Abstract

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and aggressive cancer that arises from the mesothelial surface of the pleural and peritoneal cavities, the pericardium, and rarely, the tunica vaginalis. The incidence of MPM is expected to increase worldwide in the next two decades. However, even with the use of multimodality treatment, MPM remains challenging to treat, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5%. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer has gathered experts in different areas of mesothelioma research and management to summarize the most significant scientific advances and new frontiers related to mesothelioma therapeutics.

Keywords: Malignant pleural mesothelioma, Oncology therapeutics, Biomarkers, Immunotherapy, Chemotherapy

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and aggressive neoplasm primarily affecting the pleural cavity.1,2 MPM is a male-predominant disease, with approximately 80% of cases resulting from occupational or environmental asbestos exposure.3–7 Asbestos is a name that was used for regulatory purposes in the United States to identify six of about 400 mineral fibers that were used commercially; thus, many millions of people have been exposed to asbestos worldwide.8 Although in most of the Western countries the use of asbestos is presently forbidden, MPM incidence is expected to increase in many countries in which asbestos either has not yet been banned or is still largely used. Moreover, increased development of rural areas, has caused exposure to carcinogenic fibers that are naturally present in the environment, including asbestos and nonregulated fibers,9,10 and there is evidence of a third wave of mesothelioma in industrialized countries owing to renovation of asbestos-containing buildings.11 It is anticipated that 500,000 new cases of MPM among men with occupational exposure will be diagnosed in Europe alone.12

MPM is characterized as having a very poor prognosis, with a median survival between 12 and 18 months and a 5-year survival rate less than 5%. Survival time is considerably shorter for patients in whom sarcomatoid mesothelioma has been diagnosed (median survival 12 months).12–16 This poor prognosis is mostly due to a lack of reliable tools for screening and the lack of effective systemic therapy.13,14 Moreover, surgery with curative intent can be attempted in only a minority of patients because of the stage at which the diagnosis is made.17,18 Significant insights about the carcinogenesis of asbestos and other fibers and the genetics of MPM have been achieved in recent years,16,19–24 and preclinical results25–27 have also paved the way for innovative therapies.28 In contrast, immunotherapy, which has achieved significant results in a subset of patients with cancer (i.e., melanoma, lung cancer, and renal carcinoma), has not shown the same efficacy in MPM.29 Therefore, more translational research and biological models are needed to move forward and improve the survival of patients with MPM.

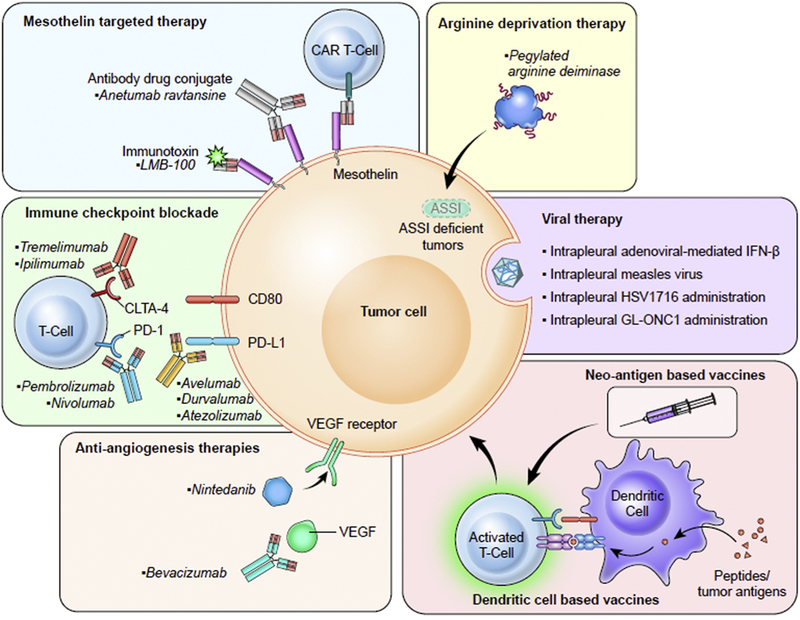

This review article will discuss the most significant scientific advances and new opportunities related to mesothelioma research and management (see Fig. 1 and Table 130).

Figure 1.

Different approaches to treating mesothelioma that are currently in clinical trials. Nintedanib, in addition to targeting VEGF receptor, also targets fibroblast growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Abbreviations: CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyteassociated antigen; PD-1, programmed death 1; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; ASS1, argininosuccinate synthetase 1; IFN-β, interferon beta; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table 1.

Prospective Therapies and Trials for Mesothelioma

| Therapy | Treatment | Identifier/Reference | Phase | Status/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis inhibition | Thalidomide | ISRCTN13632914 | III | No noted benefit in time to disease progression |

| Bevacizumab | NCT00027703 | II | Addition of bevacizumab to gemcitabine/cisplatin treatment did not improve overall or progressionfree survival in advanced malignant mesothelioma | |

| Bevacizumab | NCT00651456 | II/III | Addition of bevacizumab to cisplatin and pemetrexed improved significantly overall survival (by 2 mo) in newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma | |

| Axitinib | NCT01211275 | II | Axitinib was well tolerated, but there was a lack of clinical benefit | |

| Nintedanib | NCT01907100 | II/III | Improvement of progression-free survival/recruiting | |

| Cediranib | NCT00243074 | II | End point was not achieved | |

| Cediranib | NCT00309946 | II | End point was not achieved | |

| Cediranib | NCT01064648 | I | Active but not recruiting | |

| FAK inhibition | Defactinib | NCT02004028 | II | Completed, no results posted |

| Defactinib | NCT01870609 | II | Terminated | |

| Defactinib | NCT02758587 | I/II | Recruiting—study will assess combination of defactinib with PD-1 inhibition | |

| Antimesothelin | Amatuximab | NCT00738582 | II | Amatuximab in combination with pemetrexed and cisplatin was well tolerated; however, no significant difference in progression-free survival was seen |

| SS1P immunotoxin | NCT01362790 | I/II | Study ongoing | |

| Arginine deprivation | ADI PEG 20 | NCT01279967 | II | Improvement in progression-free survival |

| ADI PEG 20 | NCT02709512 | II/III | Recruiting—study will assess combination of ADI PEG 20 with cisplatin/pemetrexed | |

| Immunogene therapy | Intrapleural adenoviral-mediated interferon-alfa 2b | NCT01119664 | I/II | Study ongoing—study will assess combination of intrapleural adenoviral-mediated interferon-alfa 2b in combination with chemotherapy |

| NCT01212367 | I | Intrapleural administration of adenoviral-mediated interferon-alfa 2b showed potential therapeutic benefits | ||

| IL-2 administration | Astoul et al.30 (1998) | II | IL-2 administration was well tolerated and had an antitumour activity in patients with MPM | |

| CP-870, 893 (CD40-activating antibody) | ACTRN12609000294257 | I | Objective response rates were similar to those with chemotherapy alone (rather than CP-870,893 in combination with chemotherapy), but 3 patients achieved long-term survival | |

| Cell therapy | Dendritic cell vaccination | NCT01241682 | I | Treatment was well tolerated and showed signs of clinical activity |

| Immune checkpoint inhibition | Tremelimumab | NCT01843374 | II | No statistically significant difference in survival |

| Pembrolizumab | NCT02054806 | I | Study ongoing, but preliminary results show common side effects and a partial response of 20% | |

| Nivolumab | NCT02899299 | III | Recruiting—study will assess combination of nivolumab with ipilimumab | |

| NCT02497508 | II | Study ongoing | ||

| NCT02341625 | I/II | Recruiting—study will assess BMS-986148 (antimesothelin) with or without nivolumab | ||

| NCT02716272 | II | Study ongoing | ||

| Pembrolizumab | NCT02707666 | I | Recruiting—study will assess the use of pembrolizumab and cisplatin and pemetrexed | |

| MEDI4736 | NCT02592551 | II | Recruiting—study will assess MEDI4736 (PD-1 inhibitor) with or without tremelimumab | |

| WT1 vaccination |

SLS-001 | NCT01265433 | II | Results presented at ASCO indicated that a trend toward survival was observed; however, the trial was originally not powered to determine this effect |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibition | Dasatinib | NCT00652574 | I | Study ongoing |

| Radiotherapy | Prophylactic radiotherapy | ISRCTN72767336 | III | No benefit observed |

| Palliative radiotherapy | ISRCTN66947249 | II | Radiotherapy as pain relief was effective for a proportion of patients | |

| Radical hemithoracic radiation | Rusch et al. (2001)65 | II | Trial assessed the role of radical hemithoracic radiation after surgery and showed prolonged survival in early-stage tumors | |

| Hemithoracic intensity-modulated pleural radiation therapy (IMPRINT) | NCT00715611 | II | Hemithoracic IMPRINT was safe with an acceptable rate of radiation pneumonitis | |

| Accelerated intensity-modulated radiation therapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy | NCT00797719 | I/II | Median survival for all patients was 36 months, and this approach has become the preferred option for resectable MPM | |

| Viral therapy | Intrapleural adenoviral-mediated interferon beta | NCT00066404 | I | The approach was safe, promoted disease stability, and induced immune responses; however, side effects were seen at all doses |

| Intrapleural measles virus | NCT01503177 | I | Recruiting—study will assess the side effects and doses for the use of a measles virus encoding a thyroidal sodium iodide symporter | |

| Intrapleural administration of HSV1716 (mutated herpes simplex virus) | NCT01721018 | I/II | Study ongoing | |

| Intrapleural administration of GL-ONC1 (genetically modified vaccinia virus) | NCT01766739 | I | Study ongoing | |

ADI PEG 20, pegylated deiminase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; PD-1, programmed death 1, MPM, malignant pleural mesothelioma; IL-2, interleukin 2; WT1, Wilms tumor 1; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Mesothelioma Biomarkers

Biomarkers are generally a useful clinical tool and can be used to search for risk, for early detection, and for prediction of the effectiveness of treatment of MPM. Of these blood-based biomarkers, mesothelin is the one that has been extensively studied.31–33

Mesothelin is a cell surface protein with normal expression limited to mesothelial cells lining the pleura, peritoneum, and pericardium, but it is also highly expressed in many cancers, including malignant meso thelioma.34 Mesothelin can be shed from the cell surface and is found in the blood, urine, and tumor-associated fluids.

In the first study of mesothelin as a potential diagnostic biomarker for mesothelioma, 87% of patients with mesothelioma had increased levels in the serum compared with healthy asbestos-exposed and non-asbestos-exposed controls and individuals with other malignant or inflammatory lung and pleural diseases. The high specificity of serum mesothelin for mesothelioma has been confirmed in additional studies.35 Increased levels of mesothelin in pleural effusion may be useful in the context of the cytological findings suggestive of malignancy (atypical, nonmalignant, or nondiagnostic) as an adjunct to the diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma. In one study, effusion mesothelin had a sensitivity of 67% for pleural malignant mesothelioma at 95% specificity.36 In more than 47% of cases of pleural malignant mesothelioma, the level of mesothelin was increased in effusions obtained before a definitive diagnosis of pleural malignant mesothelioma had been established. Serum mesothelin level may be useful for monitoring response to treatment. In a study of 55 patients who received chemotherapy, a change in mesothelin level correlated with radiological response and change in metabolically active tumor volume. The median survival for patients with a reduction in mesothelin level after chemotherapy (19 months) was significantly longer than that for patients with increased mesothelin levels (5 months [p < 0.001]).37

The search for a good biomarker for early detection of MPM is a priority, especially for subjects with high levels of asbestos exposure. However, prospective studies have shown that monitoring serum mesothelin levels in these cohorts shows increased levels in only around 14% of individuals before diagnosis.38 The recent description of ecto-NOX disulfide-thiol exchanger 2 as a potential early detection marker is encouraging.39 Osteopontin, cancer antigen 125, hyaluronic acid, fibulin 3, and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) are some of the other biomarkers that have been studied in mesothelioma. They may have some value in prognostication, but they lack specificity.40,41 On the whole, in many laboratories these results are prompting further research for novel, more sensitive biomarkers.42

Current Standard of Care

Patients with stage I or II disease and selected patients with stage III disease may benefit from an operation, at least to improve symptoms. However, randomized trials have been difficult to conduct, as was demonstrated by the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery) randomized feasibility study, which suggested that radical surgery within trimodal therapy not only offers no benefit but possibly harms patients.

This trial was a feasibility study that highlighted the difficulty of randomizing patients to an extensive surgical procedure such as extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP).43 The goal of surgery is macroscopic complete resection with either an extended pleurectomy-decortication or an EPP. Because surgery alone is not curative, it is usually performed in the context of multimodality therapy with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.

Patients with unresectable disease are often treated with palliative systemic chemotherapy. Currently, four to six cycles of combination chemotherapy with platinum and antifolates is the standard treatment for patients with MPM. Tumor response rate with this combination is up to 30% in the randomized phase 3 trial; with this combination therapy, improvement in some cancer-related symptoms is possible and the overall survival (OS) time is approximately 1 year.44 Carboplatin is a good alternative to cisplatin, especially in elderly patients.45 Currently, there is no clear evidence supporting neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy,14 and there are no approved second- or third-line agents. Clearly, there is a desperate need to improve therapies for MPM.

New Frontiers in Mesothelioma Treatment

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapies

Designing and conducting neoadjuvant studies in MPM is a challenging effort that requires extensive multidisciplinary involvement. In addition, there is a knowledge gap, as well as a great need to develop clinical trials that yield predictive or prognostic biomarkers for mesothelioma.

Although there are very few randomized studies about possible therapies for MPM, it is standard practice to administer four cycles of cisplatin-pemetrexed (CP) as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. However, the benefit of systemic therapy has been demonstrated in the unresectable setting and most single-arm trials have shown a survival benefit over historical controls with the addition of systemic therapy. Trimodality therapy (systemic chemotherapy, surgical resection, and radiation) yields median OS times between 16.6 and 25.5 months.46–53 It has been surmised that although surgical and radiotherapy techniques can be optimized for mesothelioma, the greatest challenge is eliminating microscopic disease; therefore, there is a critical need to improve systemic therapies and clarify the best sequence of therapies.

Although the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting provides significant opportunities to conduct translational research with the acquisition of blood and tissue, successfully conducting trials in this space has remained a challenge. Neoadjuvant platinum-doublet chemotherapy has given response rates between 29% and 44%,48,51 and prospective trials suggest that the responders have improved survival outcomes.48 However, in mesothelioma, neoadjuvant therapy carries inherent risks of potentially delaying surgery or predisposing patients to postoperative complications. This is of concern in MPM, as EPP completion rates in prior clinical trials conducted at high-volume centers have ranged from 42% to 84%.46–48,50–52,54,55 Although adjuvant systemic therapy does not affect the surgical resection, there are significant concerns that it is often inadequate on account of dose reductions, treatment delays, or cessation of therapy secondary to poor tolerance by patients. Adding novel agents to trimodality or bimodality therapy may improve outcomes; however, it is essential that these agents (if given in the neoadjuvant setting) contribute to an antitumor effect with tumor shrinkage while maintaining nonoverlapping or relatively low toxicity. In addition, to assist with reducing residual microscopic disease after resection, these agents must have a reasonable adverse event (AE) profile that will allow them to potentially be administered in the adjuvant maintenance setting.

This article reviews three distinct examples of mesothelioma trial designs that have incorporated novel agents or immunotherapies into multimodality treatment. These examples include an adjuvant vaccine trial, a neoadjuvant window of opportunity biomarker-based trial, and a neoadjuvant chemotherapy with an oral antiangiogenic agent.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has been pioneering the use of an adjuvant Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) vaccine (galinpepimut-S), which consists of four peptides (three to stimulate common HLA-DR expressing cells and one for HLA-A0201 cells) with an immunologic adjuvant called Montanide ISA 51 UFCH (Seppic, Fairfield, NJ). It is administered every other week for 10 weeks postoperatively. Eligible patients were required to express WT1 (according to immunohistochemistry [IHC]) on their mesothelioma tumor cells. A phase II randomized study that was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in 2016 included data from 40 patients with mesothelioma who were IHC positive for WT1, had completed trimodality therapy, and had no evidence of disease. Galinpepimut-S was administered every other week for 10 weeks postoperatively. Galinpepimut-S showed a trend toward an improved median progression-free survival (PFS) (11.4 versus 5.7 months, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.69, p = 0.3) and median OS (21.4 versus 16.6 months, HR = 0.52, p = 0.14) over the placebo control arm. According to the subgroup analysis, the largest benefit was in the group of patients with an R0 resection, in which the median OS time was 39.3 months compared with 24.8 months in the control arm (p = 0.04).56

In the second example, a biomarker-based window of opportunity trial that was conducted at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, demonstrated that it is feasible and safe to orally administer neoadjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) agents before surgical resection, adjuvant radiation therapy, and adjuvant chemotherapy and then as a maintenance agent. This trial was based on preclinical studies showing that MPM cell lines and tumor cells have overexpression of activated Src kinase, and preclinical studies demonstrated antitumor efficacy of dasatinib that corresponded to dephosphorylation of the biomarker p-SrcTyr419.57 The primary end point was modulation of p-SrcTyr419 in tumor cells. Patients who exhibited biomarker modulation or a response to 4 weeks of administration of neoadjuvant dasatinib were eligible for maintenance dasatinib for 2 years. This study demonstrated that distinct patterns of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta expression according to IHC were predictive of sensitivity or resistance to dasatinib treatment.

Buikhuisen et al. reported (at the ASCO 2013 meeting) on the combination of neoadjuvant CP with and without axitinib (an oral vascular endothelial growth factor receptor [VEGFR] inhibitor) for three cycles of therapy before pleurectomy. Axitinib was administered (at a dose of 5 mg twice daily on days 2 to 19) with standard CP.58 Two tissue collections, before and after neoadjuvant therapy, were utilized with corresponding blood sampling. In the 31 patients enrolled (20 with axitinib and 11 without it), there was a higher response rate (35% versus 27%) with axitinib but no difference in median PFS or OS. The axitinib arm had higher rates of grade 2 hypertension (43% versus 0%) and grade 3 to 4 neutropenia (45% versus 9%), which did not translate into a higher rate of infectious complications. Four patients did not proceed with pleurectomy; a pulmonary embolism developed in one patient, and an arrythmia developed in one patient. Biomarker analysis for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGFR is pending. This study indicates that the antiangiogenic agent was safely given with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a low complication rate. Other antiangiogenic agents have recently become prominent in mesothelioma. For example, the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study trial reported that the addition of bevacizumab to CP significantly improved objective response rate, PFS, and OS in patients with unresectable MPM.58 There are currently ongoing trials in the neoadjuvant setting in which immunotherapies are being used in window of opportunity trials (NCT02592551 and NCT02707666) and in combination with neoadjuvant chemotherapy-atezolizumab (SWOG 1619; NCT03228537).

Radiation

Mesothelioma has been shown to be sensitive to radiation in in vitro studies and in animal models. Clinically, radiation therapy has thus been used in three different settings in MPM: (1) prophylactically for the prevention of procedure tract metastasis after large-bore pleural biopsy; (2) palliatively for treatment of pain or an area at risk of compression, such as the esophagus or superior vena cava; and (3) radically in the form of highdose hemithoracic radiation to improve local control and possibly improve survival.

Prophylactic radiation directed to large-bore biopsy sites has been performed sporadically after one small randomized study demonstrated significant reduction of port site metastasis in 19 9 5.59 After this study, two small randomized trials failed to confirm the potential benefit in prevention of port sites metastasis.60,61 A recently completed large multicenter, open-label, phase 3, randomized controlled trial (SMART) studied 203 patients who received either immediate radiotherapy (n = 102) or deferred radiotherapy after diagnosis of procedure tract metastasis (n = 101). The study demonstrated no benefit, thus suggesting abandoning this concept.62

Palliative radiation in MPM has been used for pain management, treatment of dysphagia, or relief of superior vena cava compression.63 A prospective phase II study was recently completed to assess the impact of a standardized radiation regimen of 20 Gy in five fractions on pain control at 5 weeks (SYSTEMS). Of 40 patients, 14 (35%) had improvement in pain and five (12.5%) had complete pain resolution.64 These encouraging results led to a new multicenter phase II randomized dose escalation study (SYSTEMS-2) to determine whether a higher dose of radiation (36 Gy in six fractions over 2 weeks) could provide additional benefit in terms of pain control.

Radical hemithoracic radiation in a dose of more than 50 Gy in a prospective phase II trial after EPP was reported by Rusch et al.65 Local control was excellent, with a rate of recurrence in the radiation field of only 12%. These results led to a trimodality approach with induction chemotherapy followed by EPP and radical hemithoracic radiation. The median survival time among all studies ranged from 14 to 24 months in an intention-to-treat analysis with a rate of completion of all three therapies of 33% to 71%.66 Two small multicenter randomized trials43,67 attempted to determine the benefit of EPP compared with that of chemotherapy alone (the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery randomized trial) and the benefit of hemithoracic radiation after chemotherapy and EPP (SAKK 17/04). Both trials had limitations related to the small sample size and raised concerns about the quality of the surgery or the radiation therapy, thus precluding definitive conclusions.68,69

Over the past 10 years, radical hemithoracic radiation has evolved toward two new paradigms: (1) the use of radical hemithoracic radiation as part of a lung-sparing multimodality approach (IMPRINT) and (2) the use of an accelerated course of hemithoracic radiation before EPP (SMART).70,71 Both approaches use intensity-modulated radiation therapy and have been evaluated in prospective single-arm clinical trials. The trials have demonstrated the safety of these new radical approaches in experienced centers.72–74 Further studies are currently ongoing to evaluate the potential long-term benefit of these therapeutic approaches.

In summary, prophylactic radiation of large-bore pleural biopsy sites is not superior to radiation to the biopsy tract after diagnosis of procedure tract metastasis. Palliative radiation is an option for MPM when there is a specific symptomatic site to target, but the optimal radiation regimen remains to be defined and radical hemithoracic radiation should be part of clinical trials in the context of a multimodality approach and performed in expert centers only.

Antiangiogenic Drugs

The results of earlier trials assessing antiangiogenic drugs in MPM were negative; they included the phase III study of thalidomide as maintenance treatment after CP75 and a phase II trial of bevacizumab (anti-VEGF antibody) combined with first-line cisplatin plus gemcitabine.76 To test CP with bevacizumab (CPB) or CP alone, a phase III trial (the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study trial) randomized 448 patients with unresectable MPM who had not received previous chemotherapy.77 The patients were 18 to 75 years of age, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2, and had no substantial cardiovascular comorbidity. Patients with nonprogressive disease who had been treated with CPB received bevacizumab maintenance until progression or toxicity. The primary end point, OS time, was longer in the CPB arm: 18.8 versus 16.1 months in the CP arm, (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.77, p = 0.017). Median PFS was also increased in the CPB arm: 9.2 versus 7.3 months (HR = 0.61, p < 0.001). Moreover, there was no detrimental effect of bevacizumab on quality of life despite its higher frequency of toxicities. Overall, 158 of 222 patients given PCB (71%) and 139 of 224 patients given PC (62%) had grade 3 to 4 AEs. There were more cases of grade 3 or higher hypertension (51 of 222 [23%] versus 0) and thrombotic events (13 of 222 [6%] versus 2 of 224 [1%]) with PCB than with PC. Thus, CPB provided a significantly longer survival in MPM with acceptable toxicity, making this triplet a potential treatment paradigm for these patients, and it was included in the 2016 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.78

On the basis of a similar rationale, nintedanib, which is a drug targeting VEGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, is currently being tested versus placebo in patients with MPM treated with first-line CP in a phase II/III trial (the LUME-Meso trial). In the phase II trial, 87 patients were randomly assigned to up to six cycles of pemetrexed and cisplatin plus nintedanib (200 mg twice daily) or placebo followed by nintedanib plus placebo monotherapy until progression. Primary PFS favored nintedanib (HR = 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.34–0.91, p = .017), which was confirmed in updated PFS analyses (HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.33–0.87, p = .010). A trend toward improved OS also favored nintedanib (HR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.46–1.29, p = .319). Neutropenia was the most frequent grade 3 or higher AE (43.2% with nintedanib versus 12.2% with placebo); the rates of febrile neutropenia were low (4.5% in the nintedanib group versus 0% in the placebo group). AEs leading to discontinuation were reported in 6.8% of those receiving nintedanib versus in 17.1% of those in the placebo group. Another anti-VEGFR TKI inhibitor, axitinib, failed to improve median OS and PFS in combination with CP versus chemotherapy alone.79 Additional VEGFR TKIs have been studied with frontline chemotherapy. Axitinib, a multi-targeted antiangiogenic TKI, failed to improve median OS and PFS in combination with CP versus chemotherapy alone. However, SWOG0905, which was a phase I/II trial that combined cediranib (a VEGFR inhibitor) with CP, reported a median PFS time of 8.6 months and a median OS time of 16.2 months.80 The randomized SWOG0905 phase II trial has completed enrollment and will be presented at the ASCO meeting in 2018.

In summary, the triplet CPB is a new option for selected patients and is recommended in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

Targeting Stem Cell Pathways

Cancer stem cells is a term often used to identify a subpopulation of cells within each tumor that display properties of self-renewal, pluripotency, a high proliferative capacity, and a higher ability to resist standard chemotherapy and radiation. The resistance of MPM to conventional cytotoxic drugs is due in part to subpopulations of drug-resistant stem cells, and new therapeutic strategies that specifically target this stem cell population and improve the efficacy of cytotoxic drugs are needed.81

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is overexpressed in epithelial and mesenchymal tumors and regulates cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and survival in addition to being critical for cancer stem cell survival and maintenance. FAK signaling is associated with resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy, and FAK inhibition enhances cancer cells’ sensitivity to taxanes.82 Cells with Merlin deficiency, which is common in mesothelioma, are sensitive to FAK inhibition.83 The small molecule FAK inhibitor defactinib showed promising results in preclinical studies; however, a phase II clinical trial of defactinib in mesothelioma was ended in late 2015 after interim analysis failed to show any benefit. Other FAK inhibitors remain in development, and targeting the FAK pathway in combination with other treatment strategies continues to be an area of interest.

Several other stem cell pathways, including Wnt, Hippo, and Sonic Hedgehog are active areas of drug development with promising preclinical results in mesothelioma. Wnt pathway signaling is deregulated in a large variety of cancers, promotes stem cell self-renewal in hematopoietic stem cells, and is necessary for cancer stem cells to maintain their tumorigenic potential.84,85 In mesothelioma, combining cisplatin with Wnt pathway inhibitors in vitro improves the efficacy of standard chemotherapy and induces synergistic cell cycle arrest and colony formation.86

The Hippo pathway is a highly conserved regulator of organ size and stem cell proliferation and mainte-nance.87 It is of interest in mesothelioma, as there are multiple genes in the Hippo pathway that are frequently mutated in mesothelioma.88

Another pathway of interest in mesothelioma is the Sonic Hedgehog pathway and its downstream effectors Smoothened and Gli, which control progenitor cell migration, differentiation, and proliferation and play an important role in carcinogenesis. Vismodegib, a Smoothened inhibitor that is approved for use in basal cell skin cancer, impairs MPM growth in rat models.89 The final effector of the pathway, Gli, has been shown in vitro and in xenograft models to be up-regulated in mesothelioma.90 A novel Gli inhibitor that is currently in preclinical development suppresses mesothelioma cell growth and works synergistically with pemetrexed and the Smoothened inhibitor vismodegib in mesothelioma.90

Immunotherapy

It has been known for some time that MPM is a cancer that can be sensitive to immunotherapy, and some immunotherapies are currently being tested.91 Nonetheless, at the moment there are no randomized clinical trials examining immunotherapy versus standard therapy that could provide strong support for the use of immunotherapy for MPM.

Antibodies blocking immune checkpoints that function as negative regulators of T-cell function, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), programmed death 1 (PD-1), and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) have been approved in several different cancers. In two nonrandomized studies, the anti-CTLA4 antibody tremelimumab showed preliminary evidence of activity in patients with previously treated mesothelioma.92,93 On the basis of these results, a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study investigated tremelimumab in patients with mesothelioma (the DETERMINE trial). This trial did not meet the primary end point of OS. There was no difference in OS between the tremelimumab group (median OS 7.7 months [95% CI: 6.8–8.9]) and the placebo group (median OS 7.3 months [95% CI: 5.9–8.7]).94

In the KEYNOTE-028 trial, previously treated patients with PD-L1-positive MPM received pembrolizumab (which is an anti-PD-1 antibody) in a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for up to 2 years or until confirmed progression or unacceptable toxicity. PD-L1 positivity was defined as expression in 1% or more of tumor cells by IHC. In the preliminary results, five of 25 patients (20%) had a partial response (for an objective response rate of 20%) and 13 (52%) patients had stable disease. Responses were durable (median duration of response 12.0 months [95% CI 3.7-not reached]).95 The NivoMes study, which evaluated the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolu-mab in unselected patients with previously treated mesothelioma reported response rates of 28%.96 The JAVELIN study of the anti-PDL-1 antibody avelumab in unselected patients with previously treated mesothelioma reported a response rate of 9.4% with a median PFS of 17.1 weeks. Subgroup analysis in the PD-L1-positive population (cutoff >5%) showed a response rate of 14%.97 Novel vaccine approaches using MPM neoantigens identified by gene sequencing are also entering clinical trial on the basis of early animal studies.98

Overall, the preliminary data on PD-1- and PD-L1-targeting monoclonal antibodies in MPM suggest that single-agent immunotherapy may have some benefit in this disease, possibly because of its complex biology. Additional studies are ongoing (in particular, studies assessing combinations of PD-1- or PD-L1-targeted therapies with anti-CTLA4 antibodies or with chemotherapy.99

Targeting Inflammation

MPM is causally linked to exposure to asbestos and other carcinogenic mineral fibers such as erionite and antigorite.8,100 The deposition of mineral fibers in tissues triggers a chronic inflammatory process that over the course of many years, drives asbestos carcinogenesis.19 Inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages, play an important role in this process by releasing mutagenic reactive oxygen species and various cytokines that are mutagenic and/or support inflammation.101–106 In the pleura and peritoneum, the chronic inflammation caused by asbestos is causally linked to the release of HMGB1 by primary human mesothelial cells after asbestos exposure. Human mesothelioma cells undergoing necrosis passively release HMGB1 into the extracellular space, where HMGB1 recruits macrophages, induces the secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha and other cytokines, and initiates inflammation.107 These same pathways contribute to MPM growth.20,108 The prolonged bio-persistence of asbestos fibers lodged in the pleura initiates a vicious cycle of chronic cell death and chronic inflammation that over a period of many years, can lead to MPM.105 In addition, asbestos fibers can activate NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production.109,110 Given the established role of chronic inflammation in asbestos-induced mesothelioma and the long latency between fiber exposure and cancer development, asbestos-induced inflammation is a potential therapeutic target for MPM prevention. Malignant mesothelioma biopsy specimens often show a marked inflammatory infiltrate that contains a large number of tumor-associated macrophages. Moreover, the growth of most MPM cells is dependent on HMGB1, and the tumor phenotype of HMGB1-secreting mesothelioma cells requires HMGB1 for continued growth.111 Therefore, HMGB1 is an attractive novel target to identify patients with malignant mesothelioma and possibly to treat MPM.112

Several reagents that block HMGB1 activity have been investigated and have shown promising results in vitro and in animals. These anti-HMGB1 reagents include anti-HMGB1 and anti-receptor for advanced glycation end products monoclonal antibodies, HMGB1 antagonist BoxA, and ethyl pyruvate (which inhibits HMGB1 secretion).111 In addition, HMGB1 is a novel target of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid [ASA]) and its metabolite salicylic acid (SA); it has been found that ASA treatment may delay MPM development and inhibit its progression by inhibiting HMGB1 activity.113 Daily ASA has been shown to have a protective effect against colorectal cancer and against cancers in other sites, such as breast, stomach, and prostate cancer. Although to our knowledge, the possible therapeutic effects of ASA in MPM have not been studied, we found some evidence supporting a role of ASA in preventing or possibly delaying the growth of malignant mesothelioma. Specifically, the Physician’s Health Study suggests that there may be a possible association between ASA use and reduced incidence of malignant mesothelioma.114

In addition to ASA, several other anti-inflammatory drugs have also been studied. For example, flaxseed lignan was found to be able to reduce acute asbestos-induced inflammation and thus may be a promising agent for MPM chemoprevention.115 Celecoxib, a cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor COX20 inhibitor, was shown to be able to inhibit MPM tumorigenic potential in vitro and in vivo, and it was used in a clinical trial and also tested in combination with adenovirus (ADV)-interferon and chemotherapy.116,117 IL-4R expression was found to be associated with poor survival and promotion of tumor inflammation. In addition, the IL-4/IL-4 receptor axis was proposed to be potential therapeutic target in MPM.118 Similarly, it was also recently proposed that use of anti-IL-6 be considered a potential therapeutic strategy.119

Virotherapy for MPM

The concept of using viruses for cancer therapy emerged on the basis of numerous anecdotal case reports demonstrating disease remission in patients acquiring natural viral infections. The potential therapeutic effects of these viruses have been attributed to different mechanisms. In addition to causing direct oncolytic cell death, targeted infection, and killing of the tumor cell by the virus, viral tumor cell infection is also known to trigger antitumor immune responses (viroim-munotherapy).120,121 In addition, viruses can be used to therapeutically change the infected tumor cells by gene transfer (gene therapy).120,121

Recent advances in genetic engineering have resulted in the rapid improvement of therapeutic viruses, including enhanced tumor cell-specific targeting and introduction of cargo genes to enhance the therapeutic effect of these agents. Although the inherent impairment of the type I interferon pathway in many malignant cells augments tumor cell-specific oncolysis, innate and adaptive antiviral immune responses limit the effects of oncolytic viruses.120 On the basis of promising preclinical data, various viruses, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), vaccinia virus, ADV, measles virus, reovirus, and others, have been evaluated in clinical trials across different malignancies. Many of these studies have established the safety of virotherapy and demonstrated some promising clinical response.120 In 2015 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved talimogene laherparepvec (also known as T-VEC or OncoVEXGM-CSF), which is a granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor-expressing variant of HSV type 1, for patients with melanoma.122

For MPM, virotherapy currently represents an experimental treatment strategy, and additional data are needed. Local confinement of tumor growth within the chest cavity in the absence of distant metastasis and easy access to local delivery through the pleural space have made MPM an interesting target for virotherapy. Therapeutic viruses are most commonly delivered through an intrapleural catheter. The most frequently used viral vectors in MPM have been recombinant replication incompetent ADV. Different ADV vectors encoding the suicide gene HSV thymidine kinase (Ad.HSVtk) in conjunction with gancyclovir (intravenous delivery), and interferon beta (Ad.IFNβ) or interferon alfa (Ad.IFNα) either alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy and cyclooxygenase inhibition have been investigated in several phase I/II trials.117,123–126 Studies investigating the intrapleural administration of a modified vaccine strain measles virus encoding the sodium iodine symporter (MV-NIS, NCT01503177), the modified HSV type 1 strain HSV1716 (SEPREHVIR, NCT01721018), and the attenuated modified vaccinia virus (GL-ONC1, NCT01766739) encoding several tracking genes, green fluorescent protein (GFP), β-galactosidase, and β-glucuronidase are currently ongoing. Disease responses, prolonged periods of disease control, and extended OS have been observed in virotherapy studies in mesothelioma. Combinatorial approaches with immunosuppression and cellular viral carriers to avoid viral neutralization and combinations with immune checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, and radiation to enhance the effects of the viruses on antitumor immunity are currently being considered.

Other Approaches

Preclinical studies and early-stage clinical trials have validated mesothelin as an attractive target for therapy of patients with mesothelioma, given its high and uniform expression in patients with epitheloid mesothelioma and limited expression on normal human tissues. Currently, several approaches targeting mesothelin are in clinical trials; they include immunotoxin LMB-100 (a recombinant protein consisting of antimesothelin Fab conjugated to a truncated Pseudomonas exotoxin A) and the antibody drug conjugate anetumab ravtansine (antimesothelin monoclonal antibody linked to the antitubulin DM4) In addition, phase I clinical trials of mesothelin-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cells given intravenously or in the pleural cavity are being conducted.127

Another source of hope might come from the arginine dependence that is exhibited by argininosuccinate synthetase 1 tumors such as mesothelioma, and the good results of pegylated arginine deiminase alone or in combination with CP in the phase I TRAP trial.117 A phase II/III trial (Polaris) comparing first-line CP with pegylated arginine deiminase or placebo was started in 2017 for biphasic (mixed) or sarcomatoid MPM only because they exhibit argininosuccinate synthetase 1 defect twice as frequently as the epithelioid subtype.

Finally, other innovative drugs are also candidates for first-line treatment after preliminary positive clinical trials, include gene therapy117 or cell therapy using chimeric antigen receptors or dendritic cells.128 For example, in 2018 the European DENIM phase III trial will start to test dendritic cell-based immunotherapy with allogenic tumor cell lysate as maintenance treatment after CP chemotherapy in patients with MPM.

Future Perspectives

Despite MPM being a relatively rare cancer, there are a number of ongoing clinical trials of novel therapies in MPM, including large randomized clinical trials. As we learn more about the biology of mesothelioma, it will become possible to target those mechanisms that are most critical and most commonly altered in these malignancies: it is hoped that such targeted therapies will lead to improved outcomes for patients with mesothelioma. It is also very important to conduct randomized clinical trials, which given the rarity of this malignancy, requires cooperation among expert medical centers, as in the absence of such trials it is impossible to judge with any degree of reliability the possible benefit of novel therapies.

From a clinical point of view, the translational trials should be stratified and aimed at reaching strong primary end points (e.g., OS), thus avoiding the risk recently demonstrated with surrogate end points, and the establishment of larger patient cohorts will allow a new understanding of the efficacy of the new treatments.129

From preclinical point of view, it is critical that a better understanding of MPM biology could allow us to move forward and gain ground against this disease. Amid other characteristics, the mesodermal origin of MPM offers intriguing opportunities, and likewise, the role of the microenvironment in affecting the growth of tumor cells and the immune response also offers interesting possibilities.130,131

Lastly, even though MPM cells show a relatively low mutational load that can affect the sensitivity to immunotherapy, there is no doubt that the genetics, gene-driven metabolism, and immune characteristics of this tumor are likely to unravel translational implications within the next few years.23,29,132 It will be useful in clinical trials to obtain germline and tumor samples for detailed molecular analysis of genes that may influence disease occurrence or outcomes, such as BRCA1 associated protein 1 gene (BAP1), and mutations and transcriptomes that might inform therapeutic choices and prognosis and clarify the molecular basis of response or progression.

Ultimately, although there have been repeated failures in the development of novel therapeutics for mesothelioma, we have recently achieved a better understanding of the basic biology behind mesothelioma development, and this is paving the way for better therapeutics and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work has in part been supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health. We than PhD students Emyr Bakker and Alice Guazzelli, and Erina He from the Medical Arts Department, National Institutes of Health, for helping to create Table 1 and Figure 1.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Scherpereel reports personal fees from BMS, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Roche for service on advisory boards, as well as fees to his institution from BMS, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Epizyme, Bayer, and Roche for serving as principal investigator or coprincipal investigatory on clinical trials outside the submitted work. Dr. Tsao reports grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, Genentech, the American Cancer Society, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medimmune, Millennium, Polaris Pharmaceuticals, Seattle Genetics, Verastem, the Department of Defense, and GlaxoSmith Kline Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from Clinical Care Options for speakers bureau participation; and personal fees from Genentech and Merck for serving on advisory boards outside the submitted work. Dr. de Perrot reports personal fees from Bayer and Merck outside the submitted work. Dr. Hirsch is coinventor of a University of Colorado-owned patent titled “EGFR Immunohistochemistry and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization as Predictive Biomarkers for EGFR Therapy.” Dr. Hirsch has participated in advisory boards for BMS, Genentech/Roche, HTG, Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and Ventana, and Dr. Hirsch’s laboratory has received research grants (through the University of Colorado) from Genentech, BMS, Lilly, Bayer, and Clovis. Dr. Carbone reports grants from National Institutes of Health/ National Cancer Institute, the Department of Defense, V Foundation for Cancer Research, University of Hawaii Foundation (Pathogenesis of Malignant Mesothelioma) through donations from Honeywell International, Inc., and Riviera United-4-a Cure (which had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript) during the conduct of the study. Dr. Carbone has pending patent applications on BAP1, a patent titled “Using Anti-HMGB1 Monoclonal Antibody or Other HMGB1 Antibodies as a Novel Mesothelioma Therapeutic Strategy” (Patent No. 9,561,274 issued), and a patent titled “HMGB1 as a Biomarker for Asbestos Exposure and Mesothelioma Early Detection (Application No. 14/123,722, Patent No. 9,244,074 pending). In addition, as a board-certified pathologist, Dr. Carbone provides diagnostic expertise on mesothelioma to lawyers representing various parties.

The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

References

- 1.Ismail-Khan R, Robinson LA, Williams CC Jr, Garrett Cr, Bepler G, Simon GR Malignant pleural mesothelioma: a comprehensive review. Cancer Control. 2006;13: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segura-Gonzalez M, Urias-Rocha J, Castelan-Pedraza J. Malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis: a rare neoplasm-case report and literature review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:e401–e405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jasani B, Gibbs A. Mesothelioma not associated with asbestos exposure. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136: 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roe OD, Stella GM. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: history, controversy and future of a manmade epidemic. Eur Respir Rev. 2015;24:115–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carbone M Simian virus 40 and human tumors: it is time to study mechanisms. J Cell Biochem. 1999;76:189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazdar AF, Carbone M. Molecular pathogenesis of malignant mesothelioma and its relationship to simian virus 40. Clin Lung Cancer. 2003;5:177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbone M, Rizzo P, Pass H. Simian virus 40: the link with human malignant mesothelioma is well established. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:875–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumann F, Ambrosi JP, Carbone M. Asbestos is not just asbestos: an unrecognised health hazard. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumann F, Buck BJ, Metcalf RV, McLaurin BT, Merkler DJ, Carbone M. The presence of asbestos in the natural environment is likely related to mesothelioma in young individuals and women from Southern Nevada. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:731–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone M, Baris YI, Bertino P, et al. Erionite exposure in North Dakota and Turkish villages with mesothelioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13618–13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen NJ, Franklin PJ, Reid A, et al. Increasing incidence of malignant mesothelioma after exposure to asbestos during home maintenance and renovation. Med J Aust. 2011;195:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peto J, Decarli A, La Vecchia C, Levi F, Negri E. The European mesothelioma epidemic. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:666–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fennell DA, Gaudino G, O’Byrne KJ, Mutti L, van Meerbeeck J. Advances in the systemic therapy of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherpereel A, Astoul P, Baas P, et al. Guidelines of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons for the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:479–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creaney J, Robinson BW. Malignant mesothelioma biomarkers - from discovery to use in clinical practise for diagnosis, monitoring, screening and treatment. Chest. 2017;152:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bononi A, Napolitano A, Pass HI, Yang H, Carbone M. Latest developments in our understanding of the pathogenesis of mesothelioma and the design of targeted therapies. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2015;9: 633–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricciardi S, Cardillo G, Zirafa CC, et al. Surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: an international guidelines review. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:S285–S292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumann F, Flores E, Napolitano A, et al. Mesothelioma patients with germline BAP1 mutations have 7-fold improved long-term survival. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36: 76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillegass JM, Shukla A, Lathrop SA, et al. Inflammation precedes the development of human malignant mesotheliomas in a SCID mouse xenograft model. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1203:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altomare DA, Menges CW, Pei J, et al. Activated TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB signaling via down-regulation of Fas-associated factor 1 in asbestos-induced mesotheliomas from Arf knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3420–3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo G, Chmielecki J, Goparaju C, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals frequent genetic alterations in BAP1, NF2, CDKN2A, and CUL1 in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasu M, Emi M, Pastorino S, et al. High incidence of somatic BAP1 alterations in sporadic malignant mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:565–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48:407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bononi A, Yang H, Giorgi C, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations induce a Warburg effect. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1694–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mutti L, Valle MT, Balbi B, et al. Primary human mesothelioma cells express class II MHC, ICAM-1 and B7–2 and can present recall antigens to autologous blood lymphocytes. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valle MT, Porta C, Megiovanni AM, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta released by PPD-presenting malignant mesothelioma cells inhibits interferon-gamma synthesis by an anti-PPD CD4+ T-cell clone. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutti L, Broaddus VC. Malignant mesothelioma as both a challenge and an opportunity. Oncogene. 2004;23:9155–9161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guazzelli A, Hussain M, Krstic-Demonacos M, Mutti L. Tremelimumab for the treatment of malignant mesothelioma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1819–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2500–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asoul P, Picat-Joossen D, Viallat JR, Boutin C. Intra-pleural administration of interleukin-2 for the treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a Phase II study. Cancer. 1998;83:2099–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlou MP, Diamandis EP. Validation of candidate protein biomarkers In: Ginsburg GF, Huntington FW, eds. Genomic and Personalized Medicine. 2nd ed London, United Kingdom: Elsevier; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, et al. Mesothelin-family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma. Lancet. 2003;362:1612–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan R, Remaley AT, Sampson ML, et al. Detection and quantitation of serum mesothelin, a tumor marker for patients with mesothelioma and ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastan I, Hassan R. Discovery of mesothelin and exploiting it as a target for immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2907–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollevoet K, Reitsma JB, Creaney J, et al. Serum mesothelin for diagnosing malignant pleural mesothelioma: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1541–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creaney J, Segal A, Olsen N, et al. Pleural fluid mesothelin as an adjunct to the diagnosis of pleural malignant mesothelioma. Dis Markers. 2014;2014: 413946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creaney J, Francis RJ, Dick IM, et al. Serum soluble mesothelin concentrations in malignant pleural mesothelioma: relationship to tumor volume, clinical stage and changes in tumor burden. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Creaney J, Olsen NJ, Brims F, et al. Serum mesothelin for early detection of asbestos-induced cancer malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2238–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morre DJ, Hostetler B, Taggart DJ, et al. ENOX2-based early detection (ONCOblot) of asbestos-induced malignant mesothelioma 4–10 years in advance of clinical symptoms. Clin Proteomics. 2016;13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creaney J, Dick IM, Robinson BW. Comparison of mesothelin and fibulin-3 in pleural fluid and serum as markers in malignant mesothelioma. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Gaudino G, Pass HI, Carbone M, Yang H. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for malignant mesothelioma: an update. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creaney J, Dick IM, Robinson BW. Discovery of new biomarkers for malignant mesothelioma. Curr Pulmonol Rep. 2015;4:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treasure T, Lang-Lazdunski L, Waller D, et al. Extrapleural pneumonectomy versus no extra-pleural pneumonectomy for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinical outcomes of the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) randomised feasibility study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:763–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2636–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceresoli GL, Zucali PA, Favaretto AG, et al. Phase II study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1443–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weder W, Stahel RA, Bernhard J, et al. Multicenter trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1196–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weder W, Kestenholz P, Taverna C, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3451–3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krug LM, Pass HI, Rusch VW, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy and radiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3007–3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flores RM, Krug LM, Rosenzweig KE, et al. Induction chemotherapy, extrapleural pneumonectomy, and postoperative high-dose radiotherapy for locally advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma: a phase II trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rea F, Marulli G, Bortolotti L, et al. Induction chemotherapy, extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) and adjuvant hemi-thoracic radiation in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): feasibility and results. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Schil PE, Baas P, Gaafar R, et al. Trimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: results from an EORTC phase II multicentre trial. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:1362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Federico R, Adolfo F, Giuseppe M, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by surgery and radiation in the treatment of pleural mesothelioma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Batirel HF, Metintas M, Caglar HB, et al. Trimodality treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flores RM. Induction chemotherapy, extrapleural pneumonectomy, and radiotherapy in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. Lung Cancer. 2005;49(suppl 1):S71–S74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Opitz I, Kestenholz P, Lardinois D, et al. Incidence and management of complications after neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zauderer MG, Dao T, Rusch VW, et al. Randomized phase II study of adjuvant WT1 vaccine (SLS-001) for malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) after multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:8519–8519. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsao AS, He D, Saigal B, et al. Inhibition of c-Src expression and activation in malignant pleural mesothelioma tissues leads to apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and decreased migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1962–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buikhuisen WA, Vincent AD, Scharpfenecker MM, et al. A randomized phase II study adding axitinib to pemetrexed-cisplatin in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): clinical results of a single-center trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:7528–7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boutin C, Rey F, Viallat JR. Prevention of malignant seeding after invasive diagnostic procedures in patients with pleural mesothelioma. A randomized trial of local radiotherapy. Chest. 1995;108:754–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bydder S, Phillips M, Joseph DJ, et al. A randomised trial of single-dose radiotherapy to prevent procedure tract metastasis by malignant mesothelioma. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:9–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Rourke N, Garcia JC, Paul J, Lawless C, McMenemin R, Hill J. A randomised controlled trial of intervention site radiotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clive AO, Taylor H, Dobson L, et al. Prophylactic radiotherapy for the prevention of procedure-tract metastases after surgical and large-bore pleural procedures in malignant pleural mesothelioma (SMART): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1094–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gordon W Jr, Antman KH, Greenberger JS, Weichselbaum RR, Chaffey JT. Radiation therapy in the management of patients with mesothelioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacLeod N, Chalmers A, O’Rourke N, et al. Is radiotherapy useful for treating pain in mesothelioma?: A phase II trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rusch VW, Rosenzweig K, Venkatraman E, et al. A phase II trial of surgical resection and adjuvant high-dose hemithoracic radiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Donahoe L, Cho J, de Perrot M. Novel induction therapies for pleural mesothelioma. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;26:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stahel RA, Riesterer O, Xyrafas A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and extrapleural pneumonectomy of malignant pleural mesothelioma with or without hem-ithoracic radiotherapy (SAKK 17/04): a randomised, international, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1651–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weder W, Stahel RA, Baas P, et al. The MARS feasibility trial: conclusions not supported by data. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1093–1094 [author reply: 1094–1095]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rimner A, Simone CB 2nd, Zauderer MG, Cengel KA, Rusch VW. Hemithoracic radiotherapy for mesothelioma: lack of benefit or lack of statistical power? Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e43–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosenzweig KE, Zauderer MG, Laser B, et al. Pleural intensity-modulated radiotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83: 1278–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cho BC, Feld R, Leighl N, et al. A feasibility study evaluating Surgery for Mesothelioma After Radiation Therapy: the “SMART” approach for resectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rimner A, Zauderer MG, Gomez DR, et al. Phase II study of hemithoracic intensity-modulated pleural radiation therapy (IMPRINT) as part of lung-sparing multimodality therapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2761–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Perrot M, Feld R, Leighl NB, et al. Accelerated hemithoracic radiation followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Minatel E, Trovo M, Bearz A, et al. Radical radiation therapy after lung-sparing surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: survival, pattern of failure, and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buikhuisen WA, Burgers JA, Vincent AD, et al. Thalidomide versus active supportive care for maintenance in patients with malignant mesothelioma after first-line chemotherapy (NVALT 5): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14: 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kindler HL, Karrison TG, Gandara DR, et al. Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine/cisplatin plus bevacizumab or placebo in patients with malignant mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2509–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zalcman G, Mazieres J, Margery J, et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1405–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: malignant pleural mesothelioma, version 3.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buikhuisen WA, Scharpfenecker M, Griffioen AW, Korse CM, van Tinteren H, Baas P. A randomized phase II study adding axitinib to pemetrexed-cisplatin in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a singlecenter trial combining clinical and translational outcomes. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:758–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tsao AS, Moon J, Wistuba II, et al. Phase I trial of cediranib in combination with cisplatin and pemetrexed in chemonaive patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (SWOG S0905). J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1299–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cortes-Dericks L, Froment L, Boesch R, Schmid RA, Karoubi G. Cisplatin-resistant cells in malignant pleural mesothelioma cell lines show ALDH(high)CD44(+) phenotype and sphere-forming capacity. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sulzmaier FJ, Jean C, Schlaepfer DD. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:598–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shapiro IM, Kolev VN, Vidal CM, et al. Merlin deficiency predicts FAK inhibitor sensitivity: a synthetic lethal relationship. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malanchi I, Peinado H, Kassen D, et al. Cutaneous cancer stem cell maintenance is dependent on beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2008;452:650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uematsu K, Seki N, Seto T, et al. Targeting the Wnt signaling pathway with dishevelled and cisplatin synergistically suppresses mesothelioma cell growth. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:4239–4242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramos A, Camargo FD. The Hippo signaling pathway and stem cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miyanaga A, Masuda M, Tsuta K, et al. Hippo pathway gene mutations in malignant mesothelioma: revealed by RNA and targeted exon sequencing. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meerang M, Berard K, Felley-Bosco E, et al. Antagonizing the hedgehog pathway with vismodegib impairs malignant pleural mesothelioma growth in vivo by affecting stroma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1095–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li H, Lui N, Cheng T, et al. Gli as a novel therapeutic target in malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robinson BW, Lake RA. Advances in malignant meso-thelioma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1591–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Tremelimumab for patients with chemotherapy-resistant advanced malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Calabro L, Morra A, Fonsatti E, et al. Efficacy and safety of an intensified schedule of tremelimumab for chemotherapy-resistant malignant mesothelioma: an open-label, singlearm, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maio M, Scherpereel A, Calabro L, et al. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1261–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alley EW, Lopez J, Santoro A, et al. Clinical safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): preliminary results from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Quispel-Janssen J, Zago G, Schouten R, et al. OA13.01 A phase II study of nivolumab in malignant pleural mesothelioma (NivoMes): with translational research (TR) biopies. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:S292–S293. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hassan R, Thomas A, Patel MR, et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) in patients with advanced unresectable mesothelioma from the JAVELIN solid tumor phase Ib trial: safety, clinical activity, and PD-L1 expression [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:85033. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Creaney J, Ma S, Sneddon SA, et al. Strong spontaneous tumor neoantigen responses induced by a natural human carcinogen. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e1011492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scherpereel A, Wallyn F, Albelda SM, Munck C. Novel therapies for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e161–e172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carbone M, Kanodia S, Chao A, et al. Consensus report of the 2015 Weinman International Conference on Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1246–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Quinlan TR, Marsh JP, Janssen YM, Borm PA, Mossman BT. Oxygen radicals and asbestos-mediated disease. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(suppl 10):107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choe N, Tanaka S, Xia W, et al. Pleural macrophage recruitment and activation in asbestos-induced pleural injury. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(suppl 5): 1257–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu A, Wu LJ, Santella RM, et al. Role of oxyradicals in mutagenicity and DNA damage induced by crocidolite asbestos in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59: 5922–5926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu A, Zhou H, Yu DZ, et al. Mechanisms of the genotoxicity of crocidolite asbestos in mammalian cells: implication from mutation patterns induced by reactive oxygen species. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110: 1003–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Carbone M, Yang H. Molecular pathways: targeting mechanisms of asbestos and erionite carcinogenesis in mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:598–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Acencio MM, Soares B, Marchi E, et al. Inflammatory cytokines contribute to asbestos-induced injury of mesothelial cells. Lung. 2015;193:831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang H, Rivera Z, Jube S, et al. Programmed necrosis induced by asbestos in human mesothelial cells causes high-mobility group box 1 protein release and resultant inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107: 12611–12616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang H, Bocchetta M, Kroczynska B, et al. TNF-alpha inhibits asbestos-induced cytotoxicity via a NF-kappaB-dependent pathway, a possible mechanism for asbestos-induced oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10397–10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cassel SL, Eisenbarth SC, Iyer SS, et al. The Nalp3 inflammasome is essential for the development of silicosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9035–9040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, et al. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jube S, Rivera ZS, Bianchi ME, et al. Cancer cell secretion of the DAMP protein HMGB1 supports progression in malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3290–3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Napolitano A, Antoine DJ, Pellegrini L, et al. HMGB1 and its hyperacetylated isoform are sensitive and specific serum biomarkers to detect asbestos exposure and to identify mesothelioma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3087–3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang H, Pellegrini L, Napolitano A, et al. Aspirin delays mesothelioma growth by inhibiting HMGB1-mediated tumor progression. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pietrofesa RA, Velalopoulou A, Arguiri E, et al. Flaxseed lignans enriched in secoisolariciresinol diglucoside prevent acute asbestos-induced peritoneal inflammation in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Catalano A, Graciotti L, Rinaldi L, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent celecoxib on malignant mesothelioma chemoprevention. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sterman DH, Alley E, Stevenson JP, et al. Pilot and feasibility trial evaluating immuno-gene therapy of malignant mesothelioma using intra-pleural delivery of adenovirus-ifnalpha combined with chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3791–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burt BM, Bader A, Winter D, Rodig SJ, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ. Expression of interleukin-4 receptor alpha in human pleural mesothelioma is associated with poor survival and promotion of tumor inflammation. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1568–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Abdul Rahim SN, Ho GY, Coward JI. The role of interleukin-6 in malignant mesothelioma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Seymour LW, Fisher KD. Oncolytic viruses: finally delivering. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:357–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vachani A, Moon E, Wakeam E, Albelda SM. Gene therapy for mesothelioma and lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2780–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sterman DH, Haas A, Moon E, et al. A trial of intrapleural adenoviral-mediated Interferon-a2b gene transfer for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1395–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sterman DH, Recio A, Carroll RG, et al. A phase I clinical trial of single-dose intrapleural IFN-beta gene transfer for malignant pleural mesothelioma and metastatic pleural effusions: high rate of antitumor immune responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4456–4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sterman DH, Recio A, Haas AR, et al. A phase I trial of repeated intrapleural adenoviral-mediated interferonbeta gene transfer for mesothelioma and metastatic pleural effusions. Mol Ther. 2010;18:852–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sterman DH, Recio A, Vachani A, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma receiving high-dose adenovirus herpes simplex thymidine kinase/ganciclovir suicide gene therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7444–7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hassan R, Thomas A, Alewine C, Le DT, Jaffee EM, Pastan I. Mesothelin immunotherapy for cancer: ready for prime time? J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:4171–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cornelissen R, Hegmans JP, Maat AP, et al. Extended tumor control after dendritic cell vaccination with low-dose cyclophosphamide as adjuvant treatment in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tan A, Porcher R, Crequit P, Ravaud P, Dechartres A. differences in treatment effect size between overall survival and progression-free survival in immunotherapy trials: a meta-epidemiologic study of trials with results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1686–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nabavi N, Bennewith KL, Churg A, Wang Y, Collins CC, Mutti L. Switching off malignant mesothelioma: exploiting the hypoxic microenvironment. Genes Cancer. 2016;7:340–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Paolicchi E, Gemignani F, Krstic-Demonacos M, Dedhar S, Mutti L, Landi S. Targeting hypoxic response for cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7, 13464 FRCSC 13478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wolchok JD, Rollin L, Larkin J. Nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377: 2503–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]