Abstract

Background:

Novel approaches to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption during the first 1,000 days – pregnancy through age 2 years - are urgently needed

Objective:

To examine perceptions of SSB consumption and acceptability of potential intervention strategies to promote SSB avoidance in low income families in the first 1,000 days.

Methods:

In this qualitative research, we performed semi-structured in-depth interviews of 25 women and 7 nutrition/health care providers. Eligible women were WIC-enrolled and pregnant or had an infant under age 2 years. Eligible providers cared for families during the first 1,000 days. Using immersion-crystallization techniques we examined perceptions, barriers, and facilitators related to avoidance of SSB consumption; acceptability of messages framed as positive gains or negative losses; and perceived influence on SSB consumption of various intervention modalities.

Results:

Themes related to SSB consumption included parental confusion about healthy beverage recommendations, and maternal feelings of lack of control over beverage choices due to pregnancy cravings and infant tastes. Themes surrounding message frames included: negative health consequences of sugary drink consumption are strong motivators for behavior change; and savings and cost count, but are not top priority. Highly acceptable intervention strategies included use of images showing health consequences of SSB consumption, illustrations of sugar content at the point of purchase, and multi-modal delivery of messages.

Conclusions:

Messages focused on infant health consequences and parental empowerment to evaluate and select healthier beverages based on sugar content should be tested in interventions to reduce SSB consumption in the first 1,000 days.

Keywords: obesity, nutrition, low-income

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (U.S.), childhood obesity prevalence continues to persist at historically high levels, and emerging national data suggests that children age 2–5 years are the only age group with rising obesity prevalence.1,2 Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in childhood obesity are rooted in the earliest moments of life, and risk factors during the first 1,000 days – pregnancy through age 2 years – mediate development of these disparities.3,4

Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) is a major risk factor for obesity at all periods in the life course, and emerging data suggests that SSB consumption during pregnancy has long-lasting negative health impacts on later child health.5 Recent evidence shows 14–26% of infants consume SSBs during the first year of life,6,7 increasing likelihood for later childhood obesity.6 Interventions to reduce SSB introduction during pregnancy and infancy are urgently needed to curb widening disparities in childhood obesity and downstream chronic disease, yet little is known about parental perceptions of SSB consumption and how to promote avoidance of SSB consumption during the first 1,000 days, particularly in low-income populations.

According to the theory of planned behavior, positive and negative attitudes towards behaviors, including drinking behaviors, are antecedent to intention and subsequent execution of behaviors.8 In the quantitative research phase of the NYC First 1,000 Days study of low-income, Hispanic families in New York City, 89% of parents and 66% of infants age 1–2 years habitually consumed SSBs, and more negative parental attitudes towards SSB consumption were linked to lower SSB consumption for parents and infants.9 Thus, understanding drivers of beverage attitudes and consumption will inform successful interventions to reduce SSB consumption during early life in vulnerable groups.

The overall goals of this qualitative study were to examine underlying parental and provider perceptions of beliefs, barriers, and facilitators related to avoidance of SSB consumption, and to inform development of culturally appropriate, linguistically tailored interventions to promote avoidance of SSB consumption during the first 1,000 days.

METHODS

Study Design and Approach

In the NYC First 1,000 Days study, we performed an explanatory, sequential mixed methods study (quantitative then qualitative) to examine attitudes and perceptions of beverage consumption among Hispanic/Latino families in low-income northern Manhattan neighborhoods with the highest prevalence of childhood obesity in New York City.10 Here, we present our qualitative results, where we investigated drivers of the high prevalence of SSB consumption in the first 1,000 days among the quantitative study sample, and ways to intervene. Qualitative methods are uniquely suited to reveal the unique attitudes, beliefs, and practices that lead to health behaviors in a low-income, ethnic minority population. In-depth interviews allow for a sense of confidentiality of responses and allow us to delve more deeply into individual perceptions than might be achievable in focus groups.

Study setting and participants

We conducted a total of 32 semi-structured in-depth interviews with three different groups: pregnant women, mothers of infants (child age < 2 years), and providers. From the initial cohort of 396 participants sequentially recruited from WIC visits and enrolled in the quantitative study, we purposively selected Hispanic/Latina women based on life course stage (pregnant or mother of infant) at recruitment and preferred language (English or Spanish). Women were considered eligible if they and/or their child were enrolled in WIC, could answer questions in English and/or Spanish, and were pregnant or had a child < age 2 years. Women and those with infants with chronic health conditions that impacted nutrition were excluded. All family study visits took place at the Columbia Community Partnership for Health, a neutral community-based site.

For providers, senior personnel identified key informants and sent an electronic invitation to contact research personnel if interested in participation. Providers who worked with low- income families in northern Manhattan; could respond to questions in English and/or Spanish; and were actively practicing medicine or nutrition for pregnant women or families with infants < age 2 years were eligible.

Instrument Development

We used a modified Glass and McAtee model of multi-level influences on health behaviors to guide the message frame development and potential modality of message delivery.11 We culled the literature and existing public health campaigns for interventions to reduce SSB consumption12–20 and tailored these existing healthy beverage messages for pregnant women; infants < age 2 years; and non-pregnant adults.12–14 Over multiple meetings, we developed a discussion guide (Table 1). We completed four pilot tests of the interview guides and intervention materials with women and providers from the community.

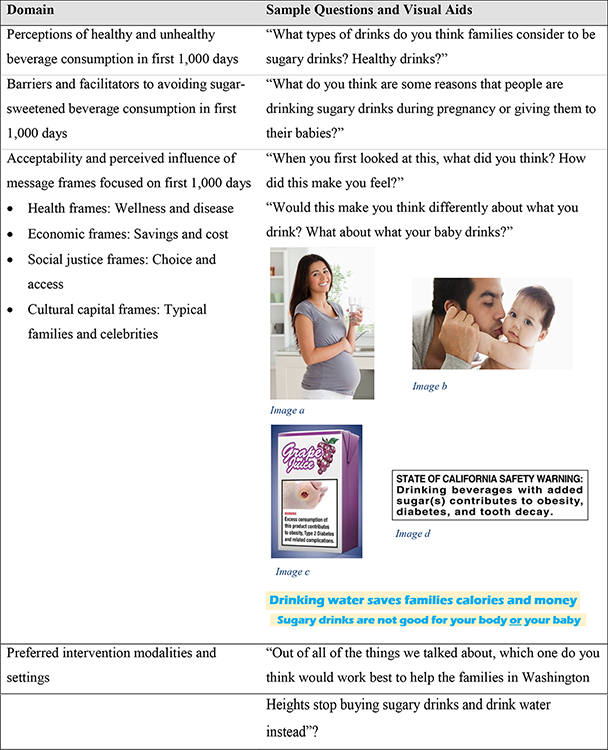

Table 1.

Semi-Structured In-depth Interview Guide Domains with Sample Questions and Visual Aids: Beverage Consumption in the First 1,000 Days.

|

Image a: Stock photo of pregnant woman drinking water, Source: DepositPhotos.

Image b: Stock photo of father kissing baby, Source: Getty images.

Image c: Image of grape juice box with diseased foot and warning message, Source: Ontario Medical Association, www.oma.org.

Image d: California proposed warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverages, Source: Public Health Advocates, http://www.kickthecan.info/soda-warning-labels.

Data Collection

After providing informed consent, each participant completed a brief demographic questionnaire and a 90-minute in-depth interview administered by trained bilingual study staff with ethnic and gender concordance to the participant for interviews of WIC participants to help reduce social desirability bias. In interviews, study subjects viewed up to 24 exhibits of visual aids (Table 1). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim in English or in Spanish with English translation. Study staff took notes during the interview and debriefed after each interview to ensure consensus on notes. The New York State Department of Health provided conceptual support for the study and the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center approved all study protocols. We provided $50 compensation for WIC participant and health care provider interviews. All recruitment, consent, and interview materials were available in both English and Spanish.

Analytic Approach

We began with content analysis of the transcribed interviews and notes using immersion- crystallization techniques until no new themes emerged.21 In this process, the research team reviewed all interview notes and transcriptions and met regularly to discuss the data as a group. Next, using detailed notes and audio-recordings of the research team meetings, we developed a codebook and refined it through iterative team discussions. Three research team members performed coding for further data analysis using NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). Coders double-coded 20% of transcriptions and reviewed consistency of coding to ensure consensus on data categorization, then the remainder of transcriptions were coded by individual coders. For the final stage following completion of coding, the research team met as a group to analyze the topical code reports to resolve discrepancies in interpretations and reach final theme interpretation.

RESULTS

We interviewed 9 pregnant women, 16 post-partum women, and 7 providers. All pregnant women and mothers were Hispanic/Latino, mean age was 30 years, and 72% of the mothers reported annual household income ≤ $25,000. Of the 25 interviews completed with pregnant women and mothers, 15 were conducted in Spanish and 10 were in English. The majority, 14, of the women were born in the Dominican Republic, 7 were born in the United States, 2 in Mexico, and 1 each born in El Salvador and Ecuador. Of those born outside the United States (18 total), 8 had been in the U.S. for less than 5 years, 4 between 5–9 years, and 6 for 10 or more years. Of the 7 health care providers sampled, 4 were WIC providers and 3 were physicians. The majority of the providers were female (85%), mean age was 46 years, and 43% self-identified as White/Caucasian, and all provider interviews were conducted in English.

Beverage Perceptions (Table 2)

Table 2.

Themes and Illustrative Quotes: Parental Perceptions of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Consumption During the First 1,000 Days.

| Perceptions of healthy and unhealthy beverages |

|---|

| Confusion of healthy versus unhealthy beverages for self and infant |

| “Well, for me, healthy? Organic orange juice… Apple juice too… One percent milk is healthy, it’s fat free. Healthy drinks, let me think. Oh, Malta India. I drink a lot of Malta India. the one they sell in the Dominican Republic. I also drink a chocolate drink, but it’s organic.” (Mother, infant age 4 months, Spanish) |

| “Oh My God, orange juice has so much sugar, is this homemade orange juice?” (Mother, infant age 12 months, English) |

| Barriers to avoiding sugary drinks |

| Pregnancy cravings and parent taste preferences determine household beverage purchasing |

| “When I was pregnant, I barely drank water. It was more because I was always craving sweets.” (Pregnant woman, English) |

| Perceived lack of control over child’s beverage choices |

| “[S]ometimes there are parents that don’t want their children to cry, and they want sweets. I have a friend whose daughter cries and cries. She won’t stop until she buys her something sweet.” (Mother, infant age 6 months, Spanish) |

| Low-cost and easy access of sugar-sweetened beverages |

| “It is difficult to stay away from things when it’s all you know.” (Pregnant woman, English) |

| Facilitators to avoiding sugary drinks |

| Fear of health consequences for self and infant in pregnancy |

| “My mother had a stroke at a very young age. My grandma has diabetes, and it runs on both sides of the family. So these are things that I’m trying to avoid by not drinking so much sugary stuff.” (Pregnant woman, English) |

| Parental desire to promote infant health |

| “I understand that if I start giving my son things that are low in sugar starting now, I can help prevent him from developing that in the future, because he could develop it from genetics, so he’s predisposed already.” (Mother, infant age 22 months, Spanish) |

Confusion of healthy versus unhealthy beverages for self and infant

Almost all pregnant women and mothers showed confusion about what beverages were healthy for themselves and their infants. Words used to describe healthy beverages included “organic,” “natural,” and “homemade.” Characteristics such as brand and packaging type were perceived indicators of sugary drinks, but no pregnant women or mothers stated use of nutrition facts labels to determine sugar content of beverages. Although water was considered a healthy beverage by most, some mistakenly identified beverages that contain added sugars as health- promoting. When women were shown sugar content information for various beverages, most were shocked at the potential health impacts of SSBs and high sugar content of SSBs, 100% juice, and flavored milk. Women also perceived diet and artificially sweetened beverages as less healthy than other beverages, mostly citing concern for exposure to chemicals or higher sugar content than other drinks. Among providers, most perceived parental confusion over beverage recommendations for themselves and their infants. Providers also perceived that families were confused about sugar content in different types of beverages, and which beverage types contained added sugars.

Barriers to SSB Avoidance (Table 2)

Pregnancy cravings and parent taste preferences determine household beverage purchasing

During pregnancy, most women reported cravings for sweets. They stated that these cravings drove their desire to consume SSBs and were so strong that they were impossible to overcome. Taste preferences were also a driving factor for household SSB purchases, with some parents stating that they did not like the taste of water or preferred not to drink water because it was “tasteless.” Most pregnant women and providers perceived that families want healthy beverage alternatives besides water during pregnancy.

Perceived lack of control over child’s beverage choices

Among the mothers of infants, most women perceived that infants and other children at home control the beverage consumption decision making process. Some felt that avoiding consumption of SSBs before age 5 years seemed impossible. Many also believed that parental SSB consumption influenced infant SSB consumption. Some women stated that they had a right to consume SSBs even if they did not want their infants to drink them, but also reflected on feeling guilty about drinking SSBs in front of their children. A few women thought that other families had difficulty setting limits with their children. In contrast, some providers thought that families and cultural norms – not infant/child beverage preferences – controlled beverage consumption decision-making processes. Other providers acknowledged that as a parent, it can be difficult to say no to your child but that parental role modelling is important to promote healthy beverage consumption.

Low-cost and easy access of sugar-sweetened beverages

Some pregnant women, mothers, and providers thought that the convenience and accessibility of SSBs made it challenging to avoid drinking them. Many pregnant women and mothers stated that the low-cost of SSBs encouraged consumption. Some thought that serving

water rather than sugary drinks to visitors at home was socially inappropriate. Most providers perceived that families, even in pregnancy and infancy, viewed SSB consumption as a normal part of daily life and necessary at celebrations.

Facilitators to SSB Avoidance (Table 2) and Potentially Effective Message Frames

Negative health consequences of SSB consumption motivate behavior change for pregnant women and mothers, but providers are uncertain

Messages framed around the health benefits of water consumption and SSB avoidance were well received by pregnant women, mothers, and providers, evoking feelings of happiness and healthfulness. However, messages focusing on negative health consequences of SSB consumption – such as diabetes, heart disease, or obesity – drew more attention and stronger responses than the positive messages. Pregnant women and mothers reacted with strong emotions, including shock, fear, or guilt, in response to illustrations or wording about negative health consequences of SSB consumption during pregnancy or infancy. Child health, more so than adult or personal health, was of paramount concern to mothers. One mother was particularly upset about the health consequences of SSB consumption,

“Oh my god…The brain stroke, heart attack… oh god. That‟s scary…I would want them drinking water all the time, forget the sugary drink. Oh my goodness. That‟s scary… it scares me more for my kids. Oh my god.”

Pregnant women and mothers unanimously stated that messages focused on negative health consequences for children would lead to parents changing their child‟s SSB consumption. In contrast, health care providers did not universally agree that negative health consequences were an effective message frame. One provider said,

“We have a lot of really, really young kids coming in here. I don‟t know… Diabetes may resonate with them if they‟ve got relatives with it, but I think when you‟re 18 or 19, cirrhosis of the liver is not going to come to your mind at all, unless you have a family member …I think honestly from the discussions we have with our women, …, I don‟t see this as being particularly motivational.”

Some providers felt that young families would not relate, while others thought messages about diseases were too negative and discouraging for families.

Savings opportunities and cost count, but are less important

For all participants, positive message frames emphasizing economic savings from avoidance of SSB purchases were appealing. Mothers were surprised by the amount of money and caloric intake that could be saved by drinking tap water. After viewing one message which emphasized savings from avoiding SSBs, one pregnant mother said,

“I think it‟s good the whole „it‟ll save you money‟ „cuz usually when you have kids that‟s what you look for. To save.”

However, most pregnant women and mothers were resistant to messages promoting economic savings by drinking free tap water rather than purchasing SSBs because they thought tap water was unsafe or that it tasted bad. Some pregnant women and mothers noted distrust of messages about cleanliness of water, and health care providers observed that most families in the local community prefer to buy bottled water. Thus, switching from SSBs to water was perceived as cost-savings neutral. Additionally, messages stressing cost of SSBs were not perceived as very motivating because SSBs were not viewed as expensive. Participants also stated that while it may be helpful to discuss economic savings, cost might not be high priority during pregnancy because families expect to spend more money during that time.

Families mistrust advertising done by large companies and celebrities

Most pregnant women and mothers were surprised to learn about the multi-millions of dollars companies spend to sell sugary products, and stated their dislike of companies targeting sugary drink advertising to infants and toddlers. Pregnant women and mothers strongly agreed with messages that families should not trust advertising from big companies, but were more receptive to “educational information” from government officials, such as Department of Health employees. When a celebrity image was presented, pregnant women and mothers reacted very strongly with mistrust.

The term “Big Soda” was not familiar to most pregnant women and mothers, and confused them. Positive message frames about rights to choose and access healthy beverages were not viewed as convincing by pregnant women, mothers, or health care providers. However, pregnant women and mothers preferred messages that empowered them to make their own healthy choices for their family, rather than dictate what they “should” or “should not” give their children to drink.

Promising Strategies for Healthy Beverage Messaging During the First 1,000 Days (Table 3)

Table 3.

Parent and Provider Preferences for Potentially Successful Intervention Strategies to Eliminate Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Consumption During the First 1,000 Days.

| Topic | Themes and Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Content | Clear, concrete information on sugar content empowers parents and shifts attitudes towards beverages |

| “It’s different when you say you having 10 teaspoons of sugar grape juice, orange soda.. most of the people don’t know how much sugar they’re having. So this…should be given to a lot of people.” (Mother, infant age 10 months, English) | |

| Parents crave alternatives to water and culturally relevant drinks should be included in interventions | |

| “I think that for pregnant moms, water is great, but can I get another option? How about seltzer water? Flavored seltzer water? Because you just took out a lot of options [by asking families to reduce their sugary drink intake]!” (Provider) | |

| Imagery | Images that illustrate health consequences are more impactful than words alone |

| “I think if [the images] were on the drinks no one would buy them. it reflects something that isn’t good for your health. If I saw this label on drinks I would not buy them, not even if I were crazy.” (Pregnant woman, Spanish) | |

| Relatable people sell healthy beverage messages | |

| “I want to see regular people. I see enough celebrities on TV, and regular people is [sic] more real to me. I am influenced more by regular people. Celebrities don’t look like real life. What they eat and drink in advertisements. isn’t what they eat in real life.” - (Mother, infant age 2 months, English) | |

| Modalities | Diverse modalities of message delivery are preferred |

| “Because we’re kind of stubborn, sometimes we don’t listen, and when we leave the doctor’s office, we do the diet today and the next day we don’t. But if we found them [healthy beverage messages] on every corner or at those kiosks…That would be good too.” (Pregnant woman, Spanish) | |

| “I think now it’s more about technology. I feel anything like that would work. I mean, have someone that will post videos and give them information. Tell them how they’re doing things. That will help.” (Pregnant woman, English) |

Clear, concrete information on sugar content empowers parents and shifts attitudes against acceptability of SSBs for adults and infants

Messages that included specific information on sugar content of different beverages surprised pregnant women and mothers, particularly drinks that they previously viewed as “healthy” like sports drinks and fruit drinks. Many pregnant women and mothers liked the ability to compare the amount of sugar in different drinks so they could make their own choices. Providers noted that visual aids and demonstrations showing the actual amount of sugar in different drinks were successful in their own practices. Participants had a wide range of interpretation between the frequency implied by words like “rarely” or “occasionally,” but responded well to specific numbers on frequency or volume.

Parents crave alternatives to water and culturally relevant drinks should be included in interventions

Pregnant women, mothers, and providers emphasized that interventions should focus on presenting parents with information so that they can make healthy decisions, rather than telling parents what to do. In particular, participants responded negatively to messages that told parents to “not” or “never” do something; most pregnant women and mothers said they would ignore these messages. Many stated that taste and convenience are central reasons parents choose SSBs over water, and approved of messages promoting use of water infusers and portable water bottles. Pregnant women and mothers also stated that they wanted to see culturally relevant practices and beverages, such as jugo de avena and malta india, in intervention materials.

Images that illustrate sugar content or health consequences are more impactful than words alone

Pregnant women, mothers, and providers responded more strongly and emotionally to visual imagery compared to messages that relied on words alone. Additionally, most participants believed that people were unlikely to read through lengthy materials unless the intervention was placed in an area like a waiting room, where the reader had spare time to read it.

Relatable people sell healthy beverage messages

Most participants responded favorably to relatable images, such as those of pregnant women, infants, and families. Pregnant women and mothers stated that images of pregnant mothers and infants were more impactful than those of celebrities. Providers emphasized the importance of presenting individuals of different body shapes and with racial/ethnic concordance to the targeted community.

Diverse modalities of message delivery are preferred

Most participants emphasized the need for diverse modalities of message delivery, including posters at bus stops, informational videos and brochures in wait areas of health care or WIC sites, and mobile phone delivery of beverage nutrition facts. Participants did not universally prefer one type of intervention material. Printed educational infographics, smartphone apps, interactive websites, and warning labels were each favored by different participants. Thus, multiple intervention modalities were preferred. Participants also stated a desire to see similar messages repeatedly and in varied settings, including at the point of purchase.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study of pregnant women, mothers, and health care providers, we found that most pregnant women and mothers were confused about healthy beverage recommendations during pregnancy and infancy. They reacted most strongly to messages about negative health consequences of SSB consumption for children compared to other message frames. Information about economic savings of avoiding SSB purchases and precise sugar content of specific beverages were well received but less motivational. Promising strategies for healthy beverage promotion that emerged include providing clear, concrete information on sugar content; inclusion of culturally relevant and relatable materials; and integrated use of multiple strategies and modalities to deliver straightforward messages with unambiguous visual imagery.

Our study is the first to specifically focus on development of healthy beverage messaging to promote avoidance of SSBs during the first 1,000 days of life in low-income, racial/ethnic minority families, a population at highest risk for childhood obesity. We found that many families were confused about which beverages contain added sugar, and most were shocked to learn of the amount of sugar in SSBs, 100% fruit juice, and flavored milk. Although some WIC participants may receive 100% fruit juice - which does not contain added sugars - from WIC, they do not receive SSBs or flavored milk. We do not know whether any of our interview participants received 100% fruit juice in their tailored food package. Also, we did not study a comparison group of WIC-eligible families who were not enrolled in WIC. Thus, we are unable to draw conclusions about whether 100% fruit juice included for some WIC participants may have influenced parental attitudes towards specific beverages. The relationship between SSB consumption and childhood obesity risk is strongest in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.22 This may be due in part to the fact that racial/ethnic minorities and low-income populations are specifically targeted by SSB marketing campaigns.23,24 In the United States, $866 million dollars are spent on SSB marketing, and a substantial portion of this marketing promotes infant and toddler beverages and foods.24,25

Similar to our findings, studies of families with older children found that parents approve of interventions that address concerns about child weight gain26 and emphasize nurturing children by encouraging healthy beverage consumption.26,27,26,27,25,26 In another qualitative study, college students preferred interventions containing strong educational messages with shocking images of negative health consequences, rather than textual messages, to decrease SSB consumption.28 Similarly, we found that imagery demonstrating negative health consequences of SSB consumption was perceived as most effective to decrease sugary drink consumption in pregnancy and infancy.

Although we found that pregnant women and mothers of infants unanimously preferred messages about negative health consequences of SSB consumption, providers were less enthusiastic about focusing on negative health consequences in interventions. One reason for this discrepancy may be that providers felt health messages needed to be phrased in a positive light in order to maintain a therapeutic alliance with families over time. Conversely, families interpreted these messages as informative and educational. This finding illustrates the importance of context in message delivery – factual information with strong images in a website or health promotion brochure may be well received by families, but strong wording delivered in an individual health or nutrition counseling session may be less palatable. Considering the context in crafting of messages and recommendations for limiting SSB consumption in pregnancy and infancy will require a fine balance between transparency in delivery of health facts, motivational messages to empower healthy behaviors, and avoidance of a culture of blame towards pregnant women and parents. Strong backlash may ensue if messages are perceived as insulting or impractical.29 A challenge will lie in creating context-specific interventions and recommendations to promote curbing SSB consumption while also avoiding emotions of blame, insult, and stigma.

We found that messages delivering true, concrete information about economic and caloric savings, as well as sugar content, were preferred. This may be due to the link between higher parent self-efficacy and better health outcomes and behaviors in their children.30 We also found that positive economic message frames about monetary savings from reducing SSB purchases received positive reactions. However, most participants did not believe that savings alone would motivate SSB avoidance: it needed to accompany a greater central message such as health promotion or disease prevention.

Our findings have some limitations. This study is cross-sectional, and thus not causally linked to health outcomes. However, the qualitative interviewing method allowed for in-depth exploration of beliefs, perceptions, and preferences of message frames. Our findings are drawn from a qualitative study within one low-income, Hispanic/Latino community, which limits generalizability, however these findings provide key information about potentially successful strategies to promote healthy beverage consumption in a group that is greatly burdened by childhood obesity. While social desirability bias could influence participant responses, our interviewers were trained in culturally-sensitive research techniques and were native Spanish speakers with ethnic and gender concordance to the study population, thus reducing the chances of this bias.

Our findings suggest that pregnancy and infancy are prime periods to address SSB consumption in WIC, health care, and public health settings by delivering anticipatory guidance using messages that connect SSB consumption in the first 1,000 days with future negative health consequences for children. Empowering messages with clear, concrete information about sugar content of specific beverages and strong relatable visual imagery were well received in a low- income study population. To help ameliorate the growing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparity in childhood obesity prevalence, these potentially successful strategies should be tested in future interventions to reduce SSB consumption during the first 1,000 days of life in vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Material

What’s New:

In this qualitative research, low-income Hispanic families preferred messages that1) linked sugary drink consumption in pregnancy and infancy with negative health consequences for infants and 2) used empowering tones to convey sugar content of beverages.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Connections Grants Through Healthy Eating Research Program (RWJF Grant #74198). This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001873, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, Grant Number UL1 RR024156. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH or any of the other funders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 Through 2013–2014. Jama. 2016;315(21):2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief. 2017(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity: the role of early life risk factors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazarello Paes V, Hesketh K, O’Malley C, et al. Determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in young children: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2015;16(11):903–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Fernandez-Barres S, Kleinman K, Taveras EM, Oken E. Beverage Intake During Pregnancy and Childhood Adiposity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park S, Pan L, Sherry B, Li R. The association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake during infancy with sugar-sweetened beverage intake at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2014;134 Suppl 1:S56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miles G, Siega-Riz AM. Trends in Food and Beverage Consumption Among Infants and Toddlers: 2005–2012. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajzen I The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo Baidal JA K M, K N, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage attitudes and consumption during the First 1,000 Days of Life. Am J Pub Health [In Press]. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obesity Among Public Elementary and Middle School Students In: NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene BoES, FITNESSGRAM data ed. Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review. American journal of preventive medicine. 2016;50(6):761–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez-Escamilla R, Segura-Pérez S, Lott M, on behalf of the RWJF HER Expert Panel on Best Pracices for Promoting Healthy Nutrition FP, and Weight Status for Infants and Toddlers from Birth to 24 months. Feeding Guidelines for Infants and Young Toddlers: A Responsive Parenting Approach. Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyman MB, Abrams SA, Section On Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Nutrition, Committee On Nutrition. Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NYC Department of Health. Choosing Healthy Beverages 2018; Selection of NYC DOH publically available materials on Choosing Healthy Beverages. Available at: http://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/sugary-drinks.page.

- 15.MassGeneral Hospital. First1000Days Vidscrips. [Video]. The First 1000 Days program at the MGH Chelsea and Revere HealthCare centers and DotHouse Health helps families be healthy from the beginning. The first 1000 days is the time from the start of pregnancy until a baby turns 1002 years old. Available at: https://app.vidscrip.com/user/5726cb3ba254a5897c3c420c.

- 16.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. We Can (Ways to Enhance Children’s Activity & Nutrition)! Parent Tip Sheets. 2014; https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/tools-resources/parent-tip-sheets.htm.

- 17.Howard County Unsweetened. Better Beverage Finder. 2014; https://www.betterbeveragefinder.org/.

- 18.Boston Public Health Commission. Rethink Your Drink. 2012; http://www.bphc.org/whatwedo/healthy-eating-active-living/healthy-beverages/Pages/Healthy-Beverages.aspx.

- 19.Public Health Advocates. Kick The Can: Giving the Boot to Sugary Drinks. Soda Warning Labels- California’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning Label Bill. 2018; http://www.kickthecan.info/soda-warning-labels.

- 20.G S. Doctor’s Launch A Graphic Junk Food Warning Labels Effort. 2012; Article describing the proposed health campaign by the Ontario Medical Association to include labels on sugar and fat laden food products. Available at: http://www.adstasher.com/2012/10/doctors-launch-graphic-junk-food.html.

- 21.Borkan J Immersion/Crystallization. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell LM, Wada R, Kumanyika SK. Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the U.S. media markets. Health & place. 2014;29:124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar G, Onufrak S, Zytnick D, Kingsley B, Park S. Self-reported advertising exposure to sugar-sweetened beverages among US youth. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(7):1173–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, LoDolce M, et al. Sugary Drinks FACTS 2014: Some progress but much room for improvement in marketing to youth. 2014; Report. Available at: http://www.sugarydrinkfacts.org/resources/SugaryDrinkFACTS_Report.pdf.

- 25.Harris JL, Fleming-Milici F, Frazier W, et al. Baby Food Facts 2016: Nutrition and marketing of baby and toddler food and drinks. 2016; Report. Available at: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/BabyFoodFACTS_2016_FINAL_103116.pdf.

- 26.Jordan A, Piotrowski JT, Bleakley A, Mallya G. Developing Media Interventions to Reduce Househould Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2012;640(1):118–135. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eck KM, Dinesen A, Garcia E, et al. “Your Body Feels Better When You Drink Water”: Parent and School-Age Children’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Cognitions. Nutrients. 2018;10(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Block J, Gillman MW, Linakis S, Goldman R. “If it Tastes Good, I’m Drinking It”: Qualitative Study of Beverage Consumption among College Students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(6):702–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Victor D C.D.C Defends Advice to Women on Drinking and Pregnancy. The New York Times February 5 2016;Health. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baughcum AE, Burklow KA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: a focus group study of low-income mothers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(10):1010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.