Abstract

Objective(s)

Serious mental illnesses, such as bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, are closely associated with involuntary admission. Many studies have focused on involuntary admission in people with schizophrenia, but little is known about the factors associated with involuntary admission in Chinese patients with bipolar disorders. This study aimed to investigate socio-demographic and clinical factors associated with involuntary admission in Chinese patients with bipolar disorders.

Methods

In this multi-center cross-sectional survey in China, a total of 155 newly admitted patients with bipolar disorders were consecutively recruited from 16 psychiatric institutions from 15 March to 14 April, 2013. Patients’ socio-demographic and clinical data were collected from their medical records. The Modified Overt Aggression Scale and the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire were used to measure patients’ level of aggression and insight of current psychiatric illness.

Results

The prevalence of involuntary admission was 52% in this sample of Chinese inpatients with bipolar disorders. In multiple logistic regression, a high level of aggression (odds ratio (OR) = 2.48), diagnosis of manic episode (OR = 3.65), poor insight (OR = 7.52), and a low level of education (OR = 3.13) were significantly associated with involuntary admission.

Conclusion

Manic episode, aggressive behavior, and poor insight were the significant contributing factors to involuntary admission in Chinese patients with bipolar disorders.

Keywords: Involuntary admission, Bipolar disorder, Aggressive behavior

Introduction

Involuntary admission is a common and controversial issue in psychiatric clinical practice and may raise clinical, ethical, and legal concerns (Hoffmann et al., 2017). It is an act that may violate basic human rights, may have a potential negative effect on patients’ satisfaction and is receiving increased attention in many countries (Iversen, Hoyer & Sexton, 2007; Wang et al., 2015). In Europe, a multicenter prospective study (the “EUNOMIA project”) with 13 psychiatric institutions in 12 European countries has been carried out to investigate involuntary treatment and its influencing factor and outcomes (Giacco et al., 2012; Kalisova et al., 2014; Nawka et al., 2013). The study found that the percentages of psychiatric patients receiving involuntary treatment ranged from 21% to 59%, and aggression against others was the most frequent reason for patients being prescribed involuntary treatment. In another study with a large sample of 2,030 involuntary hospitalized psychiatric patients in 10 European countries, 770 patients (38%) were prescribed coercive measures (Raboch et al., 2010). In Switzerland, the involuntary admission rate among all inpatients aged 18–70 (N = 9,698) was 24.8% in 2007 (Lay, Nordt & Rössler, 2011). In a multi-center study of patients who were acutely admitted to psychiatric wards in Norway, 44% were involuntary hospitalized (Hustoft et al., 2013). By contrast, in some countries, such as Italy, the percentage of involuntary patients among all patients in general psychiatric wards does not exceed 9% (De Girolamo et al., 2008). The above data indicate that involuntary admission is common in psychiatric clinical practice, however, the rates vary widely across countries.

In China, some improvements in the protection of psychiatric patients’ rights have been achieved. For example, a multi-center study in 2003 showed that involuntary hospitalization rate in Chinese psychiatric institutions was as high as 82.5% (Pan & Xie, 2003), whereas, 10 years later, the rate of involuntary admission decreased to 42.0–53.1% (Gou et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015). However, compared to the above-mentioned rates of involuntary admission in Europe, these is still much space for reducing the rate of involuntary admission in China.

Involuntary treatment is associated with many negative clinical outcomes. Obviously, involuntary patients are less likely to adhere to treatment (Craw & Compton, 2006). Compared to voluntary patients, involuntary patients have higher suicide rates and lower levels of social functioning (Kallert, Glockner & Schutzwohl, 2008), which may raise medical disputes and will lead to poor therapeutic relationship (Sheehan & Burns, 2011). In addition, a commonly perceived concern is the poor therapeutic relationship between patients and clinicians and poor treatment satisfaction resulted from involuntary hospitalization (Sheehan & Burns, 2011; Katsakou et al., 2010; Georgieva et al., 2017).

Involuntary admission in psychiatric patients is affected by many factors, including demographics, symptoms, and the legal system of the country (Fiorillo et al., 2011). Many studies have shown that high level may reduce the risk of involuntary admission (Hustoft et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015). Aggressive behavior and positive symptoms are associated with a high likelihood of involuntary admission in Western countries (Fiorillo et al., 2012; Hustoft et al., 2013; Van Der Post et al., 2009). In our previous study, poor social functioning and insight were also found to be related to psychiatric patients involuntary admission (Gou et al., 2014).

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses associated with involuntary admission. In Germany, bipolar disorders and schizophrenia account for 18.9% and 30.5% of the total number of involuntary admissions, respectively (Hoffmann et al., 2017). In our previous study, we reported that male gender, history of hospitalization, aggressive behavior, and diagnosis of schizophrenia or related disorders were the risk factors of involuntary admission in China (Zhou et al., 2015). In Ireland, a study with samples of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders found that increased age was associated with involuntary admission in patients with bipolar disorders but not in patients with schizophrenia (Kelly et al., 2018). Nevertheless, very few studies have specifically investigated factors associated with involuntary admission of patients with bipolar disorders. Given the different clinical features between bipolar disorders and schizophrenia, we speculate that factors affecting involuntary admission in patients with bipolar disorders might be quite different from those in patients with schizophrenia.

Anyway, under any circumstance, involuntary admission should be minimized as much as possible to maximize patients’ benefits (Fiorillo et al., 2012). In the Article 30 of the China Mental Health Law (Zhao & Dawson, 2014), the criteria for involuntary admission are “psychiatric admissions and treatment should be determined solely by the patient, unless he or she is evaluated as having a severe mental disorder and has self-harmed or is at risk of self-harming behavior or has harmed others or is at risk of harming others” (Zhou et al., 2015). Thus, we hypothesized that poor of insight, aggression, suicidal history, and some clinical characteristics of bipolar disorders (e.g., manic or depressive episodes) may be related to involuntary admission among patients with bipolar disorders. As there are many differences in healthcare systems, cultural environments and legal systems between China and Western countries (Zhou et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017), it would be interesting to investigate factors associated with involuntary admission in patients with serious mental illnesses in China. The present study was carried out to examine factors associated with involuntary admission in Chinese patients with bipolar disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study sites and patients

This study was a multi-center cross-sectional survey, which was sponsored by the Chinese Psychiatric Association. The data were collected from 16 representative psychiatric institutions in China between 15 March and 14 April 2013. Details of these facilities have been described in a previously published paper (Zhou et al., 2015). In brief, all patients with bipolar disorders who were admitted to the 16 participating facilities during an index month were consecutively invited to participate in the study. Patients who were aged 18 years or older and met ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorders were deemed eligible for this study. We excluded patients with history of brain trauma and current substance use disorders.

The informed consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians. The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Board of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University in Hunan Province (2013068) and by the ethics committees of all participating institutions.

Instruments and evaluation

A standardized form was designed to collect data from inpatients’ medical records, including socio-demographics (e.g., age, gender, residence place, education, and employment status) and clinical characteristics (e.g., insight, suicide history, age of onset, and length of illness) (Gou et al., 2014). Following ICD-10 criteria, the diagnosis of bipolar disorders was categorized into two groups: manic and depressive episodes.

The Chinese Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) (He et al., 2017; Yudofsky et al., 1986) was used to assess aggressive and violent behavior in the week before admission. Information was collected directly from patients, their family members, and medical records (Zhou et al., 2015). The Chinese MOAS has been proved to be reliable and valid for assessing aggressive and violent behavior of psychiatric patients (Xie & Zheng, 2001). The MOAS includes four subdomains of aggression: verbal, against objects, against self, and physical-interpersonal. The score of each subdomain ranges from 0 to 4 with a higher score indicating more severe aggressive behavior. The total MOAS score was calculated according to the following formula: 1 × verbal score + 2 × against objects score + 3 × against self score + 4 × physical-interpersonal score. The total weighted score for each evaluation ranges from 0 (no aggression) to 40 (maximum grade of aggression). Based on previous study (Zhou et al., 2016), the MOAS total score 5 or higher was assigned high aggressive, 4 of lower was assigned low aggressive.

The Chinese Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire (ITAQ) was used to assess patients’ insight (McEvoy et al., 1989; Liu et al., 1995). The ITAQ comprises of 11 items, and all items were rated on a 3-point scale from 0 to 2. The total score ranges from 0 to 22 with a higher score indicating a better insight.

In China, most patient admissions were decided by their family members or the treating clinician. Thus, on the basis of our previous study (Zhou et al., 2015), we determined the type of admission according to patients’ self-report, by asking: “Did you voluntarily go to hospital?” and “Were you forced by your family or others?” Patients who denied the first question or endorsed the second question were classified as having involuntary admission. The patients were interviewed within one week before discharged from hospital. Data on scores of MOAS and ITAQ were directly copied from the medical records.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted with SPSS 19.0 for Windows statistical package. Independent sample t-test and Chi-square test were used to compare the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who were admitted voluntarily and involuntarily as appropriate. For further analysis, we used the median split approach to dichotomize the ITAQ total score into poor insight (ITAQ ≤ 17) and good insight (ITAQ > 17). Multiple binary logistic regression model (Backward: LR) was used to identify factors associated with involuntary admission. The associations between factors and involuntary admission were quantified with odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample and prevalence of involuntary admission

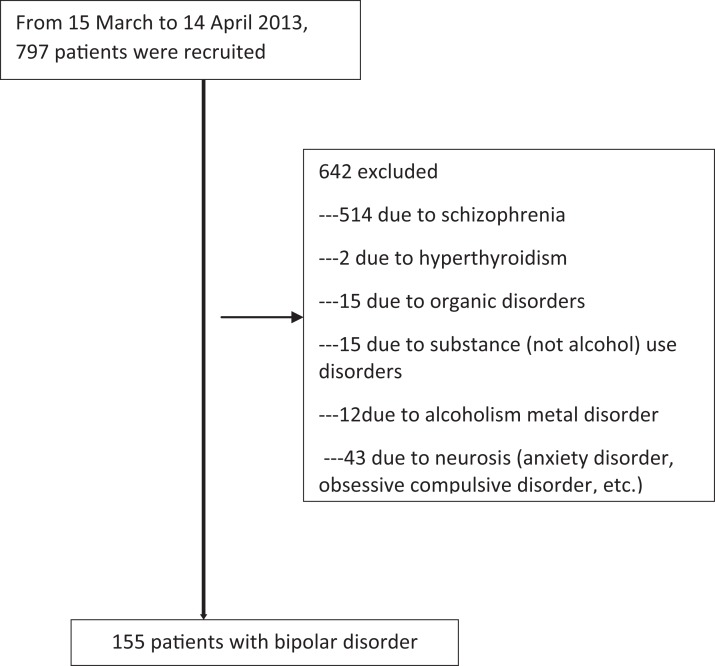

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the patients’ recruitment process. In the index month, a total of 155 patients with bipolar disorders successfully completed the study, consisting of 74 (47.7%) voluntary and 81 (52.3%) involuntary admissions. Among these participants, 60 (38.7%) were males, 81 (52.3%) were in a manic episode, and 57 (36.8%) were rated as having no insight.

Figure 1. Flow-chart showing sample recruitment.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients

As shown in Table 1, compared to voluntarily admitted patients, involuntarily patients were more likely to have low level of education (χ2 = 3.49, df = 1, p = 0.06), be unemployed (χ2 = 48.8, df = 1, p < 0.001), have longer duration of illness (t = −2.5, df = 133, p = 0.050), have a past history of hospitalization (χ2 = 4.6, df = 1, p = 0.030), have manic episode (χ2 = 11.8, df = 1, p = 0.001), have poor insight (χ2 = 14.2, df = 2, p = 0.001), and have a higher aggression score (τ = −3.0, df = 153, p < 0.001) and a lower ITAQ score (τ = 5.8, df = 153, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Variables | Voluntary (N = 74) | Involuntary (N = 81) | Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | χ2 | df | p | |

| Gender | 0.05 | 1 | 0.83 | ||||

| Male | 28 | 37.8 | 32 | 39.5 | |||

| Female | 46 | 62.2 | 49 | 60.5 | |||

| Employ | 48.8 | 1 | <0.001 | ||||

| Employed | 53 | 71.6 | 13 | 16.0 | |||

| Unemployed | 21 | 28.4 | 68 | 84.0 | |||

| Marital status | 0.41 | 1 | 0.52 | ||||

| Unmarried | 44 | 59.5 | 44 | 54.3 | |||

| Married | 30 | 40.5 | 37 | 45.7 | |||

| Education | 3.49 | 1 | 0.06 | ||||

| Low (≤9 years) | 30 | 40.5 | 45 | 55.6 | |||

| High (>9 years) | 44 | 59.5 | 36 | 44.4 | |||

| Residence | 0.1 | 1 | 0.71 | ||||

| Rural | 28 | 37.8 | 33 | 40.7 | |||

| Urban | 46 | 62.2 | 47 | 59.3 | |||

| Health insurance | 1.65 | 1 | 0.20 | ||||

| Yes | 56 | 75.7 | 68 | 84.0 | |||

| No | 18 | 24.3 | 13 | 16.0 | |||

| Outpatient treatment prior to index admission | 0.03 | 1 | 0.86 | ||||

| Yes | 49 | 66.2 | 57 | 70.4 | |||

| No | 25 | 33.8 | 24 | 29.6 | |||

| Diagnosis | 11.8 | 1 | 0.001 | ||||

| Manic episode | 28 | 37.8 | 53 | 65.4 | |||

| Depressive episode | 46 | 62.2 | 28 | 34.6 | |||

| Insight | 20.6 | 1 | <0.001 | ||||

| Poor insight (ITAQ ≤17) | 18 | 24.3 | 49 | 60.5 | |||

| Good insight (ITAQ >17) | 56 | 75.7 | 32 | 39.5 | |||

| Previously hospitalized | 4.6 | 1 | 0.03 | ||||

| Yes | 48 | 64.9 | 65 | 80.2 | |||

| No | 26 | 35.1 | 16 | 19.8 | |||

| History of violence | 1.5 | 1 | 0.22 | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 9.5 | 13 | 16.0 | |||

| No | 67 | 90.5 | 68 | 84.0 | |||

| History of self-harm | 0.0 | 1 | 0.99 | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 13.5 | 11 | 13.6 | |||

| No | 64 | 86.5 | 70 | 86.5 | |||

| Aggrssive | 8.5 | 1 | 0.01 | ||||

| Low (MOAS ≤4) | 51 | 68.9 | 37 | 45.7 | |||

| High (MOAS ≥5) | 23 | 31.1 | 44 | 54.3 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | τ | df | p | |

| Age | 38.2 | 15.9 | 38.5 | 14.8 | −0.1 | 153 | 0.89 |

| Age of onset (years) | 33.8 | 15.2 | 30.7 | 13.8 | 1.3 | 150 | 0.20 |

| Length of illness (month) | 56.0 | 69.3 | 94.2 | 115.3 | −2.5 | 133 | 0.05 |

| MOAS | 4.1 | 5.8 | 7.2 | 6.9 | −3.0 | 153 | <0.001 |

| ITAQ | 19.3 | 3.5 | 14.7 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 153 | <0.001 |

Note:

MOAS, Modified Overt Aggression Scale; ITAQ, the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire.

Factors associated with involuntary admission in patients with bipolar disorders

As shown in Table 2, multiple binary logistic regression analysis revealed that variables significantly associated with involuntary admission were manic episode (OR = 3.65, 95% CI [1.65–8.09]), poor insight (OR = 7.52, 95% CI [3.17–17.85]), high aggressive (OR = 2.48, 95% CI [1.14–5.40]), and low level of education (OR = 3.13, 95% CI [1.37–7.17]).

Table 2. Independent contributors to involuntary admission patients with bipolar disorder (binary logistic regression model).

| Involuntary admission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Diagnosis (Manic episode) | 3.65 | [1.65–8.09] | 0.001 |

| Poor insight | 7.52 | [3.17–17.85] | <0.001 |

| Low level of education | 3.13 | [1.37–7.17] | 0.007 |

| High aggressive | 2.48 | [1.14–5.40] | 0.022 |

Note:

The study site has been controlled for as a covariate.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the involuntary admission of patients with bipolar disorders in China. Our study found that 52.3% of the Chinese inpatients with bipolar disorders were involuntary patients, and involuntary admission were significantly associated with manic episode, poor insight, more severe aggression and a low level of education.

The 52% rate of involuntary admissions in Chinese patients with bipolar disorder is higher than the 42% rate in all psychiatric inpatients from our previous survey (42.0%) in China (Zhou et al., 2015) and also higher than those of patients with bipolar disorders in many Western countries, such as Germany (18.9%) (Hoffmann et al., 2017). However, the risk factors for involuntary admissions are consistent with the findings found in previous studies in Western countries (Hustoft et al., 2013; Correll et al., 2017; Coid et al., 2018). In the present study, we found that low education level was associated with an increased risk of involuntary admission. Patients with a high level of education may have good comprehension and coping skills (Zhang, Harvey & Andrew, 2011), which can help patients completely understand their mental health status, communicate effectively with clinicians, and accept the need for hospitalization. Because of this, patients with a low level of education are more likely to be admitted involuntarily.

Our results suggest that manic episodes are more likely to lead to involuntary hospital admission than depressive episodes. This feature of involuntary hospitalization for bipolar disorders is consistent with our clinical experience. In general, patients in a manic episode are highly likely to be excitable and display psychotic symptoms, even psychomotor excitement and agitation, resulting in violent behaviors (Coid et al., 2018). Patients with these disturbed and disturbing behaviors are highly likely to be forced into the hospital. In general, patients in a depressive episode are at higher risk of suicide or self-harm behavior, which would result in involuntary hospitalization. However, we did not find the significant association between involuntary admission and a past history of suicidal behaviors; this finding is in line with a recent study (Stylianidis et al., 2017), showing that depression was a protective factor for involuntary admission. One possible explanation that would be depressed patients have relatively good insight compared to manic patients, and they are more likely to actively seek treatment (Raveesh et al., 2016).

As expected, we found more severe aggression was significantly associated with involuntary admission in patients with bipolar disorders. Because severe aggression is presented with acute agitation and dangerous behaviors, this association is plausible and keeping with findings from previous studies with samples of patients with schizophrenia (Correll et al., 2017; San et al., 2016).

Insight is a multidimensional concept that includes awareness of having psychopathological symptoms, the need for and acceptance of treatment, and awareness for the social consequence of that disorder (Gou et al., 2014). In general, a patient with good insight will voluntarily seek treatment and may have good compliance and benign drug-attitude (Ramachandran et al., 2016; Schuepbach et al., 2006). In the current study, poor insight was associated with a high risk of involuntary admission in patients with bipolar disorders, replicating the frequently reported association between poor insight and involuntary admission in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Montemagni et al., 2011).

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the definition of involuntary admission was based on patients’ self-report rather than on the legal status of each admission (voluntary/involuntary). For this reason, directly comparing our results with those of Western studies might be difficult. Second, some factors that may also affect the type of admission of patients with bipolar disorders, such as the season of the onset, social support, and stigma, were not investigated in this study. Finally, probably due to the relatively small sample of patients with bipolar disorders, our study failed to find an association between history of suicidal behaviors and involuntary admission. Studies with a large sample of patients with bipolar disorders are warranted to clarify the relationship between history of suicidal behaviors and involuntary admission.

Conclusions

Involuntary admission and hospital treatment have been widely accepted as indispensable measures to protect patients, others, and society; however, this situation still raises many problems (Zhang et al., 2015). Reducing the rate of involuntary admission and ensuring that patients with mental disorders receive appropriate treatments need further investigation. In this study, 52% of the Chinese patients with bipolar disorders were admitted involuntarily, and factors associated with involuntary admission in the context of bipolar disorders are somehow different from those found in patients with schizophrenia. This difference highlights the possible impact of the specific characteristics of each disorder on admission patterns. The results of our study may help develop programs for preventing and reducing involuntary hospitalizations for bipolar disorders and may help set up additional humane and friendly mental health services.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and their families for contributing to this research. We also thanks the following institute—the Hui Long Guan Hospital, Beijing; the Psychiatric Hospital of Jidong County, Heilongjiang; the Sixth Hospital of Peking University, Beijing; the Affiliated Hospital of Tongji University, Shanghai; the Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, Heilongjiang; the Third People’s Hospital of Huai’an, Anhui; the Shuangliu County Mental Health Institute, Sichuan; the Seventh Hospital of Liuyang County, Hunan; the West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Sichuan; the First Affiliated Hospital and the Department of Mental Health, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou; the Mental Health Center of Henan Province, Henan; and the Zigong Mental Health Center, Sichuan.

Funding Statement

This work was supported and funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0800701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81571341, 81371500), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (2019JJ40424). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jiansong Zhou, Email: zhoujs2003@csu.edu.cn.

Xiaoping Wang, Email: 503045@csu.edu.cn.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Chenyuli Luo performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper.

Hui Chen performed the experiments, prepared figures and/or tables.

Shaoling Zhong analyzed the data.

Huijuan Guo performed the experiments.

Qiguang Li performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, prepared figures and/or tables.

Weixiong Cai authored or reviewed drafts of the paper.

Giovanni de Girolamo authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Jiansong Zhou conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Xiaoping Wang conceived and designed the experiments, approved the final draft.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Board of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University in Hunan Province (2013068).

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in File S1.

References

- Coid et al. (2018).Coid JW, Kallis C, Doyle M, Shaw J, Ullrich S. Shifts in positive and negative psychotic symptoms and anger: effects on violence. Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(14):2428–2438. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll et al. (2017).Correll CU, Yu X, Xiang Y, Kane JM, Masand P. Biological treatment of acute agitation or aggression with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in the inpatient setting. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017;29:92–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craw & Compton (2006).Craw J, Compton MT. Characteristics associated with involuntary versus voluntary legal status at admission and discharge among psychiatric inpatients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41(12):981–988. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Girolamo et al. (2008).De Girolamo G, Rucci P, Gaddini A, Picardi A, Santone G. Compulsory admissions in Italy: results of a national survey. International Journal of Mental Health. 2008;37(4):46–60. doi: 10.2753/IMH0020-7411370404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo et al. (2011).Fiorillo A, De Rosa C, Del Vecchio V, Jurjanz L, Schnall K, Onchev G, Alexiev S, Raboch J, Kalisova L, Mastrogianni A, Georgiadou E, Solomon Z, Dembinskas A, Raskauskas V, Nawka P, Nawka A, Kiejna A, Hadrys T, Torres-Gonzales F, Mayoral F, Bjorkdahl A, Kjellin L, Priebe S, Maj M, Kallert T. How to improve clinical practice on involuntary hospital admissions of psychiatric patients: suggestions from the EUNOMIA study. European Psychiatry. 2011;26(4):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo et al. (2012).Fiorillo A, Giacco D, De Rosa C, Kallert T, Katsakou C, Onchev G, Raboch J, Mastrogianni A, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Catapano F, Dembinskas A, Nawka P, Kiejna A, Torres-Gonzales F, Kjellin L, Maj M, Priebe S. Patient characteristics and symptoms associated with perceived coercion during hospital treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;125(6):460–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgieva et al. (2017).Georgieva I, Bainbridge E, McGuinness D, Keys M, Brosnan L, Felzmann H, Maguire J, Murphy K, Higgins A, McDonald C, Hallahan B. Opinions of key stakeholders concerning involuntary admission of patients under the Mental Health Act 2001. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2017;34(4):223–232. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2016.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacco et al. (2012).Giacco D, Fiorillo A, Del Vecchio V, Kallert T, Onchev G, Raboch J, Mastrogianni A, Nawka A, Hadrys T, Kjellin L, Luciano M, De Rosa C, Maj M, Priebe S. Caregivers’ appraisals of patients’ involuntary hospital treatment: European multicentre study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;201(6):486–491. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou et al. (2014).Gou L, Zhou JS, Xiang YT, Zhu XM, Correll CU, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Lai KY, Wang XP. Frequency of involuntary admissions and its associations with demographic and clinical characteristics in China. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2014;28(4):272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He et al. (2017).He JF, Hong W, Shao Y, Han HQ, Xie B. Application of MOAS for evaluating of violence risk in the inpatients with mental disorders. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;33:28–31. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5619.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann et al. (2017).Hoffmann K, Haussleiter IS, Illes F, Jendreyschak J, Diehl A, Emons B, Armgart C, Schramm A, Juckel G. Preventing involuntary admissions: special needs for distinct patient groups. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12991-016-0125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustoft et al. (2013).Hustoft K, Larsen TK, Auestad B, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Ruud T. Predictors of involuntary hospitalizations to acute psychiatry. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2013;36(2):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Hoyer & Sexton (2007).Iversen KI, Hoyer G, Sexton HC. Coercion and patient satisfaction on psychiatric acute wards. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2007;30(6):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisova et al. (2014).Kalisova L, Raboch J, Nawka A, Sampogna G, Cihal L, Kallert TW, Onchev G, Karastergiou A, Del Vecchio V, Kiejna A, Adamowski T, Torres-Gonzales F, Cervilla JA, Priebe S, Giacco D, Kjellin L, Dembinskas A, Fiorillo A. Do patient and ward-related characteristics influence the use of coercive measures? Results from the EUNOMIA international study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49(10):1619–1629. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0872-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallert, Glockner & Schutzwohl (2008).Kallert TW, Glockner M, Schutzwohl M. Involuntary vs. voluntary hospital admission. A systematic literature review on outcome diversity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2008;258(4):195–209. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsakou et al. (2010).Katsakou C, Bowers L, Amos T, Morriss R, Rose D, Wykes T, Priebe S. Coercion and treatment satisfaction among involuntary patients. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(3):286–292. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly et al. (2018).Kelly BD, Umama-Agada E, Curley A, Duffy RM, Asghar M, Gilhooley J. Does involuntary admission with bipolar disorder differ from involuntary admission with schizophrenia and related disorders? A report from the Dublin involuntary admission study (DIAS) Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2018;24(3):209–216. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay, Nordt & Rössler (2011).Lay B, Nordt C, Rössler W. Variation in use of coercive measures in psychiatric hospitals. European Psychiatry. 2011;26(4):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (1995).Liu HQ, Zhang PY, Shang L, Yang PD, Wu HW. Insight of schizophrenia: the use of insight and treatment attitudes questionnaire. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 1995;7:158–161. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy et al. (1989).McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, Ortlip P, Brecosky J, Hammill K, Geller JL, Roth L. Insight in schizophrenia. Its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1989;177(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montemagni et al. (2011).Montemagni C, Bada A, Castagna F, Frieri T, Rocca G, Scalese M, Villari V, Rocca P. Predictors of compulsory admission in schizophrenia-spectrum patients: excitement, insight, emotion perception. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2011;35(1):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawka et al. (2013).Nawka A, Kalisova L, Raboch J, Giacco D, Cihal L, Onchev G, Karastergiou A, Solomon Z, Fiorillo A, Del Vecchio V, Dembinskas A, Kiejna A, Nawka P, Torres-Gonzales F, Priebe S, Kjellin L, Kallert TW. Gender differences in coerced patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):257. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan & Xie (2003).Pan Z, Xie B. A survey on psychiatric hospital admission and relative factors in China. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine. 2003;13:270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Raboch et al. (2010).Raboch J, Kalisová L, Nawka A, Kitzlerová E, Onchev G, Karastergiou A, Magliano L, Dembinskas A, Kiejna A, Torres-Gonzales F, Kjellin L, Priebe S, Kallert TW. Use of coercive measures during involuntary hospitalization: findings from ten European countries. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(10):1012–1017. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran et al. (2016).Ramachandran AS, Ramanathan R, Praharaj SK, Kanradi H, Sharma PS. A cross-sectional, comparative study of insight in schizophrenia and bipolar patients in remission. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2016;38(3):207–212. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.183085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveesh et al. (2016).Raveesh BN, Pathare S, Lepping P, Noorthoorn EO, Gowda GS, Bunders-Aelen JG. Perceived coercion in persons with mental disorder in India: A cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;58(6):S210–S220. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San et al. (2016).San L, Marksteiner J, Zwanzger P, Figuero MA, Romero FT, Kyropoulos G, Peixoto AB, Chirita R, Boldeanu A. State of acute agitation at psychiatric emergencies in Europe: the STAGE study. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2016;12(1):75–86. doi: 10.2174/1745017901612010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuepbach et al. (2006).Schuepbach D, Goetz I, Boeker H, Hell D. Voluntary vs. involuntary hospital admission in acute mania of bipolar disorder: results from the Swiss sample of the EMBLEM study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;90(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan & Burns (2011).Sheehan KA, Burns T. Perceived coercion and the therapeutic relationship: a neglected association? Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(5):471–476. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis et al. (2017).Stylianidis S, Peppou LE, Drakonakis N, Douzenis A, Panagou A, Tsikou K, Pantazi A, Rizavas Y, Saraceno B. Mental health care in Athens: are compulsory admissions in Greece a one-way road? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2017;52:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Post et al. (2009).Van Der Post L, Mulder CL, Bernardt CM, Schoevers RA, Beekman AT, Dekker J. Involuntary admission of emergency psychiatric patients: report from the Amsterdam Study of Acute Psychiatry. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(11):1543–1546. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang et al. (2015).Wang JP, Chiu CC, Yang TH, Liu TH, Wu CY, Chou P. The low proportion and associated factors of involuntary admission in the psychiatric emergency service in Taiwan. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0129204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie & Zheng (2001).Xie B, Zheng Z. The modification of Overt Aggression Scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2001;10:195–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yudofsky et al. (1986).Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D. The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143(5):35–39. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.5.670-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Harvey & Andrew (2011).Zhang J, Harvey C, Andrew C. Factors associated with length of stay and the risk of readmission in an acute psychiatric inpatient facility: a retrospective study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45(7):578–585. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.585452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang et al. (2015).Zhang S, Mellsop G, Brink J, Wang X. Involuntary admission and treatment of patients with mental disorder. Neuroscience Bulletin. 2015;31(1):99–112. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1493-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao & Dawson (2014).Zhao X, Dawson J. The new Chinese Mental Health Law. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2014;21(5):669–686. doi: 10.1080/13218719.2014.882248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong et al. (2017).Zhong BL, Chen SL, Tu X, Conwell Y. Loneliness and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2017;72(1):120–128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2015).Zhou JS, Xiang YT, Zhu XM, Liang W, Li H, Yi J, Liu F, Zhao N, Chen G, Shi S, Li G, Shen D, Wei N, Qi F, Tan W, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Hao W, Li L, Wang X. Voluntary and involuntary psychiatric admissions in China. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66(12):1341–1346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2016).Zhou JS, Zhong BL, Xiang YT, Chen Q, Cao XL, Correll CU, Ungvari GS, Chiu HF, Lai KYC, Wang XP. Prevalence of aggression in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia in China: A meta-analysis. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2016;8(1):60–69. doi: 10.1111/appy.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw measurements are available in File S1.