Abstract

The ability to generalize from and distinguish between aversive memories and novel experiences is critical to survival. Previous research has revealed mechanisms underlying generalization of threat-conditioned defensive responses, but little is known about generalization of episodic memory for threatening events. Here we tested if aversive learning influences generalization of episodic memory for threatening events in human adults. Subjects underwent Pavlovian threat-conditioning in which objects from one category were paired with a shock and objects from a different category were unpaired. The next day, subjects underwent a recognition memory test that included old, highly similar, and entirely novel items from the shock-paired and shock-unpaired object categories. Results showed that items highly similar to those from the object category previously paired with shock were mistaken for old items more often than items from the shock-unpaired category. This finding indicates that threat learning promotes generalization of episodic memory, and is consistent with the idea that threat generalization is an active process that may be adaptive for avoiding a myriad of potential threats following an emotional experience. Enhanced generalization of aversive episodic memories may be maladaptive, however, when old threat memories are inappropriately reactivated in harmless situations, exemplified in a number of stress- and anxiety-related disorders.

Keywords: generalization, fear conditioning, episodic memory

Pavlovian threat (“fear”) conditioning is an adaptive learning process that enables animals to anticipate and avoid potential threat. During threat conditioning, intrinsically neutral stimuli gain emotional significance through pairing with an aversive event (LeDoux, 2014; Maren, 2001; Phelps & LeDoux, 2005). Importantly, in an ever-changing environment, the exact same stimulus is rarely encountered over repeated experiences, and organisms are instead confronted by ambiguous cues that bear a resemblance to previous signals of threat. One way to resolve whether to react defensively to these ambiguous threat cues is through processes that bias behavior toward generalization or discrimination. Understanding how animals balance the tradeoff between threat generalization and discrimination is a crucial question that has warranted considerable empirical attention from studies of threat conditioning (Dunsmoor & Paz, 2015). Notably, research on stimulus generalization tend to limit investigation to the generalization of conditioned responses from a particular stimulus or stimuli to other stimuli that vary in perceptual or conceptual similarity (Dunsmoor, Kroes, Braren, & Phelps, 2017; Dunsmoor & LaBar, 2013; Dunsmoor & Murphy, 2014; Haddad, Xu, Raeder, & Lau, 2013; Holt et al., 2014; Kroes, Dunsmoor, Lin, Evans, & Phelps, 2017; Lissek et al., 2008, 2014; Norrholm et al., 2014; Schechtman, Laufer, & Paz, 2010). Nevertheless, episodic memories are also formed during threatening experiences and likely contribute to identification (or misidentification) of similar threats in the future. What effect, if any, threat conditioning has on the specificity of an emotional episodic memory has received little attention. This question is important because episodic memories may be altered in pathological anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and contribute to overgeneralization of unwanted and maladaptive behavior (Besnard & Sahay, 2016; Duits et al., 2015; Ehlers et al., 2002; Kheirbek, Klemenhagen, Sahay, & Hen, 2012; Lissek et al., 2005). Here, we ask whether Pavlovian threat conditioning influences generalization of episodic memories, measured as a bias to explicitly confuse new items that are highly similar to a learned threat as having been encountered in the past.

Human memory research has long established that emotional experiences are remembered more often and with more vividness than neutral experiences (Cahill et al., 1996; Cahill & McGaugh, 1995; Christianson & Loftus, 1987, 1991). We have recently extended the emotional enhancement of episodic memory to threat conditioning, showing that long-term item recognition memory is enhanced for neutral items from an object category that have acquired emotional salience through association with an aversive electrical shock (Dunsmoor, Martin, & LaBar, 2012; Dunsmoor, Murty, Davachi, & Phelps, 2015). Importantly, although we may easily recognize emotional events and remember the gist of emotional episodic experiences, the precision of our memory to accurately remember the details of emotional events can be limited (Adolphs, Denburg, & Tranel, 2001; Adolphs, Tranel, & Buchanan, 2005; Kensinger, 2009; LaBar & Cabeza, 2006; Leal, Tighe, & Yassa, 2014; Mather & Sutherland, 2011). This is also true in threat conditioning, where memory precision of a conditioned stimulus or context gives way to more gist like representations, leading to increases in threat response generalization over time (Dunsmoor, Otto, & Phelps, 2017; Wiltgen & Silva, 2007). Understanding how the precision of episodic memory is affected by threat conditioning could be relevant to elucidate the mechanisms underlying anxiety- and stress-related disorders, where impairment in accurately discriminating between traumatic memories and new information has been suggested to result in overgeneralization of threat-related responses (Besnard & Sahay, 2016; Kheirbek et al., 2012).

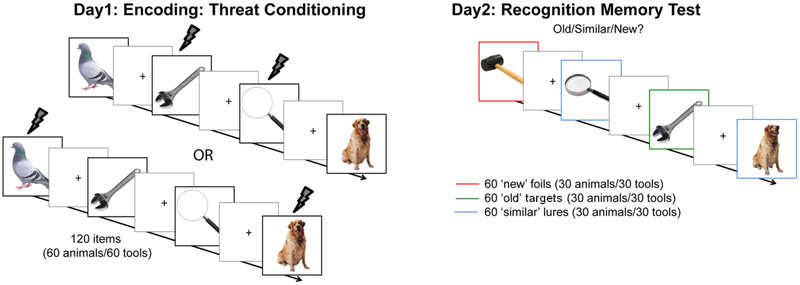

The objective of the present study was to investigate the effect of threat conditioning on the generalization of long-term episodic memory using a memory paradigm that taxes episodic memory for the details of previously encoded items. Participants completed two experimental sessions that occurred 24 hours apart (Fig 1). Encoding, on day 1, consisted of a trial-unique (i.e., stimuli are non-repeating) Pavlovian threat-conditioning task during which skin conductance responses (SCRs) and shock expectancy were measured to confirm acquisition of threat conditioning (Dunsmoor et al., 2012). Participants were conditioned to items from a specific category associated with an aversive shock (CS+; i.e., animals or tools) or no shock (CS−; i.e., tools or animals, counterbalanced between subjects). Day 2 consisted of a surprise item recognition memory test, where old target items encoded during threat conditioning, similar lures and novel foils were presented to participants (Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007; Stark, Stevenson, Wu, Rutledge, & Stark, 2015). Based on our prior findings (Dunsmoor et al., 2012, 2015), we predicted that threat conditioning would enhance recognition memory for items from the conditioned category, i.e. correctly identifying target items from the CS+ category as old more often than target items from the CS− category. However, we also predicted that threat conditioning would promote generalization of episodic memory for the conditioned category, operationalized as misidentification of similar lures as old relative to misidentifying novel foils as old (Ally, Hussey, Ko, & Molitor, 2013). In addition, we also calculated a discrimination score operationalized as correctly identifying similar lures as similar relative to misidentifying novel foils as similar (Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007). These generalization and discrimination measures have often been taken as a proxy for presumed underlying pattern completion and separation processes (Ally et al., 2013; Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007; Yassa & Stark, 2011). In the field of memory, the operation of pattern completion, refers to the reactivation of a stored memory representation based on partial input that resembles the prior learning experience, whereas pattern separation processes (Besnard & Sahay, 2016) refers to the discrimination of a novel input pattern from a stored memory representation (Ally et al, 2013; Rudy & O’Reilly, 2001; Yassa & Stark, 2011; though see Aimone, Deng, & Gage, 2011; Hunsaker & Kesner, 2013 for a critical review of such framework). Given that threat generalization is characteristic of anxiety- and stress-related disorders, we investigated whether participants’ memory performance was associated with the amount of conditioned autonomic arousal at the time of encoding, self-reported intolerance of uncertainty, and trait levels of anxiety.

Figure 1. Behavioral task paradigm.

During conditioning, participants rated shock expectancy; shocks were paired with 30 out of 60 animal or tool pictures (counterbalanced across participants). During the memory test, participants indicated whether the presented picture was new, old or similar. Colored borders are for illustrative purposes, and not part of the stimuli shown to subjects.

Methods

Participants

Based on our prior studies (Dunsmoor et al., 2012, 2015), thirty healthy participants were recruited. One participant was removed from the analysis for failing to complete day 1, three for failing to return for day 2, and one due to computer malfunctioning. This left a total of 25 participants in the analysis (6 males; age M=22.29 years, SD=3.69 years). The study followed APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and was approved by the University Committee on Activities Involving Human Subjects at New York University. All participants provided written informed consent to participation and were compensated monetarily.

Independent variables

The study included two experimental sessions, threat conditioning and a surprise recognition memory test, that occurred 24 hours apart (Fig. 1).

Day 1: Encoding: threat conditioning.

The Pavlovian threat-conditioning task presented 120 trial-unique pictures of animals (60) and tools (60) on a white background as conditioned stimuli (CS). For the threat-conditioned category (CS+, animals or tools counterbalanced between subjects) 30 out of 60 trials co-terminated with a 200ms aversive shock (unconditioned stimulus, US; 50% CS-US pairing rate). The shock was administered through pre-gelled snap electrodes (BIOPAC EL508) attached to the right wrist and connected to a Grass Medical Instruments stimulator (Model SD9; West Warwick, Rhode Island). A within-subjects control category (CS−, tools or animals, respectively) was never paired with shock. Each trial was presented for 4.5s followed by a jittered 8–10s of inter trial interval (ITI) during which a fixation cross on a blank screen was presented. The stimulus on each trial was a different exemplar of the category that was never repeated (i.e. each stimulus could be identified by a unique name, so for example there were not two different pictures of a dog during threat conditioning).

Day 2: Surprise recognition memory test.

The structure of the memory test was modeled after paradigms designed to asses behavioral pattern completion and separation (Kirwan & Stark, 2007). It included a total of 180 pictures (90 animals and 90 tools). Of these, 60 pictures (30 animals, 30 tools) were old targets (i.e. the picture on the screen was exactly like a picture seen on Day 1), 60 were similar lures (i.e. the picture on the screen was different from, but similar to, a picture seen on Day 1, e.g. during acquisition a dog was presented and during the memory test the same dog but with different body position was presented), and 60 were novel foils (i.e. the picture on the screen was a unique exemplar of an object that was never presented on Day 1). Note that, for items of the CS+ category, the number of old targets and similar lures was equally divided over shocked and non-shocked items. On each trial, subjects had 4s to respond if the picture was ‘old’, ‘similar’, or ‘new’. Each trial was followed by a jittered 500–1500ms ITI.

Dependent variables

Skin conductance response.

Galvanic skin conductance was recorded at 200Hz from pre-gelled snap electrodes (BIOPAC EL509) placed on the hypothenar eminence of the palmar surface of the left hand connected to a BIOPAC MP-100 System (Goleta, CA). The digitalized signal was processed using Autonomate 2.8 (Green, Kragel, Fecteau, & LaBar, 2014) to obtain trough-to-peak SCR values. A SCR was considered valid if the trough-to-peak deflection occurred between 0.5–4.5s following the presentation of the CS, was greater than 0.02μS and lasted for maximum 5s. Trials that did not meet these criteria were scored as zero (Dunsmoor et al., 2015). The raw SCRs were square root transformed to normalize the data distributions. Only non-reinforced CS+ trials and all CS− trials were included in further analysis. Mean SCRs to CS+ and CS− were analyzed to verify threat conditioning acquisition.

Shock expectancy.

Shock expectancy was rated on each trial using a two-alternative forced-choice button press (‘yes’=shock, ‘no’=no-shock). The mean proportion of ‘yes’ response to CS+ and CS− were analyzed to verify threat conditioning acquisition.

Episodic memory.

Bias corrected memory scores were calculated to evaluate episodic memory recognition, generalization and discrimination to CS+ and CS−. Respectively, a corrected item recognition memory score was calculated as the probability of correctly endorsing targets as old minus endorsing foils as old (Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007). A generalization score was calculated as the probability of endorsing lures as old minus the probability of endorsing foils as old (Ally et al., 2013). We also calculate a lure discrimination index (LDI) as the probability of correctly endorsing lures as similar minus the probability of endorsing foils as similar (Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007). Note that additional graphs and analyses on the raw proportions of responses are reported in the Supplemental Materials.

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS) (Buhr & Dugas, 2002).

This is a self-report questionnaire assessing the difficulty in tolerating uncertain situations and the degree of worry about them. It comprises 27 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Not at all characteristic of me’ to ‘Entirely characteristic of me’. The total score results from the sum of the scores obtained on each question, with higher score indicating greater intolerance of uncertainty.

State Trait Anxiety Questionnaire (STAI) (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983).

The trait portion of form Y of the STAI was used to assess symptoms of trait anxiety. This is a self-report questionnaire, which comprises 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Almost never’ to ‘Almost always’. The total score results from the sum of the scores obtained on each question and indicates the severity of symptoms, with higher score indicating greater anxiety.

Procedures

Day 1: Encoding: Threat conditioning.

First, SCR electrodes and the shock electrodes were attached. The intensity of the shock was calibrated for each participant to a level deemed ‘highly unpleasant, but not painful’, using an ascending staircase procedure. Participants rated the unpleasantness of the shock on a 0 (no sensation) to 10 (very high intensity) scale (M=6.66, SD=0.91). Next, participants were told that on each trial a picture of an animal or tool would appear on the screen and that it might co-terminate with a shock. No information was provided regarding which category would be paired with the shock and participants had to learn this from experience. Participants’ task was to make a shock expectancy rating on each trial by a button press. They were informed that neither their speed nor their accuracy would influence whether or not they received a shock, in order to eliminate the possibility of participants attributing administration of the shock to their actions. The task took about 45min to complete.

Day 2: Surprise recognition memory test.

No specific information about the purpose of day 2 was provided to participants beforehand. Before starting the memory test, participants were asked the open ended question “what are your expectations for today’s experiment?”, in order to validate the memory test was a surprise. Nearly all participants reported that they either expected a continuation of what they did the day before (i.e., fear conditioning) or that they did not know. Only one participant expected a memory test. We did not exclude this subject in the final analyses, but including this data did not change the results in any meaningful way. We then told participants that they were going to do a memory test, and asked how surprised they were on a 1 (not surprised at all) to 9 (totally surprised) scale. The average rating was 5.48 (min=4, max=8). Participants were told that on each trial a picture would appear on the screen and their task was to be as fast and as accurate as possible in deciding whether the picture was ‘old’, ‘similar’, or ‘new’. The task took about 20min to complete. At the end of the task participants also completed the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (Buhr & Dugas, 2002) and the trait form of the State Trait Anxiety Questionnaire (Spielberger et al., 1983).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Supplemental Materials.

Results

Data met assumptions of normal distribution and homoscedasticity; therefore parametric tests were used for analysis.

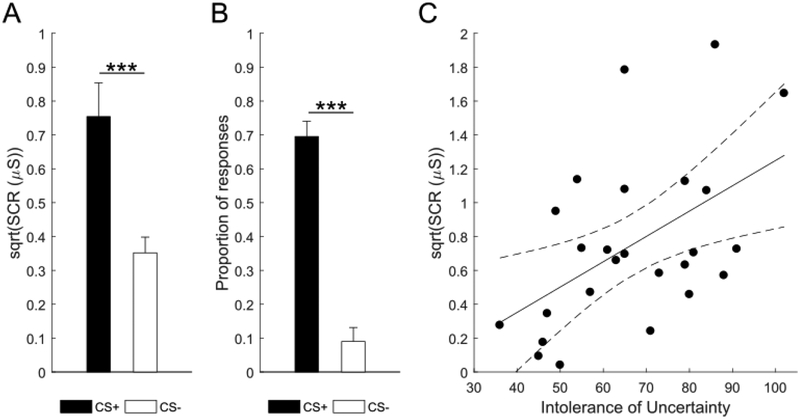

Arousal and shock expectancy indicate acquisition of threat conditioning

First, we assessed acquisition of threat conditioning on day 1 by comparing mean square-root-normalized SCRs for the CS+ and the CS- category. A paired t-test indicated higher mean SCR for the CS+ than the CS− category (t(24)=4.90, p<.001, dav=1.10; CS+: M=0.75, SD=0.50; CS−: M=0.35, SD=0.23; Fig. 2a). Likewise, analysis of mean expectancy ratings revealed that participants were more likely to expect the shock on CS+ than CS− trials (t(24)=7.27, p<.001, dav=2.63; CS+: M=0.68, SD=0.23; CS−: M=0.09, SD=0.22; Fig. 2b). Thus, category conditioning led to the acquisition of autonomic threat responses and explicit awareness of conditioned threat expectation.

Figure 2. Acquisition of threat conditioning and correlation between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Skin Conductance Response (SCR).

Acquisition of threat conditioning was shown by higher mean square-root-normalized SCR in μS (a) and higher shock expectancy (b) on CS+ than CS− trials. Error bars represent standard error of the mean, ***p<.001, two-tailed paired-samples t-test. In addition, Intolerance of Uncertainty predicted mean square-root-normalized SCR in μS to the conditioned category (c). Dashed lines represent 95% confidence interval, p<.05, simple linear regression.

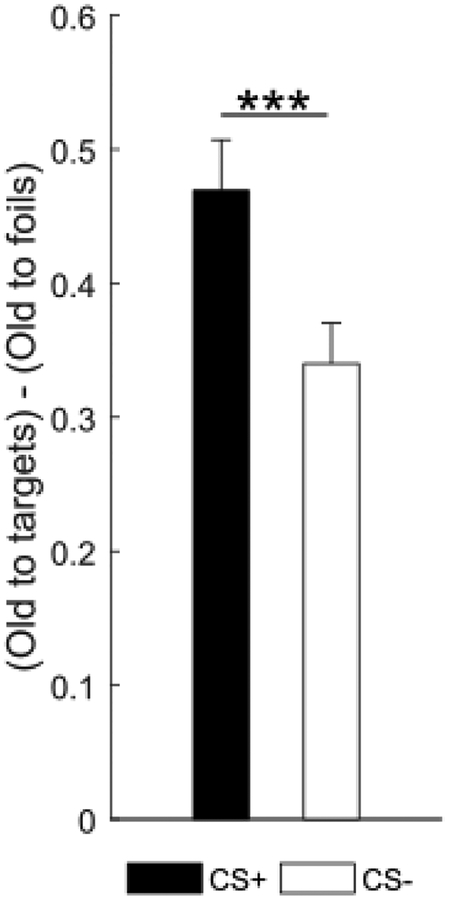

Threat conditioning enhances subsequent recognition memory and episodic memory generalization for the conditioned category

Threat conditioning on day 1 enhanced subsequent recognition memory for items of the conditioned category on day 2 (Fig. 3). A paired t-test on bias corrected mean item recognition scores (i.e. responding old to targets minus responding old to foils; Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007) revealed better recognition of CS+ than CS− items (t(24)=4.03, p<.001, dav= 0.76; CS+: M=0.47, SD=0.19; CS−: M=0.34, SD=0.15), replicating previous reports (Dunsmoor et al., 2012, 2015; Kroes et al., 2017).

Figure 3. Recognition memory.

Bias corrected item recognition score (i.e. responding old to targets minus responding old to foils) showed better recognition of items from the CS+ than CS− category. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. ***p<.001, two-tailed paired-samples t-test.

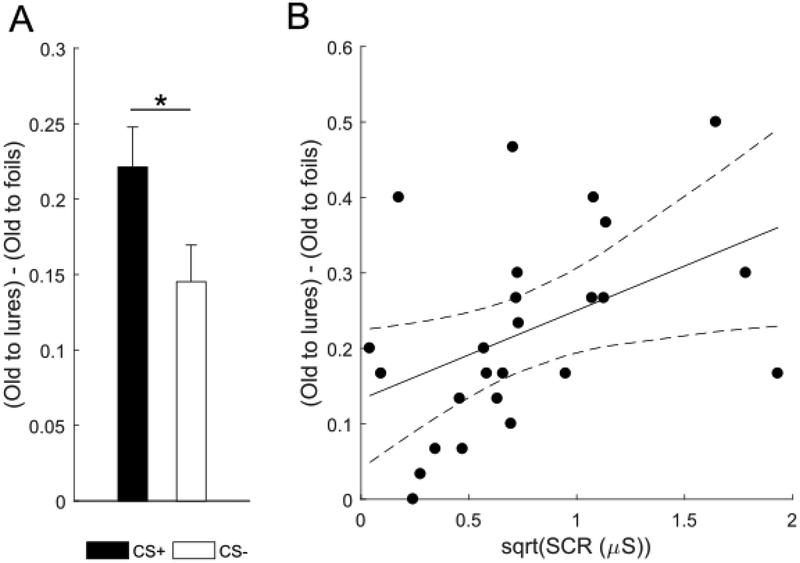

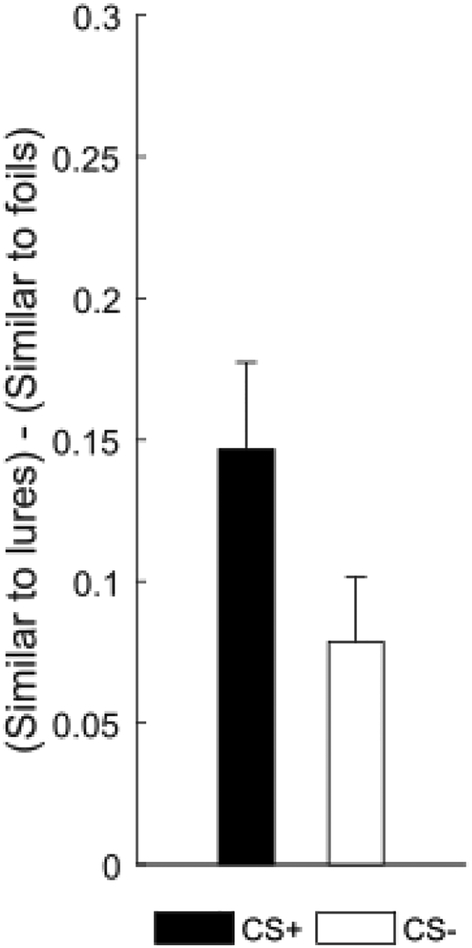

We next assessed the effect of threat conditioning on episodic memory generalization and discrimination. We found that threat conditioning enhanced genelaization scores (Fig. 4a). A paired t-test on mean generalization scores (i.e. responding old to lures minus responding old to foils)(Ally et al., 2013) revealed greater generalization for items of the CS+ than the CS− category (t(24)=2.47, p=.021, dav= 0.60; CS+: M=0.22, SD=0.13; CS−: M=0.14, SD=0.12). That is, subjects were more likely to endorse lures from the threat-conditioned category as ‘old’ than lures from the control category. However, we found no evidence that threat conditioning affected discrimination. A paired t-test on mean lure discrimination index (LDI, i.e. responding similar to lures minus responding similar to foils; Clemenson & Stark, 2015; Kirwan & Stark, 2007) revealed no difference between the CS+ and CS− category (t(24)=1.92, p=.067, dav= 0.51; CS+: M=0.15, SD=0.15; CS−: M=0.08, SD=0.11, Fig. 5). Thus, threat conditioning resulted in greater item recognition and episodic memory generalization but did not significantly affect discrimination of episodic memory after 24 hours.

Figure 4. Episodic memory generalization and its correlation with arousal for the conditioned category.

(a) Episodic generalization score (i.e. responding old to lures minus responding old to foils) was greater for items from the CS+ than CS− category. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. *p<.05, two-tailed paired-samples t-test. (b) Mean square-root-normalized SCR in μS to the conditioned category predicted episodic memory generalization score for the conditioned category. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence interval, p<.05, simple linear regression.

Figure 5. Episodic memory discrimination.

Lure Discrimination Index score (i.e. responding similar to lures minus responding similar to foils) showed no difference for items from the CS+ and CS− category. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Two-tailed paired-samples t-test.

Arousal responses predict episodic memory generalization for the conditioned category

Next, we examined whether mean SCR to the CS+ category during threat conditioning predicted subsequent recognition memory and generalization for the CS+ category. Simple linear regression showed no evidence for an effect of mean SCR on mean item recognition scores (p=.154). In contrast, mean SCRs to CS+ category on day 1 positively predicted subsequent generalization scores for the CS+ category on day 2 (unstandardised β=0.12, t(24)=2.38, p=.026; R2=0.20, F(1,24)=5.66, p=.026; Fig. 4b). Thus, autonomic arousal during threat conditioning was associated with greater episodic memory generalization for items of the conditioned category, but was not associated with the tendency to accurately identify items from the conditioned category encoded the previous day. In addition, we examined whether mean SCR to the CS− category during threat conditioning predicted subsequent episodic memory generalization for the CS− category, in order to understand whether episodic memory generalization was driven by general arousal or specifically by conditioned arousal. Simple linear regression showed no evidence for an effect of mean SCR to CS- category on subsequent generalization scores for the CS- category (p=.977).

Intolerance of uncertainty predicts arousal to but not memory for the conditioned category

Finally, we tested if intolerance of uncertainty and trait anxiety influenced mean SCR during threat conditioning and subsequent item recognition and episodic memory generalization for the CS+ category. Simple linear regression revealed that participants’ intolerance of uncertainty score positively predicted mean SCRs for the CS+ category (unstandardised β=0.01, t(24)=2.85, p=.009; R2=0.26, F(1,24)=8.13, p=.009; Fig. 2c). However, trait anxiety did not predict mean SCR for CS+ (p=.130). Neither intolerance of uncertainty nor trait anxiety predicted item recognition or pattern completion for CS+ (all ps≥.096).

Discussion

Episodic memories help us remember the details of an emotional experience and help guide behavior in similar situations in the future. The goal of this study was to examine the effect of Pavlovian threat conditioning, a form of emotional learning, on long-term episodic memory generalization. We found that threat conditioning enhanced subsequent item recognition memory, such that items from the threat conditioned category were better remembered than items from another category never paired with shock, replicating previous findings (Dunsmoor et al., 2012, 2015; Kroes et al., 2017). Threat conditioning also promoted the generalization of episodic threat memories. Specifically, similar lures of the conditioned category were more likely to be misidentified as old, compared to similar lures of the category never paired with shock. However, threat conditioning did not significantly affect discrimination, that is, participants had comparable performance, in correctly identifying as similar, lures from the CS+ and CS− category. Furthermore, we found that the degree of autonomic arousal at the time of threat acquisition predicted generalization of episodic memory for items of the conditioned category but not for the CS− category. However, autonomic arousal was unrelated to subsequent recognition memory accuracy. Finally, intolerance of uncertainty, a characteristic of anxiety disorders that describes the degree of worry about uncertain situations (Buhr & Dugas, 2002; Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998), positively predicted the degree of autonomic arousal at the time of threat acquisition but not memory performance.

Our main finding is that threat conditioning enhances subsequent generalization of episodic memory. This result suggests that episodic memory generalization may be an active process where threat cues presented at the time of retrieval trigger recollection of stored episodic memory representations of aversive experiences. This idea is in line with the literature on the generalization of threat responses (Dunsmoor, Kragel, Martin, & LaBar, 2014; Onat & Büchel, 2015) that argued that stimulus generalization is an active process (Shepard, 1987), which leads to response generalization despite perceptual discrimination between originally conditioned stimuli and a similar ones (Guttman & Kalish, 1956; Pavlov, 1927). In the context of threat conditioning, active generalization of threat representations stored in episodic memory may confer an adaptive advantage, as incorrectly identifying a safe stimulus as a dangerous stimulus is far less costly than the alternative (Dunsmoor & Paz, 2015; Laufer, Israeli, & Paz, 2016).

We also found that conditioned autonomic arousal at the time of encoding was related to subsequent episodic memory generalization processes at the time of memory retrieval only for the conditioned category. This finding suggests that the arousal specifically elicited by threat conditioning (conditioned SCRs, and not just SCR in general) was related to the future explicit memory generalization. It also extends the long-established emotional enhancement of episodic memory encoding and consolidation (Cahill et al., 1996; Cahill & McGaugh, 1995; Christianson & Loftus, 1987, 1991), showing that emotion can also affect specific episodic memory processes at the time of retrieval. It is possible that similar lures of the conditioned category would likewise evoke generalized threat responses, which in turn could have enhanced memory generalization. A limitation of the current study is that physiological threat responses were not acquired during retrieval because evaluating autonomic arousal in absence of a threat of shock was methodologically challenging—and assessing recognition memory during threat of shock would have complicated interpretation of the memory results. Nevertheless, previous research has indicated that emotion-related responses and amygdala activation can affect episodic memory processes at the time of retrieval (Kroes, Strange, & Dolan, 2010; Maratos, Dolan, Morris, Henson, & Rugg, 2001; A. P. R Smith, Henson, Dolan, & Rugg, 2004; Adam P. R. Smith, Stephan, Rugg, & Dolan, 2006; Takashima, van der Ven, Kroes, & Fernández, 2016). Future studies should address this issue assessing if enhanced episodic memory generalization is accompanied by greater threat response generalization for the conditioned category.

As this is the first explorative study into the effect of conditioning on episodic memory generalization, we decided to follow a widely used theoretical framework that investigates memory generalization/discrimination in terms of pattern completion/separation and chose the Mnemonic Similarity Task (MST) to test our hypothesis. However, parsing pattern completion/separation in human memory research is challenging, and the MST protocol and it’s memory indices may not be sufficient to dissociate pattern completion/separation operations (e.g., Aimone, Deng, & Gage, 2011; Hunsaker & Kesner, 2013; Loiotile & Courtney, 2015). Future studies should account for difficulties distinguishing between pattern completion and pattern separation and perhaps use alternative protocols, analyses methods, or high-resolution imaging to elucidate the information processing operations that underlie the episodic threat memory generalization we found (Loiotile & Courtney, 2015; Yassa & Stark, 2011). Furthermore, episodic threat memory generalization may not be depend on pattern completion/separation processes but result from the hierarchy of stimulus classification to which threat was associated on day 1. For example, if a subject encoded the visual items by focusing on a verbal label (e.g., maybe they encode a picture of a Golden Retriever at the basic level, “dog,” and not the subordinate level, “Golden Retriever”), then they might “misremember” seeing a German Sheppard as having seen “a dog”. Whether and how differences in encoding strategy affect episodic memory generalization and how this interacts with threat learning remains an open question for future investigation.

From a clinical perspective, overgeneralization of episodic memories may contribute to maladaptive overgeneralization of threat memories. For instance, highly emotional events could lead to subsequent misidentification of similar people, stimuli, or situations as threatening even in a safe context. The positive correlation between arousal at the time of encoding and subsequent memory generalization for stimuli of the conditioned category is in line with this idea, albeit in healthy subjects. Contrary to this, a recent theoretical account proposes that threat overgeneralization, characteristic of PTSD, would be determined by an impairment in pattern separation (Besnard & Sahay, 2016; Kheirbek et al., 2012). Specifically, PTSD is thought to be marked by an inability to discriminate between sensory inputs similar to the traumatic memory, grouping them together despite their differences, leading to overlapping memory representations and overgeneralization of the threat memory. This discrimination deficit is supported by the finding of an inverse relationship between discrimination ability and generalization of threat expectation in healthy participants (Lange et al., 2017). Another possibility is that overgeneralization in PTSD may trigger recollection of the traumatic event even in conditions of safety, when faced by threat cues resembling the traumatic event. The current paradigm could be used in clinical populations to clarify these different accounts of threat generalization in PTSD.

In conclusion, we found that Pavlovian threat conditioning enhanced generalization of emotional episodic memories. This supports the idea that behavioral generalization might be driven at least in part by an explicit process of episodic memory generalization, where threat cues presented at the time of retrieval trigger recollection of stored episodic memory representations of aversive experiences. Enhanced memory generalization following threat learning may be adaptive to efficiently promote avoidance of stimuli similar to previously learned threats. However, in extreme cases, generalization of threat conditioned episodic memories may become maladaptive by leading to overgeneralization of threat memories in the face of harmless stimuli or situations. Whether an overactive process of memory generalization is a contributing factor to the etiology and maintenance of PTSD warrants further research.

Context of the Research.

We show that Pavlovian threat-conditioning induces a bias to generalize episodic memory in humans. This research fits in a broader context of two mostly separated literatures on emotional learning and memory: stimulus generalization as it is defined in the Pavlovian conditioning tradition, and pattern completion as it is defined in human episodic memory research. Here, we synthesize these two literatures to show that Pavlovian conditioning has unique effects on episodic memory, promoting an explicit bias to judge items similar to a conditioned stimulus as having been encountered in the past. The data fit with an active research program on the intersection between conditioning and episodic memory, which has already shown how conditioning can enhance retroactive memory for conceptually related stimuli (Dunsmoor et al., 2015; Patil, Murty, Dunsmoor, Phelps, & Davachi, 2017) and that event boundaries between conditioning and extinction helps organize episodic memory by segmenting competing experiences of threat and safety (Dunsmoor et al., 2018). This research will be extended to patients with stress and anxiety disorders to examine whether these disorders are characterized by an overgeneralization of explicit episodic memory following a threat learning experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH R01 MH097085 to E.A.P.. J.E.D. is supported by NIH R00 MH106719 and M.C.K. is supported by an H2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellowship and a Society in Science - Branco Weiss fellowship. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Adolphs R, Denburg NL, & Tranel D (2001). The amygdala’s role in long-term declarative memory for gist and detail. Behavioral Neuroscience, 115(5), 983 10.1037/0735-7044.115.5.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, & Buchanan TW (2005). Amygdala damage impairs emotional memory for gist but not details of complex stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, 8(4), 512–518. 10.1038/nn1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimone JB, Deng W, & Gage FH (2011). Resolving New Memories: A Critical Look at the Dentate Gyrus, Adult Neurogenesis, and Pattern Separation. Neuron, 70(4), 589–596. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ally BA, Hussey EP, Ko PC, & Molitor RJ (2013). Pattern Separation and Pattern Completion in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence of Rapid Forgetting in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Hippocampus, 23(12), 1246–1258. 10.1002/hipo.22162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besnard A, & Sahay A (2016). Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis, Fear Generalization, and Stress. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 24–44. 10.1038/npp.2015.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhr K, & Dugas MJ (2002). The intolerance of uncertainty scale: psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945. 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, Haier RJ, Fallon J, Alkire MT, Tang C, Keator D, … McGaugh JL (1996). Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(15), 8016–8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, & McGaugh JL (1995). A Novel Demonstration of Enhanced Memory Associated with Emotional Arousal. Consciousness and Cognition, 4(4), 410–421. 10.1006/ccog.1995.1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, & Loftus EF (1987). Memory for traumatic events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 1(4), 225–239. 10.1002/acp.2350010402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, & Loftus EF (1991). Remembering emotional events: The fate of detailed information. Cognition and Emotion, 5(2), 81–108. 10.1080/02699939108411027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemenson GD, & Stark CEL (2015). Virtual Environmental Enrichment through Video Games Improves Hippocampal-Associated Memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(49), 16116–16125. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2580-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougal S, & Rotello CM (2007). “Remembering” emotional words is based on response bias, not recollection. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(3), 423–429. 10.3758/BF03194083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, & Freeston MH (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: a preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(2), 215–226. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00070-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duits P, Cath DC, Lissek S, Hox JJ, Hamm AO, Engelhard IM, … Baas JMP (2015). Updated Meta-Analysis of Classical Fear Conditioning in the Anxiety Disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 32(4), 239–253. 10.1002/da.22353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Kragel PA, Martin A, & LaBar KS (2014). Aversive Learning Modulates Cortical Representations of Object Categories. Cerebral Cortex, 24(11), 2859–2872. 10.1093/cercor/bht138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Kroes MCW, Braren SH, & Phelps EA (2017). Threat intensity widens fear generalization gradients. Behavioral Neuroscience, 131(2), 168–175. 10.1037/bne0000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Kroes MCW, Moscatelli CM, Evans MD, Davachi L, & Phelps EA (2018). Event segmentation protects emotional memories from competing experiences encoded close in time. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 291–299. 10.1038/s41562-018-0317-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, & LaBar KS (2013). Effects of discrimination training on fear generalization gradients and perceptual classification in humans. Behavioral Neuroscience, 127(3), 350–356. 10.1037/a0031933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Martin A, & LaBar KS (2012). Role of conceptual knowledge in learning and retention of conditioned fear. Biological Psychology, 89(2), 300–305. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, & Murphy GL (2014). Stimulus Typicality Determines How Broadly Fear Is Generalized. Psychological Science, 25(9), 1816–1821. 10.1177/0956797614535401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Murty VP, Davachi L, & Phelps EA (2015). Emotional learning selectively and retroactively strengthens memories for related events. Nature, 520(7547), 345–348. 10.1038/nature14106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, Otto AR, & Phelps EA (2017). Stress promotes generalization of older but not recent threat memories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(34), 9218–9223. 10.1073/pnas.1704428114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmoor JE, & Paz R (2015). Fear Generalization and Anxiety: Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry, 78(5), 336–343. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Hackmann A, Steil R, Clohessy S, Wenninger K, & Winter H (2002). The nature of intrusive memories after trauma: the warning signal hypothesis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(9), 995–1002. 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00077-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SR, Kragel PA, Fecteau ME, & LaBar KS (2014). Development and validation of an unsupervised scoring system (Autonomate) for skin conductance response analysis. International Journal of Psychophysiology: Official Journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology, 91(3), 186–193. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman N, & Kalish HI (1956). Discriminability and stimulus generalization. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 51(1), 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad ADM, Xu M, Raeder S, & Lau JYF (2013). Measuring the role of conditioning and stimulus generalisation in common fears and worries. Cognition & Emotion, 27(5), 914–922. 10.1080/02699931.2012.747428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Boeke EA, Wolthusen RPF, Nasr S, Milad MR, & Tootell RBH (2014). A parametric study of fear generalization to faces and non-face objects: relationship to discrimination thresholds. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 624 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker MR, & Kesner RP (2013). The operation of pattern separation and pattern completion processes associated with different attributes or domains of memory. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(1), 36–58. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensinger EA (2009). Remembering the Details: Effects of Emotion. Emotion Review, 1(2), 99–113. 10.1177/1754073908100432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Klemenhagen KC, Sahay A, & Hen R (2012). Neurogenesis and generalization: a new approach to stratify and treat anxiety disorders. Nature Neuroscience, 15(12), 1613–1620. 10.1038/nn.3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, & Stark CEL (2007). Overcoming interference: An fMRI investigation of pattern separation in the medial temporal lobe. Learning & Memory, 14(9), 625–633. 10.1101/lm.663507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes MCW, Dunsmoor JE, Lin Q, Evans M, & Phelps EA (2017). A reminder before extinction strengthens episodic memory via reconsolidation but fails to disrupt generalized threat responses. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 10858 10.1038/s41598-017-10682-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes MCW, Strange BA, & Dolan RJ (2010). β-Adrenergic Blockade during Memory Retrieval in Humans Evokes a Sustained Reduction of Declarative Emotional Memory Enhancement. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(11), 3959–3963. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5469-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBar KS, & Cabeza R (2006). Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 7(1), 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange I, Goossens L, Michielse S, Bakker J, Lissek S, Papalini S, … Schruers K (2017). Behavioral pattern separation and its link to the neural mechanisms of fear generalization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(11), 1720–1729. 10.1093/scan/nsx104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufer O, Israeli D, & Paz R (2016). Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms of Overgeneralization in Anxiety. Current Biology, 26(6), 713–722. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal SL, Tighe SK, & Yassa MA (2014). Asymmetric effects of emotion on mnemonic interference. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 111, 41–48. 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J (2014). Coming to terms with fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(8), 2871–2878. 10.1073/pnas.1400335111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Biggs AL, Rabin SJ, Cornwell BR, Alvarez RP, Pine DS, & Grillon C (2008). Generalization of conditioned fear-potentiated startle in humans: Experimental validation and clinical relevance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(5), 678–687. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Bradford DE, Alvarez RP, Burton P, Espensen-Sturges T, Reynolds RC, & Grillon C (2014). Neural substrates of classically conditioned fear-generalization in humans: a parametric fMRI study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(8), 1134–1142. 10.1093/scan/nst096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Powers AS, McClure EB, Phelps EA, Woldehawariat G, Grillon C, & Pine DS (2005). Classical fear conditioning in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(11), 1391–1424. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiotile RE, & Courtney SM (2015). A signal detection theory analysis of behavioral pattern separation paradigms. Learning & Memory, 22(8), 364–369. 10.1101/lm.038141.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratos EJ, Dolan RJ, Morris JS, Henson RNA, & Rugg MD (2001). Neural activity associated with episodic memory for emotional context. Neuropsychologia, 39(9), 910–920. 10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00025-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S (2001). Neurobiology of Pavlovian Fear Conditioning. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 897–931. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, & Sutherland MR (2011). Arousal-Biased Competition in Perception and Memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(2), 114–133. 10.1177/1745691611400234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrholm SD, Jovanovic T, Briscione MA, Anderson KM, Kwon CK, Warren VT, … Bradley B (2014). Generalization of fear-potentiated startle in the presence of auditory cues: a parametric analysis. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 361 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onat S, & Büchel C (2015). The neuronal basis of fear generalization in humans. Nature Neuroscience, 18(12), 1811 10.1038/nn.4166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Murty VP, Dunsmoor JE, Phelps EA, & Davachi L (2017). Reward retroactively enhances memory consolidation for related items. Learning & Memory, 24(1), 65–69. 10.1101/lm.042978.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP (1927). Conditioned reflexes; an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. London: Oxford Univ. Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, & LeDoux JE (2005). Contributions of the Amygdala to Emotion Processing: From Animal Models to Human Behavior. Neuron, 48(2), 175–187. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW, & O’Reilly RC (2001). Conjunctive representations, the hippocampus, and contextual fear conditioning. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 1(1), 66–82. 10.3758/CABN.1.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechtman E, Laufer O, & Paz R (2010). Negative Valence Widens Generalization of Learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(31), 10460–10464. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2377-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard RN (1987). Toward a Universal Law of Generalization for Psychological Science. Science, 237(4820), 1317–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith APR, Henson RNA, Dolan RJ, & Rugg MD (2004). fMRI correlates of the episodic retrieval of emotional contexts. NeuroImage, 22(2), 868–878. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Adam P. R., Stephan KE, Rugg MD, & Dolan RJ (2006). Task and Content Modulate Amygdala-Hippocampal Connectivity in Emotional Retrieval. Neuron, 49(4), 631–638. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, & Jacobs GA (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark SM, Stevenson R, Wu C, Rutledge S, & Stark CEL (2015). Stability of age-related deficits in the mnemonic similarity task across task variations. Behavioral Neuroscience, 129(3), 257–268. 10.1037/bne0000055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, van der Ven F, Kroes MCW, & Fernández G (2016). Retrieved emotional context influences hippocampal involvement during recognition of neutral memories. NeuroImage, 143(Supplement C), 280–292. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltgen BJ, & Silva AJ (2007). Memory for context becomes less specific with time. Learning & Memory, 14(4), 313–317. 10.1101/lm.430907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, & Stark CEL (2011). Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends in Neurosciences, 34(10), 515–525. 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Supplemental Materials.