Abstract

Background: Knee joint pain is the most common reason for physical disability which associates with age. TamaFlexTM (NXT15906F6) is a synergistic anti-inflammatory formulation which contains ethanol/aqueous extracts of Tamarindus indica seeds and ethanol extract of Curcuma longa rhizome.

Methods: In a 90-day randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, we evaluated efficacy of NXT15906F6 in relieving pain and improving joint function in non-arthritic adults. Ninety non-arthritic subjects who experienced knee pain and joint discomfort following a six-minute walk test (SMWT) and Stair climb test (SCT) participated in the present trial. Subjects received either 250 mg (n=30) or 400 mg (n=30) of NXT15906F6 or matched placebo (PL: n=30) daily for 90 days. Improvement from baseline six-minute walk distance (SMWD) in NXT15906F6 groups, compared with placebo (PL) was the primary outcome of the study.

Results: At post-intervention, subjects in NXT15906F6-250 (p<0.001) and NXT15906F6-400 (p<0.0001) groups showed substantial improvements in mean changes of SMWD from baseline compared to placebo. The 250 mg and 400 mg NXT15906F6 groups also improved average walking speed from baseline by 0.08±0.07 m/s (p=0.0010) and 0.11±0.08 m/s (p<0.0001), respectively. The NXT15906F6 groups experienced significant improvement in SMWT performances as early as 14 days. NXT15906F6-supplemented participants showed a consistent benefit of pain relief and improved musculoskeletal functions, compared to placebo.

Conclusion: NXT15906F6 provided substantial relief from knee pain after physical activity and improved joint function in non-arthritic adults. Study participants did not show any major adverse events, and they tolerated well this novel herbal formulation.

Keywords: Knee joint pain, Musculoskeletal function, NXT15906F6, Six-minute walk test

Introduction

Knee joint pain is the most common musculoskeletal pain in older adults. Frequent knee pain limits daily activities such as walking, climbing, cycling; thereby increases physical disability and reduces quality of life. Globally, around 30% of older adults experience knee pain 1,2. In particular, knee joints bear the major part of body weight, support mobility, and balance; they are susceptible to 'wear and tear' and are at high risk of articular cartilage damage 3. During physical activity or joint movements, perception of knee pain is indicative of the deteriorating status of articular cartilage 4,5.

Currently, the pharmacological approach of joint pain management is use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, and acetaminophen 6. These synthetic cyclooxygenase inhibitors help in pain management of osteoarthritis (OA) for short-term 6,7. However, their long-term use increases risk of gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding, atherosclerosis, hypertension and kidney disease 8-10. Therefore, safer and effective knee pain management strategies are warranted to improve knee joint health of elderly adults.

Consumers are showing increasing interest in natural therapies, in that they offer safe and effective support in inflammation and pain. Botanical polyphenolic constituents are effective inhibitors of pro-inflammatory enzymes, thus prevent formation of toxic cytokines generated through inflammatory reactions 2. Unlike synthetic COX-inhibitors, these botanicals generally have a centuries-long track record of safe use in food products 11.

Tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica L., Fabaceae) is a vital plant source for food materials. The fruit pulp is used in various food preparations in Asian countries and also the roasted seed kernel is eaten 12. Tamarind seed kernels have high antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Traditionally, it is used in various ailments such as chronic diarrhea, dysentery, jaundice, diabetes, ulcer, and wound healing 13. A recent preclinical study demonstrated that T. indica seed extract improved inflammatory arthritic symptoms in Freund's Complement Adjuvant induced rats 14.

Curcuma longa (Curcuma longa L., Zingiberaceae) or turmeric is a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial plant. Its rhizomes are a rich source of the group of polyphenols, termed curcuminoids. Traditionally, turmeric is a popular spice, being a coloring agent and preservative in Asian cuisines. In Ayurveda, the traditional Indian medicine, turmeric paste has been used to treat common infections, inflammations and wound healing 15. Curcumin, the major active ingredient in turmeric, is a potent anti-inflammatory agent, acting via inhibiting TNFα dependent NF-ĸB activation 16. Curcumin down-regulates inducible cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme expression and inhibits pro-inflammatory 5-Lipoxygenase production 17,18. Recently, a meta-analysis concluded that standardized turmeric extracts alleviated joint pain and inflammation-related symptoms associated with arthritis 19.

NXT15906F6 or TamaFlexTM is a botanical formula containing ethanol and aqueous extracts of Tamarindus indica seeds combined with an ethanol extract of Curcuma longa rhizome. NXT15906F6 is standardized to contain not less than 65% of proanthocyanidins and 3% of total curcuminoids 20. It represents a new category of a food-derived synergistic anti-inflammatory composition primarily intended for the healthy aging population with an active lifestyle. In a previous study, a repeated-dose 90-day subchronic study in Wistar rats demonstrated that NXT15906F6 was safe for oral consumption 20. This study also showed that this herbal blend was nonmutagenic and nonclastogenic in the Ames bacterial reverse mutation test and mouse bone-marrow erythrocyte micronucleus test, respectively 20. Further, a number of observations from in vitro cell based experiments and a preclinical model of monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)-induced osteoarthritis in Sprague Dawley rats showed that NXT15906F6 acts as a synergistic anti-inflammatory herbal composition to reduce pain and osteoarthritis symptoms (data not presented, to be published separately). Therefore we hypothesized that this food-derived synergistic anti-inflammatory formulation might alleviate joint pain and improve joint function in human adults.

Here, we present a ninety-day, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to demonstrate the efficacy of NXT15906F6 (TamaFlexTM) in relieving knee joint discomfort and improving joint function in non-arthritic adults following a session of physical activity. Also, this study evaluates tolerability of this herbal composition.

Materials and methods

Study Material

NXT15906F6 (TamaFlexTM) is an herbal composition containing extracts of Tamarindus indica seeds and Curcuma longa rhizomes. The methods of preparation and standardization of the individual herbal extracts have been described earlier 20. NXT15906F6 contains six parts (w/w) T. indica seed extract, 3 (w/w) parts C. longa rhizome extract and 1 part excipients. The excipient portion was a combination of 80% (w/w) microcrystalline cellulose powder and 20% (w/w) Syloid silica. NXT15906F6 was standardized to contain a minimum 65% of proanthocyanidins and 3% of total curcuminoids 20.

Clinical study design

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial assessed the efficacy and tolerability of NXT15906F6 in non-arthritic adult subjects who experienced knee pain following physical exertion. This study took place at two sites (Andhra Hospital and Sravani Hospital) in Andhra Pradesh, India following the ICH-GCP guidelines. The study protocol and related documents were reviewed and approved by the Institutional ethics committees of both sites (ECR/198/Inst/AP/2013 and ECR/693/Inst/AP/2014). The study protocol was registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI/2016/02/006682). All participants gave written consents before the commencement of the study related activities. The participants were selected through inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included: (i) physically active male and female subjects of age between 35 and 70 years with a Body Mass Index (BMI) between 18 and 29 kg/m2, (ii) no knee pain or discomfort at rest, but an experience of mild-to-moderate pain in knee joint upon completion of a Six-Minute walk test (SMWT), (iii) non-osteoarthritic subjects who had Kellgren-Lawrence grade 0 in the radiographic analysis, (iv) female subjects were of either post-menopausal or used a contraceptive method during the intervention, (v) subjects willing to refrain from taking any additional pain relievers such as ibuprofen, aspirin or other NSAIDs other than the prescribed rescue medication, if needed, during the study. Exclusion criteria included: (i) history of any arthritic condition, joint disorders, arthropathy, knee or hip joint replacement surgery, any physical disability, previous major injury or disease that could interfere with their functional performances, (ii) consumption of alcohol or recreational drugs or a history of using immunosuppressive medicines or intra-articular treatment/injections with corticosteroid or hyaluronic acid or glucosamine along with chondroitin supplements or any analgesics, (iii) female subjects, who were either pregnant or lactating or planning to become pregnant, (iv) history of any clinical presentations pertaining to hematological, renal, endocrine, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hepatic, neurologic diseases, or malignancies, hypothyroidism.

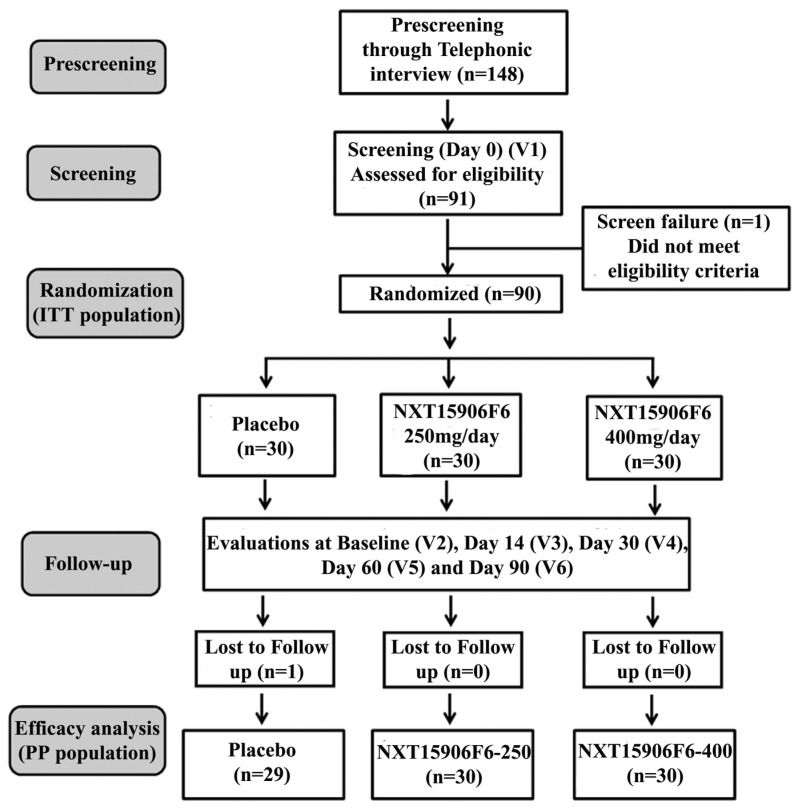

Participants were randomized into three groups viz., placebo, NXT15906F6 250 mg, and NXT15906F6 400 mg; each group contained thirty subjects; 15 males and 15 females. Participants received either placebo or NXT15906F6 125 mg or 200 mg capsules twice daily (one before breakfast and one before dinner). Placebo capsules contained excipients MCCP and Syloid. All capsules were identical in physical appearance. The study consisted of six visits, visit 1(screening visit), visit 2 or baseline (randomization visit), visit 3 (first follow up at day 14), visit 4 (second follow up at day 30), Visit 5 (third follow up at day 60) and visit 6 (final visit at day 90). The study design, in brief, is presented in a CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of the trial process.V1-V6 indicates Visit 1 to Visit 6 of the study schedule.

Clinical efficacy assessments

The study primarily evaluated efficacy of NXT15906F6 improving joint function and alleviating joint pain developed following exercise in non-arthritic subjects. Improvement in six-minute walk test (SMWT) score from baseline was the primary endpoint of the study. Other assessments such as Stair climb test (SCT), Visual analog scale (VAS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) Index and primary knee flexion were the secondary efficacy measures of the study.

Six-minute walk test (SMWT) is to assess subjects' walking ability and also evaluates their endurance level. This test is being used as a functional outcome measure for knee function of OA subjects, per recommendation by the American College of Rheumatology 21. The participants performed the SMWT on a 25-meter section of a well-ventilated, quiet, and flat surface, according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society 22. Participants walked as quickly as possible for six minutes to cover the maximum ground distance along the demarcated space. Rest periods were allowed but included in time. Participants did not carry a watch; the study monitors verbally encouraged them at minute intervals during the test. Study monitors terminated the assessment if a participant reported chest pain or extreme shortness of breath or leg cramps or other discomforts. Earlier, the reliability of SMWT to evaluate the knee function of OA subjects was validated in the Indian population 23.

Stair climb test (SCT) was conducted based on the ACR guidelines to evaluate knee function, lower body strength and balance 24. Each participant was instructed to ascend and descend through stairs of nine steps with 20 cm step height. The study permitted use of handrail or walking aid during the SCT. The participants were allowed to stop or rest if needed, but the timing was on. The study monitor recorded time (in seconds) taken to ascend and descend flight of stairs.

Questionnaire-based assessments of pain, stiffness and physical function were evaluated using Visual Analog Scale (VAS) 25, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) Index 26. Total WOMAC index consisted of 24 questions, divided into three sub-scales - WOMAC-A (Pain), WOMAC-B (Stiffness) and WOMAC-C (Physical functioning) subscales comprised of 5, 2 and 17 questions, respectively 26.

Flexion in the primarily affected knee or primary knee flexion was measured using a Goniometer (Global Medical Devices, Pune, India) 27. Briefly, subjects were asked to flex the knee joint (actively or passively). The assessor adjusted the movable arm of the goniometer along with the moving lower leg, the difference between the angles of the knee joint at fully extended and flexion positions recorded as knee flexion - the range of angular motion of the knee joint expressed in degrees (o).

Safety assessments

As part of the safety assessment of NXT15906F6, a battery of hematological, serum biochemical parameters and urine analyses were evaluated at screening and the end of the study. Besides, the study monitors recorded the participants' vital signs at all visits in the study duration. Serum biochemical parameters and hematological parameters were measured using an automated analyzer (Siemens Dimension Xpand Plus, NY, USA) and a hematological counter (Coulter LH-750, Beckman Coulter Inc., IN, USA). Urine analysis was carried out using Urine analysis kit (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA). Microscopic examinations were performed using a clinical light microscope (Olympus Opto Systems India Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India). Table 1 represents a list of vital signs recorded and parameters analyzed in blood and urine samples of the study subjects.

Table 1.

List of parameters evaluated as part of safety and tolerability of NXT15906F6

| Hematology |

| • Hemoglobin • Platelet count • Total leukocyte count • Red blood cells • ESR • Differential count |

| Biochemistry |

| • Blood glucose (Random) • Serum creatinine • Blood uric acid • Blood urea nitrogen • Serum bilirubin • SGOT • SGPT • Serum alkaline phosphatase • Serum sodium, potassium • Serum albumin |

| Urine Analysis |

| • Routine urine analysis (Color, Sp. Gravity, pH, glucose, protein, RBC) |

| Vital Signs |

| • Blood pressure • Pulse rate • Respiratory rate • Oral temperature |

Rescue medication

Subjects were allowed a maximum of 2000 mg/day Paracetamol as rescue analgesia during the study, based on pain severity reported to the study physician. Participants were advised not to take rescue medication at least three days before each evaluation. No other pain-relieving interventions were allowed during the study period. Use of rescue medication by individual participant, if any, was recorded appropriately in the subject's diary card.

Statistical analysis

The power analysis estimated that at least 25 subjects in each arm could provide a power of 90% to detect a treatment effect in the primary efficacy variable at a two-sided significance level of 0.025%. In sample size calculation, assumptions on the mean difference and a common standard deviation were 2.5 and 2.4, respectively. Analyses on per-protocol (PP) and intention-to-treat (ITT) populations presented efficacy and safety of NXT15906F6, respectively. The primary outcome measure was evaluation of mean change from baseline scores in placebo vs. treatment groups using ANCOVA. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Description of the study participants

Ninety non-arthritic subjects (45 men and 45 women) participated in the present study. Each group contained an equal number of males and females. Eighty-nine participants completed the ninety-day intervention. Participants had no clinical symptoms of osteoarthritis and scored 0 at Kellgren-Lawrence grading scale. They developed mild to a moderate knee joint pain following a Six-Minute walk test (SMWT) and Stair Climb Test (SCT). Average ages with standard deviations of the per protocol populations in Placebo (PL, n=29), NXT15906F6 250 mg (NXT15906F6-250, n=30) and NXT15906F6 400 mg (NXT15906F6-400, n=30) groups were 45.3±8.5, 43.7±6.7 and 45.1±7.9 years, respectively. Table 2 summarizes baseline characteristics of participants.

Table 2.

Demography and baseline characteristics: Per protocol population

| Parameters | Placebo (n=29) | NXT15906F6-250 (n=30) | NXT15906F6-400 (n=30) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 8.5 | 43.7 ± 6.7 | 45.1 ± 7.9 | 0.4134# 0.9095* |

| Male, n (%) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (50.0) | 15 (50.0) | - |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (51.7) | 15 (50.0) | 15 (50.0) | - |

| Weight (kg) | 63.4 ± 8.2 | 62.4 ± 6.4 | 63.1 ± 8.9 | 0.5943# 0.8942* |

| Height (m) | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6842# 0.5023* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 2.5 | 23.4 ± 2.1 | 23.4 ± 2.4 | 0.3345# 0.3689* |

| SMWD (m) | 391.41±37.71 | 397.13±68.06 | 401.77±51.64 | 0.6903# 0.3820* |

| Average Speed (m/s) | 1.09±0.10 | 1.10±0.19 | 1.12±0.14 | 0.6903# 0.3820* |

| Stair climb test (s) | 11.01±2.1 | 11.33±2.36 | 11.14±1.91 | 0.5919# 0.8149* |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | 13.33±4.14 | 13.07±3.22 | 13.40±2.77 | 0.7943# 0.9314* |

| WOMAC-A (pain) | 55.86±19.41 | 56.83±15.17 | 55.67±13.50 | 0.8316# 0.9644* |

| WOMAC-B (Stiffness) | 23.79±7.87 | 23.50±9.02 | 22.67±7.85 | 0.8945# 0.5841* |

| WOMAC-C (Physical function) | 193.28±66.86 | 190.67±48.04 | 191.33±33.40 | 0.8644# 0.8890* |

| Total WOMAC | 272.93±86.6 | 271.00±62.21 | 269.67±42.79 | 0.9222# 0.8560* |

| Primary knee flexion (degrees) | 122.21±4.7 | 121.97±5.59 | 122.13±7.00 | 0.8587# 0.9623* |

Data presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. # intergroup analysis placebo vs. NXT15906F6-250; * placebo vs. NXT15906F6-400 using t-test, unequal variance

Clinical efficacy of NXT15906F6

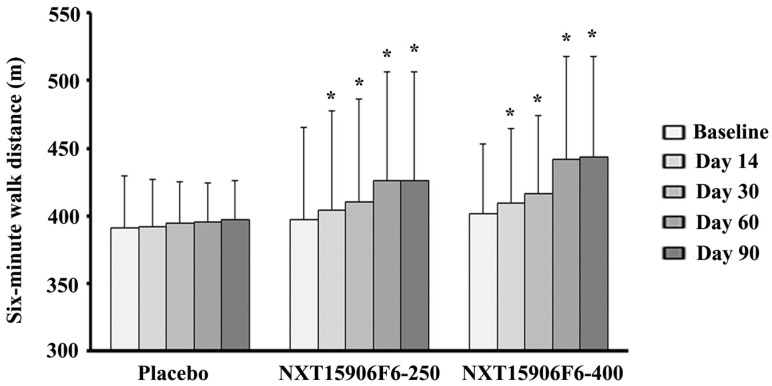

Table 3 presents changes from baseline six-minutes walk distance (SMWD) in NXT15906F6 supplemented groups in comparison with the changes in placebo. At post-intervention, the inter-group analysis between mean differences of baseline SMWD showed that NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects walked significantly greater distance in six-minute test (p<0.001; NXT15906F6-250: 29.23±25.68 m vs. PL: 5.55±24.59 m) and (p<0.0001; NXT15906F6-400: 41.83±28.16 m vs. PL: 5.55±24.59 m). Also, active groups showed significant improvements in SMWD from baseline as early as 14 days of supplementation, in comparison with placebo. Subjects in both 250 and 400 mg NXT15906F6 groups walked 7.43±7.95 m (p=0.0011) and 7.80±5.26 m (p=0.0008) greater distances from baseline; in contrast, placebo treated subjects improved only 0.90±8.67 m distance in SMWT, after 14 days of supplementation (Table 3). Both groups of NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects showed gradual improvements of SMWD from baseline throughout the study duration (Figure 2). Intra-group analyses revealed that NXT15906F6-250 (404.57±73.14 m vs. 397.13±68.06 m; p<0.0001) and NXT15906F6-400 (409.57±54.72 m vs. 401.77±51.64 m; p<0.0001) groups showed substantial improvements in SMWD from baseline as early as 14 days. At the end of the trial, placebo treated subjects showed no improvement in SMWD from baseline (396.97±29.43 m vs. 391.41±37.71 m; p=0.1978) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Comparison between the mean changes of SMWT outcome from baseline in NXT15906F6 supplemented groups with placebo

| Change (Mean±SD) from baseline at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 (P value*) | Day 30 (P value*) | Day 60 (P value*) | Day 90 (P value*) | |

| Distance traveled (m) | ||||

| Placebo(n=29) | 0.90±8.67 | 2.72±10.70 | 3.83±23.91 | 5.55±24.59 |

| NXT15906F6-250 (n=30) | 7.43±7.95 (0.0011) | 13.40±12.86 (0.0004) | 28.50±27.01 (0.0009) | 29.23±25.68 (0.0009) |

| NXT15906F6-400 (n=30) | 7.80±5.26 (0.0008) | 14.40±9.45 (0.0002) | 39.93±30.70 (<0.0001) | 41.83±28.16 (<0.0001) |

| Average speed (m/s) | ||||

| Placebo(n=29) | 0.00±0.02 | 0.01±0.03 | 0.01±0.07 | 0.02±0.07 |

| NXT15906F6-250 (n=30) | 0.02±0.02 (0.0018) | 0.04± 0.04 (0.0003) | 0.08±0.07 (0.0008) | 0.08±0.07 (0.0010) |

| NXT15906F6-400 (n=30) | 0.02±0.02 (0.0026) | 0.04±0.03 (0.0003) | 0.11±0.09 (<0.0001) | 0.11±0.08 (<0.0001) |

*Values in parentheses represent p-values for differences in changes from baseline among the active groups vs. placebo using ANCOVA.

Figure 2.

Gradual improvements of six-minute walk distance (SMWD) in NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects during the study. The bars represent the mean ± SD of walked distance in meters (m). Placebo (n=29), NXT15906F6-250 (n=30), and NXT15906F6-400 (n=30); * indicates significance p<0.0001; intragroup comparison between baseline and the respective days of evaluations using t-test.

Besides, average walking speed of NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects from baseline also increased significantly, compared to placebo. At the end of the intervention, average walking speed was improved by 0.08±0.07 m/s (p=0.0010; vs. 0.02±0.07m/s placebo) in NXT15906F6-250 and 0.11±0.08 m/s (<0.0001; vs. 0.02±0.07m/s placebo) in NXT15906F6-400, from baseline. Early improvements in average walking speed of the NXT15906F6 supplemented participants were substantial after 14 days, compared to placebo (Table 3).

In comparison to placebo, baseline changes of all secondary outcome parameters in NXT15906F6 supplemented groups also exhibited significant improvements at the end of intervention (Table 4). In Stair Climb Test (SCT), reduction of time taken by participants to ascend and descend stairs considered as an efficacy measure. At the end of the intervention, time taken by the 250 and 400 mg of NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects were reduced by 2.27±1.46 s (p<0.0001; vs. 0.30±1.01 s. placebo) and 2.40±1.28 s (p<0.0001; vs. 0.30±1.01 s. in placebo) from baseline, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Intergroup comparison between changes from baseline at the end of the Study

| Parameters | Placebo (n=29) | NXT15906F6- 250 (n=30) | NXT15906F6- 400 (n=30) | *p value between mean changes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Placebo vs. NXT15906F6- 250 | Placebo vs. NXT15906F6- 400 | |

| Stair climbing time (s) | 0.30±1.01 | -2.27 ±1.46 | -2.40 ±1.28 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) Score | -1.38±1.85 | -4.19±2.44 | -6.21±2.06 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| WOMAC-A (pain) score | -6.21±9.42 | -16.33±15.14 | -23.83±8.97 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| WOMAC-B (Stiffness) score | 0.86±5.36 | -6.17±8.97 | -9.17±7.78 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| WOMAC-C (Physical function) scores | -12.93±18.20 | -39.00±29.81 | -70.17±31.25 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Total WOMAC score | -18.28±28.98 | -61.50±49.10 | -103.17±39.49 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Primary knee flexion (degrees) | 1.03±1.45 | 3.43±1.61 | 5.30±1.29 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Data presented as mean±SD, *p-value, the comparison between the mean change of baseline scores placebo and mean changes from baseline scores in NXT15906F6 groups at day 90 are analyzed using an ANCOVA model.

After 90 days supplementation, NXT15906F6 groups showed substantial reductions of baseline VAS scores, compared with placebo. The intergroup comparison revealed that changes from baseline VAS scores in 250 mg (4.19±2.44 vs. 1.38±1.85 placebo) and 400 mg (6.21±2.06 vs. 1.38±1.85 placebo) NXT15906F6 groups were highly significant (<0.0001) (Table 4).

Baseline WOMAC subset scores, i.e., pain, stiffness, and physical function scores significantly improved in the NXT15906F6 supplemented groups, at the end of the study (Table 4). Overall, NXT15906F6-250 (p<0.0001; 61.50±49.10 vs. 18.28±28.98 placebo) and NXT15906F6-400 (p<0.0001; 103.17±39.49 vs. 18.28±28.98 placebo) groups showed significant improvements in total WOMAC scores from baseline (Table 4).

Primary knee flexion parameter measures the angular movement of the affected knee. Improvements from baseline primary knee flexion in NXT15906F6-250 and NXT15906F6-400 groups were 3.43o±1.61 (p<0.0001; vs. 1.03o±1.45 placebo) and 5.30o±1.29 (p<0.0001; vs. 1.03o±1.45 placebo), respectively. At the end of the study, low and high dose of NXT15906F6- supplemented groups showed 2.81% and 4.34% improvement in primary knee flexion from baseline. In contrast, the placebo group only showed 0.82% improvement (Table 4).

It is interesting to note that NXT15906F6 supplementation also significantly improved other secondary efficacy variables such as SCT, VAS, WOMAC, and primary knee flexion as early as 14 days (Table 5).

Table 5.

Intergroup comparison between changes from baseline at 14 day of the study

| Parameters | Placebo (n=29) | NXT15906F6- 250 (n=30) | NXT15906F6- 400 (n=30) | *p value between mean changes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Placebo vs. NXT15906F6- 250 | Placebo vs. NXT15906F6- 400 | |

| Stair climbing time (s) | 0.21±0.82 | -1.75±1.28 | -1.87±0.92 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) Score | -0.27±0.84 | -1.17±1.10 | -1.40±1.05 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| WOMAC-A (pain) score | -0.86±5.36 | -5.83±6.17 | -5.83±4.56 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| WOMAC-B (Stiffness) score | 0.69±5.30 | -2.17±5.52 | -1.67±4.01 | 0.0069 | 0.0119 |

| WOMAC-C (Physical functioning)scores | -4.14±14.82 | -12.17±16.49 | -11.33±9.09 | 0.0070 | 0.0160 |

| Total WOMAC score | -3.97±19.24 | -20.17±23.83 | -18.83±14.24 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 |

| Primary knee flexion (degrees) | 0.24±0.51 | 0.50±0.90 | 0.67±0.96 | 0.2158 | 0.0351 |

Data presented as mean±SD, *Comparison between mean change from baseline scores in the placebo and mean changes from baseline scores in NXT15906F6 groups at day 14 are analyzed using an ANCOVA model.

Safety evaluations

The study measured serum biochemistry and hematological parameters at the screening visit and at the end of the study. Parameters tested in serum biochemistry, hematology, urine analysis, and vital signs are listed in Table 1. Routine laboratory tests results were within normal range and did not show any significant changes at the end of the intervention from baseline (data not shown). Additionally, vital signs and urine analyses parameters were within the normal range throughout the trial (data not shown).

Adverse events, dropouts and use of rescue medication

During the intervention period, few participants reported some minor adverse events such as indigestion, vomiting, headache, common cold, cough, fever, body pain (Table 6). Nine subjects from placebo; four and two subjects from the NXT15906F6-250 and NXT15906F6-400 groups, respectively reported adverse events during intervention (Table 6).

Table 6.

Adverse events: Number of subjects reported adverse events in the study groups

| Adverse events | Placebo (n=29) | NXT15906F6 250 mg (n=30) | NXT15906F6 400 mg (n=30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indigestion | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| Vomiting | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| Headache | 02 | 00 | 00 |

| Common cold | 04 | 02 | 01 |

| Cough | 00 | 01 | 00 |

| Fever | 00 | 01 | 01 |

| Body pain | 01 | 00 | 00 |

| Total no. of subjects (group wise) | 09 | 04 | 02 |

Only one participant in the placebo group did not appear at follow-up visits, starting from day 14 of the study. All participants in the active groups completed the study. Overall, the number of participants who completed the study was 29, 30 and 30 in the placebo, NXT15906F6-250, and NXT15906F6-400 groups, respectively. None of the subjects in any group used the rescue medication during the intervention.

Discussion

The present clinical study shows that an anti-inflammatory herbal composition NXT15906F6 (TamaFlexTM) alleviates knee joint pain and improves joint function in non-arthritic adults, as measured by standardized methods of physical exertion such as SMWT and SCT. NXT15906F6 represents a new class of a food-derived synergistic anti-inflammatory composition intended primarily for the healthy aging population and also for the people with an active lifestyle. Cell based studies demonstrated that NXT15906F6 inhibits TNFα production and downregulates key inflammatory pain modulators, e.g. PGE2 and LTB4 in human blood derived immune cells. In addition, NXT15906F6 also scavenges reactive oxygen species by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity in the human monocytic cells in vitro thereby exhibiting potential antioxidant activity (unpublished data). Taken together, NXT15906F6 is a distinct food supplement, different from other anti-inflammatory botanical compositions because it alleviates chronic inflammation and associated pain without disturbing physiology of individuals.

Age-related musculoskeletal dysfunctions such as joint pain and discomfort are steadily increasing and seriously affecting physical activities of millions of people globally 1,2. As knees are the most affected joints, people suffer from knee pain and joint discomfort as age advances. Earlier studies have demonstrated that knee pain and joint discomfort adversely affect physical activity in healthy as well as in OA subjects 28-30. Severity of knee pain also negatively influences body balance control via poor neuromuscular coordination in older adults, thus increases risk of falling and fall-related injuries 31-33. Together, knee pain and joint discomfort restricts physical movement, reduces various activities of daily living (ADLs) and increases associated health risks in healthy or non-arthritic aging adults.

The SMWT is a simple, validated and reliable physical test to evaluate improvement in musculoskeletal functions 24,34. SMWT measures submaximal functional performance 35 and assesses a senior person's fitness as part of the LifeSpan Wellness Program 36. The present trial showed that ninety days supplementation of NXT15906F6 significantly improved SMWT scores from baseline, in comparison with placebo. Besides, it is also interesting to note that NXT15906F6 supplemented subjects experienced an early benefit of improved musculoskeletal functions in 14 days. These observations indicate that NXT15906F6 improves physical function in non-arthritic adult subjects. Earlier studies suggested a strong correlation between SMWT scores and self-reported WOMAC physical function subscale in knee OA subjects 37,38. The present study also shows that NXT15906F6 supplementation significantly improves baseline WOMAC function scores in non-arthritic adults, in agreement with these previous reports.

During daily activities such as walking on a flat surface or climbing stairs, knee pain adversely affects movement of OA subjects or even in non-arthritic adults. Also, perception of musculoskeletal pain is a major psycho-physiological limiting factor for avoiding routine daily activities 39,40. In our study, NXT15906F6 significantly reduced baseline VAS and WOMAC pain scores in comparison with placebo. These observations suggest that NXT15906F6 has potential in alleviating knee pain that occurs following physical activity and therefore, can enhance overall performance. Besides, significant improvements in the Stair climb test (SCT) and WOMAC-function subscale baseline scores further strengthen the efficacy of NXT15906F6 in pain alleviation and improved joint function in the study population.

Furthermore, an interesting observation in this study was that NXT15906F6 significantly increased baseline knee flexibility. Degree of joint flexibility influences physical movements or locomotor activities of elder subjects or OA subjects. Earlier studies demonstrated that reduced flexion or range of motion of hip and knee joints is a crucial factor for reduced locomotor activities such as walking, climbing stairs, and daily activities 27,41.

In addition to efficacy, an interesting attribute of NXT15906F6 is that the components are of food origin and the proprietary blend is safe for human consumption 20. T. indica seeds and C. longa rhizome have a long history of human consumption 12,15. A series of broad-spectrum safety studies including a 90-day sub-chronic toxicological study in Wistar rats and genotoxicity studies have further confirmed that the standardized composition NXT15906F6 is safe for human consumption 20. In corroboration, the present clinical study also reveals that NXT15906F6 supplementation for ninety days does not yield any serious adverse events. Furthermore, no significant changes in vital signs, routine examinations on hematology, serum biochemistry and urine were evident in the study subjects. Together, these observations confirm that NXT15906F6 is safe and tolerable for human consumption.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that the food derived anti-inflammatory herbal composition NXT15906F6 (TamaFlexTM) alleviates knee pain in non-arthritic adults after physical activity. Besides, NXT15906F6 also improves knee joint function which further helps increasing the subjects' physical activities. Finally, NXT15906F6 is tolerable and safe for human consumption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NXT CAP, Ltd., Cyprus for providing the study product. The authors thank study coordinators and study team at Andhra hospital and Sravani hospital for their contributions in smooth conduct of the study. The authors also thank the team of B10 Analytics Pvt. Ltd, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India for statistical analyses of the data.

Funding

NXT CAP, Ltd, Cyprus, and NXT USA, Inc., USA provided the financial support for the research.

References

- 1.Peat G, McCarney R, Croft P. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in older adults: a review of community burden and current use of primary health care. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:91–97. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Reilly S. Occupation and knee pain: a community based study. Osteoarthritis Cart. 2000;8:78–81. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toda Y, Tsukimura N. A six-month follow up of a randomized trial comparing the efficacy of a lateral-wedge insole with subtalar strapping and an in-shoe lateral-wedge insole in patients with varus deformity osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3129–3136. doi: 10.1002/art.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holden MA, Nicholls EE, Young J. et al. Role of exercise for knee pain: what do older adults in the community think? Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1554–1564. doi: 10.1002/acr.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendry M, Williams NH, Markland D. et al. Why should we exercise when our knees hurt? A qualitative study of primary care patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Fam Pract. 2006;23:558–567. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conaghan PG, Dickson J, Grant RL. Care and management of osteoarthritis in adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;336:502–503. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.608009.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter DJ. Pharmacologic therapy for osteoarthritis- the era of disease modification. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:13–22. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai SP, Solomon DH, Abramson SB. American College of Rheumatology Adhoc group on use of selective and non-selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Recommendations for use of selective and nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an American College of Rheumatology white paper. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1058–1073. doi: 10.1002/art.23929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B. et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2017;357:j1909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Lorenzo C, Dell'Agli M, Badea M. et al. Plant food supplements with anti-inflammatory properties: a systematic review (II) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53:507–516. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.691916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caluwé ED, Halamová K, Damme PV. Tamarindus indica L.- A review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Afrika Focus. 2010;23:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemshekhar M, Kemparaju K, Girish KS. Preedy VR, Watson R, Patel VB, eds. Nuts & Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention, London: Academic Press; 2011. Tamarind (Tamarindus indica) seeds: an overview on remedial qualities; pp. 1107–1114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundaram MS, Hemshekhar M, Santhosh MS. et al. Tamarind seed (Tamarindus indica) extract ameliorates adjuvant-induced arthritis via regulating the mediators of cartilage/bone degeneration, inflammation and oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11117. doi: 10.1038/srep11117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur RS, Puri HS, Husain A. Major medicinal plants of India. Lucknow, India: Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatcher H, Planalp R, Cho J. et al. Curcumin: From ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1631–1652. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7452-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan X, Poulose EM, Raveendran VV. et al. Regulation of the expression of cyclooxygenases and production of prostaglandin I₂ and E₂ in human coronary artery endothelial cells by curcumin. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thangapazham R, Sharma A, Maheshwari RK. Multiple molecular targets in cancer chemoprevention by curcumin. AAPS J. 2006;8:E443–449. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daily JW, Yang M, Park S. Efficacy of turmeric extracts and curcumin for alleviating the symptoms of joint arthritis: A Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Med Food. 2016;19:717–729. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2016.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badmaev V, Vik H, Stohs SJ. et al. Safety and toxicological evaluation of NXT15906F6 (TamaFlex): A food-derived botanical composition containing standardized extracts of Tamarindus indica seeds and Curcuma longa rhizomes. Toxicol Res App. 2018;2:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)- American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Guidelines. Accessed on Sept 05, 2015. http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Rheumatologist/Research/Clinician-Researchers/Six-Minute-Walk-Test-SMWT.

- 22.ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ateef M, Kulandaivelan S, Tahseen S. Test-retest reliability and correlates of 6-minute walk test in patients with primary osteoarthritis of knees. Indian J Rheumatol. 2016;11:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennell K, Dobson F, Hinman R. Measures of Physical Performance Assessments. Arthritis Care & Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Supp 11):S350–S370. doi: 10.1002/acr.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman CR, Casey KL, Dubner R. et al. Pain measurement: an overview. Pain. 1985;22:1–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellamy N, Buchnan WW, Goldsmith CH. et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to anti-rheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steultjens MPM, Dekker J, Van Baar ME. et al. Range of joint motion and disability in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:955–961. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.9.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feinglass J, Thompson JA, He XZ. et al. Effect of physical activity on functional status among older middle-age adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:879–885. doi: 10.1002/art.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vignon É, Valat J, Rossignol M. et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee and hip and activity: a systematic international review and synthesis (OASIS) Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosemann T, Kuehlein T, Laux G. et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: a comparison of factors associated with physical activity. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1811–1817. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valeriani M, Restuccia D, Di Lazzaro V. et al. Inhibition of the human primary motor area by painful heat stimulation of the skin. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1475–1480. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swensson P, Miles TS, Graven-Nielsen T. et al. Modulation of stretch evoked reflexes in single motor units in the human masseter muscle by experimental pain. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s002210000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lajoie Y, Gallagher S. Predicting falls within the elderly community: comparison of postural sway, reaction time, the Berg balance scale and the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale for comparing fallers and non-fallers. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2004;38:11–26. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naylor JM, Mills K, Buhagiar M. et al. Minimal important improvement thresholds for the six-minute walk test in a knee arthroplasty cohort: triangulation of anchor- and distribution-based methods. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:390. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1249-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM. et al. Knee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: evidence from the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Followup Study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. The development and validation of a functional fitness test for community residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129–161. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maly MR, Costigan PA, Olney SJ. Determinants of self-report outcome measures in people with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sutbeyaz ST, Sezer N, Koseoglu BF. et al. Influence of knee osteoarthritis on exercise capacity and quality of life in obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2071–2076. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leeuw M, Mariëlle Goossens EJB, Linton SJ. et al. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holla JFM, Van der Leeden M, Heymans MW. et al. Three trajectories of activity limitations in early symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a 5-year follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1369–1375. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odding HA, Valkenburg D, Algra FA. et al. The association of abnormalities on physical examination of the hip and knee with locomotor disability in the Rotterdam Study. Rheumatol. 1996;35:884–890. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.9.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]