Abstract

Thiopeptides are natural antibiotics that are fashioned from short peptides by multiple layers of post-translational modification. Their biosynthesis, in particular the pyridine synthases that form the macrocyclic antibiotic core, has attracted intensive research but is complicated by the challenges of reconstituting multiple pathway enzymes. By combining select RiPP enzymes with cell free expression and Flexizyme-based codon reprogramming, we have developed a benchtop biosynthesis of thiopeptide scaffolds. This strategy side-steps several challenges related to the investigation of thiopeptide enzymes and allows access to analytical quantities of new thiopeptide analogs. We further demonstrate that this strategy can be used to validate the activity of new pyridine synthases without the need to reconstitute the cognate prior pathway enzymes.

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) are a growing family of peptide-derived natural products that exhibit natural combinatorial biosynthetic logic.1 RiPP biosyntheses initiate from a gene-encoded precursor peptide, which contains a core region that undergoes enzymatic post-translational modification, and a leader region, which is typically responsible for recruiting and coordinating these enzymes through specific recognition sequences (RSs). These RSs have affinity for select domains of RiPP biosynthetic enzymes, increasing substrate local concentration to the otherwise promiscuous enzyme active sites, and allowing the modification of diverse cores.2,3 Natural pathways exhibit leader peptides with multiple RSs and recruit whole suites of post-translational modifying enzymes to convert precursor peptides into mature natural products. The combination of RS-programmable recruitment and promiscuous enzymes inspires recent efforts at repurposing this strategy to scaffold new-to-nature hybrid biosynthetic pathways. 4–8

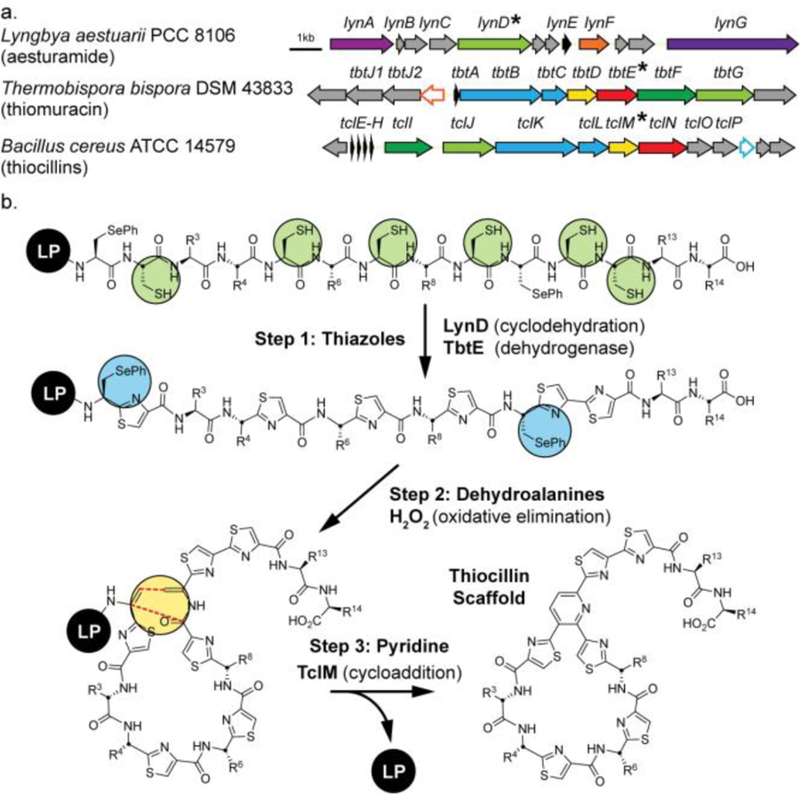

Thiopeptides are one of the most extensive natural examples of this combinatorial, RS-directed biosynthesis,9,10 and the three class-defining transformations include the formation of azoles, dehydroamino acids, and pyridines from serine and cysteine residues (Figure 1a). Many of these enzymes are remarkably promiscuous and thiopeptide pathways have proven capable of generating many variants.11,12 For example, hundreds of mutants of thiocillin, GE37468, and thiostrepton have been generated by gene replacement strategies.13–15 However, competition between the pathway enzymes for functional groups on non-native substrates can give rise to complex mixtures of products and slower processing of mutant substrates or host toxicity can restrict production of potential compounds. The in vitro reconstitution of whole thiopeptide biosynthetic pathways, which has recently been achieved for thiomuracin, can circumvent some of these problems, but relies on access to soluble, well-behaved proteins.16,17 This can be especially challenging for the tRNA dependent Lantibiotic-type dehydratases. Additionally, this strategy still does not overcome enzyme competition. Alternative strategies, such as a chemoenzymatic approach, could allow rapid access to novel structural variants and ease characterization of new thiopeptides and thiopeptide-associated enzymes.18

Figure 1.

Flexizyme-enabled benchtop biosynthesis of thiopeptide scaffolds. a) Biosynthetic gene clusters of thiocillins, thiomuracin GZ, and aesturamide. Genes for key enzymes used in this work are highlighted with asterisks. b) Proposed hybrid route to the thiocillin core.

We envisioned that carefully chosen RiPP enzymes might be combined with orthogonal chemical handles to create a flexible in vitro platform for the benchtop preparation of thiopeptides (Figure 1b).19,20 More specifically, in vitro transcription-translation could be used to express designer hybrid leader peptide substrates displaying RSs for the cyclodehydratase LynD from aesturamide biosynthesis and pyridine synthase, TclM from thiocillin biosynthesis. Both enzymes have well-defined RS motifs and broad substrate promiscuity. Additionally, LynD exhibits excellent selectivity for Cys conversion to thiazolines while ignoring Ser/Thr residues.21,22 Alternatively, if oxazoles are of interest, then PatD, which acts on Ser/Thr/Cys, could be used in place of LynD. 20 Oxidation of thiazolines to thiazoles might be effected by the azoline-oxidase, TbtE from thiomuracin biosynthesis, which acts in a leader peptide independent manner.16 In place of Lantibiotic dehydratases, we would use robust Flexizyme technology to introduce the unnatural amino acid Se-phenylselenocysteine (SecPh), which undergoes oxidative elimination with H2O2 to generate dehydroalanines (Dhas) for the pyridine-forming cycloaddition.23–25 Flexizymes are aptamers developed to condense a wide array of amino acid esters with tRNAs of choice (see Supplementary Fig. 6), allowing codon reprograming in in vitro transcription/translation systems.26,27 In total, this would cut the number of enzymes or proteins necessary to prepare a thiopeptide in vitro from, six, in case of thiocillin (TbtIJKLMN), to three (LynD, TbtE, and TclM, Figure 1). Although quantities of peptide made by in vitro transcription-translation and Flexizyme reprogramming are small relative to other technologies, such as amber codon suppression/in cell expression or solid phase peptide synthesis, the approach is rapid (~2 hr.), robust, and flexible for peptides of this size and complexity. Thus, we anticipate that this strategy might ultimately enable rapid characterization of new pyridine synthases and associated enzymes and aid elucidation of new thiopeptides.

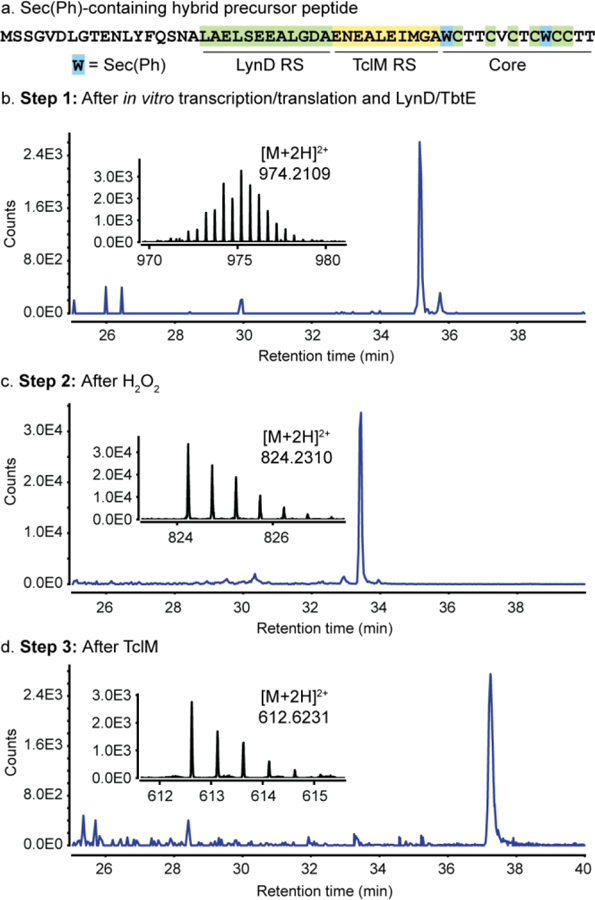

In order to validate this strategy, we first had to confirm that existing Flexizymes could incorporate SecPh into in vitro translated peptides and that LynD and TbtE could accommodate SecPh at cysteine-adjacent positions. We confirmed that the dinitrobenzyl (Dnb) ester-specific Flexizyme dFx could ligate the Dnb ester of SecPh by means of an in vitro microhelix assay (see Supplementary Figure S2).25 Hybrid substrates were prepared by codon reprogramming the tryptophan codon – although Flexizyme allows a number of codons to be reprogrammed – due to the scarcity of Trp residues in thiopeptides, using the AsnE2 tRNA body.28 The loaded AsnE2trp-tRNA was used to incorporate SecPh at positions Ser1 and Ser10 of the thiocillin core. For ease, initial DNA templates were prepared by cloning into plasmid pMCSG7 which necessarily incorporated an N-terminal sequence tag leading to the design of our test substrate (Figure 2a), and transcription-translation reactions were prepared on 2.5 µL analytical scale using NEB PURExpress. 26,27 In the event, LynD was able to convert all six cysteines in several test substrates into thiazolines, which were further processed to thiazoles by TbtE as confirmed by high resolution liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (HR LC/MS) (Figure 2b and Supporting Information). Subsequent treatment with 1 M H2O2 efficiently converted both SecPh residues to Dhas (Figure 2c). In the last proof-of-concept step, the excess H2O2 could be quenched by addition of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) and TclM added in situ provided complete conversion of the linear substrate into a cyclic thiopeptide (Figure 2d), confirming that TclM is compatible with this designed leader strategy.

Figure 2.

Flexizyme-enabled benchtop biosynthesis of a thiocillin scaffold. a) Sequence of the designer precursor peptide, including a pMCSG7-derived sequence, the LynD RS and TclM RS. The Trp-codon was reprogrammed to incorporate SecPh. EICs for SecPh and hexathiazole precursor peptide after LynD/TbtE treatment (b), hexathiazole and Dha-containing product after oxidative elimination (c), and fully cyclized thiocillin core (d).

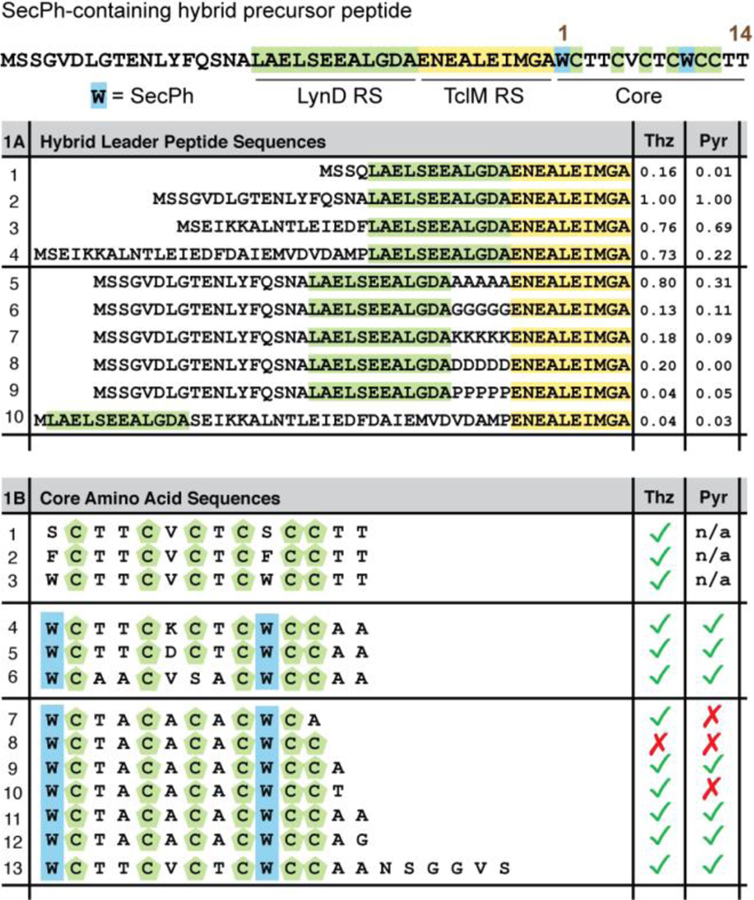

We next began to explore the requirements of the designer leader peptide. The N-termini of natural thiopeptide leader peptides have been implicated in an affinity-enhancing interaction with pyridine synthase enzymes.29 Although our studies have shown this interaction dispensable for pyridine synthase processing, 22 we chose to test the potential impact of changes to the N-terminus on processing of designer leader peptide substrates. Thus, we prepared two new hybrid substrates in which we replaced the original pMCSG7-derived N-terminus with two different excerpts from the N-terminus of TclE, the native precursor peptide for TclM (Table 1A, entries 3 and 4). In a third substrate we truncated the leader peptide leaving only a short MSSQ tag before the LynD RS (Table 1A, entry 1). The relative impact of these changes was assessed by integration of extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for the product (Table 1A, entry 2; Figure 2c,d). Interestingly, the TclE fragment sequences decrease thiopeptide formation and seem to negatively impact LynD processing. Moreover, removal of the pMCSG7-derived sequence greatly reduces processing by LynD/TbtE pair. Taken together, these results further confirm that the N-terminus of TclE is dispensable for TclM processing but LynD may be sensitive to the location of its cognate RS within the larger peptide context. To further probe the latter aspect, we designed a series of leader sequences, in which spacers were introduced between the LynD RS and TclM RS (Table 1A, entries 5–9).20 In almost all cases, the substrates were converted to thiopeptides, suggesting that LynD is broadly tolerant of diverse sequence space between the RS and core, although at reduced efficiency. As an extreme example of this spacing promiscuity, a substrate with the LynD RS sequence N-terminal to the complete native TclE leader peptide was made and subsequently processed to the mature thiopeptide (Table 1A, entry 10). This last result suggests a potentially broadly applicable strategy for circumventing reconstitution of all pathway enzymes in thiopeptide formation: express the full leader as a C-terminal fusion to LynD RS.

Table 1.

Results of flexizyme-enabled benchtop biosynthesis with mutant leader peptides (1A)a and Cores (1B).b

|

EIC area relative to entry 2 as a standard.

Checks indicate a detected EIC. An “X” indicates no EIC detected above the noise threshold of 1.0E2.

We next examined allowable changes to the core sequence. The TclM-containing thiocillin pathway has been shown to tolerate a wide array of changes to the core peptide in vivo; we therefore focused on changes to the core that were unproductive in those studies (Table 1B, entries 4 and 5).13,30 For example, Val6 of native thiocillin had been recalcitrant to charged or hydrophilic residues, such as lysine or aspartic acid. This limitation is a barrier to antibiotic development, as Val6 appears to be an ideal position for modulating the solubility.31 In contrast, hybrid substrates bearing a V6D or V6K mutation were readily transformed to the cyclic thiopeptide in vitro. Additionally, the LynD/TbtE pair in vitro provided greater product control relative to the native thiocillin enzymes, TclI, TclJ, and TclN, as exemplified by a C7S mutant (Table 1B, entry 6). In the in vivo system, a similar mutant gave mixtures of different modifications and apparent misprocessing. LynD, however, modifies all cysteines indiscriminately and left the newly introduced serine untouched. We focused considerably more mutagenesis on the C-terminus of the core, because studies have suggested TclM might be sensitive to C-terminal modifications, 22,32 and such modifications would be necessary for linking the current hybrid substrates with mRNA display in the future (Table 1B, entries 7–13). Deletion of even one amino acid from the C-terminus was unfavorable for TclM and/or LynD processing (Table 1B, entries 7–10). In contrast, extending the C-terminus (Table 1B, entry 13) did not significantly impact enzymatic processing. These data suggest that the hybrid strategy is amenable to C-terminal extensions and new sequences, not previously accessible by in vivo engineering approaches, although, more extensive investigations will be needed to understand the limitations.

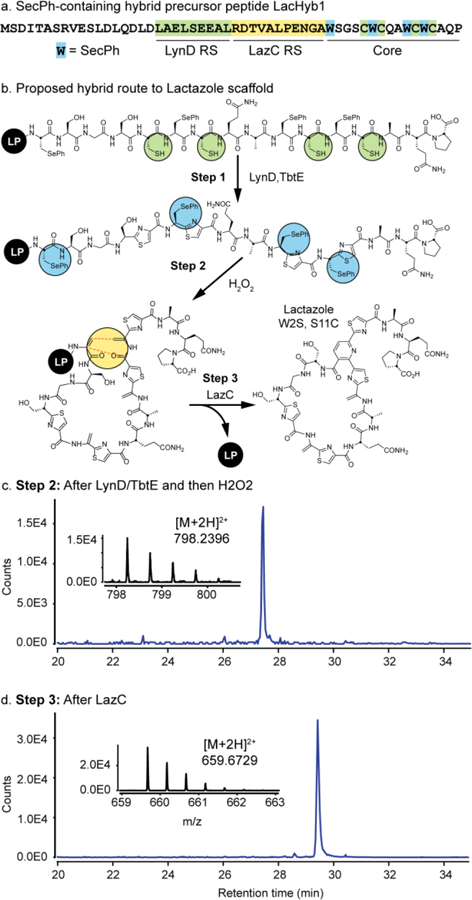

We last sought to test whether this strategy could be used to reconstitute new pyridine synthases. Recent work has suggested that only a fraction of genetically-encoded thiopeptides have been isolated.33 Of the >500 predicted thiopeptide gene clusters, the largest family is comprised of members that contain a close homolog of LazC, the predicted pyridine synthase from lactazole biosynthesis.34 Additionally, while LazC homology is high in this family, the core peptide diversity is broad, suggesting LazC and its homologs may exhibit unique substrate promiscuity (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Despite the preponderance of predicted LazC homologs, LazC has not yet been reconstituted in vitro. Therefore, we expressed and purified LazC as its MBP-fusion and designed three new hybrid sequences as potential substrates (Figure 3b). In one LazC substrate, we integrated LynD RS directly into the native lactazole leader at a site with apparent natural homology (termed LacHyb1, Figure 3a), while in the other two, LynD RS was encoded 15 or 25 residues N-terminal to the core (termed LacHyb2 and 3, respectively). Additionally, Trp2 and oxazole-forming Ser11 were replaced with a serine and thiazole-forming cysteine, respectively (see Supplementary Figure 3). Both mutations were previously produced by a gene-replacement strategy suggesting that the double mutant may also be a LazC substrate and render the core compatible with Trp-reprogramed SecPh incorporation. Upon treatment with LynD/TbtE, the four cysteines in each substrate readily underwent conversion to thiazoles and subsequent H2O2 oxidation introduced the four Dhas (Figure 3c). Lastly, treatment with LazC efficiently yielded the new, pyridine-containing masses, thus confirming activity of LazC as a pyridine synthase (Figure 3d). This result was consistent for all three hybrid lactazole leader peptides (Supplementary Fig. 4, traces S22–24 and S42–44) and suggests that the hybrid in vitro strategy should work on many other, yet uncharacterized pyridine synthases and could ultimately allow elucidation of new thiopeptides.

Figure 3.

Flexizyme-enabled benchtop biosynthesis of lactazole W2S, S11C. a) Sequence of designer precursor peptide. b) Proposed route to lactazole scaffolds. EICs for the hexathiazole and Dha-containing product of treatment with LynD/TbtE and H2O2 (c), and fully cyclized lactazole core (d).

In summary, we have developed a new, facile strategy to access thiopeptide backbones. This approach combines robust, Flexizyme-assisted incorporation of chemical handles into in vitro transcribed/translated peptides with three unrelated RiPP enzymes LynD, TbtE, and TclM by using designer leader peptides. We demonstrate the ability to make thiocillin variants previously unattainable through natural biosynthetic processes and use this strategy to reconstitute the pyridine synthase LazC to make lactazoles for the first time in vitro. We anticipate this approach will be useful in making new thiopeptide variants with therapeutic potential, studying more pyridine synthases and associated enzymes, and may aid elucidation of new thiopeptide structures. Finally, we anticipate that this strategy will be compatible with high throughput screening techniques, such as mRNA display, which is a current focus in our lab.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank C. Neumann, B. Li, and H. Onaka for informative discussions. SRF is recipient of a joint NSF/JSPS EAPSI fellowship. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM125005 (AAB).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental details, synthetic schemes, figures available at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Arnison PG; Bibb MJ; Bierbaum G; Bowers AA; Bugni TS; Bulaj G; Camarero JA; Campopiano DJ; Challis GL; Clardy J; et al. Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-Translationally Modified Peptide Natural Products: Overview and Recommendations for a Universal Nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep 2012, 30, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sardar D; Pierce E; McIntosh JA; Schmidt EW Recognition Sequences and Substrate Evolution in Cyanobactin Biosynthesis. ACS Synth. Biol 2015, 4, 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Oman TJ; van der Donk WA Follow the Leader: the Use of Leader Peptides to Guide Natural Product Biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 6, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sardar D; Lin Z; Schmidt EW Modularity of RiPP Enzymes Enables Designed Synthesis of Decorated Peptides. Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).van Heel AJ; Mu D; Montalban-Lopez M; Hendriks D; Kuipers OP Designing and Producing Modified, New-to-Nature Peptides with Antimicrobial Activity by Use of a Combination of Various Lantibiotic Modification Enzymes. ACS Synth. Biol 2013, 2, 397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Burkhart BJ; Kakkar N; Hudson GA; van der Donk WA; Mitchell DA Chimeric Leader Peptides for the Generation of Non-Natural Hybrid RiPP Products. ACS Cent Sci 2017, 3, 629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Goto Y; Suga H Engineering of RiPP Pathways for the Production of Artificial Peptides Bearing Various Non-Proteinogenic Structures. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 46, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hudson GA; Mitchell DA RiPP Antibiotics: Biosynthesis and Engineering Potential. Curr Opin Microbiol 2018, 45, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Walsh CT; Malcolmson SJ; Young TS Three Ring Posttranslational Circuses: Insertion of Oxazoles, Thiazoles, and Pyridines Into Protein-Derived Frameworks. ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7, 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhang Q; Liu W Biosynthesis of Thiopeptide Antibiotics and Their Pathway Engineering. Nat. Prod. Rep 2013, 30, 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lin Z; He Q; Liu W Bio-Inspired Engineering of Thiopeptide Antibiotics Advances the Expansion of Molecular Diversity and Utility. Curr. Opin. Biotech 2017, 48, 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Just-Baringo X; Albericio F; Alvarez M Thiopeptide Engineering: a Multidisciplinary Effort Towards Future Drugs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2014, 53, 6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bowers AA; Acker MG; Koglin A; Walsh CT Manipulation of Thiocillin Variants by Prepeptide Gene Replacement: Structure, Conformation, and Activity of Heterocycle Substitution Mutants. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 7519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Young TS; Dorrestein PC; Walsh CT Codon Randomization for Rapid Exploration of Chemical Space in Thiopeptide Antibiotic Variants. Chem. Biol 2012, 19, 1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zhang F; Kelly WL Saturation Mutagenesis of TsrA Ala4 Unveils a Highly Mutable Residue of Thiostrepton a. ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hudson GA; Zhang Z; Tietz JI; Mitchell DA; van der Donk WA In Vitro Biosynthesis of the Core Scaffold of the Thiopeptide Thiomuracin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (51), 16012–16015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhang Z; Hudson GA; Mahanta N; Tietz JI; van der Donk WA; Mitchell DA Biosynthetic Timing and Substrate Specificity for the Thiopeptide Thiomuracin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 15507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wever WJ; Bogart JW; Baccile JA; Chan AN; Schroeder FC; Bowers AA Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Thiazolyl Peptide Natural Products Featuring an Enzyme-Catalyzed Formal [4 + 2] Cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ozaki T; Yamashita K; Goto Y; Shimomura M; Hayashi S; Asamizu S; Sugai Y; Ikeda H; Suga H; Onaka H Dissection of Goadsporin Biosynthesis by in Vitro Reconstitution Leading to Designer Analogues Expressed in Vivo. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 14207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Goto Y; Ito Y; Kato Y; Tsunoda S; Suga H One-Pot Synthesis of Azoline-Containing Peptides in a Cell-Free Translation System Integrated with a Posttranslational Cyclodehydratase. Chem. Biol 2014, 21, 766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Koehnke J; Mann G; Bent AF; Ludewig H; Shirran S; Botting C; Lebl T; Houssen WE; Jaspars M; Naismith JH Structural Analysis of Leader Peptide Binding Enables Leader-Free Cyanobactin Processing. Nat. Chem. Biol 2015, 11, 558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wever WJ; Bogart JW; Bowers AA Identification of Pyridine Synthase Recognition Sequences Allows a Modular Solid-Phase Route to Thiopeptide Variants. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Okeley NM; Zhu Y; van der Donk WA Facile Chemoselective Synthesis of Dehydroalanine-Containing Peptides. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Seebeck FP; Szostak JW Ribosomal Synthesis of Dehydroalanine-Containing Peptides 2006, 128, 7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Goto Y; Katoh T; Suga H Flexizymes for Genetic Code Reprogramming. Nat Protoc 2011, 6, 779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Asahara H; Chong S In Vitro Genetic Reconstruction of Bacterial Transcription Initiation by Coupled Synthesis and Detection of RNA Polymerase Holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhou Y; Asahara H; Gaucher EA; Chong S Reconstitution of Translation From Thermus Thermophilus Reveals a Minimal Set of Components Sufficient for Protein Synthesis at High Temperatures and Functional Conservation of Modern and Ancient Translation Components. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, 7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Iwane Y; Hitomi A; Murakami H; Katoh T; Goto Y; Suga H Expanding the Amino Acid Repertoire of Ribosomal Polypeptide Synthesis via the Artificial Division of Codon Boxes. Nat. Chem 2016, 8, 317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Cogan DP; Hudson GA; Zhang Z; Pogorelov TV; van der Donk WA; Mitchell DA; Nair SK Structural Insights Into Enzymatic [4+2] Aza-Cycloaddition in Thiopeptide Antibiotic Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, 12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tran HL; Lexa KW; Julien O; Young TS; Walsh CT; Jacobson MP; Wells JA Structure-Activity Relationship and Molecular Mechanics Reveal the Importance of Ring Entropy in the Biosynthesis and Activity of a Natural Product. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Harms JM; Wilson DN; Schluenzen F; Connell SR; Stachelhaus T; Zaborowska Z; Spahn CMT; Fucini P Translational Regulation via L11: Molecular Switches on the Ribosome Turned on and Off by Thiostrepton and Micrococcin. Mol Cell 2008, 30, 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bewley KD; Bennallack PR; Burlingame MA; Robison RA; Griffitts JS; Miller SM Capture of Micrococcin Biosynthetic Intermediates Reveals C-Terminal Processing as an Obligatory Step for in Vivo Maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Schwalen CJ; Hudson GA; Kille B; Mitchell DA Bioinformatic Expansion and Discovery of Thiopeptide Antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hayashi S; Ozaki T; Asamizu S; Ikeda H; Omura S; Oku N; Igarashi Y; Tomoda H; Onaka H Genome Mining Reveals a Minimum Gene Set for the Biosynthesis of 32-Membered Macrocyclic Thiopeptides Lactazoles. Chem. Biol 2014, 21, 679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.