Abstract

Four bis-benzimidazolium salts, 1,4-bis[1′-(N-R-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene 2X– (L1H2·(PF6)2: R = ethyl, X = PF6; L2H2·Br2: R = picolyl, X = Br; L3H2·Br2: R = benzyl, X = Br; and L4H2·Br2: R = allyl, X = Br), and their three N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) Pd(II) and Ag(I) complexes, L1Pd2Cl4 (1), L2Ag2Br2 (2), and L4(AgBr)2 (3), as well as one anionic complex L3H2·(Ag4Br8)0.5 (4), have been synthesized and characterized. Complex 1 adopts a funnel-like type of structure, complex 2 adopts a cyclic structure, and complex 3 is an open structure. In the crystal packing of 1–4, one-dimensional polymeric chains and two-dimensional supramolecular layers are formed via intermolecular weak interactions, including hydrogen bonds, π–π interactions, and C–H···π contacts. The catalytic activities of NHC Pd(II) complex 1 in three types of C–C coupling reactions (Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck–Mizoroki, and Sonogashira reactions) were studied. The results show that this catalytic system is efficient for these C–C coupling reactions.

Introduction

Since the first isolation of the stable imidazol-2-ylidene in 1991,1N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) have attracted considerable attention in the fields of organometallic chemistry and catalysis.2 Over the past two decades, NHC metal complexes have been favored by facile preparation methods and possess high efficiency as catalysts.3 As effective and widely used NHC transfer agents, NHC silver(I) complexes can be applied to prepare other NHC metal complexes (such as Ni, Pd, and Pt) with a diverse structure.4 Besides, biological activities of NHC silver(I) as antimicrobial and anticancer agents have been confirmed.5

Many palladium(II) complexes, such as Pd(II) complexes based on NHC ligands or phosphine ligands, have catalytic activities.6 The carbene carbon atoms of NHC ligands have a strong coordination ability, and they can form stable coordination bonds with metals.7 Therefore, NHC metal complexes have a better stability in air and moisture. One of the main applications of NHC metal complexes is their use as catalysts in some organic reactions.8 In particular, NHC palladium(II) complexes have been demonstrated to be excellent catalysts for some C–C coupling reactions, such as Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck–Mizoroki, and Sonogashira reactions.3,9

We are interested in the structure of NHC metal complexes and the catalytic activities of NHC palladium(II) complexes. In this article, we reported the preparation of four bis-benzimidazolium salts, 1,4-bis[1′-(N-R-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene 2X– (L1H2·(PF6)2: R = ethyl, X = PF6; L2H2·Br2: R = picolyl, X = Br; L3H2·Br2: R = benzyl, X = Br; and L4H2·Br2: R = allyl, X = Br), and the preparation and structures of their three NHC Pd(II) and Ag(I) complexes, L1Pd2Cl4 (1), L2Ag2Br4 (2), and L4(AgBr)2 (3), as well as one anionic complex L3H2·(Ag4Br8)0.5 (4). Particularly, the catalytic activities of NHC Pd(II) complex 1 in Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck–Mizoroki, and Sonogashira reactions were studied.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of Bis-benzimidazolium Salts

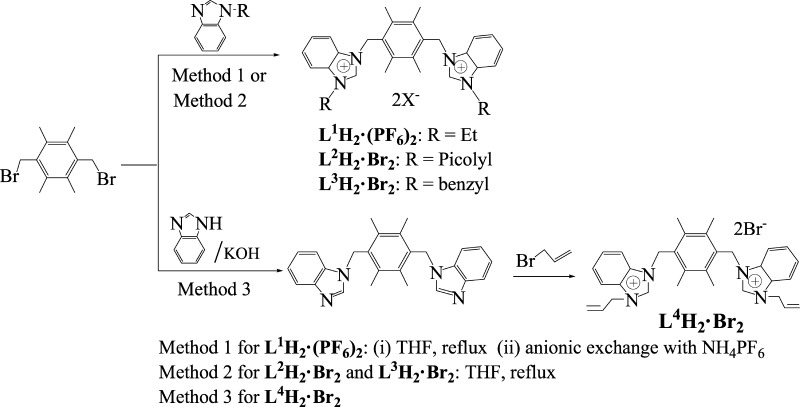

As shown in Scheme 1, 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene as a starting material reacted with N-ethyl-benzimidazole to afford 1,4-bis[1′-(N-ethyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene bromide and subsequent anionic exchange with ammonium hexafluorophosphate was carried out to give 1,4-bis[1′-(N-ethyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene hexafluorophosphate (L1H2·(PF6)2) (method 1). The bis-benzimidazolium salts, L2H2·Br2 and L3H2·Br2, were prepared similar to that of 1,4-bis[1′-(N-ethyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene bromide (method 2 in Scheme 1). L4H2·Br2 was prepared via two-step reactions, as shown in method 3 of Scheme 1. First, 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene reacted with benzimidazole in the presence of KOH to yield 1,4-bis(benzimidazol-l-ylmethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene, and then the product was treated with allyl bromide to yield 1,4-bis[1′-(N-allyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene bromide (L4H2·Br2).

Scheme 1. Preparation of Precursors L1H2·(PF6)2 and L2H2·Br2–L4H2·Br2.

These bis-benzimidazolium salts are stable in air and moisture; soluble in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetonitrile, dichloromethane, and methanol; and scarcely soluble in benzene, diethyl ether, and petroleum ether. In the 1H NMR spectra of bis-benzimidazolium salts, the benzimidazolium proton signals (NCHN) appear at 9.10–10.02 ppm, which are consistent with the chemical shifts of reported benzimidazolium (or imidazolium) salts.10

Synthesis and Characterization of NHC Pd(II) and Ag(I) Complexes 1–3 and Anionic Complex 4

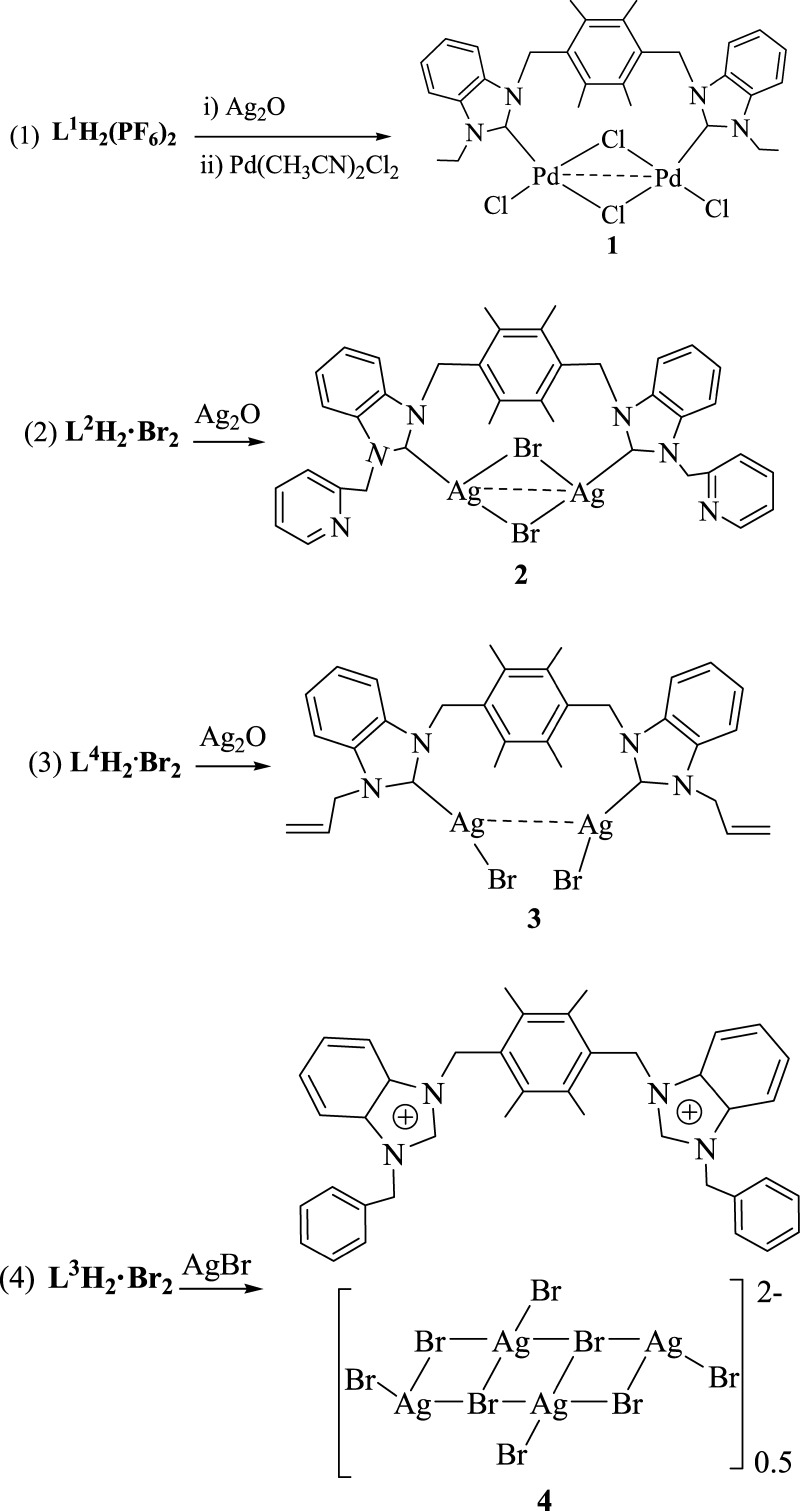

The reaction of L1H2·(PF6)2 with Ag2O in CH3CN under nitrogen atmosphere yielded a pale yellow solution, containing NHC Ag complex. Then, metallic exchange was carried out through the reaction of this solution with 2.0 equiv of Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2, and the resulting mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed to generate a yellow powder of NHC Pd(II) complex L1Pd2Cl4 (1) (Scheme 2-1). L2Ag2Br2 (2) and L4(AgBr)2 (3) were synthesized by the reactions of L2H2·Br2 and L4H2·Br2, respectively, with Ag2O in CH2Cl2 (Scheme 2-2,3). Anionic complex L3H2·(Ag4Br8)0.5 (4) was synthesized by the reaction of L3H2·Br2 with AgBr in CH2Cl2 under refluxing for 24 h (Scheme 2-4).

Scheme 2. Preparation of Complexes 1–4.

The structures of complexes 1–4 were characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, X-ray analyses, and elemental analyses. These complexes are stable in air and moisture, soluble in DMSO, and insoluble in diethyl ether and petroleum ether. In the 1H NMR spectrum of NHC metal complexes 1–3, the resonances for the benzimidazolium protons (NCHN) disappear and the chemical shifts of other protons are similar to those of corresponding precursors. In 13C NMR spectra of NHC Pd(II) complex 1, the signal for the carbene carbon appears at 170.0 ppm, which is analogous to that of the known metal complexes.11 The signals for the carbene carbons in NHC Ag(I) complexes 2 and 3 are invisible. This phenomenon has been reported also for some Ag(I) carbene complexes, which may result from the fuxional behavior of NHC Ag(I) complexes.12 The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra for anionic complex 4 are analogous to those of corresponding precursors.

Crystal Structure of Complexes 1–4

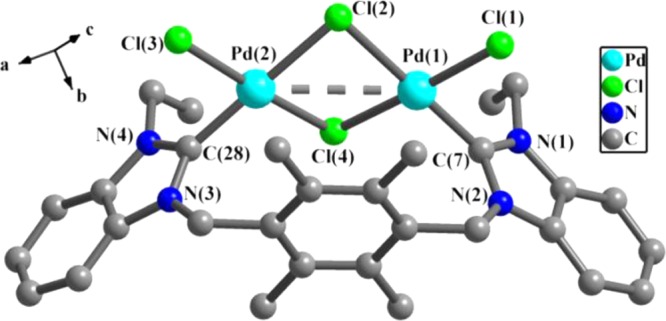

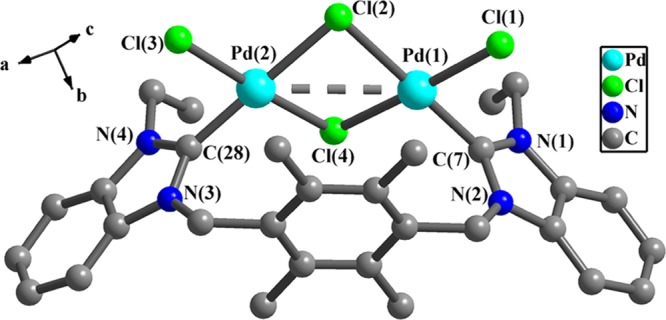

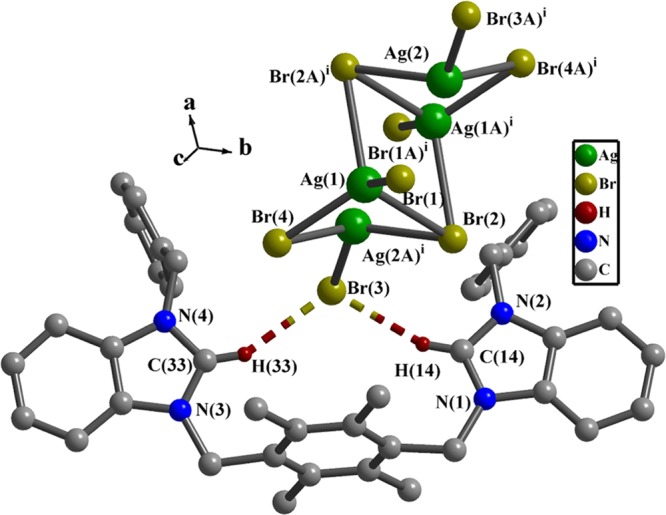

As shown in Figures 1–4, the internal ring angles (N–C–N) at the carbene centers in NHC metal complexes 1–3 are from 105.6(7) to 107.6(5)° and these values are slightly smaller than the corresponding values of anionic complex 4 (110.6(8) and 110.7(7)°). In complexes 1–3, the dihedral angles between two benzimidazole rings are from 3.6(3) to 77.9(8)° and the two benzimidazole rings and 2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene ring form the dihedral angles of 82.5(4)–87.8(4)° (Table S2). In complex 2, the dihedral angles between benzimidazole rings and adjacent pyridine rings are 79.8(4) and 81.5(5)°. In anionic complex 4, two benzimidazole rings are approximately parallel with the dihedral angle of 5.6(1)°, and the dihedral angles between the two benzimidazole rings and 2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene ring are in the range of 77.7(3)–87.8(4)°.

Figure 1.

Perspective view of 1. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): Pd(1)–C(7), 1.952(5); Pd(1)–Cl(1), 2.322(1); Pd(1)–Cl(2), 2.408(1); Pd(1)–Cl(4), 2.385(1); C(7)–Pd(1)–Cl(1), 85.2(1); C(7)–Pd(1)–Cl(4), 94.7(1); Cl(1)–Pd(1)–Cl(4), 175.5(5); C(7)–Pd(1)–Cl(2), 178.6(1); Cl(1)–Pd(1)–Cl(2), 93.9(5); Cl(2)–Pd(1)–Cl(4), 86.1(4); C(28)–Pd(2)–Cl(3), 85.2(1); and N(1)–C(7)–N(2), 107.6(5).

Figure 4.

Perspective view of 4. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): Ag(1)–Br(1), 2.606(1); Ag(1)–Br(2), 2.830(1); C(14)–H(14), 0.930(0); Br(1)–Ag(1)–Br(4), 128.5(7); Br(2)–Ag(1)–Br(4), 108.5(6); Ag(1)–Br(4)–Ag(2A), 72.4(5); N(1)–C(14)–N(2), 111.7(7); and N(3)–C(33)–N(4), 110.6(8).

Analysis of crystal structure of 1 shows that a funnel-like conformation is formed by one bidentate carbene ligand and one Pd2Cl4 unit (Figure 1). Two ethyl groups on two benzimidazole rings point to the same direction. Each Pd(II) ion is tetracoordinated with one carbene carbon atom and three chloride ions. Two Pd(II) ions are linked through two bridging chloride ions (Cl(2) and Cl(4)) to form a noncoplanar Pd2Cl2 pattern, in which the dihedral angle between Pd(1)–Cl(2)–Pd(2) plane and Pd(1)–Cl(4)–Pd(2) plane is 31.3(8)°. The Pd(1)···Pd(2) separation of 3.383(0) Å shows that interactions between two Pd(II) ions (the van der Waals radius of palladium is 2.02 Å) exist.13 The bond angles of C(7)–Pd(1)–Cl(2), Cl(1)–Pd(1)–Cl(4), Pd(1)–Cl(2)–Pd(2), and Pd(1)–Cl(4)–Pd(2) are 178.6(1), 175.5(5), 89.4(4), and 89.9(4)°, respectively. The bond distances of C(7)–Pd(1) and C(28)–Pd(2) are 1.952(5) and 1.941(5) Å, respectively. The Pd(1)–Cl(2) (bridging chloride) distance of 2.408(1) Å is slightly longer than Pd(1)–Cl(1) (terminal chloride) distance of 2.322(1) Å. These values are comparable with those of known NHC Pd(II) complexes.14

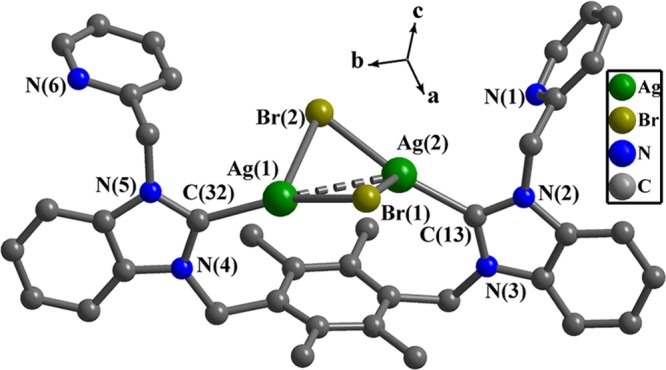

In complex 2, one 13-membered macrometallocycle is formed by one bidentate carbene ligand and one Ag2Br2 unit (Figure 2). Each Ag(I) ion is tricoordinated with one carbon atom and two bridging bromide ions. Two Ag(I) ions are linked by two bridging bromide ions to form a distorted Ag2Br2 quadrangular arrangement. The dihedral angle between Ag(1)–Br(1)–Ag(2) plane and Ag(1)–Br(2)–Ag(2) plane is 51.6(3)°. The bond distances of Ag(1)–C(32) and Ag(2)–C(13) are 2.109(9) and 2.086(9) Å, respectively. The bond distances of Ag–Br are in the range of 2.446(1)–3.084(1) Å. The Ag(1)···Ag(2) separation of 3.256(1) Å shows that interactions between two Ag(I) ions (the van der Waals radius of silver is 2.03 Å) exist.15 The bond angles of two Ag–Br–Ag are 70.1(3) and 74.9(4)°, and the bond angles of two Br–Ag–Br are 91.6(4) and 95.0(4)°.

Figure 2.

Perspective view of 2. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): Ag(1)–C(32), 2.109(9); Ag(1)–Br(2), 2.526(1); Ag(2)–C(13), 2.086(9); Ag(2)–Br(1), 2.446(1); Ag(2)–Br(2), 3.084(3); C(32)–Ag(1)–Br(2), 155.2(2); C(32)–Ag(1)–Br(1), 109.3(2); Br(1)–Ag(1)–Br(2), 95.0(4); C(13)–Ag(2)–Br(1), 163.3(2); C(13)–Ag(2)–Br(2), 104.3(2); Br(1)–Ag(2)–Br(2), 91.6(4); Ag(1)–Br(1)–Ag(2), 74.9(4); Ag(1)–Br(2)–Ag(2), 70.1(3); and N(2)–C(13)–N(3), 105.7(7).

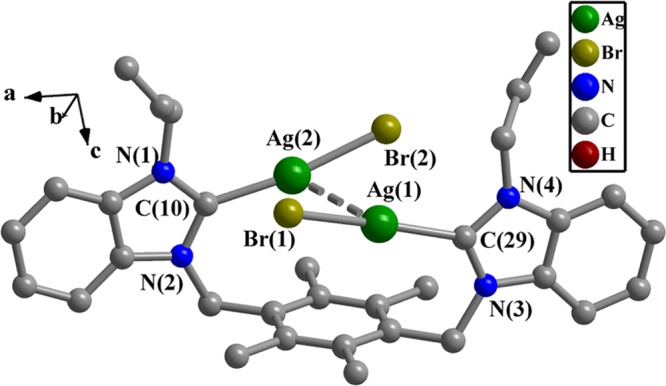

Different from complex 2, each Ag(I) ion in complex 3 possesses a dicoordinated geometry with one carbene carbon atom and one bromide ion (Figure 3). The bond distances of Ag(1)–C(29) and Ag(2)–C(10) are 2.105(4) and 2.092(4) Å, respectively. The arrangements of C(29)–Ag(1)–Br(1) and C(10)–Ag(2)–Br(2) are nearly linear with the bond angles of 168.8(1) and 171.7(1)°, respectively. Two bromide ions point to the opposite directions. The bond distances of Ag(1)–Br(1) and Ag(2)–Br(2) are 2.463(6) and 2.430(6) Å, respectively. The separation between Ag(1) and Ag(2) is 3.273(5) Å, which shows that interactions between two Ag(I) ions exist.

Figure 3.

Perspective view of 3. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): C(29)–Ag(1), 2.105(4); C(10)–Ag(2), 2.092(4); Ag(1)–Br(1), 2.463(6); Ag(2)–Br(2), 2.430(6); C(29)–Ag(1)–Br(1), 168.8(1); C(10)–Ag(2)–Br(2), 171.7(1); and N(1)–C(10)–N(2), 106.1(3).

As shown in Figure 4, the cationic unit ([L3H2]2+) and the anionic unit ([Ag4Br8]0.52–) of complex 4 are connected together via C–H···Br hydrogen bonds16 (the data of hydrogen bonds is given in Table S1). In anionic unit [Ag4Br8]0.52–, Br(2), Br(2A), Br(4), and Br(4A) are bridging bromide ions, and Br(1), Br(1A), Br(3), and Br(3A) are terminal bromide ions. Ag(1) and Ag(1A) are tetracoordinated with four bromide ions, and Ag(2) and Ag(2A) are tricoordinated with three bromide ions. The bond distances of Ag–Br are from 2.542(2) to 2.849(6) Å. The bond angles of Br(1)–Ag(1)–Br(4), Ag(1)–Br(4)–Ag(2A), and Br(2)–Ag(2A)–Br(4) are 128.5(7), 72.4(5), and 96.8(6)°, respectively. The separations between Ag(1)···Ag(2), Ag(1)···Ag(1A), and Ag(1)···Ag(2A) are 3.259(1), 2.943(2), and 3.184(1) Å, respectively, which show that metal–metal interactions between each pair of Ag(I) ions exist.

Catalytic Activity of NHC Pd Complex 1 in Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction

The Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction of aryl halides and arylboronic acids is of general interest in organic synthesis. The Suzuki–Miyaura reaction catalyzed by NHC Pd complexes has become one of the most versatile and powerful tools for the formation of biaryls.17 We chose the cross-coupling reaction of 4-bromotoluene with phenylboronic acid as a model reaction to test the solvent and base effects in air (Table S4). Using water as a solvent and K3PO4·3H2O as a base gave 11% coupling yield at 60 °C in 18 h in air (entry 1). Under the same conditions, use of MeOH as a solvent gave 20% coupling yield (entry 2) and using MeOH/H2O (1:5) as a solvent gave 50% coupling yield (entry 3). However, using MeOH/H2O (5:1) as a solvent gave an excellent coupling yield of 99% (entry 4), and the reason was that the substrates, catalyst, and K3PO4·3H2O could be dissolved effectively in the mixed solvent. Other inorganic bases, like NaHCO3 and KOH, have been tested to lead to relatively poor yields of 11 and 31%, respectively (entries 5 and 6). On the basis of the extensive screening, MeOH/H2O (5:1) and K3PO4·3H2O were proved to be the efficient solvent and base, respectively, with 0.2 mol % complex 1 in air at 60 °C, thus giving the optimal coupling result. The reactions were monitored by gas chromatography (GC) analysis at the appropriate intervals. To further study the influence of ligand on catalysis, the control experiment was performed, in which [PdCl2(CH3CN)2] was added in the absence of precursor L1H2·(PF6)2 under the optimized conditions, and only 49% coupling yield was obtained (entry 7). This result showed that precursor L1H2·(PF6)2 had the preponderant function in the catalytic reactions.

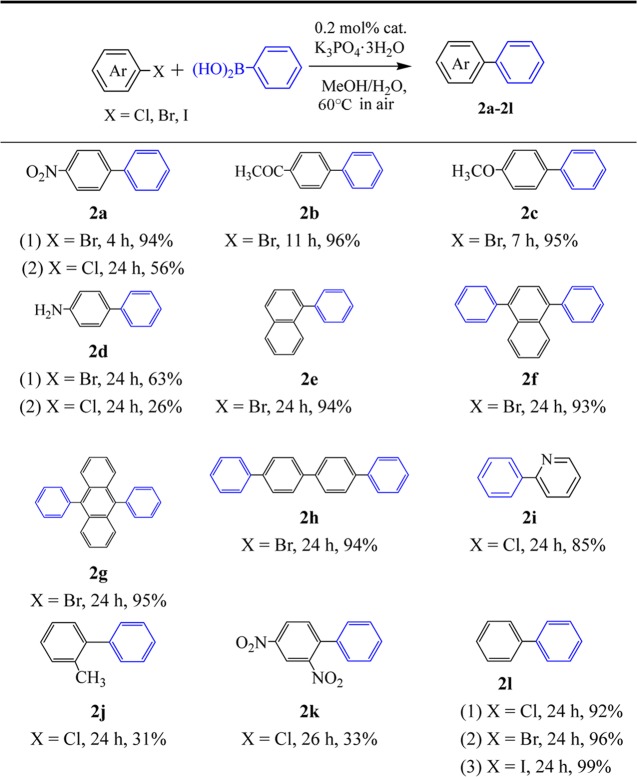

We attempted the cross-coupling reaction of various aryl halides with phenylboronic acid under the optimal reaction conditions (Table 1). In general, complex 1 could catalyze the cross-coupling of various aryl halides with phenylboronic acid to give different yields. The activated aryl bromides with an electron-withdrawing substituent in para-position (such as 4-bromonitrobenzene and 4-bromoacetophenone) could be transformed to the biaryl products with the yields of 94 and 96%, respectively (2a(1) and 2b). The deactivated aryl bromides with an electron-donating substituent (such as 4-bromoanisole) could also be coupled easily with phenylboronic acid to afford a yield of 95% (2c). The coupling reaction of 4-bromoaniline with phenylboronic acid gave a moderate yield of 63% (2d(1)). The coupling reaction of 1-bromonaphthaline and 1-bromobenzene with phenylboronic acid gave a good yield of 94 and 96%, respectively (2e and 2l(2)). The couplings of aryl dibromides (such as 1,4-dibromonaphthalene, 9,10-dibromoanthracene, and 4,4′-dibromobiphenyl) also afforded good yields of 93–95% (2f–h).

Table 1. Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction with Different Aryl Halides Catalyzed by Complex 1a.

Reaction conditions: aryl halide (0.5 mmol), phenylboronic acid (0.6 mmol), K3PO4·3H2O (1.2 mmol), complex 1 (0.2 mol %), MeOH/H2O (5:1, 5 mL), and 60 °C in air.

The catalyst was also effective toward the coupling of aryl chlorides with phenylboronic acid. The coupling reaction of 2-chloropyridine and 4-chloronitrobenzene with phenylboronic acid gave good yields of 85 and 92%, respectively (2i and 2l(1)), whereas the coupling reaction of 4-chloronitrobenzene with phenylboronic acid gave a moderate yield of 56% (2a(2)). The other coupling reactions of aryl chlorides (such as 4-chloroaniline, 2-chlorotoluene, and 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene) with phenylboronic acid gave poor yields of 26–33% (2d(2), 2j, and 2k). The coupling of iodobenzene with phenylboronic acid gave a quantitative yield (2l(3)). The above results showed that complex 1 had high stability to air and MeOH/H2O (5:1), and good tolerance toward various sensitive functional groups, to make it a valuable precatalyst for thermally sensitive substrates. Therefore, it provided an effective phosphine-free catalyst system for facile coupling of aryl halides in MeOH/H2O (5:1) under mild and aerobic conditions. The favorable reaction conditions of this catalytic system for Suzuki–Miyaura reaction are important for the protection of environment and the reduction of cost in the field of fine chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

Catalytic Activity of NHC Pd Complex 1 in Heck–Mizoroki Reaction

The Heck–Mizoroki reaction has evolved significantly from its original mode as the arylation of olefins with aryl iodides, and the reaction has been further developed over the years to allow the coupling of less-reactive bromides, chlorides, and pseudohalides, such as triflates, tosylates, mesylates, and aryl diazonium salts.18 We chose the cross-coupling reaction of bromobenzene with styrene as a model reaction to test the solvent and base effects in air (Table S5). Using 1,4-dioxane as a solvent and K2CO3 as a base gave a trace yield at 110 °C in 12 h (entry 1). Under the same conditions, the addition of 10 mol % tetrabutylamonium bromide (TBAB) gave 85% coupling yield in 12 h (entry 2). This result showed that the reaction could be dramatically improved in the presence of TBAB.19 Under the same conditions as entry 2, the coupling yield of 84% in N2 was obtained (entry 3); thus, the atmosphere did not have an obvious effect on the yield. Other solvents, such as dimethylformamide (DMF) and 1,2-dimethoxyethane, gave moderate yields of 59 and 77%, respectively (entries 4 and 5). The other common and cheap inorganic bases, such as KOH, K3PO4·3H2O, and Na2CO3, were also tested, and led to relatively poor coupling yields of trace—36% (entries 6–8). Besides, with a catalyst loading of 0.25 mol % complex 1 at 110 °C in air, the coupling reaction of bromobenzene with styrene gave a yield of 78%, which showed that the amount of complex 1 had a significant influence on the catalytic activity (entry 9). On the basis of the extensive screening, 1,4-dioxane and K2CO3 were found to be the most efficient solvent and base, respectively, in the presence of 10 mol % TBAB with a catalyst loading of 0.5 mol % complex 1 at 110 °C in air, thus giving the optimal coupling result. To further study the influence of ligand on catalysis, the control experiment was performed, in which [PdCl2(CH3CN)2] and TBAB were added in the absence of L1H2·(PF6)2 under the optimized conditions, and only 38% coupling product was observed. This result showed that ligand L1H2·(PF6)2 had the preponderant function in the catalytic reaction.

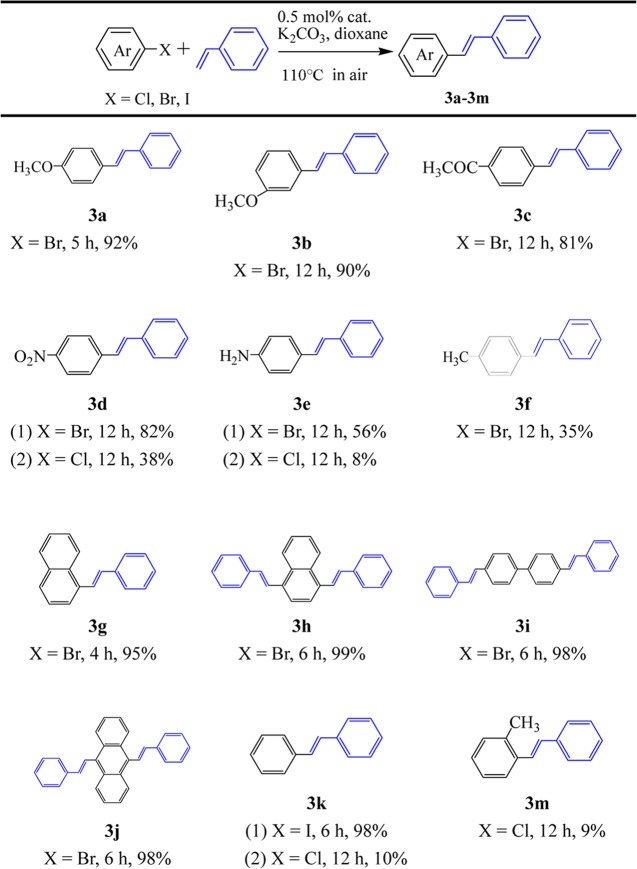

We attempted cross-coupling reactions of various aryl halides with styrene under the optimal reaction conditions (Table 2). The aryl bromides (such as 4-bromoanisole, 3-bromoanisole, 4-bromoacetophenone, and 4-bromonitrobenzene) could be coupled easily with styrene to afford good yields of 81–92% (3a–d(1)). The coupling reaction of 4-bromoaniline and 4-bromotoluene with styrene gave yields of 56 and 35%, respectively (3e(1) and 3f). The coupling of aryl dibromides (such as 1,4-dibromonaphthalene, 4,4′-disbromobiphenyl, and 9,10-dibromoanthracene) with styrene afforded excellent yields of 98–99% (3h–j). The coupling of 1-bromonaphthalene and iodobenzene with styrene afforded yields of 95% in 4 h and 98% in 6 h, respectively (3g and 3k(1)). The coupling of 4-nitrochlorobenzene with styrene gave a yield of 38% (3d(2)). Poor yields (8–38%) were obtained for 4-chloroaniline, 1-chlorobenzene, and 2-chlorotoluene (3e(2), 3k(2), and 3m). The reactions had high selectivity for the trans products in this reaction system, and any corresponding cis products were hardly detected, which could be attributed to trans conformation being a dominant conformation.

Table 2. Heck–Mizoroki Reaction of Aryl Halides with Styrene Catalyzed by Complex 1a.

Reaction conditions: aryl halide (0.5 mmol), styrene (0.75 mmol), K2CO3 (1.0 mmol), complex 1 (0.5 mol %), dioxane (5 mL), TBAB (10 mol %), and 110 °C in air.

Catalytic Activity of NHC Pd Complex 1 in Sonogashira Reaction

4-Bromoanisole and phenylacetylene were used as the coupling partners to test the solvent and base effects under N2 (Table S6). Using DMF as a solvent and Cs2CO3 as a base gave a trace coupling product at 80 °C in 8 h (entry 1). Upon inspection of the literature, we found that Sonogashira reaction needs ancillary catalysts (such as PPh3 and CuI) to be added.20 Under the conditions of DMF as a solvent, Cs2CO3 as a base, and 10 mol % PPh3 and 10 mol % CuI as ancillary catalysts, the yields of 81% in 8 h and 82% in 12 h were obtained (entries 2 and 3), whereas DMSO as a solvent gave the yield of 64% (entry 4). With a catalyst loading of 0.25 mol % complex 1, the coupling reaction gave a yield of 39%, which showed that the amount of complex 1 had a significant influence on the catalytic activity (entry 5). Under the same conditions as entry 2, except N2 protection, only 7% coupling yield was obtained (entry 6). Other common bases, such as K3PO4·3H2O, Et3N, and K2CO3, were also tested and led to relatively poor yields of 23, 8, and 7%, respectively (entries 7–9). On the basis of the extensive screening, DMF and Cs2CO3 were found to be the most efficient solvent and base, respectively, in the presence of 10 mol % PPh3 and 10 mol % CuI as ancillary catalysts with a catalyst loading of 0.5 mol % complex 1 at 80 °C in N2, thus giving the optimal coupling result. To further study the influence of ligand on catalysis, the control experiment was performed, in which [PdCl2(CH3CN)2] and 10 mol % PPh3 and 10 mol % CuI were added in the absence of precursor L1H2·(PF6)2 under the optimized conditions, and only 40% coupling product was obtained (entry 10). This result showed that L1H2·(PF6)2 had large effects on reactions.

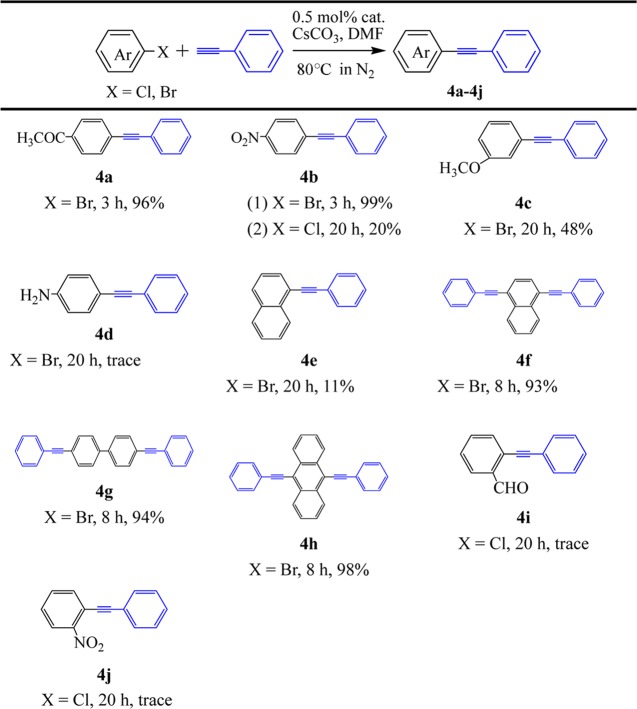

We attempted cross-coupling reactions of various aryl halides with phenylacetylene under the optimal reaction conditions (Table 3). The coupling of activated aryl bromides (such as 4-bromoacetophenone and 4-bromonitrobenzene) with phenylacetylene afforded excellent yields of 96 and 99%, respectively (4a and 4b(1)). The coupling of aryl dibromides (such as 1,4-dibromonaphthalene, 4,4′-disbromobiphenyl, and 9,10-dibromoanthracene) with phenylacetylene also afforded good yields of 93–98% (4f–h). The coupling of 4-chloronitrobenzene, 3-bromoanisole, and 1-bromonaphthalene with phenylacetylene gave relatively poor yields of 11–48% (4b(2), 4c, and 4e), whereas the coupling reactions of 4-bromoaniline, 2-chlorobenzaldehyde, and 2-chloronitrobenzene with phenylacetylene gave trace products (4d, 4i, and 4j).

Table 3. Sonogashira Reaction of Aryl Halides with Phenylacetylene Catalyzed by Complex 1a.

Reaction conditions: aryl halide (0.5 mmol), phenylacetylene (0.75 mmol), Cs2CO3 (1.0 mmol), complex 1 (0.5 mol %), DMF (5 mL), and 80 °C in N2.

Kinetic Studies of Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck–Mizoroki, and Sonogashira Coupling Reactions

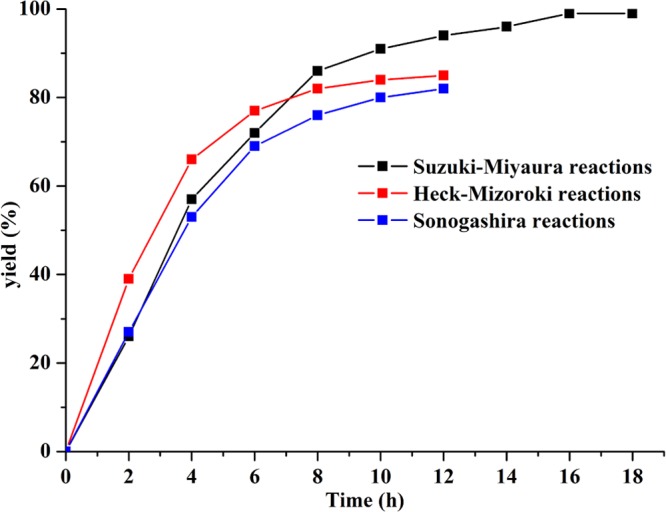

To investigate the mechanisms of reactions, the kinetic experiments of three types of C–C coupling reactions were performed under the optimized conditions (entry 4 in Table S4, entry 2 in Table S5, and entry 3 in Table S6). As shown in Figure 5, no induction periods were observed in these reactions. These reactions proceeded rapidly from the beginning and gave yields of 86% in 8 h for the Suzuki reaction, 77% in 6 h for the Heck reaction, and 69% in 6 h for the Sonogashira reaction. Then, the reactions slowed down and gave the yields of 99% in 18 h, 85% in 12 h, and 82% in 12 h at the end of the reactions, respectively. The experimental results indicated that these reactions were palladacycle reductions during the preactivation stage.21

Figure 5.

Kinetic experiments of Suzuki–Miyaura, Heck–Mizoroki, and Sonogashira coupling reactions with complex 1 under the optimized conditions.

In Hg drop experiments of three types of C–C coupling reactions, when a drop of mercury was added to the reaction mixture before starting the model reactions, the suppressions of three types of coupling reactions were not observed, which further indicated that these reactions are homogeneous.21,22

Conclusions

In summary, a series of bis-benzimidazolium salts, three NHC Pd(II), silver(I), and one anionic complexes have been synthesized and characterized. Analyses of crystal structures show that NHC Pd(II) complex 1 adopts a funnel-like type of structure. NHC Ag(I) complexes 2 and 3 adopt cyclic structure and open structure, respectively. In crystal packings, one-dimensional polymeric chains and two-dimensional supramolecular layers of 1–4 are formed via intermolecular weak interactions, including hydrogen bonds, π–π interactions, and C–H···π contacts. The investigation of catalytic activities of NHC Pd(II) complex 1 in Suzuki–Miyaura reactions shows that complex 1 can catalyze smoothly the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions of most aryl bromides with phenylboronic acid, using MeOH/H2O (5:1) as a solvent and K3PO4·3H2O as a base in air. The tests of complex 1 in Heck–Mizoroki reactions gave good to excellent yields for most aryl bromide derivatives. Likewise, the tests of complex 1 in Sonogashira reactions also gave good yields for most aryl bromide derivatives. Therefore, NHC Pd(II) complex 1 is a valuable precatalyst for the formation of C–C bonds. Further studies on new organometallic compounds from ligands L1H2·(PF6)2, L2H2·Br2–L4H2·Br2 as well as analogous ligands are underway.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

1,4-Bis(bromomethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene23 and N-R-benzimidazole24 were prepared according to the methods in literature. The solvents were purified according to the standard procedures, and Schlenk techniques were used in all manipulations. All commercially available chemicals in the experiments were of reagent grade and used as received. A Boetius Block apparatus was used to determine the melting points of products. A Varian Mercury Vx 400 spectrometer was used to record 1H and 13C NMR spectra at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively. Chemical shifts, δ, were reported in parts per million (ppm) for both 1H and 13C NMR. Coupling constant (J) values were given in hertz (Hz). The elemental analyses were carried out on a PerkinElmer 2400C Elemental Analyzer. A Focus DSQI GC–MS was used, which was equipped with an integrator (C-R8A) with a capillary column (CBP-1 or CBP-5, 0.25 mm i.d. × 40 m).

Preparation of 1,4-Bis[1′-(N-ethyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene Hexafluorophosphate (L1H2·(PF6)2)

L1H2·(PF6)2 was prepared through two steps of reactions. In step 1, a solution of 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene (0.960 g, 3.0 mmol) and N-ethyl-benzimidazole (1.053 g, 7.2 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (60 mL) was stirred for 5 days at 50 °C and a white precipitate of 1,4-bis[1′-(N-ethyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene bromide (L1H2·Br2) was formed. In step 2, NH4PF6 (0.652 g, 4 mmol) was added to a methanol solution (50 mL) of L1H2·Br2 (1.225 g, 2 mmol) and the solution was stirred for 3 days. After filtration, a white precipitate of L1H2·(PF6)2 was obtained. Yield: 1.262 g (85%). mp: 292–294 °C. Anal. Calcd for C30H36P2N4F12: C, 48.52; H, 4.88; N, 7.55%. Found: C, 48.43; H, 4.75; N, 7.62%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.46 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 6H, CH3), 2.27 (s, 12H, CH3), 4.49 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H, CH2), 5.79 (s, 4H, CH2), 7.74 (m, 4H, PhH), 8.13 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.18 (q, J = 2.8 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 9.10 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 140.7 (2-bimiC), 135.6 (PhC), 131.5 (PhC), 131.0 (PhC), 130.1 (PhC), 126.8 (PhC), 126.6 (PhC), 113.9 (PhC), 113.8 (PhC), 46.1 (CH2), 42.2 (CH2), 16.5 (CH3), and 14.6 (CH2CH3) (bimi = benzimidazole).

Preparation of 1,4-Bis[1′-(N-picolyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene Bromide (L2H2·Br2)

This compound was prepared in a manner similar to the step 1 of L1H2·(PF6)2; however, N-picolyl-benzimidazole (2.947 g, 14.1 mmol) was used instead of N-ethyl-benzimidazole. Yield: 4.031 g, (87%). mp: 285–287 °C. Anal. Calcd for C38H40N6Br2: C, 61.62; H, 5.44; N, 11.34%. Found: C, 61.73; H, 5.33; N, 11.45%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.29 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.15 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, CH2), 5.28 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H, CH2), 7.62 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.66 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.74 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.84–7.86 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.87 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.90 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.25 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.42 (q, J = 1.3 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 9.58 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 153.0 (2-bimiC), 149.3 (PhC), 142.0 (PhC), 137.4 (PhC), 135.8 (PhC), 131.6 (PhC), 131.4 (PhC), 130.0 (PhC), 126.9 (PhC), 126.6 (PhC), 123.5 (PyC), 122.4 (PyC), 114.09 (PhC), 114.0 (PhC), 55.9 (CH2), 46.2 (CH2), and 16.5 (CH3).

Preparation of 1,4-Bis[1′-(N-benzyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene Bromide (L3H2·Br2)

This compound was prepared in a manner similar to the step 1 of L1H2·(PF6)2; however, N-benzylbenzimidazole (1.432 g, 6.9 mmol) was used instead of N-ethyl-benzimidazole. Yield: 1.876 g (81%). mp: 228–230 °C. Anal. Calcd for C40H44N4Br2: C, 64.86; H, 5.98; N, 7.56%. Found: C, 64.78; H, 5.82; N, 7.53%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.31 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.86 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 8H, CH2), 7.35 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H, PhH), 7.50 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 4H, PhH), 7.68 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.74 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.26 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 10.02 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 141.2 (2-bimiC), 135.9 (PhC), 134.2 (PhC), 131.7 (PhC), 131.1 (PhC), 129.9 (PhC), 128.8 (PhC), 128.5 (PhC), 127.9 (PhC), 127.0 (PhC), 126.8 (PhC), 114.2 (PhC), 114.0 (PhC), 49.6 (CH2), 46.3 (CH2), and 16.6 (CH3).

Preparation of 1,4-Bis[1′-(N-allyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene Bromide (L4H2·Br2)

A CH3CN (40 mL) suspension of benzimidazole (2.770 g, 23.4 mmol), KOH (1.840 g, 32.8 mmol), and TBAB (0.250 g, 0.77 mmol) was stirred for 1 h under refluxing, and then 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene (3.000 g, 9.8 mmol) was added to the above suspension. The mixture was stirred for 72 h at 80 °C. A pale yellow powder was obtained after evaporating the solvent; subsequently, 100 mL of CH2Cl2 was added to the powder. The solution was washed with water (3 × 100 mL) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After CH2Cl2 was removed, 1,4-bis(benzimidazol-1-ylmethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene was obtained as a white powder.

A solution of 1,4-bis(benzimidazol-l-ylmethyl)-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene (3.000 g, 8.5 mmol) and allyl bromide (2.263 g, 18.7 mmol) in THF (100 mL) was stirred for 3 days under refluxing, and a white precipitate was formed. The white powder of 1,4-bis[1′-(N-allyl-benzimidazoliumyl)methyl]-2,3,5,6-tetramethylbenzene bromide (L4H2·Br2) was obtained by filtration and recrystallization with methanol/ether. Yield: 4.602 g (91%). mp: 262–264 °C. Anal. Calcd for C32H38N4Br2: C, 60.19; H, 5.99; N, 8.77%. Found: C, 60.25; H, 5.82; N, 8.83%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.32 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.83 (s, 4H, CH2), 5.91 (s, 4H, CH2), 5.98 (s, 4H, CH2), 6.04 (m, 2H, = CH), 7.76–7.82 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, PhH), 8.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.24 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 9.58 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 141.0 (2-bimiC), 135.7 (PhC), 135.3 (PhC), 134.9 (PhC), 131.5 (PhC), 131.2 (PhC), 129.9 (PhC), 126.8 (PhC), 126.7 (PhC), 119.8 (PhC), 114.0 (PhC), 48.7 (CH2), 46.0 (CH2), and 16.5 (CH3).

Preparation of L1Pd2Cl4 (1)

The CH3CN (30 mL) suspension of silver oxide (0.151 g, 0.7 mmol) and L1H2·(PF6)2 (0.200 g, 0.3 mmol) was stirred under refluxing for 12 h in N2. After filtration, PdCl2(CH3CN)2 (0.069 g, 0.3 mmol) was added to the filtrate, which was stirred under refluxing for 8 h. The reaction mixture was filtered and condensed to 5 mL. After adding 8 mL of diethyl ether, a yellow powder of L1Pd2Cl4 (1) was obtained via filtering. Yield: 0.133 g (55%). mp: 234–238 °C. Anal. Calcd for C30H34Cl4N4Pd2: C, 44.74; H, 4.25; N, 6.95%. Found: C, 44.52; H, 4.37; N, 6.84%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.59 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.24 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 12H, CH3), 4.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H, CH2), 6.85 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 21H, PhH), 6.99 (d, J = 21.6 Hz, 1H, PhH), 7.14 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.38 (q, J = 9.4 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.76 (q, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H, PhH), and 7.82 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, PhH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 170.0 (Ccarbene), 137.9 (PhC), 133.7 (PhC), 129.2 (PhC), 118.8 (PhC), 113.9 (PhC), 53.1 (CH2), 48.0 (CH2), 16.0 (CH3), and 13.5 (CH2CH3).

Synthesis of L2Ag2Br2 (2)

The suspension of silver oxide (0.065 g, 0.3 mmol) and L2H2·Br2 (0.200 g, 0.3 mmol) in dichloromethane (30 mL) was stirred under refluxing for 12 h in N2. After filtration, the solvent was condensed to 5 mL. After adding 10 mL of diethyl ether, a yellow powder of complex 2 was obtained via filtration. Yield: 0.112 g (42%). mp: 288–290 °C. Anal. Calcd for C38H36Ag2Br2N6: C, 47.92; H, 3.81; N, 8.82%. Found: C, 47.83; H, 3.72; N, 8.75%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.15 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.60 (s, 4H, CH2), 5.72 (s, 4H, CH2), 7.27 (q, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H, PhH), 7.42 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.48 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, PyH), 7.64 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.70 (q, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H, PyH), 8.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, PyH), and 8.47 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, PyH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 155.4 (PhC), 149.3 (PhC), 137.1 (PhC), 135.1 (PhC), 133.4 (PhC), 131.7 (PhC), 124.0 (PhC), 123.6 (PhC), 123.0 (PyC), 121.8 (PyC), 112.1 (PhC), 111.7 (PhC), 54.8 (CH2), 54.4 (CH2), 46.0 (CH2), and 17.1 (CH3).

Synthesis of L4(AgBr)2 (3)

L4H2·Br2 (0.200 g, 0.3 mmol) and silver oxide (0.065 g, 0.3 mmol) were added to 30 mL of dichloromethane and stirred under refluxing for 24 h in N2. After filtration, the solvent condensed to 5 mL. After adding 10 mL of diethyl ether, a pale yellow powder of complex 3 was obtained via filtration. Yield: 0.131 g (48.9%). mp: 241–242 °C. Anal. Calcd for C32H34Ag2Br2N4: C, 45.20; H, 4.03; N, 6.59%. Found: C, 45.32; H, 4.12; N, 6.43%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.19 (s, 12H, CH3), 4.05 (s, 4H, CH2), 6.38 (s, 4H, CH2), 7.45 (s, 2H, = CH), 7.66 (m, 6H, = CH2 or PhH), 8.22 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.37 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 8.85 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 2H, PhH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 135.0 (PhC), 134.2 (PhC), 133.1 (PhC), 133.0 (PhC), 131.7 (PhC), 123.9 (PhC), 123.6 (PhC), 118.6 (PhC), 111.9 (PhC), 111.7 (PhC), 51.7 (CH2), 45.9 (CH2), and 17.2 (CH3).

Preparation of L3H2·(Ag4Br8)0.5 (4)

L3H2·Br2 (0.200 g, 0.4 mmol), silver bromide (0.225 g, 1.2 mmol), and TBAB (0.258 g, 0.8 mmol) were added to dichloromethane (30 mL) and stirred for 24 h under refluxing in N2. After filtration, the solvent was condensed to 5 mL. After adding 10 mL of diethyl ether, complex 4 was obtained as a white powder via filtration. Yield: 0.109 g (44%). mp: 228–230 °C. Calcd for C40H40Ag2Br4N4: C, 43.19; H, 3.62; N, 5.03%. Found: C, 43.30; H, 3.49; N, 5.12%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.31 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.86 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 8H, CH2), 7.39 (q, J = 7.7 Hz, 6H, PhH), 7.52 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H, PhH), 7.70 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.78 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.28 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 10.02 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 141.2 (2-bimiC), 135.9 (PhC), 134.2 (PhC), 131.7 (PhC), 131.1 (PhC), 129.9 (PhC), 128.8 (PhC), 128.5 (PhC), 127.9 (PhC), 127.0 (PhC), 126.8 (PhC), 114.2 (PhC), 114.0 (PhC), 49.6 (CH2), 46.3 (CH2), and 16.6 (CH3). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 2.31 (s, 12H, CH3), 5.86 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 8H, CH2), 7.35 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H, PhH), 7.50 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 4H, PhH), 7.68 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.74 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, PhH), 7.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, PhH), 8.26 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, PhH), and 10.02 (s, 2H, 2-bimiH). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 141.2 (2-bimiC), 135.9 (PhC), 134.2 (PhC), 131.7 (PhC), 131.1 (PhC), 129.9 (PhC), 128.8 (PhC), 128.5 (PhC), 127.9 (PhC), 127.0 (PhC), 126.8 (PhC), 114.2 (PhC), 114.0 (PhC), 49.6 (CH2), 46.3 (CH2), and 16.6 (CH3).

General Method for Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions

In a typical reaction, a mixture of aryl halide (0.5 mmol), phenylboronic acid (0.6 mmol), K3PO4·3H2O (1.2 mmol), complex 1 (0.2 mol %), solvent (5 mL), and 4.2 mL of water was added to a 20 mL flask and stirred at 60 °C in air for the desired time until complete consumption of aryl halide as analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or GC analysis. After the mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, it was extracted by diethyl ether (8 mL × 3). The organic layer was washed with water (8 mL × 3) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. Then, the solution was filtered and concentrated to 2 mL. The solution was analyzed by GC or separated by a column in silica (400 mesh) using n-hexane or n-hexane/dichloromethane (v/v = 10/1) as an eluent. All compounds were subjected to 1H and 13C NMR analyses.

General Method for Heck–Mizoroki Reactions

In a typical reaction, a mixture of aryl halide (0.5 mmol), styrene (0.75 mmol), K2CO3 (1.0 mmol), TBAB (10 mol %), complex 1 (0.5 mol %), and solvent (5 mL) was added to a 20 mL flask. The mixture was stirred at 110 °C in air for the desired time until complete consumption of aryl halide as analyzed by TLC. After the removal of the solvent, water (5 mL) was added to the residue and the mixture was extracted by diethyl ether (10 mL × 3). Organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed, and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (400 mesh) using n-hexane or n-hexane/dichloromethane (v/v = 10/1) as an eluent. All compounds were subjected to 1H and 13C NMR analyses.

General Method for Sonogashira Reactions

In a typical reaction, a mixture of aryl halide (0.5 mmol), phenylacetylene (0.75 mmol), Cs2CO3 (1.0 mmol), PPh3 (10 mol %) and CuI (10 mol %), complex 1 (0.5 mol %), and solvent (5 mL) was added to a 20 mL flask. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C under N2 for the desired time until complete consumption of aryl halide as analyzed by TLC. After the removal of the solvent, water (5 mL) was added to the residue and the mixture was extracted by diethyl ether (10 mL 3 × 3). Organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was removed, and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (400 mesh) using n-hexane or n-hexane/dichloromethane (v/v = 10/1) as an eluent. All compounds were subjected to 1H and 13C NMR analyses.

Hg Drop Test

We chose the cross-coupling reaction of 4-bromotoluene with phenylboronic acid for Suzuki–Miyaura reactions, bromobenzene with styrene for Heck–Mizoroki reactions, and 4-bromoanisole with phenylacetylene for Sonogashira reactions as the model reactions, and then the Hg drop tests were carried out under the optimal conditions for three types of coupling reactions (entry 4 in Table S4, entry 2 in Table S5, and entry 3 in Table S6). When a drop of mercury (300 equiv of mercury to the complex 1) was added to the reaction mixture before starting the model reactions, the suppressions of three types of coupling reactions were not observed.

X-ray Data Collection and Structure Determination

X-ray single-crystal diffraction data for complex 1 were collected by using a Bruker Apex II CCD diffractometer at 296(2) K with Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) by ω scan mode. There was no evidence of crystal decay during data collection in all cases. Semiempirical absorption corrections were applied by using SADABS, and the program SAINT was used for the integration of the diffraction profiles.25 All structures were solved by direct methods using the SHELXS program of the SHELXTL package and refined with SHELXL26 by the full-matrix least-squares methods with anisotropic thermal parameters for all nonhydrogen atoms on F2. Hydrogen atoms bonded to C atoms were placed geometrically, and presumably solvent H atoms were first located in different Fourier maps and then fixed on the calculated sites. Further details of crystallographic data and structural analyses are listed in Tables S1–S3, 4, and 5. Figures were generated using CrystalMaker.27

Table 4. Crystal Data and Structure Refinements for 1 and 2.

| 1 | 2·CH2Cl2 | |

|---|---|---|

| chemical formula | C30H34Cl4N4Pd2 | C38H36Ag2Br2N6·CH2Cl2 |

| Fw | 805.21 | 1037.21 |

| cryst syst | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| space group | P21/c | P21/c |

| a/Å | 20.068(1) | 8.418(6) |

| b/Å | 8.950(6) | 29.944(2) |

| c/Å | 18.140(1) | 15.685(9) |

| α/deg | 90 | 90 |

| β/deg | 106.4(1) | 108.0(3) |

| γ/deg | 90 | 90 |

| V/Å3 | 3124.8(4) | 3759.8(4) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| Dcalcd, mg/m3 | 1.712 | 1.832 |

| abs coeff, mm–1 | 1.520 | 3.348 |

| F(000) | 1608 | 2048 |

| cryst size, mm | 0.28 × 0.25 × 0.18 | 0.15 × 0.14 × 0.13 |

| θmin, θmax, deg | 2.12, 25.00 | 1.93, 25.01 |

| T/K | 296(2) | 173(2) |

| no. of data collected | 15 329 | 18 959 |

| no. of unique data | 5460 | 6595 |

| no. of refined parameters | 366 | 474 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 a | 1.039 | 1.034 |

| final R indicesb [I > 2σ(I)] | ||

| R1 | 0.0400 | 0.0748 |

| wR2 | 0.1128 | 0.1795 |

| R indices (all data) | ||

| R1 | 0.0451 | 0.0795 |

| wR2 | 0.1166 | 0.1822 |

Goof = [∑ω(Fo2 – Fc2)2/(n – p)]1/2, where n is the number of reflections and p is the number of parameters refined.

R1 = ∑(||Fo| – |Fc||)/∑|Fo|; wR2 = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0691P) + 1.4100P], where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3.

Table 5. Summary of Crystallographic Data for 3 and 4.

| 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| chemical formula | C32H34Ag2Br2N4 | C40H40Ag2Br4N4 |

| Fw | 850.19 | 1112.14 |

| cryst syst | monoclinic | triclinic |

| space group | P21/c | P1̅ |

| a/Å | 13.047(1) | 11.398(3) |

| b/Å | 12.577(1) | 13.023(3) |

| c/Å | 18.214(1) | 18.513(4) |

| α/deg | 90 | 100.1(4) |

| β/deg | 90.5(1) | 103.8(4) |

| γ/deg | 90 | 110.9(4) |

| V/Å3 | 2988.8(4) | 2385.5(1) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| Dcalcd, mg/m3 | 1.889 | 1.548 |

| abs coeff, mm–1 | 4.013 | 4.199 |

| F(000) | 1672 | 1084 |

| cryst size, mm | 0.15 × 0.14 × 0.13 | 0.25 × 0.22 × 0.20 |

| θmin, θmax, deg | 1.97, 25.01 | 1.75, 25.03 |

| T/K | 173(2) | 296(2) |

| no. of data collected | 14 879 | 12 321 |

| no. of unique data | 5263 | 8359 |

| no. of refined parameters | 365 | 454 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2a | 1.040 | 1.043 |

| final R indicesb [I > 2σ(I)] | ||

| R1 | 0.0314 | 0.0853 |

| wR2 | 0.0733 | 0.2532 |

| R indices (all data) | ||

| R1 | 0.0423 | 0.1235 |

| wR2 | 0.0782 | 0.2919 |

Goof = [∑ω(Fo2 – Fc2)2/(n – p)]1/2, where n is the number of reflections and p is the number of parameters refined.

R1 = ∑(||Fo| – |Fc||)/∑|Fo|; wR2 = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0691P) + 1.4100P], where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21572159) and Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (No. 11JCZDJC22000).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00205.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arduengo A. J.; Harlow R. L.; Kline M. A stable crystalline carbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 361–363. 10.1021/ja00001a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Herrmann W. A. N-heterocyclic carbenes: a new concept in organometallic catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1290–1309. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Marion N.; Nolan S. P. Well-defined N-heterocyclic carbenes-palladium(II) precatalysts for cross-coupling reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1440–1449. 10.1021/ar800020y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hahn F. E.; Jahnke M. C. Heterocyclic carbenes: synthesis and coordination chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3122–3172. 10.1002/anie.200703883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Díez-González S.; Nolan S. P. Stereoelectronic parameters associated with N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands: A quest for understanding. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 874–883. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Liu B.; Xu D.; Chen W. Z. Facile synthesis of metal N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2883–2885. 10.1039/c0cc05260d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Xia Y.; Qiu D.; Wang J. B. Transition-metal-catalyzed cross-couplings through carbene migratory insertion. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13810–13889. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Zhong R.; Lindhorst A. C.; Groche F. J.; Kühn F. E. Immobilization of N-heterocyclic carbene compounds: a synthetic perspective. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 1970–2058. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Zhang C. H.; Hooper J. F.; Lupton D. W. N-Heterocyclic carbene catalysis via the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2583–2596. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Sinha N.; Hahn F. E. Metallosupramolecular architectures obtained from poly-N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2167–2184. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Charra V.; de Fremont P.; Braunstein P. Multidentate N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of the 3d metals: Synthesis, structure, reactivity and catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 341, 53–176. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Zhao W. H.; Ferro V.; Baker M. V. Carbohydrate-N-heterocyclic carbene metal complexes: synthesis, catalysis and biological studies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 339, 1–16. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Samojłowicz C.; Bieniek M.; Grela K. Ruthenium-based olefin metathesis catalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3708–3742. 10.1021/cr800524f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hahn F. E.; Jahnke M. C.; Pape T. Synthesis of pincer-type bis(benzimidazolin-2-ylidene) palladium complexes and their application in C-C coupling reactions. Organometallics 2007, 26, 150–154. 10.1021/om060882w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zinner S. C.; Rentzsch C. F.; Herdtweck E.; Herrmann W. A.; Kühn F. E. N-Heterocyclic carbenes of iridium(I): ligand effects on the catalytic activity in transfer hydrogenation. Dalton Trans. 2009, 7055–7062. 10.1039/b906855d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Heravi M. M.; Heidari B.; Ghavidel M.; Ahmadi T. Non-conventional green strategies for NHC catalyzed carbon-carbon coupling reactions. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 2249–2313. 10.2174/1385272821666170410103712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Zhao D. B.; Candish L.; Paul D.; Glorius F. N-Heterocyclic carbenes in asymmetric hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5978–5988. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Anna V. R.; Pallepogu R.; Zhou Z. Y.; Kollipara M. R. Novel platinum group metal complexes bearing bidentate chelating pyrimidyl-NHC and pyrimidyl imidazolyl-thione ligands: syntheses, spectral and structural characterization. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 387, 37–44. 10.1016/j.ica.2011.12.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lin I. J. B.; Vasam C. S. Preparation and application of N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of Ag(I). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 642–670. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Coleman K. S.; Chamberlayne H. T.; Turberville S.; Gren M. L. H.; Cowley A. R. Silver(I) complex of a new imino-N-heterocyclic carbene and ligand transfer to palladium(II) and rhodium(I). Dalton Trans. 2003, 2917–2922. 10.1039/B304474B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Liu Q. X.; Zhao L. X.; Zhao X. J.; Zhao Z. X.; Wang Z. Q.; Chen A. H.; Wang X. G. Silver(I), palladium(II) and mercury(II) NHC complexes based on bisbenzimidaz ole salts with mesitylene linker: synthesis, structural studies and catalytic activity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 731, 35–48. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Herrmann W. A.; Schneider S. K.; Ofele K.; Sakamoto M.; Herdtweck E. First silver complexes of tetrahydropyrimid-2-ylidenes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 689, 2441–2449. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Wang H. M. J.; Lin I. J. B. Facile synthesis of silver(I)-carbene complexes. Useful carbene transfer agents. Organometallics 1998, 17, 972–975. 10.1021/om9709704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Wang J. W.; Song H. B.; Li Q. S.; Xu F. B.; Zhang Z. Z. Macrocyclic dinuclear gold(I) and silver(I) NHCs complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 3653–3658. 10.1016/j.ica.2005.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Seva L.; Hwang W. S.; Sabiah S. Palladium biphenyl N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: synthesis, structure and their catalytic efficiency in water mediated Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2016, 418–419, 125–131. 10.1016/j.molcata.2016.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Haque R. A.; Ghdhayeb M. Z.; Budagumpi S.; Ahamed M. B. K.; Majid A. M. S. A. Synthesis, crystal structures, and in vitro anticancer properties of new N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) silver(I)- and gold(I)/(III)-complexes: a rare example of silver(I)-NHC complex involved in redox transmetallation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 60407–60421. 10.1039/C6RA09788J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mercs L.; Albrecht M. Beyond catalysis: N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as components for medicinal, luminescent, and functional materials applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1903–1912. 10.1039/b902238b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kascatan-Nebioglu A.; Panzner M. J.; Tessier C. A.; Cannon C. L.; Youngs W. J. N-Heterocyclic carbene-silver complexes: a new class of antibiotics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 884–895. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Siciliano T. J.; Deblock M. C.; Hindi K. M.; Durmus S.; Panzner M. J.; Tessier C. A.; Youngs W. J. Synthesis and anticancer properties of gold(I) and silver(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 1066–1071. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.10.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wright B. D.; Shah P. N.; McDonald L. J.; Shaeffer M. L.; Wagers P. O.; Panzner M. J.; Smolen J.; Tagaev J.; Tessier C. A.; Cannon C. L.; Youngs W. J. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver carbene complexes derived from 4,5,6,7-tetrachlorobenzimidazole against antibiotic resistant bacteria. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 6500–6506. 10.1039/c2dt00055e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Gök Y.; Akkoç S.; Albayrak S.; Akkurt M.; Tahir M. N. N-Phenyl-substituted carbene precursors and their silver complexes: synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 28, 244–251. 10.1002/aoc.3116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Panzner M. J.; Deeraksa A.; Smith A.; Wright B. D.; Hindi K. M.; Kascatan-Nebioglu A.; Torres A. G.; Judy B. M.; Hovis C. E.; Hilliard J. K.; et al. Synthesis and in vitro efficacy studies of silver carbene complexes on biosafety level 3 bacteria. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 1739–1745. 10.1002/ejic.200801159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Asekunowo P. O.; Haque R. A.; Razali M. R. A comparative insight into the bioactivity of mono- and binuclear silver(I)-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: synthesis, lipophilicity and substituent effect. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 37, 29–50. 10.1515/revic-2016-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Kaloğlu N.; Özdemir I.; Günal S.; Özdemir I. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of bulky 3,5-di-tert-butyl substituent-containing silver-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 31, e3803 10.1002/aoc.3803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Johnson N. A.; Southerland M. R.; Youngs W. J. Recent developments in the medicinal applications of silver-NHC complexes and imidazolium salts. Molecules 2017, 22, 1263. 10.3390/molecules22081263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Marinelli M.; Santini C.; Pellei M. Recent advances in medicinal applications of coinage-metal (Cu and Ag) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 2995–3017. 10.2174/1568026616666160506145408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li F. W.; Bai S. Q.; Hor T. S. A. Benzenimidazole-functionalized imidazolium-based N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of silver(I) and palladium(II): isolation of a Ag3 intermediate toward a facile transmetalation and Suzuki coupling. Organometallics 2008, 27, 672–677. 10.1021/om700949s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Froese R. D. J.; Lombardi Cr; Pompeo M.; Rucker R. P.; Organ M. G. Designing Pd-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes for high reactivity and selectivity for cross-coupling applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2244–2253. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Leone A. K.; McNeil A. J. Matchmaking in catalyst-transfer polycondensation: optimizing catalysts based on mechanistic insight. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2822–2831. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Boehme C.; Frenking G. Electronic structure of stable carbenes, silylenes, and germylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2039–2046. 10.1021/ja9527075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Viciu M. S.; Navarro O.; Germaneau R. F.; Kelly R. A.; Sommer W.; Marion N.; Stevens E. D.; Cavallo L.; Nolan S. P. Synthetic and structural studies of (NHC)Pd(allyl)Cl complexes (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene). Organometallics 2004, 23, 1629–1635. 10.1021/om034319e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Wang F. J.; Liu L. J.; Wang W. F.; Li S. K.; Shi M. Chiral NHC-metal-based asymmetric catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 804–853. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Valyaev D. A.; Willot J.; Mangin L. P.; Zargarian D.; Lugan N. Manganese-mediated synthesis of an NHC core non-symmetric pincer ligand and evaluation of its coordination properties. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 10193–10196. 10.1039/C7DT02190A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Stylianides N.; Danopoulos A.; Pugh D.; Hancock F.; Zanotti-Gerosa A. Cyclometalated and alkoxyphenyl-substituted palladium imidazolin-2-ylidene complexes. Synthetic, structural, and catalytic studies. Organometallics 2007, 26, 5627–5635. 10.1021/om700603d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kantchev E. A. B.; O’Brien C. J.; Organ M. G. Palladium complexes of N-heterocyclic carbenes as catalysts for cross-coupling reactions-a synthetic chemist’s perspective. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2768–2813. 10.1002/anie.200601663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yang L.; Guan P.; He P.; Chen Q.; Cao C.; Peng Y.; Shi Z.; Pang G.; Shi Y. Synthesis and characterization of novel chiral NHC-palladium complexes and their application in copper-free Sonogashira reactions. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5020–5025. 10.1039/c2dt12391f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Rit A.; Pape T.; Hepp A.; Hahn F. E. Supramolecular structures from polycarbene ligands and transition metal ions. Organometallics 2011, 30, 334–347. 10.1021/om101102j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Suzuki A. Cross-coupling reactions via organoboranes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 653, 83–90. 10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01269-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Liu Q. X.; Zhang W.; Zhao X. J.; Zhao Z. X.; Shi M. C.; Wang X. G. NHC PdII complex bearing 1,6-hexylene linker: synthesis and catalytic activity in the Suzuki-Miyaura and Heck-Mizoroki reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 7, 1253–1261. 10.1002/ejoc.201200954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Uzelac M.; Hevia E. Polar organometallic strategies for regioselective C-H metallation of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2455–2462. 10.1039/C8CC00049B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Trose M.; Nahra F.; Cazin C. S. J. Dinuclear N-heterocyclic carbene copper(I) complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 355, 380–403. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Johnson C.; Albrecht M. Piano-stool N-heterocyclic carbene iron complexes: synthesis, reactivity and catalytic applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 352, 1–14. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Marion N.; Navarro O.; Mei J. G.; Stevens E. D.; Scott N. M.; Nolan S. P. Modified (NHC)Pd(allyl)Cl (NHC = N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes for room-temperature Suzuki-Miyaura and Buchwald-Hartwig reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4101–4111. 10.1021/ja057704z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Altenhoff G.; Goddard R.; Lehmann C. W.; Glorius F. Sterically demanding, bioxazoline-derived N-heterocyclic carbene ligands with restricted flexibility for catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15195–15201. 10.1021/ja045349r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c César V.; Bellemin-Laponnaz S.; Gade L. H. Direct coupling of oxazolines and N-heterocyclic carbenes: a modular approach to a new class of C-N donor ligands for homogeneous catalysis. Organometallics 2002, 21, 5204–5208. 10.1021/om020608b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Karimi B.; Enders D. New N-heterocyclic carbene palladium complex/ionic liquid matrix immobilized on silica: application as recoverable catalyst for the Heck reaction. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 1237–1240. 10.1021/ol060129z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lei P.; Meng G. R.; Ling Y.; An J.; Szostak M. Pd-PEPPSI: Pd-NHC precatalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions of amides. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 6638–6646. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Farmer J. L.; Pompeo M.; Organ M. G. Pd-N-Heterocyclic carbene complexes in cross-coupling applications. Ligand Des. Met. Chem. 2016, 134–175. 10.1002/9781118839621.ch6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Balinge K. R.; Bhagat P. R. Palladium-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes for the Mizoroki-Heck reaction: an appraisal. C. R. Chim. 2017, 20, 773–804. 10.1016/j.crci.2017.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Gafurov Z. N.; Kantyukov A. O.; Kagilev A. A.; Balabayev A. A.; Sinyashin O. G.; Yakhvarov D. G. Nickel and palladium N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Synthesis and application in cross-coupling reactions. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 66, 1529–1535. 10.1007/s11172-017-1920-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Garrison J. C.; Youngs W. J. Ag(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: synthesis, structure, and application. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3978–4008. 10.1021/cr050004s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Nielsen D. J.; Cavell K. J.; Skelton B. W.; White A. H. Silver(I) and palladium(II) complexes of an ether-functionalized quasi-pincer bis-carbene ligand and its alkyl analogue. Organometallics 2006, 25, 4850–4856. 10.1021/om0605175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Song H. B.; Liu Y. Q.; Fan D. N.; Zi G. F. Synthesis, structure, and catalytic activity of rhodium complexes with new chiral binaphthyl-based NHC-ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 3714–3720. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wang X.; Liu S.; Weng L. H.; Jin G. X. A trinuclear silver(I) functionalized N-heterocyclic carbene complex and its use in transmetalation: structure and catalytic activity for olefin polymerization. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3565–3569. 10.1021/om060309c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Huang J.; Stevens E. D.; Nolan S. P. Intramolecular C-H activation involving a rhodium-imidazol-2-ylidene complex and its reaction with H2 and CO. Organometallics 2000, 19, 1194–1197. 10.1021/om990922e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Liu Q. X.; Yang X. Q.; Zhao X. J.; Ge S. S.; Liu S. W.; Zang Y.; Song H. B.; Guo J. H.; Wang X. G. Macrocyclic dinuclear silver(I) complexes based on bis(N-heterocyclic carbene) ligands: synthesis and structural studies. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 2245–2255. 10.1039/b919007d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Chen J. H.; Zhang X. Q.; Feng Q.; Luo M. M. Novel hexadentate imidazolium salts in the rhodium-catalyzed addition of arylboronic acids to aldehydes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 691, 470–474. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2005.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Liu Q. X.; Yao Z. Q.; Zhao X. J.; Chen A. H.; Yang X. Q.; Liu S. W.; Wang X. G. Two N-heterocyclic carbene silver(I) cyclophanes: synthesis, structural studies, and recognition for p-phenylenediamine. Organometallics 2011, 30, 3732–3739. 10.1021/om1012117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Jiang Y. S.; Chen W. Z.; Lu W. M. Synthesis of 3-arylcoumarins through N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed condensation and annulation of 2-chloro-2-arylacetaldehydes with salicylaldehydes. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3669–3676. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Van Veldhuizen J. J.; Campbell J. E.; Giudici R. E.; Hoveyda A. H. A readily available chiral Ag-based N-heterocyclic carbene complex for use in efficient and highly enantioselective Ru-catalyzed olefin metathesis and Cu-catalyzed allylic alkylation reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6877–6882. 10.1021/ja050179j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lin J. C. Y.; Huang R. T. W.; Lee C. S.; Bhattacharyya A.; Hwang W. S.; Lin I. J. B. Coinage metal-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3561–3598. 10.1021/cr8005153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Crudden C. M.; Allen D. P. Stability and reactivity of N-heterocyclic carbene complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 2247–2273. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Que Y.; Lu Y.; Wang W.; Wang Y.; Wang H.; Yu C.; Li T.; Wang X.-S.; Shen S.; Yao C. An enantioselective assembly of dihydropyranones through an NHC/LiCl-mediated in situ activation of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids. Chem. – Asian J. 2016, 11, 678–681. 10.1002/asia.201501353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Tulloch A. A. D.; Danopoulos A. A.; Winston S.; Kleinhenz S.; Eastham G. N-Functionalised heterocyclic carbene complexes of silver. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2000, 4499–4506. 10.1039/b007504n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Song H. B.; Fan D. N.; Liu Y. Q.; Hou G. H.; Zi G. F. Synthesis, structure, and catalytic activity of nickel complexes with new chiral binaphthyl-based NHC-ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 729, 40–45. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Gade L. H.; Bellemin-Laponnaz S. Mixed oxazoline-carbenes as stereodirecting ligands for asymmetric catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 718–725. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Liu B.; Chen C. Y.; Zhang Y. J.; Liu X. L.; Chen W. Z. Dinuclear copper(I) complexes of phenanthrolinyl-functionalized NHC ligands. Organometallics 2013, 32, 5451–5460. 10.1021/om400738c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Zhang X. Q.; Qiu Y. P.; Rao B.; Luo M. M. Palladium(II)-N-heterocyclic carbene metallacrown ether complexes: synthesis, structure, and catalytic activity in the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction. Organometallics 2009, 28, 3093–3099. 10.1021/om8011695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Wang J. W.; Li Q. S.; Xu F. B.; Song H. B.; Zhang Z. Z. Synthetic and structural studies of silver(I)- and Gold(I)-containing N-heterocyclic carbene metallacrown ethers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 1310–1316. 10.1002/ejoc.200500638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Li Q.; Xie Y. F.; Sun B. C.; Yang J.; Song H. B.; Tang L. F. Synthesis of N-heterocyclic carbene silver and palladium complexes bearing bis(pyrazol-1-yl)methyl moieties. J. Organomet. Chem. 2013, 745–746, 106–114. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tulloch A. A. D.; Winston S.; Danopoulos A. A.; Eastham G.; Hursthouse M. B. 2-Pyridinealdoxime, a new ligand for a Pd-precatalyst: application in solid-phase-assisted Suzuki-Miyaura reaction. Dalton Trans. 2003, 699–708. 10.1039/b209231j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Guerret O.; Sole S.; Gornitzka H.; Teichert M. L.; Teingnier G.; Berte G. 1,2,4-Triazole-3,5-diylidene: a building block for organometallic polymer synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6668–6669. 10.1021/ja964191a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Lee C. K.; Lee K. M.; Lin I. J. B. Inorganic-organic hybrid lamella of di-and tetranuclear silver-carbene complexes. Organometallics 2002, 21, 10–12. 10.1021/om010666h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Arduengo A. J. III; Dias H. V. R.; Calabrese J. C.; Davidson F. Homoleptic carbene-silver(I) and carbene-copper (I) complexes. Organometallics 1993, 12, 3405–3409. 10.1021/om00033a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Ku R. Z.; Huang J. C.; Cho J. Y.; Kiang F. M.; Reddy K. R.; Chen Y. C.; Lee K. J.; Lee J. H.; Lee G. H.; Peng S. M.; Liu S. T. Metal ion mediated transfer and cleavage of diaminocarbene ligands. Organometallics 1999, 18, 2145–2154. 10.1021/om981023d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Murahashi T.; Kurosawa H. Organopalladium complexes containing palladium palladium bonds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 231, 207–228. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00121-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Murahashi T.; Fujimoto M.; Oka M. A.; Hashimoto Y.; Uemura T.; Tatsumi Y.; Nakao Y.; Ikeda A.; Sakaki S.; Kurosawa H. Discrete sandwich compounds of monolayer palladium sheets. Science 2006, 313, 1104–1107. 10.1126/science.1125245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hruszkewycz D. P.; Wu J.; Hazari N.; Incarvito C. D. Palladium(I)-bridging allyl dimers for the catalytic functionalization of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 3280–3283. 10.1021/ja110708k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hruszkewycz D. P.; Wu J.; Green J. C.; Hazari N.; Schmeier T. J. Mechanistic studies of the insertion of CO2 into palladium(I) bridging allyl dimers. Organometallics 2012, 31, 470–485. 10.1021/om201163k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Tanase T.; Nomura T.; Fukushima T.; Yamamoto Y.; Kobayashi K. Synthesis and characterization of a binuclear pslladium(1) complex with bridging q3-Indenyl ligands, Pd2(p-q3-indenyl)2(isocyanide)2, and its transformation to a tetranuclear palladium(1) cluster of isocyanides, Pd4(p-acetate)4(p-isocyanide)4+. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 4578–4584. 10.1021/ic00073a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Zhu L.; Kostic N. M. Molecular orbital study of bimetallic complexes containing conjugated and aromatic hydrocarbons as bridging ligands. Organometallics 1988, 7, 665–669. 10.1021/om00093a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Dai W.; Chalkley M. J.; Brudvig G. W.; Hazari N.; Melvin P. R.; Pokhrel R.; Takase M. K. Synthesis and properties of NHC-supported palladium(II) dimers with bridging allyl, cyclopentadienyl, and indenyl Ligands. Organometallics 2013, 32, 5114–5127. 10.1021/om400687m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Knowles J. P.; Whiting A. The Heck-Mizoroki cross-coupling reaction: a mechanistic perspective. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 31–44. 10.1039/B611547K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ahrens S.; Zeller A.; Taige M.; Strassner T. Extension of the alkane bridge in BisNHC-palladium-chloride complexes. Synthesis, structure, and catalytic activity. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5409–5415. 10.1021/om060577a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Catalano V. J.; Malwitz M. A. Short metal-metal separations in a highly luminescent trimetallic Ag(I) complex stabilized by bridging NHC ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 42, 5483–5485. 10.1021/ic034483u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rit A.; Pape T.; Hahn F. E. Self-assembly of molecular cylinders from polycarbene ligands and AgI or AuI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4572–4573. 10.1021/ja101490d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. X.; Wang H.; Zhao X. J.; Yao Z. Q.; Wang Z. Q.; Chen A. H.; Wang X. G. N-Heterocyclic carbene silver(I), palladium(II) and mercury(II) complexes: synthesis, structural studies and catalytic activity. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 5330–5348. 10.1039/c2ce25365h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Negishi E.Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis, 1st ed.; de Meijere A., Ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, 2003; pp 249–262. [Google Scholar]; b Tsuji J.Palladium Reagents and Catalysts: New Perspectives for the 21st Century, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, 2005; pp 105–430. [Google Scholar]

- a Dieck H. A.; Heck R. F. Organophosphinepalladium complexes as catalysts for vinylic hydrogen substitution reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 1133–1136. 10.1021/ja00811a029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ben-David Y.; Portnoy M.; Gozin M.; Milstein D. Palladium-catalyzed vinylation of aryl chlorides. Chelate effect in catalysis. Organometallics 1992, 11, 1995–1996. 10.1021/om00042a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Jutand A.; Mosleh A. Rate and mechanism of oxidative addition of aryl triflates to zerovalent palladium complexes. Evidence for the formation of cationic (a-ary1)palladium complexes. Organometallics 1995, 14, 1810–1817. 10.1021/om00004a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Fu X.; Zhang S.; Yin J.; McAllister T. L.; Jiang S. A.; Tann C.-H.; Thiruvengadam T. K.; Zhang F. First examples of a tosylate in the palladium-catalyzed Heck cross coupling reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 573–576. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)02240-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Hansen A. L.; Skrydstrup T. Regioselective Heck couplings of α,β-unsaturated tosylates and mesylates with electron-rich olefins. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5585–5587. 10.1021/ol052136d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Selvakumar K.; Zapf A.; Beller M. New palladium carbene catalysts for the Heck reaction of aryl chlorides in ionic liquids. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 3031–3033. 10.1021/ol020103h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bedford R. B.; Blake M. E.; Butts C. P.; Holder D. The Suzuki coupling of aryl chlorides in TBAB-water mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 466–468. 10.1039/b211329e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gunnlaugsson T.; Leonard J. P.; Murray N. S. Highly selective colorimetric naked-eye Cu(II) detection using an azobenzene chemosensor. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1557–1560. 10.1021/ol0498951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Huynh H. V.; Han Y.; Ho J. H.; Tan G. K. Palladium(II) complexes of a sterically bulky, benzannulated N-heterocyclic carbene with unusual intramolecular C-H···Pd and Ccarbene···Br interactions and their catalytic activities. Organometallics 2006, 25, 3267–3274. 10.1021/om060151w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Li S. H.; Lin Y. J.; Cao J. G.; Zhang S. B. Guanidine/Pd(OAc)2-catalyzed room temperature Suzuki cross-coupling reaction in aqueous media under aerobic conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 4067–4072. 10.1021/jo0626257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Eckhardt M.; Fu G. C. The first applications of carbene ligands in cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles: Sonogashira reactions of unactivated alkyl bromides and iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13642–13643. 10.1021/ja038177r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Batey R. A.; Shen M.; Lough A. J. Carbamoyl-substituted N-Heterocyclic carbene complexes of palladium(II): application to sonogashira cross-coupling reactions. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 1411–1414. 10.1021/ol017245g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Phan N. T. S.; Van Der Sluys M.; Jones C. W. On the Nature of the Active Species in Palladium Catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura Couplings – Homogeneous or Heterogeneous Catalysis, A Critical Review. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006, 348, 609–679. 10.1002/adsc.200505473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Widegren J. A.; Finke R. G. A review of the problem of distinguishing true homogeneous catalysis from soluble or other metal-particle heterogeneous catalysis under reducing conditions. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2003, 198, 317–341. 10.1016/S1381-1169(02)00728-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Yu K.; Sommer W.; Weck M.; Jones C. W. Silica and polymer-tethered Pd–SCS-pincer complexes: evidence for precatalyst decomposition to form soluble catalytic species in Mizoroki–Heck chemistry. J. Catal. 2004, 226, 101–110. 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Eberhard M. R. Insights into the Heck reaction with PCP pincer palladium(II) complexes. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2125–2128. 10.1021/ol049430a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Eberhard M. R. Insights into the Heck Reaction with PCP Pincer Palladium(II) Complexes. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2125–2128. 10.1021/ol049430a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu K. Q.; Sommer W.; Richardson J. M.; Weck M.; Jones C. W. Evidence that SCS Pincer Pd(II) Complexes are only Precatalysts in Heck Catalysis and the Implications for Catalyst Recovery and Reuse. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005, 347, 161–171. 10.1002/adsc.200404264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a van der Made A. W.; van der Made R. H. A convenient procedure for bromomethylation of aromatic compounds. Selective mono-, bis-, or trisbromomethylation. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 1262–1263. 10.1021/jo00057a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Su C. Y.; Cai Y. P.; Chen C. L.; Smith M. D.; Kaim W.; zur Loye H. C. Ligand-directed molecular architectures: self-assembly of two-dimensional rectangular metallacycles and three-dimensional trigonal or tetragonal prisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 8595–8613. 10.1021/ja034267k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. X.; Zhao X. J.; Wu X. M.; Yin L. N.; Guo J. H.; Wang X. G.; Feng J. C. Two new N-heterocyclic carbene silver(I) complexes with the π-π stacking interactions. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2008, 361, 2616–2622. 10.1016/j.ica.2007.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SAINT. Software Reference Manual; Bruker AXS: Madison, WI, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.SHELXTL NT, Program for Solution and Refinement of Crystal Structures, version 5.1; University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany, 1997.

- Palmer D. C.CrystalMaker, 7.1.5; CrystalMaker Software: Yarnton, U.K., 2006.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.