Abstract

Purpose

The aim is to summarize and evaluate current systematic reviews and meta-analyses on MTHFR polymorphisms in recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL).

Methods

We searched Pubmed and Embase databases and selected in form of PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design). Our methodology was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017042762). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses containing primary studies were extracted for meta-analyses, along with their OR and 95%CI. We assessed the quality of the included studies using AMSTAR and OQAQ criteria.

Results

Eleven systematic reviews and meta-analyses were identified. C677T was significantly related to RPL overall in Allele (OR, 95%CI 1.43, 1.29–1.60), Recessive (OR, 95%CI 1.66, 1.42–1.95), and Homozygous (OR, 95%CI 2.08, 1.66–2.61). There was no correlation observed between A1298C and RPL, except for in Heterozygous (OR, 95%CI 1.62, 1.17–2.25).

Conclusions

We identified a difference in the association between MTHFR C677T polymorphism and RPL, especially in Asian population. No significant correlation was found between A1298C and RPL.

Keywords: Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), Methalenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), Polymorphism, C677T, A1298C, Systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is defined as two or more consecutive spontaneous miscarriages before 20 weeks of gestation. RPL affects at least 2% of women in reproductive age. Despite anatomical abnormalities, autoimmune diseases, and environmental factors, the causes of RPL in 50% of cases are still unknown [1]. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) plays a critical role in the folate pathway, which is widely believed to play a key role in pregnancy outcome. MTHFR gene is located on chromosome 1p36.6 and features 11 exons. Polymorphisms of MTHFR, especially C677T (rs1801133) and A1298C (rs1801131), are believed to be associated with RPL [2]. These mutations cause a reduction in the activity of MTHFR, a vital enzyme which catalyzes 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF). Then, the reduction of 5-MTHF, which participates in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, results in elevated levels of total homocysteine (tHcy) in both blood and urine [2]. Subsequently, hyperhomocysteinemia, or homocystinuria, can induce inherited thrombophilia, a significant risk factor for RPL [3]. Accumulation of homocysteine is also associated with arteriosclerosis, pre-eclampsia, and neural tube defects [4].

A few systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated the correlation between MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL; however, the outcome on this work remains controversial as results have been inconsistent. The reasons for such discrepancies may be related to differences in ethnicities and the selection of primary case-control studies. The accumulation of primary case-control studies may also contribute to variation in views of different authors in term of MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL [4].

Therefore, in the present study, we conducted an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in a comprehensive manner, including different ethnicities and genotype models, in order to assess the association between MTHFR genotype variants and the risk of RPL. A citation matrix was created to analyze the influence of selection in primary studies by different authors. Cumulative meta-analyses were also performed to investigate the tendency of results in genotype models with possible risk for RPL. We also evaluated systematic reviews with Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) and Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) scales to assess the quality of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses which have already been published on this topic.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We identified potential articles by searching Medline and Embase databases with the following key terms: “recurrent pregnancy loss”; “recurrent miscarriage”; “spontaneous abortion”; “methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase”; “MTHFR”; “homocysteine”; “polymorphisms”; “single nucleotide polymorphisms”; and “SNP”. Only systematic reviews and meta-analyses that had been published in English were included.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

According to methodology registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017042762), two researchers independently screened and selected potential articles in accordance with the following eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) concerning the association between MTHFR C677T or A1298C polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss; (2) human studies; (3) systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Exclusion criteria: (1) reviews, comments, editorials; (2) animal studies; (3) without the number of pregnancy losses ≥ 2; (4) controls without having at least one successful live birth

In form of PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design), the study was described as follows [5]:

P: women with two or more pregnancy losses;

I: N/A;

C: women with at least one successful live birth;

O: MTHFR polymorphisms including C677T or A198C;

S: systematic reviews and meta-analysis; case-control studies in the systematic reviews included

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers (Boran-Du, Xiangjun-Shi) screened titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. Studies which met the inclusion criteria were evaluated with full text. For the articles finally included, two reviewers independently extracted the following information: first author, year of the publication, ethnicity, and frequencies of MTHFR in cases and controls. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion. If necessary, a third reviewer (Xin-Feng) made the final decision with regard to discrepancies.

We assessed the methodological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses with Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) [6], which consists of 11 items relating to search bias, selection, and the process of data synthesis. The quality of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included was also evaluated using Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) scale [7], which consists of 9 items and a final total score item. In this research study, we omitted the last item in comparison to AMSTAR scale.

Data synthesis

We described and synthesized data from all selected publications. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was used to compare differing results from systematic reviews relating to associations between MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL. Data synthesis was performed with Stata 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided p value < 0.5 was considered to be statistically significant. Heterogeneity was identified if I2 > 50%, and a random-effect model was used to synthesize data. In order to explore the optimal genotype model of MTHFR and its relationship with RPL, we analyzed a range of different genetic models including Allele model, Dominant model, Recessive model, Homozygous model, and Heterozygous model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genotype contrast model of MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL(C677T and A1298C)

| Contrast model | C677T | A1298C |

|---|---|---|

| Allele | T/C | C/A. |

| Dominant | CT+TT/CC | AC+CC/AA |

| Recessive | TT/CT+CC | CC/AC+AA |

| Homozygous | TT/CC | CC/AA |

| Heterozygous | CT/CC | AC/AA. |

Results

Literature searches and study selection

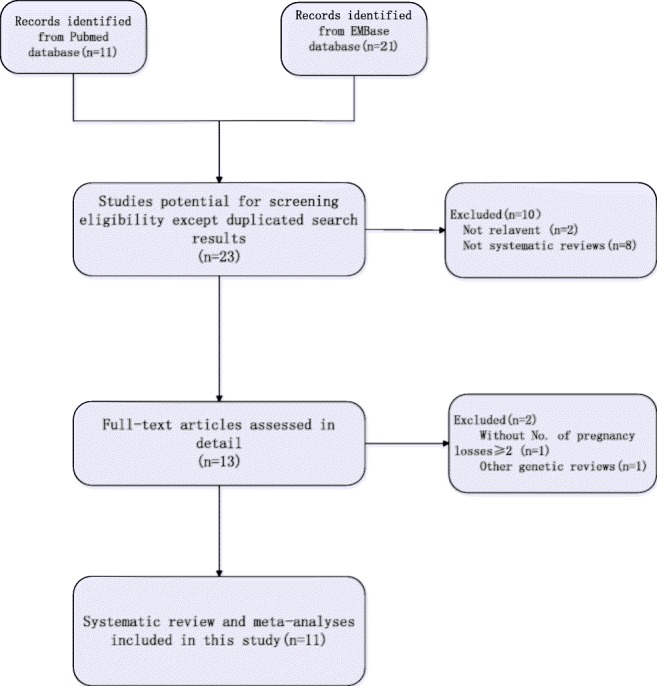

Our initial search generated 29 articles, of which 16 were excluded due to the duplication of results (n = 8) [8–15], non-relevance (n = 2) [16, 17], or the fact that they were not systematic reviews and meta-analyses (n = 6) [18–23] (Fig. 1). After full-text screening, 2 studies were removed according to the eligibility criteria (without the number of pregnancy losses ≥ 2 [24], which did not concern MTHFR polymorphisms [25]). Finally, 11 reviews and meta-analyses remained; all of these were published in English between 2000 and 2016.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of selection of systematic reviews published

Characteristics of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in this study

The characteristics of the 11 systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in our final analysis are summarized in Table 2. These publications all focused on the correlation between RPL and MTHFR polymorphisms, of which there were 9 reviews related to C677T and 5 reviews related to A1298C (Table 2). The number of primary studies included in each systematic review ranged from 6 to 53. There were ten systematic reviews which involved the analysis of ethnicity and MTHFR polymorphisms; one of these was especially focused on Asian population while another focused on Chinese population. Two reviews were partial systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The researchers (Nair, 2013 [10]; Parveen, 2013 [27]) of these two reviews conducted a case-control study in their own country and compared with results of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses they executed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of systematic reviews included

| Author | Year of publication | C677T | A1298C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of studies | Case number | Control number | Conclusion | Number of studies | Case number | Control number | Conclusion | ||

| Nelen [11] | 2000 | 6 | Pooled estimate OR of C677T TT genotype was 1.4 (1.0–2.0). The role of C677T TT genotype was not clear in RPL. | ||||||

| Wiwanitkit [26] | 2005 | 8 | 53.1% subjects with T allele have RPL; on the other hand, 55.3% subjects without T allele have RPL. C677T might not be a useful marker for RPL. There was no association between C677T and ethnicities. | ||||||

| Ren [13] | 2006 | 26 | 2120 | 2949 | C667T was not a genetic risk factor for RPL, except in a Chinese population. | ||||

| Wu [14] | 2012 | 27 | 2427 | 3118 | C667T was associated with increased risk of RPL, except for Caucasians. | ||||

| Cao [8] | 2012 | 37 | 3559 | 5097 | Significant association between C677T and RPL in East Asian and mixed subgroup. | 8 | 1163 | 1061 | No significance between A1298C and RPL. |

| Nair [10] | 2013 | 5 | 1080 | 709 | A1298C was a genetic risk factor for RPL. | ||||

| Parveen [27] | 2013 | 12 | 1725 | 2392 | Estimated OR of C677T was 1.383 (1.045–1.830). Moderate risk of C677T in RPL. | ||||

| Rai [12] | 2014 | 17 | 2338 | 2588 | A1298C was not associated with RPL | ||||

| Chen [24] | 2015 | 16 | 1420 | 453 | Significant association between C677T and RPL in Chinese population. | 5 | 1408 | 376 | No association between A1298C and increased risk of RPL. |

| Yang [15] | 2015 | 53 | 6078 | 9441 | C677T was associated with RPL. | 16 | 2924 | 4759 | A1298C was associated with RPL. |

| Rai [28] | 2016 | 29 | 3725 | 4105 | Strong association between C677T and RPL in Asian population. | ||||

The conclusions from 11 of these reviews clearly differed. Seven reviews reached the conclusion that C677T was associated with RPL in Asian population, while two reviews held the opinion that C677T has no association with RPL. In the case of A1298C, two studies claimed this mutation as a genetic factor for RPL, while three other systematic reviews reached the opposite conclusion.

Primary study characteristics

The primary studies included in each systematic review were extracted and compared, including citation matrixes (Tables 3 and 4). With regard to C677T, six studies presented only the number of Homozygous type (TT) and total numbers of patients in RPL and control group; the other 72 provided a complete set of data for case-control studies. Of these 78 studies, 45 were conducted in Asian populations and 33 were conducted in Caucasian populations (Table 3). In term of A1298C, 31 case-control studies provided a complete data set; of these, 15 were based on Asian populations and 16 on Caucasian populations (Table 4).

Table 3.

Characteristics of primary studies included on C677T

| Author | Year of publication | Ethnicity | Case | Control | Nelen 2000 | Wiwanitkit 2005 | Ren 2006 | Wu 2012 | Cao 2013 | Parveen 2013 | Chen 2015 | Yang 2015 | Rai 2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CT | TT | CC | CT | TT | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Nelen | 1997 | Caucasian | 77 | 79 | 29 | 48 | 59 | 6 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 2 | Grandone | 1998 | Caucasian | 35 | 42 | 17 | 45 | 77 | 28 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 3 | Quere | 1998 | Caucasian | 28 | 52 | 20 | 32 | 54 | 14 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 4 | Brenner | 1999 | Asian | 54 | 8 | 14 | 86 | 9 | 11 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 5 | Holmes | 1999 | Caucasian | 102 | 57 | 14 | 31 | 30 | 6 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 6 | Kutteh | 1999 | Caucasian | 50 | 4 | 50 | 2 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| 7 | Lissak | 1999 | Caucasian | 17 | 20 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 8 | Foka | 2000 | Caucasian | 80 | 6 | 100 | 15 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| 9 | Murphy | 2000 | Caucasian | 24 | 3 | 0 | 527 | 13 | 0 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 10 | Wramsby | 2000 | Caucasian | 17 | 17 | 2 | 27 | 35 | 7 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 11 | Pihusch | 2001 | Caucasian | 41 | 47 | 14 | 55 | 61 | 12 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 12 | Carp | 2002 | Caucasian | 108 | 14 | 82 | 7 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| 13 | Unfried | 2002 | Caucasian | 64 | 46 | 23 | 46 | 24 | 4 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 14 | Dilley | 2002 | Asian | 27 | 26 | 7 | 39 | 45 | 8 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 15 | Wang | 2002 | Asian | 13 | 33 | 16 | 43 | 53 | 23 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 16 | Pauer | 2003 | Caucasian | 28 | 32 | 9 | 56 | 51 | 15 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 17 | Kumar | 2003 | Asian | 18 | 6 | 0 | 22 | 2 | 0 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 18 | Hohlagschwandtner | 2003 | Caucasian | 72 | 52 | 21 | 53 | 41 | 7 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 19 | Wang | 2004 | Asian | 49 | 78 | 20 | 43 | 34 | 5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 20 | Dossenbach-Glaninger | 2004 | Caucasian | 49 | 8 | 48 | 5 | √ | ||||||||||

| 21 | Li | 2004 | Asian | 16 | 32 | 9 | 25 | 20 | 5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 22 | Makino | 2004 | Caucasian | 56 | 55 | 14 | 29 | 32 | 15 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 23 | Wang | 2004 | Asian | 14 | 17 | 8 | 43 | 34 | 5 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 24 | Couto | 2005 | Caucasian | 29 | 47 | 12 | 53 | 26 | 9 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 25 | Gerhardt | 2005 | Caucasian | 104 | 14 | 277 | 28 | √ | ||||||||||

| 26 | Guan | 2005 | Asian | 13 | 59 | 55 | 19 | 73 | 25 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 27 | Kobashi | 2005 | Asian | 34 | 40 | 9 | 67 | 82 | 25 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 28 | Song | 2005 | Asian | 36 | 2 | 12 | 40 | 12 | 4 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 29 | Parle-McDermott | 2005 | Caucasian | 55 | 55 | 14 | 271 | 270 | 73 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 30 | Mtiraoui | 2006 | Caucasian | 92 | 47 | 61 | 156 | 30 | 14 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 31 | Dong | 2006 | Asian | 2 | 12 | 20 | 11 | 26 | 18 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 32 | Wang | 2006 | Asian | 36 | 2 | 12 | 89 | 27 | 9 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 33 | Jivraj | 2006 | Caucasian | 136 | 32 | 714 | 58 | √ | ||||||||||

| 34 | Sotiriadis | 2006 | Caucasian | 24 | 61 | 12 | 32 | 57 | 13 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 35 | Wan | 2006 | Asian | 6 | 46 | 28 | 19 | 33 | 8 | √ | ||||||||

| 36 | Ren | 2007 | Asian | 9 | 40 | 22 | 29 | 38 | 26 | √ | ||||||||

| 37 | Xu | 2007 | Asian | 21 | 48 | 43 | 32 | 50 | 18 | √ | ||||||||

| 38 | D’Uva | 2007 | Caucasian | 0 | 5 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 3 | √ | ||||||||

| 39 | Callejon | 2007 | Caucasian | 10 | 233 | 99 | 195 | 170 | 70 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 40 | Vettriselvi | 2008 | Asian | 86 | 15 | 3 | 98 | 19 | 3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 41 | Makino | 2008 | Asian | 33 | 42 | 10 | 29 | 32 | 15 | √ | ||||||||

| 42 | Toth | 2008 | Caucasian | 71 | 68 | 12 | 68 | 70 | 19 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 43 | Ma | 2008 | Asian | 12 | 32 | 16 | 19 | 34 | 7 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 44 | Cardona | 2008 | Caucasian | 38 | 43 | 12 | 93 | 83 | 30 | √ | ||||||||

| 45 | Zhong | 2008 | Asian | 72 | 50 | 16 | 116 | 43 | 3 | √ | ||||||||

| 46 | Morales-Machin | 2009 | Caucasian | 10 | 18 | 2 | 19 | 29 | 2 | √ | ||||||||

| 47 | Govindaiah | 2009 | Caucasian | 111 | 25 | 4 | 112 | 28 | 0 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 48 | Mukhopadhyay | 2009 | Asian | 75 | 6 | 3 | 78 | 2 | 0 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 49 | Ciacci | 2009 | Caucasian | 47 | 0 | 31 | 85 | 0 | 59 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 50 | Bae | 2009 | Asian | 82 | 104 | 36 | 45 | 63 | 14 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 51 | Rodriguez-Guillen | 2009 | Caucasian | 6 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 39 | 19 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 52 | Zhang | 2009 | Asian | 12 | 25 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 8 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 53 | Abu-Asab | 2010 | Asian | 145 | 151 | 33 | 182 | 177 | 43 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 54 | Kim | 2010 | Asian | 26 | 19 | 12 | 63 | 60 | 32 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 55 | Zhong | 2010 | Asian | 72 | 53 | 16 | 114 | 43 | 3 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 56 | Settin | 2011 | Caucasian | 40 | 26 | 4 | 67 | 68 | 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 57 | Nair | 2011 | Asian | 75 | 26 | 5 | 118 | 21 | 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 58 | Wang | 2011 | Asian | 18 | 82 | 59 | 28 | 78 | 21 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 59 | Jeddi-Tehrani | 2011 | Asian | 43 | 42 | 15 | 66 | 25 | 9 | √ | ||||||||

| 60 | Park | 2011 | Asian | 14 | 16 | 9 | 17 | 26 | 7 | √ | ||||||||

| 61 | Ozdemir | 2011 | Asian | 231 | 239 | 73 | 76 | 30 | 0 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 62 | Parveen | 2012 | Asian | 110 | 70 | 20 | 196 | 90 | 14 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 63 | Han | 2012 | Asian | 10 | 35 | 26 | 25 | 15 | 18 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 64 | Dissanayke | 2012 | Asian | 158 | 39 | 3 | 142 | 27 | 2 | √ | ||||||||

| 65 | Torabi | 2012 | Asian | 43 | 42 | 15 | 66 | 25 | 9 | √ | ||||||||

| 66 | Zonouzi | 2012 | Asian | 53 | 30 | 9 | 27 | 22 | 1 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 67 | Creus | 2012 | Caucasian | 23 | 26 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 4 | √ | ||||||||

| 68 | Puri | 2012 | Asian | 86 | 16 | 5 | 263 | 69 | 11 | √ | ||||||||

| 69 | Yin | 2012 | Asian | 13 | 25 | 15 | 33 | 18 | 12 | √ | ||||||||

| 70 | Kaur | 2013 | Asian | 86 | 16 | 5 | 463 | 109 | 21 | √ | ||||||||

| 71 | Cao | 2013 | Asian | 29 | 43 | 10 | 53 | 83 | 30 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 72 | Chen | 2013 | Asian | 30 | 20 | 9 | 50 | 36 | 1 | √ | ||||||||

| 73 | Hu | 2014 | Asian | 29 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 1 | √ | ||||||||

| 74 | Luo | 2014 | Asian | 40 | 70 | 15 | 60 | 65 | 10 | √ | ||||||||

| 75 | Yousefian | 2014 | Asian | 96 | 90 | 18 | 63 | 43 | 10 | √ | √ | |||||||

| 76 | Farahmand | 2015 | Asian | 180 | 114 | 36 | 230 | 85 | 35 | √ | ||||||||

| 77 | Vanill | 2015 | Asian | 13 | 2 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 0 | √ | ||||||||

| 78 | Hubacek | 2015 | Caucasian | 208 | 214 | 42 | 1068 | 1116 | 302 | √ | ||||||||

Table 4.

Characteristics of primary studies included on A1298C

| Author | Year of publication | Ethnicity | Case | Control | Nair 2012 | Cao 2013 | Rai 2014 | Chen 2015 | Yang 2016 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AC | CC | AA | AC | CC | |||||||||

| 1 | Hohlagschwandtner | 2003 | Caucasian | 63 | 67 | 15 | 35 | 50 | 16 | √ | √ | |||

| 2 | Li | 2004 | Asian | 33 | 21 | 3 | 29 | 18 | 3 | √ | ||||

| 4 | Mtiraoui | 2006 | Caucasian | 108 | 65 | 27 | 130 | 62 | 8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 5 | Sotiriadis | 2006 | Caucasian | 44 | 37 | 7 | 45 | 39 | 6 | √ | √ | |||

| 6 | Wang | 2006 | Asian | 103 | 35 | 10 | 60 | 20 | 2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 8 | Callejon | 2007 | Caucasian | 209 | 89 | 44 | 248 | 149 | 37 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 9 | Ren | 2007 | Asian | 0 | 17 | 54 | 1 | 6 | 86 | √ | ||||

| 10 | Bae | 2009 | Asian | 144 | 68 | 9 | 75 | 43 | 4 | √ | √ | |||

| 11 | Ciacci | 2009 | Caucasian | 22 | 0 | 56 | 52 | 0 | 92 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 12 | Rodriguez-Guillen | 2009 | Caucasian | 18 | 5 | 0 | 60 | 14 | 0 | √ | ||||

| 13 | Kim | 2011 | Asian | 34 | 21 | 2 | 113 | 38 | 4 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 14 | Jeddi-Tehrani | 2011 | Asian | 69 | 27 | 4 | 94 | 6 | 0 | √ | ||||

| 15 | Klai | 2011 | Asian | 47 | 14 | 2 | 93 | 7 | 0 | √ | ||||

| 16 | Ozdemir | 2011 | Caucasian | 201 | 257 | 85 | 71 | 35 | 0 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 17 | Settin | 2011 | Caucasian | 15 | 49 | 6 | 36 | 97 | 3 | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 18 | Dissanayke | 2012 | Asian | 74 | 78 | 43 | 72 | 79 | 46 | √ | ||||

| 19 | Nair | 2012 | Asian | 48 | 68 | 13 | 116 | 80 | 6 | √ | √ | |||

| 20 | Torabi | 2012 | Asian | 69 | 27 | 4 | 94 | 6 | 66 | √ | ||||

| 21 | Zonouzi | 2012 | Caucasian | 35 | 46 | 8 | 13 | 34 | 3 | √ | √ | |||

| 22 | Chen | 2013 | Asian | 24 | 29 | 6 | 38 | 44 | 5 | √ | ||||

| 23 | Herodez | 2013 | Caucasian | 36 | 48 | 16 | 43 | 47 | 18 | √ | ||||

| 24 | Parveen | 2013 | Caucasian | 88 | 92 | 20 | 157 | 127 | 16 | √ | √ | |||

| 25 | Cao | 2014 | Asian | 49 | 31 | 2 | 132 | 31 | 3 | √ | ||||

| 26 | Hefler | 2014 | Caucasian | 49 | 38 | 7 | 43 | 40 | 11 | √ | ||||

| 27 | Hu | 2014 | Asian | 33 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 1 | √ | ||||

| 28 | Lino | 2014 | Caucasian | 71 | 32 | 9 | 52 | 43 | 3 | √ | ||||

| 29 | Luo | 2014 | Asian | 82 | 40 | 3 | 78 | 54 | 3 | √ | ||||

| 30 | Yousefian | 2014 | Asian | 98 | 81 | 25 | 68 | 39 | 9 | √ | ||||

| 31 | Hubacek | 2015 | Caucasian | 209 | 212 | 43 | 1145 | 1066 | 275 | √ | ||||

The citation matrix showed the differences of selection for each systematic review, along with a meta-analysis which identified similarities and controversies in the published conclusions (Tables 3 and 4).

A summarized meta-analysis combining primary studies reported in 11 systematic reviews and meta-analyses (overall analysis and sub-group analyses by ethnicity)

According to the citation matrixes and the primary studies included in 11 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we re-calculated the OR and 95%CI of different genotype models (Table 5). Due to high heterogeneity, the OR and 95%CI were removed in a random-effect model. The OR and 95%CI of C677T in Recessive model were not heavily influenced by the 6 primary studies in which only the number of TT genotypes and the total number of cases and controls were provided.

Table 5.

Re-meta-analysis of primary studies on MTHFR polymorphisms

| Allele | Dominant | Recessive | Recessive (6 included) | Homozygous | Heterozygous | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR, 95%CI | I 2 | OR, 95%CI | I 2 | OR, 95%CI | I 2 | OR, 95%CI | I 2 | OR, 95%CI | I 2 | OR, 95%CI | I 2 | |

| C677T | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 1.54 (1.38, 1.72) | 62.30% | 1.61 (1.39, 1.86) | 57.90% | 1.85 (1.53, 2.25) | 46.70% | 1.85 (1.53, 2.25) | 46.70% | 2.32 (1.84, 2.92) | 53.20% | 1.44 (1.24, 1.67) | 53.80% |

| Caucasian | 1.28 (1.03, 1.58) | 87.20% | 1.33 (1.01, 1.76) | 84.70% | 1.42 (1.05, 1.91) | 70.60% | 1.43 (1.10, 1.86) | 68.80% | 1.66 (1.07, 2.58) | 83.60% | 1.27 (0.96, 1.67) | 81.90% |

| Total | 1.43 (1.29, 1.60) | 78.50% | 1.50 (1.30, 1.73) | 75.20% | 1.68 (1.42, 1.99) | 60.30% | 1.66 (1.42, 1.95) | 59.60% | 2.08 (1.66, 2.61) | 72.90% | 1.37 (1.18, 1.57) | 70.80% |

| A1298C | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 1.25 (0.90, 1.75) | 85.50% | 1.44 (1.05, 1.98) | 73.70% | 1.15 (0.62, 2.14) | 73% | 1.47 (0.79, 2.75) | 67.40% | 1.62 (1.17, 2.25) | 71.50% | ||

| Caucasian | 1.16 (0.95, 1.41) | 76.60% | 1.11 (0.88, 1.41) | 72% | 1.44 (1.00, 2.08) | 63.50% | 1.43 (0.97, 2.12) | 65.70% | 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) | 65.30% | ||

| Total | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) | 81.60% | 1.25 (1.03, 1.50) | 72.60% | 1.29 (0.93, 2.12) | 68% | 1.43 (1.03, 1.98) | 64.20% | 1.25 (1.03, 1.53) | 70.60% | ||

In term of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and RPL, there were 78 primary studies, including 8907 cases and 13,636 controls. The OR and 95%CI of C677T in Allele model were 1.54 (1.38, 1.72) in Asian population, 1.28 (1.03, 1.58) in Caucasian population, and 1.43 (1.29, 1.60) overall. The most significant genotype model for C677T was Homozygous model, in which OR and 95%CI were 2.32 (1.84, 2.92) in Asian population compared with 1.66 (1.07, 2.58) in Caucasian population and 2.08 (1.66, 2.61) overall.

In term of A1298C polymorphism and RPL, 31 primary studies were analyzed, including 4211 cases and 6208 controls. The OR and 95%CI of A1298C in Allele model were 1.25 (0.90, 1.75) in Asian group, 1.16 (0.95, 1.41) in Caucasian group, and 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) overall. Analysis showed no association between A1298C polymorphism and RPL, except that the OR and 95%CI of A1298C in Heterozygous model were 1.62 (1.17, 2.25) in Asians, 1.02 (0.81, 1.28) in Caucasians, and 1.25 (1.03, 1.53) overall, which might indicate moderate RPL risk for the heterozygous genotype AC of MTHFR.

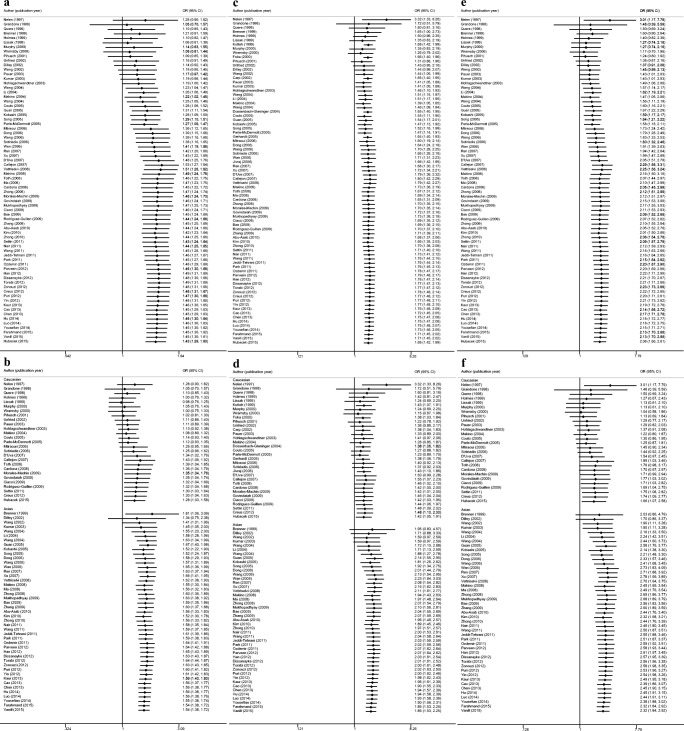

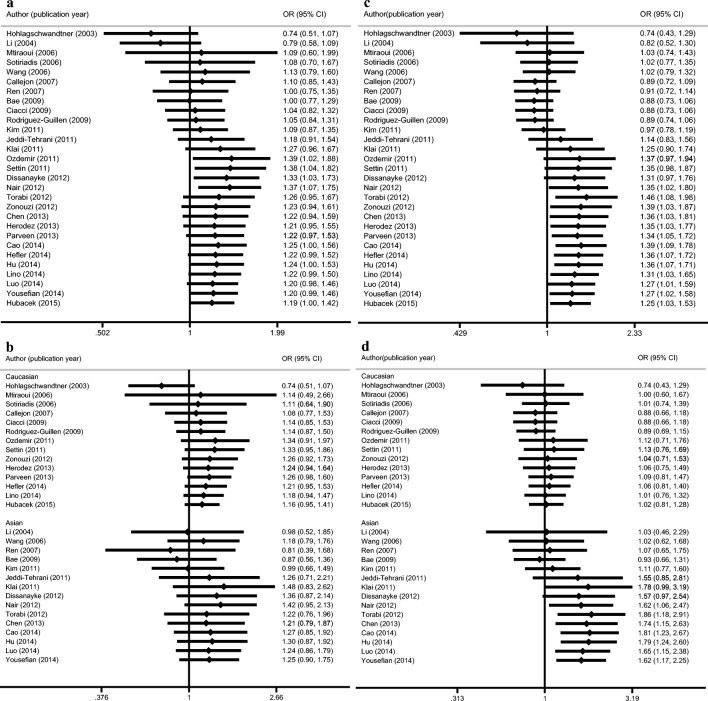

Cumulative meta-analyses of MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL (overall analysis and sub-group analyses by ethnicity)

Cumulative studies were performed on MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL risk sorted by publication year. Differences of tendency across ethnicities were also evident in subgroups.

Trends of C677T and RPL risk in Allele model are shown in Fig. 2 a and b. The first statistical change appeared in the 16th study in 2003, which remained stable in the next 56 primary studies over 12 years (Fig. 2a). Compared with wagging trends for Caucasians in Allele model, C677T mutation of Asians in the Allele model remained unchanged except for the first 3 studies (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative meta-analysis of a C677T in Allele model, b C677T in Allele model of different ethnicities, c C677T in Recessive model, d C677T in Recessive model of different ethnicities, e C677T in Homogeneous model, f C677T in Homogeneous model of different ethnicities

With 6 primary studies only providing TT and total number, the first statistical association of C677T in Recessive model was achieved in the 14th study in 2002 (Fig. 2c). In the recessive model, C677T showed a similar tendency to Allele model for Asian population (Fig. 2d). Following the publication of 4 studies showing uncertainty, the association did not change in Asian population but remained uncertain in 33 primary studies involving Caucasians.

In Homozygous model, C677T mutation in Asian group did not change after the 3rd study and the width of the 95%CI became more narrow and more stable (Fig. 2e, f).

In all three models, the OR and 95%CI changed in a swinging trend across 31 primary studies (Fig. 3a, b). Heterozygous genotype showed only a moderate risk between A1298C and RPL (Fig. 3c, d). However, a statistical change appeared only in the last 6 studies, published between 2012 and 2014.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative meta-analysis of a A1298C in Allele model, b A1298C in Allele model of different ethnicities, c A1298C in Heterogeneous model, d A1298C in Heterogeneous model of different ethnicities

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Begg’s test and Egger’s test were performed for checking the publication bias of the primary case-control studies (Table 6). On C677T of MTHFR polymorphism, publication bias appeared in Dominant model of overall analysis and Caucasian subgroup, Homogeneous model of overall analysis and Asian subgroup, and Recessive model of overall analysis and Asian subgroup. Other primary studies on C677T did not have publication bias. On A1298C of MTHFR polymorphism, publication bias did not exist.

Table 6.

Begg’s test and Egger’s test on publication bias of primary case-control studies

| Begg’s test | ||||||||||||

| Allele | Dominant | Recessive | Recessive (6 included) | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous | |||||||

| z | p | z | p | z | p | z | p | z | p | z | p | |

| C677T | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 1.12 | 0.265 | 1.66 | 0.096 | 2.82 | 0.005* | 2.82 | 0.005* | 3.02 | 0.002* | 0.39 | 0.696 |

| Caucasian | 1.13 | 0.26 | 2.17 | 0.03* | 1.63 | 0.103 | 1.31 | 0.189 | 1.81 | 0.071 | 1.9 | 0.058 |

| Total | 1.91 | 0.057 | 2.38 | 0.017* | 3.17 | 0.002* | 2.86 | 0.004* | 3.4 | 0.001* | 1.34 | 0.182 |

| A1298C | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 0.79 | 0.428 | 0.89 | 0.373 | 0.99 | 0.322 | 0.79 | 0.428 | 1.63 | 0.102 | ||

| Caucasian | 0.11 | 0.913 | 0 | 1 | 1.53 | 0.127 | 1.4 | 0.161 | 0.55 | 0.583 | ||

| Total | 0.54 | 0.586 | 1.03 | 0.302 | 1.36 | 0.173 | 1.36 | 0.173 | 1.34 | 0.179 | ||

| Egger’s test | ||||||||||||

| Allele | Dominant | Recessive | Recessive (6 included) | Homogeneous | Heterogeneous | |||||||

| t | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | t | p | |

| C677T | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 2.02 | 0.05 | 1.81 | 0.078 | 3.16 | 0.003* | 3.16 | 0.003* | 3.99 | 0.001* | 0.32 | 0.754 |

| Caucasian | 0.35 | 0.73 | 1.35 | 0.189 | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 1.2 | 0.24 | 1.14 | 0.264 |

| Total | 1.74 | 0.087 | 2.53 | 0.014* | 3.09 | 0.003* | 2.58 | 0.012* | 3.48 | 0.001* | 1.42 | 0.161 |

| A1298C | ||||||||||||

| Asian | 0.92 | 0.374 | 1.48 | 0.161 | 0.92 | 0.374 | 1.14 | 0.273 | 2.04 | 0.062 | ||

| Caucasian | 0.54 | 0.596 | 0 | 0.999 | 2.09 | 0.061 | 1.74 | 0.11 | −0.43 | 0.678 | ||

| Total | 0.98 | 0.337 | 1.19 | 0.243 | 1.48 | 0.15 | 1.82 | 0.081 | 1.58 | 0.126 | ||

*In Begg’s test or Egger’s test, p value < 0.05

We conducted sensitivity study to test the origin of heterogeneity. The results showed no individual case-control study had marked effect on the meta-analysis of primary studies of C677T or A1298C.

Quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Table 6 and Table 7 show the quality assessments of 11 systematic reviews and meta-analyses executed with AMSTAR and OQAQ scales. The AMSTAR assessment showed one review of high methodology quality (≥ 8), 2 of low quality (≤ 3), and 8 of moderate quality with scores ranging from 5 to7 (Table 7). The OQAQ scale showed similar results for the quality of 11 systematic reviews, of which there were 2 of low quality (≤ 3) and 9 of moderate quality with scores between 5 and 7 (Table 8).

Table 7.

AMSTAR scores of 11 systematic reviews included

| Author | Year | 1. A priori design | 2. Duplicate selection | 3. Literature search | 4. Status of publication | 5. List of studies | 6. Characteristics of included | 7. Quality of included | 8. Scientific quality used | 9. Appropriate methods | 10. Likelihood of bias | 11. Conflict of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelen | 2000 | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | +/− |

| Wiwanitkit | 2005 | + | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | +/− |

| Ren | 2006 | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Wu | 2012 | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Cao | 2012 | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Nair | 2013 | + | +/− | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Parveen | 2013 | + | +/− | – | + | – | – | – | – | +/− | + | +/− |

| Rai | 2014 | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Chen | 2015 | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Yang | 2015 | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

| Rai | 2016 | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | +/− |

+: yes; −: no; +/–: partially answered or unclear

Table 8.

OQAQ scores of 11 systematic reviews included

| Author | Year | 1. Search methods stated | 2. Search comprehensive | 3. Inclusion criteria reported | 4. Selection bias avoided | 5. Validity criteria reported | 6. Validity assessed appropriately | 7. Combining methods reported | 8. Finding combined appropriately | 9. Conclusions supported by the data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelen | 2000 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Wiwanitkit | 2005 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Ren | 2006 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Wu | 2012 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Cao | 2012 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Nair | 2013 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Parveen | 2013 | – | +/− | – | +/− | – | – | +/− | + | + |

| Rai | 2014 | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + |

| Chen | 2015 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Yang | 2015 | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + |

| Rai | 2016 | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + |

+: yes; −: no; +/–: partially answered or unclear

Discussion

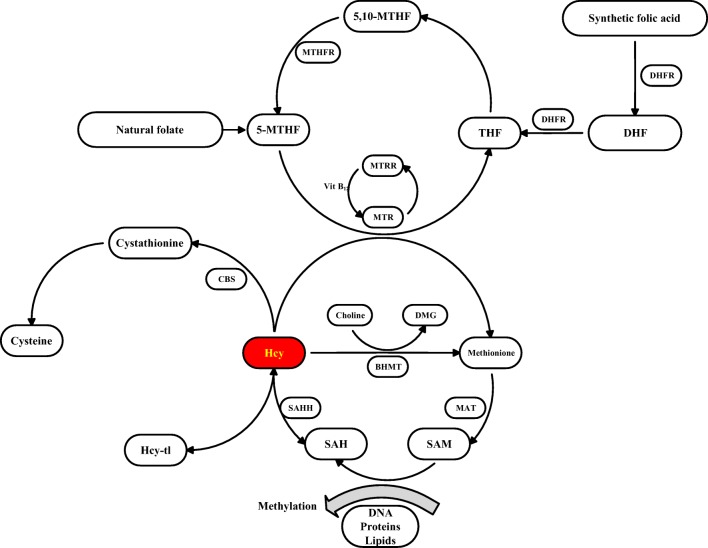

MTHFR plays a key role in catalyzing synthetic folic acid to 5-MTHF, also absorbed as natural folate from food [29], which participates in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine (Fig. 4). The transformation of homocysteine causes a reduction in the level of homocysteine in the plasma and promotes the methylation of substances such as DNA, protein, and lipids involving S-adenosylmethionine to S-adenosylhomocysteine [30].

Fig. 4.

Mechanism of MTHFR in recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL)

DNA methylation plays a crucial role in trophoblast development, affecting imprinted or non-imprinted genes after global demethylation on morula stage (third day postconception) [31]. Epigenetic modification in the placenta leads to intrauterine growth restriction, through methylation on gene promotors [32]. Recent research has reported such placental epigenetics are regulated with imprinted genes such as IGF2/H19, PEG10 on paternal chromosome and PHLDA2, CDKN1C on maternal chromosome [33].

MTHFR polymorphisms induce structural changes of MTHFR protein. For instance, C677T causes alanine to be substituted for valine and A1298C causes glutamate to be substituted for alanine. The thermolability and reduction of enzyme activity lead to elevated concentration of homocysteine [34]. Hcy concentration is also controlled through folate-independent pathways including CBS (cystathionine β-synthase) and BHMT (betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase) in liver and kidney [35]. The compensatory regulations fail to remove Hcy accumulated in pregnant women with MTHFR deficiency, as the peak demand cannot be reached [36, 37]. High level of homocysteine leads to RPL with pathway of Hcy toxicity such as homocysteinylation, oxidative stress induction, and biotoxicity itself [38].

While numerous primary studies and systematic reviews have investigated the correlation between MTHFR polymorphisms and RPL, the outcome of this research remains unclear, and even controversial when comparing across different authors [39]. When comparing OR and 95%CI in Allele model conducted in this current study with the results from previous systematic reviews, it was evident that the C677T polymorphism could represent a risk marker for RPL, especially in Asian population. Results from Homozygous and Recessive models further indicated that TT genotype could represent a significant risk marker for RPL. Despite the moderate level of risk shown in Heterozygous model, there may be no relationship between A1298C and RPL.

Paternal MTHFR gene influence may have contributed to discrepancies in A1298C, resulting aneuploidy in embryo [40]. Despite chromosome abnormality, paternal MTHFR polymorphisms could also lead to destruction in sperm nucleus DNA as well [41]. Cornet [42] reported that, in population included (18 homozygous, 77 heterozygous, 1405 control) with SDI (sperm nucleus decondensation index) above 20%, the homozygote group presented with 67% comparing to 23% in the control group and 30% in heterozygote group. The selection of primary studies from systematic reviews and meta-analyses most likely contributed to the discrepancies evident in the published conclusions from different authors; this was evident in the selection matrix.

AMSTAR and OQAQ scales showed moderate quality overall in 11 systematic reviews and low quality in 2 systematic reviews. A common deficiency of the 11 systematic reviews with moderate quality was the lack of validity criteria or the nature of the validity criteria used, which is commonly evaluated with the NOS (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale) [43] for case-control studies. The lack of qualification for primary studies may therefore have contributed to the heterogeneity and controversy evident in the published conclusions.

The tendency of stability was demonstrated by the cumulative meta-analysis of MTHFR polymorphisms in RPL. The meta-analyses relating to C677T, and based upon early primary studies, did not show any correlation with RPL; this was in accordance with the views of previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses which were published prior to 2005. However, as the number of primary studies increased, the OR and 95%CI of the C677T polymorphism changed to positive and became stable over the next few years in Allele, Recessive, and Homozygous models. The trend for the A1298C polymorphism in Allele model remains unclear; despite the positive change appearing in 2011, the data was mainly based on recent primary studies in Asian population.

The mild tendency of A1298C in Heterozygous model might attribute to composite C677T and A1298C. Xu [44] has found that compound 677/1298 heterozygous genotype is a risk factor in RPL. In 218 in RPL group and 264 in control group, no composite homozygote genotype appeared; however, patients with composite heterozygote (677CT-1298AC) presented with higher risk compared with the control group (OR, 95%CI 4.996, 1.65–15.129). Paternal effect may also have contributed to the compound MTHFR genotype in embryo [45].

There are some limitations in this present study which need to be considered. First of all, heterogeneity was observed in each genotype model for C677T and A1298C polymorphisms; thus, results based on primary studies should be interpreted with caution. Second, the NOS is not used to investigate the quality of primary studies and this might be the underlying factor responsible for the overall high heterogeneity. Finally, there are some factors which could have influenced our results but were not considered, such as age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, and environmental factors [46].

In conclusion, MTHFR C677T polymorphism appears to represent a risk marker for RPL, especially in Asian population. The TT genotype of C677T appears more significant than the other genotypes, particularly in term of RPL. However, there is no significant correlation between A1298C and RPL, except for in Heterozygous model, which indicates moderate risk. We believe that differences in the selection of primary studies lead to the controversial and inconsistent conclusions made by different authors in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses considered in our present study. More comprehensive and rigorous systematic reviews and meta-analyses should now be performed, which incorporate quality-controlled primary case-control studies. Future investigations also need to consider different ethnicities, gene-gene interaction, and gene-environment interaction in order to fully investigate the influence of MTHFR polymorphisms on RPL.

Funding information

This research is supported by Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University (FCYY201819). The authors are highly grateful to the support of Department of Pharmacy of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chenghong Yin, Phone: +86-010-6313-8748, Email: modscn@126.com.

Xin Feng, Phone: +86-010-5227-7244, Email: fengxin1115@126.com.

References

- 1.Page JM, Silver RM. Genetic causes of recurrent pregnancy loss. J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(3):498–508. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pritchard AM, Hendrix PW, Paidas MJ. Hereditary thrombophilia and recurrent pregnancy loss. J Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(3):487–497. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelen WL, Blom HJ, Steegers EA, den Heijer M, Thomas CM, Eskes TK. Homocysteine and folate levels as risk factors for recurrent early pregnancy loss. J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(4):519–524. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moll S, Varga EA. Homocysteine and MTHFR mutations. J Circulation. 2015;132(1):e6–e9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg (London, England) 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jr Faggion CM. Critical appraisal of AMSTAR: challenges, limitations, and potential solutions from the perspective of an assessor. J BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:63. doi:10.1186/s12874-015-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Delaney A, Bagshaw SM, Ferland A, Laupland K, Manns B, Doig C. The quality of reports of critical care meta-analyses in the Cochrane database of systematic reviews: an independent appraisal. J Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):589–594. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253394.15628.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao Y, Xu J, Zhang Z, Huang X, Zhang A, Wang J, et al. Association study between methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms and unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Gene. 2013;514(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Yang X, Lu M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphisms and recurrent pregnancy loss in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(2):283–290. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair RR, Khanna A, Singh R, Singh K. Association of maternal and fetal MTHFR A1298C polymorphism with the risk of pregnancy loss: a study of an Indian population and a meta-analysis. J Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1311–18e4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelen WLDM, Blom HJ, Steegers EAP, Den Heijer M, Eskes TKAB. Hyperhomocysteinemia and recurrent early pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Fert Steril. 2000;74(6):1196–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)01595-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rai V. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene A1298C polymorphism and susceptibility to recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Cell Mol Biol. 2014;60(2):27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren A, Wang J. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and the risk of unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1716–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu X, Zhao L, Zhu H, He D, Tang W, Luo Y. Association between the MTHFR C677T polymorphism and recurrent pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. J Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(7):806–811. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Luo Y, Yuan J, Tang Y, Xiong L, Xu MM, et al. Association between maternal, fetal and paternal MTHFR gene C677T and A1298C polymorphisms and risk of recurrent pregnancy loss: a comprehensive evaluation. J Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(6):1197–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3944-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simcox LE, Ormesher L, Tower C, Greer IA. Thrombophilia and pregnancy complications. J Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(12):28418–28428. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clement A, Cornet D, Cohen M, Jacquesson L, Amar E, Clement P, et al. Impact of MTHFR iso form C667T on fertility through sperm DNA fragmentation index (DFI) and sperm nucleus decondensation (SDI) J Hum Reprod. 2017;32:i149–ii50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bogdanova N, Markoff A. Hereditary thrombophilic risk factors for recurrent pregnancy loss. J Community Genet. 2010;1(2):47–53. doi: 10.1007/s12687-010-0011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen H. Inherited thrombophilia and pregnancy loss-epidemiology. J Thromb Res. 2005;115(SUPPL):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moll S. Thrombophilias - practical implications and testing caveats. J J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-5570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rambaldi MP, Mecacci F, Paidas MJ. Evaluation and management of recurrent pregnancy loss. J Placenta. 2011;32:5278. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray JG, Laskin CA. Folic acid and homocyst(e)ine metabolic defects and the risk of placental abruption, pre-eclampsia and spontaneous pregnancy loss: a systematic review. J Placenta. 1999;20(7):519–529. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada H, Sata F, Saijo Y, Kishi R, Minakami H. Genetic factors in fetal growth restriction and miscarriage. J Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31(3):334–345. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-872441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Chen L, Zhu LH, Zhang ST, Wu YL. Association of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T polymorphism with preterm delivery and placental abruption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(2):157–165. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Nisio M, Rutjes AWS, Ferrante N, Tiboni GM, Cuccurullo F, Porreca E. Thrombophilia and outcomes of assisted reproduction technologies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Blood. 2011;118(10):2670–2678. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiwanitkit V. Roles of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism in repeated pregnancy loss. J Clin Appl Thromb/Hemost. 2005;11(3):343–345. doi: 10.1177/107602960501100315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parveen F, Tuteja M, Agrawal S. Polymorphisms in MTHFR, MTHFD, and PAI-1 and recurrent miscarriage among north Indian women. J Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288(5):1171–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2877-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rai V. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and recurrent pregnancy loss risk in Asian population: a meta-analysis. J Indian J Clin Biochem. 2016;31(4):402–413. doi: 10.1007/s12291-016-0554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naderi N, House JD. Recent developments in folate nutrition. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2018;83:195–213. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2017.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quere I, Mercier E, Bellet H, Janbon C, Mares P, Gris JC. Vitamin supplementation and pregnancy outcome in women with recurrent early pregnancy loss and hyperhomocysteinemia. J Fertil Steril. 2001;75(4):823–825. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)01678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serman L, Dodig D. Impact of DNA methylation on trophoblast function. Clin Epigenetics. 2011;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branco MR, King M, Perez-Garcia V, Bogutz AB, Caley M, Fineberg E, et al. Maternal DNA methylation regulates early trophoblast development. Dev Cell. 2016;36(2):152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koukoura O, Sifakis S, Spandidos DA. DNA methylation in the human placenta and fetal growth (review) Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(4):883–889. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozdemir O, Yenicesu GI, Silan F, Koksal B, Atik S, Ozen F, et al. Recurrent pregnancy loss and its relation to combined parental thrombophilic gene mutations. J Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(4):279–286. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar A, Palfrey HA, Pathak R, Kadowitz PJ, Gettys TW, Murthy SN. The metabolism and significance of homocysteine in nutrition and health. Nutr Metab. 2017;14:78. doi: 10.1186/s12986-017-0233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Imbard A, Benoist JF, Esse R, Gupta S, Lebon S, de Vriese AS, et al. High homocysteine induces betaine depletion. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(4). 10.1042/bsr20150094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hiraoka M, Kagawa Y. Genetic polymorphisms and folate status. Congenit Anom. 2017;57(5):142–149. doi: 10.1111/cga.12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skovierova H, Vidomanova E, Mahmood S, Sopkova J, Drgova A, Cervenova T, et al. The molecular and cellular effect of homocysteine metabolism imbalance on human health. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10). 10.3390/ijms17101733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Dutra CG, Fraga LR, Nacul AP, Passos EP, Goncalves RO, Nunes OL, et al. Lack of association between thrombophilic gene variants and recurrent pregnancy loss. J Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014;17(2):99–105. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.882022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enciso M, Sarasa J, Xanthopoulou L, Bristow S, Bowles M, Fragouli E, et al. Polymorphisms in the MTHFR gene influence embryo viability and the incidence of aneuploidy. Hum Genet. 2016;135(5):555–568. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Servy EJ, Jacquesson-Fournols L, Cohen M, Menezo YJR. MTHFR isoform carriers. 5-MTHF (5-methyl tetrahydrofolate) vs folic acid: a key to pregnancy outcome: a case series. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018. 10.1007/s10815-018-1225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Cornet D, Cohen M, Clement A, Amar E, Fournols L, Clement P, et al. Association between the MTHFR-C677T isoform and structure of sperm DNA. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(10):1283–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. J BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y, Ban Y, Ran L, Yu Y, Zhai S, Sun Z, et al. Relationship between unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms. Fertil Steril. 2019. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Govindaiah V, Naushad SM, Prabhakara K, Krishna PC, Radha Rama Devi A. Association of parental hyperhomocysteinemia and C677T methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphism with recurrent pregnancy loss. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(4–5):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. J Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1103–11. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed]