Summary

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency caused by mutations in any of the genes encoding the phagocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase system, responsible for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). CGD is marked by invasive bacterial and fungal infections and by autoinflammation/autoimmunity, of which the exact pathophysiology remains elusive. Contributing factors include decreased neutrophil apoptosis, impaired apoptotic neutrophil clearance, increased proinflammatory protein expression and reduced ROS‐mediated inflammasome dampening. We have explored a fundamentally different potential mechanism: it has been reported that macrophage‐mediated induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) depends on ROS production. We have investigated whether numerical or functional deficiencies exist in Tregs of CGD patients. As the prevalence of autoinflammation/autoimmunity differs between CGD subtypes, we have also investigated Tregs from gp91phox‐, p47phox‐ and p40phox‐deficient CGD patients separately. Results show that Treg numbers and suppressive capacities are not different in CGD patients compared to healthy controls, with the exception that in gp91phox‐deficiency effector Treg (eTreg) numbers are decreased. Expression of Treg markers CD25, inducible T cell co‐stimulator (ICOS), Helios, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA‐4) and glucocorticoid‐induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR) did not provide any clue for differences in Treg functionality or activation state. No correlation was seen between eTreg numbers and patients' clinical phenotype. To conclude, the only difference between Tregs from CGD patients and healthy controls is a decrease in circulating eTregs in gp91phox‐deficiency. In terms of autoinflammation/autoimmunity, this group is the most affected. However, upon culture, patient‐derived Tregs showed a normal phenotype and normal functional suppressor activity. No other findings pointed towards a role for Tregs in CGD‐related autoinflammation/autoimmunity.

Keywords: chronic granulomatous disease, regulatory T cell, inflammation

Introduction

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a rare primary immunodeficiency (~1 : 250 000 patients) caused by inactivating mutations in the genes encoding the different nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase subunits. This results in impaired production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The NADPH oxidase enzyme is a multi‐protein complex consisting of a membrane‐bound component [the gp91phox (phox = phagocyte oxidase) and p22phox proteins] as the catalytic core of the system, and a cytosolic component (the p67phox, p47phox and p40phox proteins). After phagocytosis, the cytosolic component translocates towards the membrane‐bound component, activating the complex. Then, a burst of oxygen consumption takes place and ROS are formed 1, which are critical for the killing of pathogenic bacteria and fungi. CGD is therefore characterized by life‐threatening invasive bacterial and fungal infections 2. Another important characteristic of CGD is the presence of excessive inflammation, such as granuloma formation in among others the skin and the urinary tract, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and (discoid) lupus 3. Contributing factors implicated in the pathophysiology of this autoinflammation/autoimmunity include decreased neutrophil apoptosis, impaired apoptotic neutrophil clearance, increased proinflammatory protein expression and reduced ROS‐mediated inflammasome dampening 2, 4, 5, 6.

We here explored a fundamentally different potential mechanism: it has been reported that macrophage‐mediated induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) depends on ROS production 7. Kraaij et al. showed that macrophage‐derived ROS of healthy people can induce Tregs, whereas macrophages from CGD patients were significantly impaired in Treg induction. Tregs are CD4+CD25+forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3)+ or CD127– cells important for immunological tolerance. Naive, thymus‐derived Tregs (nTregs) form the majority of Tregs in lymphoid tissues and express CD62L and CCR7. Tregs can also differentiate into effector Tregs (eTregs), which is the most abundant Treg fraction in non‐lymphoid tissues. These cells express high levels of CD44, inducible T cell co‐stimulator (ICOS) and glucocorticoid‐induced tumor necrosis factor‐related receptor (GITR) as well as B lymphocyte‐induced maturation protein‐1 (BLIMP)‐1 and IL‐10, consistent with a functional and suppressive phenotype 8.

It has also been suggested that asbestos‐derived ROS activate transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β 9 and that TGF‐β is important for T cell suppression by anti‐inflammatory (M2) macrophage‐induced Tregs in humans 10. Moreover, it has recently been shown that human CD8+ Tregs suppress CD4+ T cells by secreting NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) (gp91phox)‐containing vesicles 11. This results in elevated ROS levels in the CD4+ T cell and consequently in reduced phosphorylation of the T cell receptor (TCR)‐associated zeta chain‐associated protein kinase of 70 kD (ZAP70), which inhibits the T cell receptor 12. Another role for ROS in Treg functioning was seen when Efimova et al. compared the capacities of Tregs from wild‐type and p47phox‐deficient mice in suppressing effector T cell proliferation. These authors showed that NCF1 (encoding p47phox)‐deficient Tregs suppressed p47phox‐deficient effector T cells very poorly compared to wild‐type Tregs 13. Kwon et al. also used a mouse model to show that Nox2 deficiency results in (among others) T cell hyperactivation and diminished Treg differentiation 14.

Besides the fact that excessive inflammation is one of the characteristics of CGD, it is known that the prevalence of inflammatory complications differs between CGD subtypes 15. Therefore, it would be highly informative to further study the role of Tregs in CGD‐related inflammation. Hence, we have investigated whether numerical or functional Treg deficiencies exist in different, well‐characterized and fully genotyped gp91phox‐, p47phox‐ and p40phox‐deficient CGD patients.

Materials and methods

Blood samples and cell isolation

Blood samples from CGD patients were drawn after written informed consent had been obtained and after approval from the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands (2013_234/NL40331.078.12, ‘Primary immunodeficiencies: immunological and genetic background in relation to clinical complications’). Blood samples of healthy individuals were obtained from anonymized healthy donors recruited from an internal system at Sanquin, approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam. Written informed consent was also obtained. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013. From all included patients, lymphocyte counts, CD4 and CD8 counts from the day of peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation were collected from the medical chart, as well as the mutational details, age at blood sampling, medical history and current treatment.

PBMCs from both patients and controls were isolated by Percoll gradient (1·076 g/ml) centrifugation (1006 g rpm, 21°C, 20 min, Rotina 420 R; Hettich, Geldermalsen, the Netherlands). Treg (subsets) from the peripheral blood were counted by flow cytometry. CD4+CD25+CD127– and CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ were the markers used for Treg counts. The markers CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA+ and CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA– were used for naive and effector Tregs, respectively. For in‐vitro cell expansion viable cells were separated by flow cytometric sorting based on the expression of CD4, CD25, CD45RA and CD127 on a FACS Aria III (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were used: CD25 (43839), CD45RA (560675), ICOS (557802), CD8 (555369) from BD Biosciences. CD127 (351309) and CTLA‐4 (349906) from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). FoxP3 (25‐4777‐42), Helios (48‐9883) and CD4 (12‐0047‐42) were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA).

In‐vitro cell expansion

Naive conventional T responder cells (Tconvs) (CD4+, CD127+, CD25‐, CD45RA+) and naive Tregs (CD4+, CD127–, CD25+, CD45RA+) were isolated by fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) (FACS Aria III; BD Biosciences). The cells were then cultured in the presence of 0·1 µg/ml of anti‐CD3 mAb (M1654, clone 1XE, PeliCluster; Sanquin, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and anti‐CD28 mAb (16‐0289‐85, clone CD28.2; eBioscience) for 14 days in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) containing 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS) and 300 U/ml IL‐2 (Proleukin).

Flow cytometry

Cells were labeled with fluorochrome‐conjugated antibodies in phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), 0·5% (v/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min at 4°C. For intracellular and nuclear staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with the FoxP3/transcription factor fixation/permeabilization buffers (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Near‐IR (L10119; ThermoFisher, Fremont, CA, USA) dye was used to stain dead cells. Cells were analyzed on LSR Fortessa or LSR II cytometers (BD Biosciences).

In‐vitro cell suppression assay

The suppressive capacity of the in‐vitro expanded Tregs was assessed by inhibition of proliferation of co‐cultured responder T cells (Tresp) as described previously 16. Briefly, PBMCs were purified, labeled with CellTrace™ Violet cell proliferation kit (C34557, ThermoFisher) and stimulated with 0·01 µg/ml of anti‐CD3 mAb (M1654, clone 1XE, PeliCluster) and anti‐CD28 mAb (16‐0289‐85, clone CD28.2; eBioscience) at different ratios of Tresp : Treg in the absence of IL‐2. On day 5, cells were stained with antibodies against CD4 and CD8 and TOPRO‐3 (T3605; Invitrogen). Finally, cells were analyzed on LSR Fortessa or LSR II cytometers (BD Biosciences).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software). The variable distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A non‐parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison test to assess intergroup differences when three or more groups were compared. A non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U‐test was used when two groups were compared. P < 0·05 was considered statistically significant (*) at a 95% confidence level.

Results

Seven patients with X‐linked CGD (gp91phox deficiency), seven with autosomal recessive CGD (four with p47phox deficiency and three with p40phox deficiency) and seven healthy controls were included. Mutational and medical details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mutational and medical details from all included CGD patients.

| Patient | CGD subtype | Mutation | Age at blood draw (years) | Gender (M/F) | Lympho‐ cytes × 109/l | CD4+ × 109/l | CD8+ × 09/l | % CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ T cells | % CD4+ CD25+ CD127–CD45RA– eTregs | Treatment at moment of sampling | Clinical phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | gp91phox | 389Gly> Ala | 31·8 | M | 1 | 0·2 | 0·37 | 1–4% | 1–3% | Co‐trimoxazole, itraconazole, interferon γ | Recurrent pneumonia in childhood. Stable for the past 20 years |

| 2 | gp91phox | Frameshift | 3·9 | M | 5·59 | 1·39 | 0·97 | ≥4% | ≥3% | Co‐trimoxazole | Recurrent infections. Thymic abscesses, intra‐abdominal abcesses. No IBD |

| 3 | gp91phox | Promotor ‐52C>T | 17·7 | M | 2·38 | 0·875 | 0·542 | 1–4% | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole | Nocardia farcinica pneumonia during infancy |

| 4 | gp91phox | 38Lys>stop | 5·1 | M | 4·86 | 0·812 | 2·391 | ≥4% | 1–3% | Co‐trimoxazole | Aspergillus spondylodiscitis, lymphadenitis colli |

| 5 | gp91phox | 293Gln> stop | 4·6 | M | 3·58 | 1·38 | 0·54 | 1–4% | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole | Lymphadenopathy |

| 6 | gp91phox | Deletion exon 6‐13 | 14·9 | M | 1·74 | 0·72 | 0·35 | ≤1% | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole, interferon γ | 2 × otitis, 1 × dermatomycosis, celiac disease |

| 7 | gp91phox | c.877C>T; p.293 Gln> stop | NA | M | 6·02 | NA | NA | 1–4% | ≤1% | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | p47phox | Frameshift delGT + deletion cDNA exon 5 | 5·9 | M | NA | 1·49 | 4·45 | 1–4% | 1–3% | Co‐trimoxazole, mesalazine | Fungal infection of the skin, tinea capitis, noduli in the neck. IBD |

| 9 | p47phox | Frameshift delGT homozygous | 18 | M | 3·15 | 1·39 | 0·78 | ≥4% | ≥3% | Co‐trimoxazole, interferon γ | Pneumonia, S. aureus bacteremia with hepatic abscesses, recurrent dermatomycosis |

| 10 | p47phox | Frameshift delGT Homozygous | 11·3 | F | 2·03 | 0·79 | 0·59 | 1–4% | 1–3% | Co‐trimoxazole, triamcinolone (topical) | Inguinal lymphadenitis (Aspergillus), sometimes apthous lesions. Recurrent otitis |

| 11 | p47phox | Frameshift delGT homozygous | 15·9 | F | 2·09 | 1·14 | 0·9 | 1–4% | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole, itraconazole, interferon γ | S. epidermis pyelonephritis, fungal infection of the skin, 2× pulmonary Aspergillosis |

| 12 | p40phox | Splice site c.118‐G>A Homozygous | 14·5 | F | 1·27 | n.a. | n.a. | 1–4% | 1–3% | Co‐trimoxazole | IBD |

| 13 | p40phox | Splice site c.118‐G>A Homozygous | 3·1 | F | 2·3 | n.a. | n.a. | ≥4% | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole, itraconazole | Recurrent pulmonary infections, lung and lymph granuloma |

| 14 | p40phox | Splice site c.118‐G>A Homozygous | 10·6 | M | 0·64 | n.a. | n.a. | ≤1% | Co‐trimoxazole, itraconazole | IBD, S. aureus skin abscesses |

IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; Treg = regulatory T cell; CGD = chronic granulomatous disease; FoxP3 = forkhead box protein 3.

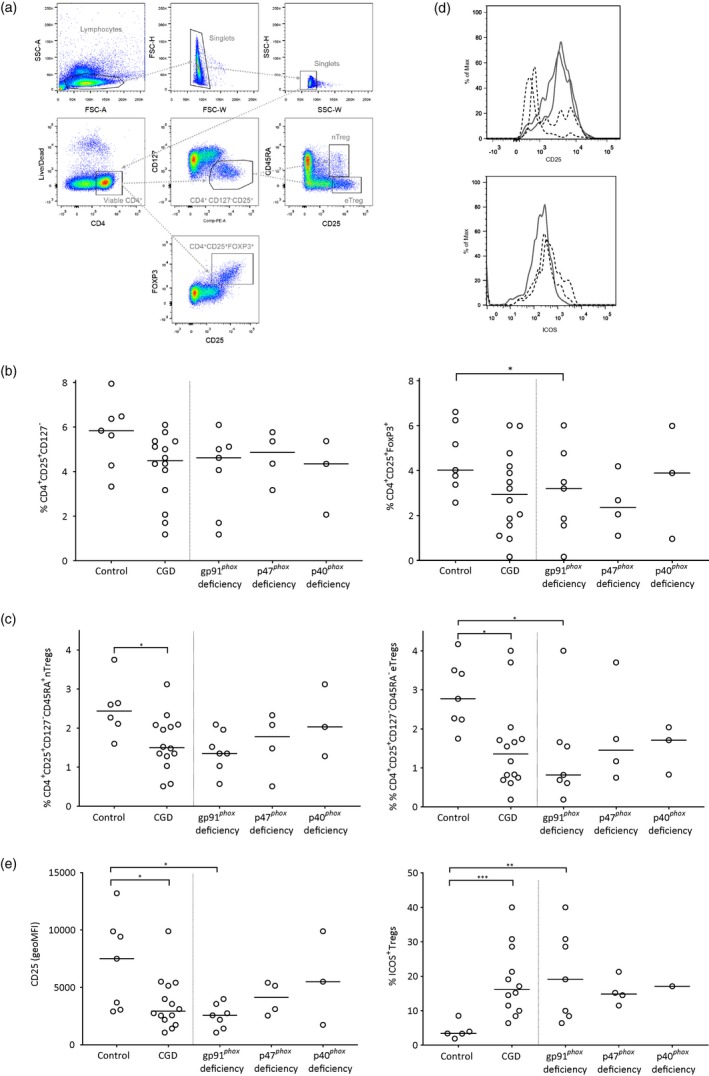

First, percentages of circulating Tregs among the T cell populations in these patients were calculated (direct measurements of absolute CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subset counts were not always available). Figure 1a shows the flow cytometry gating strategy used for these counts. Proportions of total CD4+CD25+CD127– (P = 0·06) and CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ (P = 0·075) Treg cell populations were not different between the cohort of all CGD patients and controls (Fig. 1b). However, the group of gp91phox‐deficient CGD patients by itself did possess significantly lower proportions of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs (Fig. 1b, right panel). Examination of Treg subpopulations showed that both naive (CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA+) and effector (CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA–) Treg populations were reduced in CGD patients (Fig. 1c). These effects were again most prominent among gp91phox‐deficient patients. As an essential surface protein for Treg function and maintenance 17, we assessed IL‐2 receptor alpha‐subunit CD25 expression and observed reduced expression in Tregs of gp91phox‐deficient patients (Fig. 1d, upper panel and 1E, left panel). In contrast, CGD patients had elevated percentages of Tregs expressing ICOS (Fig. 1d, lower panel and 1E, right panel), which is thought to be expressed in highly functional and suppressive cells 18.

Figure 1.

Numbers of regulatory T cells in healthy controls and in different chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) subtypes. (a) Flow cytometry gating strategy of the markers CD4, CD127, CD45RA, CD25 and forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3). (b) Percentages of CD4+CD25+CD127–regulatory T cells (Tregs) (left) and percentages of CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ Tregs (right); (c) Percentages of CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA+ nTregs (left) and percentages of CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA– eTregs (right); (d) expression patterns of CF25 and inducible T cell co‐stimulator (ICOS) on flow cytometry. (e) Expression of CD25 (left) and percentages of ICOS (right) on total isolated T cells from heparin‐derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in healthy controls and in different CGD subsets.

Tregs from p40phox‐deficient patients expressed elevated levels of Helios and CTLA‐4 (not shown); these markers are associated with regulatory functionality 8, 19. However, this elevation was not seen in the other CGD subtypes, suggesting that it is not a general feature of CGD.

Finally, as a further phenotypical hallmark of Tregs 20, we assessed Tregs positive for glucocorticoid‐induced tumor necrosis factor‐related receptor (GITR) in the blood of CGD patients. No differences were seen between controls and patients, neither in percentage nor in expression level (not shown).

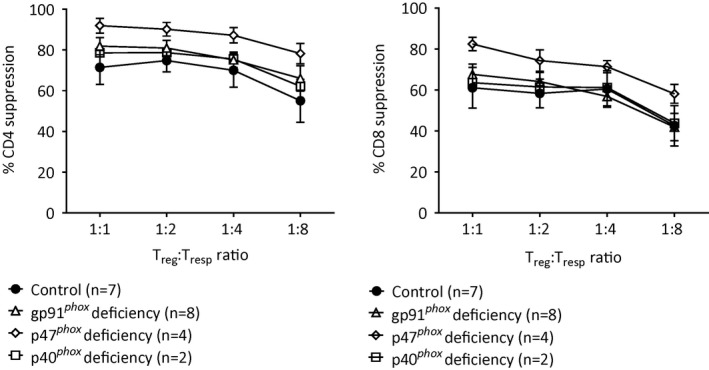

Collectively, there seemed to be no significant differences in Treg numbers in the peripheral blood of CGD patients compared to healthy controls. No clues supporting an important role for Tregs in CGD‐related inflammation were observed, except for the reduced proportion of eTregs in the peripheral blood of gp91phox‐deficient patients. We subsequently isolated and cultured Tregs from the same CGD patients and controls. Tregs from CGD patients yielded similar cell expansion compared to controls after stimulation with antibodies to CD3 and CD28 in the presence of IL‐2 and expression levels of the Treg markers CD25, FoxP3, Helios and CTLA‐4 were comparable to those of healthy controls after culture (not shown). The suppressive capacity of in‐vitro expanded Tregs was assessed by a well‐established in‐vitro CD4 and CD8 suppression assay 16. No differences were observed either between the CGD patients and controls nor between the CGD patients categorized according to the three different CGD subtypes (Fig. 2). As mentioned previously, CGD patients may suffer from very severe autoinflammatory/autoimmune manifestations, including Crohn‐like colitis or severe lung disease 2, 6, 15, 21 as we have also recently demonstrated in p40phox deficiency 22. However, we did not observe any apparent association between individual patients' autoinflammatory/autoimmune manifestations and their Treg numbers (Table 1, Fig. 1a,b), surface markers (Fig. 1c) or suppressive capacities (Fig. 2) at the moment of blood sampling.

Figure 2.

Effector functions of in‐vitro expanded regulatory T cells (Tregs). Functional capacities of regulatory T cells from chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) patients and from healthy controls are shown as their capability to suppress CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Data are in median ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) when n > 3.

Discussion

Several reports suggest a role for ROS in Treg function 7, 12, 13. Details on Treg numbers and activity in CGD patients, who are defective in phagocytic ROS formation, are largely lacking and a role of Tregs in CGD‐related autoinflammation/autoimmunity remains to be examined. In this study we have investigated both Treg numbers in CGD patients as well as their suppressive capacities upon culture ex vivo. Autoinflammatory/autoimmune manifestations may diverge extensively in the CGD patients 15, although in general the p47phox‐deficient patients are the least affected in that sense. If any deficiency in Tregs would underlie the pathogenesis of their clinical manifestations, we were expecting large differences in Treg numbers and/or function between CGD patients and controls. Our recent study of p40phox deficiency has demonstrated extensive autoinflammation/autoimmunity, equal if not more prominent compared to gp91phox‐deficient CGD 22. For this reason, we expected also differences in Tregs within the different CGD subgroups.

In our relatively small but well‐characterized patient cohort we observed a reduction in circulating CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA– eTregs in patients diagnosed with X‐linked (gp91phox‐deficient) CGD. These eTregs are the cells with the most active and suppressive capacities within tissues 8, and considering the high prevalence of inflammation in gp91phox‐deficient CGD patients compared to those deficient for p47phox, this finding could indicate a role for eTregs in the pathophysiology of CGD‐related inflammation. In line herewith, Kraaij et al. observed impaired numbers of FoxP3+ cells upon in‐vitro culture among CD4+CD25+ cells when comparing CGD‐macrophages from five patients to healthy control macrophages in the outgrowth of Tregs upon culture 7. However, it is hard to compare our findings with their results obtained in the past. First, these FoxP3+ cells were not further phenotyped or specified as CD4+CD25+CD127–CD45RA– eTregs. Secondly, Kraaij et al. did also not distinguish between gp91phox‐ and p47phox‐deficient patients. Conversely, significant differences were not detected between controls and p40phox‐deficient patients in our study, while p40phox‐deficient CGD patients exhibit very prominent manifestations of autoinflammation/autoimmunity 22. Even though it is unfortunate that we were only able to examine a small number of p40phox‐deficient patients, our data do not indicate a strong phenotypical difference with healthy controls.

Also, the expression patterns of surface markers associated with Treg activity did not unequivocally support a specific hypothesis regarding the Treg functionality and their possible role in CGD‐related autoinflammation/autoimmunity. For example, CD25 levels were significantly reduced on Tregs from gp91phox‐deficient patients but this was not the case in the similarly affected p40phox‐deficient patients. The general increase in expression of ICOS on Tregs from all CGD groups might reflect a need for these cells to be active in order to mitigate the inflammation present in these patients. When analyzing patients individually, no correlation was observed between expression of these surface markers and inflammatory complications (not shown). Moreover, in‐vitro‐expanded Tregs from CGD patients showed normal cell expansion, normal expression levels of CD25, FoxP3, Helios and CTLA‐4 upon subculture and a normal capacity to inhibit proliferation of co‐cultured responder T cells (Tresp), and in all these functions were similar to control Tregs.

Although it cannot be excluded that the in‐vivo function of Tregs in CGD may be disturbed, our data clearly suggest that CGD‐causing mutations do not appear to cause intrinsic defects in Treg cell functionality. The reduction in eTreg cell numbers in (gp91phox‐deficient) CGD patients is consistent with diminished induction of such cells due to lack of ROS produced by macrophages or with the destabilization of Tregs as a consequence of the presence of inflammatory cytokines, as suggested previously 23. Apart from the reduction in eTreg numbers in gp91phox‐deficient CGD in the blood, no support for a clear role of Tregs in CGD‐related inflammation can be derived from our study.

Disclosures

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

Author contributions

T. W. K. and D. A. designed the study. A. v. d. G, E. C and M. C. S performed the experiments. A. v. d. G and E. C. wrote the manuscript, which was critically read by the other authors.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the patients, their parents and the healthy donors. We also thank Professor Dirk Roos for critically reading this manuscript. This study was supported by Sanquin Blood Supply Product and Process Development Cellular Products Fund (PPOC 1957).

References

- 1. Roos D, de Boer M. Molecular diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 175:139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kang EM, Marciano BE, DeRavin S, Zarember KA, Holland SM, Malech HL. Chronic granulomatous disease: overview and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:1319–26; quiz 27–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rieber N, Hector A, Kuijpers T, Roos D, Hartl D. Current concepts of hyperinflammation in chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:252460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kobayashi SD, Voyich JM, Braughton KR et al Gene expression profiling provides insight into the pathophysiology of chronic granulomatous disease. J Immunol 2004; 172:636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanford AN, Suriano AR, Herche D, Dietzmann K, Sullivan KE. Abnormal apoptosis in chronic granulomatous disease and autoantibody production characteristic of lupus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006; 45:178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenzweig SD. Inflammatory manifestations in chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). J Clin Immunol 2008; 28(Suppl 1):S67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kraaij MD, Savage ND, van der Kooij SW et al Induction of regulatory T cells by macrophages is dependent on production of reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:17686–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cretney E, Kallies A, Nutt SL. Differentiation and function of Foxp3(+) effector regulatory T cells. Trends Immunol 2013; 34:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pociask DA, Sime PJ, Brody AR. Asbestos‐derived reactive oxygen species activate TGF‐beta1. Lab Invest 2004; 84:1013–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Savage ND, de Boer T, Walburg KV et al Human anti‐inflammatory macrophages induce Foxp3+ GITR+ CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress via membrane‐bound TGFbeta‐1. J Immunol 2008; 181:2220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wen Z, Shimojima Y, Shirai T et al NADPH oxidase deficiency underlies dysfunction of aged CD8+ Tregs. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:1953–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berger CT, Hess C. Neglected for too long? ‐ CD8+ Tregs release NOX2‐loaded vesicles to inhibit CD4+ T cells. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:1646–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Efimova O, Szankasi P, Kelley TW. Ncf1 (p47phox) is essential for direct regulatory T cell mediated suppression of CD4+ effector T cells. PLoS ONE 2011; 6:e16013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwon BI, Kim TW, Shin K et al Enhanced Th2 cell differentiation and function in the absence of Nox2. Allergy 2017; 72:252–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magnani A, Brosselin P, Beaute J et al Inflammatory manifestations in a single‐center cohort of patients with chronic granulomatous disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:655–62.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Leeuwen EM, Cuadrado E, Gerrits AM, Witteveen E, de Bree GJ. Treatment of intracerebral lesions with abatacept in a CTLA4‐haploinsufficient patient. J Clin Immunol 2018; 38:464–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chinen T, Kannan AK, Levine AG et al An essential role for the IL‐2 receptor in Treg cell function. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:1322–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vocanson M, Rozieres A, Hennino A et al Inducible costimulator (ICOS) is a marker for highly suppressive antigen‐specific T cells sharing features of TH17/TH1 and regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:280–9, 9.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Takatori H, Kawashima H, Matsuki A et al Helios Enhances Treg Cell Function in Cooperation With FoxP3. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67:1491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ronchetti S, Ricci E, Petrillo MG et al Glucocorticoid‐induced tumour necrosis factor receptor‐related protein: a key marker of functional regulatory T cells. J Immunol Res 2015; 2015:171520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuijpers T, Lutter R. Inflammation and repeated infections in CGD: two sides of a coin. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012; 69:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van de Geer A, Nieto‐Patlan A, Kuhns DB et al Inherited p40phox deficiency differs from classic chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest 2018; 128:3957–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Overacre‐Delgoffe AE, Chikina M, Dadey RE et al Interferon‐gamma Drives Treg Fragility to Promote Anti‐tumor Immunity. Cell 2017; 169:1130–41.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]