SUMMARY

Diacylglycerol lipase-beta (DAGLβ) hydrolyzes arachidonic acid (AA)-esterified diacylglycerols to produce 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and downstream prostanoids that mediate inflammatory responses of macrophages. Here, we utilized DAGL-tailored activity-based protein profiling and genetic disruption models to discover that DAGLβ regulates inflammatory lipid and protein signaling pathways in primary dendritic cells (DCs). DCs serve as an important link between innate and adaptive immune pathways by relaying innate signals and antigen to drive T cell clonal expansion and prime antigen-specific immunity. We discovered that disruption of DAGLβ in DCs lowers cellular 2-AG and AA that is accompanied by reductions in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated TNF-α secretion. Cell-based vaccination studies revealed DC maturation ex vivo and immunogenicity in vivo was surprisingly unaffected by DAGLβ inactivation. Collectively, we identify DAGLβ pathways as a means for attenuating DC inflammatory signaling while sparing critical adaptive immune functions and further expands the utility of targeting lipid pathways for immunomodulation.

In Brief

DAGLβ lipid pathways were probed by chemical biology and immunological approaches to discover a selective role in attenuating dendritic cell inflammatory signaling while sparing critical adaptive immune functions and further expands the utility of targeting lipid pathways for immunomodulation.

INTRODUCTION

Diacylglycerol lipases (DAGLs) are evolutionarily conserved serine hydrolases most well known for their role in hydrolyzing arachidonic acid (AA)-esterified diacylglycerols (DAGs) to produce the principal endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) (Reisenberg et al., 2012). Mammals express two distinct isoforms, DAGL α and DAGLβ, whose functions are segregated by tissue- and cell type-specific expression (Bisogno et al., 2003). DAGL α is expressed predominantly in central nervous tissues and plays a key role in regulating 2-AG involved in synaptic activity and neuroinflammation (Gao et al., 2010; Ogasawara et al., 2016; Tanimura et al., 2010). DAGLβ regulates 2-AG and downstream metabolic products (e.g. prostaglandins) important for proinflammatory signaling in neuroinflammation and pain through its enriched activity in macrophages and microglia (Hsu et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2018; Viader et al., 2016). Considering inflammatory signals direct adaptive immunity, we set out to investigate the role of DAGLs in mediating cross-talk between innate and adaptive immune pathways in vivo. These studies are important for further demarcation of DAGL isoform specificity in regulation of lipid pathways of the immune system.

Here, we leveraged DAGL-tailored activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) (Niphakis and Cravatt, 2014), mass spectrometry metabolomics, and genetic disruption models to investigate DAGL function in dendritic cells (DCs), which are key innate immune cells responsible for relaying innate signals and antigen to drive T cell clonal expansion and prime antigen-specific immunity (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2010; Reis e Sousa, 2006; Steinman, 2012). Immature DCs efficiently survey their environment to capture antigens. Exposure to maturation signals (e.g. inflammatory cytokines, microbial patterns) triggers migration to secondary lymphoid tissues and transition from an antigen-sampling state to a mature antigen-presenting cell (APC) that can prime T cells (Reis e Sousa, 2006; Steinman, 2012). Given that lipid metabolism directly affects immunogenicity of DCs in mice and humans (Cubillos-Ruiz et al., 2015; Herber et al., 2010), we pursued studies to investigate the role of DAGLs in the metabolic, signaling, and immunogenic functions of DCs.

RESULTS

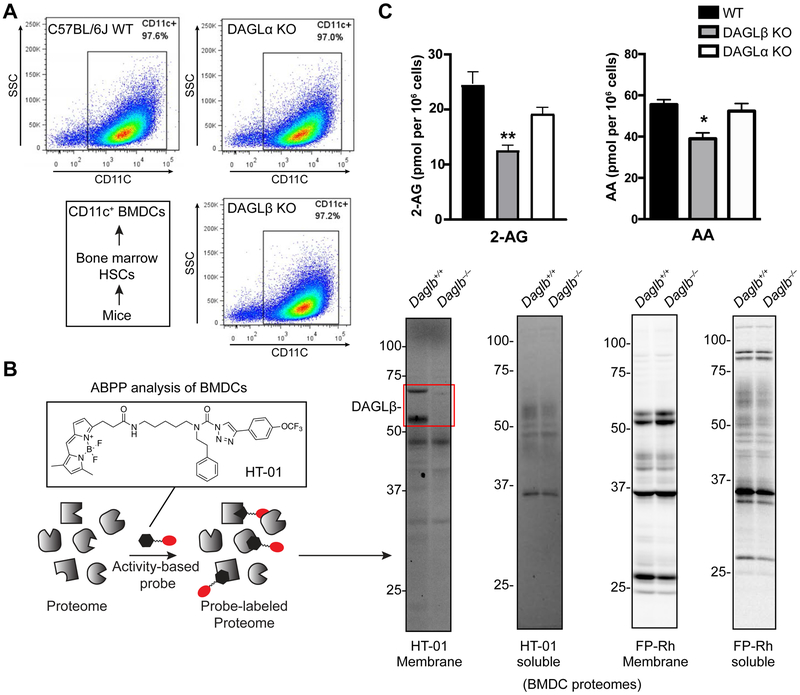

Chemoproteomic discovery of DAGLβ activity in primary dendritic cells

We generated bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from Daglb−/− mice following previous reported procedures (Lutz et al., 1999) and as detailed in the STAR Methods. We also included Dagla−/− BMDCs to directly compare whether DAGL function in BMDCs is isoform specific. In brief, bone marrow cells were harvested from femurs and tibias of mice and cultured in the presence of GM-CSF for 10 days followed by enrichment for BMDCs by separating suspension (fraction containing BMDCs) from adherent cells. We used flow cytometry and established surface markers of DCs (CD11c (Keller et al., 2008)) to confirm >95% of BMDCs were CD11c+ dendritic cells (Fig 1A).

Figure 1. Chemical proteomic and metabolomic analysis of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs).

(A) BMDCs were differentiated from bone marrow of C57BL/6J mouse and dendritic cell phenotype and purity determined by flow cytometry analysis of a dendritic cell surface marker (CD11c). BMDCs derived from DAGLα and DAGLβ mice were comparable with wild-type counterparts. See Fig S1 for gating strategy used in flow cytometry analyses. (B) Schematic of activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) of BMDCs. BMDC proteomes were treated with DAGL-directed ABPP probe HT-01 or broad-spectrum serine hydrolase probe FP-Rh (1 μM of probes, 30 min, 37 °C). Probe-labeled samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence scanning to confirm active DAGLβ in BMDC proteomes with no discernable changes in other detectable band serine hydrolase activities. The lower molecular weight represents a proteolytic fragment of DAGLβ that is sometimes generated and observed during sample processing. (C) Targeted metabolomics analysis of BMDCs showed that 2-arachidonylglycerol (2-AG) and downstream lipid product, arachidonic acid (AA) is reduced in DAGLβ-disrupted BMDCs. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 for DAGLβ KO versus wild-type groups. Data are mean ± s.e.m.; n = 3 per group.

Next, we confirmed that BMDCs expressed active DAGLβ using our DAGL-tailored activity- based protein profiling (ABPP, Fig 1B) probe, HT-01 (Hsu et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2018). We detected prominent HT-01 labeling of an ~70 kDa protein band corresponding to endogenous DAGLβ activity that was present in Daglb+/+ but absent from Daglb−/− BMDC membrane proteomes as measured by gel-based ABPP (Fig 1B). We could not detect native DAGLα activity in BMDC proteomes as evidenced by the lack of any detectable fluorescent band in the ~120 kDa molecular weight range (Fig 1B). We also compared activity profiles of other serine hydrolases (SHs) detected in BMDC proteomes by exchanging HT-01 for a broad SH-reactive ABPP probe, fluorophosphonate-rhodamine (FP-Rh (Bachovchin et al., 2010)). As shown in Fig 1B, we did not observe any substantial differences in SH activity profiles in gel-based ABPP analysis of Daglb+/+ compared with Daglb−/− BMDC proteomes labeled with FP-Rh.

DAGLβ regulates endocannabinoid and arachidonic acid metabolism in BMDCs

Previous studies established that both DAGLα and DAGLβ hydrolyze arachidonic acid (AA)-esterified diacylglycerols (DAGs) to produce the principal endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) (Hsu et al., 2012; Ogasawara et al., 2016). Although DAGLα and DAGLβ are capable of catalyzing the same lipid biochemistry, their respective metabolic functions in living systems are segregated by tissue- and cell type-specific expression (Viader et al., 2016). Here, we employed targeted metabolomics to compare lipid composition of BMDCs from DAGLα and DAGLβ knockout (KO) mice compared with wild-type (WT) counterparts. Total lipids (i.e. lipidome) were extracted from BMDCs using the Folch method (Folch et al., 1957) and analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) on a high-resolution Q-Exactive mass spectrometer configured for parallel reaction monitoring acquisition (Peterson et al., 2012). We observed a reduction in cellular 2-AG in Daglb−/− compared with Daglb+/+ BMDCs (~50% reduction in 2-AG, Fig 1C). In agreement with previous findings in macrophages, we also observed a corresponding ~30% reduction in cellular AA in Daglb−/− BMDCs, which supports DAGLβ biosynthesis of 2-AG pools utilized for AA production (Fig 1C). In contrast, cellular 2-AG and AA was largely unchanged between Dagla+/+ and Dagla−/− BMDC lipidomes (Fig 1C). In summary, our metabolomics findings identify DAGLβ as a key 2-AG biosynthetic enzyme in dendritic cells.

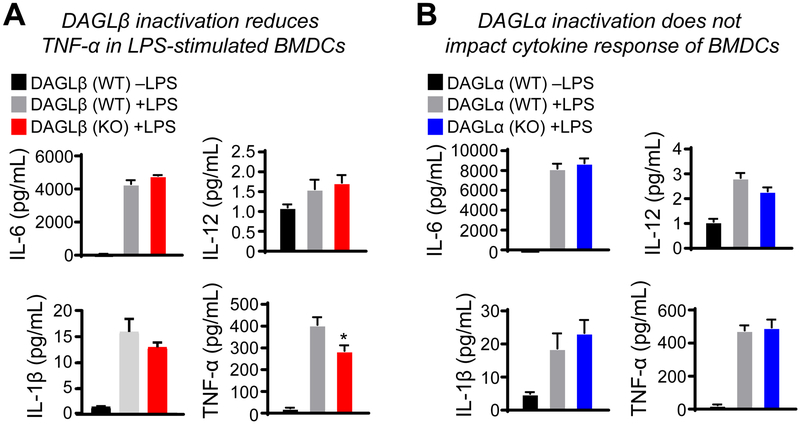

DAGLβ regulates LPS-stimulated TNF-αErelease of BMDCs

To understand how DAGLβ metabolism affects BMDC signaling, we evaluated cytokine response of DAGL-disrupted BMDCs exposed to the inflammatory stimuli, lipopolysaccharide (LPS). DCs express toll-like receptors (e.g. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4) that can sense pathogens in order to rapidly activate innate immune responses through production of proinflammatory cytokine and lipid signals (Steinman, 2012). To examine the effects of DAGL inactivation on the inflammatory response of DCs, BMDCs were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL, 6 hrs) followed by multiplex bead-based Luminex immunoassay of secreted cytokines in media from treated cells. LPS-stimulated BMDCs showed a marked increase in secreted TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, as well as a modest enhancement in IL-12 compared with non-stimulated dendritic cells as quantified by multiplex immunoassay of their conditioned media (Fig 2).

Figure 2. DAGLβ regulates TNF-α response of LPS-stimulated BMDCs.

Cytokine secretion by BMDCs exposed to vehicle or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL, 6 hrs) were detected using a Luminex MAGPIX system for multiplex evaluation of secreted TNF-α, IL-12, IL-6, and IL-1β from LPS-stimulated BMDCs. The results showed disruption of DAGLβ (A) but not DAGLα (B) suppressed TNF-α secretion in LPS-stimulated BMDCs. *P < 0.05 for WT+LPS versus KO+LPS groups. Data are mean ± s.e.m.; n = 4 per group.

Interestingly, Daglb−/− BMDCs exhibited significantly reduced secreted TNF-α in response to LPS when compared with wild-type counterparts (Fig 2A). DAGLβ regulation of TNF-α appeared specific given that levels of other cytokines including IL-6, IL-12 and IL-1 β remained largely unchanged (Fig 2A). Our current data match previous findings in macrophages showing disruption of DAGLβ reduced levels of secreted TNF-α in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Hsu et al., 2012). In contrast, secreted TNF-α was largely unchanged in Dagla −/− compared with Dagla +/+ BMDCs stimulated with LPS (Fig 2B). Further analysis showed cytokine response of BMDCs to LPS was largely unaffected by DAGLα inactivation with the exception of a slight decrease in secreted IL-12 that did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.0805, Fig 2B). In summary, our findings identify a role for DAGLβ in specific regulation of TNF-α response of DCs exposed to inflammatory stimuli.

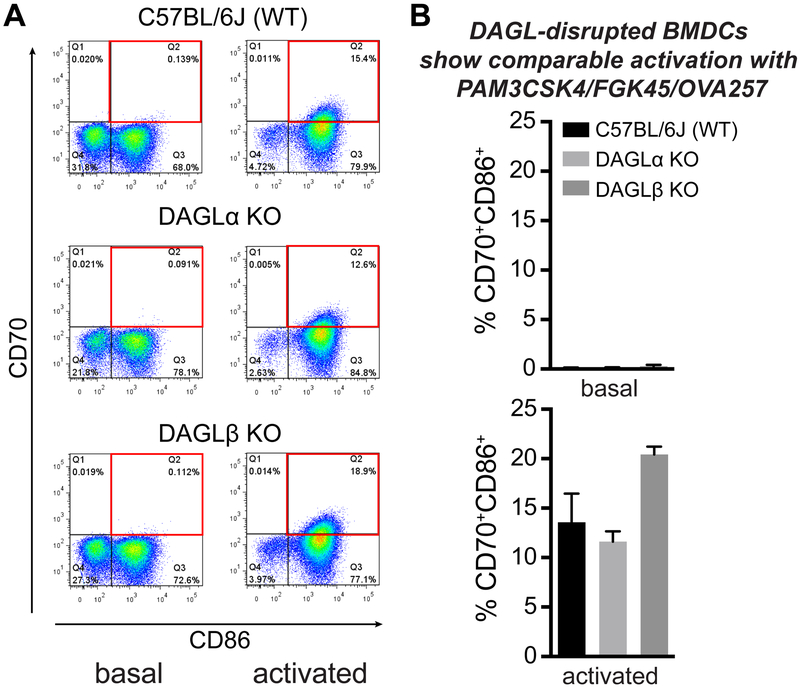

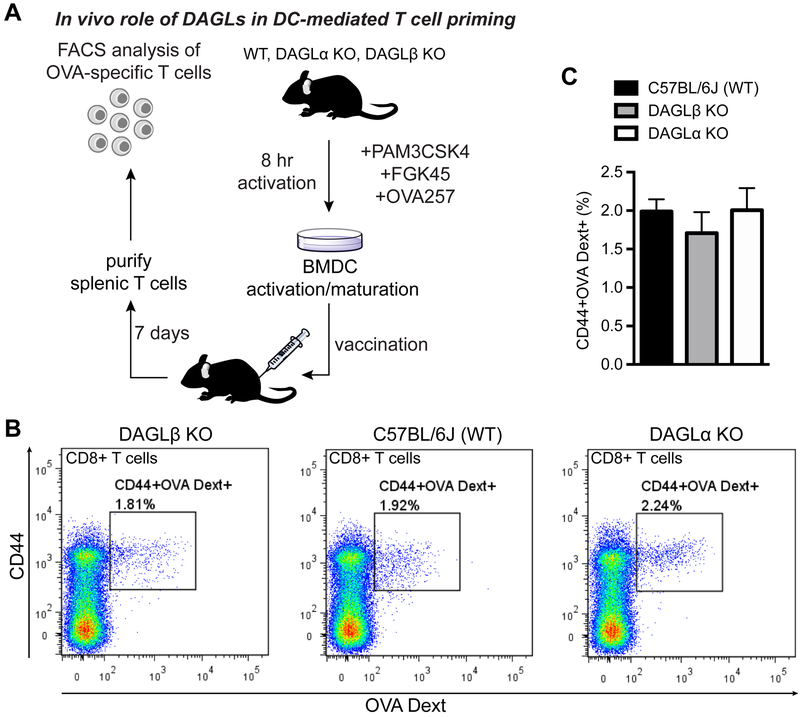

DAGLβ inactivation does not affect DC-mediated T cell priming in vivo

Next, we examined the capacity of DAGL-disrupted BMDCs to prime antigen-specific T cell responses by cell-based vaccination in vivo. Here, BMDCs were activated and loaded with peptide antigens followed by injection into mice, initiation of immunity, and detection of antigen-specific T cells from ex vivospleens of vaccinated mice. We chose ovalbumin peptide (OVA257) for eliciting antigen-specific responses because this peptide is presented by class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) to elicit a robust OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response in vivo, which can be quantified by flow cytometry using OVA-specific MHC dextramers (see STAR Methods for additional details).

First, we asked whether DAGL inactivation impacts activation/maturation of BMDCs. These studies evaluated whether BMDC maturation in the presence of peptide antigen is impaired with DAGL inactivation. For these studies, we chose ex vivo maturation conditions optimized for eliciting CD8+ T cell responses in mice. BMDCs were exposed to PAM3CSK4 (TLR1/TLR2 agonist), FGK45 (CD40 agonistic antibody), and OVA257 (10 μg/mL) and the degree of activation determined by expression of DC maturation markers, CD70 and CD86 (Bullock and Yagita, 2005; Keller et al., 2008; Reis e Sousa, 2006; Van Deusen et al., 2010) (Fig 3A). Activation of BMDCs resulted in a large increase in CD11c+CD70+CD86+ dendritic cells (from ~0.1% to ~14% in basal versus activated, respectively, Fig 3B). The degree of activation, as judged by the number of CD11c+CD70+CD86+ BMDCs, was comparable across all genotypes with the exception of a slight increase in the number of activated Daglb−/− BMDCs that did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.0834, Fig 3B).

Figure 3. DAGL inactivation does not impair BMDC activation/maturation.

BMDCs (3 × 106 cells) were stimulated using PAM3CSK4 (1 μg/mL), FGK45 (1 μg/mL), and OVA257 (10 μg/mL) for 8 hrs at 37 °C. (A) BMDC phenotype was confirmed with anti-CD11c (APC). The degree of BMDC activation/maturation was determined by flow cytometry analysis of increased surface expression of CD70 (PE) and CD86 (FITC). See Fig S1 for gating strategy used in flow cytometry analyses. (B) Bar plot comparing percentage of CD11c+CD70+CD86+ BMDCs from basal and activated BMDCs, which was used to evaluate activation/maturation across genotypes tested. Data are mean ± s.e.m.; n = 3 per group.

Next, we tested the impact of DAGL disruption on immunogenicity of BMDCs in vivo. We vaccinated mice with CD11c+CD70+CD86+ BMDCs pulsed with OVA257–264 peptide (10 μg/mL), followed by enumerating OVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells within the spleen 7 days later using MHC- dextramer staining and flow cytometry (Fig 4A). We observed comparable numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated with Daglb+/+ and Daglb−/− BMDCs (Fig 4B and C). These in vivo findings were important given that our ex vivo experiments suggested a possible enhancement in maturation of Daglb−/− BMDCs (Fig 3B). We also showed that inactivation of DAGLα does not impact the CD8+ T cell priming capacity of vaccinated BMDCs (Fig 4B and C). Collectively, our results demonstrate that disruption of DAGLs does not affect maturation ex vivo and T cell priming capacity of DCs in vivo.

Figure 4. DAGL inactivation does not affect BMDC priming of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo.

(A) BMDC activation/maturation was achieved by incubation with PAM3CSK4 (1 μg/mL), FGK45 (1 μg/mL), and OVA257 (10 μg/mL) for 8 hrs at 37 °C ex vivo. Afterwards, C57BL/6J mice were vaccinated (tail vein by i.v. injection) with 100,000 CD11c+CD70+CD86+ BMDCs. Mice were sacrificed after 7 days, spleens harvested, and splenic cells isolated for flow cytometry analysis. (B) An OVA-specific MHC1 dextramer (OVA Dext) was used to quantify percentage of OVA-specific CD8+CD44+OVA Dext+ T cells using flow cytometry. See Fig S2 for gating strategy used in flow cytometry analyses. (C) No significant differences in percentage of CD8+CD44+OVA Dext+ splenic T cells from vaccinated mice across genotypes tested. Data is representative of cell vaccination experiments from 2 independent cohorts of mice (n = 3–5 mice per group).

DISCUSSION

DCs serve as a critical link between innate and adaptive immunity and form the basis of new cellular immunotherapies against cancer in the clinic (Steinman, 2012). Identifying molecular pathways that modulate DC inflammatory and immunogenic functions is important for basic understanding of innate regulation of immunity. Here, we apply chemical proteomics, mass spectrometry metabolomics, and cell- based vaccination in vivo to identify DAGLβ regulation of lipid signaling pathways that uncouple the cytokine response and T cell priming capacity of DCs. Our findings are significant given that proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α produced by DCs are directly involved in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammation (Connolly et al., 2009).

We overcame challenges with detecting endogenous DAGL activity, which are typically expressed in low abundance in cells and tissues, in BMDCs using activity-based probes tailored for measuring DAGLβ and DAGLα activity (Hsu et al., 2012; Hsu et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2018). Our chemical proteomic studies revealed that DAGLβ but not DAGLα is expressed and active in BMDCs (Fig 1B). Our findings are in agreement with previous reports demonstrating that DAGLβ is the principal isoform found in innate immune cells including macrophages and microglia (Hsu et al., 2012; Viader et al., 2016). The isoform specificity of DAGLs was further validated through MS-metabolomics and cytokine profiling, which showed reduced cellular 2-AG/AA (Fig 1C) and TNF-α (Fig 2), respectively, in Daglb−/− but not Dagla−/− BMDCs compared to wild-type counterparts. The impaired LPS-stimulated TNF-α response of Daglb−/−BMDCs was intriguing given these cells did not show defects in maturation (Fig 3) and could efficiently prime antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses in animal vaccination studies (Fig 4). Thus, disruption of DAGLβ pathways is a potential route towards selective regulation of DC inflammatory responses.

Our findings are noteworthy given the potential for targeting DAGLβ for inflammation. Chemicalor genetic disruption of DAGLβ provides anti-inflammatory effects in animal models of pain and neuroinflammation (Shin et al., 2018; Wilkerson et al., 2016). While inhibiting DAGLα provides similar anti-inflammatory effects in vivo (Ogasawara et al., 2016; Viader et al., 2016), long-term disruption of this isoform results in massive alterations in brain lipids that are associated with behavioral defects and seizures in knockout mice (Cavener et al., 2018; Jenniches et al., 2016; Powell et al., 2015). In contrast, DAGLβ knockout mice do not exhibit gross differences in brain lipids and appear to develop and behave normally (Powell et al., 2015; Viader et al., 2016; Wilkerson et al., 2016). Our current findings extend the utility of targeting DAGLβ for inflammation (and potentially chronic inflammation) by showing disruption of this lipase does not appear to impact immunity, which is important given defects in regulating DC immunogenicity has been associated with allergy and autoimmunity (Steinman, 2012). In summary, our findings identify a unique lipid pathway regulated by DAGLβ that modulates an inflammatory cytokine response without affecting maturation and T cell priming capacity of DCs in vivo.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ku-Lung Hsu (kenhsu@virginia.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals.

All studies were conducted in 8–12-week-old C57BL/6J mice. Mice were housed in the MR6 animal facility (UVa), and Gilmer animal facility (UVa). All studies were carried out under a protocol approved by the ACUC/University of Virginia. All animals were allowed free access to a standard chow diet and water. The animals were housed according to the ACUC policy on social housing of animals. For experiments involving BMDCs, both male and female mice were used in performing described work. Each experiment was controlled by using same-sex littermates. For vaccination studies, both male and female mice were used for experiments.

Bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) differentiation.

C57BL/6J mice were sacrificed and femur and tibia were isolated from hindlegs. Bone marrow was extracted by cutting each end of the bone and flushed with serum free RPMI. Red blood cells were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer and cultured in DC differentiation media (200 U/mL GM-CSF, 10% FBS, 2mM L-Glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 units and 100 μg mL−1 penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μM beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), 20 mM HEPES). At day 3, an additional 10 mL of DC differentiation media was added. At day 6 and 8, half of the media was exchanged to DC differentiation media that contains 30 U/mL instead 200 U/mL of GM-CSF. BMDCs were harvested by gently harvesting non-adherent suspension cells.

METHOD DETAILS

Reagents.

Unless otherwise specified, reagents used were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Arachidonic acid-d8 (CaymanChemical Company, catalog# 390010, 2-Arachidonyl glycerol-d5 (Cayman Chemical Company, catalog# 362162. CD11c antibody-APC (Clone: N418, Biolegend, catalog# 117310), CD70 antibody-PE (Clone: FR70, eBioscience, catalog# 12-0701-82), CD86 antibody-FITC (Clone: B7–2, eBioscience, catalogue# 11-0862-82), OVA257 Dextramer-APC (Immudex, Catalog# JD2163-APC, Lot# 20150316-LL2). Fetal Bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Omega scientific.

BMDC activation/maturation.

At day 10 of differentiation, suspension cells were gently harvested by centrifugation at 600 x g for 5 min and resuspended in DC differentiation media. BMDCs were re-plated in a 10 cm petri-dish and activated for 8 hrs with PAM3CSK4 (1 μg/mL), FGK45 (1 μg/mL), and OVA257 (10 μg/mL). At the end of the 8 hrs activation, cells were gently collected and centrifuged at 600 x g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in DC differentiation media and analyzed by flow cytometry for activation and maturation.

BMDC and splenocyte flow cytometry analysis.

BMDCs were analyzed using the following BMDC surface marker panel: CD11c-APC (1:500), CD70-PE (1:250), and CD86-FITC (1:500). Antibodies were diluted with FACS buffer (0.5% BSA, 2 mM EDTA, in PBS). Cells (1 × 105 cells) were resuspended in a 96-well plate (V-bottom plate) and stained with Live/Dead dye (Aqua Dead cell stain; ThermoFisher L34957). Live/Dead reagent was washed with PBS twice before being blocked with FC-block (anti-CD16/32; Invitrogen) for 10 min at 4 °C. Following FC-block, BMDC antibody panels were added and stained for 30 min at 4 °C. Count beads (ThermoFisher 01-1234-42) (51,000 beads) were added after the staining was completed in order to accurately count the number of activated dendritic cells per C57BL/6J mouse. FMO (fluorescence Minus One) controls were prepared by leaving out one of each stain in the staining panel. Activated BMDCs (CD70+, CD86+, CD11c+) cells were injected into C57BL/6J (100,000 activated cells) in PBS by tail vein (i.v.). Spleens were harvested 7 days after BMDC injection. Splenocyte analysis was performed after spleens were dounce-homogenized briefly and filtered through amesh filter (100 m). Splenocytes were labeled with Live/Dead stain, (CD8-FITC (1:500), CD44-PE (1:1000), and OVAdex-APC and FC-block. A splenocyte panel (1:20) (Immudex) was used to stain CD8+ T cells that are specific for OVA257. FMO controls were prepared as above. Samples were analyzed using BDFACS CANTO II flow cytometer. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using FlowJo software version 10 (Ashland OR).

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) of BMDCs.

BMDCs were lysed by dounce homogenization in cold lysis buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, and 2 mM DTT in ddH2O) with Protease and Phosphatase inhibitor (ThermoFisherScientific, A32959). After cell lysis, samples were allowed to sit in ice for 15 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 45 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was labeled as soluble fraction. The remaining pellet (membraneHEPES in H O) and resuspended by passing through a 26-gauge needle in assay buffer. Protein concentrations were measured using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay and lysates were standardized to1 mg/mL for ABPP analysis. Proteomes (1mg/mL) were treated with either HT-01 (1 μM) or FP-Rh (1 μM) for 30 min at 37 °C. Probe labeling was quenched using gel loading buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by in-gel fluorescence scanning using a Chemidoc MP imaging system. The protease inhibitor cocktail is essential for DAGLβ analysis because protease activity in BMDC lysates can result in substantial proteolytic fragments of native DAGLβ.

Lipid extraction.

Folch method (Chloroform:Methanol:Water/2:1:1) were used to extract lipids from BMDC pellets (2.5 million cells). Antioxidant BHT (butylated hydroxy toluene) was added at 50 μg/mL during extraction. Chloroform (2 mL), and Methanol (1 mL) were added with 1 mL of ddH2O containing resuspended BMDCs. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 5 min. Lipid standards used for quantitation include arachidonic acid-d8 (Cayman Chemical Company, Catalog # 390010) and 2-arachidonylglycerol-d5 (Cayman Chemical Company, catalog # 362162). Lipid standards (10 pmol of each standard) were added to organic solvents prior to mixing and lipid extraction of BMDCs. The organic layer was transferred and aqueous layer extracted with addition of 1.5 mL of 2:1 chloroform: methanol solution. The extracted organic layers were combined and dried down under nitrogen stream. Samples were resuspended in 120 μL of 1:1 methanol:isopropanol and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

Mass spectrometry-based lipid analysis of BMDCs.

The lipid samples were analyzed by LC-MS. Dionex Ultimate 3000 RS UHPLC system was used with the analytical column (Kinetex® 1.7 μm C18 100 Å, Phenomenex, LC column 100 × 2.1mm) and reverse phase LC (FA: 0.05% acetic acid, H2O, B: 0.05% acetic acid, Acetonitrile) with the following gradient: Flowrate 0.25 mL/min, 0 min 25%B, 5 min 40%B, 6 min 58%B, 9 min 68%B, 12 min, 90%B, 13 min 90%B, 15 min 100% B. The eluted lipids were ionized through electrospray using a HESI-II probe into an Orbitrap Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Data acquisition was performed through (parallel reaction monitoring) PRM targeting arachidonic acid (303.2318 m/z), arachidonic acid-d5 (311.2820 m/z), 2-arachidonyl glycerol (379.2842 m/z), 2-arachidonyl glycerol-d8 (384.3157 m/z). Through PRM monitoring, fragments of the lipid precursors were monitored (arachidonic acid (259.2434 m/z), arachidonic acid-d5 (267.2935 m/z), 2-arachidonyl glycerol (287.2365 m/z), 2-arachidonyl glycerol-d8 (287.2365 m/z)). Intensities of the lipid species were measured using Tracefinder™ software, which identified fragment ions across multiple samples based on the MS2 filter defined in a targeted list of lipids and aligned them according to the intensities of the ion species found in each raw file. For 2-AG measurements, 4 technical replicates per samples were taken and averaged together to give better approximation of the lipid concentration. Aligned intensities were exported and analyzed using Prism Graphpad version 7.03.

Inflammatory activation of BMDCs and multiplex cytokine analysis.

After BMDCs were differentiated, suspension cells were seeded in a 96-well plate in 50 μL volume at 100,000 cells per well in complete DC differentiation media. 50 μL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in complete DC differentiation media was added to designated wells for a final LPS concentration of 100 ng/mL and incubated for 6 hrs at 37 °C. Supernatant was collected in V-bottom 96 well plate and centrifuged at 1,400 x g for 5 min to pellet residual BMDCs. Supernatant was transferred to a separate 96 well plate and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Cytokine profiling was performedat the UVa flow cytometry core. In brief, antibody-immobilized beads were prepared by sonication/vortexing for 1 min with 60 μL of each individual antibody-bead: anti-Mouse IL-1β (catalog# MIL1B-MAG), anti-Mouse TNFα (catalog# MCYTNFA-MAG), anti-Mouse IL-12 (p70) (catalog# MIL12P70-MAG), and anti-Mouse IL-6 (catalog# MCYIL6-MAG) and combining them in a total volume of 3.0 mL of assay buffer (Millipore corporation, catalog# L-AB). Wells were washed, detected, and analyzed using the Luminex MAGPIX system following manufacturer’s recommended protocols. Samples were analyzed using median fluorescent intensity (MFI) data using a 5-parameter logistic for calculating the cytokine concentrations in samples. Exported data were analyzed using Prism Graphpad version 7.03 and statistical significance was calculated using unpaired t-test.

Data and Software Availability

The Repository ID for the flow cytometry data corresponding to dendritic cell activation and vaccination experiments of OVA-DEX positive CD8+ splenic T cells is stored as a public dataset FR-FCM-Z2ZQ at FlowRepository (https://flowrepository.org/). The mass spectrometry data for lipidomics analysis of BMDCs is published at Mendeley data (doi:10.17632/45csyctfbn.1; https://data.mendeley.com/datasets).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For the lipid analyses, the intensities of targeted lipid species and their deuterated counterparts obtained from the LC-MS analysis were used for the semi-quantitative determination of lipid concentrations within a sample. Intensities of lipid species (arachidonic acid and 2-AG) were divided by the intensities of deuterated standards (arachidonic acid-d8 and 2-AG-d5; 10 pmol). The calculated lipid amounts were the percentage of specific cell populations were calculated based on the MFI normalized based on cell numbers (2.5 million cells) of respective samples. For flow cytometry analyses, after the gating parameters were applied. Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (v7.03). In order to determine statistically significant differences between groups, an unpaired t-test was applied to calculate a P value (unpaired, assume gaussian distribution (parametric test), two tailed, confidence interval of 95%). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. The number of experimental replicates for cells or mice in each sample group are indicated by n and can be found in respective figure legends. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of mean (s.e.m.).

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Chemical proteomics has greatly enabled discovery and annotation of new lipid signaling pathways important for physiology and disease. Among these candidates, diacylglycerol lipase-beta (DAGLβ) has emerged as a promising target for inflammation because of its restricted activity in innate immune cells including macrophages and microglia where it regulates proinflammatory lipid and cytokine signaling in neuroinflammation and pain. Here, we apply activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) and mass spectrometry metabolomics to discover that DAGLβ inactivation in dendritic cells reduces arachidonic acid and secreted TNF-α in response to inflammatory stimuli. The anti-inflammatory effects from DAGLβ disruption did not impair the ability of dendritic cells to prime antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. These findings were surprising given that inflammatory signals induce dendritic cell activation/maturation to enhance T cell priming capacity. The ability to suppress dendritic cell inflammatory pathways while sparing adaptive immune functions is important given that defects in DC immunogenicity has been associated with allergy and autoimmunity. Our findings support DAGLβ as a molecular pathway that can be targeted to selectively suppress dendritic cell inflammatory TNF-α responses.

Highlights.

DAGLβ activity is enriched in primary dendritic cells (DCs)

DAGLβ regulates LPS-stimulated TNF-alpha response of primary DCs

Vaccination shows DAGLβ disruption does not affect DC immunogenic function in vivo

DAGLβ uncouples cytokine response and CD8+ T cell priming capacity of DCs

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the Hsu Lab and colleagues for careful review of this manuscript. This work was supported by the University of Virginia (start-up funds to K.-L.H.) and National Institutes of Health (DA035864 and DA043571 to K.-L.H.; CA166458 to T.N.J.B.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Bachovchin DA, Ji T, Li W, Simon GM, Blankman JL, Adibekian A, Hoover H, Niessen S, and Cravatt BF (2010). Superfamily-wide portrait of serine hydrolase inhibition achieved by library-versus-library screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 20941–20946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, Minassi A, Cascio MG, Ligresti A, Matias I, Schiano-Moriello A, Paul P, Williams EJ, et al. (2003). Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol 163, 463–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock TN, and Yagita H (2005). Induction of CD70 on dendritic cells through CD40 or TLR stimulation contributes to the development of CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 174, 710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener VS, Gaulden A, Pennipede D, Jagasia P, Uddin J, Marnett LJ, and Patel S (2018). Inhibition of Diacylglycerol Lipase Impairs Fear Extinction in Mice. Front Neurosci 12, 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly MK, Bedrosian AS, Mallen-St Clair J, Mitchell AP, Ibrahim J, Stroud A, Pachter HL, Bar-Sagi D, Frey AB, and Miller G (2009). In liver fibrosis, dendritic cells govern hepatic inflammation in mice via TNF-alpha. J Clin Invest 119, 3213–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Silberman PC, Rutkowski MR, Chopra S, Perales-Puchalt A, Song M, Zhang S, Bettigole SE, Gupta D, Holcomb K, et al. (2015). ER Stress Sensor XBP1 Controls Anti-tumor Immunity by Disrupting Dendritic Cell Homeostasis. Cell 161, 1527–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, and Sloane Stanley GH (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226, 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Vasilyev DV, Goncalves MB, Howell FV, Hobbs C, Reisenberg M, Shen R, Zhang MY, Strassle BW, Lu P, et al. (2010). Loss of retrograde endocannabinoid signaling and reduced adult neurogenesis in diacylglycerol lipase knock-out mice. J Neurosci 30, 2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herber DL, Cao W, Nefedova Y, Novitskiy SV, Nagaraj S, Tyurin VA, Corzo A, Cho HI, Celis E, Lennox B, et al. (2010). Lipid accumulation and dendritic cell dysfunction in cancer. Nat Med 16, 880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KL, Tsuboi K, Adibekian A, Pugh H, Masuda K, and Cravatt BF (2012). DAGLbeta inhibition perturbs a lipid network involved in macrophage inflammatory responses. Nat Chem Biol 8, 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu KL, Tsuboi K, Whitby LR, Speers AE, Pugh H, Inloes J, and Cravatt BF (2013). Development and optimization of piperidyl-1,2,3-triazole ureas as selective chemical probes of endocannabinoid biosynthesis. J Med Chem 56, 8257–8269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, and Medzhitov R (2010). Regulation of Adaptive Immunity by the Innate Immune System. Science 327, 291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenniches I, Ternes S, Albayram O, Otte DM, Bach K, Bindila L, Michel K, Lutz B, Bilkei-Gorzo A, and Zimmer A (2016). Anxiety, Stress, and Fear Response in Mice With Reduced Endocannabinoid Levels. Biol Psychiatry 79, 858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller AM, Schildknecht A, Xiao Y, van den Broek M, and Borst J (2008). Expression of costimulatory ligand CD70 on steady-state dendritic cells breaks CD8+ T cell tolerance and permits effective immunity. Immunity 29, 934–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, and Schuler G (1999). Anadvanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bonemarrow. J Immunol Methods 223, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niphakis MJ, and Cravatt BF (2014). Enzyme Inhibitor Discovery by Activity-Based Protein Profiling. Annual Review of Biochemistry 83, 341–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara D, Deng H, Viader A, Baggelaar MP, Breman A, den Dulk H, van den Nieuwendijk AM, Soethoudt M, van der Wel T, Zhou J, et al. signaling networks by acute diacylglycerol lipase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016). Rapid and profound rewiring of brain lipid 113, 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AC, Russell JD, Bailey DJ, Westphall MS, and Coon JJ (2012). Parallel Reaction Monitoring for High Resolution and High Mass Accuracy Quantitative, Targeted Proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 11, 1475–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DR, Gay JP, Wilganowski N, Doree D, Savelieva KV, Lanthorn TH, Read R, Vogel P, Hansen GM, Brommage R, et al. (2015). Diacylglycerol Lipase alpha Knockout Mice Demonstrate Metabolic and Behavioral Phenotypes Similar to Those of Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Knockout Mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 6, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis e Sousa C (2006). Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat Rev Immunol 6, 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisenberg M, Singh PK, Williams G, and Doherty P (2012). The diacylglycerol lipases: structure, regulation and roles in and beyond endocannabinoid, signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367,3264–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, Snyder HW, Donvito G, Schurman LD, Fox TE, Lichtman AH, Kester M, and Hsu KL (2018). Liposomal Delivery of Diacylglycerol Lipase-Beta Inhibitors to Macrophages Dramatically Enhances Selectivity and Efficacy in Vivo. Mol Pharm 15, 721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman RM (2012). Decisions about dendritic cells: past, present, and future. Annu Rev Immunol 30, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura A, Yamazaki M, Hashimotodani Y, Uchigashima M, Kawata S, Abe M, Kita Y, Hashimoto K, Shimizu T, Watanabe M, et al. (2010). The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol produced by diacylglycerol lipase alpha mediates retrograde suppression of synaptic transmission. Neuron 65, 320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deusen KE, Rajapakse R, and Bullock TN (2010). CD70 expression by dendritic cells plays a critical role in the immunogenicity of CD40-independent, CD4+ T cell-dependent, licensed CD8+ T cell responses. J Leukoc Biol 87, 477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viader A, Ogasawara D, Joslyn CM, Sanchez-Alavez M, Mori S, Nguyen W, Conti B, and Cravatt BF (2016). A chemical proteomic atlas of brain serine hydrolases identifies cell type-specific pathways regulating neuroinflammation. Elife 5, e12345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkerson JL, Ghosh S, Bagdas D, Mason BL, Crowe MS, Hsu KL, Wise LE, Kinsey SG,Damaj MI, Cravatt BF, et al. (2016). Diacylglycerol lipase beta inhibition reverses nociceptive behaviour in mouse models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol 173, 1678–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Repository ID for the flow cytometry data corresponding to dendritic cell activation and vaccination experiments of OVA-DEX positive CD8+ splenic T cells is stored as a public dataset FR-FCM-Z2ZQ at FlowRepository (https://flowrepository.org/). The mass spectrometry data for lipidomics analysis of BMDCs is published at Mendeley data (doi:10.17632/45csyctfbn.1; https://data.mendeley.com/datasets).