Abstract

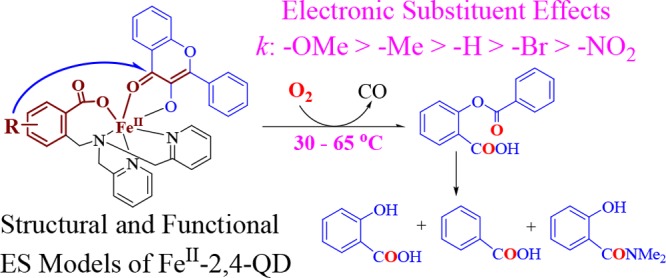

With the aim of revealing the catalytic role of atypically coordinated (3His-1Glu) active site mononuclear non-heme Fe(II)-dependent quercetin 2,4-dioxygenase (Fe-2,4-QD) and the electronic effects of the model ligands on the reactivity toward dioxygen, a set of p/m-R-substituted carboxylate-containing ligand-supported Fe(II)-3-hydroxyflavonolate complexes, [FeIILR(fla)] (LRH: 2-{[bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)amino]methyl}-p/m-R-benzoic acid; R: p-OMe (1), p-Me (2), m-Br (4), and m-NO2 (5); fla: 3-hydroxyflavonolate), were synthesized and characterized as structural and functional models for the ES (enzyme–substrate) complexes of Fe-2,4-QD. [FeIILR(fla)] show relatively high enzyme-type reactivity (dioxygenative ring opening of the coordinated substrate fla, single-turnover reaction) at low temperatures (30–65 °C). The reaction shows a linear Hammett plot (ρ = −1.21), and electron donating groups enhance the reaction rates. The notable difference on the reactivity can be rationalized from the electronic nature of the substituent in the ligands, which could tune the reactivity via tuning Lewis acidity of the Fe(II) ion, electron density, and the redox potential of fla. The properties and the reactivity show approximately linear correlations between λmax or E1/2 of fla and the reaction rate constant k. This work sheds light not only on understanding of electronic effects of the ligands and the property–reactivity relationship but also on the role of the catalytic reaction by Fe-2,4-QD.

Introduction

Mononuclear non-heme Fe(II)-dependent enzymes (MNHEs) act pivotal roles in the O2 metabolism, catalyze an amazing variety of oxidative reactions, and have potential medical and pharmaceutical applications.1 Generally, the Fe(II) ion in the active sites of MNHEs is coordinated by two histidine imidazoles and a carboxylate group of Glu or Asp in a “facial triad” mode. However, atypical coordination modes, such as the three histidine imidazoles 3His mode [as observed in diketone dioxygenase (Dke1)2 and cysteine dioxygenase (CDO)3], or three histidine imidazoles and a carboxylate 3His-1Glu mode [as observed in acireductone dioxygenase (ARD)4 and quercetin 2,4-dioxygenase (2,4-QD)5], were also reported recently. The active site structure–function relationship of different active site MNHEs is very interesting and fascinating. Compared with the well-studied typically coordinated MNHEs, biomimetic research of the atypically coordinated MNHEs, especially those bearing the 3His-1Glu mode and the structure–function relationship of different active site MNHEs, remains largely undeveloped.

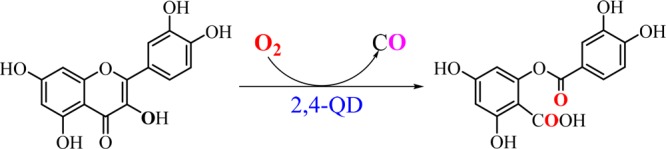

In the initial step of the quercetin catabolism, 2,4-QD activates dioxygen to catalyze the oxygenative O-heterocycle ring opening reaction of flavonoid quercetin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavonol, QUE) to the corresponding phenolic carboxylic acid esters and release carbon monoxide (Scheme 1).6

Scheme 1. Reaction of QUE with Dioxygen Catalyzed by 2,4-QD.

The fungal 2,4-QD7−9 is the only known Cu(II)-dependent dioxygenase (Cu-2,4-QD) and has a mononuclear type II Cu(II) reaction center. The active site of 2,4-QD from Aspergillus japonicas comprises two distinct coordination environments. In the first case, the Cu(II) is coordinated by a carboxylate group of Glu73, three histidine imidazoles, and one water molecule to form a distorted trigonal-bipyramidal geometry, whereas another exhibits a distorted tetrahedral geometry without the binding of Glu73.7 In the enzyme–substrate (ES) complex, the Cu(II) active site shows a distorted square pyramidal geometry, in which a deprotonated substrate 3-hydroxyflavonolate (fla) is bound to Cu(II) via the 3-hydroxy group with the displacement of the water molecule.10 The mutation of Glu73 induces a loss of enzyme activity,7 implying that the Glu73 carboxylate group acts an essential catalytic role.10

The bacterial 2,4-QD from Bacillus subtilis(5,11,12) is an FeII-dependent dioxygenase (Fe-2,4-QD). It has an atypically coordinated mononuclear non-heme Fe(II) active site, which also exhibits two distinct structures similar to that of Cu-2,4-QD.5 In the N- or C-terminal cupin motif, the Fe(II) active site shows a distorted trigonal bipyramidal or a square pyramidal geometry involving three histidine imidazoles, a water molecule, and one Glu69 (2.10 Å) or Glu241 (2.44 Å, weakly coordinated).5

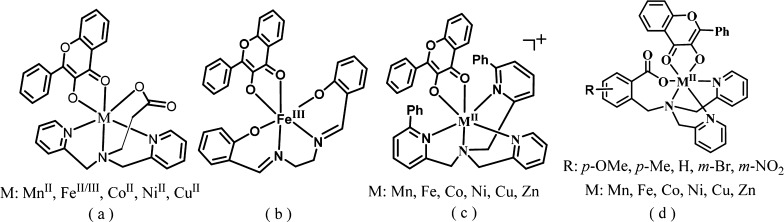

So far, a lot of Cu-2,4-QD models have been reported,13−16 though other metal-based models, especially those containing iron, are still rare,16e,17–24 Currently, only five structurally characterized Fe–fla complexes—[FeIII(fla)(L1)]ClO4 (L1: N-propanoate-N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine) (Figure 1a),17 [FeIII(4′-MeOfla)3],18 [FeIII(fla)(salen)] (salenH2: 1,6-bis-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2,5-diaza-hexa-1,5-diene) (Figure 1b),19 [FeIII(fla)2Cl(MeOH)],20 and [FeIILH(fla)] (LHH: 2-{[bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)amino]methyl}benzoic acid) (Figure 1d)21a—have been reported, though their oxidation states are not the same as that in the ES adduct of the FeII-2,4-QD except [FeIILH(fla)]. There are only three examples of Fe(II)–fla complexes to mimic FeII-2,4-QD: [FeII(fla)(L1)],17 [(6-Ph2TPA)FeII(fla)]ClO4 (6-Ph2TPA: N,N-bis((6-phenyl-2-pyridyl)methyl)-N-((2-pyridyl)methyl)amine) (Figure 1c),22 and [FeIILH(fla)].21a However, [FeII(fla)(L1)]17 and [(6-Ph2TPA)FeII(fla)]ClO422 are not crystallographically characterized, and the reactivity of [FeII(fla)(L1)]17 toward dioxygen is lower and requires higher temperatures (65–80 °C) relative to [FeIILH(fla)]. Besides, [(6-Ph2TPA)FeII(fla)]ClO4 reacts with O2 to give a diiron(III) μ-oxo complex [(6-Ph2TPAFeIII(fla))2(μ-O)](ClO4)2.22 No enzyme-type dioxygenation reactivity study has been done for this complex. Thus, [FeIILH(fla)] is the only crystallographically characterized FeII–fla complex with a higher enzyme-type dioxygenation reactivity reported previously by our group.21a

Figure 1.

(a–d) Structures of the previously reported ES model complexes. (d) Structures of the model complexes (M: Fe) in this work.

Most of the reported 2,4-QD model complexes are supported by polyamine ligands. The role of the active site carboxylate group of Glu of the enzyme has not received much attention, and little attempts have been made to design carboxylate-containing ligands. Up to now, there are only three types of carboxylate-containing ligand-supported ES model complexes of 2,4-QD. They are [MII(fla)(L1)] (M: Mn, FeII/III, Co, Ni, Cu),17 [MIILR(fla)] (M: Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn; LRH: 2-{[bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)amino]methyl}-p/m-R-benzoic acid; R: p-OMe, p-Me, -H, m-Br, and m-NO2) (Figure 1d),21,23,24 and [CuIILn(fla)] (L1/2H: 2/3-((bis(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)amino)methyl)benzoic acid; L3/4H: 2/3-((bis(2-(pyridin-2-yl)ethyl)amino)methyl)benzoic acid).21a,25

Generally, the active site residues of the enzyme and their substituent groups, with the aid from the second coordination sphere, are important factors to stabilize the intermediates, tune the catalytic activity, and the conformation of the enzyme via influencing the coordination geometry of the metal cofactor. There are some reports about the biomimetic studies that focus on the electronic substituent effects of the substrate fla on the reactivity.13−16,19,26,27 However, as we know, there are only two reports that focus on the electronic effects of the substituent group of the model ligands of Co(II) and Ni(II) ES model complexes on their reactivities.23,24 No report focused on the electronic effects of the substituent group in the model ligands of Fe(II) ES model complexes on their reactivities has been published yet.

With an aim to investigate the electronic substituent effects of the model ligands on the chemical functions of Fe-2,4-QD and the active site structure–function relationship of different active site MNHEs, we synthesized and characterized a set of structural and functional FeII–fla ES model complexes [FeIILR(fla)] (R: p-OMe (1), p-Me (2), m-Br (4), and m-NO2 (5)) (Figure 1d) ([FeIILH(fla)] (3) has already been reported in our previous paper21a) of Fe-2,4-QD using p/m-substituted carboxylate-containing ligands. A detailed investigation on their structures, physicochemical properties, electrochemical properties, and dioxygenation reactivity is presented.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Characterization

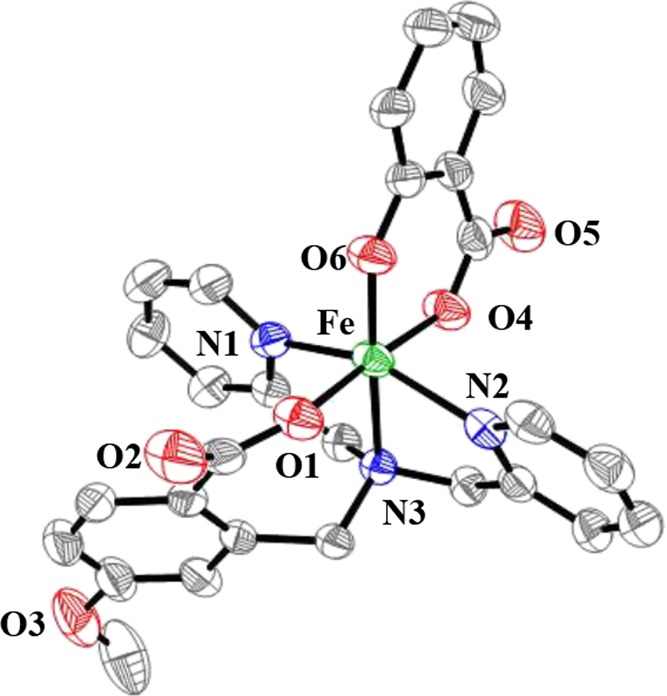

The ligands LRH (Figure 1d) were synthesized based on the reported methods.23 The reaction of FeII(OAc)2 with the neutral ligand LRH and flavonol (flaH) under N2 gave the corresponding complexes [FeIILR(fla)] (R: p-OMe (1), p-Me (2), m-Br (4), and m-NO2 (5)). No additional base was added during the reaction, and the acetate ions (AcO–) were proposed to act as proton acceptors. All complexes are relatively stable under air in the solid state, but very sensitive to air in solution (see below). Thus, their single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallographic analysis cannot be obtained successfully. Only a single crystal of one of the oxidized dioxygenation products, salicylate (sal) complex [FeIIILOMe(sal)]·H2O (1′), was obtained during recrystallization of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) by slow diffusion of ether into the dichloromethane solution of 1 without N2 protection at room temperature. The structure is shown in Figure 2. The crystallographic data and the selected bond lengths and angles are summarized in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

Figure 2.

ORTEP (50% ellipsoid) representation of [FeIIILOMe(sal)]·H2O (1′). For clarity, hydrogen atoms and free solvent molecules are omitted.

1′ crystallizes in the monoclinic P2(1)/n space group. It has a mononuclear structure, and the FeIII ion is coordinated by O(4) (carboxylate) and O(6) (2-hydroxylate) of sal, O(1) (benzoate) of LOMe, and three nitrogen atoms of LOMe to form a distorted octahedral geometry. The axial positions are occupied by O(6) and N(3) atoms (amine nitrogen atom).

The bond lengths of Fe–O(1) (benzoate of LOMe) is 1.940(3) Å, which is shorter than those of the resting FeII-2,4-QD (2.10 Å)5 and the nonsubstituted derivative [FeIILH(fla)] (2.0256(18) Å)21a but close to that of [FeIII(fla)(L1)]ClO4 (1.909(5) Å).17 The bond lengths of Fe–O(4) and Fe–O(6) (oxygen atoms of salicylate) are 1.962(3) and 1.878(3) Å, respectively. The average Fe–O bond length is 1.93 Å, which is similar to that of [FeIII(fla)(L1)]ClO4 (1.97 Å).17 The average Fe–N bond length is 2.16 Å, which is also close to those of [FeIII(fla)(L1)]ClO4 (2.15 Å)17 and [(6-Ph2TPAFeIII(fla))2(μ-O)](ClO4)2 (2.21 Å)22 but shorter than those of native Fe-2,4-QD (2.26 Å)5 and [FeIILH(fla)] (2.23 Å).21a Both the color and the charge balance indicate that the Fe ion is +3 state, as also proved also by BVS (bond valence sum) calculation (2.89).28

The eventually produced crystals of the enzyme-type dioxygenation reaction product sal complex [FeIIILOMe(sal)]·H2O (1′) during recrystallization of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) without N2 protection at room temperature are likely an indication that [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) very easily reacts with O2 even under air at room temperature, which is consistent with its high enzyme-type reactivity (see below).

Although suitable single crystals of [FeIILR(fla)] cannot be obtained, they are proposed to have a mononuclear structure bearing a distorted octahedral geometry, similar to that of the nonsubstituted derivative [FeIILH(fla)],21a as proved by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), ESI-MS, and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopic results that will be depicted below.

Spectroscopic and Redox Properties of the Complexes

Infrared Spectroscopy

The FT-IR spectra of both solid and ethanol solution state samples of the complexes were measured (Table 1, Supporting Information, Table S3 and Figure S1). As a typical example, the FT-IR spectra of 1 in both states are shown in Figure S1. The spectra between the ethanol solution and solid state samples of each complex are quite similar, suggesting that all complexes keep their monomeric structure [FeIILR(fla)] in solution, which coincides with ESI-MS and EPR results (see below). The ν(C=O) (C=O stretching vibration) of the bound carbonyl group of fla appears around 1550 cm–1 (ca. 50 cm–1 red-shifted compared with free flavonol (1602 cm–1)), which is close to those of reported fla complexes.13−16,26 In both states, each complex displays the asymmetric νas(COO–) and symmetric νs(COO–) stretching frequencies of the carboxylate group of LR around 1615 and 1420 cm–1, respectively. The difference Δν between νas(COO–) and νs(COO–) is in the range of 190–200 cm–1, which is a clear evidence to prove that the carboxylate group of ligand in all complexes has a monodentate coordination mode in both states.29

Table 1. Summary of Spectroscopic and CV Results for [FeIILR(fla)].

| [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) | [FeIILMe(fla)] (2) | [FeIILBr(fla)] (4) | [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR/cm–1 | ν(C=O) | 1545 | 1560 | 1550 | 1547 |

| νas(CO2)/νs(CO2) | 1611/1418 | 1620/1420 | 1610/1420 | 1612/1420 | |

| Δν/cm–1 | 193 | 200 | 190 | 192 | |

| UV–vis | 400 (9.59 × 103) | 399 (1.03 × 104) | 396 (1.16 × 104) | 394 (1.03 × 104) | |

| λ/nm (ε/M–1 cm–1) | 492 (2.53 × 103) | 491 (2.54 × 103) | 485 (2.77 × 103) | 484 (2.56 × 103) | |

| 271 (1.31 × 104) | 276 (1.23 × 104) | 287 (1.41 × 104) | 286 (1.25 × 104) | ||

| CV/V | Epa/Epc | –0.079/–0.149 | –0.050/–0.148 | +0.004/–0.102 | –0.009/–0.049 |

| (FeIII/II) | E1/2/ΔEp (mV) | –0.114/70 mV | –0.098/98 mV | –0.049/106 mV | –0.029/40 mV |

| ipc/ipa | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.15 | |

| (fla/fla•) | Epa/Epc | +0.151/+0.089 | +0.157/+0.096 | +0.250/+0.182 | +0.270/+0.192 |

| E1/2/ΔEp (mV) | +0.120/62 mV | +0.126/61 mV | +0.216/68 mV | +0.231/78 mV | |

| ipc/ipa | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.47 |

UV–Vis Spectroscopy

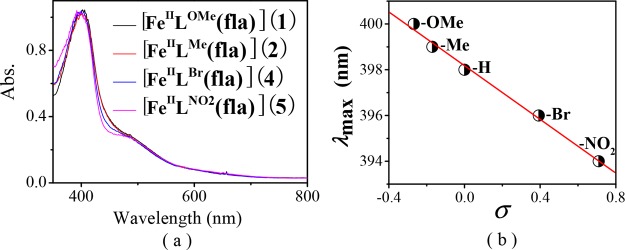

All complexes display an intense π → π* transition band of the coordinated fla30 in dimethylformamide (DMF) around 400 nm [400 nm (ε = 9.59 × 103 M–1 cm–1) for 1, 399 nm (ε = 1.03 × 104 M–1 cm–1) for 2, 396 nm (ε = 1.16 × 104 M–1 cm–1) for 4, and 394 nm (ε = 1.03 × 104 M–1 cm–1) for 5] (Figure 3a and Table 1). The λmax values are comparable with that of [FeIILH(fla)] (3) (398 nm)21a but blue-shifted 2–17 nm than those of models [FeII(fla)(L1)] (402 nm),17 [FeIII(4′-MeOfla)3] (411 nm),18 [FeIII(fla)(salen)] (407 nm),19 and [(6-Ph2TPA)FeII(fla)]ClO4 (415 nm),22 which could be explained by a combination effect of the carboxylate negative charge in the model ligands and a lower charge of the Fe(II) versus Fe(III) ion. Compared with free fla (458 nm for Me4Nfla22 and 465 nm for Kfla31), all λmax values are blue-shifted (ca. 60 nm), which are similar to those of the enzymatic5,10,12 and other synthetic model systems.13−27

Figure 3.

(a) Normalized electronic absorption spectra of the complexes [FeIILR(fla)] (ca. 0.1 mM in DMF). (b) Plot of λmax of [FeIILR(fla)] vs Hammett constants σ.

Besides, an order of −OMe (1) > −Me (2) > −H (3)21a > −Br (4) > −NO2 (5) was observed for the λmax values of fla in the complexes, which correlates linearly with the Hammett constants σ of the substituent groups of the ligands (R = 0.99) (Figure 3b). The stronger electron donating groups induce less blue shift (lower energy) of the λmax values of fla. These results demonstrate that the λmax values of fla are influenced by the substituent groups in the ligands through the benzoate, Fe(II), and “charge delocalization conduit”, as indicated by wine-red color in Scheme 2.7,23,24 All complexes also show an absorption shoulder around 485 nm, which is probably due to the charge transfer between Fe(II) and ligand and an intense absorption band around 280 nm from the supporting model ligand.

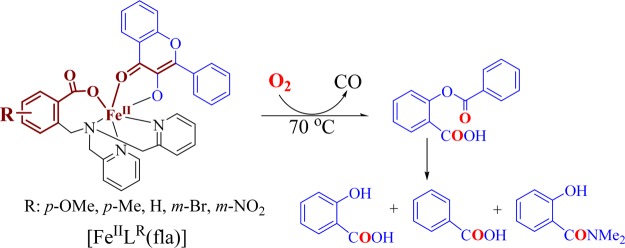

Scheme 2. Dioxygenation Reaction Products of [FeIILR(fla)] in DMF.

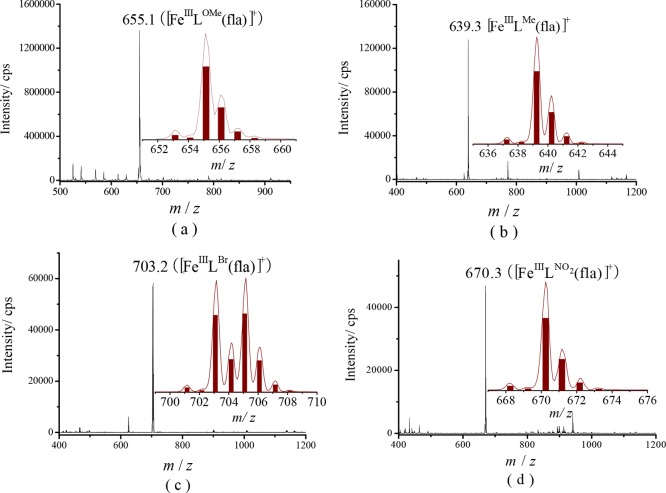

ESI-MS Spectroscopy

Because [FeIILR(fla)] was quite sensitive to air in solution, we observed only a peak cluster attributable to the oxidized species [FeIIILR(fla)]+ as a main peak at m/z (pos.) = 655.1 for 1, 639.3 for 2, 703.2 for 4, and 670.3 for 5 (Figure 4). Furthermore, no oxo- or fla-bridged dimeric species were observed.

Figure 4.

ESI-MS spectra of (a) [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1), (b) [FeIILMe(fla)] (2), (c) [FeIILBr(fla)] (4), and (d) [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5) in CH3OH (samples were prepared in a glove box but measured under air). Insets: Experimental and calculated isotope patterns of the species [FeIIILR(fla)]+ (line: experimental; column: calculated).

The very good agreement of the m/z values and the isotope distribution patterns of the peak clusters between the experimental and calculated data strongly suggest that [FeIILR(fla)] is easily auto-oxidized to [FeIIILR(fla)]+ by air but keep their monomer structures even after auto-oxidation in solution, which are in line with the results of the solution obtained using FT-IR and EPR (see below).

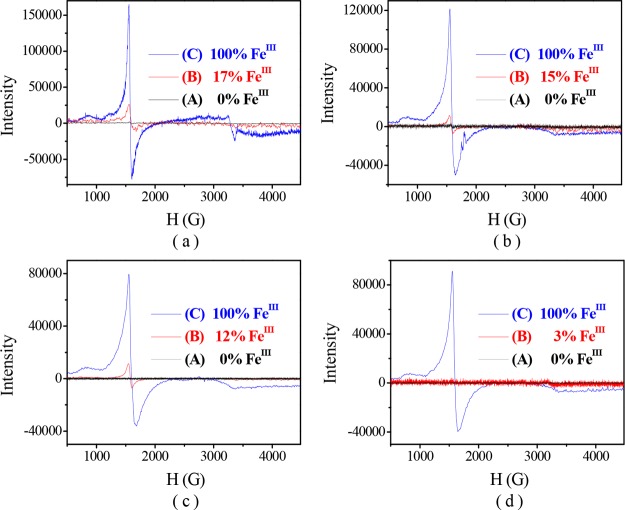

EPR Spectroscopy

The X-band EPR spectra of the complexes [FeIILR(fla)] were all silent under N2 at 100 K (Figure 5A, black line spectra), indicating that the valence of the iron ion is +2. The results resemble that of native Fe-2,4-QD.5,11,12

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of [FeIILR(fla)] (4 mM in 0.5 mL DMF) at 100 K. (a) [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1), (b) [FeIILMe(fla)] (2), (c) [FeIILBr(fla)] (4), and (d) [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5). Line (A): under N2, (B): exposed to air 2 min, and (C): after the reaction with O2.

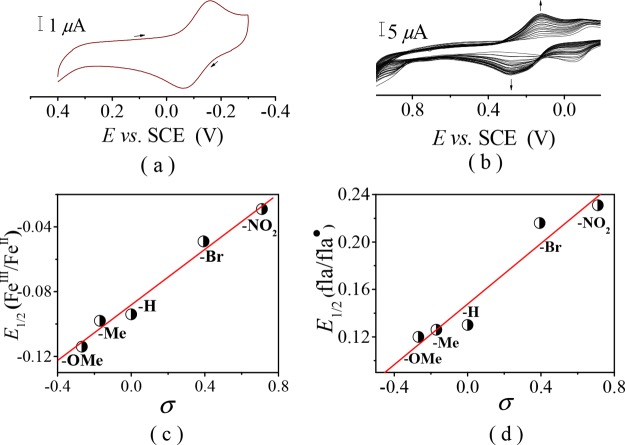

Cyclic Voltammetry

The results of cyclic voltammetry (CV) of [FeIILR(fla)] are summarized in Table 1. All redox potentials are reported versus SCE. The cyclic voltammogram of 1 is shown in Figure 6a as a typical example. All complexes display a quasireversible redox couple attributable to the one-electron redox process between FeII and FeIII with E1/2 = −0.114 V for [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1), −0.098 V for [FeIILMe(fla)] (2), −0.049 V for [FeIILBr(fla)] (4), and −0.029 V for [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5). The E1/2 values are comparable with that of [FeIILH(fla)] (3) (E1/2 = −0.094 V).21a An order of −OMe (1) < −Me (2) < −H (3)21a < −Br (4) < −NO2 (5) was observed for the E1/2 values of FeIII/II of the complexes. Besides, the values also correlate linearly with Hammett constants σ (R = 0.98) (Figure 6c). Obviously, the order can be explained by stronger electron-donating groups that induce higher electron density on the Fe(II) ion, thus leading to easier oxidation of the Fe(II) ion.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) in DMF at room temperature, (a) under N2, and (b) under a slightly aerobic condition. (c) Plot of E1/2 of FeIII/II vs σ. (d) Plot of E1/2 of fla/fla• vs σ.

Intriguingly, when the solution of [FeIILR(fla)] in DMF was made to contact with air slowly, a new quasireversible redox couple arose at E1/2 = +0.120 V for [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) (Figure 6b), +0.126 V for [FeIILMe(fla)] (2), +0.216 V for [FeIILBr(fla)] (4), and +0.231 V for [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5), then vanished slowly. Under anaerobic conditions, this redox couple was not observed. The redox couple emerged during the slow reaction with O2 can be assigned to the one-electron redox process between fla and flavonoxy radical fla•.21a The E1/2 values of fla/fla• redox couples are comparable with that of [FeIILH(fla)] (3) (E1/2 = +0.130 V)21a and exhibit remarkable differences among them. Besides, an order of −OMe (1) < −Me (2) < −H (3)21a < −Br (4) < −NO2 (5) was observed, and the E1/2 values are also correlate the linear relationship with Hammett constants σ (R = 0.92) (Figure 6d). The order implies that the bound fla is more readily oxidized in the order of −OMe (1) > −Me (2) > −H (3)21a > −Br (4) > −NO2 (5), as also confirmed by experiments (see below). The order of E1/2 of fla/fla• can be ascribed to the electronic nature of the substituent in the ligands, which could tune the redox potential of fla via tuning Lewis acidity of the Fe(II) ion and the electron density of fla. The stronger electron donating group, the weaker Lewis acidity of the Fe(II) ion, the weaker interaction between the Fe(II) ion and fla, the larger electron density on the fla moiety, the lower redox potentials of fla, and the easier oxidation of the bound fla.

Reaction with Dioxygen (Enzyme-Type Dioxygenation Reactivity)

Aerobic treatment of [FeIILR(fla)] in DMF at 70 °C for 8 h gave the primary products O-benzoylsalicylic acid (HObs) [m/z (pos.): 243.1 (M + H)+] (2.4–17%) and CO (over 64% for 1); then, HObs was hydrolyzed to produce salicylic acid [m/z (neg.): 137.1 (M – H)−] (81–97%) and benzoic acid [m/z (neg.): 121.1 (M – H)−] (67–82%) by a small amount of water presented in the solvent. The benzoic acid was further converted to an amide derivative, N,N-dimethylbenzamide [m/z (pos.): 150.1 (M + H)+] (10–16%) (Scheme 2) by the solvent DMF. These products were identified by LC–MS (Figure S2) and 1H NMR21a and summarized in Table S4. Conversions of the complexes are over 99%. As the products of the oxygenative ring opening reaction of the bound fla are similar to that catalyzed by the native enzyme, [FeIILR(fla)] display an enzyme-type reactivity.

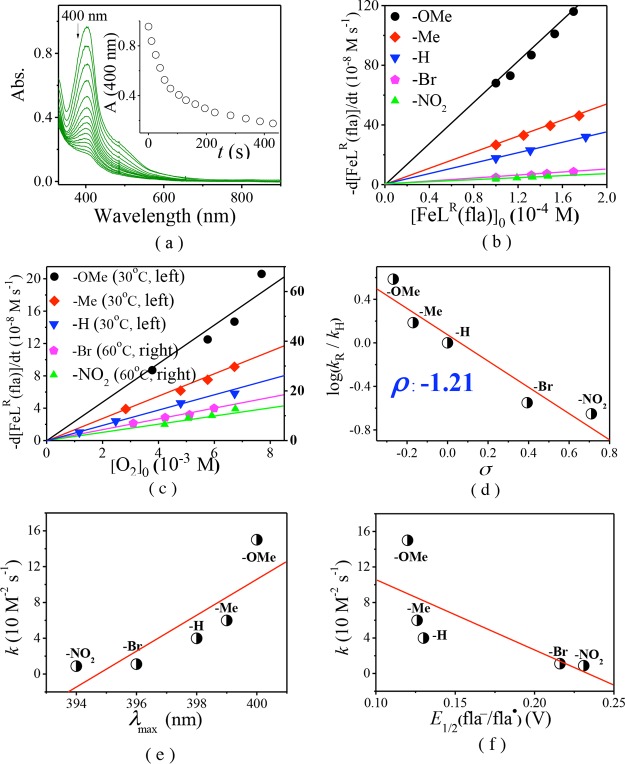

The dioxygenation reaction processes of the bound fla of [FeIILR(fla)] were followed by monitoring the absorption change ca. 400 nm band in DMF at 30–65 °C. The kinetic data, activation parameters, and reaction conditions are summarized in Tables 2 and S5. As a typical example, the time-dependent absorption spectral change and time trace during the dioxygenation reaction of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) are shown in Figure 7a. The initial reaction rate (vint, M s–1) was calculated from the initial straight line part of the plot of ΔA versus time (Figure 7a, inset). Figure 7b,c show that the vint correlates linearly with the initial concentrations of both [FeIILR(fla)]0 and [O2]0, thus, vint = k[FeIILR(fla)][O2]. The second-order rate constants k were calculated through dividing vint by both [FeIILR(fla)]0 and [O2]0.

Table 2. Dioxygenation Reaction Rate Constants and Activation Parameters of [FeIILR(fla)].

| complexes | T (°C) | 102 × k (M–1 s–1) | ΔH⧧ (kJ mol–1) | ΔS⧧ (J mol–1 K–1) | Ea (kJ mol–1) | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) | 50 | 150 ± 6 | 59 ± 4 | –64 ± 5 | 61 ± 6 | this work |

| [FeIILMe(fla)] (2) | 50 | 59.8 ± 0.7 | 62 ± 2 | –59 ± 2 | 64 ± 1 | this work |

| [FeIILH(fla)] (3) | 50 | 39.8 ± 0.1 | 65.92 | –51.81 | 68.60 | (21a) |

| [FeIILBr(fla)] (4) | 50 | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 67 ± 2 | –57 ± 3 | 69 ± 3 | this work |

| [FeIILNO2(fla)] (5) | 50 | 8.71 ± 0.10 | 67 ± 3 | –59 ± 3 | 70 ± 2 | this work |

| [FeII(fla)(L1)] | 80 | 58.6 | (17) | |||

| [FeIII(fla)(L1)]ClO4 | 80 | 44.8 | (17) | |||

| [FeIII(4′-MeOfla)3] | 100 | 80.0 | (18) | |||

| [FeIII(fla)(salen)] | 100 | 2.07 | (19) |

Figure 7.

Dioxygenation of [FeIILR(fla)] in DMF at 50 °C under O2. (a) Time-dependent change of the absorption spectra during the reaction of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) (1.0 × 10–4 M) with O2. Inset: Time trace of the absorption changes of 1 at 400 nm. Plots of vint vs (b) [FeIILR(fla)]0 and (c) [O2]0. (d) Hammett plot. Plots of k vs (e) λmax and (f) E1/2 of fla/fla•.

Therefore, the apparent second-order reaction rate constants k were calculated to be 8.71–150 × 10–2 M–1 s–1 at 50 °C (ΔH⧧ = 59–67 kJ mol–1, ΔS⧧ = −57 to −64 J mol–1 K–1) (Table 2, Supporting Information, Table S5 and Figure S3). Till now, only two examples of Fe(II)–fla complexes [FeII(fla)(L1)]17 and [FeIILH(fla)] (3) (39.8 × 10–2 M–1 s–1 at 50 °C and 179 × 10–2 M–1 s–1 at 70 °C)21a showing a dioxygenation reactivity have been reported. [FeII(fla)(L1)] is not structurally characterized and exhibits a relatively lower reactivity (only 58.6 × 10–2 M–1 s–1 even at 80 °C) and requires a higher temperature (65–80 °C).17 Compared to it, our model complexes [FeIILR(fla)] show a higher enzyme-type reactivity at a lower temperature (30–65 °C), which could be rationalized by the electron donation effect of the substituted benzoate group in the ligand. These results further demonstrate that our model complexes are good functional models of Fe-2,4-QD.

It is noteworthy that the dioxygenation reactivity of [FeIILR(fla)] shows a great difference and follows a substituent dependent ranking, −OMe (1) > −Me (2) > −H (3)21a > −Br (4) > −NO2 (5) (Figure 7, Table 2). The Hammett plot is linear, and the reaction constant is ρ = −1.21 (R = 0.89) (Figure 7d), implying that the electron donating groups quicken the reaction rates remarkably. The notable difference on the dioxygenation reactivity could be rationalized by the electronic nature of the substituent in the ligand, which could tune the reactivity through varying the electron density of fla via the benzoate, Fe(II) ion, and “charge delocalization conduit”. Namely, the stronger electron donation to the Fe(II) ion by the electron donating group via the benzoate group makes Lewis acidity of the Fe(II) ion weaker; thus, the electron density on the fla moiety in the complexes is larger and the redox potential of fla is lower, so the fla moiety can be oxidized easier by O2.

It should be pointed out that the order of dioxygenation reactivity looks to be in line with the order of λmax but inverse of the order of the redox potential E1/2 (fla/fla•) in the complexes, and they all correlate with Hammett constants σ linearly. Thus, the plots of k versus λmax and E1/2 (fla/fla•) gave an approximately linear correlation as shown in Figure 7e (R = 0.60) and 7f (R = 0.37). These results imply that the properties and the reactivities of [FeIILR(fla)] were affected by the electronic nature of the substituent in the ligand through the benzoate, Fe(II) ion, and “charge delocalization conduit”, and there are some relationships among them. The stronger the electron-donating group in the ligand, the lower the energy of the π → π* transition, the lower the redox potential of fla, and the higher the dioxygenation reactivity. As the first example of a set of structural and functional ES models of atypically coordinated 3His-1Glu active site mononuclear non-heme FeII-dependent Fe-2,4-QD, which focus on the electronic effects of the ligand on the enzyme-type reactivity; this study will supply critical insights into the role of Fe-2,4-QD and their property–reactivity relationship.

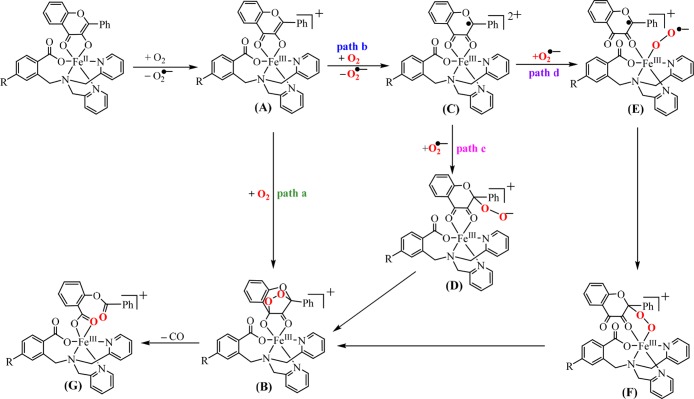

Dioxygenation Reaction Mechanism

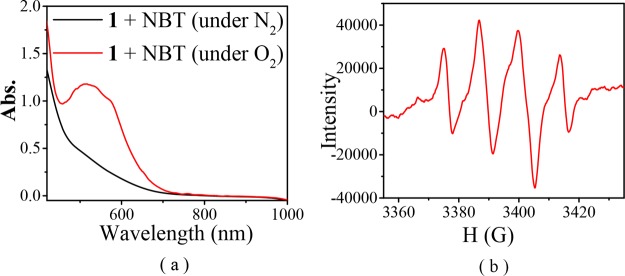

As mentioned above, when the ESI-MS spectra of [FeIILR(fla)] were recorded under the air, we only observed a peak cluster assignable to the oxidized species [FeIIILR(fla)]+ as a main peak (Table 1 and Figure 4). After the EPR samples of the [FeIILR(fla)] solution were exposed to air for 2 min at room temperature, we observed a typical mononuclear Fe(III) EPR signal around g = 4.3 (Figure 5B, red line spectra). Ca. 10% Fe(II) ions were converted to Fe(III) (according to the g = 4.3 signal height). All these results demonstrate that the Fe(II) ions in [FeIILR(fla)] were very easily oxidized to Fe(III) by O2 to form the Fe(III)–fla species [FeIIILR(fla)]+ (A) and superoxide radical O2•– first. The O2 was verified by NBT2+ (nitroblue tetrazolium) and DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide) methods. A new monoformazan (MF+, the reduction product of NBT2+) absorption band rose at 530 nm (Figure 8a, red line spectra for 1) when excess NBT2+ was added to a [FeIILR(fla)] solution (0.5 mM in DMF) under O2.32 Notably, when a solution of [FeIILR(fla)] (4 mM) and 2 equiv DMPO in DMF was exposed to air at room temperature, an EPR signal of DMPO–OOH appeared at g = 2.0069 (a = 12 G). As a typical example, the EPR spectrum of 1 with DMPO under air is shown in Figure 8b.

Figure 8.

(a) Spectral change of [FeIILOMe(fla)] (1) (0.5 mM in DMF) in the presence of excess NBT under O2 (red line) and N2 (black line) at room temperature. (b) EPR spectrum of 1 in the presence of 2 equiv DMPO under air at room temperature.

After the dioxygenation reaction, a peak cluster assignable to the enzyme-type reaction products salicylate (sal) or benzoate (ben) complexes was observed at m/z (pos.) = 556.4 ([FeIIILOMe(sal)]H+) for 1, 645.1 ([FeIIILMe(ben)2]H+) for 2, 604.2 ([FeIIILBr(sal)]H+) for 4, and 571.1 ([FeIIILNO2(sal)]H+) for 5 in the ESI-MS spectra. On the other hand, EPR signals assignable to typical mononuclear Fe(III) appeared around g = 7.66, 4.27, and 2.06 (Figure 5C, blue line spectra).

In the light of all experimental results, a possible dioxygenation reaction mechanism was proposed and shown in Scheme 3. First, [FeIILR(fla)] and one O2 molecule react quickly to form [FeIIILR(fla)]+ (A) and O2•–. Then, there are two possible pathways from A in the next step. One pathway a: direct reaction of intermediate A with another O2 molecule to form an endoperoxide intermediate [FeIIIL(fla–O2)]+ (B) slowly. Another pathway b: the reaction of A with another O2 molecule through an electron transfer process from fla to O2 to produce flavonoxy radical species [FeIIILR(fla•)]2+ (C) and another O2 slowly. There are also two possible pathways from C in the next step. One pathway c: the O2•– attacks the fla• moiety in C to generate an alkylperoxide adduct D. Then, an intramolecular cyclization reaction takes place and an endoperoxide intermediate B is formed. Another pathway d: a FeIII-superoxide adduct E is formed by the coordination of O2 to FeIII in C. Then, a Fe(III)–alkylperoxide intermediate F is produced by the intramolecular radical coupling. From F the same endoperoxide intermediate B can also be generated. Once B is formed, the dioxygenated products complex [FeIIILR(Obs)]+ (G) is engendered by releasing CO. No direct evidence is available to conclude the accurate reaction pathways, path a or path b and path c or path d at this moment. However, the observed redox couple of fla/fla•, the reduction of NBT2+, and DMPO–OOH EPR signals mentioned above may support the reaction pathway b and pathway d, which involves a flavonoxy radical species, intermediate C and FeIII–OO•– species E, respectively. Nevertheless, the possibility of pathway a also could not be excluded. The reaction mechanism of all the complexes are the same and also close to those of the nonsubstituted derivative [FeIILH(fla)] (3)21a and Fe-2,4-QD.5,11,12

Scheme 3. Proposed Reaction Mechanism of [FeIILR(fla)] toward Dioxygen.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully synthesized and characterized a set of structural and functional ES models of Fe-2,4-QD, [FeIILR(fla)] based on p/m-R-substituted carboxylate-containing ligands (R: p-OMe (1), p-Me (2), m-Br (4), and m-NO2 (5)). The model complexes exhibit a relatively high enzyme-type dioxygenation reactivity at low temperature. The dioxygenation reactions display first-order dependence versus both initial concentrations of the complexes and dioxygen. In addition, the reactivity is varied notably with the substituent group R and follows the ranking of −OMe (1) > −Me (2) > −H (3)21a > −Br (4) > −NO2 (5). The Hammett plot shows a linear relationship (ρ = −1.21), and electron donating groups progress the reaction rates. The electronic nature of the substituent in the ligand tunes the properties and the reactivity of the complexes remarkably, and there are some correlations between k with the λmax of the π → π* transition or the redox potential of the fla moiety in the complexes, respectively. That is to say, the key role of the substituent group is to tune Lewis acidity of Fe(II), the electron density, and the redox potential of fla by electron donation via benzoate, Fe(II) ion, and “charge delocalization conduit”. As far as we know, this is the first example of a set of the ES models of Fe-2,4-QD, which faithfully reproduce the atypically coordinated 3His-1Glu coordination environment of the mononuclear non-heme FeII-dependent Fe-2,4-QD active site structurally and functionally and will provide crucial insights into the role of Fe-2,4-QD and the active site structure–function relationship of different active site MNHEs.

Experimental Section

General and Physical Methods

The methods are the same as the methods reported previously.23 EPR instrument parameters for DMPO–OOH detection are microwave frequency 9.531841 GHz, modulation frequency 100 kHz, modulation amplitude 3 G, microwave power 1.91 mW, number of scans 5, time constant 1310.72 ms, conversion time 80 ms, and sweep time 81.92 s.

X-ray Crystallography

A single crystal of 1′ was mounted on a glass capillary. Data of X-ray diffraction were collected by a Bruker Smart APEX II CCD single-crystal diffractometer using Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) to 2θmax of 50.0° at 293 K. The crystallographic calculation was performed by a direct method using SHELXL 2014.33 All non-hydrogen atoms and hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically and isotropically, respectively. The occupy factor of solvent water O(7) and O(8) is 0.5, and the hydrogen atoms of the solvent are not found. Atomic coordinates, thermal parameters, and intramolecular bond lengths and angles are given in the Supporting Information (CIF file format).

Kinetic Measurements

The experiments procedures were similar to the procedures reported previously.23 Reaction condition details and results are summarized in Table S5.

Reaction Products Analysis

The reaction product analysis methods are the same as the methods reported previously.21a

Synthesis of the Model Complexes [FeIILR(fla)]

Ligands LRH (R: p-OMe, p-Me, m-Br, m-NO2) were synthesized based on the reported methods.23 Complexes were synthesized using a similar method. A solution of LRH (0.1 mmol in 1.0 mL dry CH3OH) was added dropwise to a solution of FeII(OAc)2 (17.4 mg, 0.1 mmol, in 2.0 mL dry CH3OH) under a nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature. After stirring for 30 min, a solution of flavonol (23.8 mg, 0.1 mmol, in 1:1 CH3OH/CH2Cl2) was added dropwise to the above solution with strong stirring. The mixture was stirred for 1 day under N2. The [FeIILR(fla)] was isolated as dark red powder by filtration.

[FeIILOMe(fla)] (1)

52.4 mg, 80%. ESI-MS m/z (pos.): 655.1 ([FeIIILOMe(fla)]+). Anal. Calcd for C36H29FeN3O6 (655.48): C, 65.97; H, 4.46; N, 6.41. Found: C, 65.83; H, 4.61; N, 6.29. FT-IR (solid sample: KBr, cm–1): 3400 (m), 1611 (s), 1545 (s), 1491 (s), 1458 (w), 1418 (s), 1383 (w), 1213 (s), 760 (s). FT-IR (solution sample: in ethanol, cm–1): 3352 (m), 1607 (s), 1541 (s), 1488 (s), 1458 (w), 1417 (s), 1381 (w), 1212 (s), 760 (s).

[FeIIILOMe(sal)]·H2O (1′)

12.0 mg, 21%. ESI-MS m/z (pos.): 555.4 ([FeIIILOMe(sal)]H+). Anal. Calcd for C28H26FeN3O7 (572.37): C, 58.76; H, 4.58; N, 7.34. Found: C, 58.63; H, 4.74; N, 7.25. FT-IR (solid sample: KBr, cm–1): 3235 (m), 3075 (m), 2925 (m), 1660 (s), 1596 (s), 1452 (s), 1385 (m), 1224 (s), 756 (s). FT-IR (solution sample: in ethanol, cm–1): 3232 (m), 3075 (m), 2929 (m), 1662 (s), 1598 (s), 1451 (s), 1383 (w), 1226 (s), 757 (s).

[FeIILMe(fla)] (2)

55.6 mg, 87%. ESI-MS m/z (pos.): 639.1 ([FeIIILMe(fla)]+). Anal. Calcd for C36H29FeN3O5 (639.48): C, 67.62; H, 4.57; N, 6.57. Found: C, 67.43; H, 4.71; N, 6.42. FT-IR (solid sample: KBr, cm–1): 3400 (m), 1620 (s), 1560 (s), 1490 (s), 1440 (w), 1420 (s), 1380 (w), 1120 (s), 603 (s). FT-IR (solution sample: in ethanol, cm–1): 3381 (m), 1606 (s), 1540 (s), 1488 (s), 1439 (w), 1417 (s), 1354 (w), 1211 (s), 761 (s).

[FeIILBr(fla)] (4)

57.6 mg, 82%. ESI-MS m/z (pos.): 703.0 ([FeIIILBr(fla)]+). Anal. Calcd for C35H26BrFeN3O5 (704.36): C, 59.68; H, 3.72; N, 5.97. Found: C, 59.51; H, 3.88; N, 6.05. FT-IR (solid sample: KBr, cm–1): 3420 (m), 1610 (s), 1550 (s), 1490 (s), 1420 (s), 1210 (s), 756 (s). FT-IR (solution sample: in ethanol, cm–1): 3324 (m), 1614 (w), 1542 (s), 1489 (s), 1417 (s), 1211 (s), 880 (s).

[FeIILNO2(fla)] (5)

50.3 mg, 75%. ESI-MS m/z (pos.): 670.1 ([FeIIILNO2(fla)]+). Anal. Calcd for C35H26FeN4O7 (670.46): C, 62.70; H, 3.91; N, 8.36. Found: C, 62.56; H, 4.07; N, 8.19. FT-IR (solid sample: KBr, cm–1): 3400 (m), 1612 (s), 1547 (s), 1491 (s), 1420 (s), 1215 (s), 758 (s). FT-IR (solution sample: in ethanol, cm–1): 3335 (m), 1612 (s), 1541 (s), 1488 (s), 1415 (s), 1211 (s), 746 (s).

Acknowledgments

We thank a lot the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 21471025).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00927.

The FT-IR data, reaction product analysis data, kinetic data, FT-IR spectra, LC–MS spectra, Eyring plot, and crystallographic information (CIF) CCDC 1540620 for 1′ are shown (PDF)

Author Present Address

Department of Chemistry, XinXiang Medical University, Xinxiang 453003, China (Q.-Q.H.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Que L. Jr.; Ho R. Y. N. Dioxygen Activation by Enzymes with Mononuclear Non-heme Iron Active Sites. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2607–2624. 10.1021/cr960039f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straganz G.; Brecker L.; Weber H.-J.; Steiner W.; Ribbons D. W. A Novel β-Diketone-Cleaving Enzyme from Acinetobacter Johnsonii: Acetylacetone 2,3-Oxygenase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 232–236. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy J. G.; Bailey L. J.; Bitto E.; Bingman C. A.; Aceti D. J.; Fox B. G.; Phillips G. N. Jr. Structure and Mechanism of Mouse Cysteine Dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 3084–3089. 10.1073/pnas.0509262103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju T.; Goldsmith R. B.; Chai S. C.; Maroney M. J.; Pochapsky S. S.; Pochapsky T. C. One Protein, Two Enzymes Revisited: A Structural Entropy Switch Interconverts the Two Isoforms of Acireductone Dioxygenase. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 393, 823–834. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal B.; Madan L. L.; Betz S. F.; Kossiakoff A. A. The Crystal Structure of A Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase from Bacillus Subtilis Suggests Modulation of Enzyme Activity by A Change in the Metal Ion at the Active Site(s). Biochemistry 2005, 44, 193–201. 10.1021/bi0484421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenweber E.The Flavonoids: Advances in Research; Harborne J. B., Mabry T. J., Eds.; Chapman&Hall: London, 1982; p 57. [Google Scholar]

- Fusetti F.; Schröter K. H.; Steiner R. A.; van Noort P. I.; Pijning T.; Rozeboom H. J.; Kalk K. H.; Egmond M. R.; Dijkstra B. W. Crystal Structure of the Copper-Containing Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase from Aspergillus Japonicas. Structure 2002, 10, 259–268. 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00704-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T.; Simpson F. J. Quercetinase, A Dioxygenase Containing Copper. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971, 43, 1–5. 10.1016/s0006-291x(71)80076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund H.-K.; Breuer J.; Lingens F.; Hüttermann J.; Kappl R.; Fetzner S. Flavonol 2,4-Dioxygenase from Aspergillus Niger DSM 821, A Type 2 CuII-Containing Glycoprotein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 263, 871–878. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner R. A.; Kalk K. H.; Dijkstra B. W. Anaerobic Enzyme•Substrate Structures Provide Insight Into the Reaction Mechanism of the Copper-Dependent Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 16625–16630. 10.1073/pnas.262506299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowater L.; Fairhurst S. A.; Just V. J.; Bornemann S. Bacillus Subtilis YxaG Is A Novel Fe-Containing Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. FEBS Lett. 2004, 557, 45–48. 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney B. M.; Schaab M. R.; LoBrutto R.; Francisco W. A. Evidence for A New Metal in A Known Active Site: Purification and Characterization of An Iron-Containing Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase from Bacillus Subtilis. Protein Expression Purif. 2004, 35, 131–141. 10.1016/j.pep.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaizer J.; Balogh-Hergovich É.; Czaun M.; Csay T.; Speier G. Redox and Nonredox Metal Assisted Model Systems with Relevance to Flavonol and 3-Hydroxyquinolin-4(1H)-one 2,4-Dioxygenase. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 2222–2233. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pap J. S.; Kaizer J.; Speier G. Model Systems for the CO-Releasing Flavonol 2,4-Dioxygenase Enzyme. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 781–793. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaizer J.; Pap J. S.; Speier G.. Copper Dioxygenases. In Copper-Oxygen Chemistry; Karlin K. D., Shinobu I., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, 2011; pp 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- a Solomon E. I.; Heppner D. E.; Johnston E. M.; Ginsbach J. W.; Cirera J.; Qayyum M.; Kieber-Emmons M. T.; Kjaergaard C. H.; Hadt R. G.; Tian L. Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3659–3853. 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Allpress C. J.; Berreau L. M. Oxidative Aliphatic Carbon–Carbon Bond Cleavage Reactions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 3005–3029. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Fetzner S. Ring-Cleaving Dioxygenases with A Cupin Fold. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2505–2514. 10.1128/aem.07651-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Quist D. A.; Diaz D. E.; Liu J. J.; Karlin K. D. Activation of Dioxygen by Copper Metalloproteins and Insights from Model Complexes. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2017, 22, 253–288. 10.1007/s00775-016-1415-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Fiedler A. T.; Fischer A. A. Oxygen Activation by Mononuclear Mn, Co, and Ni Centers in Biology and Synthetic Complexes. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2017, 22, 407–424. 10.1007/s00775-016-1402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuz A.; Giorgi M.; Speier G.; Kaizer J. Structural and Functional Comparison of Manganese-, Iron-, Cobalt-, Nickel-, and Copper-Containing Biomimic Quercetinase Models. Polyhedron 2013, 63, 41–49. 10.1016/j.poly.2013.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaizer J.; Baráth G.; Pap J.; Speier G.; Giorgi M.; Réglier M. Manganese and Iron Flavonolates as Flavonol 2,4-Dioxygenase Mimics. Chem. Commun. 2007, 5235–5237. 10.1039/B711864C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baráth G.; Kaizer J.; Speier G.; Párkányi L.; Kuzmann E.; Vértes A. One Metal–Two Pathways to the Carboxylate-Enhanced, Iron-Containing Quercetinase Mimics. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3630–3632. 10.1039/B903224J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Amrani F. B. A.; Perelló L.; Real J. A.; González-Alvarez M.; Alzuet G.; Borrás J.; García-Granda S.; Montejo-Bernardo J. Oxidative DNA Cleavage Induced by An Iron(III) Flavonoid Complex: Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Characterization of Chlorobis(flavonolato)(methanol) Iron(III) Complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006, 100, 1208–1218. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sun Y.-J.; Huang Q.-Q.; Tano T.; Itoh S. Flavonolate Complexes of MII (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn). Structural and Functional Models for the ES (Enzyme–Substrate) Complex of Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10936–10948. 10.1021/ic400972k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sun Y.-J.; Huang Q.-Q.; Li P.; Zhang J.-J. Catalytic Dioxygenation of Flavonol by MII-Complexes (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn)—Mimicking the MII-Substituted Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 13926–13938. 10.1039/c5dt01760b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubel K.; Rudzka K.; Arif A. M.; Klotz K. L.; Halfen J. A.; Berreau L. M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Ligand Exchange Reactivity of A Series of First Row Divalent Metal 3-Hydroxyflavonolate Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 82–96. 10.1021/ic901405h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-J.; Huang Q.-Q.; Zhang J.-J. Series of Structural and Functional Models for the ES (Enzyme–Substrate) Complex of the Co(II)-Containing Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2932–2942. 10.1021/ic402695c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-J.; Huang Q.-Q.; Zhang J.-J. A Series of NiII-Flavonolate Complexes as Structural and Functional ES (Enzyme-Substrate) Models of the NiII-Containing Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 6480–6489. 10.1039/c3dt53349b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-J.; Li P.; Huang Q.-Q.; Zhang J.-J.; Itoh S. Dioxygenation of Flavonol Catalyzed by Copper(II) Complexes Supported by Carboxylate-Containing Ligands: Structural and Functional Models of Quercetin 2,4-Dioxygenase. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 1845–1854. 10.1002/ejic.201601371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Balogh-Hergovich É.; Kaizer J.; Speier G.; Argay G.; Párkányi L. Kinetic Studies on the Copper(II)-Mediated Oxygenolysis of the Flavonolate Ligand. Crystal Structures of [Cu(fla)2] (fla = Flavonolate) and [Cu(O-bs)2(py)3] (O-bs = O-Benzoylsalicylate). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1999, 3847–3854. 10.1039/A905684J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Balogh-Hergovich É.; Kaizer J.; Pap J.; Speier G.; Huttner G.; Zsolnai L. Copper-Mediated Oxygenolysis of Flavonols via Endoperoxide and Dioxetan Intermediates; Synthesis and Oxygenation of [CuII(Phen)2(Fla)]ClO4 and [CuII(L)(Fla)2] [FlaH = Flavonol; L = 1,10-Phenanthroline (Phen), 2,2′-Bipyridine (Bpy), N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA)] Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 2287–2295. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Balogh-Hergovich É.; Kaizer J.; Speier G.; Fülöp V.; Párkányi L. Quercetin 2,3-Dioxygenase Mimicking Ring Cleavage of the Flavonolate Ligand Assisted by Copper. Synthesis and Characterization of Copper(I) Complexes [Cu(PPh3)2(fla)] (fla = Flavonolate) and [Cu(PPh3)2(O-bs)] (O-bs = O-Benzoylsalicylate). Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 3787–3795. 10.1021/ic990175d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barhács L.; Kaizer J.; Speier G. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Stoichiometric Oxygenation of the Ionic Zinc(II) Flavonolate Complex [Zn(fla)(idpa)]ClO4 (fla = Flavonolate; idpa = 3,3′-Iminobis(N,N-dimethylpropylamine)). J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2001, 172, 117–125. 10.1016/s1381-1169(01)00130-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brydon P.; Szymczak P.; Leonyuk L.; Shvanskaya L. Bond-Valence Analysis of Charge Distribution in the Spin Ladders of [M2Cu2O3]m[CuO2]n-Type Cuprates with m = n = 1. Philos. Mag. Lett. 1999, 79, 383–387. 10.1080/095008399177237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon G. B.; Phillips R. J. Relationships between the Carbon-Oxygen Stretching Frequencies of Carboxylato Complexes and the Type of Carboxylate Coordination. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1980, 33, 227–250. 10.1016/s0010-8545(00)80455-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jurd L.; Geissman T. A. Absorption Spectra of Metal Complexes of Flavonoid Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1956, 21, 1395–1401. 10.1021/jo01118a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Barhács L.; Kaizer J.; Speier G. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Oxygenation of Potassium Flavonolate. Evidence for an Electron Transfer Mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 3449–3452. 10.1021/jo991926w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pap J. S.; Matuz A.; Baráth G.; Kripli B.; Giorgi M.; Speier G.; Kaizer J. Bio-Inspired Flavonol and Quinolone Dioxygenation by A Non-Heme Iron Catalyst Modeling the Action of Flavonol and 3-Hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone 2,4-Dioxygenases. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 108, 15–21. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielski B. H. J.; Shiue G. G.; Bajuk S. Reduction of Nitro Blue Tetrazolium by CO2− and O2− Radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84, 830–833. 10.1021/j100445a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Program for the Solution of Crystal Structures; University of Gottingen: Gottingen, Germany, 2014.; Program for the Refinement of Crystal Structures; University of Gottingen: Gottingen, Germany, 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.