhR and AR share a number of coactivator proteins such as SRC1 and p30039. Another possible mechanism AhR may utilize for AR activation is phosphorylation of AR by Src kinase5,40. Src was shown to mediate crosstalk between AhR and epidermal growth factor receptor in colon cancer cells19. Other studies have shown that Src kinase can promote AR transactivation in C4–2 cells prostate cancer cells. Consequently, inhibition of Src kinase function with a specific inhibitor resulted in decreased AR activation41. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments revealed that AhR forms a protein complex with Src and regulates Src activity by phosphorylating Src (Tyr416) and dephosphorylating Src (Tyr527)19,42. Immunoprecipitation assays also revealed the association of AR with Src, suggesting complex formation among them43.

Conclusion

The precise molecular mechanism utilized by constitutive AhR signaling to activate AR signaling needs to be investigated further and could include induced activation via protein phosphorylation, direct heterodimerization and interacting via coactivators. Extensive in vitro and in vivo studies have established a role for AhR in prostate and prostate cancer development. The development of AhR-null mice has revealed that the function of this receptor is not limited to mediating the effects of PAHs and other ligands44. AhR knockout mice exhibit decreased fertility, decreased liver size, and structural and functional deficits in several tissues45. These include reproductive tract problems such as decreased levels of mature follicles and formation of uric acid stones in the urinary bladder46.

AhR and ARNT are expressed through all stages of male urogenital system development and in the prostate gland. AhR and ARNT genes are expressed in fetal mouse and rat urogenital sinus (UGS) and in normal, hyperplastic, and cancerous adult human prostate tissue47. Ligand activation of AhR by TCDD is adequate to disrupt key stages of ductal morphogenesis. Significantly smaller prostate lobes were observed in rats and mice exposed to TCDD during fetalpubertal development. Indicating that TCDD-induced AhR activation delays prostate growth48. TCDD exposure also led to a decreased number of prostate ducts in monkeys49. AhR may serve as a key regulator of AR signaling in CRPC by utilizing Src as a signaling intermediate. Recent studies have revealed that simultaneous inhibition of AhR and Src is sufficient to abolish AR signaling in CRPC cells50. Activated Src is a common signaling intermediate in a number of pathways including AR signaling pathway and has increased activity in CRPC. Although several mechanisms have been suggested for the sustained AR signaling, tyrosine phosphorylation of AR protein by AhR- activated-Src may have a significant role in CRPC that also exhibit constitutive AhR signaling (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

The proposed pathway for constitutive AhR signaling and crosstalk with Src. (1) Binding of various exogenous and endogenous ligands to the cytoplasmic AhR or deletion of the ligand binding domain stimulates translocation to the nucleus where the AhR/ARNT heterodimer forms. The AhR-ARNT dimer binds to a cognate xenobiotic response element (XRE) to induce transcription of genes important in a wide range of biological processes. (2). AhR forms aprotein complex with Src and regulates Src activity by phosphorylating Src at Tyr416 and dephosphorylating Src at Tyr527. (3) Phosphorylation of AR protein by non-receptor tyrosine kinases Src.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grant: U54MD008621- HU-15000 and DOD Grant: W81XWH-17-1-0274.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013; 63(1): 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan CJ, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor rediscovered: the new biology and targeting the androgen receptor therapeutically. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(27): 3651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linja MJ, Savinainen KJ, Saramaki OR, et al. Amplification and overexpression of androgen receptor gene in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001; 61(9): 3550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saraon P, Jarvi K, Diamandis EP. Molecular alterations during progression of prostate cancer to androgen independence. Clin Chem. 2011; 57(10): 1366–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtake F, Baba A, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, et al. Intrinsic AhR function underlies cross-talk of dioxins with sex hormone signalings. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008; 370(4): 541–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safe Stephen, Lee Syng-Ook, Jin Un-Ho. Role of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Carcinogenesis and Potential as a Drug Target. Toxicol Sci. 2013. September; 135(1): 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enan E, Matsumura F . Identification of c-Src as the integral component of the cytosolic Ah receptor complex, transducing the signal of tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) through the protein phosphorylation pathway. Biochem Pharmacol, 1996; 52(10): 1599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer BK, Petrulis JR, Perdew GH. Aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor levels are selectively modulated by hsp90-associated immunophilin homolog XAP2. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2000; 5(3): 243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu YZ, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000; 40: 519–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Smith R, Safe S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated antiestrogenicity in MCF-7 cells: modulation of hormone-induced cell cycle enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998; 356(2): 239–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks J, Eltom SE. Malignant transformation of mammary epithelial cells by ectopic overexpression of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011; 11(5): 654–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nebert DW, Goujon FM, Gielen JE. Aryl hydrocarbon hydroxylase induction by polycyclic hydrocarbons: simple autosomal dominant trait in the mouse. Nat New Biol. 1972. March 29; 236(65): 107–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poland A, Knutson JC. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons: examination of the mechanism of toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1982; 22(): 517–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karman BN. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and alters sex steroid hormone secretion without affecting growth of mouse antral follicles in vitro. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012; 261(1): 88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow D Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated inhibition of LNCaP prostate cancer cell growth and hormone-induced transactivation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004; 88(1): 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safe S Molecular biology of the Ah receptor and its role in carcinogenesis. Toxicol Lett. 2001; 120(1–3): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacsi SG, Reisz-Porszasz S, Hankinson O. Orientation of the heterodimeric aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor complex on its asymmetric DNA recognition sequence. Mol Pharmacol. 1995; 47(3): 432–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong B, Cheng W, Li W, et al. FRET analysis of protein tyrosine kinase c-Src activation mediated via aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011. April; 1810(4): 427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie G, Peng Z, Raufman JP. Src-mediated aryl hydrocarbon and epidermal growth factor receptor cross-talk stimulates colon cancer cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang YM, Bai L, Liu S, et al. Src family kinase oncogenic potential and pathways in prostate cancer as revealed by AZD0530. Oncogene. 2008. October 23; 27(49): 6365–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virginie Vlaeminck-Guillem, Germain Gillet, and Rimokh Ruth. Src: Marker or Actor in Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness. Front Oncol. 2014; 4: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontillo CA, García MA, Peña D, et al. Activation of c-Src/HER1/ STAT5b and HER1/ERK1/2 signaling pathways and cell migration by hexachlorobenzene in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line. Toxicol Sci. 2011. April; 120(2): 284–96. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randi AS, Sanchez MS, Alvarez L, et al. Hexachlorobenzene triggers AhR translocation to the nucleus, c-Src activation and EGFR transactivation in rat liver. Toxicol Lett. 2008. March 15; 177(2): 116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su B, Gillard B, Gao L, et al. Src controls castration recurrence of CWR22 prostate cancer xenografts. Cancer Med. 2013. December; 2(6): 784–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, et al. Steroid-induced androgen receptor-oestradiol receptor beta-Src complex triggers prostate cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2000. October 16; 19(20): 5406–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Steen Travis, Donald J Tindall, and Haojie Huang. Posttranslational Modification of the Androgen Receptor in Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013. July; 14(7): 14833–14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Z, Dai B, Jiang T, et al. Regulation of androgen receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cancer Cell. 2006; 10: 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraus S, Gioeli D, Vomastek T, et al. Receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) and Src regulate the tyrosine phosphorylation and function of the androgen receptor.Cancer Res. 2006; 66: 11047–11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004; 25: 276–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcelli M, Stenoien DL, Szafran AT, et al. Quantifying effects of ligands on androgen receptor nuclear translocation, intra nuclear dynamics, and solubility. J Cell Biochem. 2006; 98: 770–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei L, Yang Y, Zhang X, et al. Altered regulation of Src upon cell detachment protects human lung adenocarcinoma cells from anoikis. Oncogene. 2004. December 2; 23(56): 9052–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baca SC, Prandi D, Lawrence MS, et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell. 2013; 153: 666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Chen SY, Ross KN, Balk SP, et al. Androgens induce prostate cancer cell proliferation through mammalian target of rapamycin activation and post-transcriptional increases in cyclin D proteins. Cancer Res. 2006. August 1; 66(15): 7783–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weischenfeldt J, Simon R, Feuerbach L, et al. Integrative genomic analyses reveal an androgen-driven somatic alteration landscape in early-onset prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013; 23: 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai C, Wang H, Xu Y, et al. Reactivation of androgen receptor-regulated TMPRSS2:ERG gene expression in castration resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009. August 1; 69(15): 6027–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Datta D, Aftabuddin M, Gupta DK, et al. Human Prostate Cancer Hallmarks Map. Sci Rep. 2016; 6: 30691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saraon P, Jarvi K, Diamandis EP. Molecular alterations during progression of prostate cancer to androgen independence. Clin Chem. 2011; 57(10): 1366–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran Cindy, Richmond Oliver, Aaron LaTayia, et al. Powell. Inhibition of constitutive aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling attenuates androgen independent signaling and growth in (C4–2) prostate cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013. March 15; 85(6): 753–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi A, Numayama-Tsuruta K, Sogawa K, et al. CBP/p300 functions as a possible transcriptional coactivator of Ah receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt). J Biochem 1997; 122: 10–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye M, Zhang Y, Gao H, et al. Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Leads to Resistance to EGFR TKIs in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Activating Src-mediated Bypass Signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2018. March 1; 24(5): 1227–1239. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0396. Epub 2017 Dec 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asim M, Siddiqui IA, Hafeez BB, et al. Src kinase potentiates androgen receptor transactivation function and invasion of androgen independent prostate cancer C4–2 cells. Oncogene 2008; 27: 604–3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beischlag Timothy V, Song Wang, Rose David W, et al. Recruitment of the NCoA/SRC-1/p160 Family of Transcriptional Coactivators by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor/Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator Complex. Molecular and Cellular Biology. June 2002; 4319–4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu J, Akishita M, Eto M, et al. Src kinase-mediates androgen receptor- dependent non-genomic activation of signaling cascade leading to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012. August 3; 424(3): 538–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barouki R, Coumoul X, Fernandez-Salguero PM. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor, more than a xenobiotic-interacting protein.FEBS Lett. 2007. July 31; 581(19): 3608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lahvis GP, Pyzalski RW, Glover E, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor is required for developmental closure of the ductus venosus in the neonatal mouse. Mol Pharmacol. 2005. March; 67(3): 714–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Butler R, Inzunza J, Suzuki H, et al. Uric acid stones in the urinary bladder of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012. January 24; 109(4): 1122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vezina CM, Allgeier SH, Moore RW, et al. Dioxin causes ventral prostate agenesis by disrupting dorsoventral patterning in developing mouse prostate. Toxicol Sci. 2008. December; 106(2): 488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simanainen U, Haavisto T, Tuomisto JT, et al. Pattern of male reproductive system effects after in utero and lactational 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) exposure in three differentially TCDD-sensitive rat lines. Toxicol Sci. 2004. July; 80(1): 101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arima A, Kato H, Ise R, et al. In utero and lactational exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) induces disruption of glands of the prostate and fibrosis in rhesus monkeys. Reprod Toxicol. 2010. June; 29(3): 317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghotbaddini M, Cisse K, Carey A, et al. Simultaneous inhibition of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and Src abolishes and rogen receptor signaling. PLoS One. 2017. July 3; 12(7): e0179844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179844. PMID: 28671964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]