Abstract

Optimism and neuroticism have strong public health significance; however, their developmental precursors have rarely been identified. This study examined adolescents’ self-competence and their parents’ parenting practices as developmental origins of optimism and neuroticism in a moderated mediation model. Data were collected when European American adolescents (N = 290, 47% girls) were 14, 18, and 23 years old. Multiple-group path analyses with the nested data revealed that 14-year psychological control and lax behavioral control of both parents predicted lower levels of 18-year adolescence self-competence, which in turn predicted decreased 23-year optimism and increased neuroticism. However, the positive effects of warmth on 18-year optimism were stronger in the context of high maternal and paternal authoritativeness, and the positive effects of warmth on adolescent self-competence was attenuated by maternal authoritarianism. This study identified nuanced effects of parenting on adolescents’ competence and personality, which point to important intervention targets to promote positive youth development.

Keywords: parenting, self-perceptions, optimism, neuroticism, personality

Introduction

Despite the public health significance of optimism and neuroticism, little is known about their developmental origins (Carver & Scheier, 2014). Optimism and neuroticism are closely related positive and negative personality traits (Sharpe, Martin, & Roth, 2011). Optimism refers to positive expectancies regarding future outcomes (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) and has been linked to lower incidence of depression and favorable physiological pathways to health outcomes, such as lower cortisol responses under stress (Jobin, Wrosch, & Scheier, 2014). Neuroticism refers to relatively stable tendencies to respond with negative emotions and perceptions of uncontrollability to threat, frustration, or loss (Barlow, Ellard, Sauer-Zavala, Bullis, & Carl, 2014). Neuroticism has been robustly associated with adverse health outcomes, such as mood and eating disorders, schizophrenia (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2005), and Alzheimer’s disease (Johansson et al., 2014).

Although heritable to some degree (e.g., 25%-40%), optimism (Plomin et al., 1992) and neuroticism (Kendler, Aggen, Jacobson, & Deale, 2003) have a significant amount of variance attributable to environmental effects. Theories on personality development state that mostly biologically based individual differences in reactivity and regulation of emotions and behavior in early childhood become personality traits with development (Shiner & Caspi, 2003). Parenting has been recognized to play a significant role in this process (Van den Akker, Deković, Asscher, & Prinzie, 2014). Parental warmth (e.g., acceptance, expression of affection, positive evaluation), behavioral control (e.g., rule enforcement, regulation, monitoring), and psychological control (e.g., intrusiveness, control through guilt) are three important dimensions of parenting (Barber, Stolz, Olsen, Collins, & Burchinal, 2005). Generally, parental warmth and behavioral control are related to higher levels of psychosocial functioning (e.g., competence, self-regulation, academic achievement), and in contrast psychological control is associated with deficits in psychosocial development (Barber et al., 2005).

In terms of the links of these parenting practices to the two personality traits in this study, neuroticism has been positively associated with retrospective recall of controlling parenting (Reti et al., 2002) and negatively correlated with parental warmth (Ayoub et al., 2018). Optimism has been positively associated with retrospectively reported parental warmth (Hjelle, Busch & Warren, 1996) and support (Thomson, Schonert-Reichl, & Oberle, 2015). Because retrospective studies are subject to recall bias and cross-sectional studies cannot provide evidence for predictive relations, there is a pressing need for longitudinal studies that test prospective links of parenting practices to later personality development. There is also a need to separately examine behavioral control and psychological control in their relations to adolescent outcomes.

Parenting may not directly influence offspring personality traits; instead, consistent, bottom-up effects of parenting may first influence temporary states of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that take on a significant causal and mediational role to eventually change personality (Roberts, 2009). This study tested the hypothesis that adolescents’ self-perceptions of competence may mediate the effects of parenting on personality traits in young adulthood. Adolescence is a period of fluctuation in self-understanding, which renders self-perceptions particularly malleable and meaningful (Kokkinos & Hatzinikolaou, 2011). According to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), competence, autonomy, and relatedness are fundamental innate psychological needs essential for psychological growth, integrity, and well-being. Satisfaction and frustration of the need for competence has been causally related to positive and negative affect, respectively (Neubauer, Lerche, & Voss, 2017) and could potentially underlie the development of optimism and neuroticism.

Parental warmth and adequate behavioral control have been found to promote adolescent competence and autonomy (e.g., Van Petegem et al., 2017), whereas psychological control undermines these basic psychological needs, leading to harsh self-scrutiny and intense feelings of unworthiness (Bleys, Soenens, Claes, Vliegen, & Luyten, 2018). However, little research links perceptions of self-competence (the proposed mediator) to personality traits (the outcomes of interest). Therefore, studies of closely related concepts (self-worth and self-esteem) were drawn to develop the hypotheses for this study. Previous studies have shown that self-esteem or self-worth relates positively to optimism in adolescence and emerging adulthood (e.g., Thomson et al., 2015), but correlates negatively with neuroticism (e.g., Weidmann, Ledermann, Robins, Gomez, & Grob, 2018). On this account, self-competence was expected to be associated with more optimism and less neuroticism.

Given that parenting practices are expressed in the emotional climate created by parents’ general parenting style—the constellation of attitudes that are communicated to the child—the moderating role of parenting style on the effects of specific parenting practices was additionally examined, as suggested by Darling and Steinberg (1993). Baumrind’s (1971) seminal work identified three common styles of parenting, which correspond to three distinct prototypes of parental authority or control: authoritativeness, authoritarianism, and permissiveness. Authoritativeness is characterized by making more maturity demands, communicating more reciprocally, and acting more nurturant than authoritarian and permissive parenting styles, and is theorized to enhance the effectiveness of parenting practices by increasing children’s openness to parental attempts to socialize them. Authoritarianism, characterized by expecting strict obedience and relying on punitive disciplines, may attenuate the effectiveness of parenting practices by increasing children’s resistance to parental advice (Darling & Steinberg, 1993).

Few studies have independently measured both parenting practices and styles to examine their interactions. One early study by Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, and Darling (1992) found that the effectiveness of parents’ involvement in facilitating adolescent academic achievement is greater among authoritative than nonauthoritative families. Similarly, when parents endorsed a child-centered parenting style, parental involvement and monitoring more strongly predicted children’s academic performance (Spera, 2006). Moreover, adolescents experience less autonomy need frustration as a result of parental regulation if the family climate is more autonomy-supportive in general (Van Petegem et al., 2017). Based on the available evidence and theory, authoritativeness and authoritarianism were expected to enhance or attenuate the effects of parental warmth and behavior control, respectively. Given the paucity of research on permissiveness, no specific hypotheses for its moderation effects were set.

Another understudied area is the relative importance of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting to adolescent development. There are overall differences in the quantity and quality of maternal and paternal parenting (Doucet, 2013). In adolescence, mothers are more emotionally available to their offspring, and mother-adolescent dyads spend more time together than father-adolescent dyads (Larson & Sheeber, 2007). Mothers are more likely than fathers to parent adolescents in an authoritative manner, whereas higher proportions of fathers are classified as authoritarian (Simons & Conger, 2007). In spite of the differences in mothers’ and fathers’ parenting, fathers receive much less consideration in parenting research than do mothers (Pleck, 2012) and even less research has examined both mothers and fathers using the same measures in one study. Following are two examples of exceptions. Bean, Bush, McKenry, and Wilson (2003) found that fathers’, but not mothers’, behavioral control was significantly related to more adolescent self-esteem and both mothers’ and fathers’ psychological control significantly predicted less adolescent self-esteem. Ibrahim, Somers, Luecken, Fabricius, and Cookston (2017) found that more frequent father engagement in shared activities with adolescents, but not mother engagement, predicted lower cortisol response in emerging adults. Moving the field forward, it is crucial to examine both mothers and fathers simultaneously and statistically test similarities or differences in links of their parenting to adolescent functioning in an integrative analysis.

Current Study

This study examined adolescent self-competence and their parents’ practices as malleable individual and familial factors that contribute to the development of young adult optimism and neuroticism. Adolescent self-perception of competence was considered a potential mediator, and parenting styles as potential moderators, in the effects of parenting practices on young adult personality traits. It was hypothesized that more parental warmth and behavioral control would promote adolescent self-competence by fulfilling adolescents’ basic needs for competence and autonomy and psychological control would undermine adolescents’ self-competence by undermining these needs. In turn, adolescents’ self-competence was hypothesized to predict more optimism and less neuroticism in young adults because a positive view of self may facilitate the general tendency to be optimistic about the future and less emotionally negative. Moreover, under higher levels of authoritativeness and lower levels of authoritarianism in the family environment, the effects of parental warmth and behavioral control were expected to be more positive. Given the lack of pertinent research, the moderating role of permissive parenting styles was exploratory. Adolescent age and gender (Jeronimus, Ormel, Aleman, Penninx, & Riese, 2013), parent age, and family SES (Sangawi, Adams, & Reissland, 2016) were included as covariates because they are common demographic variables considered relevant for parenting, self-competence, optimism, or neuroticism.

Methods

Participants

Participants were European American adolescents and their parents in an east coast metropolitan area, recruited through newspaper advertisements and mass mailings. The first wave of data was collected when adolescents were 14 years old (N = 221 Mage = 13.85, SD = 0.27), the second wave was 4 years later when they were 18 years old (N = 190, Mage = 18.22, SD = 0.36), and the third was another 5 years later when they were 23 years old (N = 226, Mage = 23.56, SD = 0.59). The final sample had a total of 290 families (47% girls) who provided data for at least one wave. At 14 years, parents reported on their education levels and occupations, based on which family socioeconomic status (SES) was calculated (Hollingshead, 1975; M = 54.33, SD = 10.01). About 85% of them resided with both biological parents who were married and 6% with mothers who were married and lived with a partner other than the child’s father. Less than 2% of them resided with parents who were not married but the mothers lived with the child’s father or a partner other than the child’s father. About 8% of them lived with one parent because parents were separated (2%) or divorced (6%).

Procedures

Ethical approval for the study [88-CH-0032] was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Paper and pencil measures were used for the 14-year data collection and internet-based surveys for the 18-year and 23-year data collection. Informed consent was appropriately obtained before data collection at each wave.

Measures

Parenting practices.

At 14 years, adolescents completed the Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (Margolies & Wintraub, 1977) adapted from Schaefer’s (1965) original measure to assess their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices separately. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale: 0 (not at all true), 1 (sometimes true), and 2 (very true).

Warmth.

Warmth was computed as the mean of 24 items in the acceptance vs. rejection domain which consisted of positive parenting characterized by acceptance, expression of affection, positive evaluation, etc., and reverse coded negative parenting (e.g., ignoring, neglect, and rejection). Sample items included “Seems to see my good points more than my faults” and “Gives me a lot of care and attention.” Reliability (Cronbach’s α) for warmth was α = .95 for mothers and α = .94 for fathers.

Psychological control.

Psychological control was computed as the mean of 16 items in the psychological autonomy vs. control domain which was defined as covert, psychological methods controlling the child’s activities and behaviors that would not permit the child to develop as an individual apart from the parent. Sample items included “Feels hurt if I don’t follow her advice” and “Will talk to me again and again about anything bad I do.” Reliability for psychological control was α = .90 for mothers and α = .87 for fathers.

Lax behavioral control.

Lax behavioral control was computed as the mean of 16 items in the firm vs. lax behavioral control domain which was defined as the degree to which the parent does not make rules and regulations, set limits to the child’s activities, or enforce these rules and limits. Sample items included “Lets me get away without doing work I am supposed to do” and “Lets me off easy when I do something wrong.” Reliability for lax behavioral control was α = .79 for mothers and α = .83 for fathers.

Parenting styles.

At 14 years, parents self-reported their parenting styles using the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ; Buri, 1991). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Authoritativeness.

Authoritative parenting style was characterized as providing clear and firm direction for their children, but with disciplinary clarity moderated by reason, flexibility, and verbal give-and-take. An example item is “I take my child’s opinions into consideration when making decisions, but I would not decide to do something simply because my child wanted it.” Reliability for authoritativeness was α = .67 for mothers and α = .70 for fathers.

Authoritarianism.

Authoritarian parenting style was defined as highly directive with children, valuing unquestioning obedience in the exercise of authority over children, being detached, discouraging verbal give-and-take, and favoring punitive measures to parent children. An example item is “Whenever I tell my child to do something, I expect him/her to do it immediately without asking any questions.” Reliability for authoritarianism was α = .81 for mothers and α = .84 for fathers.

Permissiveness.

Permissive parenting style was defined as making fewer demands on children, allowing them to regulate their own activities as much as possible, and using a minimum of punishment with children. An example item is “I don’t view myself as responsible for directing and guiding my child’s behavior while s/he was growing up.” Reliability for permissiveness was α = .68 for mothers and α = .67 for fathers.

Self-competence.

Self-competence referred to adolescents’ own perceptions or judgment for how competent they are in different domains (e.g., academic, social). At 14 and 18 years, adolescents completed the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988) to assess their self-perceptions of competence using a structured alternative format. For example, “Some teenagers feel that they are just as smart as others their age, BUT other teenagers aren’t so sure and wonder if they are as smart.” After deciding between the two alternatives, adolescents rated the statement on a 4-point scale: 1 = really true for me (negative statement), 2 = sort of true for me (negative statement), 3 = sort of true for me (positive statement), and 4 = really true for me (positive statement). Twenty items (e.g., pretty intelligent, popular with others, make really close friends, do very well at sports) were included to capture adolescent self-competence in academic, social, and physical domains (Arbeit et al., 2014). Total scores were computed by averaging the 20 items (αs = .90 and .88 at 14 and 18 years, respectively).

Optimism.

At 18 and 23 years, adolescents/ young adults completed the Life Orientation Test-Revised (Scheier et al., 1994) which measures generalized expectancies for positive versus negative outcomes. Six items were rated on a 5-point scale (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = neutral, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree). The mean scores of the three reverse-coded, negatively worded items (e.g., “I hardly ever expect things to go my way”) and the three positively worded items (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”) were used to represent optimism (αs = .84 and .85 at 18 and 23 years, respectively).

Emotionality/ Neuroticism.

At 14 years, adolescents completed the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised (Ellis & Rothbart, 1999) to measure emotionality, which is considered an equivalent for the personality trait of neuroticism (Muris & Meesters, 2009). Emotionality included 13 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = almost always untrue, 2 = usually untrue, 3 = sometimes true, sometimes untrue, 4 = usually true, and 5 = almost always true). Sample items include “I worry about getting into trouble” and “I get very upset if I want to do something and my parents won’t let me.” The mean of the 13 items was computed to represent emotionality (α = .73). At 23 years, young adults completed the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999). Neuroticism included 8 items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 2 = disagree a little, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree a little, and 5 = agree strongly). Sample items include “Worries a lot” and “Is emotionally stable, not easily upset (reverse-coded).” The mean of the 8 items was computed to represent neuroticism (α = .85).

Data Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted on all available data using full information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data, which can provide unbiased parameter estimates even in the context of longitudinal studies with high levels of missing data (Enders, 2001). The data were missing completely at random (MCAR) as inferred by Little’s (1988) MCAR test, χ2 = 621.10, p = .121. Robust maximum likelihood estimation was used in path analyses to account for potential multivariate non-normality. The CLUSTER option in conjunction with the TYPE = COMPLEX option in Mplus were used to account for nonindependence of observations due to cluster sampling (mothers and fathers from the same families). All path models were evaluated using the following criteria for good model fit: non-significant χ2, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) greater than .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than .06, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) less than .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

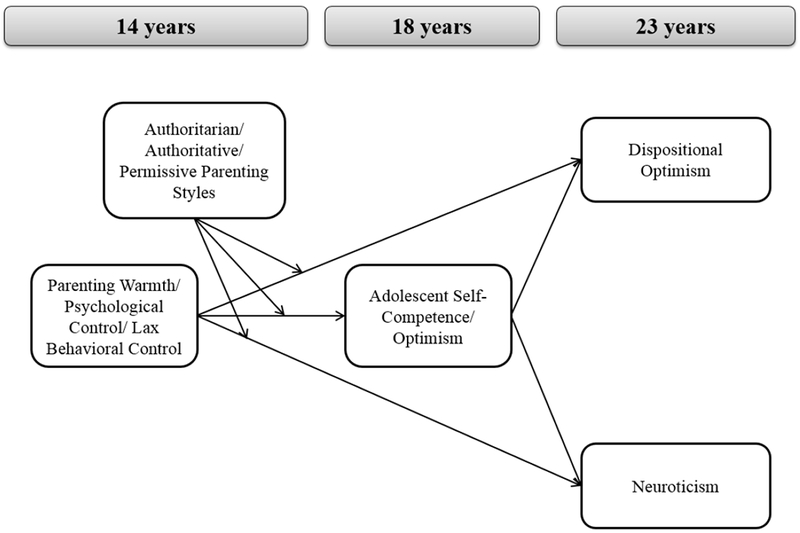

The unconstrained path models for both mothers and fathers combined were first estimated (see Figure 1 for the conceptual model), with 14-year parenting practices as predictors, 14-year parenting styles as moderators, 18-year adolescent self-competence and optimism as mediators, and 23-year optimism and neuroticism as outcomes. Prior levels of the major mediator and outcome variables were controlled (i.e., autoregressive paths from 14-year self-competence to 18-year self-competence, 14-year emotionality to 23-year neuroticism, and 18-year optimism to 23-year optimism). Multi-group analyses were then conducted to test the equivalence of path coefficients across mothers and fathers using Wald chi-square difference (the MODEL TEST command in Mplus).

Figure 1.

The conceptual model. All prior levels of the primary mediator (competence) and outcome variables were controlled.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations among main variables are presented in Table 1. Maternal and paternal warmth at 14 years was both positively correlated with 18-year adolescent self-competence and optimism. In contrast, maternal and paternal psychological control and lax behavioral control were both negatively correlated with 18-year optimism and self-competence, respectively, whereas maternal psychological control was also negatively correlated with 18-year adolescent self-competence. Furthermore, 14-year self-competence was positively correlated with 18-year self-competence and optimism as well as positively correlated with optimism and negatively correlated with neuroticism at 23 years. In contrast, 14-year emotionality was negatively correlated with 18-year self-competence and optimism, and positively correlated with neuroticism and negatively correlated with optimism at 23 years. Finally, adolescent self-competence and optimism at 18 years were positively correlated with optimism and negatively correlated with neuroticism at 23 years.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Warmth 14 yrs | — | −.27** | −.01 | −.11 | .08 | −.02 | .02 | .30** | .24** | .21** | .16 | −.07 | 1.44 (0.38) |

| 2. Psychological control 14 yrs | −.30** | — | −.02 | .25** | −.09 | −.09 | .25** | −.33** | −.26** | −.21* | −.08 | −.01 | 0.62 (0.41) |

| 3. Lax behavioral control 14 yrs | .14 | −.21** | — | −.05 | −.13 | .20** | .06 | −.10 | −.25** | −.02 | .002 | .12 | 0.61 (0.29) |

| 4. Authoritarianism 14 yrs | −.16* | .14 | −.13 | — | −.07 | −.23** | .04 | .09 | −.13 | −.05 | −.10 | .06 | 2.68 (0.58) |

| 5. Authoritativeness 14 yrs | .11 | .003 | .09 | −.15 | — | −.12 | −.04 | .11 | .12 | .10 | .03 | −.01 | 4.02 (0.34) |

| 6. Permissiveness 14 yrs | .004 | .08 | −.07 | −.19* | −.08 | — | .12 | −.12 | .02 | .01 | −.01 | .05 | 2.08 (0.40) |

| 7. Emotionality 14 yrs | −.14 | .22** | −.08 | −.04 | .13 | −.07 | — | −30** | −.24** | −.26** | −.24** | .25** | 2.95 (0.53) |

| 8. Self-competence 14 yrs | .34** | −.27** | −.03 | .11 | −.03 | −.02 | −.30** | — | .54** | .30** | .16* | −.19* | 3.13 (0.50) |

| 9. Self-competence 18 yrs | .17* | −.15 | −.25** | .03 | −.03 | −.09 | −.24** | .54** | — | .43** | .36** | −.34** | 3.13 (0.48) |

| 10. Optimism 18 yrs | .22** | −.20* | .01 | .05 | −.02 | −.04 | −.26** | .30** | .43** | — | .52** | −.41** | 2.50 (0.70) |

| 11. Optimism 23 yrs | .01 | −.12 | .08 | −.01 | −.13 | .09 | −.24** | .16* | .36** | .52** | — | −.54** | 2.57 (0.74) |

| 12. Neuroticism 23 yrs | .09 | −.07 | .10 | −.09 | .04 | −.05 | .25** | −.19* | −.34** | −.41** | −.54** | — | 2.83 (0.81) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.35 (0.40) | 0.57 (0.38) | 0.62 (0.33) | 2.84 (0.62) | 3.98 (0.36) | 2.16 (0.43) | 2.95 (0.53) | 3.13 (0.50) | 3.13 (0.48) | 2.50 (0.70) | 2.57 (0.74) | 2.83 (0.81) |

Note: Mother data are above the diagonal, and father data are below the diagonal. Variables 4-6 were rated by parents and the rest of the variables were rated by adolescents.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Multiple-Group Path Analyses

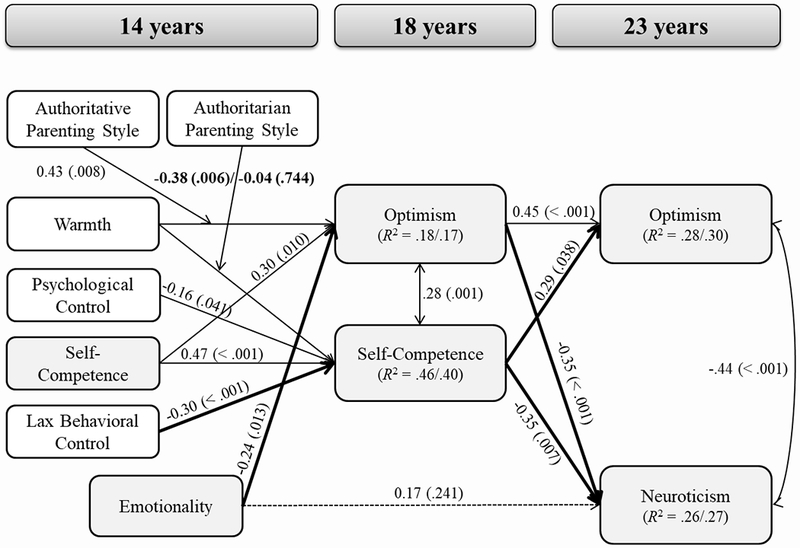

The unconstrained model achieved good model fit where non-significant interactions and covariates were trimmed from the model, χ2 (63, N = 580) = 71.54, p = .216, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03. For multiple-group comparisons, unstandardized paths coefficients across parents were gradually tested and constrained to be equal if they did not show significant differences based on Wald chi-square difference tests. The final constrained model (Figure 2) achieved good model fit, χ2 (87, N = 580) = 61.57, p = .982, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .03. The path coefficients were largely similar across mothers and fathers except the paths related to the interaction of Warmth × Authoritarianism, Δχ2(1, N = 580) = 4.68, p = .031, and the path from psychological control to 23-year optimism (but this path was not significant for either parent), Δχ2(1, N = 580) = 4.54, p = .033. Only significant results are reported below. Standardized path coefficients are available upon request.

Figure 2.

The final model based on multi-group analysis. Only unstandardized autoregressive paths and other significant structural paths (p values) are presented for clarity. The bolded numbers differed across mothers and fathers (mothers/ fathers). Bolded lines represent paths that are part of indirect effects.

Direct and moderated paths to 18-year mediators.

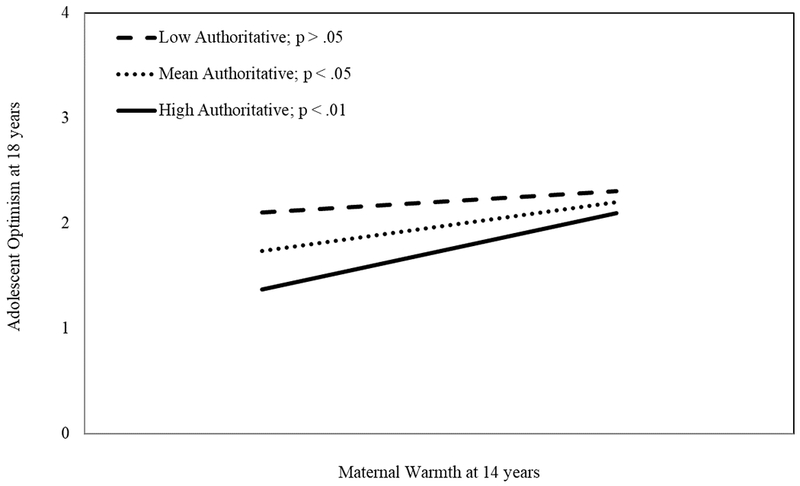

As shown in Figure 2, for both parents, less 14-year psychological control and lax behavioral control predicted greater 18-year adolescent self-competence after controlling for stability in self-competence. Moreover, parental warmth interacted with authoritativeness to predict adolescent optimism. At mean (mothers: b = 0.26, SE = 0.11, p = .013, 95% CI [0.06, 0.47]; fathers: b = 0.24, SE = 0.10, p = .019, 95% CI [0.04, 0.45]) and high levels (mothers: b = 0.41, SE = 0.12, p = .001, 95% CI [0.17, 0.65]; fathers: b = 0.40, SE = 0.12, p = .001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.64]) of parental authoritativeness, 14-year parental warmth predicted 18-year optimism (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Maternal warmth interacted with authoritativeness to predict adolescent optimism.

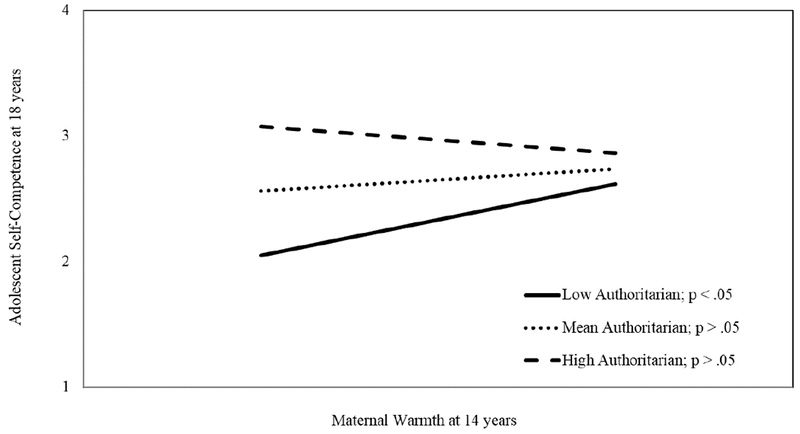

However, for mothers only, parental warmth interacted with authoritarianism to predict adolescent self-competence. Specifically, 14-year maternal warmth predicted 18-year adolescent self-competence only when maternal authoritarianism was low (b = 0.32, SE = 0.13, p = .014, 95% CI [0.07, 0.58]) (see Figure 4). Permissiveness did not moderate the effects of any parenting practices. Finally, 14-year emotionality predicted less 18-year optimism (95% CI [−0.43, −0.05]). For covariates, males had higher levels of self-competence at 18 years (b = 0.19, SE = 0.06, p = .001). Older adolescents had higher levels of optimism at 18 years (b = 0.35, SE = 0.16, p = .031), whereas older parents tended to have adolescents with lower self-competence at 18 years (b = −0.01, SE = 0.004, p = .023).

Figure 4.

Maternal warmth interacted with authoritarianism to predict adolescent self-competence.

Direct and indirect paths to 23-year outcomes.

As shown in Figure 2, higher 18-year adolescent self-competence predicted more optimism and less neuroticism at 23 years, and optimism at 18 years predicted less neuroticism at 23 years. For covariates, there was a significant gender difference in emerging adults’ neuroticism (b = −0.33, SE = 0.09, p < .001), with females more neurotic than males. In addition, results revealed several significant mediations (i.e., indirect effects). Specifically, 14-year parental lax behavioral control negatively predicted 18-year adolescent self-competence which in turn predicted 23-year optimism/neuroticism (14-year lax behavioural control → 18-year self-competence → 23-year optimism/neuroticism: b = −0.09, SE = 0.04, p = .045, 95% CI [−0.17, −0.002]/ b = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p = .025, 95% CI [0.01, 0.20]). Moreover, 14-year emotionality showed an indirect effect on 23-year neuroticism through 18-year optimism (b = 0.08, SE = 0.04, p = .048, 95% CI [0.001, 0.17]).

Discussion

Much research has associated personality traits of optimism and neuroticism with significant public health consequences, including physical and mental health outcomes, but their developmental origins are relatively less known (Lahey, 2009). This study focused on individual (i.e., adolescent self-competence) and familial (i.e., parenting) origins of optimism and neuroticism and examined relevant mediation and moderation mechanisms in a 9-year longitudinal design. Results showed that perceived parental warmth when adolescents were 14 years promoted more adolescent self-competence at 18 years but only in the context of lower maternal authoritarianism in the family climate. Parental warmth also promoted more adolescent optimism at 18 years but only in the context of higher maternal and paternal authoritativeness in the family’s emotional environment. Moreover, for both parents, higher behavioral control was found conducive to adolescent self-competence, whereas psychological control was detrimental to adolescent self-competence. Finally, adolescent self-competence at 18 years significantly mediated the effects of maternal and paternal lax behavioral control at 14 years on optimism and neuroticism at 23 years.

In early adolescence, higher levels of psychological control and lower levels of behavioral control from both parents were unique predictors of diminished adolescent self-competence, regardless of the overall parenting style. These findings are consistent with the view of detrimental influences of parents’ psychological control and lack of behavioral control on adolescents’ development (e.g., Bean et al., 2003). Psychologically controlling parenting may interfere with adolescents’ need for independence and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and impede their development of confidence and trust in their own uniqueness and ideas (Bleys et al., 2018). Moreover, psychological control (e.g., talk to adolescents again and again for anything bad they do) is likely to give rise to negative self-definitions such as self-criticism rather than competence (Kopala-Sibley & Zuroff, 2014). Without behavioral regulation and rule enforcement (e.g., communicating the limits of acceptable behavior), adolescents may risk becoming impulsive rather than behaviorally and emotionally self-regulated (Moilanen, Padilla-Walker, & Blaacker, 2018), leading to lower levels of academic, physical, and social competence.

Parental warmth contributed to higher adolescent optimism when authoritativeness in the family environment was relatively high. Together with previous studies (e.g., Van Petegem et al., 2017), this finding provides support that an authoritative parenting style enhances the effectiveness of specific parenting practices on child development. By creating a trustful and autonomy-supportive family dynamic, authoritative parents’ use of warmth is likely to foster a healthy positive expectancy in adolescents towards their future.

Conversely, within a hostile and controlling family environment created by an authoritarian parenting style, even potentially beneficial parenting practices can become ineffective. The effects of maternal warmth on adolescent self-competence were indeed attenuated by the general authoritarianism of mothers. Authoritarian mothers may focus more on adolescents’ failings than their achievements, which can create internalized stress and problems (Rose, Roman, Mwaba, & Ismail, 2018) and undermine adolescents’ positive self-perceptions (Heaven & Ciarrochi, 2008). Moreover, because of harsh control, high expectations, and excessive criticism from authoritarian mothers, adolescents may consider maternal warmth as contingent on meeting those strict standards and thus develop a tendency to feel inferior rather than competent (Kopala-Sibley & Zuroff, 2014). Authoritarian parenting is more prevalent and normative in fathers (Simons & Conger, 2007); accordingly, mothers’ authoritarianism might be particularly harmful and elicit more resistance in adolescents that may in turn mitigate the beneficial effects of warmth (Russell et al., 1998).

Adolescent self-competence had robust effects on optimism and neuroticism and significantly mediated the effects of parents’ lax behavioral control on these personality traits. This finding may be explained by Scheier and Carver’s (1993) view that optimism is partly learned from prior experiences of successes and failures. Adolescents with higher self-competence were likely to have more success experiences, which in turn cultivated their optimistic character. The same rationale can explain the association between self-competence and neuroticism because success in goal achievement may reduce individuals’ feelings of uncontrollability of environment, a feature of neuroticism (Barlow et al., 2014). Moreover, a greater sense of competence is positively linked to life satisfaction (Hollifield & Conger, 2015) which likely decreases moodiness and negative perceptions of the world as a dangerous and threatening place. The negative effects of lax behavioral control on optimism and neuroticism highlight the importance of effectively enforcing rules and limits to personality development.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, adolescents’ reports of perceived parenting practices as well as their own self-competence and personality traits were used, which are susceptible to same-source biases. However, personality and self-competence by their nature are difficult to assess by methods other than self-report, and perceived parenting is sometimes as or more meaningful than actual parenting behavior (Barber, 1996). Moreover, parents reported their own parenting styles to capture a fuller picture of the parenting environment. Another possible limitation concerns the generalizability of the results. This sample comprised European American community families, which limited diversity but increased generalizability to a known population (Bornstein, Jager, & Putnick, 2013). Future studies on other cultural and ethnic groups can test whether similar findings or unique processes will be identified. Finally, not all constructs at all waves were measured and thus bidirectional relations between parenting and developmental outcomes could not be tested. However, the predictions of parenting practices on 18-year self-competence and 23-year optimism and neuroticism, the main focus of this study, could be properly examined because stability of these primary constructs was controlled.

This study has several implications for practice. The findings imply that home-based interventions which focus on ameliorating family risk can target reducing maladaptive parenting styles and practices to enhance adolescent self-competence and in turn foster the development of positive personality traits. During adolescence, parents still play an important role in adolescents’ social and academic life and in shaping how adolescents perceive and feel about themselves. Therefore, supporting parents in attending parenting interventions and educational programs is critical to decrease their negative parenting strategies such as the use of psychological control and lack of behavioural regulation, which ultimately have long-term implications of adolescents’ self and personality development. Moreover, creating a positive family environment is equally important to adopting a particular parenting strategy because it can maximize the effectiveness of particular parenting practices. Parenting programs targeting mothers’ authoritarianism may be especially helpful due to its more detrimental influence compared to fathers’ authoritarianism.

Conclusion

Despite the public health significance of optimism and neuroticism, few studies have examined the developmental origins of these personality traits. This study addressed this gap by focusing on individual (i.e., adolescent self-competence) and familial (i.e., parenting) antecedents of optimism and neuroticism using a 9-year longitudinal design. For both parents, more psychological control and lax behavioral control in early adolescence contributed to less adolescent self-competence 4 years later which in turn predicted more optimism and less neuroticism 9 years later when adolescents entered young adulthood. In contrast, parental warmth prospectively predicted more adolescent optimism 4 years later when the family environment was relatively high on authoritativeness. The only meaningful difference across parents was the role of authoritarian parenting style in moderating the effect of warmth on adolescent self-competence, with maternal authoritarianism more detrimental for adolescent development. The findings indicate that parental control and regulation matter and warmth alone may not be sufficient in promoting adolescents’ positive feelings about themselves. Overall, this study highlights adolescence as an important developmental period for building the perceptions of self-competence or the core sense of self which has long-term consequences for personality development and are still shaped by mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices and styles.

References

- Arbeit MR, Johnson SK, Champine RB, Greenman KN, Lerner JV, & Lerner RM (2014). Profiles of problematic behaviors across adolescence: Covariations with indicators of positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 971–990. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0092-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub M, Briley DA, Grotzinger A, Patterson MW, Engelhardt LE, Tackett JL, … & Tucker-Drob EM. (2018). Genetic and Environmental Associations Between Child Personality and Parenting. Social Psychological and Personality Science. doi: 10.1177/1948550618784890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA, Collins WA, & Burchinal M (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, i–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Ellard KK, Sauer-Zavala S, Bullis JR, & Carl JR (2014). The origins of neuroticism. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 481–496. doi: 10.1177/1745691614544528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4(1, Pt. 2), 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bean RA, Bush KR, McKenry PC, & Wilson SM (2003). The impact of parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control on the academic achievement and self-esteem of African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18, 523–541. doi: 10.1177/0743558403255070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleys D, Soenens B, Claes S, Vliegen N, & Luyten P (2018). Parental psychological control, adolescent self-criticism, and adolescent depressive symptoms: A latent change modeling approach in Belgian adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1833–1853. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Jager J, & Putnick DL (2013). Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Developmental Review, 33, 357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & Scheier MF (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, & Steinberg L (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet A (2013). Gender roles and fathering In Tamis-LeMonda C and Cabrera N (Eds.). 2nd ed,. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. (pp. 297–319) New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L, & Rothbart MK (1999). Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire—Revised. Unpublished manuscript, University of Oregon–Eugene, Department of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2001). The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods, 6, 352–370. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S (1988). Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heaven P, & Ciarrochi J (2008). Parental styles, gender and the development of hope and self-esteem. European Journal of Personality, 22, 707–724. doi: 10.1002/per.699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelle LA, Busch EA, & Warren JE (1996). Explanatory style, dispositional optimism, and reported parental behavior. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 157, 489–499. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1996.9914881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield CR, & Conger KJ (2015). The role of siblings and psychological needs in predicting life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 3, 143–153. doi: 10.1177/2167696814561544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). The Four Factor Index of Social Status Unpublished manuscript, Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MH, Somers JA, Luecken LJ, Fabricius WV, & Cookston JT (2017). Father–adolescent engagement in shared activities: Effects on cortisol stress response in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 485–494. doi: 10.1037/fam0000259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeronimus BF, Ormel J, Aleman A, Penninx BW, & Riese H (2013). Negative and positive life events are associated with small but lasting change in neuroticism. Psychological Medicine, 43, 2403–2415. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobin J, Wrosch C, & Scheier MF (2014). Associations between dispositional optimism and diurnal cortisol in a community sample: when stress is perceived as higher than normal. Health Psychology, 33, 382–391. doi: 10.1037/a0032736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson L, Guo X, Duberstein PR, Hällström T, Waern M, Östling S, & Skoog I (2014). Midlife personality and risk of Alzheimer disease and distress: A 38-year follow-up. Neurology, 83, 1538–1544. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, & Srivastava S (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives In Pervin LA & John OP (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Jacobson KC, & Neale MC (2003). Does the level of family dysfunction moderate the impact of genetic factors on the personality trait of neuroticism?. Psychological Medicine, 33, 817–825. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703007840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos CM, & Hatzinikolaou S (2011). Individual and contextual parameters associated with adolescents’ domain specific self-perceptions. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopala-Sibley DC, & Zuroff DC (2014). The developmental origins of personality factors from the self-definitional and relatedness domains: A review of theory and research. Review of General Psychology, 18, 137–155. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64, 241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, and Sheeber L (2007). The daily emotional experience of adolescents In Allen N and Sheeber L (Eds.), Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, & Schutte NS (2005). The relationship between the five-factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolies PJ, & Weintraub S (1977). The revised 56 item CRPBI as a research instrument: Reliability and factor structure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 472–476. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen KL, Padilla-Walker LM, & Blaacker DR (2018). Dimensions of Short-Term and Long-Term Self-Regulation in Adolescence: Associations with Maternal and Paternal Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship Quality. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1409–1426. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0825-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, & Meesters C (2009). Reactive and regulative temperament in youths: Psychometric evaluation of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 7–19. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9089-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer AB, Lerche V, & Voss A (2017). Interindividual differences in the intraindividual association of competence and well being: Combining experimental and intensive longitudinal designs. Journal of Personality, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH (2012). Integrating father involvement in parenting research. Parenting, 12, 243–253. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.683365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Scheier MF, Bergeman CS, Pedersen NL, Nesselroade JR, & McClearn GE (1992). Optimism, pessimism and mental health: A twin/adoption analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 921–930. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90009-E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reti IM, Samuels JF, Eaton WW, Bienvenu Iii OJ, Costa PT Jr, & Nestadt G (2002). Influences of parenting on normal personality traits. Psychiatry Research, 111, 55–64. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00128-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW (2009). Back to the future: Personality and assessment and personality development. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Roman N, Mwaba K, & Ismail K (2018). The relationship between parenting and internalizing behaviours of children: a systematic review. Early Child Development and Care, 188, 1468–1486. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1269762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Aloa V, Feder T, Glover A, Miller H, & Palmer G (1998). Sex-based differences in parenting styles in a sample with preschool children. Australian Journal of Psychology, 50, 89–99. doi: 10.1080/00049539808257539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangawi H, Adams J, & Reissland N (2018). The impact of parenting styles on children developmental outcome: The role of academic self-concept as a mediator. International Journal of Psychology, 53, 379–387. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424. doi: 10.2307/1126465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, & Carver CS (1993). On the power of positive thinking: The benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 26–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182190 [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, & Bridges MW (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe JP, Martin NR, & Roth KA (2011). Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 946–951. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, & Caspi A (2003). Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, & Conger RD (2007). Linking mother–father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 212–241. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06294593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spera C (2006). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental goals, practices, and styles in relation to their motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 456–490. doi: 10.1177/0272431606291940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, & Darling N (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63, 1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson KC, Schonert-Reichl KA, & Oberle E (2015). Optimism in early adolescence: Relations to individual characteristics and ecological assets in families, schools, and neighborhoods. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 889–913. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9539-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Akker AL, Deković M, Asscher J, & Prinzie P (2014). Mean-level personality development across childhood and adolescence: A temporary defiance of the maturity principle and bidirectional associations with parenting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 736–750. doi: 10.1037/a0037248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem S, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Brenning K, Mabbe E, … & Zimmermann G. (2017). Does General Parenting Context Modify Adolescents’ Appraisals and Coping with a Situation of Parental Regulation? The Case of Autonomy-Supportive Parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 2623–2639. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0758-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weidmann R, Ledermann T, Robins RW, Gomez V, & Grob A (2018). The reciprocal link between the Big Five traits and self-esteem: Longitudinal associations within and between parents and their offspring. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 166–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]