Abstract

Background and aims:

Prior studies have shown a high prevalence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, diagnoses of functional GI diseases (FGIDs), and pelvic floor symptoms associated with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS). It is unclear if Marfan Syndrome (MFS), another common hereditary non-inflammatory connective tissue disorder, is also associated these symptoms. This study evaluates the prevalence of and compares FGIDs and pelvic floor symptoms in a national cohort of EDS and MFS patients.

Methods:

A questionnaire was sent to members of local and national MFS and EDS societies. The questionnaire evaluated the presence of GI and pelvic floor symptoms and diagnoses. The presence of FGIDs was confirmed using Rome III criteria. Quality of Life (QOL) was evaluated and scored with the CDC QOL.

Key Results:

Overall, 3,934 patients completed the questionnaire, from which 1,804 reported that they had some form of EDS and 600 had MFS. 93% of patients with EDS complained of GI symptoms and qualified for at least one FGID compared to 69.8% of patients with MFS. When comparing EDS prevalence of upper and lower GI symptoms as well as FGIDs, subjects with EDS reported significantly higher prevalence of Rome III FGIDs as compared to those with MFS. IBS (57.8% vs. 27.0%, p<.001), functional dyspepsia (FD) (55.4% vs. 25.0%, p<.001), postprandial distress (49.6% vs. 21.7%, p<.001), heartburn (33.1% vs. 16.8%, p<.001), dysphagia (28.5% vs. 18.3%, p<.001), aerophagia (24.7% vs. 12.3%, p<.001), and nausea (24.7% vs. 7.2%, p<.001) were all significantly greater in the EDS population compared to MFS population. The prevalence of FGIDs was similar across subtypes of EDS. In general, participants with EDS were more likely to have nearly all pelvic floor symptoms as compared to participants with MFS.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of FGIDs and pelvic floor symptoms in EDS is higher than that found in MFS. The prevalence of FGIDs were similar across EDS subtypes. This study supports the mounting evidence for FGIDs in those with connective tissue diseases, but more specifically, in EDS.

Keywords: Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, functional GI disorders, functional dyspepsia, joint hypermobility syndrome, Marfan Syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome

Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal diseases (FGIDs) are common reasons for consultation to the GI clinic and may represent nearly 40% of clinic visits1. It has been postulated that patients with common, chronic gastrointestinal manifestations of nausea, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, altered bowel habits with underlying connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers Danlos (EDS) may represent a unique phenotype of those with FGIDs2. A number of studies have revealed an increase in FGIDs in EDS3–8. In a retrospective study in a large tertiary care referral center, EDS was associated with increased prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (27.5%) compared to age-matched healthy controls, particularly in the EDS-hypermobility (EDS-HT) subpopulation4. Dyspepsia (particularly post-prandial fullness) and heartburn were more common in EDS-HT subjects compared to non-EDS-HT subjects presenting to a tertiary GI clinic9. In a cross-sectional study of university age students, subjects with EDS-HT where more likely than healthy controls to suffer from postprandial fullness (34% vs. 15.9%), early satiety (32% vs. 17%) as well as autonomic and somatic complaints6. In another study, patients with EDS-HT were more likely to complain of heartburn, water brash, and postprandial fullness compared to age-matched controls9.

EDS is a multi-systemic disorder, with common cutaneous, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular manifestations. The true prevalence of connective tissue diseases in the population is unclear, however, EDS is thought to affect 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 500010, 11. A small proportion of affected patients suffer from a deficiency in tenascin-x, an extracellular glycoprotein involved in collagen structure12. Without a definitive genetic test available, diagnosis is typically made through Beighton criteria, measuring joint laxity and features of hypermobility13. There is a higher prevalence of EDS amongst women by diagnostic clinical criteria14. In the GI clinic, a recent study revealed 33% of subjects presenting with common GI symptoms suffered from undiagnosed hypermobility by, consistent with a diagnosis of EDS-HT9. However, less is known about the association of GI symptoms with Marfan syndrome (MFS). A genetic mutation in the fibrillin-1 gene, which produces fibrillin, a major component of extracellular microfibrils is known to cause MFS, which leads to wide-ranging elastic and non-elastic connective tissue abnormalities throughout the body15.

Due to its effects on connective tissue, people with EDS and MFS may be predisposed to pelvic organ prolapse16 as well as urinary and fecal incontinence17. However, little is known about the incidence of pelvic floor symptoms in this cohort. For example, a study of 148 EDS subjects from the Hypermobility Syndrome Association in 2009 were more than twice as likely to complain of urinary and fecal incontinence compared to the estimated national prevalence in the general population17. Likewise, a small case series of twelve women with MFS and eight women with EDS from two urban hospitals found a higher prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse compared to the reported national prevalence16.

The majority of these studies have been conducted in secondary5, 6 and tertiary settings4, 9, are and thus, may not be representative of the general EDS population. The aim of this study is to (1) Describe the prevalence of FGIDs and pelvic floor disorders in a large, general, adult population of EDS and MFS patients and (2) Compare the prevalence of these disorders and symptoms in MFS and EDS patients.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

This is an observational cross-sectional survey study and was approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Individuals were contacted through electronic mailing lists of members by local and national Marfan Syndrome and EDS societies. These groups were: the Massachusetts Chapter of the National Marfan Foundation, National Marfan Foundation, the EDS New England/Massachusetts Support Group, Ehlers-Danlos National Foundation (EDNF), EDS Awareness.com, and EDSr’s United. CEDSA (Center For Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Alliance) and the EDS CARES Network were contacted but did not respond.

ADMINISTRATION OF STUDY

Respondents completed an anonymous web-based standardized questionnaire between October 2014 and January 2015. Respondents received no incentive to complete the questionnaire. All prospective members received an email reminder after the initial email at weeks 1, 2, and 4, and once more after the survey was briefly closed for interim analysis.

STUDY QUESTIONS AND DEFINITIONS

Upon enrollment in the survey, subjects were queried on demographics, type of connective tissue disease, method of diagnosis, and comorbid symptoms and conditions. In addition, we used previously validated questionnaires using Rome III criteria to determine the diagnosis of FGIDs11. We acknowledge that the Rome criteria identifies particular FGIDs, such as functional heartburn by symptom criteria as well as medical evaluation with endoscopy and/or esophageal pH monitoring. This information was not requested from the participants and is beyond the scope of the questionnaires. In these instances, symptoms were identified as the symptom of “heartburn” as opposed to the FGID diagnosis of functional heartburn. The Rome III Diagnostic Questionnaire modules for all FGIDs were then scored. For pelvic floor symptoms, common pelvic floor diseases and endometriosis were identified with questions such as: “Have you ever had urinary incontinence (leaking of urine)?”, “Have you ever had prolapse of your rectum (lining of your rectum coming out)?” and “Have you ever had endometriosis (a painful disorder in which tissue that normally lines the inside of your uterus called the endometrium grows outside your uterus)?”

To determine the effect of GI symptoms on quality of life, subjects were given a set of previously validated CDC QOL 4 questions18. From 2000 to 2012, the CDC HRQOL– 4 has been in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for persons aged 12 and older. The number of unhealthy days was calculated using the sum of the days to the question “(1) Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good? (2) Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good? (4) During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation? CDC HRQOL-4 is used to create an Unhealthy Days Index, calculated as the sum of the two items being truncated at 30 days. Subjects were asked “what is the major impairment or health problem that limits your activity?” and subsequently asked “Would you say your GI problem is more limiting than what you answered above?” GI Limitation of QOL was classified as affirmative, if the response to this question was “yes.”

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Univariate analyses were performed to assess the association between diagnosis (MFS and EDS (all subtypes combined)) and the variables of interest. Fisher’s Exact Tests were used for categorical variables, and independent samples t-tests were used for continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 24 software.

Results

A total of 3,934 subjects provided questionnaire data. However, 1,230 persons were excluded from the analysis because they dropped out of the survey before completing it. Another 41 persons were excluded because they did not provide answers to the key questions used to classify individuals by diagnosis. In addition, 39 persons who reported that their age was less than 18 were also excluded, leaving 2,624 respondents. Of these, 1,804 reported that they had some form of EDS (“classic” or type 1 and 2 [260], EDS-HT or type 3 [1325], and vascular or type 4 [58], and unknown type [161]), 600 had MFS, 138 had other connective tissue diseases (Osteogenesis imperfecta [1], Loetz-Dietz Syndrome [28], undefined connective tissue disorder [109]). In addition 82 persons reported that they were spouses of patients. The 82 spouses and 138 subjects with other connective tissue diseases were excluded from analysis due to the small numbers, leaving a final sample size of 2,404.

Demographics

The participants were predominantly white, with no significant difference between the EDS and MFS groups (91.4% vs. 89.2%, p=.10). Although both groups were predominantly female, the EDS group had a much higher proportion of women than the MFS group (93.7% vs. 61.0%, p<.001). The EDS group was significantly younger than the MFS group (40.9 [SD=13.2] vs. 44.5 [SD=14.2], p<.001); however, the absolute difference between the groups (3.6 years) was relatively small. The sample was relatively well-educated, and there was no significant difference between the EDS and MFS groups in the proportion who had at least some college (90.5% vs. 88.8%, p=.27). The majority of the participants reported that they were diagnosed clinically by a physician (80.3%), except for participants with vascular EDS, 58.6% of whom reported that they were diagnosed by a physician who used genetic testing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics

| EDS Overall (N=1804) (%) |

Marfans (N=600) (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | ||

| All participants | 40.9 (13.2) | 44.5 (14.2) |

| Range | 18–88 | 18–81 |

| Men only | 42.3 (14.2) | 44.2 (14.5) |

| Range | 19–74 | 18–81 |

| Women only | 40.9 (13.2) | 44.6 (14.0) |

| Range | 18–88 | 18–79 |

| Gender (%) | ||

| Male | 110 (6.1) | 234 (39.0) |

| Female | 1691 (93.7) | 366 (61.0) |

| Not reported | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 1649 (91.4) | 535 (89.2) |

| Black | 7 (0.4) | 11 (1.8) |

| Asian | 6 (0.3) | 12 (2.0) |

| American Indian | 11 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) |

| Hispanic | 29 (1.6) | 17 (2.8) |

| Pacific Islander | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) |

| Two or more races | 85 (4.7) | 17 (2.8) |

| Other | 11 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| Not reported | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Highest Level of Education (%) | ||

| Some high school | 33 (1.8) | 14 (2.3) |

| High school graduate | 135 (7.5) | 52 (8.7) |

| Some college | 472 (26.2) | 133 (22.2) |

| College graduate | 616 (34.1) | 219 (36.5) |

| Graduate degree | 544 (30.2) | 181 (30.2) |

| Missing | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Diagnosis (%) | ||

| Genetic testing outside MD office | 27 (1.5) | 18 (3.0) |

| Genetic testing by MD | 203 (11.3) | 140 (23.3) |

| Clinically by MD | 1515 (84.0) | 415 (69.2) |

| Not applicable | 59 (3.3) | 26 (4.3) |

| Not reported | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGIDs)

In general, EDS subjects reported a high prevalence of upper and lower GI symptoms (Table 2). The prevalence of IBS was 57.8% in the EDS group. 13.4% were classified as IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and 11.8% as IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D). 55.4% of those with EDS qualified for functional dyspepsia (FD), predominantly of the postprandial distress type at 49.6%. Other common FGIDs include heartburn (33.1%), dysphagia (28.5%), nausea (24.7%), aerophagia (24.7%), and cyclical vomiting syndrome (CVS) (20.6%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of FGIDs in EDS and MFS Comparison of prevalence of functional GI diseases (FGIDs) in EDS and MFS by total (both men and women), men only, and women only.

| EDS Total N=1804 |

MFS Total N=600 |

P value |

EDS Women |

MFS Women |

P value | EDS Men |

MFS Men |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 (%) | 600 (%) | 1691 (%) | 366 (%) | 110 (%) | 234 (%) | ||||

| IBS | 1042 (57.8) | 162 (27.0) | <.001 | 998 (59.0) | 38 (33.3) | <.001 | 42 (38.2) | 40 (17.1) | <.001 |

| IBS-C | 242 (13.4) | 45 (7.5) | <.001 | 236 (14.0) | 38 (10.4) | 0.075 | 6 (5.5) | 7 (3.) | 0.36 |

| IBS-D | 212 (11.8) | 33 (5.5) | <.001 | 200 (11.8) | 26 (7.1) | 0.007 | 11 (10.0) | 7 (3.0) | 0.009 |

| Dyspepsia | 999 (55.4) | 150 (25.0) | <.001 | 952 (56.3) | 108 (29.5) | <.001 | 44 (40.0) | 42 (17.9) | <.001 |

| Postprandial Distress | 895 (49.6) | 130 (21.7) | <.001 | 854 (50.4) | 98 (26.8) | <.001 | 38 (34.5) | 32 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Epigastric pain | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | .578 | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Functional Constipation | 132 (7.3) | 32 (5.3) | 0.112 | 128 (7.6) | 25 (6.8) | 0.742 | 4 (3.6) | 7 (3.0) | 0.749 |

| Functional Diarrhea | 12 (0.7) | 9 (1.5) | 0.074 | 11 (0.7) | 6 (1.6) | 0.101 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| Heartburn | 598 (33.1) | 101 (16.8) | <.001 | 557 (32.9) | 65 (17.8) | <.001 | 40 (36.4) | 36 (15.4) | <.001 |

| Chest Pain | 38 (2.1) | 6 (1.0) | .111 | 37 (2.2) | 6 (1.6) | 0.686 | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.32 |

| Dysphagia | 515 (28.5) | 110 (18.3) | <.001 | 489 (28.9) | 63 (17.2) | <.001 | 24 (21.8) | 47 (20.1) | 0.775 |

| Globus | 41 (2.3) | 7 (1.2) | .128 | 40 (2.4) | 4 (1.1) | 0.162 | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| Cyclical vomiting | 372 (20.6) | 60 (10.0) | <.001 | 356 (21.1) | 39 (10.7) | <.001 | 15 (13.6) | 21 (9.0) | 0.191 |

| Rumination | 92 (5.1) | 10 (1.7) | <.001 | 88 (5.2) | 6 (1.6) | 0.002 | 4 (3.6) | 4 (1.7) | 0.273 |

| Bloating | 224 (12.4) | 98 (16.3) | .018 | 212 (12.5) | 69 (18.9) | 0.002 | 12 (10.8) | 29 (12.4) | 0.859 |

| Aerophagia | 445 (24.7) | 74 (12.3) | <.001 | 419 (24.8) | 47 (12.8) | <.001 | 25 (22.7) | 27 (11.5) | 0.009 |

| Chronic Idiopathic Nausea | 445 (24.7) | 43 (7.2) | <.001 | 426 (25.2) | 38 (10.4) | <.001 | 18 (16.4) | 5 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Functional Vomiting | 73 (4.0) | 9 (1.5) | .002 | 70 (4.1) | 8 (2.2) | 0.095 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0.241 |

| Functional GB SOD d/o | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1.000 | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| GI Limitation on QOL | 347 (19.2) | 62 (10.3) | <.001 | 320 (18.9) | 37 (10.1) | <.001 | 26 (23.6) | 25 (10.7) | 0.003 |

Prevalence of FGIDs in EDS subtypes

When comparing the most common EDS, EDS-HT to other subtypes of EDS, the prevalence of GI symptoms and FGIDs are similar. Likewise, when FGIDs in vascular EDS were compared to other subtypes, there was no significant difference (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage prevalence of functional GI diseases (FGIDs) in EDS-hypermobility (EDS-HT) compared to EDS all others (subtypes including classic, vascular, and unclassified).

| FGID | EDS-HT % | EDS all others % | Fisher’s Exact p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerophagia | 24.1 | 26.3 | .35 |

| Bloating | p12.8 | 11.5 | .52 |

| Chest pain | 2.2 | 1.9 | .85 |

| Chronic idiopathic nausea | 24.5 | 25.3 | .76 |

| Functional constipation | 7.5 | 6.7 | .61 |

| Cyclical vomiting | 20.5 | 21.1 | .79 |

| Diarrhea | 0.5 | 1.3 | .09 |

| Functional dyspepsia | 55.2 | 55.9 | .79 |

| Functional Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction | 0.2 | 0.4 | .29 |

| Vomiting | 3.5 | 5.4 | .08 |

| Globus | 2.3 | 2.1 | .86 |

| Heartburn | 31.8 | 37.0 | .04 |

| IBS | 58.4 | 55.9 | .36 |

| Rumination | 4.8 | 6.1 | .28 |

| Dysphagia | 28.9 | 27.6 | .60 |

| Any FGID above | 93.7 | 87.5% | <.001 |

FGIDs in EDS compared to MFS

When comparing EDS prevalence of upper and lower GI symptoms as well as FGIDs, subjects with EDS reported significantly higher prevalence of Rome III FGIDs as compared to those with MFS. IBS (57.8% vs. 27.0%, p<.001), FD (55.4% vs. 25.0%, p<.001), postprandial distress (49.6% vs. 21.7%, p<.001), heartburn (33.1% vs. 16.8%, p<.001), dysphagia (28.5% vs. 18.3%, p<.001), aerophagia (24.7% vs. 12.3%, p<.001), and nausea (24.7% vs. 7.2%, p<.001) were all significantly greater in the EDS population compared to MFS population. In contrast to this general trend, the MFS group reported a significantly higher rate of bloating as compared to the EDS group (16.3% vs. 12.4%, p=.018).

Gender Differences of FGIDs in EDS and MFS

When comparing women to men with EDS, women suffered from all FGIDs more commonly than men (Table 2). FD (56.3% vs. 29.5%, p=.001), postprandial distress (50.5% vs. 26.8%, p=.002), and nausea (25.2% vs. 16.4%, p=.040) were more common in women significantly more than men with EDS. Similarly, women with MFS suffered from all FGIDs more commonly than men with MFS including IBS.

Quality of Life and GI Limitation on QOL

Participants with EDS reported a significantly higher number of unhealthy physical days compared to participants with MFS (17.6 days ± 10.22 days vs. 8.86 ± 9.92, p<0.001). Participants with EDS also reported a significantly higher number of unhealthy mental health days compared to participants with MFS (11.14 days ± 10.42 vs. 7.27 ± 9.57, p<0.001). The unhealthy days index was significantly higher in the individuals with EDS compared to the individuals with MFS (22.32 days ± 9.96 vs. 13.27 ± 11.71, p<0.001). When restricted to those participants with EDS and MFS who responded affirmatively to GI limitation, the number of unhealthy physical days was significantly higher in the EDS group compared to MFS (17.69 days ± 9.73 vs. 10.37 days ± 9.55, p<0.001), but number of unhealthy mental health days was not (10.38 days ± 10.16 vs. 8.14 ± 8.92, p=0.12).

Pelvic Floor Symptoms and Diagnoses

Frequencies of pelvic floor symptoms are shown in Table 4. In general, EDS subjects reported a high prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms. The most common pelvic floor symptoms included incomplete bowel evacuation (83.3%), incomplete urinary voiding (75.3%), and symptoms suggestive of a functional defecation disorder (60.2%). The prevalence of bowel or bladder incontinence in the examined population was 19.2% and 60%, respectively.

Table 4:

Pelvic Floor Symptoms and Diagnoses in EDS and MFS

| EDS | Marfans | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1804 (%) | 600 (%) | |

| Hemorrhoids | 1068 (59.2) | 255 (42.5) | <.001 |

| Anal Fissure | 860 (47.7) | 123 (20.5) | <.001 |

| Rectal prolapse | 296 (16.4) | 36 (6.0) | <.001 |

| <50 yo | 192 (10.6) | 28 (4.7) | <.001 |

| 50–69 yo | 94 (5.2) | 7 (1.2) | <.001 |

| >70 yo | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | .688 |

| Fecal incontinence | 346 (19.2) | 67 (11.2) | <.001 |

| Incomplete evacuation | 1503 (83.3) | 395 (65.8) | <.001 |

| Suggestive of Functional Defecation d/o | 1086 (60.2) | 207 (34.5) | <.001 |

| Chronic Proctalgia | 258 (14.3) | 32 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Proctalgia Fugax | 446 (24.7) | 88 (14.7) | <.001 |

| Urinary incontinence | 1082 (60.0) | 233 (38.8) | <.001 |

| Incomplete urinary voiding | 1358 (75.3) | 303 (50.5) | <.001 |

| Hysterectomy (for bleeding) | 244 (13.5) | 49 (8.2) | <.001 |

| <50 yo | 108 (6.0) | 19 (3.2) | .006 |

| 50–69 yo | 132 (7.3) | 28 (4.7) | .023 |

| 70+ yo | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | .643 |

| Uterine Prolapse | 236 (13.1) | 35 (5.8) | <.001 |

| Endometriosis | 434 (24.1) | 61 (10.2) | <.001 |

| Rectocele | 258 (14.3) | 22 (3.7) | <.001 |

In general, participants with EDS were more likely to have nearly all pelvic floor symptoms as compared to participants with MFS. In particular, incomplete evacuation (83.3% vs. 65.8%, p<.001), incomplete voiding (75.3% vs. 50.5%, p<.001), urinary incontinence (60.0% vs. 38.8%, p<.001), hemorrhoids (59.2% vs. 42.5%, p<.001), and fecal incontinence (19.2% vs. 11.2%, p<.001) were significantly greater in the EDS compared to MFS group. Women with EDS were more likely to have urinary incontinence and incomplete urinary voiding, anal blockage, incomplete evacuation, and symptoms suggestive of obstructive defecation as compared to women with MFS.

We then examined the effect of age in women on pelvic floor symptoms. Using point by biserial correlations, older age was positively associated with several pelvic floor symptoms, specifically rectal prolapse, urinary incontinence, endometriosis, rectocele and uterine prolapse. In addition, older age was positively associated by Spearman rank-order correlations with severity of fecal incontinence (rs = .15, p<.001) and negatively associated with incomplete evacuation (rs = - .11, p<.001).

Additionally women with EDS compared to women with MFS reported a much higher rate of endometriosis (24.1% vs. 10.1%).

When compared to men with MFS, men with EDS were significantly more likely to have urinary incontinence (33.6% vs. 20.6%), incomplete voiding of urine (61.8% vs. 45.7%), anal blockage (29.1% vs 18.4%), incomplete evacuation (70.0% vs 56.8%) and symptoms suggestive of functional defecation (47.3% vs 26.5%) (supplementary table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JCG/A477 ).

Discussion

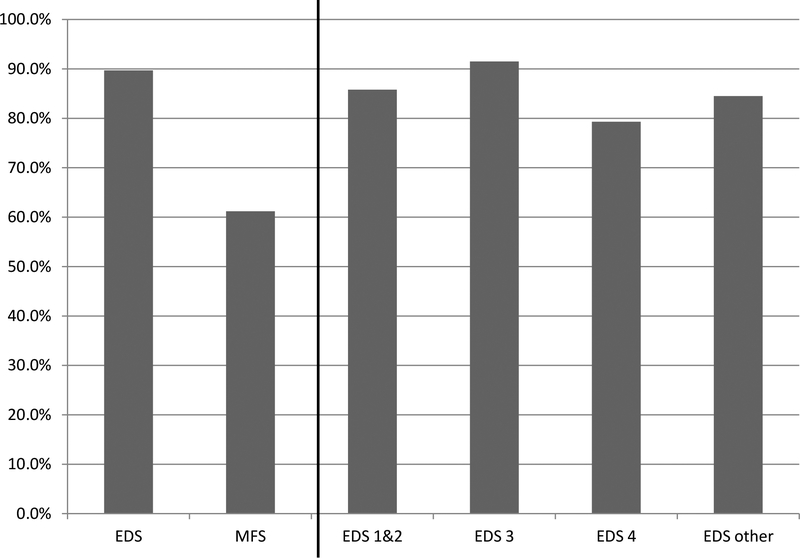

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of EDS, including four major subtypes, and MFS assessed for FGIDs and pelvic floor symptoms. We found a significantly greater prevalence for many FGIDs in EDS compared to MFS. 93% of patients with EDS complained of GI symptoms and qualified for at least one FGIDs compared to 69.8% of patients with MFS (Figure 1). In EDS the prevalence of IBS and functional dyspepsia (postprandial distress) were 57.8% and 55.4% respectively, which is nearly two times the frequency as in the MFS patients. Furthermore, pelvic floor symptoms such as urinary and fecal incontinence were very common at 19.2% and 75.3%, respectively. Similarly to FGIDs, pelvic floor symptoms were significantly higher in subjects with EDS compared to subjects with MFS. And finally, impairment on quality of life, indicated by the number of unhealthy physical and mental days, was significantly higher in the EDS population compared to those with MFS.

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients with EDS, EDS subtypes, and MFS qualifying for > 1 Functional GI Disease (FGID)

The known prevalence rate in the general population is thought to be approximately 10–25% in IBS19, and 23–25.8% in FD20. Similar to prior studies, the prevalence of IBS and FD in EDS patients presenting to GI clinics3, 8 was significantly higher than and nearly double the accepted national averages. However, unlike these prior studies4, 9, our study shows that FGIDs did not occur more frequently in the EDS-HT subtype compared to other subtypes. The prevalence of most FGIDs in MFS, however, were similar to known national averages of non-EDS patients. Compared to studies evaluating prior undiagnosed joint hypermobility (JHM) presenting to GI clinic5, our study similarly found a strong prevalence of upper GI FGIDs, specifically functional dyspepsia (especially PPD). Furthermore, symptoms of chronic vomiting and nausea were similarly high5.

Pelvic floor dysfunction was also highly prevalent in both subjects with MFS or EDS. National prevalence rates of urinary incontinence have been estimated to be approximately 49.5% in women and 15.1% in men21, and fecal incontinence in approximately 8.8% in women and 7.7% in men22; in comparison, patients with EDS revealed higher rates of urinary incontinence at 60% as well as fecal incontinence (19.2%). In this study, we show that the prevalence of these pelvic floor symptoms are more common in patients with EDS and MFS than reported in the general population, but all pelvic floor complaints were significantly higher in female and male EDS subjects compared to female and male MFS subjects. A previous association between hypermobility and pelvic floor dysfunction has previously been shown16, 23. The common etiology may be secondary to connective tissue and the interplay with the pelvic floor.

Endometriosis was interestingly higher in prevalence in the EDS compared to MFS. Previous studies have shown that endometriosis requires cellular adhesion, proliferation, and invasion of the primary endometrial tissue. We postulate that the abnormal collagen structure and function evident in EDS, under the setting of stressors such as hypoxia, may lead to an altered, compromised extracellular matrix, through which endometrial cells may more easily adhere and invade, thus leading to increased endometriosis in this population.24

Despite the strength of the response rate in this population, the study has several limitations. While the absolute number of respondents is large, the number of unique individuals available to answer the questionnaire is unknown due to the large overlap of members in the participating societies. Our study analysis lacks a control group. However, EDS and MFS FGIDs appear to be more common compared to the national prevalence rates. Our population was predominantly composed of women, whose responses may skew prevalence of FGIDs and pelvic floor disorders as this is more common in women compared to men. Ethnically, this is a predominantly white population. Additionally, the Rome III criteria for diagnosis of FGIDs is limited by lack of specificity. Due to the nature of a survey study, these were self-reported diagnoses of connective tissue disorders as well as self-reported symptomatology without information on previous work up, comorbid conditions, or concomitant medications. As with all surveys, there is a potential for selection bias, in that potential subjects who completed the survey may be disproportionately affected by GI symptoms compared to those who did not fill out the survey. However, the bias would be equally present in both the EDS and MFS groups, yet the EDS groups show significantly higher functional GI diseases compared to MFS. Despite these potential limitations, this remains one of the largest cohort of subjects with connective tissue diseases responding to GI symptom and diagnosis questionnaires.

This study supports the mounting evidence for FGIDs in those with connective tissue diseases, but more specifically, in EDS. The mechanism of action for this relationship is still unclear. As of this paper, the potential role of dysfunctional connective tissue and its effect on mechanical and motility characteristics of the GI tract still remains unknown. There is an association of EDS with autonomic dysfunction and postural orthostatic hypotension (POTS)25. A possible connection between the enteric nervous system and changes to motility and visceral sensation may lead to these common symptoms that we have classified as FGIDs. Clinically, the EDS population may be important to identify due to the potential implications of treatment and outcomes as unique pathophysiologic mechanisms are explored.

In summary, this is the largest non-patient population with EDS and MFS who have been assessed for FGIDs and pelvic floor symptoms. While the prevalence in MFS of some FGIDs is high, most are similar to the prevalence found in the general US population. Both men and women with EDS were significantly more likely to suffer from FGIDs compared to men and women with MFS and the prevalence was higher than in the general population. Pelvic floor symptoms were common in both men and women with EDS and MFS. However overall, it was more common in women and men with EDS compared to MFS.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. Comparison of prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms and diagnoses in EDS and MFS by total (both men and women), women only, and men only.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AT00857303 and T32DK007760

Abbreviations:

- CVS

cyclical vomiting syndrome

- EDS

Ehlers Danlos Syndrome

- EDS-HT

Ehlers Danlos Syndrome – hypermobility

- MFS

Marfan Syndrome

- FD

Functional Dyspepsia

- FGIDs

Functional GI Diseases

- IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- QOL

quality of life

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose

Writing assistance: None

References

- 1.Switz DM. What the gastroenterologist does all day. A survey of a state society’s practice. Gastroenterology 1976;70:1048–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fikree A, Aziz Q, Grahame R. Joint hypermobility syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2013;39:419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitoun JD, Lefevre JH, de Parades V, et al. Functional digestive symptoms and quality of life in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: results of a national cohort study on 134 patients. PLoS One 2013;8:e80321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson AD, Mouchli MA, Valentin N, et al. Ehlers Danlos syndrome and gastrointestinal manifestations: a 20-year experience at Mayo Clinic. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:1657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fikree A, Aktar R, Grahame R, et al. Functional gastrointestinal disorders are associated with the joint hypermobility syndrome in secondary care: a case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fikree A, Aktar R, Morris JK, et al. The association between Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-hypermobility type and gastrointestinal symptoms in university students: a cross-sectional study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farmer AD, Fikree A, Aziz Q. Addressing the confounding role of joint hypermobility syndrome and gastrointestinal involvement in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res 2014;24:157–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarate N, Farmer AD, Grahame R, et al. Unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms and joint hypermobility: is connective tissue the missing link? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:252–e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fikree A, Grahame R, Aktar R, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Undiagnosed Joint Hypermobility Syndrome in Patients With Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2014;12:1680–1687.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes DF, Watson RB, Steinmann B, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VIIB. Morphology of type I collagen fibrils formed in vivo and in vitro is determined by the conformation of the retained N-propeptide. J Biol Chem 1993;268:15758–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NIH. Ehlers Danlos. Genetics Home Reference (online consumer guide). National Library of Medicine, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017;175:8–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grahame R, Bird HA, Child A. The revised (Brighton 1998) criteria for the diagnosis of benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS). J Rheumatol 2000;27:1777–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castori M, Camerota F, Celletti C, et al. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type and the excess of affected females: possible mechanisms and perspectives. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152a:2406–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genetic Home Reference Marfans Syndrome. 2017.

- 16.Carley ME, Schaffer J. Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women with Marfan or Ehlers Danlos syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:1021–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arunkalaivanan AS, Morrison A, Jha S, et al. Prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence among female members of the Hypermobility Syndrome Association (HMSA). J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;29:126–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Measuring CfDCaPC, quality hdPaoh-r, Prevention. olACfDCa.

- 19.Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1365–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1259–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markland AD, Richter HE, Fwu CW, et al. Prevalence and trends of urinary incontinence in adults in the United States, 2001 to 2008. J Urol 2011;186:589–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in US adults: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology 2009;137:512–7, 517.e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammers K, Lince SL, Spath MA, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse and collagen-associated disorders. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:313–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi M, Nasu K, Tsuno A, et al. Attachment to extracellular matrices is enhanced in human endometriotic stromal cells: a possible mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;155:85–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallman D, Weinberg J, Hohler AD. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: a relationship study. J Neurol Sci 2014;340:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Comparison of prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms and diagnoses in EDS and MFS by total (both men and women), women only, and men only.