Abstract

It is widely assumed that inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and ryanodine (Ry) receptors share the same Ca2+ pool in central mammalian neurons. We now demonstrate that in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons IP3- and Ry-receptors are associated with two functionally distinct intracellular Ca2+ stores, respectively. While the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ store refilling requires Orai2 channels, Ry-sensitive Ca2+ store refilling involves voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs). Our findings have direct implications for the understanding of function and plasticity in these central mammalian neurons.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Cellular neuroscience

It is generally assumed, from previous studies in cerebellar Purkinje neurons, that IP3 and Ry receptors share the same intracellular Ca2+ pool. In this study, the authors demonstrate the existence of two functionally distinct Ca2+ stores in mouse CA1 pyramidal neurons by showing that refilling of IP3-sensitive stores relies on Orai2 channels, whereas Ry-sensitive stores involve VGCCs for spontaneous store refilling

Introduction

Ca2+ ions are ubiquitous and versatile signaling molecules that control a plethora of cellular processes in virtually all biological organisms. In mammalian neurons, transient changes in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration control, for example, transmitter release, the induction of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, and gene expression1. A major source of such neuronal Ca2+ signals is Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space through Ca2+-permeable channels, mostly through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) in the plasma membrane. Another essential source is the intracellular release of Ca2+ ions from endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores, which is mediated by two types of receptors in the ER membrane, namely, inositoltrisphosphate (IP3) and ryanodine (Ry) receptors2. Both IP3 and Ry receptors are abundantly expressed in most central mammalian neurons, including CA1 pyramidal neurons (PNs) and cerebellar Purkinje cells3. Although the experimental evidence is rather scarce, it is widely assumed that IP3 and Ry receptors share the same intracellular Ca2+ pool (e.g. ref. 4). However, the intracellular distribution of IP3 and Ry receptors is not homogenous. For example, in Purkinje cells, IP3 receptors are enriched in dendritic spines, while Ry receptors are more abundant in dendritic shafts5. An opposite expression pattern was observed in CA1 PNs6,7. Interestingly, although there is not much support of a strict receptor co-localization, it is believed that IP3 and Ry receptors have largely overlapping cellular functions8.

The homeostasis of the intraluminal Ca2+ concentration in the ER is maintained by Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space9. For example, in CA1 PNs, the refilling of Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores was suggested to be mediated by VGCCs10. However, most central neurons abundantly express STIM (stromal interaction molecules) and Orai3,11,12, which in non-excitable cells form a signaling complex that accounts for the refilling in ER Ca2+13–17. The roles of STIM and Orai in central mammalian neurons are barely understood. Recent studies determined a neuronal cell type-specific expression of STIM homologs, with, for example, STIM1 predominantly present in Purkinje neurons11 and STIM2 predominant in pyramidal3,12. In these neurons, STIM1 and STIM2 are determinants of ER Ca2+11,12. However, the identity and the functions of the corresponding Orai channels is unknown. Here we set out to investigate the specific roles of Orai1 and Orai2 channels for the function(s) of IP3 and Ry receptor-sensitive ER Ca2+ stores in CA1 PNs by using Orai-deficient mouse lines.

Results

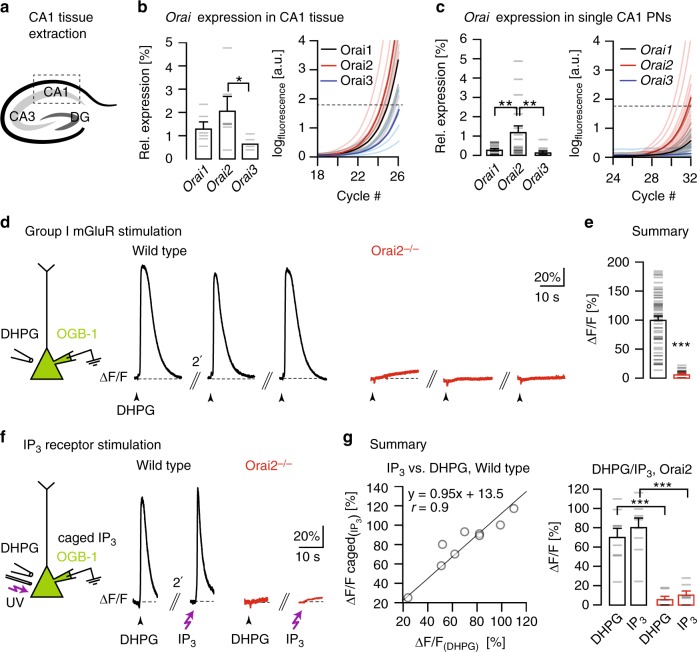

We first analyzed the expression of Orai Ca2+ channels, known to regulate Ca2+ store refilling in non-excitable cells15,16, in mouse CA1 PNs. We determined mRNA expression of all three Orai genes (Orai1–3) in the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus (Fig. 1a–c) by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)18,19 and reliably detected transcripts for all three Orai homologs. The mean expression levels relative to the housekeeping gene Gapdh were 1.3 ± 0.3% for Orai1, 2 ± 0.6% for Orai2, and 0.6 ± 0.1% for Orai3 (n = 6 mice for all; Fig. 1b). The analogous analysis in 6 mice of a mouse line with a targeted deletion of the Orai2 gene (Orai2−/−20) yielded similar relative expression for Orai1 (1.0 ± 0.1%) and Orai3 (0.5 ± 0.9%) and, as expected, the absence of Orai2 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we performed a quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis for the Orai genes on the level of single CA1 PNs18. The mean expression level of Orai2 in single neurons, in contrast to the CA1 tissue, was higher than that of Orai1 and Orai3 (0.3% ± 0.05% for Orai1, n = 21 cells; 1.2 ± 0.3% for Orai2, n = 19 cells; 0.1 ± 0.05% for Orai3, n = 15 cells; Fig. 1c). For immunohistochemical staining of Orai2 expression patterns in CA1, we made use of the fact that in the Orai2−/− mice the protein-coding exons of Orai2 were replaced with a LacZ reporter. Accordingly, in wild-type (WT) mice, β-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside) staining yielded a weak and unspecific staining (Supplementary Fig. 1b, left), whereas a bright signal for β-gal was found in the somatodendritic compartment of CA1 PNs in Orai2−/− mice, confirming both the deletion of the Orai2 gene in the mutant and its expression in the WT mouse lines, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1b, right).

Fig. 1.

Orai2 is required for IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release from internal stores. a Schematic depiction of the hippocampus with the three regions CA1, CA3, and the dentate gyrus (DG). CA1 tissue was extracted for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. b Result of Orai PCR analysis in the mouse hippocampus (P18). Left: Mean expression levels of the three Orai homologs relative to the housekeeping gene Gapdh (n = 6 mice, p = 0.024 (analysis of variance)). Gray dashes represent individual values in this and other figures. Right: Real-time monitoring of the fluorescence emission of SYBR Green I during the PCR amplification of Orai1-3 cDNA. Dashed line: noise band. c Analogous PCR analysis in single CA1 pyramidal neurons (PNs) harvested from acute hippocampal slices. Orai1: n = 21, Orai2: n = 19, Orai3: n = 15 cells; p = 0.002 (Orai1–Orai2), p = 0.001 (Orai2–Orai1). d Left: DHPG was pressure-applied to somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 PNs filled through the patch pipette with OGB-1. Black traces: Ca2+ transients in CA1 PNs in a wild-type mouse (left) in response to repeated applications of DHPG (500 µM, 200 ms) at 2-min intervals. Red traces: Analogous experiments in an Orai2−/− mouse. e Mean amplitudes of DHPG-evoked Ca2+ transients in wild-type and Orai2−/− mice (n = 62 and 33 cells, respectively; p = 9.84 × 10−24). f Left: Both ultraviolet light pulses and local DHPG puffs were applied to somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 PNs filled with OGB-1 and NPE (“caged”)-IP3 through the patch pipette. Black traces: Fluorescence transients resulting from photolysis of caged IP3 (left) and local DHPG puff application (right) in the same cell in a wild-type mouse. Red traces: Analogous experiment in an Orai2−/− mouse. g Left: Correlation plot of relative fluorescence changes in response to IP3-uncaging (y axis) against relative fluorescence changes in response to DHPG applications (x axis) in the same cells in the wild type. Right: Mean amplitudes of relative fluorescence changes in response to both treatments in c in both genotypes (n = 9 cells in wild type and 7 cells in Orai2−/− mice, p = 1.74 × 10−4, p = 3.5 × 10−4). * - significant (p < 0.05), ** - very significant (p < 0.01), *** - highly significant (p < 0.001)

We analyzed the functional status of IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores by locally applying to CA1 PNs 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), an agonist of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1 and mGluR5), known to be abundantly expressed3 and of major functional importance in these neurons21. Fig. 1d, e demonstrates that DHPG application reliably evoked Ca2+ release signals from stores (see Supplementary Fig. 2a–d) in WT mice (left) but not in Orai2-deficient (Orai2−/−) mice (right) (see also control experiments in Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, the deletion of Orai1 had no detectable impact on the Ca2+ release signals from stores (see Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). Thus Orai channels in CA1 PNs differ functionally from those expressed in electrically non-excitable immune cells, where the deletion of Orai1 reduces SOCE while deletion of Orai2 increases SOCE20. Next, we explored the reason for the absence of DHPG-induced Ca2+ transients by testing the effect of photolysis of NPE-caged IP3 (myo-inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate, P(4,5)-1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl ester). We combined recordings of DHPG applications and IP3 uncaging in the same CA1 PNs and found similar responsiveness and unresponsiveness patterns in WT and Orai2−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 1f, g). Together, these results established a requirement of Orai2 for the normal function of IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores in CA1 PNs.

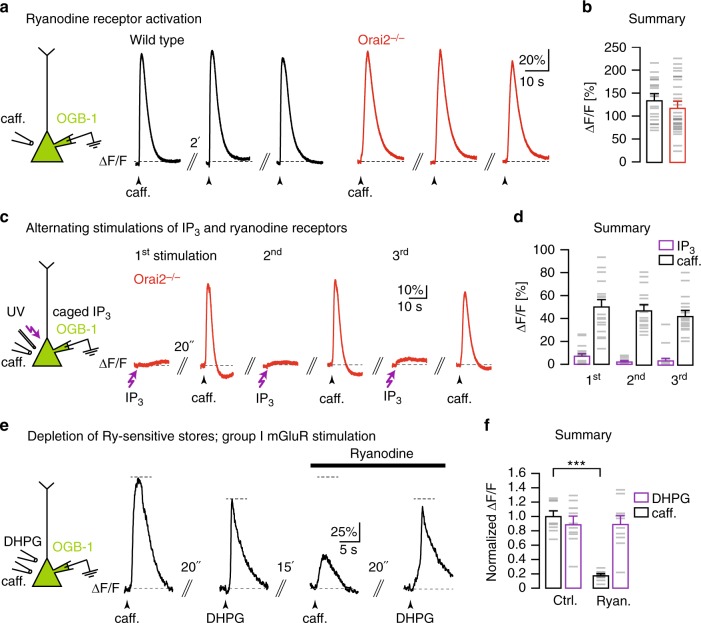

How about Ry-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ stores? Earlier work had established that, in CA1 PNs, RyRs can be effectively activated by local application of caffeine10. We confirmed this effect in WT mice (Fig. 2a, left). Surprisingly, however, caffeine-induced Ca2+ release from stores (Fig. 2e, f) was unaltered both in Orai2−/− mice (Fig. 2a, right, Fig. 2b) and in Orai1-deficient mice (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). By using IP3 uncaging in combination with caffeine application in the same CA1 PNs, we verified that RyR-dependent Ca2+ release worked even in the absence of IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release from internal stores in Orai2−/− mice (Fig. 2c, d) as well as in WT mice when IP3-sensitive stores were depleted (Supplementary Fig. 5). In order to test the functional independence of IP3R- and RyR-dependent Ca2+ release, we designed an experiment in which we applied DHPG and caffeine sequentially to the same CA1 PNs. Fig. 2e, f demonstrates that incubation with Ry caused the well-known strong suppression of caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transients10, while DHPG-evoked Ca2+ transients were hardly affected at all. Together, the results presented in Fig. 2c–f and in Supplementary Fig. 5 indicate that IP3R- and RyR-dependent Ca2+ stores can release Ca2+ independently from each other.

Fig. 2.

Orai2 is not required for RyR-dependent Ca2+ release from internal stores. a Left: Caffeine was locally applied to the somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 pyramidal neurons (PNs) filled with OGB-1 through the patch pipette. Black traces: Fluorescence transients in response to three consecutive caffeine applications with an interval of 2 min in a wild-type mouse. Red traces: Analogous experiment in an Orai2-deficient mouse. b Summary of the experiments in a. Bar graph shows the mean amplitudes of relative fluorescence changes resulting from the first caffeine application in each cell (n = 20 cells in wild-type and n = 28 cells in Orai2−/− mice, p = 0.268). c Left: Both caffeine and ultraviolet pulses were applied to somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 PNs filled through the patch pipette with NPE (caged)-IP3 and OGB-1. Red traces: Fluorescence transients resulting from three cycles of alternating somatic IP3 uncaging and caffeine applications in an Orai2−/− mouse. d Summary of experiments in c. Bar graph showing the mean amplitudes of responses to caffeine (white) and IP3 uncaging (purple; n = 18 cells). e Left: Both caffeine and 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) were locally applied to the somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 PNs filled with OGB-1 through the patch pipette. Traces: Fluorescence transients in response to somatic caffeine and DHPG applications with the indicated time intervals in control artificial cerebrospinal fluid (left traces) and in the presence of 10 µM ryanodine (right traces). f Summary bar graph showing mean amplitudes of relative fluorescence changes for all experiments (n = 10 cells, p = 7.89 × 10−9) in e. *** - extremely significant (p < 0.0001)

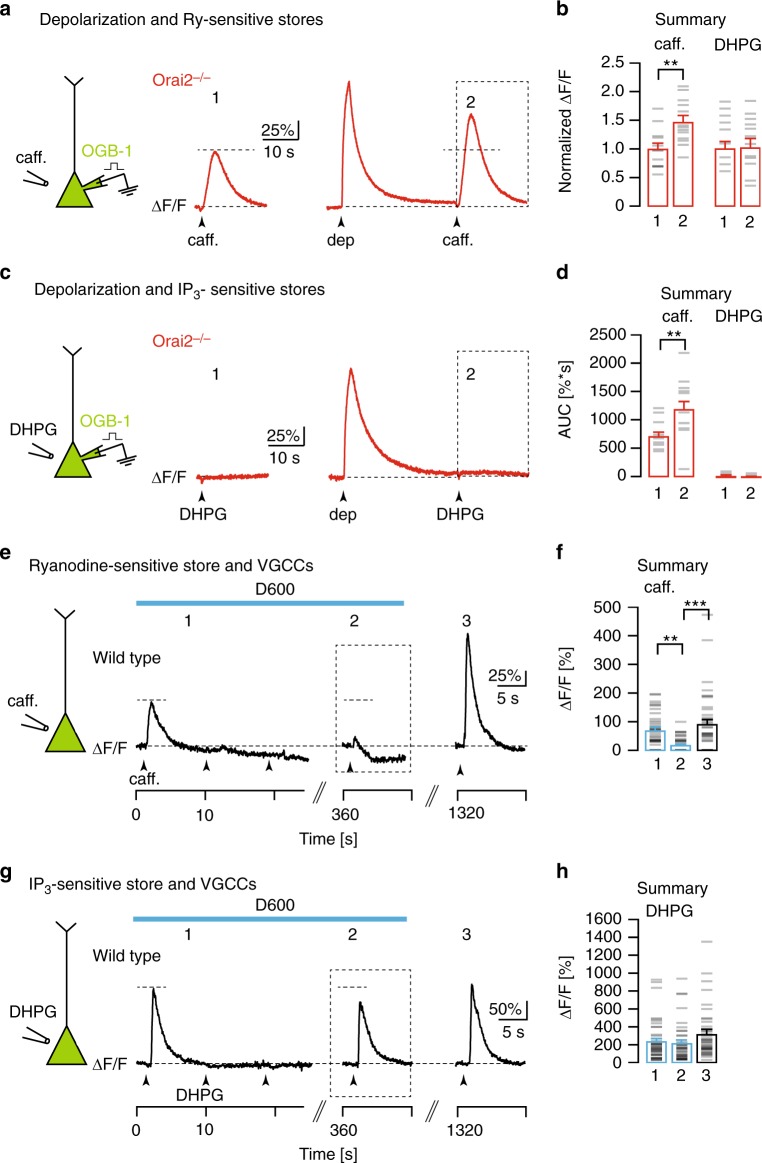

The functional independence of IP3- and Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores was strongly supported by two additional lines of experiments. In a first series of experiments illustrated in Fig. 3a–d, we tested the “overcharging” phenomenon of Ca2+ stores10,11. The results show that, 30 s following a depolarizing pulse, causing Ca2+ entry through VGCCs, there was a marked increase of the caffeine-evoked Ca2+ transient in a CA1 PN from an Orai2−/− mouse (Fig. 3a, c, d). By contrast, depolarization was ineffective when applying DHPG in Orai2−/− mice (Fig. 3b-d), although “overcharging” of IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores was previously shown to work reliably in cerebellar Purkinje neurons of WT mice11. In a second series of experiments, we compared the role of VGCCs for IP3- and Ry-sensitive Ca2+ store refilling. In line with earlier observations10, we confirmed an antagonist of VGCCs, D600, prevented the replenishment of depleted RyR-dependent Ca2+ stores (Fig. 3e, f). D600 effectively abolished depolarization-evoked Ca2+ responses but not RyR-dependent Ca2+ release in CA1 PNs (Supplementary Fig. 6). At the same time, the spontaneous replenishment of depleted IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores (Supplementary Fig. 7) was only marginally affected by the presence of D600 (Fig. 3g, h). In addition to D600, we also tested more specific Ca2+ channel antagonists and found that a cocktail of antagonists for L/PQ/T/R-type Ca2+ channels had a similar blocking effect of depolarization- and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, in contrast to IP3-sensitive stores that almost entirely rely on Orai2 for Ca2+ homeostasis, Ry-sensitive stores seem to require VGCCs for spontaneous refilling at resting membrane potential and can be overcharged by depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx through VGCCs.

Fig. 3.

Orai2-independent replenishment and overcharging of Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores. a Left: Caffeine was locally applied to the somata of whole-cell patch-clamped CA1 pyramidal neurons (PNs) filled with OGB-1 through the patch pipette. Red traces: Fluorescence recordings in an Orai2−/− mouse in response to applications of caffeine before (1), and 30s after (2) a depolarization to 0 mV for 1 s. b Summary of the experiments shown in a (left bars) and c (right bars). Bar graph showing mean amplitudes of relative fluorescence changes in response to caffeine (a, n = 13 cells, p = 0.0014) or 3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG; c, n = 17 cells, p = 0.65) application before (1) and after the depolarization (2), normalized to the control amplitude (1). c Analogous experiment in another CA1 PN from the same mouse with DHPG applied after the depolarization. d Mean area under the curve for 15 s following the caffeine (2) and DHPG (3) applications following the depolarization (marked by dashed boxes in a and b, caffeine: p = 0.01, DHPG: p = 0.831). e Left: Caffeine was locally applied to somata of CA1 PNs filled with Cal520-AM by multi-cell bolus loading (MCBL). Traces: Fluorescence recordings from the soma of a single CA1 PN in a wild-type mouse during consecutive caffeine applications (arrowheads) in the presence of D600 (blue bar) and after washout of D600. f Summary of the experiments shown in e. Mean amplitudes of relative fluorescence changes in response to caffeine applications at the time points indicated in e (n = 41 cells, analysis of variance (ANOVA): p = 0.001 (1 vs 2) and p = 4.98 × 10−6 (2 vs 3). g Analogous experiment to e with DHPG instead of caffeine applications. h Analogous summary to f for the experiments shown in g (n = 41 cells, ANOVA: p = 0.694 (1 vs 2) and p = 0.058 (2 vs 3)). ** - very significant (p <= 0.01), *** - extremely significant (p <= 0.0001)

Discussion

In conclusion, several lines of evidence establish that IP3- and Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores are functionally largely independent in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. First, IP3R-dependent Ca2+ release is functional in conditions in which Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores are depleted or pharmacologically inactivated and vice versa for caffeine-dependent Ca2+ release. Second, Orai2 is selectively involved in the replenishment of IP3- but not Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores. Third, by contrast, VGCCs are involved in the replenishment of Ry- but not IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores. Fourth, depolarization-dependent overcharging of Ca2+ stores persists in Orai2−/− mice for caffeine-dependent but not for DHPG-dependent Ca2+ release from internal stores. Ry-sensitive stores that are functionally separate from IP3-sensitive stores have been previously reported in non-neuronal cells22,23 but not in central neurons8. However, the hypothesis of Ry and IP3 receptors sharing the same Ca2+ pool is solely based on IP3 uncaging experiments in cerebellar Purkinje4 without further molecular validation. Therefore, a first step in resolving the apparent discrepancy between hippocampal and Purkinje neurons may be an analysis of the role(s) of Orai channels in Purkinje neurons.

The functional independence of IP3- and Ry-sensitive Ca2+ stores in CA1 PNs is unexpected in view of the evidence that the ER forms a continuous network in neurons24. Possibly, the functional separation of the stores is the result of the clustering of IP3Rs and RyRs at sufficiently long distances within the ER network, with IP3Rs co-localizing with Stim molecules and Orai2, while RyRs co-localize with not yet identified types of VGCCs. Finally, our results help explain the distinct roles of IP3Rs and RyRs for various forms of long-term potentiation and long-term depression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells25–31 and thus promote the development of specific molecular targets needed for a deeper analysis.

Methods

Mice

All experimental procedures were in compliance with institutional animal welfare guidelines and were approved by the state government of Bavaria, Germany. Mice were maintained in an animal facility under a 12-h light/dark cycle and food and water was provided ad libitum. All the animal experiments were performed in accordance with the policies established by institutional animal welfare guidelines of the government of Bavaria, Germany. Orai1loxP/− and Orai1CA1KO/− mice were generated by breeding mice with loxP-flanked exons 2 and 3 in the Orai1 gene32 to mice with a heterozygous expression of Cre under the control of the αCaMKII-promoter (T29-1)33. Cre/loxP recombination in the resulting offspring generates two types of genotypes: a CA1-PN-specific (CA1KO)33 or a general deletion (−) of the Orai1 gene (own finding). In the latter mouse line, we heterozygously preserved the loxP-flanked Orai1 gene and thus generated Ora1loxP/− mice. Orai1CA1ko/− mice were created by using appropriate breeding steps and careful genotyping. The procedures for Orai2 gene targeting and the generation of Orai2-deficient mice (Orai2−/−) have been previously reported20.

The genotypes of Orai1loxP/−, Orai1CA1ko/−, T29-1 mice, and Orai2−/− mice were confirmed by PCR of tail tissue. The loxP sites on the Orai1 locus were confirmed by the following primer pairs: Orai1loxP forward: 5’-CAG CGT GCA TAA TAT ACC TAA CTC TAC CCG-3’ and Orai1LoxP reverse: 5’-GTA TTG ATG AGG AGA GCA AGC GTG AAT C-3’; product size: WT 220 bp, Orai1CA1ko/−: 360 bp. The heterozygous deletion of Orai1 was verified by the use of Orai1KO forward: 5’-GGC TGG GAG ACA CTA ACT TCC TAA GG-3’ and Orai1KO reverse: 5’-CAT ATT GTG ACG GGA GGT TTG CAG-3’; product size: WT 1890 bp, Orai1KO: 400 bp. The genotype of T29-1 mice was verified by the following primers: Cre forward 5’-GCC GAA ATT GCC AGG ATC AG-3’ and Cre reverse 5’-AGC CAC CAG CTT GCA TGA TC-3’; product size: 420 bp. Orai2−/− mice were confirmed by the use of the following primer pair: (Orai2−/− forward: 5’-ACA CGA GTC TCT TCT GTC GG-3’ and reverse: 5’-CAT CTA CCT GCC CCT ATC-3’; product size: ca. 700 bp).

mRNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

CA1 tissue was excised from the mouse brains at P18. Subsequently, tissue mRNA was extracted by the use of a RNA isolation kit, NucleoSpin RNA Plus (Machery-Nagel, Germany). Purified tissue RNA was incubated in gDNA Wipeout Buffer (QuantiTect; Qiagen) for 2 min at 42 °C to remove genomic DNA. RT was performed by the use of the QuantiTect® Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Germany). After RT, 5 ng of cDNA from each sample was collected for further qPCR analysis.

Single-cell qPCR was performed as previously described18. Briefly, CA1 pyramidal neurons were collected through a glass pipette with the resistance of 1–3 MΩ, which was filled with (in mM) 50 Tris-HCl (pH8.3), 75 KCl, 3 MgCl2, and 10 dithiothreitol (Promega, USA). After the tip of the pipette reached the membrane of an individual pyramidal neuron in CA1 region, negative pressure was applied to move the cell into the tip of the pipette. The pipette with cell inside was immediately transferred into an RNAse-free Eppendorf tube and frozen in liquid nitrogen and then placed at −80 °C for long-term storage for further RT reaction. For RT, cells were de-frozen at 0 °C and mixed with RT cell lysis buffer, which contained 2 mM dNTPs (Promega), 0.2% Igepal (Sigma), 40 U RNAsin® Plus RNAse Inhibitor (Promega, USA), 10 µM N6 random primers (Roche, Germany) at 70 °C for 5 min. After 5 min, 200 unit (U) of MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA) were added to start the RT reaction. RT was carried on at 37 °C for 2 h. A QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used for cDNA clean-up for the following LightCycler (Roche) qPCR reaction.

Five ng of tissue cDNA or 80% of the total extracted single-cell extracted cDNA per cell were mixed with the qPCR reaction solution “LightCycler Faststart DNA Master SYBR Green I” (Roche) and 0.5 µM of primer sets to amplify Orai1 (accession number NM 175423, forward: 5’-CCT GTG GCC TGG TTT TTA TC-3’ and reverse: 5’-GTG CCC GGT GTT AGA GAA TG-3’; product size: 160 bp), Orai2 (accession number AM712356, forward: 5’-ACC ATG AGT GCA GAG CTC AA-3 and reverse: 5’-GAG CTT CCT CCA GGA CAG TG-3’; product size: 162 bp), Orai3 (accession number NM 198424, forward: 5’-GGG TAA ACC AGC TCC TGT TG-3’ and reverse: 5’-GCC TGG TCC ATG AGC ACT AT-3’; product size: 166 bp), Itpr1 (accession number NM 010585, PrimerBank ID 6754390a1, forward: 5’-GGG TCC TGC TCC ACT TGA C-3’ and reverse: 5‘-CCA CAT CTT GGC TAG TAA CCA G-3’; product size: 144 bp), Itpr2 (accession number NM 019923, PrimerBank ID 26326875a1, forward: 5’-TTC AGT TCC TAT CGA GAG GAT GT-3’, and reverse: 5’-GCT GAT TGA CGC AAG GTC G-3’; product size: 140 bp), Itpr3 (accession number NM 080553, PrimerBank ID 162287074c2, forward: 5’-AAG TAC GGC AGC GTG ATT CAG-3’ and reverse: 5’-CAC GAC CAC ATT ATC CCC ATT G-3’; product size: 189 bp) and Gapdh (accession number BC 095932 forward: 5’-AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TT-3′ and reverse: 5´-TGT AGA CCA TGT AGT TGA GGT CA-3; product size: 141 bp). Itpr1, Itpr2, and Itpr3 primer sets are from PrimerBank34. Five ng of tissue cDNA or 10% of total harvested extraction was used for measuring the expression level of the house-keeping gene, Glyceraldehyde dehydrogenase (Gapdh) as internal control for later normalization. The relative expression level of each gene was measured by the following formula:

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

The crossing point (Cp) is calculated as the number of the reaction cycle in which the fluorescence intensity of SYBR Green I reaches a value above the noise level. In order to avoid genomic DNA contamination, samples that showed a positive signal without prior RT reaction were discarded from further analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining

Mice were lethally anesthetized by isoflurane and then transcardially perfused with cold 4% paraformaldehyde solution (PFA; Merck). The brain was removed and post fixed with 4% PFA overnight at 4 °C. Then 70-μm sections were cut using a vibratome (Leica). For staining, slices were permeabilized for 15 min in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS), which contained 0.3% Triton-X-100 (Carlroth, Germany) at room temperature. Brain sections were blocked in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by primary antibody hybridization overnight at 4 °C with chicken-anti-β-galactosidase antibody (1:100; Abcam) in 1% FBS. On the next day, slices were washed 10 min for three times in PBS containing 0.5% tween-20 (Sigma), and incubated with donkey-anti-IgY 649 Alexa Fluor (1:1000; Molecular probe) for 2 h at room temperature. After 10-min washing in PBS with 0.5% tween-20 for three times, brain slices were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma) to visualize cell nucleus and mounted by VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting medium (Vector, USA). Images were acquired with a confocal laser scanning microscope (FLUOVIEW FV3000, Olympus; Japan). Images were processed with the ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop CS5 software (Adobe, USA).

Acute hippocampal slice preparation

WT, Orai1loxp/−, Orai1CA1ko/−, and Orai2−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background at postnatal days P17 to P22 were used in the experiments. After the mice were deeply anesthetized with CO2 and decapitated, the brain was immediately removed and immersed in ice-cold slicing solution containing (in mM) 24.7 glucose, 2.48 KCl, 65.47 NaCl, 25.98 NaHCO3, 105 sucrose, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 1.7 ascorbic acid (Fluka, Switzerland). The pH value was adjusted with to 7.4 with HCl and stabilized by bubbling with carbogen, which contained 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and the osmolality was 290–300 mOsm. Horizontal hippocampal slices 300 μm were cut in the slicing solution by the use of vibratome (VT1200S; Leica, Germany). Brain slices were kept in the recovering solution, which contained (in mM) 2 CaCl2, 12.5 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 thiourea (Sigma, Germany), 5 Na-ascorbate (Sigma), 3 Na-pyruvate (Sigma), and 1 glutathione monoethyl ester (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) at room temperature for at least 1 h before the experiment. The pH value of the recovering solution was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl and constantly bubbled with carbogen, and the osmolality was 290 mOsm.

Electrophysiological recordings

After resting in the recovery solution for at least 1 h, individual hippocampal slices were transferred to the recording chamber, which was constantly perfused at a flow rate of 2 ml/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 2 CaCl2, 20 glucose, 4.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, and 1.25 NaH2PO4 and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 to ensure oxygen saturation and to maintain a pH value of 7.4. In all, 30 μM D-AP5 (Abcam and Tocris, USA), 10 μm GYKI53655 (Tocris), and 10 μm bicuculline (Enzo, USA) were added to the ACSF to block NMDAR-, AMPAR-, and GABAAR-mediated synaptic transmission. The ACSF also contained 500 nM tetrodotoxin citrate (Abcam). Somatic whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons were performed with a borosilicate glass pipette with the resistance of ca. 7 MΩ filled with internal solution, which contained (in mM) 110 K-gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.24 Na-GTP, 20 Na-Phosphocreatine (Sigma), and 100 μM of the fluorescent calcium indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 hexapotassium salt (OGB-1; Kd 200 nM) (Molecular Probes, USA).The pH value of internal solution was adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. Voltage-clamp measurements were carried out using an EPC9/2 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA, Germany). The membrane potential was held at −70 mV in voltage-clamp mode without liquid junction potential adjustment. Data acquisition and the generation of stimulation protocols were applied by the use of PULSE software (HEKA). Data were collected at 10 kHz and Bessel-filtered at 2.9 kHz and analyzed by the Igor 5 software (Wavemetrics, USA).

Drug application

Depending on different purposes of experiments, the ACSF with antagonists against NMDARs, AMPARs, GABAARs, and voltage-gated sodium channels was used for bath application of the following drugs: cyclopiazonic acid (30 μM, Sigma), Ry (10 μM; Tocris), thapsigargin (5 μM, Sigma), D600 (500 μM, Sigma), nimodipine (20 μM ; Sigma), SNX-486 (0.5 μM; Tocris and Alomone), ω-Agatoxin IVA (0.2 μM; Peptide institute INC., Japan), and NiCl2 (75 μM; Sigma) as indicated in the respective “Results” section. Ca2+-free ACSF contained (in mM) 0.1 mM ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (EGTA; Sigma), 20 glucose, 4.5 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, and 1.25 NaH2PO4. Local drug application was performed by a glass pipette with the resistance of 8 MΩ, which was connected to a Picospritzer II (Parker instrumentation, general valve, USA). The mGluR1/5 agonist DHPG (500 μM; Abcam) was dissolved in ACSF and Ry receptor agonist caffeine (40 mM, Sigma) was diluted in caffeine ringer, which contained (in mM) 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2.6H2O, 120 NaCl, and 1.25 NaH2PO4. The pipette tip was placed at a distance of 15–20 μm from the cell soma.

Calcium imaging

CA1 pyramidal neurons were dialyzed with an internal solution containing 100 μM of the calcium indicator OGB-1 after the whole-cell configuration was established. Alternatively, somata of pyramidal neurons were stained via multi-cell bolus loading (Stosiek et al.35) by pressure-application of 1 mM acetoxymethyl ester of the calcium-sensitive fluorescent dye Cal-520 (Cal-520-AM; Kd: 320 nM, AAT-Bioquest, USA) in the staining solution using a Picospritzer. The preparation of the staining solution and the staining procedure were performed according to a standard protocol35. An upright multi-point confocal microscope (E600FN; Nikon, Japan) with a dual spinning disk (QLC 100; VTi, UK) was used for fluorescence image recording. A ×40 water-immersion objective with a numerical aperture (NA) 0.8 (Nikon, Japan) or a ×60 water-immersion objective with NA 0.9 (Nikon) were used for image acquisition. A 488-nm single wavelength Sapphire laser (Coherence, USA) was used for generating single-photon excitation of the Ca2+ indicator. The laser power under the objective was set to <0.15 mW. A CCD camera (NeuroCCD; RedShirt imaging, USA) with a resolution of 80 × 80 pixels was attached to the microscope for image acquisition. In order to synchronize the spinning disk and CCD camera during imaging, a function generator (TG1010A; TTi, UK) was used during recording. Image sequences were acquired by the use of Neuroplex software (RedShirt Imaging, USA) and analyzed with ImageJ with the help of the plug-in “Time Series Analyzer” (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/plugins/time-series.html; NIH, USA). The fluorescence intensity in each somatic region of interest (ROI) (Supplementary Fig. 9) was corrected by background subtraction. A ROI immediately outside of the neuron was taken as background. Temporal fluorescence intensity changes in ROIs were expressed as relative percentage changes in fluorescence intensity: ΔF/F (%) = ((F − F0)/F0). F0 is defined as baseline fluorescence, which means the fluorescence intensity before a given stimulus, and F is the fluorescence change over time. ΔF/F (%) values were calculated and plotted using Igor Pro 5 (Wavemetrics, USA).

IP3 uncaging

For photolytic release of IP3 experiments, 0.4 mM of NPE-IP3 (Invitrogen, USA) was supplemented in the internal solution. A tapered lensed optical fiber (working distance 6 ± 1 mm, spot diameter 6 ± 1 mm; Nanonics, Israel) was connected to a diode laser (Coherent Cube; 375 nm, 15 mW at the laser head) and placed on to the surface of the slice. Photolysis of caged IP3 was accomplished by a single light pulses for 50 ms through the optical fiber.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SEM and plotted using Sigmaplot v.10 (Systat Software Inc., USA), unless noted otherwise. All statistical analysis was done with the use of the IBM SPSS statistics v.17 software (IBM, USA). Normal distribution was assessed with Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical tests performed were two sided. For data sets with two independent experimental groups, independent Student’s t test was used for normally distributed data. For nonparametric (non-normally distributed) data, Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis. For two related experimental groups, paired Student’s t test was applied for normal distributed data or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test for nonparametric data. To compare more than two experimental groups, one-way analysis of variance test [post hoc Least Significant Difference] was used. The linear fit and Pearson’s r in Fig. 1g were calculated using Sigmaplot v.10 (Systat Software Inc., USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Christine Karrer, Petra Apostolopoulos, and Christian Obermayer for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 870) and European Research Council Advanced Grants to A.K. and by NIH grants AI097302, AI130143, and AI137004 to S.F. A.K. is a Hertie-Senior-Professor for Neuroscience.

Author contributions

J.H. and A.K. designed research. H.-J.C.-E., J.H., R.M.K., J.Y., S.F., and A.K. performed research. H.-J.C.-E., J.H., and A.K. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data support the findings of this study (see Source Data) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer Review Information: Nature Communications thanks Ilya Bezprozvanny and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hsing-Jung Chen-Engerer, Jana Hartmann.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-11207-8.

References

- 1.Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lein ES, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berna-Erro A, et al. STIM2 regulates capacitive Ca2+ entry in neurons and plays a key role in hypoxic neuronal cell death. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra67. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton PD, et al. Ryanodine and inositol trisphosphate receptors coexist in avian cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1145–1157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharp AH, et al. Differential cellular expression of isoforms of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors in neurons and glia in brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;406:207–220. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990405)406:2<207::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal M, Vlachos A, Korkotian E. The spine apparatus, synaptopodin, and dendritic spine plasticity. Neuroscientist. 2010;16:125–131. doi: 10.1177/1073858409355829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verkhratsky A. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reticulum of neurons. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:201–279. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grienberger C, Konnerth A. Imaging calcium in neurons. Neuron. 2012;73:862–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garaschuk O, Yaari Y, Konnerth A. Release and sequestration of calcium by ryanodine-sensitive stores in rat hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 1):13–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.013bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann J, et al. STIM1 controls neuronal Ca2+ signaling, mGluR1-dependent synaptic transmission, and cerebellar motor behavior. Neuron. 2014;82:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berna-Erro A, et al. STIM2 regulates capacitative Ca2+ entry in neurons and plays a key role in hypoxic neuronal cell death. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra67. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penna A, et al. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;456:116–U112. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frischauf I, et al. The STIM/Orai coupling machinery. Channels. 2008;2:261–268. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.4.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels: new perspectives on mechanism and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a003970. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2015;95:1383–1436. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soboloff Jonathan, Spassova Maria A., Tang Xiang D., Hewavitharana Thamara, Xu Wen, Gill Donald L. Orai1 and STIM Reconstitute Store-operated Calcium Channel Function. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(30):20661–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand GM, Marandi N, Herberger SD, Blum R, Konnerth A. Quantitative single-cell RT-PCR and Ca2+ imaging in brain slices. Pflug. Arch. 2006;451:716–726. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1514-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann J, et al. Distinct roles of Gαq and Gα11 for Purkinje cell signaling and motor behavior. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5119–5130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4193-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaeth M, et al. ORAI2 modulates store-operated calcium entry and T cell-mediated immunity. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14714. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura T, et al. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated Ca2+ release evoked by metabotropic agonists and backpropagating action potentials in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8365–8376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabr RI, Toland H, Gelband CH, Wang XX, Hume JR. Prominent role of intracellular Ca2+ release in hypoxic vasoconstriction of canine pulmonary artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:21–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn ER, Bradley KN, Muir TC, McCarron JG. Functionally separate intracellular Ca2+ stores in smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36411–36418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terasaki M, Slater NT, Fein A, Schmidek A, Reese TS. Continuous network of endoplasmic reticulum in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7510–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Futatsugi A, et al. Facilitation of NMDAR-independent LTP and spatial learning in mutant mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 3. Neuron. 1999;24:701–713. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81123-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujii S, Matsumoto M, Igarashi K, Kato H, Mikoshiba K. Synaptic plasticity in hippocampal CA1 neurons of mice lacking type 1 inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Learn. Mem. 2000;7:312–320. doi: 10.1101/lm.34100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishiyama M, Hong K, Mikoshiba K, Poo MM, Kato K. Calcium stores regulate the polarity and input specificity of synaptic modification. Nature. 2000;408:584–588. doi: 10.1038/35046067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu YF, Hawkins RD. Ryanodine receptors contribute to cGMP-induced late-phase LTP and CREB phosphorylation in the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1270–1278. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taufiq AM, et al. Involvement of IP3 receptors in LTP and LTD induction in guinea pig hippocampal CA1 neurons. Learn. Mem. 2005;12:594–600. doi: 10.1101/lm.17405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raymond CR, Redman SJ. Spatial segregation of neuronal calcium signals encodes different forms of LTP in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 2006;570:97–111. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konieczny V, Tovey SC, Mataragka S, Prole DL, Taylor CW. Cyclic AMP recruits a discrete intracellular Ca(2+) store by unmasking hypersensitive IP3 receptors. Cell Rep. 2017;18:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Somasundaram A, et al. Store-operated CRAC channels regulate gene expression and proliferation in neural progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:9107–9123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0263-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsien JZ, et al. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Seed B. A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stosiek C, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K, Konnerth A. In vivo two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:7319–7324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data support the findings of this study (see Source Data) are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.