Abstract

Objective

To determine external genital lesion (EGL) incidence -condyloma and penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN) - and genital HPV-genotype progression to these EGLs.

Methods

Participants (healthy males 18–74y, from Cuernavaca, Mexico, recruited 2005–2009, n=954) underwent a questionnaire, anogenital examination, and sample collection every 6 months; including excision biopsy on suspicious EGL with histological confirmation. Linear array assay PCR characterized 37 high/low-risk HPV-DNA types. EGL incidence and cumulative incidence were calculated, the latter with Kaplan-Meier.

Results

EGL incidence was 1.84 (95%CI=1.42–2.39) per 100-person-years (py); 2.9% (95%CI=1.9–4.2) 12-month cumulative EGL. Highest EGL incidence was found in men 18–30 years: 1.99 (95%CI=1.22–3.25) per 100py. Seven subjects had PeIN I-III (four with HPV16). HPV11 most commonly progresses to condyloma (6-month cumulative incidence=44.4%, 95%CI=14.3–137.8). Subjects with high-risk sexual behavior had higher EGL incidence.

Conclusion

In Mexico anogenital HPV infection in men is high and can cause condyloma. Estimation of EGL magnitude and associated healthcare costs is necessary to assess the need for male anti-HPV vaccination in Mexico.

Keywords: HPV in males, condyloma, genital warts, Penile Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PeIN)

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar incidencia de lesiones genitales externas (LGE) -condiloma y neoplasia intraepitelial del pene (NIP)- y progresión de genotipos de VPH a LGE.

Métodos

Se aplicaron cuestionarios, examen anogenital y recolección de muestras cada 6 meses a hombres sanos (18–74 años, de Cuernavaca, México, reclutados 2005–2009, n=954) con biopsia y confirmación histológica. Se caracterizaron 37 tipos de ADN-VPH; se calculó incidencia de LGE (cumulativa con Kaplan-Meier).

Resultados

Incidencia de LGE=1.84 (IC95%=1.42–2.39) por 100-persona-años (pa); 2.9% (IC95%=1.9–4.2) LGE cumulativa a 12 meses. Mayor incidencia de LGE entre hombres 18–30 años; 1.99 (IC95% =1.22–3.25) por 100pa. Siete sujetos tuvieron NIP I-III. VPH11 más comúnmente progresa a condiloma (incidencia cumulativa a 6 meses=44.4%, IC95%=14.3–137.8). Sujetos con comportamiento sexual de alto riesgo tuvieron mayor incidencia de LGE.

Conclusiones

En México infección anogenital con VPH es alta y puede causar condiloma. Estimación de magnitud de LGE y costos sanitarios asociados se necesita para evaluar la necesidad de vacunación contra VPH en hombres.

Keywords: VPH en hombres, condiloma, verrugas genitales, neoplasia intraepitelial del pene

Introduction

The burden of disease of condyloma (genital warts) has been documented, particularly in women, through epidemiological studies,1,2 population-based cohort studies3 and follow-up to randomized clinical trials to assess the efficacy of anti-HPV vaccines for those randomized to placebo4. It has also been estimated in external impact evaluation after introduction of anti-HPV vaccination in specific populations5. Various studies have established that on a population level, around 5–10% of people have a condyloma diagnosis in their lifetime6. Moreover, an estimated 90% of condyloma can be attributed to HPV types 6 and 11, which are considered low-risk for developing cervical neoplasia7. Risk for persistence of an infection increases significantly with a history of a prior episode of condyloma.8 Also, implementing national anti-HPV vaccination programs, which include protection against serotypes 6 and 11, has significantly decreased the incidence of condyloma in the population9,10. Most documented scientific evidence on condyloma has been obtained in higher-income countries that have population records and automated clinical files, while there is very little evidence of the burden of condyloma in middle- and low-income countries11. In this study we present the incidence rates of EGL and progression of HPV infection to EGLs, among Mexican males who participated in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. 12,13

Methods

Design and study population

Participants were males between the ages of 18 and 74, residing in Cuernavaca, Mexico, recruited between July 2005 and June 2009.12 The HIM Study prospectively ascertained sexual behavior by questionnaire, and collected exfoliated genital specimens for HPV genotyping every 6 months for a median follow-up of ~ 4 years. A total of 1,330 men were formally recruited.14 In February 2009, a biopsy and pathology protocol was implemented. This included standardized biopsy and histopathologic confirmation procedures among men with clinical suspicion of HPV-related EGLs.13 For analysis of incident HPV, histologic analysis included men who had ≥2 visits after implementation of the pathology protocol (n=954). Close to half of the men had 5–7 visits (n=460; 48%); 33% (n=313) had 3–4 visits and 19% (n=181) had 2 visits. All participants signed an informed consent form. The study protocol was approved by the research, ethics and biosafety committees of the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico.

Sample collection of the genital surface for HPV detection

Participants underwent a clinical examination during each visit. Moistened Dacron pads were used to collect genital samples from the coronal-glans sulcus of the penis, body of the penis and scrotum.13 These samples were combined into a single sample per participant and stored at −70° C. Samples underwent DNA extraction (Qiagen Media Kit), PCR analysis, and HPV genotyping (Roche Linear Array)15. Samples that were positive for β-globin or for an HPV genotype, were considered adequate and were included in the analysis. The Linear Array Assay system was used to analyze 37 HPV types, classified as either high-risk (HR-HPV: 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68) or low-risk (LR-HPV:6/11/26/40/42/53/54/55/61/62/64/66/67/69/70/71/72/73/81/82/IS39/83/84/89)16.

Collecting External Genital Lesion (EGL) samples and HPV detection

During each visit, men had an anogenital examination under a 3x lamp by a trained physician, supervised by a urologist, to detect the presence of EGLs. A tissue sample of each lesion was obtained by tangential excision. All EGLs that appeared to be related to HPV or were of unknown etiology based on visual inspection were tested for HPV and underwent histological confirmation by pathology. EGLs were classified as condyloma, suggestive of condyloma, penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN), or unassociated with HPV, based on criteria described previously17. PeIN lesions were further classified as PeIN I (low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [SIL]), PeIN II, PeIN II/III, and PeIN III (all high grade SIL). Pathological diagnoses of EGL “suggestive of condyloma” and “condyloma” were grouped together for analysis, since the former share at least two and as many as four pathological characteristics of condyloma.

Tissues received were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded; this was done for each of the samples taken by tangential excision. DNA was extracted from these samples using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) following the established protocol. Genotyping was performed to detect HPV DNA in sample cells using an AutoBlot 3000H (MedTec Biolab) processor, and the HPV INNO-LiPA Genotyping Extra (Fujirebio) test, which detects 28 HPV types (HR-HPV: 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68; LR-HPV: 6/11/26/40/43/44/53/54/66/69/70/71/73/74/82).18

Statistical Analysis

EGL Incidence

Men with a prevalent lesion were excluded from this analysis. We did descriptive analysis of the demographic characteristics and sexual practices of all males in the cohort, whether or not they developed EGL during the follow-up. A specific analysis by age was performed for men who developed incident EGL within this cohort, stratified by age groups as follows: 18–30, 31–44, and 45–74 years.

Only the first EGL developed was included in EGL incidence analyses. Incidence was calculated from the beginning of the biopsy cohort until the date when the first EGL was detected. Person-time incidence was calculated, and 95% confidence intervals were based on the number of occurrences modeled as a Poisson variable for the total number of person-months. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated for the incidence of EGL, and EGL incidence was compared over time in all three age groups using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence of development of an EGL was also estimated in the first 12 months of follow-up using the Kaplan-Meier method.

For specific analyses of a given genotype, all prevalent and incident lesions were included. Besides specific HPV types, positive infections for ≥1 type were included in the group of any HPV; those positive for ≥1 high-risk HPV type were included in the high-risk HPV group; and those positive for ≥1 low-risk types were included in the low-risk HPV group. Independent analyses were performed for high-risk and low-risk infections. EGLs that were positive for ≥1 high-risk HPV types and ≥1 low-risk HPV types were included in the HR/LR-HPV group.

Progression of HPV infection to EGL

Among men (without prevalent condyloma or PeIN) with an incident or prevalent genital HPV infection, the rate and proportion of men progressing to an EGL was estimated. Demographic characteristics were compared among men who developed or failed to develop an EGL using Monte Carlo estimates of exact Pearson’s chi-square test. HPV infection was described by genotype or group (any, HR-HPV, LR-HPV). Classification as any HPV type was defined as a positive test result for at least one of the 25 HPV genotypes (HPV types 43/44/74 are not detected through Linear Array Assay) using INNO-LiPA. HPV infections by a single or multiple HR-HPV types were classified as high-risk and infections by at least one of the LR-HPV types were classified as low-risk.

The cumulative incidence of EGLs at 6, 12, and 24 months and the median time to EGL development for individual HPV types was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method for grouped datasets19 since men could have been infected with multiple HPV types within a given group; also, multiple HPV types can be detected in a single EGL, and a man may develop multiple EGLs. The global incidence rate of EGL during the study period was also calculated.

Results

Incidence of External Genital Lesions

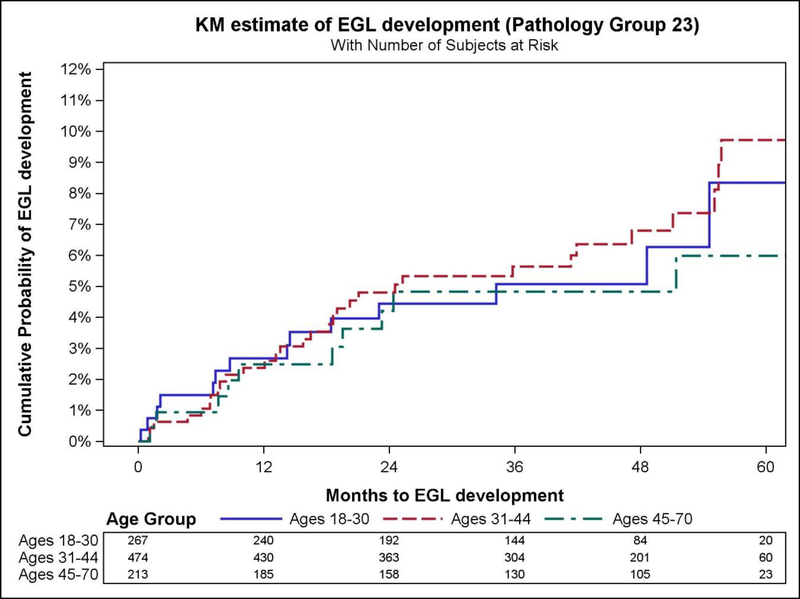

The prevalence of extra-genital lesions at baseline (during the initial visit) was 2.2% while the prevalence of genital warts was 6.6% at baseline. EGL incidence was associated with sexual orientation (p=0.007), total number of lifetime female partners (p=0.003) and male partners (p=0.006) (Table 1). Overall EGL incidence rate (IR) was 1.84 (95%CI=1.42–2.39) per 100 person-years (py). The cumulative risk of EGL at 12 months was 2.9% (95%CI=1.9–4.2). The highest incidence of EGL was observed among men ages 18–30 years (IR=1.99 per 100py, 95% CI=1.22–3.25) and 31–44 years (IR=1.96 per 100py, 95%CI=1.38–2.78), although the IR did not significantly differ between the three age categories. Also, for the combined category of condyloma and its suggested diagnosis, the highest incidence rate was observed in the 31–44 year age group. (IR=1.95 per 100py, 95%CI=1.37–2.78). Incidence of any EGL, combined condyloma, and PeIN did not significantly differ by age among men (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Differences in socio-demographic characteristics and sexual behavior among Mexican men with and without an incident EGL during follow-up.

| Mexico (n=954) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Total HIM Study Samplea | No EGL Incidence | Any Incident EGL | p Valuesb |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.39 | |||

| 18–30 | 1157(38.4%) | 243 (28.4%) | 21 (21.6%) | |

| 31–44 | 1235(41%) | 418 (48.8%) | 52 (53.6%) | |

| 45–74 | 620(20.6%) | 196 (22.9%) | 24 (24.7%) | |

| Years of Education | 0.44 | |||

| Completed 12 Years or Less | 1319(43.8%) | 551 (64.3%) | 56 (57.7%) | |

| 13–15 Years | 774(25.7%) | 74 (8.6%) | 12 (12.4%) | |

| Completed at Least 16 Years | 907(30.1%) | 228 (26.6%) | 29 (29.9%) | |

| Refused | 10(0.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 2(0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.48 | |||

| Single | 1148(38.1%) | 139 (16.2%) | 13 (13.4%) | |

| Married/Cohabiting | 1557(51.7%) | 657 (76.7%) | 76 (78.4%) | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 298(9.9%) | 58 (6.8%) | 7 (7.2%) | |

| Refused | 7(0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Missing | 2(0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Circumcised | 0.76 | |||

| No | 1906(63.3%) | 721 (84.1%) | 83 (85.6%) | |

| Yes | 1106(36.7%) | 136 (15.9%) | 14 (14.4%) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.45 | |||

| Current | 691(22.9%) | 276 (32.2%) | 38 (39.2%) | |

| Former | 948(31.5%) | 248 (28.9%) | 26 (26.8%) | |

| Never | 1322(43.9%) | 293 (34.2%) | 30 (30.9%) | |

| Missing | 51(1.7%) | 40 (4.7%) | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Alcohol per Month | 0.87 | |||

| 0 drinks | 690(22.9%) | 211 (24.6%) | 27 (27.8%) | |

| 1–30 drinks | 1293(42.9%) | 408 (47.6%) | 46 (47.4%) | |

| >30 drinks | 898(29.8%) | 166 (19.4%) | 20 (20.6%) | |

| Missing | 131(4.3%) | 72 (8.4%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Sexual Orientation | 0.007 | |||

| MSWc | 2341(77.7%) | 748 (87.3%) | 77 (79.4%) | |

| MSM | 80(2.7%) | 8 (0.9%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| MSMW | 428(14.2%) | 64 (7.5%) | 13 (13.4%) | |

| Missing | 163(5.4%) | 37 (4.3%) | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Total Number of Female Partners | 0.003 | |||

| 0–1 | 395(13.1%) | 115 (13.4%) | 5 (5.2%) | |

| 2–9 | 1123(37.3%) | 472 (55.1%) | 42 (43.3%) | |

| 10–49 | 1149(38.1%) | 242 (28.2%) | 43 (44.3%) | |

| 50+ | 269(8.9%) | 14 (1.6%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Refused | 76(2.5%) | 14 (1.6%) | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Total Number of Male Partners | 0.006 | |||

| 0 | 2466(81.9%) | 778 (90.8%) | 80 (82.5%) | |

| 1–9 | 364(12.1%) | 65 (7.6%) | 13 (13.4%) | |

| 10+ | 144(4.8%) | 7 (0.8%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Missing | 38(1.3%) | 7 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

Total HIM study sample for Mexico, Brazil and the United States (n=3012).

P values were calculated using Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests comparing characteristics of men with and without EGL.

MSW=men who have sex with women; MSM=men who have sex with men; MSMW=men who have sex with men and women.

Table 2.

Age-specific incidence of pathologically confirmed external genital lesions (EGLs) among Mexican men in the HIM Study.

| Pathological Diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any typea | Condyloma | Suggestive of condylomab | Combined Condylomac | PeINd | Othere | |

| All ages (n=954)f | ||||||

| Men with incident EGL, no. | 57 | 23 | 39 | 55 | 3 | 46 |

| Person-months | 37169 | 37945 | 37972 | 37272 | 38697 | 37584 |

| Incidence rateg (95% CI) | 1.84(1.42–2.39) | 0.73(0.48–1.09) | 1.23(0.9–1.69) | 1.77(1.36–2.31) | 0.09(0.03–0.29) | 1.47(1.1–1.96) |

| 12-month Incidence | 2.9(1.9–4.2) | 1.5(0.9–2.6) | 1.1(0.6–2) | 2.5(1.7–3.8) | 0.3(0.1–1) | 2.3(1.5–3.5) |

| 18–30 y (n=267) | ||||||

| Men with incident EGL, no. | 16 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 2 | 7 |

| Person-months | 9654 | 9911 | 9894 | 9736 | 10039 | 9994 |

| Incidence rateg (95% CI) | 1.99(1.22–3.25) | 0.73(0.33–1.62) | 1.21(0.65–2.25) | 1.73(1.02–2.91) | 0.24(0.06–0.96) | 0.84(0.4–1.76) |

| 12-month Incidence | 3.5(1.8–6.8) | 1.6(0.6–4.1) | 1.6(0.6–4.1) | 2.7(1.3–5.7) | 0.8(0.2–3.1) | 1.2(0.4–3.6) |

| 31–44 y (n=474) | ||||||

| Men with incident EGL, no. | 31 | 14 | 22 | 31 | 1 | 27 |

| Person-months | 19026 | 19347 | 19453 | 19047 | 19836 | 19080 |

| Incidence rateg (95% CI) | 1.96(1.38–2.78) | 0.87(0.51–1.47) | 1.36(0.89–2.06) | 1.95(1.37–2.78) | 0.06(0.01–0.43) | 1.7(1.16–2.48) |

| 12-month Incidence | 2.6(1.5–4.6) | 1.7(0.9–3.5) | 0.6(0.2–2) | 2.4(1.3–4.3) | 0.2(0–1.5) | 3.1(1.8–5.2) |

| 45–74 y (n=223) | ||||||

| Men with incident EGL, no. | 10 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 12 |

| Person-months | 8489 | 8687 | 8625 | 8489 | 8823 | 8510 |

| Incidence rateg (95% CI) | 1.41(0.76–2.63) | 0.41(0.13–1.28) | 0.97(0.46–2.04) | 1.41(0.76–2.63) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 1.69(0.96–2.98) |

| 12-month Incidence | 2.5(1–6) | 1(0.2–4) | 1.5(0.5–4.6) | 2.5(1–6) | 2(0.7–5.3) | |

| p-valueh | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

Abbreviation: 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Men with ≥1 incident, pathologically confirmed HPV-related EGL throughout the study period. For men with >1 EGL, incidence rates for the Any EGL category are determined for the first detected lesion; thus, men may contribute fewer person-months in this category than for specific pathological diagnoses

Includes lesions suggestive but not diagnostic of HPV infection or condyloma

Includes both Condyloma and Suggestive of Condyloma categories

PeIN = penile intraepithelial neoplasia (I–III)

Includes various HPV-unrelated skin conditions, such as seborrheic keratosis and skin tags

7 men with prevalent EGLs were excluded from the initial cohort for this analysis

Specified as the number of cases per 100 person-years

Determined using the log-rank test and corresponding to overall differences in EGL incidence across the entire follow-up period, by age group. Values < .05 are considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing differences in cumulative incidence of external genital lesions (EGLs) by age group, Mexican men in the HIM Study.

Progression of HPV infection to EGL

Among the 954 men with at least two follow up visits, 519 had a prevalent or incident HPV infection. In thirty-three of these men HPV progressed to a lesion with the same HPV type detected within the lesion (Table 3). There were no statistically significant differences between HPV-positive men that did and did not develop an EGL. Correspondingly, 31.2% of HPV-6 infections progressed to HPV6-positive condyloma and 28.6% of HPV-11 infections progressed to HPV11-positive condyloma (Table 3). In addition, the median time for progression of an infection with any type of HPV to condyloma (with DNA for that same type of HPV detected in the lesion) was 8.7 person-months. Progression from an infection with a HR-HPV type took a median time of 7.6 person-months while progression from LR-HPV types took a median time of 10.8 person-months (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of characteristics among human papillomavirus–positive men who did and did not develop an external genital lesion during follow-up in the HIM study

| Factors | Total N (%) | No EGL Incidence N (%) | Any EGL Incidence N (%) | P Value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.8280 | |||

| 18–30 | 162 (31.2%) | 152 (31.3%) | 10 (30.3%) | |

| 31–44 | 243 (46.8%) | 226 (46.5%) | 17 (51.5%) | |

| 45–74 | 114 (22%) | 108 (22.2%) | 6 (18.2%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Years of Education | 0.5640 | |||

| Completed 12 Years or Less | 333 (64.2%) | 310 (63.8%) | 23 (69.7%) | |

| 13–15 Years | 48 (9.2%) | 44 (9.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | |

| Completed at Least 16 Years | 137 (26.4%) | 131 (27%) | 6 (18.2%) | |

| Refused | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.8910 | |||

| Single | 93 (17.9%) | 86 (17.7%) | 7 (21.2%) | |

| Married/Cohabiting | 377 (72.6%) | 354 (72.8%) | 23 (69.7%) | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 48 (9.2%) | 45 (9.3%) | 3 (9.1%) | |

| Refused | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Circumcised | 0.8060 | |||

| No | 444 (85.5%) | 415 (85.4%) | 29 (87.9%) | |

| Yes | 75 (14.5%) | 71 (14.6%) | 4 (12.1%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.7840 | |||

| Current | 193 (37.2%) | 179 (36.8%) | 14 (42.4%) | |

| Former | 142 (27.4%) | 132 (27.2%) | 10 (30.3%) | |

| Never | 165 (31.8%) | 156 (32.1%) | 9 (27.3%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Missing | 19 (3.7%) | 19 (3.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Alcohol per Month | 0.8010 | |||

| 0 | 126 (24.3%) | 116 (23.9%) | 10 (30.3%) | |

| 1–30 | 246 (47.4%) | 231 (47.5%) | 15 (45.5%) | |

| >30 | 111 (21.4%) | 104 (21.4%) | 7 (21.2%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Missing | 36 (6.9%) | 35 (7.2%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Sexual Orientation2 | 0.3590 | |||

| MSM | 8 (1.5%) | 7 (1.4%) | 1 (3%) | |

| MSMW | 44 (8.5%) | 39 (8%) | 5 (15.2%) | |

| MSW | 445 (85.7%) | 419 (86.2%) | 26 (78.8%) | |

| Missing | 22 (4.2%) | 21 (4.3%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Total Number of Female Partners | 0.0910 | |||

| 0–1 | 48 (9.2%) | 47 (9.7%) | 1 (3%) | |

| 2–9 | 254 (48.9%) | 239 (49.2%) | 15 (45.5%) | |

| 10–49 | 194 (37.4%) | 181 (37.2%) | 13 (39.4%) | |

| 50+ | 12 (2.3%) | 9 (1.9%) | 3 (9.1%) | |

| Refused | 11 (2.1%) | 10 (2.1%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Total Number of Male Partners | 0.2240 | |||

| 0 | 463 (89.2%) | 436 (89.7%) | 27 (81.8%) | |

| 1–9 | 44 (8.5%) | 39 (8%) | 5 (15.2%) | |

| 10+ | 8 (1.5%) | 7 (1.4%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Total | 519 (100%) | 486 (93.6%) | 33 (6.4%) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.8%) | 4 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

n=519 men participating in the HIM study in Mexico who had ≥2 study follow-up visits after February 2009 and who, if they had an EGL which was suspected to be HPV-related, underwent standardized biopsy and histopathologic confirmation procedures.

P values were calculated using Monte Carlo estimation of exact Pearson chi-square tests comparing characteristics of men with and without EGL.

MSW=men who have sex with women; MSM=men who have sex with men; MSMW=men who have sex with men and women.

Table 4.

Progression of genital human papillomavirus (HPV)* infection to condyloma**with the same HPV type detected in the lesion among Mexican men in the HIM study.

| HPV type | Proportion of HPV infections that progress,a No./total (%) | Median timeb |

|---|---|---|

| Any type of HPV | 36/1103 (3.3) | 8.7 |

| High-risk | 6/638 (0.9) | 7.6 |

| 16 | 0/86 (0.0) | 0 |

| 18 | 0/26 (0.0) | 0 |

| 31 | 1/47 (2.1) | 5.8 |

| 33 | 0/9 (0.0) | 0 |

| 35 | 0/5 (0.0) | 0 |

| 39 | 0/67 (0.0) | 0 |

| 45 | 0/34 (0.0) | 0 |

| 51 | 1/103 (1.0) | 8.4 |

| 52 | 3/72 (4.2) | 7.8 |

| 56 | 1/32 (3.1) | 0.4 |

| 58 | 0/44 (0.0) | 0 |

| 59 | 0/95 (0.0) | 0 |

| 68 | 0/18 (0.0) | 0 |

| Low-risk | 30/465 (6.5) | 10.8 |

| 6 | 24/77 (31.2) | 14.3 |

| 11 | 4/14 (28.6) | 0.9 |

| 26 | 0/2 (0.0) | 0 |

| 40 | 0/26 (0.0) | 0 |

| 53 | 0/95 (0.0) | 0 |

| 54 | 1/39 (2.6) | 7.8 |

| 66 | 1/90 (1.1) | 17.2 |

| 69 | 0/5 (0.0) | 0 |

| 70 | 0/36 (0.0) | 0 |

| 71 | 0/48 (0.0) | 0 |

| 73 | 0/21 (0.0) | 0 |

| 82 | 0/12 (0.0) | 0 |

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Newly acquired, pathologically confirmed EGL.

The unit of analysis is genital HPV infection.

Median time to progression of genital HPV infection to condyloma, in person-months.

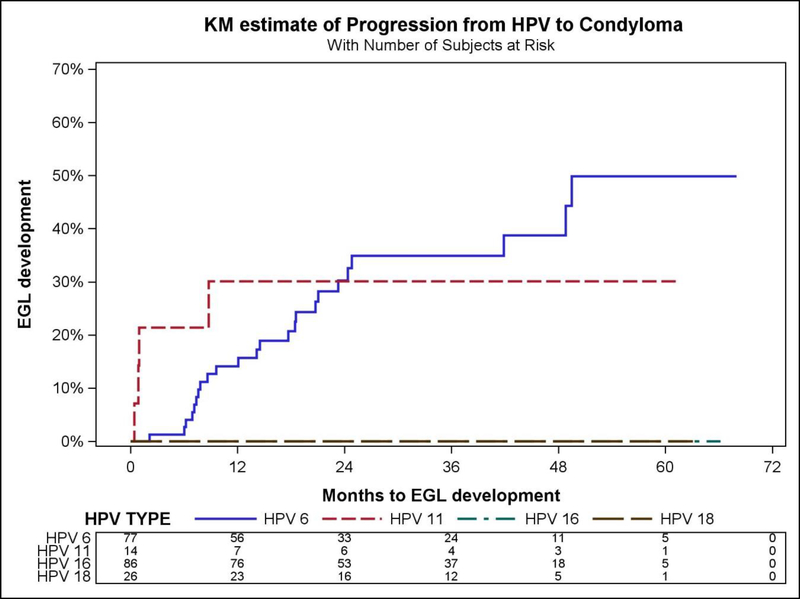

The highest condyloma incidence was found in Mexican males with HPV-6 (12.2 per 1000 person-months (pm), 95%CI=8.2–18.2) and HPV-11 (12.3 per 1000pm, 95%CI=4.6–32.8). The highest cumulative incidence of condyloma at 6 months (44.4% 95%CI=14.3–137.8) occurred in men with HPV-11. For HPV-6, the cumulative incidence increased from 2.2% (95%CI=0.3–15.6) at 6 months, to 12.2% (95%CI=6.5–22.6) at 12 months and 14.1% (95%CI=9.0–22.1) at 24 months (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 5.

Incidence of condylomaa by human papillomavirus (HPV) type detected in the lesionb among Mexican men with the same HPV type detected on the genitals,c HIM Study.

| HPV Typed,e | Incidence Ratef (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6m (95% CI) | 12m (95% CI) | 24m (95% CI) | ||

| Any Type | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 1.6 (1.0–2.5) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) |

| High-Risk | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) |

| 31 | 0.7 (0.1–4.7) | 3.6 (0.5–25.2) | 1.8 (0.3–13.1) | 1.0 (0.1–7.2) |

| 51 | 0.3 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.8 (0.1–6.0) | 0.5 (0.1–3.3) |

| 52 | 1.2 (0.4–3.8) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.5 (0.6–9.8) | 1.4 (0.3–5.5) |

| 56 | 0.9 (0.1–6.4) | 5.4 (0.8–38.3) | 2.9 (0.4–20.8) | 1.6 (0.2–11.6) |

| Low-Risk | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | 1.5 (0.5–3.9) | 2.9 (1.7–4.8) | 2.7 (1.8–4.0) |

| 6 | 12.2 (8.2–18.2) | 2.2 (0.3–15.6) | 12.2 (6.5–22.6) | 14.1 (9.0–22.1) |

| 11 | 12.3 (4.6–32.8) | 44.4 (14.3–137.8) | 33.6 (12.6–89.6) | 19.9 (7.5–53.0) |

| 54 | 0.7 (0.1–5.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 2.2 (0.3–15.7) | 1.2 (0.2–8.7) |

| 66 | 0.3 (0.0–2.4) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.6 (0.1–3.9) |

| Vaccineg | 4.8 (3.3–6.9) | 3.4 (1.3–8.9) | 6.3 (3.7–10.6) | 6.0 (4.0–9.1) |

CI = confidence interval

Newly acquired, pathologically confirmed condyloma/suggestive of condyloma.

DNA detected using INNO LiPA.

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Prevalent and incident genital HPV infections.

HPV types 16/18/33/35/39/45/58/59/68/26/40/53/69/70/71/73/82 did not progress to a condyloma lesion; therefore, incidence rates and cumulative incidence could not be calculated.

Incidence rate is cases per 1000 person-months.

Vaccine HPV types 6/11/16/18.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing differences in cumulative incidence of combined condyloma progression of HPV to condyloma by HPV type, Mexican men in the HIM Study.

Seven men developed PeIN lesions. There were three HPV-positive men that developed type-specific PeIN lesions during follow-up that had both high- and low-risk types while 4 had only low risk types. Four men had PeIN lesions with HPV type 16; 2 men had lesions with type 51; 3 men had type 11 and 1 man had type 6. Two of the HPV16 genital infections progressed to HPV16-positive PeIN lesions and two HPV11 genital infections progressed to HPV11-positive PeIN lesions. The highest incidence rate of progression of HPV to PeIN occurred with HPV-11 at 2.5 per 1000pm (95% CI=0.3–17.4) (Table 6). The cumulative incidence of PeIN in men with HPV-11 was 12.7 % (95% CI=1.8–90.4) at 6 months and 6.9 % (95% CI=1.0–48.9) at 12 months.

Table 6.

Incidence of penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN)a by human papillomavirus (HPV) type detected in the lesionb with the same HPV type detected on the genitalsc among Mexican men in the HIM Study.

| HPV Typed,e | Incidence Ratef (95% CI) | Cumulative Incidence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6m (95% CI) | 12m (95% CI) | 24m (95% CI) | ||

| Any Type | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) |

| High-Risk | 0.1 (0.0–0.4) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1) | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 0.2 (0.0–0.6) |

| 16 | 0.7 (0.2–3.0) | 4.0 (1.0–15.9) | 2.1 (0.5–8.2) | 1.2 (0.3–4.7) |

| Low-Risk | 0.1 (0.0–0.5) | 0.7 (0.2–2.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.8) |

| 6 | 0.4 (0.1–2.8) | 2.2 (0.3–15.4) | 1.2 (0.2–8.2) | 0.7 (0.1–4.6) |

| 11 | 2.5 (0.3–17.4) | 12.7 (1.8–90.4) | 6.9 (1.0–48.9) | 4.0 (0.6–28.6) |

| Vaccineg | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 3.3 (1.3–8.9) | 1.8 (0.7–4.7) | 1.0 (0.4–2.7) |

CI = confidence interval;

Newly acquired, pathologically confirmed penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PeIN).

DNA detected using INNO LiPA.

DNA detected using Linear Array.

Prevalent and incident genital HPV infections.

HPV types 18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68/26/40/53/54/66/69/70/71/73/82 did not progress to a PeIN; therefore, incidence rates and cumulative incidence could not be calculated.

Incidence rate is cases per 1000 person-months.

Vaccine HPV types 6/11/16/18.

Discussion

This is one of the first reports on incidence of EGLs in Mexico, as well as the frequency of PeIN. This is particularly significant, since no specific information is available on the Mexican and Latin American context regarding the burden of condyloma, or cancer precursor lesions of the penis (PeIN).

Our study in a population of healthy Mexican males indicates that anogenital HPV infection is endemic, that infection with HPV-6 and 11 is high, and that these infections progress to condyloma at a high rate. In addition, along with high-risk HPV types such as type 16, these infections are the main determining factor for penile cancer and precursor lesions. The proportion of subjects with HPV types that progress to low and high grade PeIN is relatively low, yet it is relevant, since it is a precursor to penile cancer.

Condyloma has been associated with poor quality of life20 and negative psychosocial impact;21 also, treatment is costly22 and recurrence rates are high (10–40%)23,24 The frequency of condyloma is high in high-income countries, where it is estimated that 1 in every 10 women will have had a condyloma diagnosis before age 45.22 Thus HPV infection, including condyloma, is an important cause of morbidity and risk in public health, considering its high incidence, recurrence and persistence. In middle- and lower- income countries like Mexico, data such as that presented by the current study indicates that the situation is similar. Paradoxically, HPV can cause benign and malignant lesions that are often difficult to treat, yet infections can be prevented by vaccination. Studies in the Latin American region have shown that anti-HPV vaccination can reduce the risk of condyloma by up to 67%25, and at present this is the only type of intervention that protects against HPV types 6 and 1126, which cause most condyloma,25 as well as laryngeal papillomatosis27 and oropharyngeal cancer.28

The burden of condyloma has been quantified mainly in higher-income countries, where sexually transmitted infections are considered a public health problem given the scientific evidence showing their high incidence and high healthcare costs.29 In many areas, introduction of anti-HPV vaccination for males could be especially beneficial to men who have sex with men30. However, other than the HIM Study, there are no sizeable longitudinal studies that assess the natural history of condyloma in middle- and low-income countries. As a result of this lack of scientific evidence, this public health problem is underestimated and therefore also the possible benefits of vaccination among men.

In the Mexican National Health System, most condyloma are treated in primary healthcare centers with medication31. Recurrent lesions are referred for surgical removal, diathermia, cryotherapy or laser treatment, or to gynecology, urology and/or dermatology units. However, in this healthcare system there are no specialized clinics for sexually transmitted infections except those to diagnose, treat and follow-up individuals with HIV. Consequently, in Mexico, and most likely in the Latin American region in general, it is imperative that the number of medical visits for condyloma be quantified to estimate related healthcare costs.

Vaccination of males in Mexico is justified given that the burden of disease attributed to HPV manifests not only as EGLs but that the fraction of penile cancer attributable to HPV32 is almost 60%. Also, oropharyngeal cancer among men (75% of which is attributable to HPV) will soon surpass cervical cancer in some populations33. This is why an aggressive HPV vaccination and screening policy (which combines primary and secondary prevention)34 is necessary35 to decrease the burden of HPV-related diseases36.

A potential limitation of the study is that the findings are not necessarily generalizable to all men in Mexico. As HPV incidence was based on clinic visits, which occurred every six- months, this might not reflect the exact timing of infection.

Conclusion

Condyloma should be considered a public health issue, as has been documented in large longitudinal studies to characterize the natural history of HPV in women37 and men38. Standardized guidelines for diagnosis and management of condyloma are needed11. Current discussion has focused on whether it makes sense to introduce anti-HPV vaccines in vulnerable groups of males and females who are at a higher risk of exposure to HPV types 6 and 11, which are responsible for most condyloma, including children who are victims of sexual abuse39. Until effective treatment for HPV infection is available, primary prevention (i.e., vaccination) will be the main strategy implemented to control this sexually transmitted infection40 and consequently EGLs and precursor lesions for cancer. An intervention that integrates both proposed actions (vaccination and standardized diagnosis and management) would constitute an organized social response to control one of the most recurrent sexually transmitted diseases, condyloma.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

We thank the HIM Study teams and participants from Mexico (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social and Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca).

Funding

The HIM Study infrastructure is supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [R01 CA098803 to A.R.G.] and the National Institute of Public Health from Mexico. Likewise, Merck provided financial support for the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

A.R.G., L.L.V. and E.L.P. are members of the Merck Advisory Board. S.L.S. received a grant (IISP53280) from Merck Investigator Initiated Studies Program. No conflicts of interest were declared for any of the remaining authors.

References

- 1.Kjaer SK, Tran TN, Sparen P, Tryggvadottir L, Munk C, Dasbach E, et al. The burden of genital warts: a study of nearly 70,000 women from the general female population in the 4 Nordic countries. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1447–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinh TH, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Markowitz LE. Genital warts among 18- to 59-year-olds in the United States, national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2004. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(4):357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kraut AA, Schink T, Schulze-Rath R, Mikolajczyk RT, Garbe E. Incidence of anogenital warts in Germany: a population-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominiak-Felden G, Gobbo C, Simondon F. Evaluating the Early Benefit of Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine on Genital Warts in Belgium: A Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikolajczyk RT, Kraut AA, Horn J, Schulze-Rath R, Garbe E. Changes in incidence of anogenital warts diagnoses after the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in Germany-an ecologic study. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(1):28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park IU, Introcaso C, Dunne EF. Human Papillomavirus and Genital Warts: A Review of the Evidence for the 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61Suppl 8:S849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garland SM, Steben M, Sings HL, James M, Lu S, Railkar R, et al. Natural history of genital warts: analysis of the placebo arm of 2 randomized phase III trials of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(6):805–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stensen S, Kjaer SK, Jensen SM, Frederiksen K, Junge J, Iftner T, et al. Factors associated with type-specific persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(2):361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollerup S, Baldur-Felskov B, Blomberg M, Baandrup L, Dehlendorff C, Kjaer SK. Significant Reduction in the Incidence of Genital Warts in Young Men 5 Years Into the Danish Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program for Girls and Women. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(4):238–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow EP, Read TR, Wigan R, Donovan B, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, et al. Ongoing decline in genital warts among young heterosexuals 7 years after the Australian human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programme. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91(3):214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sudenga SL, Ingles DJ, Pierce Campbell CM, Lin HY, Fulp WJ, Messina JL, et al. Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection Progression to External Genital Lesions: The HIM Study. Eur Urol. 2016;69(1):166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giuliano AR, Lazcano E, Villa LL, Flores R, Salmeron J, Lee JH, et al. Circumcision and sexual behavior: factors independently associated with human papillomavirus detection among men in the HIM study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(6):1251–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudenga SL, Ingles DJ, Pierce Campbell CM, Lin HY, Fulp WJ, Messina JL, et al. Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection Progression to External Genital Lesions: The HIM Study. Eur Urol. 2016;69(1):166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, Villa LL, Lazcano E, Papenfuss MR, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):932–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998;36(10):3020–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cogliano V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F; WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer. Carcinogenicity of human papillomaviruses. Lancet Oncol. 2005. April;6(4):204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anic GM, Messina JL, Stoler MH, Rollison DE, Stockwell H, Villa LL, et al. Concordance of human papillomavirus types detected on the surface and in the tissue of genital lesions in men. Journal of medical virology. 2013;85(9):1561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coutlée F, Rouleau D, Petignat P, Ghattas G, Kornegay JR, Schlag P, Boyle S, Hankins C, Vézina S, Coté P, Macleod J, Voyer H, Forest P, Walmsley S; Canadian Women’s HIV study Group, Franco E. Enhanced detection and typing of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in anogenital samples with PGMY primers and the Linear array HPV genotyping test. J Clin Microbiol. 2006. June;44(6):1998–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ying Z, Wei L. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for dependent failure time observations. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 1994;50(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodhall SC, Jit M, Soldan K, Kinghorn G, Gilson R, Nathan M, et al. The impact of genital warts: loss of quality of life and cost of treatment in eight sexual health clinics in the UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(6):458–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan LS, Chio MT, Sen P, Lim YK, Ng J, Ilancheran A, et al. Assessment of psychosocial impact of genital warts among patients in Singapore. Sex Health. 2014;11(4):313–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Östensson E, Fröberg M, Leval A, Hellström AC, Bäcklund M, Zethraeus N, et al. Cost of Preventing, Managing, and Treating Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Related Diseases in Sweden before the Introduction of Quadrivalent HPV Vaccination. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0139062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strand A, Brinkeborn R, Siboulet A. Topical treatment of genital warts in men, an open study of podophyllotoxin cream compared with solution. Genitourinary medicine. 1995;71:387–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodhall SC, Lacey CJN, Wikstrom A, et al. European Guidelines (IUSTI/WHO) on the management of anogenital warts. Poster presentation at the 25th International Papillomavirus Conference; 8–14 May 2009 Malmö, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pichon-Riviere A, Alcaraz A, Caporale J, Bardach A, Rey-Ares L, Klein K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of quadrivalent vaccine against human papilloma virus in Argentina based on a dynamic transmission model. Salud Publica Mex. 2015. December;57(6):504–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazcano-Ponce E, Pérez G, Cruz-Valdez A, Zamilpa L, Aranda-Flores C, Hernández-Nevarez P, et al. Impact of a quadrivalent HPV6/11/16/18 vaccine in Mexican women: public health implications for the region. Arch Med Res. 2009;40(6):514–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donne AJ, Hampson L, Homer JJ, Hampson IN. The role of HPV type in Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Granados-García M Oropharyngeal cancer: an emergent disease? Salud Publica Mex 2016;58:285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coles VA, Chapman R, Lanitis T, Carroll SM. The costs of managing genital warts in the UK by devolved nation: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(1):51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King EM, Gilson R, Beddows S, Soldan K, Panwar K, Young C, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA in men who have sex with men: type-specific prevalence, risk factors and implications for vaccination strategies. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(9):1585–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiménez-Vieyra CR. Prevalence of condyloma acuminata in women who went to opportune detection of cervicouterine cancer. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2010. February;78(2):99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. JNatl Cancer Inst 2013;105:175–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chatuvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(32):4294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O. Healthcare or sickcare: reestablishing the balance. Salud Publica Mex 2016;58:84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salmerón J, Torres-Ibarra L, Bosch FX, Cuzick J, Lörincz A, Wheeler CM, et al. HPV vaccination impact on a cervical cancer screening program: methods of the FASTER-Tlalpan Study in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2016;58:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmeler KM, Sturgis EM. Expanding the benefits of HPV vaccination to boys and men. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1798–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, Stern JE, Xi LF, Koutsky LA. Incident Detection of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Infections in a Cohort of High-Risk Women Aged 25–65 Years. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(5):665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyitray AG, Carvalho da Silva RJ, Chang M, Baggio ML, Ingles DJ, Abrahamsen M, et al. Incidence, duration, persistence, and factors associated with high-risk anal HPV persistence among HIV-negative men having sex with men: A multi-national study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(11):1367–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garland SM, Subasinghe AK, Jayasinghe YL, Wark JD, Moscicki AB, Singer A, et al. HPV vaccination for victims of childhood sexual abuse. Lancet. 2015. 14;386(10007):1919–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stratton KL, Culkin DJ. A Contemporary Review of HPV and Penile Cancer. Oncology (Williston Park). 2016;30(3):245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]