Abstract

MXenes are a class of two-dimensional (2D) transition-metal carbides and nitrides that are currently at the forefront of 2D materials research. In this study, we demonstrate the use of metallically conductive free-standing films of 2D titanium carbide (MXene) as current-collecting layers (conductivity of ∼8000 S/cm, sheet resistance of 0.5 Ω/sq) for battery electrode materials. Multilayer Ti3C2Tx (Tx: surface functional groups −O, −OH, and −F) is used as an anode material and LiFePO4 as a cathode material on 5 μm MXene films. Our results show that the capacities and rate performances of electrode materials using Ti3C2Tx MXene current collectors match those of conventional Cu and Al current collectors, but at significantly reduced device weight and thickness. This study opens new avenues for developing MXene-based current collectors for improving volumetric and gravimetric performances of energy-storage devices.

1. Introduction

Lightweight, flexible, portable electronic devices and wearable gadgets drive demand to develop compact and conformal energy-storage units.1−3 Li-ion batteries (LIBs) are currently the dominant technology for portable electronics. These batteries are also taking over the electric/hybrid electric vehicles market because of their high energy density and excellent energy efficiency.4,5 Metal current collectors such as copper (Cu) and aluminum (Al) are typically used as materials for anode and cathode, respectively. However, they do not contribute to capacity, but add up to the total weight and volume, thus reducing the overall energy density of LIB cells significantly. Moreover, the metal surface must be treated to ensure strong adhesion of electrode materials for minimizing the contact resistance and increasing capacity, rate capability, and cycling stability over a pristine metal surface covered with a native oxide layer.6,7 Importantly, the current collector should not only act as an electrical conductor between the electrode and external circuit but also as a compatible support for coating of electrode materials while being lightweight, mechanically strong, and electrochemically stable.

Traditional metal current collectors are considered to be passive components as they hardly contribute to the overall capacity while accounting for ∼15% (for Al metal collector) and ∼50% (for Cu collector) of total weight of the industrial-scale cathodes and anodes, respectively.8,9 This limitation has triggered efforts toward developing lightweight current collectors. A variety of carbon-based current collectors including carbon nanotubes,10−12 carbon paper,13,14 graphene paper,15−17 and carbon fiber18,19 were developed to replace traditional metal foils. For instance, Wang et al. employed current collectors based on superaligned carbon nanotube films, which also showed better wetting, stronger adhesion, and mechanical durability of cast electrode materials.20 Furthermore, Chen et al. have employed a highly conductive (∼3000 S/cm) reduced graphene oxide film produced by current-induced annealing and demonstrated its applicability as a current collector.21 However, electrical conductivity is still an issue for those carbon-based current collectors that may need processing at high temperatures to improve their conductivity. Thus, the development of solution-processable two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials with high electrical conductivity and low sheet resistance through ambient processing is important for fabrication of lightweight current collectors. This is especially true since such devices should be printable, flexible, transparent, and/or attached to a variety of surfaces for sensor networks and Internet of Things applications.

MXenes are a large family of 2D materials, comprising transition-metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides with a general formula, Mn+1XnTx, where M is an early transition metal, X is a carbon or nitrogen, and Tx stands for various surface terminations (−OH, −O, or −F groups).22 Because of their compositional versatility and intriguing physicochemical properties, MXenes have shown promise in a variety of applications including electromagnetic interference shielding,23 wireless communication,24 and energy storage.25−32 For instance, titanium carbide (Ti3C2) shows electrical conductivity up to 10 000 S/cm33 and is a 2D hydrophilic metal, obtained through solution processing.34 Recently, Peng et al. employed large-flake Ti3C2Tx as a current collector for demonstrating all-solid-state MXene microsupercapacitors without using metal current collectors.35 The metallic electrical conductivity, excellent flexibility, and mechanical strength of the delaminated Ti3C2Tx (d-Ti3C2Tx) films prompted us to employ them as current collectors for battery electrodes. Additionally, Ti3C2Tx MXene free-standing films have density 3 times lower density compared to that of Cu. These unique characteristics of titanium carbide MXene free-standing films have hardly been explored.

In this study, we employed a free-standing Ti3C2Tx film (∼5 μm thickness) as a current collector for casting anode and cathode materials in place of Cu and Al current collectors. To demonstrate the proof of concept, we have used multilayer Ti3C2Tx (ML-Ti3C2Tx) as an anode material and commercial LiFePO4 (LFP) as a cathode material at high mass loadings (2–9 mg/cm2).

2. Results and Discussion

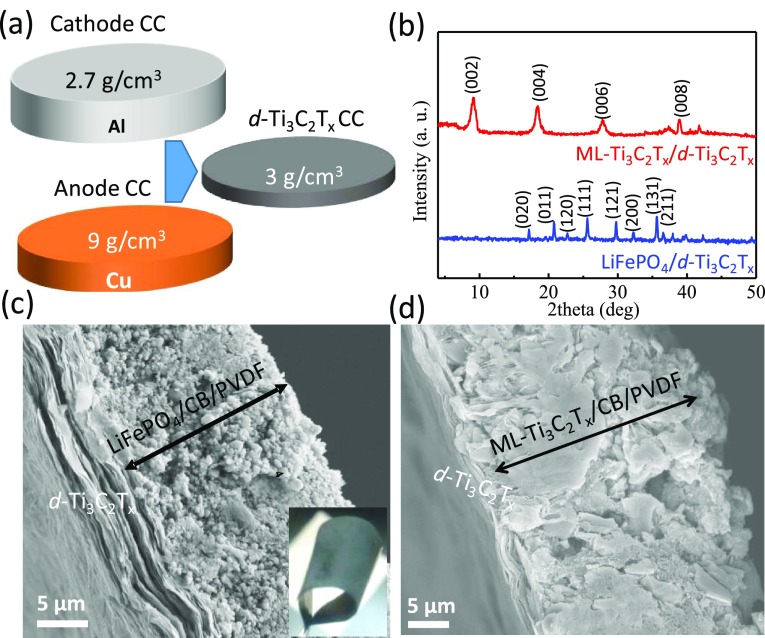

Ti3C2Tx was shown to exhibit the highest electrical conductivity in the MXene family and among other solution-processable 2D nanomaterials. Additionally, we found that thickness of MXene film less than 5 μm is sufficient for both electrical conduction and mechanical support36 for typical mass loadings of electrode materials in the range of 2–9 mg/cm2. The delaminated Ti3C2Tx (d-Ti3C2Tx) films (1–5 μm thick) were made by vacuum-assisted filtration and had a packing density of ∼3 g/cm3. This shows that the thin layers of MXene may have an advantage over LIB current collectors, including Al (thickness = 20 μm, density = 2.7 g/cm3) and Cu foils (thickness = 12 μm, density = 9 g/cm3).1 The schematic shown in Figure 1a illustrates the comparison between d-Ti3C2Tx free-standing films and traditional Al and Cu metal current collectors. The density of d-Ti3C2Tx is similar to that of Al, while it is 3 times lower compared to that of Cu. This is an advantage of using Ti3C2Tx MXene current collector for reducing the total volume and weight of LIB electrodes by at least 3 times.

Figure 1.

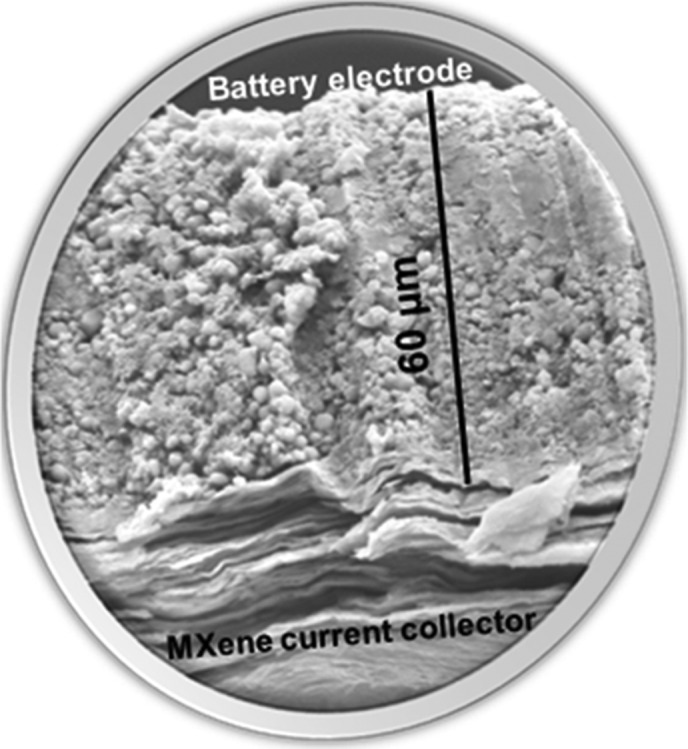

(a) Schematic illustration of Cu and Al foils in comparison with MXene film, where density values are provided. (b) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of LFP and ML-Ti3C2Tx cast on d-Ti3C2Tx. Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showing (c) LiFePO4/d-Ti3C2Tx, the inset shows the digital photograph of the flexible film, and (d) ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx film. CC: current collector; CB: carbon black; PVDF: poly(vinylidene fluoride).

The XRD patterns of multilayer Ti3C2Tx (ML-Ti3C2Tx) and LiFePO4 cast on d-Ti3C2Tx film are shown in Figure 1b. The d-spacing of ML-Ti3C2Tx was found to be 9.6 Å. LiFePO4 XRD pattern is in good agreement with the literature reports. Figure 1c,d shows cross-sectional images of LiFePO4/d-Ti3C2Tx and ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx electrodes, respectively. As shown in the SEM images, the interface between d-Ti3C2Tx film and coated layer was uniform without voids or deformation, confirming the good connection between d-Ti3C2Tx film and electrode materials. The highly flexible nature of the cast electrode on d-Ti3C2Tx film can be demonstrated through bending the entire stack to extreme angles, up to 180°, as shown in the inset of Figure 1c. We have not observed any crack formation after bending the electrode for repeated bending cycles, indicating the mechanical integrity of the entire electrode stack (60 μm) on d-Ti3C2Tx film. The optimal thickness of electrode materials (for single side coating) is found to be 10 times that of MXene film thickness.

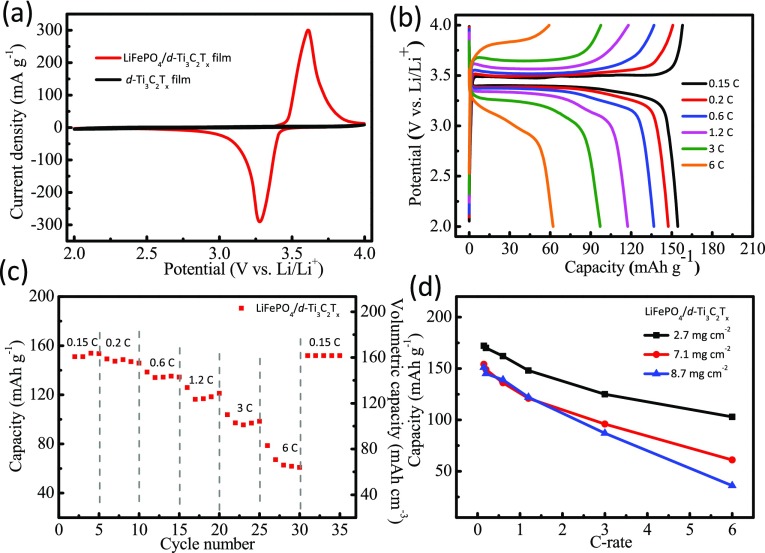

The electrochemical performance of LiFePO4/d-Ti3C2Tx film was studied at different mass loadings (Figure 2). The cyclic voltammograms of LiFePO4/d-Ti3C2Tx and bare d-Ti3C2Tx electrodes were compared at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s, as shown in Figure 2a. Distinctive sharp oxidation and reduction peaks were observed at 3.61 and 3.27 V (vs Li/Li+), corresponding to Li+ extraction and insertion in the LiFePO4 structure (Fe2+/Fe3+), respectively. In contrast, bare d-Ti3C2Tx film showed very low current response in the cyclic voltammetry (CV) scan, indicating the electrochemical stability of the compact d-Ti3C2Tx film. Since the mass loading of active layer is >3 mg/cm2, we have not noticed any parasitic reactions due to interaction of electrolyte with the functional groups on MXene sheets. At such high mass loadings, MXene serves only as a passive current collector as it is coated densely by the electrode materials.

Figure 2.

Electrochemical performance of LiFePO4 coated on d-Ti3C2Tx film. (a) Cyclic voltammograms of LFP/d-Ti3C2Tx and d-Ti3C2Tx films at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s. (b) Charge/discharge profiles of LFP/d-Ti3C2Tx at various C-rates, (c) rate performance, and (d) capacity versus C-rates at different mass loadings of 2.7, 7.1, and 8.7 mg/cm2.

Figure 2b shows charge/discharge profiles of LiFePO4 (7.1 mg/cm2) measured in the range of 0.15C–6C rates, and the corresponding discharge capacities were estimated to be 155, 147, 137, 117, 97, and 62 mAh/g. As shown in Figure 2c, when the C-rate is increased from 0.15 to 6C, the electrode retains 40% of its initial capacity, which means that the conductivity of d-Ti3C2Tx film is sufficient for characterizing the electrochemical performance of LiFePO4 electrodes at a thickness of 60 μm. After reverting to 0.15C rate, the capacity rebounded to its initial values (155 mAh/g and 165 mAh/cm3) and remained stable, confirming the reversibility and suggesting that no degradation occurred during high-rate cycling of LiFePO4/d-Ti3C2Tx electrodes. Figure 2d shows the capacity versus C-rate measured for different LiFePO4 loadings (2.7, 7.1, and 8.7 mg/cm2) on d-Ti3C2Tx film. Even at a mass loading of 8.7 mg/cm2, LFP electrode showed a capacity of 122 mAh/g at 1.2 C rate, which matches with the literature reports employing traditional Al current collectors at similar mass loadings of electrode materials.37

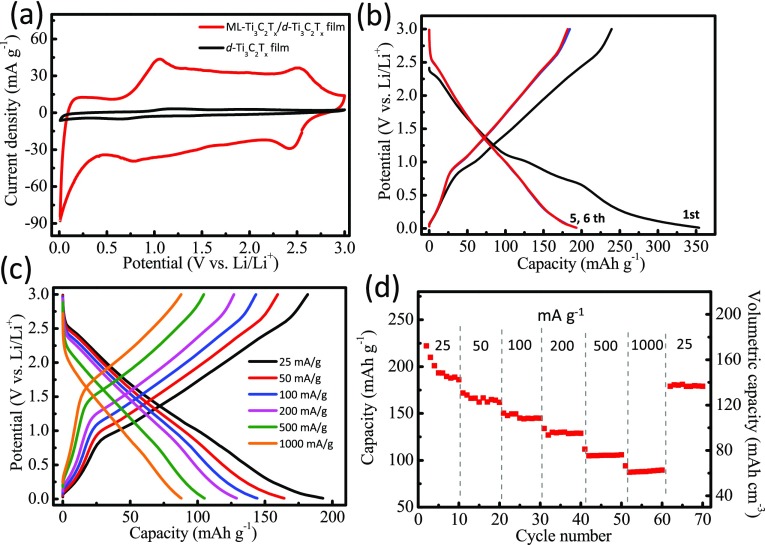

Ti3C2Tx MXene has been explored for electrochemical storage because of its layered morphology with electrochemically active surfaces available for metal-ion storage.27−30,38,39 Electrochemical performance of ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx is shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a compares the CV profiles of ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx electrode and bare d-Ti3C2Tx film at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s. As shown in the CV curves, the capacity of bare d-Ti3C2Tx film is much smaller than that of ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx electrode, meaning that the major capacity contribution is from the top ML-Ti3C2Tx. The typical areal mass loading of ML-Ti3C2Tx is ∼3.9 mg/cm2. Sloping charge/discharge profiles are typical of MXenes electrodes, as shown in Figure 3b,c. ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx electrode showed first-cycle Coulombic efficiency of 67% at a current density of 25 mA/g and stabilized capacity of 180 mAh/g after fifth cycle. When current density was increased to 1 A/g, the capacity decreased to 87 mAh/g with 48% capacity retention (Figure 3d). The capacity also rebounded to the initial value of 180 mAh/g (Figure 3d) by reverting current density to 25 mA/g, indicating good rate capability and reversibility of ML-Ti3C2Tx/d-Ti3C2Tx electrode.

Figure 3.

Electrochemical performance of ML-Ti3C2Tx coated on d-Ti3C2Tx film. (a) Cyclic voltammograms at 0.1 mV/s. (b) Charge–discharge curves for first, fifth, and sixth cycles at a current density of 25 mA/g. (c) Charge–discharge curves at different current densities. (d) Rate performance showing gravimetric and volumetric capacities at varied current densities.

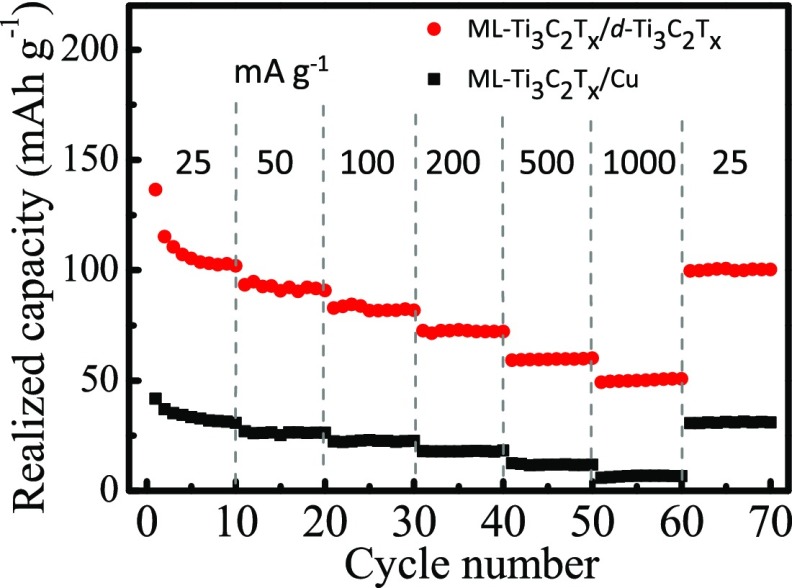

The realized capacity of the electrodes was calculated by considering the total weight (estimated on the basis of density of the current collectors but not relying on the absolute thickness values), including current collector and active material stack used for testing half-cell measurements. There is not much gain using MXene current collector instead of Al because of same values of density in both cases (at the same thickness level). As shown in Figure 4, the gravimetric capacity obtained using d-Ti3C2Tx film is 3 times higher than using a Cu foil as a current collector. This is clearly an advantage for using highly conductive MXene films, which can effectively reduce the total weight of the anode stack of LIB. This study is a demonstration of the concept of using MXene current collectors; however, future studies should focus on the influence of the surface functionality of MXenes on the contact impedance using systematic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy investigations and further improvements through surface modifications.

Figure 4.

Realized capacity (based on the total weight of active materials and the current collector) of ML-Ti3C2Tx (on a Cu foil) and ML-Ti3C2Tx (on d-Ti3C2Tx film) electrodes at different current densities.

Although this study demonstrated the feasibility of MXene thin films as current collectors in small devices, the thermal characteristics of MXene films should be studied to ensure efficient heat dissipation during battery cycling. Heat produced during charging/discharging of battery electrodes in large-size batteries can be dissipated easily if the current collector has a high thermal conductivity. Tensile strength of MXene current collectors should also be investigated to ensure that winding of electrodes is possible. However, the available data on single-layer MXene flakes40 and films41 suggest that the required mechanical strength can be achieved. However, there is no published information about thermal conductivity of Ti3C2 films. Future investigations should focus on these issues to validate the viability of MXene films as current collectors in a variety of batteries.

3. Conclusions

We demonstrated application of a highly conductive thin d-Ti3C2Tx current collector for cathode and anode electrode materials instead of traditional metal collectors. Ti3C2Tx film showed compatibility with coatings of LiFePO4 and ML-Ti3C2Tx electrodes without additional surface treatments. Compared to Cu metal foil, d-Ti3C2Tx film offered reduced cell weight and improved volumetric capacity for anode electrode stack. Our results suggest that MXene current collector could be a potential candidate for developing flexible and lightweight energy-storage devices.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Fabrication of Ti3C2Tx Films

All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Layered ternary carbide Ti3AlC2 (MAX phase) powder (particle size <40 μm) was obtained from Carbon-Ukraine, Ltd. Ti3C2Tx MXene was synthesized following the minimal intensive layer delamination method by selective etching of aluminum from Ti3AlC2 using in situ hydrofluoric acid (HF)-forming etchant, as previously reported elsewhere.34 Herein, 1 g of Ti3AlC2 powder was slowly added into a solution of 1 g of lithium fluoride (LiF, Alfa Aesar, >98%) in 20 mL of 9 M hydrochloric acid (HCl, Fisher, technical grade, 35–38%) and stirred for 24 h at 35 °C. The acidic suspension was washed with deionized (DI) water until pH ≥ 6 via centrifugation at 3500 rpm (5 min per cycle) and decantation of the supernatant after each cycle. Around pH ≥ 6, a stable dark-green supernatant of Ti3C2Tx was observed and then collected after 30 min centrifugation at 3500 rpm. The resulting delaminated Ti3C2Tx (d-Ti3C2Tx) was filtered and dried under vacuum at 70 °C overnight to obtain free-standing films.

4.2. Synthesis of Multilayer Ti3C2Tx

The etching solution was prepared by adding 1 mL of concentrated HF to 9 mL of H2O to produce 5 wt % HF, which was used for etching 1 g of Ti3AlC2 powder. While stirring at 400 rpm, Ti3AlC2 powder was slowly added to the etchants and the temperature of the bath was raised to 40 °C after the complete addition of MAX powder and the reaction was continued for 15 h. Furthermore, washing was done with DI water via centrifugation for 5 min at 3500 rpm several times. The colorless acidic supernatant was decanted after each wash until reaching pH ≥ 6. After this stage, the product was collected via vacuum filtration over a filter membrane with pore size less than 0.45 μm. Then, the obtained powder sample was dried at 200 °C under vacuum for 12 h.

4.3. Materials Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of ML-Ti3C2Tx, and LiFePO4 (MTI Corp., product #EQ-Lib-LFPOKJ2) was performed on a Rigaku Smart Lab (Tokyo, Japan) diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å. Voltage and current settings were 40 kV and 44 mA, respectively, with a step scan of 0.04°, 2θ range 5–50°, and dwell time of 0.5 s. The cross sections of the samples were imaged using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Zeiss Supra 50VP, Germany). The electrical conductivity of the samples was measured using a four-point probe (ResTest v1, Jandel Engineering Ltd., Bedfordshire, U.K.) with a probe distance of 1 mm.

4.4. Coin Cell Assembly and Electrochemical Analysis

LiFePO4 (MTI Corp., product #EQ-Lib-LFPOKJ2) and ML-Ti3C2Tx were used as active materials to cast on d-Ti3C2Tx films. The electrodes were prepared by mixing active materials (80 wt %), carbon black (10 wt %), and poly(vinylidene difluoride) binder (10 wt %) in N-methylpyrrolidone to make a slurry separately. After mixing, a uniform slurry was coated on d-Ti3C2Tx film and dried under vacuum at 70 °C for 12 h. For comparison, LiFePO4 and Ti3C2Tx slurries were coated on Al and Cu foils, respectively, using the same procedure mentioned above.

After drying, electrodes were roll-pressed and punched to match the required dimensions of CR2032 coin cell. A lithium foil was used as the reference and counter electrode for half-cell measurements. Celgard polypropylene membrane was used as a separator between working electrodes and Li metal. 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in ethylene carbonate and diethyl carbonate with a volume ratio of 1:1 was used as the electrolyte. The CR2032 coin cells were assembled in an argon-filled glovebox (VT, Vacuum Technologies) with moisture and oxygen levels less than 0.1 ppm. Charge–discharge measurements were performed at different current densities in the potential windows matching the chosen electrode system using an Arbin battery tester (Arbin BT-2143-11U, College Station, TX). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was conducted using VMP3 (BioLogic, France) between 0.01 and 3.0 V versus Li/Li+ at a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s.

Acknowledgments

C.-H.W. was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under Grant No. 105-2917-I-008-008. Research reported in this publication was supported by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) under the KAUST-Drexel Competitive Research Grant (URF/1/2963-01-01). We thank Evan Quain for helpful comments on this article.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Wang X.; Lu X.; Liu B.; Chen D.; Tong Y.; Shen G. Flexible energy-storage devices: Design consideration and recent progress. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 4763–4782. 10.1002/adma.201400910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Wu Z.; Yuan S.; Zhang X.-B. Advances and Challenges for flexible energy storage and conversion devices and systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2101–2122. 10.1039/c4ee00318g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf M.; Shi H. T. H.; Wang Y.; Chen Y.; Ma Z.; Cao A.; Naguib H. E.; Han R. P. S. Novel pliable electrodes for flexible electrochemical energy storage devices: recent progress and challenges. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600490 10.1002/aenm.201600490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarascon J.-M.; Armand M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 2001, 414, 359–367. 10.1038/35104644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough J. B.; Kim Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 587–603. 10.1021/cm901452z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Song M.-S.; Kong B.; Cui Y. Flexible and stretchable energy storage: recent advances and future perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 160343 10.1002/adma.201603436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman E.; Zakri W.; Sanatimoghaddam M. H.; Modjtahedi A.; Pathak S.; Kashkooli A. G.; Garafolo N. G.; Farhad S. A review of inactive materials and components of flexible lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sustainable Syst. 2017, 1, 1700061 10.1002/adsu.201700061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. A.; White R. E. Characterization of commercially available lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 1998, 70, 48–54. 10.1016/S0378-7753(97)02659-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G.; Li F.; Cheng H.-M. Progress in flexible lithium batteries and future prospects. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1307–1338. 10.1039/C3EE43182G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. W.; Wu Z. P.; Zhong S. W.; Zhong W. B.; Suresh S.; Metha A.; Koratkar N. Folding insensitive, high energy density lithium-ion battery featuring carbon nanotube current collectors. Carbon 2015, 87, 292–298. 10.1016/j.carbon.2015.02.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.-F.; Hu L.; Choi J. W.; Cui Y. Light-weight free-standing carbon nanotube-silicon films for anodes of lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3671–3678. 10.1021/nn100619m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W.; Gallant B. M.; Lee Y.; Yoshida N.; Kim D. Y.; Yamada Y.; Noda S.; Yamada A.; Shao-Horn Y. Self-standing positive electrodes of oxidized few-walled carbon nanotubes for light-weight and high-power lithium batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5437–5444. 10.1039/C1EE02409D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbizzani C.; Lazzari M.; Mastragostino M. Lithiation/delithiation performance of Cu6Sn5 with carbon paper as current collector. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A289–A294. 10.1149/1.1839466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.; Liu X.; Qi H.; Li W.; Zhou Y.; Yao M.; Li B. High-performance lithium-sulfur batteries with a cost-effective carbon paper electrode and high sulfur-loading. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 6394–6401. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rana K.; Singh J.; Lee J.-T.; Park J. H.; Ahn J.-H. Highly conductive freestanding graphene films as anode current collectors for flexible lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 11158–11166. 10.1021/am500996c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwon H.; Kim H.-S.; Lee K. U.; Seo D.-H.; Park Y. C.; Lee Y.-S.; Ahn B. T.; Kang K. Flexible energy storage devices based on graphene paper. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1277–1283. 10.1039/c0ee00640h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Chen Z.; Ren W.; Li F.; Cheng H.-M. Flexible Graphene-based lithium ion batteries with ultrafast charge and discharge rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 17360–17365. 10.1073/pnas.1210072109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Sun A.; Wang C. A Porous silicon-carbon anode with high overall capacity on carbon fiber current collector. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 981–984. 10.1016/j.elecom.2010.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martha S. K.; Kiggans J. O.; Nanda J.; Dudney N. J. Advanced lithium battery cathodes using dispersed carbon fibers as the current collector batteries and energy storage. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A1060–A1066. 10.1149/1.3611436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Luo S.; Wu Y.; He X.; Zhao F.; Wang J.; Jiang K.; Fan S. Super-aligned carbon nanotube films as current collectors for lightweight and flexible lithium ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 846–853. 10.1002/adfm.201202412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Fu K.; Zhu S.; Luo W.; Wang Y.; Li Y.; Hitz E. M.; Yao Y.; Dai J.; Wan J.; Danner V. A.; Li T.; Hu L. Reduced graphene oxide films with ultra-high conductivity as Li-ion battery current collectors. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 3616–3623. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anasori B.; Lukatskaya M. R.; Gogotsi Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16098 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.98. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad F.; Alhabeb M.; Hatter B. C.; Anasori B.; Hong S. M.; Koo C. M.; Gogotsi Y. Electromagnetic interference shielding with 2D transition metal carbides (MXenes). Science 2016, 353, 1137–1140. 10.1126/science.aag2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarycheva A.; Polemi A.; Liu Y.; Dandekar K.; Anasori B.; Gogotsi Y. 2D titanium carbide (MXene) for wireless communication. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau0920 10.1126/sciadv.aau0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Mathis T. S.; Zhao M.-Q.; Anasori B.; Dang A.; Zhou Z.; Cho H.; Gogotsi Y.; Yang S. Thickness-independent capacitance of vertically aligned liquid-crystalline MXenes. Nature 2018, 557, 409–412. 10.1038/s41586-018-0109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukatskaya M. R.; Mashtalir O.; Ren E. C.; Dall’Agnese Y.; Rozier P.; Taberna P. L.; Naguib M.; Simon P.; Barsoum M. W.; Gogotsi Y. Cation intercalation and high volumetric capacitance of two-dimensional titanium carbide. Science 2013, 341, 1502–1505. 10.1126/science.1241488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Kajiyama S.; Iinuma H.; Hosono E.; Oro S.; Moriguchi I.; Okubo M.; Yamada A. Pseudocapacitance of MXene nanosheets for high-power sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6544 10.1038/ncomms7544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiyama S.; Szabova L.; Sodeyama K.; Iinuma H.; Morita R.; Gotoh K.; Tateyama Y.; Okubo M.; Yamada A. Sodium-ion intercalation mechanism in MXene nanosheets. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3334–3341. 10.1021/acsnano.5b06958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VahidMohammadi A.; Hadjikhani A.; Shahbazmohamadi S.; Beidaghi M. Two-dimensional vanadium carbide (MXene) as a high-capacity cathode material for rechargeable aluminum batteries. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11135–11144. 10.1021/acsnano.7b05350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q.; Kurra N.; Alhabeb M.; Gogotsi Y.; Alshareef H. N. All pseudocapacitive MXene-RuO2 asymmetric supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703043 10.1002/aenm.201703043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L.; Hu L.; Anasori B.; Liu Y.-T.; Zhu Q.; Zhang P.; Gogotsi Y.; Xu B. MXene-bonded activated carbon as a flexible electrode for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1597–1603. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-T.; Zhang P.; Sun N.; Anasori B.; Zhu Q.-Z.; Liu H.; Gogotsi Y.; Xu B. Self-assembly of transition metal oxide nanostructures on MXene nanosheets for fast and stable lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707334 10.1002/adma.201707334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. J.; Anasori B.; Seral-Ascaso A.; Park S.-H.; McEvoy E.; Shmeliov A.; Duesberg G. S.; Coleman J. N.; Gogotsi Y.; Nicolosi V. Transparent, flexible, and conductive 2D titanium carbide (MXene) films with high volumetric capacitance. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702678 10.1002/adma.201702678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhabeb M.; Maleski K.; Anasori B.; Lelyukh P.; Clark L.; Sin S.; Gogotsi Y. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7633–7644. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. Y.; Akuzum B.; Kurra N.; Zhao M.-Q.; Alhabeb M.; Anasori B.; Kumbur E. C.; Alshareef H. N.; Ger M.-D.; Gogotsi Y. All-MXene (2D titanium carbide) solid-state microsupercapacitors for on-chip energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2847–2854. 10.1039/C6EE01717G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurra N.; Alhabeb M.; Maleski K.; Wang C.-H.; Alshareef H.; Gogotsi Y. Bistacked titanium carbide (MXene) anodes for hybrid sodium ion capacitors. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 2094–2100. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta N.; Wu F.; Lee J. T.; Yushin G. Li-ion battery materials: present and future. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 252–264. 10.1016/j.mattod.2014.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiyama S.; Szabova L.; Iinuma H.; Sugahara A.; Gotoh K.; Sodeyama K.; Tateyama Y.; Okubo M.; Yamada A. Enhanced Li-ion accessibility in MXene titanium carbide by steric chloride termination. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601873 10.1002/aenm.201601873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.; Cao G.; Yi S.; Zhang X.; Li C.; Sun X.; Wang K.; Ma Y. Binder-free 2D titanium carbide (MXene)/carbon nanotube composites for high-performance lithium-ion capacitors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 5906–5913. 10.1039/C8NR00380G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipatov A.; Lu H.; Alhabeb M.; Anasori B.; Gruverman A.; Gogotsi Y.; Sinitskii A. Elastic properties of 2D Ti3C2Tx MXene monolayers and bilayers. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat0491 10.1126/sciadv.aat0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z.; Ren C. E.; Zhao M.-Q.; Yang J.; Giammarco J. M.; Qiu J.; Barsoum M. W.; Gogotsi Y. Flexible and conductive MXene films and nanocomposites with high capacitance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 16676–16681. 10.1073/pnas.1414215111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]