The absence of genetic tools for Frankia research has been a major hindrance to the associated field of actinorhizal symbiosis and the use of the nitrogen-fixing actinobacteria. This study reports on the introduction of plasmids into Frankia spp. and their functional expression of green fluorescent protein and a cloned gene. As the first step in developing genetic tools, this technique opens up the field to a wide array of approaches in an organism with great importance to and potential in the environment.

KEYWORDS: actinorhizal symbiosis, cloning vector, gene transfer, genetics, nitrogen fixation, plant-microbe interactions

ABSTRACT

A stable and efficient plasmid transfer system was developed for nitrogen-fixing symbiotic actinobacteria of the genus Frankia, a key first step in developing a genetic system. Four derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS were successfully introduced into different Frankia strains by a filter mating with Escherichia coli strain BW29427. Initially, plasmid pHKT1 that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) was introduced into Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3 at a frequency of 4.0 × 10−3, resulting in transformants that were tetracycline resistant and exhibited GFP fluorescence. The presence of the plasmid was confirmed by molecular approaches, including visualization on agarose gel and PCR. Several other pBBR1MCS plasmids were also introduced into F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and other Frankia strains at frequencies ranging from 10−2 to 10−4, and the presence of the plasmids was confirmed by PCR. The plasmids were stably maintained for over 2 years and through passage in a plant host. As a proof of concept, a salt tolerance candidate gene from the highly salt-tolerant Frankia sp. strain CcI6 was cloned into pBBR1MCS-3. The resulting construct was introduced into the salt-sensitive F. casuarinae strain CcI3. Endpoint reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) showed that the gene was expressed in F. casuarinae strain CcI3. The expression provided an increased level of salt tolerance for the transformant. These results represent stable plasmid transfer and exogenous gene expression in Frankia spp., overcoming a major hurdle in the field. This step in the development of genetic tools in Frankia spp. will open up new avenues for research on actinorhizal symbiosis.

IMPORTANCE The absence of genetic tools for Frankia research has been a major hindrance to the associated field of actinorhizal symbiosis and the use of the nitrogen-fixing actinobacteria. This study reports on the introduction of plasmids into Frankia spp. and their functional expression of green fluorescent protein and a cloned gene. As the first step in developing genetic tools, this technique opens up the field to a wide array of approaches in an organism with great importance to and potential in the environment.

INTRODUCTION

The actinorhizal symbiosis is an endosymbiotic nitrogen-fixing association between members of Frankia, a genus of actinobacteria, and a variety of angiosperms (1, 2). These plants, termed actinorhizal plants, represent over 200 diverse species of dicotyledonous plants classified into 8 distinctive plant families. Symbiosis with Frankia spp. allows actinorhizal plants to colonize harsh environments. Actinorhizal plants have a positive impact on the environment, including restoration of disrupted environmental sites, soil stabilization, reforestation, and reclaiming of saline soils (3–5). Besides ecological and economic reasons, the capacity of an individual Frankia sp. strain to nodulate and fix nitrogen in association with plants in as many as eight different families makes this system attractive to study.

However, one of the major obstacles in the field of actinorhizal symbiosis is the lack of genetic tools for the bacterial partner Frankia sp. In fact, the genetics of Frankia is still in its infancy. The reasons for the slow development of genetic tools are complex and include the low growth rate of Frankia spp. and the difficulty of obtaining single genomic units. Because of these impediments and to provide vital information on its symbiosis, the genomes for many Frankia strains have been sequenced (6–8), and these databases have opened up the use of “omics” approaches (9).

At present, there are no known systems for stable gene transfer in Frankia spp. Analysis of the Frankia genomes revealed the presence of integrated phages (7) and integrating conjugative elements (ICE) in several Frankia strains (7, 10), but the use of these elements has not been pursued as a genetic tool. In general, genetic analysis of Frankia spp. has been restricted to gene cloning, phylogenetic analyses of selected gene sequences, and some limited studies on plasmid isolation and mutagenesis. Initially, a few studies on spontaneous mutants in Frankia spp. have been reported (11–13), and chemical (N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and ethyl methanesulfonate treatments) and physical (UV) mutagenesis approaches have also been investigated with some success but limited potential as tools (14–17).

A number of Frankia strains contain plasmids (18). Several of the Frankia plasmids have been cloned and sequenced (19–23) to determine their use as a vector. A putative ori region common to both pFQ12 and pFQ11 was identified (20, 22), while another one was predicted in pFQ31 (23). The absence of common origins for these indigenous Frankia plasmids and their size (>8.5 kb) make their development as cloning vectors difficult. None of these indigenous Frankia plasmids have been transferred to another Frankia strain. Moreover, there is an absence of efficient and stable transformation methods for Frankia spp.

There have been three published attempts at DNA transfer in Frankia cells that have resulted in low efficiency of transfer or unstable transformed cells (24–26). The effect of electroporation conditions on cell viability was determined (25). Chromosomal DNA of Frankia strain EAN1pec, a lincomycin- and kasugamycin-resistant strain, was electroporated into Frankia inefficax strain EuI1c, which is sensitive to lincomycin and kasugamycin (25). Several stable transformants that were resistant to either lincomycin or kasugamycin were identified, stably maintained, and characterized physiologically. No molecular analyses were performed to confirm the presence of the inserted genomic DNA in the transformants. In another study, electroporation of fusion marker genes into Frankia spp. resulted in transient transformants (26). The phenotype of these unstable transformants declined over several generations, indicating that the constructs were not stable.

In this study, the introduction of plasmids into Frankia spp. via conjugation is reported. Four derivatives of the cloning vector pBBR1MCS (with different antibiotic resistance) were successfully introduced in different Frankia strains. The efficiency of transformation, molecular confirmation of the transfer, and copy number of plasmids per Frankia genome were evaluated for the different combinations. The plasmid pHTK1 (27), a derivative of the pBBR1 plasmid, which expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP), was used initially in our study. The stable transfer of pHTK1 into different Frankia strains was demonstrated, and it was confirmed by molecular evidence and by observed GFP expression inside Frankia strains. As a proof of concept, the pBBR1MCS-3 vector was used for cloning of salt tolerance candidate genes which were introduced into Frankia strains, subsequently providing elevated salt tolerance.

RESULTS

Efficient mating and transfer of pHTK1 into Frankia cells.

A reproducible and efficient method of Frankia transformation was developed based on mating on a solid-surface medium using Escherichia coli as the donor. To counterselect against the donor, E. coli strain BW29427, a diaminopimelic acid auxotroph (DAP−), was used in this study. This strain will not grow on defined medium, like MOPS-phosphate-nitrogen (MPN) medium, unless supplemented with diaminopimelic acid. Plasmid pHKT1 was initially used in these transformation experiments. Since this plasmid was introduced into the Gram-positive actinobacteria Rhodococcus spp. (28) and another high-G+C-content bacterium, Burkholderia cepacia (27), we reasoned that it could potentially work in the high-G+C-content Frankia actinobacteria.

To test this idea, Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3, whose plant host range is restricted to Casuarinaceae, was chosen because it has a sequenced genome (6) and is the subject of many studies in the discipline. After mating F. casuarinae strain CcI3 with E. coli BW29427(pHKT1), the mixture was plated on MPN medium, as described in Materials and Methods, and incubated at 30°C. After 3 to 4 weeks, isolated small colonies that showed an appearance characteristic of a Frankia colony appeared on the selective medium (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The colonies were incubated for another 2 weeks prior to harvesting (Fig. S1). Single colonies with a minimum 3-mm diameter were harvested and transferred to liquid culture containing tetracycline. The transformants were stable and have been maintained in culture for over 3 years in some cases. The frequency of transformation for F. casuarinae strain CcI3 with the vector pHKT1 was 4.0 × 10−3 (Table 1), which is much greater than the frequency of spontaneous tetracycline resistance (1.0 × 10−7). The controls showed appropriate expected results. Matings lacking a recipient did not grow on MPN medium with kanamycin with or without DAP, while matings lacking a donor generated colonies at a frequency similar to the spontaneous mutation frequency (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of plasmid transformation and spontaneous mutation rates for antibiotic resistances for different Frankia strainsa

| Strain (clade) | Transformation frequency (no. of transformants/total CFU) |

Spontaneous frequency (no. of mutants/total CFU) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHKT1 with 20 μg/ml Tc | pBBR1MCS with 25 μg/ml Chlo | pBBR1MCS-3 with 20 μg/ml Tc | 20 μg/ml Tc | 25 μg/ml Chlo | |

| F. casuarinae CcI3 (Ic) | 4.0 × 10−3 | 1.4 × 10−4 | 4.3 × 10−3 | 1.0 × 10−7 | 5.8 × 10−7 |

| Frankia sp. strain Thr (Ic) | ND | ND | 3.0 × 10−4 | 8.0 × 10−6 | 5.6 × 10−6 |

| Frankia sp. strain EUN1f (III) | ND | 3.2 × 10−3 | 1.7 × 10−2 | 7.6 × 10−6 | 1.0 × 10−6 |

| F. inefficax EuI1c (IV) | 1.0 × 10−4 | ND | 8.4 × 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−6 | ND |

Tc, tetracycline; Chlo, chloramphenicol; ND, not determined.

Confirmation of the presence of the plasmid in Frankia cells.

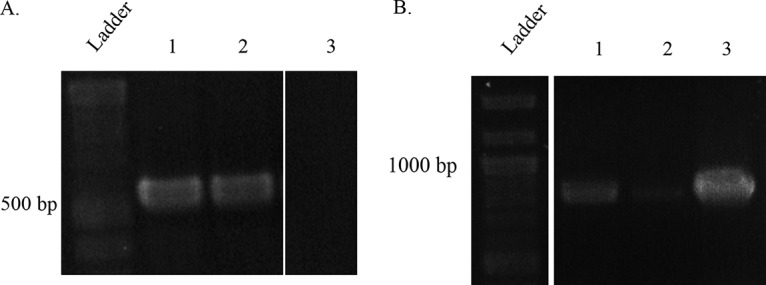

All of the transformants were confirmed by several molecular approaches. First, the plasmids were extracted from F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants and linearized by enzymatic digestion with NsiI. A single band was observed only for the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants (lanes 2 and 5) and E. coli DH5α(pHKT1) (lane 4) (Fig. 1A). Those bands migrated to the same position in the gel, indicating that they were the same size. The band was absent for the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 (lane 1), and two bands were observed for the undigested plasmid extracted from F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) corresponding to the different plasmid conformations visible on gel electrophoresis (lane 3). Second, a portion of the tetracycline resistance gene found on the plasmid was amplified from DNA extracted from transformants grown in liquid culture (Fig. 1B). Amplicons were detected for F. casuarinae strain CcI3 transformed with pHKT1 plasmid (lane 1), while the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 did not generate an amplicon (lane 5).

FIG 1.

Molecular confirmation of the plasmid transfer in different Frankia strains. (A) Gel electrophoresis of the extracted plasmid pHKT1. The plasmid was extracted as described in Materials and Methods and run on an agarose gel. Lane 1 represents the negative-control F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain. Lanes 2, 3, and 5 represent F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants. Lanes 2 and 5 show the linearized plasmid pHKT1 after treatment with the restriction enzyme NsiI, while lane 3 shows the uncut plasmid pHKT1. Lane 4 shows the linearized plasmid pHKT1 from E. coli DH5α(pHKT1). The pHKT1 plasmid is 6,897 bp in size. (B) Presence of tetracycline amplicon an agarose gel. The tetracycline PCR fragment amplified from total DNA, as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant; lane 2, F. casuarina strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant; lane 3, F. inefficax strain EuI1c(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant; lane 4, E. coli DH5α(pBBR1MCS-3) (positive control); lane 5, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (negative control); lane 6, F. inefficax EuI1c wild-type strain (negative control). The expected size of the tetracycline fragment was 488 bp. A 2-log DNA ladder (New England BioLabs, MA) was used as a molecular marker (lane L).

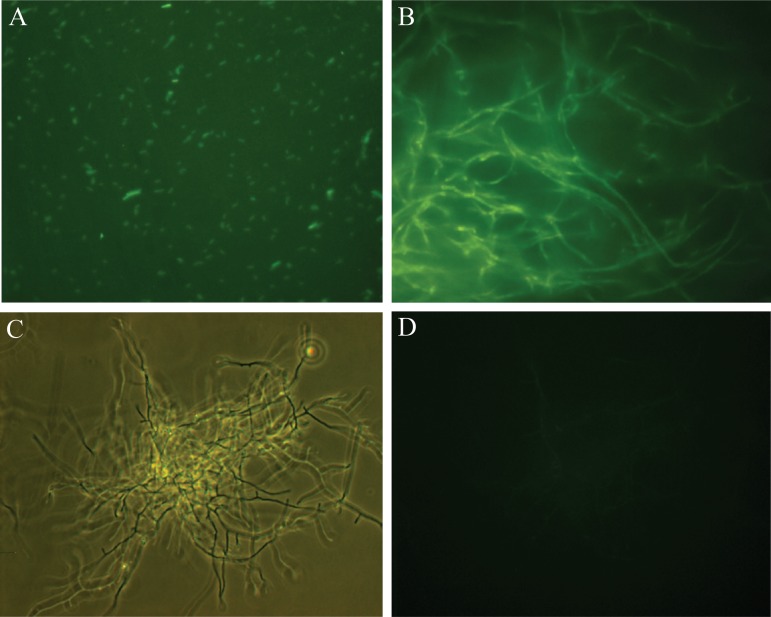

Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants were also observed under fluorescence microscopy. The results are presented in Fig. 2. Green fluorescence was observed for the E. coli DH5α(pHKT1) (Fig. 2A) and for a 7-day-old F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant (Fig. 2B). The wild-type strain F. casuarinae strain CcI3 did not fluoresce (Fig. 2C and D). All of the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants maintaining the plasmid pHKT1 fluoresced under these conditions. The fluorescence was observed in the hyphae of the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants. These results indicate that exogenous gene expression can occur in Frankia strains.

FIG 2.

Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3 transformed with pHKT1 fluoresces. Cultures were observed by fluorescence microscopy at ×400 magnification. (A) GFP-labeled E. coli DH5α(pHKT1) after overnight culture in liquid LB medium. (B) GFP-labeled F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant after 7 days of growth on MPN liquid medium. (C and D) Control F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain after 7 days of growth in MPN medium but under phase-contrast microscopy (C) and fluorescence microscopy (D). Panels A and B also show fluorescence microscopy.

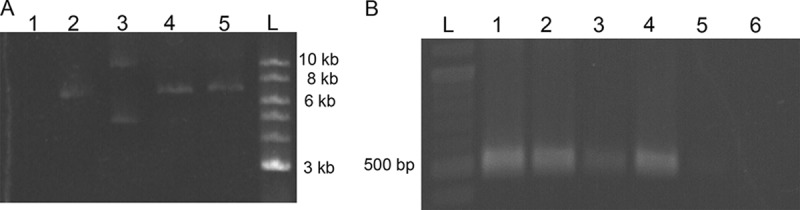

Confirmation of the stability of the transformant in planta.

The F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant was inoculated into the host plant Casuarina glauca in order to observe the stability of the transformant in planta. The resulting nodules were collected 2 months after inoculation and surface sterilized. The nodules were fragmented and plated on growth medium. After a 2-month incubation, single colonies were harvested and subcultured into liquid growth medium. The cultures were incubated for 2.5 months, and genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from liquid culture. A PCR approach was used to identify these isolates as Frankia strains maintaining the pHKT1 plasmid (Fig. 3). The chromosomal gene Francci3_3203 (UTRase gene) was used to identify F. casuarinae strain CcI3 (Fig. 3A). As expected, amplicons were detected for both the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant isolated from C. glauca nodules and the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3. No amplicon was observed for the negative control corresponding to the plasmid extracted from E. coli DH5α(pHKT1). The same samples were used to detect the presence of the plasmid pHKT1 by PCR amplification of the tetracycline resistance gene (Fig. 3B). Amplicons were detected for the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant isolated from C. glauca nodules and the plasmid extracted from E. coli DH5α(pHKT1). The wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 did not generate an amplicon. The amplicons obtained in Fig. 3A were sequenced (Fig. S2). The sequences for amplicons of the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant (nodule isolate) and E. coli strain DH5α(pHKT1) are identical. These results confirmed the presence and the stability of the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant within C. glauca nodules and after reisolation. Under these conditions, the plasmid was maintained for over 6 months.

FIG 3.

Molecular confirmation of the stability of the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) in planta. The F. casuarinae strain CcI3 UTRase gene (Francci3_3203) was amplified as described in Materials and Methods, and the amplicons were visualized an agarose gel. (A) Gel electrophoresis of the UTRase gene amplicons. Lane 1 shows F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) isolated from C. glauca nodules; lane 2, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (positive control); lane 3, E. coli DH5α(pBBR1MCS-3) (negative control). The expected size of the amplicon was 539 bp. (B) Gel electrophoresis profile of plasmid-specific amplicon (the tetracycline resistance gene). Lane 1 shows F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) isolated from C. glauca nodules; lane 2, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (negative control); lane 3, has E. coli DH5α(pBBR1MCS-3) (positive control). The expected size of the tetracycline fragment was 854 bp. Gels were spliced to remove duplicate lanes.

Use of the pBBR1MCS plasmid in the transformation of Frankia spp.

The plasmid pHKT1 is mobilized via the RP4/RK2 mating system and possesses an origin of replication (OriV) and the replication gene (rep) from plasmid pBBR1 (27). Thus, pHKT1 is a derivative plasmid of the pBBR1MCS plasmid family (27) that expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP). We reasoned that other pBBR1MCS plasmids should be compatible with Frankia strains, and three derivative plasmids of the broad-host-range cloning plasmid pBBR1MCS (pBBR1MCS, pBBR1MCS-3, and pBBR1MCS-5) were used to transform different Frankia strains. Four Frankia strains (CcI3, Thr, EuI1c, and EUN1f) belonging to three different clades were transformed. The frequencies of transformation are presented in Table 1. Transformants with pBBR1MCS-5, carrying a gentamicin resistance gene, were unable to be transferred into liquid culture with gentamicin (data not shown). The transformation frequencies obtained for pHKT1, pBBR1MCS, and pBBR1MCS-3 were between 3.2 × 10−2 and 8.4 × 10−4. These frequencies are higher than the frequencies of spontaneous mutations (5.6 × 10−6 to 5.8 × 10−7) to tetracycline or chloramphenicol (Table 1). The transformants were transferred into liquid medium with the appropriate antibiotic and exhibited the same rate growth as the wild-type strain.

Similar to studies on F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants, the presence of pBBR1MCS in Frankia spp. was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1B). Figure 1B presents the molecular confirmation of F. casuarinae strain CcI3(PBBR1MCS-3) and Frankia inefficax EuI1c(pBBR1MCS-3) transformants. The tetracycline resistance gene amplicons were detected for the two transformants and the control E. coli strain. The two Frankia wild-type strains, F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and F. inefficax EuI1c, did not produce a band. These data confirm the presence of the plasmid in the transformants.

Determination of the plasmid copy number per Frankia genome.

A quantitative PCR (qPCR) approach was used to determine the average plasmid copy number per Frankia genome. Specific primer sets targeted to the tetracycline gene for pBBR1MCS-3 and pHKT1 plasmids or the lacZ gene for the pBBR1MCS plasmid were used to quantify the amount of plasmid in a sample. A specific primer set targeted to a single-copy gene within the Frankia genome was used to determine the number of genomes present in a sample. Dividing these two values determines the plasmid copy number. The data presented in Table 2 represent the average of 4 to 5 measurements for a minimum of 2 independent transformants. Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3 transformants contained 12 to 15 copies of pBBR1MCS-3 and 9 to 10 copies of pBBR1MCS per F. casuarinae genome. The copy number for pHKT1 found in F. casuarinae strain CcI3 was lower by 3 to 4 copies per genome and may be explained by the larger size of the plasmid. Plasmid size is negatively correlated with the plasmid copy number per cell (29). Frankia inefficax strain EulIc maintained a low copy number (about 1) for pBBR1MCS-3 and pHKT1. These F. inefficax strain EulIc transformants grew with appropriate antibiotics, and the presence of the plasmid was detected by PCR. These results were repeated with four independent transformants using different primers sets (Table 2). Frankia sp. strain EUN1f (clade III) had 18 copies of pBBR1MCS-3 per genome. Frankia sp. strain Thr (clade Ic) had an average of 9 to 11 copies for pBBR1MCS-3, similar to the value obtained with F. casuarinae strain CcI3 (clade Ic).

TABLE 2.

Plasmid copy number per Frankia genome

| Strain (clade) | Copy no.a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pHKT1 with 20 μg/ml Tc | pBBR1MCS with 25 μg/ml Chlo | pBBR1MCS-3 with 20 μg/ml Tc | |

| F. casuarinae CcI3 (Ic) | 3–4 | 9–10 | 12–15 |

| F. inefficax EuI1c (IV) | 1 | ND | 1 |

| Frankia sp. EUN1f (III) | ND | ND | 19 |

Tc, tetracycline; Chlo, chloramphenicol; ND, not determined.

To test the stability of these plasmids, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBB1MCS-3) and F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformants were subcultured every 2 to 3 weeks for 9 months and divided into MPN liquid medium with or without the selective antibiotic for 2 weeks. The copy numbers for pBBR1MCS-3 or pHKT1 were similar under both conditions. For pBBR1MCS-3, the average copy number was 9 with or without tetracycline, while pHKT1 had an average copy number of 3 to 4.

Many of these transformants have been maintained in the lab for over 3 years. After 9 months of subculture, transformant F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBB1MCS-3), which had an initial copy number of 12, maintained a similar copy number of 10. A plasmid copy number of 10 was maintained for transformants cultured for 22 months. The F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant also maintained a similar value for the average copy number, as follows: 3 to 4 copies initially, remained unchanged 9 months later, and 6 to 7 copies after 22 months of incubation. These data confirm the stability of these plasmids in different Frankia strains over a 22-month period.

Proof of concept of this mating transformation method based on salt tolerance of Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3.

Genetic, transcriptomic, and proteomics approaches identified seven candidate genes that are responsive to salt stress (30). These candidates are present in the salt-tolerant Frankia sp. strain CcI6 and absent in the salt-sensitive F. casuarinae strain CcI3. They are upregulated under stress conditions in Frankia sp. strain CcI6. Gene CcI6_RS22605 from Frankia sp. strain CcI6 was selected for the study and is predicted to code for a zinc peptidase. The predicted coding region and 350 bp upstream of the predicted start codon were cloned into pBBR1MCS-3 plasmid (pBBR1MCS-3-22605). F. casuarinae strain CcI3, a salt-sensitive strain, was transformed with this construct. The efficiency of transformation was 1.25 × 10−4.

To confirm the presence of the construct in F. casuarinae strain CcI3 cells, a PCR approach was used on two distinct transformants. Figure 4A shows amplification of a fragment of tetracycline gene and part of a mobility region for the plasmid for the two different transformants and the positive control (purified pBBR1MCS-3-22605 plasmid). As expected, no amplification was obtained for the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3. The presence of the gene CcI6_RS22605 in these F. casuarinae strain CcI3 transformants was also confirmed by PCR (Fig. 4B). The amplicon of the CcI6_RS22605 gene was generated with the two F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformants and the positive control, the wild-type strain F. casuarinae CcI6 DNA. The amplicon was absent in both in the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and the vector control, the F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant containing the empty vector. Colony PCR was also performed to confirm the presence of the plasmid in F. casuarinae strain CcI3 cells (Fig. S3). With this technique, Frankia colonies could be screened after 5 to 6 weeks of growth instead of waiting 5 extra weeks of growth in liquid culture for DNA extraction (30). These data confirmed the presence of the constructs in the two F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformants tested.

FIG 4.

Molecular confirmation of the transformation of F. casuarinae strain CcI3 with pBBR1MCS-3-22605. (A and B) Gel electrophoresis profiles of amplicons of the tetracycline resistance and mobility genes on the vector and CcI6_RS22605 genes for the insert, respectively. (A) Results of amplification of tetracycline resistance and mobility gene fragments with an expected size of 1,269 bp. Lane 1, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 1; lane 2, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 2; lane 3, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant; lane 4, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (negative control). (B) Results of amplification of the CcI6_RS22605 gene fragments with an expected size of 451 bp. Lane 1, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 1; lane 2, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 2; lane 3, F. casuarinae CcI6 wild-type strain (positive control); lane 4, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (negative control); lane 5, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant with the empty vector (negative control). (C) Gel electrophoresis profile of endpoint RT-PCR for CcI6_RS22605 gene. Lane 1, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 1; lane 2, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant 2; lane 3, F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant with the empty vector (negative control); lane 4, F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (negative control); lane 5, Frankia sp. CcI6 wild-type strain (positive control). The size expected for the cDNA amplification was 450 bp. Gels were spliced to remove duplicate lanes.

The expression of the CcI6_RS22605 gene in these Frankia transformants was determined by endpoint reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (Fig. 4C). The CcI6_RS22605 gene was only expressed in the two F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformants and the positive-control Frankia sp. strain CcI6 wild type. Both the F. casuarinae strain CcI3 containing the empty vector pBBR1MCS-3 and F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain did not express the gene. These results show that the cloned gene was expressed in the transformants.

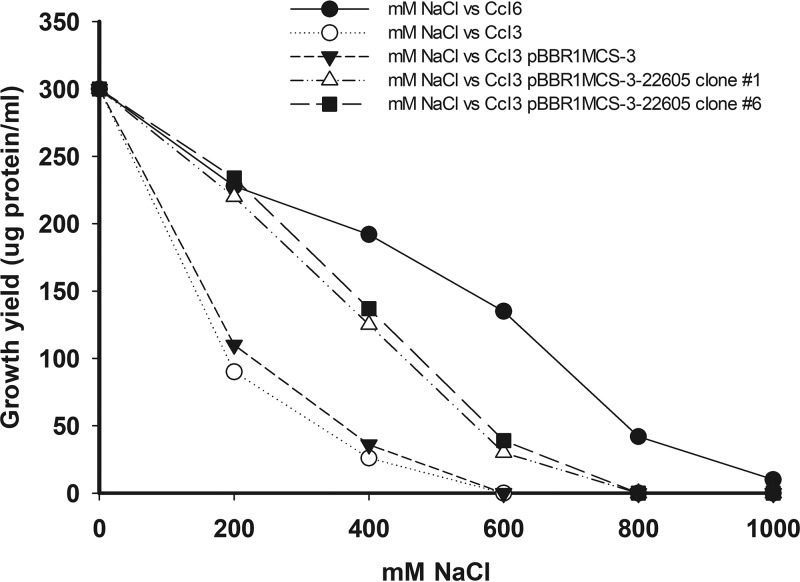

The effect of the cloned gene on the salt tolerance by F. casuarinae strain CcI3 was tested by a growth assay (Fig. 5). Wild-type Frankia sp. strain CcI6 was the most resistant to salt stress and had an MIC value of 1,000 mM NaCl, while wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 was more sensitive to salt concentrations, having an MIC value of 475 mM NaCl, similar to previous results (30). The two F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformants, clones 1 and 6, showed an increase in the level of salt tolerance (MIC value, 650 mM NaCl) compared to wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3 but less than that of Frankia sp. strain CcI6. Frankia casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) containing the empty vector exhibited a salt tolerance pattern (MIC value, 475 mM NaCl) similar to that of the wild-type F. casuarinae strain CcI3. These results demonstrate that the cloned CcI6_RS22605 gene, encoding a zinc peptidase, was expressed and provided an increase in salt-tolerant F. casuarinae strain CcI3.

FIG 5.

The expression of the CcI6_RS22605 gene, a salt tolerance gene, in F. casuarinae strain CcI3 transformants increases its salt tolerance level. Frankia cultures were grown for 14 days in growth medium containing different NaCl concentrations, as described in Materials and Methods. The growth yield was determined by measuring the total protein content and corrected for the inoculum content. Growth curves were standardized to 300 μg/ml for the control conditions (0 mM NaCl). Symbols represent F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant clone 1 (open triangles), F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformant clone 6 (closed squares), F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) transformant containing the empty vector (closed triangles), F. casuarinae CcI3 wild-type strain (open circles), and Frankia sp. CcI6 wild-type strain (closed circles).

DISCUSSION

For many years, one of the major obstacles hindering the study of Frankia actinobacteria was the lack of genetic tools, including a stable transformation method. In this study, a mating transformation protocol was designed using filter mating methods. This is a successful method developed for stable plasmid transfer in Frankia spp. that allows the expression of cloned genes. Several lines of evidence have been presented to demonstrate that the approach is successful. First, antibiotic resistance transformants were generated at a higher frequency (at least 2 log) than the spontaneous mutation rate. Second, the presence of the plasmid was detected by molecular approaches, including detection in an agarose gel and PCR amplification of plasmid genes. Third, transformants expressed the genes encoded on the plasmid, including GFP and antibiotic resistance or genes cloned into the vector. These plasmids were stably maintained in the transformants over 3 years. PCR approaches confirmed the presence of the plasmid in 22-month-old transformants, and the copy number of these plasmids did not change after 22 months of culturing. The plasmid was also maintained after passage through a host plant and sequential recovery of the strain from the host plant, providing further evidence of the plasmid stability. Thus, the plasmid was stably maintained by Frankia spp. and was not either degraded or expulsed.

The four Frankia strains used in this study represent three of the four Frankia clades, which are based on molecular phylogenetic analysis and host plant range (1). Clade I consists of Frankia strains that associate with host plants in the Casuarinaceae, Betulaceae, and Myricaceae families, while members of clade II are infective on Rosaceae, Coriariaceae, Datiscaceae, and the genus Ceanothus (Rhamnaceae). Members of clade III are the most promiscuous and are infective on Elaeagnaceae, Rhamnaceae, Myricaceae, Gymnostoma, and occasionally the genus Alnus. Clade IV consists of “atypical” Frankia strains that are unable to reinfect actinorhizal host plants or form ineffective root nodule structures that are unable to fix nitrogen. Clade I contains subclades, and subclade Ic contains strains limited to Casuarina and Allocasuarina host plants.

The mating method of plasmid transfer in Frankia spp. also had a higher efficiency (10−2 to 10−4, Table 1) than in our previous study using electroporation (10−5) (25). Other studies using electroporation generated unstable transformants (24, 26). Mating transformation produced a larger amount of viable Frankia cells than under electroporation conditions. Thus, the mating method allows screening a larger population of cells (106 to 107 CFU) than electroporation (104 to 105 CFU) (25). It seems that the viability of Frankia cells decreases as the capacitance of the electrical pulse increased (15). The filter mating method with the use of a vacuum increased the physical contact between the donor and recipient cells, which elevated the transfer efficiency. For Frankia spp., transformation protocols using mating methods appear to allow for a more successful outcome than does electroporation.

The mating method used in this study generates a single CFU on agar, which should produce a homogenous population of transformants. Liquid transformation methods can result in a mixture of cells that does not homogenously contain plasmids. The major drawback for the mating method is that it requires a minimum 13 to 14 weeks from the plating to the molecular confirmations of the transformants (Fig. S1). This long chronology is mainly due to the low growth rate of Frankia cells. Frankia cells will grow faster in liquid culture, but plating is the only method to select and isolate transformants for further study. However, time could be saved at the molecular confirmation step (Fig. S1) by using an efficient colony PCR method that will cut out the 8- to 9-week time span to confirm the presence of the plasmid in bacterial colony (31).

The plasmids used in this study are derivative plasmids from the broad-host-range cloning plasmid pBBR1 isolated from Gram-negative Bordetella bronchiseptica (28). These derivative plasmids of pBBR1 have been successfully transferred into the Gram-positive actinobacteria of Rhodococcus (32) and in numerous Gram-negative bacteria (33). Moreover, the high stability of these plasmids has been demonstrated in Brucella spp. pBBR1MCS was still detected in different Brucella strains after over 50 days in the absence of antibiotic selection (34). These plasmids are mobilized via the RP4/RK2 mating system and possess an OriV, origin of replication, and replication gene (rep) (33). They combine a Gram-positive mobilization mechanism with a Gram-negative replication mechanism. This replication mechanism does not use the rolling-circle mechanism that is commonly found in Gram-positive plasmids. pBBR1 uses the theta mechanism, which consists of the melting of parental strands, synthesis of primer RNA, and initiation of DNA synthesis by extension of the RNA primer (35). Thus, the key for successful plasmid transfer and stability in Frankia spp. appears to be the use of a plasmid containing a Gram-positive mobilization mechanism and an uncommon Gram-negative replication, the theta mechanism. This conclusion is supported by previous attempts at introducing other plasmids that have different origins without success (our unpublished data). We propose that other plasmids containing similar characteristics could be introduced into Frankia spp. by this transformation method to test this hypothesis.

Introduction of pHKT1 in F. casuarinae strain CcI3 provided evidence of exogenous gene expression within Frankia cells. These transformed cells fluoresced due to the presence of the gfp gene on the plasmid (Fig. 2). Older cultures (1 month old or older) lost fluorescence, suggesting that other factors might be involved, including bacterial growth state. Subculturing these transformants into fresh growth medium caused the recovery of fluorescence. Bacterial gene expression is regulated by growth rate and state (36). Different growth states cause a change in the abundance of repressor or activator proteins involved in gene expression regulation. A proof-of-concept experiment was developed to test if a cloned gene could be expressed in Frankia spp. Our results demonstrate that the CcI6_RS22605 gene from Frankia sp. strain CcI6 was successfully introduced into F. casuarinae strain CcI3. Several lines of evidence show that the gene was present and expressed in its Frankia host (Fig. 4 and 5). The expression of that gene resulted in an elevated level of salt tolerance (Fig. 5) but not to the level of Frankia sp. strain CcI6. This gene is upregulated under salt stress conditions for salt-tolerant Frankia sp. strain CcI6 and absent in the salt-sensitive F. casuarinae strain CcI3 (30).

The results of this study provide an important genetic tool for this Gram-positive bacterium. The availability of many sequenced Frankia genomes and other “omics” databases provides vital information on potential genes of interest involved in the actinorhizal symbiosis. The development of the cloning vector and subsequent exogenous gene expression in Frankia spp. provide a useful tool that will allow the potential of a unique and environmentally important organism to be more fully realized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth and maintenance of bacterial strains.

Table 3 lists all of the plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study. Frankia stock cultures were grown and maintained in basal MP growth medium (37, 38) supplemented with 5.0 mM NH4Cl and the appropriate carbon source. Basal MP growth medium consisted of morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-phosphate buffer (50 mM MOPS, 10 mM K2HPO4 [pH 6.8]) supplemented with 1 mM Na2MoO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 20 μM FeCI3 with 100 μM nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA), and modified trace salts solution (37). For F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and Frankia sp. strains CcI6 and Thr, 5 mM sodium propionate was used as a carbon and energy source, while 20 mM glucose or fructose was used with F. inefficax strain EuI1c and Frankia sp. strain EUN1f, respectively. Standing cultures were incubated at 30°C. Liquid cultures of Frankia strains or transformants were subcultured every 2 to 3 weeks. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) with appropriate antibiotics when required.

TABLE 3.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F– Φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK– mK+) phoA supE44 λ– thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | 43 |

| BW29427 | hsdSlacZΔM15 RP4-1360 Δ(araBAD)567 ΔdapA1341::(erm pir)tra | Datsenko and Wanner, unpublished data |

| DH5α(pHKT1) | E. coli DH5α containing pHKT1 | This study |

| DH5α(pBBR1MCS) | E. coli DH5α containing pBBR1MCS | 33 |

| DH5α(pBBR1MCS-3) | E. coli DH5α containing pBBR1MCS-3 | 33 |

| DH5α(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) | E. coli DH5α containing pBBR1MCS-3-22605 | This study |

| BW29427(pHKT1) | E. coli BW29427 containing pHKT1 | This study |

| BW29427(pBBR1MCS) | E. coli BW29427 containing pBBR1MCS | This study |

| BW29427(pBBR1MCS-3) | E. coli BW29427 containing pBBR1MCS-3 | This study |

| BW29427(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) | E. coli BW29427 containing pBBR1MCS-3-22605 | This study |

| Frankia spp. | ||

| F. casuarinae strain CcI3 | Wild type, Gmr Kanr Kasr | 38, 44 |

| Frankia sp. strain CcI6 | Wild type | 45 |

| F. inefficax strain EuI1c | Wild type, Novr | 38, 46 |

| Frankia sp. strain EUN1f | Wild type, Strr Novr | 38, 47 |

| Frankia sp. strain Thr | Wild type | 48 |

| CcI3(pHKT1) | F. casuarinae strain CcI3 containing pHKT1 | This study |

| CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3) | F. casuarinae strain CcI3 containing pBBR1MCS-3 | This study |

| CcI3(BBR1MCS) | F. casuarinae strain CcI3 containing pBBR1MCS | This study |

| EuI1c(pHTK1) | F. inefficax strain EuI1c containing pHTK1 | This study |

| EuI1c(pBBR1MCS) | F. inefficax strain EuI1c containing pBBR1MCS | This study |

| EUN1f(pBBR1MCS-3) | Frankia strain EUN1f containing pBBR1MCS-3 | This study |

| EUN1f(pBBR1MCS) | Frankia strain EUN1f containing pBBR1MCS | This study |

| CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) | F. casuarinae strain CcI3 containing pBBR1MCS-3-22605 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHKT1 | gfp fragment, Tcr | 27 |

| pBBR1MCS-3 | Broad-host-range vector, Tcr | 33 |

| pBBR1MCS | Broad-host-range vector, Chlor | 33 |

| pBBR1MCS-3-22605 | pBBR1MCS-3 containing gene 22605 from strain CcI6 | This study |

Gmr, gentamicin resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Kasr, kasugamycin resistant; Novr, novobiocin resistant; Strr, streptomycin resistant; gfp, green fluorescent protein; Tcr, tetracycline resistant; Chlor, chloramphenicol resistant.

Transformation of Frankia spp. by mating.

Prior to conjugation with Frankia strains, the plasmids used in this study were introduced into the donor E. coli BW29427, a diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph, by electrotransformation. Plasmids were introduced into recipient Frankia strains through filter mating with the donor E. coli BW29427. Briefly, a Frankia culture (100 ml) was grown to logarithmic phase (7 days old) and harvested by centrifugation (20 min at 4,300 × g). The cells were resuspended in 1 ml of MP medium. The Frankia cells were mixed with 500 μl culture of E. coli BW29427 grown to an optical density of 0.6. The Frankia-E. coli mixture was collected by filtration on a sterile 0.22-μm polycarbonate filter under vacuum pressure. The polycarbonate filter was aseptically transferred onto the surface of an LB agar plate supplemented with 300 μM DAP and incubated at 28°C for 24 h. After incubation, the filter was removed and suspended in 3 ml MPN medium. The suspension was vortexed to separate the cell pellet from the filter. The Frankia-E. coli cell pellet was fragmented by gently grinding in a sterile glass tissue homogenizer. This step was necessary to fragment the Frankia mycelia. The homogenized mixture was used directly or was diluted 10−1- to 10−6-fold in MP medium. Five hundred microliters of the 100, 10−1, or 10−2 dilution was mixed with 3 ml of 0.8% agar MP and the appropriate antibiotics. For example, for the transformation of F. casuarinae strain CcI3 with pHTK1, 20 μg/ml tetracycline and 25 μg/ml kanamycin were used. Tetracycline was used to stress the plasmid and kanamycin to select for Frankia spp. and counterselect against the donor. The antibiotic concentrations used were 20 μg/ml tetracycline, 25 μg/ml kanamycin, and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The 0.8% agar mixture, containing the appropriate antibiotics, was poured onto the surface of MPN growth medium with 2% agar. Mixing was done by tipping the plates from side to side before the agar hardened. The plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at 30°C. To determine the total number of Frankia CFU, 500 μl of the 10−2 to 10−6 dilutions was mixed with 3 ml of 0.8% agar MP without antibiotics. The diluted 0.8% agar mixtures were poured onto MPN growth medium without antibiotics, mixed, and sealed as described above. After 5 to 6 weeks of incubation, single 3-mm-diameter Frankia colonies were picked and grown in liquid culture (Fig. S1).

To determine the frequency of transformation, the number of CFU with antibiotic resistance was divided by the total number of Frankia CFU. The frequency of a spontaneous mutation giving an antibiotic resistance was determined as described previously (15). Briefly, homogenized Frankia hyphae were diluted and plated as described above with lower dilutions under antibiotic stress and higher dilutions without antibiotics. The frequency of spontaneous mutation was determined by the number of antibiotic-resistant CFU divided by the total Frankia CFU.

Molecular detection of the plasmid.

(i) Total DNA extraction from Frankia spp. Total DNA extraction from Frankia strains or transformants were performed by a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) DNA extraction protocol (39). Six milliliters of Frankia liquid culture was used to start the extraction.

(ii) PCR. Primers used to confirm the presence of pBBR1MCS-3, pHKT1, and pBBR1MCS-3-22605 plasmids were targeted the tetracycline gene (Tcr PCR, pHKT1 PCR, or Tcr-1,269-bp PCR) (Table 4). PCR molecular confirmation of the presence of pBBR1MCS plasmid was targeted to the replication gene (rep PCR Fw and Rev) (Table 4). PCRs were carried out using 50 to 100 ng of DNA, 10 μM the forward and reverse primers (Table 4), and 25 μl OneTaq Hot Start 2× mastermix (New England BioLabs, MA) in a final volume of 50 μl. The thermocycling parameters were as follows: (i) an initial denaturation of 94°C for 5 min; (ii) 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing for 30 s at 66°C, 64°C, 60°C, 55°C, or 54°C, depending of the primer sets (Table 4), and (iii) extension 72°C for 1 min to 1.5 min, with a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. PCR amplicons were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

TABLE 4.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Target | Direction | Sequencea | Tm (°C)b | Purpose | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tcr gene PCR | Fw | TAGGAAGCAGCCCAGTAGTA | 55 | Confirmation of conjugants by PCR on tetracycline gene | This study |

| Rev | CTGTAGGCATAGGCTTGGTTAT | ||||

| pHKT1 PCR | Fw | TAGGAAGCAGCCCAGTAGTA | 55 | Confirmation of conjugants by PCR on tetracycline gene (used on colonies isolated from nodules) | This study |

| Rev | CGTTGAATCGGGATATGC | ||||

| Tcr gene-1,269bp PCR | Fw | TAGGAAGCAGCCCAGTAGTA | 64 | Confirmation of conjugant by PCR on the tetracycline gene + mob gene | This study |

| Rev | CATCCACCGTGACGAAACC | ||||

| UTRase gene PCR | Fw | CGCATCGCGCCGTCCCGGCA | 66 | Amplification on coding region of Francci_3203 gene | This study |

| Rev | GGATCAGCACGCCGTCGGCG | ||||

| rep PCR | Fw | GGTCAGCCAGAAGACACTTT | 54 | Confirmation of conjugants by PCR of pBBR1MCS | This study |

| Rev | ATTCCTCCGTTTCGGTCAAG | ||||

| Tcr qPCR | Fw | CATTAGGAAGCAGCCCAGTAG | 60 | Copy no. per cell quantification for PTHK1 and pBBR1MCS-3 | This study |

| Rev | TGTTTCGGCGTGGGTATG | ||||

| lacZ qPCR | Fw | CAATTCGCCCTATAGTGAGTCG | 60 | Copy no. per cell quantification for pBBR1MCS vector family | This study |

| Rev | CTGGCGTAATAGCGAAGAGG | ||||

| CcI3 UTRase gene qPCR | Fw | GTCCGCAGACGACATCAC | 60 | Copy no. of genome of CcI3 | This study |

| Rev | GTACTCCGAGCAGGACGA | ||||

| EuI1c copC-1 qPCR | Fw | TCTACCGCCTGTCCTACCGGAT | 60 | Copy no. of genome of EuI1c | 42 |

| Rev | ACGAACCGGACCCTACGTCA | ||||

| EUN1f ropB qPCR | Fw | CTGGAGAACCTCTTCTTCAACC | 60 | Copy no. of genome of EUN1f | This study |

| Rev | CTCCAGCTTCTTGTTGACCTT | ||||

| CcI6-22605 | Fw | ATATGGGCCCCAGACGAGTCGGCGGCGACCA | 60 | Cloning of CCI6_22605 gene into pBBR1MCS-3 | This study |

| Rev | TCATACTAGTAAGGCCTCGGCCCTCGCGAGA | ||||

| CcI6-22605 RT-PCR | Fw | GGCTCTGTTCGATCGCACCA | 55 | RT-PCR on 22605 gene | This study |

| Rev | GCCACGTGCGACGCCCCAGT |

Underlining indicates restriction sites used for cloning.

Tm, melting temperature.

(iii) Plasmid extraction from Frankia culture. A 7-day-old Frankia culture (150 ml) was harvested and washed twice in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). The pellet was resuspended in the same TE buffer and incubated at 80°C for 30 min. The cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 2% lysozyme following with and incubation at 65°C for 15 min with 2% SDS. NaOH at 0.1 N was added, and the contents were mixed and allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature. For neutralization, 1 M potassium acetate (pH 5.2) was added and mixed by inversion. The solution was centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature. The clear supernatant was transferred to a new tube and precipitated by adding 2 volumes of 100% ethanol and centrifuging at maximum speed for 15 min. The DNA was finally resuspended in 40 μl of distilled water.

To remove linear chromosomal DNA, 1× NEB buffer 4 (New England BioLabs, MA) was supplemented with 1 mM ATP and 2 μl of exonuclease V (RecBCD) (New England BioLabs). Incubation at 37°C for 1 h was done. The exonuclease was heat inactivated by incubating at 70°C for 30 min.

(iv) Colony PCR of Frankia spp. Colony PCR was performed as previously described (31). Primers used to confirm the presence of the pBBR1MCS-3 and pHKT1 plasmids were targeted the tetracycline gene Tcr (Tcr PCR colony FW and Rev) (Table 4).

(v) PCR fragment Sanger sequencing. PCR fragments were sequenced after purification of the PCR mixture by using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, CA). Samples were sent to GeneWiz for DNA Sanger sequencing. The samples were prepared according to the guidelines of the GeneWiz company.

Plasmid copy number determination.

The plasmid copy number was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (40). A specific primer set targeted to a single-copy gene in the Frankia genome was used to quantify the Frankia chromosome, as follows: uracil phosphoribosyltransferases (UTRase gene) for F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and Frankia sp. strain Thr, copC-1 for F. inefficax strain EuI1c, and rpoB for Frankia sp. strain EUN1f. To determine the amount of plasmid, specific primer sets were targeted to the following genes on the plasmids: tetracycline gene for pBBR1MCS-3 and pHKT1 and the lacZ gene for pBBR1MCS (Table 4). Standard curves were made with various concentrations of gDNA (0 to 10 ng) and plasmid (0 to 10 ng) with the corresponding primer sets (Table 4). qPCR mixtures consisted of 5 μl of 10 ng/μl gDNA, primer mix (0.3 μM), and SYBR green PCR mastermix (Applied Biosystems). The thermocycling parameters for the Agilent Mx3000P qPCR system (Agilent Technologies) were as follows: (i) 95°C for 15 min, (ii) 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s, and (iii) a thermal disassociation cycle of 95°C for 60 s, 55°C for 30 s, and incremental increases of the temperature to 95°C for 30 s. The samples were measured in triplicate. Averages and standard deviations of the results from a minimum 2 independent transformants were calculated.

Fluorescence microscopy.

F. casuarinae strain CcI3 and E. coli cells containing the pHKT1 plasmid were observed by fluorescence microscopy. Frankia cells with pHKT1 were grown for 7 days in MPN growth medium supplemented with 20 μg/ml tetracycline. As a control, Frankia cells without the plasmid were also grown for 7 days in MPN growth medium without antibiotics. The control E. coli(pHTK1) strain was grown overnight in LB medium with tetracycline. Cells were observed under an Olympus BH-2 microscope without sample preparation. The GFP was excited at 488 nm and observed under ×400 magnification. Images were treated with the QImaging software.

Plant inoculation and bacterial isolation from plant.

Three 2-month-old Casuarina glauca plants were inoculated with 2 ml of a concentrated culture of F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pHKT1) transformant. After 2 months incubation, an average of 35 nodules per plant were collected and sterilized (41). After a week of incubation in LB medium, 6 nodules were crushed with a sterile mortar. The mixture was plated on MPN medium–2% agar with an MPN–0.8% agar top layer. A month later, single Frankia colonies appeared on the plates. Liquid cultures were started, and the total gDNA was extracted from these colonies 2.5 months after plating.

Cloning and expression of a potential salt tolerance gene.

The CcI6_RS22605 gene was amplified by PCR from Frankia sp. strain CcI6 gDNA using a specific primer set (Table 4). The amplicon was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit protocol (Qiagen Sciences) and digested by the enzymes SpeI and ApaI (New England BioLabs, MA), as was pBBR1MCS-3. The digestion mixtures were purified using the same QIAquick PCR purification kit and ligated. The construct was introduced by chemical transformation into competent NEB5α competent E. coli cells (New England BioLabs). The construct was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. The confirmed construction was introduced into the donor E. coli BW29427 by electrotransformation and mated into Frankia spp., as described above.

Endpoint RT-PCR.

An endpoint RT-PCR was used to confirm the expression of the cloned gene (CcI6-RS22605) in F. casuarinae strain CcI3(pBBR1MCS-3-22605) transformants. RNA extraction was done using a Triton X-100 method (38, 39). DNA was removed by DNase I treatment (New England BioLabs, MA).

cDNA synthesis was performed using the GoScript reverse transcription system, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). RNA (300 ng) and primers (20 μM) for the CcI6-22605 gene (Table 4) were denatured at 70°C for 5 min before the addition of 1 μl of GoScript reverse transcriptase, 4 μl GoScript 5× reaction buffer, MgCl2, 0.5 mM dinucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 μl. The primers were annealed at 25°C for 5 min and extended at 42°C for 60 min. The cDNA (500 ng) was used as the template for PCR using forward and reverse gene-specific primers (Table 4). The thermal cycling conditions included initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 30 s (94°C), primer annealing for 30 s (58°C), and extension for 2.5 min (72°C), with a final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. PCR amplicons were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Salt sensitivity assay.

The salt tolerance levels of Frankia strains were determined by measuring the total cellular protein content after growth under salt stress, as described previously (30). Briefly, cells were grown in propionate basal medium with 5 mM NH4Cl containing different NaCl concentrations (0 mM, 200 mM, 400 mM, 600 mM, 800 mM, and 1,000 mM). The inoculum was adjusted to 40 μg/ml total protein, and the 24-well plates were incubated at 28°C for 14 days. Growth was measured by total cellular protein content using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher). Relative growths under different salt treatments were evaluated by comparison to the initial growth without salt after 14 days. To compare the different strains, the growth curves were standardized at 0 mM NaCl to 300 μg/ml protein.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Partial funding was provided by the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station. This project was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch grant 022821 (to L.S.T.), the Plant Health and Production and Plant Products Program grant number 2015-67014-22849/project accession no. 1005242 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (to L.S.T.), and the College of Life Science and Agriculture at the University of New Hampshire—Durham. A Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) from the University of New Hampshire—Durham supported V.A.K.

We declare no competing interests.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00957-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Normand P, Benson DR, Berry AM, Tisa LS. 2014. Family Frankiaceae, p 339–356. In Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F (ed), The prokaryotes—Actinobacteria. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaia EE, Wall LG, Huss-Danell K. 2010. Life in soil by the actinorhizal root nodule endophyte Frankia. A review. Symbiosis 51:201–226. doi: 10.1007/s13199-010-0086-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diagne N, Arumugam K, Ngom M, Nambiar-Veetil M, Franche C, Narayanan KK, Laplaze L. 2013. Use of Frankia and actinorhizal plants for degraded lands reclamation. Biomed Res Int 2013:948258. doi: 10.1155/2013/948258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diagne N, Ngom M, Djighaly PI, Ngom D, Ndour B, Cissokho M, Faye MN, Sarr A, Sy MO, Laplaze L, Champion A. 2015. Remediation of heavy-metal-contaminated soils and enhancement of their fertility with actinorhizal plants, p 355–366. In Sherameti I, Varma A (ed), Heavy metal contamination of soils. Soil biology, vol 44 Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngom M, Oshone R, Diagne N, Cissoko M, Svistoonoff S, Tisa LS, Laplaze L, Sy MO, Champion A. 2016. Tolerance to environmental stress by the nitrogen-fixing actinobacterium Frankia and its role in actinorhizal plants adaptation. Symbiosis 70:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s13199-016-0396-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Normand P, Lapierre P, Tisa LS, Gogarten JP, Alloisio N, Bagnarol E, Bassi CA, Berry AM, Bickhart DM, Choisne N, Couloux A, Cournoyer B, Cruveiller S, Daubin V, Demange N, Francino MP, Goltsman E, Huang Y, Kopp OR, Labarre L, Lapidus A, Lavire C, Marechal J, Martinez M, Mastronunzio JE, Mullin BC, Niemann J, Pujic P, Rawnsley T, Rouy Z, Schenowitz C, Sellstedt A, Tavares F, Tomkins JP, Vallenet D, Valverde C, Wall LG, Wang Y, Medigue C, Benson DR. 2007. Genome characteristics of facultatively symbiotic Frankia sp. strains reflect host range and host plant biogeography. Genome Res 17:7–15. doi: 10.1101/gr.5798407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Normand P, Queiroux C, Tisa LS, Benson DR, Rouy Z, Cruveiller S, Medigue C. 2007. Exploring the genomes of Frankia. Physiol Plant 130:331–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.00918.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tisa LS, Oshone R, Sarkar I, Ktari A, Sen A, Gtari M. 2016. Genomic approaches toward understanding the actinorhizal symbiosis: an update on the status of the Frankia genomes. Symbiosis 70:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s13199-016-0390-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson DR, Brooks JM, Huang Y, Bickhart DM, Mastronunzio JE. 2011. The biology of Frankia sp strains in the post-genome era. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24:1310–1316. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-11-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghinet MG, Bordeleau E, Beaudin J, Brzezinski R, Roy S, Burrus V. 2011. Uncovering the prevalence and diversity of integrating conjugative elements in actinobacteria. PLoS One 6:e27846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechevalier MP, Labeda DP, Ruan JS. 1987. Studies on Frankia sp. LLR-02022 from Casuarina cunninghamiana and its mutant LLR-02023. Physiol Plant 70:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1987.tb06140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faure-Raynaud M, Daniere C, Moiroud A, Capellano A. 1990. Preliminary characterization of an ineffective Frankia derived from a spontaneously neomycin-resistant strain. Plant Soil 129:165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF00032409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cournoyer B, Normand P. 1994. Characterization of a spontaneous thiostrepton-resistant Frankia alni infective isolate using PCR-RFLP of nif and glnII genes. Soil Biol Biochem 26:553–559. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(94)90242-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caru M, Cabello A. 1998. Isolation and characterization of the symbiotic phenotype of antibiotic-resistant mutants of Frankia from Rhamnaceae. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 14:205–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1008877912424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers AK, Tisa LS. 2004. Isolation of antibiotic-resistant and antimetabolite-resistant mutants of Frankia strains Eul1c and Cc1.17. Can J Microbiol 50:261–267. doi: 10.1139/w04-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakoi K, Yamaura M, Kamiharai T, Tamari D, Abe M, Uchiumi T, Kucho KI. 2014. Isolation of mutants of the nitrogen-fixing actinomycete Frankia. Microbes Environ 29:31–37. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME13126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucho K, Tamari D, Matsuyama S, Nabekura T, Tisa LS. 2017. Nitrogen fixation mutants of the actinobacterium Frankia casuarinae CcI3. Microbes Environ 32:344–351. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME17099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Normand P, Simonet P, Butour JL, Rosenberg C, Moiroud A, Lalonde M. 1983. Plasmids in Frankia sp. J Bacteriol 155:32–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Normand P, Downie JA, Johnston AW, Kieser T, Lalonde M. 1985. Cloning of a multicopy plasmid from the actinorhizad nitrogen-fixing bacterium Frankia sp. and determination of its restriction map. Gene 34:367–370. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.John TR, Rice JM, Johnson JD. 2001. Analysis of pFQ12, a 22.4-kb Frankia plasmid. Can J Microbiol 47:608–617. doi: 10.1139/w01-050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JD, John TR, Rice JM. 1999. DNA sequence analysis of a Frankia plasmid. FASEB J 13:A1362. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X, Kong R, de Bruijn FJ, He SY, Murry MA, Newman T, Wolk CP. 2002. DNA sequence and genetic characterization of plasmid pFQ11 from Frankia alni strain CpI1. FEMS Microbiol Lett 207:103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavire C, Louis D, Perriere G, Briolay J, Normand P, Cournoyer B. 2001. Analysis of pFQ31, a 8551-bp cryptic plasmid from the symbiotic nitrogen-fixing actinomycete Frankia. FEMS Microbiol Lett 197:111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cournoyer B, Normand P. 1992. Electropermeabilization of Frankia intact-cells to plasmid DNA. Acta Oecol 13:369–378. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers AK, Tisa LS. 2003. Effect of electroporation conditions on cell viability of Frankia EuI1c. Plant Soil 254:83–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1024986611913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucho K, Kakoi K, Yamaura M, Higashi S, Uchiumi T, Abe M. 2009. Transient transformation of Frankia by fusion marker genes in liquid culture. Microbes Environ 24:231–240. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME09115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomlin KL, Clark SRD, Ceri H. 2004. Green and red fluorescent protein vectors for use in biofilm studies of the intrinsically resistant Burkholderia cepacia complex. J Microbiol Methods 57:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antoine R, Locht C. 1992. Isolation and molecular characterization of a novel broad-host-range plasmid from Bordetella bronchiseptica with sequence similarities to plasmids from Gram-positive organisms. Mol Microbiol 6:1785–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith MAB. 1998. Bacterial fitness and plasmid loss: the importance of culture conditions and plasmids size. Can J Microbiol 44:351–355. doi: 10.1139/w98-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshone R, Ngom M, Chu F, Mansour S, Sy MO, Champion A, Tisa LS. 2017. Genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches towards understanding the molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance in Frankia strains isolated from Casuarina trees. BMC Genomics 18:633. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pesce C, Kleiner VA, Tisa LS. 2019. Simple colony PCR procedure for the filamentous actinobacteria Frankia. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 112:109–114. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plaggenborg R, Overhage J, Loos A, Archer JAC, Lessard P, Sinskey AJ, Steinbuchel A, Priefert H. 2006. Potential of Rhodococcus strains for biotechnological vanillin production from ferulic acid and eugenol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 72:745–755. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. 4 new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pbbr1mcs, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elzer PH, Kovach ME, Phillips RW, Robertson GT, Peterson KM, Roop RM II.. 1995. In vivo and in vitro stabilitty of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS in six Brucella species. Plasmid 33:51–57. doi: 10.1006/plas.1995.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovach ME, Phillips RW, Elzer PH, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1994. Pbbr1mcs—a broad-host-range cloning vector. Biotechniques 16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klumpp S, Zhang Z, Hwa T. 2009. Growth rate-dependent global effects on gene expression in bacteria. Cell 139:1366–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tisa L, McBride M, Ensign JC. 1983. Studies of growth and morphology of Frankia strains EAN1pec, EUI1c, CpI1, and ACN1AG. Can J Bot 61:2768–2773. doi: 10.1139/b83-306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tisa LS, Chval MS, Krumholz GD, Richards J. 1999. Antibiotic resistance patterns of Frankia strains. Can J Bot 77:1257–1260. doi: 10.1139/b99-067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray MG, Thompson WF. 1980. Rapid isolation of high molecular-weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee C, Kim J, Shin SG, Hwang S. 2006. Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol 123:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghodhbane-Gtari F, Nouioui I, Hezbri K, Lundstedt E, D’Angelo T, McNutt Z, Laplaze L, Gherbi H, Vaissayre V, Svistoonoff S, Ahmed H, Boudabous A, Tisa LS. 2019. The plant-growth-promoting actinobacteria of the genus Nocardia induces root nodule formation in Casuarina glauca. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 112:75–90. doi: 10.1007/s10482-018-1147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehan M, Furnholm T, Finethy RH, Chu FX, El-Fadly G, Tisa LS. 2014. Copper tolerance in Frankia sp. strain EuI1c involves surface binding and copper transport. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:8005–8015. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5849-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith SS, Michael MZ, Graham MW. 1989. Quantitative-evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res 17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Z, Lopez MF, Torrey JG. 1984. A comparison of cultural-characteristics and infectivity of Frankia isolates from root-nodules of Casuarina species. Plant Soil 78:79–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02277841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mansour SR, Mouussa LAA. 2005. Role of gamma-radiation on spore germination and infectivity of Frankia strains CeI523 and CcI6 isolated from Egyptian Casuarina. Isotope Radiat Res 37:1023–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker D, Newcomb W, Torrey JG. 1980. Characterization of an ineffective actinorhizal micro-symbiont, Frankia sp. Eui1 (Actinomycetales). Can J Microbiol 26:1072–1089. doi: 10.1139/m80-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lalonde M, Calvert HE, Pine S. 1981. Isolation and use of Frankia strains in actinorhizae formation, p 296–299. In Gibson AH, Newton WE (ed), Current perspectives in nitrogen fixation. Australian Academy of Science, Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Girgis MGZ, Ishac YZ, El-Haddad M, Saleh EA, Diem HG, Dommergues YR. 1990. First report on isolation and culture of effective Casuarina-compatible strains of Frankia from Egypt, p 156–164. In El-Lakany MH, Turnbull JW, Brewbaker JL (ed), 2nd International Casuarina Workshop. American University, Cairo, Egypt. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.