Abstract

Systematic americyl-hydration cations were investigated theoretically to understand the electronic structures and bonding in [(AmO2)(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6). We obtained the binding energy using density functional theory methods with scalar relativistic and spin–orbit coupling effects. The geometric structures of these species have been investigated in aqueous solution via an implicit solvation model. Computational results reveal that the complexes of five equatorial water molecules coordinated to americyl ions are the most stable due to the enhanced ionic interactions between the AmO22+/1+ cation and multiple oxygen atoms as electron donors. As expected, Am–Owater bonds in such series are electrostatic in nature and contain a generally decreasing covalent character when hydration number increases.

Introduction

In the past several decades, a rapid increased resurgence of nuclear power in many countries for the goals of ensuring sustainable energy supplies has raised a possible hazard to the environment due to the problems of the radioactive waste and has increased the handling and reprocessing challenge of spent nuclear fuel and high-level nuclear waste.1−5 Especially, the long-term radioactivity of nuclear waste repositories is one of the main issues at stake and is in part determined by the presence of minor actinides, namely, americium (Am) and curium (Cm), with the half-life t1/2 = 7370 year for 243Am and t1/2 = 340 000 year for 248Cm.6,7 During the actinide waste storage, transportation, and separation, water is unavoidable. Therefore, the characterization and identification of the behavior of actinide ions in solution is of particular practical importance in addition to the fundamental actinide chemistry, such as the dynamics between the coordinated water molecules and the bulk solvent and the coordination flexibility of actinyl ions.8 So, the solution chemistry of actinide complexes has been considerably explored in experiment and theory; especially, the hydration of actinide ions has been widely investigated.9−12 However, such studies have mostly focused on early actinide ions due to their relatively substantial quantities and extensive applications. The uranyl UO22+ ion, for example, has received a large amount of interest because of its importance for environmental chemistry of radioactive elements and its role as a benchmark system for heavier actinides.13 Experimentally, direct structural information on the coordination of uranyl in aqueous solution has been mainly obtained by extended X-ray absorption fine structure or X-ray absorption near-edge structure measurements.9,14,15 Theoretically, the structural investigation has been performed via various ab initio studies of uranyl and related molecules, with a number of explicit water molecules or with a polarizable continuum model to mimic the environment over the past years, such as [UO2(CO3)3]4–, [Th(H2O)n]4+, [U(H2O)n]3+, UO2Fn(H2O)5–n2–n, and [UO2(H2O)n]n+.10,16−21 With the rapid development of quantum chemical methods, the less known transuranium elements have been increasingly studied, i.e., [NpO2(CO3)3]4–, [NpO2(CO3)m(H2O)n], [Cm(H3O)n]3+, [UO2(H2O)n]n+, [NpO2(H2O)n]n+, and [PuO2(H2O)n]n+.7,12,13,22−28 There appears to be no theoretical report about americyl (AmO22+/1+) in aqueous solution but one study on the water exchange mechanism in AmO2(H2O)52+ 15 years ago.29 In addition, the understanding of the coordination chemistry of americyl ions in solution can present the essentials to detect, characterize, and differentiate this metal ion from transition metals or lanthanide metals through the coordination characteristic. Hence, we will focus on speciation of the americyl ions (AmO22+ and AmO21+) in this paper, bridging the gap between the wide-established early actinides and the more complicate later actinides. However, an accurate description of solvent effects of the actinide complexes is inherently difficult due to their complicated electronic properties and the challengeable aqueous environment to theoretical chemists. There are two typical quantum chemistry strategies used to incorporate the solvent effects on the geometry and energy of the actinide complexes in aqueous solution. One is molecular dynamics simulations approach with a discrete model, where a number of explicit solvent molecules are included and treated at the same level of theory as that used for the solute.30 Although this supermolecule requires a substantial computational expense, the understanding improvement of the structural and chemical behavior of actinyl in solution is inconsequential because this method employs empirical potentials affecting the accuracy significantly, especially for those transplutoniums having few experimental data available. Another approach is the polarizable continuum model, where the solvent is described by a dielectric polarizable continuum.31 This model has shown a good agreement with experimental results on the geometric and electronic structures in actinyl–water complexes,15 where uranyl, neptunyl, and plutonyl coordinated to five water ligands in the equatorial plane have been computationally confirmed.13,32

In this contribution, we report a systematic investigation on the chemistry of hydrated americyl ions in the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) complexes using a suite of computational modeling and various bonding analysis methods. We address the equilibrium structures of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+, as well as the hydration number of americyl ions and the bonding nature of americium ions and oxygen atoms. In addition to the knowledge for the periodicity in bonding properties, the influence of aqueous solvation of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) will provide a scientific comprehension to the actinide solution chemistry.

Results and Discussion

The static structures of hydrated complexes of AmO22+/1+ with one to eight water ligands have been regularly investigated via geometry optimizations in gas phase and in aqueous phase at the B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ level with or without the conductor-like screening solvation model (COSMO) method. First, concerning the water hydrogens lying either in the planes or perpendicular to the planes defined by the OylAmOyl, two possible gas-phase symmetric arrangements of water molecules for [AmO2(H2O)1]2+/1+ and [AmO2(H2O)2]2+/1+ have been optimized without symmetry constraints. As shown in Figure S1, the one with hydrogens perpendicular to the plane has one imaginary vibrational frequency (428i cm–1) showing the rotation of water ligand, indicating its instability compared with the one with hydrogens lying in the plane. Besides, the starting structure of [AmO2(H2O)7]2+/1+ has been assumed as a first-shell coordination number of seven when seven water molecules are bonded to AmO22+/1+, in which the seven equatorial water ligands lie rigorously in the equatorial plane. After optimization within density functional theory (DFT), seven water molecules have been arranged into two coordination shells; there are five water molecules in the first shell with a relatively shorter Am–Ow distance of <2.5 Å and two water molecules in the second shell at a longer distance of >4.4 Å. Therefore, the hydration number of AmO22+/1+ in the first shell is predicted to be less than seven. In addition, the optimized structural parameters and calculated binding energies of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) in the gas phase and aqueous solution on the basis of different levels of theory are listed in Tables S1–S4. As clearly shown in the Tables S3 and S4, the energy destabilization by roughly 32.0–128.2 kcal/mol for [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ (n = 1–6) complexes is due to the conductor-like polarized continuum model; a similar trend is also observed for [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ (n = 1–6) complexes. Upon inclusion of the surrounding effects, the binding energy decreases drastically to 62.4 kcal/mol for equatorial [AmO2(H2O)6]2+ and to −0.5 kcal/mol for equatorial [AmO2(H2O)6]1+ at scalar relativistic (SR)-B3LYP level of theory, indicating the instability of this structure. In terms of geometries of equatorial [AmO2(H2O)6]2+/1+, the six-water complexes with all six coordinated Ow atoms in the equivalent position are subject to the first-order Jahn–Teller instability and are only saddle points having imaginary frequencies. The Ci symmetry structure of [AmO2(H2O)6]2+ in which all six ligands are in the first coordination shell, shown in Figure S2, is stable with or without aqueous solution. The distance from the americium center to the water molecules located above and below the equatorial plane in a symmetric manner is longer (0.09 Å) than that for [AmO2(H2O)5]2+ and is significantly shorter (0.13 Å) than that reported for NpO2(H2O)62+ having a similar structure largely owing to the actinide contraction of ion radii. A somewhat different structure of [AmO2(H2O)6]1+ is obtained, whereas the sixth water is excluded to the second hydration shell owing to the weak electrostatic interaction between AmO21+ and water oxygen. Thus, the hydration number of AmO22+/1+ is five in resulting minimum-energy structures of both [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) complexes.

Since the solvation effect is significant on the geometry of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ and also plays a typical role in practical application, we only report the geometry optimization results under the effect of aqueous solvation in text. Table 1 presents the binding energies obtained at SR-B3LYP and CCSD(T) levels of theory for the following reaction of [AmO2]2+/1+ + nH2O → [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) in solution. As shown in Table 1, each of these [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ (n = 1–6) complexes is significantly more stable than the corresponding [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ (n = 1–6). At the SR-B3LYP level of theory, the americyl–water binding energies steadily increase from 34.0 kcal/mol for [AmO2(H2O)1]2+ (19.1 kcal/mol for [AmO2(H2O)1]1+) to 119.0 kcal/mol for [AmO2(H2O)5]2+ (68.2 kcal/mol for [AmO2(H2O)5]1+), whereas at the spin–orbit (SO) level of theory, the binding energies show the same trend by increasing from 45.4 kcal/mol at n = 1 to 135.0 kcal/mol at n = 5 in the series of AmO2(H2O)n2+. Overall, the substantial stabilizations of [AmO2(H2O)5]2+/1+ relative to the isolated americyl and free water molecules favors the formation of a maximum of five water ligands in the equatorial plane in the first hydration shell. This five-coordination structure has been commonly observed in other actinyls in water environment in the available experimental studies and is in good accord with the published theoretical studies using quantum mechanical method or molecular dynamics approach.

Table 1. Binding Energy (kcal/mol) for the Reaction of AmO22+/1+ + nH2O → [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) in Solution at Different Levels of Theory with COSMO.

| [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ |

[AmO2(H2O)n]1+ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | CCSD(T) | B3LYP | CCSD(T) | |||

| n | ΔESR | ΔESO | ΔE | ΔESR | ΔESO | ΔE |

| 1 | –34.0 | –45.4 | –64.7 | –19.1 | –31.0 | –35.0 |

| 2 | –64.6 | –77.1 | –120.9 | –36.4 | –49.7 | –66.0 |

| 3 | –88.5 | –104.4 | –173.5 | –52.5 | –68.4 | –95.7 |

| 4 | –110.2 | –126.2 | –213.1 | –63.7 | –93.6 | –117.6 |

| 5 | –119.0 | –135.0 | –68.2 | –84.4 | ||

| 6 | –113.7 | –128.0 | –65.1 | –71.9 | ||

Geometric Structure of the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5)

Two different density functionals (Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) and B3LYP) were first employed for the geometrical optimization, which gave similar results, so only the results obtained at B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ level of theory are presented in the text and those obtained at the PBE/TZ2P level are detailed in the Supporting Information (Tables S1 and S2). As noted in the last section, the inclusion of solution therefore and the use of a solvation model are important in modeling the coordination structures of actinyl. So the calculated ground-state geometries for [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5) in aqueous solution using the COSMO solvation model are listed in Table 2 and shown in Figure 1. In terms of geometry, [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ and [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ have similar geometric structures; these are the water molecules coordinating to AmO22+/1+ on the equatorial plane of americyl with an increasing hydration number from n = 1–5, as expected, with the same hydration number as that of of uranyl, neputonyl, and plutonyl in aqueous solution. The calculated Am–Oyl distances in the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes elongate from 1.669 Å in pure americyl ion to 1.681 Å in [AmO2(H2O)1]2+ and increase all through to 1.711 Å in [AmO2(H2O)5]2+, whereas the Am–Oyl bonds in the [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ complexes appear to follow the same trend, consistent with the decrease in the bond order, attributed to the weakening of both ionic and covalent bonding interactions of Am–Oyl bond from n = 1–5. In all [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5) complexes, the americyl is coordinated by water O atoms (Ow) with bond Am–Ow distances longer than 2.2 Å, which implies weak bonding interactions. In addition, all Am–Ow bond lengths in the complexes are beyond the range of Am–O covalent single-bond lengths estimated by the sum of the self-consistent covalent radii derived by Pyykkö.33 Expectedly, the Am–Ow bond lengths in the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes are shorter than the corresponding bond lengths in the [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ complexes, owing to the stronger electrostatic interaction in dication complexes. The lengthening of the Am–Ow bond distances in the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes from 2.260 Å at n = 1 to 2.460 Å at n = 5 implies the reduction of bond strength and the weakening of bonding interaction of each Am–Ow bond along with increasing hydration numbers. Although each of the Am–Ow bonds is not particularly strong in comparison to Am–Oyl multiple bond, the overall bonding interaction is substantial, as indicated by significant binding energies (Table 1) and by the extreme redshift in the americyl asymmetric stretch frequency (Table 3).

Table 2. Selected Optimized Geometrical Structures (Bond Length, Å, Angle, °) and Formation Energy (Ef, kcal/mol) for the Reaction of fϕ1fδ2 [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ and fϕ2fδ2 [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ (n = 0–5) at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ Levels of Theorya.

| [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ |

[AmO2(H2O)n]1+ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | state (symm.) | Am–Oyl | Am–Ow | ∠OylAmOyl | ∠OwAmOw | state (symm.) | Am–Oyl | Am–Ow | ∠OylAmOyl | ∠OwAmOw |

| 0 | 4Φ (D∞h) | 1.669 | 5∑g(D∞h) | 1.735 | ||||||

| 1 | 4B1 (C2v) | 1.681 | 2.260 | 179.5 | 5A1 (C2v) | 1.747 | 2.398 | 179.8 | ||

| 2 | 4B1 (C2v) | 1.692 | 2.286 | 179.0 | 96.8 | 5A1 (C2v) | 1.758 | 2.420 | 179.8 | 103.1 |

| 3 | 4A′ (Cs) | 1.699 | 2.331, 2.326 | 179.8 | 127.8, 113. 2, 118. 7 | 5A′ (Cs) | 1.768 | 2.448, 2.447, 2.445 | 179.9 | 122.2, 120.4, 117.4 |

| 4 | 4B2u (D2h) | 1.707 | 2.371 | 180.0 | 92.7, 87.3 | 5Ag (C4h) | 1.778 | 2.496 | 180.0 | 90.0 |

| 5 | 4A′ (Cs) | 1.710 | 2.420, 2.462, 2.470 | 179.4 | 66.3, 74.5, 78.4 | 5A (C1) | 1.781 | 2.562, 2.548, 2.586, 2.568, 2.589 | 179.4 | 72.0 |

All optimizations are fully relaxed without constraints.

Figure 1.

Optimized geometry and binding energy (kcal/mol, in parentheses) of AmO2(H2O)n2+/1+ (n = 1–5) at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ levels of theory.

Table 3. Calculated Vibrational Frequencies of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5) at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ Levels of Theory with COSMO.

| Am–Oyl |

Am–Ow |

Am–Oyl |

Am–Ow |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v3 | v1 | Δq(v3) | v3 | v1 | v3 | v1 | Δq(v3) | v3 | v1 | |

| 0 | 1053.7 | 925.1 | 925.6 | 828.0 | ||||||

| 1 | 1027.6 | 904.7 | 26.1 | 420.4 | 904.4 | 810.7 | 21.2 | 316.8 | ||

| 2 | 1009.1 | 891.6 | 18.6 | 385.7 | 412.4 | 882.9 | 792.7 | 21.4 | 309.8 | 307.6 |

| 3 | 994.8 | 880.7 | 14.2 | 360.8 | 367.5 | 866.0 | 777.7 | 16.9 | 260.1 | 290.0 |

| 4 | 980.9 | 868.4 | 13.9 | 312.0 | 351.7 | 849.5 | 764.7 | 16.4 | 246.9 | 275.0 |

| 5 | 970.4 | 855.9 | 10.5 | 273.9 | 314.2 | 839.1 | 754.1 | 10.4 | 239.6 | 252.6 |

For the monoaqua, the ground electronic states of [AmO2(H2O)]2+/1+ have been confirmed as 4B1 and 5A1 via a comparison among different multiplicities. Upon the coordination of Ow in [AmO2(H2O)]2+/1+, the linear OylAmOyl is broken into bent ∠OylAmOyl angles of 179.5 and 179.8°, respectively. The water molecule coordinates to americyl on the equatorial plane with the two hydrogen atoms lying symmetrically on both sides of the plane. The shortest Am–Ow bond distance of 2.26 Å among the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ series is within the range of single covalent bond radii of Am–O (2.29 Å), mainly because of the strongest bonding. These distances are consistent with the bonding analysis detailed in the next section. The singly filled highest occupied molecular orbitals of [AmO2(H2O)]2+/1+ have roughly 98% Am 5fϕ and 90% Am 5fδ character, indicating that the Am 5f orbital is largely unperturbed by the coordination of the ligands. Thus, [AmO2]2+/1+ retain their electron configuration at Am ions in those [AmO2(H2O)]2+/1+ complexes, namely, fϕ1fδ2 and fϕ2fδ2, respectively.

For the dual aqua, one additional water molecule locates in the equatorial plane with a bent ∠OwAmOw angle of 96.8° in [AmO2(H2O)2]2+ and 103.1° in [AmO2(H2O)2]1+, inducing a weakening of both axial and equatorial bond strength, as reflected by the increase of 0.10 and 0.02 Å in the Am–Oyl and Am–Ow bond distances compared to those in [AmO2(H2O)1]2+/1+. The optimized Am–Ow bond distance is 2.286 Å in [AmO2(H2O)2]2+ and 2.420 Å in [AmO2(H2O)2]1+; the slightly longer distance in the monocation complex is consistent with the small binding energy. Noticeably, the favorable bent versus linear geometries of the ∠OwAmOw reveals the covalent characteristic of Am–Ow bond, which pulls the two Ow atoms much closer, leading to an Ow–Ow distance of 3.420 Å in [AmO2(H2O)2]2+ and 3.790 Å in [AmO2(H2O)2]1+. The electrons singly occupy on Am 5f6d atomic orbital (AO)-based molecular orbitals (MOs) in [AmO2(H2O)]2+/1+, which provides extensive Am 5f → Ow 2p back-bonding, involving donation from an Am 5fϕ orbital into in-plane Ow 2p orbitals, thus leading to a three-center interaction. The effectiveness of the Ow 2p → Am 5f6d dative bonding and Am 5f → Ow 2p back donation is less obvious in [AmO2(H2O)2]1+ due to a longer Am–Ow distance, denoted by a relatively large ∠OwAmOw angle of 103.1°. In particular, the variety in the average effective charges of the Ow ligand, listed in Table 4, is an evidence to this statement. The average Hirshfeld charges on the Ow of [AmO2(H2O)2]2+ and [AmO2(H2O)2]+ are −0.16 |e| and −0.20 |e|, respectively, slightly greater relative to those of −0.15 |e| and −0.20 |e| in [AmO2(H2O)1]2+/1+, as the consequence of the Am-to-Ow back donation.

Table 4. Average Hirshfeld, Voronoi Deformation Density (VDD) Charges, and Average Mulliken, Multipole Derived Charges (MDC_q) Spin Density on the B3LYP with COSMO-Optimized Structures of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5) from the PBE/TZ2P Calculations.

| |

[AmO2(H2O)n]2+ |

[AmO2(H2O)n]1+ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| charge | spin density | charge | spin density | ||||||

| n | Hirshfeld | VDD | Mulliken | MDC_q | Hirshfeld | VDD | Mulliken | MDC_q | |

| 0 | Oyl | –0.03 | 0.22 | –0.22 | –0.23 | –0.26 | –0.08 | –0.23 | –0.28 |

| Am | 2.06 | 1.55 | 3.44 | 3.46 | 1.52 | 1.17 | 4.46 | 4.57 | |

| 1 | Oyl | –0.09 | 0.09 | –0.21 | –0.22 | –0.30 | –0.18 | –0.23 | –0.29 |

| Ow | –0.15 | –0.15 | –0.01 | –0.09 | –0.20 | –0.15 | –0.01 | –0.09 | |

| Am | 1.77 | 1.27 | 3.43 | 3.48 | 1.32 | 0.96 | 4.46 | 4.61 | |

| 2 | Oyl | –0.13 | –0.02 | –0.20 | –0.22 | –0.33 | –0.28 | –0.22 | –0.30 |

| Ow | –0.16 | –0.16 | –0.01 | 0.01 | –0.20 | –0.16 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Am | 1.53 | 1.04 | 3.42 | 3.46 | 1.14 | 0.79 | 4.46 | 4.61 | |

| 3 | Oyl | –0.17 | –0.13 | –0.19 | –0.15 | –0.35 | –0.35 | –0.22 | –0.06 |

| Ow | –0.18 | –0.16 | –0.01 | 0.01 | –0.20 | –0.15 | 0.00 | 0.10 | |

| Am | 1.31 | 0.81 | 3.41 | 3.20 | 0.98 | 0.59 | 4.45 | 3.69 | |

| 4 | Oyl | –0.19 | –0.19 | –0.19 | –0.09 | –0.37 | –0.40 | –0.21 | 0.00 |

| Ow | –0.19 | –0.18 | 0.00 | 0.07 | –0.21 | –0.18 | 0.00 | 0.07 | |

| Am | 1.18 | 0.75 | 3.39 | 2.94 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 4.41 | 3.52 | |

| 5 | Oyl | –0.21 | –0.20 | –0.19 | –0.01 | –0.38 | –0.41 | –0.23 | 0.00 |

| Ow | –0.20 | –0.20 | 0.00 | 0.04 | –0.21 | –0.19 | 0.00 | 0.06 | |

| Am | 1.11 | 0.74 | 3.39 | 2.68 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 4.45 | 3.51 | |

For the triaqua, one more water molecule added with the formation of [AmO2(H2O)3]2+/1+ further weakens the Am–O bonds, as identified by the longer Am–Oyl and Am–Ow bond distances than those in [AmO2(H2O)2]2+/1+. In gas phase, three coordinated water molecules are equivalent with the ∠OwAmOw angle of 120.0°, giving a C3v symmetry structure. However, when concerning the presence of aqua solvent, this symmetry has been broken into Cs symmetry with the ∠OwAmOw angles of 127.8, 113.2, and 118.7° in [AmO2(H2O)3]2+ and 117.4, 120.4, and 122.2° in [AmO2(H2O)3]1+ complexes, largely ascribed to the differences responding to the polarization of the hydration upon solvent inclusion. In essence, the solvent polarity is more effective in those complexes with larger polarity. As listed in Table 2, the deviation from the high-symmetry structure of the ∠OwAmOw angle in [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ is more obvious than that in [AmO2(H2O)n]1+, suggesting that the structure of dication ions could result in engaging in stronger hydrogen bonding with the bulk solvent than that of monocation ions. For example, the ∠OwAmOw angles are 92.7 and 87.3° in [AmO2(H2O)4]2+ and 66.3, 74.5, and 78.4° in [AmO2(H2O)5]2+, whereas 90.0° in [AmO2(H2O)4]1+ and 72.0° in [AmO2(H2O)5]1+ are retained, thus confirming that the solvent shows greater differential stabilization in [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes.

From our above discussion of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ structures, we would expect the additional water molecules to extend the Am–Oyl and Am–Ow bond lengths and to decrease the overall degree of dative bonding, consistent with the lower relative binding energy for the [AmO2(H2O)q]2+/1+ compared to that of the [AmO2(H2O)p]2+/1+ (5 ≥ q = p + 1). The maximum of five hydration number in the first coordination shell is in good agreement with the equilibrium structure having five water coordination of actinyl (UO22+, NpO22+, and PuO22+) in aqueous solution. In the equilibrium structure of [AmO2(H2O)5]2+/1+, four water molecules bonded to the center americyl are perpendicular to the equatorial plane and the fifth coordinated water molecule arranges within the equatorial plane where the dihedral angle between the equatorial water ligands and the equatorial plane is 0° (Figure 1). The bond length of the fifth Am–Ow bond is 2.420 Å in [AmO2(H2O)5]2+ and 2.548 Å in [AmO2(H2O)5]1+, the shortest one among five Am–Ow bond distances, thus leading to a slight bent of ∠OylAmOyl angles of 179.4°.

Electronic Structure and Chemical Bonding of the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5)

To provide further insights into the interactions between americyl ion and the water ligands of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+, several bonding analyses were performed, including the bond order analyses, population partitioning schemes, energy decomposition approach, Kohn–Sham orbital interaction, and electron localization function (ELF) method.

The bond order analyses by three methods give a similar trend that is consistent with the previous detailed bond length trend. Taking the Mayer Am–O bond index as an example, the calculated Mayer bond orders (Table 5) of Am–Oyl and Am–Ow for the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes lie in two ranges, at averaged 1.9 and averaged 0.2, respectively, whereas those for [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ complexes lie in two ranges, at averaged 1.85 and averaged 0.2, respectively. This result indicates relatively weak Am–Ow bonding interactions compared with the Am–Oyl bonding in [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ complexes, which is resulted from not only the ionic bonding nature but also the somewhat longer bond distance induced by weaker orbital interaction. The calculated Am–Oyl bond order in [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ decreases gradually from 2.05 at n = 1 to 1.88 at n = 5, whereas the Am–Ow bond order decreases from 0.39 at n = 1 further to 0.19 at n = 5, suggesting there is a general decrease in Am–O bond strength with an increasing hydration number. In addition to the bond order, the effective atomic charges on Am and Ow ions can imply the variation of the ionicity of the Am–Ow bond. Several charge analyses were carried out on the B3LYP stationary structure in solution via COSMO. Although the absolute values are different on the basis of different methods used, the trend is the same. As listed in Table 4, the averaged Hirshfeld charges reveal that Am carries a considerable positive charge and the Ow ligands carry substantial negative charges in these [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes, which is in good agreement with the bond order analyses, indicating an ionic An–Ow bonding interaction. Generally, the Am ions become less charged and both Oyl and Ow atoms become more charged along with the increase of the hydration number, i.e., the calculated Hirshfeld charge of Am decreases from +2.06 |e| in pure AmO22+ to +1.77 |e| in monoaqua and further to +1.11 |e| in penta-aqua, accompanied by an increased charge of each Oyl atom from −0.03 |e| to −0.21 |e|; this is due to the charge rearrangement of americyl unit upon inclusion of explicit water in the first shell and implicit water by COSMO, which is in good agreement with the study of [UO2(H2O)m(OH)n]2–n.34 The averaged Hirshfeld charges of Ow atoms becoming greater from −0.15 |e| to −0.21 |e| suggests overall increasing of electron back donation into Ow ligand, thus leading to the Am–Oyl bond weakening with an increasing hydration number. In addition, the decreased electron density localized on americyl unit listed in Table 4 indicates that the charge transfer is from americyl unit to water ligands, owing to the Am-to-Ow back donation. Furthermore, the formal Am oxidation state of +VI and +V is not apparently affected by the hydration number in these [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes via population analyses.

Table 5. Average Mayer Bond Orders of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–5) from the PBE/TZ2P Calculations.

| [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ |

[AmO2(H2O)n]1+ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Am–Oyl | Am–Ow | Am–Oyl | Am–Ow | |||||

| n | vacuum | COSMO | vacuum | COSMO | vacuum | COSMO | vacuum | COSMO |

| 0 | 2.12 | 2.12 | 1.99 | 2.00 | ||||

| 1 | 2.06 | 2.05 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 1.94 | 1.94 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| 2 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 1.90 | 1.90 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| 3 | 1.96 | 1.95 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| 4 | 1.91 | 1.90 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 5 | 1.89 | 1.88 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 1.80 | 1.81 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

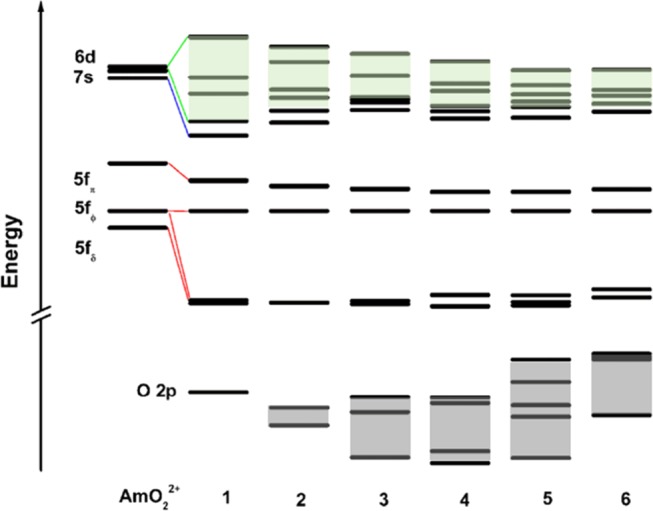

To better understand the orbital interactions, Figure 2 shows the Kohn–Sham MO energy levels of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ at SR-PBE/TZ2P level. In the linear AmO22+ moiety due to Am–Oyl bonding, the Am 5f and 6d orbitals transform as 5fu and 6dg species, respectively. Upon dative coordination with the water oxygen atoms in the equatorial plane, the Am–Ow orbital interactions cause to 6dg level further destabilization. While both dδg and fδu–fϕu orbitals lie around the equatorial plane, the Am–Ow orbital interactions mainly affect the 6d orbitals, indicating that the coordinated water molecules only slightly interact with the “nonbonding” contracted 5f orbitals. This bonding module is in good agreement with the well-known bonding principle proposed for actinides by Bursten, the FEUDAL (“f’s are essentially unaffected, d’s accommodate ligands”).35,36 Overall, the Am–Ow bonding in [AmO2(H2O)1]2+ is strongest among these [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ complexes and becomes progressively weaker on increasing the hydration number, consistent with the indirect evidence from geometries, vibrational frequencies, and bond order. These conclusions are consistent with the bonding compositions of the natural localized MOs (NLMOs, Table S5), with analysis detailed below.

Figure 2.

Kohn–Sham molecular orbital analyses of the AmO2(H2O)n2+ complexes based on SR-zero-order regular approximation (ZORA) B3LYP/TZ2P calculations.

In addition to these chemical bonding analyses based on wave functions and electron densities, the energy decomposition analysis (EDA) based on canonical molecular orbitals and the extended transition state (ETS) method combined with the natural orbitals for chemical valence (ETS–NOCV) theory were further applied to reveal the intrinsic bonding mechanism in terms of the major contributions to the orbital interactions. The computed EDA results for AmO22+/1+ + nH2O → [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (Tables 6 and 7) show that electrostatic ionic interaction (ΔEelstat) accounts for almost 2/3 contribution to the total bonding energy (ΔEint), playing more significant roles than those of orbital interaction (ΔEorbital). The decreasing trend of both electrostatic interactions and covalent orbital interactions are the same as those of bonding energies, that is, generally increasing with the hydration number from monoaqua toward penta-aqua. The change of ΔEelstat or ΔEorbital is not significantly in tetra-aqua and penta-aqua, reflecting that the variation of both ionic and covalent interactions with the increasing number of the water molecules becomes smaller in aqueous solution. In contrast to the monotonous increase of ΔEelstat or ΔEorbital, the Pauli repulsion increases remarkably from 65.3 kcal/mol in monoaqua to 159.6 kcal/mol in tetra-aqua, then declines to 151.4 kcal/mol in penta-aqua, indicating the formation of the stable penta-aqua. The ETS–NOCV analyses additionally reveal the intrinsic bonding mechanism in terms of the contributions to the orbital interactions. The results of some representative contributions for [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ are listed in Tables 6 and 7, and their deformation densities describing the density inflow are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. The highest covalent character of each Am–Ow bond can be observed in monoaqua among these [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes in terms of the orbital interaction, which is decomposed into two types (π-type and σ-type) with several terms, taking orb1–orb3 as examples, providing energetic stabilizations of ΔEorb1 = −29.2 kcal/mol, ΔEorb2 = −14.4 kcal/mol, and ΔEorb3 = −6.4 kcal/mol, respectively. These natural orbitals denote the typical π- or σ-type orbital interactions achieved via two fragments of americyl and water molecules, relating to the Am 5f6d-hybridized atomic orbitals and π-MOs of water molecules contributed by Ow 2p atomic orbitals. Note that consistent with the reduced trend of bonding energy of each Am–Ow bond across the series, the trend of the donation character is also decreased accompanied by a decrease of major orbital contributions and a slight lengthening of Am–Ow bonds. The composition of the stabilization energy of each Am–Ow bond in [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes is small, but the summarization is substantial and increases across the series. Therefore, the orbital interactions between the An 5f6d hybrid orbitals and π-MOs of Ow result in a significant covalent bonding character not only stabilizing [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes beyond electrostatic ionic interaction but also effectively supporting the weak bonding characteristics of 5f orbital, which is consistent with the ELF result shown in Figure 5 and with the NLMO analyses (listed in Table S5).

Table 6. ETS–NOCV Energy Decomposition Analyses between the Interacting Fragments of AmO22+ and H2O Unit and Their Corresponding Energy ΔEiorb (kcal/mol) from Open-Shell PBE/TZ2P Calculations.

| 1(4A) |

2(4A) |

3(4A) |

4(4A) |

5(4A) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmO22+ (4A) fϕ1fδ2 | AmO22+ (4A) fϕ1fδ2 | AmO22+ (4A) fϕ1fδ2 | AmO22+ (4A) fϕ1fδ2 | AmO22+ (4A) fϕ1fδ2 | ||||||

| frag. | H2O (1A)···8a2 | H2O (1A)···16a2 | H2O (1A)···24a2 | H2O (1A)···32a2 | H2O (1A)···40a2 | |||||

| ΔEint | –68.5 | –125.7 | –177.8 | –218.3 | –241.9 | |||||

| ΔEPauli | 65.3 | 114.6 | 143.9 | 159.6 | 151.4 | |||||

| ΔEelstat | –76.5 | –138.7 | –190.0 | –223.7 | –229.6 | |||||

| ΔEorb | –57.4 | –101.6 | –131.7 | –154.2 | –163.7 | |||||

| α | β | α | β | α | β | α | β | α | β | |

| ΔE1 | –14.5 | –14.6 | –17.5 | –16.3 | –14.2 | –12.7 | –19.3 | –17.8 | –16.6 | –15.4 |

| ΔE2 | –7.8 | –6.6 | –10.5 | –11.6 | –13.8 | –12.0 | –10.5 | –10.4 | –14.2 | –14.6 |

| ΔE3 | –3.1 | –3.2 | –11.4 | –13.5 | –8.5 | –7.4 | –11.5 | –10.8 | ||

Table 7. ETS–NOCV Energy Decomposition Analyses between the Interacting Fragments of AmO21+ and H2O units and Their Corresponding Energy ΔEiorb (kcal/mol) from an Open-Shell PBE/TZ2P Calculation.

| 1(5A) |

2(5A) |

3(5A) |

4(5A) |

5(5A) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmO21+ (5A) fϕ2fδ2 | AmO21+ (5A) fϕ2fδ2 | AmO21+ (5A) fϕ2fδ2 | AmO21+ (5A) fϕ2fδ2 | AmO21+ (5A) fϕ2fδ2 | ||||||

| interacting fragments | H2O (1A)···8a2 | H2O (1A)···16a2 | H2O (1A)···24a2 | H2O (1A)···32a2 | H2O (1A)···40a2 | |||||

| ΔEint | –39.3 | –69.7 | –98.9 | –121.7 | –129.7 | |||||

| ΔEPauli | 38.5 | 70.6 | 92.7 | 103.2 | 100.4 | |||||

| ΔEelstat | –48.1 | –89.7 | –124.9 | –147.9 | –149.9 | |||||

| ΔEorb | –29.8 | –50.6 | –66.7 | –77.0 | –80.2 | |||||

| α | β | α | β | α | β | α | β | α | β | |

| ΔE1 | –7.3 | –6.6 | –8.3 | –7.1 | –6.9 | –6.7 | –9.9 | –8.7 | –7.7 | –6.9 |

| ΔE2 | –2.2 | –2.0 | –5.7 | –5.2 | –6.7 | –6.7 | –6.1 | –5.7 | –7.2 | –6.5 |

| ΔE3 | –0.5 | –0.5 | ||||||||

Figure 3.

Contours of representative deformation densities (isovalue = 0.001 au) between the interacting fragments of AmO22+ and H2O unit from ETS–NOCV analysis, describing the density inflow (blue) and outflow (white).

Figure 4.

Contours of representative deformation densities (isovalue = 0.001 au) between the interacting fragments of AmO2+ and H2O unit from ETS–NOCV analysis, describing the density inflow (blue) and outflow (white).

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional ELF contours (isovalue = 0.03 au) for the Ow–Am–Ow planes containing the Am–Ow interactions. The results are based on the SR-ZORA calculated densities.

Considering that the Am–Ow dative bond and back donation were observed from density deformation analyses, NLMO calculations were further explored to describe the extent of this bonding interaction. The localized σ- and π- MOs on Am–Ow are made up of Am 5f6d and O 2s2p hybrid orbitals, which are composed by roughly 95% O 2s2p lone-pair AO and ∼5% Am df hybrid orbitals in [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ and by ∼98% O 2s2p lone-pair AO and ∼2% Am df hybrid orbitals in [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ on the basis of the NLMO analyses. The enhanced stability of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ complexes across the series can only be explained as a result of the water coordinates inducing the increased electrostatic energy. Noticeably, the Am 6d participating in the dative oxygen bonding plays an important role over Am 5f due to both more extended radial distribution of the Am 6d orbitals and the better energy level matching between the An 6d and O 2p orbitals. The compositions of the NLMOs from Am valence atomic orbitals decline from around 3% of the σ orbitals and 7% of the π orbitals in [AmO2(H2O)1]2+ to 1% and 6% in [AmO2(H2O)5]2+.

Conclusions

Through relativistic quantum chemical calculations, the electronic and geometric structures of the [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) complexes have been systematically studied. Full five-coordination binding of water ligands in the first shell is preferred in the aqua solution for [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+. Extensive chemical bonding analyses of the charges, energy decomposition analysis, and natural orbitals, all agree in that the Am–Ow interaction is predominantly ionic in nature, with a small extent of covalent bonding contribution resulted from the An 5f6d-hybridized orbitals and relevant Ow 2p orbitals. The covalent orbital interaction between the equatorial Ow and Am ions raises several interesting features in the bonding of Am–Ow: (1) a bonding interaction between the Am AOs and the Ow 2p orbitals arranges the water ligand deviation from linear in [AmO2(H2O)2]2+/1+ into bent; (2) the reduced dative bonding affects the Am–Ow bond length and bond order across the series; (3) the small back-bonding donations of Am 5f → Ow 2p decrease the population of americium ions. As noted, the implicit solvation model is unable to provide the dynamics information of actinide ions in solution or the exchange of ion-influenced solvent molecules with the bulk, which is important to some extent in practical application. Further quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics molecular dynamics simulation with explicit solvent is necessary to study statistically the equilibrium between americyl and water in different coordination shells. We hope that this investigation represents only the beginning of long-term research relevant to the mission in spent fuel reprocessing of the transplutonium, in addition to enriching our knowledge of actinide coordination chemistry.

Methodology

The calculations on the open-shell americyl complexes were carried out with unrestricted Kohn–Sham wave functions. As known, the molecular orbital (MO) diagram of pure americyl is similar to that of uranyl: the combinations of the 2p orbitals of the two oxygen with the 6d orbitals of the americium atom form occupied bonding orbitals, whereas the combinations of the O 2p orbitals with the 5f manifold orbitals of the actinide atom result in nonbonding δu and ϕu orbitals and antibonding σu* and πu* orbitals; the corresponding bonding σu and πu orbitals are found to have rather small 5f contributions. In AmO22+ and AmO21+, the americium has the configurations 5f3 and 5f4, respectively, and these electrons are spread in the nonbonding 5fδu and 5fϕu orbitals. Following Hund’s rule, the ground electronic states of hexavalent and pentavalent Am ions have been found to be of a high-spin character, that is, fδ2fϕ1 and fδ2fϕ2 configurations and 4Δ and 5Σ electronic states for AmO22+ and AmO21+, respectively. The spin–orbit coupling (SOC) effects should be considered during the calculations of the electronic structures of americyl complexes in solution.37

The scalar relativistic DFT calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 and ADF 2017 softwares38−40 for the geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency analyses. First, for geometry optimizations by the Gaussian code, we used the scalar relativistic Stuttgart energy-consistent relativistic 32 valence electron pseudopotential and the associated ECP60MWB_SEG valence basis set41,42 for the americium atom. The split-valence triple-ζ basis sets with polarization functions (cc-pVTZ)43,44 were used for the oxygen and hydrogen atoms. The B3LYP hybrid density functional45,46 was used in these calculations. The solvent effects were approximated using the Gaussian 09 implementation of the conductor-like screening solvation model (COSMO) solvent model,47,48 where the solute is embedded in a shape-adapted cavity consisting of interlocking spheres centered on each solute atom or group. The combination of these pseudopotentials and basis sets with this functional (labeled as B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O, H/cc-pVTZ level) has been shown to give accurate predictions of the properties and reaction energies of actinide complexes.19,20 At the same B3LYP theory level, vibrational frequency calculations were further performed to ensure that all force constants should be positive and all frequencies should be real. Ultrafine integration grids and very tight optimization were applied. The spin–orbital symmetry restrictions were relaxed, performing spin-unrestricted UDFT calculations.

The coupled cluster with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples (CCSD(T)) method49−51 in MOLPRO 2012 program52 was used for single-point calculations on the optimized aqueous-phase B3LYP geometries to check whether the systems have multireference character and to acquire more accurate relative energies. The ECP60MWB pseudopotential with ECP60MWB_SEG basis set for Am and the cc-pVTZ basis for O and H were applied in the CCSD(T) calculations. However, limited by the computer resources, the nonsymmetry molecules of [AmO2(H2O)5]2+/1+ or [AmO2(H2O)6]2+/1+ cannot be handled by CCSD(T) due to the giant basis of those molecules.

Further electronic structure and chemical bonding analyses at the DF level were performed with the ADF 2017. The scalar relativistic (SR) effects were taken into account by the zero-order regular approximation (ZORA).53,54 The SOC effects were taken into account by SO-ZORA. The frozen-core approximation was applied to the atomic [1s2–5d10] shell of Am and the [1s2] shells of the O atoms. The B3LYP combined with slater basis sets of triple-ζ plus two polarization function (TZ2P) quality were applied.55 Single-point calculations were carried out on the B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O H/cc-pVTZ optimized aqueous-phase structures to determine the charge distribution and bond order. The bond order analyses based on the Mayer method,56 Gopinathan–Jug indices,57 and Nalewajski–Mrozek method58,59 were performed. The charge analyses based on the Mulliken method,60 Hirshfeld analysis,61 Voronoi deformation density (VDD),62 and multipole derived charges (MDC)63 were calculated as well. The energy decomposition analyses (EDA) based on canonical molecular orbitals and theoretical analyses via combined extended transition state (ETS) with the natural orbitals for chemical valence (NOCV) theory59,64−66 were carried out. The electron localization functions (ELF) were calculated to investigate the feature of the weak dative bonding. Weinhold’s natural bond orbital (NBO)67 and natural localized molecular orbital (NLMO)67−70 analyses were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G* level71 on optimized geometries from B3LYP calculations by using the NBO 5.0 program.72,73

In further geometry optimizations, the generalized gradient approximation with the PBE exchange–correlation functional74 was used in ADF 2017. Scalar (SR) and SO relativistic effects were accounted by applying the same stratagem as detailed in the above paragraph. The effects of water considered by COSMO were determined using single-point energy calculation on gas-phase structures. The atomic COSMO-default radii 210.0 pm was used.48

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research from the Science Challenge Project (No. TZ2018004) and the NSAF (U1530401), the Foundation of President of China Academy of Engineering Physics (No. YZJJSQ2017072), the Foundation for Development of Science and Technology of China Academy of Engineering Physics (No. 2015B0102020), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21701006, 21771167, and 11874089). We are also grateful to the Beijing Computational Science Research Center for generous grants of computer time.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01324.

Selected optimized geometrical structures (bond length Å and bond angle °) for the fϕ1fδ2 [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ (n = 0–6) at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ levels of theory with or without COSMO (in parentheses) (Table S1); selected optimized geometrical structures (bond length Å and bond angle °) for the reaction of fϕ2fδ2 [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ (n = 0–6) at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ levels of theory with or without COSMO (in parentheses) (Table S2); binding energy (kcal/mol) for the reaction of AmO22+ + nH2O → [AmO2(H2O)n]2+ (n = 0–6) at different levels of theory (Table S3); binding energy (kcal/mol) for the reaction of AmO21+ + nH2O → [AmO2(H2O)n]1+ (n = 0–6) at different levels of theory (Table S4); natural localized molecular orbital (NLMO) analyses of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 1–6) from open-shell B3LYP/cc-pVTZ/ECP60MWB_SEG calculations (Table S5); average Mayer, Gopinathan–Jug and Nalewajski–Mrozek bond orders for Am–Oyl and Am–Ow on the B3LYP-optimized geometry of AmO2(H2O)n2+/1+ (n = 0–6) at the SR–PBE/TZP level with COSMO (Table S6); average Mulliken and MDC_q charges and spin density on the B3LYP-optimized geometry of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 0–6) in solution from the PBE/TZP calculations (Table S7); calculated vibrational frequencies (cm–1) of [AmO2(H2O)n]2+/1+ (n = 0–6) in aqueous solution considered by COSMO at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ l level of theory (Table S8); ETS–NOCV energy decomposition analyses between the interacting fragments of AmO22+ and ligand units and their corresponding energy ΔEiorb (kcal/mol) on the B3LYP-optimized geometry of AmO2(H2O)n2+ (n = 1–5) in solution from an open-shell PBE/TZ2P calculation (Table S9); ETS–NOCV energy decomposition analyses between the interacting fragments of AmO21+ and ligand units and their corresponding energy ΔEiorb (kcal/mol) on the B3LYP-optimized geometry of AmO2(H2O)n1+ (n = 0–5) in solution from an open-shell PBE/TZ2P calculation (Table S10); two isomers (in-plane and perpendicular-to-plane) of water molecules for [AmO2(H2O)1]2+/1+ and [AmO2(H2O)2]2+/1+ at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ levels of theory (Figure S1); optimized geometry of D6h, Ci symmetry structures of [AmO2(H2O)6]2+ and [AmO2(H2O)7]2+ at SR-B3LYP/Am/ECP60MWB_SEG//O,H/cc-pVTZ levels of theory (Figure S2) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gagliardi L.; Roos B. O. Multiconfigurational quantum chemical methods for molecular systems containing actinides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 893–903. 10.1039/b601115m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Bursten B. E. Relativistic density functional study of the geometry, electronic transitions, ionization energies, and vibrational frequencies of protactinocene, Pa(η8-C8H8)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 11456–11466. 10.1021/ja9821145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet V.; Macak P.; Wahlgren U.; Grenthe I. Actinide chemistry in solution, quantum chemical methods and models. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 115, 145–160. 10.1007/s00214-005-0051-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J. K.; Haire R. G.; Santos M.; Marcüalo J.; de Matos A. P. Oxidation Studies of Dipositive Actinide Ions, An2+ (An = Th, U, Np, Pu, Am) in the Gas Phase: Synthesis and Characterization of the Isolated Uranyl, Neptunyl, and Plutonyl Ions UO22+ (g), NpO22+ (g), and PuO22+ (g). J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 2768–2781. 10.1021/jp0447340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B. M.; Balazs G.; Scheer M.; Tuna F.; McInnes E. J. L.; McMaster J.; Lewis W.; Blake A. J.; Liddle S. T. Triamidoamine uranium(IV)-arsenic complexes containing one-, two- and threefold U-As bonding interactions. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 582–590. 10.1038/nchem.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross J. N.; Su J.; Batista E. R.; Cary S. K.; Evans W. J.; Kozimor S. A.; Mocko V.; Scott B. L.; Stein B. W.; Windorff C. J.; Yang P. Covalency in Americium(III) Hexachloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8667–8677. 10.1021/jacs.7b03755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T.; Bursten B. E. Speciation of the Curium(III) Ion in Aqueous Solution: A Combined Study by Quantum Chemistry and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 5291–5301. 10.1021/ic0513787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsoyannis N. Transuranic computational chemistry. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 2815–2825. 10.1002/chem.201704445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P. G.; Bucher J. J.; Shuh D. K.; Edelstein N. M.; Reich T. Investigation of aquo and chloro complexes of UO22+, NpO2+, Np4+, and Pu3+ by X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 1997, 36, 4676–4683. 10.1021/ic970502m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Ohno A.; Tsushima S.; Takao K.; Rossberg A.; Funke H.; Scheinost A. C.; Bernhard G.; Yaita T.; Hennig C. Neptunium Carbonato Complexes in Aqueous Solution: An Electrochemical, Spectroscopic, and Quantum Chemical Study. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 11779–11787. 10.1021/ic901838r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knope K. E.; Soderholm L. Solution and solid-state structural chemistry of actinide hydrates and their hydrolysis and condensation products. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 944–994. 10.1021/cr300212f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi L.; Roos B. O. Coordination of the neptunyl ion with carbonate ions and water: A theoretical study. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 1315–1319. 10.1021/ic011076e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg D.; Karlstrom G.; Roos B. O.; Gagliardi L. The Coordination of Uranyl in Water: A Combined Quantum Chemical and Molecular Simulation Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14250–14256. 10.1021/ja0526719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gezahegne W. A.; Hennig C.; Tsushima S.; Planer-Friedrich B.; Scheinost A. C.; Merkel B. J. EXAFS and DFT Investigations of Uranyl Arsenate Complexes in Aqueous Solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2228–2233. 10.1021/es203284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet V.; Wahlgren U.; Schimmelpfennig B.; Moll H.; Zoltán S.; Grenthe I. Solvent Effects on Uranium(VI) Fluoride and Hydroxide Complexes Studied by EXAFS and Quantum Chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 3516–3525. 10.1021/ic001405n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J. P.; Sundararajan M.; Vincent M. A.; Hillier I. H. The geometric structures, vibrational frequencies and redox properties of the actinyl coordination complexes ([AnO2(L)n]m; An = U, Pu, Np; L = H2O, Cl–, CO32–, CH3CO2–, OH–) in aqueous solution, studied by density functional theory methods. Dalton Trans. 2009, 5902–5909. 10.1039/b901724k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K.; Chaudhuri D. Computational modeling of environmental plutonyl mono-, di- and tricarbonate complexes with Ca counterions: Structures and spectra: PuO2(CO3)22–, PuO2(CO3)2Ca, and PuO2(CO3)3Ca3. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 450, 196–202. 10.1016/j.cplett.2007.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K.; Cao Z. Theoretical Studies on Structures of Neptunyl Carbonates: NpO2(CO3)m(H2O)nq– (m = 1–3, n= 0–3) in Aqueous Solution. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 10510–10519. 10.1021/ic700486u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. X.; Liu J. J.; Gibson J. K.; Li J. Periodic Trends in Actinyl Thio-Crown Ether Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 2899–2907. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b03277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. X.; Li W. L.; Dong L.; Gibson J. K.; Li J. Crown ether complexes of actinyls: a computational assessment of AnO2(15-crown-5)2+ (An = U, Np, Pu, Am, Cm). Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 12354–12363. 10.1039/C7DT02825C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron F.; Pritchard B.; Bolvin H.; Autschbach J. Magnetic resonance properties of actinyl carbonate complexes and plutonyl(VI)-tris-nitrate. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 8577–8592. 10.1021/ic501168a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths T. L.; Martin L. R.; Zalupski P. R.; Rawcliffe J.; Sarsfield M. J.; Evans N. D. M.; Sharrad C. A. Understanding the Solution Behavior of Minor Actinides in the Presence of EDTA4–, Carbonate, and Hydroxide Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 3728–3727. 10.1021/ic302260a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankudinov A. L.; Conradson S. D.; de Leon J. M.; Rehr J. J. Relativistic XANES calculations of Pu hydrates. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 7518–7525. 10.1103/PhysRevB.57.7518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima S.; Yang T.; Mochizuki Y.; Okamoto Y. Ab initio study on the structures of Th(IV) hydrate and its hydrolysis products in aqueous solution. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 375, 204–212. 10.1016/S0009-2614(03)00806-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. P.; Dong C. Z.; Ding X. B. Theoretical study on structures and bond properties of NpO2m+ ions and NpO2(H2O)nm+ (m = 1–2, n = 1–6) complexes in the gas phase and aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 3253–3260. 10.1021/jp511265j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Niu W. X.; Gao T. Systematic analysis of structural and topological properties: new insights into PuO2(H2O)n2+ (n = 1–6) complexes in the gas phase. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4291–4296. 10.1039/C6RA27087E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chien W.; Anbalagan V.; Zandler M.; Van Stipdonk M.; Hanna D.; Gresham G.; Groenewold G. Intrinsic hydration of monopositive uranyl hydroxide, nitrate, and acetate cations. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 15, 777–783. 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsoyannis N. Covalency hinders AnO2(H2O)+ = AnO(OH)2+ isomerisation (An = Pa-Pu). Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 3158–3162. 10.1039/C5DT04317D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet V.; Privalov T.; Wahlgren U.; Grenthe I. The Mechanism of Water Exchange in AmO2(H2O)52+ and in the Isoelectronic UO2(H2O)5+ and NpO2(H2O)52+ Complexes as Studied by Quantum Chemical Methods. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 126, 7766–7767. 10.1021/ja0483544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J.; Yang X.; Liao J.; Liu N.; Yang Y.; Chai Z.; Wang D. A computational study on the complexation of Np(V) with N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-3-oxa-glutaramide (TMOGA) and its carboxylate analogs. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 16536–16546. 10.1039/C4CP01381F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone V.; Cossi M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. 10.1021/jp9716997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkoe P.; Li J.; Runeberg N. Quasirelativistic pseudopotential study of species isoelectronic to uranyl and the equatorial coordination of uranyl. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 4809–4813. 10.1021/j100069a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö P. Additive covalent radii for single-, double-, and triple-bonded molecules and tetrahedrally bonded crystals: A summary. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 2326–2337. 10.1021/jp5065819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram K. I. M.; Haller L. J.; Kaltsoyannis N. Density functional theory investigation of the geometric and electronic structures of [UO2(H2O)m(OH)n]2-n (n + m = 5). Dalton Trans. 2006, 43, 2403–2414. 10.1039/B517281K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C. J.; Bursten B. E. Comments Inorg. Chem. 1989, 9, 61–93. 10.1080/02603598908035804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bursten B. E.; Palmer E. J.; Sonnenberg J. L.. On the Role of f-Orbitals in the Bonding in f-Element Complexes: The “FEUDAL” Model as Applied to Organoactinide and Actinide Aquo Complexes; Special Publication-Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006; Vol. 305, pp 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Notter F. P.; Dubillard S.; Bolvin H. A theoretical study of the excited states of AmO2n+, n=1,2,3. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 164315 10.1063/1.2889004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas Ö.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, revision C.01; Wallingford CT: Gaussian, Inc., 2010.

- Guerra C. F.; Snijders J. G.; te Velde G.; Baerends E. J. Towards an order-N DFT method. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1998, 99, 391–403. 10.1007/s002140050353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velde G. T.; Bickelhaupt F. M.; Baerends E. J.; Guerra C. F.; Van Gisbergen S. J. A.; Snijders J. G.; Ziegler T. Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 931–967. 10.1002/jcc.1056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dolg M.; Cao X. Y. Relativistic pseudopotentials: Their development and scope of applications. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 403–480. 10.1021/cr2001383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X.; Dolg M.; Stoll H. Valence basis sets for relativistic energy-consistent small-core actinide pseudopotentials. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 487–496. 10.1063/1.1521431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall R. A.; Dunning T. H. Jr.; Harrison R. J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796–6806. 10.1063/1.462569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. R. Comment on Dunning’s correlation-consistent basis sets. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 260, 514–518. 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00917-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. 3. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W. T.; Parr R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron-density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt A.; Schüürmann G. COSMO–A new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 0, 799–805. 10.1039/P29930000799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allinger N. L.; Zhou X. F.; Bergsma J. Molecular mechanics parameters. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM 1994, 312, 69–83. 10.1016/S0166-1280(09)80008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R. J.; Musiał M. Coupled-cluster theory in quantum chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2007, 79, 291–352. 10.1103/RevModPhys.79.291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. D.; Gauss J.; Bartlett R. J. Coupled–cluster methods with noniterative triple excitations for restricted open–shell Hartree–Fock and other general single determinant reference functions. Energies and analytical gradients. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 8718–8733. 10.1063/1.464480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles P. J.; Hampel C.; Werner H.-J. Coupled cluster theory for high spin, open shell reference wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 5219–5227. 10.1063/1.465990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H. J., et al. MOLPRO; Univ. College Cardiff Consultants Limited: Cardiff, UK, 2012. http://www.molpro.net.

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic regular 2-component hamiltonians. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 4597–4610. 10.1063/1.466059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J.; Snijders J. G. Relativistic total energy using regular approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 9783–9792. 10.1063/1.467943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenthe E.; Baerends E. J. Optimized Slater-type basis sets for the elements 1–118. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1142–1156. 10.1002/jcc.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer I. Charge, bond order and valence in the ab inition SCF theory. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1983, 97, 270–274. 10.1016/0009-2614(83)80005-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinathan M. S.; Jug K. Valency. I. A quantum chemical definition and properties. Theor. Chim. Acta 1983, 63, 497–509. 10.1007/BF02394809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalewajski R. F.; Mrozek J. Modified valence indices from the two-particle density matrix. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1994, 51, 187–200. 10.1002/qua.560510403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalewajski R. F.; Mrozek J.; Michalak A. Two-electron valence indices from the Kohn-Sham orbitals. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1997, 61, 589–601. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken R. S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. 1. J. Chem. Phys. 1955, 23, 1833–1840. 10.1063/1.1740588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld F. L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge-densities. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. 10.1007/BF00549096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickelhaupt F. M.; Hommes N. J. R. V.; Guerra C. F.; Baerends E. J. The carbon-lithium electron pair bond in (CH3Li)n (n=1, 2, 4). Organometallics 1996, 15, 2923–2931. 10.1021/om950966x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swart M.; Van Duijnen P. T.; Snijders J. G. A charge analysis derived from an atomic multipole expansion. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 79–88. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak A.; De Kock R. L.; Ziegler T. Bond multiplicity in transition-metal complexes: applications of two-electron valence indices. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 7256–7263. 10.1021/jp800139g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler T.; Rauk A. On the calculation of bonding energies by the Hartree Fock Slater method. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 46, 1–10. 10.1007/BF02401406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler T.; Rauk A. A theoretical study of the ethylene-metal bond in complexes between Cu1+, Ag1+, Au1+, Pt0 or Pt2+ and ethylene, based on the Hartree-Fock-Slater transition-statemethod. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 1558–1565. 10.1021/ic50196a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Weinhold F. Natural localized molecular–orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 1736–1740. 10.1063/1.449360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Curtiss L. A.; Weinhold F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor–acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F.; Zipse H. Charge distribution in the water molecule--a comparison of methods. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 97–105. 10.1002/jcc.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. E.; Weinstock R. B.; Weinhold F. Natural–population analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 735–746. 10.1063/1.449486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J. D.; Pople J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XV. Extended Gaussian-type basis sets for lithium, beryllium, and boron. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 62, 2921–2923. 10.1063/1.430801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Weinhold F. Natural resonance theory: II. Natural bond order and valency. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 610–627. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Badenhoop J. K.; Reed A. E.; Carpenter J. E.; Bohmann J. A.; Morales C. M.; Weinhold F.. NBO 5.0 Theoretical Chemistry Institute; University of Wisconsin: Madison, 2001.

- Perdew J. P.; Emzerhof M.; Burke K. Rationale for mixing exact exchange with density functional approximations. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 9982–9985. 10.1063/1.472933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.